1. Introduction

A key concern for economic policymakers and macroeconomists is the sustainability of current account. The latter reflects the overall performance of an economy. The current account deficit (or surplus) reflects the net increase (or decrease) in an economy’s external liabilities, representing changes in the stock of external obligations. According to basic macroeconomic principles, a rise in the current account deficit typically results from either an increase in public deficits or a decline in private savings relative to investment (Cuestas and Monfort, 2021).

The liberalization of global financial markets has the potential to ease external financial constraints, which can contribute to current account imbalances. While such imbalances may suggest an efficient allocation of resources across countries seeking higher productivity, they can also become problematic if they lead to excessive external debt accumulation, thus undermining a country’s credibility and limiting access to international financing (Gnimassoun & Coulibaly, 2014). Consequently, large and persistent deficits may give rise to balance-of-payments crises, potentially triggering economic downturns (Christopoulos & León-Ledesma, 2010).

Milesi-Ferretti and Razin (1996), as well as Obstfeld and Rogoff (2005), emphasize that a current account becomes unsustainable when sharp reversals of large deficits lead to significant output losses and currency depreciation. Prolonged periods of unsustainable current account dynamics may end abruptly in exchange rate crises and economic collapses, or more gradually, in what is often termed a ‘soft landing,’ marked by investment and growth slowdowns (Cuestas and Monfort, 2021; Christopoulos & León-Ledesma, 2010).

Milesi-Ferretti and Razin (1996) distinguish between solvency and sustainability in economic terms. An economy is considered solvent if the present value of its future trade surpluses is sufficient to cover its current debt, thereby fulfilling its external intertemporal budget constraint. Sustainability, on the other hand, refers to the ability to meet this budget constraint without necessitating drastic changes in private sector behavior or significant policy adjustments. As highlighted by Milesi-Ferretti and Razin (1998), sustainability implies more structure due to its behavioral implications, whereas solvency is broader and more fundamental.

Some scholars argue that a current account deficit can be considered sustainable if the ratio of net external assets to GDP remains stable or decreases over time (Milesi-Ferretti and Razin, 1996; Gourinchas and Rey, 2007; Lane and Milesi-Ferretti, 2012). Another approach, known as the long-run current account model, suggests that a current account balance is sustainable if it adheres to the long-term solvency condition (Hakkio and Rush, 1991; Trehan and Walsh, 1991; Husted, 1992). Therefore, the study of current account sustainability focuses on whether an economy can maintain its long-term intertemporal budget constraints without necessitating significant policy interventions or private sector behavioral changes (Taylor, 2002; Lanzafame, 2014). In this context, a current account is considered sustainable when the present value of expected future trade surpluses matches the current level of debt.

In simpler terms, current account sustainability implies that the continuation of existing policies does not require abrupt policy shifts or measures such as a sudden tightening of monetary or fiscal policies that could provoke a significant recession. Nor does it lead to crises like a sharp rise in interest rates, rapid depletion of reserves, or exchange rate collapse. Historical evidence suggests that sudden corrections of large current account imbalances are often accompanied by severe disruptions, including sharp declines in output and widespread job losses (Engler et al., 2009).

This paper examines the sustainability of current account balances in three major economies: China, the United States, and Germany. These countries were chosen for three primary reasons. First, while China and Germany consistently maintain current account surpluses, the United States persistently experiences deficits. Second, these nations exhibit a dynamic interplay characterized by both intense economic competition and cooperation, as analyzed in

Section 2. Third, they hold substantial influence over global economic developments, playing pivotal roles in shaping international economic trends.

This research is motivated by the mixed empirical findings in the literature, which highlight the need for further investigation into current account sustainability. The paper makes a significant contribution by employing a variety of modern nonlinear unit root tests, alongside linear unit root tests and unit root tests with structural breaks, to evaluate current account sustainability. The use of these advanced econometric methods provides a more detailed and accurate assessment of the current account balances for the US, Germany, and China, particularly in the context of major global events like the COVID-19 pandemic and the US-China trade and currency war. The use of multiple unit root tests increases the robustness of our findings and allows for a more thorough examination of the underlying dynamics. Notably, this study is among the first to examine China’s current account sustainability using these state-of-the-art techniques.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews trade and current account trends in Germany, the United States, and China. In

Section 3, the main theoretical framework is presented, accompanied by a brief literature review of current account sustainability in the German, Chinese, and US economies.

Section 4 presents the models and methodologies used to investigate sustainability.

Section 5 discusses the results obtained from the econometric analyses. Finally,

Section 6 concludes by drawing key insights from the research.

2. Trade trends and Current Account Sustainability in Germany, USA and China

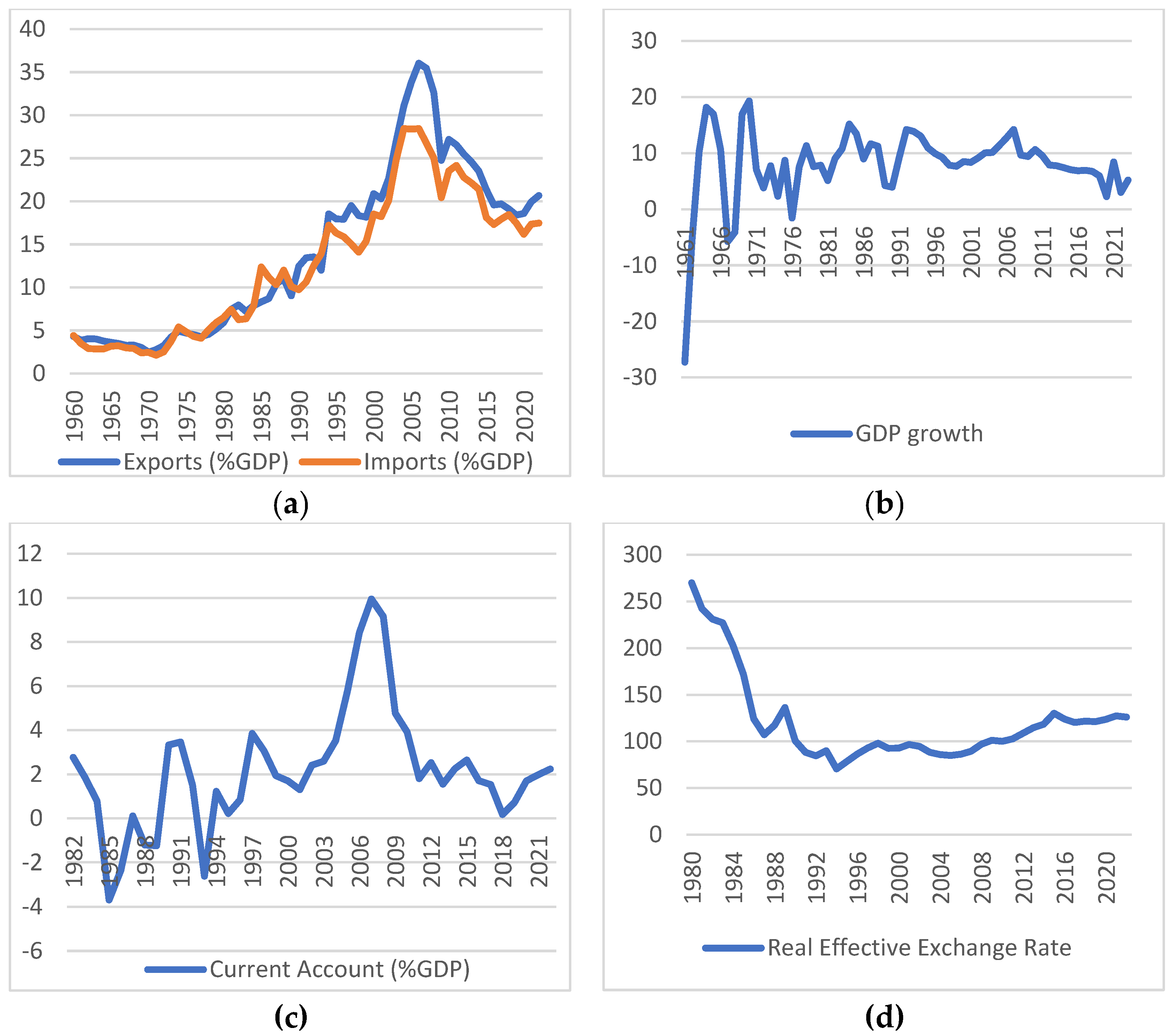

In recent decades, China has exhibited significant technological, economic, and trade growth, emerging as one of the world’s most powerful economies while consistently maintaining trade and current account surpluses as shown in

Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4.

As shown in Figure (c), China’s current account balance fluctuates significantly but maintains surpluses for most of the period, with the exceptions of 1985 and 1993. In 1994, a major policy change occurred when the People’s Bank of China devalued the domestic currency against the US dollar, transitioning the exchange rate regime to a managed float system. Furthermore, it is evident that China’s current account surplus increased sharply over time but declined after the global financial crisis of 2007-08, dropping from 10.08% of GDP in 2007 to 2.09% of GDP in 2014. Additionally, on August 24, 2015, China experienced a stock market crash of 8.48%, the largest decline since 2007.

A substantial portion of the US trade and current account deficit originates from China (Makin 2019; Poulakis and Tsaliki 2023a). Remarkably, over the past twenty years, China has increased its share of the US trade deficit from approximately one-fifth in 2002, to around one-third in 2008, and nearly half by 2018 (Poulakis and Tsaliki 2023a). Furthermore, China is often seen as the main contributor to the perceived imbalance in global capital flows and is held responsible for the persistent US trade deficit (Hoffmann 2013). Hence, the so-called "trade war" initiated by the U.S. in 2019 during President Trump’s administration intensified the already intense and long-standing economic and political rivalry between the two states. In addition, China has been accused of intervening in the exchange market through its international foreign exchange reserves, maintaining a devalued national currency to establish trade surpluses. However, as Weber and Shaikh (2022) argue, China’s exchange rate interventions neither directly determine nor independently explain China’s current account surpluses. Notably, the value of the Chinese national currency appears to follow the relative real unit labor cost of tradable goods in the long term (Poulakis and Tsaliki 2023a; 2023b). Nevertheless, the "trade war" has not been able to arrest China’s technological, economic and trade growth, or reverse the unfavorable trade conditions for the United States, as shown in

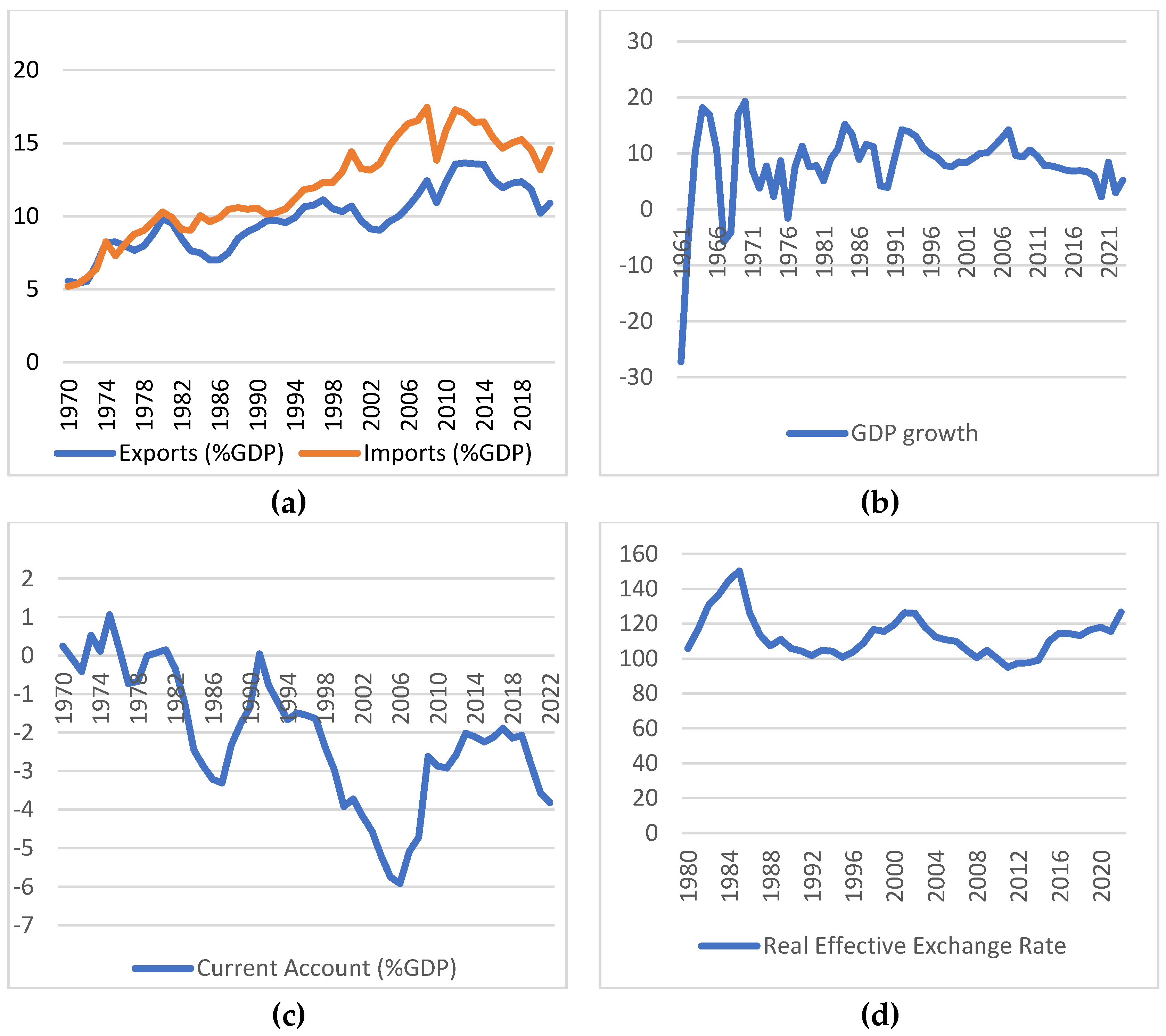

Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8.

The U.S. economy has faced persistent challenges with trade deficits and imbalances in the current account. A particularly significant trade deficit and current account imbalance occurred in 1987, primarily due to the continuous appreciation of the dollar. However, the appreciation of the dollar ceased after the Plaza Accord in 1985, which mandated its depreciation against the currencies of Japan, West Germany, and the United Kingdom. The objective was to strengthen the domestic and international trade positions of U.S. business. Subsequently, the Louvre Accord in 1987 prioritized the international stability of exchange rates and the stabilization of the U.S. dollar, which continued to decline in global foreign exchange markets, closely following the reduction in unit labor costs. The depreciation of the dollar persisted until the mid-’90s, accompanied by declines in both the trade balance and the current account balance. However, the fall in the dollar’s value against other major currencies led to capital outflows and restricted foreign investments in the U.S. This upheaval affected the robust financial sector, which advocated for a dollar appreciation. Consequently, the 1995 reverse Plaza Accord saw the central banks of Japan and Germany agreeing to depreciate their currencies to strengthen the value of the U.S. dollar. Despite this, it exacerbated the current account deficit as exports dwindled accordingly.

A few years later, amidst the recession resulting from the burst of the dot-com bubble and the events of September 11, the U.S. Federal Reserve lowered interest rates to stimulate the economy. This led to increased liquidity in the U.S. economy and a depreciation of the dollar. However, the depreciation failed to reverse the trade deficit and the current account deficit. Simultaneously, a real estate bubble emerged, and the external debt of the U.S. escalated. In this context, the IMF in 2004 asserted that achieving a smooth resolution of global imbalances, especially the large current account deficit of the U.S. and the surpluses in other economies, posed a significant risk to sustainable growth (Christopoulos and Leon-Ledesma 2010).

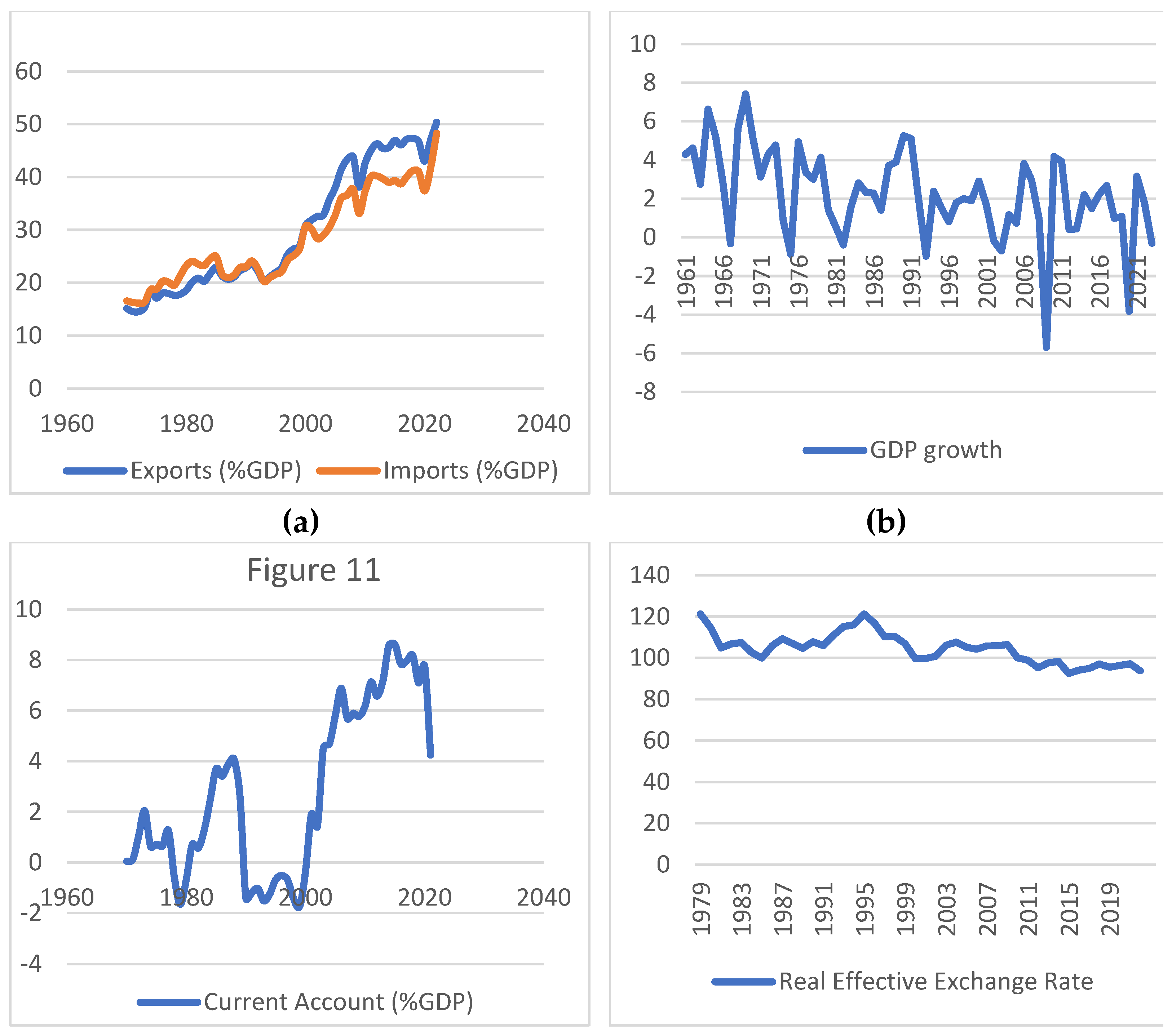

Additionally, the overseas markets of the United States and China are particularly significant for the German exports, especially after the Eurozone debt crisis and the reduction in the consumption capacity of Southern European countries. Specifically, in recent years, the United States has been the leading destination for German exports, with China following closely in second place. The United States has consistently experienced deficits in its bilateral trade with Germany. In addition, the structure of bilateral trade is of interest to the USA, as Germany exports ‘complex goods,’ such as those in the automotive industry, which directly compete with U.S. business (Poulakis et al. 2022). Similarly, regarding imports, China was the top supplier for Germany in 2021, while the United States ranked third in Germany’s imports. Finally, according to Destatis, since 2016, China has been Germany’s most significant "trade partner" in terms of bilateral relations (Poulakis et al. 2022).

Figure (c), which illustrates the evolution of the German Current Account, clearly shows a significant upward trend starting around 2000 based mainly on robust trade surplus, whereas prior to that, the Current Account remained relatively stable, fluctuating around zero. Thus, we can conclude that the adoption of the common European currency had a positive effect. However, attributing Germany’s economic success solely to the Eurozone’s common currency would be an oversimplification. Germany’s pre-existing high productivity levels and technological advantages played a pivotal role in enhancing competitiveness, especially at the expense of its European counterparts. The reduction in labor costs, supported by a flexible labor market due to deregulation, tax reductions, and stable real wages, has significantly boosted Germany’s profits and trade surpluses. Crucially, the implementation of ‘Agenda 2010’ in 2003 marked a turning point. This comprehensive set of economic reforms not only shaped the institutional framework for reducing unit labor costs but also included reductions in corporate taxes. Consequently, Germany witnessed a reduction in unit labor cost primarily through wage cuts rather than a significant increase in labor productivity, solidifying its position as an economic powerhouse within the European Union and the Eurozone (Gymnopoulos et al. 2017; Poulakis et al. 2022). However, it has been established that a decrease in relative unit real labor costs leads to a depreciation of the real exchange rate (Shaikh and Antonopoulos 2013; Boundi-Chraki and Perrotini-Hernandez 2021; Poulakis and Tsaliki 2023a; 2023b). As a result, the international competitiveness of the German economy improved due to a combination of a “hard” euro and a simultaneous reduction in labor costs.

The impact of these reforms extended beyond domestic boundaries. Surpluses generated found their way into German banks, which, in turn, leveraged these financial resources by providing loans to EU countries facing deficits. This dynamic interaction within the Eurozone was not only a testament to Germany’s economic strength but also underscored the interconnectedness of Eurozone economies.

Germany’s global advantage was further amplified by the Euro’s competition with the dollar, which elevated German banks to a leading position on the international stage. The continuous decrease in unit labor costs, coupled with reduced tax rates, fortified the international competitiveness of German businesses, leading to increased profitability. Overall, Germany’s modern economic trajectory has been shaped by a combination of the adoption of the euro, strategic economic reforms, and global competitiveness.

3. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review of Current Account Balance

As mentioned, sustainability in the current account is defined as the ability of an economy to satisfy its long-term intertemporal budget constraint. Following Hakkio and Rush (1991), Trehan and Walsh (1991) and Husted (1992), we begin by considering the government’s tow-period budget constraint in real terms: In a stochastic model with zero growth, we define the tow-period budget constraint as:

where

,

,

,

,

, and

represent consumption, investment, government expenditures, international borrowing, output and the world interest rate, respectively. Furthermore

is the initial debt, corresponding to the country’s external debt. If we rearrange (1) we get:

or

where

is the current account,

is the trade balance,

are exports, and

are imports. If we denote with

the information set at the beginning of the period

and assume that

is stochastic, with

for all

, then by iterating (2) forward we get:

From equation (3), if the future value of net export surpluses matches the current stock of external debt, international lenders will be inclined to extend credit to the country in question. The final term in equation (3) must be equal to zero, under the hypothesis of present value budget balance:

If condition (4) holds true, the present value of the depreciated future debt stock diminishes to zero as the time horizon extends to infinity. Trehan and Walsh (1991) demonstrate that for condition (4) to hold, must be stationary. However, this condition is sufficient only when the GDP growth equals zero. If the growth is different from zero, as is the case in reality, then for relation (4) to be valid and the current account to be sustainable, the ratio must be stationary.

In empirical analysis, the use of unit root tests for the order of integration of the current account has become increasingly prevalent. This is due to the fact that if shocks have permanent effects, akin to unit root processes, the variable will not revert to equilibrium after a shock, necessitating policy interventions to counteract the initial shock’s effects. Conversely, if the variable is stationary, shocks have only transitory effects, and the variable will eventually revert to equilibrium (Cuestas and Monfort 2021).[i] (According to Taylor (2002), the speed of mean reversion of the dynamics of the current account can be viewed as a concise measure reflecting the extent of capital mobility.) In this vein, non-stationarity implies a violation of the inter-temporal budget constraint (Trehan and Walsh 1991; Husted 1992).

Therefore, in assessing the sustainability of the current account balance, numerous researchers have utilized conventional linear unit root and cointegration tests on time series data (Trehan and Walsh 1991; Wu et al. 1996; Liu and Tanner 1996; Apergis et al. 2000; Bergin and Sheffrin 2000; Arize 2002; Baharumshah et al. 2003; Ismail and Baharumshah 2008). [ii] (Husted (1992) establishes that mean reversion in the current account can be understood by investigating the cointegration properties between exports and imports. He posits that the sustainability of the current account is confirmed when exports and imports exhibit cointegration with a cointegrating vector of (1, -1).) Motivated by the statistical power of advancements in panel unit root and panel cointegration, a growing number of researchers have also employed these innovative methods to test the long-term sustainability of current account imbalances (Wu et al. 2001; Lau et al. 2006; Holmes 2006; Holmes and Panagiotidis 2009).

However, subsequent research has delved into the nonlinearity of current account adjustments, pointing to three primary sources: the twin deficit channel, the level of a country’s debt, reflecting the willingness of foreign creditors to hold domestic assets, and transaction costs (Chortareas et al. 2004). Another source of non-linearity is mentioned by Taylor (2002), who argues that the speed of convergence towards equilibrium can reflect the degree of capital mobility, which is subject to policy and institutional changes. Specifically, if the expectations of international agents regarding the risk of a country’s assets change due to persistent deficits in the current account, the speed of mean reversion and the mean itself of the current account will also be altered. Clarida et al. (2007) highlight that both government interventions and market forces can trigger more rapid adjustments in the current account when deficits enter a particular "danger zone," resulting in non-linear dynamics in how the current account corrects itself. Hence, the dynamics of adjustment may be non-linear. Therefore, a considerable portion of the literature adopts the application of non-linear tests (Chortareas et al. 2004, Christopoulos and León-Ledesma 2010; Kim et al. 2009; Cuestas 2013).

Turning to the sustainability of the Chinese current account the sustainability of the Chinese current account, the existing literature is limited. Sahoo et al. (2016) assert that China maintains a sustainable current account balance, whereas Tiwari (2011) arrives at the opposite conclusion. Additionally, Narayan and Sriananthakumar (2020) find that China’s current account satisfied the strong form of sustainability across all sub-samples during the period from 1970 to 2014 but became unsustainable from 2015 to 2018.

In terms of the U.S. current account balance, the literature presents mixed findings, as illustrated in

Table 1. This lack of consensus underscores the need for further investigation into the matter, which this paper aims to address.

Regarding the German economy, the empirical literature similarly fails to reach a unanimous conclusion; however, the majority of studies indicate that the current account is not sustainable, as shown in

Table 2. Consequently, this paper, like its exploration of the U.S. current account, seeks to illuminate this nuanced topic and contribute to the ongoing discussion surrounding current account sustainability.

4. Model and Methodology

To evaluate the sustainability of current accounts in Germany, China, and the United States, we utilize a combination of linear and nonlinear unit root tests, focusing on the current account as a percentage of GDP. Our dataset includes annual observations from 1970 to 2021 for Germany and the United States, while the data for China spans from 1982 to 2021. The current account data were sourced from the World Bank database.

We assess the stationarity of the current account variable by employing three linear unit root tests, four tests with structural breaks, and four nonlinear unit root tests. By incorporating a wide range of econometric approaches, this study aims to deliver a more detailed evaluation of the current account balances for the US, Germany, and China, especially in the context of significant global economic events such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the trade and currency tensions between the US and China. The extensive time frame of our analysis captures various phases of the economic cycle, which enhances the robustness of our results and minimizes biases related to specific economic conditions, such as periods of growth or crises. Moreover, the use of multiple unit root tests increases the robustness of our findings and allows for a more thorough examination of the underlying dynamics.

Following this, present a concise overview of the nonlinear tests created by Kapetanios et al. (2003), Solis (2009), Kruse (2011), and Kilic (2011), all of which are incorporated into our analysis it is presented. These tests are specifically designed to identify potential nonlinear characteristics within the current account data, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of the sustainability of current account balances in the economies under review.

4.2.1. Kapetanios, Shin and Smith Non-Linear Unit Root Test

The KSS unit root test is used against an alternative hypothesis, which proposes a globally stationary process defined as an Exponential Smooth Transition Autoregressive (ESTAR) model. The following ESTAR model is applied:

where

is the time series and can be demeaned or detrended,

is the total number of observations,

is the error term following an independent and identical distribution with 0 mean and variance

,

are unknown parameters and

is an exponential transition function to present the non-linear adjustment, such as:

where

is the slope parameter and

is a symmetric U-shaped function around zero, ranged from 0 and 1 determines the small and large deviations from the equilibrium in absolute terms. Substituting relation (6) into relation (5) gives the following ESTAR model:

If

, then it effectively determines the speed of mean reversion. The null hypothesis,

, supports that

exhibits a linear unit root behavior while under the alternative hypothesis,

,

follows a globally stationary ESTAR process. However, the null hypothesis cannot be tested since

isnot identified under the null. Thus, Kapetanios et al. (2003) use a first-order Taylor series approximation to the ESTAR model (7) around

andthe following auxiliary regression is derived:

where

is the error term. If the errors in the auxiliary regression (8) are correlated, the regression can be augmented by including k lags of

to correct for serially correlated errors:

Thus, the new null hypothesis is against the alternative . As Kapetanios et al. (2003) showed, the asymptotic distribution of the -statistic for null hypothesis, denoted by , is non-standard. Hence, they use stochastic simulations to tabulate asymptotic critical values of the -statistic.

4.2.3. Kruse Non-Linear Unit Root Tests

Kruse (2011) proposes a unit root test, which extends the test of Kapetanios et al (2003) by relaxing the assumption of zero location parameter. Thus, Kruse’s test allows for the possibility that

may revert to an equilibrium value different from zero. The degree of mean reversion depends on the distance between

and an unknown nonzero location parameter

. Kruse (2010) considers the following ESTAR specification:

where

is the error term and is

.

[iii] (If c approaches to zero then (10) becomes a linear AR(1) model) The null hypothesis is

against the alternative

. In order to avoid the presence of nuisance parameters under the null hypothesis, Kruse (2010), following Kapetanios et al (2003), uses a Taylor approximation around

Thus, the following auxiliary regression is derived:

where

is an error term. Furthermore, (11) can be augmented with

lags of

to allow for the serial correlation:

The null hypothesis of nonstationarity involves testing against a globally stationary ESTAR process,. Kruse (2011) proposes a τ test to test the null hypothesis which is a version of the Abadir and Distaso (2007) Wald test and has a non-standard asymptotic distribution; the corresponding asymptotic critical values are provided by Kruse (2011).

4.2.4. Kilic Nonlinear Unit Root Test

Kılıç (2011) considers the following representation of the ESTAR model:

where

is a stationary process,

and

are unknown parameters,

is an exponential transition function,

is the transition variable and

is the transition parameter, which determines the speed of transition between two extreme regimes; high values of

imply faster transition and low values of

imply slower transition.

Like Kapetanios et al (2003), Kruse considers the model with serial correlation, operating under the presumption that serially correlated errors are introduced in a linear way. Thus, model (13) is modified as follows:

The null hypothesis is set as

, while the alternative hypothesis is

. As in the previous cases, slope parameter

is unidentified and this leads to a nuisance parameter problem under the null hypothesis. In order to overcome this problem, Kruse (2011) uses the lowest possible t-value over a fixed parameter space of

values that are normalized by the sample standard deviation of the transition variable

. The corresponding statistic is the following:

where

is the sample standard deviation of the transition variable

while

and

are OLS estimators derived by model (14). In implementing the test, Kilic suggests using a grid over

, with the grid size given by

. The

statistic has a non-standard asymptotic distribution, and the asymptotic critical values are tabulated through stochastic simulations by Kilic (2011).

4.2.4. Sollis Nonlinear Unit Root Test

Sollis (2009) unit root test utilizes an asymmetric exponential smooth transition autoregressive (AESTAR) model to capture the nonlinear asymmetric adjustment process. To capture the asymmetry, the model is extended with the help of an additional transition function:

where

∼

and

is a transition variable. Furthermore,

is a logistic transition function for two regimes and it is determined by the positive and negative deviations from the equilibrium of

, while

is an symmetric exponential U-shaped transition function, as in the KSS test.

Model (15) implies a globally stationary process that requires , and . If , then the adjustment to the equilibrium is symmetrical; however, if , the adjustment is asymmetrical, capturing both sign and size asymmetry in the process of returning to equilibrium.

The null hypothesis,

, supports a linear unit root process against the alternative,

hypothesis of a globally AESTAR stationary process. But, as in the previous cases, the problem of undefined parameters under the null hypothesis, arises. Thus, Sollis (2009) applies a tow step, around

and

, first-order Taylor series approximation to the AESTAR model:

The term is added in order to deal with the serial correlation. The joint hypothesis of linearity and unit root of this auxiliary model is H0: Sollis (2009) provides the asymptotic distribution of an F-test for testing the null hypothesis as well as the critical values for zero mean, non-zero mean and deterministic trend cases.

5. Empirical Results

Initially, we apply three linear unit root tests: the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test by Said and Dickey (1984), the Phillips-Perron test (PP-1988), and the DF-GLS test by Elliot et al., (1992). The results of these tests are presented in

Table 3.

From the results presented in

Table 3, we conclude that the current account balance as a percentage of GDP is non-stationary in any of the three countries.

Acknowledging the widely recognized potential bias caused by structural breaks in time series, which can result in an incorrect acceptance of the null hypothesis of a unit root when it is actually false, we employ a battery of unit root tests with breakpoints.

Firstly, four distinct specifications of the Dickey-Fuller regression are examined, following the methodologies outlined by Perron and Vogelsang (1992a; 1992b), Vogelsang and Perron (1998), and Zivot and Andrews (1992). Each specification corresponds to different assumptions regarding trend and break dynamics. Specifically, when the regression includes only a constant and the break occurs in the constant, it refers to the tests by Perron and Vogelsang (PV- 1992a;1992b). When the regression includes both a constant and a trend, but the break occurs in either the constant or the trend, it refers to the tests by Vogelsang and Perron (VP-1998). Lastly, when the regression includes both a constant and a trend, and the break occurs in both the constant and the trend, it refers to the tests by Zivot and Andrews (ZA-1992). The results of these tests are presented in

Table 4.

From the results of the tests that include a one structural break in the model, we conclude that none of the examined economies exhibit a sustainable current account balance.

Furthermore, we employ the Lee and Strazicich (2003) unit root test. This test also mitigates the shortcomings of conventional unit root tests by incorporating one or two endogenous breaks and using the Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test statistic. The findings from this test are detailed in

Table 5.

In this case, the results also indicate that the current account balance is not sustainable for all three economies under examination. Only the current account balance as a percentage of GDP for the USA appears to be stationary when the break is present only in the trend. However, following the relevant literature, which suggests that the return to equilibrium may be nonlinear, we subsequently apply three nonlinear unit root tests based on the ESTAR model, the results of which are presented in

Table 6.

From

Table 6, which presents the results of the KSS (2004), Kruse (2011), and Kilic (2011) tests that employ an ESTAR model, we conclude that the current account balance as a percentage of GDP is not stationary. This final result argues against the sustainability of the current account balance.

Finally,

Table 7 presents the results of Solis’s (2009) nonlinear unit root test using an AESTAR model.

Lastly, based on the results in

Table 7, we can confidently assert that the deficit in the current account balance of the United States is not sustainable. The same holds true for the surplus exhibited by the German economy. We reach the same conclusion for China, albeit with less certainty, as the AESTAR model indicates that when only a constant is included in the regression, the current account balance as a percentage of GDP is stationary.

4. Conclusions

As we have emphasized, there are numerous critical reasons for economic policymakers and macroeconomists to be concerned about the sustainability of the current account, as it is a crucial indicator of an economy’s overall health. In this paper, we examine whether the dynamics of the U.S., German, and Chinese current accounts align with their intertemporal budget constraints. We consider the stationarity of the current account to be a sufficient condition for this definition of sustainability. However, we argue that the common assumption of a linear process for the current account under the alternative hypothesis of stationarity may not accurately reflect reality. This is due to three primary sources of nonlinearity: the twin deficit channel, the level of a country’s debt reflecting the willingness of foreign creditors to hold domestic assets, and transaction costs (Chortareas et al., 2004). Another source of nonlinearity is highlighted by Taylor (2002), who posits that the speed of convergence towards equilibrium can indicate the degree of capital mobility, which is influenced by policy and institutional changes. Specifically, if international agents’ perceptions of the risk associated with a country’s assets change due to persistent current account deficits, both the speed of mean reversion and the mean itself of the current account will be affected.

Therefore, we employ both linear and nonlinear unit root tests to assess the sustainability of the current accounts for the US, Germany, and China. Our findings indicate that each economy’s current account is unsustainable. Our results for Germany are consistent with similar studies examining the sustainability of the current account (Liu and Tanner 1996; Dulger and Ozdemir 2005; Holmes 2006; Herwartz and Xu 2008; Cunado et al. 2010; Sivrikaya and Kurul 2020). Similarly, our results for the U.S. economy align with previous research that conclude that the U.S. current account is unsustainable (Liu and Tanner 1996; Wu et al. 1996; Fountas and Wu 1999; Dulger and Ozdemir 2005; Chen 2011; Hatzinikolaou and Simos 2013; Narayan and Sriananthakumar 2020) despite mixed findings in the literature that support the opposite (Wickens and Uctum 1992; Irandoust and Ericsson 2004; Matsubayashi 2005; Holmes 2006; Holmes and Panagiotidis 2009; Takeuchi 2010; Christopoulos and León-Ledesma 2010). In addition, for the case of China, where the literature is very limited (Tiwari 2011; Sahoo et al. 2016; Narayan and Sriananthakumar 2020), we conclude that the Chinese current account balance is also unsustainable.

Thus, substantial changes are required in all three economies to achieve sustainable current account balances. These adjustments can result from either government intervention or shifts in the actions of private and non-state economic actors. However, given the persistent and entrenched nature of the current account imbalances in all three economies, altering the behavior of the latter appears particularly challenging, rendering state intervention the more viable solution.

References

- Abadir, Karim M., and Distaso, Walter. Testing joint hypotheses when one of the alternatives is one-sided. Journal of Econometrics 2007, 140, 695–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apergis, Nicholas, Katrakilidis, Konstantinos, and Tabakis, Nicholas. Current account deficit sustainability: The case of Greece. Applied Economics Letters 2000, 7, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arize, Augustine C. Imports and exports in 50 countries: Tests of cointegration and structural breaks. International Review of Economics and Finance 2002, 11, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharumshah, Ahmad Zubaidi, Evan Lau, and Fountas, Stilianos. On the sustainability of current account deficits: Evidence from four ASEAN countries. Journal of Asian Economics 2003, 14, 465–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergin, Paul R., and Sheffrin, Steven M. Interest rates, exchange rates and present value models of the current account. The Economic Journal 2000, 110, 535–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boundi-Chraki, Fahd, and Perrotini-Hernández, Ignacio. Absolute cost advantage and sectoral competitiveness: Empirical evidence from NAFTA and the European Union. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 2021, 59, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Shyh-Wei. Are current account deficits really sustainable in the G-7 countries? Japan and the World Economy 2011, 23, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chortareas, Georgios, E., Kapetanios, George, and Uctum, Merih. An investigation of current account solvency in Latin American using nonlinear non-stationarity tests. Studies in Nonlinear Dynamics and Econometrics 2004, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, Dimitris, and León-Ledesma, Miguel. A. Current account sustainability in the US: What did we really know about it? Journal of International Money and Finance 2010, 29, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarida, Richard H., Manuela Goretti, and Mark P. Taylor. Are there Thresholds of Current Account Adjustment in the G7. In G7 Current Account Imbalances: Sustainability and Adjustment; Clarida, R.H., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuestas, Juan Carlos, and Monfort, Mercedes. Current account sustainability in Central and Eastern Europe: Structural change and crisis. Empirica 2021, 48, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuestas, Juan Carlos. The current account sustainability of European transition economies. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 2013, 51, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunado, Juncal, Gil-Alana, Luis A., and Gracia, Fernando Pérez. European current account sustainability: New evidence based on unit roots and fractional integration. Eastern Economic Journal 2010, 36, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulger, Fikret, and Ozdemir, Zeynel Abidin. Current account sustainability in seven developed countries. Journal of Economic & Social Research 2005, 7, 47–80. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, Graham, Rothenberg, Thomas J., and Stock, James H. Efficient tests for an autoregressive unit root. Econometrica 1996, 64, 813–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, Phillip., Fidora, Michael, and Thimann, Christian. External imbalances and the US current account: How supply-side changes affect an exchange rate adjustment. Review of International Economics 2009, 17, 927–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountas, Stilianos, and Jyh-Lin, Wu. Are the U.S. current account deficits really sustainable? International Economic Journal 1999, 13, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnimassoun, Blaise, and Issiaka Coulibaly. Current account sustainability in Sub-Saharan Africa: Does the exchange rate regime matter? Economic Modelling 2014, 40, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourinchas, Pierre-Olivier, and Helene Rey. From world banker to world venture capitalist: US external adjustment and the exorbitant privilege. In G7 Current Account Imbalances: Sustainability and Adjustment; Clarida, R.H., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007; pp. 11–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gymnopoulos, Alexandros, Poulakis, Athanasios, Poulakis, Charalampos, and Chatzarakis, Nikolaos. Structural change in productivity of German economy from unification till Euro-crisis: An input-output analysis. proceedings of the 7th International Conference of ASECU Youth, Thessaloniki, Greece, 20–27 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hakkio, Craig. S., and Rush, Mark. Is the budget deficit “too large”? Economic Inquiry 1991, 29, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzinikolaou, Dimitris, and Simos, Theodore. A new test for deficit sustainability and its application to US data. Empirical Economic 2013, 45, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herwartz, Helmut, and Xu, Fang. Reviewing the sustainability/stationarity of current account imbalances with tests for bounded integration. The Manchester School 2008, 76, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, Mathias. What drives China’s current account? Journal of International Money and Finance 2013, 32, 856–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, Mark J. How sustainable are OECD current account balances in the long-run? Manchester School 2006, 74, 626–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, Mark J., and Panagiotidis, Theodore. Cointegration and asymmetric adjustment: Some new evidence concerning the behavior of the US current account. The BE Journal of Macroeconomics 2009, 9, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, Steven. The emerging US current account deficit in the 1980s: A cointegration analysis. The Review of Economics and Statistics 1992, 74, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irandoust, Manuchehr, and Ericsson, Johan. Are imports and exports cointegrated? An international comparison. Metroeconomica 55 2004, 55, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Hamizun Bin, and Baharumshah, Ahmad Zubaidi. Malaysia’s current account deficits: An intertemporal optimization perspective. Empirical Economics 2008, 35, 569–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanios, George, Shin, Yongcheol, and Snell, Andy. Testing for a unit root in the nonlinear STAR framework. Journal of Econometrics 2003, 112, 359–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, Rehim. Testing for a unit root in a stationary ESTAR process. Econometric Reviews 2011, 30, 274–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Bong-Han, Min, Hong-Ghi, and McDonald, Judith A. Are Asian countries current accounts sustainable? Deficits, even when associated with high investment, are not costless. Journal of Policy Modeling 2009, 31, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, Robinson. A new unit root test against ESTAR based on a class of modified statistics. Statistical Papers,52 2011, 52, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, Philip R., and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti. External adjustment and the global crisis. Journal of International Economics 2012, 88, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Evan, Baharumshah, Ahmad Zubaidi, and Haw, Chan Tze. Current account: Mean-reverting or random walk behavior? Japan and the World Economy 2006, 18, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzafame, Matteo. Current account sustainability in advanced economies. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 2014, 23, 1000–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Junsoo, and Strazicich, Mark C. Minimum Lagrange multiplier unit root test with two structural breaks. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85: 1082-1089. 2003, 85, 1082–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Peter, and Tanner, Evan. International intertemporal solvency in industrialized countries: Evidence and implications. Southern Economic Journal 1996, 62, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makin, Antony J. Lessons for macroeconomic policy from the Global Financial Crisis. Economic Analysis and Policy 2019, 64, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubayashi, Yoichi. Are US current account deficits unsustainable? Testing for the private and government intertemporal budget constraints. Japan and the World Economy 2005, 17, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milesi-Ferretti, Gian Maria, and Razin, Assaf. Persistent Current Account Deficits: A Warning Signal? International Journal of Finance and Economics 1996, 1, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milesi-Ferretti, Gian Maria, and Razin, Assaf. Sharp reductions in current account deficits: An empirical analysis. European Economic Review, 42 1998, 42, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, Seema, and Sriananthakumar, Sivagowry. Are the current account imbalances on a sustainable path? Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13 2020, 13, 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obstfeld, Maurice, and Rogoff, Keneth S. Global current account imbalances and exchange rate adjustments. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2005, 2005, 67–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perron, Pierre, and Vogelsang, Timothy J. Testing for a unit root in a time series with a changing mean: corrections and extensions. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 1992, 10, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perron, Pierre, and Vogelsang, Timothy J. Nonstationarity and level shifts with an application to purchasing power parity. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 1992, 10, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Peter C. B., and Perron, Pierre. Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika 1988, 75, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulakis, Thanos, and Tsaliki, Persefoni. Exchange rate determinants of the US dollar and Chinese RMB: A classical political economics approach. Investigación Económica 2023, 82, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulakis, Thanos, and Tsaliki, Persefoni. Dynamic linkages between real exchange rates and real unit labour costs: evidence from 18 economies. International Review of Applied Economics 2023, 37, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulakis, Thanos, Poulakis, Haris, and Chatzarakis, Nikolaos. Input output structural decomposition analysis of German economy during Euro era: A critical appraisal. Social Science Tribune 2021, 19, 81–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, M.; Manoranjan, Babu, Suresh, and Dash, Umakant. Long run sustainability of current account balance of China and India: New evidence from combined cointegration test. Intellectual Economics 2016, 10, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, Said E., and Dickey, David A. Testing for unit roots in autoregressive-moving average models of unknown order. Biometrika 1984, 71, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, Anwar, and Antonopoulos, Rania. Explaining long-run exchange rate behavior in the United States and Japan. In Alternative theories of competition: Challenges to the orthodoxy; Moudud, J.K., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Sivrikaya, Ayşen, and Kurul, Zühal. Sustainability of current account surpluses: Evidence from European countries. Prague Economic Papers 2020, 29.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollis, Robert. A simple unit root test against asymmetric STAR nonlinearity with an application to real exchange rates in Nordic countries. Economic modelling 2009, 26, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, Fumihide. US external debt sustainability revisited: Bayesian analysis of extended Markov switching unit root test. Japan and the World Economy 2010, 22, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Alan M. A century of current account dynamics. Journal of International Money and Finance 2002, 21, 725–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, Aviral K. Are Exports and imports cointegrated in India and China? An empirical analysis. Economics Bulletin 2011, 31, 860–873. [Google Scholar]

- Trehan, Bharat, and Walsh, Carl E. Testing intertemporal budget constraints: Theory and applications to US federal budget and current account deficits. Journal of Money, Credit and banking 1991, 23, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Isabella, and Shaikh, Anwar. The US–China trade imbalance and the theory of free trade: debunking the currency manipulation argument. Capitalism: An Unsustainable Future? 2022, 102–125. [Google Scholar]

- Wickens, Michael R., and Uctum, Merih. The sustainability of current account deficits: a test of the US intertemporal budget constraint. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 1993, 17, 17–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Jyh-Lin, Chen, Show-Lin and Lee, Hsiu-Yun. Are current account deficits sustainable?: Evidence from panel cointegration. Economics Letters 2001, 72, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Jyh-Lin, Stilianos Fountas, and Show-Lin Chen. Testing for the sustainability of the current account deficit in two industrial countries. Economics Letters 1996, 52, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivot, Eric, and Andrews, Donald W. K. Further evidence on the great crash, the oil-price shock, and the unit-root hypothesis. Journal of business & economic statistics 2002, 20, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).