1. Introduction

Soccer requires players to execute short linear sprints interspersed with periods of passive rest or low to moderate activity. These sprints are often followed by active or passive rest periods longer than one minute, allowing complete or near-complete recovery [

1]. While some studies report a decline in performance during repeated sprints, they suggest that this decrease is relatively small and that players are able to recover well between sprints [

2], others indicate that linear sprints performed with short rest intervals (i.e., less than 30 s) may negatively impact sprint performance [

3]. This potential decline in linear sprint performance can be attributed to repeated sprint ability (RSA).

RSA refers to an athlet

e’s capacity to perform short sprints (less than 6 s) with brief rest periods (less than 30 s), and it may influence the high-intensity efforts required during critical moments in competitions, such as counter-attacks and defensive recovery [

4]. Several factors may influence RSA, including the muscle power output [

5]. A previous study reported a moderate correlation (

r = 0.51 to 0.54,

p = 0.01 to 0.02) between leg strength and the maximum RSA in soccer players [

6]. Furthermore, a recent systematic review indicated that increasing strength levels could enhance soccer player

s’ RSA, including the best, mean, and total times [

7]. Previous studies have suggested that improving strength levels can positively impact soccer player

s’ RSA. Consequently, various warm-up protocols designed to enhance soccer player

s’ performance have garnered significant attention from strength and conditioning coaches [

8]. One such warm-up protocol is post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE), which aims to develop strength by utilizing different intensities of one repetition maximum (1RM) with external loads.

PAPE is defined as an acute increase in human voluntary movement performance, including maximal force, power, and speed following preloading [

9,

10]. While some researchers have presented their views on the mechanisms underlying the post-activation potentiation (PAP) effect in the literature, it is theoretically anticipated that PAP should result in PAPE. The mechanisms that support PAPE have not been fully elucidated, suggesting that further studies are necessary [

11]. Additionally, researchers argued that the need for further exploration of PAPE arises partly from the lack of observed effects when PAP is significant (e.g., within 3-4 minutes post-contraction) [

9]. , Notably, the temporal profile of myosin light chain phosphorylation, a key mechanism underlying

“classical

” PAP, rarely aligns with the temporal profile of voluntary force enhancement. Furthermore, unlike PAP, changes in muscle temperature, muscle/cellular water content, and muscle activation may contribute at least partially to voluntary force enhancement. Consequently, this enhancement has been recently termed PAPE[

11]. Several preloading methods have been applied to achieve PAPE. Although heavy resistance exercises are commonly performed as preloading, studies have also been conducted on plyometric jumps, weight vests, isometric contractions, and electromyostimulation (EMS) applications [

12,

13]. Some studies have indicated that maximal or near-maximal preloading is one of the most effective ways to elicit PAPE [

13]. In a previous study examining the effects of preload on repeated sprint performance, significant improvements were observed in the repeated sprint performance of elite athletes after performing squats at 90% of their 1RM. However, no similar development was observed in amateur athletes, and PAPE may occur at a minimal level [

13]. However, some studies examined the effect of PAPE on one-time sprints. A study demonstrated that combined conditioning activity and strength protocols could be incorporated into warm-up routines instead of traditional warm-ups to enhance immediate sprint performance in amateur soccer players [

14]. Contrary to this study, another study did not report the effect of PAPE on short-distance linear sprint performance after preload [

12]. Although there is a widespread belief that high preloads reveal PAPE, there is currently no consensus on specific methods for preloads, including the intensity and volume of these methods, the recommended rest period following these methods, and the duration of the effectiveness of PAPE. Researchers have agreed on an experimental design that elicits PAPE after squat jumps and ballistic bench shots [

15,

16]. However, more studies are needed to understand whether high preloads elicit PAPE in more functional movements such as RSA [

13]. These movements require speed, power, and endurance, making them essential for soccer success.

This study highlights the potential of strength-focused warm-up protocols, particularly PAPE, to significantly improve soccer player

s’ RSA. By emphasizing the link between strength development and enhanced RSA, these findings could present alternative training approaches for soccer athletes, leading to improved on-field performance and more effective conditioning strategies. Although the precise mechanisms of PAPE in the context of intense warm-ups remain unclear, the potential for enhancing RSA through preloads emphasizes the need for further investigation into this promising training strategy for soccer players. Thus, the occurrence of PAPE in athletes following intense warm-ups remains unclear. Although the individual effect of PAPE on different performance metrics has been investigated [

17], the individual responses of amateur male soccer players on the RAST have not yet been explored. Investigating the potential effects of PAPE on RSA is essential, as enhancing neuromuscular efficiency through preloads could improve repeated sprint performance, which is crucial for success in high-intensity intermittent team sports, such as soccer. This study aimed to investigate the effects of post-activation performance enhancement protocols created using different preloading volumes on repeated sprint ability performance in amateur male soccer players. In this study, it was assumed that PAPE protocols would positively affect the repeated sprint performance of amateur male soccer players.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study was implemented in a double-blind, randomized, two-period crossover study. ABBA method was preferred for the crossover design, and participants performed two different PAPE protocols. The randomization process was conducted using an online Research Randomizer website (Urbaniak G. C. & Plous S. Research Randomizer Version 4.0;

www.randomizer.org), with a 1:1 allocation ratio. The CONSORT Crossover Extension checklist was used to improve reporting quality [

18]. Details of the study checklist are provided in Supplementary Material S1. The study protocol was registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) (DOI: ***blınded for revıew***), and all study documents were made available for open access in the OSF (***blınded for revıew***).

Participants

This study involved 18 male soccer players (mean age: 20.83 ± 0.68 years, mean height: 176.94 ± 1.27 cm, mean weight: 68.6 ± 1.64 kg, mean body mass index: 21.97 ± 0.38 kg/m²) who volunteered to participate in the ***blınded for revıew*** First Amateur Soccer League in ***blınded for revıew***. Participants were selected based on the following criteria: (i) participation in an official match at least once per week, (ii) training a minimum of two days per week during the season, (iii) the ability to perform back squats with a weight of at least 1.50 times their body weight, (iv) a minimum of seven hours of sleep per night, (v) non-smoker status, (vi) abstention from alcohol consumption, and (vii) identification as male soccer players.

A purposive sampling method was used in this study. Effect sizes derived from prior research were utilized for power analysis [

13,

19]. A priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power software (version 3.1, University of Düsseldorf, Germany) based on the following parameters: ANOVA with repeated measures, between-factor test, α = 0.05, β = 0.80, effect size = 0.50, number of groups = 2, number of measurements = 6, and an r-value among repeated measures = 0.40. The power analysis results indicated that a minimum sample size of 18 participants was necessary. All participants provided informed consent, indicating voluntary participation in the study. The study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the ***blınded for revıew*** Non-interventional Clinical Ethics Committee (2023/1266). Details of the participant characteristics are presented in

Table 1.

Experimental Procedures

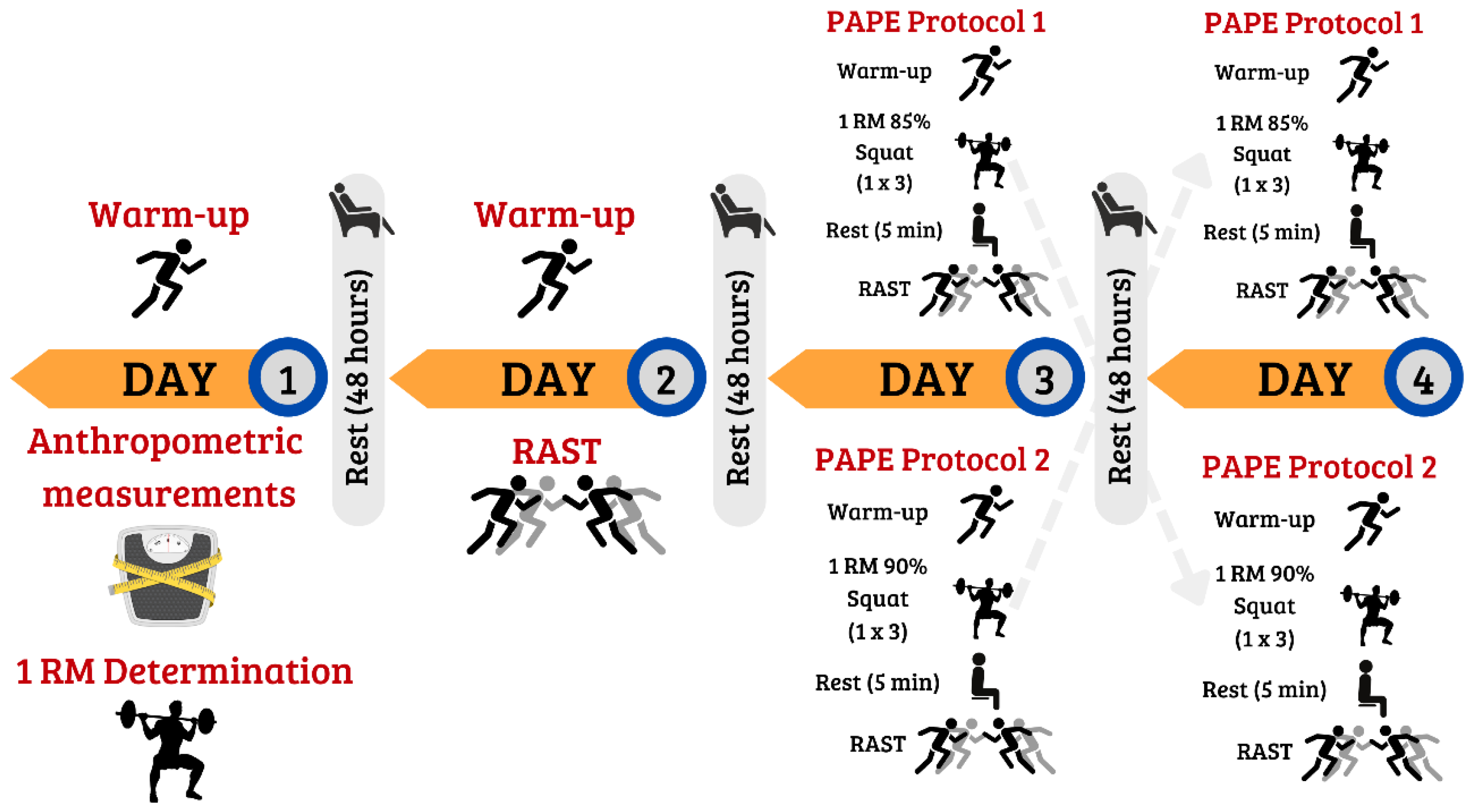

Participants performed four testing sessions with 48 hours of rest. Experimental procedures were conducted based on criteria established by field professionals [

20]. All assessments were performed at consistent times of the day to manage potential physiological and behavioral influences. The study protocol was conducted on a grass field following established standards, under adequate sunlight conditions, with ambient temperatures ranging from 20 to 26°C and relative humidity levels between 45 and 60%. The participants were advised to refrain from engaging in strenuous physical activity before test and training days and to ensure they consumed sufficient carbohydrates to mitigate the impact of fatigue. On the initial day of the study, an informational meeting was conducted to allow participants to discuss the study protocol and associated exercises. All participants were briefed on the assessments to mitigate the risk of learning bias. Care was taken to avoid disclosing information that could potentially compromise the integrity of the study results, such as specifics regarding the control and experimental protocols. Participants were assured that they had the autonomy to withdraw from the study at any time should they choose to do so. After obtaining the descriptive characteristics of all participants, standardized a warm-up protocol was applied [

17], and 1 RM was determined according to the researcher

s’ recommendations [

21]. RAST was performed after the warm-up protocol on the second day of the study. On the third day, soccer players performed the RAST test 5 minutes after the preload stimulus, which consisted of 1 set of 3 repetitions of the back squat at 85% of their 1 RM. On the fourth day, soccer players performed the RAST test 5 minutes after the preload stimulus, which consisted of 1 set of 3 repetitions of the back squat at 90% of their 1 RM. Participants were instructed to refrain from eating for 1.5 hours before the measurement time. Athletes were allowed to drink water (500ml) during the test and were verbally motivated during the RAST. The study protocol was overseen by a researcher with expertise in strength conditioning, while the test results remained concealed from this expert. Other researchers documented the test results in an Excel spreadsheet, and the analyses were conducted by a separate researcher who was also blinded to the study protocol.

Figure 1.

The experimental design of study. Legend. BS85%: Smith machine back squat 85% of 1 RM; BS90%: Smith machine back squat 90% of 1 RM; PAPE: Post activation performance enhancement; min: Minute; RAST: Running anaerobic sprint test.

Figure 1.

The experimental design of study. Legend. BS85%: Smith machine back squat 85% of 1 RM; BS90%: Smith machine back squat 90% of 1 RM; PAPE: Post activation performance enhancement; min: Minute; RAST: Running anaerobic sprint test.

Measurements

Determination of Heart Rate

During RAST performance, participant

s’ maximum (HR

max) and mean (HR

mean) heart rates were monitored using a heart rate sensor (H10, Polar Electro, Oy, Kempele, Finland). Two researchers performed measurements on a grass field. The researchers reported the H10 heart rate sensor with a sampling rate of 1000 Hz to have high validity (

r = 0.86 to 0.95), reliability (ICC = 0.85 to 0.95), and average bias (Bland Altman = -0.7 to 0.4 ms) [

22].

Rate of Perceived Exertion

After the RAST, the participants individually indicated their perceived exertion (RPE) score using the CR-10 Borg scale to assess the subjective intensity of the test. This scale ranges from 0 to 10, where 0 signifies ‘not tired at all’ and 10 represents ‘very difficult (maximum)’ [

23].

Smith Machine Back Squat 1 Repetition Maximum Test

1RM squat test was conducted according to the criteria established by researchers [

21]. The 1RM back squat values were assessed using a Smith machine with the squat depth set to a knee joint angle ranging from 85° to 90° (where full extension corresponds to a 180-degree knee angle). This depth was maintained throughout the PAPE protocol. After a 5-minute walk, participants completed the warm-up procedure with 8-10 repetitions of Smith machine back squats using an empty barbell weighing 20 kg. Following the warm-up, they performed 3-5 repetitions at 60-80% of their estimated 1RM weight, followed by a 2-minute rest. In the third phase, the weight was increased to a level that allowed to 2-3 repetitions to be completed, corresponding to 90-95% of the estimated 1RM. A rest interval of 4 min was provided before the final 1RM attempt, during which the maximum lifted weight was recorded. The 1RM value was conducted over to 4-5 phases.

PAPE Protocol

No preloads were applied during the baseline protocol. On the third day, participants performed three repetitions, with 30-second rest intervals, at 85% of their one-repetition maximum (1 RM) on the Smith machine back squat after a proper warm-up [

17]. On the fourth day, they executed three repetitions, again with 30-second rest intervals, at 90% of their 1 RM on the Smith machine back squat following a warm-up. The movements were performed with the feet positioned shoulder-width apart and were controlled. The participants were instructed to keep their feet on the ground and squat until their knees formed a 90° angle. The location where the athletes reached the predetermined angle was marked with a resistance band and the movement was completed by engaging the hamstring muscle group [

24].

RAST Protocol

Following the PAPE protocol, participants were given a 5-minute rest interval before starting the test [

16]. RAST was performed on a turf field with soccer cleats. The researchers reported that RAST was highly reliable (ICC = 0.88 to 0.96) for soccer players and could be applied on turf fields [

25]. Soccer players performed six consecutive 35-m linear sprints at maximum speed with 10-second rest intervals. Linear sprint time was recorded every 35 m using timing gates (Smartspeed timing gate system–Fusion Sport™, Australia) sampling at 1000 Hz and error-correcting sampling algorithms [

26]. No information about the participant

s’ degree was disclosed until the study was completed to eliminate the placebo effect.

Statistical Analysis

The analyses were conducted using descriptive statistics and visual-analysis techniques. The normality assumption of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, while potential outliers affecting the dataset were evaluated through a sensitivity analysis. The impact of the three experimental conditions on RAST metrics was examined using one-way ANOVA, and the homogeneity of variances was assessed with the Levene test. The effect of experimental conditions on RAST performance was analyzed using a repeated measures ANOVA, while a two-way repeated measures ANOVA was employed to evaluate the interaction between time and condition. The assumption of sphericity was tested using Mauchl

y’s test, and the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied in cases of sphericity violation. If the F ratio was significant,

post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted with Bonferroni correction. Partial eta squared (η²) and omega squared (ω²) values were used to interpret the effect sizes. Eta squared, and omega squared were interpreted according to the following benchmarks: 0.01 = small effect, 0.06 = medium effect, and 0.14 = large effect [

27]. Participant

s’ individual RAST responses to the experimental conditions were evaluated using Mann-Kendall trend analysis, and Monte Carlo simulation was applied with 1000 resamplings to increase the statistical power of the findings. All statistical analyses were conducted at a significance level of α = 0.05. The analyses were performed using R software (version 4.1.0, R Core Team, Australia) utilizing the {ggstatsplot}, {rstatix}, {ggpubr}, {patchwork}, and {tidyverse} packages. The details of R code lines and dataset were presented via OSF

(***BLINDED FOR REVIEW***).

3. Results

The Results for İntervention Adherence and Potential Moderators

Eighteen amateur male soccer players participated in this study. All participants demonstrated 100% adherence to the testing sessions, and no injuries occurred due to the study protocol.

Three potential variables affecting participant

s’ RAST performance (HRmean, HRmax, and RPE score) were evaluated for three experimental conditions (control, BS85%, and BS90%). The results revealed no statistically significant differences among potential moderators across the three experimental conditions (

F2,51 = 0.31 to 0.51,

p = 0.57 to 0.73). The details regarding the potential moderators are presented in

Table 2.

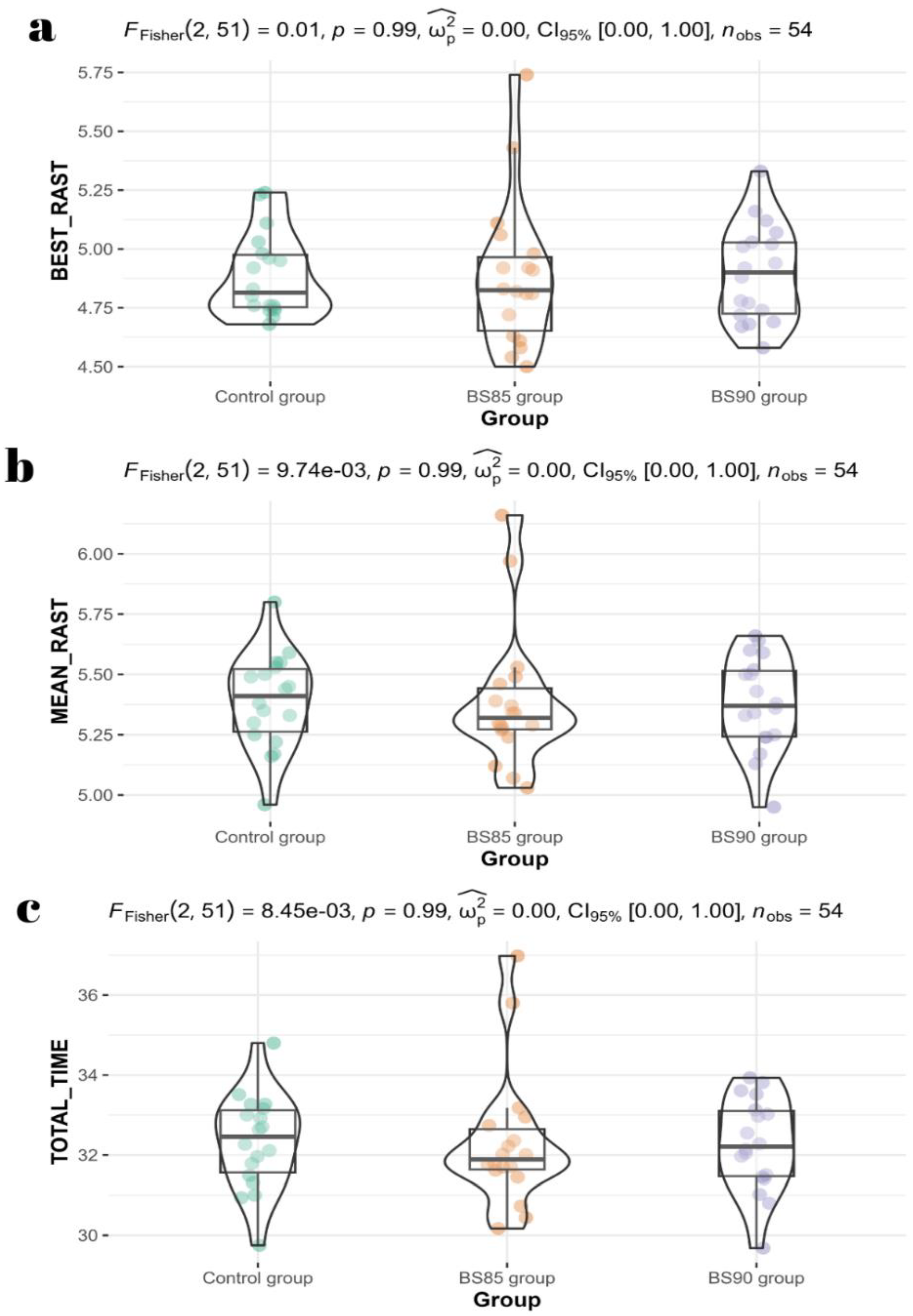

The Results Based on RAST Metrics

One-way ANOVA indicated that there was no statistically significant difference in the RAST

best scores of amateur male soccer players under the three experimental conditions (i.e., control, BS85%, and BS90%) (

F2,51 = 0.01; ω² = 0.00, 95%CI = 0.00 to 1.00;

p = 0.99). Similar results were also found in RAST

mean (

F2,51 = 0.00; ω² = 0.00, 95%CI = 0.00 to 1.00;

p = 0.99) and RAST

total time (

F2,51 = 0.00; ω² = 0.00, 95%CI = 0.00 to 1.00;

p = 0.99). These results revealed that the RAST metric means of amateur male soccer players were statistically similar under the three experimental conditions. Details of the analysis results for the RAST metrics are presented in

Figure 2, and the descriptive statistics used for the analysis are provided in Supplementary Material S2.

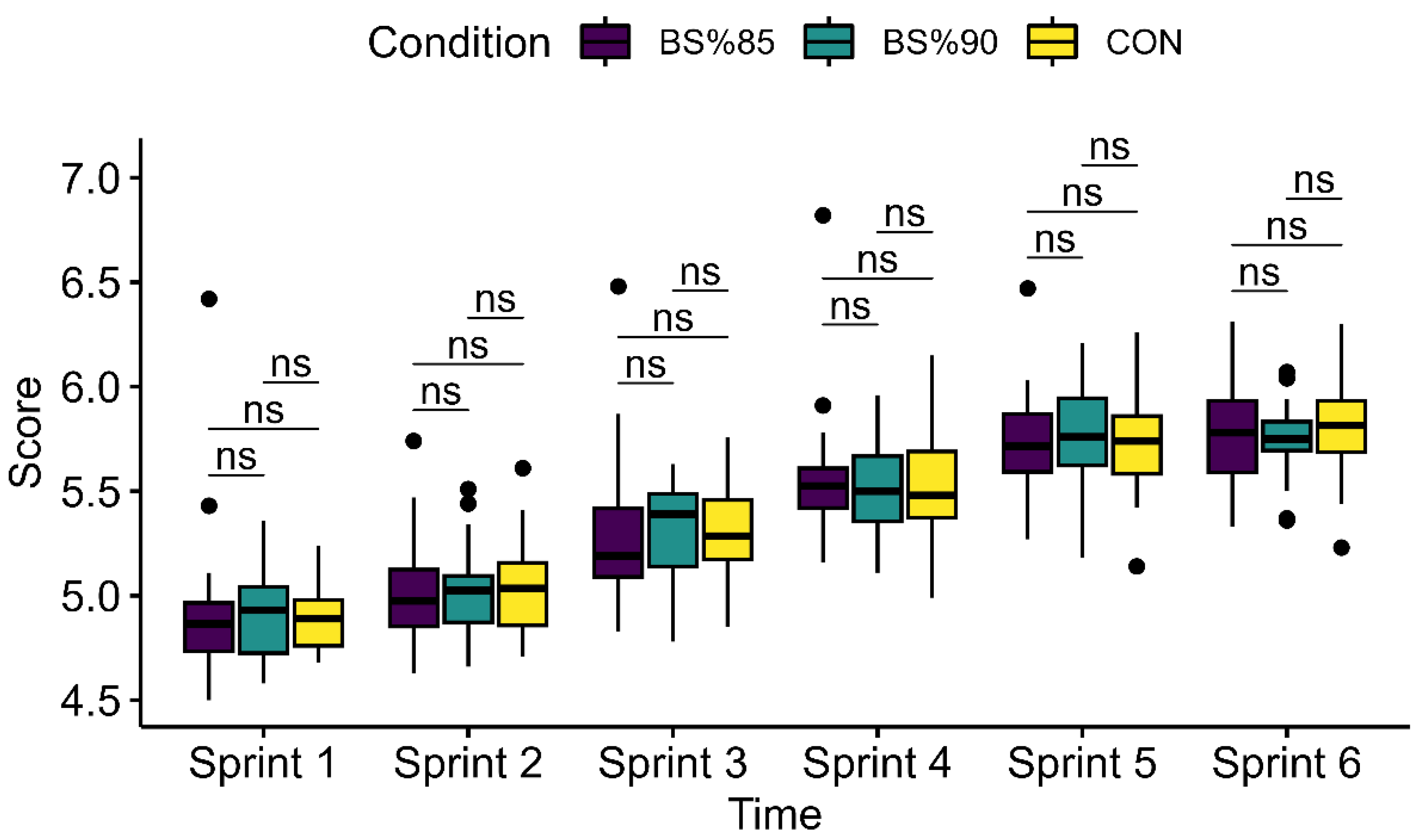

The Results Based on Time:Condition İnteraction

The two-way ANOVA showed that the main effect of time (i.e., six linear sprints applied for RAST) had a statistically significant difference (F5, 75 = 187.96, p = 0.01, η² = 0.71). However, the main effect of the three experimental conditions (F2, 30 = 1.59, p = .221, η² = 0.01) and the time:condition interaction did not have a statistically significant difference (F10, 150 = 0.78, p = 0.65, η² = 0.01).

The time main effect and time:condition interaction were understood to violate the assumption of sphericity (Time: W = 0.077,

p = 0.01; Time:condition: W = 0.00,

p = 0.02), and Greenhouse-Geisser (GG) correction was applied. GG correction showed a significant effect for the time main effect (

F2.5, 37.46 = 187.96,

p = 0.01), while the time:condition interaction was not significant after GG correction (F

5.19,77.79 = 0.78,

p = 0.57). The analysis revealed a significant main effect of time, but no significant effect on the condition or time:condition interaction. The details of the two-way ANOVA are presented in

Figure 3.

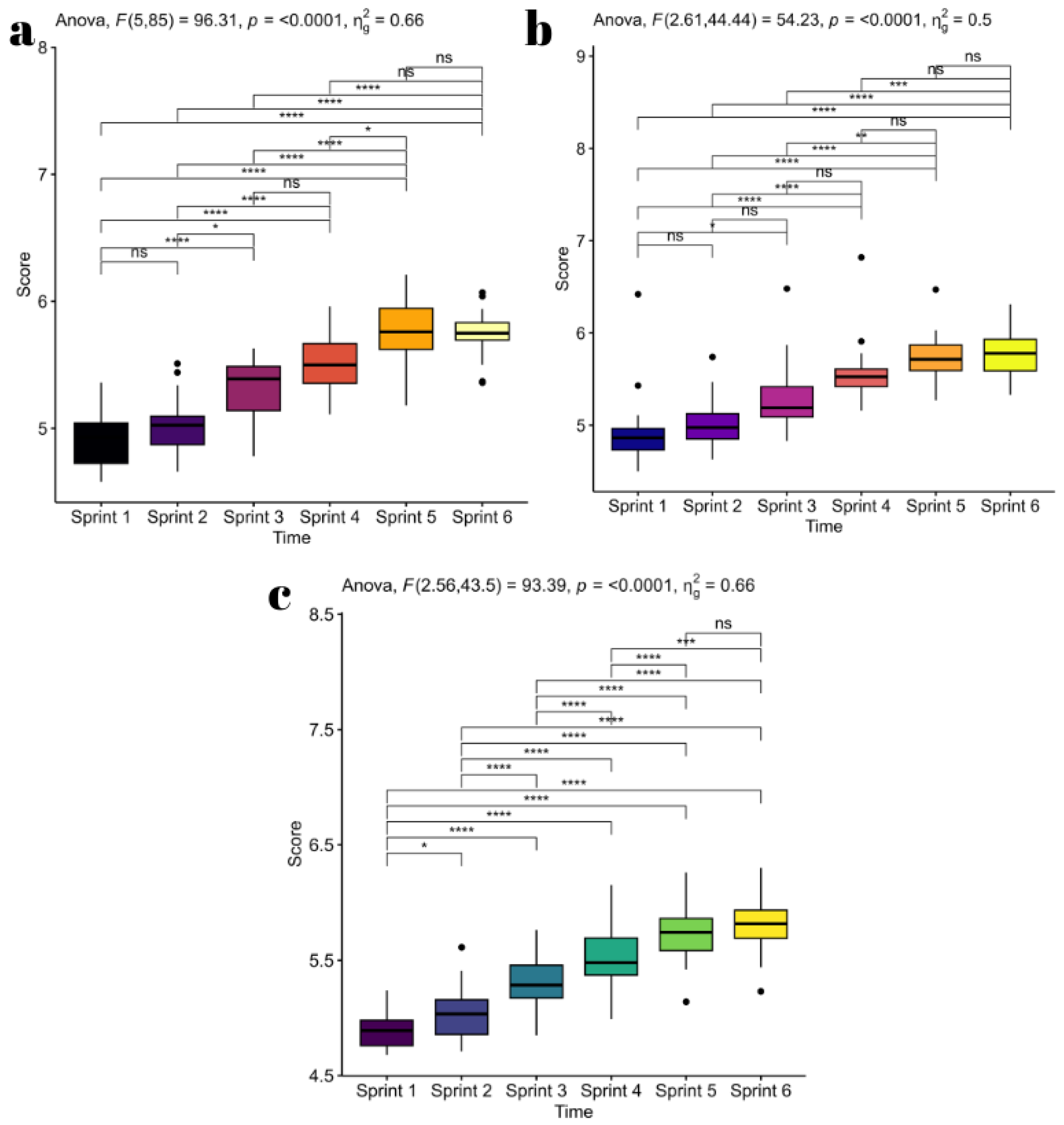

The Results Based on the Sprint Time of the Groups

Repeated-measures ANOVA showed that time had a statistically significant effect on RAST performance in the control group (

F5, 85 = 96.31,

p = 0.01, η² = 0.66). Although the results indicated a violation of sphericity, similar results emerged after the GG correction (

F2.56,43.5 = 93.39,

p = 0.01). Pairwise

post hoc analyses showed that linear sprint performance decreased gradually from Sprint 1 to Sprint 5 (

t = -4.06 to -11.80,

df =17,

p = 0.01 to 0.04). No statistically significant differences were found between Sprint 5 and 6 (

t = -1.10,

df = 17,

p = 1.00). Details of the control group’ repeated measures ANOVA and post hoc analysis are presented in

Figure 4c.

On the other hand, the time factor had a statistically significant effect on RAST performance in the BS85% group (

F5, 85 = 54.23,

p = 0.01, η² = 0.49). Mauchl

y’s test showed that the assumption of sphericity was violated (W = 0.032,

p = 0.01), while after the GG correction, the time factor was found to be significant (

F2.61,44.44 = 54.23,

p = 0.01, η² = 0.50). Post hoc analyses also determined that sprint performance significantly decreased over time for the BS85% group (

p < 0.05). However, there were no statistically significant difference (

p > 0.05) between consecutive sprints (sprint 1 vs. 2, sprint 2 vs. 3, sprint 3 vs. 4, sprint 4 vs. 5, and sprint 5 vs. 6). Details of the BS85% group’ repeated measures ANOVA and post hoc analysis are presented in

Figure 4b.

The time factor also had a statistically significant effect on RAST performance in the BS90% group (

F5, 85 = 96.31,

p = 0.01, η² = 0.66). Mauchl

y’s test revealed that the assumption of sphericity was not violated (W = 0.39,

p = 0.46). Post hoc analyses reported no statistically significant differences (

p > 0.05) for the three sprint pairs in the BS90% group (sprint 1 vs. 2; sprint 3 vs. 4; sprint 5 vs. 6). Details of the repeated measures ANOVA and post hoc analysis of the BS90% group are presented in

Figure 4a. Also, descriptive statistics of all groups for repeated measures of ANOVA are provided in Supplementary Material

S3 and Supplementary Material

S4.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effects of post-activation performance-enhancing protocols created using different preload volumes on amateur male soccer players’ repeated sprint ability performance. Although the results revealed that the time: condition interaction was not statistically significant, the main effect of time significantly affected the RAST performance of the groups. The results revealed that RAST responses of soccer players varied across experimental conditions, highlighting the importance of individual differences. However, heart rate and RPE did not affect RAST performance in this study. While the repeated sprint ability in the control group gradually deteriorated with each RAST sprint, the performance decrease in the RAST sprints of the experimental groups was less compared to the control group. While no statistically significant difference was found for the consecutive sprint comparisons of the BS85% group (sprint one vs. two; sprint two vs. three, etc.), no statistically significant difference was observed in the BS90% group at the three sprint levels (sprint one vs. two; sprint three vs. four; sprint five vs. six).

It was assumed that the fatigue experienced during each sprint during the RAST would decrease the performance of soccer players. The analyses supported this hypothesis by revealing that the main effect of time was statistically significant. However, statistically insignificant results were observed in the main effect of time in the experimental groups during the RAST comparisons within the group. Therefore, it is considered that PAPE may improve repeated sprint ability by increasing muscle resistance to fatigue. The mechanisms underlying these effects include neural and muscular interactions and alterations in muscle architecture [

15]. These mechanisms include phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chains, recruitment of higher-order motor units, and modifications in the muscle pennation angle [

28]. This effect is likely mediated by increased muscle strength and enhanced neural excitability [

15]. These findings align with previous studies, suggesting that preloading can enhance repeated sprint performance by increasing muscle resistance to fatigue [

19,

29].

The study findings revealed results that contradicted the idea that near-maximal preloads are more effective in eliciting the PAPE effect [

15,

30]. The BS85% group did not show statistically significant differences in consecutive sprint comparisons, whereas the BS90% group did not show statistically significant differences in only three sprint levels. These results suggest that the lower preload PAPE protocol may further inhibit fatigue during the RAST. This result can be explained by the loading and rest relationship. The recovery time between the completion of the PAPE warm-up and RAST in the BS90% group may not have been sufficient for optimal fatigue distribution [

16,

31]. On the other hand, according to a classification based on the ratio of 1RM back squat values to body mass, the participants in our study had poor strength levels [

16]. Therefore, fatigue accumulation may have masked the PAPE effect to a greater extent in the BS90% group. Researchers have reported that preloads performed with heavy loads may cause neuromuscular fatigue, negatively affecting subsequent performance [

32]. Therefore, a lower preload may have provided sufficient stimulus for the performance of soccer players. Many previous studies have claimed that performance can be improved with a lower preload [

32,

33].

Although the main effect of time was statistically significant, the time-condition interaction between the experimental (BS85% and BS90%) and control groups was not statistically significant. Also, the groups were similar in terms of RASTmean (

p = 0.99), RASTbest (

p = 0.99), RASTtotal time (

p = 0.99). These results can primarily be attributed to statistical power. The researchers reported that analyses without sufficient statistical power are prone to Type I error [

34]. This study selected athletes with different competition levels for power analysis [

13,

19]. The findings of previous studies may not apply to the present participants. The nonsignificant difference in the time-condition interaction may also be associated with the RAST responses of amateur athletes during the PAPE protocol. Although previous studies claimed that PAPE could improve RAST performance, it was reported to have a nonsignificant or negligible effect on amateur athletes [

13]. Therefore, it was assumed that the absence of a significant difference between the groups in our study is consistent with the existing literature.

This study was the first to examine the individual RAST responses of soccer players during PAPE protocols. Twelve soccer players exhibited varying RAST responses during PAPE. These results may suggest that the time-condition interaction leads to insignificant outcomes. It is well-established that individual differences influence the PAPE phenomenon [

9,

11,

15]. Factors such as VO2max, time constant, and physiological biomarkers may also impact the RAST performance of amateur soccer players [

35]. These variables create limitations in accurately assessing the effect of PAPE on RAST performance.

This study has several limitations. The first limitation pertains to the rest period. Researchers have reported that individuals with high strength experience the greatest PAPE effect after 5 to 7 minutes of preload, while those with lower strength require at least 8 minutes of recovery [

36]. Since the current study implemented a 5-minute rest period for PAPE in weaker individuals, future research could evaluate the effects of PAPE on RAST with longer rest intervals. Additionally, male amateur soccer players with low strength levels were included in this study. The study protocol could also be applied to soccer players with higher strength levels. Beyond the factors influencing the PAPE phenomenon, numerous mediating variables can affect RAST performance in team sports [

37,

38,

39,

40]. This study determined that mediators such as heart rate and perceived exertion did not significantly impact performance. However, future studies could assess mediating variables such as VO2max and blood biomarkers to understand the relationship between PAPE and RAST better. Finally, movement speed may also influence preload protocols [

41]. Therefore, future research could confirm the effects of performing half squats versus full squats and the outcomes of varying the number of sets and types of exercises.

5. Conclusions

As a result, this study revealed that PAPE protocols may have a potential fatigue-delaying effect on RAST performance in amateur male soccer players. Furthermore, it was understood that preloading at 85% of 1RM may be as effective as preloading at 90% of 1RM to increase performance. It is well known that individual differences during PAPE affect jumping, agility, and strength performance. This study also found that individual differences affect the relationship between PAPE and RAST performance. Furthermore, it was determined that mediators such as heart rate and perceived exertion did not affect these results. Therefore, it was emphasized that physiological markers may also be important in the relationship between PAPE and RAST. The current study findings may provide valuable insights for coaches, field experts, and practitioners to consider when creating match strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at Preprints.org: ***BLINDED FOR REVIEW***.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Ş.A. and H.Ş.U.; methodology, M.Ş.A., H.Ş.U., T.Ç. and D.I.T.; software, M.Ş.A., H.Ş.U., N.A. and L.I.P.; validation, M.Ş.A., N.A., D.I.T., L.I.P. and C.I.A.; formal analysis, M.Ş.A., H.Ş.U. and N.A.; investigation,T.Ç and N.A.; resources, T.Ç., N.A., D.I.T., L.I.P. and C.I.A.; data curation, M.Ş.A., D.I.T., L.I.P. and C.I.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Ş.A., H.Ş.U. and T.Ç.; writing—review and editing, M.Ş.A.; H.Ş.U., N.A., D.I.T., L.I.P. and C.I.A.; visualization, M.Ş.A., H.Ş.U., N.A., D.I.T., L.I.P. and C.I.A.; supervision, M.Ş.A.; H.Ş.U., D.I.T. and C.I.A.; project administration, M.Ş.A.; H.Ş.U. and C.I.A.; funding acquisition, D.I.T., L.I.P. and C.I.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the ***BLINDED FOR REVIEW*** Non-interventional Clinical Ethics Committee (2023/1266).

Data Availability Statement

Open access to the data is presented available through OSF (***BLINDED FOR REVIEW***)

Acknowledgments

We want to thank graduate students Kerem Can Yıldız and Sezer Tanrıöver for their contributions to our study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Reynolds, J.; Connor, M.; Jamil, M.; Beato, M. Quantifying and Comparing the Match Demands of U18, U23, and 1ST Team English Professional Soccer Players. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 706451. [CrossRef]

- Balsom, P.D.; Seger, J.Y.; Sjodin, B.; Ekblom, B. Maximal-Intensity Intermittent Exercise: Effect of Recovery Duration. Int. J. Sports Med. 1992, 13, 528–533. [CrossRef]

- Spencer, M.; Lawrence, S.; Rechichi, C.; Bishop, D.; Dawson, B.; Goodman, C. Time-Motion Analysis of Elite Field Hockey, with Special Reference to Repeated-Sprint Activity. J. Sports Sci. 2004, 22, 843–850. [CrossRef]

- Rampinini, E.; Bishop, D.; Marcora, S.M.; Ferrari Bravo, D.; Sassi, R.; Impellizzeri, F.M. Validity of Simple Field Tests as Indicators of Match-Related Physical Performance in Top-Level Professional Soccer Players. Int. J. Sports Med. 2007, 28, 228–235. [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, M.; Simpson, B.M.; Hader, K.; Lacome, M. Occurrences of Near-to-Maximal Speed-Running Bouts in Elite Soccer: Insights for Training Prescription and Injury Mitigation. Sci. Med. Footb. 2021, 5, 105–110. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L.; Clemente, F.M.; Barrera, J.I.; Sarmento, H.; González-Fernández, F.T.; Rico-González, M.; Carral, J.M.C. Exploring the Determinants of Repeated-Sprint Ability in Adult Women Soccer Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, Vol. 18, Page 4595 2021, 18, 4595. [CrossRef]

- Osses-Rivera, A.; Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R.; Jannas-Vela, S.; Vigh-Larsen, J.F.; Monsalves-Álvarez, M. Effects of Strength Training on Repeated Sprint Ability in Team Sports Players: A Systematic Review. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17756. [CrossRef]

- Towlson, C.; Midgley, A.W.; Lovell, R. Warm-up Strategies of Professional Soccer Players: Practitioners’ Perspectives. J. Sports Sci. 2013, 31, 1393–1401. [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, M.; Docherty, D.; Robbins, D. Post-Activation Potentiation: Underlying Physiology and Implications for Motor Performance. Sport. Med. 2005, 35, 585–595. [CrossRef]

- Till, K.A.; Cooke, C. The Effects of Postactivation Potentiation on Sprint and Jump Performance of Male Academy Soccer Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 1960–1967. [CrossRef]

- Blazevich, A.J.; Babault, N. Post-Activation Potentiation versus Post-Activation Performance Enhancement in Humans: Historical Perspective, Underlying Mechanisms, and Current IssuesPost-Activation Potentiation versus Post-Activation Performance Enhancement in Humans: Historical Perspective, Underlying Mechanisms, and Current Issues. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1359. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.J.H.; Kong, P.W. Effects of Isometric and Dynamic Postactivation Potentiation Protocols on Maximal Sprint Performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 2730–2736. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Sanchez, J.; Rodriguez, A.; Petisco, C.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Martínez, C.; Nakamura, F.Y. Effects of Different Post-Activation Potentiation Warm-Ups on Repeated Sprint Ability in Soccer Players from Different Competitive Levels. J. Hum. Kinet. 2018, 61, 189–197. [CrossRef]

- Silva-Neto, M.E.; Oliveira, S.F.M.; Oliveira, J.I. V.; Gomes, W.S.; Lira, H.A.A.S.; Fortes, L.S. Acute Effects of Different Conditioning Activities on Amateur Soccer Players. Int. J. Sports Med. 2023, 44, 882–888. [CrossRef]

- Tillin, N.A.; Bishop, D. Factors Modulating Post-Activation Potentiation and Its Effect on Performance of Subsequent Explosive Activities. Sport. Med. 2009, 39, 147–166. [CrossRef]

- Seitz, L.B.; Haff, G.G. Factors Modulating Post-Activation Potentiation of Jump, Sprint, Throw, and Upper-Ody Ballistic Performances: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sport. Med. 2016, 46, 231–240. [CrossRef]

- Sari, C.; Koz, M.; Salcman, V.; Gabrys, T.; Karayigit, R. Effect of Post-Activation Potentiation on Sprint Performance after Combined Electromyostimulation and Back Squats. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1481. [CrossRef]

- Dwan, K.; Li, T.; Altman, D.G.; Elbourne, D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Extension to Randomised Crossover Trials. BMJ 2019, 366. [CrossRef]

- Okuno, N.M.; Tricoli, V.; Silva, S.B.C.; Bertuzzi, R.; Moreira, A.; Kiss, M.A.P.D.M. Postactivation Potentiation on Repeated-Sprint Ability in Elite Handball Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 662–668. [CrossRef]

- American College of Sports Medicine ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription - American College of Sports Medicine - Google Kitaplar; 9th ed.; Wolters Kluwer, 2022;

- Haff, G.; Triplett, N. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning 4th Edition. 2015.

- Schaffarczyk, M.; Rogers, B.; Reer, R.; Gronwald, T. Validity of the Polar H10 Sensor for Heart Rate Variability Analysis during Resting State and Incremental Exercise in Recreational Men and Women. Sensors 2022, 22, 6536. [CrossRef]

- Borg, E.; Kaijser, L. A Comparison between Three Rating Scales for Perceived Exertion and Two Different Work Tests. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2006, 16, 57–69. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, K.W.; Chen, J.R.; Chow, J.J.; Tseng, W.C.; Condello, G.; Tai, H.L.; Fu, S.K. Post-Activation Performance Enhancement after a Bout of Accentuated Eccentric Loading in Collegiate Male Volleyball Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18. [CrossRef]

- De Andrade, V.L.; Pereira Santiago, P.R.; Kalva Filho, C.A.; Zapaterra Campos, E.; Papoti, M. Reproducibility of Running Anaerobic Sprint Test for Soccer Players. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2014, 56, 34–38.

- Altmann, S.; Ringhof, S.; Becker, B.; Woll, A.; Neumann, R. Error-Correction Processing in Timing Lights for Measuring Sprint Performance: Does It Work? Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 1400–1402. [CrossRef]

- Gepfert, M.; Golas, A.; Zajac, T.; Krzysztofik, M. The Use of Different Modes of Post-Activation Potentiation (PAP) for Enhancing Speed of the Slide-Step in Basketball Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, Vol. 17, Page 5057 2020, 17, 5057. [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.J.; Ditroilo, M.; Marshall, P.A. Complex Training: The Effect of Exercise Selection and Training Status on Postactivation Potentiation in Rugby League Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 2694–2703. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M.; Duncan, N.M.; Marin, P.J.; Brown, L.E.; Loenneke, J.P.; Wilson, S.M.C.; Jo, E.; Lowery, R.P.; Ugrinowitsch, C. Meta-Analysis of Postactivation Potentiation and Power: Effects of Conditioning Activity, Volume, Gender, Rest Periods, and Training Status. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 854–859. [CrossRef]

- Fukutani, A.; Takei, S.; Hirata, K.; Miyamoto, N.; Kanehisa, H.; Kawakami, Y. Influence of the Intensity of Squat Exercises on the Subsequent Jump Performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 2236–2243. [CrossRef]

- Bevan, H.R.; Cunningham, D.J.; Tooley, E.P.; Owen, N.J.; Cook, C.J.; Kilduff, L.P. Influence of Postactivation Potentiation on Sprinting Performance in Professional Rugby Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 701–705. [CrossRef]

- Kobal, R.; Pereira, L.A.; Kitamura, K.; Paulo, A.C.; Ramos, H.A.; Carmo, E.C.; Roschel, H.; Tricoli, V.; Bishop, C.; Loturco, I. Post-Activation Potentiation: Is There an Optimal Training Volume and Intensity to Induce Improvements in Vertical Jump Ability in Highly-Trained Subjects? J. Hum. Kinet. 2019, 66, 195. [CrossRef]

- Evetovich, T.K.; Conley, D.S.; McCawley, P.F. Postactivation Potentiation Enhances Upperand Lower-Body Athletic Performance in Collegiate Male and Female Athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 336–342. [CrossRef]

- Abt, G.; Boreham, C.; Davison, G.; Jackson, R.; Nevill, A.; Wallace, E.; Williams, M. Power, Precision, and Sample Size Estimation in Sport and Exercise Science Research. J. Sport. Sci. 2020, 38, 1933–1935. [CrossRef]

- Rampinini, E.; Sassi, A.; Morelli, A.; Mazzoni, S.; Fanchini, M.; Coutts, A.J. Repeated-Sprint Ability in Professional and Amateur Soccer Players. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2009, 34, 1048–1054. [CrossRef]

- Seitz, L.B.; Trajano, G.S.; Haff, G.G. The Back Squat and the Power Clean: Elicitation of Different Degrees of Potentiation. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2014, 9, 643–649. [CrossRef]

- Modric, T.; Versic, S.; Alexe, D.I.; Gilic, B.; Mihai, I.; Drid, P.; Radulovic, N.; Saavedra, J.M.; Menjibar, R.B. Decline in Running Performance in Highest-Level Soccer: Analysis of the UEFA Champions League Matches. Biology 2022, 11, 1441. [CrossRef]

- Čović, N.; Čaušević, D.; Alexe, C.I.; Rani, B.; Dulceanu, C.R.; Abazović, E.; Lupu G.S.; Alex,D.I. Relations between specific athleticism and morphology in young basketball players, Frontiers in Sports and Active Living. 2023, vol.5. doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2023.1276953.

- Čaušević, D.; Rani, B.; Gasibat, Q.; Čović, N.; Alexe, C.I.; Pavel, S.I.; Burchel, L.O.; Alexe, D.I. Maturity-Related Variations in Morphology, Body Composition, and Somatotype Features among Young Male Football Players. Children 2023, 10, 721. [CrossRef]

- Curțianu, I.M.; Turcu, I.; Alexe, D..; Alexe, C.I.; Tohănean D.I. Effects of Tabata and HIIT Programs Regarding Body Composition and Endurance Performance among Female Handball Players, Balneo and PRM Research Journal. 2022, 13(2): 500.

- Turner, A.P.; Bellhouse, S.; Kilduff, L.P.; Russell, M. Postactivation Potentiation of Sprint Acceleration Performance Using Plyometric Exercise. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 343–350. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).