1. Introduction

Robot-assisted (RA) surgery is gaining ground in the treatment of operable lung cancer (LC) [

1,

2,

3,

4]. For early-stage LC, recommendations call for minimally invasive approaches, among which RA surgery is one of these minimally invasive methods. In addition to understand the clinical benefits of these innovative technologies, we believe it is important to assess their potential risks and complications.

The diffusion of any new surgical method requires a learning curve assessment to estimate a threshold at which the technology is mastered by surgeons. Recently, systematic literature reviews have estimated the threshold of the learning curve [

5], most of the articles used the duration of the procedure, conversions, and intraoperative complications as criteria [

6,

7]. At this stage in the dissemination of RA thoracic surgery, we felt it was important to analyse the results in terms of postoperative quality indicators, rather than focusing solely on intraoperative criteria. The recent meta-analysis estimated that an average of 25 procedures were needed to validate the learning curve [

5].

Based on this literature data, we aim to verify that the threshold of a minimum of 25 procedures guarantees patients quality care with an acceptable rate of postoperative complications. As an indicator, we used post operative complications and/or mortality occurring in the 30 days following the procedure. To assess postoperative complication, we used the Clavien-Dindo classification, which is widely accepted in the literature [

8].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the learning curve threshold of hospitals that performed at least 25 procedures for lung cancer resections by RA Thoracic Surgery using the Clavien-Dindo classification as the judgment criterion.

2. Materials and Methods

The French national hospital database (PMSI) was inspired by the US Medicare system. This database provides detailed medical information on all admissions to public and private hospitals in France, including discharge diagnoses according to the tenth edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) [

9,

10] and medical procedures coded according to the Common Classification of Medical Procedures (CCAM).

From this database, we included all patients with a pulmonary resection between 2019 and 2022. These patients were identified through a principal discharge diagnosis of LC (ICD-10 code C34), associated with a procedure of LC surgery (CCAM codes) [

11] of RA Thoracic Surgery during the same hospital stay. For all patients, LC was established by pathological analysis according to the World Health Organization’s 2004 classification of lung tumors [

9].

2.1. Patient Characteristics

At baseline, we identified for all patients age and gender, but also surgery-related variables such as the surgical approach the type of resection (limited resection, lobectomy). We also included comorbidities such as pulmonary disease (chronic bronchitis, emphysema), heart disease (coronary artery disease, cardiac arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, valvular heart disease, pulmonary artery hypertension, pulmonary embolism), peripheral vascular disease, liver disease, cerebrovascular events, neurological diseases (hemiplegia or paraplegia), renal disease, hematologic disease (leukemia, lymphoma), metabolic disease (including obesity), anemia, other therapies (preoperative chemotherapy including neoadjuvant therapies, steroids) and infectious disease. Finally, we calculated a modified Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) as a marker of comorbidity [

12]. For the analysis, we selected hospitals that performed at least robot-assisted pulmonary resections.

2.2. Hospital Characteristics

In France, hospitals are classified as either non-academic public, academic public, private non-profit or private for profit. For each hospital, we also calculated the total hospital volume, defined as the number of thoracic procedures performed for LC and the total Robot-assisted procedure during the same period.

2.3. Ethics

Patient consent was not required seeing as the French national hospital data are based on pseudonymised data, i.e., they do not contain any identifying data. Consequently, patient-identifying information was not used. The patient’s identity is pseudonymised, which allows data from the same patient to be linked without knowing the patient’s identity. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the National Committee for data protection: declaration of conformity to the methodology of reference 05 obtained on 7/08/2018 under the number 2,204,633 v0.

2.4. Outcome Measurements

Thirty-Day mortality was defined as deaths that occurred during the surgical stay, but also during a subsequent hospital stay, within 30 days of the surgical admission.

The complication outcome was defined as the presence of one or more of the following postoperative conditions: pain, wound complication, tracheostomy, reintubation, adult respiratory distress syndrome, bronchopleural fistula, empyema, respiratory failure, arrythmia, denutrition, phlebitis, pleural effusion, pulmonary embolus, pneumonia, haemorrhage, myocardial infarction, stroke, lower limb ischemia, sepsis, and heart failure. For the analysis we used the Clavien-Dindo classification for postoperative complications and 30-day mortality [

8].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The clavien-dindo classification was transformed into a binary variable. The new variable was equal to 1 if the clavien-dindo classification was > II.

Descriptive data were expressed as n (%) for qualitative variables and as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables. Means were compared using a parametric test (ANOVA). Categorical variables were compared using Χ2 test. To estimate the predicted risk of failure (clavien-dindo classification > II) we used a logistic regression model. The discriminative ability of the model was expressed by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). The reliability of the model was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test [

13].

We used the sequential probability ratio test (SPRT) and its modification—the risk-adjusted sequential probability ratio test (RA-SPRT) [

14]. In medical practice, SPRT is one of the statistical tests used to monitor the safety of medical interventions (14,15,16). In the LC assessment, SPRT was carried out in several studies [

14,

15,

16]. The graph starts at 0 and is incremented by (1 – Si) for a failure and decremented by Si for a success. The value of Si is defined by the predicted risk of failure for procedure I and the increase in risk that the chart is designed to detect. Boundary lines were constructed to detect in failure rate to a 50% increase in risk (odds ratio, 1.5). False-positive (α) and false-negative (β) error rates was respectively 5% and 20% to build upper (h1) and lower (h0) boundary lines. when the lower boundary line (h0) was crossed by the cumulative outcome curve (Ti), the null hypothesis was accepted, which indicated that an acceptable performance was achieved. To estimate the number of procedures from which a team achieved its learning curve, the SPRT curve had to cross the lower boundary line (h0) which had the Value of -6.838 (α=0.05, β=0.2, odds ratio=1.5). We used the formula described by Rogers et al. to estimate the lower boundary [

14].

Calculations were performed with STATA V.18 statistical software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) and Excel software.

3. Results

Between 2005 and 2020, 3,706 patients were operated on for LC in France using the RA approach. The number of RA procedures has risen steadily over the years, from 195 procedures in 2019 to 1,567 in 2022. Patient’s characteristics for the 4 years are shown in

Table 1. Most comorbidities changed little over the time, except for the variable’s other disease and other treatment, which varied significantly. The CCI score varied significantly (p=0.028) over the time, particularly for score 0 and score ≥3 (

Table 1). The type of lung resection did not vary over the 4 years (

Table 1). Finally, the variation in Clavien-Dindo classification was at the limit of significance (p=0.048), with the greatest fluctuations in group I, group II and group IVa (

Table 1). Thirty-day mortality (group V) decreased in 2022, the rate is 0.6% (

Table 1).

3.1. Hospital Characteristics

The number of teams performing RA procedures has increased steadily from 2019 to 2022, rising from 29 in 2019 to 64 in 2022 (

Table 2). Teams belonging to academic hospitals has performed 46.8% of pulmonary resections by RA surgery in 2022 (

Table 2). We note that the hospitals using RA surgery are high-volume hospitals (

Table 2). Over the period 2019 to 2022, 28 centers performed at least 25 RA procedures (

Table 2). These hospitals will participate in the estimation of the learning curve threshold using the Clavien-Dindo classification.

$: Mean (Standard deviation), Frequency (Percent%), $$: median [1er Quartile-3eme Quartile].

3.2. Predicted Risk Model

The total number of patients with Clavien-dindo classification > II was 833 (24.7%). The logistic regression model is reported in supplementary material (S1). In the model, we included 17 variables (supplementary material S1). This model had good performance with AUC ROC of 0.887. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was non significant for this model (Chi2 9.85, p=0.275).

3.3. Threshold of the Learning Curve

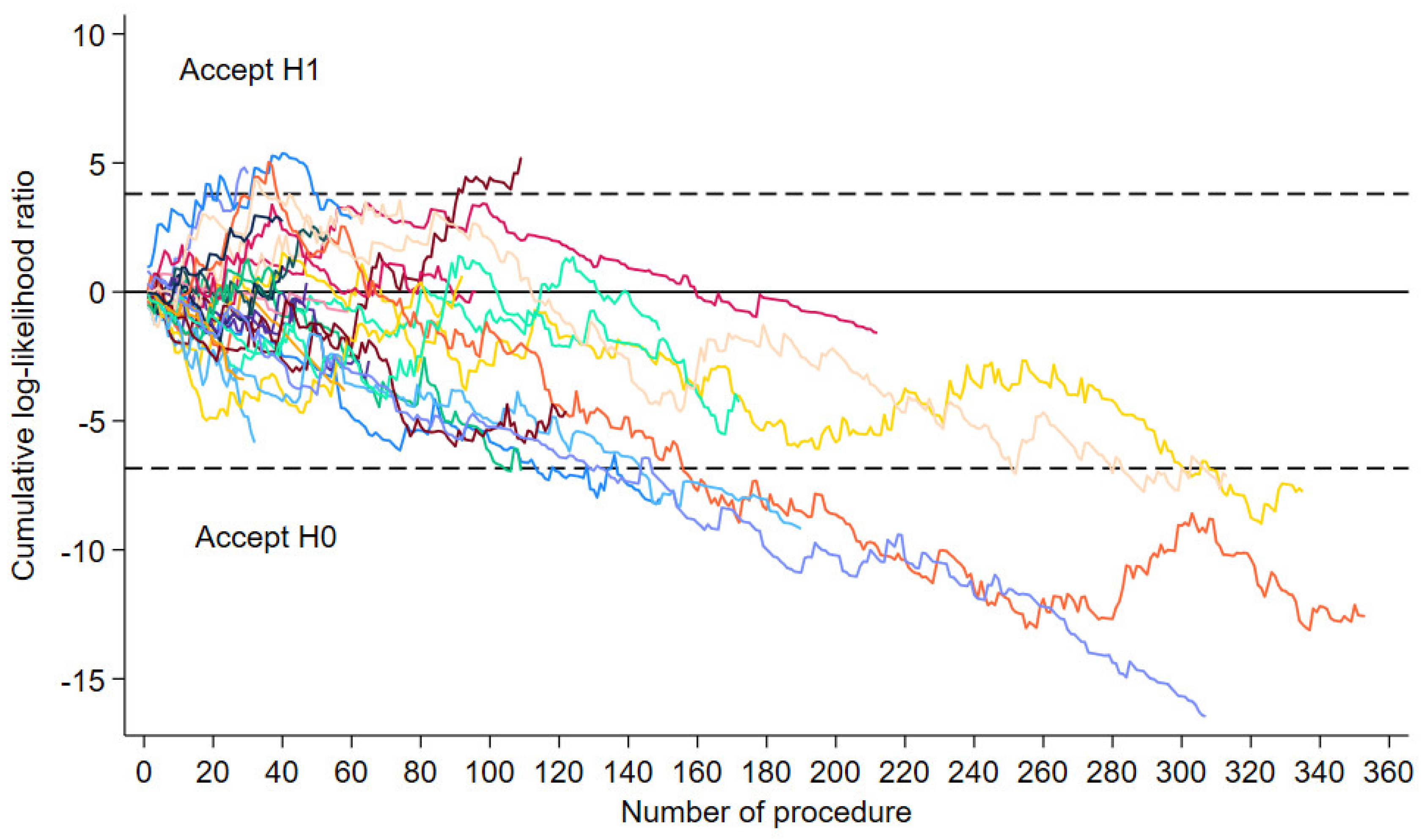

The sequential probability ratio test (SPRT) graphs of the 28 hospitals that performed at least 28 procedures are shown in

Figure 1. Among the 28 hospitals, 8 hospitals achieved their learning curve as the graph crossed the lower boundary line. The learning curve threshold for the 8 hospitals ranged from 94 to 174 procedures, with a median of 110 procedures. The median number of procedures performed between 2019 and 2022 by the 8 hospitals that reached the learning curve threshold was 248, with a minimum of 109 and a maximum of 353.

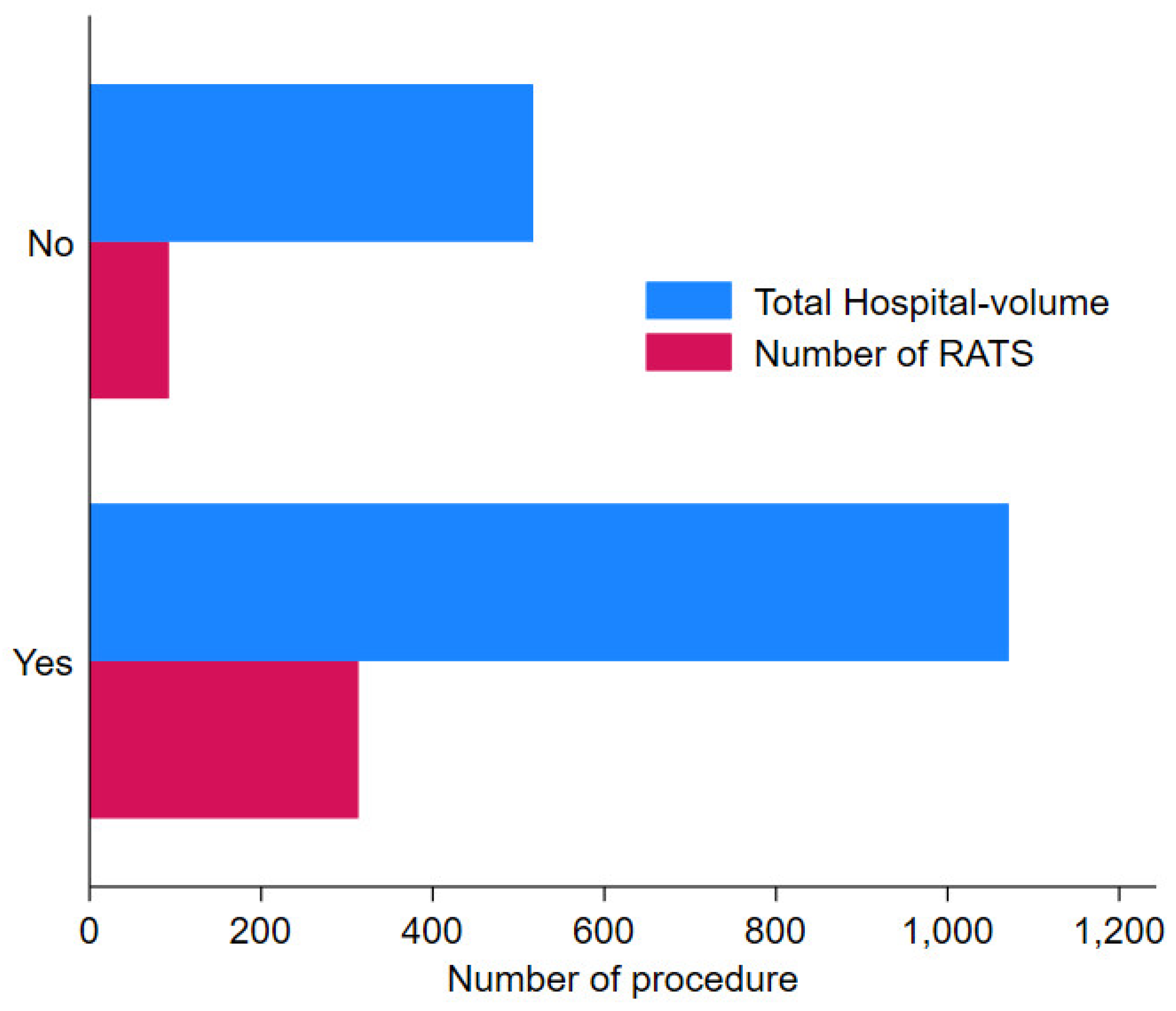

Figure 2 shows that hospitals that have reached their learning curve have a median hospital-volume for all types of lung resection for LC (thoracotomy, VATS and RATS) of 1031, compared with 516 for hospitals that have not reached the learning curve threshold. Among the 8 hospitals, 4 were academic hospitals, 1 a non-academic hospital, 1 private no-profit and 2 private for-profit.

Operative details and postoperative outcomes of both groups are shown in

Table 3.

Teams from the 8 hospitals that reached the learning curve threshold operated on a total of 1,870 RA procedures for LC vs. 1,489 for the 20 hospital teams that did not reach the learning curve threshold (

Table 3). The rate of haemorrhage complications was 4.6% in the group that did not reach the learning curve vs. 3.1% in the

“over threshold learning curve

” group (p=0.02) (

Table 3). Postoperative pleural effusions occurred in 16.1% of patients in a hospital that did not reach the learning curve versus 13.1% in a

“over threshold learning curve

” hospital (p=0.016) (

Table 3). Severe complications such as ARDS, respiratory failure, heart failure, acute ischemia of the lower limbs and pulmonary embolism were significantly more frequent in the group of hospitals that did not reach the learning curve threshold (

Table 3). Postoperative mortality was 1.3% in the group that did not reach the learning curve vs. 1.1% in the dans le group «over threshold learning curve » group (p=0.685) (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This work shows that a team performing RA procedures for LC should have performed at least 110 procedures with range from 94 to 174, in order to guarantee patients an acceptable complication rate. Most studies that examine the learning curve use different judgment criteria, such as operative duration, conversion to thoracotomy or intraoperative accidents [

17,

18,

19,

20]. These criteria are obviously necessary, but may not be sufficient to demonstrate that the technology is safe and provides patients a high level of quality of care. We may also wonder about the relevance of operating time in assessing quality of care. Does a surgeon who has a longer operating time actually penalize his patient? [

18,

19,

20].

Teams that have reached the learning curve threshold are high-volume hospitals. It is possible that our work evaluates not only the learning curve but also the performance of the centers, which is usually better in teams with a high volume of activity [

21]. The number of RA procedure for LC increased steadily from 2019 to 2022. We have found that the RA surgery program is carried out by high-volume hospitals. This seems to confirm the results we obtained before showing a great variability from one region to another in the spread of these minimally invasive technologies [

22]. Depending on their place of residence, some patients may not have access to these innovative technologies, due to the dispersal of technical platforms and low volume of activity, preventing them from mastering these minimally invasive technologies [

22].

Postoperative haemorrhagic complications and pleural effusions decreased in teams with more experience of RA procedures, which seems consistent with Zhang et al. [

23] who reported lower complication rates than in our study, which could be explained by the fact that teams involved in this study were high-volume centers. On the other hand, the significant reduction in major complications such as ARDS, heart failure or acute ischemia of the lower limbs may be surprising. We can imagine that the lack of mastery of the technology may have consequences for the post-operative course and a major impact on patients. Finally, few papers reported a high rate of severe postoperative complications. To our knowledge there are only two papers that reported these complications with lower rates than in our work [

23,

24]. The higher frequency of major postoperative complications in our work can be explained by a longer procedure or serious intraoperative accidents such as vessel injury leading to major haemorrhage.

On the other hand, the 30-day mortality rate decreased with time, reaching less than 1% at the end of the period. This is undeniably a significant advance thanks to these minimally invasive technologies [

21].

Prolonged length of stay did not decrease in teams that have validated their learning curve. In the literature, lower rates are reported [

17,

18,

20,

23,

24]. However, comparisons with other countries are difficult, as organizations and funding differ. The main issue in France relies in the organization of patient pathways and more particularly the preparation for hospital discharge, in collaboration with out-of-hospital care.

Limitations. Our study has the usual limitations of the absence of variables such as TNM stage, FEV1, etc.... This is the criticism usually levelled at medico-administrative studies. However, the criticism could be modulated with regards to recent results comparing the performances of the predictive models developed from medico-administrative data and a clinical database [

25]. The other limitation concerns 30-day mortality, which would no longer be considered a relevant indicator and that 90-day mortality would be preferable. However, we are not completely certain that 90-day mortality reflects only the quality of surgery, as other factors may intervene during the 90-day period to cause death, such as adjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy or progression of cancer. The literature on this subject does not seem to reach a final conclusion as we have no information on missing data and the performance of the model is not high [

26]. Further studies are thus needed to validate 90-day mortality as an indicator of surgical quality. Another limitation of this work concerns intraoperative variables such as length of stay or conversion, which cannot be collected in a database such as the PMSI. Finally, with this medico-administrative database, we are only evaluating the practice of a hospital’s surgical team, but we do not have information on the surgeon’s own practice.

Perceptive. The same type of data used in this study could be provided in the form of a dashboard to surgical teams starting a robotic surgery program. This would enable them to check their learning curve and, if necessary, implement improvement actions.

5. Conclusions

The threshold of 25 procedures does not seem sufficient to validate the Robot-Assisted surgery learning curve in LC surgery. To significantly reduce postoperative complications, a team would need to perform between 94 and 174 procedures to guarantee patient safety.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1. Logistic model regression for Clavien-Dindo > II to estimate predicted risk of failure (clavien-dindo classification > II) in patients operated by Robot-Assisted Thoracic Surgery;.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, PBP, AB and CQ; methodology, AB and CQ; software, JC and AB; validation, PBP, JC, AB and CQ; formal analysis, JC and AB.; writing—original draft preparation, PBP and AB; writing—review and editing, PBP, JC, LM, FD, HAH, AB and CQ; supervision, AB and CQ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by the Fondation ARC pour la recherche sur le cancer www.fondation-arc.org.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the National Committee for data protection: declaration of conformity to the methodology of reference 05 obtained on 7/08/2018 under the number 2204633 v0.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was not required, and patient-identifying information was not used in the research as this national retrospective study was based on pseudonymised data. In fact, the French national administrative hospital database does not contain any patient-identifying data. The patient’s identity is pseudonymised, making it possible to link data from the same patient without knowing his or her identity.

Data Availability Statement

The use of the data from the French hospital database by our department was approved by the National Committee for data protection. We are not allowed to transmit these data. PMSI data are available for researchers who meet the criteria for access to these French confidential data (this access is submitted to the approval of the National Committee for data protection) from the national agency for the management of hospitalization (ATIH - Agence technique de l’information sur l’hospitalisation).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Suzanne Rankin for reviewing the English and Gwenaëlle Periard for her help with the layout and management of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remon, J.; Soria, J.C.; Peters, S.; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Early and locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: An update of the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines focusing on diagnosis, staging, systemic and local therapy. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1637–1642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rocco, G.; Internullo, E.; Cassivi, S.D.; Van Raemdonck, D.; Ferguson, M.K. The variability of practice in minimally invasive thoracic surgery for pulmonary resections. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2008, 18, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vansteenkiste, J.; Crinò, L.; Dooms, C.; Douillard, J.Y.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Lim, E.; Rocco, G.; Senan, S.; van Schil, P.; Veronesi, G.; et al. 2nd ESMO Consensus Conference on Lung Cancer: Early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer consensus on diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014, 25, 1462–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson-Smith, A.R.; Anning, N.; Muston, B.; et al. learning curve of the robotic-assisted lobectomy —a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2023, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, N.A.; Hashimoto, D.A.; Porteous, A.J.; et al. Systematic review of learning curves in robot-assisted surgery. BJS Open 2020, 4, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, A.D.; D’Souza, D.M.; Mofatt Bruce, S.D.; Merritt, R.E.; Kneuertz, P.J. DefIning the learning curve of robotic thoracic surgery: what does it take? Surgical Endoscopy 2019. [CrossRef]

- Seely, A.J.E.; Ivanovic, J.; Threader, J.; et al. Systematic Classification of Morbidity and Mortality After Thoracic Surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2010, 90, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. Available online: http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en (accessed on 1 March 2016).

- Iezzoni, L.I. Assessing quality using administrative data. Ann. Intern. Med. 1997, 127 Pt 2, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, W.D.; Brambilla, E.; Müller-Hermelink, H.K.; Harris, C.C. Pathology and Genetics: Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart; IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Charlson, M.; Szatrowski, T.P.; Peterson, J.; Gold, J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1994, 47, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyerberg, E.W. Clinical Prediction Models: A Practical Approach to Development, Validation and Updating; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Caputo, M.; et al. Control chart methods for monitoring cardiac surgical performance and their interpretation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004, 128, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, A.; George, A.; Mehta, S. CRS and HIPEC for PMP-Use of the LC-CUSUM to determine the number of procedures required to attain a minimal level of proficiency in delivering the combined modality treatment. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 8, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, S.H.; Jones, M. Risk-adjusted survival time monitoring with an updating exponentially weighted moving average (EWMA) control chart. Stat. Med. 2010, 29, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; Sun, X.; Miao, S.; Li, S.; et al. Learning curve for robot-assisted lobectomy of lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 2019, 11, 2431–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldonado, J.J.A.; Amaral, M.; Garrett, J.; et al. Credentialing for robotic lobectomy: what is the learning curve? A retrospective analysis of 272 consecutive cases by a single surgeon. Journal of Robotic Surgery 2019, 13, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gaca, C.; Gonde’ b, H.; Gillibert, A.; et al. Medico-economic impact of robot-assisted lung segmentectomy: what is the cost of the learning curve ? Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery 2020, 30, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.Z.; Ren-Chun Lai Abbas, A.E.; et al. learning curve of robotic portal lobectomy for pulmonary neoplasms: A prospective observational study. Thorac Cancer. 2021, 12, 1431–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Cottenet, J.; Pagès, P.B.; Quantin, C. Mortality and failure-to-rescue major complication trends after lung cancer surgery between 2005 and 2020: a nationwide population-based study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e075463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Cottenet, J.; Pages, P.B.; Quantin, C. Diffusion of Minimally Invasive Approach for Lung Cancer Surgery in France: A Nationwide, Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. Cancers 2023, 15, 3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Han, Y.; et al. Robotic Anatomical Segmentectomy: An Analysis of the Learning Curve. Ann Thorac Surg 2019, 107, 1515–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim, C.; Hanna, W.; Waddell, T.; et al. Robotic-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for lung resection: the first Canadian series. J can chir. 2017, 60, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, A.; Cottenet, J.; Quantin, C. Is the Validity of Logistic Regression Models Developed with a National Hospital Database Inferior to Models Developed from Clinical Databases to Analyze Surgical Lung Cancers? Cancers 2024, 16, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etienne, H.; Pagès, P.B.; Iquille, J.; et al. Impact of surgical approach on 90-day mortality after lung resection for non-small cell lung cancer in high-risk operable patients. ERJ Open Res 2024, 10, 00653–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).