Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review on Financial Literacy, Trust and Retirement

| Authors | Research scope | Research methodology | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bielawska, Turner (2023) [12] | Trust and auto—enrolment in pensions. | A survey of 400 employees was conducted in April/May 2021. Compassion UK and Poland. | Auto—enrolment in pensions in the UK is successful due to inertia, but in Poland, workers distrust future pension benefits, leading to a high opt-out rate. |

| Clark, Pelletier (2022) [32] | Automatic enrollment, age, sex, and income. |

The research participants are South Dakota state and local government employees, including teachers. The authors use regression analysis. |

Authors find that automatic enrollment changes differences in the participation rate by age, sex, and income. We also find that prior to the adoption of auto-enrollment, agencies that ultimately chose to implement this policy had higher participation rates compared to those that did not adopt auto -enrolment. |

| Fisch, Seligman (2021) [16] | Financial literacy, trust and financial market participation. | Data collection and survey development were conducted over three distinct field research periods. 1. In late 2017—an independent financial literacy survey was developed and fielded. 2. spring 2018—selected financial literacy questions integrated with many questions targeting trust. (550 observations). The authors engaged in an analysis estimation to decide on a stopping point for field research. 3. The authors entered data collection (collected 312 observations. Sample sizes -over 700. |

Trust and financial literacy both strongly influence financial market participation, but trust has a more uniform relationship with increased participation, while financial literacy has a u-shaped relationship with reduced participation and increased participation. Trust in financial institutions increases the propensity to save and invest, which is crucial for accumulating capital for retirement. |

| Koh, Mitchell, Fong, (2019) [27] | Pensions savings, trust in financial and public-sector | The study draws on the Singapore Life Panel (SLP®), a high-frequency internet survey of people aged 50-70, to assess how trust ties to older respondents’ pension plan participation and others | Trust in financial and public-sector representatives is positively associated with pension savings, investments, and insurance purchases, while trust in people is uncorrelated with retirement preparedness behaviors. |

| Ricci and Caratelli (2015) [33] | The study is about the complex relationship between financial literacy, retirement planning, and trust in financial institutions. | The authors use data from the 2010 Bank of Italy Household Income and Wealth Survey. The impact of financial literacy on retirement planning is a well-established issue in the existing empirical literature. | Financial literacy positively impacts retirement planning and private pension decisions, while trust in financial institutions positively influences both entry into private pension schemes and devoting severance pay to private pension schemes. |

| Agnew, Szykman, Utkus, (2012) [14] | Financial knowledge, trust in financial institution, auto-enrolment, | The author assesses the relationship between the employee auto-enrolment participation decision using several probit regressions relating an employee’s plan participation decision to various demographic measures and our trust and plan knowledge indicators | Knowledge and trust in financial institutions strongly correlate to pension savings behavior based on auto-enrolment. In supplementary pension plans, knowledge and demographic characteristics are related to participation in auto-enrolment plans. In automatic enrollment settings, trust in financial institutions and knowledge of an available plan match are related to participation. Although this study cannot prove causality of the relationships, it does extend our understanding of the complex factors underlying savings choices. Policy implications are discussed. |

3. Research Framework and Hypotheses

3.2. Employee Capital Plans (PPK) in Pension Schemes

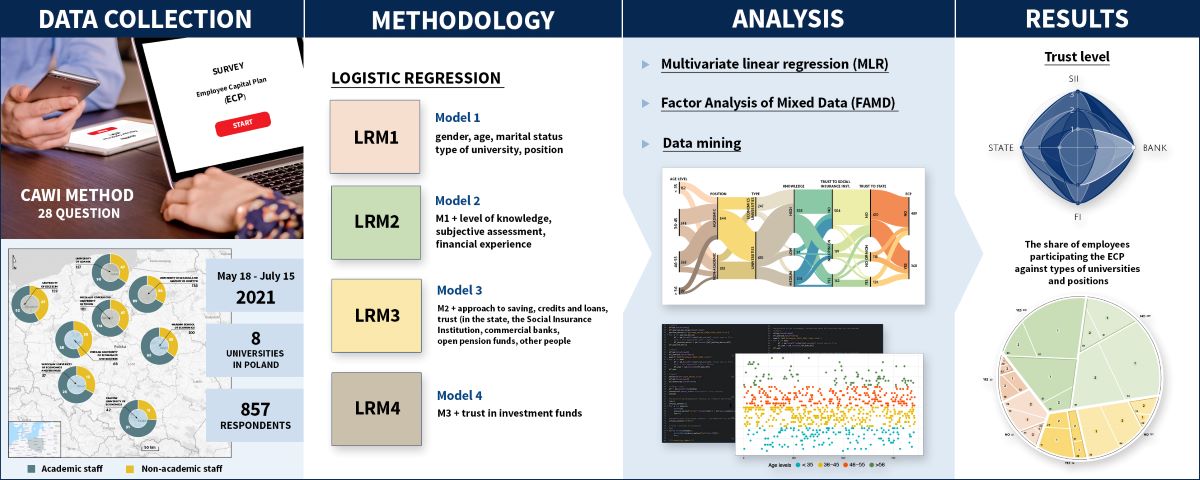

4. Data and Research Methods

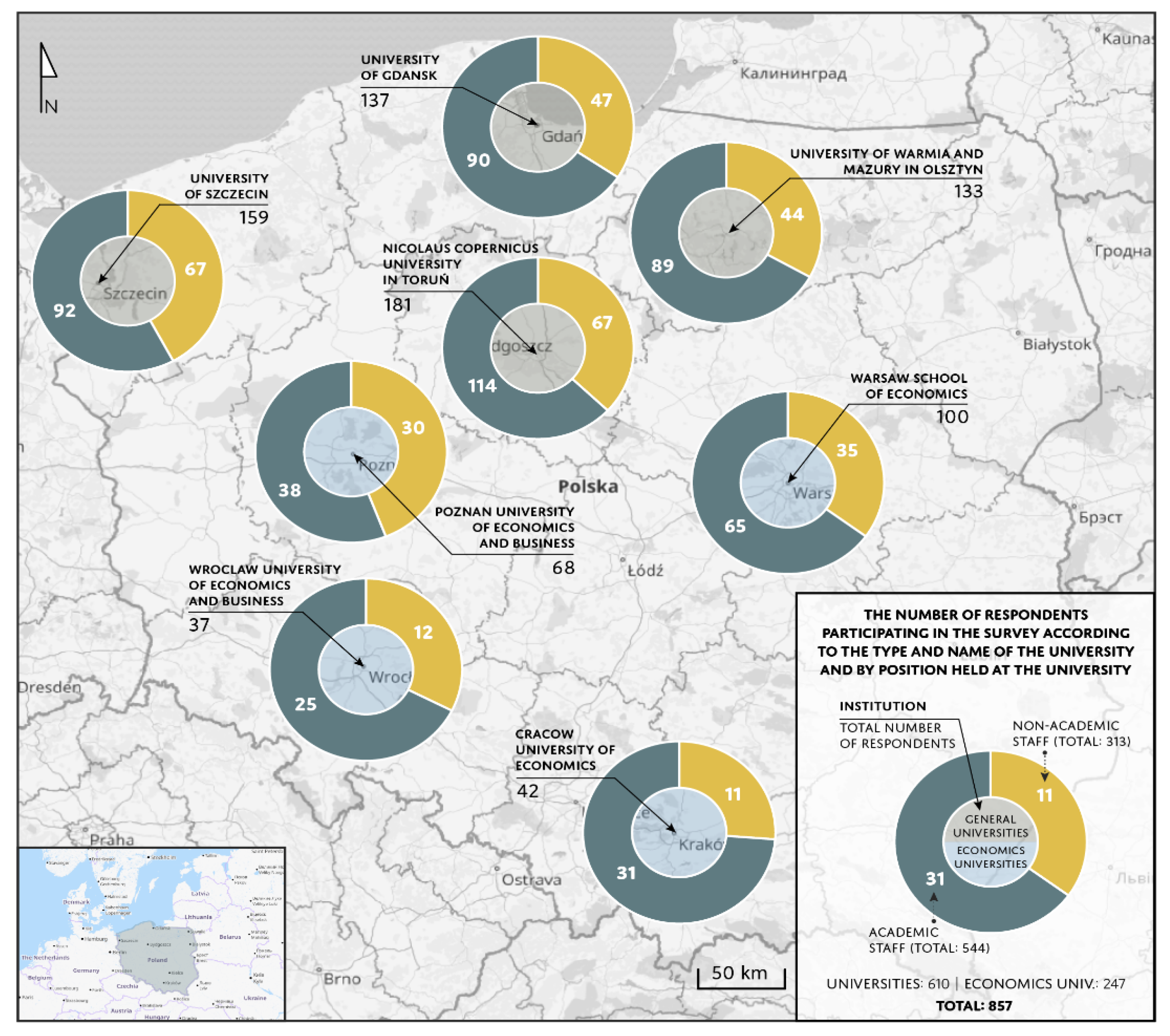

4.2. Data Collection

4.2. Methodology

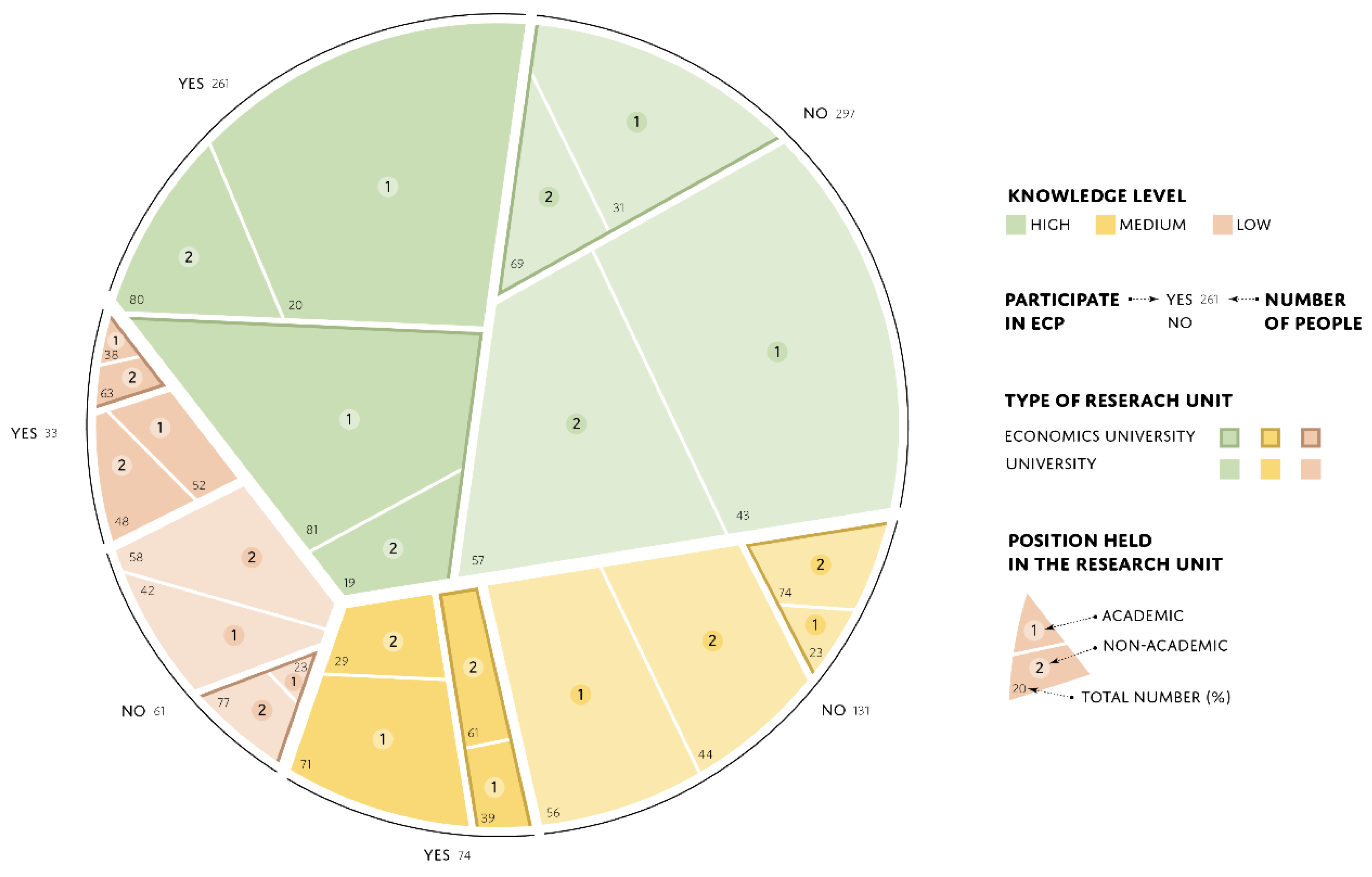

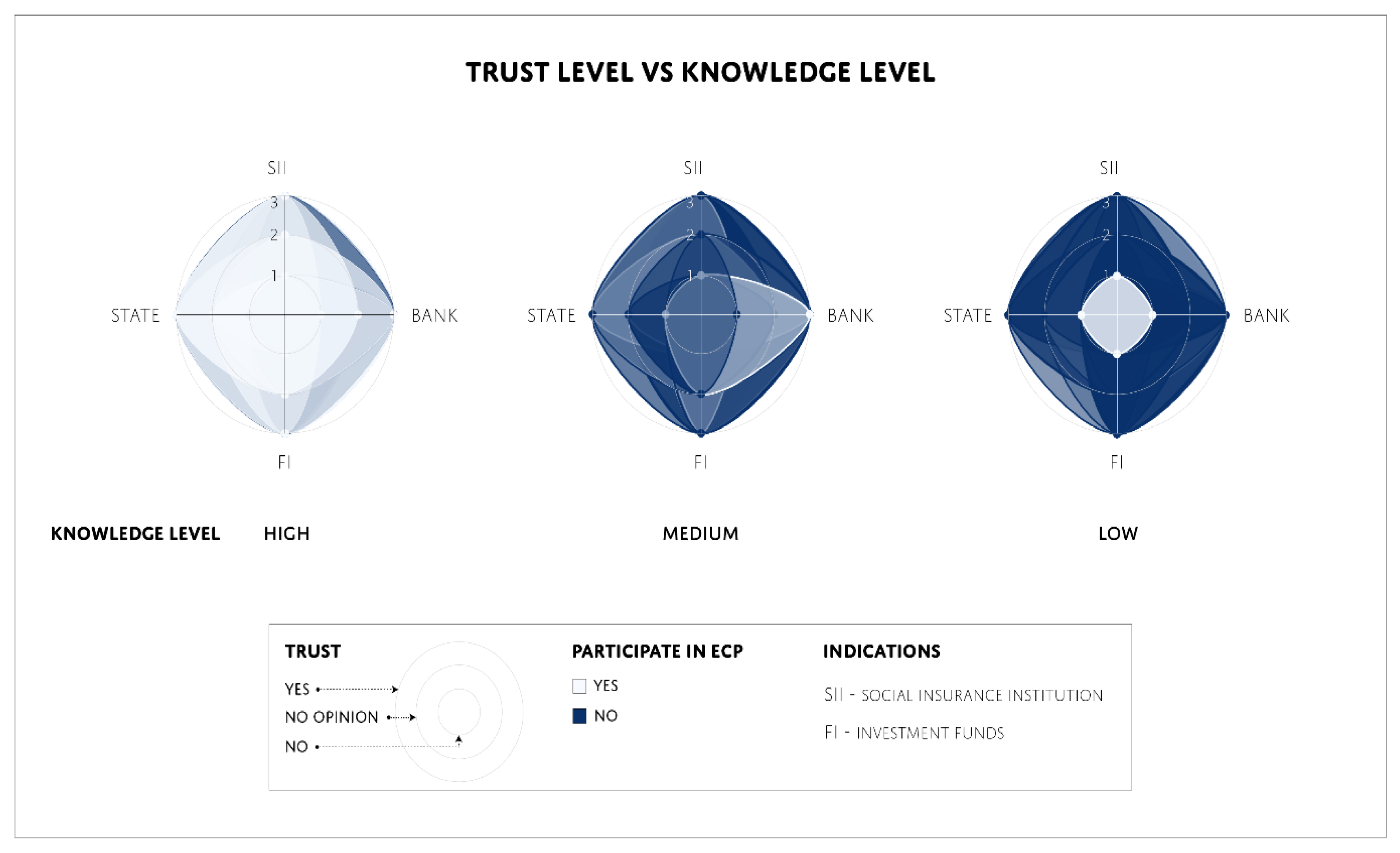

5. Results

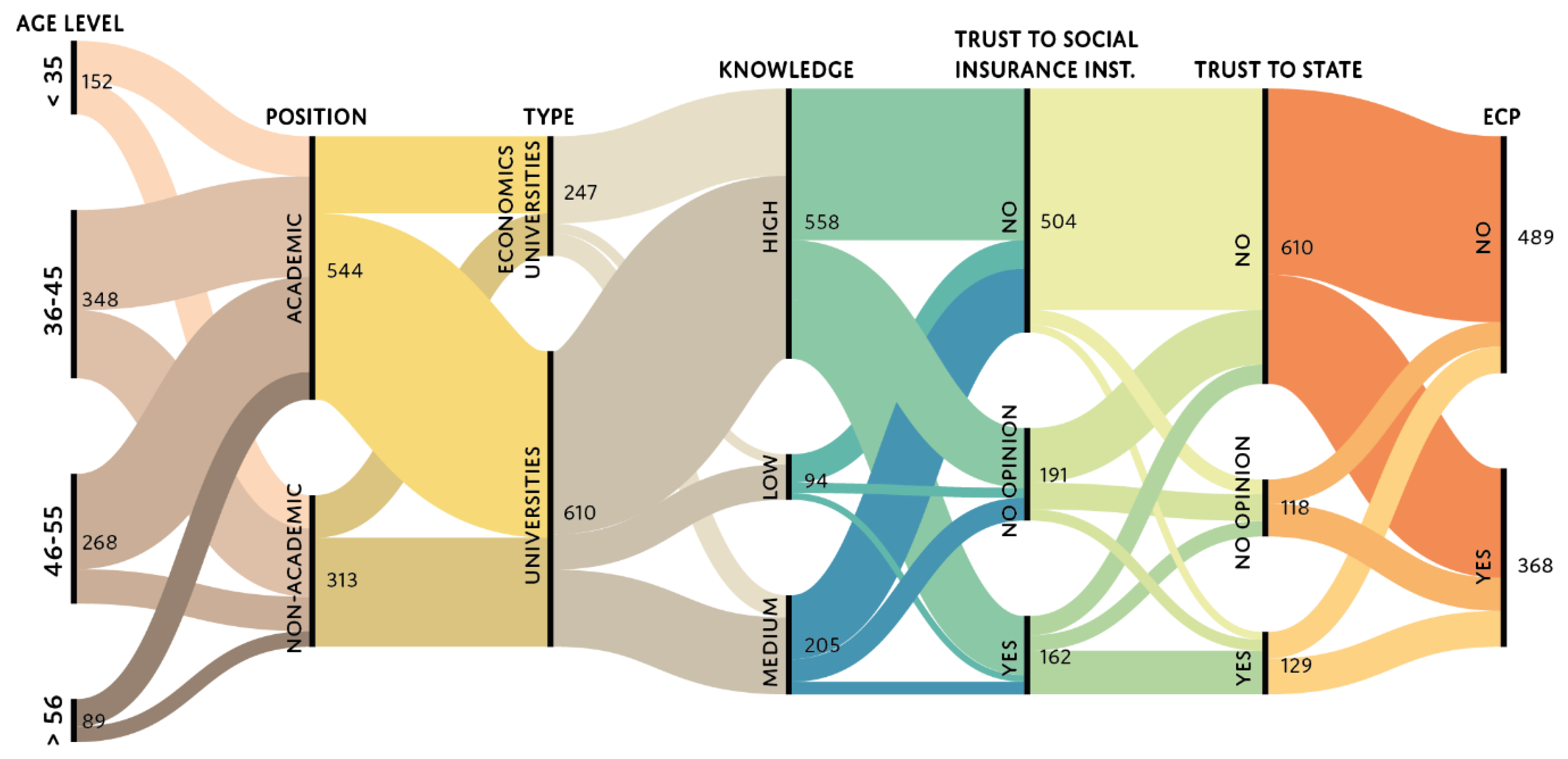

5.1. General Descriptive Results

5.2. Regression Analysis

| Variables | LRM1 | LRM2 | LRM3 | LRM4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (ref. woman) Age (ref. < 35 years old) 36–45 years old 46–55 years old 55 years old or older Type of research unit (ref. general university) Position at the research unit (ref. academic staff) Level of knowledge My own knowledge and financial experience Trust in the state (ref. no) I have no opinion / neither yes nor no Yes Trust in commercial banks (ref. no) I have no opinion / neither yes nor no Yes Trust in open pension funds (ref. no) I have no opinion / neither yes nor no Yes Trust in investment funds (ref. no) I have no opinion / neither yes nor no Yes Constant Cox–Snell’s R-squared Nagelkerke’s R-squared Hosmer-Lemeshow (p-value) Log likelihood Observations Gender (ref. woman) Age (ref. < 35 years old) 36–45 years old 46–55 years old 55 years old or older Type of research unit (ref. general university) Position at the research unit (ref. academic staff) Level of knowledge My own knowledge and financial experience Trust in the state (ref. no) I have no opinion / neither yes nor no Yes Trust in commercial banks (ref. no) I have no opinion / neither yes nor no Yes Trust in open pension funds (ref. no) I have no opinion / neither yes nor no Yes Trust in investment funds (ref. no) I have no opinion / neither yes nor no Yes Constant Cox–Snell’s R-squared Nagelkerke’s R-squared Hosmer-Lemeshow (p-value) Log likelihood Observations Gender (ref. woman) Age (ref. < 35 years old) 36–45 years old 46–55 years old 55 years old or older Type of research unit (ref. general university) Position at the research unit (ref. academic staff) Level of knowledge My own knowledge and financial experience Trust in the state (ref. no) I have no opinion / neither yes nor no Yes Trust in commercial banks (ref. no) I have no opinion / neither yes nor no Yes Trust in open pension funds (ref. no) I have no opinion / neither yes nor no Yes Trust in investment funds (ref. no) I have no opinion / neither yes nor no Yes Constant Cox–Snell’s R-squared Nagelkerke’s R-squared Hosmer-Lemeshow (p-value) Log likelihood Observations |

- - - - - 2.180*** .445*** .793* .062 .083 .972 1,116.374 857 |

1.433* - - - - 2.256*** .456*** 1.283* .625*** 1.909* .139 .187 .977 1,042.303 857 |

1.408* * .620* .905 .501* 2.325*** .463*** 1.257* .637*** *** 1.992** 2.214*** - - - ** 1.749** 1.293 1.605 .178 .239 .157 1,002.585 857 |

1.504* * .646* .922 .502* 2.479*** .425*** - .654*** *** 2.075*** 2.327** * .553** .652 ** 1.829** 1.143 ** 1.578* 2.061** 2.433** .189 .253 .784 991.743 857 |

| - - - - - 2.180*** .445*** .793* .062 .083 .972 1,116.374 857 |

1.433* - - - - 2.256*** .456*** 1.283* .625*** 1.909* .139 .187 .977 1,042.303 857 |

1.408* * .620* .905 .501* 2.325*** .463*** 1.257* .637*** *** 1.992** 2.214*** - - - ** 1.749** 1.293 1.605 .178 .239 .157 1,002.585 857 |

1.504* * .646* .922 .502* 2.479*** .425*** - .654*** *** 2.075*** 2.327** * .553** .652 ** 1.829** 1.143 ** 1.578* 2.061** 2.433** .189 .253 .784 991.743 857 |

|

| - - - - - 2.180*** .445*** .793* .062 .083 .972 1,116.374 857 |

1.433* - - - - 2.256*** .456*** 1.283* .625*** 1.909* .139 .187 .977 1,042.303 857 |

1.408* * .620* .905 .501* 2.325*** .463*** 1.257* .637*** *** 1.992** 2.214*** - - - ** 1.749** 1.293 1.605 .178 .239 .157 1,002.585 857 |

1.504* * .646* .922 .502* 2.479*** .425*** - .654*** *** 2.075*** 2.327** * .553** .652 ** 1.829** 1.143 ** 1.578* 2.061** 2.433** .189 .253 .784 991.743 857 |

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Link to the data

References

- Safari, K.; Njoka, C. Munkwa, M. G. Financial literacy and personal retirement planning: a socioeconomic approach, Journal of Business and Socio-economic Development 2021, 1, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meir, A.; Mugerman, Y.; Sade, O. Financial literacy and retirement planning. Evidence from Israel, Israel Economic Review, Bank of Israel 2016, 14, 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, J.S.; Madrian, B.C.; Skimmyhorn, W.L. Financial literacy, financial education, and economic outcomes. Annual Review of Economics 2013, 5, 347–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, T.; Lusardi, A.; Menkhoff, L.; Urban, C. Financial education affects financial knowledge and downstream behaviors. Journal of Financial Economics 2022, 145, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A.; Michaud, P.C.; Mitchell, O.S. Optimal financial knowledge and wealth inequality. Journal of Political Economy 2017, 125, 431–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O.S. Financial literacy around the world: An overview. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 2011, 10, 479–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O.S. The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature 2014, 52, 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.; Graf, R. Financial Literacy and Retirement Planning in Switzerland. Numeracy 2013, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialowolski, P.; Cwynar, A.; Xiao, J.J.; Weziak-Bialowolska, D. Consumer financial literacy and the efficiency of mortgage-related decisions: New evidence from the Panel Study of Income dynamics. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2022, 46, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, J.J.; Zhang, W. Financial Literacy, Portfolio Choice and Financial Well-Being. Social Indicators Research 2017, 132, 799–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dalen, H.P.; Henkens, K. Trust and distrust in pension providers in times of decline and reform. Analysis of survey data 2004–2021. De Economist 2022, 170, 401–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielawska, K.; Turner, J. Trust and the behavioral economics of automatic enrolment in pensions: a comparison of the UK and Poland. Journal of Economic Policy Reform 2023, 26, 216–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Pensions at a Glance 2023: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, 2023, Paris, 1-236. [CrossRef]

- Agnew, J.R.; Szykman, L.R.; Utkus, S.P.; Young, J.A. Trust, plan knowledge and 401(k) savings behavior. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 2012, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgarakos, D.; Inderst, R. Financial Advice and Stock Market Participation, 2014 CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP9922. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2444945.

- Fisch, J.E.; Seligman, J.S. Trust, financial literacy, and financial market participation. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 2022, 21, 634–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC. The 2018 Pension Adequacy Report: current and future income adequacy in old age in the EU. 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/economy-finance/2018-ageing-report-underlying-assumptions-and-projection-.

- Vickerstaff, S.; Macvarish, J.; Taylor-Gooby, P.; Loretto, W.; Harrison, T. Trust and confidence in pensions: A literature review. Working Paper 2012, 108, Department for Work and Pensions, 1-55. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7cbaf5ed915d63cc65c81d/WP108.pdf.

- Alessie, R.; Van Rooij, M.; Lusardi, A. Financial literacy and retirement preparation in the Netherlands. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 2011, 10, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmi, P.; Ruuskanen, O.P. Financial literacy and retirement planning in Finland. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 2019, 17, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prast, H.; Van Soest, A. Financial literacy and preparation for retirement. Intereconomics 2016, 51, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornero, E.; Monticone, C. Financial literacy and pension plan participation in Italy. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 2011, 10, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, V.I.; Febrian, E.; Effendi, N.; Anwar, M.; Nidar, S.R. Financial Literacy and Its Variables: The Evidence from Indonesia. Economics and Sociology 2020, 13, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.Y. Social trust and economic development. Edward Elgar Publishing 2019, 16629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Cruijsen, C.; de Haan, J.; Roerink, R. Financial knowledge and trust in financial institutions. Journal of Consumer Affairs 2021, 55, 680–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, E.; Mare, D.S. Formal and Informal Household Savings: How Does Trust in Financial Institutions Influence the Choice of Saving Instruments? SSRN Electronic Journal 2017, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, B.S.K.; Mitchell, O.S.; Fong, J.H. Trust and retirement preparedness: Evidence from Singapore. Journal of the Economics of Ageing 2021, 18, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Hu, W. Determinants of public trust in government: empirical evidence from urban China. International Review of Administrative Sciences 2017, 83, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandro, M.; Cardinale Lagomarsino, B.; Scartascini, C.; Streb, J.; Torrealday, J. Transparency and trust in government evidence from a survey experiment. World Development 2021, 138, 105223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidoo, S.T.; Akoto, L. Does trust in financial institutions drive formal saving? Empirical evidence from Ghana. International Social Science Journal 2019, 69, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høyer, H.C.; Mønness, E. Trust in public institutions—spillover and bandwidth. Journal of Trust Research 2016, 6, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.; Pelletier, D. Impact of defaults on participation in state supplemental retirement savings plans. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 2022, 21, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, O.; Caratelli, M. Financial literacy, trust and retirement planning. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 2017, 16, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission. The 2021 Pension Adequacy Report: current and future income adequacy in old age in the European Union. Country profile, 2021, Volume II. Social Protection Committee, European Commission, Brussels. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=738&langId=en&pubId=8397&preview=cHJldkVtcGxQb3J0YWwhMjAxMjAyMTVwcmV2aWV3.

- Central Statistical Office. US Poland in numbers, Central Statistical Office, 2023. Warsaw. https://stat.gov.pl.

- PPK. Biuletyn Pracowniczych Planów Kapitałowych (Employee Capital Plans Bulletin), 2024. Available online: https://www.mojeppk.pl/aktualnosci/ponad-160-proc-zysku-dla-uczestnikow-ppk-032024.html.

- KNF Raport o stanie rynku emerytalnego w Polsce na koniec czerwca 2024 r.; Komisja Nadzoru Finansowego, Warszawa. (Report on the state of the pension market in Poland at the end of June 2024, Warsaw, Polish Financial Supervision Authority, Warsaw), 2024. Available online: https://www.knf.gov.pl/knf/pl/komponenty/img/Raport_o_stanie_rynku_emerytalnego_w_Polsce_na_koniec%202023_roku.pdf.

- OECD. OECD Pensions Outlook 2020. OECD Publishing, 2020, Paris, 1-210. [CrossRef]

- Beshears, J.; Choi, J.; Laibson, D.; Madrian, B.; Skimmyhorn, W. Borrowing to save? The impact of automatic enrollment on debt. Journal of Finance 2022, 77, 403–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. .; Oh, J..; Woo, S. An introduction of new time series forecasting model for oil cargo volume. Journal of Korea Port Economic Association 2018, 34, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Prediction model of regional economic development potential based on data mining technology. Engineering Reports 2023, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuswanto, H.; Asfihani, A.; Sarumaha, Y.; Ohwada, H. Logistic regression ensemble for predicting customer defection with very large sample size. Procedia Computer Science 2015, 72, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecka, A.; Kurdys-Kujawska, A.; Zawadzka, D. Application of logistic regression models to assess household financial decisions regarding debt. Procedia Computer Science 2020, 176, 3418–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qin, J. Analysis of financial product purchases based on logistic regression. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2021, 1848, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pages, J. Analyse factorielle de données mixtes. Revue de Statistique Appliquée 2004, 52, 93–111. Available online: http://www.numdam.org/article/RSA_2004__52_4_93_0.pdf.

- Bucher-Koenen, T.; Lusardi, A. Financial literacy and retirement planning in Germany. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 2011, 10, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.N.; Polách, J.; Vozňáková, I. The role of financial literacy in retirement investment choice. Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy 2019, 14, 569–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almenberg, J.; Säve-Söderbergh, J. Financial literacy and retirement planning in Sweden. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 2011, 10, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, D.; Feslier, D.; Hurnard, R. Financial literacy and retirement planning in New Zealand. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 2011, 10, 619–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, J. Plan design and participant behavior in defined contribution retirement plans: Past, present, and future. NBER Working Paper 2024, 32653, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ameriks, J.; Caplin, A.; Leahy, J. Wealth accumulation and the propensity to plan. In Quarterly Journal of Economics 2003, 118, 1007–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rooij, M.C.J.; Lusardi, A.; Alessie, R.J.M. Financial literacy and retirement planning in the Netherlands. Journal of Economic Psychology 2011, 32, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rooij, M.C.J.; Lusardi, A.; Alessie, R.J.M. Financial literacy, retirement planning and household wealth. Economic Journal 2012, 122, 449–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.; Urban, C. Does financial education affect retirement savings? The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 2023, 24, 100446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).