Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Current State of Knowledge Concerning the Utilization of Oyster Shells

2.1. Fine Aggregate in Concrete

2.2. Oyster Shell Characteristics and Chemical Composition

2.3. The Use of Waste Shells in Concrete

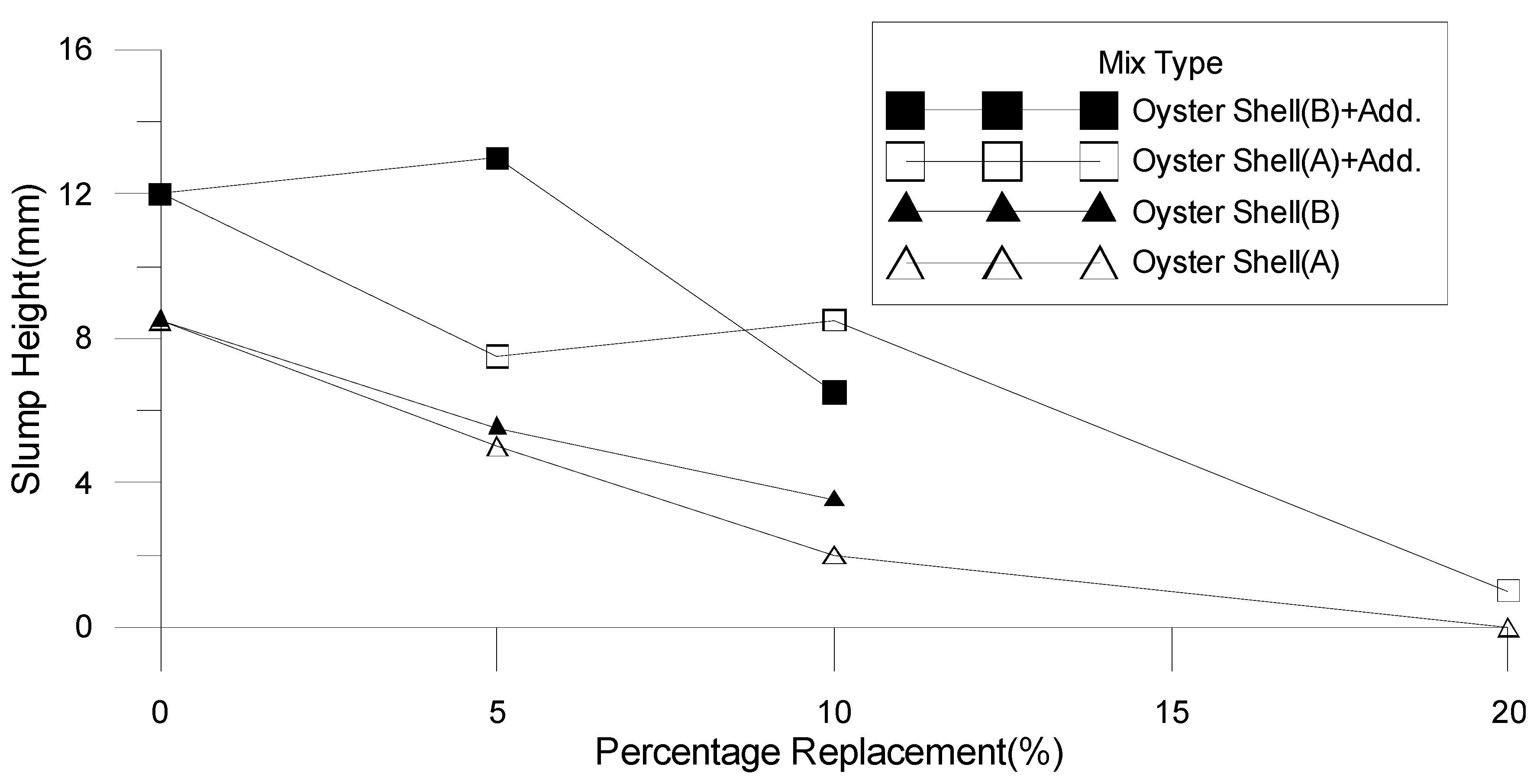

2.4. Impact of Shell Substitution on Concrete Workability

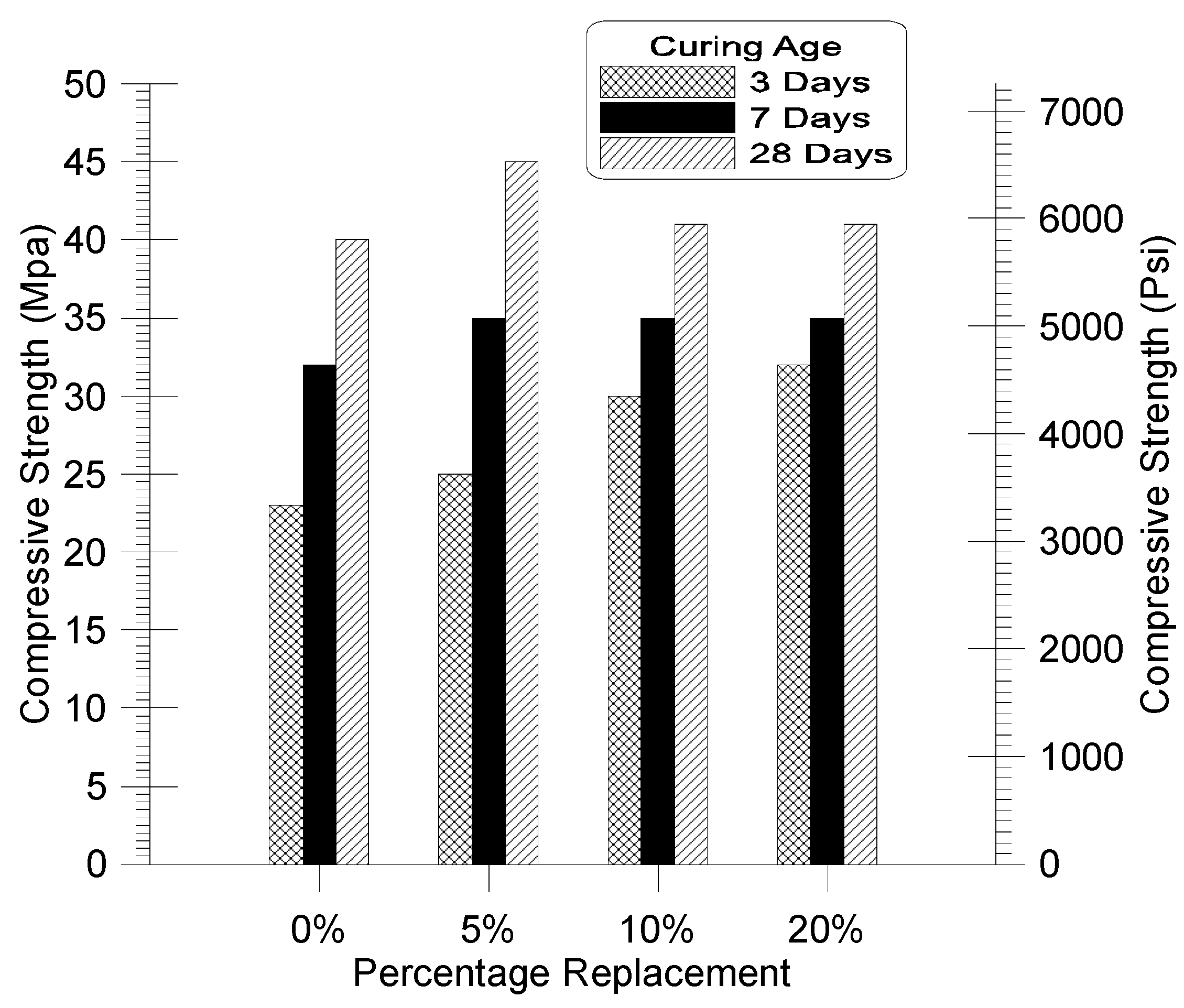

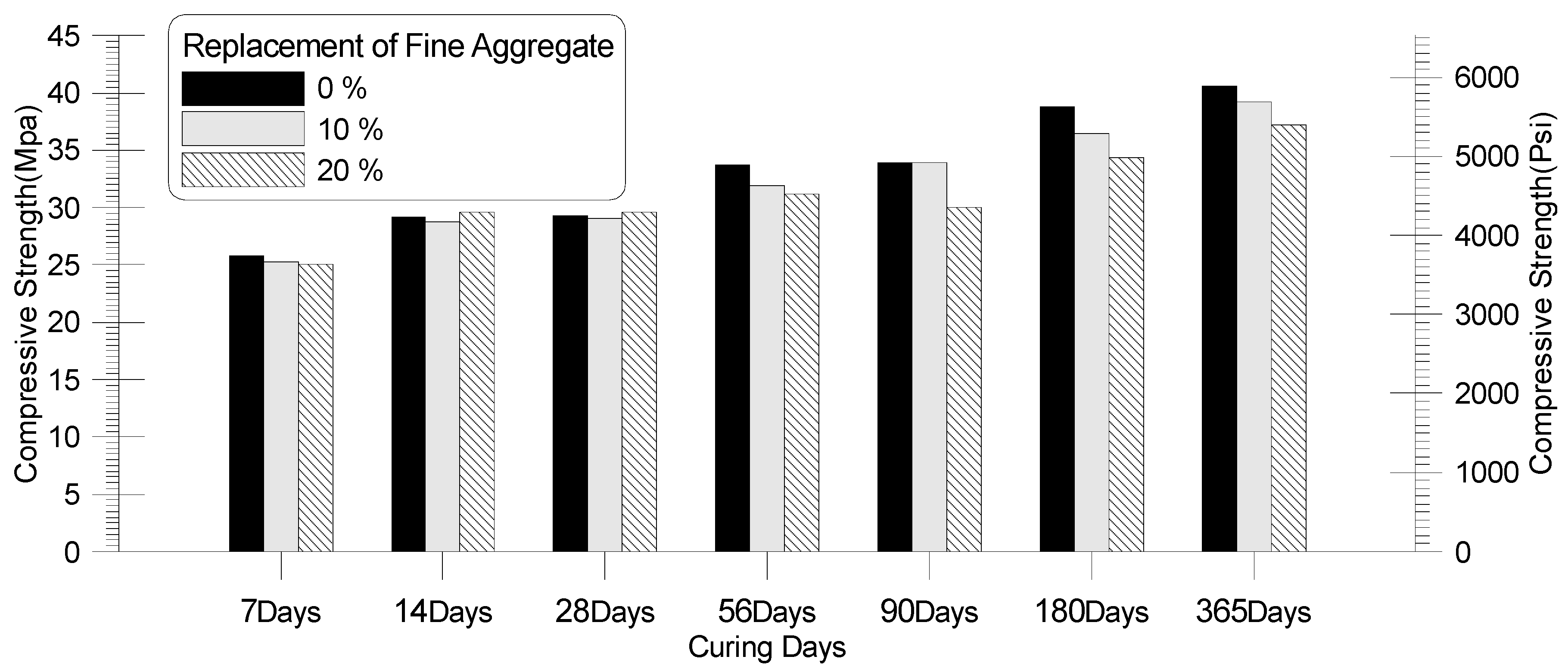

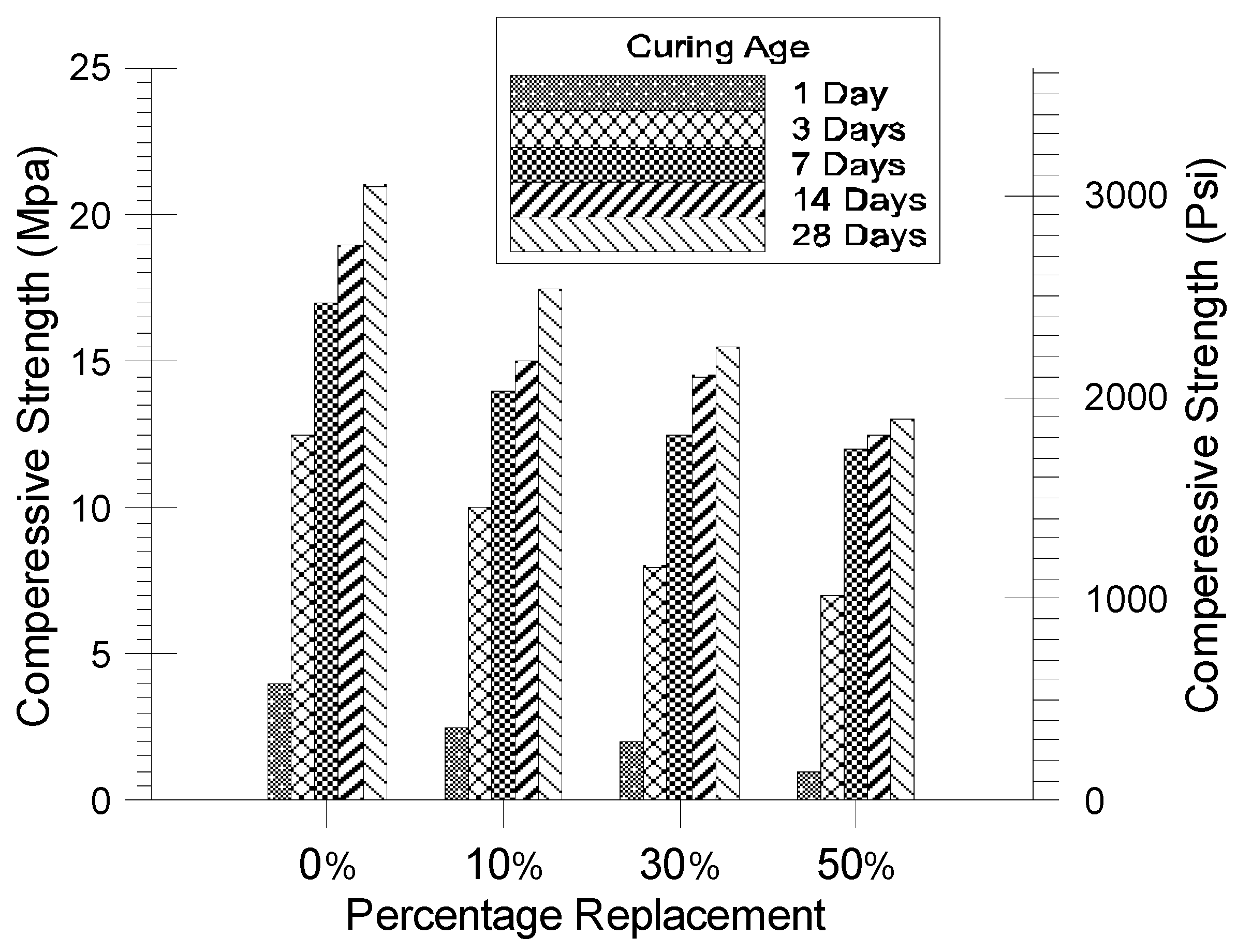

2.5. Impact of Oyster Shells on Concrete Strength

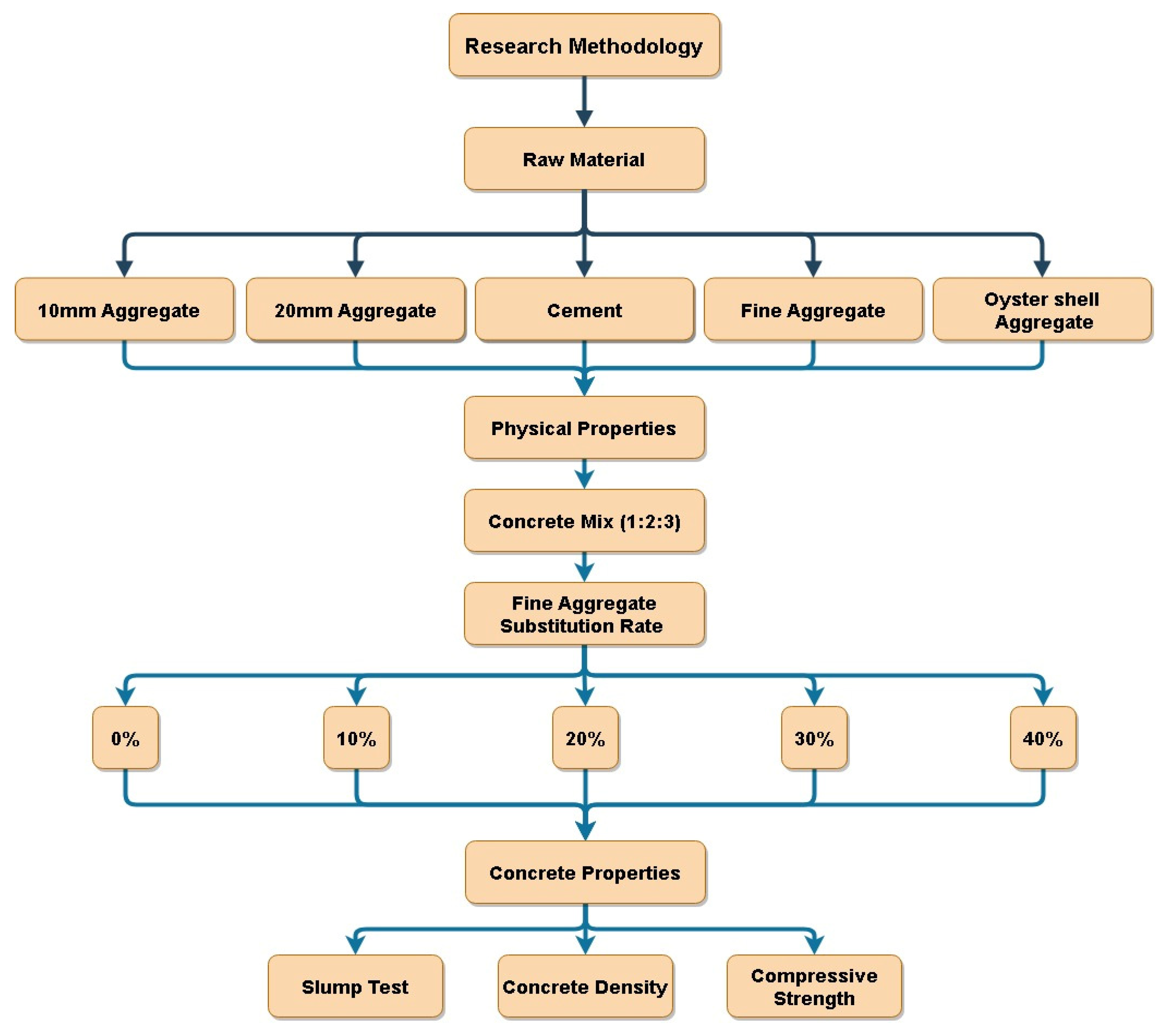

3. Research Methodology

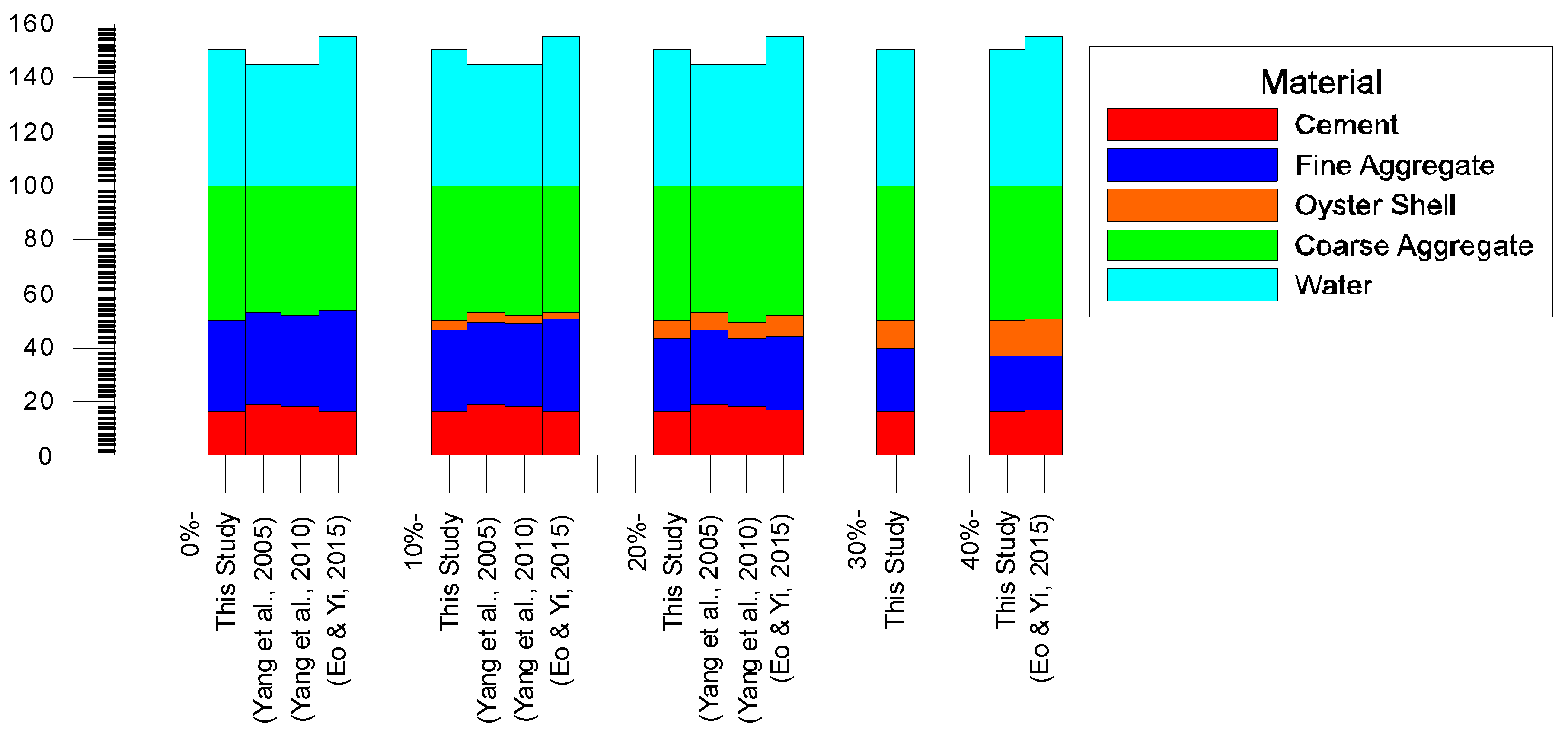

3.1. Mix Design and Sample Preparation

3.2. Material Experiment

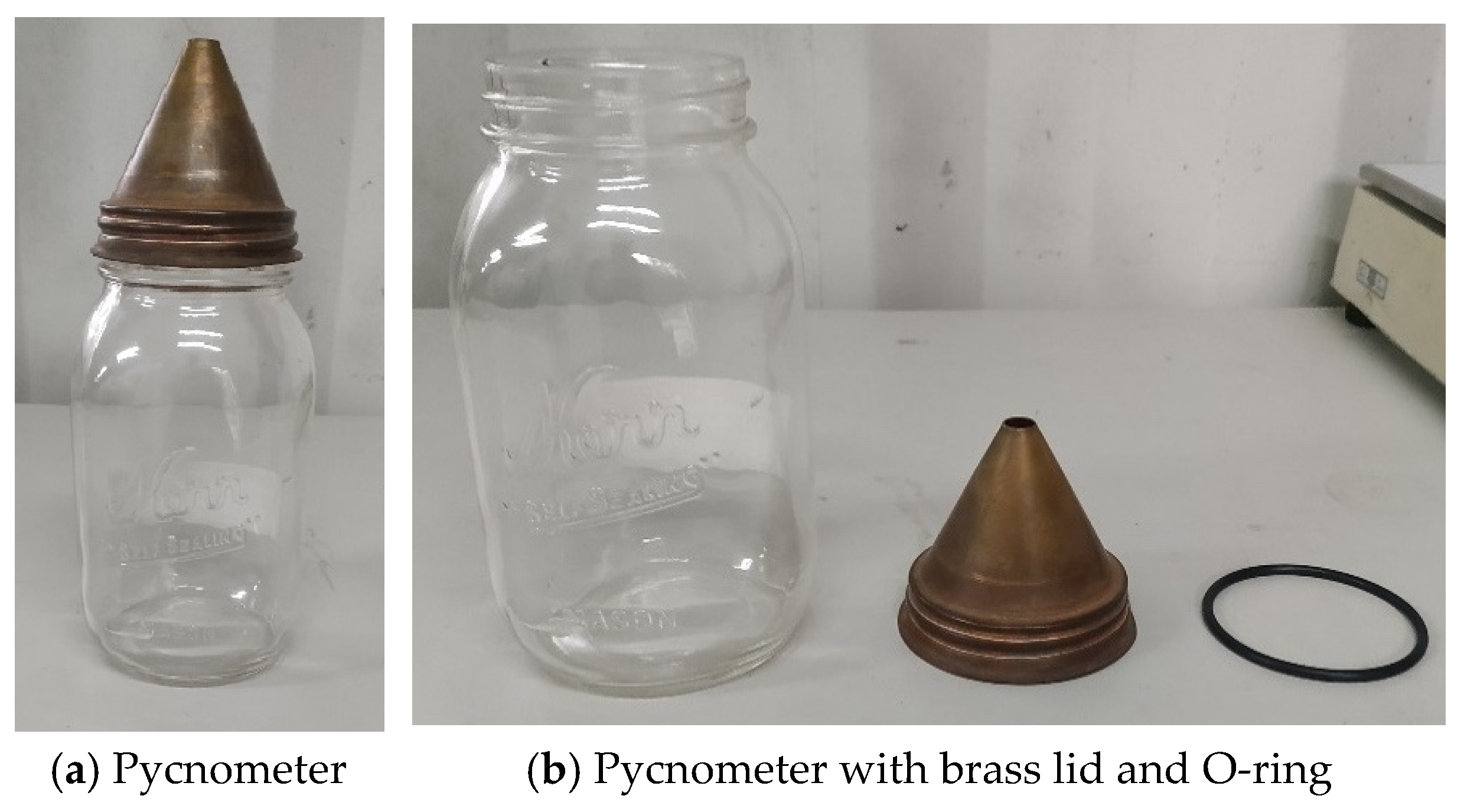

- (1)

- Specific Gravity

- 1)

- Before measurements, the sample was dried in an oven at a temperature of 105°C - 110°C for 24 hours.

- 2)

- The weight of the empty pycnometer was measured and recorded as A1.

- 3)

- The oven-dried sample was placed in the pycnometer, and the weight reading was noted as A2.

- 4)

- The pycnometer was then closed with a conical brass top, and distilled water was added through the hole until the pycnometer was filled. This weight was recorded as A3.

- 5)

- The weight of the pycnometer containing only water was measured and noted as A4.

- (2)

- Absorption of Aggregate

- (3)

- Sieve Analysis

- (4)

- Workability

- (5)

- Density of Concrete

- (6)

- Compressive Strength

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Material Properties

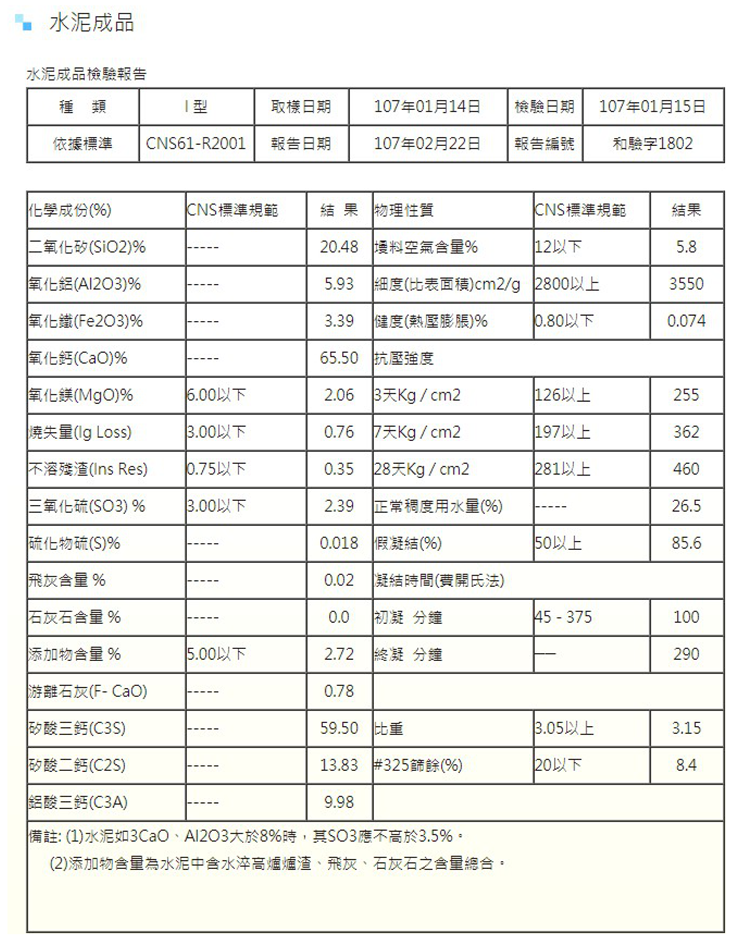

- (1)

- Cement

- (2)

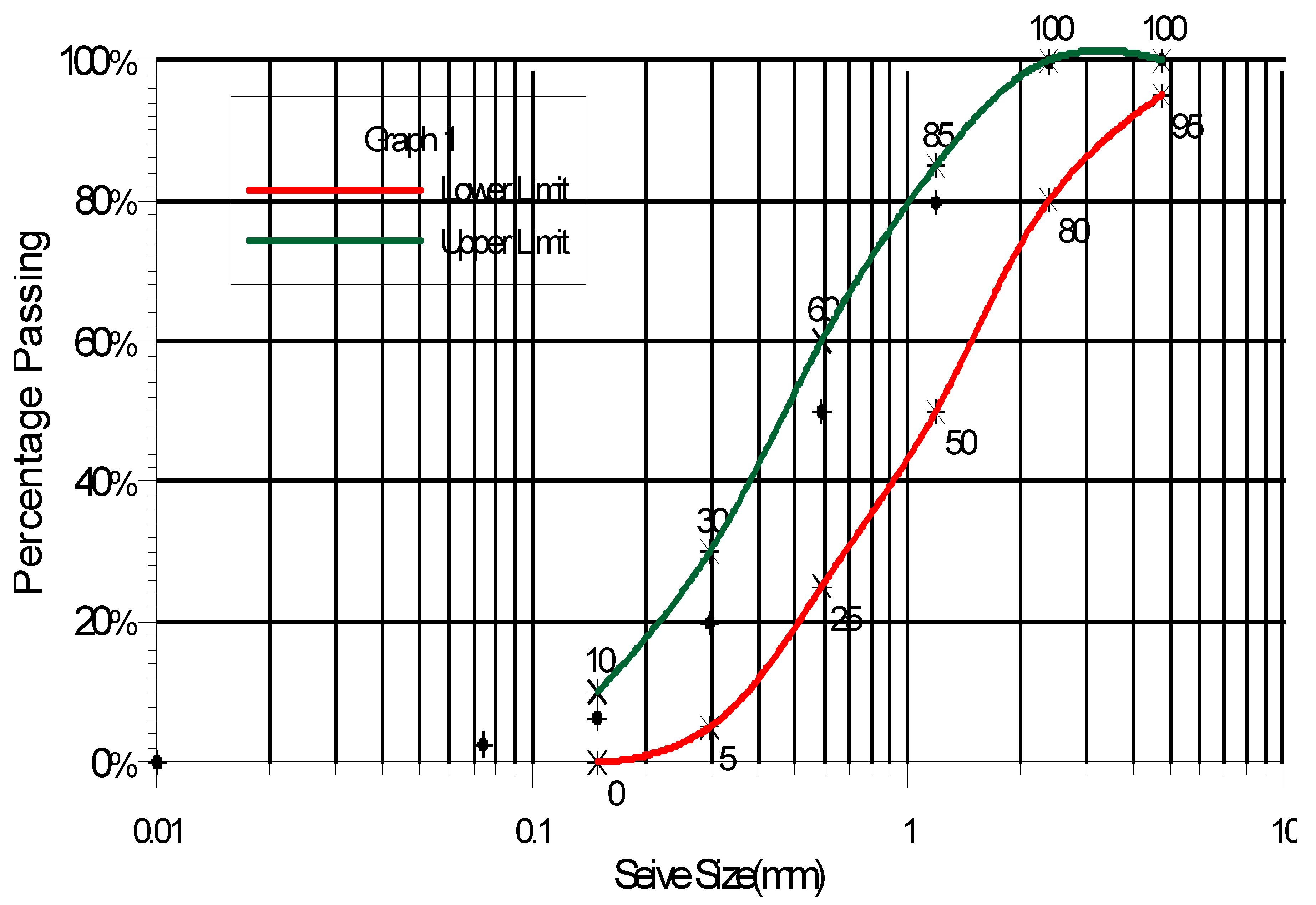

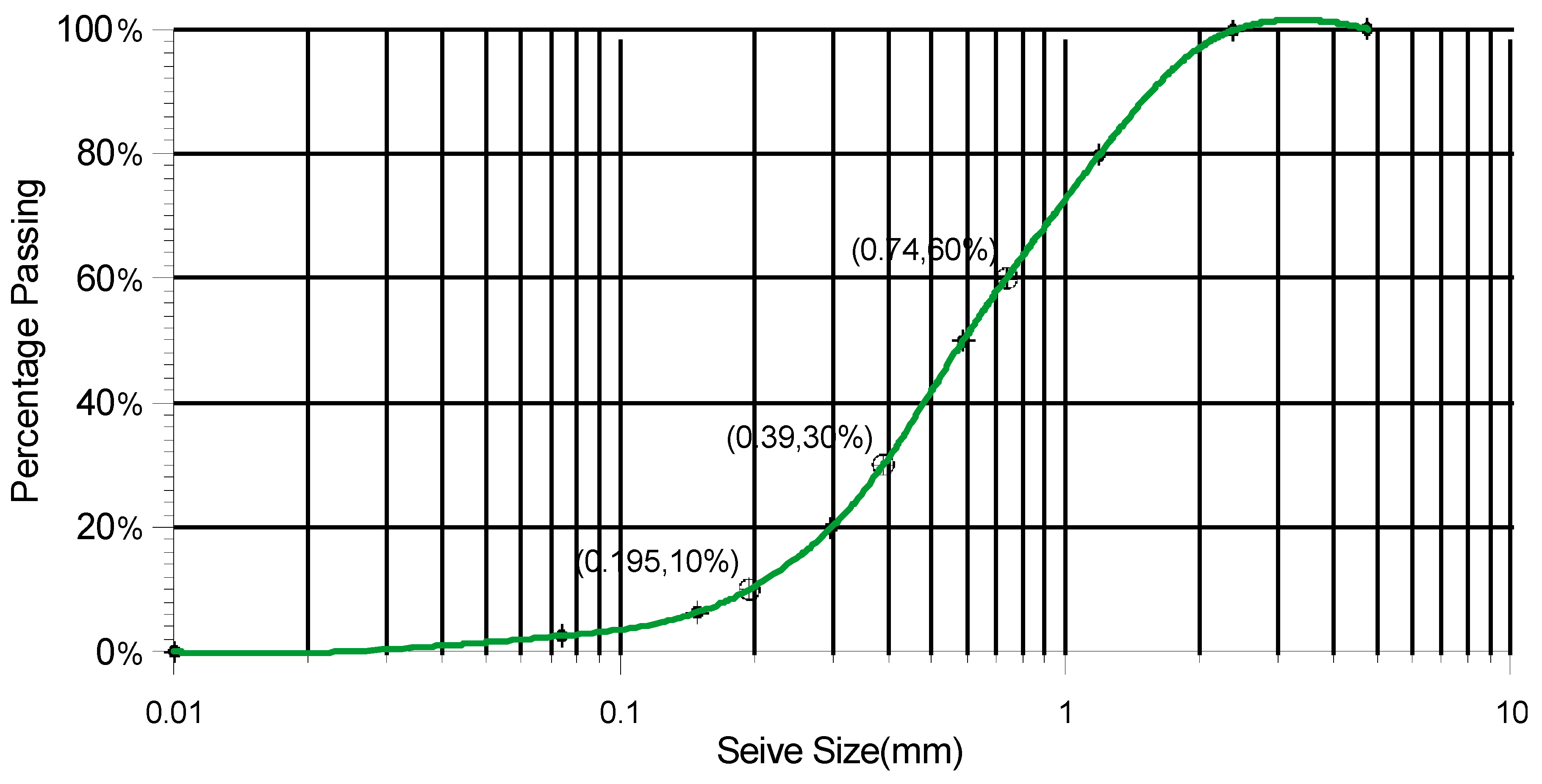

- Oyster Shell

Particle diameter Oyster shell powder at 30% finer (D30) =0.39mm

Particle diameter Oyster shell powder at 60% finer (D60) =0.74mm

Fineness Modulus = (0.00% +0.23% + 20.28% + 50.06% + 80.18% + 93.72%)/100 =2.445

- (3)

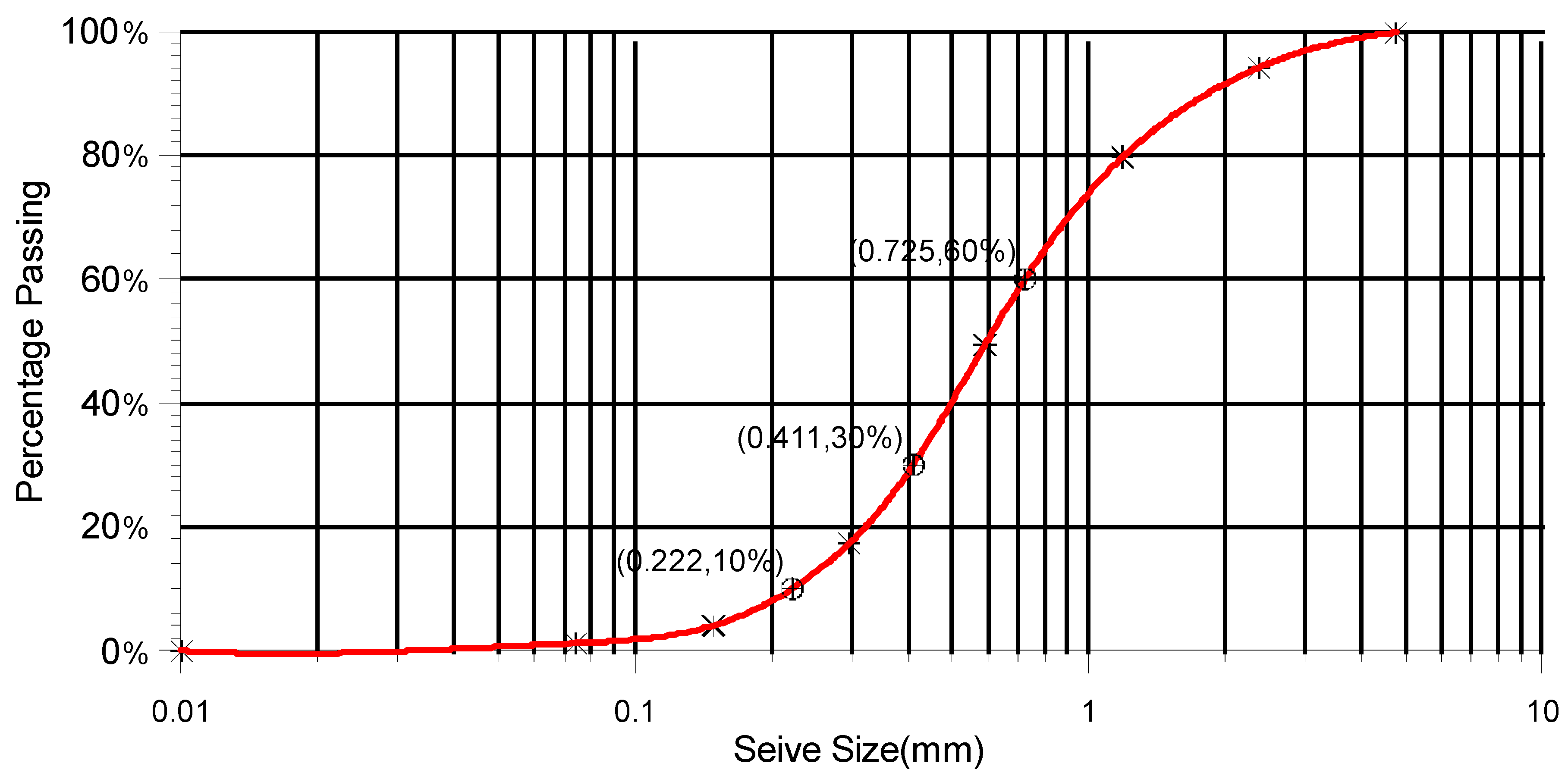

- Aggregate

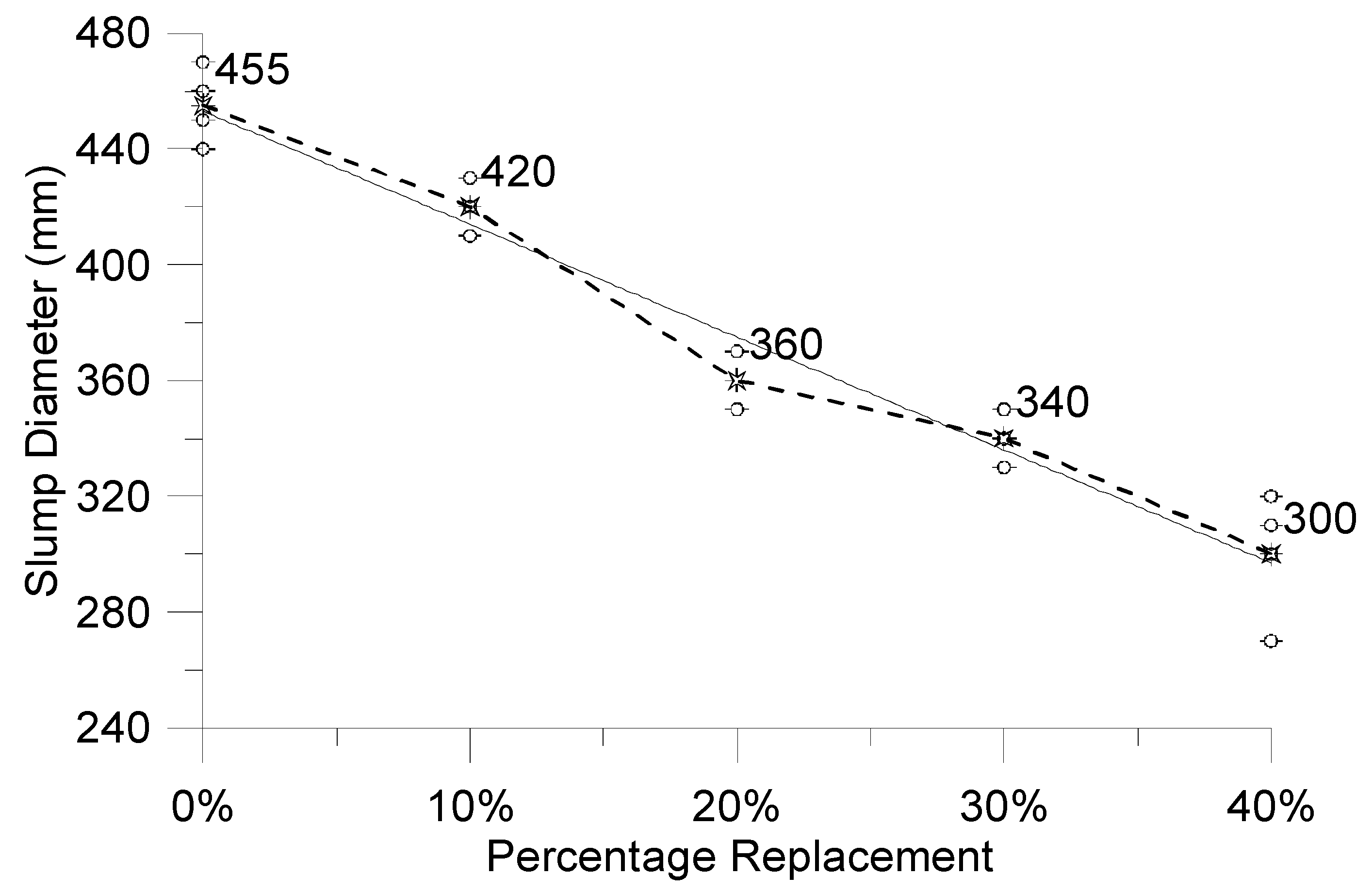

4.2. Workability

| Fine Aggregate Replacement | S.D(d1) | S.D(d2) | S.D(d1) | S.D(d2) | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% Replacement | 470 | 460 | 450 | 440 | 455 |

| 10% Replacement | 430 | 420 | 420 | 410 | 420 |

| 20% Replacement | 370 | 350 | 370 | 350 | 360 |

| 30% Replacement | 350 | 340 | 340 | 330 | 340 |

| 40% Replacement | 320 | 310 | 300 | 270 | 300 |

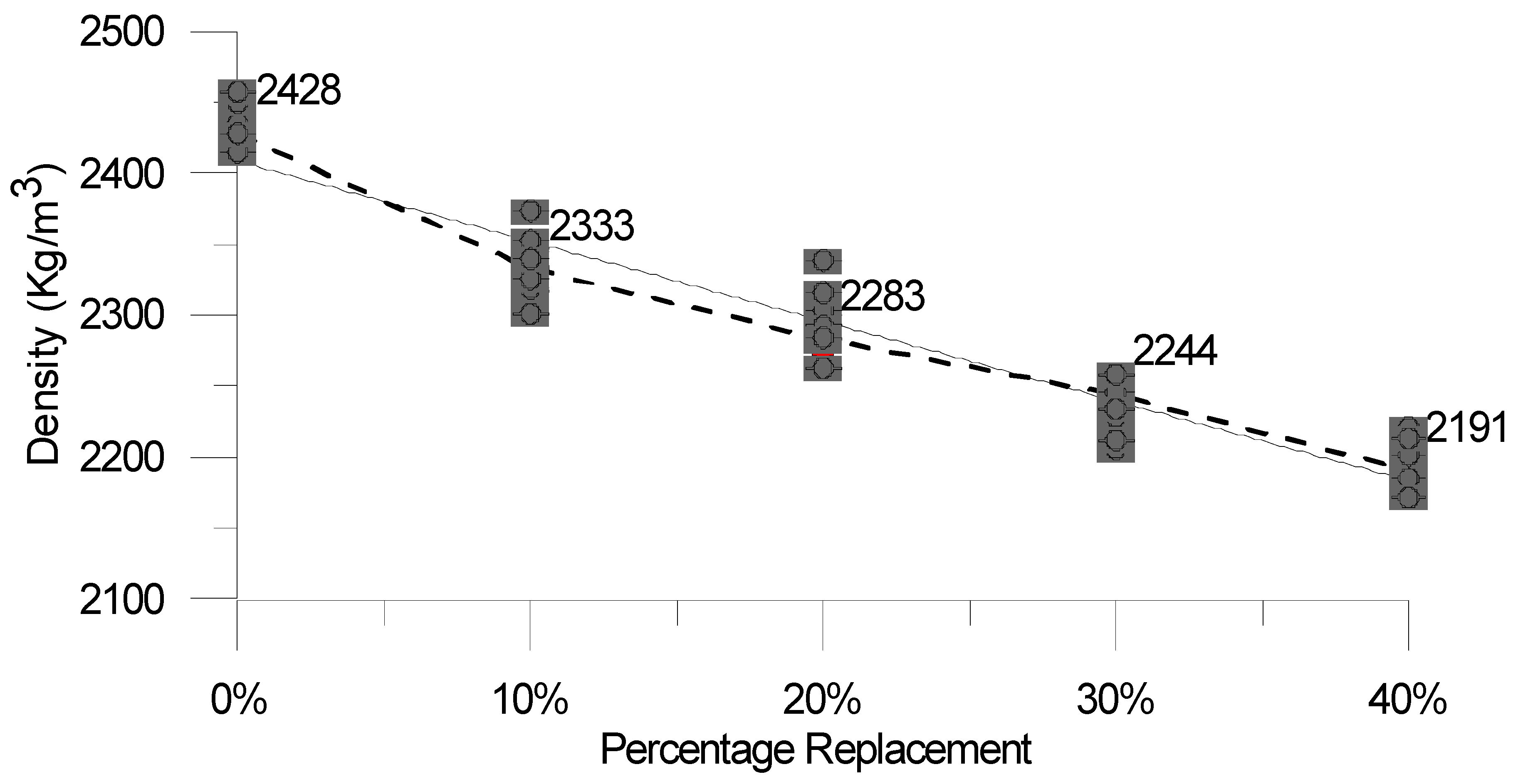

4.3. Density Of Concrete

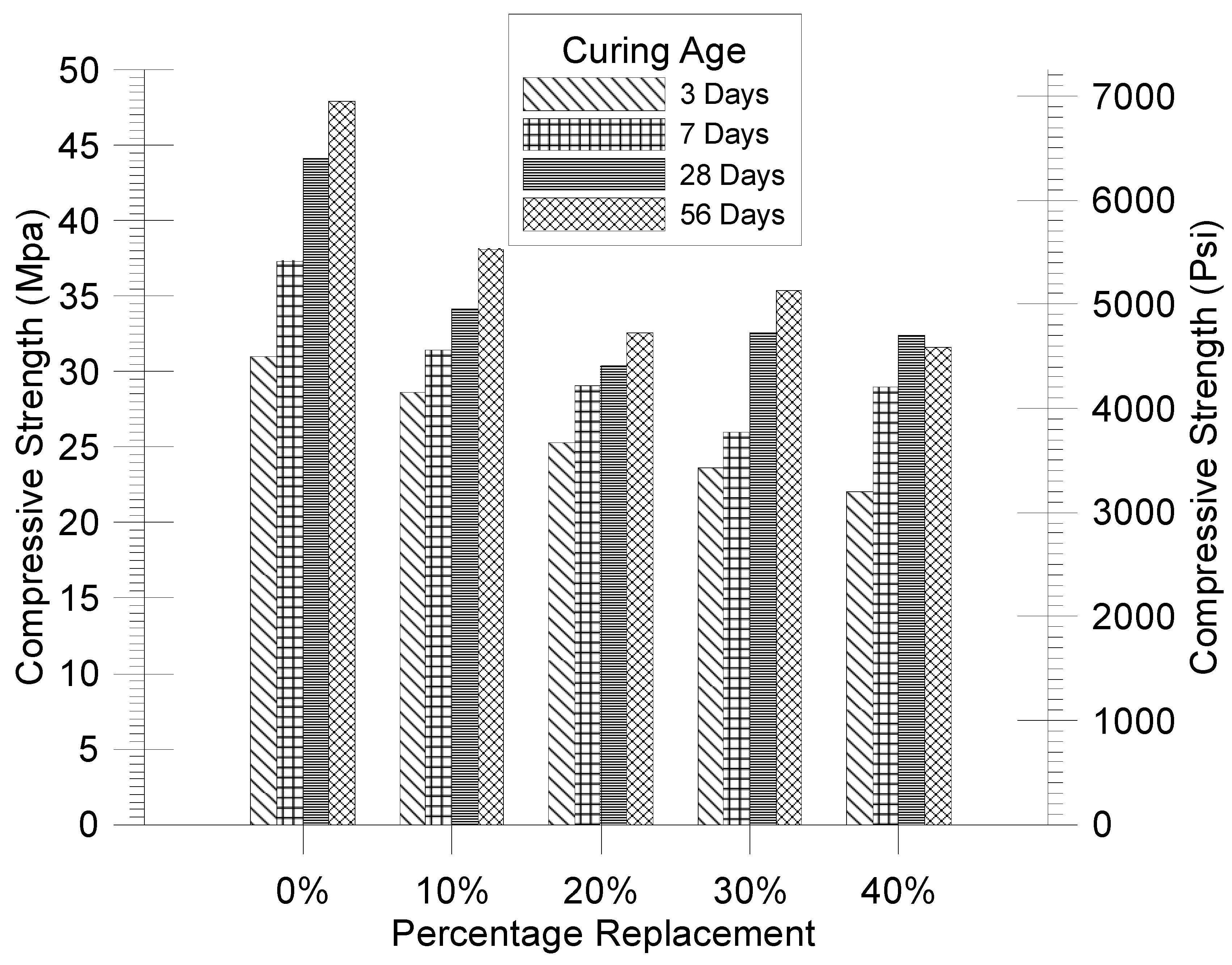

4.4. Compressive Strength

5. Conclusions

- a)

- Oyster shell aggregate has higher absorption compared to the fine aggregate used in this study. This high absorption increases the water demand of concrete, as oyster shell aggregate has more internal structural pores than sand. Consequently, the workability of the wet concrete decreases, and the slump value decreases as the oyster shell content in the concrete increases.

- b)

- There is a linear decrease in concrete density with increasing oyster shell content. Because oyster shell aggregate has a lower specific gravity than fine aggregate, the percentage of oyster shell in concrete has an inverse relationship with the concrete’s density.

- c)

- At a 40% replacement of fine aggregate with oyster shells, a 9.75% decrease in concrete density is observed. The rate of decrease in concrete density is 5.62 kg/cm³ per percentage of replacement.

- d)

- Due to the higher absorption and lower specific gravity of oyster shells compared to the fine aggregates used in this study, oyster shell aggregates are less durable than sand, which contributes to a decrease in compressive strength as oyster shell content increases. However, it is noted that a 30% replacement of fine aggregate performs better in terms of strength than a 20% replacement.

- e)

- While the durability of concrete decreases with oyster shell content, oyster shells can be effective in developing lightweight concrete and aiding in waste management by repurposing oyster shell powder.

Appendix A

|

References

- ASTM-C33-18. Standard Specification for Concrete Aggregates. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM-C39. Standard test method for compressive strength of cylindrical concrete specimens; ASTM C39. 2021.

- ASTM-C127-15. Standard Test Method for Relative Density (Specific Gravity) and Absorption of Coarse Aggregate. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM-C128-15. Standard test method for relative density (specific gravity) and absorption of fine aggregate. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM-C136/C136M-19. Standard Test Method for Sieve Analysis of Fine and Coarse Aggregates. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019. [CrossRef]

- ASTM-C143/C143M-20. Standard Test Method for Slump of Hydraulic-Cement Concrete. ASTM International. Annual book of ASTM Standards. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, 2020.

- ASTM-C192/C192M-19. Standard practice for making and curing concrete test specimens in the laboratory. ASTM Standard Book, 2019.

- ASTM-C470/C470M-15. Standard Specification for Molds for Forming Concrete Test Cylinders Vertically. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM-C494/C494M-19. Standard Specifications for Chemical Admixtures for Concrete. ASTM International. Annual book of ASTM Standards. West Conshohocken: ASTM International, 2019.

- ASTM-C1611/C1611M-21. Standard test method for compressive Standard Test Method for Slump Flow of Self-Consolidating Concrete. ASTM C1611, 2021.

- Binag, N.D. Powdered shell wastes as partial substitute for masonry cement mortar in binder, tiles and bricks production. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2016, 5, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Binag, N.H.D. Utilization of Shell Wastes for Locally Based Cement Mortar and Bricks Production: Its Impact to the Community. KnE Social Sciences 2018, 985–1004–1985–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunyamin, B.; Mukhlis, A. Utilization of Oyster shells as a substitute part of cement and fine aggregate in the compressive strength of concrete. Aceh International Journal of Science and Technology 2020, 9, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, K. Color of Oysters. Retrieved from. Available online: https://www.ehow.com/facts_7447420_color-oysters.html.

- CNS-61-R2001. Chinese National Standards, Portland cement. 2011. Retrieved from. Available online: http://www.cnsonline.com.tw/?node=detail&generalno=61&locale=zh_TW.

- Corporation, T.S. Sustainable Development of Taiwan Sugar Corporation. 2019. Retrieved from. 1230. Available online: https://www.taisugar.com.tw/CSR/en/CP2.aspx?n=12300.

- Ekop, I.; Adenuga, O.; Umoh, A. Strength characteristics of granite–pachimalania aurita shell concrete. Nigerian journal of Agriculture, Food and Environment. 2013, 9, pp. 9–14. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ifiok_Ekop3/publication/348064883_STRENGTH_CHARACTERISTICS_OF_GRANITE-Pachymelania_aurita_SHELL_CONCRETE/links/5fee1a3e45851553a00d0c9f/STRENGTH-CHARACTERISTICS-OF-GRANITE-Pachymelania-aurita-SHELL-CONCRETE.pdf.

- Eo, S.-H.; Yi, S.-T. Effect of oyster shell as an aggregate replacement on the characteristics of concrete. Magazine of Concrete Research 2015, 67, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eo, S.H.; Choi, D.J.; Park, Y.K.; Hong, K.H.; HK. An experimental study on the use of oyster shells as aggregate in concrete. Proceedings of the Korea Concrete Institute, 2001.05. 2001. Available online: http://www.koreascience.or.kr/article/CFKO200111921190396.pdf.

- Ettu, L.; Ibearugbulem, O.; Ezeh, J.; Anya, C. A reinvestigation of the prospects of using periwinkle shell as partial replacement for granite in concrete. 2013, 2, 54–59. Available online: http://www.ijesi.org/papers/Vol(2)3%20(Version-3)/I235459.pdf.

- Etuk, B.R.; Etuk, I.F.; Asuquo, L.O. Feasibility of using sea shells ash as admixtures for concrete. Journal of Environmental Science and Engineering 2012, A, 1. [Google Scholar]

- F; F; Ikponmwosa, E.; Ojediran, N. Behaviour of lightweight concrete containing periwinkle shells at elevated temperature. Journal of Engineering Science and Technology. 2010, 5. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/49596224_Behaviour_of_lightweight_concrete_containing_periwinkle_shells_at_elevated_temperature.

- Falade, F. An investigation of periwinkle shells as coarse aggregate in concrete. Building and Environment 1995, 30, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, L.; Peduzzi, P. Sand and sustainability: Finding new solutions for environmental governance of global sand resources. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, S.; Sovacool, B.K.; Furszyfer Del Rio, D.D.; Foley, A.M.; Bazilian, M.D.; Kim, J. Decarbonizing the cement and concrete industry: a systematic review of socio-technical systems, technological innovations, and policy options. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 180, 113291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, A. B. A. Workability and Compressive Strength of Concrete Containing Crushed Cockle Shell as Partial Fine Aggregate Replacement Material; UMP, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinpanahi, A.; Shen, L.; Dera, P.; Mirmoghtadaei, R. Properties and microstructure of concrete and cementitious paste with liquid carbon dioxide additives. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 414, 137293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Lee, D.K.; Ali, M.A.; Kim, P.J. Effects of oyster shell on soil chemical and biological properties and cabbage productivity as a liming materials. Waste Management 2008, 28, 2702–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lertwattanaruk, P.; Makul, N.; Siripattarapravat, C. Utilization of ground waste seashells in cement mortars for masonry and plastering. Journal of Environmental Management 2012, 111, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, C. The greening of the concrete industry. Cement and Concrete Composites 2009, 31, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivia, M. , Oktaviani, R., & Ismeddiyanto. Properties of Concrete Containing Ground Waste Cockle and Clam Seashells. Procedia Engineering 2017, 171, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ProStar SP10. Retrieved from. Available online: http://www.hicon.com.tw/newproducts/sp100.html.

- Reports-and-Data. Aggregates Market To Reach USD 723.28 Billion By 2027|Reports and Data. GlobeNewswire News Room. 2020. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/06/24/2052902/0/en/Aggregates-Market-To-Reach-USD-723-28-Billion-By-2027-Reports-and-Data.html.

- Sah, A.K.; Hong, Y.-M. Circular Economy Implementation in an Organization: A Case Study of the Taiwan Sugar Corporation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scibilia, E. Environmental Impact and Sustainability in Aggregate Production and Use. 2014, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Soneye, T.; Ede, A.; Bamigboye, G.; Olukanni, D. The Study of Periwinkle Shells as Fine and Coarse Aggregate in Concrete Works; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Strategic-Business-Plan-ISO/TC-071. STRATEGIC BUSINESS PLAN ISO/TC 071. 2016. Retrieved from. Available online: https://isotc.iso.org/livelink/livelink/fetch/2000/2122/687806/ISO_TC_071__Concrete__reinforced_concrete_and_pre-stressed_concrete_.pdf?nodeid=1162199&vernum=0.

- Taiwan Introduces Aggregates Management System. Aggregates Business. 2020. Available online: https://www.aggbusiness.com/ab10/feature/taiwan-introduces-aggregates-management-system.

- Tattersall, G. H. Workability and quality control of concrete; CRC Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, B.; Bustamante, M.; Muñoz, P.; Ortega, J.M.; Loyola, E.; Letelier, V. Physical and mechanical behavior of concrete specimens using recycled aggregate coated with recycled cement paste. Construction and Building Materials 2023, 393, 132015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.I.; Kim, M.-Y.; Park, H.-G.; Yi, S.-T. Effect of partial replacement of sand with dry oyster shell on the long-term performance of concrete. Construction and Building Materials - CONSTR BUILD MATER 2010, 24, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.I.; Yi, S.-T.; Leem, Y.-M. Effect of oyster shell substituted for fine aggregate on concrete characteristics: Part I. Fundamental properties. Cement and Concrete Research 2005, 2175–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, G.-L.; Kim, B.-T.; Kim, B.-O.; Han, S.-H. Chemical-mechanical characteristics of crushed oyster-shell. Waste management (New York, N.Y.) 2003, 23, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, G.-L.; Kim, B.-T.; Kim, B.-O.; Han, S.-H. Chemical–mechanical characteristics of crushed oyster-shell. Waste Management 2003, 23, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.; Park, S.; Lee, K.; Park, J. Oyster Shell as Substitute for Aggregate in Mortar. Waste Management & Research 2004, 22, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sieve | % Passing |

|---|---|

| 9.5-mm (3 ⁄ 8-in.) | 100 |

| 4.75-mm (No. 4) | 95 to 100 |

| 2.36-mm (No.8) | 80 to 100 |

| 1.18-mm (No.16) | 50 to 85 |

| 600-μm (No.30) | 25 to 60 |

| 300-μm (No.50) | 5 to 30 |

| 150-μm (No.100) | 0 to 10 |

| Reference | Components(%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaCO3 | SiO2 | MgO | Al2O3 | SrO | P2O5 | Na2O | SO3 | |

| Yoon et al. (2003a) | 95.994 | 0.696 | 0.649 | 0.419 | 0.33 | 0.204 | 0.984 | 0.724 |

| Lee et al. (2008) | 95.9 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.42 | - | 0.2 | 0.98 | - |

| Eo & Yi (2015) | 97.244 | 0.428 | 0.482 | 0.449 | 0.198 | 0.179 | 0.539 | 0.479 |

| Reference | Component (%) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaO | SiO2 | MgO | Al2O3 | SrO | P2O5 | Na2O | SO3 | Fe2O3 | K2O | TiO2 | Mn2O3 | *Ig. Loss | |

| Yang et al. (2005) | 51.06 | 2 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 44.16 |

| Yoon, et al. (2004) | 52.94 | 0.62 | 0.78 | - | - | 0.17 | 0.93 | - | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.01 | - | 44.02 |

| Etuk et al. (2012) | 57.95 | 13.41 | 0.19 | 4.95 | - | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 3.80 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 18.60 |

| Bunyamin & Mukhlis (2020) | 51.56 | 1.60 | 1.43 | 0.92 | - | - | 0.08 | 0.06 | - | 42.15 | |||

| OS. Replacement with Sand | W/C Ratio | Mix Percentage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement | FINE AGGREGATE | 10 mm Aggregate | 20 mm Aggregate | OS. | ||

| 0% | 0.5 | 16.67% | 33.33% | 25.00% | 25.00% | 0.00% |

| 10% | 0.5 | 16.67% | 30.00% | 25.00% | 25.00% | 3.33% |

| 20% | 0.5 | 16.67% | 26.67% | 25.00% | 25.00% | 6.67% |

| 30% | 0.5 | 16.67% | 23.33% | 25.00% | 25.00% | 10.00% |

| 40% | 0.5 | 16.67% | 20.00% | 25.00% | 25.00% | 13.33% |

| Age Of Mortar | Compressive Strength (Kg/cm2) | Compressive Strength (Mpa) |

|---|---|---|

| 3 Days | 255 | 25.01 |

| 7 Days | 362 | 35.50 |

| 28 Days | 460 | 45.11 |

| Author | S. G | Country | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Eo & Yi, 2015) | 2.66 | South Korea | Substitution In Concrete |

| (Yang et al., 2010) | 2.48 | South Korea | |

| (Yang et al., 2005) | 2.39 | South Korea | |

| (Lertwattanaruk et al., 2012) | 2.65 | Thailand | Substitution In Mortar |

| (N. D. Binag, 2016) | 3.09 | Philippines | |

| (G.-L. Yoon, Kim, Kim, & Han, 2003b) | 2.568 | South Korea | |

| (H. Yoon et al., 2004) | 2.41 | South Korea |

| Description | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Of Empty Pycnometer (A1) | 435.5 g | 435.5 g | 435.5 g |

| Weight Of Pycnometer + Sample (A2) | 523.5 g | 463.5 g | 471.5 g |

| Weight Of Pycnometer + Sample + Water(A3) | 1503 g | 1470.5 g | 1475 g |

| Weight Of Pycnometer + Water (A4) | 1455.5 g | 1455.5 g | 1455.5 g |

| Specific Gravity | 2.173 | 2.154 | 2.182 |

| Average Specific Gravity | 2.17 | ||

| Sieve No. | Sieve Size (mm) | Percentage Passing | (ASTM-C33-18, 2018) | Percentage Retained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. 4 | 4.75 | 100.00% | 95 – 100 % | 0.00% |

| No. 8 | 2.36 | 99.77% | 80 – 100 % | 0.23% |

| No. 16 | 1.18 | 79.72% | 50 – 85 % | 20.28% |

| No. 30 | 0.600 | 49.94% | 25 – 60 % | 50.06% |

| No. 50 | 0.300 | 19.82% | 5 – 30 % | 80.18% |

| No. 100 | 0.150 | 6.28% | 0 – 10% | 93.72% |

| No. 200 | 0.074 | 2.54% | 97.46% | |

| Collector | Collector | 0.00% | 100.00% |

| Description | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Of Empty Pycnometer (A1) | 435.50 g | 435.50 g | 435.50 g |

| Weight Of Pycnometer + Sample (A2) | 638.50 g | 611.00 g | 541.50 g |

| Weight Of Pycnometer+Sample+Water(A3) | 1582.00 g | 1565.00 g | 1521.50 g |

| Weight Of Pycnometer + Water (A4) | 1455.50 g | 1455.50 g | 1455.50 g |

| Specific Gravity | 2.654 | 2.659 | 2.650 |

| Average Specific Gravity | 2.654 | ||

| Description | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Of Empty Pycnometer (A1) | 435.5g | 435.5g | 435.5g |

| Weight Of Pycnometer + Sample (A2) | 599.0g | 612.0g | 639.5g |

| Weight Of Pycnometer + Sample+Water(A3) | 1559.0g | 1566.5g | 1583.0g |

| Weight Of Pycnometer + Water (A4) | 1455.5g | 1455.5g | 1455.5g |

| Specific Gravity | 2.726 | 2.695 | 2.666 |

| Average Specific Gravity | 2.695 | ||

| Description | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Of Empty Pycnometer (A1) | 435.50 g | 435.50 g | 435.50 g |

| Weight Of Pycnometer + Sample (A2) | 638.50 g | 611.00 g | 541.50 g |

| Weight Of Pycnometer+Sample+ Water(A3) | 1582.00 g | 1566.00 g | 1522.16 g |

| Weight Of Pycnometer + Water (A4) | 1455.50 g | 1455.50 g | 1455.50 g |

| Specific Gravity | 2.654 | 2.700 | 2.694 |

| Average Specific Gravity | 2.683 | ||

| Sieve No. | Sieve Size (mm) | Percentage Passing | (ASTM-C33-18, 2018) | Percentage Retained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. 4 | 4.75 | 99.77% | 95 – 100 % | 0.23% |

| No. 8 | 2.36 | 94.18% | 80 – 100 % | 5.82% |

| No. 16 | 1.18 | 79.68% | 50 – 85 % | 20.32% |

| No. 30 | 0.600 | 49.34% | 25 – 60 % | 50.66% |

| No. 50 | 0.300 | 17.33% | 5 – 30 % | 82.67% |

| No. 100 | 0.150 | 4.09% | 0 – 10% | 95.91% |

| No. 200 | 0.074 | 1.23% | 98.77% | |

| Collector | Collector | 0.00% | 100.00% |

| S.No | 0% | 10% | 20% | 30% | 40% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2448.11 | 2333.72 | 2300.01 | 2241.43 | 2214.17 |

| 2 | 2435.22 | 2300.93 | 2284.35 | 2205.88 | 2174.38 |

| 3 | 2416.80 | 2344.77 | 2303.33 | 2253.77 | 2184.88 |

| 4 | 2420.48 | 2373.69 | 2315.85 | 2211.96 | 2214.17 |

| 5 | 2449.59 | 2318.98 | 2292.46 | 2239.96 | 2174.38 |

| 6 | 2426.01 | 2325.61 | 2338.51 | 2245.48 | 2184.88 |

| 7 | 2414.96 | 2347.35 | 2282.51 | 2258.19 | 2171.62 |

| 8 | 2457.32 | 2352.32 | 2284.17 | 2228.91 | 2220.43 |

| 9 | 2427.85 | 2339.61 | 2262.80 | 2233.88 | 2213.25 |

| 10 | 2450.18 | 2316.96 | 2283.62 | 2250.09 | 2201.46 |

| 11 | 2411.27 | 2317.88 | 2236.46 | 2282.69 | 2141.22 |

| 12 | 2376.27 | 2322.67 | 2213.80 | 2279.01 | 2197.22 |

| Mean | 2427.84 | 2332.88 | 2283.16 | 2244.27 | 2191.01 |

| FINE AGGREGATE Replacement with Oyster Shell | Compressive Strength (Mpa) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Days | 7 Days | 28 Days | 56 Days | |

| 0% | 31.00 | 37.34 | 44.12 | 47.93 |

| 10% | 28.63 | 31.42 | 34.16 | 38.14 |

| 20% | 25.31 | 29.03 | 30.40 | 32.56 |

| 30% | 23.59 | 26.02 | 32.54 | 35.35 |

| 40% | 22.08 | 28.97 | 32.36 | 31.58 |

| FINE AGGREGATE Replacement | Age | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Standard Deviation(σ) | Mean | σ/Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 3 Days | 32.30 Mpa | 32.41 Mpa | 28.28 Mpa | 2.4 | 31.00 Mpa | 0.076 |

| 4684.73 Psi | 4700.68 Psi | 4101.67 Psi | 341.3 | 4495.69 Psi | 0.076 | ||

| 7 Days | 37.63 Mpa | 37.76 Mpa | 36.64 Mpa | 0.6 | 37.34 Mpa | 0.016 | |

| 5457.78 Psi | 5476.63 Psi | 5314.19 Psi | 88.8 | 5416.20 Psi | 0.016 | ||

| 28 Days | 43.64 Mpa | 46.23 Mpa | 42.49 Mpa | 1.9 | 44.12 Mpa | 0.043 | |

| 6329.46 Psi | 6705.11 Psi | 6162.66 Psi | 277.8 | 6399.08 Psi | 0.043 | ||

| 56 Days | 49.89 Mpa | 46.61 Mpa | 47.29 Mpa | 1.7 | 47.93 Mpa | 0.036 | |

| 7235.95 Psi | 6760.22 Psi | 6858.85 Psi | 251.1 | 6951.67 Psi | 0.036 | ||

| 10% | 3 Days | 29.46 Mpa | 27.79 Mpa | 28.64 Mpa | 0.8 | 28.63 Mpa | 0.029 |

| 4272.82 Psi | 4030.61 Psi | 4153.89 Psi | 121.1 | 4152.44 Psi | 0.029 | ||

| 7 Days | 32.03 Mpa | 31.21 Mpa | 31.03 Mpa | 0.5 | 31.42 Mpa | 0.017 | |

| 4645.57 Psi | 4526.64 Psi | 4500.53 Psi | 77.3 | 4557.58 Psi | 0.017 | ||

| 28 Days | 31.08 Mpa | 35.67 Mpa | 35.75 Mpa | 2.7 | 34.17 Mpa | 0.078 | |

| 4507.78 Psi | 5173.51 Psi | 5185.11 Psi | 387.7 | 4955.47 Psi | 0.078 | ||

| 56 Days | 35.30 Mpa | 38.93 Mpa | 40.18 Mpa | 2.5 | 38.14 Mpa | 0.066 | |

| 5119.84 Psi | 5646.33 Psi | 5827.63 Psi | 367.7 | 5531.27 Psi | 0.066 | ||

| 20% | 3 Days | 27.92 Mpa | 25.35 Mpa | 22.66 Mpa | 2.6 | 25.31 Mpa | 0.104 |

| 4049.46 Psi | 3676.71 Psi | 3286.56 Psi | 381.5 | 3670.91 Psi | 0.104 | ||

| 7 Days | 29.60 Mpa | 31.14 Mpa | 26.36 Mpa | 2.4 | 29.03 Mpa | 0.084 | |

| 4293.12 Psi | 4516.48 Psi | 3823.20 Psi | 353.9 | 4210.94 Psi | 0.084 | ||

| 28 Days | 33.88 Mpa | 29.62 Mpa | 27.69 Mpa | 3.2 | 30.40 Mpa | 0.104 | |

| 4913.89 Psi | 4296.03 Psi | 4016.10 Psi | 459.4 | 4408.67 Psi | 0.104 | ||

| 56 Days | 31.14 Mpa | 32.90 Mpa | 33.66 Mpa | 1.3 | 32.57 Mpa | 0.040 | |

| 4516.48 Psi | 4771.75 Psi | 4881.98 Psi | 187.5 | 4723.40 Psi | 0.040 | ||

| 30% | 3 Days | 24.58 Mpa | 23.92 Mpa | 22.27 Mpa | 1.2 | 23.59 Mpa | 0.050 |

| 3565.03 Psi | 3469.31 Psi | 3230.00 Psi | 172.6 | 3421.45 Psi | 0.050 | ||

| 7 Days | 28.22 Mpa | 25.09 Mpa | 24.74 Mpa | 1.9 | 26.02 Mpa | 0.074 | |

| 4092.97 Psi | 3639.00 Psi | 3588.24 Psi | 277.9 | 3773.41 Psi | 0.074 | ||

| 28 Days | 33.93 Mpa | 32.54 Mpa | 31.17 Mpa | 1.4 | 32.55 Mpa | 0.042 | |

| 4921.14 Psi | 4719.54 Psi | 4520.83 Psi | 200.2 | 4720.50 Psi | 0.042 | ||

| 56 Days | 35.72 Mpa | 35.45 Mpa | 34.90 Mpa | 0.4 | 35.36 Mpa | 0.012 | |

| 5180.76 Psi | 5141.60 Psi | 5061.83 Psi | 60.6 | 5128.06 Psi | 0.012 | ||

| 40% | 3 Days | 22.41 Mpa | 21.80 Mpa | 22.02 Mpa | 0.3 | 22.08 Mpa | 0.014 |

| 3250.30 Psi | 3161.83 Psi | 3193.74 Psi | 44.8 | 3201.96 Psi | 0.014 | ||

| 7 Days | 29.07 Mpa | 28.32 Mpa | 29.52 Mpa | 0.6 | 28.97 Mpa | 0.021 | |

| 4216.25 Psi | 4107.48 Psi | 4281.52 Psi | 87.9 | 4201.75 Psi | 0.021 | ||

| 28 Days | 30.14 Mpa | 34.00 Mpa | 32.95 Mpa | 2.0 | 32.36 Mpa | 0.062 | |

| 4371.45 Psi | 4931.29 Psi | 4779.00 Psi | 289.5 | 4693.91 Psi | 0.062 | ||

| 56 Days | 32.84 Mpa | 31.73 Mpa | 30.18 Mpa | 1.3 | 31.58 Mpa | 0.042 | |

| 4763.05 Psi | 4602.06 Psi | 4377.25 Psi | 193.8 | 4580.78 Psi | 0.042 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).