1. Introduction

Currently, deep learning technology is rapidly advancing, achieving significant results across various fields through data-driven methods. High-quality training samples are fundamental to achieving outstanding performance, thus the demand for sufficient and high-quality datasets is becoming increasingly urgent. However, in the field of remote sensing, especially in image segmentation tasks, obtaining high-quality remote sensing images and their semantic labels through manual annotation still faces many challenges, such as the time-consuming and labor-intensive nature of labeling, which hinders the full realization of the advantages of data-driven approaches [

1,

2]. In this context, data augmentation serves as an effective method that can significantly expand the data size by transforming the original images or generating new images from existing data [

3,

4].

Transformation-based augmentation includes color space transformations that modify pixel intensity values (e.g., brightness, contrast adjustment) and geometric transformations that update the spatial locations of pixels (e.g., affine transformations), while synthetic-based augmentation resorts to generative methods (e.g., neural style transfer [

5]) and mixing augmentations (e.g., MixUp [

6], CutMix [

7]) [

8]. Although these approaches increase the dataset size, they primarily focus on individual images or image pairs, utilizing only intrinsic image information or the mutual information between pairs. As a result, the augmented data introduces limited prior knowledge, producing new samples that closely mimic existing patterns with minimal informational novelty. This lack of diversity in the generated data reduces the effectiveness of these methods in enhancing model performance [

9].

In recent years, GAN-based synthetic methods have introduced innovative approaches to data augmentation [

10]. The model generates high-quality new images by learning the overall distribution of the data. In the field of remote sensing, numerous studies have utilized GANs to generate samples for data augmentation. CSEBGAN generates realistic remote sensing images based on semantic labels by decoupling different semantic classes into independent embeddings [

11], achieving finer-grained diversity. Kuang et al. proposes a semantic-layout-guided collaborative framework for SAR sample generation to enhance sample diversity and improve detection performance [

12]. Remusati et al. explores the use of GANs to enhance the explainability and performance of SAR Automatic Target Recognition (ATR) and classification models, addressing both the generation of synthetic data and the development of methods for better understanding model decisions [

13]. Fu et al. presents a novel denoising GAN for colorizing satellite remote sensing grayscale images, which outperforms existing techniques and improves building detection performance [

14]. Rui et al. introduces DisasterGAN to synthesize diverse remote sensing disaster images with multiple types of disasters and varying building damage, addressing the challenges of class imbalance and limited training data in existing datasets [

15]. Simonyan and Zisserman enhanced the WGAN [

16] to generate remote sensing images of construction waste, ensuring realistic edge and texture representation [

17]. Kong et al. utilized Pix2Pix [

18] and PS-GAN [

19] to generate pedestrian samples along railroad perimeters [

20], improving safety monitoring by providing additional training data for detection algorithms. Similarly, Yang applied GANs to create water flow images across natural and artificial environments, augmenting datasets and improving the accuracy of flow rate estimation for classification networks [

21]. Wang Y et al. refined a conditional GAN (cGAN) by incorporating perceptual loss and structural similarity metrics with masks, enhancing the quality of aircraft region generation and resolving sample scarcity in aircraft recognition tasks [

22]. Jiang Y et al. improved StyleGAN2 [

23] and integrated the generated images into the YOLOv3 [

24] training dataset, ultimately boosting the accuracy of object detection and recognition [

25].

Our research aims to generate remote sensing satellite images from semantic labels to enhance deep learning datasets. Initially, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) could only generate samples from noise. However, with the rapid development of GANs, the emergence of Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks (cGANs) has enabled the generation of images using category labels, text descriptions, and other images as conditions. Based on this, numerous advancements in GAN-based label-to-image translation techniques have emerged, providing strong technical support for generating satellite images from labels, thus offering effective methods for expanding remote sensing datasets using semantic maps. Pix2Pix [

26] employs the U-Net [

27] architecture for the generator and the PatchGAN discriminator, improving the quality of image synthesis. Pix2PixHD [

28] further refines Pix2Pix by optimizing the model structure, loss function, and semantic processing, enabling the generation of high-resolution images. GauGAN addresses the limitations of conventional approaches—where semantic label maps are processed through convolution-normalization-nonlinear layers [

29], leading to information loss—by introducing Spatially Adaptive Normalization (SPADE), which preserves semantic information and improves image quality. DAGAN [

30] and DPGAN [

31] enhance image-level synthesis by adding functional modules, but these methods still struggle to capture category-specific characteristics, limiting the generation of detailed remote sensing images. To address this, LGGAN [

32] and CollageGAN [

33] employ distinct models for different semantic categories. However, LGGAN’s class-specific generators, built with basic convolutional layers, are insufficient for generating intricate geographic objects, while CollageGAN is unsuitable for remote sensing images that lack clear foreground-background segmentation. SEAN [

34] and CLADE [

35] improve image synthesis by designing normalization methods that leverage semantic constraints, enhancing both image quality and model performance. DP-SIMS [

36] integrates a pre-trained backbone network as the encoder in the discriminator and employs cross-attention mechanisms for noise injection, significantly enhancing image quality and consistency while reducing computational costs.

Currently, GAN-based label-to-image translation methods have achieved outstanding results on scene datasets such as COCO-Stuff [

37], Cityscapes [

38], and ADE-20K [

39]. However, generating satellite images from remote sensing semantic labels still faces several challenges on remote sensing datasets:

1. Existing image synthesis methods often rely on datasets with simple image forms and low data complexity. These methods may not be suitable when confronted with challenges such as high data imbalance and high semantic similarity among land cover classes, which are prevalent in remote sensing images. Specifically, in remote sensing datasets, the spatial distributions of different land cover types exhibit diverse patterns and regularities. Moreover, certain land cover types, such as vegetation and background, exhibit high semantic similarity. These challenges can lead to poor quality of generated samples for underrepresented land cover classes and make it difficult to differentiate between land cover types with high semantic similarity. As a result, a single generator structure struggles to effectively capture and generate the diverse characteristics of these land cover types.

2. Existing multi-task generators face challenges in effectively balancing the generation of samples for different land cover types, leading to significant interference between generators. This interference complicates the training process and results in confusion or overlap in the generated images, such as distorted building structures and unrealistic texture details.

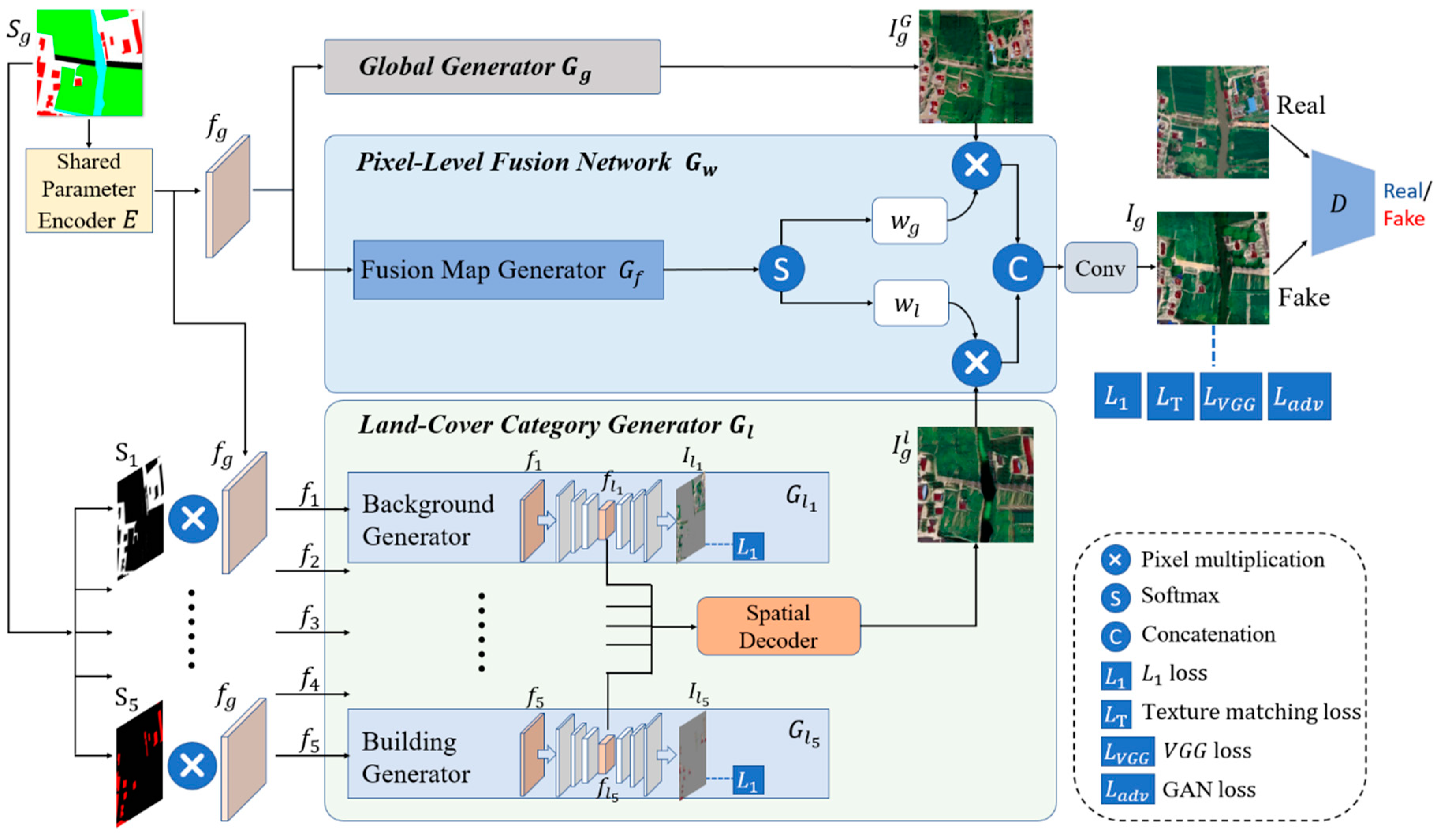

To address these challenges, we employ a Multi-task GAN (MTGAN) to augment the dataset of remote sensing images, specifically focusing on five typical land cover classes: water, buildings, vegetation, roads, and others. Our primary goal is to tackle the complexities involved in generating samples for these land cover categories, particularly the challenges associated with creating intricate building structures and addressing the limited representation of certain land cover types. Our key contribution is the development of a generation model that leverages the existing dataset to ensure the diversity and richness of samples necessary for effective semantic segmentation of remote sensing images, thereby enhancing segmentation accuracy. The contributions of this paper are summarized as follows.

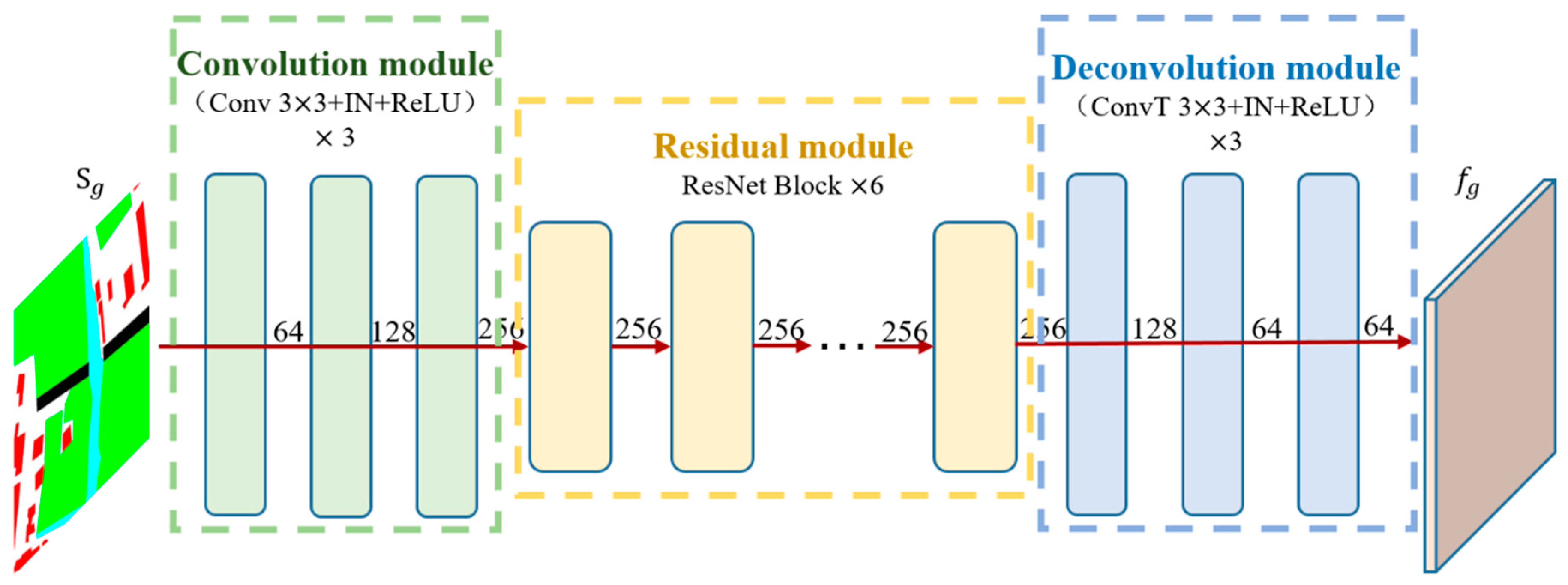

1. Our proposed model adopts a dual-branch multi-task generator architecture, where the land cover class-specific generators focus on targeted generation for individual categories. This design overcomes the limitations of the global generator in capturing detailed features across diverse land cover types, enabling the model to effectively generate objects for underrepresented classes and distinguish between land cover types with high semantic similarity.

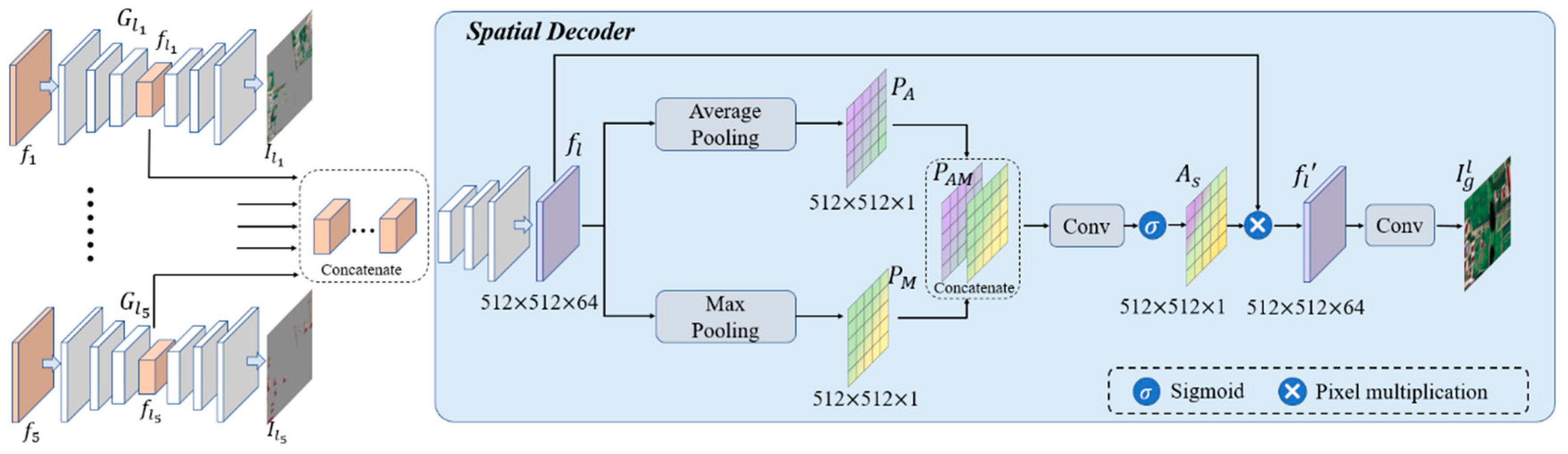

2. To integrate these multi-task generators, we design a shared parameter encoder for consistent feature encoding across both the global and class-specific branches, and a spatial decoder that synthesizes outputs from the class-specific generators, preventing overlap and confusion. This design mitigates the mutual influence among generators, ensuring more consistent outputs.

3. We employ perceptual loss () to compute the perceptual similarity of images and use texture matching loss ( to assess the differences in texture details between generated and real images via the Gram matrix. By combining these two loss functions, we enhance the color, texture, and perceptual authenticity of the generated images, ensuring higher output quality.

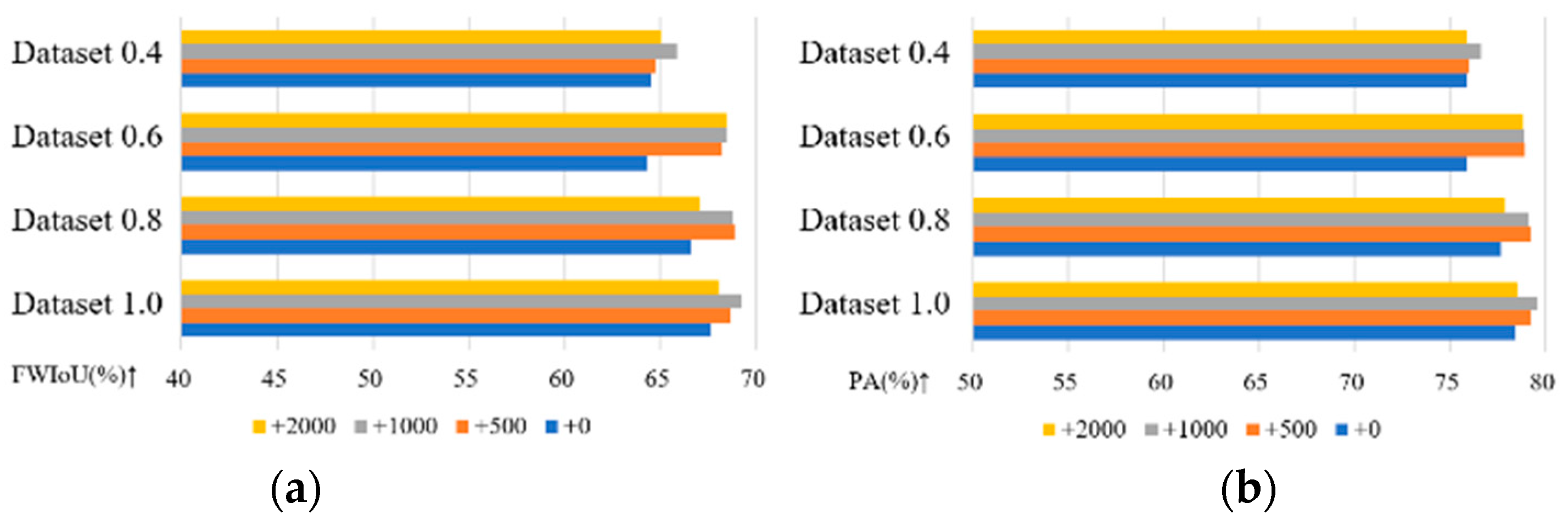

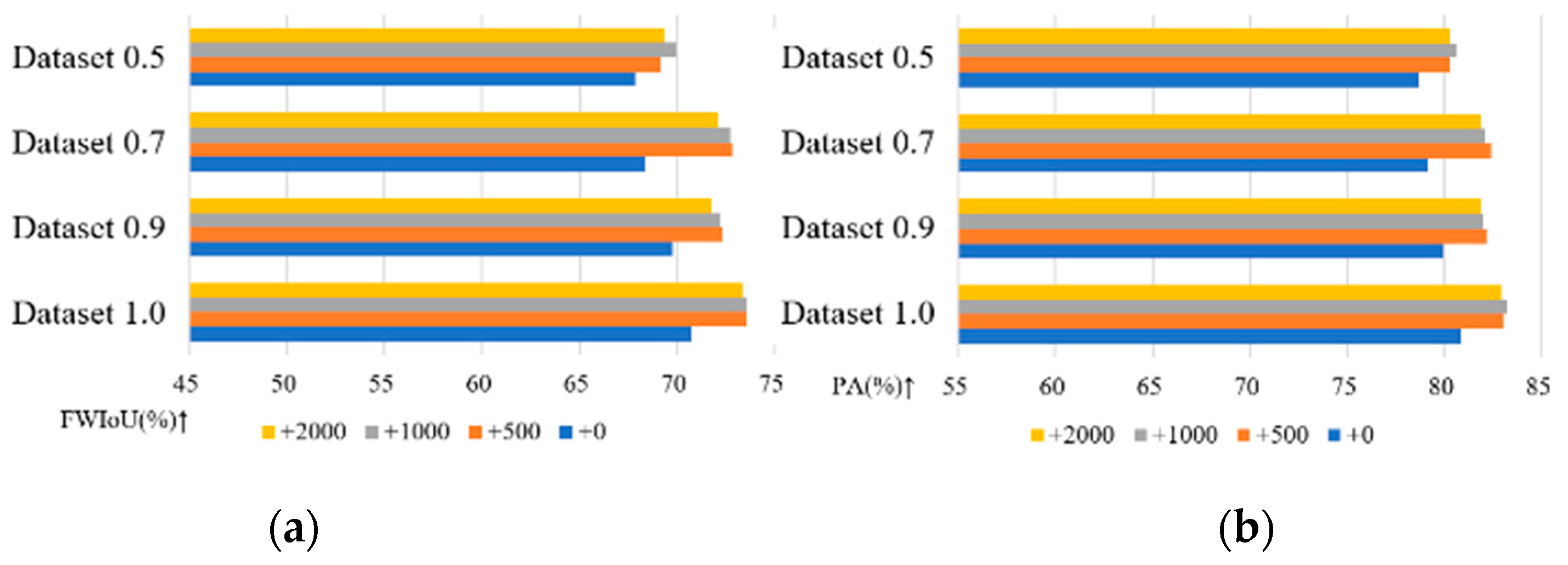

4. The effectiveness of the generated images is assessed by analyzing how varying quantities of generated data impact the accuracy of the U-Net segmentation network across datasets of different sizes.

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Dataset

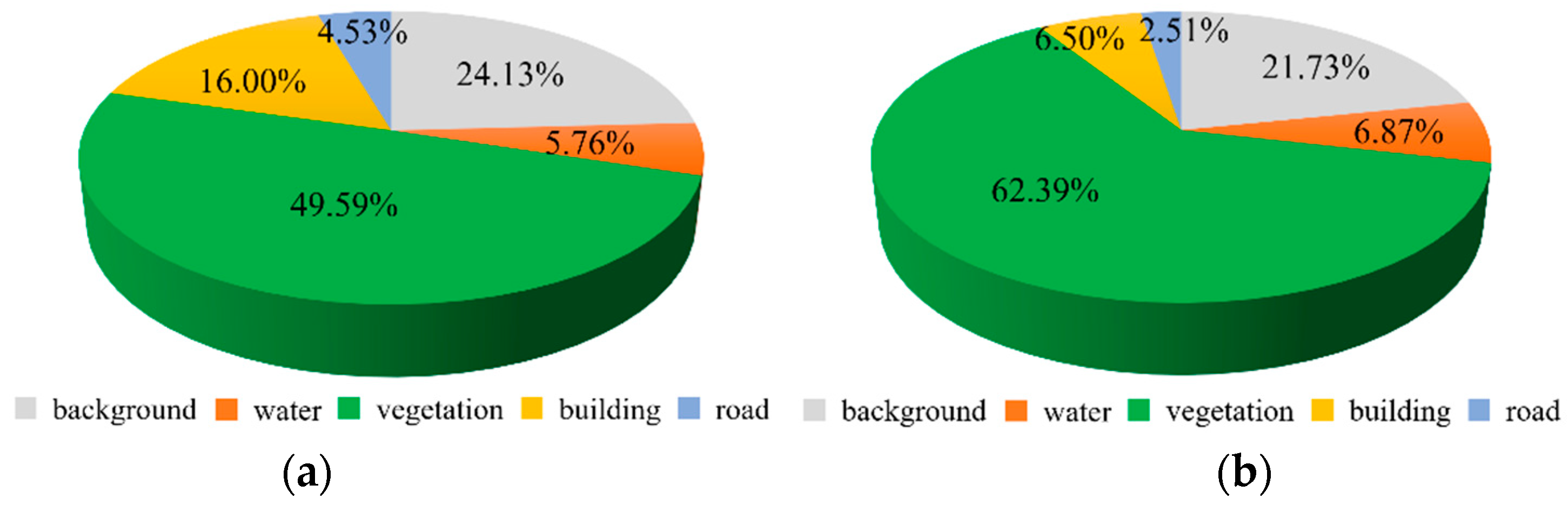

We utilize two remote sensing image datasets with distinct styles: the Chongzhou area in Sichuan Province of China, covering longitudes 103°37′ to 103°45′E and latitudes 30°35′ to 30°40′N, and the Wuzhen area in Zhejiang Province of China, covering longitudes 120°26′ to 120°33′E and latitudes 30°43′ to 30°47′N. The original images are satellite optical orthorectified images captured over two time periods, with each image measuring 5826×3884 pixels and a spatial resolution of 0.51 meters. The Chongzhou dataset features complex land characteristics, including large factories, intricate residential structures, rural clusters, agricultural fields with vegetation, and extensive rivers and highways. In contrast, the Wuzhen dataset primarily consists of water bodies surrounded by villages, with a landscape dominated by vegetation and rural buildings, and fewer factories and major highways.

In total, we focus on generating five typical remote sensing land features: background, water, vegetation, buildings, and roads. To facilitate this, we annotate the remote sensing data with the corresponding categories to create semantic labels. The images are cropped into smaller 512×512. Following cropping, both datasets are randomly divided into training and testing sets in a 4:1 ratio. The final Chongzhou dataset comprises 845 training samples and 211 testing samples, while the Wuzhen dataset contains 704 training samples and 176 testing samples.

Figure 4(a) and

Figure 4(b) illustrate the percentage of each feature in the Chongzhou and Wuzhen datasets, respectively, indicating a predominance of vegetation samples, while building, water, and road samples are less represented.

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

To assess the perceptual similarity between generated images and real images, we employ two representative metrics: Fre´chet Inception Distance (FID) [

41,

42] and Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) [

43], tailored to the characteristics of remote sensing images.

FID is used to measure the distribution differences between generated images and real images in feature space. The process begins by extracting features using the Inception network, followed by modeling the feature space with a Gaussian model, and finally calculating the distance between the two feature distributions. A lower FID indicates higher image quality and diversity. The formula is as follows:

where

,

,

, and

represent the mean and covariance matrices of the image features.

(·) represents the trace of a matrix.

LPIPS is a metric used to assess the perceptual similarity between images. Unlike traditional metrics such as PSNR and SSIM, which primarily focus on pixel-level differences, LPIPS aligns more closely with human visual perception. The formula is as follows:

where

denotes different layers in the network (e.g., convolutional layers),

and

are the feature maps of images

and

at layer l,

is the number of elements in the feature map at layer

, and

represents the L2 norm (Euclidean distance).

The ultimate goal of generating these images is to augment the dataset for deep learning tasks. To evaluate the quality of the generated images, we utilize a U-Net network trained on the Chongzhou and Wuzhen datasets for semantic segmentation. The model's accuracy is quantified using two metrics: Frequency-Weighted Intersection over Union (FWIoU) and Overall Accuracy (OA). If the generated images are highly realistic and closely resemble real images, a segmentation network trained on real images should accurately segment the generated outputs.

3.3. Implementation Details

We train and test the model using PyTorch on the Chongzhou and Wuzhen datasets, respectively, employing an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU as the training tool. For model training parameters, the batch size is set to 4, with a total of 200 iterations. The learning rate is initially set to 0.0002 for the first 100 iterations and decays linearly to 0 over the subsequent 100 iterations. The optimization algorithm used for network parameters is Adam.

3.4. Ablation Experiments

Ablation experiments are conducted to decompose the generator model and evaluate how various structures influence image quality. This approach allows us to verify the contribution of each functional module within the MTGAN generator to the enhancement of generated image quality.

Table 1.

The ablation experiment plan.

Table 1.

The ablation experiment plan.

| Model |

Description |

| Pix2Pix |

Baseline model |

| Pix2Pix++ |

and are added on Pix2Pix model |

| DBGAN |

Dual-branch generative model |

| DBGAN++ |

A shared parameter encoder is added on DBGAN |

| MTGAN |

A spatial decoder is added on DBGAN++ |

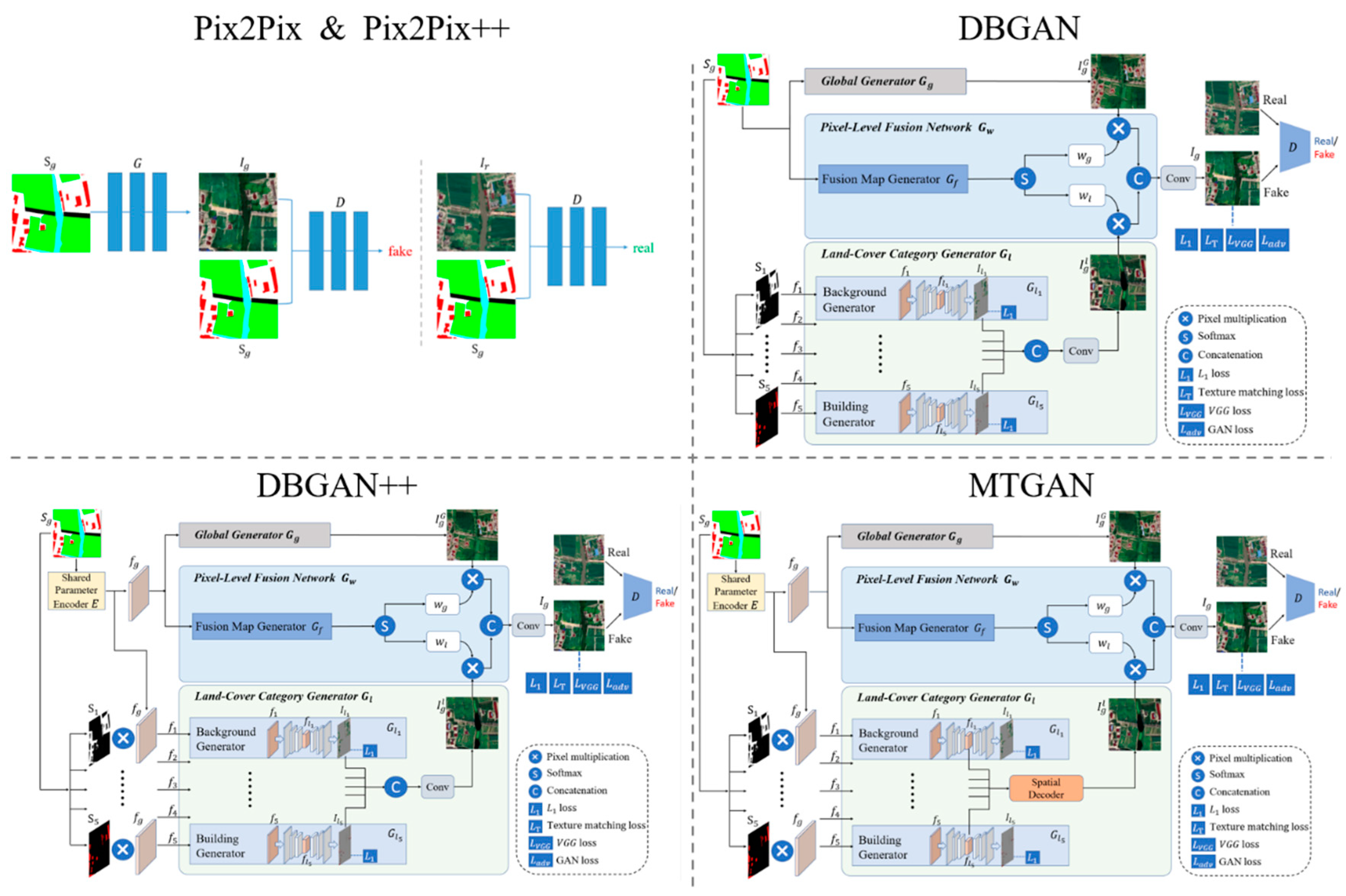

The ablation experiments are structured around five schemes: Pix2Pix serves as the baseline model. Pix2Pix++ incorporates perceptual loss and texture matching loss into Pix2Pix, resulting in the loss function . DBGAN employs Pix2Pix as the global generator and includes land-cover class generators for different features within the dual-branch generative model. DBGAN++ builds upon DBGAN by introducing the shared parameter encoder, thereby balancing the training process. MTGAN enhances the local generators by introducing the spatial decoder to form the final proposed model. In this context, the loss functions for DBGAN, DBGAN++, and MTGAN are all defined as .

Figure 5.

The schematic diagram of ablation experiment plan.

Figure 5.

The schematic diagram of ablation experiment plan.

Ablation experiments are conducted on the Chongzhou and Wuzhen datasets.

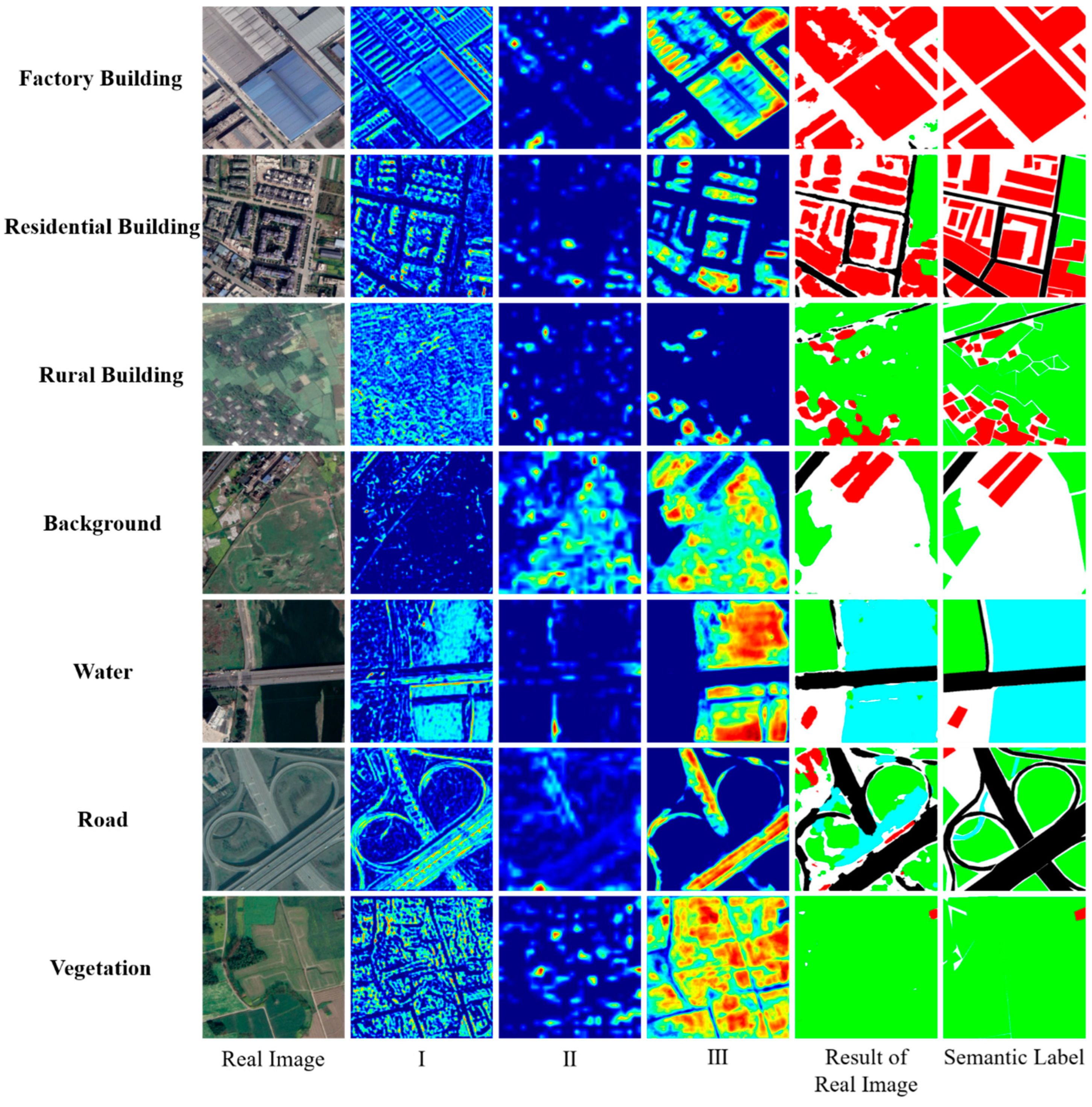

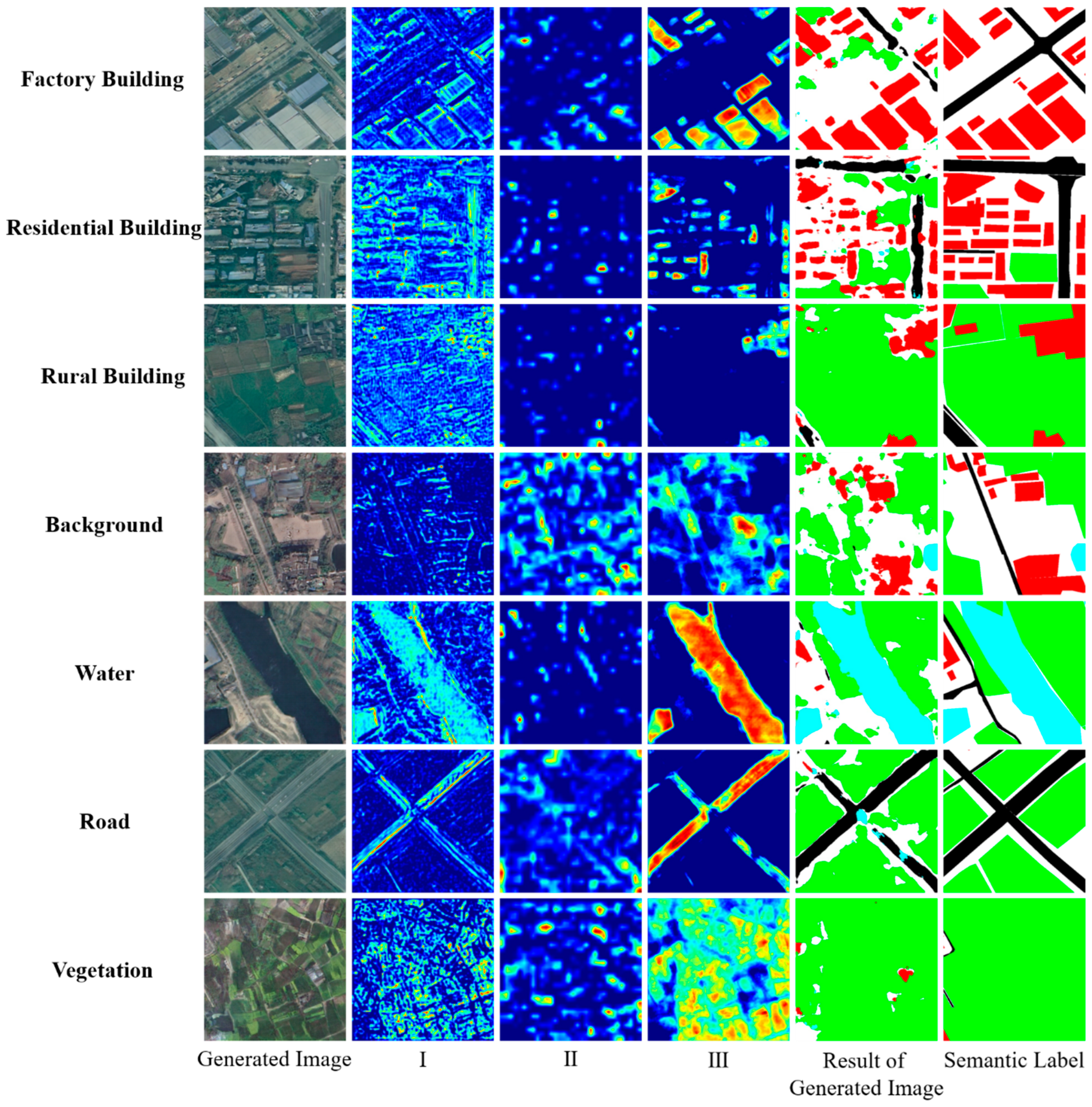

Table 2 presents the evaluation metrics for each program on the respective datasets.

Table 2 indicates that compared to the baseline model Pix2Pix, Pix2Pix++ shows significant improvements in the Chongzhou dataset, achieving a 3.61% increase in FWIoU, a 3.52% increase in OA, a 0.0072 increase in LPIPS, and a remarkable 17.05% improvement in FID. Similarly, for the Wuzhen dataset, FWIoU and OA increase by 2.12% and 1.39%, respectively, with LPIPS rising by 0.0183 and FID by 12.27.

Figure 7(c),

Figure 7(b), and

Figure 8(c) illustrate that the incorporation of VGG loss and texture matching loss effectively mitigates issues in water generation. Additionally, this enhancement improves the model's capacity to learn color textures, particularly evident in the extraction of urban building colors in the Wuzhen dataset.

When comparing the DBGAN model to Pix2Pix++ on the Chongzhou dataset, DBGAN demonstrates improvements with a 1.60% increase in FWIoU and a 1.67% increase in OA. However, LPIPS decreases by 0.0124, and FID decreases by 10.43.

Figure 7(d) and

Figure 7(c) visually illustrate that DBGAN produces architecture with clearer outlines compared to Pix2Pix++. Moreover, DBGAN's road generation results feature contours and textures that more closely resemble real road characteristics. On the Wuzhen dataset, DBGAN outperforms Pix2Pix++ with a 2.29% increase in FWIoU and a 1.63% increase in OA. Conversely, LPIPS decreases by 0.0186, and FID decreases by 23.72.

Figure 8(d) and

Figure 8(c) show that DBGAN enhances the generation of colors and contours for small-scale buildings in the Wuzhen dataset. The above illustrates that the use of a dual-branch structure, along with the introduction of class-specific generators, can effectively enhance the model’s ability to generate objects for underrepresented land cover classes

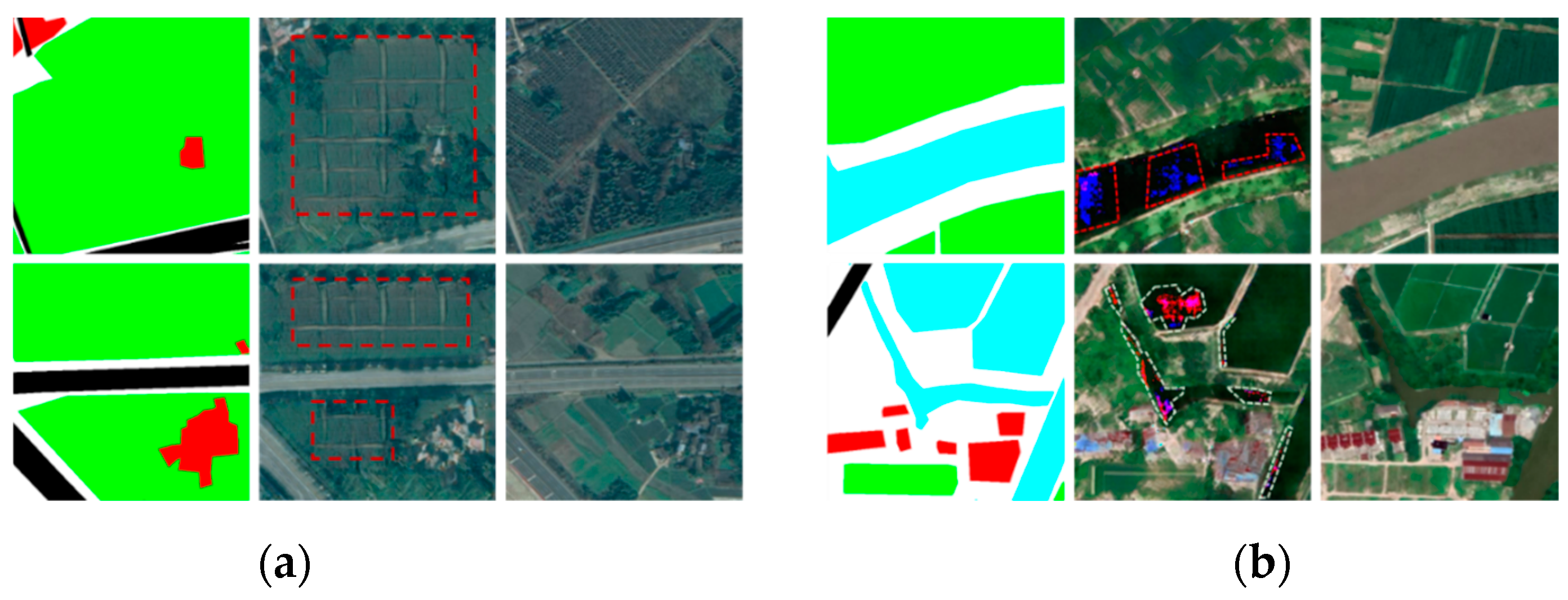

However, DBGAN exhibits certain shortcomings, as evidenced by the generated images depicted in

Figure 6. Specifically, the red dashed box in

Figure 6(a) highlights a texture replication issue in the Chongzhou generated image, while the white dashed box in

Figure 6(b) indicates the presence of noise in the Wuzhen generated image. These problems primarily arise from the challenges in maintaining a balance between the global generator and the land-cover class generator during the training process.

With the introduction of the shared parameter encoder, DBGAN++ successfully addresses the issues present in DBGAN. As indicated by the metrics in

Table 2, DBGAN++ shows improvements in LPIPS and FID by 0.0178 and 30.85 on the Chongzhou dataset, and by 0.0290 and 57.58 on the Wuzhen dataset, respectively. Visual comparisons in

Figure 7(d) and

Figure 8(d) demonstrate that DBGAN++ effectively mitigates the pattern collapse and noise issues found in DBGAN, resulting in images that closely resemble real ones. However, there is a slight decrease in FWIoU and OA metrics with the introduction of the shared parameter encoder. Specifically, on the Chongzhou dataset, FWIoU and OA decreased by 0.36% and 0.1%, while on the Wuzhen dataset, they decreased by 2% and 0.73%. This reduction can be attributed to the interference introduced during the convolution process of the shared parameter encoder, which complicates the class-specific generator's ability to generate specific categories.

MTGAN leverages the spatial decoder to balance the influences among the class-specific generators. This approach significantly enhances the performance of the land-cover class generator. As shown in

Table 2, MTGAN achieves the best metrics overall. On the Chongzhou dataset, compared to DBGAN++, MTGAN's FWIoU and OA increase by 5.29% and 6.3%, respectively; LPIPS increases by 0.0178; and FID improves by 30.85. When compared to the baseline model Pix2Pix, MTGAN demonstrates increases of 10.38% and 11.15% in FWIoU and OA, respectively; LPIPS increases by 0.0297; and FID improves by 52.86. On the Wuzhen dataset, MTGAN outperforms DBGAN++ with increases of 6.35% and 3.88% in FWIoU and OA, respectively; LPIPS increases by 0.0432; and FID improves by 41.26. Compared to the baseline model Pix2Pix, MTGAN shows increases of 8.76% and 6.17% in FWIoU and OA, respectively; LPIPS increases by 0.0719; and FID improves by 87.29.

Figure 7.

Figure 7. The ablation experiment on the Chongzhou dataset.

Figure 7.

Figure 7. The ablation experiment on the Chongzhou dataset.

Visually, MTGAN demonstrates significant enhancements in generating building outlines on the Chongzhou dataset. As illustrated in the first row of

Figure 7, the model produces more realistic representations of complex residential buildings, while the fourth row shows improved generation of factory buildings. Additionally, MTGAN effectively captures vegetation textures and rural buildings that closely resemble real remote sensing images, as seen in the fifth row of

Figure 7. The model also excels in generating roads and complex backgrounds, aligning better with the inherent characteristics of these features, highlighted in the second and third rows of

Figure 7.

In summary, the improvements provided by MTGAN not only ensure network stability but also enhance the generation of fine details across various land cover categories. This results in a higher quality of generated samples for underrepresented land cover classes. Moreover, MTGAN strengthens the depiction of complex features like building outlines, leading to samples that more closely match real remote sensing images.

On the Wuzhen dataset, MTGAN's superior understanding of global context enables it to generate diverse remote sensing images, reflecting both lush spring/summer scenes and darker autumn/winter tones based on the layout features of the semantic image.

Figure 8.

The ablation experiment on the Wuzhen dataset.

Figure 8.

The ablation experiment on the Wuzhen dataset.

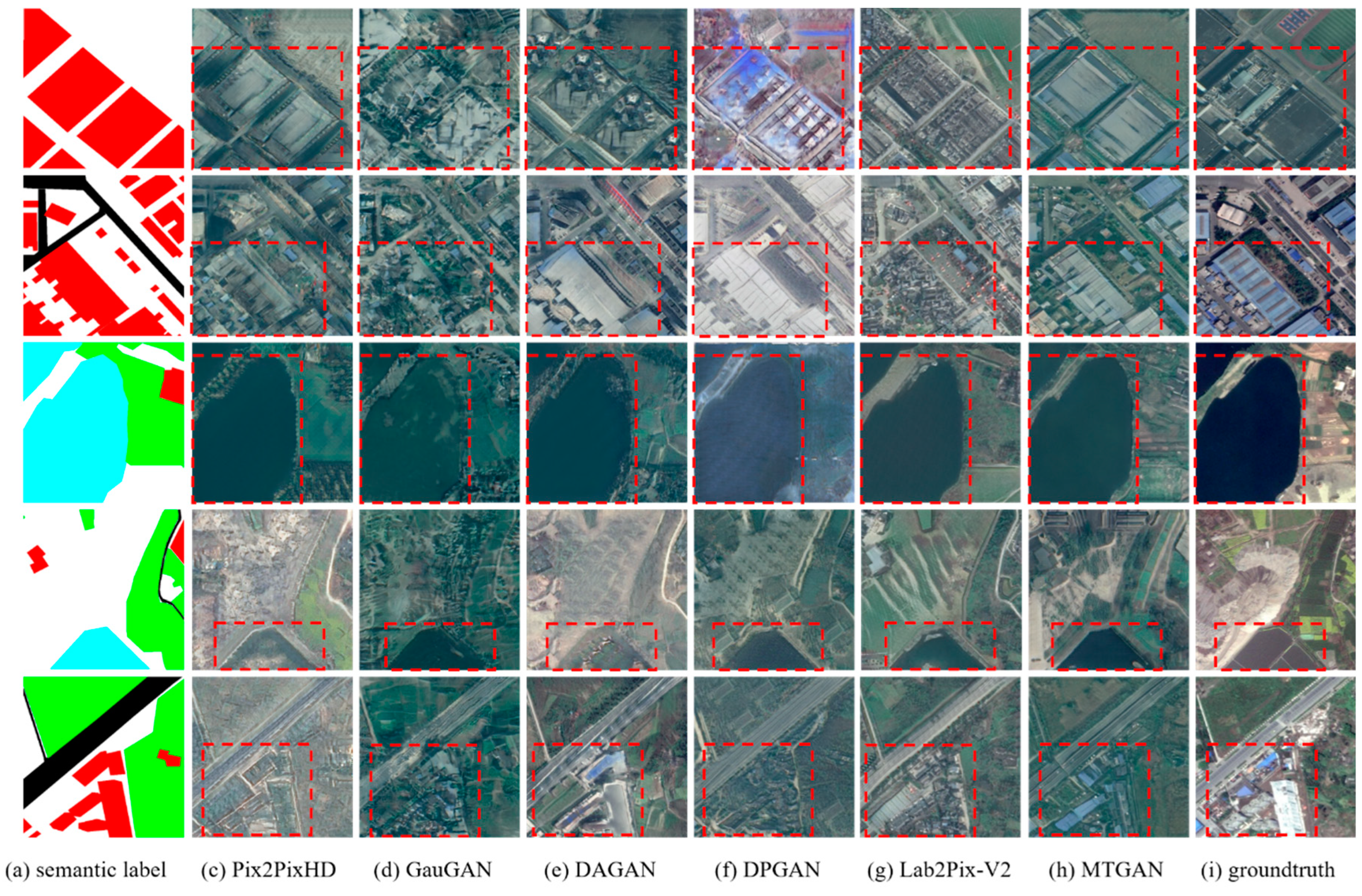

3.5. Comparison Experiments

In order to further verify the effectiveness of MTGAN model, we respectively compare Pix2Pix [

26], Pix2PixHD [

28], GauGAN [

29], DAGAN [

30], DPGAN [

31] and Lab2Pix-V2 [

44] on the dataset of Chongzhou and Wuzhen. The evaluation indexes of the experimental results are shown in

Table 3. To visualize the generating effect of different models, some of the experimental result images are given in this paper, as shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

The experimental results demonstrate that MTGAN achieves the highest accuracy on the Chongzhou dataset, with FWIoU and PA metrics consistently outperforming those of existing models. This suggests that MTGAN's generated images are more realistic and reliable, contributing to enhanced segmentation performance. Additionally, the FID and LPIPS scores for MTGAN-generated images show significant improvements, indicating that these images align more closely with real remote sensing data in both overall distribution and individual characteristics.

As shown in

Figure 10, MTGAN produces images with clearer, more defined contours compared to other models, and maintains greater consistency in intra-class information for the same semantic label. Furthermore, MTGAN excels in generating realistic textures for less common features, such as water bodies and roads. In terms of background and vegetation, MTGAN offers richer color and texture details, resulting in generated images that are both more realistic and trustworthy.

For the Wuzhen dataset,

Table 3 indicates that MTGAN-generated images significantly surpass existing methods across various metrics. The FID and LPIPS scores reveal that MTGAN images closely mimic real data in style and distribution. Moreover, the superior FWIoU and ACC metrics suggest that the generated images offer more relevant information for the U-Net segmentation network. MTGAN's advantage lies in its ability to produce vegetation with rich color and texture details, while also excelling in generating features with smaller sample sizes, such as buildings (6.50% of the sample) and roads (2.51% of the sample).

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-based model to enhance semantic segmentation of remote sensing images by addressing the need for diverse samples. We tackle key challenges in existing models, such as insufficient texture details for underrepresented land cover classes and the presence of unrealistic textures within certain land cover types. Our approach focuses on two main aspects:

We design MTGAN to generate remote sensing images from semantic labels. The model features a dual-branch architecture, with a global generator capturing the overall image structure and land cover class-specific generators improving the quality and differentiation of land cover types. We evaluate the image generation quality on the Chongzhou and Wuzhen datasets, where our model outperforms others in terms of both FID and LPIPS scores.

We train both MTGAN and U-Net on datasets of varying sizes from Chongzhou and Wuzhen. Adding generated samples to the original datasets significantly boosts U-Net performance. For instance, on the Chongzhou dataset, adding 500 generated samples to a training set of around 500 images improves FWIoU and OA by 3.89% and 3.07%, respectively. Similarly, on the Wuzhen dataset, this addition results in improvements of 4.47% and 3.23%.

In summary, in the task of generating remote sensing images through semantic image synthesis based on GANs, we have made various targeted improvements to the generative model, yielding promising research outcomes. However, there is still room for improvement in this paper. The generative model presented is a supervised one-to-one generation mode, where one semantic label generates one style of image. One of the future research directions is to construct a multimodal remote sensing image generation network that enables a single semantic label to generate multiple styles of images.