1. Introduction

Historically, the existence of a discrete brotherhood between metal−organic framework (MOF), and the supramolecular architecture based on metal−organic polyhedron (MOP). In fact, microporosity is an important asset in supramolecular hybrid metal−organic cages also called porous coordination cages (PCCs). In this sense, characteristic crystalline phase of the MOPs depends on the nature of the cage as much as the conditions from which it is crystallization [

1]. It is eloquent that in pore technology, peptide-based nanopores are also exploited with potential application in molecular detection [

2].

Rapid advances associated to design and synthesis of polyhedra using molecules and metals through coordination-driven self-assembly have been significative including by the introduction of new strategies of synthesis. When polyhedral structures are design employing inorganic and organic building blocks, becoming metal-organic polyhedra (MOPs), the vertices are either polytopic inorganic or organic nodes, and the edges are the linkers between the inorganic nodes and between inorganic and organic nodes. Spatially, the polyhedral structures must be built from at least one of the blocks forming a bent or curved, this obviously implies a good design of a supramolecular polymerization reaction [

3].

MOPs, have been defined as discrete molecules self-assembled from organic linkers and metal clusters and they are recognized for having tiny porous units. An instructive viewpoint, metal–organic materials can be categorized into four distinct configurations: uniform structures, heterostructures, hierarchical structures, and structures with gradient.

The giant metal-containing molecules was considered by Virovest et al., [

4] sizing such studies there are two relevant classes a giant cluster with a compact core surrounded by ligands; and spacer-based supramolecules that comprise metal cations or polynuclear metal complexes (nodes) connected to each other by organic ligands that is the spacers. To a giant hollow structure for instance [Pd

30(L

1)

60]

60+, it is often referred to as coordination cage, metal−organic cage (MOC) or metal−organic polyhedron (MOP) [

4].

The growing concern made in a study 2016, it is precisely highlighted that the metal atoms in the central core can have different cohesive energies depending on the elements, the nature of the outer ligands, and the surface energy. The overall conclusion was that the interrelations of different kernel, chemical transformations of one kernel into another as well as an interplay between a kernel and the set of frequently occurring numbers of the metal atoms in the kernel (so-called magic numbers or magic series 12,115,116) are the important aspects of the chemistry of giant metal clusters. For instance, for the Au/TBBT (TBBT = 4-tertbutylbenzenethiolate) arrangement, the magic series includes clusters of the general formula Au

8n+4(TBBT)

4n+8, where n = 3-6 [

5].

One if the pioneering works on polyhedral structures presents three possibilities in the process called truncation for square units, namely, the truncated octahedron with 6 squares, the truncated cuboctahedron with 12 squares, and the truncated icosidodecahedron with 30 squares [

6].

It is now reasonably certain that a careful selection of ligands and metal centers gives rise to varied geometrical convex or nonconvex polyhedral shapes of solids. Interesting comments are described by El-Sayed and Yuan about convex polyhedra, they carry out a discussion about the formation of polyhedral MOPs with specific and detailed geometric architecture such as regular polyhedra that form platonic MOPs and semi-regular polyhedrons that favor the formation of Archimedean MOPs, these two types of polyhedra are formed by edge-sharing of their polygons. A significant example is the formation of supramolecular coordination structures using metal mediated self-assembly and calixarenes units. Just by combining linear di or tricarboxylate or azole ligands with metal-calixarene units, this gives rise to multicomponent hollow MOC structures of adaptable shapes with distinctive features [

7]. In a particularly influential paper by Su and coworkers are detailed the symmetrical elements and inversion center and plane existing in polyhedra, properties that have been quite a challenge obtain chiral MOCs with various configurations. The stereogenic centers in polyhedral MOCs can be included either in the vertices, edges or faces of the cage entities previously to the coordination self-assembly process, or alternatively, formed in-situ because of the spatial arrangement or twisting configuration of either metal centers or organic ligands [

8].

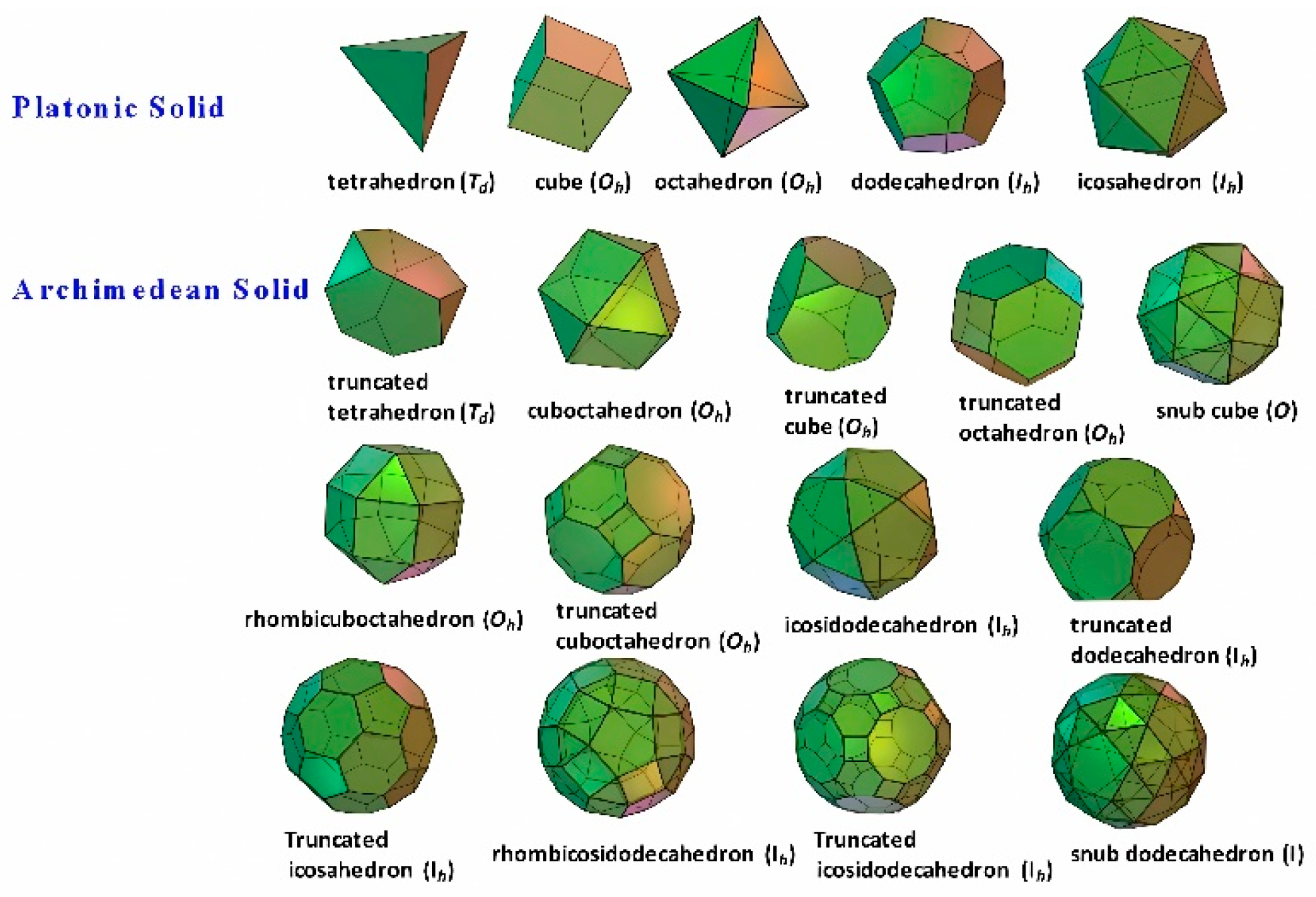

There are only five kinds of Platonic solids, namely tetrahedron, cube (hexahedron), octahedron, dodecahedron, and icosahedron. Regular polyhedron has high symmetry group, comprising multiple symmetrical axes, mirror planes (and inversion center). Besides, there are all together thirteen types of Archimedean solids, most with

Td,

Oh or

Ih symmetry groups, except that snub cube and snub dodecahedron are in O and I symmetry groups, respectively, as shown in

Figure 1.

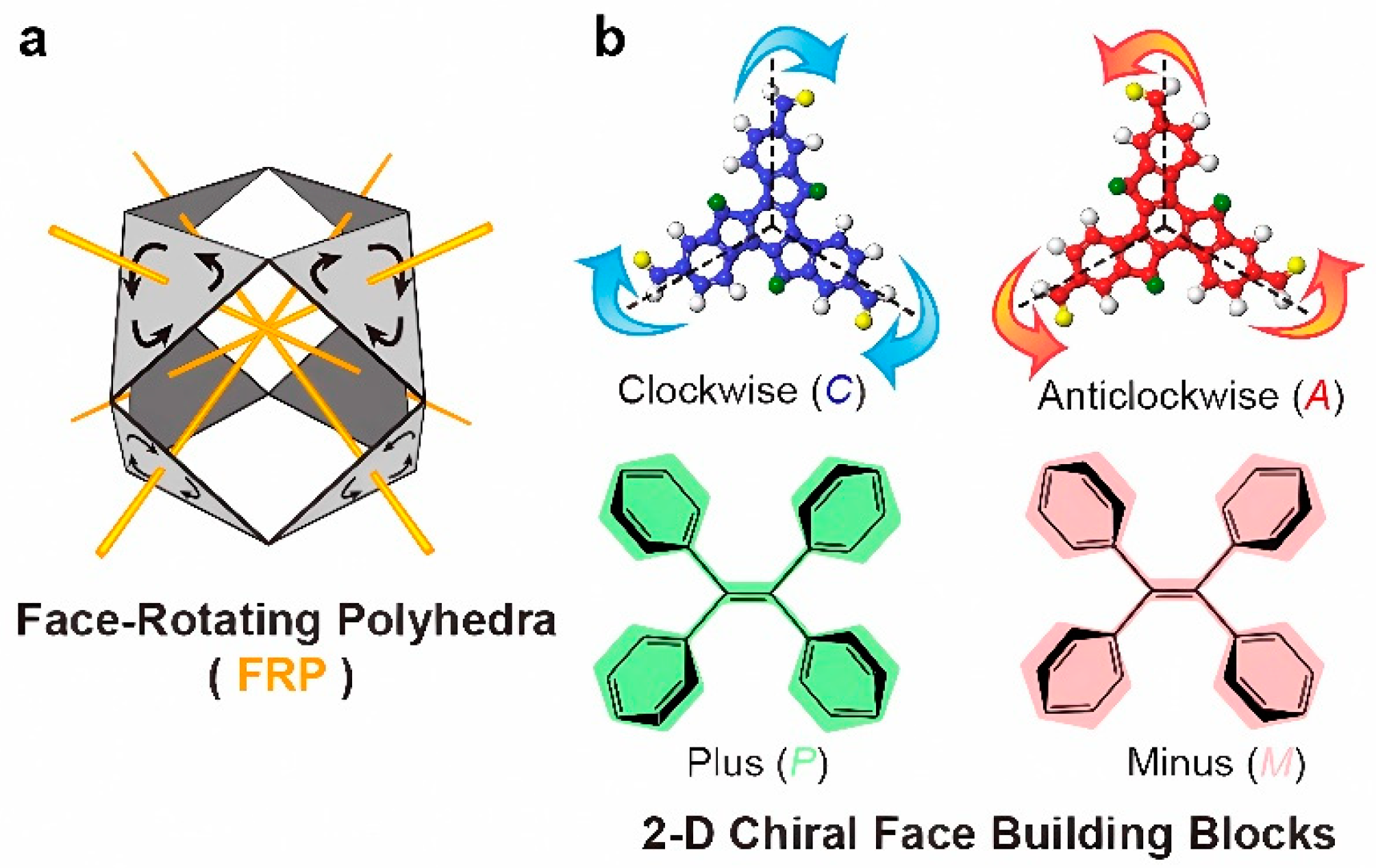

The value of a library of structurally symmetric compounds in the study of the effect of geometry, size, periphery, is self-evident. This approach is also taken of mathematical concept of face-rotating polyhedra (FRP) heralds a fascinating category of chiral objects. Further, in FRP, each face rotates around its central axis, giving rise to distinct facial rotational patterns while maintaining the core polyhedral shape [

9], as shown in

Figure 2. A systematic variation of the symmetry becomes possible by a design process, which, in a formal sense includes octahedral geometry with different stereoisomeric rotation patterns.

A major obstacle to designing FRP is identifying the molecular blocks that may have specific rotation controls. Regarding the mathematical concept into molecular architecture will be the foundation for significative class of chiral molecular polyhedra. The rapid progress made over the time in developing novel MOPs, this distinction is revealed by the assembly of the compound [Rh

2(bdc-C

12)

2]

12 (C

12RhMOP; bdc-C

12 = 5-dodecoxybenzene-1,3-dicarboxylate) with the ditopic linker, 1,4-bis(imidazole-1-ylmethyl)benzene (bix) [

10].

An alternative to the permanent porosity of polyhedral organometallic structures has been published by Yagui and his team of collaborators. They reported the schematic synthesis of both MOP-100 and MOP-101 (so named by the authors) structured with Pd

II resulting into rhombic dodecahedra, moreover stablished that the compounds presented high chemical stability in acid and basic environments [

11]. The MOP-100 was assembled with hydrogen tetrakis(1-imidazolyl)borate (HBIm

4) and the MOP-101 was assembled with hydrogen tetrakis(4-methyl-1-imidazolyl)borate (HB(4-mIm)

4). A particular is the case where a pre-assembled complex of the cuboctahedral MOP used as a possible template to replicate caged structure having a ‘‘triblock Janus-type’’ configuration both heterometallic and heteroleptic. This easily be visualized by considering a strategy to form the archetypical cuboctahedral Cu

24bdc

24 or Rh

24bdc

24 MOP (here bdc is the compound 1,3-benzenedicarboxylic acid) where the triblock Janus-type configuration is conceived [

12].

To generate heteroleptic coordination cages with potential application in guest recognition, chemical sensing, and catalysis, the chirality is a significant factor. The structural assessment by NMR methods and single-crystal X-ray diffraction is essential, and it is necessary to considered that during the synthesis a metal precursor and the ligand are dissolved and heated until the desired cages have assembled, favoring the formation of more thermodynamically stable products [

13].

Notably, a wealth of applications has been reported by Cook and Morrow and their colleagues on the variations of molecular geometry of geometrical criteria of MOPs chemically constituted with rigid catecholamide linkers for a M

4L

6 MOP utilizing multiple Fe

III centers [

14]. This all relies on the idea that the essential factor is the stabilization and its manifestation. The intrinsic nature of self-assembly is kinetically inert in the presence of Zn

II cations and EDTA for up to 24 h, dissimilarity to simple catechol complexes of Fe

III whatever rapidly decomposes under such conditions. An additional advantage is that structures are available for binds strongly to serum albumin that has an impact on in vivo pharmacokinetic properties observed in mouse models and in the increases observed with T

1 relaxivity.

2. Structural Criteria of MOPs

If we think of structural criteria for the coordination driven self-assembly as a powerful method to perform from supramolecular complexes to MOPs, the design needs the combination of both “donor” organic bridging ligands with suitable “acceptor” metal ions or discrete metal-oxo clusters in the corners to yield a variety of architectures. Encouraged by the success of all possible configurational isomers of metal−organic polyhedron-based structures using the Bi

6Fe

13L

12 cluster as a model, Kandasamy eta al., show that ligand variation plays a leading role during the assembly process on the designing of a system based on Bi

6Fe

13L

12 [

15]. If we think of structural criteria for the coordination driven self-assembly as a powerful method to perform from supramolecular complexes to MOPs, the design needs the combination of both “donor” organic bridging ligands with suitable “acceptor” metal ions or discrete metal-oxo clusters in the corners to yield a variety of architectures. In a way, the supramolecular aggregation of the cationic {Bi

6Fe

13L

12}-type clusters favors the impact on the pKa.

One of the most fundamental and earliest criteria of MOFs and their active sites is the structural rigidity and interchannel connectivity, what does not happen with the MOPs that present random aggregation or reorganization during solvent removal due of any strong supramolecular interaction between neighboring cages restricting the diffusion of sorbates through the MOPs [

16]. The bonding existing in MOF- and MOP-based supramolecular frameworks is remarkably maintained when diverse porosities are anchored. Such pore diversity can be observed into tetrahedral pores of UiO-66 replicable in a discrete MOP. Specifically, an extended supramolecular framework of the UiO-66 type contains pores similar to those present in amine-functionalized ZrMOP [

17].

We must be consistently cautious and circumspect and to be always carefully and deliberately avoided describing to the molecules as synthetic strategies in the hydrolytic stability of MOPs made up of carboxylates, invariably preferring instead to refer to them as supramolecular building blocks (SBBs) as an efficient route to restrict any aggregation of MOPs in the solid state after guest removal. In fact, as Ghosh and his colleagues point out explicitly that MOPs are separated from each other by strong coordination bonds that resist any reorientation of the MOPs upon guest removal [

16].

A related rigorous approach was taken by Lai eta al., who sought a method based on the logarithmic kinetics of the surface ligands exchange on MOP surface. This is an extremely important information since it is connected to polymer/polymer interaction observable within a plausible time scale. In this point, the authors specify the preparation of functionalized 24-arm MOP-based miktoarm star polymers (MSPs, also known as

μ-star polymers) where temperature is a decisive factor [

18]. The behavior towards a new vision founded by Kondinski eta al., involves the development of new concepts not only chemical but also of a geometric nature. This, through the representation of a chemical building unit (CBU) and another geometric building unit (GBU), the latter is the basis in the construction of MOPs assembly models formulated through complementary CBUs linked to the initial GBU [

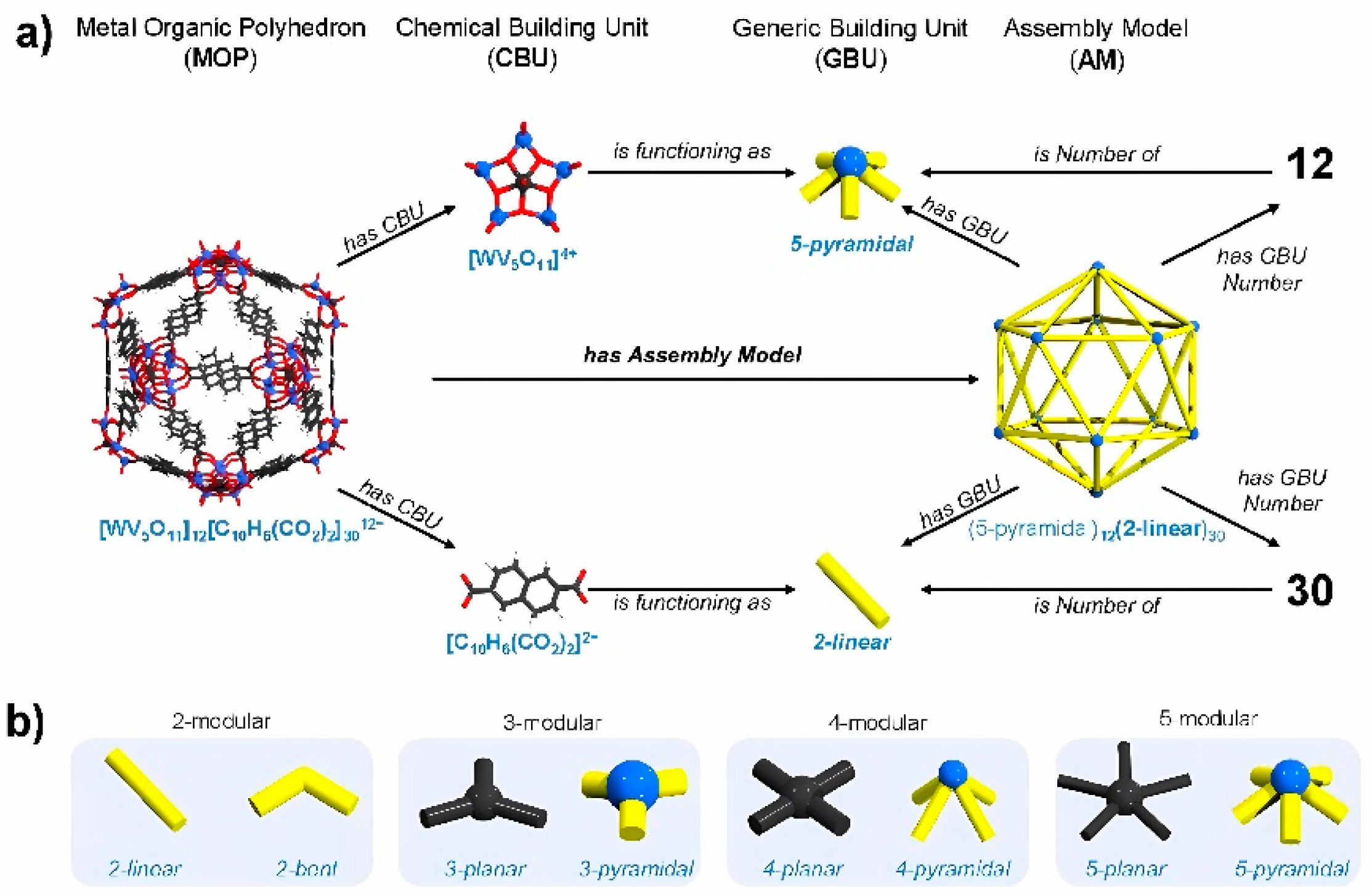

19], how well it can be seen in

Figure 3.

In the meantime, a colossal amount of evidence has created a very strong cause and effect link between π-delocalization and geometry, with a lot of emphasis on the preference of the π-electron energy. This is categorized in the study of three MOPs and their respective specific geometry such as Zr-based MOPs with four [Cp

3Zr

3(

μ3-O)(

μ2-OH)

3]

4+ metal nodes formed by the hydrolysis of zirconocene dichloride and six 1,4-benzenedicarboxylate linkers that bring about a tetrahedral geometry; the MOPs thar are based on Cu formed with twelve Cu‒Cu paddlewheel nodes at the vertices bridged by 1,3-benzenedicarboxylate linkers which result a truncated-cuboctahedral geometry; finally, the geometry of the MOP formed by six Pd

2+ nodes at the vertices linked by four 2,4,6-tris(4-pyridyl)-1,3,5-triazine (TPT) ligands on the faces, present a truncated tetrahedral, it is worth mentioning that the sites of coordination of Pd metal centers in this MOP are capped by 2,2′-bipyridine groups to give a discrete structure instead of an extended framework [

17]. Following the structural bases, the studies conducted by Kwon and Choe, the structuring of the MOP-1-R ([(Cp

3Zr

3O(OH)

3)

4(BDC-R)

6]Cl

6[(CH

3)

2NH

2]

2, Cp = h

5-C

5H

5, H

2BDC = benzene-1,4-dicarboxylic acid, R = CH

3, OH, and Br) with the construction of forming blocks comprise four Zr clusters and six BDC-R linkers at the vertices and edges of the tetrahedral cages [

20].

In the same perspective, Ma and his team of collaborators present the synthesis of a bifunctional discrete metal-organic cuboctahedron, namely Cu-MOP, from copper acetate and 2,6-dimethylpyridine-3,5-dicarboxylic acid, with Lewis acidic and basic functional centers. Cu-MOP has effective catalytic properties in Knoevenagel deacetylation and Henry deacetylation reactions [

21].

A designed material with the property of retaining porosity after melting and cooling cycles has been specified by Baeckmann et al., who also report that such a porous material, i.e. an Rh

II-based octahedral form, was functionalized with polyethylene glycol. Such a material, once melted, is very likely to be the vehicle for dispersing other materials and even molecules in order to design mixed matrix composites [

22].

A less often used criterion is based on the thermodynamic behavior of structures that have minimal or no empty spaces, emerging metastable products if the reaction is under strictly kinetic considerations. This is particularly true even if we also take into consideration structural and functional compatibility among the building blocks are positioned appropriately to each other [

21]. As Sullivan et al. has suggested in the isolate phase-pure of material [ZrMOP-biphenyl]OTf

X, that, in particular the tetrahedral structure [tetZrMOP-biphenyl]OTf

4 was isolated in just 20 min, and the so-called lantern structure was isolated in a reaction time greater than 30 min, in addition the solvent factor is undoubtedly a decisive factor for self-assembly [

23].

3. MOC Synthesis Criteria

The particular interest distinguishing an efficient strategy for the research non-classical polyhedra cages with captivating architectures for molecular recognition and separation, sensing, and supramolecular catalysis, is the inspiration of advanced tailoring forms [

24]. This assumption pose certain convergence with symmetry of macromolecular structures and their properties can help deliver key insights to several modern fields such as those related to biomolecules, and molecular electronic giving valuable insights in high-yielding coordination-chemistry-based that allow to tailor the size, shape, and properties of the resulting architectures [

25]. An important mention in this area was made by Hosono and Kitagawa, who recognized that structural relationship about highly symmetrical shape of MOPs and the geometrical positioning of the metal ions and ligands make them suitable building blocks to fabricate MOPs-core macromolecules as discrete porous modules [

26]. The skeletal bonding topology in electron-rich polyhedra give rise to the porous coordination cages also known as MOPs with intrinsic pores are a subclass of supramolecular cages that can be constructed by a modular approach from metal cations and organic linkers [

27].

A comprehensive method to generate a porous MOC liquid by incorporating PEGimidazolium chains into the periphery of the MOC was specified by He et al. As coulombic repulsion can keep the chains positively charged cavities they were terminated by positive imidazolium moieties. PEG-imidazolium chains were integrated into a p-tert-butylsulfonylcalix[

4]arene-based MOC to form a porous liquid Im-PL-Cage, which was self-assembled by the ionic ligand PEG-imidazolium 1,3-benzenedicarboxylic acid (PEG-Im-H

2BDC), Zn(NO

3)

2·6H

2O and a p-tert-butyl-sulfonylcalix[

4]arene (H

4TBSC) via coordination bonds. The long PEG chains can not only shield guaranteeing the accessibility of the host cavities but also could lower the melting point of the Im-PL-Cage and cause it to behave as a liquid [

28].

The self-assembly of a spherical structure that is composed of 30 palladium ions and 60 bent ligands, consists of a combination of 8 triangles and 24 squares, has a symmetrical pattern similar to tetravalent Goldberg polyhedron. We must not forget that Platonic and Archimedean solids have been prepared through self-assembly, as have trivalent Goldberg polyhedra, which occur naturally in the form of virus capsids and fullerenes. Using graph theory to predict the self-assembly of even larger tetravalent Goldberg polyhedra, perhaps more stable, will enable polyhedron family to be assembled from 144 components, namely, 48 palladium ions and 96 bent ligands [

29].

The octahedral (M

2)

6L

12-based MOPs structure was first constructed from a Cu

2 paddlewheel and 2,2′:5′,2″-terthiophene-5,5″-dicarboxylate, and was explored by bridging various metal paddlewheel clusters with the 9

H-carbazole-3,6-dicarboxylate linker [

30]. Another observation by Hirscher and Cooper and collaborators was the protection-deprotection strategy to produce cages where five out of the six internal reaction sites in the cage cavity were functionalized by means of formaldehyde. The combination of small-pore and large-pore cages together in a single solid produces an optimal material for the separation of deuterium and hydrogen with a selectivity of 8.0 with a high deuterium uptake of 4.7 millimoles per gram [

31].

It remains a challenge to advance in the field of the synthesis of discrete molecular cages with distorted structures by the self-assembly of asymmetric building units is challenging. The potential of each chemical factor and physical parameter is key in the formation of cages is key in the formation of cages, and the lability of the metal ion used is decisive; in conclusion, the reaction temperature is relevant. For instance, cages formed with Pt

II require more temperature than cages obtained from Pd

II, or cages formed with Rh

II require more temperature than cages obtained from Cu

II. Sometimes, as appropriate, coordinative solvents are used to favor the reversibility of the formed coordination bonds [

32].

In an example illustrated by Banerjee et al., a class of compound involving functionalized benzothiadiazole units twisted di-terpyridine ligand L with 4-pyridyl donor sites is structurally dimensioned. With the possible self-assembly using a Pd

II acceptor (A), L assumes a trans orientation of its terpyridine units to generate a distorted trigonal Pd

6 cage. Ligand L was synthesized following Krönhke pyridine synthesis by the reaction of 3,3’-(benzo[c][

1,

2,

5]-thiadiazole-4,7-diyl)dibenzaldehyde (P) with KOH, 4-acetylpyridine and NH

3(aq.) in ethanol. The final cage was synthesized via the self-assembly reaction between L and cis-[(tmeda)Pd(ONO

2)

2] (A) in 1:2 molar ratio in DMSO at 70°C for 48 h (tmeda =

N,

N,

N’,

N’-tetramethylethane-1,2-diamine; DMSO = dimethyl sulfoxide) [

33].

There are other cases in organic synthesis of some MOCs using o-phenanthroline and its derivatives to generate functional organic ligands to form metal-organic materials with favorable properties in fluorescence detection. Since o-phenanthroline has coordination properties with transition metals, the compound 3,3′-[(1E,1′E)-(1,10-phenanthroline-2,9-diyl)bis(ethene-2,1-diyl)]-dibenzoic acid and cadmium salts was structured exhibiting a trefoil-shaped form. The structural congruence obtained was evaluated by single-crystal X-ray crystallography and intramolecular hydrogen bonding studies [

34]. Craig et al., described an alternative containing a bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-7-ene-2,3,5,6-tetracarboxydiimide unit for assembling lantern-type metal-organic cages with the general formula [Cu

4L

4] [

35].

Research has even been carried out that takes advantage of the expansion of some MOCs designed with L dicarboxylates with a rigid aromatic skeleton, in which the two benzene rings of the stilbene moiety are connected by a hexaethylene glycol chain at the 2,2’ positions. The relevance of these materials is expanded by using Rh

II to structurally dimension a conformation of paddlewheel cage with great stability and versatility [

36].

In another instance, from investigation directed by Furukawa, analysis of the reaction mechanism of the MOPs with imidazole-based linkers disclosed the polymerization to consist of three separate stages, namely, nucleation, elongation, and cross-linking. The authors use supramolecular polymerization to drive the monomeric succession of MOP monomers [

37]. A summary of the history, dynamics, and complexity of the conformation of MnL

2n cages is described by Judge et al. In the meantime, progress is also substantial in exploiting self-assembled MOCs as drug carriers. Besides, a central point is given to the methods of integrating MOCs in polymers, leading to the synthesis of colloidal nanoparticles-micelles and vesicles that possess combined properties and extended system tunabilities [

38].

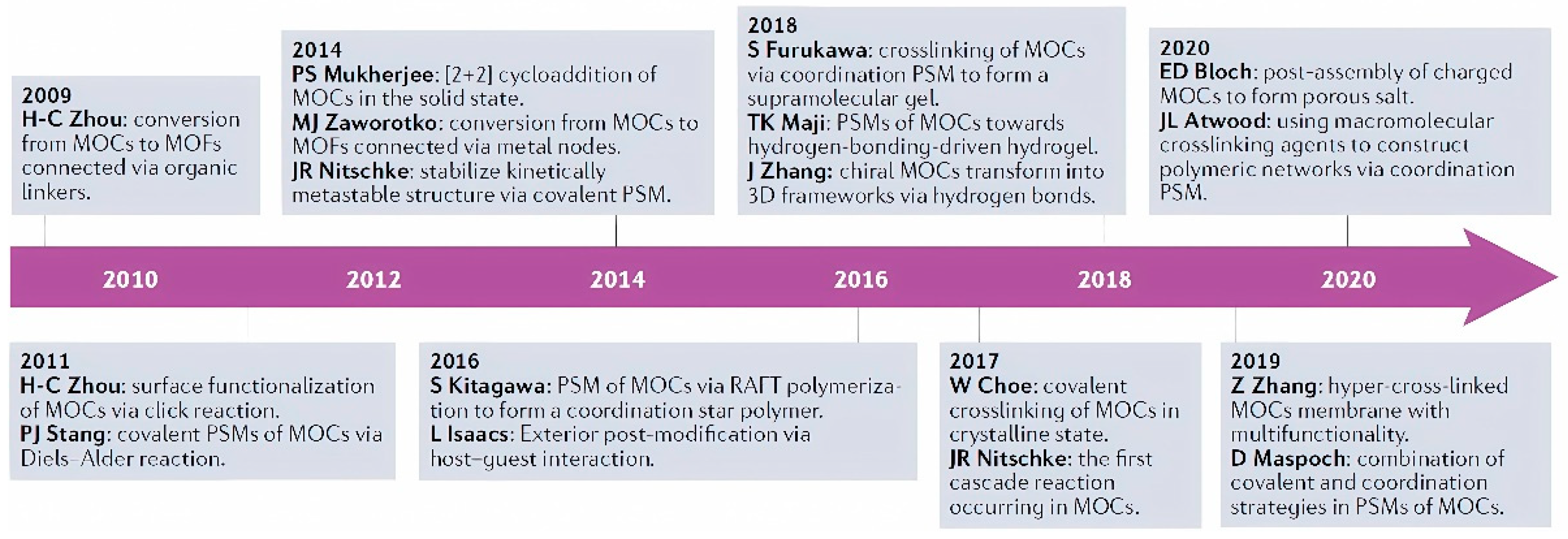

4. Structural Post-Modification of MOCs

In a comprehensive work published in 2021 by Martín Díaz and Lewis is quoted the complexity of MOCs over thirty years [

39]. With the introduction of new ideas in this regard [

13], both heteroleptic assemblies and low symmetry [

40] assemblies towards the development of more sophisticated host systems are faltering more commonplace. The combination of the above together with the great improvement in Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) and the advancement of computational power for theoretical investigations allow researchers to gain and in-depth analysis of these systems.

Optimized geometries supramolecular binding of guests via an endohedral functionalization is an attractive alternative in employing a covalent linker as endohedral group. A representative case is the linker dependence for the electron transfer of redox-active species encapsulated in M

6L

12 and M

12L

24 supramolecular cages [

41].

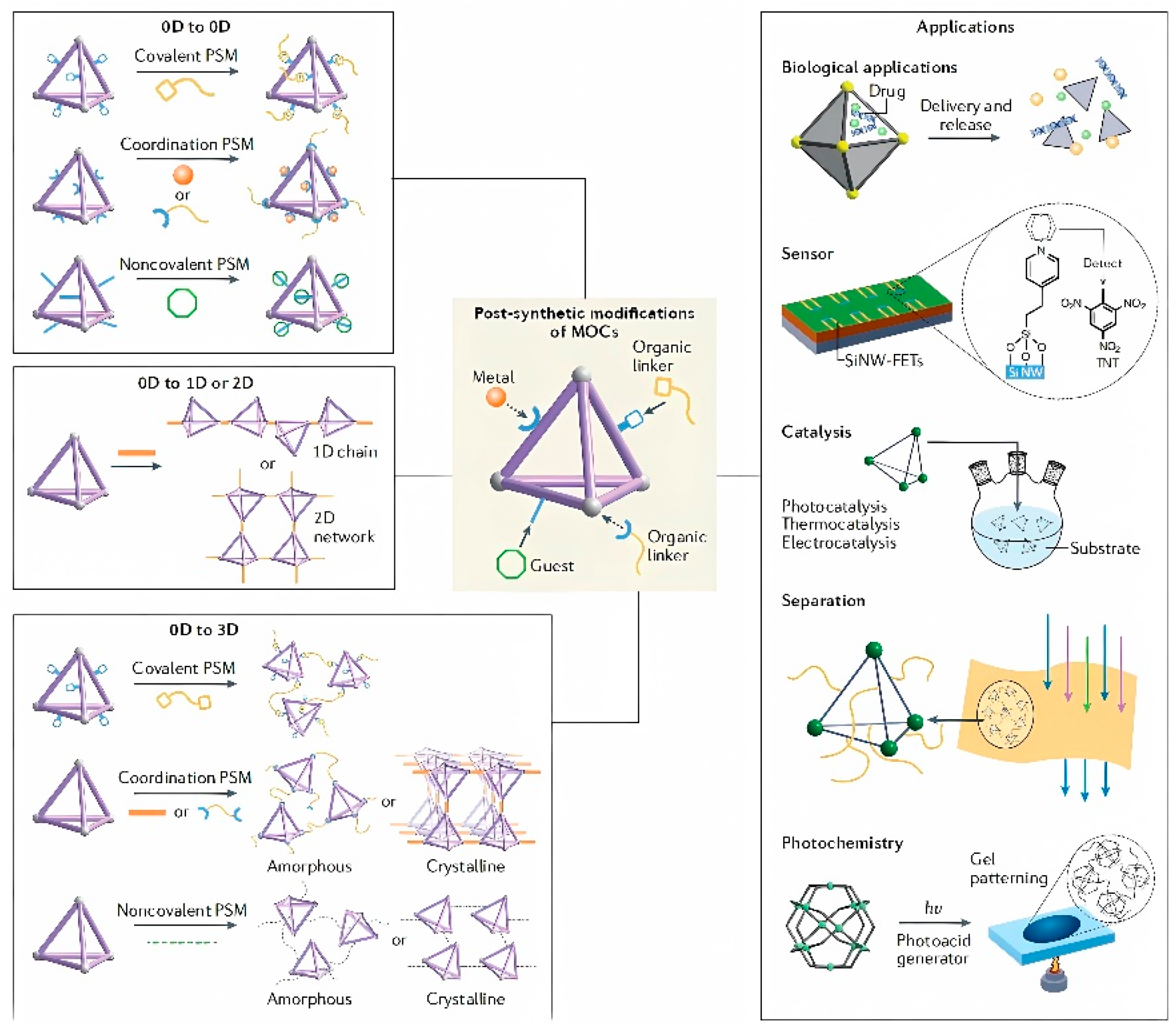

The group of Chen and Zhang synthesize the advances in the considerations raised in post-synthetic modifications (PSM) reactions exclusively in pre-assembled MOCs, leaving aside the structural dissociation and reintegration in PSM processes, as are building block exchange reactions ligand/metal; structural transformations instead of post-assembly triggered by various stimuli; and host–guest chemistry inside of the MOCs cavities. On the contrary, they emphasize covalent and coordination modification in terms of PSM structural variation of both exterior and interior, nevertheless, noncovalent strategies center only on exterior PSMs. Another important characteristic that the authors discuss is about post-modified products, in this regard, they make a relevant division of 0D cages to 0D cages; 0D cages to one-dimensional (1D) or two-dimensional (2D) structures; 0D cages to three-dimensional (3D) network materials [

42], as exemplified in

Figure 4.

Strategies to elaborate MOCs have drifted over time, and its structural modification is influenced by synthesis and its versatility (

Figure 5). It is of consideration that the presence of various reversible interactions in the MOC systems may be easily disrupted during the PSM process. This characteristic considers the orthogonality between reactions and the supramolecular interactions in the MOCs [

43]. A post-synthetic covalent modification strategy favored by a [4+2] cycloaddition between anthracene and maleimide under mild conditions to obtain MOCs with tailored functions is well seen because they are true platforms to implant others functional groups, namely, cyclohexyl, α-phenethyl, a chiral binaphthol moiety, tetraphenylethylene group, and pyrene substituent through the covalent PSM process [

43].

Coordination bonds within coordination chemistry are attractive largely because of the potential in generating porous materials for the confinement of varied molecular species with engineered molecular affinity. The reason for this behavior in the case of the coordination cages (CCs) or MOCs is orchestrated from the smallest units to form large molecular networks. The fine balance between these coordination and the molecular geometry is an ability described in 1990 by Fujita et al., [

44] and Tateishi et al. recently [

45].

The controlled postsynthetic fuctionalization of MOPs using coordination chemistry on metal ions and covalent bonds in organic linkers is exploited in Rh

II-based materials with cuboctahedral geometry, for the high microporosity of the HRhMOP of 947 m

2/g and that of the Rh-OH-MOP of 548 m

2/g, i.e., [Rh

2(bdc)

2(H

2O)

2]

12 and [Rh

2(OH-bdc)

2(H

2O)

1(DMA)

1]

12; where OH-bdc = 5-hydroxy-1,3-benzenedicarboxylate and DMA =

N,

N-dimethylacetamide), as they can withstand aggressive reaction conditions, including high temperatures and the presence of strong bases [

46].

The need for considering intermolecular conjugational effects is further highlighted by the fact that in a post-modification protocol to covalently conjugate a chiral cholesteryl pendant to MOPs. Both experimental and computational measurement results validated the role of intercholesteryl forces in MOPs, which achieved the chirality transfer to supramolecular scale with chiral optics. It should be mentioned that formation a supramolecular chirality is associated with the cholesteryl groups as well as the induced helical packing. The individual alternative self-assembly of MOP produces achiral crystalline plates due to the absence of stereocenters [

47].

It is also noteworthy that application in multi-fold post-modification of macrocycles and cages, introducing functional groups into two- and three-dimensional supramolecular scaffolds bearing fluorinated substituents [

48] associated with the activation of strong C-F bonds [

49] opening possibilities in multi-step supramolecular chemistry employing readily available isocyanates. In a particular case, benzylamine was reacted in an isothiocyanate-promoted cyclisation with azadefluorination. The difluoro substitution leads to the formation of a cyclic six-membered urea (1,3-diazinan-2-one), enabling exo-functionalization of the supramolecular entities [

50].

In another study, an alkyne-based hydrocarbon cage was synthesized using alkyne-alkyne coupling in the cage forming step. Reaction of the cage with Co

2(CO)

8 results in metalation of its 12 alkyne groups to give the Co

24(CO)

72 adduct of the cage [

51]. In this same consideration and support of complementary techniques of

1H-NMR, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), and 1D-exchange spectroscopy (EXSY) were used in the investigation of pyridyl ligand substitution of a model complex M(py)

2 (M = (

N,

N,

N′,

N′-tetramethylethylenediamine)palladium

II, py = pyridine). Basically, using different temperatures,

1H-NMR and 1D-exchange spectroscopy (EXSY) the reaction rates and activation energies (

Ea) for pyridyl ligand substitution under different reagent and reactant conditions were determined [

52].

Holistic considerations such as environmental considerations will be an essential part of the efficient PSM of MOCs to fabricate catalysts that are not accessible under conventional synthesis conditions for instance, stabilizing highly active but vulnerable catalysts to achieve high-efficiency catalysis.

In a communication, Pausch et al. specified the multiple post-modification of macrocycles and cages, introducing functional groups into two- and three-dimensional supramolecular structures with fluorinated substituents, opening new possibilities within supramolecular chemistry. The chemical essence of this structural modification utilizes benzylamine- and 1,4-diisocyanatobenzene-promoted cyclization [

50].

Two homochiral porous organic cages Imine condensations of tetrapic 5,10-di(3,5-diformylphenyl)-5,10-dihydrophenazine and ditopic 1,2-cyclohexanediamine yield two chiral [4+8] organic cage isomers with absolute alone different topologies and geometries depending on the orientations of four tetraaldehyde units relative to each other. One isomer has a Johnson-type structure while another embraces a tetragonal prismatic structure [

53].

It is appreciated that scientific reports on enantioselective structural isomerization are remarkable for the substantial advances in the design and construction of diversified functional supramolecular systems.

5. Specificity of MOCs

The ability of ligands and metal ions/nodes to form complex self-linked molecular networks is as broad as that of any supramolecular system; discrete, porous architectures are remarkable given the simplicity of their components and the relative ease of their synthesis. In this context, pioneering works took advantage of the high porosity of Pd

12L

24 nanospheres allowing the entry and exit of a variety of reagents useful for general chemical transformations [

54]. Such combinations can be further sophisticated to form structures with an evident selectivity towards designer chemical transformations. The next important contribution in this area divulge the synthesis of Pd

2L2

4 type MOC (L2=5-Azido-

N,

N’-di-pyridin-3-yl-isophthalamide) and its ability to produce the supramolecular metallogel (PdG), this compound was subsequently loaded with DOX and successfully delivered to B16‒F10 melanoma cells. Furthermore, the metallogel was characterized by dynamic rheology showing a reversible property conducive to topical application [

55].

Similar ideas to those applied by Bera et al. [

55] in relation to metal-organic cages could be used as cross-linkers in microgels or nanogels. This implication is demonstrable in palladium organic cages with acrylamide side chains by precipitation polymerization. The resulting nanogels may favor applications such as specific sorbents for chloride ions and for the reactive release of the anticancer drug abiraterone [

56].

Another criterion specified by Berber et al., used a seven-residue proline design (trans-4-hydroxyproline)-(proline)-5-(trans-4-hydroxyproline) using a solid-state microwave-assisted technique, with a tert-butyl carbonyl group, to avoid competitive binding of a free amine to palladium(II) and to act as a reporter signal in

1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). That decision was made in consequence of previous reports suggesting that six residues were the minimum required to ensure stable formation of a polyproline (PPII) helix in aqueous solution, with a repeat length of approximately 9Å, where every third residue aligns [

57]. Avery, Algar and Preston [

58] detail different methodologies and complexities of lantern cages. For example, they describe different ligands to form them, such as low symmetry ligands (homoleptic arrays), different metal ions (heterometallic arrays), and differentiated cavities (multicavity arrays). This may anchor the symmetric geometries into self-assembled metallo-supramolecular systems of lantern cages.

Recently, Roy et al., [

60] have opened possibilities in the distribution of stress relaxation time scales in metal-coordinated hydrogels with a variety of cross-linker sizes, including ions, metal-organic cages, and nanoparticles. The same characteristic patterns on guest selected in differential spaces within polymeric hydrogels cross-linked with metal-organic cages was one of the contributions of Küng et al. [

59] when designing the synthesis of a series of gels based on metal-organic cages with varied bond lengths and ranging from an average molar mass of 1 to 6 kDa, for graphical detail see

Figure 6.

Stepwise deformation experiments of such polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based gels with a variety of cross-linking valencies were performed and their corresponding relaxation curves were evaluated. Le Roy and co-workers have prompted nitrocalecol-functionalized PEG whose cross-linking is cemented by Fe

3+ ions and by iron oxide nanoparticles with an average diameter of 7 nm and a surface area allowing a valency of ~100 ligands. Another set of gels is made with bispyridine-functionalized PEG, where bis-meta-pyridine ligands induce self-assembly of gels that are cross-linked by Pd

2L

4 nanocages, in another instance, bis-para-pyridine ligands induce self-assembly of gels that are cross-linked by Pd

12L

24 nanocages [

60]. On the other hand, Sutar et al. establish that a hybrid material incorporating self-assembled metal-organic cages in a gel matrix could result in an excellent proton conductor. These authors elucidate that in the open supramolecular framework {(Me

2NH

2)

12[Ga

8(ImDC)

12] DMF∙29H

2O} (ImDC = 4,5-imidazole dicarboxylate), MOCs with a [Ga

8(ImDC)

12]

12− structure are linked together by a dimethylammonium (DMA)-assisted hydrogen bonding interaction, where free carboxylate groups on the surface of the MOCs (~24 per MOC) together with extensive hydrogen bonds between the host water molecules and DMA cations around the MOC contribute to an enviable conductivity of (2.3 × 10−5 S cm

−1) under ambient conditions [

61].

As part of their study designed to elucidate a class of gels assembled from polymeric ligands and metal-organic cages (MOCs) as junctions, Johnson and co-workers presented evidence for the formation of gels that can be finely tuned and may exhibit increased branching functionality. Namely, a low network branch functionality polyMOC based on an M

2L

4 paddlewheel cluster junction and a higher network branch functionality compositionally isomeric one based on an M

12L

24 cage [

62].

In another order of ideas, Calvo-Lozano et al. argue that there are several examples that take advantage of molecular recognition of discrete molecular cages to design optical sensors, in particular to create a Rh-MOP functionalized bimodal waveguide (BiMW) sensor for real-time detection of water contaminants such as 1,2,3-benzotriazole (BTA) and the insecticide imidacloprid (IMD) in less than 15 minutes, presenting limit of detection (LOD) as low as 0.068 μg/mL for BTA and 0.107 μg/mL for IMD [

63]. Also, advances in modulating the conformation of stimuli-responsive MOCs have been structured with bis-pyridyl dithienylethylene (DTE) groups. The presence of Pd

2+ is important to assist the reversible photoswitching between small Pd

3L

6 rings irradiated with green light and large Pd

24L

48 rhombicuboctahedra when exposed with ultraviolet (UV) light [

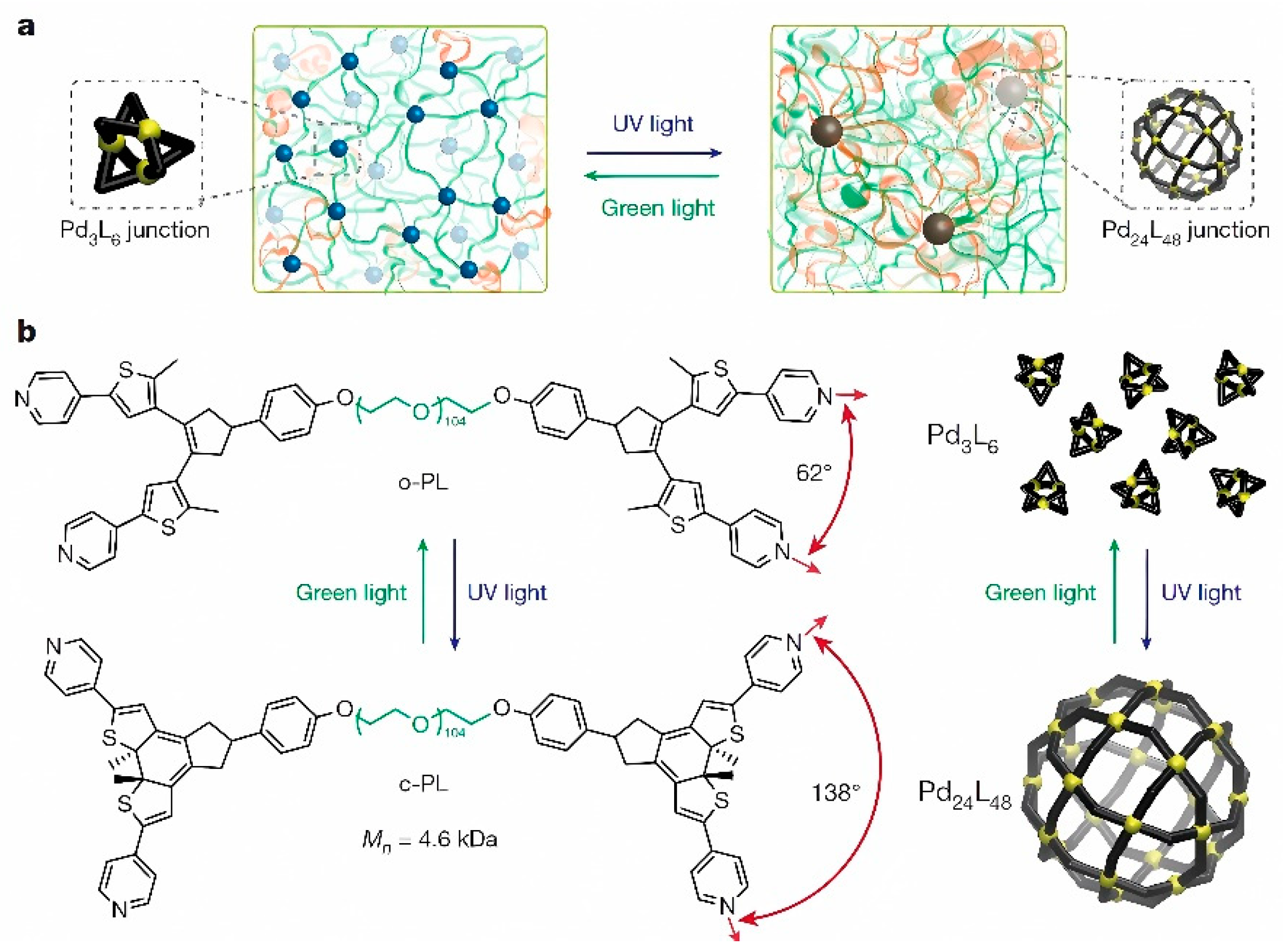

64].

Figure 7 indicates a route to the design of materials with switchable topology (

Figure 7a) and a synthetic design of a poly(ethylene glycol)-based polymeric ligand (

Figure 7b).

UV-induced changes of arylazopyrazoles in the presence of a self-assembled cage based on Pd-imidazole coordination have been subjects of systematic study. In this context, the isomerization of the

E-isomer of arylazopyrazole, which is not water-soluble by itself, has been exploited in aqueous media. NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography have demonstrated, in a complementary manner, that each cage can encapsulate two

E-arylazopyrazole molecules. The UV-induced switch to the

Z-isomer was accompanied by the release of one of the two guests from the cage and the formation of a 1:1 cage/

Z-arylazopyrazole inclusion complex. DFT calculations unambiguously suggest that this process involves changes in the cage conformation. In their calculations, Hanopolskyi et al., argue that a retroisomerization is induced with green light resulting in the initial 1:2 cage/

E-arylazopyrazole complex [

65].

Critical self-assembly with Pd

II cations leads to the formation of Pd

nL

2n supramolecular architectures. With the uniqueness of using diazocine in the stable cis isomeric formation, structural strain could be an obstacle in the formation of a defined structure, i.e., a unique structural product. Clever and co-workers pointed out that diazocine in the metastable trans isomeric form assembles into a lantern-shaped cage design [Pd

2(

trans-L)

4] as an exclusive species [

66].

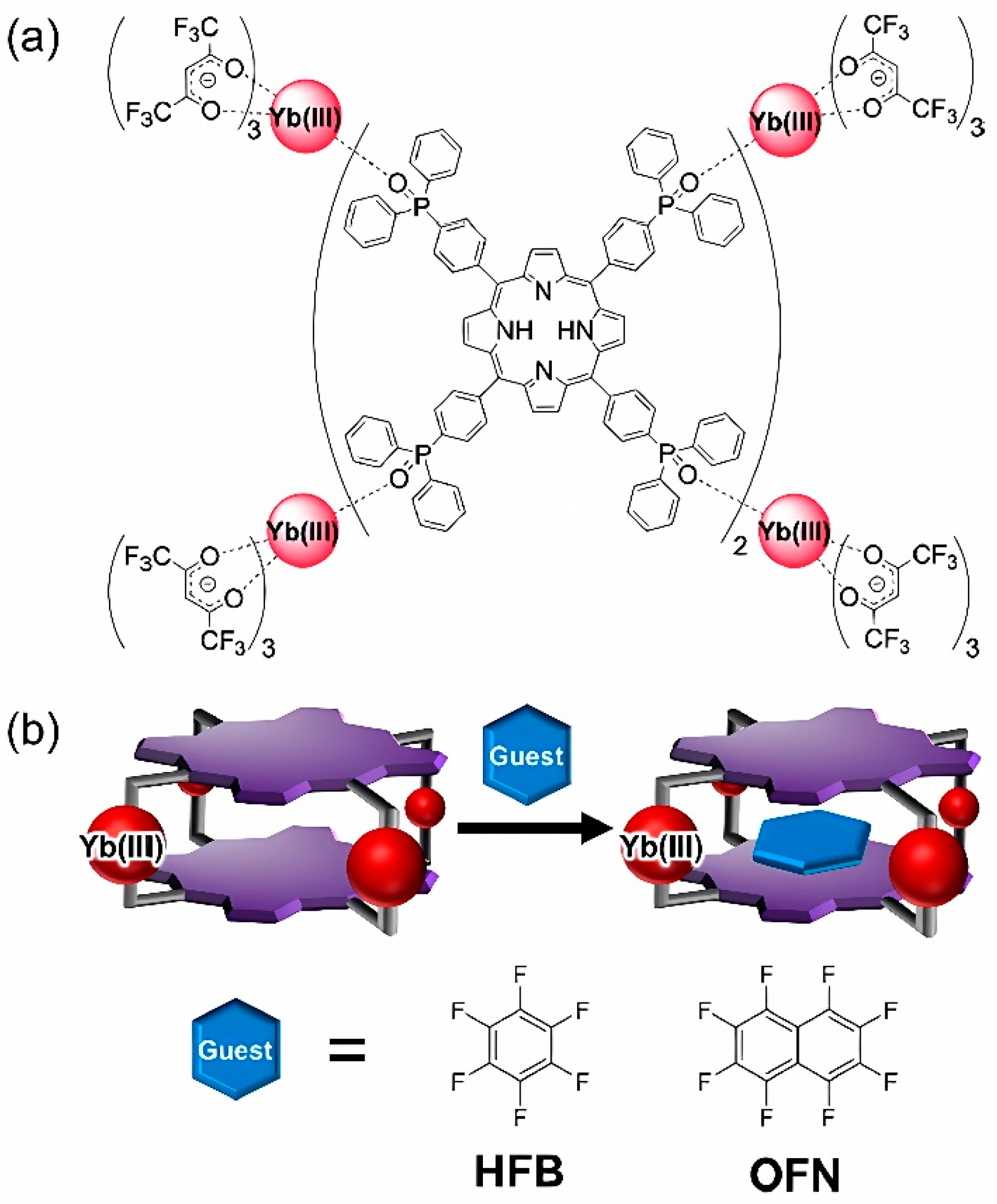

In further technological advances, Hosoya et al. proposed absolute hardness as they synthesized a host-responsive, luminescent MOC composed of porphyrin dyes and Yb

III complexes [

67]. The MOC possesses the defined three-dimensional cavity to intercalate small planar aromatic perfluorocarbons inside the cage creating 1:1 host-guest supramolecules detailed in

Figure 8a and

Figure 8b. The authors argued that the host-guest packing partially inhibited oxygen molecules from approaching the cage, thereby enhancing the near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence of Yb

III. It is quite remarkable that a diazocine moiety is implemented in the main chain of a banana-shaped bis-pyridyl ligand in order to fully sustain a photoswitching specificity.

The convenience of using diverse stimuli-responsive molecules such as spiropyran, spirooxazine, chromene, azobenzene, and diarylethene derivatives in combination with a variety of transition metals may result in the development of stimuli-responsive devices, highlighting the role of cooperative metal−photoswitch interactions in tailoring specific material properties and design applications [

68].