I. Introduction

Biological warfare is a serious concern for every nation in the world. Recent outbreaks due to COVID-19, Ebola virus, zika virus, H1N1 influenza, anthrax, H5N1 avian flu have raised warnings to health regulatory authorities across the world. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines bioterrorism as the intentional release of viruses, bacteria, or other germs (i.e., agents) used to cause sickness or death in humans, animals, or plants. There have been at least 33 reports of bioterrorist attacks, including 21 cases in the United States, 3 cases in Kenya, 2 cases each in Pakistan and the United Kingdom, and 1 case each in Columbia, Russia, Japan, Tunisia, and Israel [

1]. Regarding the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, two theories were widely published. In the first theory, the United States was claimed to be responsible for the production and early development of the virus. On the contrary, in the second theory, China’s Wuhan laboratory of virology was recognized as the primary center of the Covid-19 virus epidemic [

2]. However, the common line in both theories is the attempt to create a biological weapon. Several events during the COVID-19 pandemic give a global narrative on the preparedness to counter a biological crisis. According to reports, more than 3.5 million people lost their lives due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Several measures were adopted globally to ensure biosafety and mitigate the spread of the virus including better communication, robust training of healthcare staff, new regional center for disease control (CDC), faster development of medicines etc. Also, bioweapons can indirectly affect the health, prosperity and harmony of a country by affecting food production of any agriculture field [

3].

This article discusses the limitations of the healthcare system observed during the COVID-19 pandemic and relevant defense actions taken to combat bioterrorism by different nations across the globe. It also offers areas of improvement to restore the bioterror security of the world [

4].

II. Defense Measures

Defense measures depend on the type of bioweapon used for biological warfare. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lists 35 agents as potential bio-weapons, however, they are all categorized into 3 different groups based on their estimated threat level (

Table 1).

Defense mechanisms against bioterrorism decrease the effectiveness of the attack, putting a high cost-to-benefit burden on the adversary. A defense measure for bioterrorism would be an adequate medical treatment response to casualties of the bioweapon, decreasing mortality and the overall effectiveness of the weapon. Some of the measures taken by countries across the globe to stay prepared against COVID-19-type pandemics are discussed.

a. Medicines, Vaccines and Antidotes

One of the major challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic was unavailability of specific medication against the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Researchers tried to use repurposing of already existing drugs and came up with few leads. Remdesivir and Hydroxychloroquine became two popular drugs to prevent the spread of the virus [

6]. However, after a few months it was observed that both the drugs did not show clinical benefits [

7]. Finally, without specific medication the only hope left was the development of vaccines.

The vaccine developed by Pfizer-BioNTech used the help of mRNA and artificial intelligence (AI) [

8]. AI-based strategies for COVID-19 vaccine development include in silico modeling for vaccine design and optimization, machine learning algorithms for predicting antigenic epitopes, and AI-based genetic sequencing and analysis. Machine learning algorithms can analyze large viral protein datasets to determine which ones are most likely to elicit an immune response. In silico modeling can be used to design and optimize vaccine candidates based on their predicted efficacy and safety profiles. Genetic sequencing and analysis using AI-based tools can help to identify mutations in the virus that may affect vaccine efficacy and inform the design of new vaccines [

9]. Another example is the use of deep learning to predict and design a multiepitope vaccine (DeepVacPred). The DeepVacPred computing system was able to predict 26 potential vaccine subunits from the SARS-CoV-2 tip protein sequence [

10].

For development of medicines, as newer medicines take years to develop, AI based tools for medicines are presently promoted to hasten the process of drug discovery. The COVID-19 crisis has provided important lessons to the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries regarding the use of already available data. Due to modern algorithms and new hardware the application of AI has exponentially accelerated the process of drug discovery [

10]. However, regulatory controls are required to avoid any misuse of AI as a few years back in 2017, AI was used to design VX which is a venomous nerve agent that can cause severe paralysis [

11].

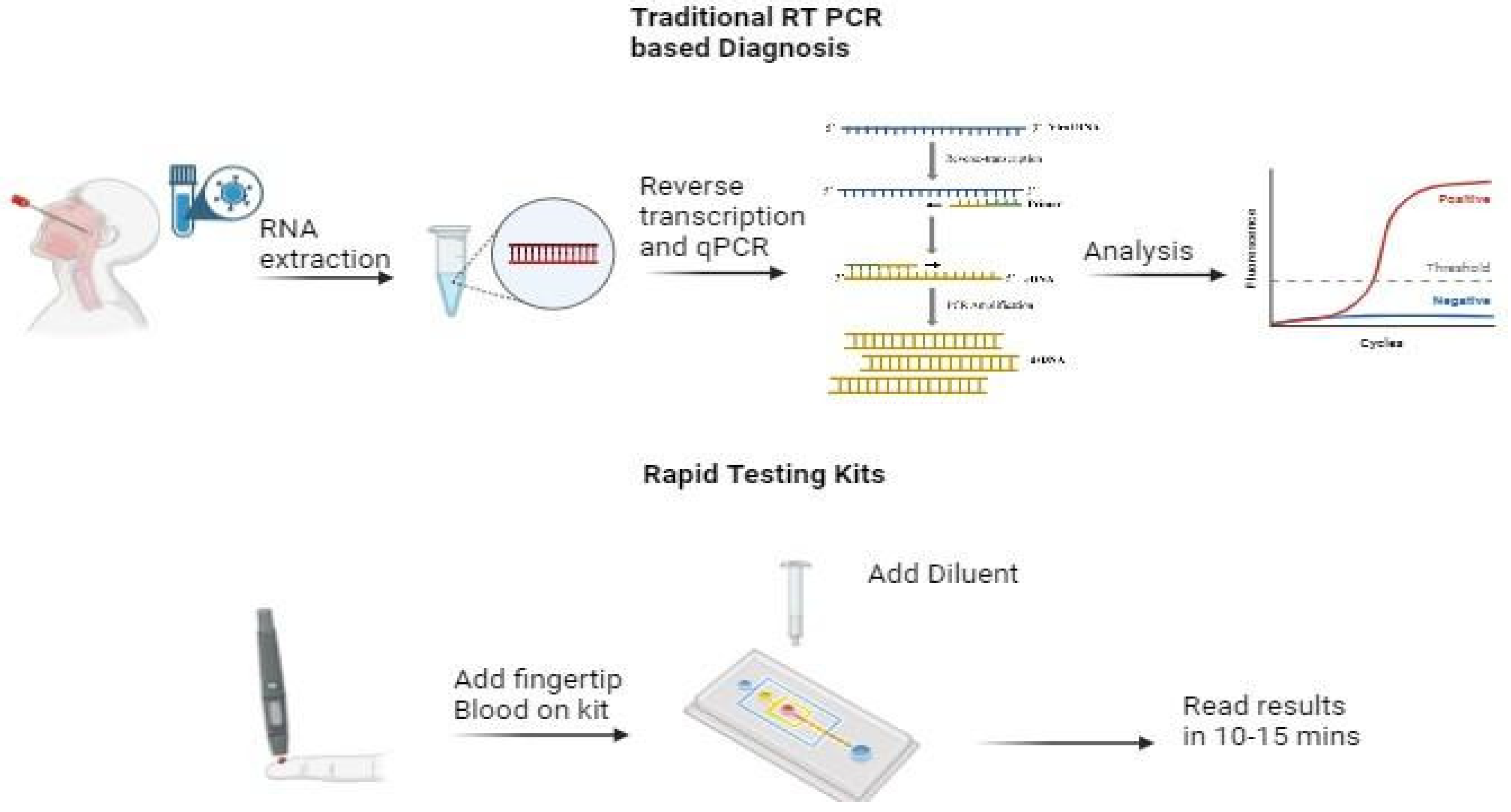

b. Development of Newer Diagnostic Techniques

Early diagnosis helped several resource-rich countries to confine the patients and prevent the spread of the virus. However, countries with limited resources faced challenges related to timely diagnosis (

Figure 1). To resolve this issue, mobile laboratories were deployed in several countries in Europe. Such mobile laboratories are designed to operate in resource-limited areas and are rapidly deployable. They contain equipment to perform basic diagnostic analysis on given pathogens and are intended to give a short-time relief to governmental diagnostic laboratories until a stable operative infrastructure is built [

12].

In addition to it, the availability of diagnostic kits for biological warfare are critical for ensuring preparedness and response to biological threats. After COVID pandemic, several portable diagnostic kits and biosensors were developed for remote diagnosis of infected patients. Some of the diagnostic kits are mentioned in

Table 2. These at-home OTC COVID-19 diagnostic tests are FDA authorized for self-testing at home (or in other locations) without a prescription.

Moreover, the advancement in the microscopic techniques such as immunoelectron microscopy, cryo-electron microscopy, and electron tomography has lead to better identification of viruses which eventually helps in accurate diagnosis. However, to avoid confusion between cellular structures and viral particles, care should be taken during analysis [

13].

c. Public Health Policy

The Government of the UK developed a biological security strategy against high consequence risks. A major health crisis (such as pandemic influenza or new infectious diseases), antimicrobial resistance (AMR), a deliberate biological attack by state or non-state actors (including terrorists), animal and plant diseases, which themselves can pose risks to human health, accidental release and dual-use research of concern. New Zealand’s robust public health measures, citizen compliance, and continued efforts to sustain a caseload under 20 since April is a strong deterrent for biological attack.

Lancet published a report on the comedy of errors with respect to the application of hydroxychloroquine against COVID-19. It highlights the importance of carefully selecting the right medicine with sufficient data to avoid the risk to the lives of people, and the diversion of scarce resources. The second highlight was that science should step over politics. Lastly, it emphasized the importance of teamwork to minimize duplication and accelerate results [

7].

To increase communication with people, the government introduced many contact tracing tools and applications during the COVID-19 pandemic. These applications have helped to govern the risk associated with the infected persons even after the quarantine period. However, these applications also jeopardize the privacy of data [

14]. For the future, regulators need to address privacy concerns so that people feel safe from biological attack as well as cyber attacks.

d. PPE Kits and Biosafety Cabinets

The WHO took some time initially to provide the guidance to industry and institutions for handling the COVID-19 samples. Due to this delay, laboratories made their own protocols. However, after 6 months, the WHO has given guidance for the handling of COVID-19 with a universal list of recommendations and best practices for the safe handling of viral diagnostics. Biosafety cabinets (BSC Class III) were required for processing COVID-19 samples for nucleic acid amplification test diagnosis. Several low- and middle-income countries faced concerns related to biosafety cabinets [

15]. However, ‘Sustainable Laboratories Initiative Prior Assessment Tool’ is an online tool supporting laboratory managers in allocating funding and laboratory equipment that is provided by the Chatham House think tank [

15].

Another safety concern was related to the shortage of PPE kits. These are commonly used in health care settings such as hospitals, doctor’s offices and clinical labs. When used properly, PPE acts as a barrier between infectious materials such as viral and bacterial contaminants and your skin, mouth, nose, or eyes (mucous membranes). The barrier has the potential to block transmission of contaminants from blood, body fluids, or respiratory secretions. PPE may also protect high-risk patients, such as those undergoing surgery or those with medical conditions like immunodeficiency, from exposure to substances or potentially infectious material brought in by visitors and healthcare workers [

16]. In Thailand researchers studied the usage of PPE kits before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. The team found that there was a significant increase of usage of these PPE kits (around 16%).

In general the composition of face masks is mainly of polypropylene, polycarbonate, and poly(ethylene terephthalate). PPE kits evolved to include more robust and specialized components. N95 respirators gained prominence due to their effectiveness against airborne particles, replacing simple surgical masks in many scenarios. These masks did not have antimicrobial actions. During the pandemic, researchers have used different nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes, graphene oxide and its derivatives, and hexagonal boron nitride as antimicrobial agents or self sterilizing agents. These masks have been claimed to be effective in preventing cross contamination of COVID-19 infection [

17].

Another environmental issue with the usage of PPE kits during COVID, were their disposal as most of the traditional PPE kits are made of non biodegradable materials [

18]. Hence, it adds to environmental issues on both terrestrial and marine ecosystems, which include Global Warming Potential (GWP), Human Toxicity Potential (HTP), Eutrophication Potential (EP), Acidification Potential (AP), Freshwater Aquatic Ecotoxicity Potential (FAETP) and Photochemical Ozone Depletion Potential (POCP). To reduce the environmental waste caused by PPE kits, bioplastic materials have been proposed for the manufacture. Another way to reduce the PPE waste is to convert it into biofuels [

19]. Moreover, some of the major drawbacks of wearing PPE kits during COVID-19 were discussed such as the significant negative impact of prolonged use of PPE on the non-technical skills of surgeons including vision, communication, and overall comfort [

20].

e. Enhancement of Centers for Disease Control (CDC)

CDC performed several activities to ensure healthy living. These activities were carried out under the following departments: [

21]:

a. Vaccine Task Force: To oversee the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines, including distribution, administration, and public education.

b. Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics (CFA) to improve the CDC’s ability to predict and model outbreaks, and to provide real-time data to inform public health decisions. The CDC’s Center for Global Health (CGH) enhances global partnerships and initiatives to strengthen international health systems and improve global disease surveillance.

c. Center for Environmental Health (CEH) to focus on environmental factors that impact public health, including those exacerbated by pandemics.

d. Center for Data Science and Technology to strengthened to support the use of data

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has opened regional CDC in the Asia-Pacific region in 2024 in Tokyo, Japan after the COVID-19 pandemic to develop strong links addressing global health security [

22]. Priorities for the new regional office include: Expanding CDC’s core global health security capacity by building stronger collaboration and partnerships in the East Asia and Pacific region, the ability to detect public health threats and respond swiftly, and knowledge and information exchange between CDC and the region.

f. Socioeconomic Factors

COVID-19 imposed several restrictions for meetings and gatherings. The degree of which ranged from social distancing to quarantine. Although these measures were important to reduce the spread of the virus, the process itself created a lot of socioeconomic distress. During the pandemic, several people suffered from loss of jobs, poor contacts, and absence of important events. It took several months to understand the ways to work under restricted conditions.

Preparedness after COVID-19, has also been improved in terms of socioeconomic factors. These factors affected not only health but also were responsible for several deaths [

23]. The technology helped in reviving few of these important events through virtual meetings, online work, video conferences etc. (maybe a table or figure to give an example). This has led to better preparedness of people in staying connected to each other both professionally and personally. In other words, technology has developed a cushion for the society to bear a shock for any future pandemic.

g. Training and Communications for Biosafety

“Biosafety/Biosecurity Hybrid Train the Trainers Program in Georgia” organized by the Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), co-funded by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs and ‘chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear’ (CBRN) Centers of Excellence Project. This program, available in both English and Georgian, taught Basic Laboratory Biosafety, Biorisk Assessment, Dual-Use, and how to train new trainers in a hybrid manner, starting with interactive online sessions, followed by in-person training once the travel restrictions were released. The Netherlands Biosecurity Office has developed a toolkit that can help to increase biosecurity awareness (Bureau Biosecurity). Besides an informative film, and gadgets to raise biosecurity awareness (postcards and the 10 golden security rules), the biosecurity toolkit also includes the ‘Biosecurity Self-scan Toolkit’ and the “Vulnerability Scan”. These are online tools to analyze biosecurity vulnerabilities in an organization dealing with high consequence pathogens. Furthermore, as precise instructions for researchers on how to perform a dual-use risk assessment were largely lacking, the Biosecurity Office developed the “Dual-Use Quickscan”.

Biosecurity Central is a publicly available web-based library that helps users find relevant and reliable sources of information for key areas of biosecurity. The site aims to widely disseminate and share knowledge to help advance biosafety and biosecurity.

Internet of things (IoT) has an integrated biological warfare framework which can provide an integrated decision support mechanism to address several challenges of biowarfare including:

Monitoring a biological outbreak

Identifying the cause of outbreak and source

Predicting potential exposure

Planning an effective response and risk reduction strategy

Notifying the related authorities (such as hospitals, local governments, law enforcement, military, pharmaceutical industries, etc.)

Some of the existing IoT platforms such as the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN), based semi-supervised learning approach for clinical decision support in the health-IoT platform, focus on other health conditions other than pandemic diseases. It improves the classification process and facilitates learning about the illness, and suggests a suitable treatment course. These techniques help in the mitigation of biological warfare [

24]. In 2023, Esmaeili developed a sensing model for a body area network for monitoring soldiers to help to mitigate biological warfare. This model has the advantage of being lightweight and has reduced energy consumption [

2].

h. Biophysical Detection Systems for Detection in Environment

Biological agent detection systems are field kits and assays that are used to discriminate harmful and harmless biological material present in the environment or the sample. This equipment assists responders with the initial risk assessments following potential attacks... These systems have separate and independent units assembled in a single system for different purposes. For sample collection, various types of samplers/collectors are being used, such as cyclone samplers, viable particle size samplers, and virtual impactors. Whereas for detection/identification purposes, different types of detectors, such as fluorescence-based detectors and particle size-based detectors etc. are being used. Nowadays, biological detectors based on PCR are also widely used for various biological agent detections [

25]. Song et al. developed fiber-optic, microsphere-based, high-density array composed of 18 species-specific probe microsensors to identify biological warfare agents including

Bacillus anthracis,

Yersinia pestis,

Francisella tularensis,

Brucella melitensis,

Clostridium botulinum, and vaccinia virus. The microsensor was based on PCR technique [

26]. Saito et al. developed a portable rapid biodetection system that detects both chemical and biological warfare from the environmental air. The operation time was around 15 mins for collection and detection [

27]. The commercial technologies such as Versalogic SBC power systems and Rapid Agent Aerosol Detector (RAAD) help to rapidly identify the toxic pathogens in the environment air. RAAD is based on near-infrared and fluorescence-based detection, which collects data and predicts if the composition of particles appears to be a potential threat [

28]. Some other similar detection systems are mentioned in

Table 3.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the issue related to biological warfare has become a major global concern after the COVID-19 pandemic. Combating biological warfare necessitates a multifaceted approach that integrates research, innovation, policy making and technology. Through the development of rapid diagnostic tools, personal protective equipment, biophysical detection systems, effective medicines/vaccines the safeguard of public health can be ensured. Strengthening global cooperation and developing better biodefense infrastructure by establishing more regional CDC are crucial in responding to biological threats.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this work.

Author Contribution

Ahmad Reza Rezaei: - Writing, editing, conceptualization

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Consent of Participate

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there is no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- K. Wangi and C. Smith, “Biodefense: Expanding Nursing Strategies After the SARS-CoV-2 Threat,” Journal of Radiology Nursing, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Esmaeili, S. R. Kamel Tabbakh, and H. Shakeri, “A priority-aware lightweight secure sensing model for body area networks with clinical healthcare applications in Internet of Things,” Pervasive and Mobile Computing, vol. 69, p. 101265, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Nag, L. Roy, Shruti, S. Santra, and A. Deyasi, “Efficient Detection of Bioweapons for Agricultural Sector Using Narrowband Transmitter and Composite Sensing Architecture,” in Convergence of Deep Learning In Cyber-IoT Systems and Security, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2022, pp. 349–366. [CrossRef]

- “COVID-19 Pandemic Origins: Bioweapons and the History of Laboratory Leaks.” Accessed: Oct. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://sma.org/article/.

- “Types of Bioweapons – Geographies of Bioweapons.” Accessed: Oct. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://sites.middlebury.edu/bioweapons/types-of-bioweapons/.

- H. A. Blair, “Remdesivir: A Review in COVID-19,” Drugs, vol. 83, no. 13, pp. 1215–1237, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- I.S. Schwartz, D. R. Boulware, and T. C. Lee, “Hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19: The curtains close on a comedy of errors,” The Lancet Regional Health – Americas, vol. 11, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- “MRNA Artificial Intelligence in Vaccine Development.” Accessed: Oct. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.pfizer.com/news/articles/how_a_novel_incubation_sandbox_helped_speed_up_data_analysis_in_pfizer_s_covid_19_vaccine_trial.

- A. Ghosh, M. M. Larrondo-Petrie, and M. Pavlovic, “Revolutionizing Vaccine Development for COVID-19: A Review of AI-Based Approaches,” Information, vol. 14, no. 12, Art. no. 12, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Floresta, C. Zagni, D. Gentile, V. Patamia, and A. Rescifina, “Artificial Intelligence Technologies for COVID-19 De Novo Drug Design,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 23, no. 6, p. 3261, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Kirby, “Can a 50-year-old treaty still keep the world safe from the changing threat of bioweapons?,” Vox. Accessed: Oct. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/23700801/bioweapons-biological-weapons-convention-united-nations-covid-coronavirus-russia-biology.

- S. A. Rutjes, I. M. Vennis, E. Wagner, V. Maisaia, and L. Peintner, “Biosafety and biosecurity challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond,” Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., vol. 11, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. S. Goldsmith and S. E. Miller, “Modern Uses of Electron Microscopy for Detection of Viruses,” Clinical Microbiology Reviews, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 552–563, Oct. 2009. [CrossRef]

- V. Q. T. Li, L. Ma, and X. Wu, “COVID-19, policy change, and post-pandemic data governance: a case analysis of contact tracing applications in East Asia,” Policy and Society, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 129–142, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Karthik et al., “Biosafety Concerns During the Collection, Transportation, and Processing of COVID-19 Samples for Diagnosis,” Archives of Medical Research, vol. 51, no. 7, pp. 623–630, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. for D. and R. Health, “Personal Protective Equipment for Infection Control,” FDA. Accessed: Oct. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/general-hospital-devices-and-supplies/personal-protective-equipment-infection-control.

- C. Mahasing et al., “Changes in Personal Protective Equipment Usage Among Healthcare Personnel From the Beginning of Pandemic to Intra-COVID-19 Pandemic in Thailand,” Annals of Work Exposures and Health, vol. 67, no. 5, pp. 637–649, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Kumar et al., “COVID-19 Creating another problem? Sustainable solution for PPE disposal through LCA approach,” Environ Dev Sustain, vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 9418–9432, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. J. Rowan and J. G. Laffey, “Unlocking the surge in demand for personal and protective equipment (PPE) and improvised face coverings arising from coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic – Implications for efficacy, re-use and sustainable waste management,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 752, p. 142259, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. A. Alarfaj et al., “Impact of wearing personal protective equipment on the performance and decision making of surgeons during the COVID-19 pandemic: An observational cross-sectional study,” Medicine (Baltimore), vol. 100, no. 37, p. e27240, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Schiff and D. J. Mallinson, “Trumping the Centers for Disease Control: A Case Comparison of the CDC’s Response to COVID-19, H1N1, and Ebola,” Administration & Society, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 158–183, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- “CDC Newsroom,” CDC. Accessed: Oct. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/p0202-cdc-japan-office.html.

- I. Nicola et al., “The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review,” International Journal of Surgery, vol. 78, pp. 185–193, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- “Role of Internet of Things in Biological Warfare,” IDSA. Accessed: Oct. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://idsa.demosl-03.rvsolutions.in/publisher/role-of-internet-of-things-in-biological-warfare/.

- “Biological Agent Detection Equipment | Homeland Security.” Accessed: Oct. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.dhs.gov/publication/biological-agent-detection-equipment.

- L. Song, S. Ahn, and D. R. Walt, “Detecting Biological Warfare Agents - Volume 11, Number 10—October 2005 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC.” . [CrossRef]

- I. Saito et al., “Field-deployable rapid multiple biosensing system for detection of chemical and biological warfare agents,” Microsyst Nanoeng, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1–11, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- “Highly sensitive trigger enables rapid detection of biological agents,” MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Accessed: Oct. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://news.mit.edu/2020/highly-sensitive-trigger-enables-rapid-detection-biological-agents-0916.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).