Submitted:

17 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. SMOTE Oversampling

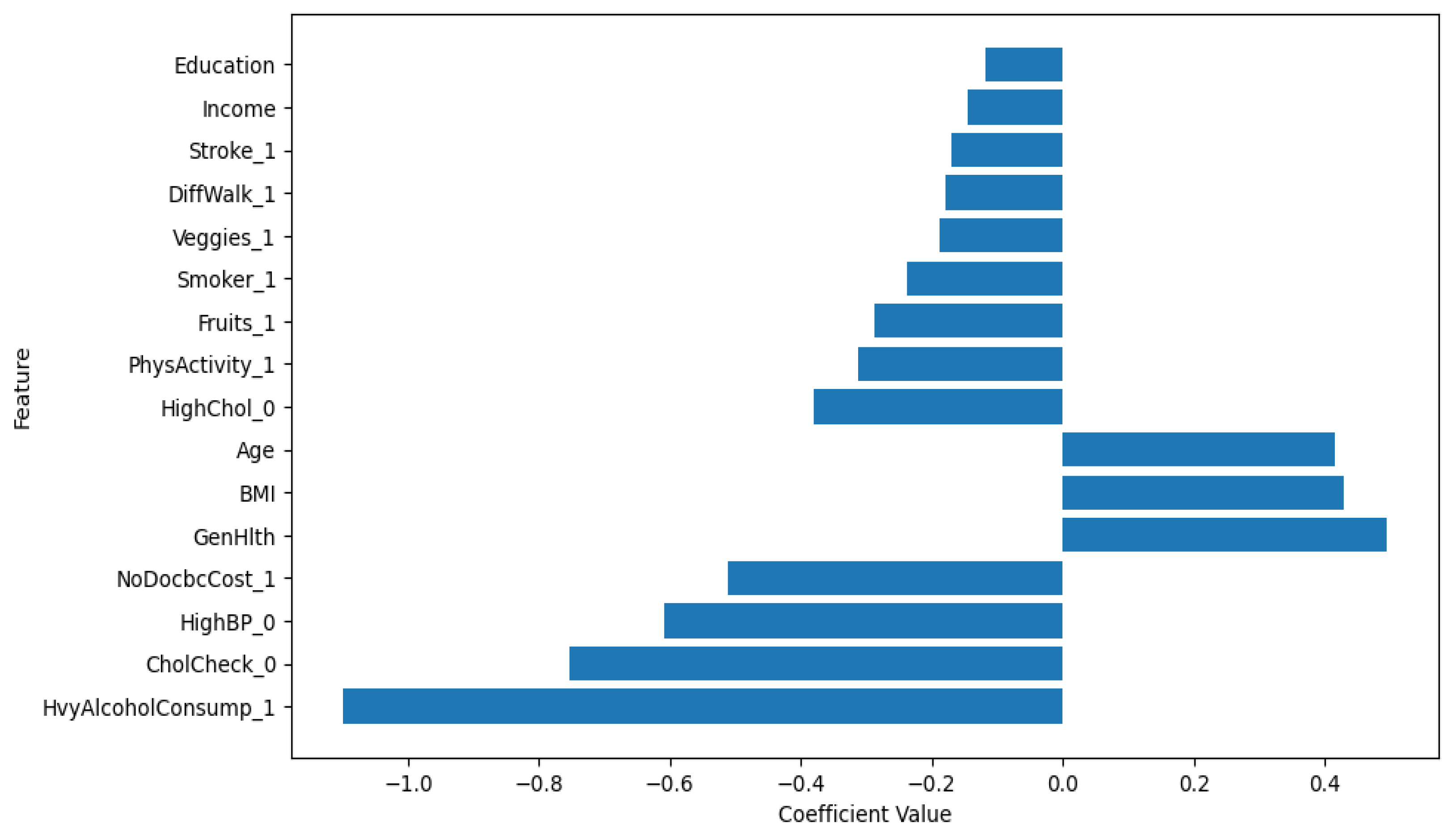

2.3. Logistic Regression with L1 Regularization

2.4. XGBoost

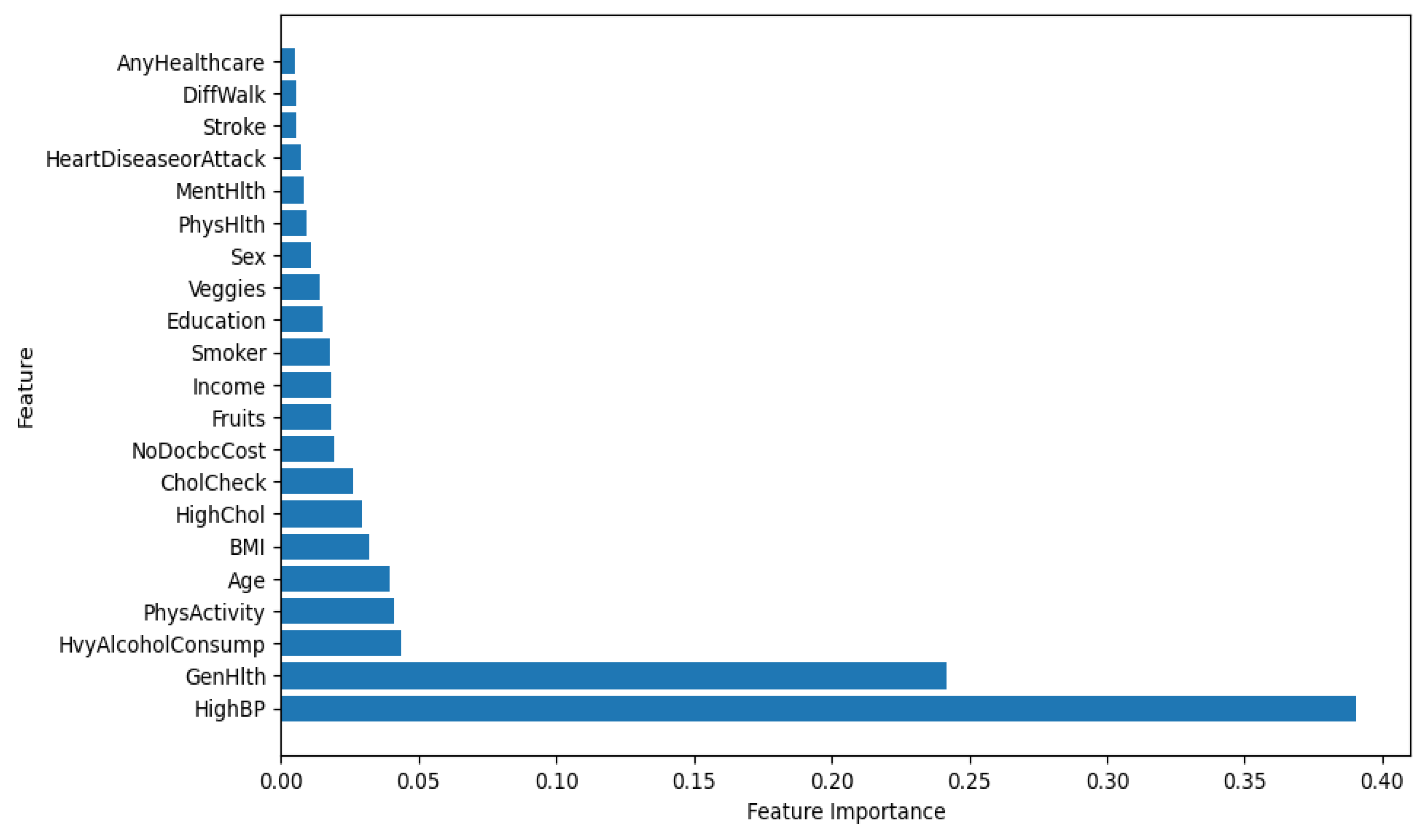

2.5. Random Forest

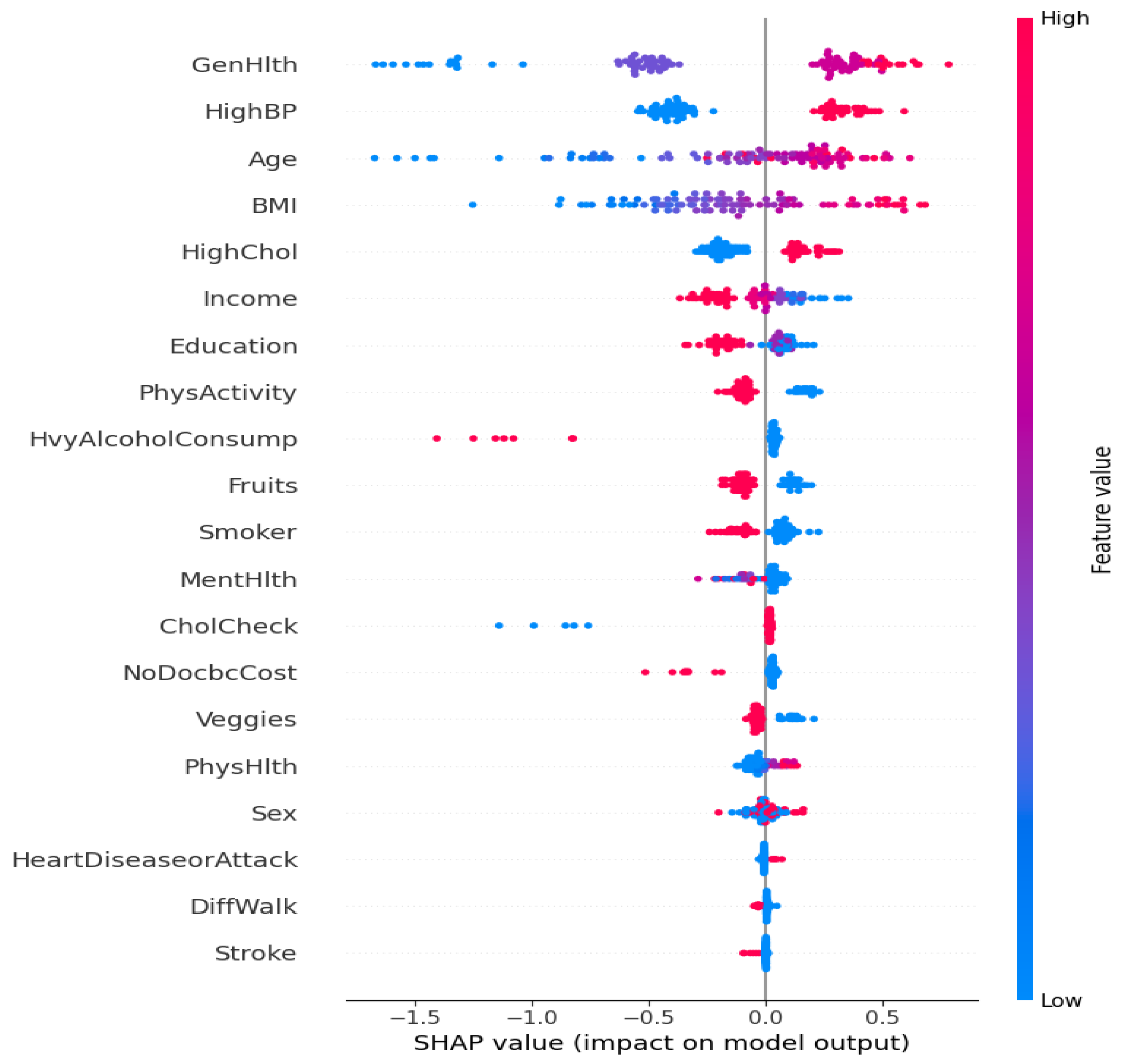

2.6. SHAP Model Interpretation

3. Results

3.1. Model Training

3.2. Model Performance Metrics

3.3. Model Interpretation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

References

- Y. Xie and et al, “Learning domain semantics and cross-domain correlations for paper recommendation,” in Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, ser. SIGIR ’21. Association for Computing Machinery, 2021, p. 706–715.

- Yukun Song, “Deep Learning Applications in the Medical Image Recognition,” American Journal of Computer Science and Technology, vol. 2, no. 2, p. 22, 2019.

- H. Ni, S. Meng, X. Geng, P. Li, Z. Li, X. Chen, X. Wang, and S. Zhang, “Time series modeling for heart rate prediction: From arima to transformers,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.12199, 2024.

- Y. Sun, Y. Duan, H. Gong, and M. Wang, “Learning low-dimensional state embeddings and metastable clusters from time series data,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, H. Wallach, H. Larochelle, A. Beygelzimer, F. d’Alché-Buc, E. Fox, and R. Garnett, Eds., vol. 32. Curran Associates, Inc., 2019.

- L. Wang, W. Xiao, and S. Ye, “Dynamic multi-label learning with multiple new labels,” Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 11903, pp. 399–409, 2019.

- J. Yang, J. Liu, Z. Yao, and C. Ma, “Measuring digitalization capabilities using machine learning,” Research in International Business and Finance, vol. 70, p. 102380, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Q. Z. Huili Zheng and et al, “Identification of prognostic biomarkers for stage iii non-small cell lung carcinoma in female nonsmokers using machine learning,” 2024.

- Z. Wang, Y. Zhu, Z. Li, Z. Wang, H. Qin, and X. Liu, “Graph neural network recommendation system for football formation,” Applied Science and Biotechnology Journal for Advanced Research, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 33–39, 2024.

- Q. Z. e. a. Yiru Gong, “Graphical Structural Learning of rs-fMRI data in Heavy Smokers,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.08395, 2024.

- Z. Lin, C. Wang, Z. Li, Z. Wang, X. Liu, and Y. Zhu, “Neural radiance fields convert 2d to 3d texture,” Applied Science and Biotechnology Journal for Advanced Research, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 40–44, 2024.

- H. Peng, R. Ran, Luo, and et al, “Lingcn: Structural linearized graph convolutional network for homomorphically encrypted inference,” in Thirty-seventh Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems.

- Y. Zhong, Y. Liu, E. Gao, C. Wei, Z. Wang, and C. Yan, “Deep learning solutions for pneumonia detection: Performance comparison of custom and transfer learning models,” medRxiv, pp. 2024–06, 2024.

- X. Fan, C. Tao, and J. Zhao, “Advanced stock price prediction with xlstm-based models: Improving long-term forecasting,” Preprints, 2024.

- X. Li and S. Liu, “Predicting 30-day hospital readmission in medicare patients: Insights from an lstm deep learning model,” medRxiv, 2024.

- C. Mao, S. Huang, M. Sui, H. Yang, and X. Wang, “Analysis and design of a personalized recommendation system based on a dynamic user interest model,” Advances in Computer, Signals and Systems, vol. 8, pp. 109–118, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhu and T. Hu, “Twitter sentiment analysis of covid vaccines,” in 2021 5th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Reality (AIVR), 2021, pp. 118–122.

- Z. Xie, O. Nikolayeva, J. Luo, and D. Li, “Building risk prediction models for type 2 diabetes using machine learning techniques,” Preventing Chronic Disease, vol. 16, p. 190109, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Song, P. Arora, S. T. Varadharajan, R. Singh, M. Haynes, and T. Starner, “Looking from a different angle: Placing head-worn displays near the nose,” in Proceedings of the Augmented Humans International Conference 2024, ser. AHs ’24. Association for Computing Machinery, 2024, p. 28–45.

- M. B. Mock, S. Zhang, and R. M. Summers, “Whole-cell rieske non-heme iron biocatalysts,” ser. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press, 2024.

- Z. Wu, X. Wang, S. Huang, H. Yang, D. Ma et al., “Research on prediction recommendation system based on improved markov model,” Advances in Computer, Signals and Systems, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 87–97, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Hu and et al, “Artificial intelligence aspect of transportation analysis using large scale systems,” in Proceedings of the 2023 6th Artificial Intelligence and Cloud Computing Conference, 2023, pp. 54–59.

- L. Wang, “Low-latency, high-throughput load balancing algorithms,” Journal of Computer Technology and Applied Mathematics, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 1–9, 2024.

- W. Q. Qimin Zhang and et al, “Cu-net: a u-net architecture for efficient brain-tumor segmentation on brats 2019 dataset,” 2024.

- Y. Tao and et al, “Nevlp: Noise-robust framework for efficient vision-language pre-training,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.09582, 2024.

- W. Zhu, “Optimizing distributed networking with big data scheduling and cloud computing,” in International Conference on Cloud Computing, Internet of Things, and Computer Applications (CICA 2022), vol. 12303. SPIE, 2022, pp. 23–28.

- Q. Z. Xinyu Shen and et al, “Harnessing XGBoost for robust biomarker selection of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) from adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) data,” in Fourth International Conference on Biomedicine and Bioinformatics Engineering (ICBBE 2024), P. P. Piccaluga, A. El-Hashash, and X. Guo, Eds., vol. 13252, International Society for Optics and Photonics. SPIE, 2024, p. 132520U.

- M. Wang and S. Liu, “Machine learning-based research on the adaptability of adolescents to online education,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.16849, 2024.

- X. Fan and C. Tao, “Towards resilient and efficient llms: A comparative study of efficiency, performance, and adversarial robustness,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.04585, 2024.

- Z. Ding, P. Li, Q. Yang, S. Li, and Q. Gong, “Regional style and color transfer,” in 2024 5th International Conference on Computer Vision, Image and Deep Learning (CVIDL). IEEE, 2024, pp. 593–597.

- Q. Yang, Z. Wang, S. Liu, and Z. Li, “Research on improved u-net based remote sensing image segmentation algorithm,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.12672, 2024.

- Z. Wang, H. Yan, C. Wei, J. Wang, S. Bo, and M. Xiao, “Research on autonomous driving decision-making strategies based deep reinforcement learning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.03084, 2024.

- H. Gao, H. Wang, Z. Feng, M. Fu, C. Ma, H. Pan, B. Xu, and N. Li, “A novel texture extraction method for the sedimentary structures’ classification of petroleum imaging logging,” in Pattern Recognition: 7th Chinese Conference, CCPR 2016, Chengdu, China, November 5-7, 2016, Proceedings, Part II 7. Springer, 2016, pp. 161–172.

- C. Tao and et al, “Harnessing llms for api interactions: A framework for classification and synthetic data generation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.11703, 2024.

- Y. Gu, D. Wang, and et al, “Green building material with superior thermal insulation and energy storage properties fabricated by paraffin and foam cement composite,” Construction and Building Materials, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Yang, C. Ma, D. Li, and J. Liu, “Mapping the knowledge onblockchain technology in the fieldof business and management: A bibliometric analysis,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 60 585–60 596, 2022.

- Y. Gu, Y. Li, Ju, and et al, “Pcm microcapsules applicable foam to improve the properties of thermal insulation and energy storage for cement-based material,” Construction and Building Materials, 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Yang and et al, “Retargeting destinations of passive props for enhancing haptic feedback in virtual reality,” in 2022 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW). IEEE, 2022, pp. 618–619.

- Y. Kang, Z. Zhang, M. Zhao, X. Yang, and X. Yang, “Tie memories to e-souvenirs: Hybrid tangible ar souvenirs in the museum,” in Adjunct Proceedings of the 35th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, 2022, pp. 1–3.

- Y. Zhu, C. Honnet, Y. Kang, J. Zhu, A. J. Zheng, K. Heinz, G. Tang, L. Musk, M. Wessely, and S. Mueller, “Demonstration of chromocloth: Re-programmable multi-color textures through flexible and portable light source,” in Adjunct Proceedings of the 36th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, 2023, pp. 1–3.

- Y. Kang, Y. Xu, C. P. Chen, G. Li, and Z. Cheng, “6: Simultaneous tracking, tagging and mapping for augmented reality,” in SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers, vol. 52. Wiley Online Library, 2021, pp. 31–33.

- S. H. Jinglan Yang, Chaoqun Ma and J. Liu, “Blockchain governance: a bibliometric study and content analysis,” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, vol. 0, no. 0, pp. 1–15, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Gong and M. Wang, “A duality approach for regret minimization in average-award ergodic markov decision processes,” in Proceedings of the 2nd Conference on Learning for Dynamics and Control, ser. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, A. M. Bayen, A. Jadbabaie, G. Pappas, P. A. Parrilo, B. Recht, C. Tomlin, and M. Zeilinger, Eds., vol. 120. PMLR, 2020, pp. 862–883.

- Y. Song, P. Arora, R. Singh, S. T. Varadharajan, M. Haynes, and T. Starner, “Going Blank Comfortably: Positioning Monocular Head-Worn Displays When They are Inactive,” in Proceedings of the 2023 International Symposium on Wearable Computers. ACM, 2023, pp. 114–118.

| Model | AUC | F1-score | Accuracy | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | 0.81 | 0.84 | 86% | 0.83 | 0.86 |

| XGBoost | 0.83 | 0.76 | 80% | 0.87 | 0.72 |

| Random Forest | 0.80 | 0.83 | 86% | 0.83 | 0.86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).