Submitted:

16 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Basic Clinical Characteristics

2.2. Concentration of MMPs, TNF-a and VEGF in Plasma

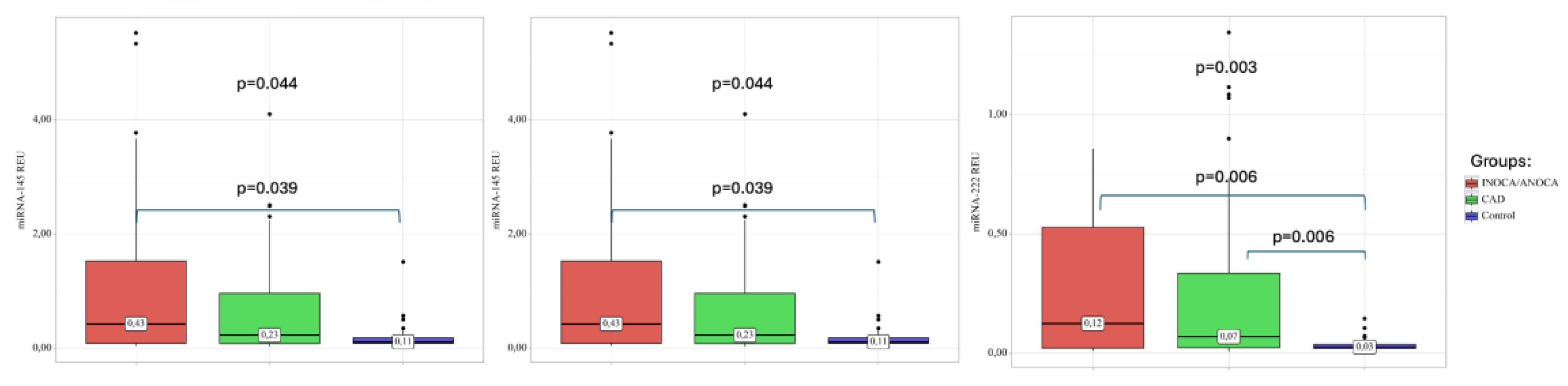

2.3. MiRNA Expression in Plasma of Patients with CAD

2.4. Correlations of VEGF, TNF-α and MMPs with Circulating miRNAs

3. Discussion

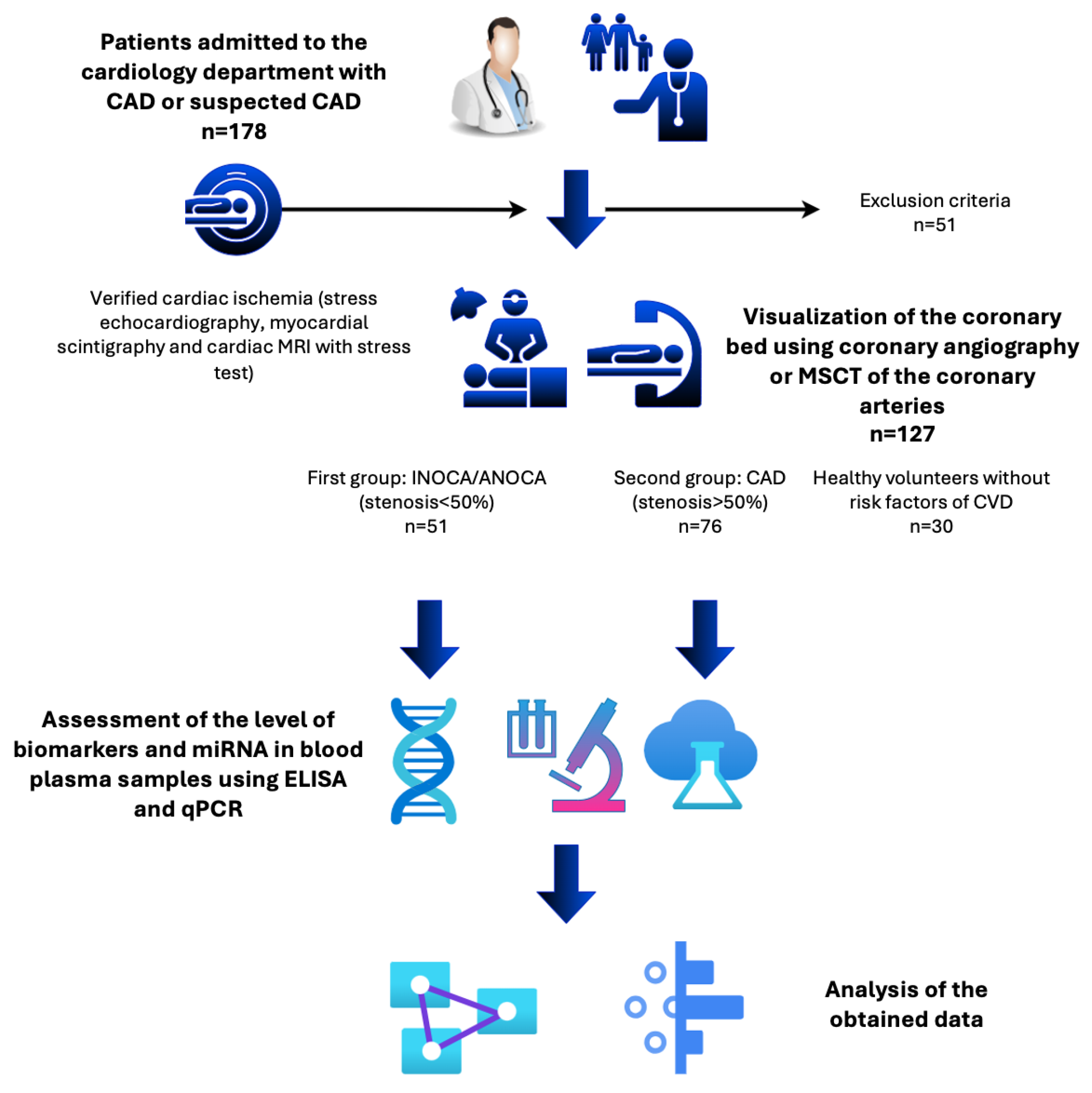

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patient Population

4.2. Collection of Blood Samples and ELISA

4.3. RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) Assay

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ralapanawa, U.; Sivakanesan, R. Epidemiology and the Magnitude of Coronary Artery Disease and Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Narrative Review. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2021, 11, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.; Fatumo, S.; Nitsch, D. Mendelian Randomization Studies on Coronary Artery Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Syst Rev 2024, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, H.R.; Diaz, A.; Cyr, D.D.; Shaw, L.J.; Mancini, G.B.J.; Leipsic, J.; Budoff, M.J.; Min, J.K.; Hague, C.J.; Berman, D.S.; et al. Ischemia With Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries: Insights From the ISCHEMIA Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2023, 16, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepine, C.J.; Ferdinand, K.C.; Shaw, L.J.; Light-McGroary, K.A.; Shah, R.U.; Gulati, M.; Duvernoy, C.; Walsh, M.N.; Bairey Merz, C.N. Emergence of Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Woman’s Problem and Need for Change in Definition on Angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015, 66, 1918–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileva, N.; Nagumo, S.; Mizukami, T.; Sonck, J.; Berry, C.; Gallinoro, E.; Monizzi, G.; Candreva, A.; Munhoz, D.; Vassilev, D.; et al. Prevalence of Coronary Microvascular Disease and Coronary Vasospasm in Patients With Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2022, 11, e023207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Kang, N.; Chung, J.; Gupta, A.R.; Parwani, P. Evaluation of Ischemia with No Obstructive Coronary Arteries (INOCA) and Contemporary Applications of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR). Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, L.; Hvelplund, A.; Abildstrøm, S.Z.; Pedersen, F.; Galatius, S.; Madsen, J.K.; Jørgensen, E.; Kelbæk, H.; Prescott, E. Stable Angina Pectoris with No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease Is Associated with Increased Risks of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events. Eur Heart J 2012, 33, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakayali, M.; Altunova, M.; Yakisan, T.; Aslan, S.; Omar, T.; Artac, I.; Ilis, D.; Arslan, A.; Cagin, Z.; Karabag, Y.; et al. The Relationship between the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index and Ischemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries in Patients Undergoing Coronary Angiography. Arq Bras Cardiol 2024, 121, e20230540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-D.; Wen, Z.-G.; Long, J.-J.; Wang, Y. Association Between Systemic Inflammation Response Index and Slow Coronary Flow Phenomenon in Patients with Ischemia and No Obstructive Coronary Arteries. Int J Gen Med 2024, 17, 4045–4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, C.; Richardson, K.P.; Tran, P.M.H.; Satter, K.B.; Hopkins, D.; Gardiner, M.; Sharma, A.; Purohit, S. Multiplex Analysis of Inflammatory Proteins Associated with Risk of Coronary Artery Disease in Type-1 Diabetes Patients. Clin Cardiol 2024, 47, e24143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Ecker, M. Overview of MMP-13 as a Promising Target for the Treatment of Osteoarthritis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Carracedo, R.; Hernández, I.; Moreno-Gómez-Toledano, R.; Díez-Mata, J.; Tesoro, L.; González-Cucharero, C.; Jiménez-Guirado, B.; Alcharani, N.; Botana, L.; Saura, M.; et al. NOS3 Prevents MMP-9, and MMP-13 Induced Extracellular Matrix Proteolytic Degradation through Specific MicroRNA-Targeted Expression of Extracellular Matrix Metalloproteinase Inducer in Hypertension-Related Atherosclerosis. J Hypertens 2024, 42, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, W.C.; Shapiro, S.D. Matrix Metalloproteinases in Lung Biology. Respir Res 2001, 2, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hey, S.; Linder, S. Matrix Metalloproteinases at a Glance. J Cell Sci 2024, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Carracedo, R.; Tesoro, L.; Hernandez, I.; Diez-Mata, J.; Filice, M.; Toro, R.; Rodriguez-Piñero, M.; Zamorano, J.L.; Saura, M.; Zaragoza, C. Non-Invasive Detection of Extracellular Matrix Metalloproteinase Inducer EMMPRIN, a New Therapeutic Target against Atherosclerosis, Inhibited by Endothelial Nitric Oxide. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitrias, P.; Metzinger-Le Meuth, V.; Nader, J.; Reix, T.; Caus, T.; Metzinger, L. The Involvement of MiRNA in Carotid-Related Stroke. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017, 37, 1608–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchler, A.; Munch, M.; Farber, G.; Zhao, X.; Al-Haddad, R.; Farber, E.; Rotstein, B.H. Selective Imaging of Matrix Metalloproteinase-13 to Detect Extracellular Matrix Remodeling in Atherosclerotic Lesions. Mol Imaging Biol 2022, 24, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrke, M.; Greif, M.; Broedl, U.C.; Lebherz, C.; Laubender, R.P.; Becker, A.; von Ziegler, F.; Tittus, J.; Reiser, M.; Becker, C.; et al. MMP-1 Serum Levels Predict Coronary Atherosclerosis in Humans. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2009, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, S.; Hu, D.-Q.; Zhao, M.; Ichimura, S.; Barnes, E.A.; Cornfield, D.N.; Alejandre Alcázar, M.A.; Spiekerkoetter, E.; Fajardo, G.; Bernstein, D. MicroRNA-34a-Dependent Attenuation of Angiogenesis in Right Ventricular Failure. J Am Heart Assoc 2024, 13, e029427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kim, Y.-R.; Vikram, A.; Kumar, S.; Kassan, M.; Gabani, M.; Lee, S.K.; Jacobs, J.S.; Irani, K. P66Shc-Induced MicroRNA-34a Causes Diabetic Endothelial Dysfunction by Downregulating Sirtuin1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2016, 36, 2394–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liang, W.; Tian, Y.; Ma, F.; Huang, W.; Jia, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, H. Inhibition of P53/MiR-34a Improves Diabetic Endothelial Dysfunction via Activation of SIRT1. J Cell Mol Med 2019, 23, 3538–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Sun, H.; Sun, B. MicroRNA-145 Is Involved in Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and Acts as a Promising Biomarker of Acute Coronary Syndrome. Eur J Med Res 2020, 25, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, B.; Cao, Y.; Yang, H.; Xiao, B.; Lu, Z. MicroRNA-221/222 Regulate Ox-LDL-Induced Endothelial Apoptosis via Ets-1/P21 Inhibition. Mol Cell Biochem 2015, 405, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couffinhal, T.; Kearney, M.; Witzenbichler, B.; Chen, D.; Murohara, T.; Losordo, D.W.; Symes, J.; Isner, J.M. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor/Vascular Permeability Factor (VEGF/VPF) in Normal and Atherosclerotic Human Arteries. Am J Pathol 1997, 150, 1673–1685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; Liu, X.Q.; Song, Y.; Zhai, C.G.; Xu, X.L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. Fibroblast Growth Factor-2/Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Enhances Atherosclerotic Plaque Stability. J Cell Mol Med 2020, 24, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowiak, K.; Bartkowiak, M.; Jankowska-Steifer, E.; Ratajska, A.; Kujawa, M.; Aniołek, O.; Niderla-Bielińska, J. Metabolic Syndrome and Cardiac Vessel Remodeling Associated with Vessel Rarefaction: A Possible Underlying Mechanism May Result from a Poor Angiogenic Response to Altered VEGF Signaling Pathways. J Vasc Res 2024, 61, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Egashira, K.; Inoue, S.; Usui, M.; Kitamoto, S.; Ni, W.; Ishibashi, M.; Hiasa Ki, K.; Ichiki, T.; Shibuya, M.; et al. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Is Necessary in the Development of Arteriosclerosis by Recruiting/Activating Monocytes in a Rat Model of Long-Term Inhibition of Nitric Oxide Synthesis. Circulation 2002, 105, 1110–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanni, A.; d’Aiello, A.; Pedicino, D.; Di Sario, M.; Vinci, R.; Ponzo, M.; Ciampi, P.; Lo Curto, D.; Conte, C.; Cribari, F.; et al. Molecular Hallmarks of Ischemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries: The “INOCA versus Obstructive CCS” Challenge. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pufe, T.; Harde, V.; Petersen, W.; Goldring, M.B.; Tillmann, B.; Mentlein, R. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) Induces Matrix Metalloproteinase Expression in Immortalized Chondrocytes. J Pathol 2004, 202, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillard, T.; Tesmenitsky, Y.; Croce, K.; Travers, R.; Shvartz, E.; Koskinas, K.C.; Sukhova, G.K.; Aikawa, E.; Aikawa, M.; Libby, P. Selective Inhibition of Matrix Metalloproteinase-13 Increases Collagen Content of Established Mouse Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011, 31, 2464–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaubatz, J.W.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Wasserman, B.A.; He, M.; Chambless, L.E.; Boerwinkle, E.; Hoogeveen, R.C. Association of Circulating Matrix Metalloproteinases with Carotid Artery Characteristics: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Carotid MRI Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010, 30, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonskaya, Y. V; Kashtanova, E. V; Murashov, I.S.; Striukova, E. V; Kurguzov, A. V; Stakhneva, E.M.; Shramko, V.S.; Maslatsov, N.A.; Chernyavsky, A.M.; Ragino, Y.I. Association of Matrix Metalloproteinases with Coronary Artery Calcification in Patients with CHD. J Pers Med 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarín, C.; Gomez, M.; Calvo, E.; López, J.A.; Zaragoza, C. Endothelial Nitric Oxide Deficiency Reduces MMP-13-Mediated Cleavage of ICAM-1 in Vascular Endothelium: A Role in Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2009, 29, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deguchi, J.-O.; Aikawa, E.; Libby, P.; Vachon, J.R.; Inada, M.; Krane, S.M.; Whittaker, P.; Aikawa, M. Matrix Metalloproteinase-13/Collagenase-3 Deletion Promotes Collagen Accumulation and Organization in Mouse Atherosclerotic Plaques. Circulation 2005, 112, 2708–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, E.O.; Dereke, J.; Hillman, M. Galectin-3, Metalloproteinase-2 and Cardiovascular Disease Were Independently Associated with Metalloproteinase-14 in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes: A Cross Sectional Study. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2021, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.L.; Jenkins, N.P.; Huang, W.-C.; Di Gregoli, K.; Sala-Newby, G.B.; Scholtes, V.P.W.; Moll, F.L.; Pasterkamp, G.; Newby, A.C. Relationship of MMP-14 and TIMP-3 Expression with Macrophage Activation and Human Atherosclerotic Plaque Vulnerability. Mediators Inflamm 2014, 2014, 276457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Thavarajah, T.; Gu, W.; Cai, J.; Xu, Q. Impact of MiRNA in Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2018, 38, e159–e170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, M.; Zhang, L.; You, F.; Zhou, J.; Ma, Y.; Yang, F.; Tao, L. MiR-145-5p Regulates Hypoxia-Induced Inflammatory Response and Apoptosis in Cardiomyocytes by Targeting CD40. Mol Cell Biochem 2017, 431, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zai, L.; Tao, Z.; Wu, D.; Lin, M.; Wan, J. MiR-145-5p Affects Autophagy by Targeting CaMKIIδ in Atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiol 2022, 360, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Priyadarshini, G.; Parameswaran, S.; Ramesh, A.; Rajappa, M. Evaluation of MicroRNA 145 and MicroRNA 155 as Markers of Cardiovascular Risk in Chronic Kidney Disease. Cureus 2024, 16, e66494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatsiou, A.; Georgiopoulos, G.; Vlachogiannis, N.I.; Pfisterer, L.; Fischer, A.; Sachse, M.; Laina, A.; Bonini, F.; Delialis, D.; Tual-Chalot, S.; et al. Additive Contribution of MicroRNA-34a/b/c to Human Arterial Ageing and Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2021, 327, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raitoharju, E.; Lyytikäinen, L.-P.; Levula, M.; Oksala, N.; Mennander, A.; Tarkka, M.; Klopp, N.; Illig, T.; Kähönen, M.; Karhunen, P.J.; et al. MiR-21, MiR-210, MiR-34a, and MiR-146a/b Are up-Regulated in Human Atherosclerotic Plaques in the Tampere Vascular Study. Atherosclerosis 2011, 219, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Qu, G.; Han, C.; Wang, Y.; Sun, T.; Li, F.; Wang, J.; Luo, S. MiR-34a, MiR-21 and MiR-23a as Potential Biomarkers for Coronary Artery Disease: A Pilot Microarray Study and Confirmation in a 32 Patient Cohort. Exp Mol Med 2015, 47, e138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Chen, S.; Liu, X.; Lin, L.; Huang, X.; Guo, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, W.; et al. Endothelial Enriched MicroRNAs Regulate Angiotensin II-Induced Endothelial Inflammation and Migration. Atherosclerosis 2011, 215, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Wei, Z.; Ding, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, D.; Liu, Y.; Zen, K.; et al. MicroRNA-19b/221/222 Induces Endothelial Cell Dysfunction via Suppression of PGC-1α in the Progression of Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2015, 241, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffont, B.; Rayner, K.J. MicroRNAs in the Pathobiology and Therapy of Atherosclerosis. Can J Cardiol 2017, 33, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karere, G.M.; Glenn, J.P.; Li, G.; Konar, A.; VandeBerg, J.L.; Cox, L.A. Potential MiRNA Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets for Early Atherosclerotic Lesions. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccini, J.; Ruidavets, J.-B.; Cordelier, P.; Martins, F.; Maoret, J.-J.; Bongard, V.; Ferrières, J.; Roncalli, J.; Elbaz, M.; Vindis, C. Circulating MiR-155, MiR-145 and Let-7c as Diagnostic Biomarkers of the Coronary Artery Disease. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 42916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O Sullivan, J.F.; Neylon, A.; McGorrian, C.; Blake, G.J. MiRNA-93-5p and Other MiRNAs as Predictors of Coronary Artery Disease and STEMI. Int J Cardiol 2016, 224, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, S.; Ding, H.; Wang, Y.; Qi, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Li, P. Clinical Significance of Circulating MicroRNAs as Diagnostic Biomarkers for Coronary Artery Disease. J Cell Mol Med 2020, 24, 1146–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, N.; Rojas, G.; Herrera, J.; Rebolledo, C.; Ruedlinger, J.; Bustos, L.; Bobadilla, B.; Pérez, L.; Saavedra, K.; Zambrano, T.; et al. Circulating MiRNA-23b and MiRNA-143 Are Potential Biomarkers for In-Stent Restenosis. Biomed Res Int 2020, 2020, 2509039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholipour, A.; Zahedmehr, A.; Arabian, M.; Shakerian, F.; Maleki, M.; Oveisee, M.; Malakootian, M. MiR-6721-5p as a Natural Regulator of Meta-VCL Is Upregulated in the Serum of Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Noncoding RNA Res 2025, 10, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busk, P.K. A Tool for Design of Primers for MicroRNA-Specific Quantitative RT-QPCR. BMC Bioinformatics 2014, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All CAD (n=127) |

INOCA/ANOCA (n=51) |

Obstructive CAD (n=76) |

Control (n=30) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (%) | 71(57.4) | 20 (39.2) | 51 (67.1) | 10 (33.3) | 0.001* p INOCA/ANOCA – obstructive CAD = 0.004 p obstructive CAD – Control = 0.003 |

| Women (%) | 56(42.6) | 31 (60.8) | 25 (32.9) | 20 (66.7) | |

| Age (year) | 64 [59; 71] | 64 [59; 70.5] |

63 [56; 71] |

28.5 [26; 39.2] |

< 0.001* p control – INOCA/ANOCA < 0.001 p control – obstructive CAD < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.9 [24.9; 29.8] | 26.20 [25.67; 30.40] | 27.4 [24.77; 29.75] | 21.95 [20.75; 25.23] | < 0.001* p control – INOCA/ANOCA < 0.001 p control – obstructive CAD < 0.001 |

| Smoking (%) | 9 (7.8) | 3 (7.7) | 6 (7.9) | - | 0.953 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 142 [133;152] | 142 [134;151] | 144 [133;152] | 136 [129;152] | 0.459 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.5 [5.17;5.8] | 5.53 [5.25; 5.81] | 5.43 [5.31; 5.54] | 4.9 [4.67; 5.35] | 0.005* pINOCA/ANOCA – Control = 0.011 pobstructive CAD – Control = 0.007 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 89 [78.2;99.2] | 80.45 [72.08; 91.67] | 91.5 [81; 101.32] | 82 [77.7; 87] | 0.009* p INOCA/ANOCA – obstructive CAD = 0.023 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.39[3.34; 4.77] | 4.45 [3.49; 5.36] | 3.79 [3.25; 4.36] | 4.94 [4.39; 5.52] | <0.001* p INOCA/ANOCA – obstructive CAD = 0.015 p obstructive CAD – Control < 0.001 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.36 [1.85; 2.97] | 2.72 [2.03; 3.2] | 2.16 [1.58; 2.55] | 2.54 [2.28; 3.21] | 0.006* p obstructive CAD – INOCA/ANOCA = 0.016 p control – obstructive CAD = 0.044 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.17 [1.04; 1.35] | 1.31 [1.03; 1.46] | 1.08 [1.08; 1.32] | 1.62 [1.35; 1.9] | <0.001* p control – INOCA/ANOCA = 0.021 p control – obstructive CAD < 0.001 |

| INOCA/ANOCA | obstructive CAD | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACE inhibitors | 18 (35.3) | 47 (61.8) | 0.027* |

| ARB II | 17(33.3) | 20 (26.7) | 0.123 |

| Beta-blocker | 26 (86.7) | 53 (81.5) | 0.535 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 16 (53.3) | 24 (36.9) | 0.33 |

| Antiaggregants | 26 (66.7) | 62 (81.5) | 0.202 |

| Anticoagulants | 4 (10.2) | 7 (9.2) | 0.738 |

| Antiarrhythmic drugs | 3 (7.7) | 8 (10.5) | 1.000 |

| HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors | 29 (74.4) | 63 (82.9) | 0.539 |

| Proteins | Groups | Concentration (Me [Q1 – Q3]) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF, ng/ml | INOCA/ANOCA | 41.66 [36.23 – 47.58] | 0.043* p INOCA/ANOCA – control = 0.036 |

| Obstructive CAD | 36.4 [13.12 – 66.05] | ||

| Control | 35.03 [10.50 – 41.62] | ||

| TNF-α, ng/ml | INOCA/ANOCA | 28.33 [13.97 – 29.74] | < 0.004* p control – obstructive CAD = 0.037 p INOCA/ANOCA– obstructive CAD = 0.03 |

| Obstructive CAD | 13.85 [10.76 – 25.30] | ||

| Control | 28.23 [14.17 – 28.73] | ||

| MMP-1, ng/ml | INOCA/ANOCA | 0.21 [0.17 – 0.29] | 0.161 |

| Obstructive CAD | 0.23 [0.21 – 0.23] | ||

| Control | 0.24 [0.22 – 0.32] | ||

| MMP-9 ng/ml | INOCA/ANOCA | 3.58 [1.98 – 6.18] | < 0.001* p obstructive CAD – INOCA/ANOCA < 0.001 |

| Obstructive CAD | 7.2 [4.25 – 10.68] | ||

| Control | 5.45 [4.02 – 6.81] | ||

| MMP-13, ng/ml | INOCA/ANOCA | 123.95 [68.85 – 285.43] | 0.055 |

| Obstructive CAD | 91.57 [49.77 – 339.51] | ||

| Control | 67.5 [47.79 – 111.30] | ||

| MMP-14, ng/ml | INOCA/ANOCA | 0.71 [0.29 – 1.04] | < 0.001* p obstructive CAD – control < 0.001 p control – INOCA = 0.02 |

| Obstructive CAD | 0.45 [0.26 – 0.78] | ||

| Control | 1.00 [0.75 – 1.31] |

| Factor/Predictor | B | Exp (B) [95%CI] | p | Pseudo R-squ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | -1,409 | 0.244 [0.094, 0.636] | p=0.004* | 0.080 |

| Smoking (n) | 0,063 | 1.064 [0.244, 4.641] | p=0.933 | 0.000 |

| Hypertension (n) | 0,138 | 1.147 [0.210, 6.28] | p=0.874 | 0.000 |

| Dyslipidemia (n) | 0,323 | 1.381 [0.138, 13.85] | p=0.784 | 0.001 |

| Angina pain (n) | 0,642 | 1.899 [0.629, 5.736] | p=0.255 | 0.012 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 0,018 | 1.018 [1.004, 1.033] | p=0.014* | 0.053 |

| Myocardial infarction (n) | -1,488 | 0.226 [0.077, 0.662] | p=0.007* | 0.073 |

| ACE inhibitors | -1,082 | 0.339 [0.138, 0.831] | p=0.018* | 0.049 |

| ARB II | 0,799 | 2.222 [0.876, 5.637] | p=0.093 | 0.024 |

| Beta blockers | 0,386 | 1.471 [0.432, 5.01] | p=0.536 | 0.003 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 0,669 | 1.952 [0.813, 4.691] | p=0.135 | 0.019 |

| Antiaggregant | -1,157 | 0.314 [0.066, 1.505] | p=0.148 | 0.018 |

| Statin | -0,776 | 0.460 [0.028, 7.619] | p=0.588 | 0.002 |

| Age (years) | 0,004 | 1.004 [0.953, 1.058] | p=0.871 | 0.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0,007 | 1.006 [0.903, 1.122] | p=0.905 | 0.000 |

| VEGF (ng/ml) | 0,000 | 1.000 [0.998, 1.001] | p=0.691 | 0.001 |

| TNF-a (ng/ml) | -0,002 | 0.998 [0.992, 1.004] | p=0.433 | 0.006 |

| MMP-1 (ng/ml) | -0,046 | 0.955 [0.587, 1.553] | p=0.853 | 0.000 |

| MMP-9 (ng/ml) | -0,044 | 0.957 [0.906, 1.011] | p=0.118 | 0.029 |

| MMP-13 (ng/ml) | 0,000 | 1.000 [1.000, 1.0] | p=0.972 | 0.000 |

| MMP-14 (ng/ml) | -0,025 | 0.975 [0.890, 1.07] | p=0.600 | 0.003 |

| miR-34a REU | -0,050 | 0.951 [0.869, 1.041] | p=0.274 | 0.010 |

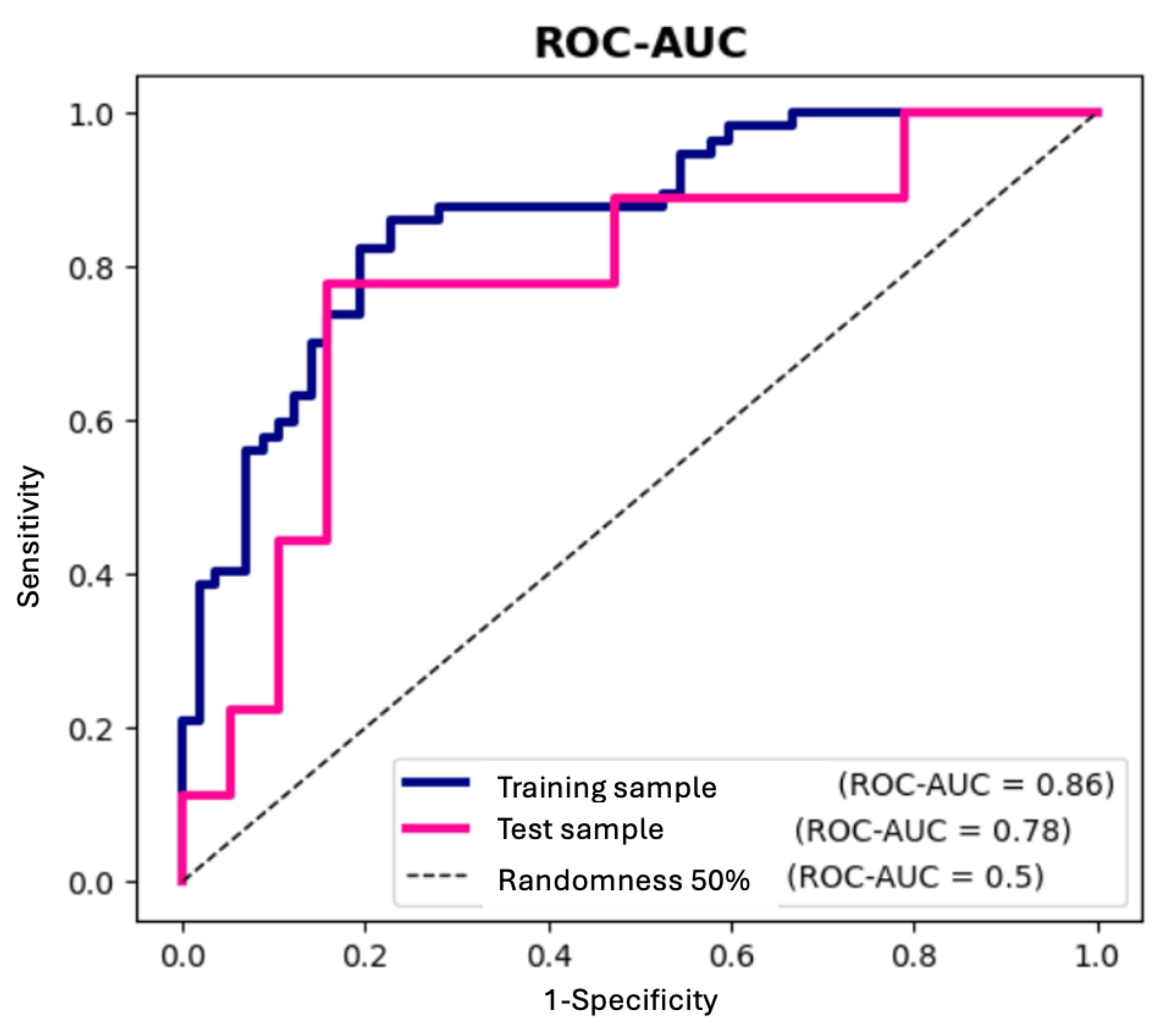

| miR-145 REU | 0,444 | 1.558 [1.066, 2.277] | p=0.022* | 0.042 |

| miR-222 REU | 0,458 | 1.581 [0.422, 5.93] | p=0.497 | 0.003 |

| Variables | coef (B) | Exp (B) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-145 REU | 0,921 | 2.512 [1.294, 4.875] | p=0.006* |

| Gender (male/female) | -1,116 | 0.328 [0.121, 0.889] | p=0.029* |

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| miR-34а | 5’- TGGCAGTGTCTTAGCTGGTTGT-3’ |

| miR-145 | 5’ - TCCAGTTTTCCCAGGAATCCCT - 3’ |

| miR-222 | 5’ - CTCAGTAGCCAGTGTAGATCCT - 3’ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).