3. Results and Discussion

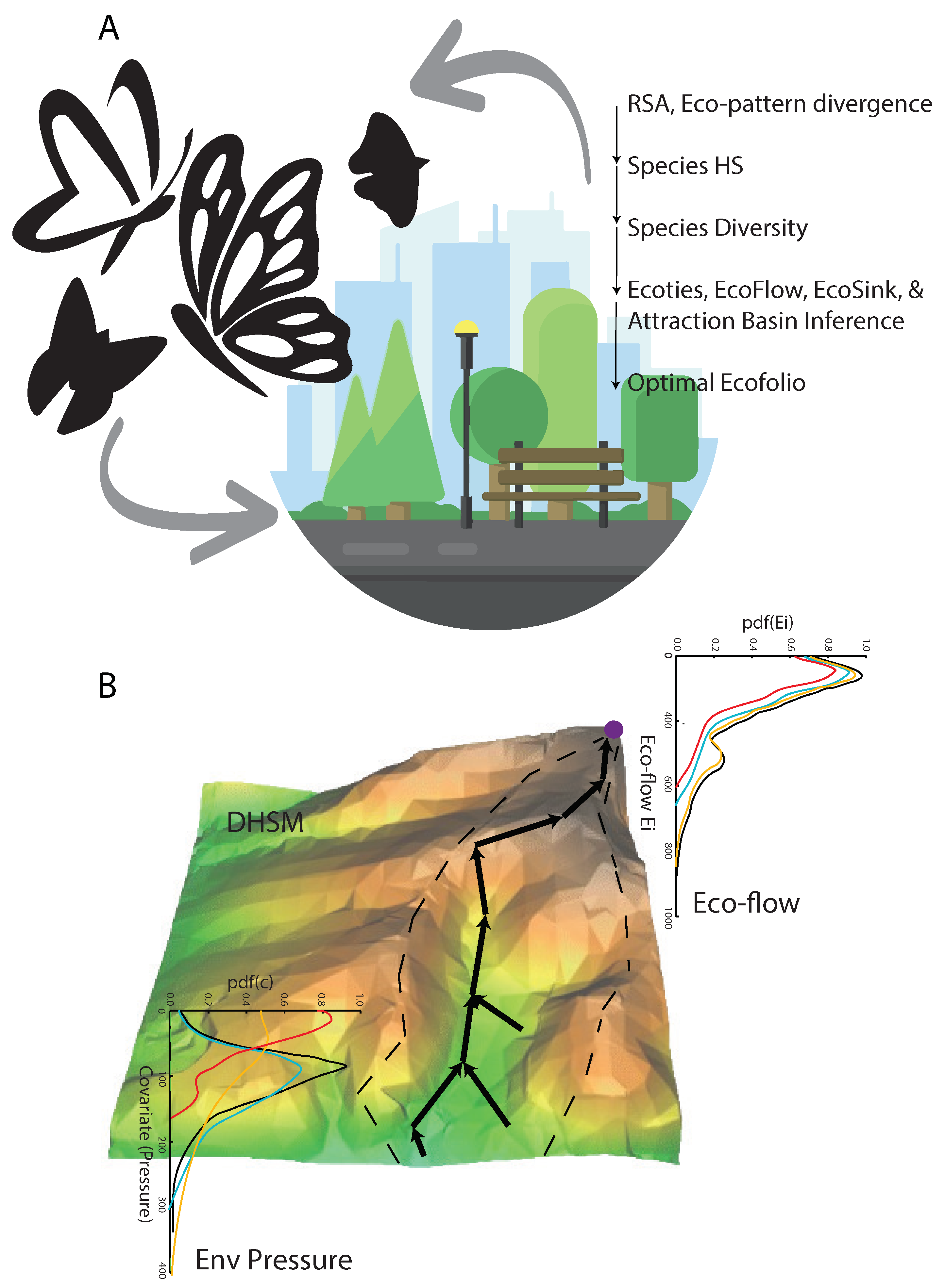

Butterfly phenomena are those where little shifts in one variable can lead to anomalous or extreme change (yet being informative) of another variable. In this framework we assume butterflies to change much more than the underlying environmental determinant such as climate and park variability. Yet, butterflies are a fingerprint of park fitness and response to climate pressure as well as, in a reverse causality perspective, very sensitive species to explore the impact of climate extremes to ecological communities in urban ecosystems. In

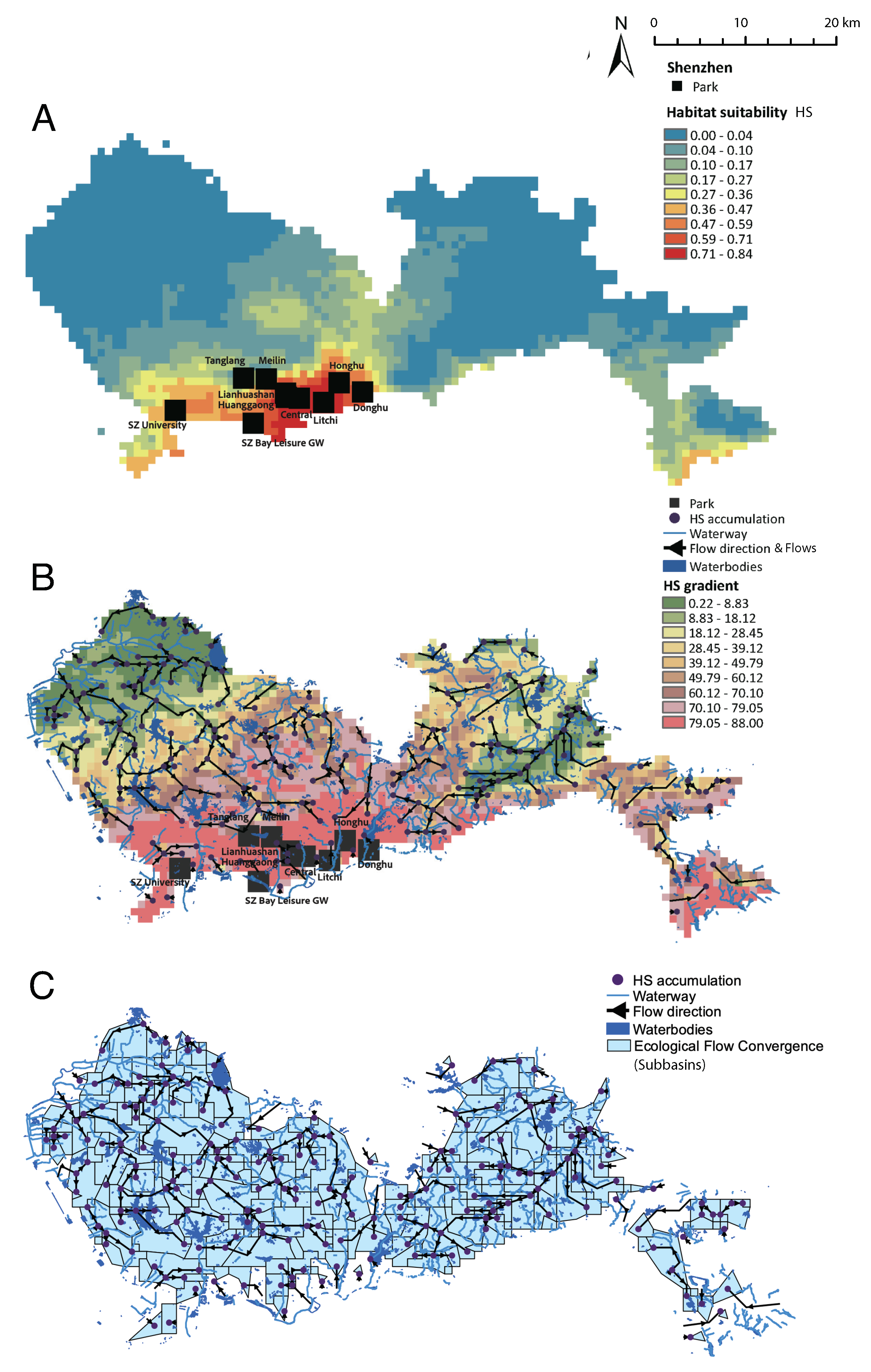

Figure 1 we show the main ideas about how eco-information, in this case of butterflies, can act as a barometer of ecosystem fitness such as of urban parks, and then address ecosystem design. Diversity is here intended as species richness, that is the number of species in a given area, vs. diversity accounting for abundance which is a disputed indicator defining maximum diversity for evenly distributed species.

Figure 1B shows the preferential pathways (as maximum gradients defined in Eq.

2) representing the convolution of compouding climate features onto species occurrence. Preferential flows (Eq.

3) are those with the highest predictability of HS across the ecosystems, yet the most important features species are sensitive to when moving in the landscape. The attraction basin of the network is identified by the positive curvature of HS areas. This framework can be used to define and assess ecological stress as a function of HS, gradient and accelleration.

The predicted HS and ecological flows are shown in Fig. 2A HS shows that the spatial predictability is very low, due to the extremely limited data over space, and concentrated in the historical core of the city, surprisingly. However, this is largely related also the monitoring bias that is highly concentrated into the core areas of the city where a variety of parks have been built. Another high HS area is in the East Dapeng area (red spot on the East side along the coastline) which is a natural area well maintained with very low development. The ecological flows in Fig. 2B, calculated as in Eq.

4 define five preferential pathways (with top 20% cumulated flows) that are relevant for butterflies and potentially other species, from low to high HS areas and pointing to major parks as attractors. The size of the cumulated flows is a measure of the importance/attractiveness of parks and it shows the speed of attractiveness based on the magnitude and rate of change of the HS gradient toward a point (that is the second derivative of HS over space). The purple points in Fig. 2B are connection points or final point of convergence of the prefential flows where the direction is from low to high HS along maxim gradients. The convergence of some of these purple points toward parks is a good indicator that parks act as connected ecological attractors; vice versa lack of convergence indicate a missing park or a corridor in the urban landscape considering the potential suitability driven by climate features. HS downscales climate pressure to the landscape where species are transformation functions. Then, HS is a Digital Ecological Model creating distributed maps of species from discrete occurrences, and flows allows us to trace routes of movement. Ranges of HS gradients identify areas of common dynamics, such the red and green high and low HS gradient in Fig. 2B. The former coincidens with high HS areas where parks are located, manifesting a high attractiveness for species and a confined existance of suitable communities. Outside of these areas a much lower suitability exists with likely minimum flow.

Attraction basins (eco-sinks or species basins) shown in Fig. 2C, defined by Eq.

5, are independent areas with similar eco-climatic niche including potential species movement. Inside each bains flows are converging and are independent as one network reflecting the accumlation of flows and divergence from other flows. The definition of these basins is really important for targeting areas of control and restoration.

Figure 2C also shows that the clustering of ecoflows (black lines) is quite high for a varity of standing waterbodies (reservoir and lakes) but few flows are coinciding with the hydrologic network (streams and rivers of different orders). Interestingly, for Shenzhen, the ecoflow network has much more extended scale-free connectivity and clustering for low HS gradient areas (green areas), populated by large reservoirs, that act as sources of ecological corridors ”draining” into urban parks with higher HS, higher HS gradients, and small-world connectivity that is not overlapping with hydrologic networks. This may signify an ecological opportunity to connect these areas via vegetated ecological corridors along water courses in the city; an effort that is undergoing in the city of Shenzhen [

25,

26]. In Fig. 2C it is also possible to note that the hydrologic network does not overlap much with urban parks, and that is a suboptimal condition and a potential cause for the anomaly of patterns like the Preston plot in centrally located parks. Ecology cannot exist properly without hydrology, therefore it is ideal to have a substantial overlap of eco- and hydro-flows. According to the Clapeyron’s law, a 1 degree Celsius increase in temperature results in approximately a 7% increase in the amount of evapotranspiration/water vapor the air can hold. Therefore, even just an increase of 1.5 degree Celsius could result in ∼ 9% more water in the atmosphere, which could have a major impact on local storm systems and subsequent rainfall. That is why restoring vegetated ecotones is critical not only for butterflies but for climate regulation about which butterflies can be excellent sentinels of change (e.g. of evapotranspiration).

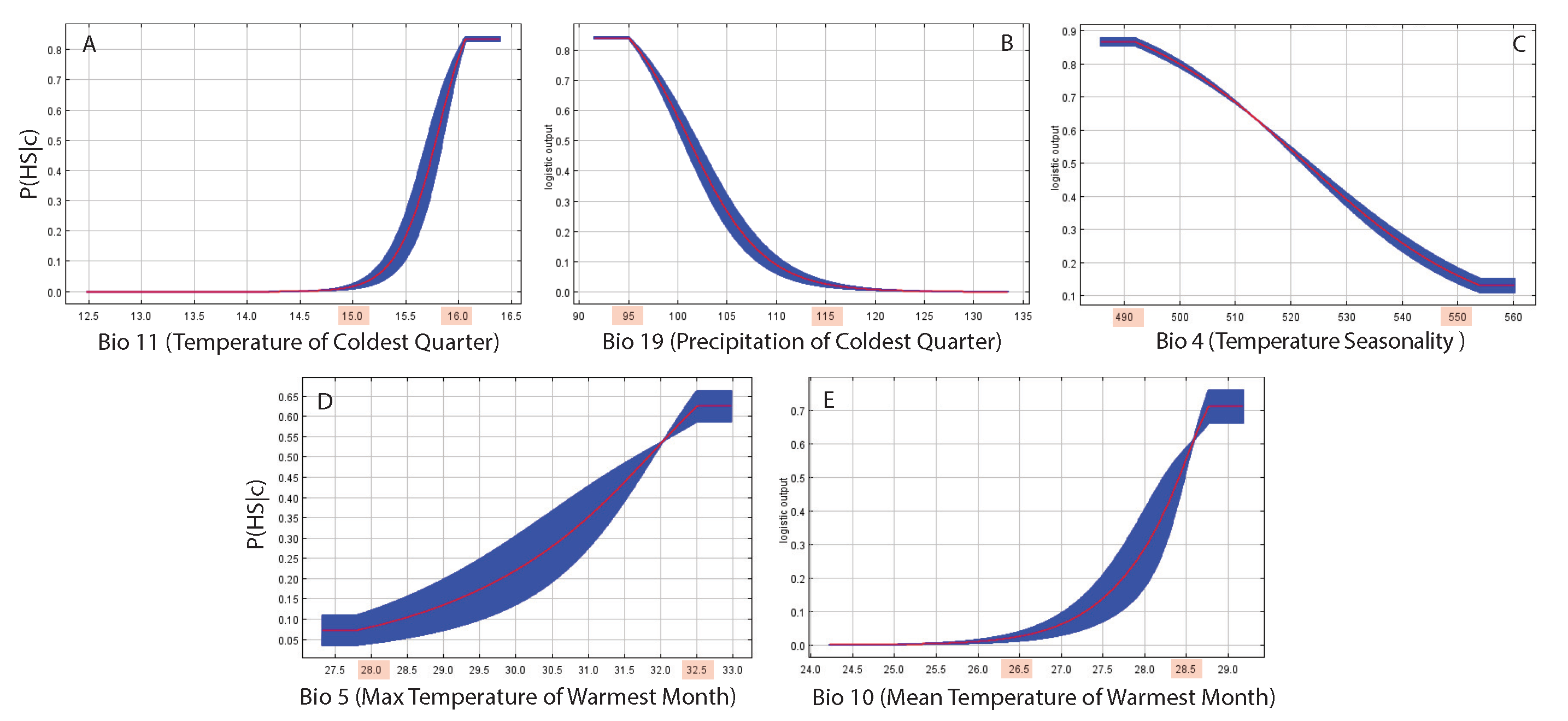

Figure 3 shows the response functions that are the HS probability conditional to hydroclimatological variables in isolation. We show the top five most important features whose non-linear interactions (as permutation importance in Table 2) predict the largest variability of HS. The response cuves values shaded in red are the tipping point of HS for the top five environmental determinants. Yet, those values lead to the largest changes in HS, where all transitions are of the second order, meaning they are gradual and not sudden. The most important variables, the Mean Temperature of Coldest Quarter (BIO11), and Precipitation of Coldest Quarter (BIO19) are increasing and decreasing HS gradually but quickly and determine the largest change in probability for HS. The importance of these climate variables is a reflection that butterflies are good sentinels of evapotranspiration. The associated response curves help to identify critical tipping points of temperature and precipitation that lead to major critical transitions, such as to .

The permutation importance of MaxEnt (Table 2) is based on directly disrupting the relationship between a feature and the target variable by randomly shuffling its values, while percentage contribution can be influenced by the optimization path taken during model training, making it potentially less consistent across different runs. permutation importance. This permutation importance depends only on the final MaxEnt model, not the path used to obtain it. The contribution for each variable is determined by randomly permuting the values of that variable among the training points (both presence and background) and measuring the resulting decrease in training AUC. A large decrease indicates that the model depends heavily on that variable. Values are normalized to give percentages. The percentage contribution depends on the path of the MaxEnt model and for highly correlated environmental variables, the percent contributions should be interpreted with caution. In order of importance considering permutation importance as high-order interactions, the key hydroclimatic factors in shaping HS are in order of importance: BIO11 = Mean Temperature of Coldest Quarter; BIO19 = Precipitation of Coldest Quarter; BIO4 = Temperature Seasonality (standard deviation ×100); BIO5 = Max Temperature of Warmest Month; and BIO10 = Mean Temperature of Warmest Quarter. Temperature and precipitation of the coldest quarter, and seasonality are the most important variables, underpinning the importance of critical features of the hydrologic cycle and its seasonal regularity. All these features are dramatically changing across the globe and yet compromising habitats and key species they support.

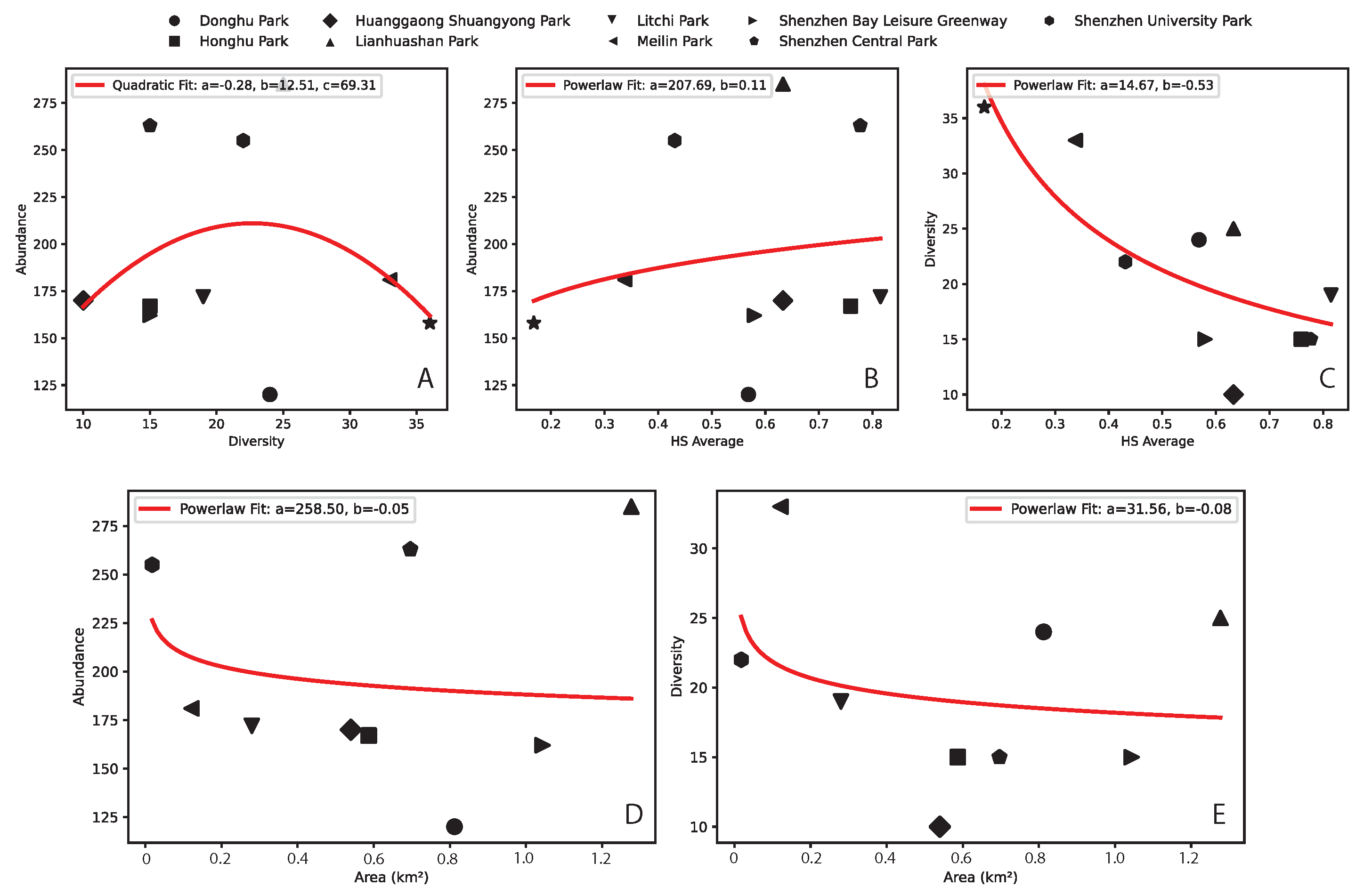

The relationship between abundance, diversity, and HS are shown in Fig. 4. Both abundance and diversity are mildy associated with park area according to a power function, unrelated to longitude but related to the degree of urbanization/park centrality (due to isolation in rich parks) counterintuitively. These two patterns are also showing trends that are not common in natural ecosystems where the species-are and abundance-area relationships are increasing non-linear functions. We also find: (i) a U-shape abundance-diversity pattern reflecting species heterogeneity and rarity of high diversity; (ii) and abundance and diversity increasing and decreasing as a power-law function with HS.

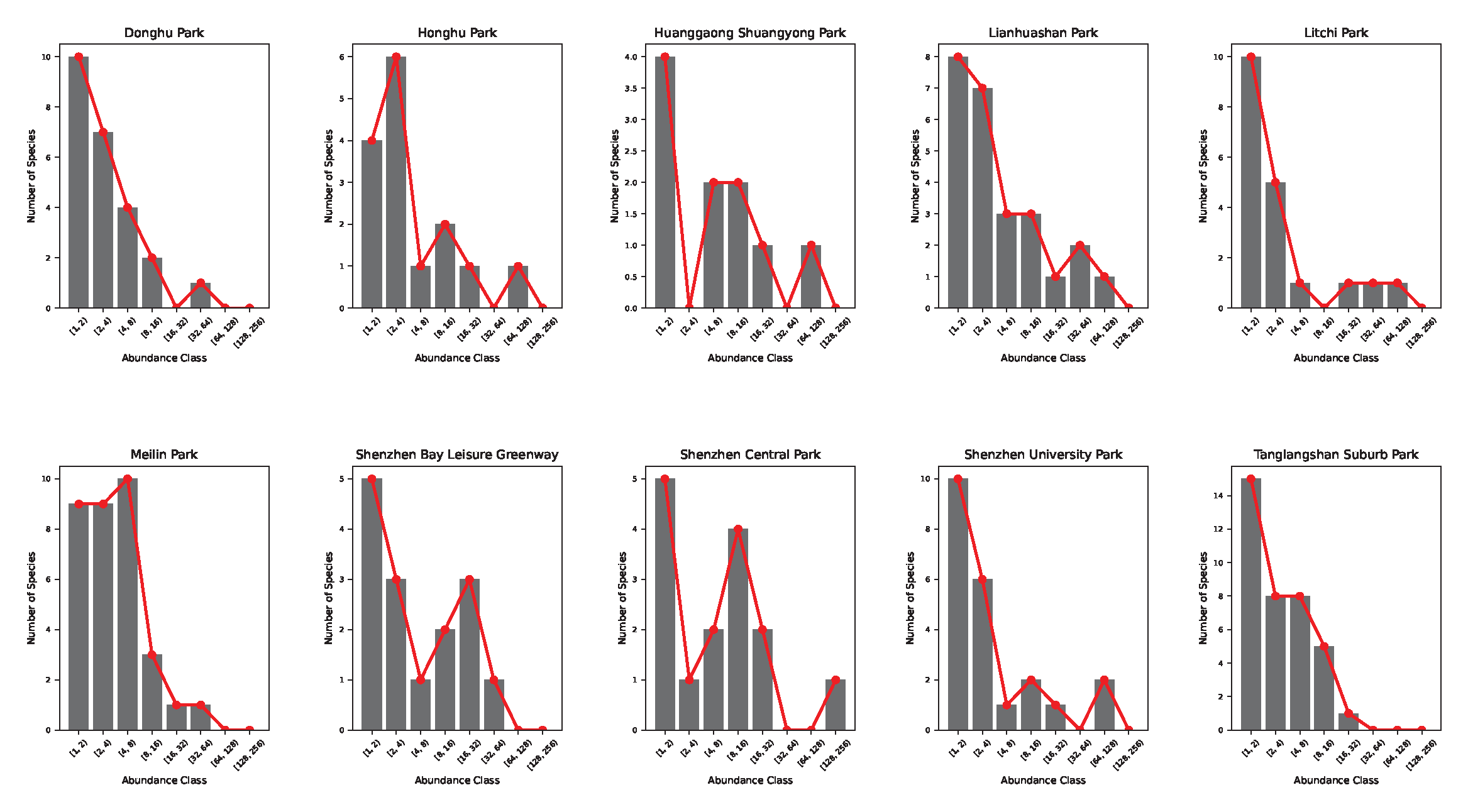

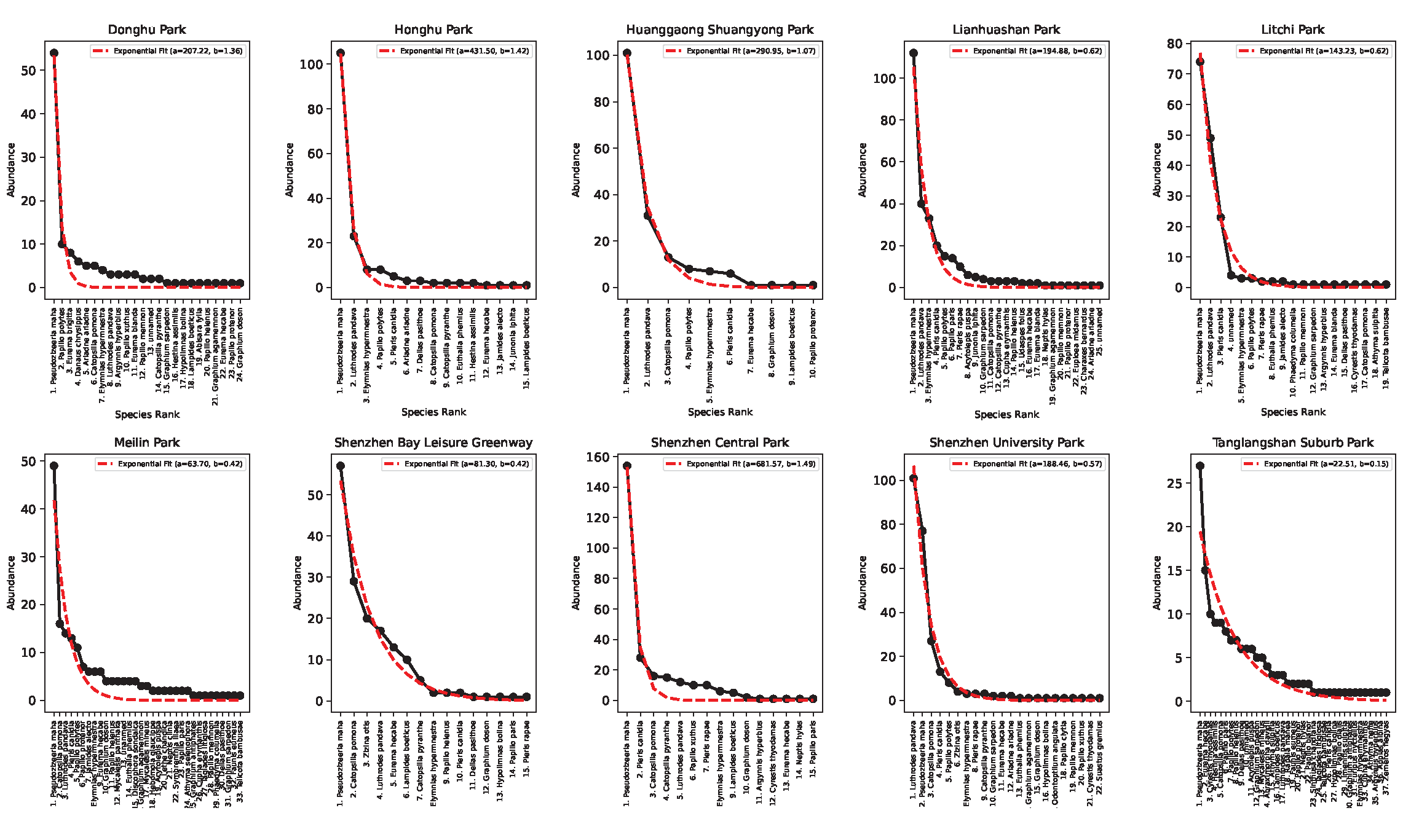

Figures 5 and 6 show the species-abundance Preston plots and the abundance-rank relationship for each park in Shenzhen. Ecological patterns such as the Preston plot and abundance rank can reflect the stationarity of ecological communities when they are lognormally or exponentially distributed per theoretical expectation reflecting an ideal distribution of species and abundance. However, the optimality of these patterns cannot be informative about the level of endemicity of parks, park proximity to change, and their relative connectivity.

Figure 2.

Butterfly habitat suitability, maximum gradient flows, and attraction basins. A. Habitat Suitability. B. Optimal Ecological Networks as stepeest gradients of HS after a threshold on the minimum flow. C. Attraction basins (eco-sinks) of converging flows with similar eco-climatic niche including potential species movement. Purple nodes are points where multiple connections exist and end points. Subbasins are nested areas with the whole ecosystems where one or more flows are jointly draining into one common point and any other flow cannot enter the subbasin.

Figure 2.

Butterfly habitat suitability, maximum gradient flows, and attraction basins. A. Habitat Suitability. B. Optimal Ecological Networks as stepeest gradients of HS after a threshold on the minimum flow. C. Attraction basins (eco-sinks) of converging flows with similar eco-climatic niche including potential species movement. Purple nodes are points where multiple connections exist and end points. Subbasins are nested areas with the whole ecosystems where one or more flows are jointly draining into one common point and any other flow cannot enter the subbasin.

Figure 3.

Response curves as environment-ecology patterns of top 5 climatic features. The response curves are the conditional probability of HS as a function of WorldClim hydroclimatological variables in Table 2. The response cuves shaded in red are for the top five environmental determinants for butterfly HS (as permutation importance in Table 2). BIO11 = Mean Temperature of Coldest Quarter; BIO19 = Precipitation of Coldest Quarter; BIO4 = Temperature Seasonality (standard deviation ×100); BIO5 = Max Temperature of Warmest Month; and BIO10 = Mean Temperature of Warmest Quarter. In red the critical tipping points for each climatic features are highlighted. The blue areas are related to variability of predicted HS when sampling the climatic features.

Figure 3.

Response curves as environment-ecology patterns of top 5 climatic features. The response curves are the conditional probability of HS as a function of WorldClim hydroclimatological variables in Table 2. The response cuves shaded in red are for the top five environmental determinants for butterfly HS (as permutation importance in Table 2). BIO11 = Mean Temperature of Coldest Quarter; BIO19 = Precipitation of Coldest Quarter; BIO4 = Temperature Seasonality (standard deviation ×100); BIO5 = Max Temperature of Warmest Month; and BIO10 = Mean Temperature of Warmest Quarter. In red the critical tipping points for each climatic features are highlighted. The blue areas are related to variability of predicted HS when sampling the climatic features.

Figure 4.

Butterfly abundance and diversity patterns as a function of habitat suitability and area. A, B and C are abundance-diversity, abudance-HS and diversity-area patterns. D and E are abundance- and diversity-area patterns.

Figure 4.

Butterfly abundance and diversity patterns as a function of habitat suitability and area. A, B and C are abundance-diversity, abudance-HS and diversity-area patterns. D and E are abundance- and diversity-area patterns.

Figure 5.

Butterfly Preston plots for Shenzhen parks. In black the raw-data histograms are shown and in red the interpolating function connecting the maximum values for each abundance class. Honghu, Huanggaong, Shenzhen Central, and Shenzhen Bay Parks show an anomalous bimodal species-abundance pattern reflecting the non-stationarity of butterfly communities (potentially indicative of all ecological communities).

Figure 5.

Butterfly Preston plots for Shenzhen parks. In black the raw-data histograms are shown and in red the interpolating function connecting the maximum values for each abundance class. Honghu, Huanggaong, Shenzhen Central, and Shenzhen Bay Parks show an anomalous bimodal species-abundance pattern reflecting the non-stationarity of butterfly communities (potentially indicative of all ecological communities).

Figure 6.

Species-abundance rank patterns for Shenzhen parks. Pseudozizeeria maha is the most abundant species for all parks (except for Shenzhen University Park). Papilio polytes and Luthrodes pandava are also very abundant but diversity of butterflies is quite distinct for each park.

Figure 6.

Species-abundance rank patterns for Shenzhen parks. Pseudozizeeria maha is the most abundant species for all parks (except for Shenzhen University Park). Papilio polytes and Luthrodes pandava are also very abundant but diversity of butterflies is quite distinct for each park.

4. Conclusions

The analysis of species distribution and diversity in urban ecosystems (i.e., cities considering all assets) should be a top priority for ecosystem fitness assessment and decision-making about management, restoration, and development. This is particularly important for planning the future under extreme changes. The consideration of ecological networks reflecting the collective dynamics of key species is a non-neglectable factor for assessing community function in relation to the physical environment. In particular, accounting for hydrosphere-related ecological flows defines how much modifications of water (in its multifaceted aspects) affect species, communities, and climate in an interconnected way as ecoties (species interactions, habitat interactions, and teleconnections) as an ecological portfolio [

22,

27]. Given this information a proactive ”bioterraforming” approach, that is eco-hydro-geomorphological engineering, should follow.

In this study we assessed how much HS affects population and community features such as abundance and diversity of butterfly populations taken as a potential barometer of ecosystem health. The case study has been done for Shenzhen, that is the fastest growing megalopoli in the world. In particular we found: (i) a U-shape abundance-diversity pattern reflecting species heterogeneity and rarity of high diversity; (ii) and abundance and diversity increasing and decreasing as a power-law function with HS. Diversity appears to be related to park area but abudance more to the degree of urbanization or park centrality due to the likely isolation of some species in these areas with higher species reporting. However, these central parks are characterized by bimodal Preston plots (richness-abundance patterns) that underlie some non-stationary and/or suboptimal conditions in species assemblage.

An important element is related to species richness that should not be used as a systemic indicator of ecosystem health nor of ecosystem conservation of natural conditions. This is observable very clearly in Shenzhen where the highest diversity and abundance, considering the butterfly data, is observed for urban parks that are quite central in the city; these parks have the largest urbanization pressure considering the evolution of the city: the oldest park are in the oldest parts of the city. Thus, other elements, such as the presence of exotic plants or ecological isolation may contribute to these high value of diversity. Ecosystem fitness then should be based on the topology of species interaction networks from relative Relative Species Abundance that can be easily assessed over space and time and should be structured along ecological corridors [

4,

27,

28]. A simpler alternative for baselining ecosystem fitness is to use HS of species like butterflies that are sensitive and sentinels (in the sense of vulnerability and early-warning signal) to the environmental footprint and representative of other species. Specifically, HS flows (OEN) are sentinels of changes due their strong dependencies with temperature and precipitation flows along hydrological corridors connecting land and atmosphere. Ecoflows incorporate species and species-tranformed climate pressure into a distribution reflecting compouding and distributed stress responses. Thus, flow distribution more than RSA is a sentinel of change manifesting the balance between climate forcing and species response. This perspective should be seen in an information sense where ecological information becomes intelligence for decision making on ecosystem management and design [

2,

22,

29]. Ecological information can support Digital Ecological Models providing community fitness, corridors, flows, areas of influence and environnmental determinants to manage or control.

As climate variability increases and global temperatures rise, communities face more frequent and severe events, such as hurricanes, heat waves, floods and droughts as compounding risks linked to the same ecohydrological dysbiosis [

29]. The need for ecosystem predictions, anchored into species infomation, allows stakeholders to support ecosystem planning, design and engineering that is critical for communities, ecosystems (natural and built environments together) and economies. Tracking species allow us to determine the signature of the hydrologic cycle that may be shifting, and yet to diagnose and plan ecosystems more properly than a non eco-informed scenario. Butterflies and other critically sensitive species act as fingerprints of ecosytsem function (or dysbiosis vice versa) driven by the balanced species-climate interactions structured by ecohydrological proportions.