Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Questions

What general information is included in the universities’ guidelines on the use of GenAI tools?

What instructions are provided in the universities’ guidelines covering the use of GenAI tools in academic activities?

What specific instructions regarding ethical and legal issues are offered in the universities’ guidelines on the use of GenAI tools?

2. Literature Review

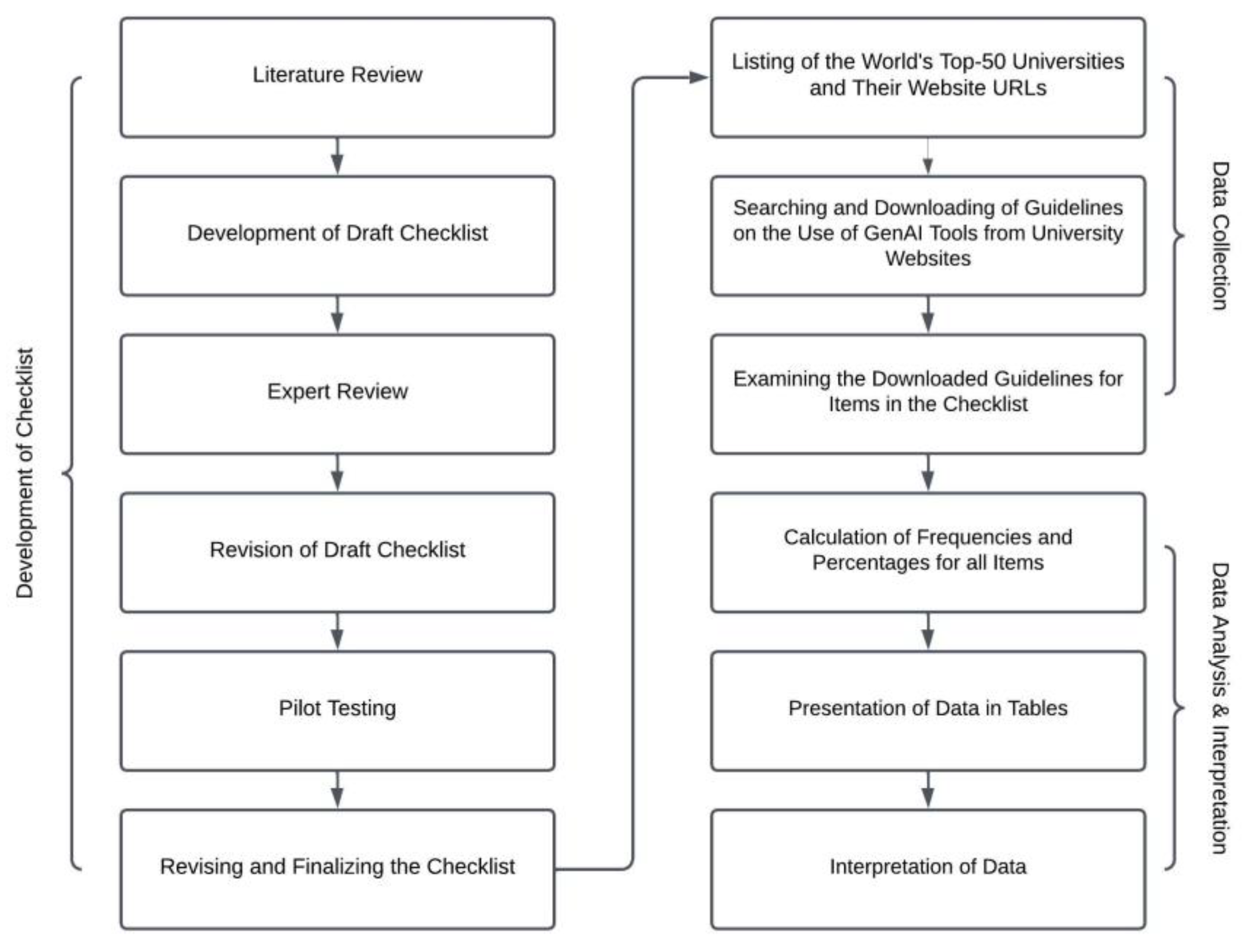

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. General Information Category

4.2. Instructions on the Use of GenAI Tools

4.3. Instructions Regarding Ethical and Legal Issues

5. Discussion

5.1. First Research Question

5.2. Second Research Question

5.3. Third Research Question

5.4. More Than Just Guidelines: A Complete Curriculum Rethink Will Become Necessary

6. Study Limitations

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Instrument for Assessing the Guidelines on the Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence Tools in Universities

| A. General Information | |||

| S. No. | Item | Yes | No. |

| 1 | Guidelines issuer authority | ||

| 2 | Release date | ||

| 3 | Objectives and scope of the guidelines | ||

| 4 | Introduction to GenAI tools | ||

| 5 | How does an AI algorithm work? | ||

| 6 | Examples of GenAI tools | ||

| 7 | Contact information for guidance | ||

| B. Instructions on the Use of GenAI | |||

| 8 | GenAI tools usage permitted | ||

| 9 | Domains for GenAI tools utilization | ||

| 10 | Instances unsuitable for GenAI tools usage (limitations) | ||

| 11 | Instructor approval for GenAI utilization | ||

| 12 | Details of GenAI tool employed (description/name/version/date) | ||

| 13 | Purpose of utilizing GenAI tools | ||

| 14 | Details of the provided prompts to the GenAI tool | ||

| 15 | Documentation of GenAI tool outputs | ||

| 16 | Utilization and adaptation of GenAI output | ||

| 17 | Strategies for use in classrooms and assessments | ||

| C. Instructions Regarding Ethical and Legal Issues | |||

| 18 | Data privacy and security | ||

| 19 | Evaluation and verification of GenAI outputs | ||

| 20 | Referencing and citing of GenAI outputs | ||

| 21 | Academic integrity and misconduct | ||

| 22 | Use of AI detection tools | ||

| 23 | Legal compliance | ||

| 24 | Reporting mechanisms | ||

Appendix B. List of the World’s Top 50 Universities and Their Corresponding Guidelines URLs (as Accessed in July/August 2024)

| University Name | Guidelines URL |

| Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, United States | https://ist.mit.edu/ai-guidance |

| Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom | https://www.imperial.ac.uk/admin-services/library/learning-support/generative-ai-guidance/ |

| University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom | https://communications.admin.ox.ac.uk/communications-resources/ai-guidance |

| Harvard University, Cambridge, United States | https://huit.harvard.edu/ai/guidelines |

| University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom | https://genai.uchicago.edu/about/generative-ai-guidance |

| Stanford University, Stanford, United States | https://uit.stanford.edu/security/responsibleai |

| ETH Zurich, Zürich, Switzerland | https://ethz.ch/en/the-eth-zurich/education/ai-in-education.html |

| National University of Singapore (NUS), Singapore | https://ctlt.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Policy-for-Use-of-AI-in-Teaching-and-Learning.pdf |

| University College London (UCL), London, United Kingdom | https://library-guides.ucl.ac.uk/generative-ai/acknowleding |

| California Institute of Technology (Caltech), Pasadena, United States | https://www.imss.caltech.edu/services/collaboration-storage-backups/caltech-ai/guidelines-for-secure-and-ethical-use-of-artificial-intelligence-ai |

| University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, United States | https://cetli.upenn.edu/resources/generative-ai-your-teaching/ |

| University of California (UC), Berkeley, United States | https://oercs.berkeley.edu/ai/appropriate-use-generative-ai-tools |

| The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia | https://www.unimelb.edu.au/generative-ai-taskforce/resources |

| Peking University, Beijing, China | No guidelines were found on the website https://english.pku.edu.cn/ as of August 30, 2024. |

| Nanyang Technological University, (NTU) Singapore | https://www.ntu.edu.sg/research/resources/use-of-gai-in-research |

| Cornell University, Ithaca, United States | https://it.cornell.edu/ai/ai-guidelines |

| The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China | https://innowings.engg.hku.hk/innowing1/aiguide/ |

| The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia | https://www.sydney.edu.au/students/academic-integrity/artificial-intelligence.html |

| The University of New South Wales (UNSW), Sydney, Australia | https://www.student.unsw.edu.au/notices/2024/05/ethical-and-responsible-use-artificial-intelligence-unsw |

| Tsinghua University, Beijing, China | No guidelines were found on the website https://www.tsinghua.edu.cn/en/ as of August 30, 2024. |

| University of Chicago, Chicago, United States | https://genai.uchicago.edu/about/generative-ai-guidance |

| Princeton University, Princeton, United States | https://mcgraw.princeton.edu/generative-ai |

| Yale University, New Haven, United States | https://provost.yale.edu/news/guidelines-use-generative-ai-tools |

| Université PSL, Paris, France | No guidelines were found on the website https://psl.eu/en as of August 30, 2024. |

| University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada | https://ai.utoronto.ca/guidelines/ |

| École Polytechnique, fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Switzerland | https://www.epfl.ch/about/vice-presidencies/vice-presidency-for-academic-affairs-vpa/tips-for-the-use-of-generative-ai-in-research-and-education/ |

| The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom | https://information-services.ed.ac.uk/computing/comms-and-collab/elm/guidance-for-working-with-generative-ai |

| Technical University of Munich (TUM), Munich, Germany | No guidelines were found on the website https://www.tum.de/en/ as of August 30, 2024. |

| McGill University, Montreal, Canada | https://www.mcgill.ca/stl/files/stl/stl_recommendations_2.pdf |

| Australian National University (ANU), Canberra, Australia | https://learningandteaching.anu.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Chat_GPT_FAQ-1.pdf |

| Seoul National University, Seoul, South Korea | No guidelines were found on the website https://en.snu.ac.kr/index.html as of August 30, 2024. |

| Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, United States | https://teaching.jhu.edu/university-teaching-policies/generative-ai/ |

| The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan | https://utelecon.adm.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/docs/ai-tools-in-classes |

| Columbia University, New York City, United States | https://provost.columbia.edu/content/office-senior-vice-provost/ai-policy |

| The University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom | https://www.staffnet.manchester.ac.uk/dcmsr/communications/ai-guidelines/ |

| The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), Hong Kong, China | https://www.aqs.cuhk.edu.hk/documents/A-guide-for-students_use-of-AI-tools.pdf |

| Monash University, Melbourne, Australia | https://www.monash.edu/graduate-research/support-and-resources/resources/guidance-on-generative-ai |

| University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada | https://genai.ubc.ca/guidance/ |

| Fudan University, Shanghai, China | No guidelines were found on the website https://www.fudan.edu.cn/en/ as of August 30, 2024. |

| King’s College London, London, United Kingdom | https://www.kcl.ac.uk/about/strategy/learning-and-teaching/ai-guidance/student-guidance |

| The University of Queensland, Brisbane City, Australia | https://itali.uq.edu.au/teaching-guidance/teaching-learning-and-assessment-generative-ai |

| University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, United States | https://genai.ucla.edu/guiding-principles-responsible-use |

| New York University (NYU), New York City, United States | https://www.nyu.edu/faculty/teaching-and-learning-resources/Student-Learning-with-Generative-AI.html |

| University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, Ann Arbor, United States | https://lsa.umich.edu/technology-services/services/learning-teaching-consulting/teaching-strategies/Guidelines-for-Using-Generative-Artificial-Intelligence.html |

| Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China | https://global.sjtu.edu.cn/en/news/view/1520 |

| Institut Polytechnique de Paris, Palaiseau Cedex, France | No guidelines were found on the website https://www.ip-paris.fr/en as of August 30, 2024. |

| The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Hong Kong, China | https://cei.hkust.edu.hk/en-hk/education-innovation/generative-ai-education |

| Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China | No guidelines were found on the website https://www.zju.edu.cn/english/ as of August 30, 2024. |

| Delft University of Technology, Delft, Netherlands | https://hri-wiki.tudelft.nl/llm/rules-guidelines |

| Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan | No guidelines were found on the website https://www.kyoto-u.ac.jp/en as of August 30, 2024. |

References

- Farrelly, T.; Baker, N. Generative artificial intelligence: Implications and considerations for higher education practice. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13(11), 1109. [CrossRef]

- Alier, M.; García-Peñalvo, F.J.; Camba, J.D. Generative artificial intelligence in education: From deceptive to disruptive. Int. J. Interact. Multimed. Artif. Intell. 2024, 8(5), 5-14. [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.Y. A comprehensive AI policy education framework for university teaching and learning. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 38. [CrossRef]

- Aljamaan, F.; Temsah, M.H.; Altamimi, I.; Al-Eyadhy, A,; Jamal, A.; Alhasan, K.; et al. Reference hallucination score for medical artificial intelligence chatbots: Development and usability study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2024, 12. e54345. [CrossRef]

- AlAli, R.; Wardat, Y. Opportunities and challenges of integrating generative artificial intelligence in education. Int. J. Relig. 2024, 5(7), 784-793. [CrossRef]

- Dogan, I.D.; Medvidović, L. Generative AI in education: Strategic forecasting and recommendations. In proceedings of 11th Higher Education Institutions Conference, Zagreb, Croatia, 21 – 22 September 2023; pp. 22-31. Available online: https://www.heic.hr/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/heic_proceedings_2023.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- Ghimire, A.; Edwards, J. From guidelines to governance: A study of ai policies in education. In proceedings of International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, Recife, Brazil, 8–12 July 2024. [CrossRef]

- Driessens, O.; Pischetola, M. Danish university policies on generative AI: Problems, assumptions and sustainability blind spots. MedieKultur: J. Media Commun. Res. 2024, 40(76), 31-52. [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.; Pervin, N.; Román-González, M. Generative AI and the future of higher education: A threat to academic integrity or reformation? Evidence from multicultural perspectives. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024 21, 21. [CrossRef]

- Liang, E.S.; Bai, S. Generative AI and the future of connectivist learning in higher education. J. Asian Public Policy. 2024, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Miao, F.; Holmes, W. Guidance for generative AI in education and research. Paris: UNESCO Publishing; 2023. p. 44. [CrossRef]

- Duah, J.E.; McGivern, P. How generative artificial intelligence has blurred notions of authorial identity and academic norms in higher education, necessitating clear university usage policies. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2024; 41(2): 180-93. [CrossRef]

- Dabis, A.; Csáki, C. AI and ethics: Investigating the first policy responses of higher education institutions to the challenge of generative AI. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1006. [CrossRef]

- Elsevier. Generative AI policies for journals: Elsevier; 2024. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/about/policies-and-standards/generative-ai-policies-for-journals (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Sage Publishing. Artificial intelligence policy: Sage; 2024. Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/artificial-intelligence-policy (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Springer International Publishing. Artificial Intelligence (AI): SpringerLink; 2024. Available online: https://www.springer.com/gp/editorial-policies/artificial-intelligence--ai-/25428500 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Russell Group. Russell Group principles on the use of generative AI tools in education. Cambridge: The Russell Group of Universities; 2023. Available online: https://russellgroup.ac.uk/media/6137/rg_ai_principles-final.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Moorhouse, B.L.; Yeo, M.A.; Wan, Y. Generative AI tools and assessment: Guidelines of the world’s top-ranking universities. Comput. Educ. Open. 2023, 5, 100151. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, N.; Johri, A.; Ali, A.; Hingle, A. Generative artificial intelligence in higher education: Evidence from an analysis of institutional policies and guidelines. Computers and Society: Artificial Intelligence. 2024. arXiv preprint arXiv, 240201659. [CrossRef]

- Cacho, R.M. Integrating generative AI in university teaching and learning: A model for balanced guidelines. Online Learn. J. 2024, 28(3), 55-81. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Tate, M.; Freeman, K.; Walsh, A.; Ballsun-Stanton, B.; Hooper, M.; Lane, M. A university framework for the responsible use of generative AI in research. Computers and Society: Artificial Intelligence. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Quacquarelli Symonds. QS World University ranking 2024. London: QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited; 2024. Available online: https://www.topuniversities.com/qs-world-university-ranking (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Ganjavi, C.; Eppler, M.; O’Brien, D.; Ramacciotti, L.S.; Ghauri, M.S.; Anderson, I.; et al. ChatGPT and large language models (LLMs) awareness and use. A prospective cross-sectional survey of U.S. medical students. PLOS Digit. Health. 2024; 3(9), e0000596. [CrossRef]

- Benke, E.; Szőke, A. Academic integrity in the time of artificial intelligence: Exploring student attitudes. Ital. J. Sociol. Educ. 2024; 16(2), 91-108. [CrossRef]

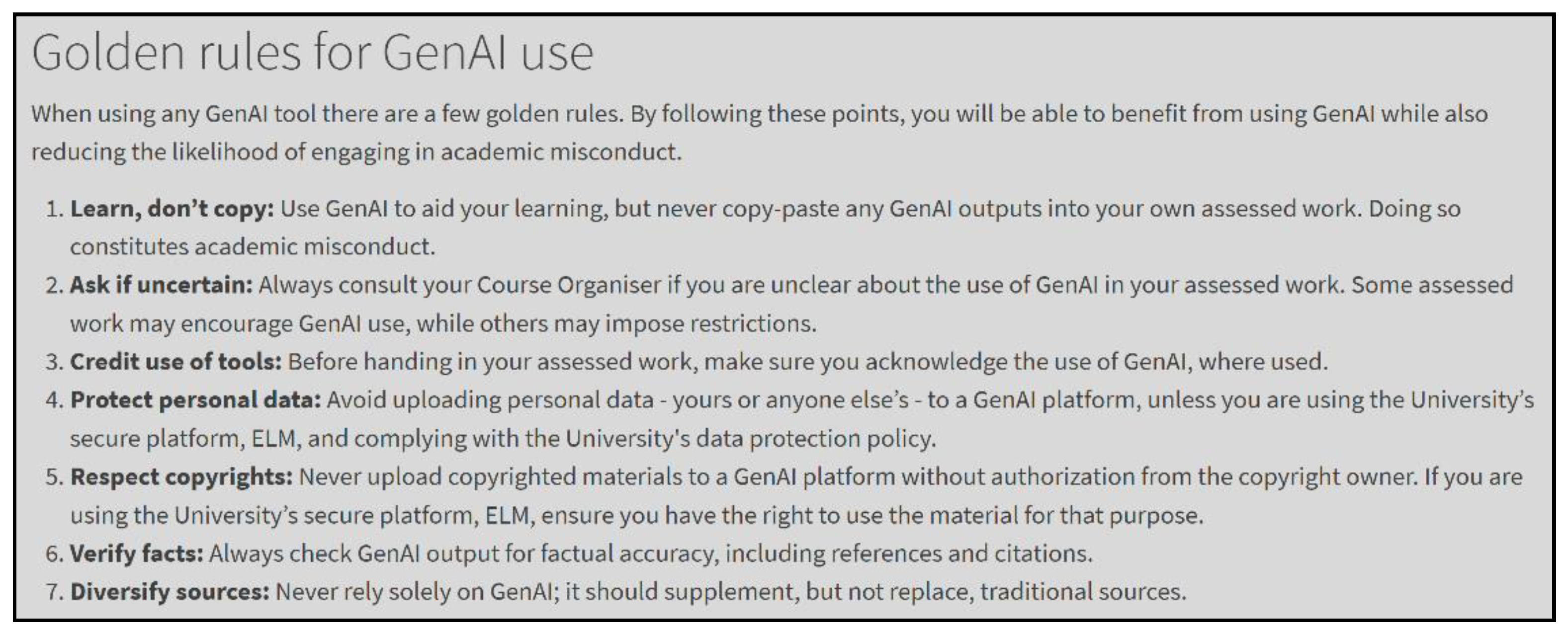

- The University of Edinburgh. Guidance for working with Generative AI (“GenAI”) in your studies. Edinburgh: The University of Edinburgh; 2024. Available online: https://information-services.ed.ac.uk/computing/comms-and-collab/elm/guidance-for-working-with-generative-ai (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- The University of Edinburgh. Generative AI guidance for staff. Edinburgh: The University of Edinburgh; 2024. Available online: https://information-services.ed.ac.uk/computing/comms-and-collab/elm/generative-ai-guidance-for-staff (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- The University of Edinburgh. ELM - (Edinburgh (access to) language models) Edinburgh: The University of Edinburgh; 2024. Available online: https://information-services.ed.ac.uk/computing/comms-and-collab/elm (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Lee, D.; Arnold, M.; Srivastava, A.; Plastow, K.; Strelan, P.; Ploeckl, F.; et al. The impact of generative AI on higher education learning and teaching: A study of educators’ perspectives. Comput. Educ.: Artif. Intell. 2024; 6, 100221. [CrossRef]

- Ardito, C.G. Generative AI detection in higher education assessments. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 2024; early view. [CrossRef]

- Gehrman, E. How generative AI is transforming medical education: Harvard Medical School is building artificial intelligence into the curriculum to train the next generation of doctors. Harvard Medicine. 2024. Available online: https://magazine.hms.harvard.edu/articles/how-generative-ai-transforming-medical-education (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Park, S.H.; Suh, C.H., Lee, J.H.; Kahn, C.E.; Moy, L. Minimum reporting items for clear evaluation of accuracy reports of large language models in healthcare (MI-CLEAR-LLM). Korean J. Radiol. 2024; 25(10), 865-8. [CrossRef]

- Kirova, V.D.; Ku; C.; Laracy, J.; Marlowe, T. The ethics of artificial intelligence in the era of generative AI. J. Syst. Cybern. Informatics. 2023; 21(4), 42-50. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B. Why AI detectors think the US Constitution was written by AI.: Ars Technica; 2023, July 14. Available online: https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2023/07/why-ai-detectors-think-the-us-constitution-was-written-by-ai/ (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Fowler, G.A. We tested a new ChatGPT-detector for teachers. It flagged an innocent student. The Washington Post. 2023, April 14. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/04/01/chatgpt-cheating-detection-turnitin/ (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Dathathri, S.; See, A.; Ghaisas, S.; Huang, P.S.; McAdam, R.; Welb. J.; et al. Scalable watermarking for identifying large language model outputs. Nature 2024; 634, 818-823. [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.S.; Khera, R.; Schwamm, L.H. Reviewer experience detecting and judging human versus artificial intelligence content: The Stroke journal essay contest. Stroke 2024; 55(10), 2573-8. [CrossRef]

- McCoy, L.G.; Ng, F.Y.C.; Sauer, C.M.; Legaspi, K.E.Y.; Jain, B.; Gallifant, J.; et al. Understanding and training for the impact of large language models and artificial intelligence in healthcare practice: A narrative review. BMC Med. Educ. 2024; 24(1), 1096. [CrossRef]

- Caballar, R.D. AI Copilots are changing how coding is taught. IEEE Spectrum. 2024. Available online: https://spectrum.ieee.org/ai-coding (accessed on 12 November 2024).

| Author(s) | Year | Focus/Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| Russell Group (UK) | 2023 | Developed a set of principles to guide the use of GenAI tools in higher education institutions. |

| Miao and Holmes | 2023 | Presented UNESCO’s global guidance on the use of GenAI tools in education and research. |

| Chan | 2023 | Surveyed teachers, students, and support staff across universities in Hong Kong to propose an “AI Ecological Education Policy Framework”. |

| Moorhouse, Yeo and Wan | 2023 | Reviewed the guidelines regarding the use of GenAI tools in assessments from the top 50 universities around the world. |

| Farrelly and Baker | 2023 | Explored the various ways in which Generative AI influences academic work, with a particular focus on its effects on international students. |

| Dogan and Medvidović | 2024 | Reviewed the literature on GenAI to provide recommendations for developing a strategy to incorporate AI into education. |

| Ghimire and Edwards | 2024 | Conducted a survey of heads of high schools and higher education institutions in the USA to examine the status of policies related to the use of GenAI in education. |

| McDonald, Johri, Ali and Hingle | 2024 | Reviewed GenAI-related guidelines established by 116 universities in the United States. |

| Dabis and Csáki | 2024 | Analysed policy documents and guidelines from 30 leading universities around the globe. |

| Driessens and Pischetola | 2024 | Evaluated GenAI-related policies of eight universities in Denmark. |

| Cacho | 2024 | Suggested a framework for integrating GenAI into teaching and learning at higher education institutions. |

| Yusuf, Pervin and Román-González | 2024 | Conducted a survey involving 1,217 students and teachers from 76 countries to explore the use, benefits, and concerns associated with GenAI in higher education. |

| Smith et al. | 2024 | Proposed a framework to encourage and facilitate the responsible use of GenAI in research. |

| Rank | Item | Yes | No |

| 1 | Introduction to GenAI tools | 37 (90%) | 4 (10%) |

| 2 | Guidelines issuing authority | 36 (88%) | 5 (12%) |

| 3 | Examples of GenAI tools | 34 (83%) | 7 (17%) |

| 4 | Objectives and scope of the guidelines | 31 (76%) | 10 (24%) |

| 5 | Contact information for guidance | 24 (59%) | 17 (41%) |

| 6 | Release/update date | 22 (54%) | 19 (46%) |

| 7 | How does an AI algorithm work? | 8 (20%) | 33 (80%) |

| Rank | Item | Yes | No |

| 1 | GenAI tools usage permitted | 41(100%) | 0(0%) |

| 2 | Instances unsuitable for GenAI tools usage (limitations) | 35(85%) | 6(15%) |

| 3 | Instructor approval for GenAI utilization | 31(76%) | 10(24%) |

| 4-5 | Domains for GenAI tools utilization | 29(71%) | 12(29%) |

| 4-5 | Strategies for use in classrooms and assessments | 29(71%) | 12(29%) |

| 6 | Details of GenAI tool employed (description/name/version/date) | 26(63%) | 15(37%) |

| 7 | Utilization and adaptation of GenAI output | 23(56%) | 18(44%) |

| 8 | Purpose of utilizing GenAI tools | 15(37%) | 26(63%) |

| 9-10 | Details of the provided prompts to the GenAI tool | 13(32%) | 28(68%) |

| 9-10 | Documentation of GenAI tool outputs | 13(32%) | 28(68%) |

| Rank | Item | Yes | No |

| 1 | Evaluation and verification of GenAI outputs | 38 (93%) | 3 (7%) |

| 2 | Academic integrity and misconduct | 36 (88%) | 5 (12%) |

| 3 | Data privacy and security | 35 (85%) | 6 (15%) |

| 4 | Legal compliance | 24 (59%) | 17 (41%) |

| 5 | Referencing and citing of GenAI outputs | 23 (56%) | 18 (44%) |

| 6 | Use of AI detection tools | 17 (41%) | 24 (59%) |

| 7 | Reporting mechanisms | 14 (34%) | 27 (66%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).