1. Introduction

From as early as the 1970’s, atmospheric radar scattering from well-defined layers of refractivity-index in the atmosphere have been observed by wind-profiler radars, (e.g., [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. More recently such observations have been further summarized by [

14] (among others). Full explanation of these results is still incomplete, since the scattering demonstrates some peculiar characteristics, including strong aspect-sensitivity. Interestingly, different models even propose seemingly opposite viewpoints, from highly stable regions to extremely turbulent regimes.

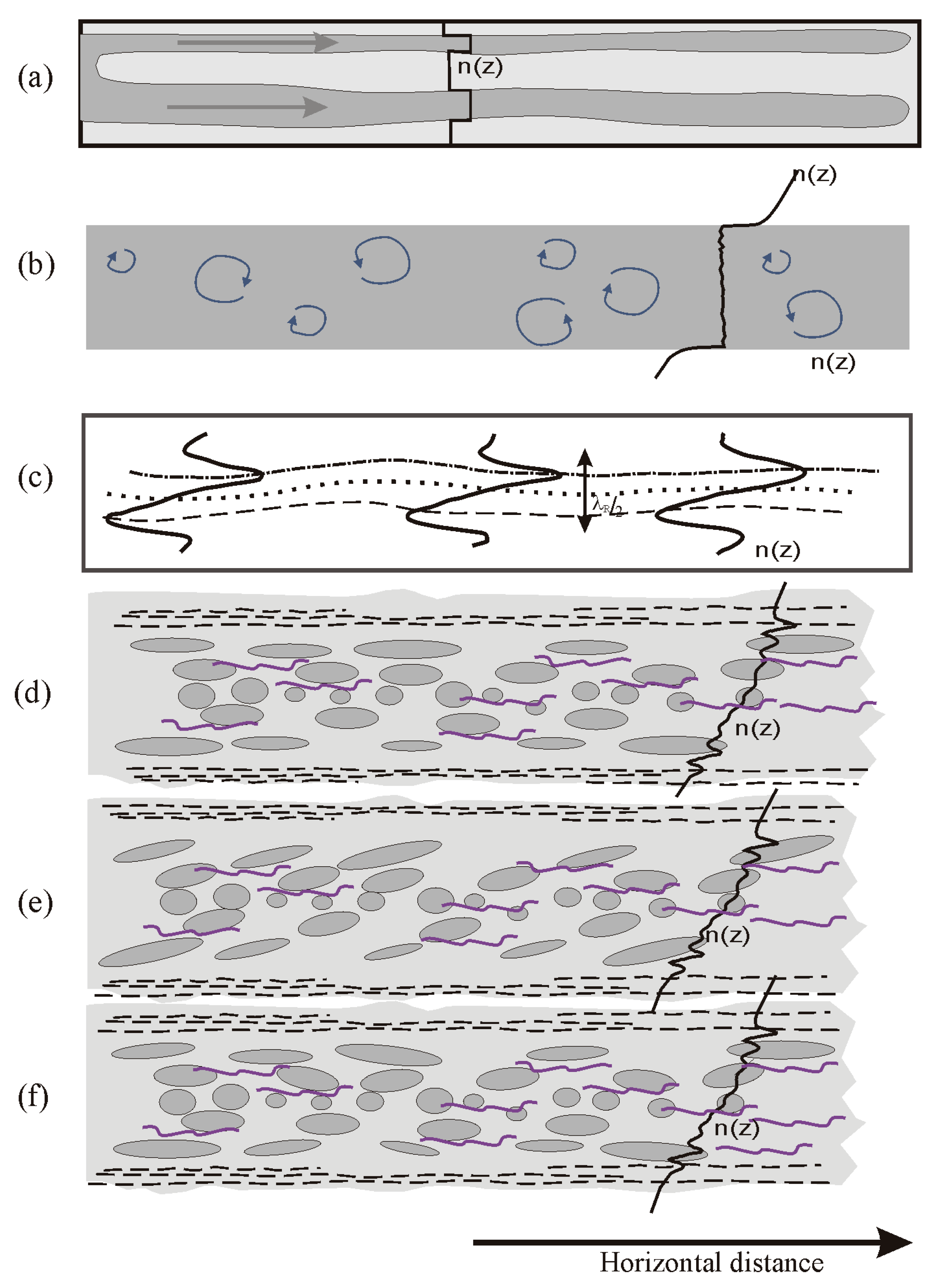

Figure 1 shows some sketches of some representative models which have been presented in the literature, in order to give some idea of the variation of explanations.

Figure 1(a) shows entrainment, in which sheets are drawn horizontally into each other and form alternating layers of refractivity e.g., [

10]; this model requires quite still air and little to no turbulence. Refractive-index edges between adjacent layers must be quite sharp, being completed in less than half a radar-wavelength (i.e., < 2-3 m thick). In contrast,

Figure 1(b) shows extreme turbulence with sharp edges, as proposed by [

15]; this model is now generally considered as unrealistic, but has been retained here for historical reasons.

Figure 1(c) shows the possibility of small-scale waves called “viscosity” waves, aligned quasi-horizontally, with a vertical wavelength equal to half the radar wavelength, acting as radio-wave reflectors [

16,

17]. These require non-turbulent conditions.

Figure 1(d)-(f) show more sophisticated turbulence models than

Figure 1(b). In particular, they simulate radio-scattering eddies as ellipsoids, with eddies at the edges of the layer having the largest axial-ratios. Elongated horizontal structures with rapid height-varying vertical refractive index can also exist at the edges, as illustrated by undulating horizontal broken lines (e.g., [

18] and references there-in). Both the eddies and the striated structures can back-reflect radio waves, although experimental evidence for such structures is less clear.

Figure 1(d) shows the case that the eddies are aligned with the edges of the layer, while

Figure 1(e) shows the possibility that the eddies are aligned at an angle to the layer.

Figure 1(f) shows the case that the eddies are aligned quasi-randomly.

Figure 1(e)-(f) are considered more appropriate for turbulent scatter than

Figure 1(b). In

Figure 1(a) and 1(c), the radar signal returned to the ground is considered to behave like reflection of light from a rough mirror. In cases 1(e)-(f), the process is not considered to be reflection, but rather a “scattering” process (e.g., [

3,

19]). For radar signals incident perpendicular to the long-axis of the ellipse, strong signal is scattered perpendicular to the long axis of the ellipse, but signal is also scattered at angles which are not perpendicular, albeit with diminishing energy as one moves further from the perpendicular axis. Only ellipsoids with a width of order of one half of the radar wavelength produce significant scatter; other ellipsoids at other scales exist but are not drawn. More details on the relation between the so-called “scatter polar diagram” and the axial ratio of the ellipsoids can be found in [

20], Figure 7.18. The radar responds to these eddies - if the layer and the eddies have different orientations, then the scattering eddies will be the main defining feature, unless other quasi-horizontal extended strata (like the broken undulating lines) also co-exist nearby.

Such layers have also been seen by other methods. [

21] have observed similar structures by optical methods in clouds, and these have thicknesses of ~7–30m with relatively sharp edges. In-situ observations using kites, radiosondes, high-altitude balloons, helicopters, drones and other instruments also reveal similar structures e.g., [

7,

8,

9,

10,

14,

18,

22] among others.

However, most studies have been relatively short-term, covering a few hours or perhaps a few days. Our purpose in this paper will be to make studies over much longer time-scales - monthly, seasonal and over multiple years. The above shorter-term discussions will nevertheless prove important in interpretation of our results.

As a final point in this introduction, it is of value to determine typical isobaric slopes that might be expected in “normal” atmospheres. We will determine typical slopes of isobars in various circumstances. Recognizing that the pressure in an isothermal atmosphere is given by P=P0 exp{-z/H}, where H is the scale-height, then dP = P0/H exp{-z/H}dz, so δz = H/P0 exp{z/H}δP. Hence at ground level, for H≈8500m, a change in pressure of 1 hPa corresponds to approximately 8.5 metres in height. At 10 km altitude, the temperature is less, so the scale-height is 6.5 km, but the exp{z/H} term needs to be included, so 1 hPa corresponds to ~30m of height.

As an example, if a low-pressure system is at 980 hPa and a high-pressure system is at 1020 hPa and these are separated by 500km, the mean slope between systems is tan−1{(1020-980)×8.5/500e3} = 0.04o. If we consider a frontal system, and suppose that the change in pressure is 20 hPa across a distance of 50 km, the mean slope is 0.2o. At 10 km in height, 1 hPa corresponds to a 30m displacement in height, so these angles will be ~30/8.5 times higher, so up to 0.6o in an extreme frontal system.

Another useful example comes in the form of sea- and lake-breezes. [

23] estimates a pressure gradient of 1 hPa per 50 km as typical of a sea breeze, so that would give a slope of ~ 0.01

o. A more extreme, but nevertheless realistic, case would be a situation in which the change in pressure might typically be 4 hpa across a horizontal traverse of 50 km, giving an isobaric slope of

tan−1( 4.0*8.5/50e3) = 0.04o. At the top of a sea-breeze circulation, (say at 4 km altitude, where the temperature is ~270K, so that

H~ 7.6 km, and

exp {z/H} =

exp(4000/7600) ≈1.7), then the pressure changes by 1 hPa across ~13m in height, so the angle of an isobar could be ~ 13/8.5 times more, or ~0.06

o.

These values will prove useful later as limits for our data. We will measure monthly averages of the slopes so it is probably fair to say that slopes of more than 0.2o might be considered unrealistic if they were to be explained as simply slanted isobars. Slopes larger than 0.5 degrees would definitely need alternate explanations.

4. Results

4.1. Correlations

The value of

ϕ0 at which the correlation coefficient maximizes is called

ϕΜ (M means max value of

ρ).

ϕΜ varies as a function of month and height. The value of

ϕΜ at each height and for each month was subsequently found, and we then recorded the value of

ϕΜ , the value of the correlation coefficient in that direction (

ρM), and the regression-slope of the best-fit line (

sB). The value

sB was then used to determine

θ, as described above. The optimum value of

θ will be referred to as

θB, where

B stands for “Best” fit (see

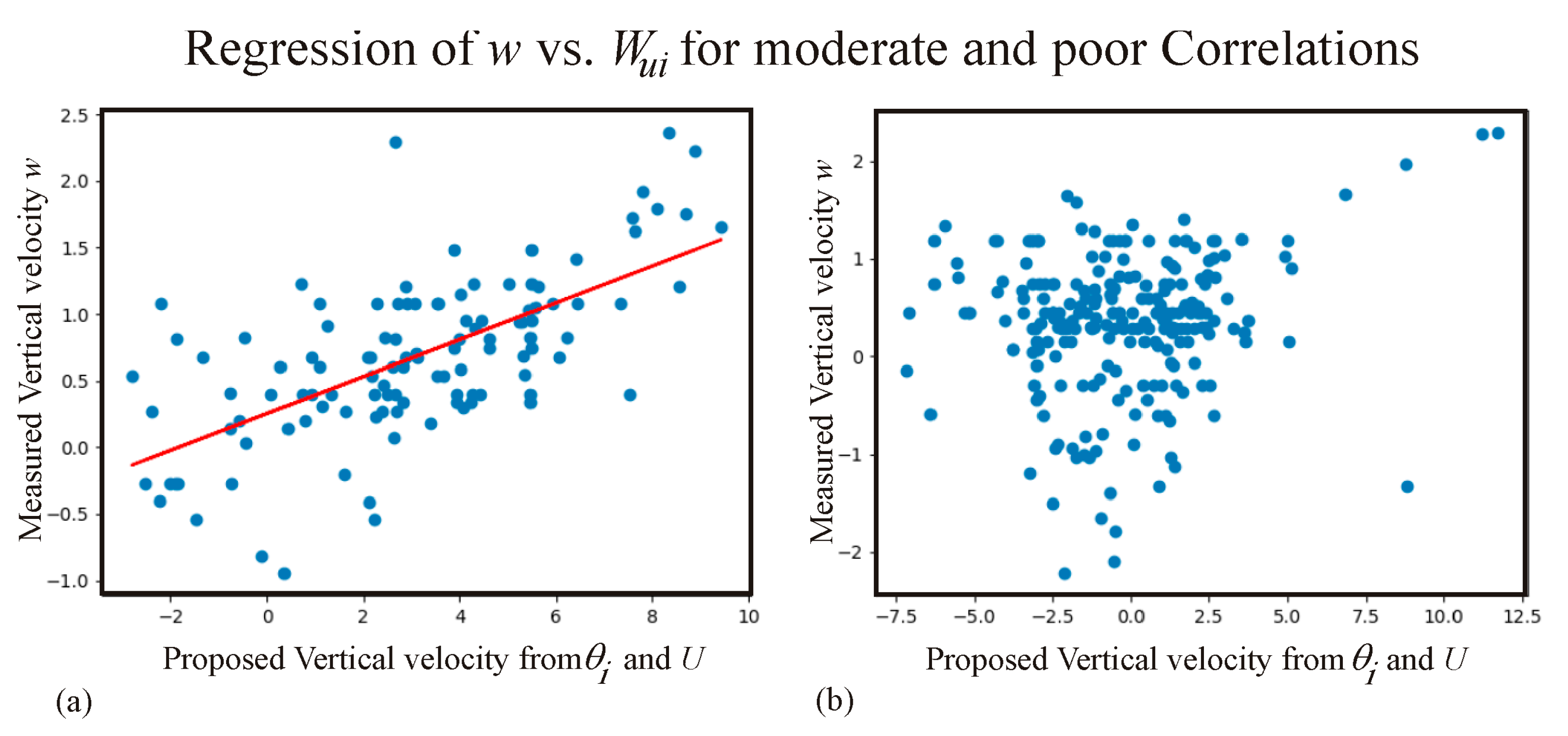

Figure 3(a) as an example). The offset of the least-squares fit (demonstrated in

Figure 3) at

Wu=0 was also recorded. The layer-tilt (also called the layer-slope) is usually expressed in degrees, and represents the tilt of a layer from horizontal. Graphs of these 3 parameters were then produced: examples are shown in

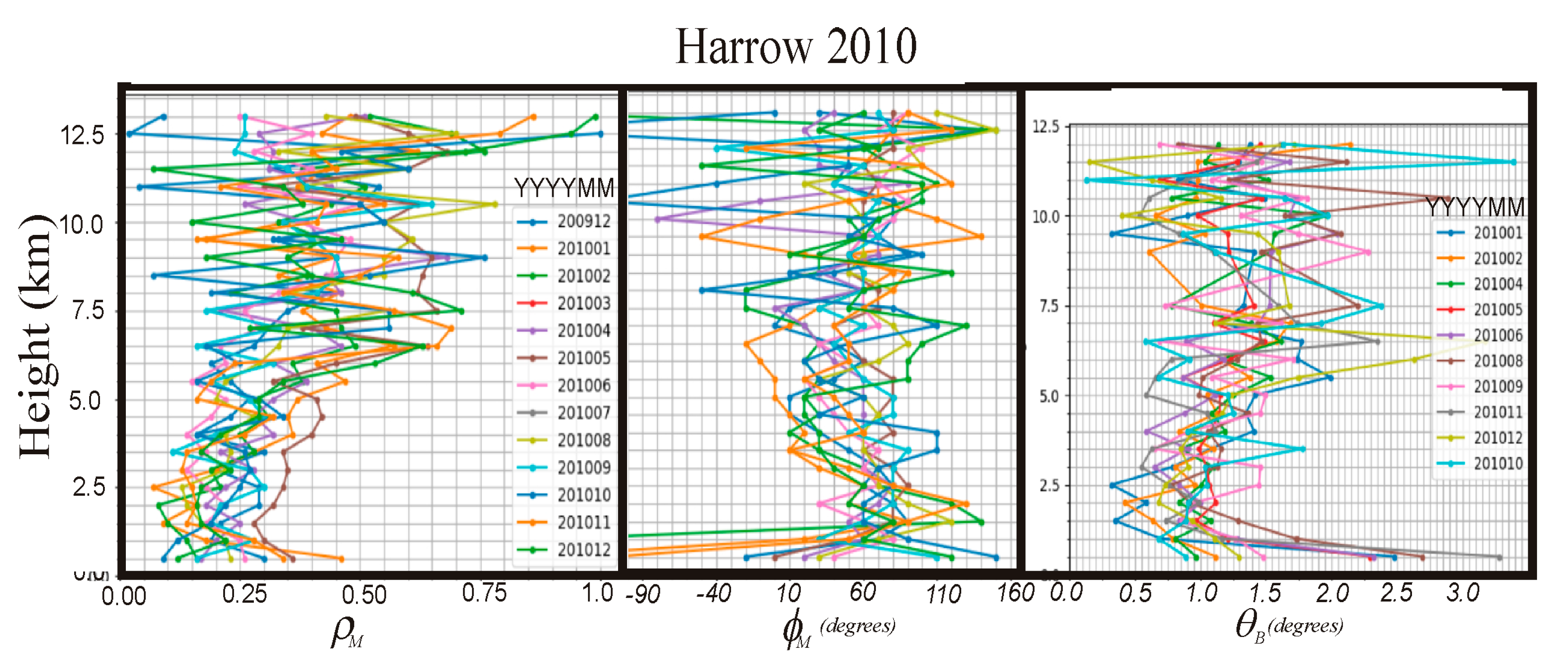

Figure 4.

While the different months are colour-coded, the main purpose of the graphs is to show typical values, variability and spreads in values. Of particular note are the facts that (a) the correlations were generally > 0.2, with only 50 points out of 325 (15%) having correlations < 0.2 (and only 20 out of 325 (6%) having a correlation < 0.15), (b) the azimuthal directions were not random, but were mainly limited to a range between approximately 10o and 100o for Harrow in 2010, and (c) the layer-slopes (tilts) were generally between 0.4o and 3o in this case.

Again, it is emphasized that a correlation coefficient of around zero does not mean in any sense “bad data” - indeed the cases with ρM = 0 actually represent the “ideal” cases when the layers were close to horizontal. As seen, this seems true on only ~20% of occasions. The other 80% correspond to situations with non-horizontal layering. Reasons will be discussed further in the “Discussion” section.

Of significant note is the fact that tilts as high as 2.5

o and even 3

o occur. These are

much larger than the estimates demonstrated at the end of the “Introduction”, so it is clear that the simple idea that these tilts are due to large-scale tilts in the isobars is not at all appropriate. For now we concentrate on the measurements: explanation of the reasons for the tilts will be left to the “Discussion” section, although we will hint here that

Figure 1 will be key to these discussions.

For analysis purposes, the raw data shown in

Figure 4 are not ideal, and some averaging is needed before any trends stand out. Different averaging schemes were tested, including “height-averaging” and cross-month averaging. In the end, the best scheme for interpretation proved to be a 3-point running mean vertically and a simultaneous 3-point running mean over successive months. In cases where there are missing months, forbidding calculation of running means across successive months, a 5-point running mean with height is used, as it gives reasonable smoothing but retains sufficient height-structure. Three-point running means with monthly averages mean that only the data at 3-month steps are truly independent, so the results can best be considered as “seasonal” results.

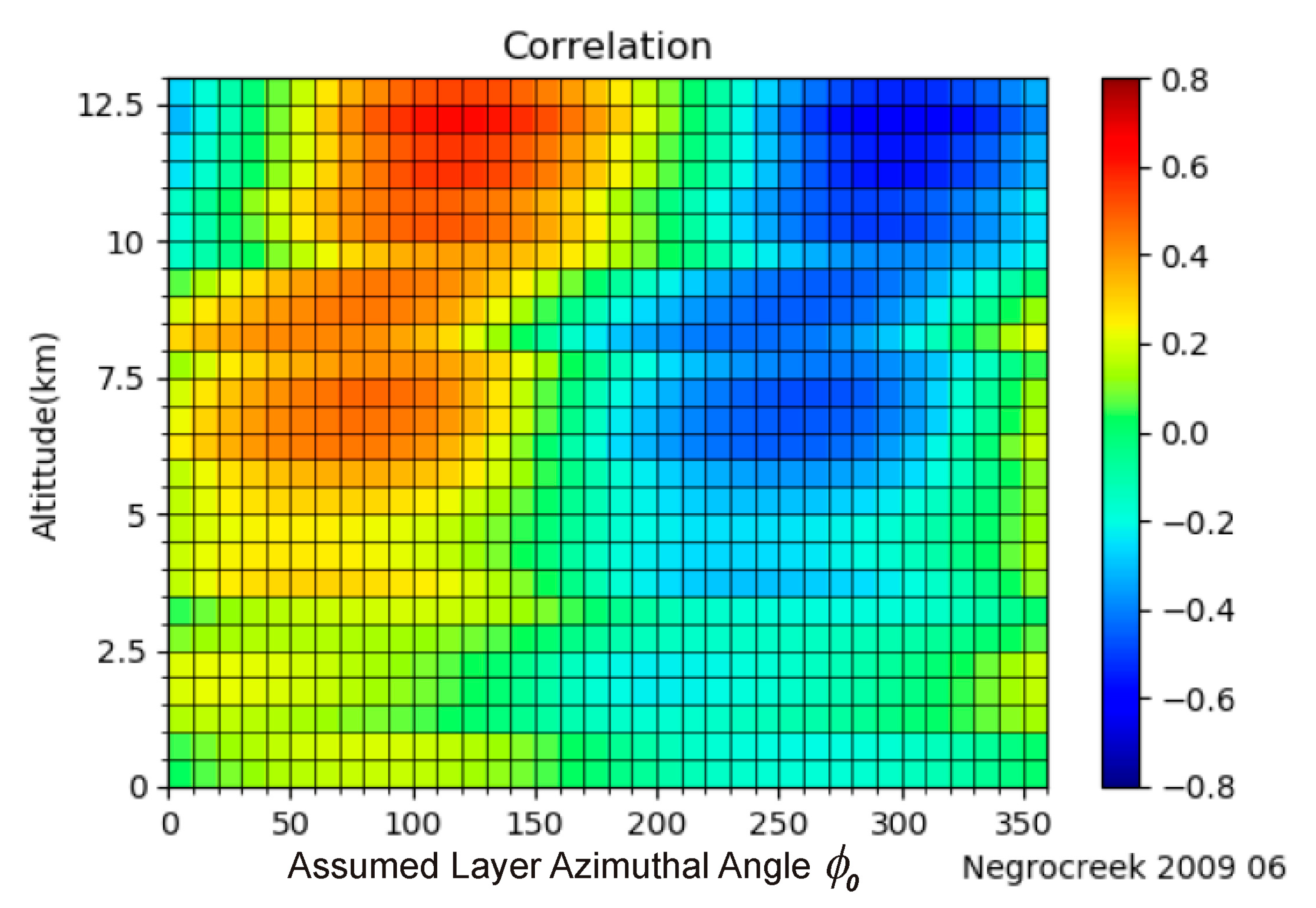

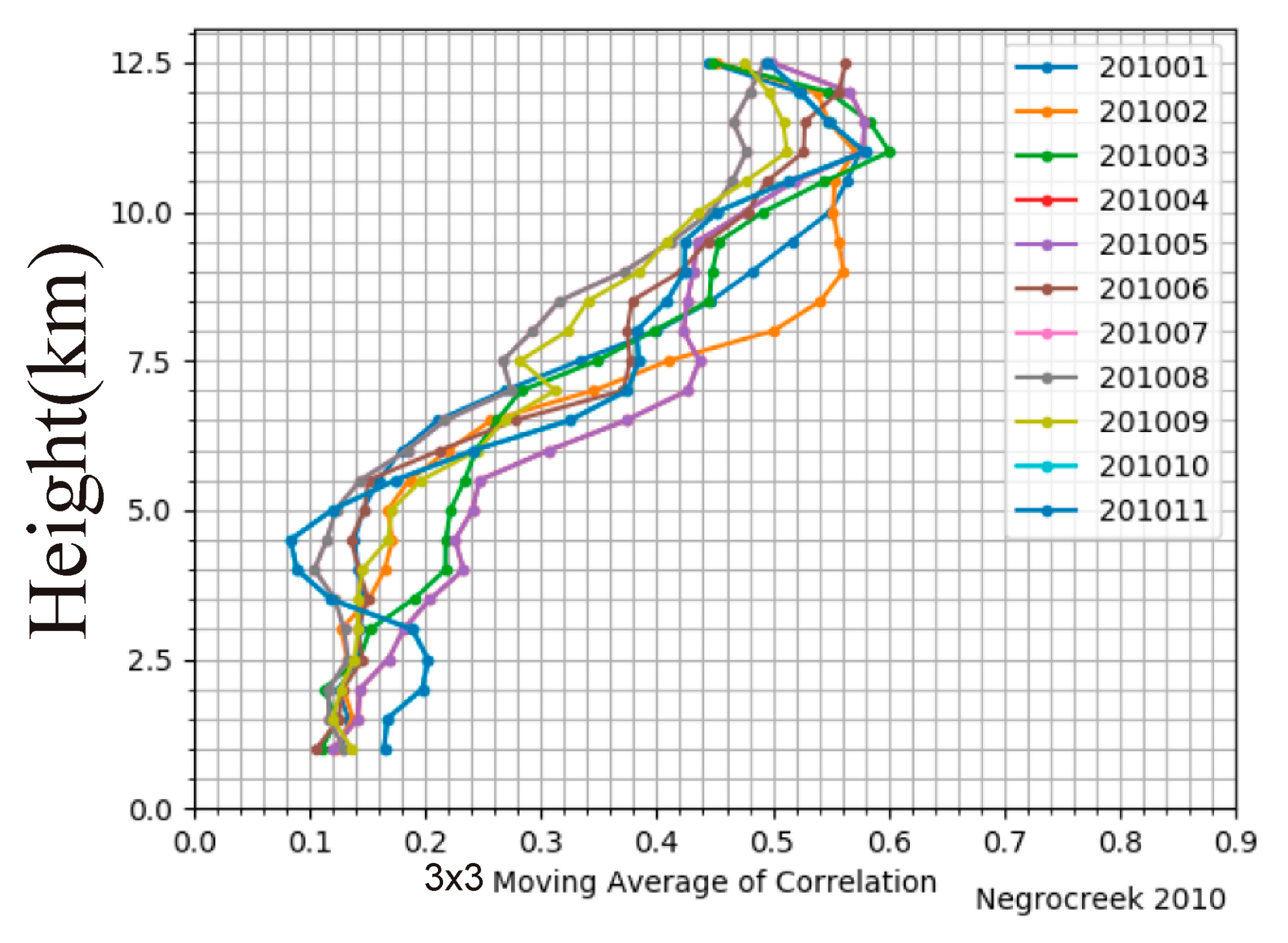

A sample plot of the correlation coefficients smoothed with this 3×3-point running average is shown in

Figure 5 for the Negro Creek Site. This figure shows that with the 3×3 running average, the graph appears less noisy, and trends like the increasing mean correlation as a function of height are now clearly visible. In this case, months range only from February to November, since, for example, “February” is an average over January, February and March. Hence an average for January is not possible without also using December, 2009. Likewise December 2010 is missing.

In later discussions we will in fact create running means which cross over successive years, but this is not necessary for the purpose of this illustration. This graph is quite representative of all sites, with the average values of ρM increasing with height, and typical largest correlations reaching ~0.4-0.6.

No further analysis of the correlation coefficients will be presented - the primary purpose of their calculation was to identify layering alignment (when layers existed) and so allow determination of ϕΜ , and thence θB. The primary focus will be on the tilt angle θB.

Because the procedures and results presented here-in are quite new, we chose to be very cautious in the data quality accepted. Hourly average data required at least 5 horizontal wind measurements per hour at any height, and at least 3 measurements of w per hour at each height. Furthermore, over 90% of the hours in each month had to have acceptable data, so while most radars had data in all months of the year, there were frequent months which were excluded from our particular analyses due to insufficient data. In the main, we used the year of 2009 and 2010, though in some cases data from 2011 and 2012 were available.

4.2. Azimuthal Alignment

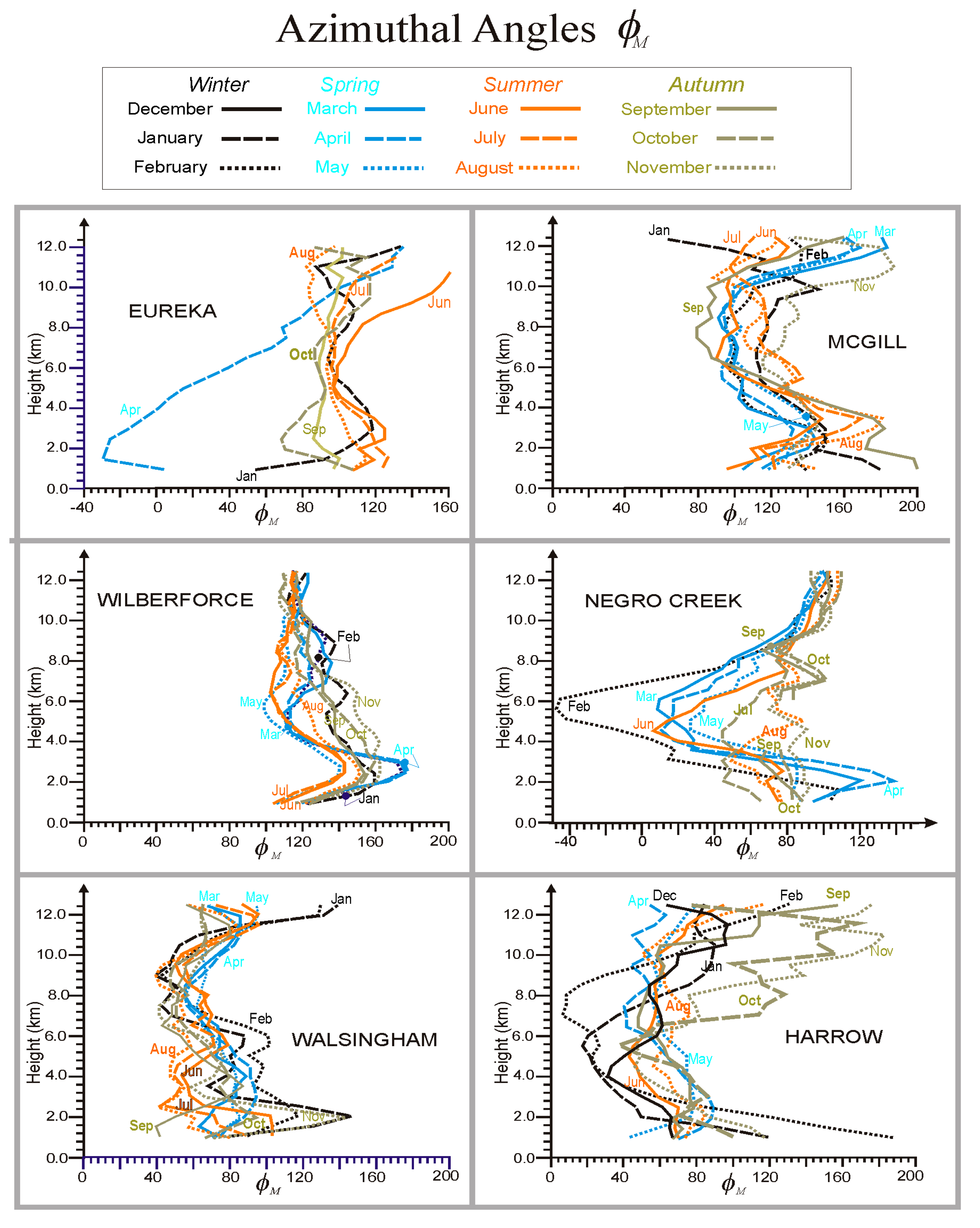

Figure 6 shows some representative azimuthal angles

ϕΜ. Data in

Figure 6 were determined as a “composite year”, taking the year (either 2009 or 2010) with the largest number of available months as the “anchor-year”, and filling in months missing from that year with the corresponding month from the alternate year. It will be noted that for the sites of Negro Creek, Walsingham and Harrow, the azimuthal alignment of the tilted layer was between 30

o and 130

o, so roughly aligned with the direction of the prevailing winds at these sites. We do not investigate the relation between the tilt alignment and the prevailing wind in detail here, as the main purpose is to establish the existence of these tilted layers. Detailed studies of relations between tilt alignment and prevailing wind directions could be a topic of future study.

Generally, most months at all sites showed consistency between consecutive months. Behaviour is modestly well defined. ANOVA (ANalysis Of VAriance) tests were performed, and showed that all sites behaved independently, and hence were not simply some form of “noise”.

ANOVA tests will be discussed in more detail later.

In regard to

Figure 6, apparently anomalous profiles do appear, particularly in April at Eureka and in February at Negro Creek. Unusual events are a natural part of any weather history. In the case of Eureka, no data were available in the preceding or following months (March and May), so sanity checks were not available. It is most likely that there was a sustained event of strong winds from the south for a significant fraction of April in this year, rather than the more common prevailing winds from the west, which may have resulted in re-alignment of the tilted layers for a significant portion of the month.

4.3. Zenithal Tilts

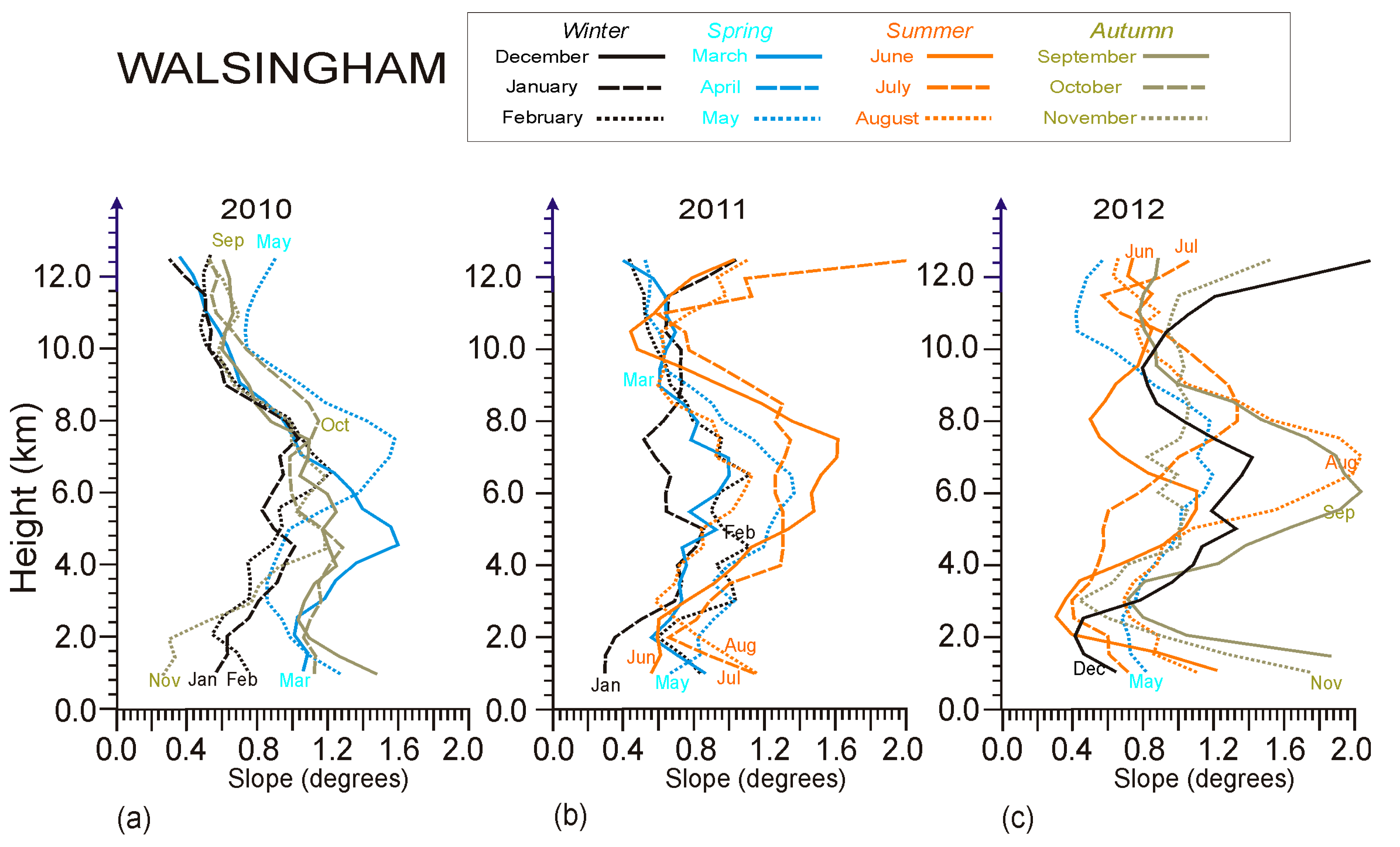

We now turn to study the tilt angles from horizontal.

Figure 7 shows 5-point averages of

θB over height for the available months of 2010, 2011 and 2012 for Walsingham. No averaging as a function of month were used here: only smoothing with height was used.

Some points are obvious here. First, the winter-time values (black) tend to be smaller, and January and February in both 2010 and 2011 were similar. Second, the largest values are evident in March and May in 2010, in June and July in 2011, and in August and September in 2012. (No summer months were evaluated in 2010). October and November, where available, were generally in the middle. So there is modest evidence of seasonal effects. Hence in order to reduce statistical scatter, some averaging over successive months seemed appropriate.

Therefore in order to present the key results in a modestly compact form, running averages across successive months were employed. Specifically, we used the following process. First, for each site, all years analyzed were used; the number of years were not the same in all cases. Walsingham had data in 2009, 2010, 2011 and 2012. McGill only had data in 2009 and 2010. But all sites had at least 2 years. Then, values of θB were averaged across all years for each month at each site. Some years had missing months, so only available years were used in the averaging. A month of data formed across several years of data in this way is referred to as a “composite month”, and a collection of all such composite months is referred to as a “composite year”. By doing this, most composite years included at least 10 months and in many cases all 12 months were covered. The next step was to create both 3-point and 5-point running means averaged over height. Finally, 3-month running means were created from the 3-point height-based running means for all uninterrupted sequences of composite months. However, for cases where a composite month did not have a neighbour on one or both sides, a running mean across months was not used, but rather the 5-point running means as a function of height were used as a substitute. As an example for a sequence of composite months March, June, July, August, September, and October, with no data in April, May or November, 3-point height averages coupled with monthly 3-point running mean (referred to as a “3×3 running mean”) were used for July, August, and September, while 5-point height-only running means were used for March,

June and October. Use of a 5-point mean was chosen rather than for example a 7-point mean, as 7-point averages and even larger degrade the height resolution too much. Finally, December and January were considered as “sequential”, so that a running mean for January meant averaging over December, January and February, and a running mean for December was formed by averaging over November, December and January.

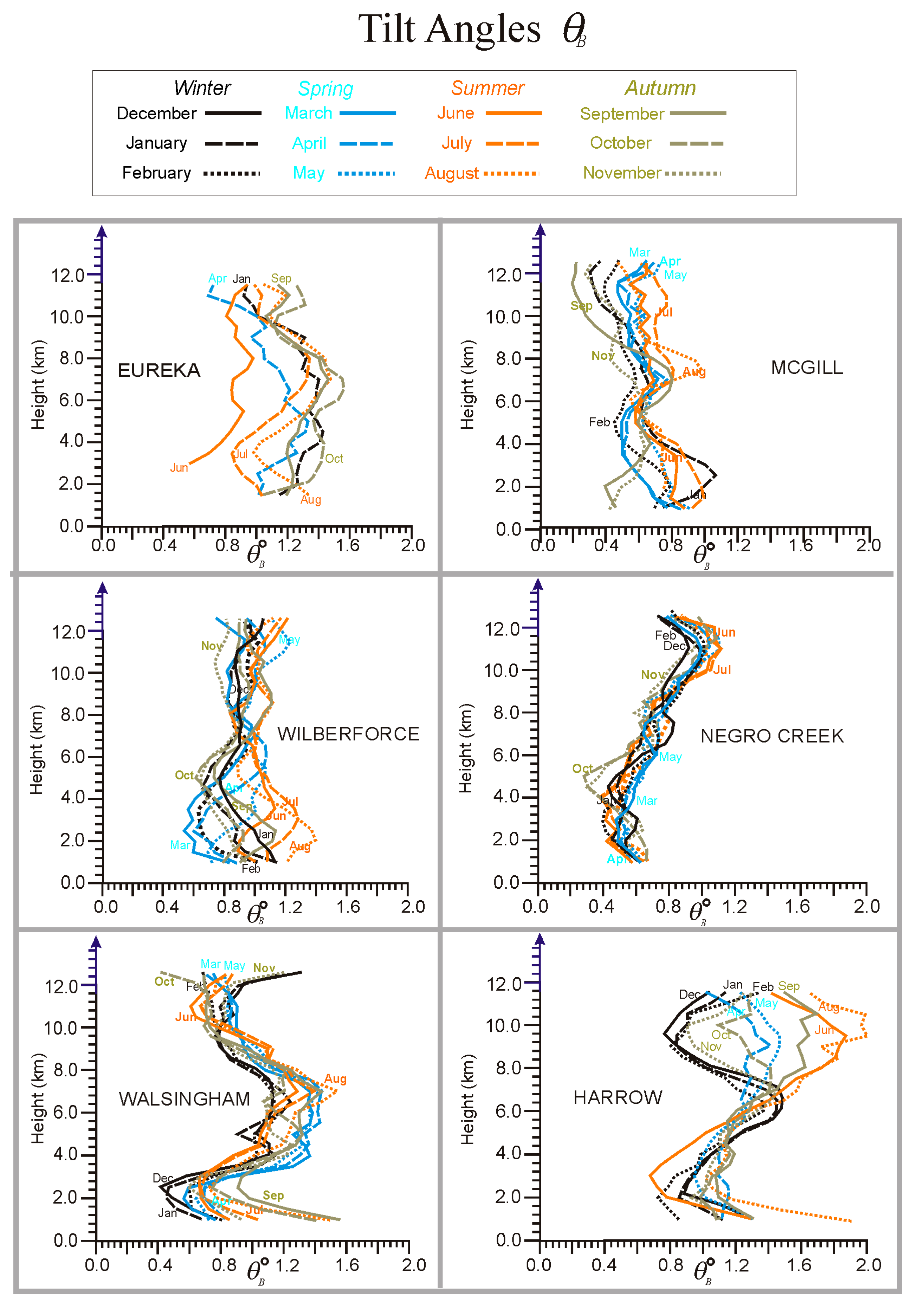

Results of such averaging are shown compactly in

Figure 8 for all sites. ANOVA tests verified the independence of each site, as will be discussed later. Behaviours are clearly different at all sites. For example, Negro Creek showed very little seasonal dependence, while Harrow showed a very strong seasonal dependence above 7 km, with smallest values of

θB in Winter, moderate values in Spring, then largest values (up to 2

o) in Summer and then modest values again in Autumn. On the other hand, Wilberforce showed greatest variability below 4km, again with a clear annual cycle with maxima in Summer. Walsingham showed greatest variability between 4 and 8 km altitude.

Eureka shows June to be distinct from the other months of the year, but it must be noted that this profile came from only 1 month of 1 year, so it is not subject to the same level of averaging as some other months. As discussed earlier, occasional anomalous data should come as no surprise in weather-related studies.

4.4. Statistical Details

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 have been presented without error bars, so it makes sense to briefly look at possible errors, especially for the azimuthal angles

ϕΜ and the tilts

θB. To do this, running 3×3 standard deviations were created. These were formed similarly to the process used to create

Figure 6, but for running standard deviations rather than running averages, using mainly 2009 and 2010 data independently. Thus the errors deduced would be upper limits as they involve less smoothing than say the procedures used for

Figure 8. Mean standard deviations of

ϕΜ over the 2 years were the calculated and results were as follows: Eureka 22.2

o; McGill 24.2

o; Wilberforce 22.9

o; Negro Creek 29.8

o; Walsingham 33.6

o and Harrow 27.6

o. These numbers include any natural geophysical variability, so are larger than random errors alone. These are standard deviations for a single month and height. Using the Central Limit Theorem, and recognizing the smoothing applied in producing the profiles, the standard errors for the mean of any profile will be given by the errors shown above (~20

o-30

o) divided by √24 (24 points in a profile) or ~5× smaller. Typical errors for the mean were therefore about 5

o-6

o for each profile, so that individual profiles which differ consistently across all heights by more than ~5-6

o are statistically significant. A more thorough treatment using ANOVA’s will be discussed shortly. Greater detail is given in

[34]).

In regard to tilts, a similar treatment gives standard deviations as follows: Eureka 0.17

o; McGill 0.15

o; Wilberforce 0.12

o; Negro Creek 0.11

o; Walsingham 0.22

o and Harrow 0.19

o. As above, standard errors for full individual monthly profiles in

Figure 8 were ~5× smaller, so ~0.04

o. Hence in

Figure 8, the differences between Spring and Summer below 5km altitude at Wilberforce, the differences between Spring and Summer at 3-9 km at Walsingham, and the seasonal cycle at Harrow above 7 km all have high geophysical significance. In contrast, the differences between the different composite months at Negro Creek in

Figure 8 are likely not significant. Indeed, Negro Creek gives a good opportunity to obtain a visual estimate of the errors. At 8 km altitude, where variability between profiles is least (and hence is least likely to be affected by geophysical variability) the values of

θB range from 0.7 to 0.85 i.e.,+/- 0.075. There are 12 profiles, so the error for the mean is 0.075/√(12), or 0.02

o. Although only a visual estimate, this is not too different from our estimate of 0.04

o above: thus a non-geophysical error for the mean in any profile of ~0.04

o is reasonable. Additional fluctuations due to geophysical effects occur on top of this. Overall, unquestionably these tilts are real, and not some sort of noise artefact.

We now turn to ANOVA studies, which involves the F-factor. The F value calculates the ratio of (i) the variance obtained with all the data being treated as one large block, irrespective of classification (group) vs. (ii) the mean of the variances of each of the groups. Colloquially, in medicine, F is often referred to as MST/MSE, where MST is the mean square of treatments, and MSE is the mean square of error. The term “Treatments” does not apply in the atmospheric case, but an ANOVA may be applied equally well here, as is now outlined.

The fundamental idea is as follows. First the user defines what a “group” constitutes. In our case, a sensible choice is to regard every site as a different group. Then the variance of each group is calculated, and these are averaged. The mean value for each site is removed of course during the determination of each variance. Then we consider all the data as one giant collective, and calculate its variance. The larger data-set incorporates all of the means of the separate sites, so if the means at each site differ, this will increase the total combined variance relative to the typical individual variance for the separate sites. Hence if the means all differ, the variance found using all the data will exceed the typical variance for any individual site. So the ANOVA essentially tests the null hypothesis that all means at all sites are equal. If all are equal, it might be true that the “tilts” and “azimuths” determined were due to some common aspect of the radar design or analysis technique, and so might not be geophysical. This will be revealed by values of F around unity. If, on the other hand, the mean values at each site are different, then F will be much larger than unity, and will indicate that the sites are geophysically different. The P-value gives the probability that the data at all sites were due to a process in which all means are equal (e.g., noise, or some radar-related quirk). Determination of the value of P requires two additional input parameters, namely the number of degrees of freedom (generally the total number of points minus 2) and the rejection level. The rejection level is a fraction, referred to as α. Typically α is chosen to be .05, or 0.01 (5% or 1%), and an associated Fα is determined. If the measured value of F exceeds Fα, the null hypothesis is rejected and we say the means differ from equality. This contrasts to a t-test, in which 2 means are compared. In an ANOVA we can only say that either (i) the means at all sites were equal (small F) or (ii) the means differ. In the latter case, it is possible that some means are the same and others differ, or they may all differ - the ANOVA does not single out individual cases.

A Python program was used for our calculations, specifically Python version 3.7 using scipy:stats.f-oneway. In this program-suite, a value for α is not assumed, but rather the program calculates the values of α that corresponds to our value of F, and calls it “P”. So P is a substitute for α. In our case, there were many points, and the number of degrees of freedom well exceeds 100 - at such large values, the relation between F and α becomes largely independent of the number of degrees of freedom.

First, an ANOVA was performed on all the tilt-angles for all the 6 sites separately for 2009, and then again for 2010. For 2009, F = 66.24 and P = 6.33 ×10−60, while for 2010, F = 63.03 and P = 1.41×10−60. So the probability that the data at all sites all originated from the same underlying data-set was exceedingly small, strongly supporting the proposal that the tilts were truly geophysical in origin.

As a second test, since Walsingham was the only site that had 4 years of data, these data were also treated with an ANOVA analysis. The four groups were considered as the four separate years. The goal of this procedure was to investigate if the data from different years were broadly similar. We would expect some year-to-year differences, but some generally similar behaviour (see

Figure 7). The results were

F = 3.45 with a

P-value of 0.019, or approximately 2%. More thorough treatments are presented in

[34], but a

P-value of 2% is reasonable - it suggests some level of similarity between the different years, but not exact agreement, which is consistent with natural year-to-year variability.

5. Discussion

Various other trends are evident in Figs 6-8: these will not be fully discussed here, and will be the foci of later studies. The key points in this paper are (i) non-horizontal tilt-measurements are real, (ii) there are clear site-to-site differences as verified by ANOVA tests and (iii) these tilts are too steep to be explained by simple isobaric slopes. A primary remaining objective is to explain the origin of these tilts.

Before proceeding with the discussion of mechanisms, it is worth once more reflecting on the nature of the vertical beam. If the beam were indeed tilted off-vertical, then one can imagine specific scenarios in which the layer forms perpendicular to the beam, so the layer appears horizontal as far as the radar is concerned. However, one can also envisage many more scenarios where the effects of the beam-point-direction and the layer makes the effective beam calculated worse. Since the latter is more common, it would be reasonable to assume that over long-term averages, the combined effect of the layers and the beam will generally be additive. Hence the tilts shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 should all exceed the actual vertical-beam tilt. Therefore the lowest values seen in

Figure 7 and 8 would be upper limits on the tilt of the vertical beam. Occurrences of a tilt of 0.2

o are moderately common in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, tilts of 0.2

o to 0.4

o are very common. Hence we may conclude that all vertical beams have tilts of less than 0.4

o and very likely less than 0.2

o. Other studies of azimuthal tilt angles relative to particular radar orientation features were also undertaken in [

34], which also further demonstrated that tilts of the main beam were of little consequence in our studies, so henceforth we assume that all tilts measured were geophysical in origin.

In addition, it is important to recall (again) that values of the maximum correlation coefficient ρM of less than 0.15 occurred for layers which were close to horizontal, and in many ways, such occasions apply to the ideal situation of a perfectly horizontal layer - but the fact remains that such “ideal” situations are less common than might be naively expected. We will argue shortly that this expectation of “flatness” may itself be premature.

Next, possible geophysical causes of these tilts need to be considered. Several points need to be noted. First, gravity waves have polarization relations between the horizontal and vertical components of the wave (e.g., [

20] and [

35]

Equation 11.18), so that horizontal and vertical wind components are in phase or in anti-phase. However, this effect is an additional effect on top of the mean wind; our studies have been looking at correlations between the vertical velocities and the total mean horizontal winds, which is not the same. Furthermore while the vertical and horizontal winds are well understood if they are measured at the same point in space, the radar measures horizontal winds using the off-vertical beams, and the vertical wind on the vertical beam, and each are measured at different times and different points in space. Therefore any phase relationship depends on the wavelength and period of the wave. Further, the ratio of vertical to horizontal velocity components becomes smaller as the period increases, and we use hourly averages, which is quite long for a gravity wave. In addition, there may be many waves present at any one time, with different wavelengths and periods. So all in all, the effect of polarization relations of gravity waves will be washed out.

There is one type of gravity wave which might play a role. Lee waves, generated by flow over mountains, can produce steady-state conditions overhead of a radar close to the mountain (e.g.,

[36]). If a single wave were dominant, it is possible that it may lead to fixed tilts over the radar. But over the course of a month, multiple waves may be generated, with different horizontal wavelengths, and these would produce varying layer-slopes in the scattering layers. If the mean wind changes direction, then the situation will also change; for some wind alignments, there will be no lee waves. Such a scenario involving lee-waves also actually requires a nearby mountain - most of our radars do not have nearby mountains. So lee-waves cannot explain our results.

Thus gravity wave cannot explain our long-term correlations. Larger-scale planetary waves have far gentler-sloping isobaric tilts, and will produce angles comparable to those smaller slopes discussed at the end of the introduction of this paper.

So waves cannot explain our results.

Therefore, we must look at smaller scales, and so we return to

Figure 1. Entrainment, as shown in

Figure 1(a), is a possibility, and could produce tilted structures. But entrainment is usually associated with fairly still air, and we need a mechanism that works for a significant fraction of a month. Viscosity waves (

Figure 1(c)) would, by their nature, have tilts, but it is not expected that these are a dominant process - they are more likely an occasional occurrence.

So we turn to

Figure 1(e). This proposes that within a patch of turbulence, ellipsoidal eddies form, and that they have systematic tilts. In intense turbulence, there can be some questions about whether such eddies even exist, but they are frequently used in ideological discussions of turbulence. To look at it another way, all atmospheric refractivity structures can be Fourier transformed, and radar backscatter occurs from the Fourier components of length λ/2, aligned perpendicular to the direction of travel of the radar-wave. But we could equally mathematically decompose the entire refractivity structure into a collection of ellipsoids of different widths, lengths and refractive index, and base our modelling on scatter from these ellipsoids (similarly to [

20], Figure 7.18.)

So we will adopt this model of ellipsoidal refractive-index structures for our discussions.

Figure 1(d) assumes that the ellipsoids are aligned with their long axis horizontal, and even

Figure 1(f) assumes that the ellipsoids are on average horizontal. But is this reasonable? Afterall, development of dynamic turbulence relies on the Richardson number being less than ~0.25, so it relies on the wind-shear dominating over stability. So if the effect of stability is reduced, then why should the mean alignment of the eddies have to be exactly horizontal?

Figure 1(e) becomes a better representation! Even better would be

Figure 1(e) with some random fluctuations super-imposed (like

Figure 1(f)). Indeed, the average tilt of the eddies might be partially defined by the wind shear, or some ratio of wind-shear to buoyancy - or even on the Richardson number itself.

So we need to accept model 1(e), with some allowance for quasi-random fluctuation about the mean tilt. The question now is - how will such a model affect the radar measurements? For that, we need to turn to

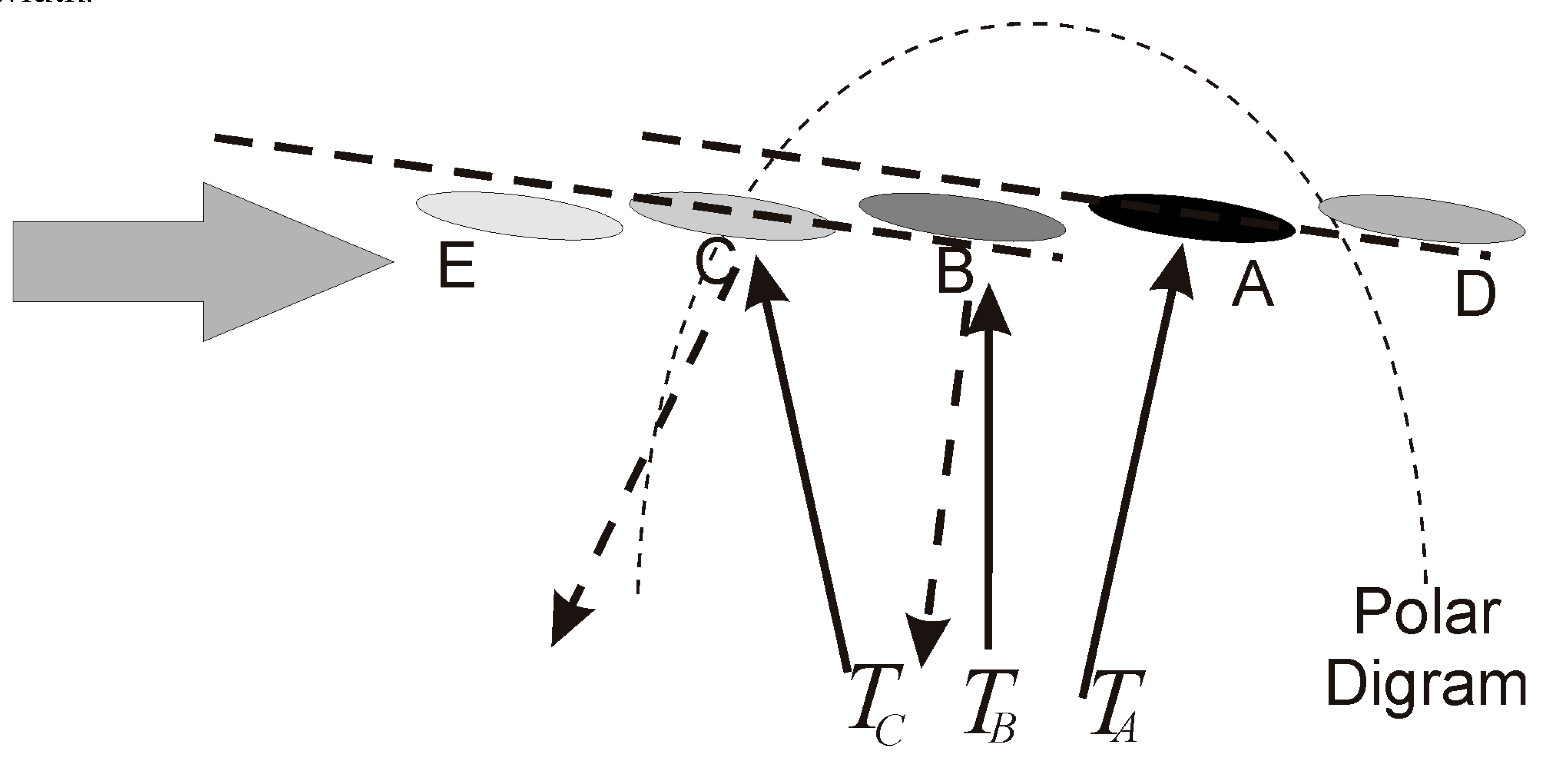

Figure 9.

Figure 9 shows a stream of tilted ellipsoids blowing through the beam. It is assumed that the wind is purely horizontal. In this case we have used downward sloping eddies (mean alignment is shown by the sloping broken lines). This tilt direction is the opposite to

Figure 1(e) (downward here compared to upward there), but the concept remains. The separate “eddies” drawn in the figure can be considered as all co-existing, or can be considered as a single eddy at various points in time.

It is worth noting that a single eddy travelling at 30 m/s for a period of 10 seconds will travel 300m in that time. At 5 km altitude, this corresponds to an angular change of

tan−1(0.3/5) = 3.5o. So such an eddy has time to cross from one side of the beam to the other in 10s. Hence even a single eddy will travel from C to D in

Figure 9 during a typical data-acquisition time. If longer acquisition samples of say 20–30s are used, the same is still true - the eddy will exist at different points within the beam during a typical acquisition, and the positions will cover a substantial portion of the beam-width.

Figure 9.

Relation between tilted small-scale scatterers (represented by ellipsoids), the radar polar diagram, and the consequences of different radar-signal paths scattering from these scattering ellipsoids.

Figure 9.

Relation between tilted small-scale scatterers (represented by ellipsoids), the radar polar diagram, and the consequences of different radar-signal paths scattering from these scattering ellipsoids.

Now consider scatter from the beams. Pulses from the transmitter are transmitted radially, and will follow trajectories represented by T

A, T

B and T

C as examples. Each strikes a different eddy (or, if there is only one eddy, the radar-paths strike the eddy at different times). Due to the alignment of eddy “A”, it reflects most of its energy back to the receiver. But eddies B and C reflect energy off-axis and so the signal received at the radar will be diminished.(While we speak of “reflection”, in reality the process should be treated as a scattering process, as in

[19,37,38], but this simple colloquial discussion is adequate here).

From

Figure 9, then scatter will be strongest from eddy “A”, and the more oblate the ellispoids, the more dominant will be the effect of eddy “A”.

Hence despite the fact that the eddy moves uniformly through the beam, scatter will be dominated by eddy “A” due to its alignment. The radial component of velocity at this point will be positive (away from the antenna aray), and so the Fourier spectrum of the time-series will be dominated by positive frequencies. Hence the radar analysis will produce a positive velocity, even though there is no vertical motion. Furthermore, the radial velocity “measured” will be proportional to the horizontal wind. This is all consistent with our studies.

At the current point in time, this model seems to best explain our data. Turbulence is a frequent occurrence in the atmosphere, so the radar-effects produced by this mechanism can easily persist over the course of months and years, as seen in our results. Not only does the model match our data, but our data allows us to quantify the mean eddy-tilting in patches of turbulence to an accuracy of 0.2o and better - a new capability not previously available, and giving new insights into the nature of atmospheric turbulence!

Three final comments need to be made. First, we should note that the “tilt angle” we measure will be moderated by the beam itself (see

Figure 9), and some of the larger angles could even be a little larger in reality. Correction of the measured tilt to produce the true tilt is beyond the scope of this paper, though techniques like those presented in

[19,37,38] can be used to make these adjustments.

Second, we should also note that many previous authors have used vertical velocities measured with a vertical beam to study short-term gravity wave activity. As long as the mean wind is relatively constant during the study, or has an identifiable behaviour, then the effects presented in this paper can be successfully removed, and the remaining short-term fluctuations can still be used for gravity-wave studies. However, studies of long-term behaviour of the mean vertical wind must include corrections for the effects presented here-in.

As a final (third) point of interest, it is interesting to compare the results here to the results from

[29]. That paper looked at the distribution of regions in the atmosphere where gravity waves dominatedm compared to regions where large-scale 2-D geostrophic turbulence was more prevalent. Both Walsingham and Harrow appeared to have significant gravity wave production, especially in Summer, due presumably to lake breezes. Both sites showed more gravity waves than the other sites used in that study, and both show significant wave production in the lowest 2 km. Comparing these results to

Figure 8 here-in, it is seen that our tilts become steeper at > 6 km in Summer at Harrow, and at 6-9 km at Walsingham. These results would be consistent with gravity wave production near the ground, free growth to ~6 km altitude, then breaking of the waves to produce strong turbulence and subsequent secondary gravity-wave growth at 6 km and upward. The large-ish layer tilts seen in

Figure 8 of this paper occurring at similar heights to the active gravity-wave growth at 6 km may be further support for our model.