1. Introduction

The concept of complexity, very common in natural sciences, provides that, analogously to physical systems, human society and economical way of production are characterized by interactions and feedback loops that constantly changes systems making the system characterized not by a general equilibrium, but metastable partial equilibria, emergence of new processes, hierarchical-base order-generating rules [Barrat et al. 2012; Chen 2016; Jensen, 2022].

In a complex economic system, existing structures of interaction are in constant mutation as individual agents contact and influence one another and, by doing so, reshape the macro environment in which socio-economic relations unfold. On the contrary, the theoretical framework of economics has long been that of “equilibrium”. This notion appeared as early as the first decade of the 19th century when mathematicians started to formulate economic laws after physical sciences. In the last quarter of 19th century, French economist Léon Walras presented a new method for economic analysis. In 20th century, his method called “general equilibrium theory” became the most powerful research program and most economists of this century wanted to analyze any economic phenomenon in this theoretical economic analysis [Kuenne, 1992; McKenzie, 2008]. On the contrary, when applied to describe economic and social processes, dissipative structure sometimes takes the form of stationary state but it is very different from equilibrium.

The concept of dissipative structure is important for economics, because it makes possible to have new idea how economic system works. In the equilibrium framework, boundary conditions are imposed as constraints of the system. While, in the dissipative framework, boundary conditions are not directly related to the speed of the consumptions or the extent of employment. It is instead the internal structure which determines, like mentioned dissipative structures of open systems, volumes and speeds of economic quantities [Georgescu-Roegen, 1970; Meadows et al, 1972].

The historically prevalent mode of production in each era can be considered as complex adaptive systems [von Bertalanffy, 1972; Hayek, 2014; Lewis, 2015], as they exhibit self-organization, interdependence, space of possibilities, co-evolution and self-replication [Turner and Baker, 2019]. Self-organization in non-equilibrium systems has been known for over 50 years. Under non-equilibrium conditions, the state of a system can become unstable and a transition to an organized structure can occur. Such structures include oscillating chemical reactions and spatiotemporal patterns in chemical and other systems, as, for example, enzymatic cycles. Because entropy and free-energy dissipating irreversible processes generate and maintain these structures, these have been called dissipative structures.

Dynamic self-replicating processes occur outside of thermodynamic equilibrium underlie many forms of adaptive structures in natural systems as a manifestation of dissipative structures. A dissipative system is a thermodynamically open system which is operating out of, and often far from, thermodynamic equilibrium in an environment with which it exchanges energy and matter. Relatively little, however, is known about the principles that govern economy and social processes and the ways in which dynamic self-replication extended to a capitalist way of production. Society, as a broadly defined system, is a complex adaptive system as it corporates a number of interrelated subsystems. For example, a society will have subsystems for provisioning (the economy), for rearing its young, for making community decisions, and for defending itself from internal and external threats. Social subsystems do not stand alone, rather, they are intertwined with other social systems and all interact with non-social systems, in particular, the natural environment and technology which, while not a social system, is a social product. Each system or subsystem involves the coordination of various processes working together to cause the system to accomplish its goal.

The evolution process for commodities, technologies, and institutions is defined broadly as a “replicator” because such entities have the tendency to produce copies of themselves. This imply that in a capitalist society the controllers of the means of production having the greatest benefits from the realization of profits, tend to maintain positions of privilege and control of the means of production by introducing technological innovations. Such technological progress raises the composition of capital, consequentially, the rate of profit would decline in the long run. The mechanism for the introduction of new technological innovation is self-replicating, as already observed by Marx, because independent of the will of capitalists, if they want to survive to the technological innovations of other capitalists. Self-replication mechanisms are ubiquitous in nature, it is, for example, the engine that drives all biologic evolution, including neoplastic evolution. Analogously, in economy, an example of self-replication can be found in the mechanisms of derivatives market efficiency [Awrey, 2016]. These mechanisms respond to information, digital framework such as high trade frequency and other problems not generally encountered within conventional stock markets. These problems reflect important differences in the nature of derivatives contracts, the structure of the markets in which they trade, and the sources of market liquidity. Predictably, these problems have led to the emergence of very different mechanisms of market efficiency. Another example, it is the formation and progression of financial bubbles [Sornette and Cauwels, 2014]. A financial bubble is characterized by a period of unsustainable growth, when the price of an asset increases ever more quickly, in a series of accelerating phases of corrections and rebounds, where the prices follows a faster-than-exponential power law growth process, in some cases, accompanied by log-period oscillations. The faster-than-exponential power law growth process is a manifestation of self-replicating dynamics. This is because the log-periodic power law emerges spontaneously from the complex system denoting financial markets, where feedback mechanisms, hierarchical structures, specific trading dynamics and investment styles operates in a combined continuous reciprocal exchange.

This idea closely aligns with the principle of conformity (and self-replication) on which we build our approach. Indeed, the convergence of evolutionary and developmental economics ideas is in line with the corresponding cross-fertilization of evolutionary and developmental biology in evo-devo biology. However, the dynamics of replicators is an evolutionary process where selection plays a dominant part, a bottom-up view of economic processes. In developmental biology the basic principles of self-replication/conformity and individuation are the conceptual starting points on which to infer large scale, general structures that may naturally arise in economic systems independently of a justification in terms of competition.

When LTFRP is studied as time series, it shows unit root non-stationary dynamics, that is a manifestation of stochastic behaviour in complex systems. An indirect measurement of such stochastic dynamics is the manifestation of power laws [Markovic and Gros, 2014]. Power laws, (a functional relationship between two quantities, where a relative change in one quantity results in a relative change in the other quantity proportional to a power of the change, independent of the initial size of those quantities) are ubiquitous in economy, incidentally, the productivity of capital and profit rate follows a power-law function of time, and social behaviours. Power laws reflect a pattern of organization and change that is typical for complex systems. Hence, familiarity with their properties offers some clues to the expected character of any complex system [Carchedi, 1995].

In this paper, we suggest that LTFRP as proposed by Marx is a manifestation of capitalistic way of production as a self-replicating dynamics based on the tendency of profit rate to fall and the counter-tendencies to contrast this intrinsic falling dynamics due to dissipative nature of human society. Marx’s claim in Volume III of Capital that there is a tendency for the general rate of profit to fall with the development of capitalism [Marx, 1993]. This is one of the two laws of tendency claimed by Marx. The another one is the concentration and centralization of capitals [Marx, 1993; Brancaccio et al, 2018]. Marx’s analysis evidenced that the growing size of firms, and the subsequent dwindling of competition, were the basic mechanism for the evolution of monopolistic or anticompetitive power. Hence, the capital has the inclination for concentration and centralization in the hands of the richest and big capitalists. The concentration and centralization of capitals are two main capital accumulation techniques, which, incidentally, could be considered a self-replicating mechanism of capital based in this case on the self-expansion. Such concentration and centralization of capitals can be clearly detected at this modern time in the enormous occurrences of the mergers, acquisitions and conglomerates [Brancaccio et al. 2018]. While there is a general consensus, even among mainstream economists, on the general dynamics of the concentration and accumulation of capital among fewer and fewer owners, the debate on the effective existence of LTFRP has been very controversial over time. In particular, the controversy has been traditionally fueled by the lack of adequate abstraction tools or adequate econometric tools capable of overcoming the empirical analyzes gradually proposed [Dobb, 1939; Sweezy, 1942; Gilman, 1957; Okishio, 1961; Mandel, 1980; Roemer, 1981; Foley, 1986; Michl, 1988; Reuten, 1991; Shaik, 1992; Duménil and Lévy, 1993, 1995; Foley and Michl, 1999; Wolff, 2001, 2003; Duménil and Lèvy, 1993, 2002a, 2002b, 2003; Basu and Manolakos, 2012; Park and Yang, 2023b]. The debate around the Marx’s theory of the falling rate of profit has focused on two main issues. Namely, whether the profit rate really falls in the long run, and, in the case this happens, what is the main reason, i.e., the fall in the surplus-value rate or the rise in the composition of capital?

Okishio proposed a critique of Marx’s theory of LTFRP by asserting that under Marx’s formulation, the profit rate must rise in the course of adopting new technologies [Okishio 1961]. The Okishio Theorem states that if capitalist producers adopt a new technique of production only if it reduces the cost of production at existing prices, then Marx’s results cannot be sustained. This is because if capitalist producers choose to adopt a new technique of production only if it is cost-reducing at current prices and the real wage rate remains unchanged before and after technical change, then the long run rate of profit in the economy will rise. However, this critique is based on the supposition that the real wage is constant, and this is a restrictive assumption, of which there has never been any evidence [Duméneil and Lévy, 2003]. With the extended model of Okishio’s approach, Foley et al. suggested that Marx-biased technical change involves that is the wage share remains constant, and consequently the surplus-value rate remains constant, the real wage rises proportionally to labor productivity and the profit rate must eventually fall [Foley et al. 2019]. However, also in this case, this model is incorrect because the wage share fluctuates in real capitalist economies. In a model-based approach, Duménil and Lévy introduce a dynamic model to describe the tendential fall in the profit rate, where the tendential fall is essentially due to the specific features of innovation adopted to yield a larger profit rate [Duménil and Lévy, 2003]. Based on this dynamic model approach, recently, Park and Yang introduced a feedback mechanisms for the restoration of principal path of profit rate [Park and Yang, 2003a,b].

However, in addition to such powerful models, an econometric approach to TLFRP should take account another largely underestimated problem. As evidenced first by O. Morgenstern, the accuracy of economic data is a problem for all fields of economics [Morgenstern, 1950; Bagus, 2011]. In line with this critical issue on economical quantification, recently, Mügge and Linsi evidenced that the transnationalization and the digitalization of economy activity has drastically reduced the reliability of official economic statistics, which still operate on national territories and with material production [Mügge and Linsi, 2021]. This has generated the difficulty to manage, for statistical practice, unambiguous data about the comparison over time and across countries. Since the problem of the accuracy of economic calculations involves some key issues that reverberate into more general general questions of political economy, its effect on the rate of the profit is beyond the scope of the present paper, here we prefer only to report this critical issue on which to focus a dedicated study at a later time.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section is dedicated to describe profit rate, it tendency to fall of its principal path and the countertendencies as restoration source for the principal path as a manifestation of self-replicating system. The subsequent section details on the model used to simulate the profit rate for U.S. economy for the time period under investigation (1945-2016). Hence, the section results show the numerical value for time trend of falling rate.

2. Profit Rate, Tendency and Countertendencies as Manifestation of Self-Replicating Dynamics

Marx’s analysis of historical tendencies is intrinsically connected to other basic components of his work, notably the theories of technical changes, wages and accumulation. While determination of wages represents a critical issue, the theory of technical changes can be satisfactorily described within the classical Marxian evolutionary model [Duménil and Lévy, 2003]. Based on the analysis of Duménil and Lévy, and Park and Yang, in this section, we introduce the self-replicating dynamics to describe the trajectories denoting the TLFRP. While Duménil and Lévy described trajectories satisfying stable equilibria (in their analysis, equilibrium refers to stable point of a dynamical model), Park and Yang built a dynamical model on feedback mechanisms to elucidate Marx’s theory. Their analysis highlights how the effort to maximise the profit rate, implemented by designing a control law, can lead to the gradual decrease in the rate of profit in the long run.

In both the model, if the economy tends to deviate from principal paths under the effect of technological innovation, there are mechanisms that push the variables back to their principal paths, that is, ultimately, exactly the notion of tendency of law, or equivalently, a self-replication mechanism. The impact of innovation on principal path of the rate of profit is twofold, the innovation gives basic advantages to capitalists, but, on the otherwise, hardly, innovations increase simultaneously the productivities of labor and capital. If the conditions of innovations are assumed constant, the profit rate declines exponentially. As a result of such rapid falling, the rise of the capital stock is bounded above, and both output and employment diminish. To address the LTFRP, we focus the attention of the dynamics the profit rate for a country of interest, in our case, U.S. economy that is connected to a larger system, the whole word, that represent the environment that tend to perturb the economic factors that tend to deviate from the principal paths, triggering crises and mechanisms that push the variables back in order to restore the principal paths. In

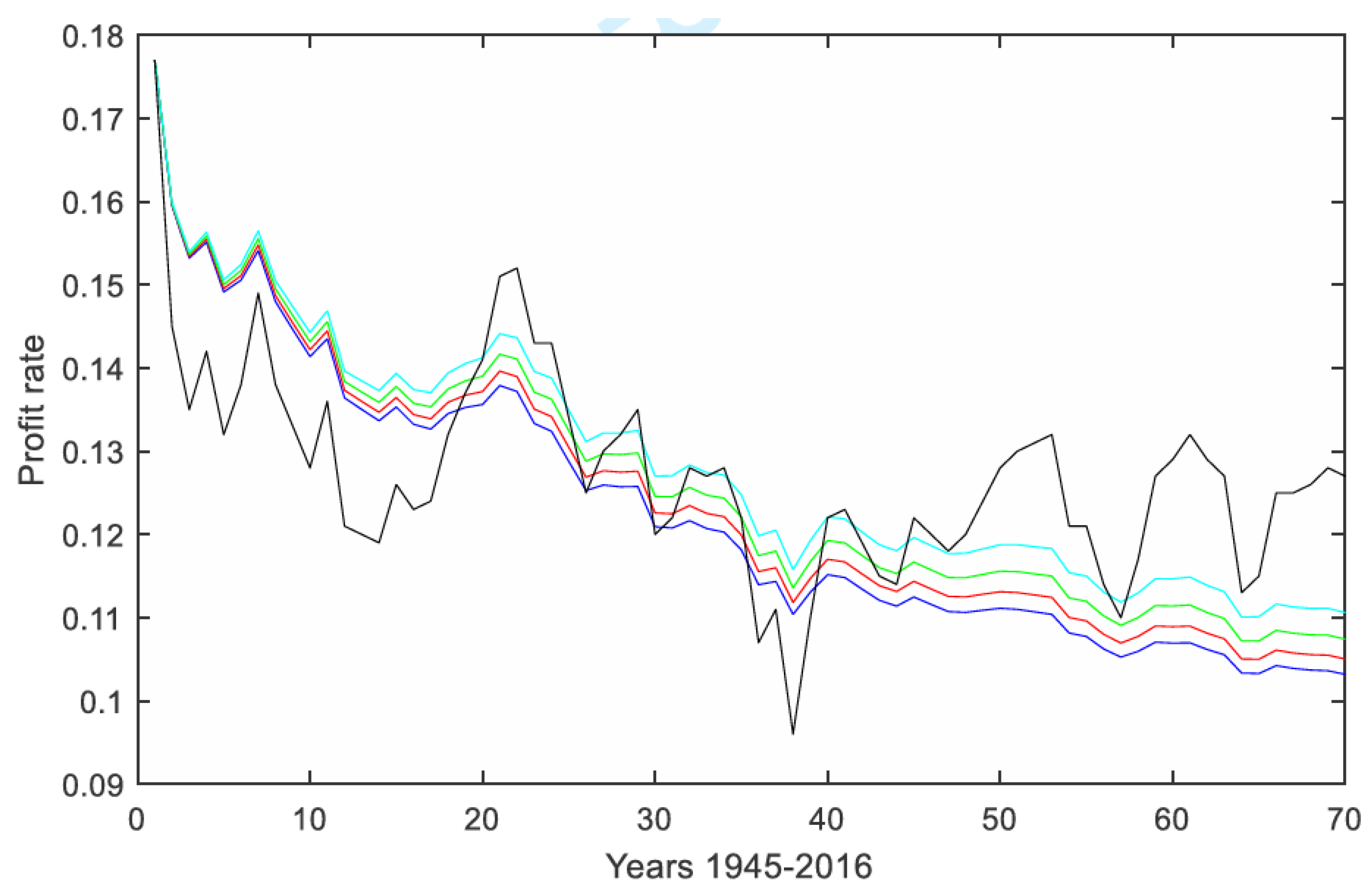

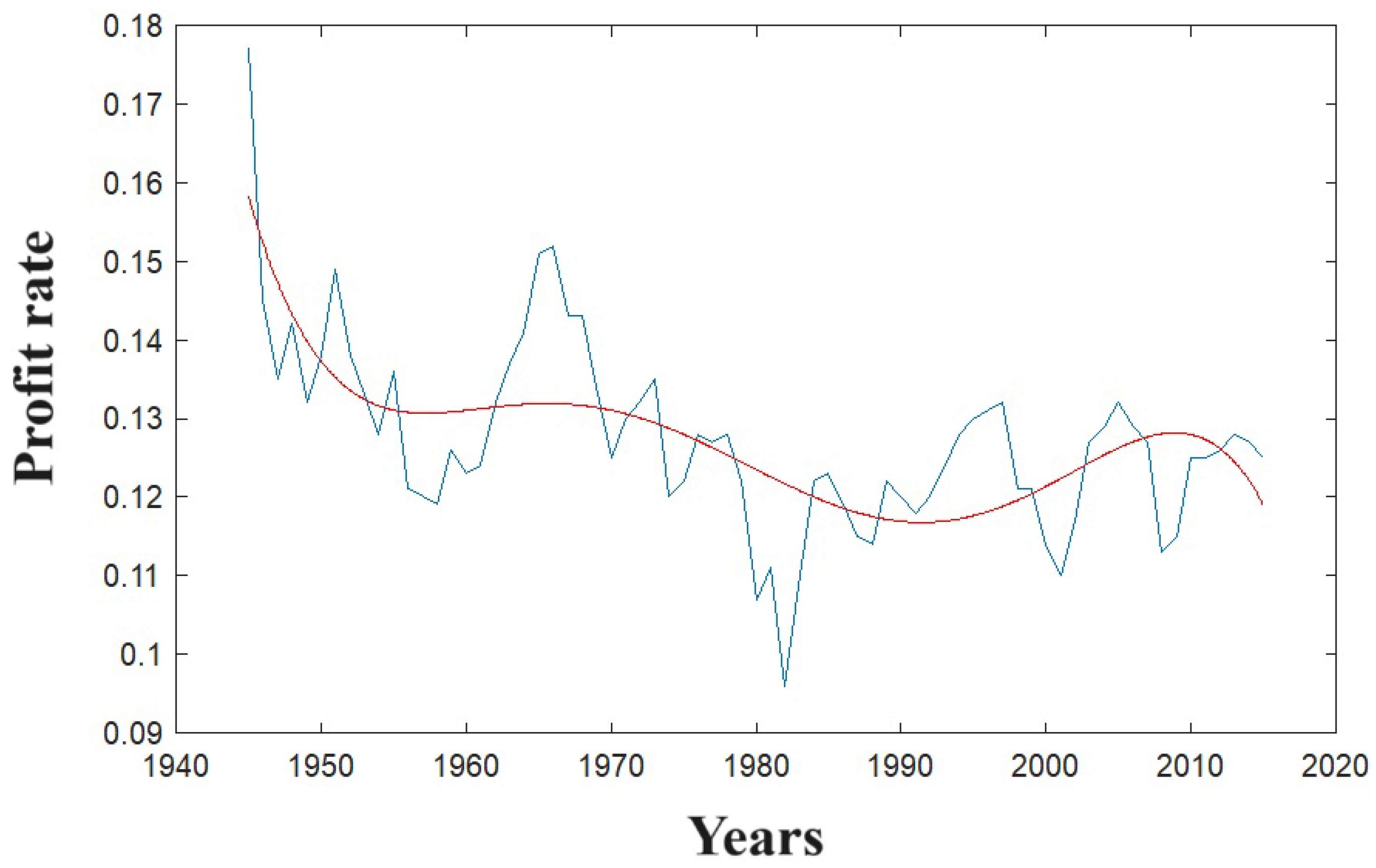

Figure 1, we report the profit rate for USA economy since 1945 to 2016.

Basu and Vasudevan investigated the US economy since the Civil War and evidenced that the transformation of what we denote as the conditions of innovations and the difficulty to innovate seems to be basic factors to account the successive phases of rise and decline in the profit rate [Basu and Vasudevan, 2013]. However, for example, as the basic innovation introduced by the invention of train and railway lines played a first fundamental role during the Civil War its impact on the overall USA economy manifests itself in the following decades, making it difficult to understand how such specific invention of the train alone impacts the overall profit rate. The self-replicating nature of generation and restoration of principal path for profit rate can be analyzed by looking at the dynamical combined effects of tendencies and countertendencies. The broad set of variables analyzed by original work of Marx include i) labor productivity. With the progress of productive forces, the production of a given commodity requires less and less labor. The tendency of the profit rate to fall, is an indirect demonstration of progress of labor productivity. Paradoxically, the growth of labor productivity implies a declining profitability. ii) The value-composition of capital, i.e., the ratio between the constant capital (means of production) c, and the value of labor-power, or variable capital, v. The value-composition of capital reflects the technical composition of capital and its rise is a crucial feature of technical changes. iii) Accumulation and growth. As suggested by Marx, acceleration of profits accumulation and the growth rates of capital are factors that can be associated to falling profit rate. In addition, a declining profit rate should be reflected in a declining growth rate of fixed capital since a constant share of profits is accumulated at any cycle. It is obvious that this behavior must be considered over long periods due to tendencial nature of such factor, overcrossing shorter–term patterns of events, as structural crises and recessions [Carchedi and Roberts, 2018].

Once outlined the leading arguments for the existence of a tendency for the rate of profit to decline over time, Marx immediately evidenced the existence of countertendencies in real capitalist economies. The role of such countertendencies is to temporarily dampen or reverse the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. As remarked by Basu and Vasudevan directly from The Capital: “The classical countertendencies originally mentioned by Marx are: I) the increasing intensity of exploitation of labor, which could increase the rate of surplus value; II) the relative cheapening of the elements of constant capital; III) the deviation of the wage rate from the values of labor power; IV) the existence and increase of a relative surplus population; V) foreign trade cheapening of consumption and capital goods through imports; VI) the increase in share capitals by joint-stock companies, which devolves part of the costs of using capital in production on others” [Basu and Vasudevan, 2013; Marx, 1993].

With respect to original Marx’s analysis, the capitalism evidenced two other prominent countertendencies: the economy of scale and the role gradually growing, starting from the previous century, of Keynesian militarism, i.e., the part of public budgets dedicated to military spending. The economy of scale is often a response to the introduction of new productive technologies making the reduction of productive sites for companies more advantageous. Analogously, companies can achieve economies of scales by increasing production and lowering costs, because costs are spread over a larger number of goods. On the side of warfare as a countertendency, military spending stimulates aggregate demand directly through government spending and, indirectly, through multiplier effects on private consumption and investment. Without such stimulus, capital and labour would remain unemployed [Custers, 2010]. The famous Bretton Woods conference from which the agreements of the same name arose was centered on the fact that military spending was the response in the 1930s to the crisis of 1929. The consequence of this expense was the Second World War [Boyce, 1989]. In Bretton Woods conference it was envisioned an international monetary system that would ensure exchange rate stability, prevent competitive devaluations, and promote economic growth. After the end of the Second World War, the so-called military-industrial complexes grew dramatically, dominating and influencing, with their weight, the production and the technological development during the Cold War and after, still today.

The aforementioned counter-tendencies as they mitigate the tendency for the rate of profit to fall must be explicitly incorporated into an econometric analysis and their effects on the trend of profitability must be controlled in order to achieve statistically significant conclusions on the declining trend over time.

3. The Model of Law of Tendential Fall in the Rate of Profit According to Marx

Here, we describe the dynamical model of the rate of profit, which results are displayed in next section. According to Marx, the rate of profit at a discrete fiscal year

t can be expressed as

where

α(

t) represents the surplus-value rate, that counts the intensity of exploitation,

c(

t) denotes the constant capital, i.e., the means of productions, and

v(

t) is the variable capital. The ratio

c(

t)/

v(

t) is the composition of capital. Eq. (1) says that the rate of profit decreases as the ratio

c(

t)/

v(

t) increases, when the surplus-values is constant, or the rate of profit can decrease when the surplus-value increases less that the increase of composition of capital.

It is well known that a controversial issue about this law of the rate of profit related to the choice of the technique is a long-standing debate. As mentioned, Okishio proposed a critique of Marx’s theory of the falling rate of profit by asserting that under Marx’s assumptions, the profit rate should rise in the course of adopting new technologies [Okishio, 1961]. Based on the Sraffa-model, this critique supposes that the real wage is constant, which is realistic in capitalist economies that involve the increase in real wages. By extending the Okishio’s approach, Foley et al. suggested that Marx-biased technical change involves that if the wage share remains constant, and correspondingly the surplus-value rate remains constant, the real wage rises proportionately to labor productivity and the profit rate could eventually fall [Foley et al, 2019]. However, the data show that the wage share fluctuates in real capitalist economies [Park and Yang, 2023].

The profit, p(t), is hence the product of surplus-value rate and variable capital

Let

l(

t) and

w(

t) be the amount of workers and the average wage per worker at a certain fiscal year

t, then, the variable capital can be written

v(

t)=

l(

t)

w(

t). The total value created by the workers’ labour,

y(

t), is the sum of profit and variable capital

The time evolution of production function of U.S. economy in the period of interest is available,

Figure 2, and the Cobb-Douglas production function, Eq. (4) well fits the temporal trend

where

a(

t) is the state of technology of production outputs entailing that a larger

a(

t) produces a larger output with a given number of workers and constant capital and 0<

m<1.

The state of technology in Cobb-Douglas relationship is commonly considered to depend by a constant technological progress, so that a(t)=a0eεt, where ε>0 is, precisely, the rate of technological progress. In the results section we will obtain the rate of technological progress as a function of time, conditioned by technological cycles that account for the life-time of production technologies. The exponent m in (4) needs some comments. In the neoclassical mainstream, m is considered to be the profit share. This is because a basic hypothesis of neoclassical economics is that the marginal product of labor is equal to a real wage, which ensures the profit maximization [Hamilton, 1988]. On the contrary, the Cobb-Douglas function has been criticized by arguing that in reality the average wage is greater than the marginal product of labor [Foley et al. 2019]. Since Cobb-Douglas relationship provides that the profit rate maximizing technique at a given wage will always combine labor and capital in proportions such that the marginal product of labor is equal to wage. However, this criticism is valid only if it is supposed the neoclassical hypothesis, i.e., the equivalence of m with profit share. However, Cobb-Douglas function satisfies the assumption that the increase in the composition of capital is another expression for the development of the social productivity of labor, as the growing use of machinery and fixed capital generally enables additional raw and semi-finished materials to be transformed into products in the same time by the same number of workers and then with less labor.

In turn, as wage model we adopt the model, suggested by Duménil and Lévy, wherein is assumed that the growth rate of wage is proportional to growth rate of employed workers [Duménil and Lévy, 2003] that provides that growth rate of average wage is proportional to growth rate of number of workers:

where

ρ(.) denotes the growth rate of (.),

δ accounts the effect of the employment increase on the wage, and in some way describes the workers’ bargaining skills, and

λ amends the proportionality of (5) including the possibility that even though employement decreases, wage may increase. So the profit rate (1) can be written as

The growth rate in Eq. (5) denotes the changes of a variable,

x(

t), as a function of fiscal years, due to discreteness of time can be written

x(

t+1)=

x(

t)+Δ

x(

t), and the corresponding growth rate is

ρ(

x(

t))= Δ

x(

t)/

x(

t), where Δ

x(

t)=

x(

t+1)-

x(

t). By using the properties of growth rates, that for small changes are very close to logarithm-function properties,

ρ(

x/

y)=

ρ(

x)-

ρ(

y), and

ρ(

xy)=

ρ(

x)+

ρ(

y), we can write the growth rate of Eq. (6) as

that is very close to relationship derived by Park and Yang, except the assumption that

ε is a function of time and (1+

α)/

α≅1, but the dependence of growth rate of profit by γ is anyway evident. The rate of technological progress,

ε, should be a step-function denoting the introduction in productive process of new disruptive technologies. However, since there not analytical expression for such rate, we adopt a constant value. Since Marx’s theory of the LTFRP is the long-run tendency, a crucial aspect is the time intervals in which we observe phases of decline and rise. Being the time trend of the rate of profit, as well as the countertendencies, unit root nonstationary processes, the effects on short run present a certain persistence. Such persistence will emerge on long waves on the time series. Because the long-run decline is based on the repetitive rise and fall in the short run, the derivation of the conditions for such tendential decline must be evidenced and eventually including whether there are persistent effects between one pahse of decline and another in short run. Repetitive rise and fall in the short run can be described as follows. Let

ti+1=

ti+1 for

i=0,1,…, the time correspondent to any fiscal year and let

r(

t0)>

r(

t1) the condition of decrease rate for two initial years. We can write

ri+1=(1+ρ(

ri))

ri, so that

Being the long run of rate of profit is characterized by repetitive rise and fall, in order for the profit rate to decrease in the long run, it must decrease at successive local minima, for example,

r1>

rn+1, which implies

. Now, let us consider what happen if we consider two local maxima of profit rate, for example,

r(

ti-1)<

r(

ti) and

r(

ti) >

r(

ti+1), i.e., the rate of profit starts to fall at

ti after the rise at

ti-1. The year

ti is a local maximum. For two successive minima years,

t1 and

tn+1, and two successive maxima,

t1+p and

tn+q, where 0<

p<

n and

q>1, the condition for the rate of profit to decrease in the long run time is

which implies that the maximum rate of profit generated for two successive minima is larger than that produced between

tn+1 and the subsequent minimum. Since both the condition can be synthesized by the growth rate of profit as expressed by Marx LTFRP

the tendential fall in the profit rate in the long run time is ultimately achieved by the gradual increase in the composition of capital in the long run.

An elementary model of Self-Replication mechanisms involve a two reaction processes as follows [Gijima and Peacock-Lopez, 2020]:

where

P represents a self-replicated product, for example, a commodity, and

A and

B could denote constant capital and the variable capital, respectively. In the initiation step, the production of

P could be supposed as linear in the concentration of

A and

B. This includes also that, at initial step, the probability to combine

A and

B to produce

P is low (small

k1). The structure of the product-commodity P is such that once it is formed, it preferentially binds

A and

B in a conformation that facilitates covalent bonding between the

A and

B molecules to form another

P commodity. The newly created commodity and the original precursors then split apart and independently catalyze further commodities. A sort of such mechanism was suggested by Sraffa in his seminal book

Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities [Sraffa, 1960]. After an initial transition phase, dominated by the linear dependence by

A and

B, where the total rate is proportional to commodities produced, an exponential growth can take place expressed by a series of elementary reactions, denoting intermediated sub processes, where commodities generates intermediate rates and the final step in the mechanism

is taken to be the rate determining step, meaning that the rate k should be first order with the respect to the intermediate

I. The overall process can be formulated in an expression very close to Eq. (1) where the products/commodities

P include the surplus-value rate and the precursors

A and

B can be associate to constant capital

c(

t) and variable capital

v(

t). The processes of self-replication are generally characterized by an initial dynamics, that provide sub-processes, where intermediate rates that affect the products

A+

P→

P1,

B+

P1→

P2 each characterized by its own rate, that lead to a subsequent stable cycle, where a robust self-replication assumes a cyclic shape, and losing factors are counterbalanced by feeding factors guarantying stability on long time. At the end of overall process, the rate of the system can be expressed as a ratio where the products are numbered (in our case the goods) and the quantity

A and

B dominating which generate the final products, in a way not dissimilar to Eq (1). Once, we have obtained the relevant relations for the self-replicating mechanism, we could consider the modifications due to an open system, where the self-replicating dynamics are central to our analyses. In open systems, self-replications of dissipative structures, as in most cases of chemical reactions where a reservoir continuously pumps into the reaction mixture at a constant rates, or, similarly, excess of precursors of

A and

B, which decay with a certain rate, can be described equivalently in the long-run tendency of rate of profit by the role of countertendencies to counteract the trend decline, i.e. if the economy tends to deviate from principal paths, there are mechanisms that push the variables back to their principal paths, that is, ultimately, exactly the notion of tendency of law. Self-replicating processes display time series with unit root non-stationarity, this implies that when such a series begins to decline, this fall continues for some time before a reversal of the declined trend. Likewise, when beginning its ascent phase, it continues to rise for a substantial period of time before declining process starts again, so generating typical long waves behaviour around mean path. The analogy of self-replications mechanisms for tendential laws of capitalism could be approached by a more quantitative point of view, but this approach is beyond the scope of the present paper. In the next section, we will detail on numerical results achieved by including both an econometric model and a numerical model à la Marx that identify the accumulation composition of capital as the basic source of LTFRP for U.S, economy in the period 1945-2016.

4. Results

In this section, we approach the study of the non-equilibrium nature of the rate of profit by applying two different numerical methods. The first one is based on an analytical expression for the rate of profit, as suggested by Park and Yang, based directly on Marx’s original formulation [Park and Yang, 2023a,b] and an econometric issue on the data in

Figure 2 of the U.S. economy in the period 1945-2016 [Duménil and Lévy, 2016] where the profit rate is a time series to which to apply the multivariate regression methods, similarly to what done by Basu and Manolakos in order to demonstrate that such data represent a non-stationary unit root process and to derive the trend parameters [Basu and Manolakos, 2012]. The two models are intimately interconnected one each other.

Park-Yang approach introduces a feed-back mechanism on the rate of profit based of the interplay between the surplus-value rate and the value composition of capital. The relevant contribution of such model is that the feed-back mechanisms accounts for the role of countertendencies to try to report in due time the rate of profit on the principal path. By adopting this approach, firstly we have fitted the experimental data for production function,

y(

t), as given by

Figure 2 for U.S. economy with Cobb-Douglas relationship, Eq. (4), in order to derive the state of technology,

a(

t), the exponent

m, and the constant capital,

c(

t). We have adopted the following initial conditions in 1945, the number of workers in U.S. for means of production was about 75 million,

l(1)=75×10

6 (whose number will decline linearly to 8.3 million in 2016), the total capital stock about 180 billion dollars,

c(1)=18×10

10. In addition, the average wage per worker about 2370 dollars. The function of the state of the technology

a(

t)=

a(1)e

ε(t-1) is a key factor for productive processes, however, the difficulty to connect the technological evolution and its impact on the productive processes and hence the incidence on the rate of profit, forces us to adopt some simplifications, for example, to consider the rate of technological progress,

ε, as a constant. By following Park and Yang, our numerical model uses the set of parameters:

a(1)=294,

ε=0.0355, the average accumulation rate

β=0.54, a wage model, Eq. (5), with

δ=0.262 and

λ=0.0458, and finally the average profit rate varying in the range 0.29<

m<0.33 [Park and Yang, 2023a, and 2023b]. In turn, using a linear trend for the number of works for mean of production, we can calculate the constant capital c(t) from Cobb-Douglas Eq.(4), after linearization via log

c=(log

y-log

a0-

εt-(1-

m)log

l)/

m. Once

c(

t) is known, accumulation composition of capital, Δ

c(

t)/Δ

v(

t) and the surplus-value rate from Eq. (7). The last two curves, normalized to unity, are reported in

Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows that while the surplus-value rate (continue line) remains approximating constant within a narrow range, the accumulation composition of capital (dashed line) shows a robust exponential increase albeit with some local oscillations resulting from the countertrends implemented, which however do not modify the substantial growth over time. These results show the validity of Marx’s assumptions on the tendency of profit rate to fall in the long run and on main reason of such tendency due to rise of composition of capital. In addition, there is no accumulation composition of capital, γ, that gives

ρ(r)>0 in the long run. As said, the second approach is based on the possible highlighting of a negative long run trend in the period 1945-2016 taking the data from the time series in

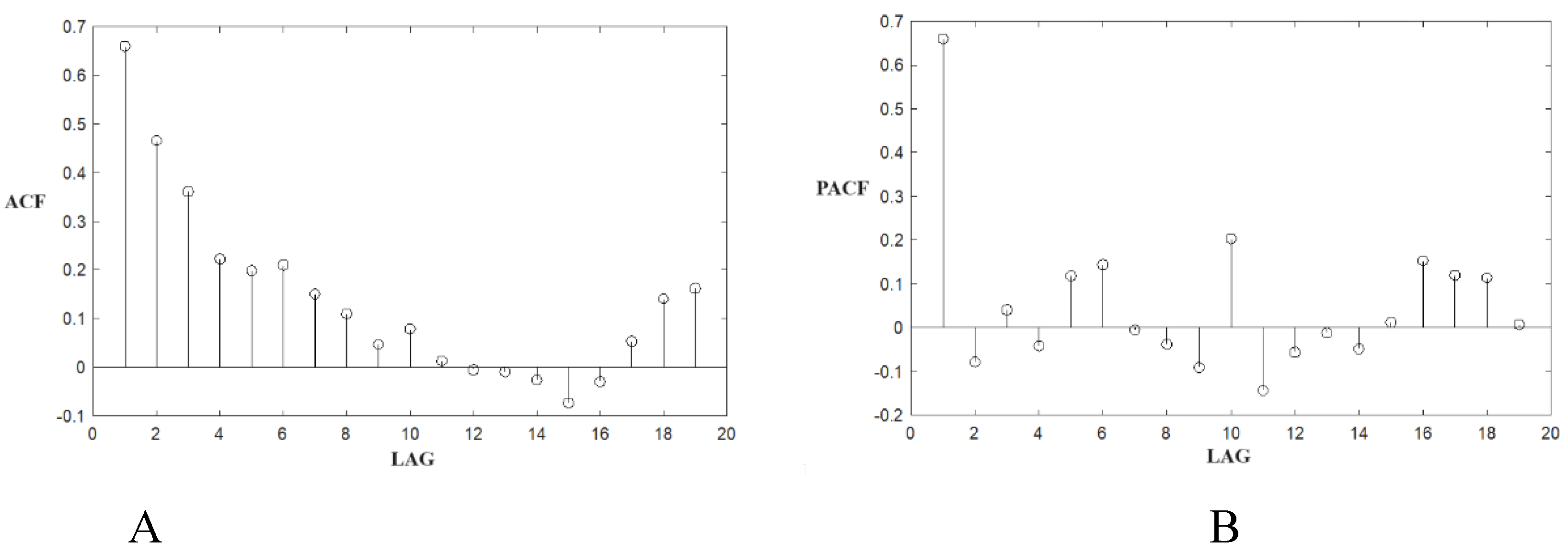

Figure 1. First we demonstrate that rate of profit is a nonstationary process, basic condition to be a self-replicating process. Following the econometric investigation made by Basu and Manolakos [Basu and Manolakos 2012], we apply the Box-Jenkins approach to the time-series [Box and Jenkins, 1979].

Figure 4 shows the sample autocorrelation function (ACF) for the rate of profit

rt and

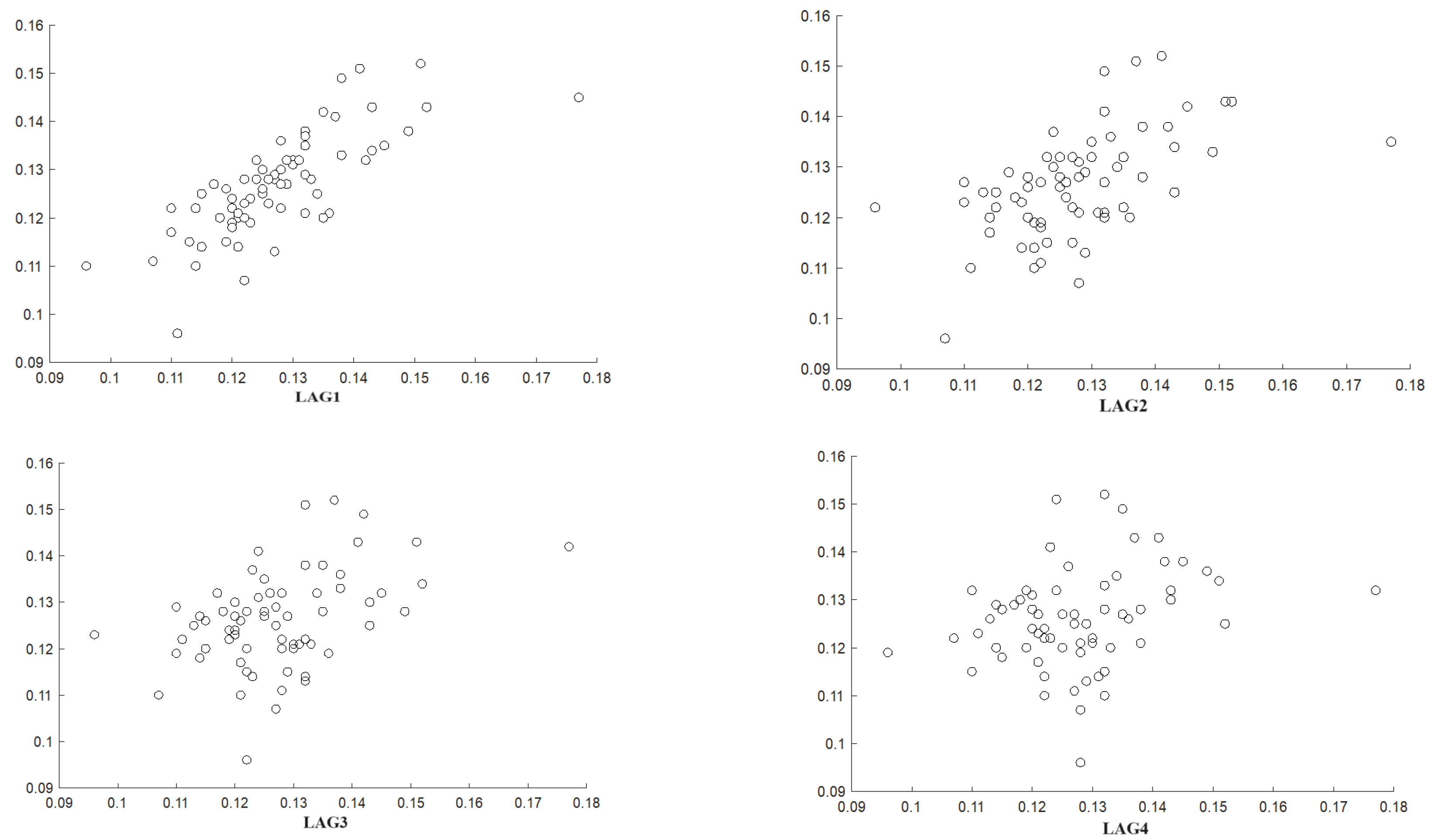

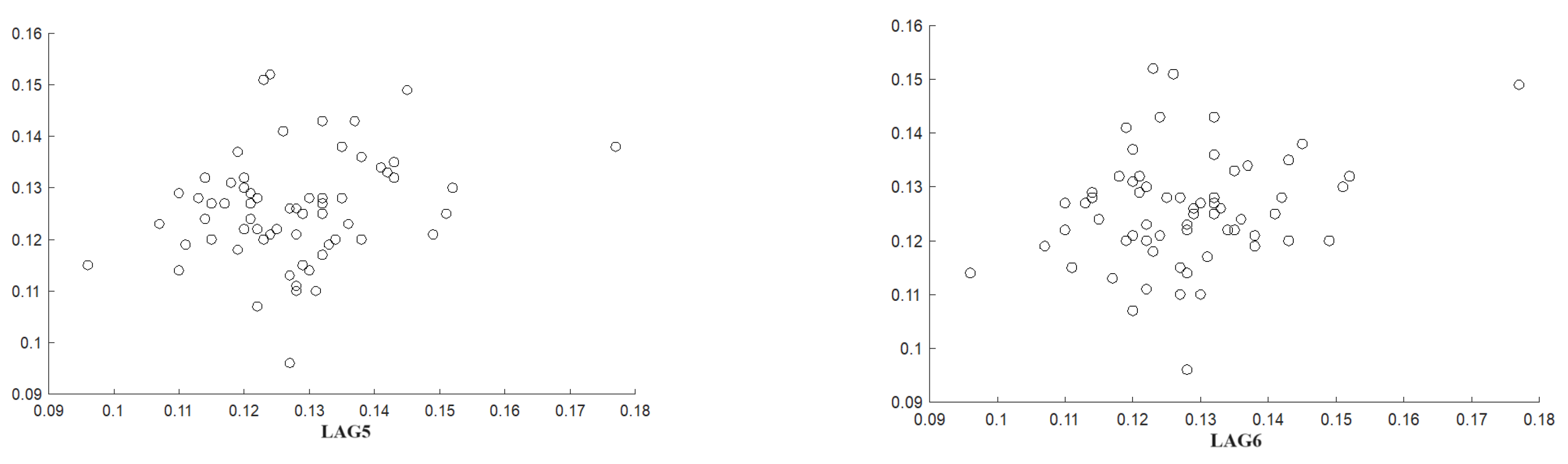

rt-k and the sample partial autocorrelation function (PACF), respectively, while

Figure 5 shows the lag plots corresponding to bivariate scatter plot of rate of profit

rt against

rt-k for

k∈{1,2,3,4,5,6}. The long decay of ACF suggests that the time series denotes a nonstationary process. On the other hand, PACF shows that only the first lag is statistically significant and this implies that the data generating the process does not include moving average terms suggesting that ARIMA(1,1,0) could be a good model for Box-Jenkins procedure [Basu and Manolakos, 2012]. However, the inclusions of other lags could take into account other statistical contributions. So, in order to avoid specification errors, in our analysis we include ARIMA(3,1,0), ARIMA(2,1,0) and ARIMA(0,1,0) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) to penalize overparametrized models.

Table 1 reports all the data of Box Jenkins investigation applied to our time-series. All the data are managed with an ad hoc home-made program written in Matlab.

Following Basu and Manolakos, who tested Marx’s hypothesis about LTFRP on U.S. economy in the time range (1945-2007), we can consider the linear time series by considering the logarithm of rate of profit data as in

Figure 1, with time trend of

χ [Basu and Manolakos, 2012]. The issue is to test whether the coefficient on the time trend, χ, is negative. This means to test or the null hypothesis, χ=0, and no evidence of falling behaviour can be taken in consideration, or the one-sided alternative, χ<0, if the null is rejected then an evidence in favour of Marx’s hypotheis must be considered. Basu and Manolakos find a negative trend of LTFRP, validating the Marx’s theory, in a range -0.04<

χ<-0.02, i.e. a percentage of falling trend between 2% and 4%. Our similar approach, but on a range of data slightly different (1945-2016), provides the following negative trend -0.045<

χ<-0.032. The slightly more negative trend may be due to the different time period of the U.S. economy taken in consideration. The period between 2007 and 2016 includes the subprime mortgage crisis (2007-2010) and the subsequent stress on the U.S. economy [Giacchè, 2011]. Units Root Tests were made by using Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and Philipps Perron (PP) tests via the correspondent Matlab routines [Matlab, 2024]. Both the tests return the test decision, p-value, test statistic, and critical value, and when applied to U.S. rate of profit time series in

Figure 1, they reject the null hypothesis implicating the process under investigation has a unit root. In addition, ADF and PP give exactly the same results,

p-Value=0.2127, test statistic=-1.1907 and critical value= -1.9450. In turn, we have combined the two methods and we have simulated a rate of profit with Eq. (4) but with the trend so

χ obtained and for the initial values as already indicated and with values for

m,

δ and

λ randomly changing with respect the values already mentioned in an interval below 10%. This simulation does not account completely for countertendencies as evidenced by the long run oscillations of the true data for the rate of profit, but the general tendency to fall is completely captured.

Figure 6.

Simulation of profit rate data as in

Figure 1, black line, with Eq. (4) including the negative trend

χ,

χ=-0.451 (blue line),

χ=-0.407 (red line)

χ=-0.365 (green line)

χ=-0.32 (cyan line) that the typical time trend evidenced by the econometric analysis.

Figure 6.

Simulation of profit rate data as in

Figure 1, black line, with Eq. (4) including the negative trend

χ,

χ=-0.451 (blue line),

χ=-0.407 (red line)

χ=-0.365 (green line)

χ=-0.32 (cyan line) that the typical time trend evidenced by the econometric analysis.

5. Conclusive Remarks

The historically prevalent mode of production in each era can be considered as complex adaptive systems, whose main characteristics are self-organization, interdependence, space of possibilities, co-evolution and self-replication. The overall effectiveness of these characteristics are summarized by their ability to self-replication. Marx’s theory asserts that the efforts of increasing the rate of profit can lead to its progressive fall, which is an inherent contradiction of the capitalist production mode. In this paper we have exploited and econometric model to demonstrate the tendencial falling rate in long run time for the U.S. economy in the years range 1945-2016. Once the falling tendency has been evidenced, we adopted a model to simulate the dynamics of such mechanism of falling tendency by revealing the relations between the parameters of production function, wage model, the state of the technology and, in turn, the relations between composition of capital and surplus-value rate under the basic assumptions of Marx’s theory. The dynamic modelization of tendential falling of profit rate follows, even if at a qualitative level, a self-replicating mechanism. Self-replication is a basic property of dissipative structure and complex systems. Dissipation and complexity are key concepts to describe biological and natural processes that we believe can be very effective in describing the dynamics of capital developments. This paper intended to combine econometric analysis with dynamical modelisation in order to create a framework for detailing the role and incidence of any variable, the state of technology, wage amount, composition of capital, in the amount of the profit rate and their effect in the trend fall, within the Marxian theory that is the only theory capable to adequately explaining this tendency law of capital.

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Renato Fiaschi (1930-2024), an example of coherent and rigorous intellectual of the People.

References

- Awrey, Dan. 2016. The Mechanisms of Derivative Efficiency, New York University Law review, 91, 1104-1184.

- Bagus, Philipp. 2011. “Morgenstern’s Forgotten Contribution: A Stab to the Heart of Modern Economics”. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 70(2), 540 562. [CrossRef]

- Barrat, Alain, Barthélemy, Marc, Vespignani, Alessandro, 2012. Dynamical Processes on Complex Networks. Cambridge University Press, UK.

- von Bertalanffy, Ludwig. 1972. “The history and status of general systems theory”, Acad. Manag. J. 15,407-426.

- Basu, Deepankar, and Manolakos, Panayiotis T., 2012 “Is There a Tendency for the Rate of Profit to Fall? Econometric evidence for the U.S. Economy, 1948-2007”, Review of Radical Political Economics, 45 (1), 76-95. [CrossRef]

- Basu, Deepankar, and Vesudevan, Ramaa. 2013. “Technology, distribution, and the rate of profit in the US economy: understanding the current crisis”, Cambridge Journal of Economics,m 37(1), 57-89. [CrossRef]

- Boyce, Robert. 1989. World Depression, World War: Some Economic World War, in Paths to War, Boyce R. and Robertson E.M. editors, Palgrave, London.

- Box, George E.P., and Jenkins, Gwilym M. 1979. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control. Holden-Day, San Francisco USA.

- Brancaccio, Emiliano, Giammetti, Raffaele, Lopreite, Milena, Puliga, Michelangelo. 2018. “Centralization of capital and financial crisis: A global network analysis of corporate control”, Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 45, 94-104. [CrossRef]

- Carchedi, Gugliemo. 1995, Non-equilibrium Market Prices, in Marx and Non Equilibrium Economics, Freeman Alan and Carchedi, Gugliemo Editors, Edward Elgar Publisher. [CrossRef]

- Carchedi, Guglielmo. 2015. http://gesd.free.fr/carchedi815.pdf.

- Carchedi, Guglielmo, Roberts, Michael, 2018. World in Crisis: A Global Analysis of Marx’s Law of Profitability: Marxist Perspectives on Crash &Crisis, Haymarket Books, ISBN: 978-1608461813.

- Chen, Jing, 2016. The Unity of Science and Economics. A New Foundation of Economic Theory. Springer, New York, USA.

- Dobb, Maurice Herbert. 1939. Political economy and capitalism. New York: International Publishers.

- Duménil, Gerard, and Lévy, Dominique. 1993. The economics of the profit rate: Competition, crises and historical tendencies in capitalism, E. Elgar, Aldershot, UK. [CrossRef]

- Duménil, Gerard, and Lévy, Dominique. 2002a. “The field of capital mobility and the gravitation of profit rates (USA 1948-2000)”. Review of Radical Political Economics, 34(49, 417-436. [CrossRef]

- Duménil, Gerard, and Lévy, Dominique. 2002b. “The profit rate: Where and how much did it fall? Did it recover? USA 1948-2000”. Review of Radical Political Economics, 34(49, 437-461.

- Duménil, Gerard, and Lévy, Dominique, 2003. “Technology and distribution: Historical trajectories à la Marx”, Journal of Economic Behaviour and Organization, 52, 201-233.

- Duménil, Gerard, and Lévy, Dominique, 2016. “The historical trends of technology and distribution in the U.S. Economy. Data and Figures”, Centre pour la Reserche Economique et ses Applications, CEPREMAP Document, France, https://www.cepremap.fr/membres/dlevy/dle2016e.pdf.

- Foley, Duncan. 1986. Understanding Capital: Marx’s economic theory. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, USA.

- Foley, Duncan and Michl, Thomas. 1999. Growth and Distribution. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, USA.

- Foley, Duncan, Michl, Thomas, Tavani, Daniele. 2019. Growth and Distribution. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, USA.

- Georgescu-Roegen, N. 1971. The Entropy Law and the Economic Process; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA.

- Giacchè, Valdimiro. 2011. “Marx, the Falling Rate of Profit, Financialization, and the Current Crisis”, International Journal of Politica Economy, 40(3), 18-32. [CrossRef]

- Gilman, Joseph Moses. 1957. The falling rate of profit: Marx’s law and its significance to twentieth-century capitalism. London, D. Dobson editor.

- Hamilton, James D. 1988. “A Neoclassical Model of Unemployment and the Business Cycle”, Journal of Political Economy, 96(3), 593-617. [CrossRef]

- Hayek, Friederich August. 2014. The Collected Works of F.A. Hayek, Volume 15: The Market and other Orders, Edited by B. Caldwell, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA.

- Kuenne, Robert E., 1992. General Equilibrium Economics. Space, Time and Money. MacMillan Press LTD, London, UK.

- Lewis, Paul Andrew. 2016. Systems, Structural Properties and Levels of Organization: The Influence of Ludwig von Bertalanffy on the Work of F.A. Hayek, Research in the History of Economic Thought and Methodology, Volume 34, 125-159. [CrossRef]

- Mandel, Ernest. 1980. Long waves of capitalist development. London, Verso.

- Markovic, Dimitrije, Gros, Claudius. 2014. “Power laws and self-organized criticality in theory and nature”, Physics Reports, 536, 41-74. [CrossRef]

- Marx, Karl. 1993. The Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume III, London, Penguin Classics, first published in 1894.

- Matlab, 2024. https://it.mathworks.com/help/econ/adftest.html.

- McKenzie, Lionel W., 2008, “General Equilibrium”, chapter 1 in The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, pp.1-27.

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W., III. 1972. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA.

- Michl, Thomas. 1988. “The two-stage decline in U.S. nonfinancial corporate profitability, 1948-1986”. Review of radical Political Economics, 20(4), 1-22.

- Morgenstern, Oscar. 1950. On the Accuracy of Economic Observations. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press.

- Mügge, Daniela and Linsi, Lukas. 2021. “The national accounting paradox: how statistical norms corrode international economic data”. European Journal of International Relations, 27(2), 403-427. [CrossRef]

- Okishio, Nobuo. 1961. “Technical Change and the Rate of Profit”, Kobe University Economic Review, 7, 85-99.

- Park, Seong-Jin, and Yang, Jung-Min, 2023, “Feedback Control Analysis for Marx’s Law of the Tendential Fall in the rate of Profit”, International Journal of Control, Automation and Systems, 21(5), 1407-1419. [CrossRef]

- Reuten, Geert.1991. “Accumulation of capital and the foundation of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall”. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 15(1), 79-93.

- Roemer, John. 1981. Analytical foundations of Marxian economic theory. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Shaikh, Anwar. 1992. “The falling rate of profit as the cause of long waves: Theory and empirical evidence”. Pp.174-195, in New findings in long waves research, ed. A. Kleinknecht, E. Mandel and I. Wallerstein, Macmillian, London. [CrossRef]

- Sornette, Didier, Cauwels, Peter. 2014. “Financial Bubbles: Mechanisms and Diagnostics”, Swiss Finance Institute Research, Paper No.14-28. [CrossRef]

- Sraffa, Piero, 1960. Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities. Prelude to a critique of economic theory. Cambridge University Press, UK. [CrossRef]

- Sweezy, Paul Marlor. 1942. The theory of capitalist development. New York, monthly Review Press.

- Turner, John Robert, Baker, Rose May. 2019. “Complexity Theory: An Overview with Potential Applications for the Social Sciences” Systems, 7(1), 4. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, Edward. 2001. “The recent rise of profits in the United States”. Review of radical Political Economics, 33(3), 314-324.

- Wolff, Edward. 2003. “What is behind the rise in profitability in the U.S. in the 1980s and 1990s?”. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 27(4), 479-499.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).