Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

With the acceleration of urbanization around the world, city dwellers face increasing levels of work stress and mental health issues, which negatively impact their happiness. The purpose of this study was to explore the impact of natural environment on residents' mental health and well-being in urban forest parks, and to analyze the relationship between natural environment perception, psychological recovery, restorative environment perception and subjective well-being. Through a questionnaire survey conducted in a botanical garden in Hunan Province, 504 valid samples were collected. Through structural equation model (SEM) analysis, the results show that: (1) natural environment perception has significant positive effects on psychological recovery and restorative environment perception. (2) Psychological recovery as an intermediary variable significantly improved residents' subjective well-being. In addition, the characteristics of an individual's social background, such as gender, education level, occupation, and frequency of visits, are closely related to the perception and well-being of the natural environment. Among them, the increase of the frequency of visit has a significant positive effect on the improvement of individual's natural environment perception, restorative environment perception, subjective well-being and psychological recovery. The results show that: (1) Urban planners should improve the accessibility of urban forest parks and integrate restorative elements into the design. (2) Encourage residents to visit frequently to improve mental health and well-being. The results of this study provide empirical support for the value of urban forest parks in promoting public mental health and well-being, and provide scientific basis for urban planning and green space management.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Psychological Health Issues and Happiness

1.2. Natural Environment and Mental Health

1.3. Urban Forest Parks and Psychological Happiness

1.4. Natural Environment and Happiness

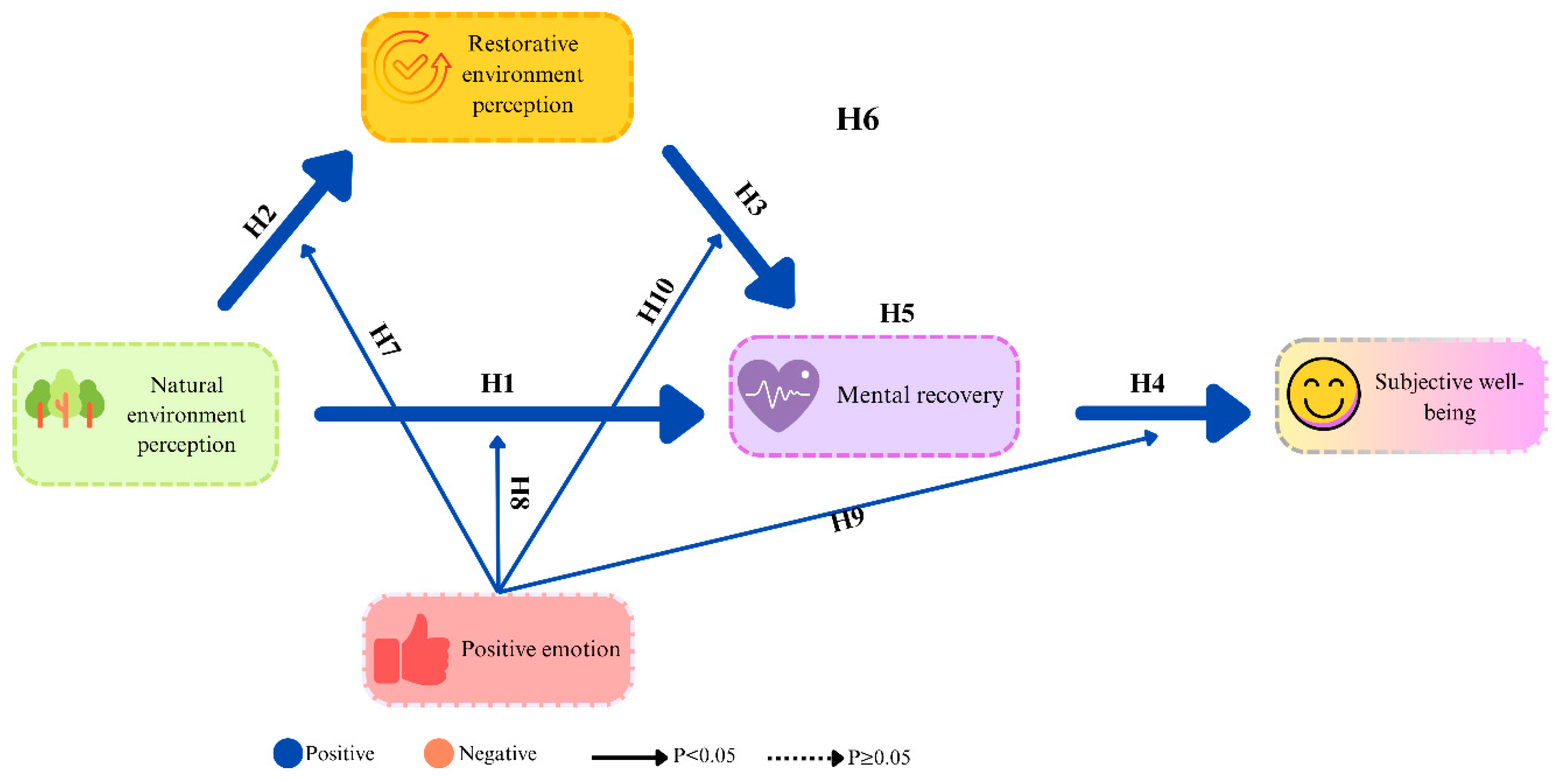

2. Development and Justification of Hypotheses

2.1. Natural Environment Perception and Psychological Recovery

2.2. Natural Environment Perception and Restorative Environment Perception

2.3. Restorative Environmental Perception and Psychological Recovery

2.4. Mental Recovery and Subjective Well-Being

2.5. Restorative Environment Perception and Mental Recovery as Mediators in the Relationship Between Natural Environment Perception and Subjective Well-Being

2.6. The Moderating Role of Positive Emotion

3. Research Area and Methods

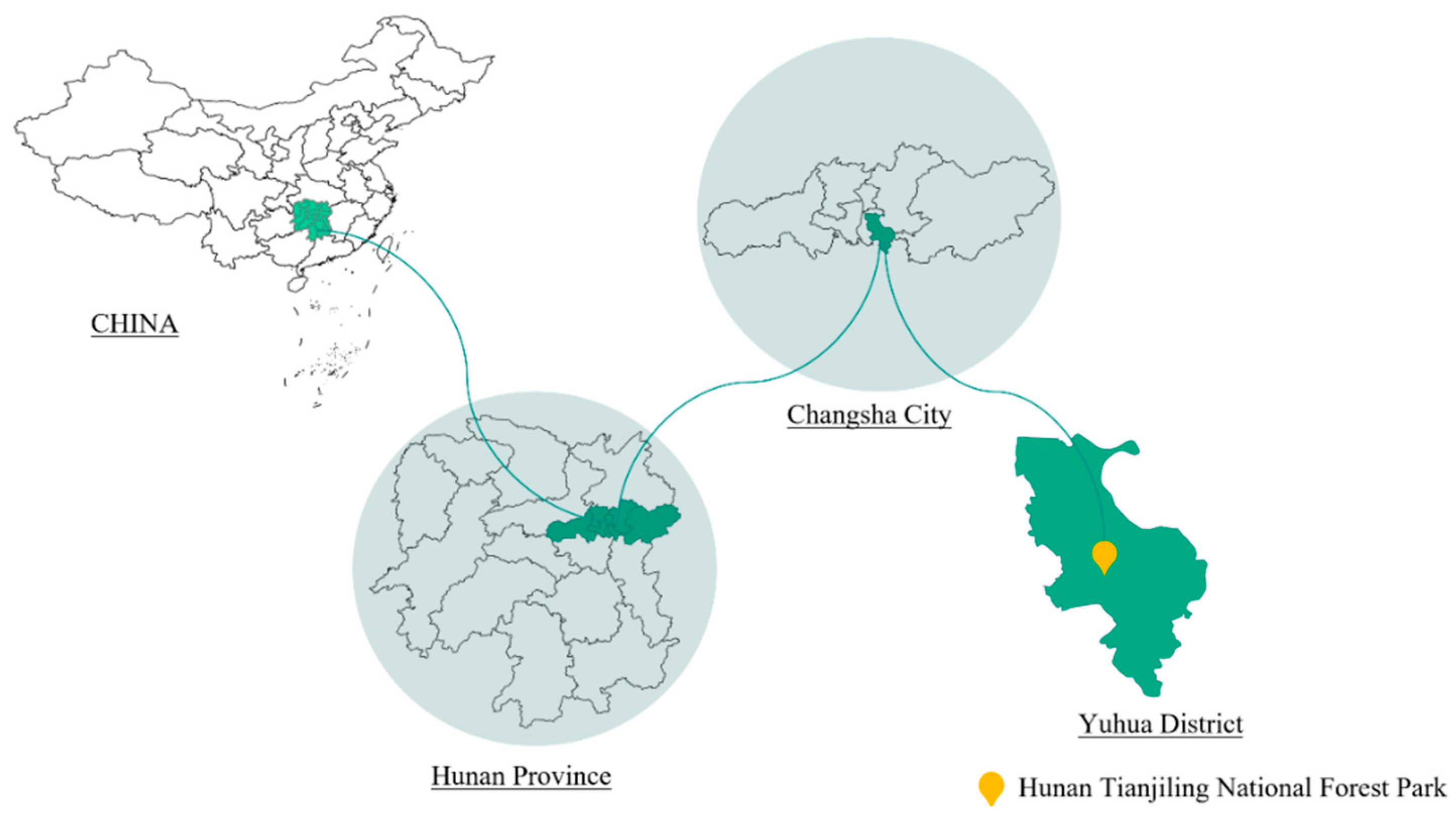

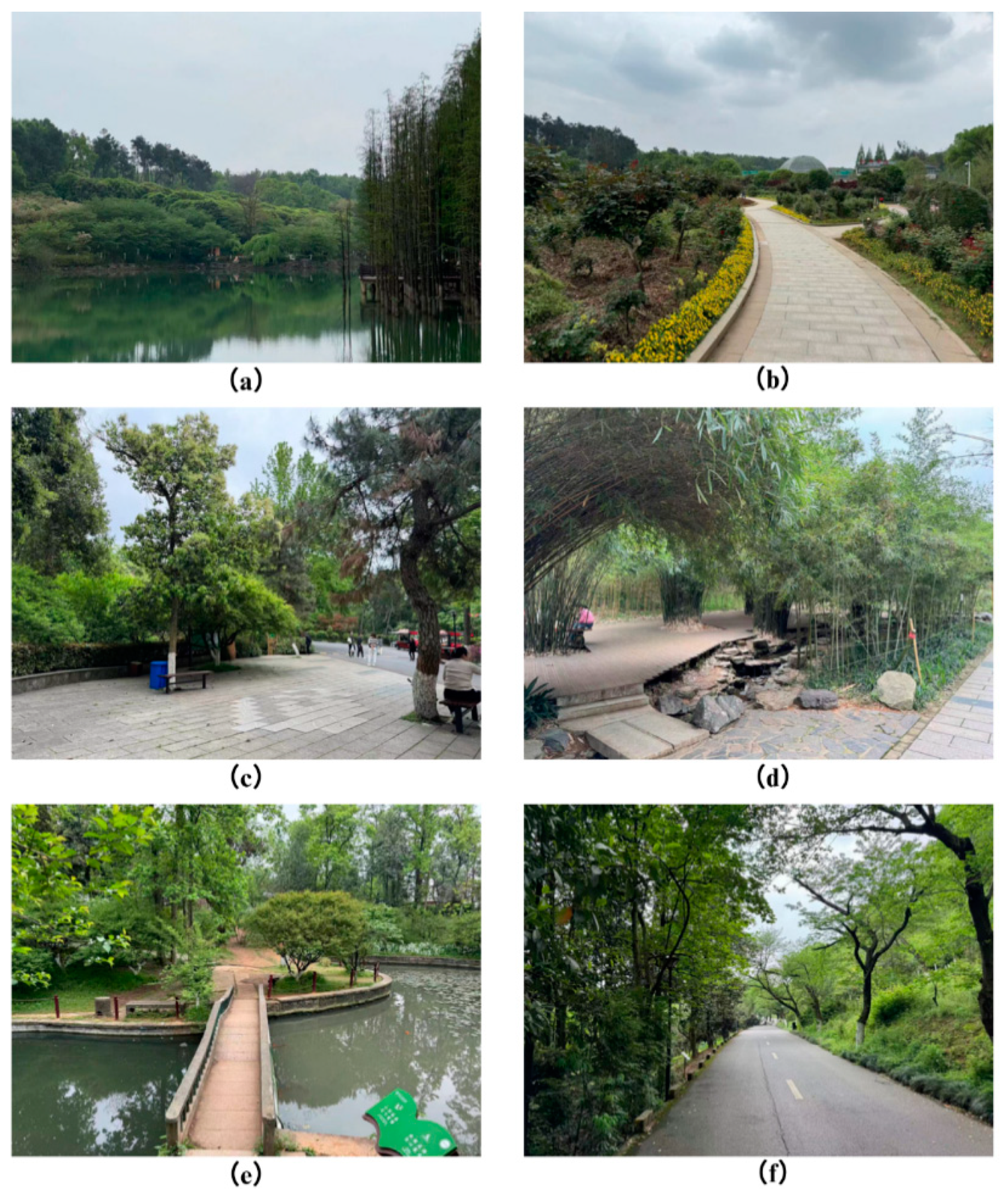

3.1. Research Area

3.2. Questionnaire Design

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias Test

4.2. Reliability and Validity Testing of the Scales

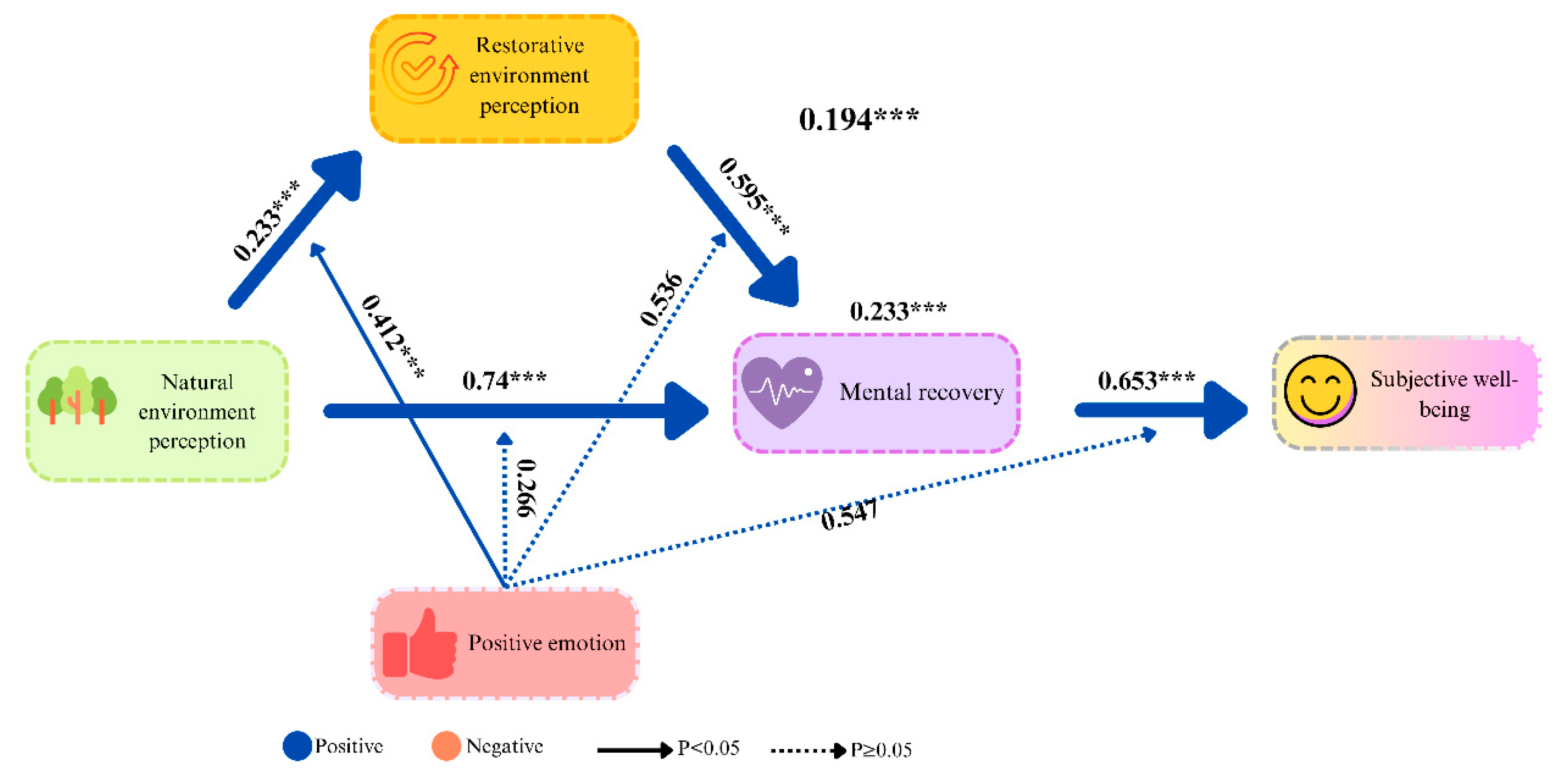

4.3. Structural Equation Model Testing

4.4. Mediation Effect Analysis

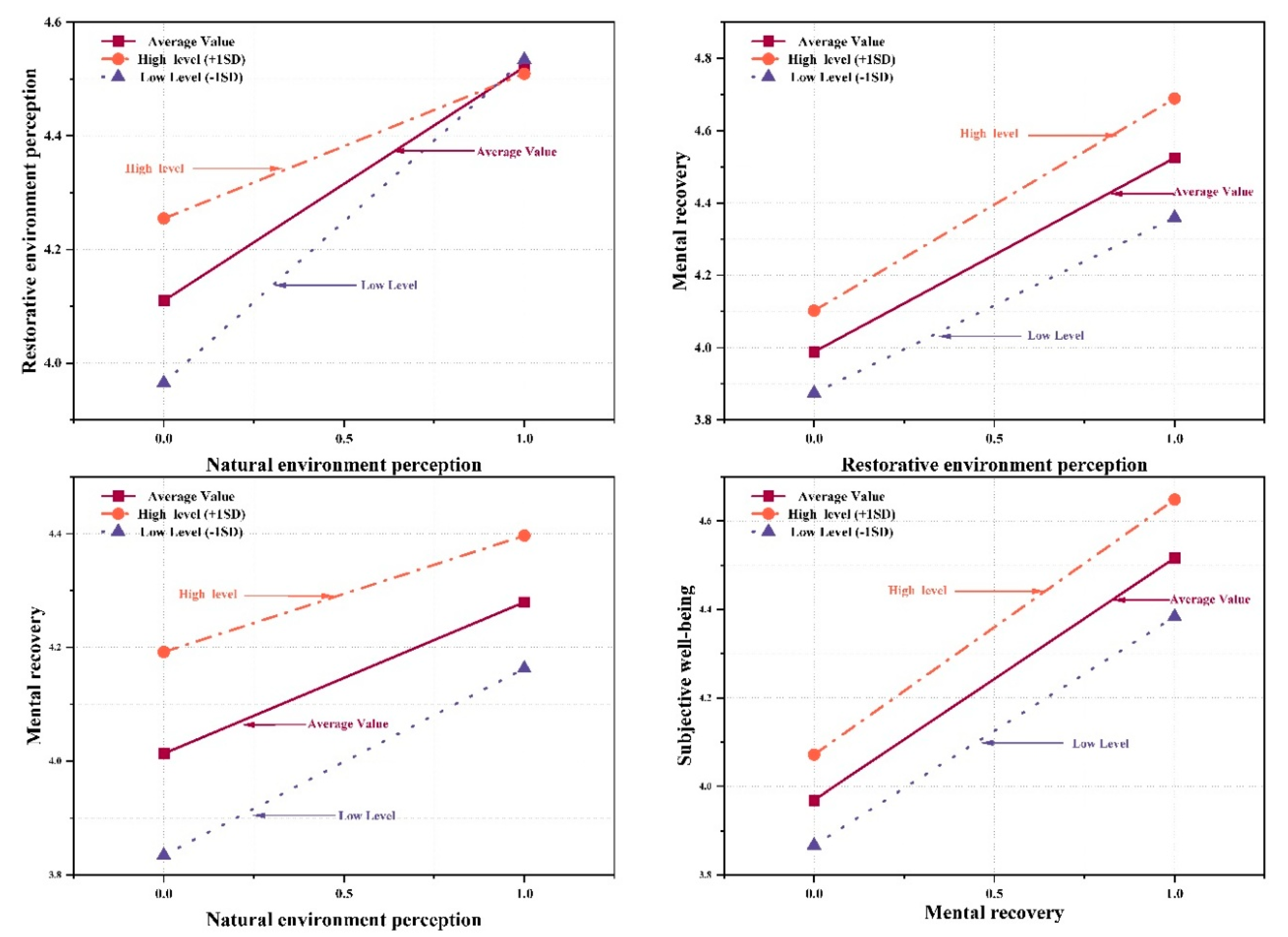

4.5. Moderation Effect Analysis

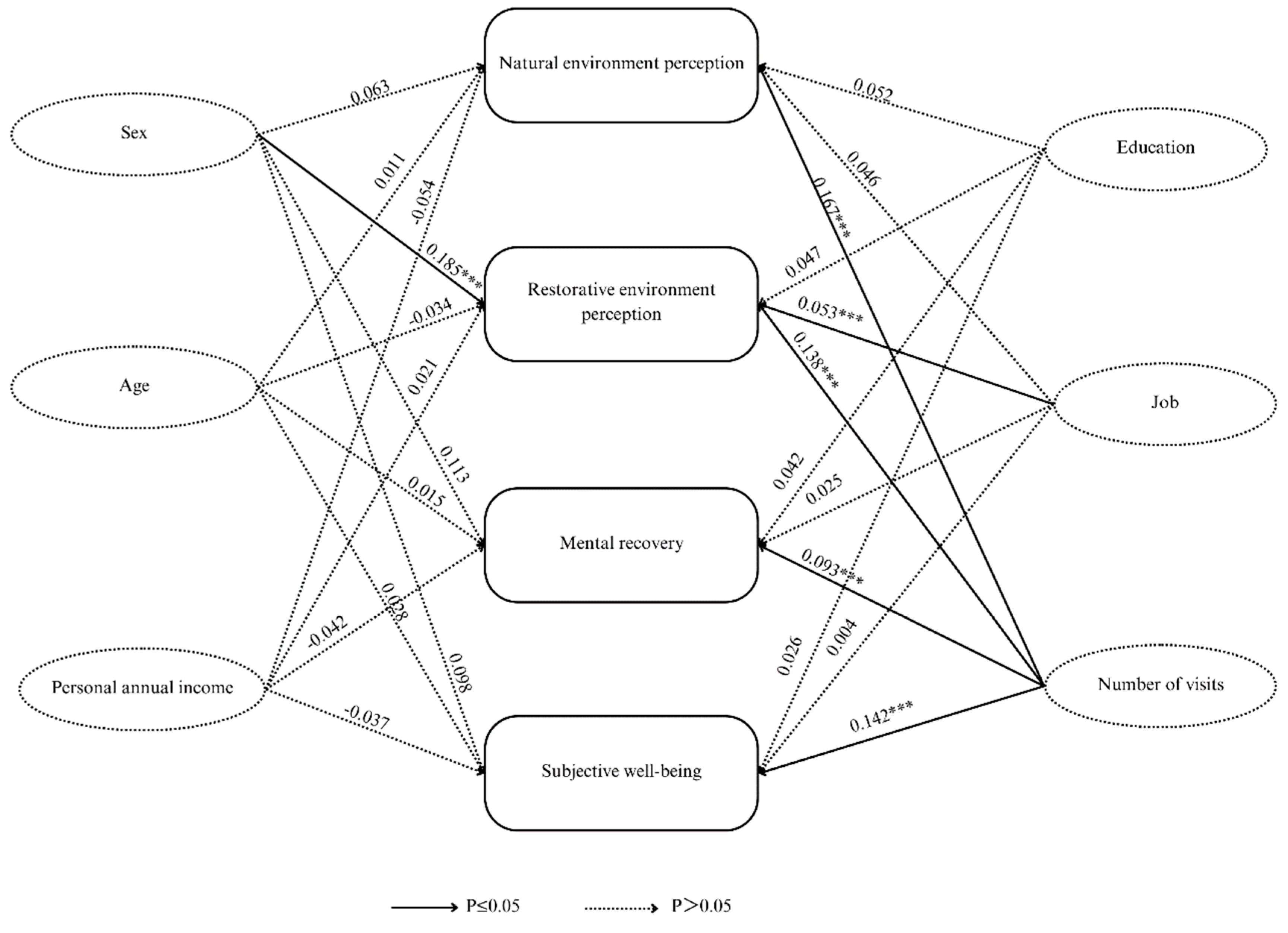

4.6. Linear Relationships Between Demographic Characteristics and Environmental Perception and Well-Being

5. Discussion

5.1. Exposure to Natural Environments Enhances Well-Being

5.2. Natural Environment Perception Significantly Influences Mental Recovery and Restorative Environment Perception

5.3. Mental Recovery and Subjective Well-Being

5.4. The Mediating Role of Mental Recovery and Restorative Environment Perception Between Natural Environment and Subjective Well-Being

5.5. The Moderating Effect of Positive Emotion Is Not Pronounced

5.6. The Positive Influence of Frequency of Visits on Subjective Well-Being

6. Conclusions, Recommendations, and Study Limitations

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Recommendations

6.3. Study Limitations and Future

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Acknowledgments

Competing interests

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Patients consent to publication

References

- 2024 World Happiness Report Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240074323 (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Helliwell, J.F.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J.D.; Neve, J.-E.D.; Aknin, L.B.; Wang, S. World Happiness Report 2024 Available online: https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2024/ (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Buckley, R. Nature Tourism and Mental Health: Parks, Happiness, and Causation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1409–1424. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. Happiness and Mental Health of Older Adults: Multiple Mediation Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Touburg, G.; Veenhoven, R. Mental Health Care and Average Happiness: Strong Effect in Developed Nations. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 394–404. [CrossRef]

- Buckland, H.T.; Schepp, K.G.; Crusoe, K. Defining Happiness for Young Adults With Schizophrenia: A Building Block for Recovery. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2013, 27, 235–240. [CrossRef]

- Dr. Gopal Chandra Mahakud; Ritika Yadav Effects of Happiness on Mental Health. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2015, 2. [CrossRef]

- Almadani, N.A.; Alwesmi, M.B. The Relationship between Happiness and Mental Health among Saudi Women. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 526. [CrossRef]

- Alvarsson, J.J.; Wiens, S.; Nilsson, M.E. Stress Recovery during Exposure to Nature Sound and Environmental Noise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2010, 7, 1036–1046. [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Böök, A.; Garvill, J.; Olsson, T.; Gärling, T. Environmental Influences on Psychological Restoration. Scand. J. Psychol. 1996, 37, 378–393. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Zhang, S. Effects of Different Natural Soundscapes on Human Psychophysiology in National Forest Park. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17462. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.B.; Stevenson, K.T.; Larson, L.R.; Peterson, M.N.; Seekamp, E. Outdoor Activity Participation Improves Adolescents’ Mental Health and Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 2506. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Tan, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Yuan, J.; Ding, Y. Psychological Recovery Effects of 3D Virtual Tourism with Real Scenes -- a Comparative Study. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2023, 25, 71–103. [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Azcárraga, C.; Diaz, D.; Zambrano, L. Characteristics of Urban Parks and Their Relation to User Well-Being. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 27–35. [CrossRef]

- Geng, W.; Wan, Q.; Wang, H.; Dai, Y.; Weng, L.; Zhao, M.; Lei, Y.; Duan, Y. Leisure Involvement, Leisure Benefits, and Subjective Well-Being of Bicycle Riders in an Urban Forest Park: The Moderation of Age. Forests 2023, 14, 1676. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Riveros, R.; Altamirano, A.; De La Barrera, F.; Rozas-Vásquez, D.; Vieli, L.; Meli, P. Linking Public Urban Green Spaces and Human Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 61, 127105. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Son, Y.-H.; Kim, S.; Lee, D.K. Healing Experiences of Middle-Aged Women through an Urban Forest Therapy Program. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 38, 383–391. [CrossRef]

- MacKerron, G.; Mourato, S. Happiness Is Greater in Natural Environments. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 992–1000. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Cheng, G.J.Y.; Nghiem, T.P.L.; Song, X.P.; Oh, R.R.Y.; Richards, D.R.; Carrasco, L.R. Social Media, Nature, and Life Satisfaction: Global Evidence of the Biophilia Hypothesis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4125. [CrossRef]

- Gaekwad, J.S.; Sal Moslehian, A.; Roös, P.B.; Walker, A. A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Evidence for the Biophilia Hypothesis and Implications for Biophilic Design. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.; Pretty, J. What Is the Best Dose of Nature and Green Exercise for Improving Mental Health? A Multi-Study Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3947–3955. [CrossRef]

- Basner, M.; Babisch, W.; Davis, A.; Brink, M.; Clark, C.; Janssen, S.; Stansfeld, S. Auditory and Non-Auditory Effects of Noise on Health. The Lancet 2014, 383, 1325–1332. [CrossRef]

- Passchier-Vermeer, W.; Passchier, W.F. Noise Exposure and Public Health. Environ. Health Perspect. 2000, 108, 123–131. [CrossRef]

- Franchini, M.; Mannucci, P.M. Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease. Thromb. Res. 2012, 129, 230–234. [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H. Environment and Happiness: Valuation of Air Pollution Using Life Satisfaction Data. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 58, 801–813. [CrossRef]

- Stieger, S.; Aichinger, I.; Swami, V. The Impact of Nature Exposure on Body Image and Happiness: An Experience Sampling Study. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2022, 32, 870–884. [CrossRef]

- Macaulay, R.; Lee, K.; Johnson, K.; Williams, K. Mindful Engagement, Psychological Restoration, and Connection with Nature in Constrained Nature Experiences. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 217, 104263. [CrossRef]

- Payne, E.A.; Loi, N.M.; Thorsteinsson, E.B. The Restorative Effect of the Natural Environment on University Students’ Psychological Health. J. Environ. Public Health 2020, 2020, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [CrossRef]

- Pan, H. Effect of the Ecological Environment on the Residents’ Happiness: The Mechanism and an Evidence from Zhejiang Province of China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 2716–2734. [CrossRef]

- The Routledge Companion to Landscape Studies; Howard, P., Thompson, I.H., Waterton, E., Atha, M., Eds.; Second edition.; Routledge Taylor and Francis Group: London; New York, 2019; ISBN 978-1-315-19506-3.

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. A Psychological Perspective.

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and Affective Response to Natural Environment. In Behavior and the Natural Environment; Altman, I., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1983; pp. 85–125 ISBN 978-1-4613-3541-2.

- Hartig, T.; Mang, M.; Evans, G.W. Restorative Effects of Natural Environment Experiences. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 3–26. [CrossRef]

- Polajnar Horvat, K.; Ribeiro, D. Urban Public Spaces as Restorative Environments: The Case of Ljubljana. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 2159. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The Connectedness to Nature Scale: A Measure of Individuals’ Feeling in Community with Nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [CrossRef]

- Sandifer, P.A.; Sutton-Grier, A.E.; Ward, B.P. Exploring Connections among Nature, Biodiversity, Ecosystem Services, and Human Health and Well-Being: Opportunities to Enhance Health and Biodiversity Conservation. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 12, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Giusti, M.; Samuelsson, K. The Regenerative Compatibility: A Synergy between Healthy Ecosystems, Environmental Attitudes, and Restorative Experiences. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0227311. [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The Measurement of Place Attachment: Validity and Generalizability of a Psychometric Approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Zhang, L.; Hou, R.; Lau, S.S.Y.; Lau, S.S.Y. Research on the Physiological and Psychological Impacts of Extraordinary Nature on Emotions and Restorative Effects for Young Adults. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 97, 102345. [CrossRef]

- Akpınar, A. How Perceived Sensory Dimensions of Urban Green Spaces Are Associated with Teenagers’ Perceived Restoration, Stress, and Mental Health? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104185. [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.M.; Lercher, P.; Vincens, N.; Persson Waye, K.; Klatte, M.; Leist, L.; Lachmann, T.; Schreckenberg, D.; Belke, C.; Ristovska, G.; et al. Protective Effect of Restorative Possibilities on Cognitive Function and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents: A Scoping Review Including the Role of Physical Activity. Environ. Res. 2023, 233, 116452. [CrossRef]

- Echezarraga, A.; Las Hayas, C.; López De Arroyabe, E.; Jones, S.H. Resilience and Recovery in the Context of Psychological Disorders. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2024, 64, 465–488. [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Arslan, G. Exploring the Associations between Resilience, Dispositional Hope, Preventive Behaviours, Subjective Well-Being, and Psychological Health among Adults during Early Stage of COVID-19. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 5712–5722. [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The Role of Positive Emotions in Positive Psychology: The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. Meditation, Restoration, and the Management of Mental Fatigue. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 480–506. [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Zhang, X.; Gong, Q. The Effect of Exposure to the Natural Environment on Stress Reduction: A Meta-Analysis. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 57, 126932. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Meng, H.; Zhang, T. How Does the Experience of Forest Recreation Spaces in Different Seasons Affect the Physical and Mental Recovery of Users? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 2357. [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S. The Case for Positive Emotions in the Stress Process. Anxiety Stress Coping 2008, 21, 3–14. [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, C.E.; Larkin, K.T. A Critical Review of the “Undoing Hypothesis”: Do Positive Emotions Undo the Effects of Stress? Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2018, 43, 259–273. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; McEwan, K.; Maratos, F.; Sheffield, D. Joy and Calm: How an Evolutionary Functional Model of Affect Regulation Informs Positive Emotions in Nature. Evol. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 2, 308–320. [CrossRef]

- Russell J A. A Circumplex Model of Affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, Í6I, I78.

- Norman, G.J.; Necka, E.; Berntson, G.G. 4 - The Psychophysiology of Emotions. In Emotion Measurement; Meiselman, H.L., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing, 2016; pp. 83–98 ISBN 978-0-08-100508-8.

- Jones, N.A.; Mize, K.D. Introduction to the Special Issue: Psychophysiology and Psychobiology in Emotion Development. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2016, 142, 239–244. [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Anderson, C.B.; Berman, M.G.; Cochran, B.; De Vries, S.; Flanders, J.; Folke, C.; Frumkin, H.; Gross, J.J.; Hartig, T.; et al. Nature and Mental Health: An Ecosystem Service Perspective. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax0903. [CrossRef]

- Kuykendall, L.; Tay, L.; Ng, V. Leisure Engagement and Subjective Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 364–403. [CrossRef]

- Wiese, C.W.; Kuykendall, L.; Tay, L. Get Active? A Meta-Analysis of Leisure-Time Physical Activity and Subjective Well-Being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2018, 13, 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Kaltenborn, B.P.; Bjerke, T. Associations between Landscape Preferences and Place Attachment: A Study in Røros, Southern Norway. Landsc. Res. 2002, 27, 381–396. [CrossRef]

- Huang C.C.; Hunag F.M.; Chou X.J. Research on the Relationship between Environmental Preference and Environmental Resilience Evaluation: A Case Study of Mountain View. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2008, 1–25.

- Yang, H.; Zhang, S. Impact of Rural Soundscape on Environmental Restoration: An Empirical Study Based on the Taohuayuan Scenic Area in Changde, China. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0300328. [CrossRef]

- Hartig T. Further Developmentof a Measureof PerceivedEnvironmental Restorativeness. Int. J. Energy Res. 1997, 1–23.

- Diener, E. Subjective Well-Being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Anna, L.; Tellegen, A. Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: The PANAS Scales.

- Wen Z L Comparison and Application of Moderating Effect and Mediating Effect. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2005, 37, 268–274.

- Mulaik, S.A.; James, L.R.; Van Alstine, J.; Bennett, N.; Lind, S.; Stilwell, C.D. Evaluation of Goodness-of-Fit Indices for Structural Equation Models. Psychol. Bull. 1989, 105, 430–445. [CrossRef]

- Blunch, N.J. Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling Using IBM SPSS Statistics and Amos. 2012, 1–312.

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [CrossRef]

- Wicks, C.; Barton, J.; Orbell, S.; Andrews, L. Psychological Benefits of Outdoor Physical Activity in Natural versus Urban Environments: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Experimental Studies. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2022, 14, 1037–1061. [CrossRef]

- Psychological and Physical Connections with Nature Improve Both Human Well-Being and Nature Conservation: A Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 277, 109842. [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.; Pretty, J. What Is the Best Dose of Nature and Green Exercise for Improving Mental Health? A Multi-Study Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3947–3955. [CrossRef]

- Schebella, M.F.; Weber, D.; Schultz, L.; Weinstein, P. The Nature of Reality: Human Stress Recovery during Exposure to Biodiverse, Multisensory Virtual Environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 17, 56. [CrossRef]

- Kjellgren, A.; Buhrkall, H. A Comparison of the Restorative Effect of a Natural Environment with That of a Simulated Natural Environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 464–472. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Z. Effects of Sound Source Landscape in Urban Forest Park on Alleviating Mental Stress of Visitors: Evidence from Huolu Mountain Forest Park, Guangzhou. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15125. [CrossRef]

- Yeon, P.-S.; Kim, I.-O.; Kang, S.-N.; Lee, N.-E.; Kim, G.-Y.; Min, G.-M.; Chung, C.-Y.; Lee, J.-S.; Kim, J.-G.; Shin, W.-S. Effects of Urban Forest Therapy Program on Depression Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 20, 507. [CrossRef]

- Tsunetsugu, Y.; Lee, J.; Park, B.-J.; Tyrväinen, L.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and Psychological Effects of Viewing Urban Forest Landscapes Assessed by Multiple Measurements. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 113, 90–93. [CrossRef]

- Fava, G.A.; Tomba, E. Increasing Psychological Well-Being and Resilience by Psychotherapeutic Methods. J. Pers. 2009, 77, 1903–1934. [CrossRef]

- Fava, G.A.; Offidani, E. The Mechanisms of Tolerance in Antidepressant Action. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 35, 1593–1602. [CrossRef]

- Nukarinen, T.; Rantala, J.; Korpela, K.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Istance, H.O.; Surakka, V.; Raisamo, R. Measures and Modalities in Restorative Virtual Natural Environments: An Integrative Narrative Review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 126, 107008. [CrossRef]

- Frost, S.; Kannis-Dymand, L.; Schaffer, V.; Millear, P.; Allen, A.; Stallman, H.; Mason, J.; Wood, A.; Atkinson-Nolte, J. Virtual Immersion in Nature and Psychological Well-Being: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 80, 101765. [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Joiner, T. Positive Emotions Trigger Upward Spirals Toward Emotional Well-Being. Psychol. Sci. 2002, 13, 172–175. [CrossRef]

- Dreer, B. Teachers’ Well-Being and Job Satisfaction: The Important Role of Positive Emotions in the Workplace. Educ. Stud. 2024, 50, 61–77. [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, T.; Schotanus-Dijkstra, M.; Graafsma, T.; Bohlmeijer, E.; de Jong, J. Positive Emotions as a Potential Mediator of a Multi-Component Positive Psychology Intervention Aimed at Increasing Mental Well-Being and Resilience. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 2021, 6, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, M.J.; Eusébio, C. Factors Influencing the Impact of Tourism on Happiness. Anatolia 2019, 30, 475–496. [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-K.; Lee, S.-W.; Jo, H.-K.; Yoo, M. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4189. [CrossRef]

- Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects - Philip M. Podsakoff, Dennis W. Organ, 1986 Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/014920638601200408 (accessed on 27 September 2024).

| Variables | Variable quantity | Potential items |

| Natural environment perception | NAP1 | The air here is relatively fresh. |

| NAP2 | This place has a rich fragrance from the plants. | |

| NAP3 | The climate here is more comfortable than in the city. | |

| NAP4 | The lighting here is suitable. | |

| NAP5 | The wind here is gentle and comfortable. | |

| NAP6 | The air's temperature and humidity here are appropriate. | |

| NAP7 | There are many natural sounds here (such as birdsong, frog croaks, rain sounds, etc.). | |

| NAP8 | There is a rich variety of biological scenery here (animals, plants, etc.). | |

| NAP9 | The environment here is peaceful. | |

| NAP10 | The space here is open, with long visual distances. | |

| NAP11 | This place offers a nature-oriented experience. | |

| NAP12 | The forest vegetation here is varied and layered. | |

| NAP13 | The natural sounds here are rich in variation and wonderful. | |

| NAP14 | Water bodies are common and abundant here. | |

| NAP15 | The forest vegetation here is diverse and rich in variation (species, colors, etc.). | |

| NAP16 | The terrain and landforms here are diverse and varied. | |

| NAP17 | The roads are winding and the natural environment through which they pass is also rich in variation. | |

| Restorative environment perception | REP1 | Here, I feel completely free. |

| REP2 | Everything here is very friendly. | |

| REP3 | I feel like I'm blending in with nature. | |

| REP4 | Everything here is in harmony with the overall environment. | |

| REP5 | I can do what I crave and enjoy here. | |

| REP6 | Here, I can temporarily forget my responsibilities and stress. | |

| REP7 | Here, I can escape the monotony of daily life and get some rest. | |

| REP8 | Here, I feel like the environment is different from my usual daily surroundings. | |

| REP9 | The activities I do here are different from what I do at home. | |

| REP10 | The environment here is vastly different from my usual surroundings. | |

| REP11 | This place is enchanting and unforgettable. | |

| REP12 | There are many interesting things and discoveries here. | |

| REP13 | This place is full of charm. | |

| REP14 | I feel very nostalgic about this place. | |

| Mental recovery | MR1 | This trip enhanced my sense of achievement. |

| MR2 | This trip increased my motivation in life. | |

| MR3 | This trip boosted my confidence. | |

| MR4 | This trip strengthened my sense of responsibility | |

| MR5 | This trip relieved my stress. | |

| MR6 | This trip stabilized my emotions. | |

| MR7 | This trip helped me relax | |

| MR8 | This trip made me feel joyful. | |

| MR9 | This trip made life feel more enjoyable | |

| MR10 | This trip strengthened my relationships with friends and family. | |

| MR11 | This trip improved my ability to handle interpersonal relationships | |

| MR12 | This trip helped me balance work and life better. | |

| MR13 | This trip alleviated my fatigue. | |

| MR14 | This trip restored my vitality. | |

| MR15 | This trip helped me focus on a single task. | |

| MR16 | This trip reduced the impact of external distractions. | |

| MR17 | This trip improved my work (or study) efficiency. | |

| Positive emotion | PE1 | On this trip, I was active. |

| PE2 | On this trip, I was enthusiastic. | |

| PE3 | On this trip, I was happy. | |

| PE4 | On this trip, I was elated. | |

| PE5 | On this trip, I was excited. | |

| PE6 | On this trip, I was proud. | |

| PE7 | On this trip, I was delighted. | |

| PE8 | On this trip, I was energetic. | |

| PE9 | On this trip, I was grateful. | |

| Subjective well-being | SW1 | This trip improved my quality of life. |

| SW2 | This trip made me feel very pleased. | |

| SW3 | This trip made me feel satisfied. | |

| SW4 | Most of the time, my life is close to my ideal. | |

| SW5 | My current life situation is quite good. | |

| SW6 | This trip increased my satisfaction with life. | |

| SW7 | I have achieved the most important things in life. | |

| SW8 | If life could start over, there is not much I would want to change. | |

| SW9 | I am grateful for this trip. |

| Indicator | Item | Frequency | % |

| Sex | Female | 249 | 49.4 |

| Male | 255 | 50.6 | |

| Age | Under 18 | 24 | 4.8 |

| 18-24 | 92 | 18.3 | |

| 25-34 | 84 | 16.6 | |

| 35-44 | 70 | 13.9 | |

| 45-54 | 71 | 14.1 | |

| 55-64 | 65 | 12.9 | |

| 64 above | 98 | 19.4 | |

| Personal annual income | Under 24,000 | 167 | 33.2 |

| 24,000-60,000 | 120 | 23.8 | |

| 60,001-12,000 | 112 | 22.2 | |

| 120,000 above | 105 | 20.8 | |

| Education | Junior Secondary and below | 71 | 14.1 |

| High School and Secondary School | 165 | 32.1 | |

| College and Undergraduate | 196 | 38.9 | |

| Postgraduate and above | 72 | 14.9 | |

| Job | Civil servant | 77 | 15.3 |

| Managerial personnel | 27 | 5.4 | |

| Private owner | 32 | 6.3 | |

| Wait for employment | 32 | 6.3 | |

| Professional technical personnel | 28 | 5.6 | |

| Peasant | 47 | 9.4 | |

| Student | 113 | 22.4 | |

| Other | 58 | 11.5 | |

| Unit staff | 90 | 17.8 | |

| Number of visits | 1 time | 173 | 34.3 |

| 2 times | 116 | 23.0 | |

| 3 times | 88 | 17.5 | |

| 4 times | 39 | 7.7 | |

| 5 times and above | 88 | 17.5 |

| Variables | Variable quantity | Standardized factor loading | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s Alpha | KMO |

| Natural environment perception | NAP1 | 0.775 | 0.868 | 0.774 | 0.845 | 0.844 |

| NAP2 | 0.762 | |||||

| NAP3 | 0.599 | |||||

| NAP4 | 0.66 | |||||

| NAP5 | 0.388 | |||||

| NAP6 | 0.835 | |||||

| NAP7 | 0.711 | |||||

| NAP8 | 0.872 | |||||

| NAP9 | 0.788 | |||||

| NAP10 | 0.595 | |||||

| NAP11 | 0.537 | |||||

| NAP12 | 0.644 | |||||

| NAP13 | 0.565 | |||||

| NAP14 | 0.71 | |||||

| NAP15 | 0.801 | |||||

| NAP16 | 0.89 | |||||

| NAP17 | 0.773 | |||||

| Restorative environment perception | REP1 | 0.634 | 0.938 | 0.703 | 0.834 | 0.816 |

| REP2 | 0.724 | |||||

| REP3 | 0.528 | |||||

| REP4 | 0.75 | |||||

| REP5 | 0.436 | |||||

| REP6 | 0.286 | |||||

| REP7 | 0.718 | |||||

| REP8 | 0.585 | |||||

| REP9 | 0.425 | |||||

| REP10 | 0.779 | |||||

| REP11 | 0.81 | |||||

| REP12 | 0.671 | |||||

| REP13 | 0.676 | |||||

| REP14 | 0.627 | |||||

| Mental recovery | MR1 | 0.691 | 0.911 | 0.789 | 0.854 | 0.814 |

| MR2 | 0.748 | |||||

| MR3 | 0.743 | |||||

| MR4 | 0.675 | |||||

| MR5 | 0.452 | |||||

| MR6 | 0.681 | |||||

| MR7 | 0.709 | |||||

| MR8 | 0.705 | |||||

| MR9 | 0.696 | |||||

| MR10 | 0.754 | |||||

| MR11 | 0.878 | |||||

| MR12 | 0.713 | |||||

| MR13 | 0.865 | |||||

| MR14 | 0.84 | |||||

| MR15 | 0.744 | |||||

| MR16 | 0.607 | |||||

| MR17 | 0.639 | |||||

| Positive emotion | PE1 | 0.715 | 0.818 | 0.772 | 0.912 | 0.882 |

| PE2 | 0.138 | |||||

| PE3 | 0.672 | |||||

| PE4 | 0.762 | |||||

| PE5 | 0.577 | |||||

| PE6 | 0.773 | |||||

| PE7 | 0.689 | |||||

| PE8 | 0.699 | |||||

| PE9 | 0.717 | |||||

| Subjective well-being | SW1 | 0.656 | 0.927 | 0.721 | 0.812 | 0.831 |

| SW2 | 0.546 | |||||

| SW3 | 0.537 | |||||

| SW4 | 0.663 | |||||

| SW5 | 0.599 | |||||

| SW6 | 0.637 | |||||

| SW7 | 0.658 | |||||

| SW8 | 0.897 | |||||

| SW9 | 0.654 |

| Variables | NEP | REP | MR | PE | SW |

| NEP | 0.774 | ||||

| REP | 0.731 | 0.703 | |||

| MR | 0.667 | 0.637 | 0.789 | ||

| PR | 0.585 | 0.561 | 0.821 | 0.772 | |

| SW | 0.478 | 0.526 | 0.831 | 0.774 | 0.721 |

| Square root of AVE | 0.880 | 0.838 | 0.888 | 0.879 | 0.849 |

| Indicators | Absolute Fit Indicator | Value-Added Fitness Indicator | Simplicity Fitness Indicator | ||||

| Specific indicators | x²/df | RMSEA | NFI | TLI | CFI | PNFI | PGFI |

| Judgment Criteria | (1-5) | <0.08 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.5 | >0.5 |

| Measurement results | 3.384 | 0.063 | 0.917 | 0.883 | 0.924 | 0.834 | 0.611 |

| Fitness Evaluation | Ideal | Ideal | Ideal | Acceptable | Ideal | Ideal | Ideal |

| Hypothesis | Pathway relationship | Standardized factor loading | SE | P |

| H1 | Natural environment perception → Mental recovery | 0.715 | 0.105 | *** |

| H2 | Natural environment perception → Restorative environment perception | 0.538 | 0.103 | *** |

| H3 | Restorative environment perception → Mental recovery | 0.672 | 0.107 | *** |

| H4 | Mental recovery → Subjective well-being | 0.762 | 0.057 | *** |

| Hypothesis | Total indirect effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Z | P |

| H5 | 0.233 | 0.023 | 0.143 | 0.234 | 9.949 | 0.000 |

| H6 | 0.194 | 0.027 | 0.107 | 0.212 | 7.148 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).