1. Introduction

Vestibular schwannomas (VS) represent 8% of all intracranial tumors and, with an incidence of 19.4 per million, and are classified as benign central nervous system (CNS) tumors [

1]. Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) has become an established procedure for the treatment of VS since the first publication by Hirsch et al. in 1979 [

2]. This therapeutic option has emerged as the first-line treatment particularly for small symptomatic and/or growing tumors, as also recommended in 2020´s EANO guidelines proposed by the "vestibular schwannoma task force" of the EANO (European Association of Neuro-Oncology) [

3].

VSs are usually clinically characterized by unilateral hearing loss (94%) and unilateral tinnitus (68%). The incidence of vestibular symptoms such as dizziness and balance disorders varies widely (17%-75%) and is clinically underreported [

4,

5]. In VS patients, local tumor control and hearing preservation are generally reported as the main outcomes, as these parameters can be objectified reliably and reproducibly using valid measurement methods.

However, previous studies have shown that continuous dizziness is a strong predictor of disability and reduced quality of life in patients with VS (6-9). Hence an objective clinical evaluation of balance disorders and vertigo symptoms in VS patients often is challenging due to the non-specific symptoms that are described by the patient. Therefore, available studies investigating outcome after radiosurgery (SRS) with valid objective data addressing vestibular symptoms beyond subjective patient reports are scarce [

10], especially after robotic guided SRS. In order to systematically evaluate the incidence and severity of vestibular symptoms, we introduced a well-studied PROM (Patient Reported Outcome Measure) to assess and quantify vestibular symptoms after SRS. The 25-item Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) is the most commonly used questionnaire for clinical assessment of impairment caused by balance disorders and vertigo symptoms [

11,

12].

The aim of this study was to (i) investigate whether the DHI can be proved to be a feasible and valid tool for measuring vestibular symptoms before and during follow-up after robotic SRS. Furthermore, (ii) we intended to elucidate patient´s individual longitudinal course of potential vestibular symptoms prior to, at 6 month and at last available follow up after robotic guided SRS and (iii) to correlate these findings with clinical and treatment related parameters.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

All patients who (i) were treated in our institution between November 2012 and April 2022 for an unilateral VS with robotic guided SRS by Cyberknife, (ii) who had at least two clinical and radiological follow up visits ≥ 6 month after SRS treatment and (iii) who completed the DHI questionnaire correctly before SRS, at the 6 month FU and at their individual last FU were included for this retrospective analysis.

2.2. Data Acquisition

Due to the retrospective nature of the present single center analysis, approvement by the local ethics committee was waived. All clinical data were retrieved from patient´s (electronical) records. We documented age, gender, date of SRS treatment, tumor volume, Koos grade, type of pre-treatment, and date of follow-up exams including MRI and clinical findings (initial and during follow-up). The presence or absence of vestibular symptoms was assessed using subjective criteria (e.g. patient-reported dizziness) and clinical examinations before and after SRS. In addition, relevant irradiation parameters such as irradiation doses (surface, minimum, maximum and mean dose in Gy, isodose, coverage and nCI) were determined.

2.3. Evaluation of Vestibular Symptoms Using the DHI

To asses patient´s vestibular symptoms we applied the DHI questionnaire, which is now routinely used as part of our standardized evaluation battery for patients with VS prior and during follow-up after SRS. Each question belongs to one of 3 subgroups which represent functional, emotional and physical aspects of vertigo and balance disorders [

12]. The possible responses to each item are either ‘‘no’’, ‘‘sometimes,’’ or ‘‘yes.’’ A ‘‘no’’ is scored 0 points, a ‘‘sometimes’’ is scored 2 points, and a ‘‘yes’’ is scored 4 points.

Since there are a total of 25 questions, the maximum score is 100 points, indicating the maximum self-perceived dizziness handicap. The minimum score is 0, meaning that no handicap due to dizziness or balance disorders is perceived. According to Jacobsen et al [

12] a minimum change of 18 points is considered as true change in DHI score. Furthermore, the DHI score results in four severity grades 0 to 3. A score of 0 to 14 indicating ‘‘none,’’ 16 to 34 ‘‘mild’’, 36 to 52 ‘‘moderate’’, and 54 or greater designating ‘‘severe’’ handicap.

2.4. SRS Treatment Planning and Delivery

The VS and potentially vulnerable adjacent structures (e.g. brainstem, cerebellum, trigeminal nerve) were contoured on a planning CT (Toshiba Aquilon) with one mm slice thickness and on a defined set of MRI series comprising contrast enhanced T1, T2 and FLAIR weighted images (Phillips MR-Scanner, 1.5 or 3 Tesla) registered to the planning CT. The contouring was performed by neurosurgeons experienced in radiosurgery. For robotic Cyberknife SRS, the patient was immobilized on the robotic Cyberknife treatment table (Accuray, Sunnyvale, California) by means of a custom-made aquaplast mask. For treatment planning, the software Multiplan v4.5 (since 2016 v4.6) was used. The final irradiation plan was evaluated in an interdisciplinary consensus meeting between the stereotactic neurosurgeon, a radiation oncologist experienced in SRS, and a medical physicist.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

For descriptive statistics, continuous values are given in median and range or mean and standard deviation, ordinal and categorical variables are shown in counts and percentage. Descriptive summaries were prepared for the patients’ demographics and radiation parameters. A paired t-test (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test or) was used to compare the DHI total score before and after treatment. An unpaired t-test (Mann-Whitney test) was used to compare subgroups of patients with or without Vestibular symptoms. For correlation analysis between vestibular symptoms assessed during clinical follow-up and the four DHI grades (none, mild, moderate and severe) before and at LFU, a chi-square test was used. Furthermore, correlation analysis with regard to true change of DHI score were done by a binary logistic regression. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed using the software Graphpad PRZM 10 and SPSS 29.0.1.(IBM statistics, Chicago IL).

3. Results

3.1. Patient Cohort and Tumor Characteristics

A total of 128 patients (female/male = 54/74) with a median age of 60 years (range 20-82 years) were analyzed (Tab. 1). Overall median follow-up was 36 months (range, 12-106 months) and mean follow-up was 42 ± 25.9 months. Seventeen patients (13%) were treated for a recurrent VS after previous surgery. The median marginal dose delivered to all tumors was 13 Gy (range, 12-14 Gy). The median prescription isodose was 80 (range, 65-82%). According to the Koos classification, about two third (n=79, 62%) of the patients had Koos grade I or II. The overall average tumor volume was 1.33 ±1.3 cm3, the median 0.95 cm3 (range 0.04-7.1). Based on previously suggested criteria according to Rueß et al [

13], one patient (0.8%) experienced tumor progression 44 months after SRS. He was retreated with a second radiosurgery (prescribed dose: 13 Gy to a 80% isodose in one fraction). The other patients in the collective showed stable tumor size or regression. The most frequent symptom prior to SRS was hearing impairment (n=101, 79%). Overall, 11% of the patients (n=14) had a complete loss of hearing.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and treatment parameters of patients. Data are presented as median value with range in bracketts.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and treatment parameters of patients. Data are presented as median value with range in bracketts.

| Patient characteristics |

|

| Total no. of patients |

128 |

| Gender (m:f) |

54 : 74 |

| Recurrent AN |

17 (13%) |

| o. of Koos-Grade |

Koos I: 30 Koos II: 49 Koos III: 43 Koos IV: 5 |

| Clinical and radiological FU (months) |

36 (12 – 106) |

| Age (years) |

60 (range: 20-82) |

| Tumor volume (cm3) |

0.95 (range: 0.04-7.1) |

| median FU (months) |

36 (range: 12- 106) |

| Initial symptoms and signs |

| Acute hearing loss (%) |

25 (19%) |

| Hearing disturbance (%) |

101(79%) |

| Vestibular symptoms (Vsym) (%) |

81 (63%) |

| Deafness (%) |

14 (11%) |

| CN V impairment (%) |

5 (4%) |

| CN VII impairment (%) |

14 (11%) |

| DHI categories before treatment |

None (0-14)

Mild (16-34)

Moderate (36-52)

Severe (54-100) |

48 (38.3%)

36 (28.1%)

17 (13.3%)

26 (20.3%) |

| Radiation parameters |

|

| Marginal dose (Gy)* |

13 (range: 12 – 14) |

| Dose prescription, isodose (%)* |

80 (range: 65 - 82) |

| Coverage (%) |

99.6 (range: 94 - 100) |

| Dmin

|

12.6 (range: 9.3 - 13.2) |

| Dmean

|

14.7 (range: 12.7 - 16.8) |

| Dmax |

16.4 (range: 15-20) |

| nCI |

1.19 (range: 1.04-1.6) |

3.2. DHI Scores and Vestibular Function

Eighty-one (63%) of the patients had vestibular symptoms prior to SRS, which clinically improved in 25% (n=20) after SRS. In contrast, 21 patients (26%) reported a deterioration in vestibular symptoms after SRS. About one third of the patients (n=47, 36%) did not show vestibular symptoms before SRS. Twelve (25%) of these patients experienced transient (n=9) or permanent (n=3) new onset of vestibular symptoms.

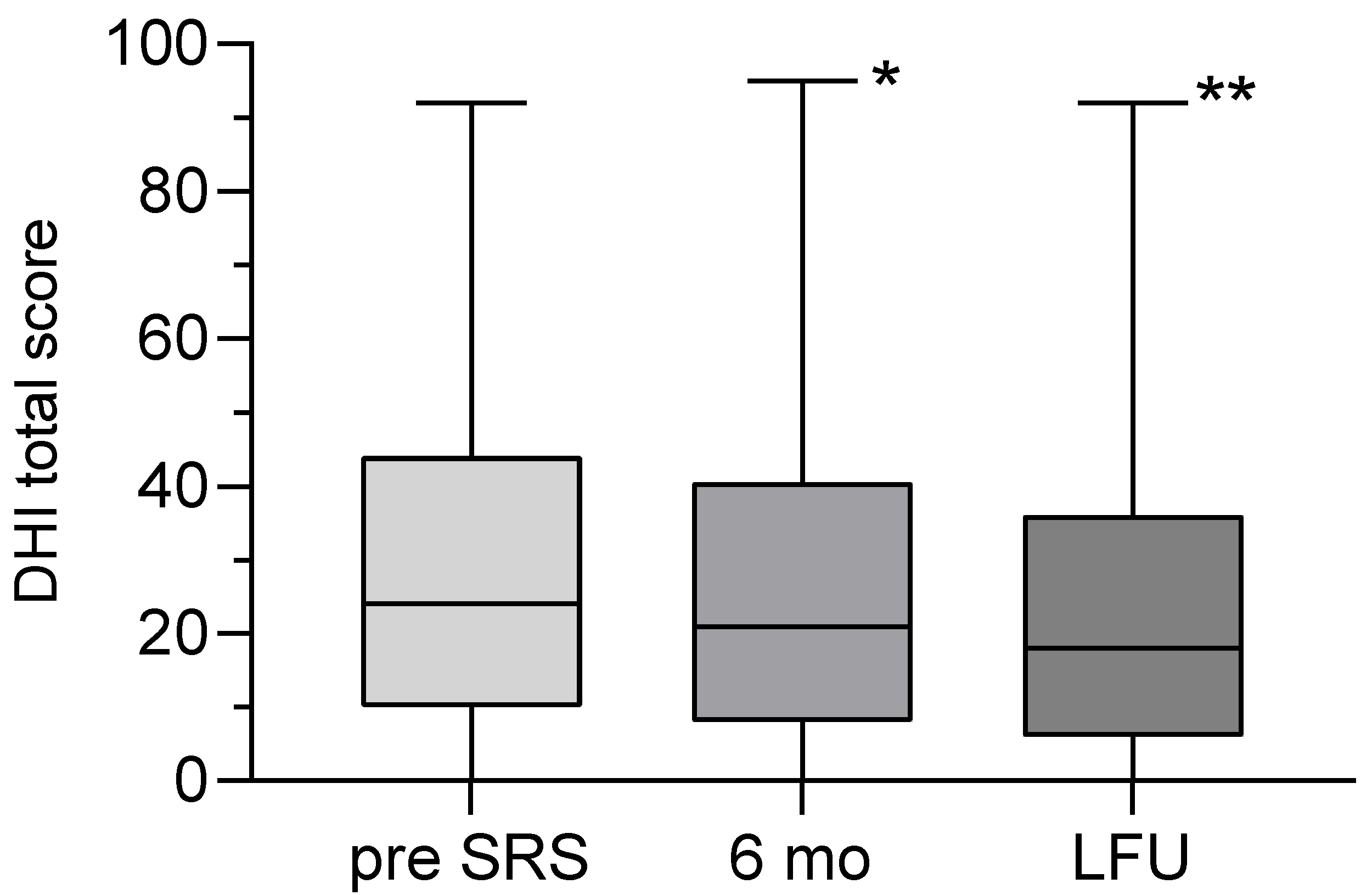

All patients completed the DHI as required at the defined time points, demonstrating the feasibility of this measure. The mean DHI total score was 29.4 ± 25.3 (range: 0-92) before SRS and 25.5 ± 24.7 (range: 0-92) at LFU. The decrease in DHI total score was statistically significant (p=0.0058) (

Figure 1). Before SRS, out of 73 patients with a DHI score above 18 points, an improvement (minimum decrease of 18 points) was seen in 11% (n=8/73) after 6 months and in 30% (n=22/73) at LFU. In contrast, 120 patients had a DHI under 82 points and a true worsening of DHI (minimum increase of 18 points) was seen in 2.5% (n=3/120) after 6 months and 9% (n=11/120) at LFU. The binary logistic regression model did not show any influences of several variables (tab. 3) on the (log) odds of DHI improvement or deterioration at LFU.

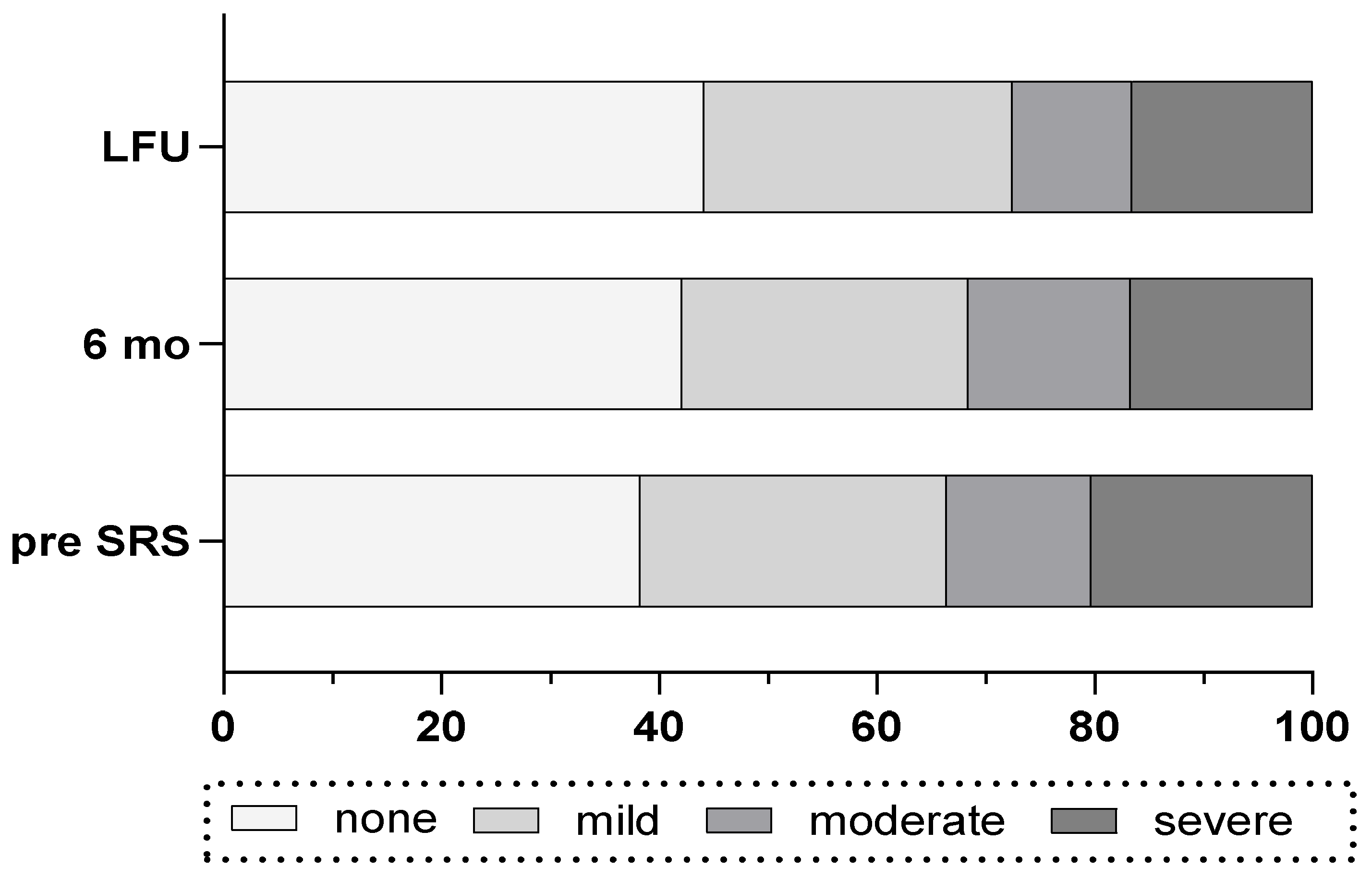

Before SRS, most of patients had a DHI grade of “none” (n=48) or “mild” (n=36) and a lower amount of patients had “moderate” (n=17) or “severe” (n=26) (Tab. 1). During FU, in 33% of the patients (n=27 of 80) the DHI improved by one or more grades whereas in 17% (n=17 of 102) of the patients deterioration by one or more of DHI grade was observed. Overall, the amount of patients with “none” grade of DHI increased and the amount of patients with “severe” DHI score decreased during FU period (

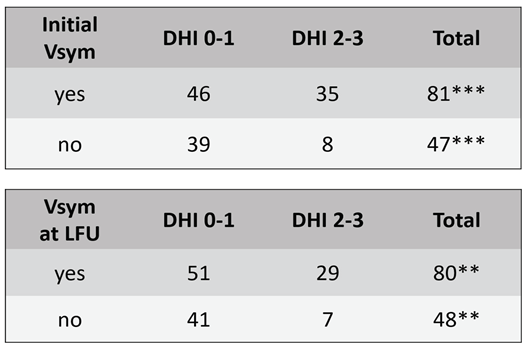

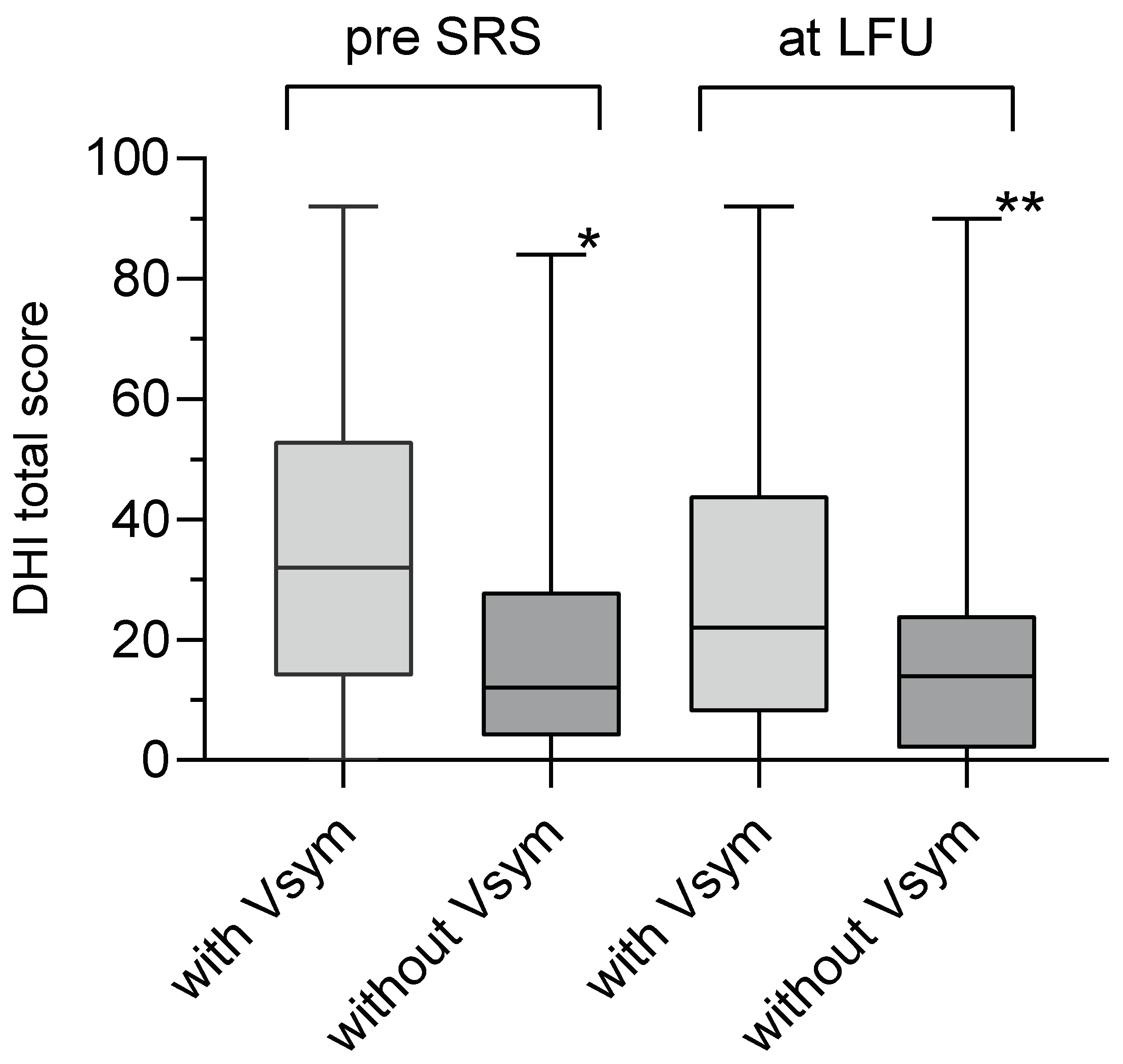

Figure 2). The incidence of vestibular symptoms before and at LFU correlated well with the grades of DHI (Chi-Square p=0.002, Tab. 2). Likewise, the group of patients with vestibular symptoms before SRS had a significantly higher mean DHI total score (34.9 ± 2.9) than the group of patients without vestibular symptoms (20 ± 3.1, unpaired t-test, p<0.0004). The same accounts for the patients with vestibular symptoms at LFU (

Figure 3).

The deterioration of vestibular symptoms showed a positive correlation with the gradual deterioration of the DHI (Chi-Square p=0.028). However, there was no correlation between the gradual improvement in DHI and the improvement in vestibular symptoms (Chi-Square p=0.17).

Table 2.

Chi-square test shows a correlation of the categories DHI 0-1 (none-mild) and DHI 2-3 (moderate-severe) with the incidence of Vsym before SRS (***p=0.002) and at LFU (**p=0.008).

Table 2.

Chi-square test shows a correlation of the categories DHI 0-1 (none-mild) and DHI 2-3 (moderate-severe) with the incidence of Vsym before SRS (***p=0.002) and at LFU (**p=0.008).

Table 3.

Statistical results of a binaric logistic regression showing that the true change ( ≥ 18 points) of DHI score in the direction of improvement or deterioration is not influenced by any of the tested variables (p>0.05).

Table 3.

Statistical results of a binaric logistic regression showing that the true change ( ≥ 18 points) of DHI score in the direction of improvement or deterioration is not influenced by any of the tested variables (p>0.05).

| |

p-values (binaric logistic regression) |

| Variable |

DHI improved (n=22/73) |

DHI declined

(n=11/120) |

| Age |

0.550 |

0.920 |

| Gender |

0.867 |

0.861 |

| Pretreatment |

0.474 |

0.200 |

| Tumorvolume |

0.408 |

0.998 |

| Dmax |

0.252 |

0.762 |

| Dmean |

0.754 |

0.881 |

| Dmin |

0.561 |

0.138 |

| Coverage |

0.634 |

0.255 |

| nCI |

0.128 |

0.620 |

4. Discussion

Several studies (

7,

14,

15) have shown that dizziness and vertigo affect the quality of life (QOL) of VS patients more than hearing loss or facial neuropathy. Hearing loss in VS patients can reliably be measured using well established methods such as pure-tone audiometry, speech audiometry or otoacoustic emissions (Zhang, et al., 2024). Conversely, the quantification and objectification of vestibular symptoms represents a diagnostic challenge and requires a multidimensional approach, as the underlying etiology is often difficult to assess and may comprise neurological, psychological and cardiovascular comorbidities of varying intensity. Although several test protocols for instrument-based diagnostics such as the caloric test or electronystagmography are available, these tests are inconsistently and infrequently applied.

Vestibular symptoms are difficult to assess and interpret by clinical examination alone, and VS patients reporting about ´dizziness´ often cannot separate objectively between vertigo, postural imbalance or psychological aspects of their imbalance [

16]. In addition, the perceived impairment of VS patients caused by vestibular symptoms is difficult to assess and to compare among patients. There are only a few standardized reporting tools available, which encompass the Vertigo Symptom Scale (VSS), Visual Vertigo Analogue Scale (VVAS) or Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI). The latter is the most commonly used instrument and has been validated for consistency and reliability and has been routinely applied in patients with peripheral vestibular disorders. With regard to VS patients treated with SRS, the DHI has so far only been used in a few series of patients undergoing Gamma-Knife SRS [

10,

17,

18]. In addition, published studies investigating dizziness and vertigo in VS patients vary widely regarding the length of follow-up and mostly lack long-term data [

19]. For this reason, we here for the first time applied the DHI as a longitudinal and standardized reporting tool before and after robotic SRS of unilateral VS. All patients completed the DHI correctly so that each questionnaire could be evaluated. This shows the usability of this instrument and goes in line with former research [

20].

We found an improvement of the total DHI score in about 30% of our cohort during follow-up which compares well with a study by Wackym et al. [

18] who examined 55 patients with sporadic VS. The majority of patients did not suffer from significant vertigo either before or after Gamma Knife SRS. Only the group of elderly patients (> 65 years of age) showed a significant improvement of the total DHI score. In contrast to these results, we did not observe an improvement of DHI influenced by age (tab. 3). In addition, we found that the DHI total score changes significantly over time. A significant factor for the improvement of the DHI score after SRS was the duration of the FU period as also shown by Wackym et al and Pollock et al [

17,

18]. The authors conclude that long-term follow-up is necessary to predict the course of vestibular dysfunction in VS patients and to detect improvements [

17,

18].

Neither deterioration nor improvement of DHI total score was influenced by any of the tested variables (tab. 3). At least with regard to the dose, this finding is not necessarily surprising, since the dose parameters of the tumor itself were tested here. To what extent the radiation exposure of the vestibule plays a role remains still unclear. To date, several studies [

21] have examined hearing preservation as a primary endpoint with regard to the radiation dose administered to the cochlea. It has been shown that a low cochlear dose is beneficial for the long-term preservation of hearing [

21,

22]. In contrast, only one study to date [

23] has investigated the influence of vestibular radiation dose on vestibular outcome measured by vestibular tests and subjective dizziness. The authors report that a vestibular dose D

min of 5 Gy and above worsened dizziness in patients. In contrast, the D

mean and D

max received by the vestibule were significantly lower in patients who had improved caloric function. These results suggest that the radiation dose may have an effect on vestibular symptoms after SRS. Unfortunately, the study did not use a standardized questionnaire such as the DHI which makes it difficult to compare subjective symptoms.

4.1. Pros and Cons of the DHI Score and Classification

Studies have shown that the results of the subscales in the DHI questionnaire to determine the degree of dizziness are biased in certain cases. One example, is that a patient's avoidance behavior may suggest improvement [

24]. In addition, Cohen et al [

25] points out that the use of three response options may limit the ability to register small changes and may not get the full range of disability experienced by patients. Nevertheless, several studies which use the DHI as an outcome assessment for vestibular symptoms found the DHI responsive to changes during FU (26-28). For instance, the study of Zanardini et al [

28] used the DHI to assess vestibular rehabilitation and showed a significant improvement in correlation with clinical status. In most cases of cited studies (26-28), however, the mean change in score has fallen below the minimum change of 18 points. In our study, this leads to the confusing fact that there are patients which improve from “moderate” to “mild” category with only two points change in DHI score from. In the original work of Jacobson and Newman the authors recommended a change of 18 points to be 95% certain of a true change [

12]. We implemented this recommendation in our study accordingly, considering only a difference of at least 18 points in total DHI scores as a true change. It is therefore possible that patients improving from one category to another (e.g. “moderate” to “mild”) are not necessarily considered having experienced a true change in their vestibular symptoms. Thus, the four DHI categories (“none” to “severe”) are not particularly precise to map a real change and cannot be understood solely as outcome parameters.

A study of Duong et al [

20] validated the German version of the DHI, which was used in our study in a longitudinal evaluation of 50 patients. The patients included in this study showed a high level of compliance in answering the questionnaire. This was also the case in our study. Finally, the authors concluded that the DHI is a viable option for the assessment and monitoring of treatment outcomes. Further, the authors found the DHI useful for documentation of patients’ disorders and thus for quality assurance. The latter is especially important for SRS against the background of the associated dose exposure of organs at risk like the vestibule.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we were able to show that the total DHI scores in patients treated with SRS significantly improved during follow-ups. However, only a minority of VS patients suffer from severe DHI scores before and after SRS. The improvement of vestibular symptoms as documented by the application of a valid questionnaire in VS patients treated with SRS could enable clinicians to better understand and anticipate the frequency, severity and development of vestibular symptoms in a consistent manner. In addition, our study has proven that the DHI is a feasible and valid instrument in collecting these data on vestibular symptoms in a standardized and comparable way. To further refine data of the impact of RS dosimetry on vestibular function, studies using standardized reporting tools like the DHI are particularly important, leading to more homogeneity and comparability of the study results.

References

- Stangerup, S.E.; Tos, M.; Thomsen, J.; Caye-Thomasen, P. True incidence of vestibular schwannoma? Neurosurgery 2010, 67, 1335–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, A.; Noren, G.; Anderson, H. Audiologic findings after stereotactic radiosurgery in nine cases of acoustic neurinomas. Acta Otolaryngol. 1979, 88, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldbrunner, R.; Weller, M.; Regis, J.; Lund-Johansen, M.; Stavrinou, P.; Reuss, D.; Evans, D.G.; Lefranc, F.; Sallabanda, K.; Falini, A.; et al. EANO guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of vestibular schwannoma. Neuro Oncol. 2020, 22, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shilo, S.; Hannaux, O.; Gilboa, D.; Ungar, O.J.; Handzel, O.; Abu Eta, R.; Muhanna, N.; Oron, Y. Could the Audiometric Criteria for Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss Miss Vestibular Schwannomas? Laryngoscope 2023, 133, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.F.; Nilsen, K.S.; Vassbotn, F.S.; Moller, P.; Myrseth, E.; Lund-Johansen, M.; Goplen, F.K. Predictors of vertigo in patients with untreated vestibular schwannoma. Otol. Neurotol. 2015, 36, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrseth, E.; Moller, P.; Pedersen, P.H.; Lund-Johansen, M. Vestibular schwannoma: surgery or gamma knife radiosurgery? A prospective, nonrandomized study. Neurosurgery 2009, 64, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, S.K.; Kasbekar, A.V.; Baguley, D.M.; Moffat, D.A. Audiovestibular factors influencing quality of life in patients with conservatively managed sporadic vestibular schwannoma. Otol. Neurotol. 2010, 31, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breivik, C.N.; Nilsen, R.M.; Myrseth, E.; Finnkirk, M.K.; Lund-Johansen, M. Working disability in Norwegian patients with vestibular schwannoma: vertigo predicts future dependence. World Neurosurg. 2013, 80, e301–e305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breivik, C.N.; Nilsen, R.M.; Myrseth, E.; Pedersen, P.H.; Varughese, J.K.; Chaudhry, A.A.; Lund-Johansen, M. Conservative management or gamma knife radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma: tumor growth, symptoms, and quality of life. Neurosurgery 2013, 73, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, M.L.; Tveiten, O.V.; Driscoll, C.L.; Neff, B.A.; Shepard, N.T.; Eggers, S.D.; Staab, J.P.; Tombers, N.M.; Goplen, F.K.; Lund-Johansen, M.; et al. Long-term dizziness handicap in patients with vestibular schwannoma: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2014, 151, 1028–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, B.; Serbetcioglu, B. Discussion of the dizziness handicap inventory. J. Vestib. Res. 2013, 23, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, G.P.; Newman, C.W. The development of the Dizziness Handicap Inventory. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 1990, 116, 424–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruess, D.; Schutz, B.; Celik, E.; Baues, C.; Junger, S.T.; Neuschmelting, V.; Hellerbach, A.; Eichner, M.; Kocher, M.; Ruge, M.I. Pseudoprogression of Vestibular Schwannoma after Stereotactic Radiosurgery with Cyberknife((R)): Proposal for New Response Criteria. Cancers 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myrseth, E.; Moller, P.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Goplen, F.; Lund-Johansen, M. Untreated Vestibular Schwannoma: Vertigo is a Powerful Predictor for Health-Related Quality of Life. Neurosurgery 2006, 59, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkowitz, O.; Han, Y.Y.; Talbott, E.O.; Iyer, A.K.; Kano, H.; Kondziolka, D.; Brown, M.A.; Lunsford, L.D. Gamma Knife Radiosurgery for Vestibular Schwannomas and Quality of Life Evaluation. Stereotact. Funct. Neurosurg. 2017, 95, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, G.S.; Jung, C.M.; Kim, J.H.; Son, E.J. Relationship of Vertigo and Postural Instability in Patients With Vestibular Schwannoma. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2018, 11, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, B.E.; Driscoll, C.L.; Foote, R.L.; Link, M.J.; Gorman, D.A.; Bauch, C.D.; Mandrekar, J.N.; Krecke, K.N.; Johnson, C.H. Patient outcomes after vestibular schwannoma management: a prospective comparison of microsurgical resection and stereotactic radiosurgery. Neurosurgery 2006, 59, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wackym, P.A.; Hannley, M.T.; Runge-Samuelson, C.L.; Jensen, J.; Zhu, Y.R. Gamma Knife surgery of vestibular schwannomas: longitudinal changes in vestibular function and measurement of the Dizziness Handicap Inventory. J. Neurosurg. 2008, 109, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayal, M.; Perez-Andujar, A.; Chuang, C.; Parsa, A.T.; Barani, I.J. Management of vestibular schwannoma: focus on vertigo. CNS Oncol. 2013, 2, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong Dinh, T.A.; Wittenborn, J.; Westhofen, M. [The Dizziness Handicap Inventory for quality control in the treatment of vestibular dysfunction]. HNO 2022, 70, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balossier, A.; Tuleasca, C.; Delsanti, C.; Troude, L.; Thomassin, J.M.; Roche, P.H.; Regis, J. Long-Term Hearing Outcome After Radiosurgery for Vestibular Schwannoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurosurgery 2023, 92, 1130–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Kawabe, T.; Koiso, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Matsumura, A.; Kasuya, H. Stereotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas: average 10-year follow-up results focusing on long-term hearing preservation. J. Neurosurg. 2016, 125, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermis, E.; Anschuetz, L.; Leiser, D.; Poel, R.; Raabe, A.; Manser, P.; Aebersold, D.M.; Caversaccio, M.; Mantokoudis, G.; Abu-Isa, J.; et al. Vestibular dose correlates with dizziness after radiosurgery for the treatment of vestibular schwannoma. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 16, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yardley, L.; Luxon, L.M.; Haacke, N.P. A longitudinal study of symptoms, anxiety and subjective well-being in patients with vertigo. Clin. Otolaryngol. Allied Sci. 1994, 19, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, H.S.; Kimball, K.T.; Adams, A.S. Application of the vestibular disorders activities of daily living scale. Laryngoscope 2000, 110, 1204–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enloe, L.J.; Shields, R.K. Evaluation of health-related quality of life in individuals with vestibular disease using disease-specific and general outcome measures. Phys. Ther. 1997, 77, 890–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowand, J.L.; Wrisley, D.M.; Walker, M.; Strasnick, B.; Jacobson, J.T. Efficacy of vestibular rehabilitation. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 1998, 118, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardini, F.H.; Zeigelboim, B.S.; Jurkiewicz, A.L.; Marques, J.M.; Martins-Bassetto, J. [Vestibular rehabilitation in elderly patients with dizziness]. Pro Fono 2007, 19, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).