1. Introduction

When first discovered, Buckminster fullerene (C

60) was thought to be of niche interests to astrophysics. Methods for producing C

60 in a lab were developed rapidly and it was discovered that fullerenes had many applications across physics, chemistry, astronomy and material science [

1]. Rapidly expanding studies of fullerenes quickly discovered that atoms and molecules could be trapped inside the hollow carbon cage [

2,

3,

4], these complexes were named endohedral fullerenes or just endofullerenes. When the internal atom or molecule is light enough, the rotation and vibration of the internal molecule becomes quantized and cannot be treated classically [

5]. When the internal atom or molecule of an endofullerene is heavy enough it maintains many of its individual properties [

2], similar to a molecule or atom inside of a carbon nano-tube. The internal molecule or atom is therefore protected from outside collisions while remaining effectively unperturbed. These properties have drawn attention from researchers due to possible applications to medical science, photovoltaics, quantum computing and electronics [

2,

3,

6].

Thanks to experimental developments over the last 40 years a wide range of molecules have been trapped inside fullerene cages [

3,

5]. Of particular interest is the development of molecular surgery, a process where a fullerene cage is chemically pried open allowing for an atom or small molecule to be placed inside before the fullerene is sealed again [

7]. Modern experimental methods allow for much greater control over what type of molecular or atom is trapped inside the fullerene and for more diverse sets of endofullerenes to be produced. With molecular endofullerenes more available then ever, more and more studies are focusing on the properties of the these endofullerenes rather than there production. Specifically, many of these studies focused on the translational and rotational energy of the trapped atom or molecule [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Some of these studies use the sum of pairwise Lennard-Jones type interactions instead of detailed quantum chemistry calculations as we present here. Studies of vibration are limited.

A molecule trapped inside a fullerene is analogous to a molecule within a helium droplet, a system which has also been studied extensively [

13,

14]. Studies have shown that molecules in these helium droplets can be aligned using a laser pulse despite the surrounding atoms [

15,

16,

17]. Since these systems are similar to endofullerenes, it may also be possible to manipulate the alignment of an internal molecule of an endofullerene using an external field as well. As we show, unlike in a helium droplet the rotational constant is not significantly altered inside the fullerene cage. The protection provided by the fullerene cage could also enhance coherence times in studies of alignment revivals. Long coherence times due to the fullerene cage have already been shown in proposed spin qubits using atomic endofullerenes [

6,

18].

This study focuses on the cage-induced alignment in molecules inside a fullerene. The fullerene creates a preferred axis for the internal molecule similar to an electric field used in alignment studies of free molecules. Our study focuses on two endofullerenes: N2@C60 and AlF@C60. We demonstrate how the fullerene cage shifts the spectroscopic constants of these internal molecules. We also briefly study the effects the fullerene has on the dipole moment of AlF. N2 represents a molecule with a highly covalent bond and a short equilibrium distance. While AlF has a much higher ionic character and a much longer equilibrium distance. This contrast between the two studied internal molecules helps provide insight on how a wider variety of molecules might behave while trapped inside a fullerene cage.

2. Methods

The optimized geometries and the energies of various configurations were all calculated using density functional theory (DFT). All calculations were performed using Gaussian 16 [

19]. We calculated the energy as a function of the angle from the z-axis

for many different DFT functionals. The main functionals we studied were the wB97XV functional, the B3LYP functional with dispersion and the APFD functional. These functionals were chosen because they all include dispersion. Dispersion is required to properly predict the van der Waals and ionic interactions between fullerene and the internal molecule. The work of Bacanu et al. [

20] compared spectroscopic data of He@C

60 to quantum chemistry calculations and showed the importance of including dispersion. In this study, the inclusion of the GD3BJ dispersion with the B3LYP functional marked a significant improvement over the B3LYP method without any dispersion. Overall we found that B3LYP with GD3BJ dispersion gave accurate results for both AlF@C

60 and N

2@C

60. This is the method we used for all the DFT calculations used in this study. All our calculations account for the basis set superposition error using the counterpoise method.

For the choice of basis set we ran calculations with the cc-pVnZ (n being D,T,Q,5 etc..) class of basis sets and the Def2nVZ class of basis sets. The Def2nVZ class of basis sets are optimized for DFT calculations and significantly smaller than there cc-pVnZ counter part. The cc-pVnZ proved to be impractical. For N

2@C

60 we used the Def2QVZ basis set particularly because it was the largest basis set that was still practical in terms of computation times. For AlF@C

60 the computation times were roughly double. To reduce computational cost, we used the Def2QVZ basis for the optimization and the Def2TVZ basis for calculations of the energy as a function of stretching and rotation. The energies for AlF@C

60 as a function of rotation were also found to be a factor of 10 larger then for N

2@C

60. Because of this, the difference between the Def2QVZ and Def2TVZ basis sets were significant for N

2@C

60 but not for AlF@C

60, justifying the use of the smaller basis. For calculations of the dipole moment of AlF@C

60, we used the same geometry predicted with the Def2QVZ basis set but calculated the dipole moment of this geometry using the Def2TVZpp basis. The Def2TVZpp basis was chosen because it gives the closets results for the dipole moment of free AlF [

21].

Using the results from the DFT calculations we can calculate various spectroscopic properties of the internal molecule. Couplings between rotational states can be calculated given a specific bond length for the internal molecule by expanding in the unperturbed rotational basis:

where

is the angle from the z-axis and

is the angle from the x-axis (the typical definitions for spherical coordinate). The Hamiltonian is then broken into two parts. The potential (

) produced from the DFT calculations is used to calculate the matrix elements of the perturbed Hamiltonian

:

where

R is some fixed bond length. The unperturbed Hamiltonian

, represents the rigid rotor Hamiltonian. This Hamiltonian is diagonal with its matrix elements given by

, where

is the rotational constant at equilibrium of the free molecule. The total Hamiltonian is then

. For calculations of the rotational states of the internal molecule in the unperturbed rotational basis, the internal molecule is assumed to be a rigid rotor. The energy is assumed to be constant when changing the angle from the x-axis

, in order to prevent the need to calculate a full energy surface. C

60 is roughly a sphere so this assumption has merit, although calculating the full energy surface would be beneficial.

We can account for the vibrational degrees of freedom by averaging across different rotations to obtain a potential as a function of bond length only. The rotationally averaged potential

is the expectation value of the potential, weighted with the rotational part of the wave function:

However as we show in Section:

Section 3, the rotational degrees of freedom of the internal molecule are fully decoupled from the radial ones. As a results,

for any value of

and

.

In typical quantum chemistry studies, a calculation is run when the nuclei are very far apart in order to estimate the bound state energy. In this case, large nuclear separation will result in strong interactions with the cage or even result in one of the nuclei exiting the cage. For this reason calculating the energy at a large internuclear separation cannot be used to accurately predict the binding energy. Knowing the energy as a function of nuclear separation is going to fit well to a morse potential, we can adjust the depth of the potential so that it fits as well as possible to the morse potential. Morse potentials converge to zero at infinity, so any potential which is not converging to zero will not fit well to a morse potential. If the potential fits well to a morse potential, it is reasonable to assume it will asymptotically approach zero. We adjusted the depth of the well until the R-squared value of the fit was maximized. This technique introduces a source of error but this error should be smaller than errors already introduced through the use of DFT. This technique has the benefit of allowing us to use existing work done for morse potentials particularly used to describe diatomic molecules [

22].

The averaged potential

can be fit to a morse potential to obtain the vibrational harmonic frequency, the first anharmonic correction, the rotational constant and the first correction to the rotational constant. Given a morse potential of the form:

where

a and

are the fit parameters corresponding to the width of the well and the depth of the well. The vibrational harmonic frequency

can be calculated using:

where

c is the speed of light and

is the reduced mass. The first anharmonic correction

is then given as:

where

h is planck’s constant. The rotational constant

is predicted via:

Finally the first correction to the rotational constant is:

These formulas were used to calculate the constants shown in

Table 1 for N

2@C

60 and AlF@C

60. The errors shown in

Table 1 come from errors in

and

a resulting from the fit. These errors are then propagated through the equations above.

3. Results

All constants predicted for AlF and

inside of C

60 are given in

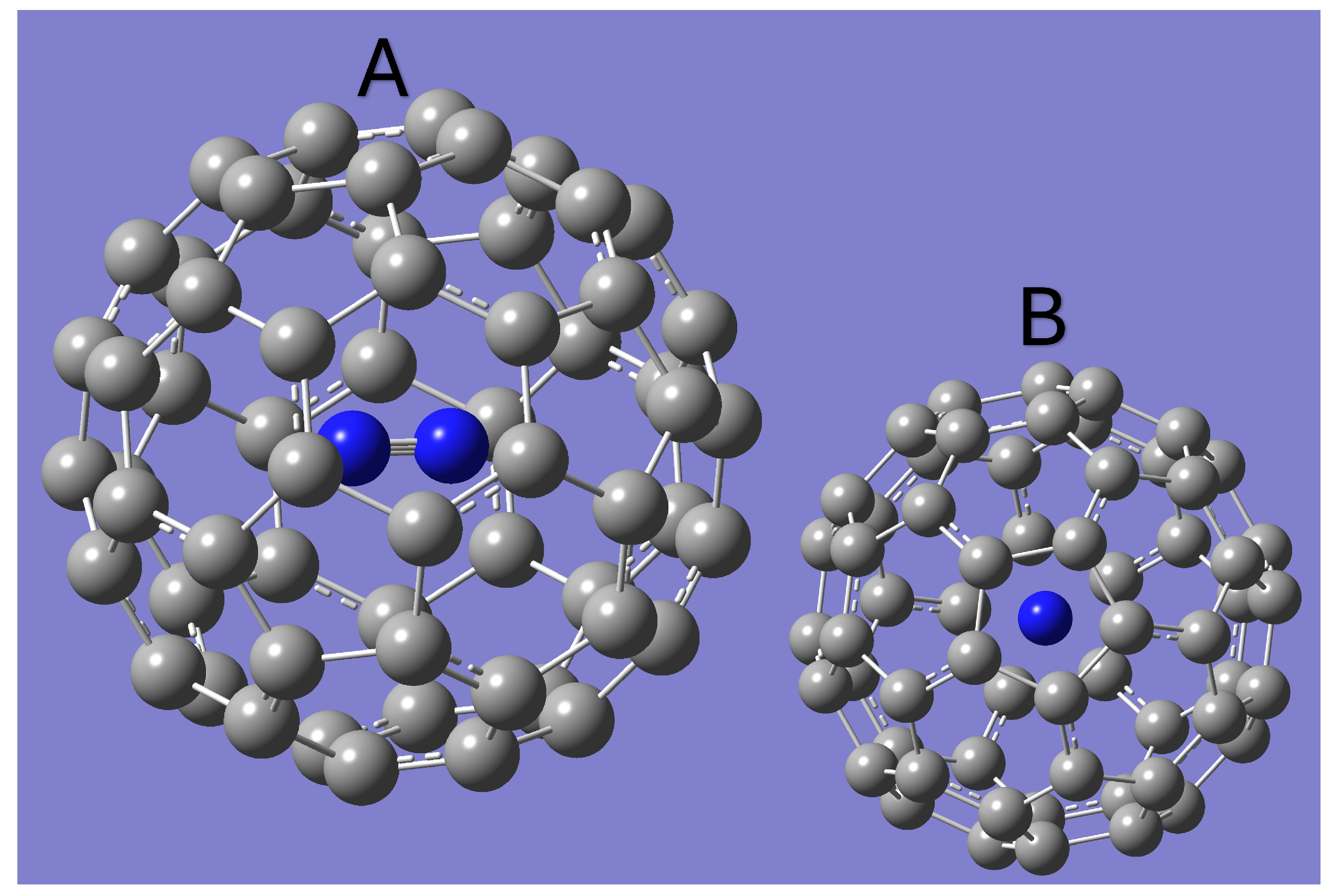

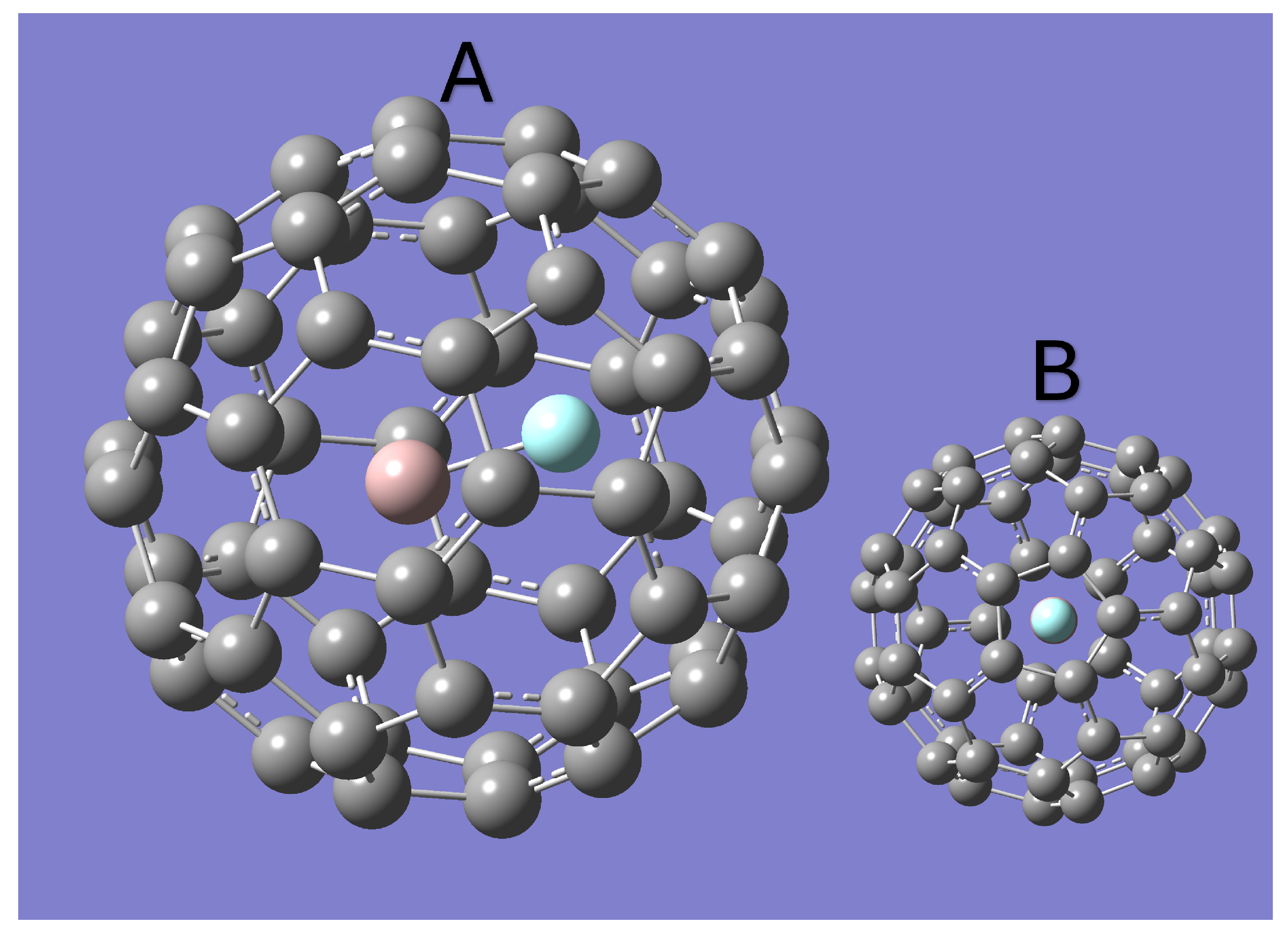

Table 1. The optimized Geometries for N

3@C

60 and AlF@C

60 are shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 respectively. Both optimized geometries have the internal molecule aligned with the z-axis. N

2 is found to be in the exact center of the fullerene, while AlF is slightly shifted off center. The equilibrium bond length of AlF inside the C

60 cage was found to be about 1.69 Åas compared to the 1.65 Åequilibrium bond length expected for free AlF [

23,

24]. For N

2, the equilibrium bond length inside of the C

60 cage was found to be 1.11 Åcompared to 1.10 for the free molecule [

23,

24].

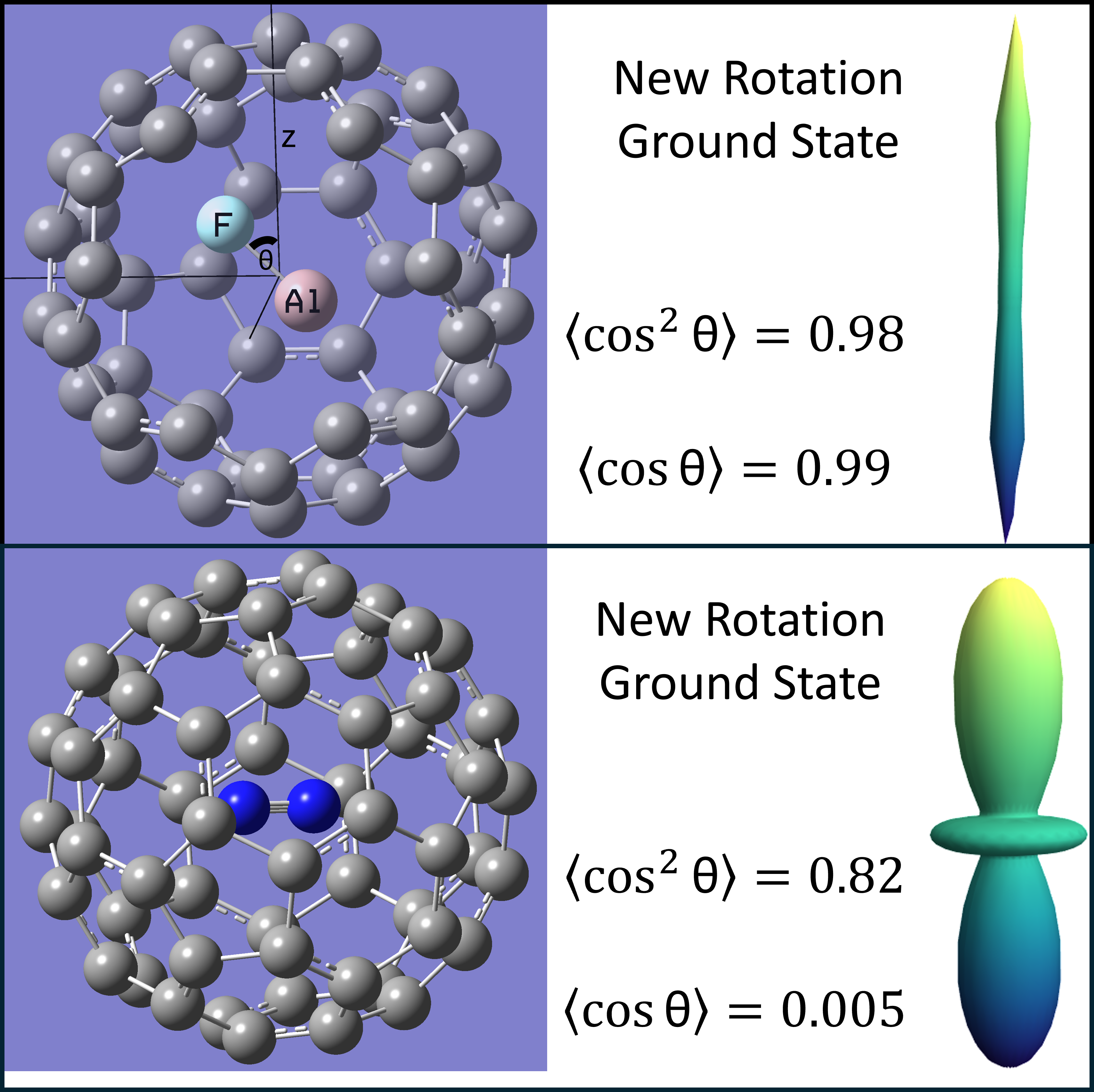

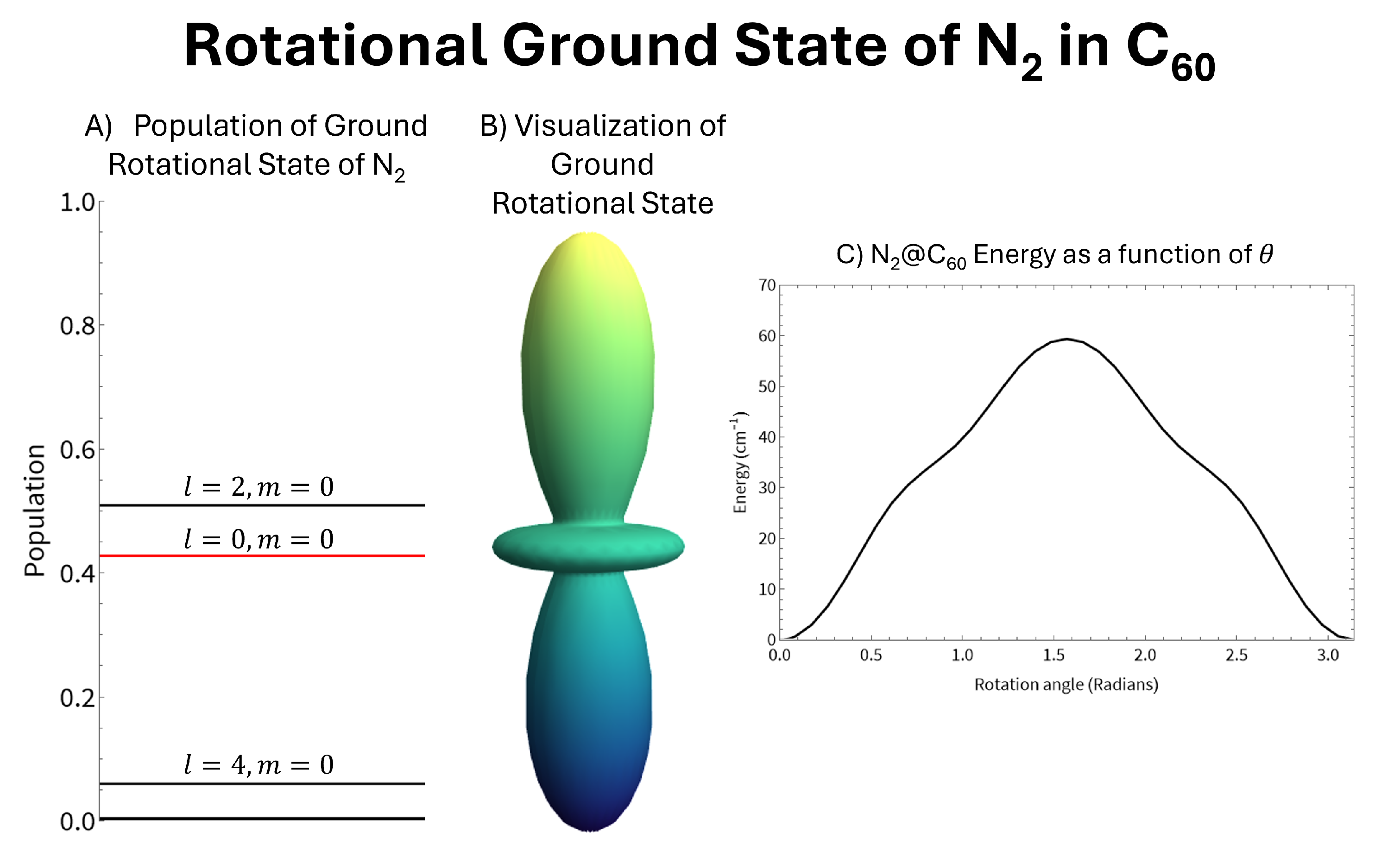

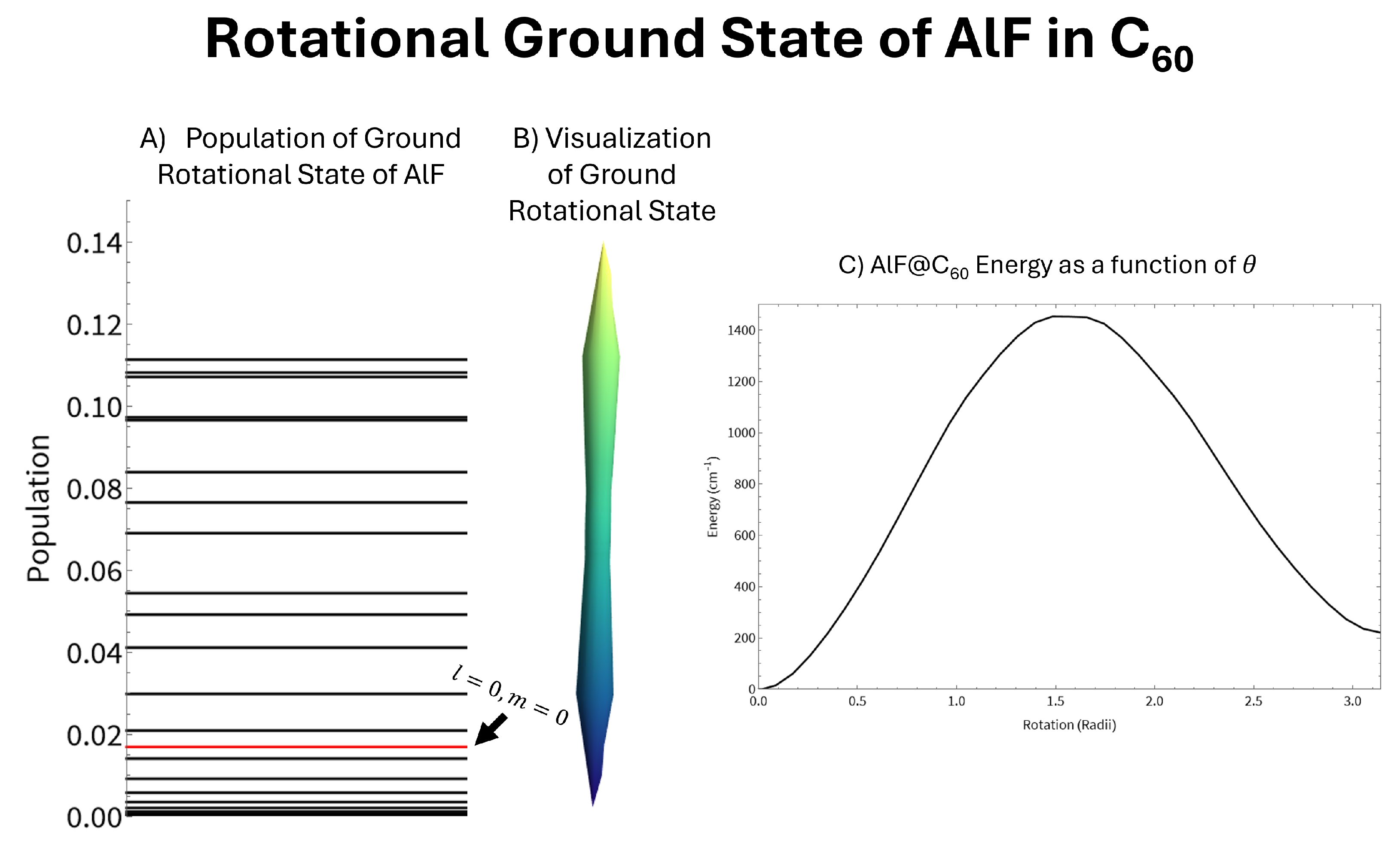

Assuming the internal molecules are rigid rotors we can calculate the changes to the rotational states caused by the interaction with the fullerene cage. These results for N

2@C

60 are shown in

Figure 3. Due to the symmetry of N

2, the potential is symmetric around a 90

∘ rotation. This results in the molecule being strongly aligned but not very strongly oriented. A strong alignment corresponds to high populations in states with even values of

l as alignment is calculated as:

. Since the potential is relatively weak, the ground state is mostly comprised of the lowest lying even

l state, which is the

state. Therefore, the ground state appears as a slightly altered version of the

spherical harmonic, shown in panel B of

Figure 3. This weak mixing means the new ground state can be described accurately accounting for only a few unperturbed rotational states. Our calculations of the perturbed rotational ground state accounted for eleven unperturbed rotational states. However, sufficient convergence was found by accounting for as little as five states, as the populations of the higher

l values were found to rapidly approach zero. The alignment of the new ground state was calculated to be 0.82 as opposed to the orientation (

) of the new ground state which was calculated to be 0.0053. The small orientation should come as no surprise since the N

2 molecule is homonuclear.

The potential for AlF as it rotates inside the C

60 molecule, shown in panel C of

Figure 4, has a few important differences from N

2. The potential for AlF is symmetric around a 180

∘ rotation. The energy at 180

∘ is higher than the energy at the optimal geometry since the Al-C and F-C interactions are very different. This forces the AlF molecule to be strongly oriented and strongly aligned. The alignment of the new ground state was calculated to be 0.98 and the orientation of the new ground state which was calculated to be 0.99. The increased alignment is due to the increased strength of the potential. Compared to N

2@C

60, the energy as a function of rotation is about ten times stronger for AlF@C

60. This results in the perturbed rotational ground state becoming a heavy mix of a wide variety of unperturbed rotational states. To calculate the new rotational ground state we needed to account for approximately 27 unperturbed states in order to find sufficient convergence, compared to the five needed for N

2. Since the molecule is both aligned and orientated, there is no strong preference for states with an even value of

l like what was seen for N

2. The strong alignment causes the visualization of the new ground state, shown in panel B of

Figure 4, to be very long and thin. The many unperturbed states represented within the new ground state causes the visualization to not closely resemble any one spherical harmonic.

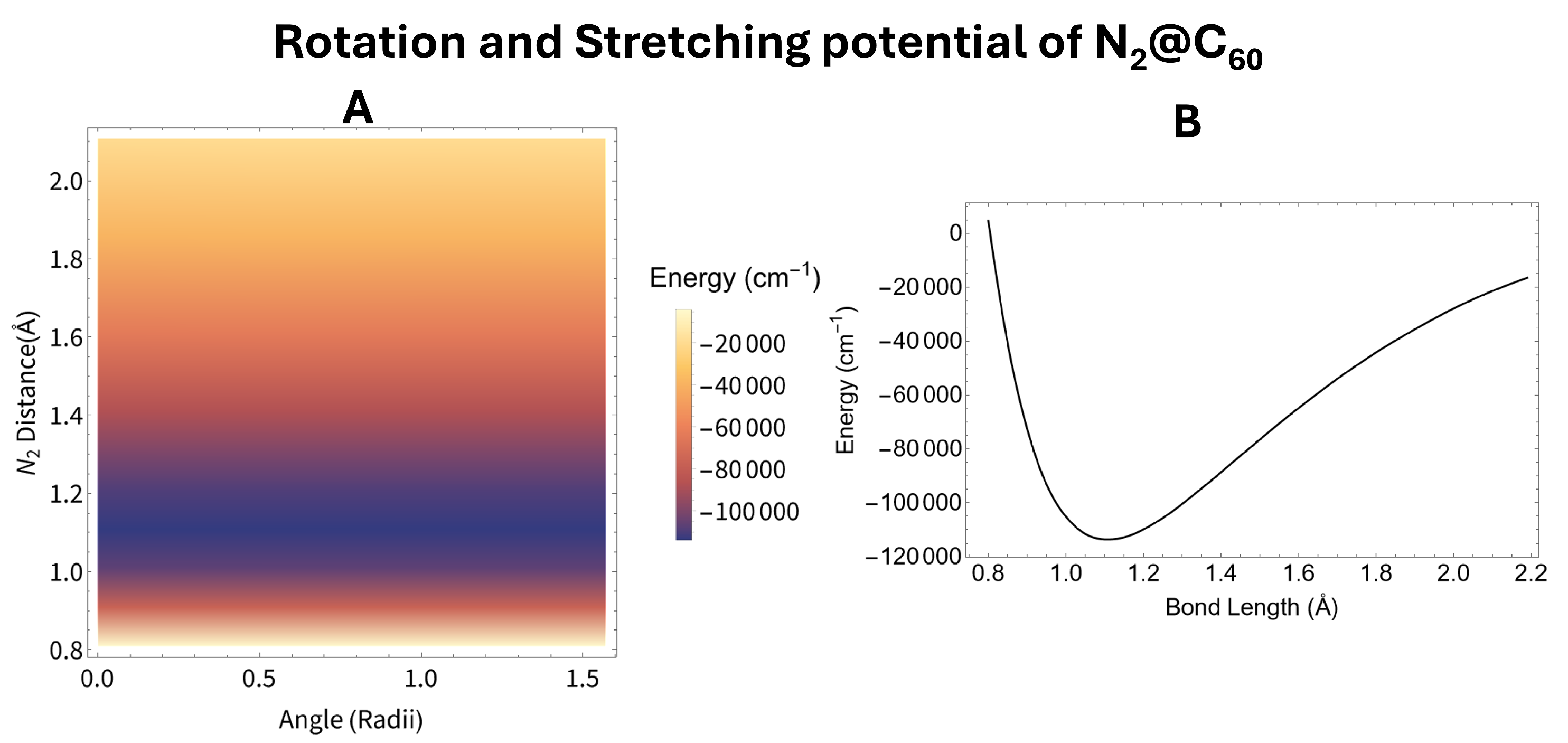

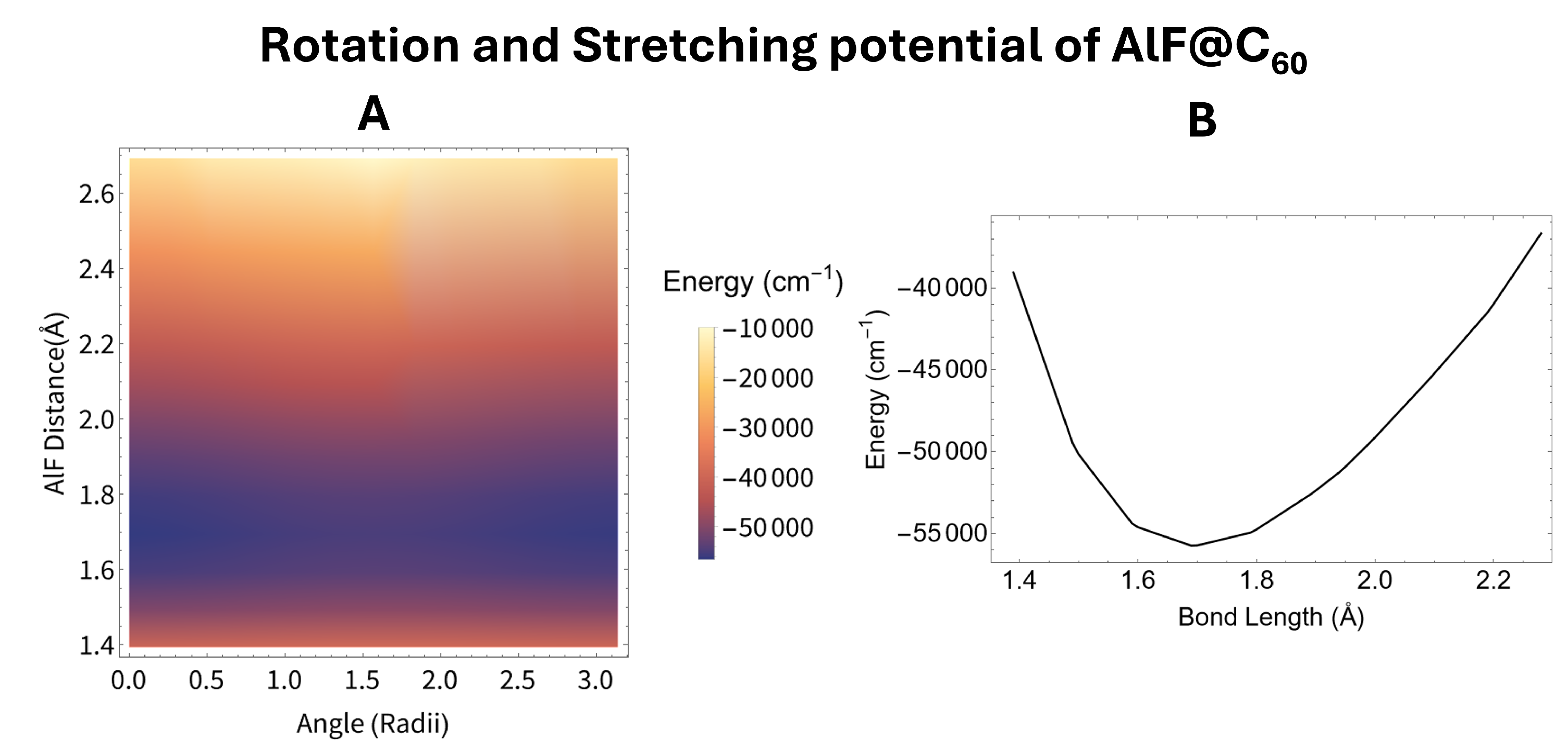

The potential as a function of both rotation and stretching is shown in panel A of

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 for N

2@C

60 and AlF@C

60 respectively. On both of these plots the energy appears to change little as the rotation angle changes. Since the energy as a function of rotation is much weaker than the energy as a function of vibration for both AlF and N

2 within carbon cages, we can average out the energy as a function of rotation leaving only the energy as a function of bond length. We average the full potential (

) assuming the molecule is in the unperturbed rotational ground state in both cases. Panel B of

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 shows the rotationally averaged potential (

) for N

2@C

60 and AlF@C

60 respectively.

The rotationally averaged potential (

) for the two endofullerenes studied was then fit to a morse potential. This fit allows us to calculate the vibrational harmonic frequency, the first anharmonic correction, the rotational constant and the first correction to the rotational constant using the equations given in

Section 2. All of these constants are shown in

Table 1. All of these values are very similar to there free molecule counter part, also given in

Table 1. Some of these constants have error bars due to the imperfect fit of the rotationally averaged potential to a morse potential. This means we do not predict any error in the equilibrium distances

as these values come directly from the DFT calculations, and we do not predict any error for the rotational constants as these depend only on the equilibrium distance.

Using the geometry calculated previously, we calculated the dipole moment of AlF@C

60 using the B3LYP functional and the Def2TZpp basis set with GD3BJ dispersion. This method found that AlF@C

60 had a dipole moment of 1.63 Debye. Using the same quantum chemistry methods free AlF’s dipole moment is determined to be 1.51 Debye. Free AlF’s dipole moment has been experimentally determined to be 1.530 Debye [

21]. These methods predict that the cage enhances the dipole moment of the internal molecule.

4. Discussion

We find that the change in energy as the internal molecules stretches is significantly greater than the change in energy as the internal molecule rotates for both endofullerenes studied. Panel C of

Figure 4 shows that the energy as a function of rotation for AlF inside of C

60 is on the order of

cm

−1. Compared to the energy as a function of stretching, shown in panel B of

Figure 6, which is on the order of

cm

−1. This energy difference is even bigger in the case of N

2@C

60 due to the tight bond between the two nitrogen molecules. This difference in energy allows for the rotational and vibrational degrees of freedom to be treated separately, as we have done, without significant loss in accuracy.

In the spectroscopic constants we calculated, shown in

Table 1, the only error accounted for is the error due to the fit of the potential to a morse potential. This error is general pretty small since the rotationally averaged potential (

) fits very well to a morse function (both R-squared values are over 0.99). Errors due to the level of theory used or the limited size of the basis set used are not accounted for and are likely the most significant sources of error.

For the equilibrium distances, the AlF molecule is predicted to stretch slightly due to the cage when compared to N

2. This might be expected due to the larger bond length making the nuclei closer to the cage and due to the dipole moment causing stronger long range reactions. However, using the same methods the equilibrium distance of free AlF is calculated to be 1.74 Å. Since this is larger than the experimentally determined bond length of free AlF (1.65 Å) [

23] and larger than the bond length predicted for AlF inside of a fullerene (1.69 Å), these disagreements are likely the result of uncertainties in our calculations. The change in bond length for N

2 is even smaller and is therefore even more likely to be insignificant.

The dipole moment predicted using the Def2TZVpp basis set for AlF@C

60 is roughly equivalent to the experimentally determined dipole moment for free AlF. Using the same quantum chemistry methods, free AlF is predicted to have a slightly smaller dipole moment, one that is even closer to the experimentally determined value of free AlF’s dipole moment. This is a surprise as results for HF@C

60 experimentally indicate that the fullerene cage suppress the dipole moment of the internal HF molecule by as much as 75% [

26]. Our results suggest that the dipole moment is unchanged or even enhanced by the fullerene. It is possible that dipole suppression is unique to HF as polarizabilities have been shown to be different for different types of internal molecules [

27].There is also the possibility this is a failing of the quantum chemistry methods implemented. This could also be a result of temperature which is not accounted for in our study but is accounted for in the study of HF@C

60. This contradiction warrants future studying.

Overall our methods have not indicated that the rotational and vibrational spectroscopic values change significantly when a molecule is placed inside of a fullerene cage. The cage does appear to cause strong alignment in homonuclear and heteronuclear molecules, as shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. Strong orientation is seen in heteronuclear molecules only, as shown in

Figure 4. N

2 is an extremely tightly bound molecule with a small bond length so it is expected that these effects would be less significant. However, even in this case the ground rotational state is significantly different from free N

2’s ground rotational state and more closely resembles free N

2’s second excited rotational state. Of course when introducing a molecule with a much larger bond length and a dipole moment, these effects become much greater.

5. Conclusions

Our methods predict that the internal molecule of a endofullerene is not significantly altered by the interaction with the carbon cage. We report no significant changes to the equilibrium distance, the rotational constant, the first correction to the rotational constant, the harmonic frequency and the first anharmonic correction. This agreement does provide some evidence that our approach is accurate. While the properties of the internal molecule do seem to remain unchanged, the molecule does appear to be strongly aligned with the C

60 cage. In the case of a heteronuclear internal molecule, the molecule is predicted to have both strong alignment and strong orientation with the fullerene. We do not see significant suppression of AlFs dipole when inside the C

60 cage, unlike what has been measured with HF@C

60 [

26]. Better understanding of this disagreement is a topic for future work along with calculations of a full potential surface for N

2 or AlF inside of a fullerene.

Based on this work we propose future studies of alignment within a fullerene cage. Molecules aligned in helium droplets are shielded from external fields and can still be aligned using a fast off-resonance laser pulse [

15,

16,

17]. It is likely that molecules in a fullerene cage can also have their alignment controlled using a laser pulse. The fullerene cage will shield the internal molecule, resulting in long coherence times even when the studies are preformed in a solution. This could improve the accuracy of alignment studies which are typically used to measure the rotational constant. It also has potential applications to quantum computation.