Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Dimensional Frameworks for Understanding Comorbidity

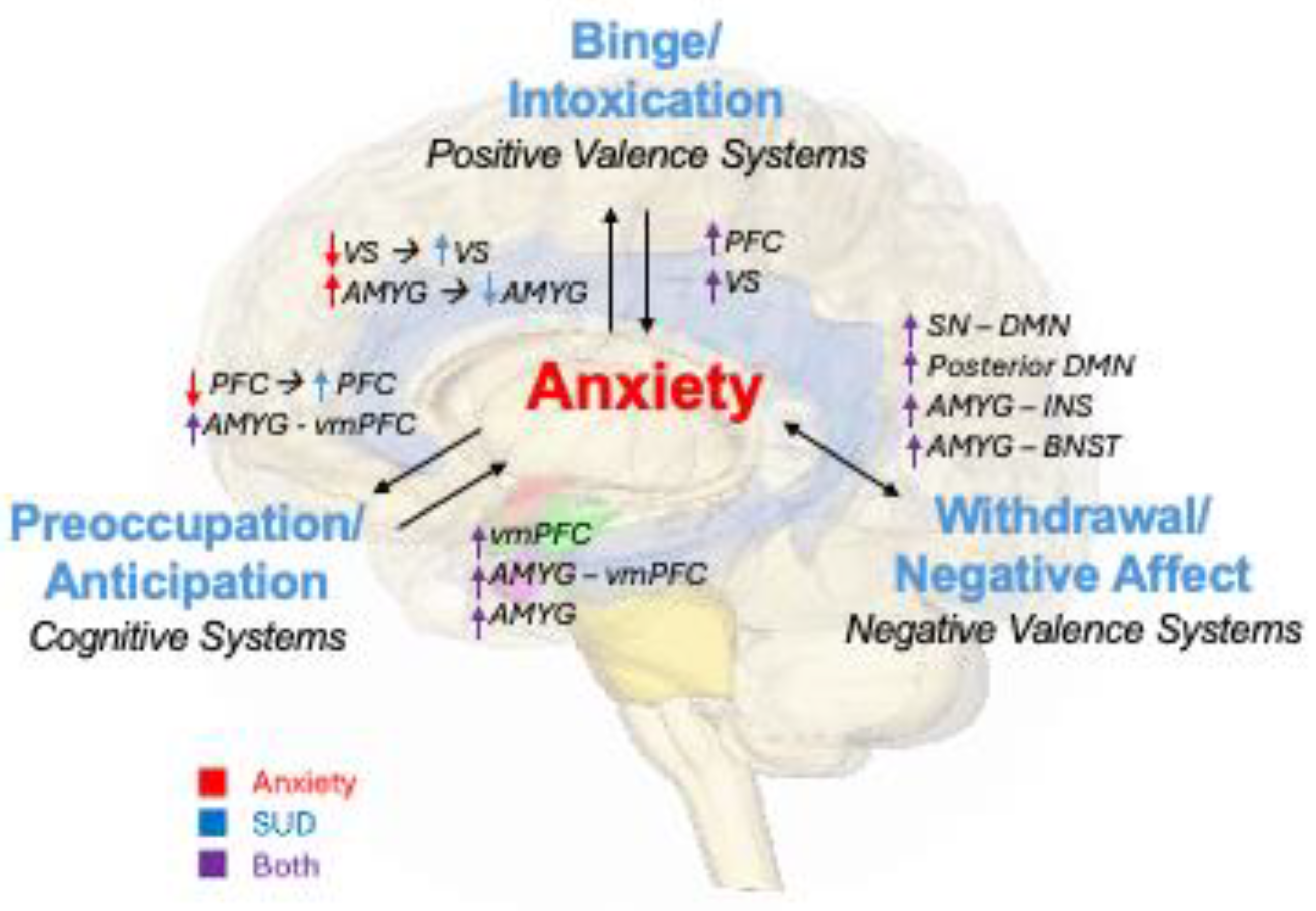

2.1. Positive Valence Systems–Binge/Intoxication

2.1.1. Neurobiology

2.1.2. Neuroimaging Findings: Anxiety → Binge/Intoxication

2.1.3. Neuroimaging Findings: Binge/Intoxication → Anxiety

2.2. Negative Valence Systems - Withdrawal/Negative Affect

2.2.1. Neurobiology

2.2.2. Neuroimaging Findings: Withdrawal/Negative Affect ⟷ Anxiety

2.3. Cognitive Systems - Preoccupation/Anticipation

2.3.1. Neurobiology

2.3.2. Neuroimaging Findings: Anxiety → Preoccupation/Anticipation

2.3.3. Neuroimaging Findings: Preoccupation/Anticipation → Anxiety

3. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Volkow, N.D.; Blanco, C. Substance Use Disorders: A Comprehensive Update of Classification, Epidemiology, Neurobiology, Clinical Aspects, Treatment and Prevention. World Psychiatry, 2023, 22, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, S.N.; Clauss, J.A.; Blackford, J.U. The Human BNST: Functional Role in Anxiety and Addiction. Neuropsychopharmacol, 2016, 41, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüthi, A.; Lüscher, C. Pathological Circuit Function Underlying Addiction and Anxiety Disorders. Nat Neurosci, 2014, 17, 1635–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colasanti, A.; Rabiner, E.; Lingford-Hughes, A.; Nutt, D. Opioids and Anxiety. J Psychopharmacol, 2011, 25, 1415–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorspan, F.; Mehtelli, W.; Dupuy, G.; Bloch, V.; Lépine, J.-P. Anxiety and Substance Use Disorders: Co-Occurrence and Clinical Issues. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 2015, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quello, S.B.; Brady, K.T.; Sonne, S.C. Mood Disorders and Substance Use Disorder: A Complex Comorbidity. Science & Practice Perspectives, 2005, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aston-Jones, G.; Harris, G.C. Brain Substrates for Increased Drug Seeking during Protracted Withdrawal. Neuropharmacology, 2004, 47, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulteis, G.; Koob, G.F. Reinforcement Processes in Opiate Addiction: A Homeostatic Model. Neurochem Res, 1996, 21, 1437–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Self, D.W.; Nestler, E.J. Relapse to Drug-Seeking: Neural and Molecular Mechanisms. Drug Alcohol Depend, 1998, 51, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. Role of Self-Medication in the Development of Comorbid Anxiety and Substance Use Disorders: A Longitudinal Investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 2011, 68, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacek, L.R.; Storr, C.L.; Mojtabai, R.; Green, K.M.; La Flair, L.N.; Alvanzo, A.A.H.; Cullen, B.A.; Crum, R.M. Comorbid Alcohol Dependence and Anxiety Disorders: A National Survey. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 2013, 9, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaney, D.; Jackson, A.K.; Toy, O.; Fitzgerald, A.; Piechniczek-Buczek, J. Substance-Induced Anxiety and Co-Occurring Anxiety Disorders. In Substance Use and the Acute Psychiatric Patient: Emergency Management; Donovan, A.L., Bird, S.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- María-Ríos, C.E.; Morrow, J.D. Mechanisms of Shared Vulnerability to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Substance Use Disorders. Front. Behav. Neurosci., 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquenie, L.A.; Schadé, A.; van Balkom, A.J.L.M.; Comijs, H.C.; de Graaf, R.; Vollebergh, W.; van Dyck, R.; van den Brink, W. Origin of the Comorbidity of Anxiety Disorders and Alcohol Dependence: Findings of a General Population Study. European Addiction Research, 2006, 13, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, F.; Carretta, D.; Clerici, M.; Carrà, G. Comorbid Anxiety and Alcohol or Substance Use Disorders: An Overview. In Textbook of Addiction Treatment: International Perspectives; el-Guebaly, N., Carrà, G., Galanter, M., Eds.; Springer Milan: Milano, 2015; pp. 1971–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudys, J.W.; Traynor, J.M.; Rodrigo, A.H.; Carcone, D.; Ruocco, A.C. The NIMH Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) Initiative and Its Implications for Research on Personality Disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 2019, 21, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.E.; Pacheco, J.; Sanislow, C.A. Applying Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) Dimensions to Psychosis. In Psychotic disorders: Comprehensive conceptualization and treatments; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, US, 2021; pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woody, M.L.; Gibb, B.E. Integrating NIMH Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) into Depression Research. Curr Opin Psychol, 2015, 4, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litten, R.Z.; Ryan, M.L.; Falk, D.E.; Reilly, M.; Fertig, J.B.; Koob, G.F. Heterogeneity of Alcohol Use Disorder: Understanding Mechanisms to Advance Personalized Treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2015, 39, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F.; Volkow, N.D. Neurobiology of Addiction: A Neurocircuitry Analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2016, 3, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craske, M.G.; Meuret, A.E.; Ritz, T.; Treanor, M.; Dour, H.J. Treatment for Anhedonia: A Neuroscience Driven Approach: 2015 ADAA Scientific Research Symposium: Treatment for Anhedonia. Depress Anxiety, 2016, 33, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, D.G.; Rosso, I.M.; Pechtel, P.; Killgore, W.D.S.; Rauch, S.L.; Pizzagalli, D.A. PERIL AND PLEASURE: AN RDOC-INSPIRED EXAMINATION OF THREAT RESPONSES AND REWARD PROCESSING IN ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION: Neighborhood Characteristics and Mental Health. Depress Anxiety, 2014, 31, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.T.; Hoffman, S.N.; Khan, A.J. Anhedonia in Anxiety Disorders. In Anhedonia: Preclinical, Translational, and Clinical Integration; Pizzagalli, D.A., Ed.; Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; Volume 58, pp. 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, T.J.; Berg, H.; Touthang, J.; Akeman, E.; Cannon, M.J.; Santiago, J.; Cosgrove, K.T.; Clausen, A.N.; Kirlic, N.; Smith, R.; Craske, M.G.; Abelson, J.L.; Paulus, M.P.; Aupperle, R.L. Striatal Reactivity during Emotion and Reward Relates to Approach-Avoidance Conflict Behaviour and Is Altered in Adults with Anxiety or Depression. J Psychiatry Neurosci, 2022, 47, E311–E322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.P.; Book, S.W. Anxiety and Substance Use Disorders: A Review. Psychiatr Times, 2008, 25, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwako, L.E.; Momenan, R.; Litten, R.Z.; Koob, G.F.; Goldman, D. Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment: A Neuroscience-Based Framework for Addictive Disorders. Biol Psychiatry, 2016, 80, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, A.A. The Tonic/Phasic Model of Dopamine System Regulation and Its Implications for Understanding Alcohol and Psychostimulant Craving. Addiction, 2000, 95, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, R.A. Roles for Nigrostriatal—Not Just Mesocorticolimbic—Dopamine in Reward and Addiction. Trends in Neurosciences, 2009, 32, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Volkow, N.D. Brain Default-Mode Network Dysfunction in Addiction. Neuroimage, 2019, 200, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F.; Volkow, N.D. Neurocircuitry of Addiction. Neuropsychopharmacol, 2010, 35, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.J.F.; Robinson, T.E.; Berridge, K.C. Incentive Salience and the Transition to Addiction. In Biological Research on Addiction; Elsevier, 2013; pp 391–399. [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Michaelides, M.; Baler, R. The Neuroscience of Drug Reward and Addiction. Physiological Reviews, 2019, 99, 2115–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellberg, S.N.; Russell, T.I.; Robinson, M.J.F. Cued for Risk: Evidence for an Incentive Sensitization Framework to Explain the Interplay between Stress and Anxiety, Substance Abuse, and Reward Uncertainty in Disordered Gambling Behavior. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci, 2019, 19, 737–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehme, S.; Ritter, V.; Tefikow, S.; Stangier, U.; Strauss, B.; Miltner, W.H.R.; Straube, T. Brain Activation during Anticipatory Anxiety in Social Anxiety Disorder. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci, 2014, 9, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sripada, C.; Angstadt, M.; Liberzon, I.; McCabe, K.; Phan, K.L. Aberrant Reward Center Response to Partner Reputation during a Social Exchange Game in Generalized Social Phobia. Depress Anxiety, 2013, 30, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, J.M.; Ramchandani, V.A.; Davis, M.B.; Bjork, J.M.; Hommer, D.W. Why We like to Drink: A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study of the Rewarding and Anxiolytic Effects of Alcohol. J Neurosci, 2008, 28, 4583–4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkow, N.D.; Tomasi, D.; Wang, G.-J.; Logan, J.; Alexoff, D.L.; Jayne, M.; Fowler, J.S.; Wong, C.; Yin, P.; Du, C. Stimulant-Induced Dopamine Increases Are Markedly Blunted in Active Cocaine Abusers. Mol Psychiatry, 2014, 19, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.-J.; Telang, F.; Fowler, J.S.; Logan, J.; Childress, A.-R.; Jayne, M.; Ma, Y.; Wong, C. Dopamine Increases in Striatum Do Not Elicit Craving in Cocaine Abusers Unless They Are Coupled with Cocaine Cues. NeuroImage, 2008, 39, 1266–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberzon, I.; Duval, E.; Javanbakht, A. Neural Circuits in Anxiety and Stress Disorders: A Focused Review. TCRM, 2015, 115. [CrossRef]

- Shin, L.M.; Liberzon, I. The Neurocircuitry of Fear, Stress, and Anxiety Disorders. Neuropsychopharmacol, 2010, 35, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, J.; Kaplan, C.M.; Smith, J.F.; Bradford, D.E.; Fox, A.S.; Curtin, J.J.; Shackman, A.J. Acute Alcohol Administration Dampens Central Extended Amygdala Reactivity. Sci Rep, 2018, 8, 16702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sripada, C.S.; Angstadt, M.; McNamara, P.; King, A.C.; Phan, K.L. Effects of Alcohol on Brain Responses to Social Signals of Threat in Humans. NeuroImage, 2011, 55, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, D.M.; Gonzales, B.J.; Citri, A. Dorsal Striatal Circuits for Habits, Compulsions and Addictions. Front. Syst. Neurosci., 2019, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.-J.; Telang, F.; Fowler, J.S.; Logan, J.; Childress, A.-R.; Jayne, M.; Ma, Y.; Wong, C. Cocaine Cues and Dopamine in Dorsal Striatum: Mechanism of Craving in Cocaine Addiction. Journal of Neuroscience, 2006, 26, 6583–6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muskens, J.B.; Schellekens, A.F.A.; De Leeuw, F.E.; Tendolkar, I.; Hepark, S. Damage in the Dorsal Striatum Alleviates Addictive Behavior. General Hospital Psychiatry, 2012, 34, 702.e9–702.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olney, J.J.; Warlow, S.M.; Naffziger, E.E.; Berridge, K.C. Current Perspectives on Incentive Salience and Applications to Clinical Disorders. Curr Opin Behav Sci, 2018, 22, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolomeo, S.; Yaple, Z.A.; Yu, R. Neural Representation of Prediction Error Signals in Substance Users. Addiction Biology, 2021, 26, e12976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, W. Dopamine Reward Prediction Error Coding. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 2016, 18, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papalini, S.; Beckers, T.; Vervliet, B. Dopamine: From Prediction Error to Psychotherapy. Transl Psychiatry, 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.P.I.; Voegler, R.; Peterburs, J.; Hofmann, D.; Bellebaum, C.; Straube, T. Reward Prediction Error Signaling during Reinforcement Learning in Social Anxiety Disorder Is Altered by Social Observation. bioRxiv October 30, 2019, p 821512. [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F. Negative Reinforcement in Drug Addiction: The Darkness Within. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 2013, 23, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, M.E. Withdrawal: Expanding a Key Addiction Construct. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2015, 17, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F. Drug Addiction: Hyperkatifeia/Negative Reinforcement as a Framework for Medications Development. Pharmacol Rev, 2021, 73, 163–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, A.H.; Desai, R.A.; McKee, S.A. Nicotine Withdrawal in U.S. Smokers with Current Mood, Anxiety, Alcohol Use, and Substance Use Disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2010, 108, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweben, J.E.; Cohen, J.B.; Christian, D.; Galloway, G.P.; Salinardi, M.; Parent, D.; Iguchi, M.; Project, M.T. Psychiatric Symptoms in Methamphetamine Users. The American Journal on Addictions, 2004, 13, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellekens, A.F.A.; Jong, C.A.J. de; Buitelaar, J.K.; Verkes, R.J. Co-Morbid Anxiety Disorders Predict Early Relapse after Inpatient Alcohol Treatment. European Psychiatry, 2015, 30, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, O.; Ghozland, S.; Azar, M.R.; Cottone, P.; Zorrilla, E.P.; Parsons, L.H.; O’Dell, L.E.; Richardson, H.N.; Koob, G.F. CRF–CRF1 System Activation Mediates Withdrawal-Induced Increases in Nicotine Self-Administration in Nicotine-Dependent Rats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2007, 104, 17198–17203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantsch, J.R. Corticotropin Releasing Factor and Drug Seeking in Substance Use Disorders: Preclinical Evidence and Translational Limitations. Addiction Neuroscience, 2022, 4, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcinkiewcz, C.A.; Prado, M.M.; Isaac, S.K.; Marshall, A.; Rylkova, D.; Bruijnzeel, A.W. Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Within the Central Nucleus of the Amygdala and the Nucleus Accumbens Shell Mediates the Negative Affective State of Nicotine Withdrawal in Rats. Neuropsychopharmacol, 2009, 34, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorrilla, E.P.; Logrip, M.L.; Koob, G.F. Corticotropin Releasing Factor: A Key Role in the Neurobiology of Addiction. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 2014, 35, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delfs, J.M.; Zhu, Y.; Druhan, J.P.; Aston-Jones, G. Noradrenaline in the Ventral Forebrain Is Critical for Opiate Withdrawal-Induced Aversion. Nature, 2000, 403, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haller, J. Anxiety Modulation by Cannabinoids—The Role of Stress Responses and Coping. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023, 24, 15777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, L.H.; Hurd, Y.L. Endocannabinoid Signaling in Reward and Addiction. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 2015, 16, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruehle, S.; Rey, A.A.; Remmers, F.; Lutz, B. The Endocannabinoid System in Anxiety, Fear Memory and Habituation. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 2012, 26, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Whalen, P.J. The Amygdala: Vigilance and Emotion. Mol Psychiatry, 2001, 6, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, J.; Verrico, C.D.; Cay, M.; Kodele, S.; Yammine, L.; Koob, G.F.; Schreiber, R. Neurocircuitry Basis of the Opioid Use Disorder–Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Comorbid State: Conceptual Analyses Using a Dimensional Framework. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2022, 9, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, C.; Gu, H.; Loughead, J.; Ruparel, K.; Yang, Y.; Stein, E.A. Large-Scale Brain Network Coupling Predicts Acute Nicotine Abstinence Effects on Craving and Cognitive Function. JAMA Psychiatry, 2014, 71, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Daly, O.G.; Trick, L.; Scaife, J.; Marshall, J.; Ball, D.; Phillips, M.L.; Williams, S.S.C.; Stephens, D.N.; Duka, T. Withdrawal-Associated Increases and Decreases in Functional Neural Connectivity Associated with Altered Emotional Regulation in Alcoholism. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2012, 37, 2267–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Shen, F.; Sun, X.; Zou, T.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Deng, C.; Duan, X.; He, Z.; Yang, M.; Li, Z.; Chen, H. Dissociable Salience and Default Mode Network Modulation in Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Connectome-Wide Association Study. Cerebral Cortex, 2023, 33, 6354–6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresh, E.L.; Allen, J.P.; Coan, J.A. Increased Default Mode Network Activity in Socially Anxious Individuals during Reward Processing. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord, 2014, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viard, A.; Mutlu, J.; Chanraud, S.; Guenolé, F.; Egler, P.-J.; Gérardin, P.; Baleyte, J.-M.; Dayan, J.; Eustache, F.; Guillery-Girard, B. Altered Default Mode Network Connectivity in Adolescents with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. NeuroImage : Clinical, 2019, 22, 101731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Guo, R.-J.; Shi, H.-W. Altered Default Mode Network and Salience Network Functional Connectivity in Patients with Generalized Anxiety Disorders: An ICA-Based Resting-State fMRI Study. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2020, 2020, 4048916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Guell, X.; Hubbard, N.A.; Siless, V.; Frosch, I.R.; Goncalves, M.; Lo, N.; Nair, A.; Ghosh, S.S.; Hofmann, S.G.; Auerbach, R.P.; Pizzagalli, D.A.; Yendiki, A.; Gabrieli, J.D.E.; Whitfield-Gabrieli, S.; Anteraper, S.A. Functional Alterations in Cerebellar Functional Connectivity in Anxiety Disorders. Cerebellum, 2021, 20, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Duan, M.; He, H. Deficient Salience and Default Mode Functional Integration in High Worry-Proneness Subject: A Connectome-Wide Association Study. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, M.T.; McHugh, M.; Pariyadath, V.; Stein, E.A. Resting State Functional Connectivity in Addiction: Lessons Learned and a Road Ahead. NeuroImage, 2012, 62, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, M.T.; Stein, E.A. Functional Neurocircuits and Neuroimaging Biomarkers of Tobacco Use Disorder. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 2018, 24, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, V.; Hänggi, J.; Langer, N.; Jäncke, L. Resting-State Functional and Structural Connectivity Within an Insula–Amygdala Route Specifically Index State and Trait Anxiety. Biological Psychiatry, 2013, 73, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, N.H.; Bechara, A. The Insula and Drug Addiction: An Interoceptive View of Pleasure, Urges, and Decision-Making. Brain Struct Funct, 2010, 214, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkin, A.; Wager, T.D. Functional Neuroimaging of Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Processing in PTSD, Social Anxiety Disorder, and Specific Phobia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 2007, 164, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinak, C.A.; Angstadt, M.; Welsh, R.C.; Kenndy, A.E.; Lyubkin, M.; Martis, B.; Phan, K.L. Altered Amygdala Resting-State Functional Connectivity in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Front Psychiatry, 2011, 2, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.K.; Fudge, J.L.; Kelly, C.; Perry, J.S.A.; Daniele, T.; Carlisi, C.; Benson, B.; Castellanos, F.X.; Milham, M.P.; Pine, D.S.; Ernst, M. Intrinsic Functional Connectivity of Amygdala-Based Networks in Adolescent Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2013, 52, 290–299.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.B.; Simmons, A.N.; Feinstein, J.S.; Paulus, M.P. Increased Amygdala and Insula Activation during Emotion Processing in Anxiety-Prone Subjects. Am J Psychiatry, 2007, 164, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.; Fogelman, N.; Wemm, S.; Angarita, G.; Seo, D.; Hermes, G. Alcohol Withdrawal Symptoms Predict Corticostriatal Dysfunction That Is Reversed by Prazosin Treatment in Alcohol Use Disorder. Addiction Biology, 2022, 27, e13116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.-H.; Wang, P.-J.; Li, C.-B.; Hu, Z.-H.; Xi, Q.; Wu, W.-Y.; Tang, X.-W. Altered Default Mode Network Activity in Patient with Anxiety Disorders: An fMRI Study. European Journal of Radiology, 2007, 63, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, J.F.; Fernandesl, S.V.; Soares, J.M.; Maia, L.; Gonçalves, Ó.F.; Sampaio, A. Default Mode Network Dissociation in Depressive and Anxiety States. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 2016, 10, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F.; Moal, M.L. Addiction and the Brain Antireward System. Annual Review of Psychology 2008, 59, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.; Juliano, A.; Owens, M.; Cupertino, R.B.; Mackey, S.; Hermosillo, R.; Miranda-Dominguez, O.; Conan, G.; Ahmed, M.; Fair, D.A.; Graham, A.M.; Goode, N.J.; Kandjoze, U.P.; Potter, A.; Garavan, H.; Albaugh, M.D. Amygdala Connectivity Is Associated with Withdrawn/Depressed Behavior in a Large Sample of Children from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study®. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 2024, 344, 111877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Liu, B.; Yang, B.; Dang, W.; Xie, H.; Lui, S.; Qiu, C.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, W. Dysfunction of Default Mode Network Characterizes Generalized Anxiety Disorder Relative to Social Anxiety Disorder and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. J Affect Disord, 2023, 334, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Qin, W.; Yu, C.; Jiang, T. The Structural Connectivity Pattern of the Default Mode Network and Its Association with Memory and Anxiety. Front. Neuroanat., 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Erritzoe, D.; Williams, T.; Stone, J.M.; Reed, L.J.; Colasanti, A.; Tyacke, R.J.; Leech, R.; Malizia, A.L.; Murphy, K.; Hobden, P.; Evans, J.; Feilding, A.; Wise, R.G.; Nutt, D.J. Neural Correlates of the Psychedelic State as Determined by fMRI Studies with Psilocybin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2012, 109, 2138–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, S.J.; Goldstein, R.Z. Impaired Self-Awareness in Human Addiction: Deficient Attribution of Personal Relevance. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2014, 18, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Morales, M. The Brain on Drugs: From Reward to Addiction. Cell, 2015, 162, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killingsworth, M.A.; Gilbert, D.T. A Wandering Mind Is an Unhappy Mind. Science, 2010, 330, 932–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yuan, H.; Lei, X. Activation and Connectivity within the Default Mode Network Contribute Independently to Future-Oriented Thought. Sci Rep, 2016, 6, 21001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Z.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Yan, X.; Ye, J.; Li, L.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y. Disrupted Default Mode Network and Basal Craving in Male Heroin-Dependent Individuals: A Resting-State fMRI Study. J Clin Psychiatry, 2016, 77, 4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Cortes, C.R.; Mathur, K.; Tomasi, D.; Momenan, R. Model-Free Functional Connectivity and Impulsivity Correlates of Alcohol Dependence: A Resting-State Study. Addiction Biology, 2017, 22, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F.; Volkow, N.D. Neurobiology of Addiction: A Neurocircuitry Analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2016, 3, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Walker, D.L.; Miles, L.; Grillon, C. Phasic vs. Sustained Fear in Rats and Humans: Role of the Extended Amygdala in Fear vs. Anxiety. Neuropsychopharmacol, 2010, 35, 105–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flook, E.A.; Feola, B.; Benningfield, M.M.; Silveri, M.M.; Winder, D.G.; Blackford, J.U. Alterations in BNST Intrinsic Functional Connectivity in Early Abstinence from Alcohol Use Disorder. Alcohol Alcohol, 2023, 58, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, R.P.; Chen, G.; Bodurka, J.; Kaplan, R.; Grillon, C. Phasic and Sustained Fear in Humans Elicits Distinct Patterns of Brain Activity. Neuroimage, 2011, 55, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.M.; Padmala, S.; Pessoa, L. Impact of State Anxiety on the Interaction between Threat Monitoring and Cognition. NeuroImage, 2012, 59, 1912–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klumpers, F.; Kroes, M.C.; Heitland, I.; Everaerd, D.; Akkermans, S.E.A.; Oosting, R.S.; van Wingen, G.; Franke, B.; Kenemans, J.L.; Fernández, G.; Baas, J.M.P. Dorsomedial Prefrontal Cortex Mediates the Impact of Serotonin Transporter Linked Polymorphic Region Genotype on Anticipatory Threat Reactions. Biological Psychiatry, 2015, 78, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMenamin, B.W.; Langeslag, S.J.E.; Sirbu, M.; Padmala, S.; Pessoa, L. Network Organization Unfolds over Time during Periods of Anxious Anticipation. J Neurosci, 2014, 34, 11261–11273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, P.R.; Tarter, R.E. Executive Cognitive Functioning and Risk for Substance Abuse. Psychol Sci, 1999, 10, 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Spoon, J.; Kahn, R.E.; Lauharatanahirun, N.; Deater-Deckard, K.; Bickel, W.K.; Chiu, P.H.; King-Casas, B. Executive Functioning and Substance Use in Adolescence: Neurobiological and Behavioral Perspectives. Neuropsychologia, 2017, 100, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.E.; Friedman, N.P.; Miyake, A.; Willcutt, E.G.; Corley, R.P.; Haberstick, B.C.; Hewitt, J.K. Behavioral Disinhibition: Liability for Externalizing Spectrum Disorders and Its Genetic and Environmental Relation to Response Inhibition across Adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 2009, 118, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGirolamo, G.J.; Smelson, D.; Guevremont, N. Cue-Induced Craving in Patients with Cocaine Use Disorder Predicts Cognitive Control Deficits toward Cocaine Cues. Addictive Behaviors, 2015, 47, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Li, S.; Yang, L.; Zheng, M. Reduced Response Inhibition after Exposure to Drug-Related Cues in Male Heroin Abstainers. Psychopharmacology, 2020, 237, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatseas, M.; Serre, F.; Swendsen, J.; Auriacombe, M. Effects of Anxiety and Mood Disorders on Craving and Substance Use among Patients with Substance Use Disorder: An Ecological Momentary Assessment Study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2018, 187, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.; Fox, H.C.; Hong, K.A.; Hansen, J.; Tuit, K.; Kreek, M.J. Effects of Adrenal Sensitivity, Stress- and Cue-Induced Craving, and Anxiety on Subsequent Alcohol Relapse and Treatment Outcomes. Archives of General Psychiatry, 2011, 68, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, S.N. Corticostriatal Circuitry. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 2016, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamford, N.S.; Zhang, H.; Joyce, J.A.; Scarlis, C.A.; Hanan, W.; Wu, N.-P.; André, V.M.; Cohen, R.; Cepeda, C.; Levine, M.S.; Harleton, E.; Sulzer, D. Repeated Exposure to Methamphetamine Causes Long-Lasting Presynaptic Corticostriatal Depression That Is Renormalized with Drug Readministration. Neuron, 2008, 58, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Chen, B.T.; Hopf, F.W.; Bowers, M.S.; Bonci, A. Cocaine Self-Administration Selectively Abolishes LTD in the Core of the Nucleus Accumbens. Nat Neurosci, 2006, 9, 868–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussawi, K.; Pacchioni, A.; Moran, M.; Olive, M.F.; Gass, J.T.; Lavin, A.; Kalivas, P.W. N-Acetylcysteine Reverses Cocaine-Induced Metaplasticity. Nat Neurosci, 2009, 12, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRowe, S.D.; Myrick, H.; Hedden, S.; Mardikian, P.; Saladin, M.; McRae, A.; Brady, K.; Kalivas, P.W.; Malcolm, R. Is Cocaine Desire Reduced by N -Acetylcysteine? AJP, 2007, 164, 1115–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaguchi, T.; Goldman-Rakic, P.S. D1 Dopamine Receptors in Prefrontal Cortex: Involvement in Working Memory. Science, 1991, 251, 947–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaguchi, T.; Goldman-Rakic, P.S. The Role of D1-Dopamine Receptor in Working Memory: Local Injections of Dopamine Antagonists into the Prefrontal Cortex of Rhesus Monkeys Performing an Oculomotor Delayed-Response Task. J Neurophysiol, 1994, 71, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.V.; Goldman-Rakic, P.S. Modulation of Memory Fields by Dopamine D1 Receptors in Prefrontal Cortex. Nature, 1995, 376, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, M.V.; Miller, E.K. The Role of Prefrontal Dopamine D1 Receptors in the Neural Mechanisms of Associative Learning. Neuron, 2012, 74, 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, U.; Cramon, D.Y. von; Pollmann, S. D1- Versus D2-Receptor Modulation of Visuospatial Working Memory in Humans. The Journal of Neuroscience, 1998, 18, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verharen, J.P.H.; Adan, R.A.H.; Vanderschuren, L.J.M.J. Differential Contributions of Striatal Dopamine D1 and D2 Receptors to Component Processes of Value-Based Decision Making. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2019, 44, 2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala-Bayo, J.; Fiddian, L.; Nilsson, S.R.O.; Hervig, M.E.; McKenzie, C.; Mareschi, A.; Boulos, M.; Zhukovsky, P.; Nicholson, J.; Dalley, J.W.; Alsiö, J.; Robbins, T.W. Dorsal and Ventral Striatal Dopamine D1 and D2 Receptors Differentially Modulate Distinct Phases of Serial Visual Reversal Learning. Neuropsychopharmacol., 2020, 45, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares-Cunha, C.; Coimbra, B.; Sousa, N.; Rodrigues, A.J. Reappraising Striatal D1- and D2-Neurons in Reward and Aversion. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 2016, 68, 370–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, J.M.; Torregrossa, M.M.; Taylor, J.R. Bidirectional Modulation of Infralimbic Dopamine D1 and D2 Receptor Activity Regulates Flexible Reward Seeking. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 2013, 7, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, G.F.; Volkow, N.D. Neurocircuitry of Addiction. Neuropsychopharmacol, 2010, 35, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudriaan, A.E.; De Ruiter, M.B.; Van Den Brink, W.; Oosterlaan, J.; Veltman, D.J. Brain Activation Patterns Associated with Cue Reactivity and Craving in Abstinent Problem Gamblers, Heavy Smokers and Healthy Controls: An fMRI Study. Addiction Biology, 2010, 15, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, Z.; Fabbricatore, J.L.; McMains, J.T.; Worsdale, A.; Jones, E.C.; Wang, Y.; Sweet, L.H. Vaping and Smoking Cue Reactivity in Young Adult Non-Smoking Electronic Cigarette Users: A Functional Neuroimaging Study. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 2024, ntae257. [CrossRef]

- Schacht, J.P.; Anton, R.F.; Myrick, H. Functional Neuroimaging Studies of Alcohol Cue Reactivity: A Quantitative Meta-analysis and Systematic Review. Addiction Biology, 2013, 18, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehl, H.; Terrett, G.; Greenwood, L.-M.; Kowalczyk, M.; Thomson, H.; Poudel, G.; Manning, V.; Lorenzetti, V. Patterns of Brain Function Associated with Cannabis Cue-Reactivity in Regular Cannabis Users: A Systematic Review of fMRI Studies. Psychopharmacology, 2021, 238, 2709–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Moghaddam, B. Impact of Anxiety on Prefrontal Cortex Encoding of Cognitive Flexibility. Neuroscience, 2017, 345, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, S.J. Trait Anxiety and Impoverished Prefrontal Control of Attention. Nat Neurosci, 2009, 12, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijsterbosch, J.; Smith, S.; Bishop, S.J. Functional Connectivity under Anticipation of Shock: Correlates of Trait Anxious Affect versus Induced Anxiety. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 2015, 27, 1840–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makovac, E.; Mancini, M.; Fagioli, S.; Watson, D.R.; Meeten, F.; Rae, C.L.; Critchley, H.D.; Ottaviani, C. Network Abnormalities in Generalized Anxiety Pervade beyond the Amygdala-Pre-Frontal Cortex Circuit: Insights from Graph Theory. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 2018, 281, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vytal, K.E.; Overstreet, C.; Charney, D.R.; Robinson, O.J.; Grillon, C. Sustained Anxiety Increases Amygdala–Dorsomedial Prefrontal Coupling: A Mechanism for Maintaining an Anxious State in Healthy Adults. jpn, 2014, 39, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Cao, L.; Li, H.; Xiao, H.; Ma, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhu, H.; Yuan, M.; Qiu, C.; Huang, X. Dysfunction of Resting-State Functional Connectivity of Amygdala Subregions in Drug-Naïve Patients With Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Front. Psychiatry, 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chen, Z.; Hu, B.; Zhou, F.; Feng, T. The Anxiety-Specific Hippocampus-Prefrontal Cortex Pathways Links to Procrastination through Self-Control. Hum Brain Mapp, 2022, 43, 1738–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.R.; Chao, H.H.-A.; Lee, T.-W. Neural Correlates of Speeded as Compared with Delayed Responses in a Stop Signal Task: An Indirect Analog of Risk Taking and Association with an Anxiety Trait. Cerebral Cortex, 2009, 19, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.R.; Morgan, P.T.; Matuskey, D.; Abdelghany, O.; Luo, X.; Chang, J.L.K.; Rounsaville, B.J.; Ding, Y.; Malison, R.T. Biological Markers of the Effects of Intravenous Methylphenidate on Improving Inhibitory Control in Cocaine-Dependent Patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2010, 107, 14455–14459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, N.H.; Bechara, A. The Hidden Island of Addiction: The Insula. Trends in Neurosciences, 2009, 32, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdejo-Garcia, A.; Clark, L.; Dunn, B.D. The Role of Interoception in Addiction: A Critical Review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 2012, 36, 1857–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.F.; Eulenbruch, T.; Langer, C.; Banger, M. Interoceptive Awareness, Tension Reduction Expectancies and Self-Reported Drinking Behavior. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 2013, 48, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, A.M. Interoception Within the Context of Impulsivity and Addiction. Current Addiction Reports, 2023, 10, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, A.L.; Mandelkern, M.A.; London, E.D.; Childress, A.R.; Lee, G.S.; Bota, R.G.; Ho, M.L.; Saxena, S.; Baxter, L.R., Jr; Madsen, D.; Jarvik, M.E. Brain Metabolic Changes During Cigarette Craving. Archives of General Psychiatry, 2002, 59, 1162–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilts, C.D.; Schweitzer, J.B.; Quinn, C.K.; Gross, R.E.; Faber, T.L.; Muhammad, F.; Ely, T.D.; Hoffman, J.M.; Drexler, K.P.G. Neural Activity Related to Drug Craving in Cocaine Addiction. Archives of General Psychiatry, 2001, 58, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrick, H.; Anton, R.F.; Li, X.; Henderson, S.; Drobes, D.; Voronin, K.; George, M.S. Differential Brain Activity in Alcoholics and Social Drinkers to Alcohol Cues: Relationship to Craving. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2004, 29, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Faith, M.; Patterson, F.; Tang, K.; Kerrin, K.; Wileyto, E.P.; Detre, J.A.; Lerman, C. Neural Substrates of Abstinence-Induced Cigarette Cravings in Chronic Smokers. Journal of Neuroscience, 2007, 27, 14035–14040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joutsa, J.; Moussawi, K.; Siddiqi, S.H.; Abdolahi, A.; Drew, W.; Cohen, A.L.; Ross, T.J.; Deshpande, H.U.; Wang, H.Z.; Bruss, J.; Stein, E.A.; Volkow, N.D.; Grafman, J.H.; van Wijngaarden, E.; Boes, A.D.; Fox, M.D. Brain Lesions Disrupting Addiction Map to a Common Human Brain Circuit. Nat Med, 2022, 28, 1249–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, N.H.; Rudrauf, D.; Damasio, H.; Bechara, A. Damage to the Insula Disrupts Addiction to Cigarette Smoking. Science, 2007, 315, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Mohan, A.; De Ridder, D.; Sunaert, S.; Vanneste, S. The Neural Correlates of the Unified Percept of Alcohol-Related Craving: A fMRI and EEG Study. Sci Rep, 2018, 8, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, O.K.; Köchli, L.; Marino, S.; Luechinger, R.; Hennel, F.; Brand, K.; Hess, A.J.; Frässle, S.; Iglesias, S.; Vinckier, F.; Petzschner, F.H.; Harrison, S.J.; Stephan, K.E. Interoception of Breathing and Its Relationship with Anxiety. Neuron, 2021, 109, 4080–4093.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, M.P.; Stein, M.B. An Insular View of Anxiety. Biological Psychiatry, 2006, 60, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Wei, D.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J.; Jelinčić, V.; Qiu, J. The Role of Mid-Insula in the Relationship between Cardiac Interoceptive Attention and Anxiety: Evidence from an fMRI Study. Sci Rep, 2018, 8, 17280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, R.P.; Kirlic, N.; Misaki, M.; Bodurka, J.; Rhudy, J.L.; Paulus, M.P.; Drevets, W.C. Increased Anterior Insula Activity in Anxious Individuals Is Linked to Diminished Perceived Control. Transl Psychiatry, 2015, 5, e591–e591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.; Tang, X.; Li, H.; Hu, Q.; Cui, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, W.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, C. Altered Interoceptive Processing in Generalized Anxiety Disorder—A Heartbeat-Evoked Potential Research. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2019, 10, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, A.M.; Duka, T. Facets of Impulsivity and Alcohol Use: What Role Do Emotions Play? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 2019, 106, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, A.M.; Duka, T. The Role of Impulsivity Facets on the Incidence and Development of Alcohol Use Disorders. In Recent Advances in Research on Impulsivity and Impulsive Behaviors; de Wit, H., Jentsch, J.D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, A.K.; Friston, K.J. Active Interoceptive Inference and the Emotional Brain. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2016, 371, 20160007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- lifesciencedb. Human Brain (Hypothalamus=red, Amygdala=green, Hippocampus/Fornix=blue, Pons=gold, Pituitary Gland=pink; 2011.

- Tolomeo, S.; Baldacchino, A.; Volkow, N.D.; Steele, J.D. Protracted Abstinence in Males with an Opioid Use Disorder: Partial Recovery of Nucleus Accumbens Function. Transl Psychiatry, 2022, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Chang, L.; Wang, G.-J.; Fowler, J.S.; Franceschi, D.; Sedler, M.; Gatley, S.J.; Miller, E.; Hitzemann, R.; Ding, Y.-S.; Logan, J. Loss of Dopamine Transporters in Methamphetamine Abusers Recovers with Protracted Abstinence. J. Neurosci., 2001, 21, 9414–9418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, T.P.J.; Ahonen, A.; Torniainen, P.; Heikkilä, J.; Pyhtinen, J.; Räsänen, P.; Niemelä, O.; Hillbom, M. Dopamine Transporters Increase in Human Brain after Alcohol Withdrawal. Mol Psychiatry, 1999, 4, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrammen, E.; Roesmann, K.; Rosenbaum, D.; Redlich, R.; Harenbrock, J.; Dannlowski, U.; Leehr, E.J. Functional Neural Changes Associated with Psychotherapy in Anxiety Disorders – A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal fMRI Studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 2022, 142, 104895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Månsson, K.N.T.; Salami, A.; Frick, A.; Carlbring, P.; Andersson, G.; Furmark, T.; Boraxbekk, C.-J. Neuroplasticity in Response to Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Social Anxiety Disorder. Transl Psychiatry, 2016, 6, e727–e727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzschneider, K.; Mulert, C. Neuroimaging in Anxiety Disorders. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 2011, 13, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickie, E.W.; Brunet, A.; Akerib, V.; Armony, J.L. An fMRI Investigation of Memory Encoding in PTSD: Influence of Symptom Severity. Neuropsychologia, 2008, 46, 1522–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).