Submitted:

23 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Related works

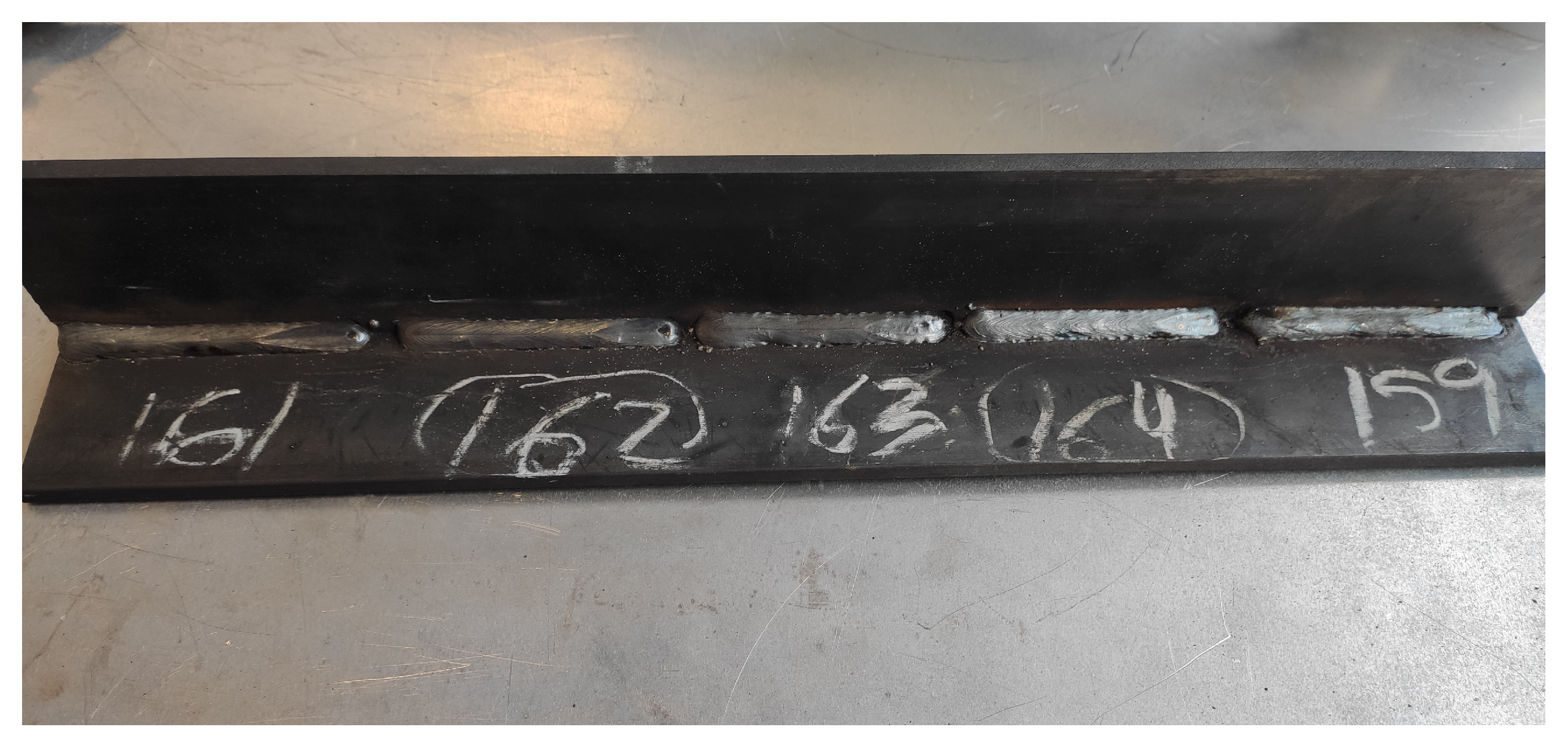

1.3. Contribution

- A set of images of weld seams has been created and made available to the scientific community, where there are images of accepted seams and seams that have some defect: lack of penetration, bites and lack of fusion. These images have been taken with FCAW and GMAW welding differently. The images are captured with a 2D cam, instead of X-ray images, as has traditionally been done in other works.

- The development of a methodology that can be used in other works based on image detection.

- The study and results of three experiments based on the application of neural networks through the analysis of 2D images: the detection of the type of FCAW/GMAW weld, the verification of the goodness of a weld and the detection of certain defects in a weld seam.

1.4. Organization

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Framework

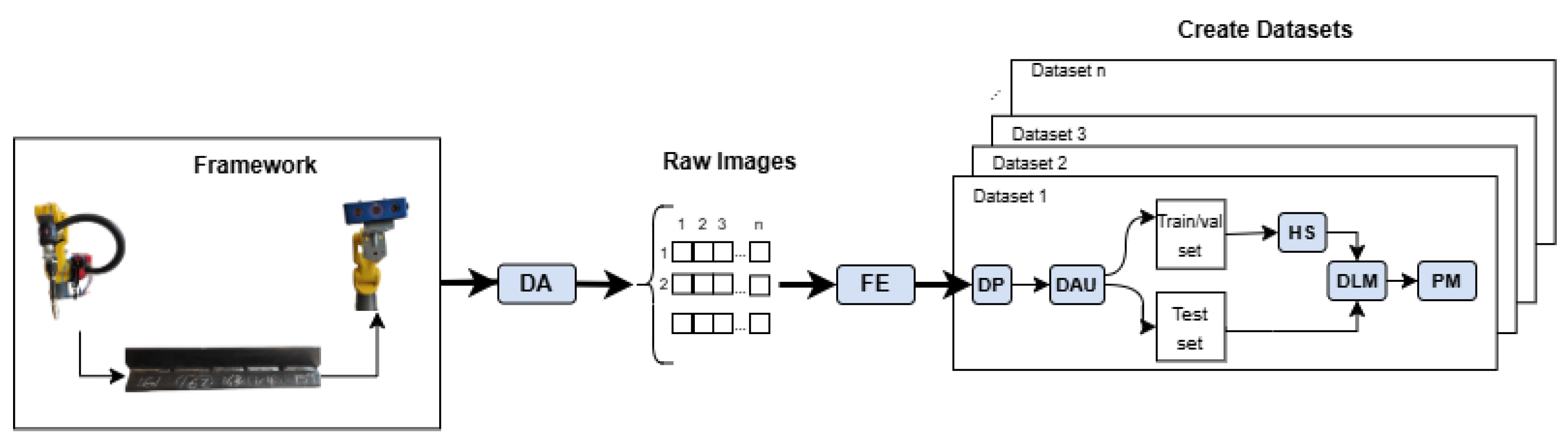

2.2. Methodology

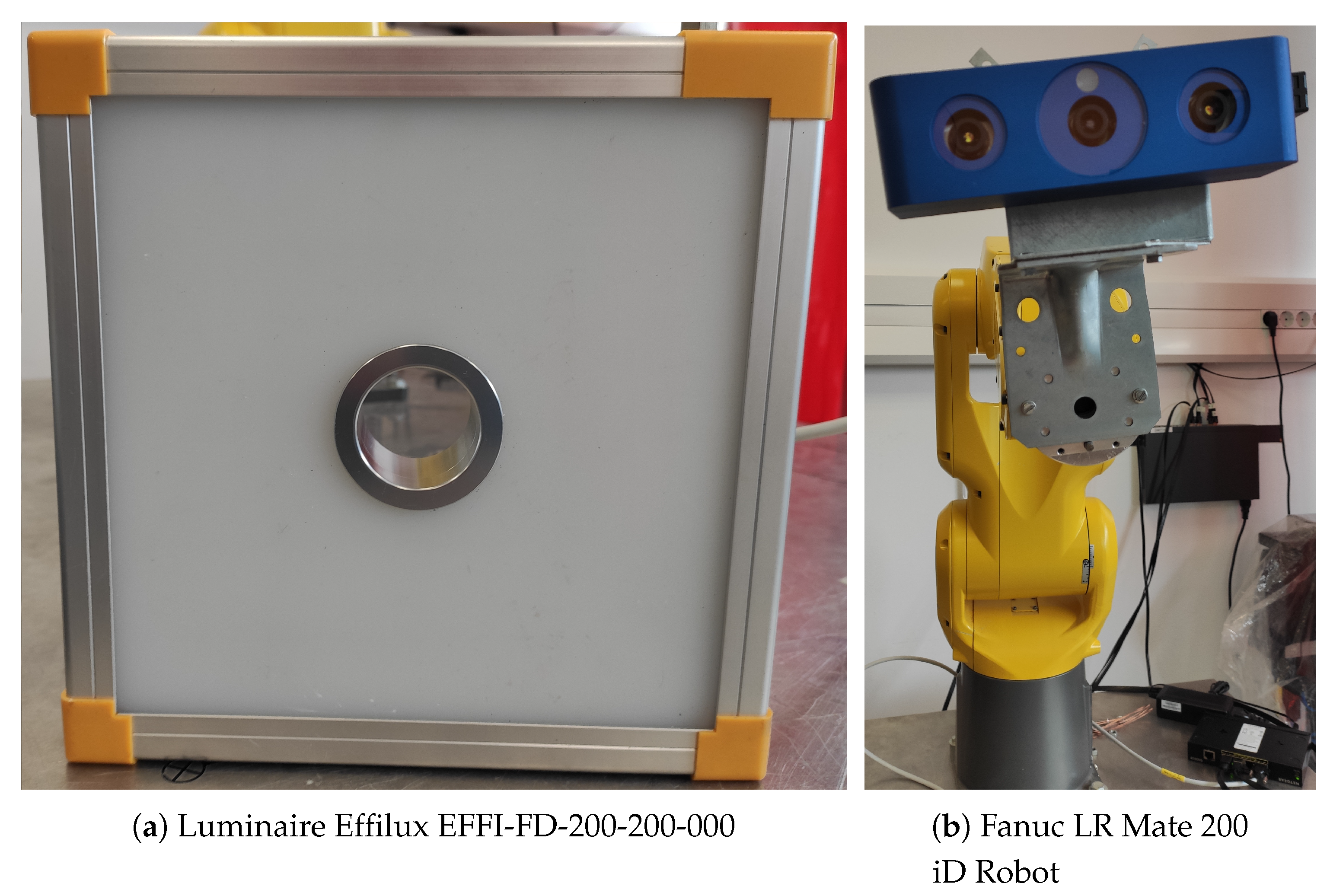

2.2.1. Data Acquisition (DA)

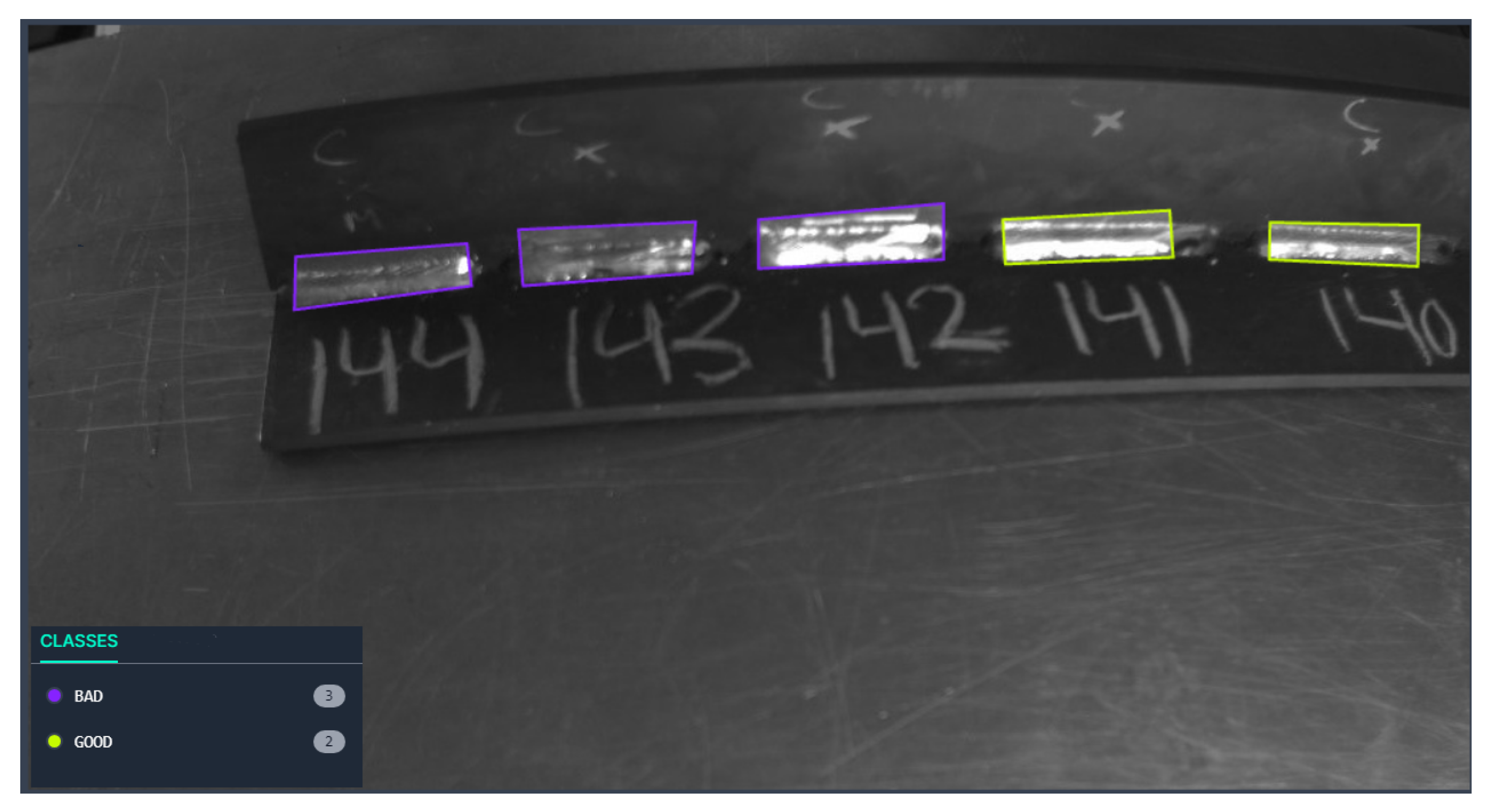

2.2.2. Feature Extraction (FE)

2.2.3. Data Preprocessing (DP)

2.2.4. Data Augmentation (DAU)

- Horizontal flips: This effect will reflect the images horizontally increasing the variety of vertex orientations.

- Shear: add variability to perspective to help the model be more resilient to camera and subject pitch and yaw.

- Noise: the noise to help our model be more resilient to camera artifacts.

2.2.5. Hyper-parameters Selection (HS)

2.2.6. Deep Learning Model (DLM)

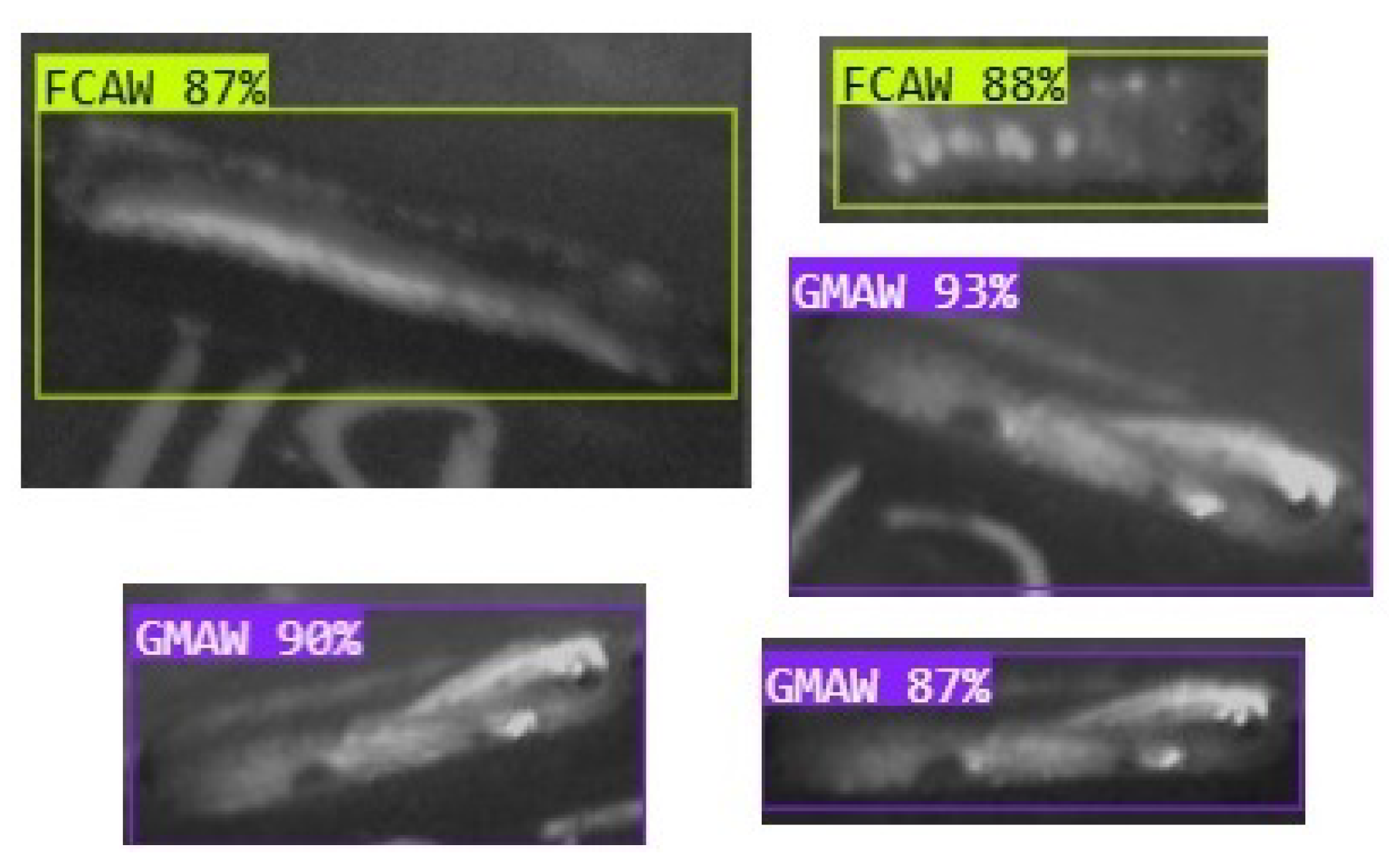

- Differentiate the type of weld used in the manufacture of the weld (FCAW/GMAW).

- Detect whether the weld has been manufactured correctly, according to the standards that a human viewer would have taken into account, regardless of the type of weld used.

- Determine whether the weld has been manufactured correctly. If not, recognize the type of defect that the weld bead has: undercut, lack of penetration, other problems.

2.2.7. Performance Metrics (PM)

-

Recall (R). It is also called sensitivity or TPR (true positive rate), representing the ability of the classifier to detect all cases that are positive, Equation 1.TP (True Positive) represents the number of times a positive sample is classified as positive, i.e. correctly. On the other hand, FN (False Negative) tells us the number of times a negative sample is classified incorrectly.

-

Precision (P). Controls how capable the classifier is to avoid incorrectly classifying positive samples. Its definition can be seen in Equation 2.In this case, FP (false positive) tells us how many times negative samples are classified as positive.

- Intersection over union (IoU) is a critical metric in object detection as it provides a quantitative measure of the degree of overlap between a ground truth (gt) bounding box and a predicted (pd) bounding box generated by the object detector. This metric is highly relevant for assessing the accuracy of object detection models and is used to define key terms such as true positive (TP), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN). It needs to be defined because it will be used to determine the mAP metric. Its definition can be seen in Equation 3.

-

Mean Average Precision (mAP). In object detection is able to evaluate model performance by considering Precision and Recall across multiple object classes. Specifically, mAP50 focuses on an IoU threshold of 0.5, which measures how well a model identifies objects with reasonable overlap. Higher mAP50 scores indicate better overall performance.For a more comprehensive evaluation, mAP50:95 extends the evaluation to a range of IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95. This metric is appropriate for tasks that require precise localization and fine-grained object detection.mAP50 and mAP50:95 are able to help evaluate model performance across multiple conditions and classes, thereby expressing information about object detection accuracy by considering the trade-off between Precision and Recall.Models with higher mAP50 and mAP50-95 scores are more reliable and suitable for demanding applications. These are appropriate metrics to ensure success in projects such as autonomous driving and safety monitoring.Equation 5 shows the calculation of Average Precision, which is necessary to calculate the mean Average Precision (mAP), which can be seen in the equation.

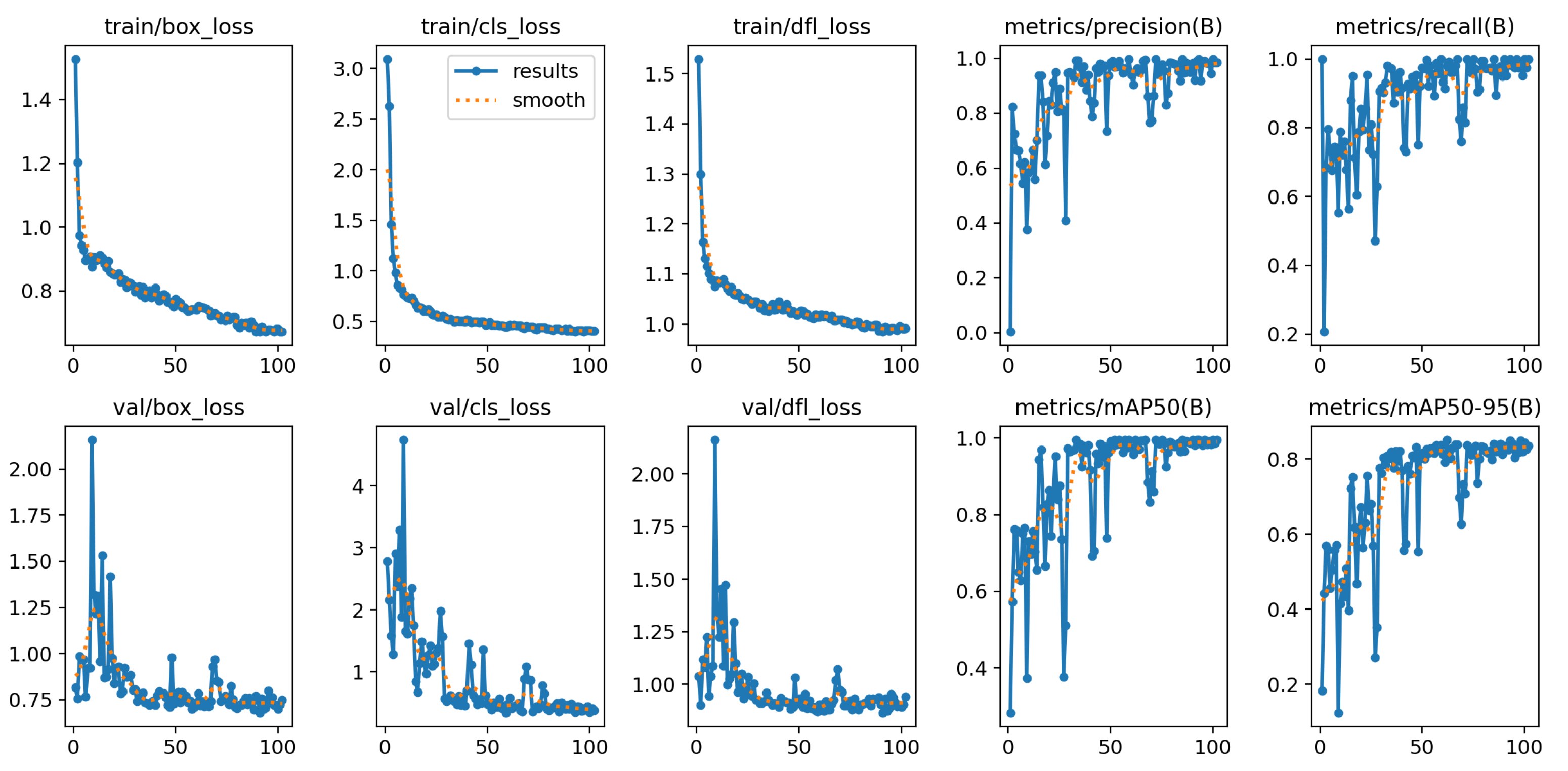

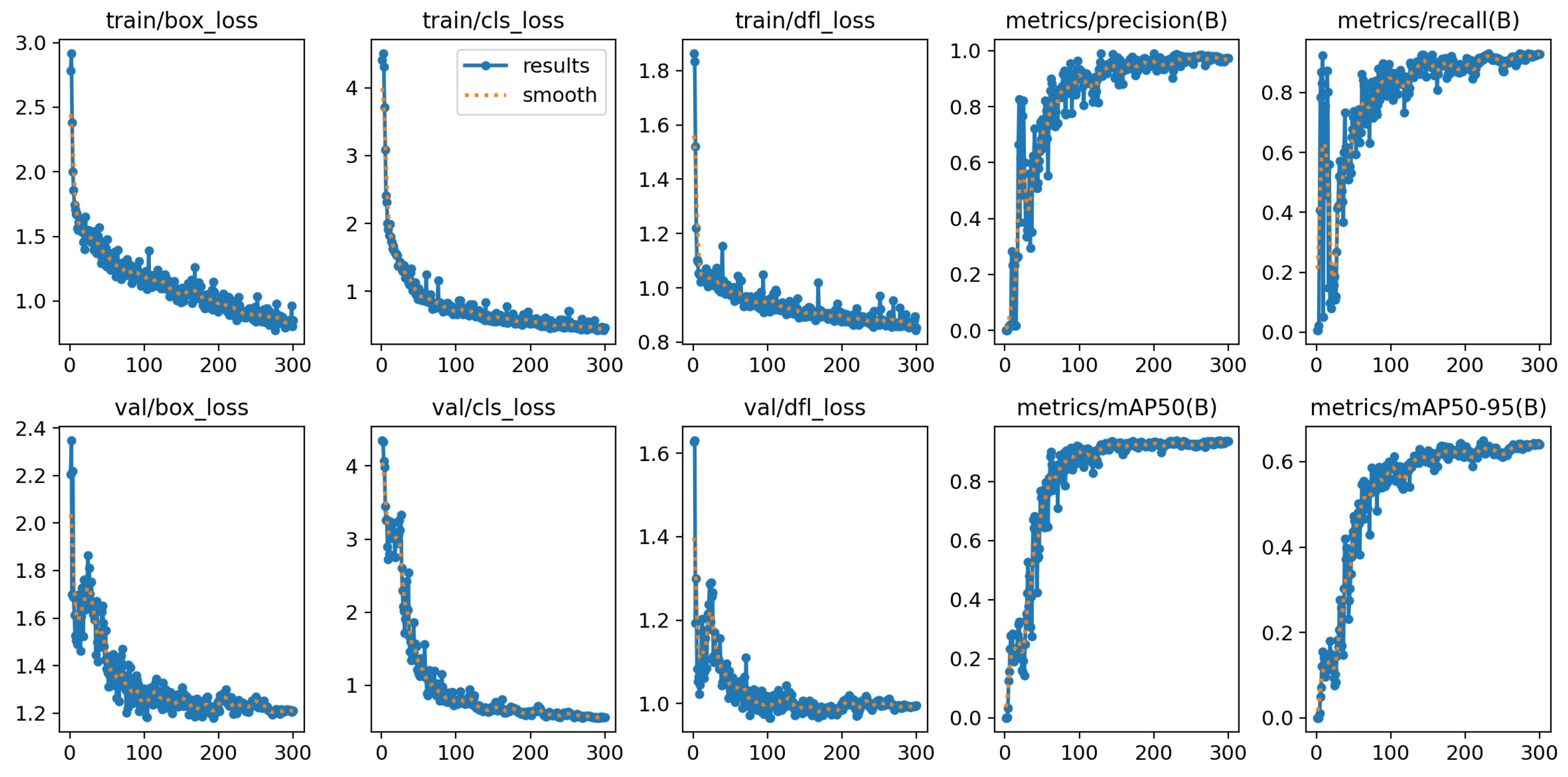

- Box loss: This loss helps the model to learn the correct position and size of the bounding boxes around the detected objects. It focuses on minimizing the error between the predicted boxes and the ground truth.

- Class loss: It is related to the accuracy of object classification. It ensures that each detected object is correctly classified into one of the predefined categories.

- Object loss: It is related to the accuracy with which objects are classified. It ensures that each detected object is correctly classified into one of the predefined categories. That is, object loss is responsible for choosing between objects that are very similar or difficult to differentiate, by better understanding their characteristics and spatial information.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental environment

3.2. Experiments Results and Discussion

3.2.1. Experiment 1: FCAW-GMAW Weld Seam

3.2.2. Experiment 2: Good-Bad Weld Seam

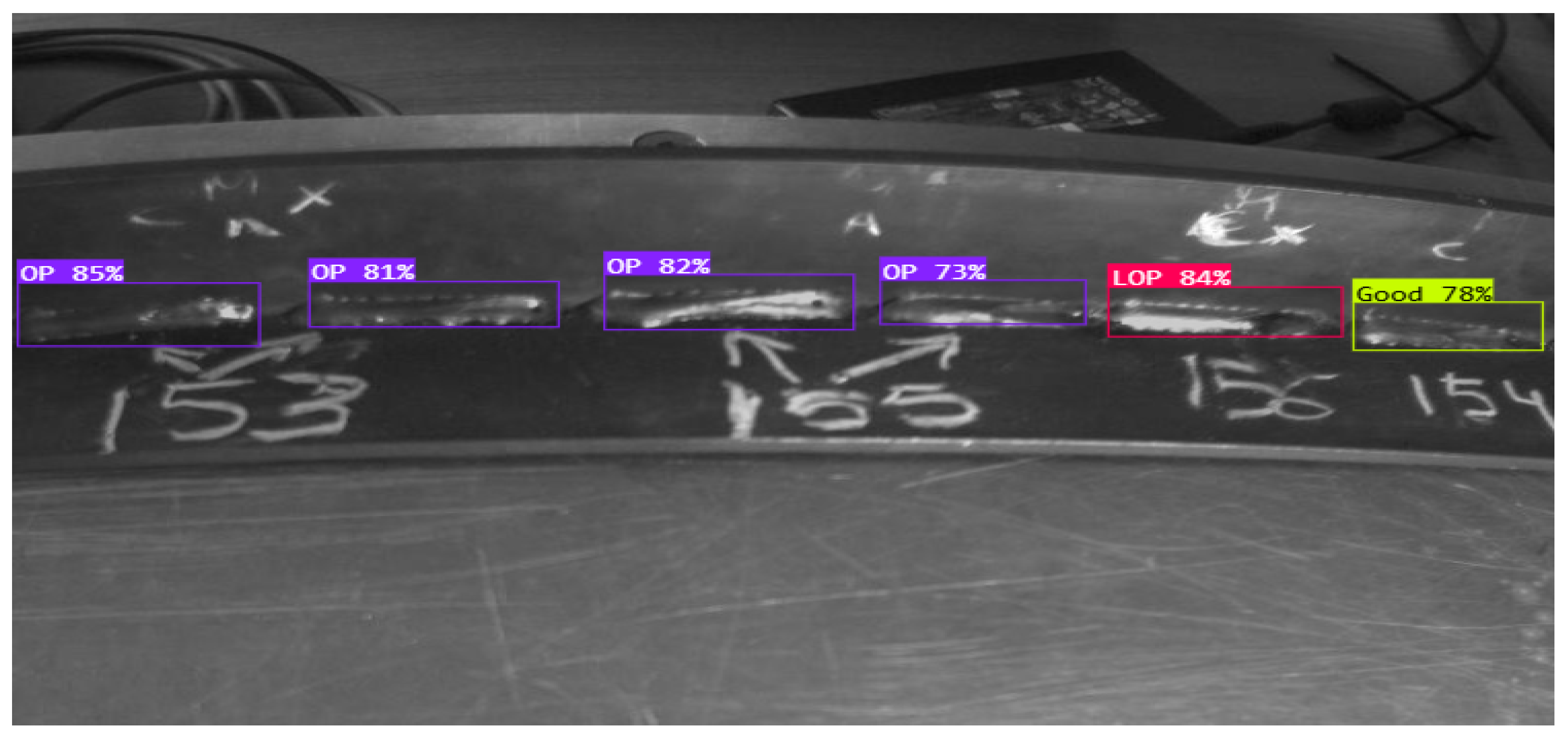

3.2.3. Experiment 3: Good-Lop-Under Weld Seam

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| RPN | Region Proposal Network |

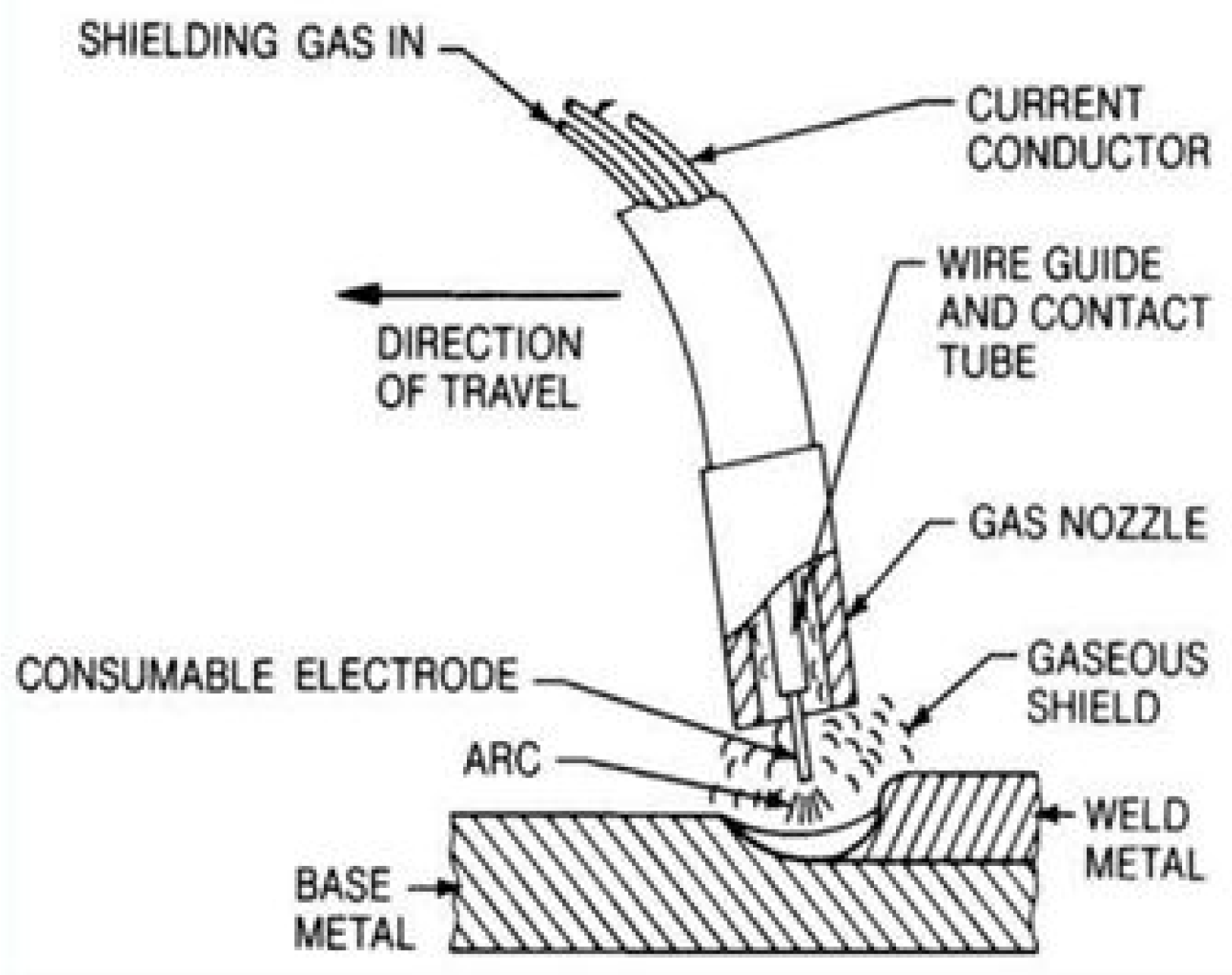

| GMAW | Gas Metal Arc Welding |

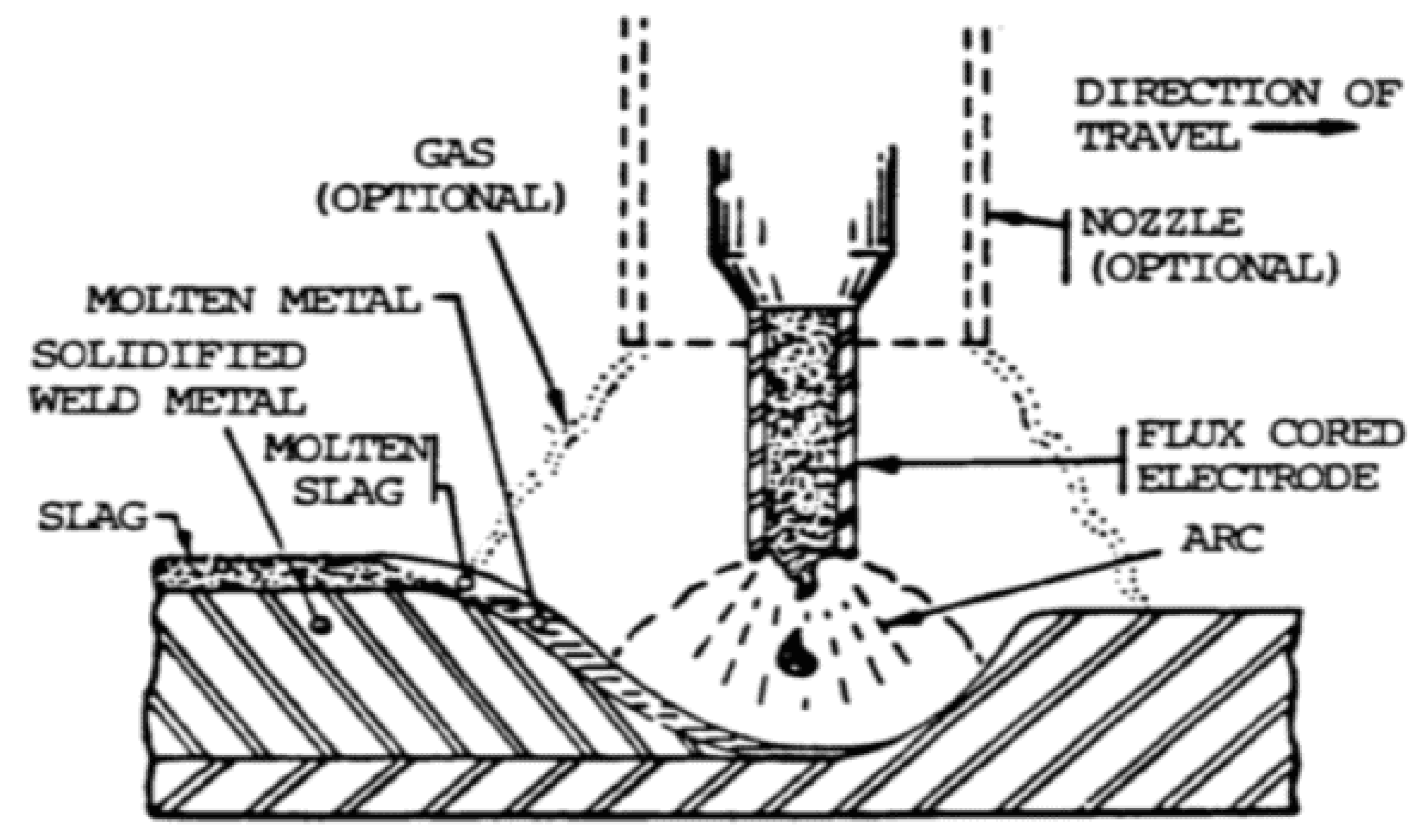

| FCAW | Flux Cored Arc Welding |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| DA | Data Acquisition |

| FE | Feature extraction |

| DP | Data Preprocessing |

| DAU | Data Augmentation |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| NAS | Neural Architecture Search |

| PM | Performance Metrics |

| R | Recall |

| P | Precision |

| TP | True Positive |

| FP | False Positive |

| gt | Ground Truth |

| pd | Predicted Box |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| AP | Average Precision |

| mAP | Mean Average Precision |

| TEP940 | Applied Robotics Research Group of the University of Cadiz |

| ROI | Region Of Interest |

| SSD | Single Shot Detector |

References

- Oh, S.J.; Jung, M.J.; Lim, C.; Shin, S.C. Automatic detection of welding defects using faster R-CNN. Applied sciences 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamat, S.A.; Ibrahim, I.A.; Amir, A.; Ghalib, A. The Effect of Flux Core Arc Welding (FCAW) Processes On Different Parameters. Procedia Engineering 2012, 41, 1497–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.A.; Mohamat, S.A.; Amir, A.; Ghalib, A. The Effect of Gas Metal Arc Welding (GMAW) Processes on Different Welding Parameters. Procedia Engineering 2012, 41, 1502–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Riesco, G. Manual del soldador 28a Edición; Cesol, Asociación Espańola de Soldadura y Technologías de Unión, 2023.

- Katherasan, D.; Elias, J.V.; Sathiya, ·.P.; Haq, ·.A.N. Simulation and parameter optimization of flux cored arc welding using artificial neural network and particle swarm optimization algorithm. J Intell Manuf 2014, 25, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.P.; Ngai, W.K.; Chan, T.W.; Wai, H.w. An artificial neural network approach for parametric study on welding defect classification. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2021, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.S.; Son, J.S.; Park, C.E.; Lee, C.W.; Prasad, Y.K. A study on prediction of bead height in robotic arc welding using a neural network. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 2002, 130-131, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, B.; Zhang, W.; Lu, R.; Wada, S.; Zhang, Y. Real-time penetration state monitoring using convolutional neural network for laser welding of tailor rolled blanks. Journal of manufacturing systems 2020, 54, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Tao, C.; Dong, Z.; Jiang, K.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, C. Prediction of welding residual stress and deformation in electro-gas welding using artificial neural network. Materials today communications 2021, 29, 102786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Huang, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Fang, X. Welding Surface Inspection of Armatures via CNN and Image Comparison. IEEE sensors journal 2021, 21, 21696–21704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nele, L.; Mattera, G.; Vozza, M. Deep Neural Networks for Defects Detection in Gas Metal Arc Welding. Applied Sciences 2022, Vol. 12, Page 3615 2022, 12, 3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mery, D.; Riffo, V.; Zscherpel, U.; Mondragón, G.; Lillo, I.; Zuccar, I.; Lobel, H.; Carrasco, M. GDXray: The Database of X-ray Images for Nondestructive Testing. Journal of nondestructive evaluation 2015, 34, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, J.; Jahn, A.; Stambke, M.; Wehner, O.; Thieringer, R.; Heizmann, M. Camera-based spatter detection in laser welding with a deep learning approach. Forum Bildverarbeitung 2020. Ed.: T. Längle ; M. Heizmann 2020, pp. 317–328. [CrossRef]

- Nacereddine, N.; Goumeidane, A.B.; Ziou, D. Unsupervised weld defect classification in radiographic images using multivariate generalized Gaussian mixture model with exact computation of mean and shape parameters. Computers in industry 2019, 108, 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Cheng, Y.; Feng, Y.; Xiang, J. Industrial laser welding defect detection and image defect recognition based on deep learning model developed. Symmetry (Basel) 2021, 13, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmi, C.; Zapata, J.; Martínez-Álvarez, J.J.; Doménech, G.; Ruiz, R. Using Deep Learning for Defect Classification on a Small Weld X-ray Image Dataset , 2020. [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. Symmetry 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Jiao, L.; Xie, C.; Chen, P.; Du, J.; Li, R. S-RPN: Sampling-balanced region proposal network for small crop pest detection. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2021, 187, 106290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Cortes, C.; Lawrence, N.; Lee, D.; Sugiyama, M.; Garnett, R., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2015, Vol. 28.

- Wang, Y.; Shi, F.; Tong, X. A Welding Defect Identification Approach in X-ray Images Based on Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Computing Methodologies; Huang, D.S.; Huang, Z.K.; Hussain, A., Eds. Springer International Publishing; 2019; pp. 53–64.

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision – ECCV 2016; Leibe, B.; Matas, J.; Sebe, N.; Welling, M., Eds. Springer International Publishing; 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE Computer Society: Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Li, D.; Tang, D.; Wang, H.; Peng, Y. Deep learning approach for defective spot welds classification using small and class-imbalanced datasets. Neurocomputing 2022, 477, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2020, 42, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, G.H.; Oh, S.J.; Shin, S.C. Image Preprocessing Method in Radiographic Inspection for Automatic Detection of Ship Welding Defects. Applied Sciences 2022, Vol. 12, Page 123 2021, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbart. Choosing the Right Shielding Gases for Arc Welding | HobartWelders, 2024.

- Shinichi, S.; Muraoka, R.; Obinata, T.; Shigeru, E.; Horita, T.; Omata, K. Steel Products for Shipbuilding. Technical report, JFE Technical Report; JFE Holdings: Tokyo, Japan, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Roboflow: Computer vision tools for developers and enterprises, 2024.

- Puhan, S.; Mishra, S.K. Detecting Moving Objects in Dense Fog Environment using Fog-Aware-Detection Algorithm and YOLO. NeuroQuantology 2022, 20, 2864–2873. [Google Scholar]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. A survey on Image Data Augmentation for Deep Learning. Journal of Big Data 2019, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.J.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Terven, J.; Córdova-Esparza, D.M.; Romero-González, J.A. A Comprehensive Review of YOLO Architectures in Computer Vision: From YOLOv1 to YOLOv8 and YOLO-NAS. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction 2023, Vol. 5, Pages 1680-1716 2023, 5, 1680–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermens, F. Automatic object detection for behavioural research using YOLOv8. Behavior research methods 2024, 56, 7307–7330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- inc., Y.U. YOLO Métricas de rendimiento - Ultralytics YOLO Docs. 2024-11-02.

- TEP940. Dataset detection FCAW-GMAW welding. https://universe.roboflow.com/weldingpic/weld_fcaw_gmaw , 2024. visited on 2024-10-25.

- TEP940. Dataset detection WELD_GOOD_BAD welding. https://universe.roboflow.com/weldingpic/weldgoodbad , 2024. visited on 2024-11-01.

- TEP940. GOOD-OP-LOP-UNDER Dataset. https://universe.roboflow.com/weldingpic/good-op-lop-under , 2024. visited on 2024-10-30.

| Parameter | Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 | Experiment 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| epochs | 105 | 300 | 300 |

| batch size | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Learning rate | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Optimizer | SGD | SGD | SGD |

| Input image size | 320X320 | 320X320 | 320X320 |

| Confidence Threshold | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| Experiment | Class | Precision | Recall | mAP Val. set |

mAP Test set |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCAW-GMAW weld seam | FCAW | 0.951 | 0.979 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| GMAW | 0.99 | 0.97 | |||

| GOOD-BAD weld seam | GOOD | 0.982 | 0.985 | 0.99 | 0.93 |

| BAD | 0.99 | 0.99 | |||

| GOOD-LOP-UNDER-OP weld seam | GOOD | 0.965 | 0.92 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| LOP | 0.77 | 0.94 | |||

| UNDER | 0.99 | 0.92 | |||

| OP | 0.99 | 0.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).