1. Introduction

Low-dose computed tomography has increased the early detection rate of lung cancer [

1,

2]. In contrast to advanced cancer, early stage cancer can often be adequately treated using less-invasive procedures such as segmentectomy or wedge resection employing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) [

3]. The reduction in surgical incision size compared to that of conventional lobectomy decreases pain [

4]. However, during thoracoscopic surgery, the trocar can damage the intercostal nerves. Also, a postoperatively placed chest tube may cause pain during breathing [

5]. The risk of progression to chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP) is high [

6] and proactive postoperative pain management is crucial. Inadequate pain control can render it impossible to breathe deeply, triggering atelectasis. A pain-induced increase in sympathetic nervous system activity may cause hypertension and increase the risk of postoperative infection via immunosuppression.

After VATS lung wedge resection thoracic surgery, several methods can be used for postoperative pain management. The simplest is intravenous administration of opioid analgesics. However, pain relief using opioids often requires large doses; the side-effects include respiratory depression, nausea, vomiting, and itching [

7,

8]. Regional analgesic methods include thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA), a thoracic paravertebral block (TPVB), an intercostal block, and interpleural local anesthetic infusion [

9]. TEA and TPVB are the most effective methods of pain control [

10,

11]. However, both methods are invasive and may be associated with complications such as pneumothorax, spinal cord injury, hypotension caused by a central nerve block, and/or respiratory issues attributable to muscle depression. Drugs delivered via intercostal catheters, and interpleural drug infusions, do not afford adequate pain control during VATS [

12].

Less-invasive analgesia that nonetheless ensures effective pain relief in VATS lung wedge resection would enhance surgical outcomes and reduce complications. The use of an ultrasound-assisted Serratus anterior plane block (SAPB) as an alternative to a neuroaxial block or a TPVB may afford effective, lateral thoracic paresthesia and reduce the incidence of side effects [

13]. A local anesthetic is delivered under ultrasound guidance to the lower or upper portion of the serratus anterior muscle. This blocks the lateral branch of the intercostal nerve, thereby ensuring analgesia of the lateral aspect of the rib cage [

14]. The procedure is relatively simple and is associated with few complications. The anesthetic is injected under the serratus anterior muscle, which is readily identified via ultrasound; the complications associated with TEB and TPVB are absent. Several studies have reported that SAPB ensures effective analgesia during breast surgery, thoracotomy, and minimally invasive valve surgery [

15,

16,

17]. It also controls pain in patients with rib fractures and those who undergo other thoracic surgeries. For thoracotomy patients, SABP affords pain relief equivalent to that of TEA, and is associated with less hypotension [

11].

Previous studies have focused on lung lobectomy. This major surgical procedure is associated with significant postoperative discomfort. Recently, research has expanded to include thoracoscopic surgery, reflecting the growing use of minimally invasive techniques. However, the increasing inclusion of a broader patient population, such as those undergoing lobectomy or segmentectomy via VATS, introduces additional variables.

In this study, we hypothesized that SAPB would reduce opioid consumption, as measured by patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) data, following thoracoscopic lung wedge resection, compared to the non-block group.

2. Materials and Methods

Patient selection

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Daejeon St. Mary’s Hospital, Daejeon, South Korea (approval no. DC17EESE0076, October 30, 2017) and was registered with the Clinical Research Information Service (code KCT0002626). The single-center prospective randomized controlled study ran from November 2017 to March 2019. Informed consent was obtained from patients and/or their guardians after a thorough explanation (at least 10 min) on the day before surgery.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were patients who underwent lung wedge resection and who requested PCA in our thoracic surgery department, age 20–70 years and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status 1–3. The exclusion criteria were ASA physical status 4 or higher, a history of chronic pain treatment or drug dependence, an inability to communicate with the researcher, current anticoagulant therapy or a bleeding disorder, a body mass index (BMI) of 35 kg/m2 or higher, a lack of a PCA request, and refusal of nerve block. In addition, those who had bled more than 1 L during surgery, whose surgical times exceeded 6 h, and who required mechanical ventilation after surgery were excluded.

Randomization and blinding

The patients were divided into an SAPB group and a control group with equal allocation. A computer-generated random number table was created using R software and the numbers were used to allocate all patients into one of the two groups. The numbers were placed in individual envelopes that were opened on the morning of surgery.

To reduce bias in the study, two individuals performed independent roles as the proceduralist and the evaluator. The proceduralist opened a sealed envelope containing the randomization assignment to determine the participant's group.

If the patient was in the control group, the proceduralist prepared the PCA medication by reference to the patient’s weight. If the patient was in the SAPB group, the proceduralist prepared both the PCA and the local anesthetic. To prevent incorrect mixing of the local anesthetic, a label "IRB number, SAPB group, for research use" was placed on the syringe. After surgery, the labeled syringe was used to establish the SAPB. The evaluator assessed all patients and recorded all data, including pain scores and opioid consumption.

Surgical course

Anesthesia initiation and maintenance were identical for both groups; no premedication was administered. When a patient arrived in the operating room, noninvasive blood pressure, electrocardiograph, and oxygenation monitors were placed. Propofol 2 mg/kg and rocuronium 0.6 mg/kg were administered after preoxygenation. Once the loss of consciousness was adequate and muscle relaxation was apparent, a double-lumen tube was inserted using a bronchoscope chosen by reference to the patient’s weight and height. The tube was connected to a ventilator and general anesthesia was induced by sevoflurane. The concentration of the inhaled agent was adjusted to 0.8–1.2-fold the minimum alveolar concentration (MAC). This maintained an appropriate depth of anesthesia, as monitored by the bispectral index (BIS), which was held between 40 and 60. Remifentanil (Ultiva; GlaxoSmithKline, Brentford, UK) served as an adjunct anesthetic that was continuously administered via a syringe pump (Injectomat TIVA Agilia®; Fresenius Kabi AG, Bad Homburg, Germany) to maintain blood pressure within 20% of the baseline level.

After anesthesia induction, the patient was positioned in the lateral position and one-lung ventilation was initiated. All surgeries were performed by one of two surgeons, each of whom had conducted more than 100 wedge resections. Two or three thoracoscopy ports were inserted. In both groups, fentanyl 1 mcg/kg and ramosetron 0.3 mg were administered 10 min before the end of surgery to prevent nausea and vomiting. After surgery, each patient was repositioned in a supine position, the inhalation anesthetic was discontinued, and the patient was awakened before transfer to the post-anesthetic care unit (PACU), where pain was assessed.

Post-surgery analgesia

Both groups used the same PCA drug and method. The day before surgery, during the consent process, patients were informed about the benefits, potential complications, and limitations of PCA and were told to press the PCA button when their visual analog scale (VAS) pain score exceeded 4.

The PCA (Hospira Gemstar Infusion Pump; Hospira, Lake Forest, IL, USA) was fentanyl 20 mcg/kg and ramosetron 0.3 mg in normal saline. The PCA setup delivered a bolus of 3 mL (0.6 mcg/kg); the refractory period was 5 min and the maximum dose was 40 mL (8 mcg/kg) every 4 h; continuous infusion was impossible. All PCA devices were collected at 48 h after surgery and data were gathered.

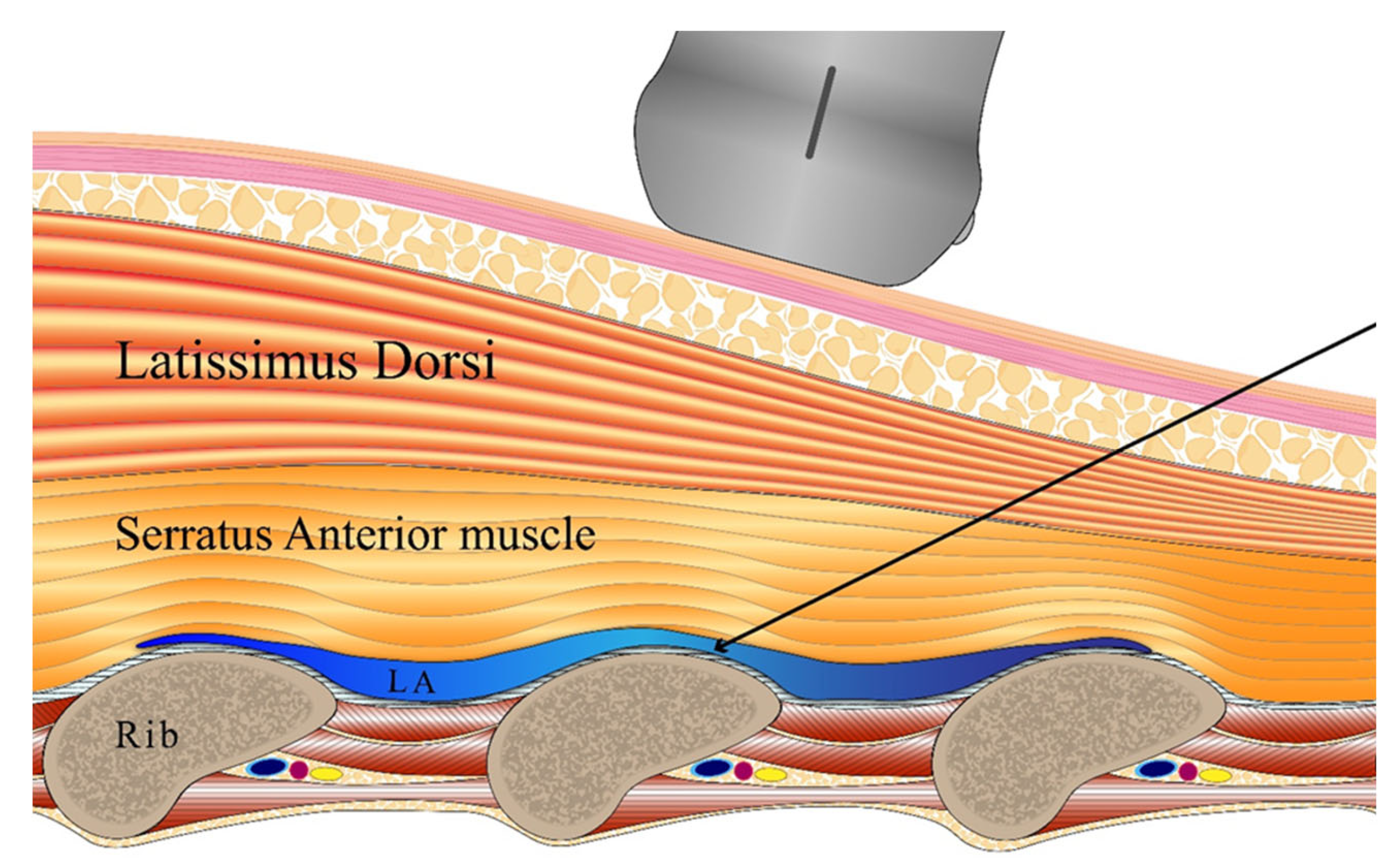

Nerve block

In the SAPB group, a nerve block was performed with the patient in the lateral position, thus before wakening from anesthesia. The block proceeded under ultrasound guidance (probe WS80A: Samsung Medison, Seoul, Republic of Korea; needle device: TaeChang Industrial, Useong-myeon, Republic of Korea). The skin was disinfected with hexitanol. After covering the probe with a sterile film, the intersection of the fifth rib and the mid-axillary line was identified. The probe was positioned perpendicular to the rib axis to show the serratus anterior, the latissimus dorsi, the ribs, and the intercostal muscles. Using the in-plane technique, the needle was advanced under ultrasound guidance and the tip was positioned between the intercostal muscles and the serratus anterior using 0.2% ropivacaine solution. After injection of a 1-mL test dose to confirm separation of the serratus anterior muscle from the rib, the total dose was 0.4 mL/kg (

Figure 1).

Postoperative care

After transfer to the ward, a routine acute pain service protocol commenced. On the evening of surgery, 100 mg aceclofenac and 500 mg paracetamol were given orally. Commencing the next day, aceclofenac was given twice daily and paracetamol was given three times daily. When the VAS pain level exceeded 4, patients were instructed to press the PCA button. If pain persisted, 50 mg tramadol was administered intravenously.

Study indicators

The primary outcome was the total consumption of fentanyl during the first 8 h postoperatively. The secondary outcomes were fentanyl consumption; VAS score at rest and when coughing at 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h postoperatively; number of PCA requests; and complications such as hypotension caused by a central nerve block, respiratory depression, nausea, or vomiting; any additional analgesic requirement; and/or any symptom of local anesthetic toxicity such as altered consciousness and/or seizures.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis employed SPSS software (version 22). The group means of continuous variables (VAS scores and fentanyl consumption) were compared using the t-test. The Mann-Whitney test was employed to compare ordinal categorical variables (postoperative nausea and vomiting [PONV]). The chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used for cross-analysis of proportions.

Sample size

The sample size was based on that of a study [

18] that used postoperative morphine consumption to 12 h as the primary indicator. Given a standard deviation of 2.56 mg, an alpha value of 5%, a statistical power of 80%, and use of a two-tailed test, a clinically significant difference was at least 3.5 mg. Allowing for a 20% failure rate, the required sample size was 22.

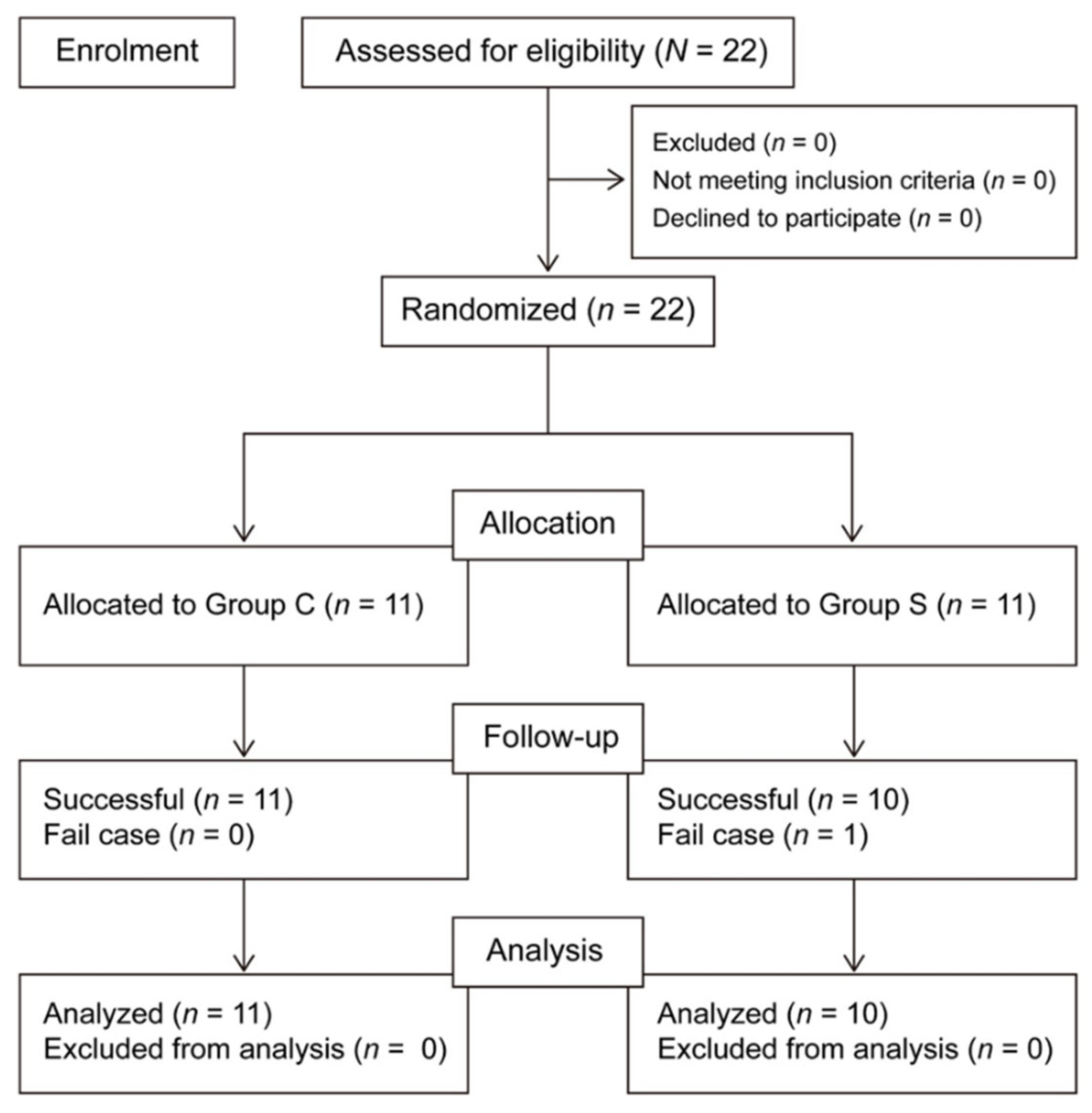

3. Results

Data collection began in January 2018 and ceased in March 2019. In all, 22 patients were enrolled. One patient in the SAPB group was excluded because of conversion from VATS surgery to open thoracotomy. Thus, there were ultimately 10 patients in the SAPB group and 11 in the control group (

Figure 2).

There were no significant between-group differences in age, sex, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), ASA classification, anesthesia or surgery time, number of thoracoscopic ports, bleeding volume, or fluid intake (

Table 1). The primary parameter, fentanyl consumption to 8 h post-surgery, was significantly lower in the SAPB group than in the control group (183 ± 107 μg vs. 347 ± 202 μg, p = 0.035) (

Table 2). In the SAPB group, fentanyl consumption was also significantly lower than that of the control group at 4, 24, and 48 h, but not at 12 h. In both groups, VAS scores decreased similarly over time during both resting and coughing, although the changes were not statistically significant. There were no significant between-group differences in terms of additional analgesics requested on postoperative days 1 and 2, the mean blood pressures at recovery and at 8 and 24 h post-surgery, or oxygen saturation at 8 h post-surgery. No patients required an antiemetic drug and no side effects of local anesthetics were detected (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This randomized clinical study investigated whether a single ultrasound-guided SAPB reduced postoperative opioid consumption. The primary parameter, fentanyl consumption by 8 h post-surgery, was significantly reduced in the SAPB group compared to the control group. In addition, opioid consumption fell during most of the postoperative period (to 48 h). However, although VAS scores were lower in the SAPB group at all time points, the differences were not significant. A simple VAS is commonly used to assess postoperative pain, but VAS scores may not measure postoperative pain reliably [

19] and are linear, whereas actual pain is nonlinear [

20], implying that VAS scores may not evaluate acute pain well after surgery [

21]. A VAS score reflects pain at a specific point in time, not an average pain level, and may thus not represent overall pain well. In addition, our small sample size rendered it difficult to reveal statistical significance. Opioid consumption was thus considered a better way to assess postoperative pain. Similar studies [

22,

23,

24] have reported reduced opioid consumption after SABP. We found that the nerve block may extend beyond 24 h. Whether a serratus plane block should be administered superficially or deeply with respect to the serratus muscle remains controversial [

25,

26]. One study found that superficial administration was associated with wider anesthetic spread, thus blocking the lateral branches of many intercostal nerves. Deep administration was associated with less spread [

14].

If an SAPB created during VATS surgery is to be effective, the block must extend to the intercostal muscles and parietal pleura. Cadaver studies have shown that, when rib fractures are absent and local anesthetic is injected into the sub-serratus space, the continuity of the myofascial plane is not disturbed; the anesthetic does not penetrate the intercostal muscles. However, if a rib is fractured, the plane is disrupted and the anesthetic infiltrates the intercostal muscles [

27]. For this reason, it has been suggested that anesthetic delivery to the deep serratus muscle may be particularly effective for cases with rib fractures [

28]. In addition, many studies on patients undergoing lung surgery via thoracotomy have delivered the anesthetic to the deep serratus muscle [

29,

30,

31]. After VATS, this may afford optimal analgesia; the local anesthetic penetrates the intercostal muscles and nerves.

CPSP is one of the most common complications after surgery, significantly impacting quality of life and imposing both economic and healthcare-related burdens. After thoracotomy, the incidence of severe CPSP is 10%, the risk of CPSP lasting for more than 12 months is 41%, and the neuropathic pain risk is 45% [

32]. Appropriate nerve blocks and other multimodal approaches toward pain management reduce the CPSP risk [

33,

34].

During VATS surgery, a TPVB effectively controls pain by blocking one hemithorax. An erector spinae plane block is also possible [

35]. However, such blocks are created with the patient in a lateral position under general anesthesia, are technically demanding, and may cause critical complications. The VATS surgical incisions are smaller than those of thoracotomy and the port sites are clustered. SAPB can thus be performed without the need for positional change of a patient after surgery; SABP is effective and convenient with minimal complications. EAPB and SABP may afford similar analgesic effects and reductions in opioid consumption [

36].

Our study had several limitations. First, the sample size was small because the primary parameter was opioid consumption; this limited the statistical power. Although a reduction in postoperative pain was observed in the test group, statistical significance was not attained. In addition, nausea and vomiting were rare; it was difficult to compare the two groups. Finally, the control group did not receive a sham block.

5. Conclusions

SABP is simple to perform during VATS. It exhibits an opioid-sparing effect and can thus serve as part of a multimodal approach toward pain management.

Author Contributions

S.J.L. (Formal analysis; Writing—original draft; Writing—review and editing); T.-Y.S. (Data curation; Investigation, Writing—review and editing); C.-K.C. (Data curation; Investigation) G.L. (Data curation; Investigation) W.K. (Conceptualization; Methodology; Supervision; Data curation; Writing—original draft; Writing—review and editing, figure drawing); All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Daejeon St. Mary’s Hospital, Daejeon, South Korea (approval no. DC17EESE0076, October 30, 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

the authors thanks two surgeon, Kwon Jong-beom, and Jong-ho Lee for VATs lung surgery.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aberle, D.R.; Adams, A.M.; Berg, C.D.; Black, W.C.; Clapp, J.D.; Fagerstrom, R.M.; Gareen, I.F.; Gatsonis, C.; Marcus, P.M.; Sicks, J.D. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011, 365, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Koning, H.J.; van der Aalst, C.M.; de Jong, P.A.; Scholten, E.T.; Nackaerts, K.; Heuvelmans, M.A.; Lammers, J.J.; Weenink, C.; Yousaf-Khan, U.; Horeweg, N.; et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.W.Y.; Leung, C.S.; Tsz, C.H.; Lee, B.T.Y.; Chan, H.K.; Sihoe, A.D.L. Does low-dose computed tomography screening improve lung cancer-related outcomes?—a systematic review. Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagahiro, I.; Andou, A.; Aoe, M.; Sano, Y.; Date, H.; Shimizu, N. Pulmonary function, postoperative pain, and serum cytokine level after lobectomy: a comparison of VATS and conventional procedure. Ann Thorac Surg 2001, 72, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neustein, S.M.; McCormick, P.J. Postoperative analgesia after minimally invasive thoracoscopy: what should we do? Can J Anaesth 2011, 58, 423-425, 425-427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayman, E.O.; Parekh, K.R.; Keech, J.; Selte, A.; Brennan, T.J. A Prospective Study of Chronic Pain after Thoracic Surgery. Anesthesiology 2017, 126, 938–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yie, J.C.; Yang, J.T.; Wu, C.Y.; Sun, W.Z.; Cheng, Y.J. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) following video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy: comparison of epidural PCA and intravenous PCA. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan 2012, 50, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael A. Gropper, L.I.E., Lee A. Fleisher, Jeanine P. Wiener-Kronish. Miller's Anesthesia, 9th Edition ed.; Michael A. Gropper, L.I.E., Lee A. Fleisher, Jeanine P. Wiener-Kronish, Neal H. Cohen, Kate Leslie, Ed.; Elsevier: 2019; Volume 2, pp. 680-741.

- Steinthorsdottir, K.J.; Wildgaard, L.; Hansen, H.J.; Petersen, R.H.; Wildgaard, K. Regional analgesia for video-assisted thoracic surgery: a systematic review. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014, 45, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschalk, A.; Cohen, S.P.; Yang, S.; Ochroch, E.A. Preventing and treating pain after thoracic surgery. Anesthesiology 2006, 104, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.E.; Abdallah, N.M.; Bashandy, G.M.; Kaddah, T.A. Ultrasound-Guided Serratus Anterior Plane Block Versus Thoracic Epidural Analgesia for Thoracotomy Pain. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2017, 31, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, K.; Endo, T.; Taira, K.; Sata, N.; Inoue, S.; Takeuchi, M.; Seo, N.; Endo, S. Comparison of the analgesic effects of continuous extrapleural block and continuous epidural block after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2011, 25, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, R.; Parras, T.; McDonnell, J.G.; Prats-Galino, A. Serratus plane block: a novel ultrasound-guided thoracic wall nerve block. Anaesthesia 2013, 68, 1107–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayes, J.; Davison, E.; Panahi, P.; Patten, D.; Eljelani, F.; Womack, J.; Varma, M. An anatomical evaluation of the serratus anterior plane block. Anaesthesia 2016, 71, 1064–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madabushi, R.; Tewari, S.; Gautam, S.K.; Agarwal, A.; Agarwal, A. Serratus anterior plane block: a new analgesic technique for post-thoracotomy pain. Pain Physician 2015, 18, E421–424. [Google Scholar]

- Hards, M.; Harada, A.; Neville, I.; Harwell, S.; Babar, M.; Ravalia, A.; Davies, G. The effect of serratus plane block performed under direct vision on postoperative pain in breast surgery. J Clin Anesth 2016, 34, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazior, M.R.; King, A.B.; Lopez, M.G.; Billings, F.T.t.; Costello, W.T. Serratus anterior plane block for minimally invasive valve surgery thoracotomy pain. J Clin Anesth 2019, 56, 48–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ökmen, K.; Ökmen, B.M. The efficacy of serratus anterior plane block in analgesia for thoracotomy: a retrospective study. J Anesth 2017, 31, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baamer, R.M.; Iqbal, A.; Lobo, D.N.; Knaggs, R.D.; Levy, N.A.; Toh, L.S. Utility of unidimensional and functional pain assessment tools in adult postoperative patients: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth 2022, 128, 874–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, P.S.; Troedel, S.; Boquest, M.; Reeves, M. The pain visual analog scale: is it linear or nonlinear? Anesth Analg 1999, 89, 1517–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, P.S.; Urquhart, N. The linearity of the visual analogue scale in patients with severe acute pain. Anaesth Intensive Care 2005, 33, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Oh, Y.J.; Lee, J.G.; Ha, D.; Chang, Y.J.; Kwak, H.J. Efficacy of Ultrasound-Guided Serratus Plane Block on Postoperative Quality of Recovery and Analgesia After Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery: A Randomized, Triple-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Anesth Analg 2018, 126, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, X. Effects of serratus anterior plane block for postoperative analgesia after thoracoscopic surgery compared with local anesthetic infiltration: a randomized clinical trial. J Pain Res 2019, 12, 2411–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semyonov, M.; Fedorina, E.; Grinshpun, J.; Dubilet, M.; Refaely, Y.; Ruderman, L.; Koyfman, L.; Friger, M.; Zlotnik, A.; Klein, M.; et al. Ultrasound-guided serratus anterior plane block for analgesia after thoracic surgery. J Pain Res 2019, 12, 953–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piracha, M.M.; Thorp, S.L.; Puttanniah, V.; Gulati, A. "A Tale of Two Planes": Deep Versus Superficial Serratus Plane Block for Postmastectomy Pain Syndrome. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2017, 42, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, F.W.; Cil, T.; MacLean, D.; Madjdpour, C.; Escallon, J.; Semple, J.; Brull, R. Too Deep or Not Too Deep?: A Propensity-Matched Comparison of the Analgesic Effects of a Superficial Versus Deep Serratus Fascial Plane Block for Ambulatory Breast Cancer Surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2018, 43, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.F.; Black, N.D.; O'Halloran, R.; Turbitt, L.R.; Taylor, S.J. Cadaveric findings of the effect of rib fractures on spread of serratus plane injections. Can J Anaesth 2019, 66, 738–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C.R. Serratus anterior plane block for posterior rib fractures: why and when may it work? Reg Anesth Pain Med 2021, 46, 835–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ökmen, K.; Metin Ökmen, B. Evaluation of the effect of serratus anterior plane block for pain treatment after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2018, 37, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H.; Kim, J.A.; Ahn, H.J.; Yang, M.K.; Son, H.J.; Seong, B.G. A randomised trial of serratus anterior plane block for analgesia after thoracoscopic surgery. Anaesthesia 2018, 73, 1260–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viti, A.; Bertoglio, P.; Zamperini, M.; Tubaro, A.; Menestrina, N.; Bonadiman, S.; Avesani, R.; Guerriero, M.; Terzi, A. Serratus plane block for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery major lung resection: a randomized controlled trial. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2020, 30, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, D.C.; Pogatzki-Zahn, E.M. Chronic post-surgical pain - update on incidence, risk factors and preventive treatment options. BJA Educ 2022, 22, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplowitz, J.; Papadakos, P.J. Acute pain management for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: an update. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2012, 26, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, J.; Jackson, M.; Kavanagh, B.P.; Sandler, A.N. Acute pain after thoracic surgery predicts long-term post-thoracotomy pain. Clin J Pain 1996, 12, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feray, S.; Lubach, J.; Joshi, G.P.; Bonnet, F.; Van de Velde, M. PROSPECT guidelines for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a systematic review and procedure-specific postoperative pain management recommendations. Anaesthesia 2022, 77, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnerty, D.T.; McMahon, A.; McNamara, J.R.; Hartigan, S.D.; Griffin, M.; Buggy, D.J. Comparing erector spinae plane block with serratus anterior plane block for minimally invasive thoracic surgery: a randomised clinical trial. Br J Anaesth 2020, 125, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).