1. Introduction

With the rapid development of modern electronic technology and informatization, electromagnetic pollution has become a global concern [

1], driving an increasing demand for electromagnetic wave-absorbing materials. Traditional absorbing materials, such as metal oxides and ferrite-based composites, have been widely applied due to their excellent absorption performance in low-frequency bands [

2,

3,

4,

5]. However, these materials typically suffer from high density, large thickness, and narrow absorption bandwidth, making them unsuitable for lightweight and high-efficiency absorption scenarios [

6,

7]. This limitation hinders their broader application in fields such as aerospace, 5G communication, and wearable electronic devices [

8].

To address these issues, researchers have increasingly focused on developing novel lightweight absorbing materials aimed at reducing weight while maintaining high absorption efficiency [

9,

10]. For example, MXene materials and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), as advanced wave-absorbing agents, demonstrate excellent electromagnetic wave absorption potential due to their high conductivity, superior dielectric loss properties, and high specific surface area [

11,

12,

13]. However, these wave-absorbing agents often rely on high-density matrix materials, such as metals or heavily filled polymer matrices, which not only increase the overall material density but also limit their applicability in lightweight and flexible applications [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Furthermore, traditional matrix materials lack controllability in porous structure design and optimization of mechanical properties, making it challenging to achieve a comprehensive balance between absorption performance and structural properties This highlights the critical role of matrix design in the development of lightweight absorbing materials, requiring matrices to not only provide structural support but also significantly reduce density and enhance the dispersion and synergy of wave-absorbing agents [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

In recent years, the development trend has gradually shifted towards lightweight mesoporous materials based on polymers [

24,

25,

26,

27], such as epoxy resin. These materials not only possess low density and excellent mechanical properties but also enable the formation of complex porous structures through foaming techniques [

28]. However, their development still faces numerous challenges, including the complexity of foaming processes, difficulties in precisely controlling pore structure uniformity, limitations in improving wave absorption performance, and the challenge of achieving a synergy between mechanical and wave absorption properties [

29]. Particularly in advanced processes like supercritical foaming, the need for precise control of process parameters and high costs significantly limit large-scale industrial applications [

30]. Researchers aim to address these issues by introducing nucleation-free foaming techniques to simplify the foaming process [

31,

32], designing functionalized wave-absorbing agents to improve compatibility and absorption efficiency, and constructing hierarchical porous structures to achieve multi-performance optimization. These efforts are expected to advance the research and application of epoxy resin foamed materials in the field of lightweight and high-efficiency wave-absorbing materials.

Based on this, the present study employs a nucleation-free foaming process to construct porous structures. Unlike traditional nucleating agents, nucleation-free foaming directly forms pores in the epoxy resin matrix by controlling the gas generation and release process, simplifying the fabrication process and improving pore uniformity. In this process, carbon-based materials and ferrite absorbers are separately introduced to further optimize absorption performance. Carbon-based materials provide effective dielectric loss, magnetic absorbers enhance broadband absorption through magnetic loss. By fine-tuning the nucleation-free foaming process and the strategic distribution of absorbers. This study achieved lightweight design and multi-performance synergy optimization.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The reagents used in this study include epoxy resin E51 (Nantong Star Synthetic Materials Co., Ltd., analytical grade), epoxy resin curing agent D230 (Kunshan Jiulimei Electronic Materials Co., Ltd., analytical grade), carbon dioxide (Shandong Chenyan Industrial Technology Co., Ltd., 99.9% purity), melamine (Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., 99.9% purity), Ni(CH₃COO)₂·4H₂O (Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., 99.0% purity), ferric citrate (Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., analytical grade), ferrite wave absorber (Nanjing Aipu Hui Technology Co., Ltd., analytical grade), and fumed silica (Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., analytical grade). Additionally, transparent epoxy potting adhesives A and B (Foshan Xinboqiao Electronics Co., Ltd.), 1,3-cyclohexanediamine (Zhengzhou Wubaotong Trading Co., Ltd., analytical grade), and 1,4-dicyclohexane (Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., >98.0% purity) were used.

2.2. Formulation and Preparation of LFAMs

2.2.1. Preparation of Carbon-Based Wave Absorber

Fe-Ni-C composite absorbers were prepared using ferric citrate and nickel acetate tetrahydrate (Ni(CH₃COO)₂·4H₂O) as precursors and melamine as a carbon and nitrogen source through solution-based ultrasonic dispersion, low-temperature drying, and high-temperature calcination in a tube furnace. First, ferric citrate and nickel acetate were dissolved in deionized water at a molar ratio of 1:1 to form a homogeneous precursor solution. Melamine was then added to the solution, and the mixture was stirred to form a stable suspension, followed by ultrasonic treatment for 30 minutes to ensure thorough dispersion of all components. The resulting mixture was dried at 80°C to obtain a solid precursor powder. The dried precursor was placed in a tube furnace and heated under a nitrogen atmosphere at a ramp rate of 5°C/min to 600°C, where it was held for 2 hours. During the high-temperature process, melamine decomposed to generate nitrogen-doped carbon, which combined with metal ions to form a uniform composite structure.

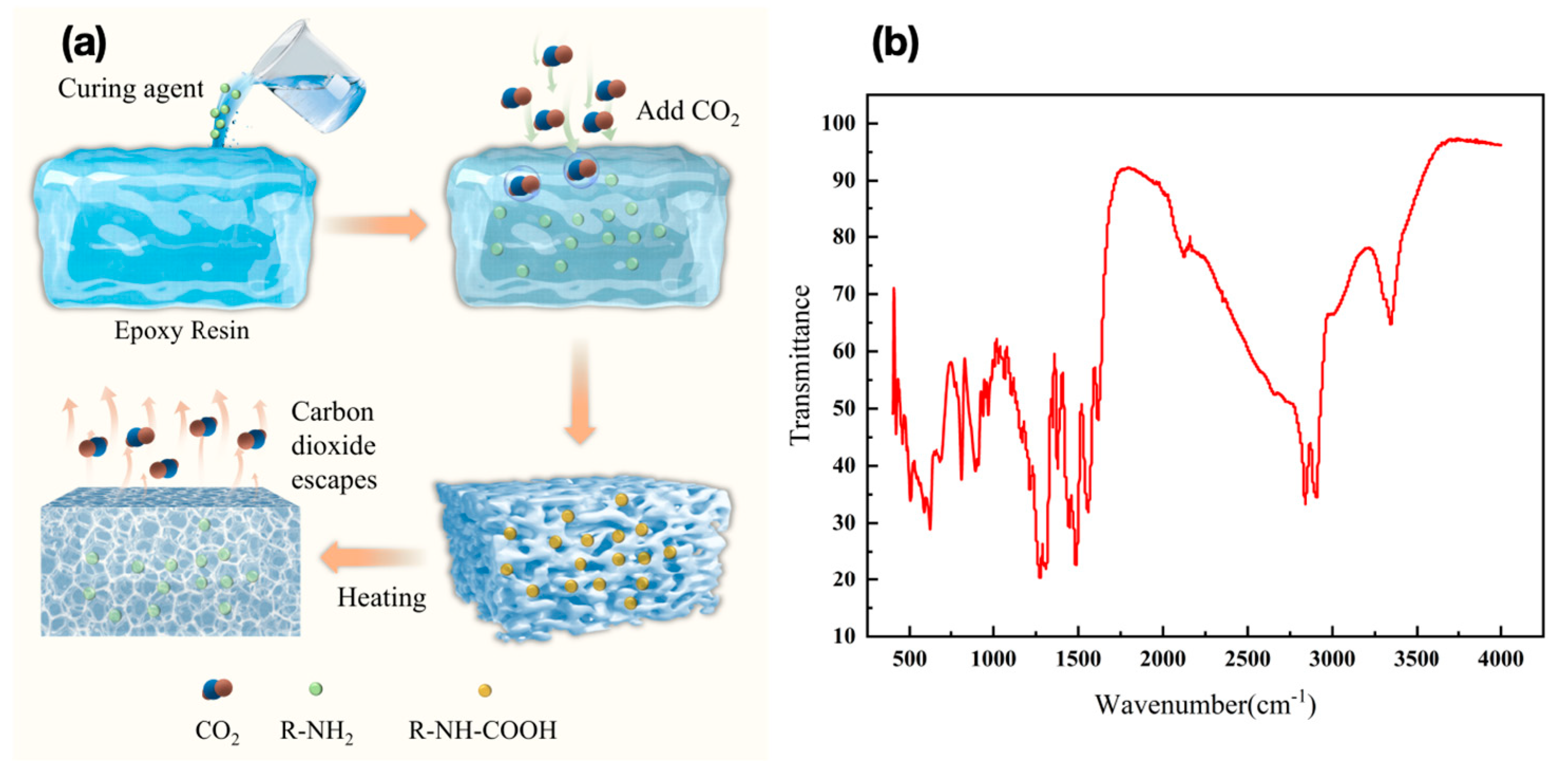

2.2.2. Epoxy Resin Initial Pre-Curing with CO2

The preparation process begins with pre-polymerization, where a specified amount of epoxy resin E51 and curing agent D230 is measured and placed in an ultrasonic cleaner at 30°C for thorough mixing via ultrasonic agitation. After pre-polymerization, primary curing is conducted, and carbon dioxide is introduced into the mixture through a steel pipette at a controlled gas intake rate, with close observation. When the sample no longer produces white flocculent precipitates, indicating complete reaction between the CO₂ and curing agent, the CO₂ introduction is halted.

2.2.3. Secondary Curing Preparation of LFAMs Samples

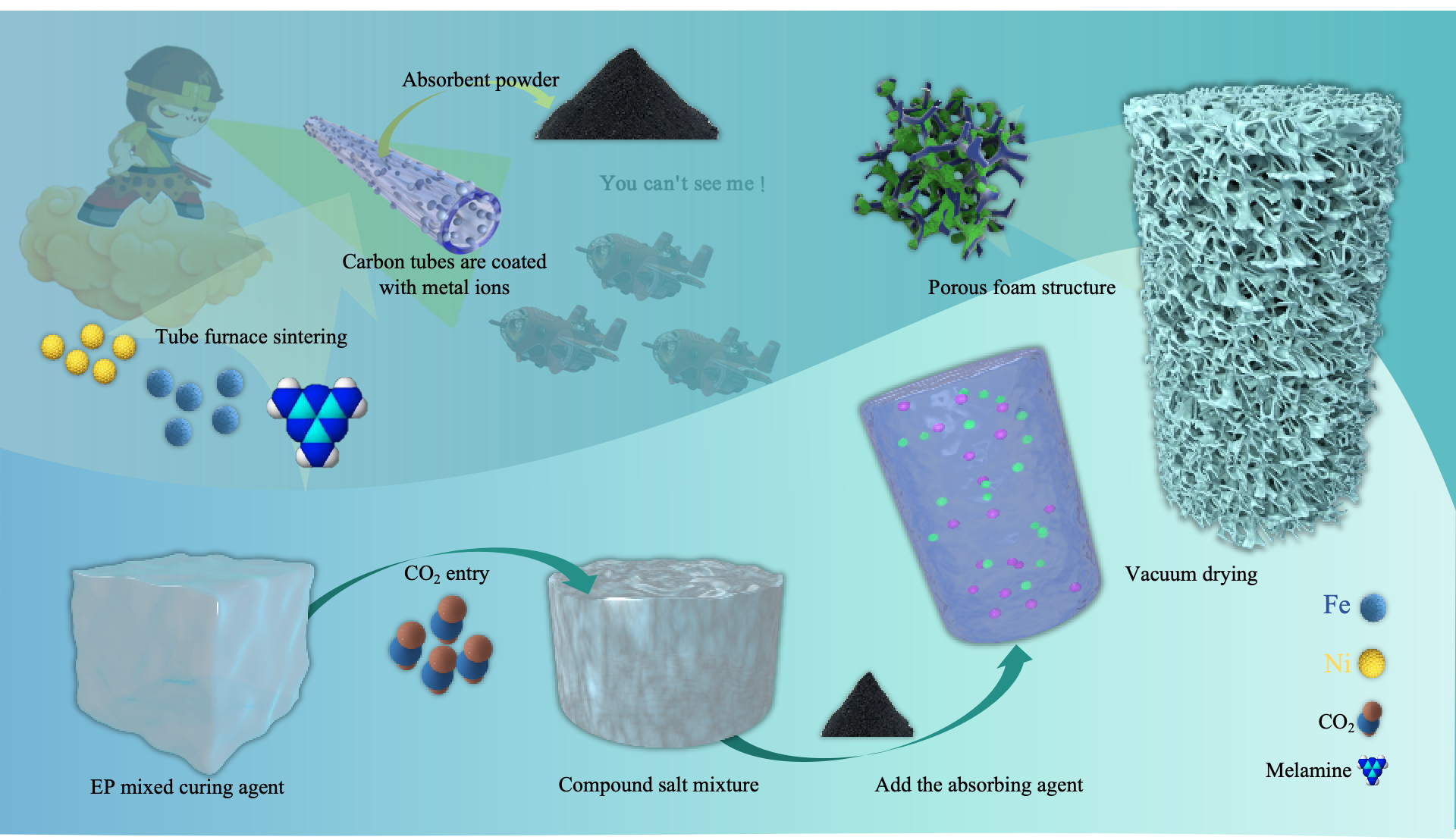

The process continues with pre-heating treatment, where additional epoxy resin is added to the sample according to the resin-to-curing agent ratio (e.g. 2:1 or 3:1). The mixture is stirred to dissolve the previously formed white flocculent precipitates in the resin, after which a wave absorber is added to enhance the material’s absorption performance. This mixture is then placed in an ultrasonic cleaner at 30°C, sealed, and ultrasonically mixed to ensure uniform dispersion of all components and the initial formation of a micro-porous structure. Following this, secondary curing is conducted by monitoring the viscosity, and once it reaches an adequate level, the sample is placed in a vacuum drying oven. Vacuum treatment is applied, allowing the sample to foam at 80°C under vacuum, ultimately yielding an electromagnetic composite material with a micro-porous structure, The preparation process of the wave absorber and epoxy resin nucleus-free foaming is shown in

Figure 1. and the specific formulation design is detailed in

Table 1.

2.3. Characterization

2.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

The cross-sectional morphology, particle size, and distribution of wave absorbers within the epoxy resin matrix were analyzed using the SEM. It was observed that the samples, when placed on the side of the electron microscope stage and coated with gold, exhibited detailed microstructures under an acceleration voltage of 10 kV and magnification ranging from 500x to 2000x.

2.3.2. Specific Surface Area Analysis (BET)

The pore structure of the epoxy foam-based wave-absorbing materials was characterized using the Kubo X1000 specific surface area analyzer from Beijing Beode Electronics Co., Ltd.During the testing process, a certain amount of nitrogen gas was adsorbed onto the surface of the epoxy foam material.

2.3.3. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

The thermal properties and crystal structure of the materials were assessed to identify compounds, crystalline or amorphous substances, using the XRD with the Diffraktometer D8 from Bruker Technology Co., Ltd. The analysis utilized a copper target to generate Cu Kα radiation (wavelength λ = 1.5406 Å), with a scanning range from 15° to 90° and a scanning speed of 10° per minute.

2.3.4. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR)

The formation of ammonium salts during the preparation process was analyzed using the FT-IR spectrometer to investigate the foaming mechanism of CO₂ in epoxy foam. Utilizing the FT-IR spectrometer from Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA, the analysis was conducted with the attenuated total reflection (ATR) method. The experimental parameters were set as follows: a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹, 30 scans, and a scanning range spanning from 400 cm⁻¹ to 4000 cm⁻¹.

2.3.5. Vector Network Analyzer (VNA)

The real permittivity (ε′), imaginary permittivity (ε″), real permeability (μ′), and imaginary permeability (μ″) of the epoxy foam-based wave-absorbing materials were measured using the Agilent Technologies E8363B PNA vector network analyzer (VNA) over the 2–18 GHz frequency range. The samples were prepared in a coaxial ring shape with an outer diameter of 7.0 mm, an inner diameter of 3.5 mm, and a thickness of 2.0–3.0 mm.

2.3.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

The thermal properties and crystal structure of the materials were analyzed to measure the structure and thermal stability of the composite materials using the DSC, the DSC 200 F3 from Netzsch Instrument Manufacturing Co., Germany. The analysis was performed under a nitrogen atmosphere with a heating rate of 10°C/minute, covering a temperature range from 30°C to 250°C.

3. Results

3.1. Microstructure and Morphology Analysis

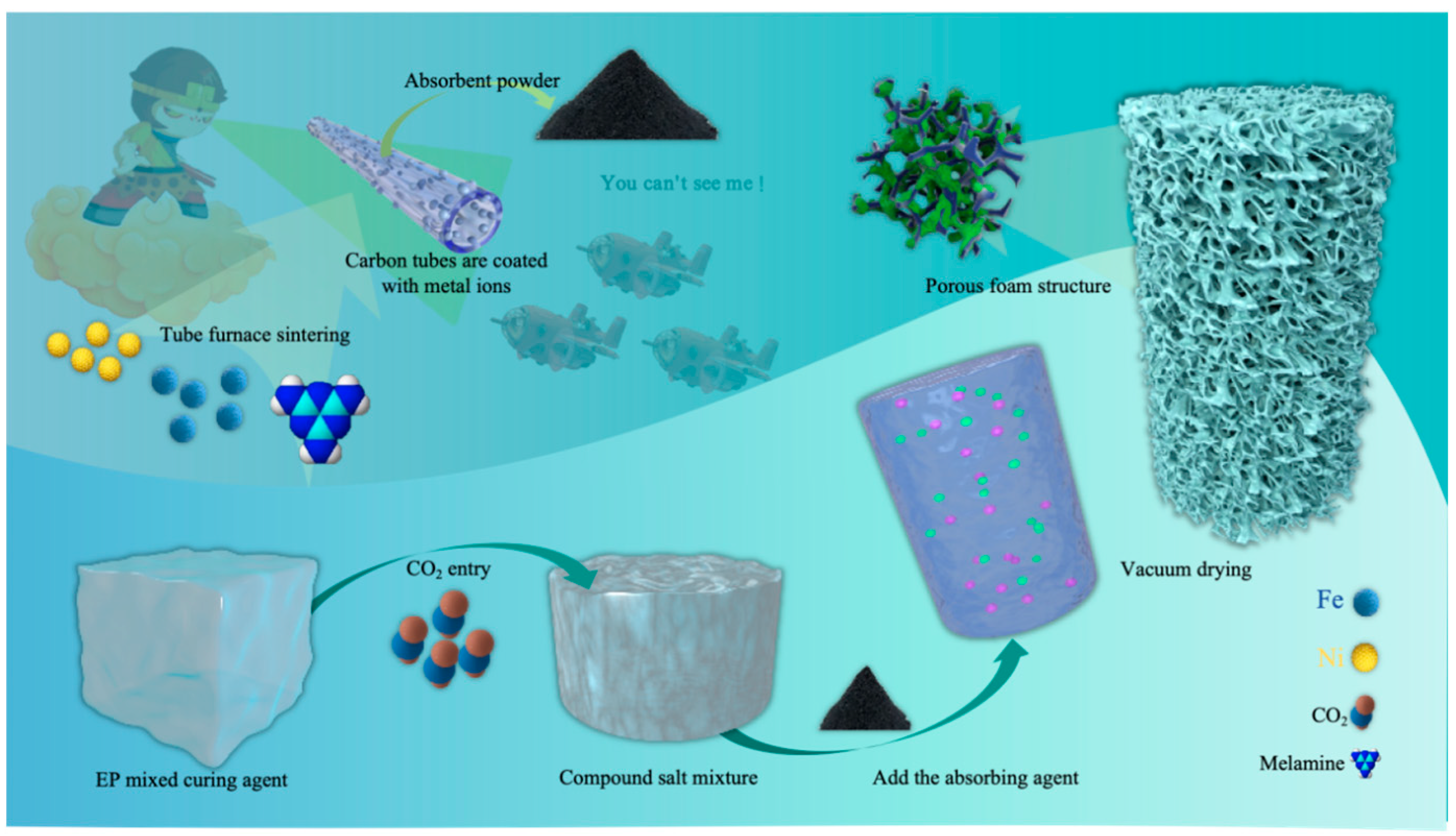

The microscopic structure observed through SEM reveals that all components exhibit varying degrees of porous structures. Notably,

Figure 2(e) shows that the A2 sample, with the addition of 2.0 wt% carbon-based absorbing agents, displays a typical porous structure consisting of elongated voids and cracks of different sizes, which are relatively uniformly distributed. Additionally, the dark regions within the voids may correspond to the deposition or local aggregation of carbon-based absorbing agents, further confirming their successful dispersion and effective incorporation into the epoxy matrix [

33].

Similarly, in the samples with 2.0 wt% carbon-based absorbing agents + SiO₂ (LFAMs—B2) and 2.0 wt% ferrite absorbing agents (LFAMs—C2), similar porous structures can be observed (

Figure 2(f, g)). These porous structural features suggest the formation of an ordered pore network within the material, which enhances electromagnetic wave attenuation through multiple reflections and scattering, thereby improving the absorption capability. In the LFAMs—B2 and LFAMs—C2 samples, irregularly shaped and sized particles are present, with fine cracks or layered structures observed between them. The surfaces of these particles are rough, featuring noticeable pores and uneven textures. These particles are likely uniformly dispersed SiO₂ or ferrite. Although the addition of silica particles provides more nucleation sites, it also occupies part of the matrix volume, reducing the space available for bubble expansion and thus decreasing the foaming volume [

34]. Moreover, the incorporation of silica could increase the matrix viscosity, restricting bubble expansion and growth (

Table 1. Foaming volume).

This ordered porous structure indicates that during the nucleation-free foaming process, the absorbing agents may act as nucleating agents, significantly promoting uniform pore formation. This mechanism not only facilitates a more efficient bubble distribution during foaming but also potentially optimizes the size and morphology of the pores, providing crucial support for the fine-tuning of the material’s microstructure.

3.2. Pore Structure and Specific Surface Area Characterization

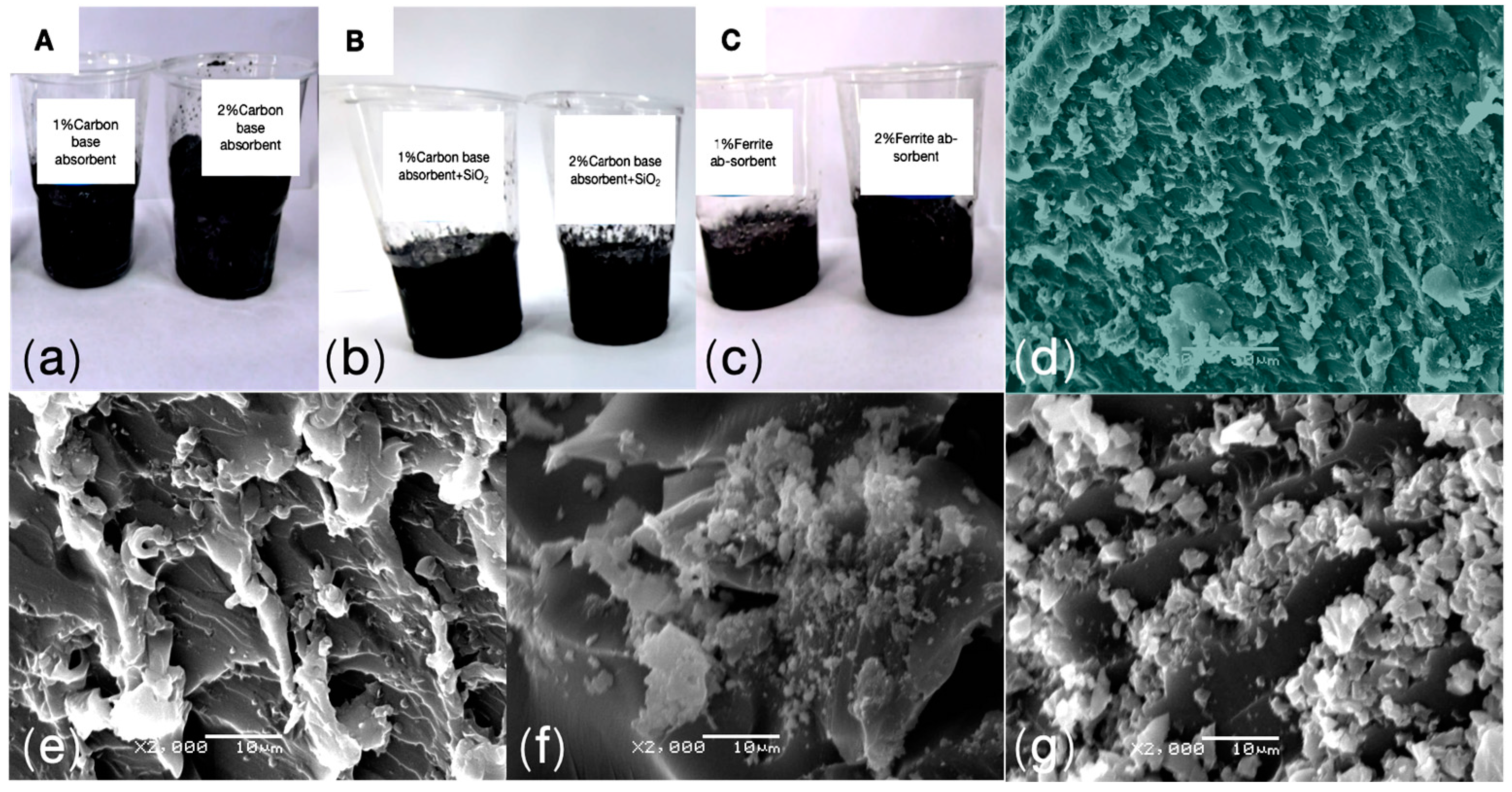

The pore distribution verified through BET reveals the presence of a hierarchical porous structure within the LFAMs (

Figure 3(a)). In the low relative pressure region (P/P₀ < 0.2), the material exhibits an adsorption volume of 110–120 cc/g, indicating the uniform diffusion of CO₂ generated during the reaction and the formation of stable micropores. In the medium relative pressure region (P/P₀ = 0.2–0.8), the adsorption volume gradually increases to 130–140 cc/g, suggesting the presence of abundant mesopores. At high relative pressures (P/P₀ > 0.8), the adsorption volume rises sharply to exceed 150 cc/g, revealing the existence of a certain amount of macropores.

This confirms that the carbon-based absorbers, with their high specific surface area and excellent dispersibility, not only promote bubble nucleation during the nucleation-free foaming process but also provide physical support for bubble expansion [

35]. This facilitates the synergistic optimization of micropores, mesopores, and macropores. The resulting hierarchical porous structure enhances the material's specific surface area and adsorption performance, while also providing pathways for multiple reflections and dissipation of electromagnetic waves [

36].

3.3. Phase Structure and Crystallization Behavior Analysis

The comparative XRD analysis reveals significant differences in diffraction characteristics between samples containing only carbon-based absorbers (LFAMs—A1/2) and those containing both carbon-based absorbers and SiO₂ (LFAMs—B1/2). The diffraction peaks of LFAMs—A1/2 (

Figure 3(b)) around 20° exhibit broad and weak features, indicating that the material is predominantly amorphous. With an increase in the carbon-based absorber content, the diffraction intensity slightly increases, but no significant crystalline signals are observed. In contrast, LFAMs—B1/2 (

Figure 3(b)) show a slight increase in diffraction peak intensity in the same region, but the peak width remains largely unchanged, suggesting that the addition of SiO₂ has limited influence on the ordering of the internal crystalline structure, and the overall phase remains amorphous.

These findings confirm that carbon-based absorbers provide stable support during the nucleation-free foaming process [

37]. The amorphous structure prevents localized stress concentrations that may arise from crystalline phases, enabling a more uniform pore distribution and superior dielectric loss performance. In comparison, the introduction of SiO₂ has a relatively small effect on improving pore uniformity and wave absorption performance. The results demonstrate that incorporating carbon-based absorbers meets the requirements of the nucleation-free foaming process, simplifying the material preparation workflow while achieving efficient structural and performance optimization [

38].

3.4. Chemical Bonding and Foaming Mechanism Study

FT-IR analysis further elucidates the gas-phase nucleation-free foaming mechanism and the reasons for the uniform distribution of pores. After the completion of primary curing, the infrared spectrum (Figure4(b)) shows a broad absorption peak at 3300–3500 cm⁻¹ corresponding to the stretching vibrations of -NH groups, while the peaks at 1500–1700 cm⁻¹ are attributed to the C=O bonds in carboxylates. These characteristic absorption peaks clearly confirm the nucleophilic attack of the nitrogen atom in amines on the electrophilic carbon atom in carbon dioxide, leading to the formation of carbamate intermediates [

39]. The resulting carbamates are further stabilized through hydrogen bonding and act as micro-scale nucleation sites in the nucleation-free foaming system, significantly promoting the uniform generation and distribution of bubbles [

40].

The study further controls gas release and bubble expansion through secondary curing. At this stage, carbon-based or ferrite absorbers are introduced. These absorbers exhibit a high specific surface area and molecular-level chemical activity, with their surfaces serving as sites for CO₂ accumulation and initial nucleation, thereby reducing the activation energy for bubble formation. As the temperature increases to 80°C, ammonium salts begin to decompose, releasing CO₂, and the bubbles gradually expand to form a hierarchical porous structure. During this process, the synergistic effects of gas release rate and changes in matrix viscosity ensure controlled bubble growth, preventing bubble coalescence or rupture. Additionally, the absorbers are uniformly distributed within the pore walls, enhancing the mechanical stability of the material and significantly improving its broadband wave absorption performance through increased dielectric and magnetic losses. The bidirectional reaction of carbamates is as follows:

3.5. Electromagnetic Parameters and Wave Absorption Performance Testing

3.5.1. Analysis of Dielectric Constant and Loss

To verify the functional integration of mesoporous structures with wave absorption performance, this study measured the electromagnetic parameters of LFAMs, including complex permittivity (

εr = ε’ – jε’’) and complex permeability (

μr = μ’– jμ’’), using a vector network analyzer. Additionally, the dielectric loss tangent (

tan δε), magnetic loss tangent (

tan δμ), and reflection loss (

RL) were calculated. The calculation formulas are as follows [

41]:

where

Zin is the input impedance,

Z0 is the impedance of free space,

f is the frequency of EMW,

d is the thickness of the material, and

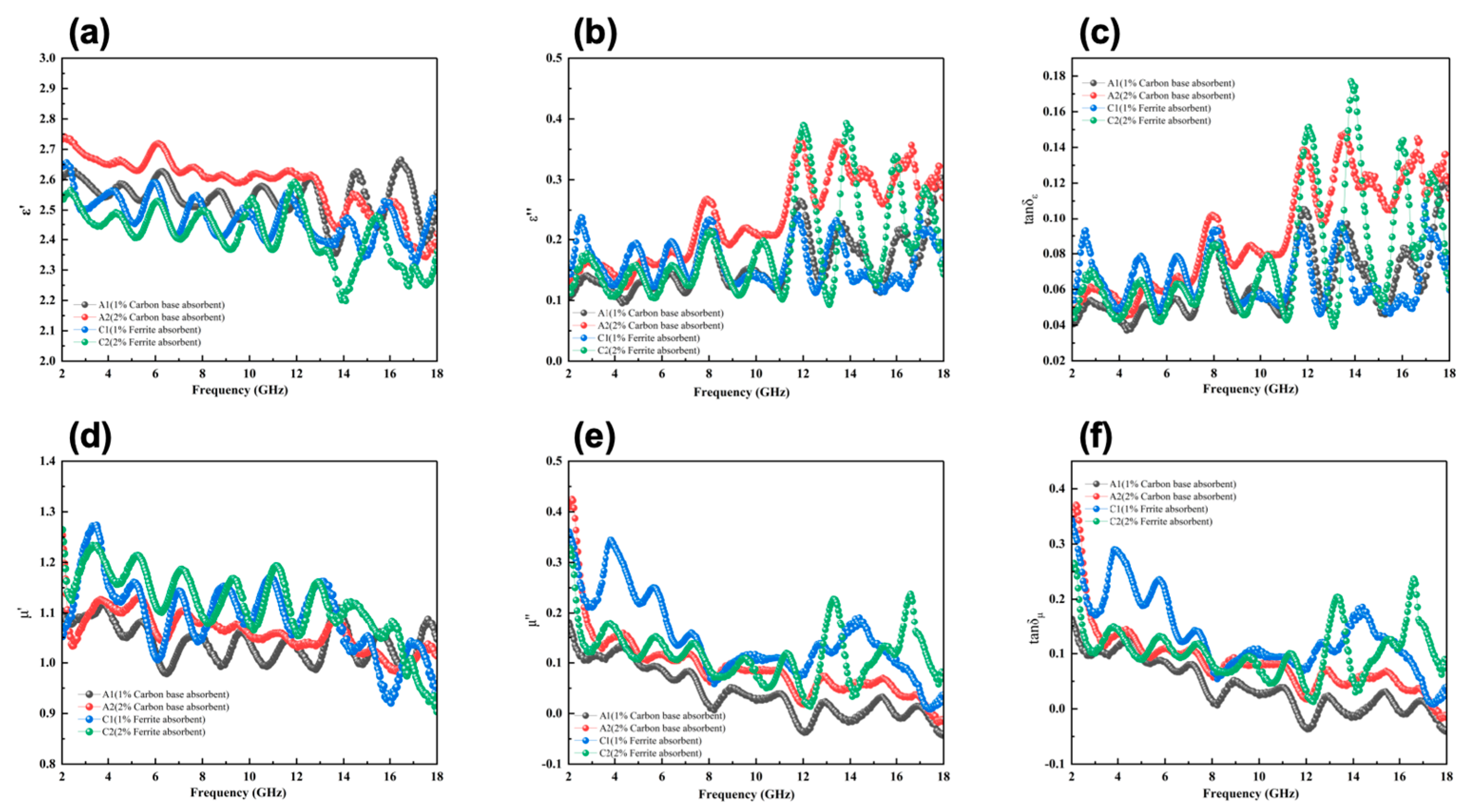

c is the speed of light. In the high-frequency range (12–18 GHz), carbon-based absorbers significantly enhance the dielectric constant and loss performance of the composite material. The real part of the dielectric constant (ε’) (

Figure 5(a)) increases from 2.5 to 2.7 with the addition of carbon-based absorbers, while the imaginary part (ε’’) (

Figure 5(b)) reaches 0.35 in the high-frequency range, indicating that interfacial polarization and enhanced conductive networks play a key role in the performance of carbon-based absorbers. In contrast, the dielectric response of ferrite absorber composites is more concentrated in the mid-to-low frequency range (8–12 GHz), where the real part of the dielectric constant remains (

Figure 4(a)) between 2.4 and 2.6, and the imaginary part peaks at approximately 0.3 (

Figure 5(b)), reflecting the contribution of ferrite to low-frequency dielectric loss and interfacial polarization. Overall, carbon-based absorbers are more suitable for high-frequency electromagnetic wave absorption, while ferrite absorbers provide stronger support for mid-to-low frequency absorption performance.

The dielectric loss (tan δ

ε) further illustrates the influence of different absorbers on the dielectric performance of the materials (

Figure 5(c)) . Carbon-based absorbers exhibit higher dielectric loss in the high-frequency range, with the tan δ

ε peak value of 2 wt% carbon-based absorbers (LFAMs—A2) reaching approximately 0.15, compared to 0.10 for the 1 wt% sample (LFAMs—A1). This indicates that increasing the carbon-based content significantly optimizes the conductive network and microporous structure, thereby enhancing high-frequency absorption capability. In contrast, ferrite absorbers demonstrate superior dielectric loss characteristics in the mid-to-low frequency range (8–12 GHz), with the tan δ

ε peak of 2 wt% ferrite absorbers (LFAMs—C2) reaching approximately 0.12, compared to 0.08 for the 1 wt% sample (LFAMs—C1). This improvement in loss capacity highlights the effectiveness of ferrite absorbers in supporting mid-to-low frequency wave absorption and further broadening the absorption bandwidth of the material.In summary, carbon-based materials are dominated by dielectric loss in the high-frequency range, with supplementary high-frequency magnetic responses enhancing their absorption performance. Conversely, ferrite materials are primarily driven by magnetic loss in the mid-to-low frequency range, with secondary dielectric loss mechanisms contributing to broader electromagnetic wave absorption [

42].

3.5.2. Permeability and Loss Analysis

In the mid-to-low frequency range (8–14 GHz), ferrite absorbers significantly enhance the magnetic permeability of the material. The real part of the magnetic permeability (μ ‘) increases from 1.1 for LFAMs—C1 to 1.2 for LFAMs—C2 (

Figure 4(d)) , indicating a stronger magnetic response. The imaginary part of the magnetic permeability (μ’‘) also performs exceptionally in the mid-frequency range, with LFAMs—C2 reaching a peak of approximately 0.2 in the 10–12 GHz range, significantly higher than C1's 0.15 and the carbon-based absorbers LFAMs—A1/2 (<0.05) (

Figure 5(e)) . This demonstrates that ferrite absorbers effectively enhance the magnetic response of the material through mechanisms such as hysteresis loss, natural resonance, and eddy current loss. Particularly in the mid-to-low frequency range, the magnetic contribution of ferrite absorbers is significantly superior to that of carbon-based absorbers.

The magnetic loss (tan δ

μ) data further validate the impact of ferrite absorbers on the material's magnetic loss performance (

Figure 5(f)). Within the 10–14 GHz range, the tan δ

μ of LFAMs—C1 is 0.08, while LFAMs—C2 increases to 0.12, indicating that higher ferrite content enhances the hysteresis loss and eddy current loss capabilities [

43]. In contrast, the magnetic loss (tan δ

μ) of carbon-based absorbers remains relatively low across the frequency range, with LFAMs—A1/A2 showing slight increases in the high-frequency region (~15 GHz), peaking at 0.015 and 0.02, respectively. This indicates that the magnetic loss mechanism of carbon-based absorbers is primarily derived from eddy current effects.In summary, ferrite absorbers exhibit superior wave absorption performance in the mid-to-low frequency range due to higher real and imaginary magnetic permeability as well as stronger magnetic loss capabilities.

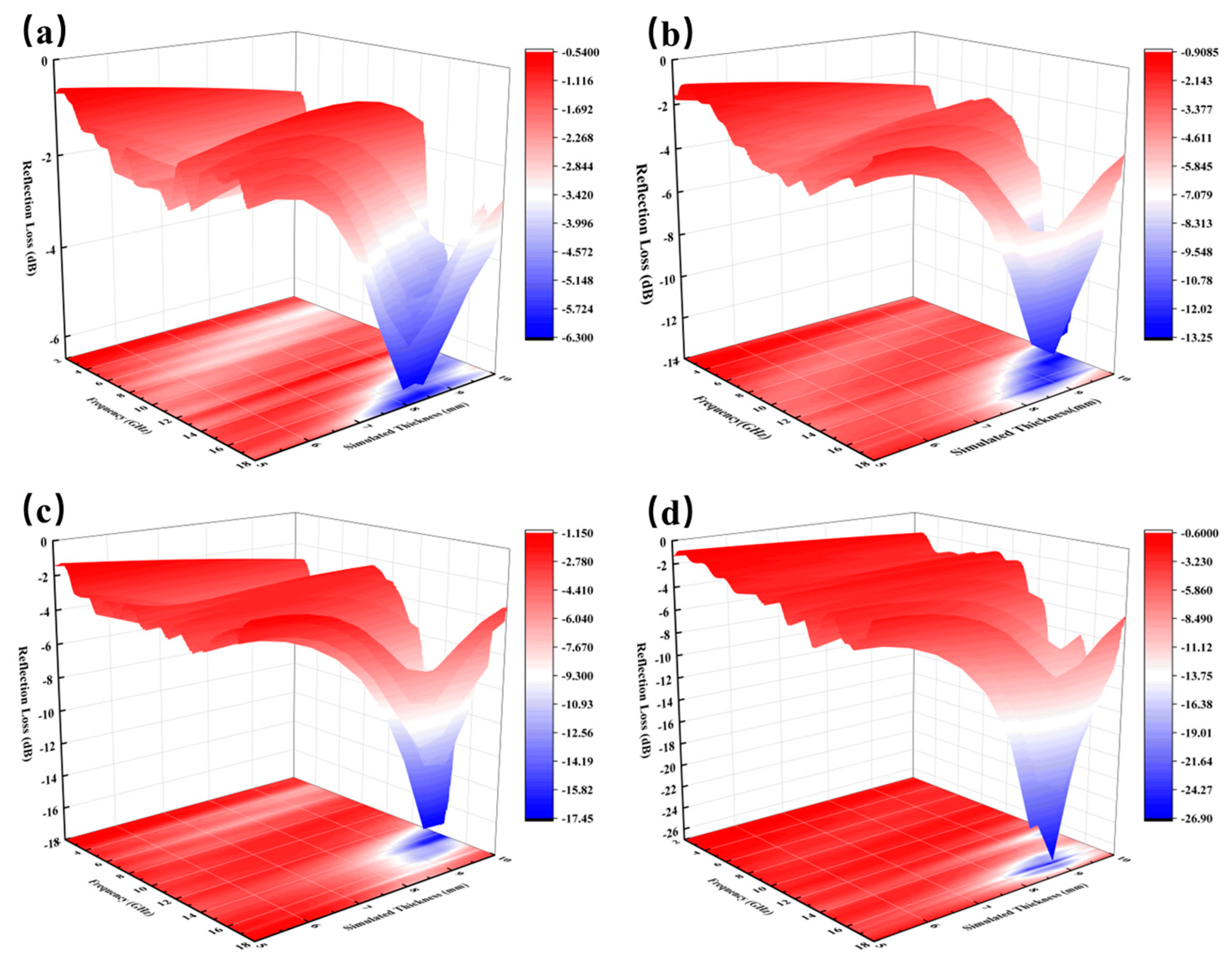

3.5.3. Reflection Loss and Wave Absorption Performance

The analysis of reflection loss further highlights the synergistic mechanism among dielectric loss, magnetic loss, and the porous structure, clarifying the regulation of material microstructure on performance. For the sample with 1.0 wt% carbon-based absorbers (LFAMs-A1), the minimum reflection loss reaches -6.3 dB at around 17 GHz (

Figure 6(a)), mainly driven by interfacial polarization effects and limited conductive loss mechanisms [

44]. Due to the low carbon content, the conductive network is not fully formed, resulting in restricted dielectric loss capacity and weaker absorption performance in the high-frequency range. However, the uniform porous structure constructed by the nucleation-free foaming process provides a solid foundation for bubble distribution and pore wall uniformity, allowing the absorbers to disperse homogeneously. This ensures effective interfacial polarization even with a limited absorber content. As the carbon content increases to 2.0 wt% (LFAMs-A2), the minimum reflection loss decreases to -13.25 dB, and the effective absorption bandwidth (EAB) expands to 13–17 GHz (

Figure 6(b)). The higher carbon content further enhances the formation of the conductive network, strengthens dielectric loss capacity, and optimizes impedance matching, ensuring efficient absorption of electromagnetic wave energy in the high-frequency range.

For the ferrite-based composite absorbers (LFAMs-C1/2), the magnetic loss mechanism is particularly prominent in the mid-to-low frequency range. For the sample with 1.0 wt% ferrite (LFAMs-C1), the minimum reflection loss reaches -17.45 dB at around 14 GHz, and the effective absorption bandwidth (EAB) extends to 13–17 GHz (

Figure 6(c)), exhibiting excellent mid-frequency absorption performance. This is mainly driven by the synergistic effects of magnetic hysteresis loss and eddy current loss. At this stage, the high specific surface area of the absorbers, combined with the porous structure, reduces the activation energy for bubble formation, further enhancing eddy current loss and interfacial polarization effects. When the ferrite content increases to 2.0 wt% (LFAMs-C2), the minimum reflection loss further decreases to -26.83 dB at around 16.6 GHz, while the effective absorption bandwidth (EAB) extends significantly to 12–18 GHz (

Figure 6(d)). This substantial improvement is attributed to the uniform distribution of the absorbers within the pore walls, which enhances the synergistic effects of magnetic hysteresis loss, eddy current loss, and natural resonance loss [

45]. Meanwhile, the gas-controlled release mechanism during the nucleation-free foaming process ensures uniformity in the porous structure, preventing bubble coalescence or rupture, further optimizing the matching of complex magnetic permeability and complex permittivity.

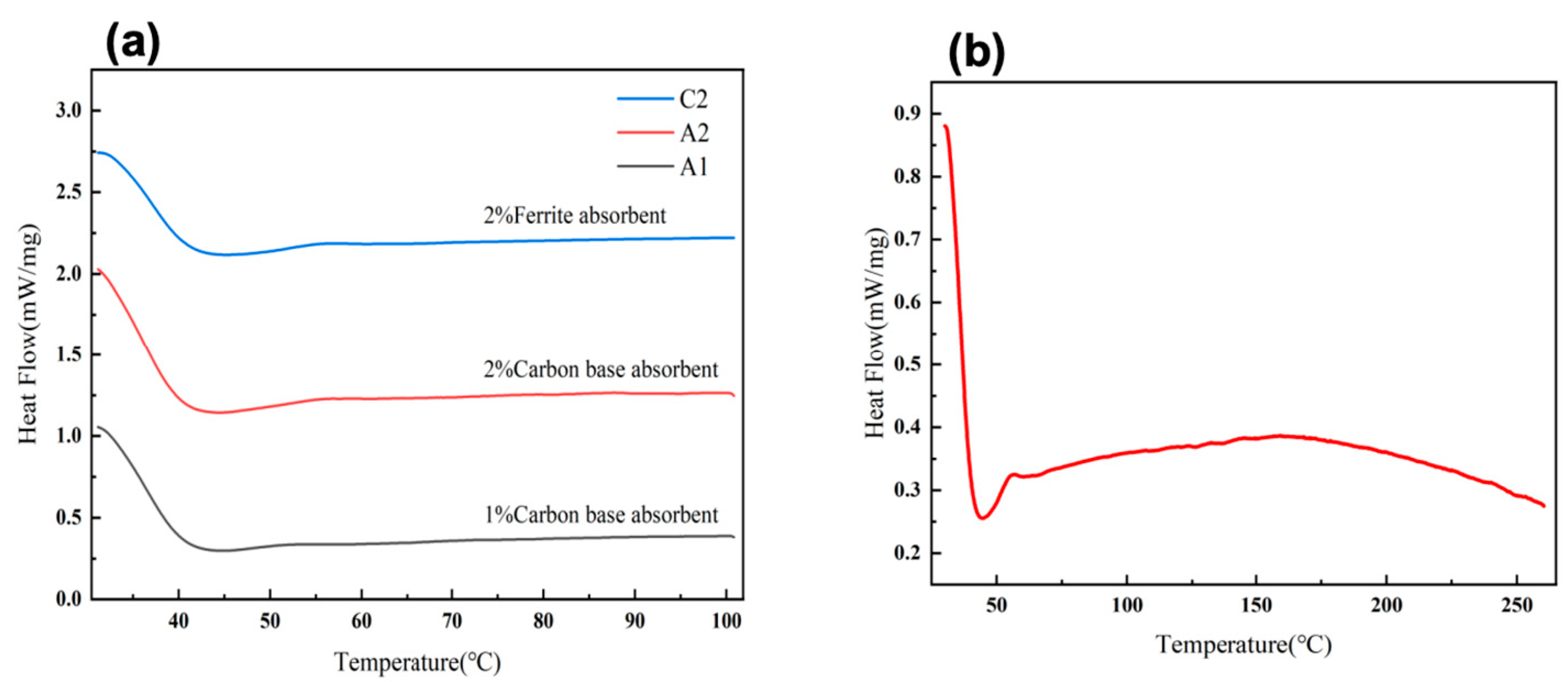

3.6. Thermal Stability Analysis

The carbon-based absorber composite epoxy foam material exhibits stable thermal effects in the temperature range of 30°C to 150°C. The thermal flow of 1.0 wt% and 2.0 wt% carbon-based absorbers (

Figure 7(a)) gradually increases with rising temperature and maintains a high level in the mid-to-high temperature range (100°C to 150°C). This thermal effect is attributed to the high specific surface area and excellent thermal conductivity provided by the foamed epoxy resin, which effectively promotes internal heat conduction and dispersion within the composite material [

46]. Moreover, increasing the carbon-based absorber content further enhances the material's thermal stability and thermal effects, although the enhancement may not be linear. This indicates that carbon-based absorbers possess significant thermal stability and wave absorption performance under high-temperature conditions, making them suitable for applications in wave-absorbing materials requiring stable thermal effects at elevated temperatures.

The ferrite absorber composite epoxy foam material exhibits stable thermal effects in the low to medium temperature range (30°C to 150°C). The thermal flow initially decreases but gradually rises (

Figure 7(a)), forming a plateau between 100°C and 150°C. Within this temperature range, the material demonstrates high thermal stability, with ferrite absorbers effectively stabilizing thermal flow through interfacial interactions with the epoxy matrix. The stability of this plateau region is likely associated with the magnetic loss mechanism, which is the primary wave absorption mechanism of ferrite absorbers.

In the high-temperature range (150°C to 250°C), the thermal flow shows a slow downward trend (

Figure 7(b)). The thermal flow curve indicates that the material retains a certain degree of thermal stability within this temperature range. Based on the continuity of the thermal flow trend, it can be inferred that the internal thermal flow remains relatively uniform. This sustained change in thermal flow suggests that ferrite absorbers continue to participate in the material's heat absorption and dispersion process at high temperatures. Due to the excellent magnetic loss properties of ferrite materials, they can continuously absorb electromagnetic energy through mechanisms such as hysteresis loss and eddy current loss in high-temperature environments.

4. Conclusions

In this study, lightweight epoxy foam electromagnetic wave-absorbing materials were successfully fabricated using a nucleation-free foaming process. The chemical mechanism, microstructure, thermal stability, and wave absorption performance of the materials were systematically analyzed. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) confirmed that a nucleophilic addition reaction between the curing agent, CO₂, and water generates ammonium salts. This reaction, which can be reversed through thermal decomposition, provides chemical evidence for the gas-phase nucleation mechanism. XRD analysis revealed that the materials predominantly exist in an amorphous state, lacking long-range ordered crystalline structures. The addition of carbon-based absorbers slightly influenced the local structure but maintained the amorphous characteristics, thereby avoiding stress concentrations from crystalline phases that could disrupt pore distribution.

The epoxy foam materials exhibited excellent thermal stability, with minimal influence from the type and content of the absorbers, indicating their suitability for high-temperature environments. SEM analysis confirmed the uniform embedding of absorbers within the epoxy matrix. Although the absorbers exhibited weak magnetic properties, their role as nucleating agents was significant, further validating the feasibility of the nucleation-free foaming process. Notably, the addition of 2.0 wt% carbon-based absorbers resulted in the formation of a uniform hierarchical pore structure, with an expansion volume 4.6 times that of the original material, achieving a lightweight design. Furthermore, the epoxy foam material with carbon-based absorbers (LFAMs-A2) exhibited a minimum reflection loss (RL) of -13.25 dB and an effective absorption bandwidth (EAB) of 13–17 GHz. The epoxy foam material with ferrite absorbers (LFAMs-C2) demonstrated exceptional electromagnetic wave absorption performance at 16.6 GHz, with a minimum reflection loss (RL) of -26.83 dB and an effective absorption bandwidth (EAB) of 6 GHz, covering the Ku band.

In summary, this study successfully developed a lightweight, thermally stable, and highly efficient electromagnetic wave-absorbing epoxy foam material through a nucleation-free foaming process. The synergistic effects of carbon-based and ferrite absorbers provide a technical foundation for the lightweighting of thicker coatings in applications such as electromagnetic shielding and stealth technologies.

Author Contributions

methodology, T.D., Z.H. and Y.Z.; software, J.Q.; validation, T.D., F.H. and Y.G.; formal analysis, T.D., Z.H. and Z.L.; investigation, Y.Z.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, T.D. and Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, T.D.; writing—review and editing, T.D. and Z.H.; visualization, T.D. and Y.Z.; supervision, Y.H.; project administration, Z.H. and Y.Z.; funding acquisition, Z.H. and T.D.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (SJCX24_1617), the 2024 Jiangsu Province Higher Education Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (202211276005Z), and the Nanjing Institute of Technology "Jiangsu Distinguished Teaching Faculty" Studio Project (3064107224005).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cheng, J.; Li, C.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Raza, H.; Ullah, S.; Wu, J.; Zheng, G.; Cao, Q.; Zhang, D. Recent Advances in Design Strategies and Multifunctionality of Flexible Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Materials. Nano-Micro Letters 2022, 14, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Lu, J.; Yan, X.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Wen, G. Electromagnetic Absorption by Magnetic Oxide Nanomaterials: A Review. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2023, 6, 22611–22634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, D.; Jia, Y.; Xu, J.; Fu, J. High-Performance Microwave Absorption Materials: Theory, Fabrication, and Functionalization. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2023, 62, 14791–14817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Ma, Z.H.; Liang, H.S.; Zhang, L.M.; Wu, H.J. Ferrite-based composites and morphology-controlled absorbers. Rare Metals 2022, 41, 2943–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Kumar, P.; Dubey, A.; Kumar, A. Development of Metamaterial Using Waste Materials for Microwave Absorption. Brazilian Journal of Physics 2024, 54, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, E.; Yan, T.; Ye, X.; Gao, Q.; Yang, C.; Yang, P.; Ye, Y.; Wu, H. Preparation of FeSiAl–Fe3O4 reinforced graphene/polylactic acid composites and their microwave absorption properties. Journal of Materials Science 2023, 58, 11647–11665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen Kumar, M.; Raga, S.; Chetana, S.; Rangappa, D. X-Band Dielectric Characterization and Microwave Absorption Characteristics of Polyaniline Loaded Poly Vinyl Butyral (PVB). Transactions on Electrical and Electronic Materials 2023, 24, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Liang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, P.; Li, D. 3D printed labyrinth multiresonant composite metastructure for broadband and strong microwave absorption. Science China Technological Sciences 2023, 66, 3574–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Wang, D.; Yu, Z.; Zheng, W.; Liu, B.; Zhang, A. The preparation and absorbing properties of controllable porous polymer microspheres @ MWCNTs absorber with lightweight characterization. Journal of Polymer Research 2022, 29, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewdie, F.; Narayan, D.; Srivastava, A.; Bhatnagar, N. Experimental Investigation on Fabrication of Cermet Hollow Spheres for Use as Reinforcement in the Production of Lightweight and Strong Metal Foams for High Energy Absorption Applications. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Wang, X.; Pan, F.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, H.; Cai, L.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, L. State of the art recent advances and perspectives in 2D MXene-based microwave absorbing materials: A review. Nano Research 2023, 16, 10287–10325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, K.K.; Satapathy, A.; Mahimkar, K.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Kaur, A.; Kandasubramanian, B.; Raj, A.A.B. Recent Advances in MXene Nanocomposites as Electromagnetic Radiation Absorbing Materials. Journal of Electronic Materials 2023, 52, 3576–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Cui, C.; Bai, W.; Tang, H.; Guo, R. Building of lightweight Nb2CTx MXene@Co nitrogen-doped carbon nanosheet arrays@carbon fiber aerogels for high-efficiency electromagnetic wave absorption in X and Ku bands inspired by sea cucumber. Nano Research 2024, 17, 9261–9274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Z.; Xie, P.; Alshammari, A.S.; El-Bahy, S.M.; Ren, J.; Liang, G.; He, M.; El-Bahy, Z.M.; Zhang, P.; Liu, C. Magnetic metal-based MOF composite materials: a multidimensional regulation strategy for microwave absorption properties. Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials 2024, 7, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Zhao, B.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, M.; Guo, Z. MOF-derived porous hollow Ni/C composites with optimized impedance matching as lightweight microwave absorption materials. Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials 2021, 4, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, T.; Sadhana, K.; Praveena, K. Enhanced microwave absorbing properties of manganese zinc ferrite: polyaniline nanocomposites. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 2023, 34, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Najafi Moghadam, P.; Nazarzadeh Zare, E.; Norinia, J. Poly(aniline-co-melamine)/polyurethane coating as a novel microwave absorbing material for potential stealth application. Iranian Polymer Journal 2024. [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Yang, Y.; Liu, W.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, J. Recent advance in three-dimensional porous carbon materials for electromagnetic wave absorption. Science China Materials 2022, 65, 2911–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, K. KGM Derived CNTs Foam/Epoxy Composites with Excellent Microwave Absorbing Performance. Journal of Wuhan University of Technology-Mater. Sci. Ed. 2022, 37, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, B.; Lv, X. Robust PU foam skeleton coated with hydroxylated BN as PVA thermal conductivity filler via microwave-assisted curing. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 2021, 32, 27524–27533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Jin, S.; Zou, H.; Li, L.; Ma, X.; Lv, G.; Gao, F.; Lv, X.; Shu, Q. Polymer-based lightweight materials for electromagnetic interference shielding: a review. Journal of Materials Science 2021, 56, 6549–6580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, P.Y.; Peng, H.L.; Hou, Z.L.; Hu, P.; Liu, L.M.; Wang, G.-S. Interface-induced dual-pinning mechanism enhances low-frequency electromagnetic wave loss. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; Wang, J.; Li, J.Y.; Feng, J.; He, W.T.; Guo, H.-B. Pseudo-binary composite of Sr2TiMoO6–Al2O3 as a novel microwave absorbing material. Rare Metals 2024. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, S.K.; Kumar, A.; Das, B. Influence of Reduced Graphene Oxide Flakes Addition on the Electromagnetic Wave Absorption Performance of Silicon Carbide-Based Wave Absorber. JOM 2024, 76, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Ma, Z.; Ding, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, C. Synergistic effect and heterointerface engineering of cobalt/carbon nanotubes enhancing electromagnetic wave absorbing properties of silicon carbide fibers. Nano Research 2024, 17, 8479–8486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.S.; Zhu, J.P.; Song, Z.; Ren, Q.G.; Feng, T.; Zhang, Q.T.; Wang, L.X. Multispectral ErBO3@ATO porous composite microspheres with laser and electromagnetic wave compatible absorption. Rare Metals 2023, 42, 2406–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.J.; Liu, P.B.; Chen, W.X. Two-Dimensional Metal Organic Framework derived Nitrogen-doped Graphene-like Carbon Nanomesh toward Efficient Electromagnetic Wave Absorption. Journal of colloid and interface science 2023, 643, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.H.; Liu, W.D.; Sun, B.Z. Electromagnetic Wave-Absorbing and Bending Properties of Three-Dimensional Honeycomb Woven Composites. Polymers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Guo, Q.Y.; Wang, L.C.; Xu, H. Evaluation of Compression Performance of APM Aluminum Foam-Polymer Filled Pipes Prepared via Different Epoxy Resin Bonding Processes. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.J.; Tian, Y.R.; Peng, X.W. Applications and Challenges of Supercritical Foaming Technology. Polymers 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Yin, S.; Duvigneau, J.; Vancso, G.J. Bubble Seeding Nanocavities: Multiple Polymer Foam Cell Nucleation by Polydimethylsiloxane-Grafted Designer Silica Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 1623–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.M.; Huang, H.; Wu, S.B.; Wang, J.F.; Lu, H.J.; Xing, L.Y. Study on Microwave Absorption Performance Enhancement of Metamaterial/Honeycomb Sandwich Composites in the Low Frequency Band. Polymers 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zeng, L.; Bie, S.; Jiang, J. The design and preparation of a 3D microwave absorber based on carbon black-filled epoxy resin for X-band application. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 2023, 34, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Zeng, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, B.; Lin, J.; Tan, L.; Liang, L. Functionalized mesoporous silica liquid crystal epoxy resin composite: an ideal low-dielectric hydrophobic material. Journal of Materials Science 2022, 57, 1156–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Khanna, R.; Rai, M.K.; Narang, S.B. An Improved Biodegradable Microwave Absorber Based on Peanut Shell Mixed with Metal Free Carbon Nanotube for Ku-Band. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2024, 15, 2273–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, S.; Chen, Y. Structure construction and wave-absorbing properties of mesoporous hollow carbon microspheres. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 2023, 34, 2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanth, S.; Injeti, N.K.; Rao, V.N.B.; Santhosi, B.V.S.R.N. Influence of MWCNTs addition on the electromagnetic absorption performance of polymer-based wave absorber. Nanotechnology for Environmental Engineering 2024, 9, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Fabrication magnetic composite scaffolds with multi-modal cell structure for enhanced properties using supercritical CO2 two-step depressurization foaming process. Polymer Bulletin 2024, 81, 5627–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- chikawa, Y.; Kaneno, D.; Saeki, N.; Minami, T.; Masuda, T.; Yoshida, K.; Kondo, T.; Ochi, R. Protecting group-free method for synthesis of N-glycosyl carbamates and an assessment of the anomeric effect of nitrogen in the carbamate group. carbohydrate research 2021, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.J.; Li, T.H.; Li, H.; Dang, A.L. Effect of Graphene on Graphitization, Electrical and Mechanical Properties of Epoxy Resin Carbon Foam. Journal Of Inorganic Materials 2024, 39, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.X.; Wang, H.W.; Ma, J.; Lin, Z.T.; Wang, C.J.; Li, X.; Ma, M.L.; Li, T.X.; Ma, Y. Fabrication of hollow Ni/NiO/C/MnO2@polypyrrole core-shell structures for high-performance electromagnetic wave absorption. Composites Part B: Engineering 2024, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Dai, J.; Huang, D.; Yu, R. Effect of nitrogen-doped reduced graphene oxide on the wave-absorbing properties of hollow ZnFe2O4. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 2024, 35, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, T.; Sadhana, K.; Praveena, K. Enhanced microwave absorbing properties of manganese zinc ferrite: polyaniline nanocomposites. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 2023, 34, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Sheng, D.; Mukherjee, S.; Dong, W.; Huang, Y.; Cao, R.; Xie, A.; Fischer, R.A.; Li, W. Carbon nanolayer-mounted single metal sites enable dipole polarization loss under electromagnetic field. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 9077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Gotra, S.; Singh, D.; Varma, G.D. Translating Electronic Waste Materials into Microwave Absorbing Materials: A Critical Analysis. Journal of Electronic Materials 2024, 53, 5580–5595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.J.; Li, T.H.; Li, H.; Dang, A.L. Microstructure, electrical conductivity and mechanical properties of graphitization carbon foam derived from epoxy resin modified with coal tar pitch. Carbon Letters 2024, 34, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).