1. Introduction

In recent years, the demand for orthodontic treatments with aesthetic appliances has increased exponentially, leading to the widespread adoption of clear aligner therapy (CAT). Clear aligners also offer several advantages over traditional fixed orthodontic appliances, including enhanced comfort, reduced frequency of emergencies, improved oral hygiene, and minimized soft tissue irritation [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

Numerous studies have consistently confirmed that CAT has emerged as a viable alternative to conventional orthodontic therapy. It is particularly effective in treating mild to moderate malocclusions in non-growing patients who do not require extractions.[

7] However, while CAT has demonstrated efficacy in various tooth movements, certain limitations persist. According to the scoping review by Muro MP et al. [

8] and other studies [

9], CAT has been shown to be particularly effective for buccolingual tipping but less predictable for rotational, intrusive, and extrusive movements. Moreover, while CAT has been shown to be effective for mild to moderate crowding resolution, the success of overbite correction still seems to be limited.

Dentoalveolar expansion is another movement where CAT has demonstrated effectiveness, although it is mainly achieved through posterior tooth tipping movement [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Arch expansion can be used to resolve mild to moderate crowding, to increase the width of the smile or to correct certain crossbites of dentoalveolar origin [

17,

18,

19,

20]. The systematic review by Ma el al. [

21] on the clinical outcome of arch expansion with CAT concluded that in the maxilla, the expansion rate decreases from the anterior to the posterior, with the highest efficacy observed in the premolar area. Although predictability is reasonable for expansion movements, published data indicate that arch expansion is not completely predictable. Despite variations in the methods used to quantify the predictability of expansion movement among the published papers, it ranges from 65.2 % (for the maxillary second molar crown) [

10] to 93.53% (for the maxillary first premolar) [

14]. To address this limitation, overcorrection of movements is widely recommended at the virtual planning stage [

10,

13,

15,

21]. However, some patients may still require case refinement, mid-course correction, or conversion to fixed appliances before the end of treatment [

22]. Additionally, some authors consider that CAT might not be as effective as braces in increasing the transverse dimension. [

23,

24,

25]

In this study, a novel treatment modality, Geniova TechnologiesTM (GT) (developed by Geniova Technologies, SL, Madrid, Spain), which combines CAT and braces, is tested with the aim of maintaining the advantages of both devices, while reducing their limitations. Specifically, GT can be described as a hybrid aligner that includes virtual brackets and nickel titanium arch wires, and combines principles of conventional orthodontics fixed appliances with the characteristics of CAT. GT comprises components and properties that differ from those of a conventional clear aligner, despite operating in a similar manner and involving patient interaction. This hybrid system operates in distinct treatment phases, utilizing the hybrid aligner in the initial stages and transitioning to conventional aligners in the subsequent phases until treatment completion. This system is designed to accelerate certain dental movements during the early phases of CAT.

The aims of the present study were twofold: firstly, to evaluate the efficacy of GT for arch expansion; and secondly, to assess the predictability of GT virtual setup measurements compared to conventional CAT at the end of the first treatment phase.

2. Materials and Methods

This prospective clinical study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos de Madrid (internal code 19/294-R_P Tesis; date of approval: 23 July 2019), and all patients provided written informed consent to participate. The manuscript was prepared following the recommendations for reporting clinical case series studies [

26].

Sample Selection

Patients attending the private orthodontic clinic of one of the authors were enrolled in the study if they met the following eligibility criteria. Inclusion criteria were: Adult subjects (≥ 21 years), presence of dentoalveolar compression of the maxillary arch, presence of maxillary anterior crowding > 3 mm, absence of missing teeth (excluding wisdom teeth), need for orthodontic expansion and orthodontic treatment of both arches lasting more than 6 months, no scheduled dental extraction, willingness to be treated using clear aligners, and cooperative patients. Exclusion criteria were: Presence of craniofacial syndrome, systemic disease, periodontal disease, TJM disorders, subjects undergoing treatment with NSAIDs, bisphosphonates, or phenytoin, reported previous orthodontic treatment, and need for treatment requiring therapeutic dental extraction or orthognathic surgery.

After a thorough explanation of the study and according to the patients’ preferences, selected patients were assigned to one of two groups based on the treatment modality to be applied: GT group, and conventional clear aligner group.

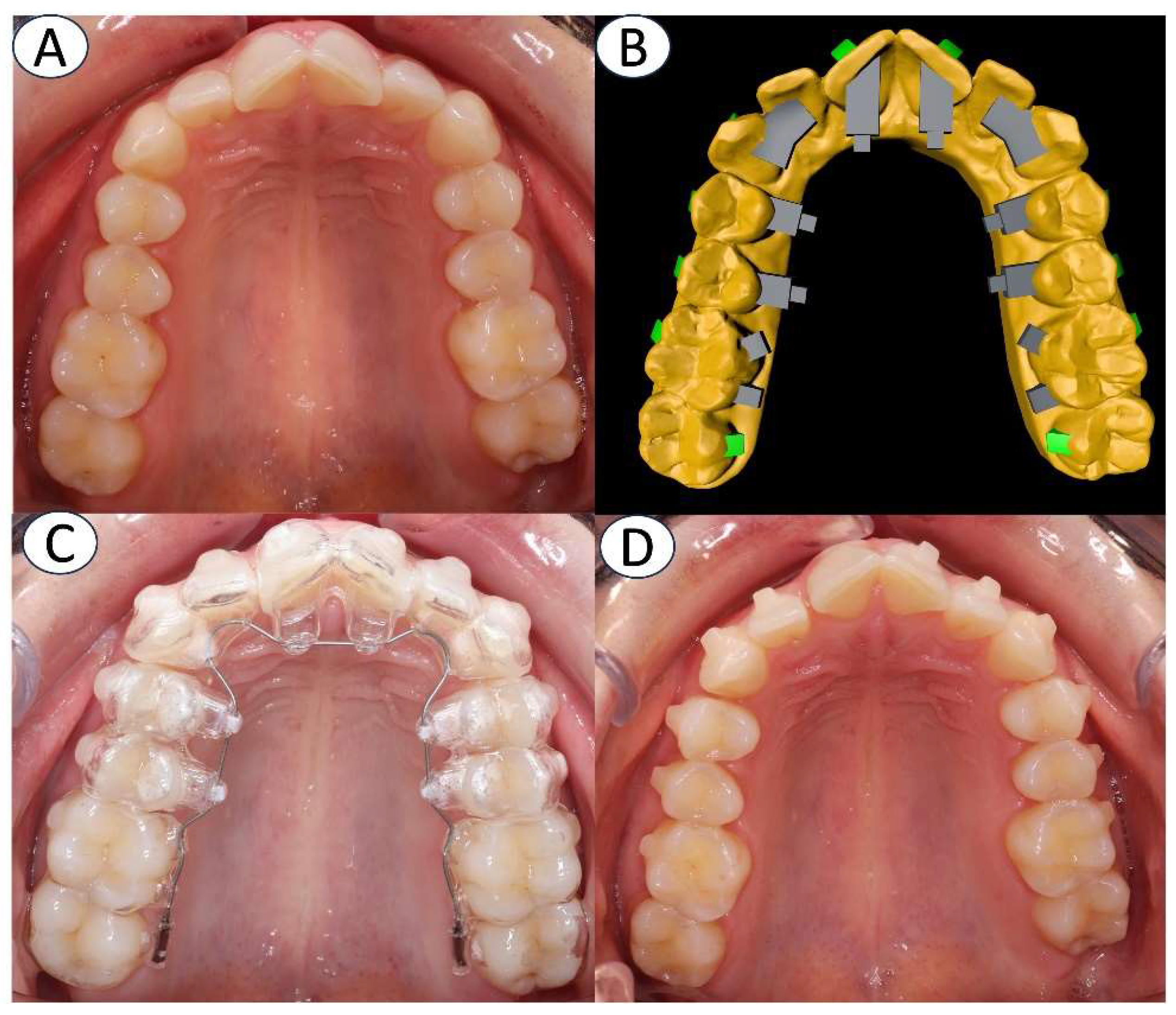

GT Group

This group was treated with the GT system with the aim of creating expansion in the posterior sectors (canines and premolars). Every hybrid aligner was worn for 4 weeks. Treatment planning was completed using a 3D virtual visualization developed by GT Company.

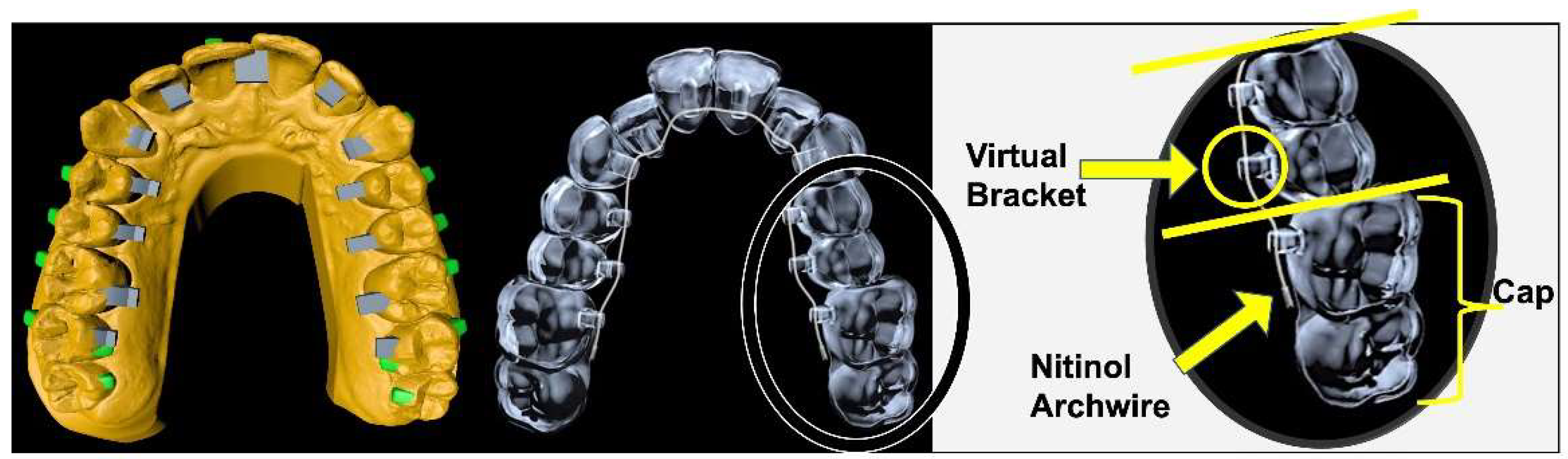

The hybrid aligners consist of the following components,

Figure 1 and

Figure 2: Caps, which are aligner segments that may encompass one or more teeth, containing intrinsic information of virtual brackets and attachments tailored to the tooth anatomy; Virtual Brackets, digitally designed lingual brackets composed of a pyramidal base and a rectangular prism, with customized size and position; and Nickel Titanium (NiTi) Archwires, standard 0.014’’ nickel titanium archwires with a round cross-section that provide smooth and continuous forces. This biomechanical component is directly linked to the virtual bracket and provides varying deflection and force to facilitate the planned tooth movements.

Clear Aligner Group

This group was treated using the Invisalign® clear aligner system (Align Technology, San José, CA, USA), fabricated with SmartTrack™ material, with the aim of creating expansion in the posterior sectors. Every aligner was worn for 10 days. Treatment planning was completed using the ClinCheck® virtual model.

Measurements

Intraoral scans were taken for every patient using the TRIOS scanner (3Shape, Copenhagen, Denmark), generating three digital models: Pre-treatment (T1), outcome predicted by the planning software (T2), and post-treatment (T3). Analysis of dental movements was conducted through dental superimpositions using the protocols developed by Choi et al. [

27] and Cha et al. [

28], where the region of palatal rugae on the hard palate was aligned, and points on the teeth where no movement occurred could also be selected.

The following measurements were recorded in mm at each time point: upper and lower intercanine widths, inter-first premolar, and inter-second premolar widths, both at the vestibular cusps and at middle lingual gingival level. All measurements were performed using OrthoAnalyzer 1.7 analytical software (3Shaphe, Copenhagen, Denmark).

The effectiveness of expansion was assessed by calculating the percentage of width achieved by treatment (T3-T1 %). The predictability of expansion was assessed by calculating the percentage of the observed expansion relative to the predicted expansion (T3-T1 x 100 / T2-T1).

Statistical Analysis

Sampling was conducted by non-probabilistic recruitment of consecutive cases. The sample size was estimated to detect effects greater than 1.06 mm (bilateral test), based on the expansion study by Nogal-Coloma et al. [

13], with a significance level of

p ≤ 0.05 and a minimum power of 20%, resulting in a sample size of 18 patients per group. The sample was increased to 20 patients per group to account for possible losses to follow-up.

To test the intra-rater reliability, 5 cases were randomly selected and measured twice. The measures were compared using the interclass correlation coefficient (ICC). For each variable analyzed, mean values and 95% confidence intervals were calculated after confirming that the outcomes met the assumption of normality. The analysis compared baseline measurements, treatment duration, number of aligners used, and dental expansion between the two treatment groups using an independent T-test. Statistical significance was set at p≤0.05.

Furthermore, the Variance Ratio test was utilized to explore the relationship between planned changes in tooth positions and the accuracy of the final outcomes. This analysis helped in understanding whether larger planned changes were associated with greater inaccuracies.

3. Results

The ICC values were higher than 0.92 for all measurements, indicating that the measurements were reliable.

3.1. Patient Characteristics (Table 1)

The GT group was comprised of 20 patients, 5 male and 15 female, and the CA group consisted of 20 patients, 9 male and 11 female.

Average treatment duration (4.25 months for GT group, and 9.42 months for CA group), number of aligners used (4.25 in GT group vs. 28.25 aligners in CA group), and age (31.3 years in GT group vs. 38.45 years in CA group) showed significant differences between groups (p<0.001) No significant differences in transverse dimensions were found between groups at the beginning of the study.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline (T0) measurements between GT (Geniova) and CA (clear aligner) groups. Tx: treatment; SD: Standard deviation; Diff: difference; CI: confidence interval; sig: significance; 13_23: upper canines; 14_24: upper first premolars; 15_25: upper second premolars; 33_43: lower canines; 34_44: lower first premolars; 35_55: lower second premolars; cusp: cuspid level; cerv: cervical level.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline (T0) measurements between GT (Geniova) and CA (clear aligner) groups. Tx: treatment; SD: Standard deviation; Diff: difference; CI: confidence interval; sig: significance; 13_23: upper canines; 14_24: upper first premolars; 15_25: upper second premolars; 33_43: lower canines; 34_44: lower first premolars; 35_55: lower second premolars; cusp: cuspid level; cerv: cervical level.

| |

GT |

CA |

|

95%CI |

|

| Outcome |

Mean GT |

SD GT |

Mean CA |

SD CA |

Mean Diff |

Upper |

Lower |

p (sig) |

| AGE (Years) |

31.30 |

5.51 |

38.45 |

8.77 |

7.15 |

11.84 |

2.46 |

0.000 |

| Tx Duration (months) |

4.25 |

0.72 |

9.42 |

2.17 |

5.16 |

6.56 |

4.44 |

0.000 |

| Number Aligners |

4.25 |

0.72 |

28.25 |

10.20 |

24.00 |

28.78 |

19.22 |

0.000 |

| T0_13_23_cusp (mm) |

33.10 |

2.98 |

31.77 |

2.01 |

-1.33 |

0.29 |

-2.96 |

0.105 |

| T0_14_24_cusp (mm) |

38.74 |

2.69 |

37.60 |

2.70 |

-1.14 |

0.61 |

-2.90 |

0.194 |

| T0_15_25_cusp (mm) |

43.73 |

3.01 |

42.97 |

3.11 |

-0.76 |

1.22 |

-2.75 |

0.440 |

| T0_13_23_cerv (mm) |

23.27 |

2.01 |

2.01 |

2.01 |

-0.87 |

0.39 |

-2.13 |

0.169 |

| T0_14_24_cerv (mm) |

25.42 |

1.95 |

24.69 |

2.09 |

-0.73 |

0.58 |

-2.04 |

0.266 |

| T0_15_25_cerv (mm) |

30.44 |

2.36 |

29.79 |

2.50 |

-0.66 |

0.92 |

-2.23 |

0.405 |

| T0_33_43_cusp (mm) |

23.55 |

6.76 |

25.21 |

1.49 |

1.76 |

4.81 |

-1.50 |

0.293 |

| T0_34_44_cusp (mm) |

32.25 |

3.07 |

30.97 |

2.47 |

-1.28 |

0.63 |

-3.18 |

0.182 |

| T0_35_45_cusp (mm) |

36.85 |

2.93 |

36.14 |

3.49 |

-0.71 |

1.56 |

-2.98 |

0.531 |

| T0_33_43_cerv (mm) |

18.98 |

2.26 |

18.34 |

1.58 |

-0.64 |

0.77 |

-2.05 |

0.358 |

| T0_34_44_cerv (mm) |

24.32 |

2.00 |

23.48 |

1.75 |

-0.84 |

0.45 |

-2.13 |

0.196 |

| T0_35_45_cerv (mm) |

27.93 |

2.09 |

27.48 |

2.78 |

-0.45 |

1.29 |

-2.20 |

0.601 |

3.2. Comparison of Dental Changes Between the Two Groups

After treatment, an independent samples t-test was conducted to compare dental changes achieved between the two groups. While the majority of variables showed no significant differences, significant changes were identified in specific areas of the lower arch: in the cusps between second premolars (mean difference: 1.50 mm, p = 0.016), favoring the CA group; and in the cervical regions between teeth first premolars (mean difference: 1.00 mm, p = 0.008), and second premolars (mean difference: 1.13 mm, p = 0.010), where the CA group exhibited greater expansion compared to the GT group too.

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline (T0) measurements between GT (Geniova) and CA (clear aligner) groups. Tx: treatment; SD: Standard deviation; Diff: difference; CI: confidence interval; sig: significance; 13_23: upper canines; 14_24: upper first premolars; 15_25: upper second premolars; 33_43: lower canines; 34_44: lower first premolars; 35_55: lower second premolars; cusp: cuspid level; cerv: cervical level.

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline (T0) measurements between GT (Geniova) and CA (clear aligner) groups. Tx: treatment; SD: Standard deviation; Diff: difference; CI: confidence interval; sig: significance; 13_23: upper canines; 14_24: upper first premolars; 15_25: upper second premolars; 33_43: lower canines; 34_44: lower first premolars; 35_55: lower second premolars; cusp: cuspid level; cerv: cervical level.

| |

GT |

CA |

Mean Dif |

95%CI |

p (sig) |

| Outcome |

Mean GT |

SD GT |

Mean CA |

SD CA |

Upper |

Lower |

| Real_13_23_cusp |

1.60 |

2.20 |

1.02 |

1.09 |

-0.58 |

0.54 |

-1.70 |

0.298 |

| Real_14_24_cusp |

2.78 |

2.03 |

2.44 |

1.40 |

-0.35 |

0.77 |

-1.46 |

0.533 |

| Real_15_25_cusp |

2.45 |

1.71 |

2.42 |

1.81 |

-0.03 |

1.09 |

-1.16 |

0.950 |

| Real_13_23_cerv |

0.88 |

1.25 |

0.96 |

0.82 |

0.08 |

0.75 |

-0.60 |

0.820 |

| Real_14_24_cerv |

1.66 |

1.28 |

1.67 |

0.91 |

0.01 |

0.73 |

-0.70 |

0.966 |

| Real_15_25_cerv |

1.37 |

1.13 |

1.50 |

1.34 |

0.13 |

0.92 |

-0.66 |

0.740 |

| Real_33_43_cusp |

0.81 |

1.41 |

0.18 |

1.33 |

-0.64 |

0.24 |

-1.52 |

0.150 |

| Real_34_44_cusp |

1.26 |

1.88 |

2.34 |

1.64 |

1.07 |

2.20 |

-0.06 |

0.062 |

| Real_35_45_cusp |

1.44 |

1.60 |

2.94 |

2.14 |

1.50 |

2.71 |

0.29 |

0.016 |

| Real_33_43_cerv |

0.28 |

0.79 |

0.62 |

0.99 |

0.34 |

0.91 |

-0.23 |

0.235 |

| Real_34_44_cerv |

0.83 |

1.09 |

1.83 |

1.17 |

1.00 |

1.72 |

0.27 |

0.008 |

| Real_35_45_cerv |

0.80 |

0.99 |

1.93 |

1.59 |

1.13 |

1.98 |

0.28 |

0.010 |

3.3. Comparison of Percentage Increase in Initial Width at Cusps and Cervical Points Between GT and CA Groups

Comparisons between groups were made based on the percentage increase of the initial width at cusps and cervical points. The analysis found no statistically significant differences between GT and CA treatments, indicating that both were equally effective in inducing relative increases in width. (

Table 3).

3.4. Comparison of Predicted and Achieved Expansion Accuracy Between GT and CA Groups

The predictability assessment of virtual setup treatment outcomes, compared to actual results, was based on the percentage of achieved expansion relative to the planned expansion. Comparisons between the GT and CA groups showed no significant differences for all outcomes, indicating similar virtual setup predictability of expansion for both treatment modalities. In general, GT accuracy tended to be higher than CA for outcomes in the upper arch, but lower for the lower arch, although the differences were not statistically significant.

Table 4.

Comparisons between groups based on the achieved percentage relative to the planned expansion (PredicAccur%). GT: Geniova; CA: clear aligner; SD: Standard deviation; Diff: difference; CI: confidence interval; sig: significance; 13_23: upper canines; 14_24: upper first premolars; 15_25: upper second premolars; 33_43: lower canines; 34_44: lower first premolars; 35_55: lower second premolars; cusp: cuspid level; cerv: cervical level.

Table 4.

Comparisons between groups based on the achieved percentage relative to the planned expansion (PredicAccur%). GT: Geniova; CA: clear aligner; SD: Standard deviation; Diff: difference; CI: confidence interval; sig: significance; 13_23: upper canines; 14_24: upper first premolars; 15_25: upper second premolars; 33_43: lower canines; 34_44: lower first premolars; 35_55: lower second premolars; cusp: cuspid level; cerv: cervical level.

| |

GT |

CA |

|

95%CI |

|

| Outcome |

Mean CA |

SD CA |

Mean GT |

SD GT |

Mean Dif |

Lower |

Upper |

p (sig) |

| PredicAccur%_13_23_cusp |

82.02 |

15.28 |

60.59 |

15.95 |

21.43 |

-23.28 |

66.14 |

0.338 |

| PredicAccur%_14_24_cusp |

84.13 |

14.57 |

58.04 |

5.72 |

26.10 |

-6.17 |

58.37 |

0.108 |

| PredicAccur%_15_25_cusp |

91.08 |

23.12 |

55.89 |

7.92 |

35.19 |

-15.32 |

85.71 |

0.163 |

| PredicAccur%_13_23_cerv |

95.99 |

32.36 |

43.43 |

5.63 |

52.55 |

-15.92 |

121.02 |

0.125 |

| PredicAccur%_14_24_cerv |

74.91 |

13.40 |

58.27 |

9.85 |

16.64 |

-17.34 |

50.63 |

0.327 |

| PredicAccur%_15_25_cerv |

77.49 |

21.06 |

49.29 |

6.91 |

28.20 |

-17.65 |

74.05 |

0.216 |

| PredicAccur%_33_43_cusp |

49.19 |

35.36 |

61.32 |

10.10 |

-12.14 |

-89.97 |

65.70 |

0.746 |

| PredicAccur%_34_44_cusp |

61.26 |

17.80 |

78.05 |

8.67 |

-16.78 |

-54.10 |

20.53 |

0.367 |

| PredicAccur%_35_45_cusp |

85.64 |

28.37 |

76.75 |

9.11 |

8.89 |

-54.37 |

72.15 |

0.735 |

| PredicAccur%_33_43_cerv |

42.41 |

26.49 |

46.87 |

12.85 |

-4.46 |

-60.50 |

51.59 |

0.872 |

| PredicAccur%_34_44_cerv |

77.41 |

11.95 |

83.64 |

9.07 |

-6.23 |

-36.25 |

23.80 |

0.676 |

| PredicAccur%_35_45_cerv |

56.58 |

24.14 |

78.33 |

23.73 |

-21.75 |

-91.90 |

48.40 |

0.533 |

4. Discussion

This work evaluated the efficacy and the predictability of the virtual setup of a novel treatment modality (GT) for dentoalveolar arch expansion, compared to conventional CA. The GT group had a lower average treatment duration and used fewer aligners compared to the CA group. Expansion was similar in both groups, except for the lower first and second premolars, which showed larger expansion in the CA group. The percentage of achieved expansion was similar for GT and CA groups at the cusps and cervical levels. Although GT group showed non-significant greater prediction accuracy of expansion compared to CA group in the upper arch, but it was lower for the lower arch. In general terms, the predictability of virtual set up measurements was similar for both the GT and CA groups.

The treatment modality in this study was not randomly assigned. However, the treatment planning for all patients was completed before the treatment modality was selected. This ensured that the initial malocclusion and treatment planning were not influenced by the specific system of aligners used, which was chosen based on the patients’ preferences after the study was explained. Additionally, the treatment modality was not selected by the orthodontist after considering the patient’s malocclusion, further supporting the independence of the treatment modality from the initial malocclusion.

It might be hypothesized that the results observed in the GT group (less treatment time and fewer aligners) could be due to the biomechanical properties of this novel system, which is based on principles of conventional multi-bracket appliances. Round nickel-titanium arches, ligated to the virtual brackets, generate continuous light forces for tooth movements. The difference in size and position between the virtual brackets generates movement in the three planes of space, as the brackets can change in size (height, width, and length) and position according to the desired design. Customization of the virtual bracket size in the GT appliance allows for greater or lesser deflection in the nickel-titanium arch during transverse movements, even in the absence of dental crowding. As an example, in cases of crossbite involving premolars without crowding, increased force can be generated due to the deflection caused by the virtual bracket size. This differentiates it from metallic brackets, which have a standard dimension and produce a ‘constant’ deflection force only when dental crowding is present. This could indicate that in cases of single-tooth crossbites, or a small group of teeth, the GT hybrid aligners may be more effective than conventional aligners and even traditional brackets, due to the greater force generated by the deflection of the nickel-titanium arch. This biomechanics allows for faster achievement of transverse dental movement than aligners alone.

Fewer aligners may lead to a shorter treatment duration and fewer adjustments, which can be more convenient for patients. Moreover, it can result in lower treatment costs, making orthodontic treatment more accessible. Aligners are typically made of plastic, and using fewer aligners can reduce the amount of plastic waste generated during treatment, and can help reduce the carbon footprint associated with orthodontic treatment. This is particularly important from an environmental perspective, as plastic waste can have significant negative impacts on ecosystems and wildlife.

Transverse expansion with aligners has been extensively reported in recent years, mainly with the Invisalign

® system [

29,

30,

31,

32] .In terms of effectiveness, most authors agree that aligners are effective in achieving expansion, but their effect is dentoalveolar, due to the buccal crown tipping of posterior teeth [

11,

15,

31,

32].Expansion is more effective in the premolar area and less effective in the canine area in most studies [

10,

15].In our study, the expansion was also dentoalveolar, with greater changes at cusps than at the cervical levels, indicating buccal crown tipping. In the maxillary arch, the greatest expansion was achieved at the first premolar and the lowest at the canine, while in the mandibular arch, the highest expansion rates was observed at the second premolar and the lowest also at the canine, in both groups.

The predictability of aligner’s expansion is usually assessed by comparing the virtual plan with the post-treatment digital models [

30]. Predicted expansion varies between different studies; some authors found significant differences between the results planned on the virtual plan [

10,

11,

12,

16,

29,

31], while others did not find significant differences [

15,

33,

34], even showing a high degree of predictability [

32]. As the virtual plan, i.e., Clincheck

®, tends to overestimate the expansion, many authors also plan an overcorrection during the expansion movement [

2,

31]. In our study, the virtual setup of GT and CA treatments showed similar predictability, although with a high degree of variability in both groups, ranging from 42.41% for lower canine cervical width to 95.99% for upper canine cervical width. The variability in the prediction of treatment outcomes was even higher in the GT group. The high degree of variability in the prediction of the results offered by the virtual setup is a common finding among the different authors [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33], with percentages of predictability ranging from 45% [

33]. to around 98-100% [

32].

The study findings offer valuable insights for orthodontic treatment planning. Clinicians should consider dental expansion efficacy, treatment duration, and predictability when selecting aligner systems. The GT system is effective for dento-alveolar expansion, offering clinical advantages like shorter first treatment phases and fewer aligners. Individualized treatment planning is crucial, considering patient-specific needs and aligner system characteristics for optimal outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Among the limitations of the present study is the difference in the mean age of the groups, which was greater in the CA group. However, both groups consisted of adult patients in whom changes due to the growth of the dental arches were not expected to have influenced the results. Another factor to take into account when interpreting the results is that the GT system does not act on molars, while CA exerts force on the molars. As a consequence, there could be biomechanical factors that influence the observed differences

5. Conclusions

The GT group had a lower average treatment duration and used fewer aligners compared to the CA group.

The percentage of achieved expansion was similar for GT and CA groups at the cusps and cervical levels, showing similar dentoalveolar expansion of canines and premolars.

The predictability of virtual set up measurements was similar for both groups too

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, J.L., JA.A. and C. M.; methodology, C.M.; software, J.L.; validation, J.L., JA.A. and C.M.; formal analysis, C.M.; investigation, J.L., JA.A. and C. M.; resources, J.L., JA.A. and C. M.; data curation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L., JA.A. and C. M; writing—review and editing, J.L., JA.A. and C. M; visualization, J.L.; supervision, C.M. and JA.A.; project administration, C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos de Madrid (internal code 20/085-E_Tesis; date of approval: April 30th 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Weir T. Clear aligners in orthodontic treatment. Aust Dent J. 2017;62 Suppl 1:58-62. [CrossRef]

- Buschang PH, Shaw SG, Ross M, Crosby D, Campbell PM. Comparative time efficiency of aligner therapy and conventional edgewise braces. Angle Orthod. 2014;84:391-396.

- Mei L, Chieng J, Wong C, Benic G, Farella M. Factors affecting dental biofilm in patients wearing fixed orthodontic appliances. Prog Orthod. 2017;18:4. [CrossRef]

- Nemec M, Bartholomaeus HM, M HB, et al. Behaviour of Human Oral Epithelial Cells Grown on Invisalign((R)) SmartTrack((R)) Material. Materials (Basel). 2020;13.

- Azaripour A, Weusmann J, Mahmoodi B, et al. Braces versus Invisalign(R): gingival parameters and patients’ satisfaction during treatment: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15:69.

- Shalish M, Cooper-Kazaz R, Ivgi I, et al. Adult patients’ adjustability to orthodontic appliances. Part I: a comparison between Labial, Lingual, and Invisalign. Eur J Orthod. 2012;34:724-730.

- Papadimitriou A, Mousoulea S, Gkantidis N, Kloukos D. Clinical effectiveness of Invisalign(R) orthodontic treatment: a systematic review. Prog Orthod. 2018;19:37.

- Muro MP, Caracciolo ACA, Patel MP, Feres MFN, Roscoe MG. Effectiveness and predictability of treatment with clear orthodontic aligners: A scoping review. Int Orthod. 2023;21:100755. [CrossRef]

- Haouili N, Kravitz ND, Vaid NR, Ferguson DJ, Makki L. Has Invisalign improved? A prospective follow-up study on the efficacy of tooth movement with Invisalign. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2020;158:420-425. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Burruezo I, Gandia-Franco JL, Cobo J, Vela-Hernandez A, Bellot-Arcis C. Arch expansion with the Invisalign system: Efficacy and predictability. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0242979. [CrossRef]

- Zhou N, Guo J. Efficiency of upper arch expansion with the Invisalign system. Angle Orthod. 2020;90:23-30. [CrossRef]

- Houle JP, Piedade L, Todescan R, Jr., Pinheiro FH. The predictability of transverse changes with Invisalign. Angle Orthod. 2017;87:19-24. [CrossRef]

- Nogal-Coloma A, Yeste-Ojeda F, Rivero-Lesmes JC, Martin C. Predictability of Maxillary Dentoalveolar Expansion Using Clear Aligners in Different Types of Crossbites. Applied Sciences. 2023;13:2963. [CrossRef]

- Galluccio G, De Stefano AA, Horodynski M, et al. Efficacy and Accuracy of Maxillary Arch Expansion with Clear Aligner Treatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20. [CrossRef]

- Lione R, Paoloni V, Bartolommei L, et al. Maxillary arch development with Invisalign system. Angle Orthod. 2021;91:433-440. [CrossRef]

- Solano-Mendoza B, Sonnemberg B, Solano-Reina E, Iglesias-Linares A. How effective is the Invisalign(R) system in expansion movement with Ex30’ aligners? Clin Oral Investig. 2017;21:1475-1484.

- Krishnan V, Daniel ST, Lazar D, Asok A. Characterization of posed smile by using visual analog scale, smile arc, buccal corridor measures, and modified smile index. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133:515-523. [CrossRef]

- Womack WR, Ahn JH, Ammari Z, Castillo A. A new approach to correction of crowding. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2002;122:310-316. [CrossRef]

- Giancotti A, Mampieri G. Unilateral canine crossbite correction in adults using the Invisalign method: a case report. Orthodontics (Chic.). 2012;13:122-127.

- Malik OH, McMullin A, Waring DT. Invisible orthodontics part 1: invisalign. Dent Update. 2013;40:203-204, 207-210, 213-205. [CrossRef]

- Ma S, Wang Y. Clinical outcomes of arch expansion with Invisalign: a systematic review. BMC Oral Health. 2023;23:587. [CrossRef]

- Rossini G, Parrini S, Castroflorio T, Deregibus A, Debernardi CL. Efficacy of clear aligners in controlling orthodontic tooth movement: a systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2015;85:881-889. [CrossRef]

- Pavoni C, Lione R, Lagana G, Cozza P. Self-ligating versus Invisalign: analysis of dento-alveolar effects. Ann Stomatol (Roma). 2011;2:23-27.

- Ke Y, Zhu Y, Zhu M. A comparison of treatment effectiveness between clear aligner and fixed appliance therapies. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19:24. [CrossRef]

- Kassam SK, Stoops FR. Are clear aligners as effective as conventional fixed appliances? Evid Based Dent. 2020;21:30-31.

- Jabs DA. Improving the reporting of clinical case series. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:900-905. [CrossRef]

- Choi DS, Jeong YM, Jang I, Jost-Brinkmann PG, Cha BK. Accuracy and reliability of palatal superimposition of three-dimensional digital models. Angle Orthod. 2010;80:497-503. [CrossRef]

- Cha BK, Lee JY, Jost-Brinkmann PG, Yoshida N. Analysis of tooth movement in extraction cases using three-dimensional reverse engineering technology. Eur J Orthod. 2007;29:325-331. [CrossRef]

- Tien R, Patel V, Chen T, et al. The predictability of expansion with Invisalign: A retrospective cohort study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2023;163:47-53. [CrossRef]

- Bouchant M, Saade A, El Helou M. Is maxillary arch expansion with Invisalign(R) efficient and predictable? A systematic review. Int Orthod. 2023;21:100750.

- D’Anto V, Valletta R, Di Mauro L, Riccitiello F, Kirlis R, Rongo R. The Predictability of Transverse Changes in Patients Treated with Clear Aligners. Materials (Basel). 2023;16. [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Bernardez ML, Vilches-Arenas A, Sonnemberg B, Solano-Reina E, Solano-Mendoza B. Efficacy and predictability of maxillary and mandibular expansion with the Invisalign(R) system. J Clin Exp Dent. 2021;13:e669-e677.

- Riede U, Wai S, Neururer S, et al. Maxillary expansion or contraction and occlusal contact adjustment: effectiveness of current aligner treatment. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25:4671-4679. [CrossRef]

- Deregibus A, Tallone L, Rossini G, Parrini S, Piancino M, Castroflorio T. Morphometric analysis of dental arch form changes in class II patients treated with clear aligners. J Orofac Orthop. 2020;81:229-238. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).