Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

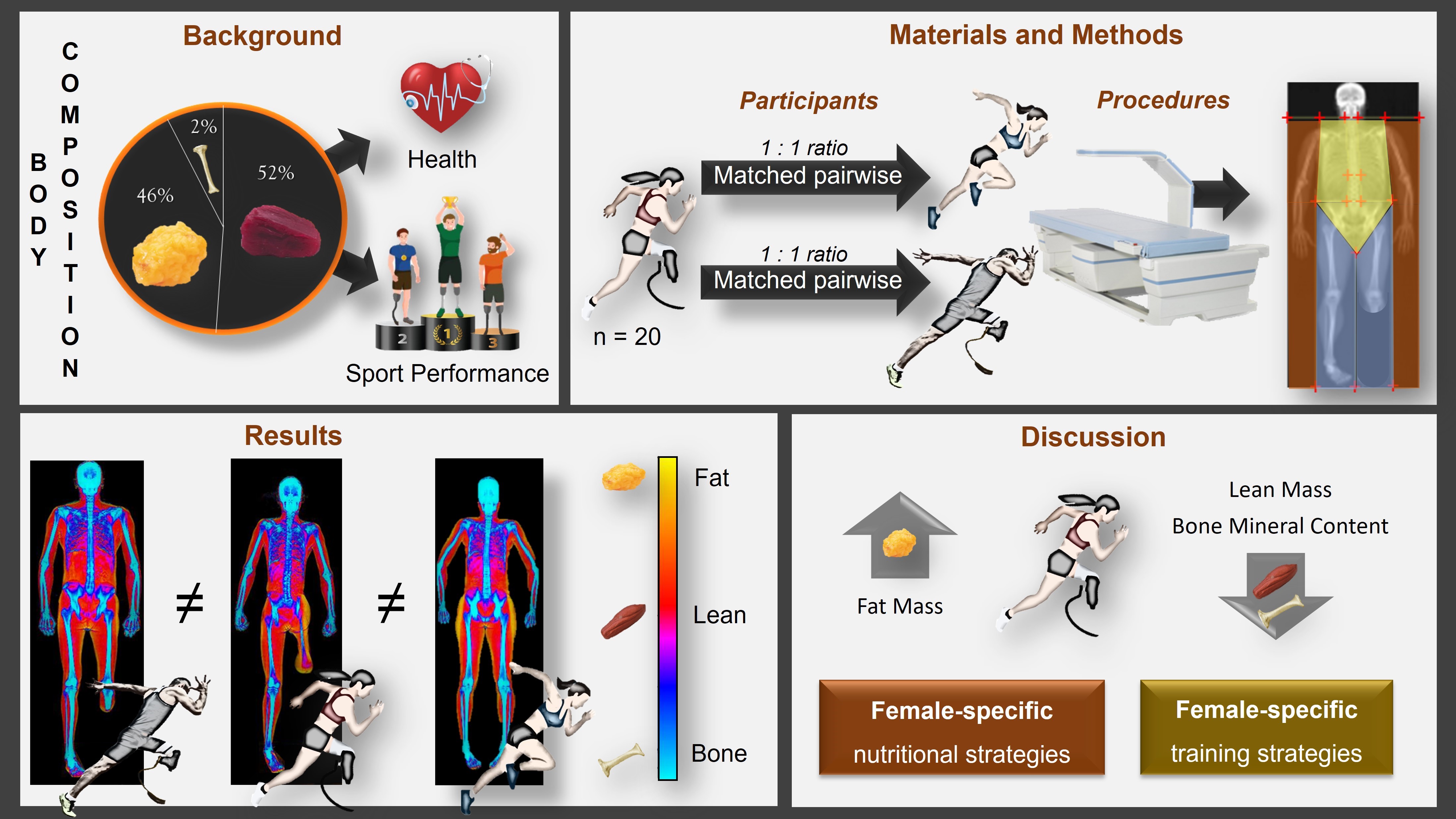

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Testing Procedures

2.2. Data Analysis and DXA Outcomes

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

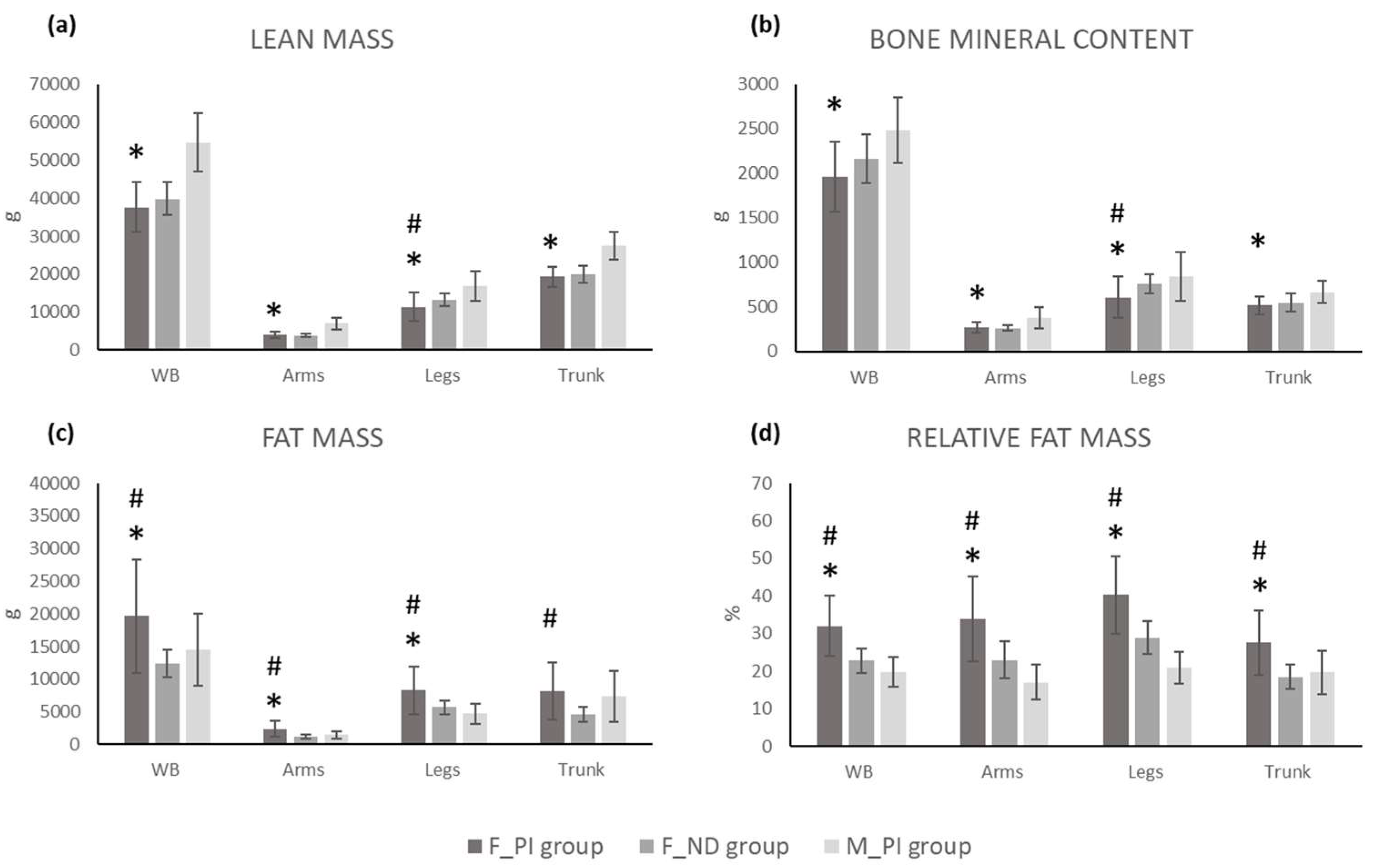

3.1. Comparison of DXA-Measured Body Composition Between Females with a Physical Impairment and Able-Bodied Females

3.2. Comparison of DXA-Measured Body Composition Between the F_PI Group and the M_PI Group

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ackland, T.R.; Lohman, T.G.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Maughan, R.J.; Meyer, N.L.; Stewart, A.D.; Müller, W. Current Status of Body Composition Assessment in Sport: Review and Position Statement on Behalf of the Ad Hoc Research Working Group on Body Composition Health and Performance, under the Auspices of the I.O.C. Medical Commission. Sports Med 2012, 42, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heymsfield, S.B.; Wang, Z.; Baumgartner, R.N.; Ross, R. Human Body Composition: Advances in Models and Methods. Annu Rev Nutr 1997, 17, 527–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavedon, V.; Milanese, C.; Marchi, A.; Zancanaro, C. Different Amount of Training Affects Body Composition and Performance in High-Intensity Functional Training Participants. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0237887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milanese, C.; Cavedon, V.; Corradini, G.; De Vita, F.; Zancanaro, C. Seasonal DXA-Measured Body Composition Changes in Professional Male Soccer Players. J Sports Sci 2015, 33, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavedon, V.; Sandri, M.; Peluso, I.; Zancanaro, C.; Milanese, C. Body Composition and Bone Mineral Density in Athletes with a Physical Impairment. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavedon, V.; Zancanaro, C.; Milanese, C. Body Composition Assessment in Athletes with Physical Impairment Who Have Been Practicing a Wheelchair Sport Regularly and for a Prolonged Period. Disabil Health J 2020, 13, 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flueck, J.L. Body Composition in Swiss Elite Wheelchair Athletes. Front Nutr 2020, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inukai, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Wang, D.-H.; Kira, S. Assessment of Total and Segmental Body Composition in Spinal Cord-Injured Athletes in Okayama Prefecture of Japan. Acta Med Okayama 2006, 60, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, L.; Wallace, J.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.; Scott, M.; Reilly, T. Body Composition of Female Wheelchair Athletes. Int J Sports Med 2009, 30, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavedon, V.; Sandri, M.; Peluso, I.; Zancanaro, C.; Milanese, C. Sporting Activity Does Not Fully Prevent Bone Demineralization at the Impaired Hip in Athletes with Amputation. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 934622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavedon, V.; Sandri, M.; Venturelli, M.; Zancanaro, C.; Milanese, C. Anthropometric Prediction of DXA-Measured Percentage of Fat Mass in Athletes With Unilateral Lower Limb Amputation. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 620040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L.; Keil, M.; Brooke-Wavell, K.; de Groot, S. A Comparison of Methods for the Estimation of Body Composition in Highly Trained Wheelchair Games Players. Int J Sports Med 2016, 37, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L.; de Zepetnek, J.O.T.; Keil, M.; Brooke-Wavell, K.; Batterham, A.M. Tracking Within-Athlete Changes in Whole-Body Fat Percentage in Wheelchair Athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2021, 16, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojtahedi, M.C.; Valentine, R.J.; Arngrímsson, S.A.; Wilund, K.R.; Evans, E.M. The Association between Regional Body Composition and Metabolic Outcomes in Athletes with Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord 2008, 46, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtahedi, M.C.; Valentine, R.J.; Evans, E.M. Body Composition Assessment in Athletes with Spinal Cord Injury: Comparison of Field Methods with Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry. Spinal Cord 2009, 47, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Paralympic Committee Paris 2024: Record Number of Delegations and Females to Compete 2024.

- Keil, M.; Totosy de Zepetnek, J.O.; Brooke-Wavell, K.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L. Measurement Precision of Body Composition Variables in Elite Wheelchair Athletes, Using Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry. Eur J Sport Sci 2016, 16, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohman, T.J.; Roache, A.F.; Martorell, R. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual: In Proceedings of the Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise; August 1992; Vol. 24; p. 952.

- Nana, A.; Slater, G.J.; Stewart, A.D.; Burke, L.M. Methodology Review: Using Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry (DXA) for the Assessment of Body Composition in Athletes and Active People. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2015, 25, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, 1988; ISBN 978-0-203-77158.

- Lim, S.; Joung, H.; Shin, C.S.; Lee, H.K.; Kim, K.S.; Shin, E.K.; Kim, H.-Y.; Lim, M.-K.; Cho, S.-I. Body Composition Changes with Age Have Gender-Specific Impacts on Bone Mineral Density. Bone 2004, 35, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavedon, V.; Zancanaro, C.; Milanese, C. Anthropometry, Body Composition, and Performance in Sport-Specific Field Test in Female Wheelchair Basketball Players. Front Physiol 2018, 9, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nindl, B.C.; Scoville, C.R.; Sheehan, K.M.; Leone, C.D.; Mello, R.P. Gender Differences in Regional Body Composition and Somatotrophic Influences of IGF-I and Leptin. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2002, 92, 1611–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.C.K. Sexual Dimorphism of Body Composition. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007, 21, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, B.N.; Volek, J.S.; Kraemer, W.J.; Saenz, C.; Maresh, C.M. Sex Differences in Energy Metabolism: A Female-Oriented Discussion. Sports Med 2024, 54, 2033–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohlgemuth, K.J.; Arieta, L.R.; Brewer, G.J.; Hoselton, A.L.; Gould, L.M.; Smith-Ryan, A.E. Sex Differences and Considerations for Female Specific Nutritional Strategies: A Narrative Review. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 2021, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchengast, S. Gender Differences in Body Composition from Childhood to Old Age: An Evolutionary Point of View. Journal of Life Sciences 2010, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, P.T. Human Ovarian Function and Reproductive Ecology: New Hypotheses. American Anthropologist 1990, 92, 933–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchengast, S.; Huber, J. Fat Distribution Patterns in Young Amenorrheic Females. Hum Nat 2001, 12, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott Sale, K.J.; Flood, T.R.; Arent, S.M.; Dolan, E.; Saunders, B.; Hansen, M.; Ihalainen, J.K.; Mikkonen, R.S.; Minahan, C.; Thornton, J.S.; et al. Effect of Menstrual Cycle and Contraceptive Pill Phase on Aspects of Exercise Physiology and Athletic Performance in Female Athletes: Protocol for the Feminae International Multisite Innovative Project. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2023, 9, e001814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott-Sale, K.J.; Ackerman, K.E.; Lebrun, C.M.; Minahan, C.; Sale, C.; Stellingwerff, T.; Swinton, P.A.; Hackney, A.C. Feminae: An International Multisite Innovative Project for Female Athletes. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2023, 9, e001675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleery, J.; Diamond, E.; Kelly, R.; Li, L.; Ackerman, K.E.; Adams, W.M.; Kraus, E. Centering the Female Athlete Voice in a Sports Science Research Agenda: A Modified Delphi Survey with Team USA Athletes. Br J Sports Med 2024, 58, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, I.S.; Crossley, K.M.; Bo, K.; Mountjoy, M.; Ackerman, K.E.; Antero, J. da S.; Sundgot Borgen, J.; Brown, W.J.; Bolling, C.S.; Clarsen, B.; et al. Female Athlete Health Domains: A Supplement to the International Olympic Committee Consensus Statement on Methods for Recording and Reporting Epidemiological Data on Injury and Illness in Sport. Br J Sports Med 2023, 57, 1164–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.G.T.F.; Alves, I.D.S.; Feliciano, N.F.; Torres, A.A.O.; de Campos, L.F.C.C.; Alves, M.L.T. Brazilian Women in Paralympic Sports: Uncovering Historical Milestones in the Summer Paralympic Games. Adapt Phys Activ Q 2024, 41, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Macías, M.; Giménez Fuentes-Guerra, F.J.; Abad Robles, M.T. Factors Influencing the Training Process of Paralympic Women Athletes. Sports (Basel) 2023, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, A.; Harris, R.; Minahan, C. “That Time of the Month” … for the Biggest Event of Your Career! Perception of Menstrual Cycle on Performance of Australian Athletes Training for the 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2022, 8, e001300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blauwet, C.A.; Brook, E.M.; Tenforde, A.S.; Broad, E.; Hu, C.H.; Abdu-Glass, E.; Matzkin, E.G. Low Energy Availability, Menstrual Dysfunction, and Low Bone Mineral Density in Individuals with a Disability: Implications for the Para Athlete Population. Sports Med 2017, 47, 1697–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, E.M.; Tenforde, A.S.; Broad, E.M.; Matzkin, E.G.; Yang, H.Y.; Collins, J.E.; Blauwet, C.A. Low Energy Availability, Menstrual Dysfunction, and Impaired Bone Health: A Survey of Elite Para Athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2019, 29, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijer, V.C.R.; Jonvik, K.L.; van Dam, L.; Risvang, L.; Raastad, T.; van Loon, L.J.C.; Dijk, J.-W. van Measured and Predicted Resting Metabolic Rate of Dutch and Norwegian Paralympic Athletes. J Acad Nutr Diet 2024, S2212-2672(24)00248-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, T.; Flueck, J.L. Energy Availability in Male and Female Elite Wheelchair Athletes over Seven Consecutive Training Days. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booranasuksakul, U.; Tsintzas, K.; Macdonald, I.; Stephan, B.C.; Siervo, M. Application of a New Definition of Sarcopenic Obesity in Middle-Aged and Older Adults and Association with Cognitive Function: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2002. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2024, 63, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Ryder, S.; Sevigny, M.; Monden, K.R.; Battaglino, R.A.; Nguyen, N.; Goldstein, R.; Morse, L.R. Association between Weekly Exercise Minutes and Resting IL-6 in Adults with Chronic Spinal Cord Injury: Findings from the Fracture Risk after Spinal Cord Injury Exercise Study. Spinal Cord 2022, 60, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| F_PI | F_ND | M_PI | ||||

| (n = 20) | (n = 20) | (n = 20) | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Demographic and anthropometric characteristic | ||||||

| Age (years) | 34.4 | 8.5 | 34.3 | 8.5 | 36.5 | 10.7 |

| Weight (kg) | 59.8 | 14.1 | 55.1 | 5.6 | 72.7 | 13.3 |

| Stature (cm) | 161.8 | 8.2 | 164.6 | 4.7 | 174.9 | 9.9 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.8 | 5.1 | 20.3 | 1.6 | 23.6 | 2.8 |

| Whole-body composition | ||||||

| FM (g) | 19645.5 | 8620.6 | 12391.0 | 2164.6 | 14531.1 | 5552.4 |

| LM | 37623.7 | 6567.5 | 39814.6 | 4345.7 | 54670.4 | 7736.5 |

| BMC (g) | 1961.4 | 398.3 | 2161.3 | 273.5 | 2488.2 | 367.9 |

| Total mass (g) | 59230.3 | 14066.3 | 54366.8 | 5586.9 | 71689.7 | 12912.8 |

| RFM (%) | 32.0 | 8.0 | 22.8 | 3.1 | 19.7 | 3.9 |

| FM/LM ratio (n) | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| ALMI (kg/m2) | 5.9 | 1.4 | 6.3 | 0.6 | 7.7 | 0.9 |

| Regional body composition | ||||||

| Arms FM (g) | 2364.8 | 1234.8 | 1243.3 | 309.7 | 1516.0 | 564.4 |

| Arms LM (g) | 4068.7 | 793.5 | 3868.0 | 480.0 | 7009.2 | 1617.6 |

| Arms BMC (g) | 268.0 | 62.4 | 263.6 | 35.0 | 377.5 | 115.3 |

| Arms total mass (g) | 6703.5 | 1697.2 | 5374.9 | 637.7 | 8906.8 | 2018.6 |

| Arms RFM (%) | 33.8 | 11.3 | 23.0 | 4.8 | 17.1 | 4.6 |

| Legs FM (g) | 8278.8 | 3659.1 | 5703.1 | 1069.2 | 4725.8 | 1565.5 |

| Legs LM (g) | 11337.7 | 3733.3 | 13263.2 | 1685.7 | 16834.5 | 3991.6 |

| Legs BMC (g) | 608.3 | 236.0 | 759.0 | 110.9 | 840.5 | 270.6 |

| Legs total mass (g) | 20224.7 | 6532.0 | 19725.3 | 2195.3 | 22400.8 | 5368.6 |

| Legs RFM (%) | 40.3 | 10.3 | 28.9 | 4.4 | 20.9 | 4.3 |

| Trunk FM (g) | 8181.8 | 4343.8 | 4659.7 | 1099.6 | 7323.1 | 3876.1 |

| Trunk LM (g) | 19309.5 | 2668.4 | 19853.7 | 2275.1 | 27413.4 | 3624.4 |

| Trunk BMC (g) | 516.4 | 103.1 | 548.1 | 105.3 | 667.6 | 128.5 |

| Trunk total mass (g) | 28007.7 | 6600.6 | 25061.5 | 2971.6 | 35404.1 | 7130.7 |

| Trunk RFM (%) | 27.6 | 8.6 | 18.5 | 3.3 | 19.7 | 5.7 |

| Android FM (g) | 1379.1 | 882.9 | 632.3 | 207.7 | 1275.0 | 709.0 |

| Android RFM (%) | 29.5 | 9.5 | 18.4 | 4.5 | 22.2 | 6.5 |

| Gynoid FM (g) | 3806.2 | 1465.4 | 2803.2 | 495.3 | 2424.0 | 743.1 |

| Gynoid RFM (%) | 38.4 | 8.4 | 30.5 | 3.8 | 22.0 | 3.8 |

| A/G ratio (n) | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| F_PI vs. F_ND | F_PI vs. M_PI | |||||

| t value | P value | Effect size | t value | P value | Effect size | |

| General characteristics | ||||||

| Age (years) | 0.037 | 0.971 | 0.01 | -1.008 | 0.320 | 0.2 |

| Weight (kg) | 1.382 | 0.175 | 0.4 | -3.341 | 0.002 | 0.9 |

| Stature (cm) | -1.327 | 0.192 | 0.4 | -5.319 | <0.001 | 1.4 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 2.103 | 0.042 | 0.7 | -0.695 | 0.491 | 0.2 |

| Whole-body analysis | ||||||

| FM (g) | 3.650 | 0.001 | 1.2 | 2.059 | 0.047 | 0.7 |

| LM | -1.244 | 0.221 | 0.4 | -8.287 | <0.001 | 2.2 |

| BMC (g) | -1.850 | 0.072 | 0.6 | -4.831 | <0.001 | 1.3 |

| Total mass (g) | 1.437 | 0.159 | 0.5 | -3.249 | 0.002 | 0.9 |

| RFM (%) | 4.820 | <0.001 | 1.5 | 5.969 | <0.001 | 1.8 |

| FM/LM ratio (n) | 4.707 | <0.001 | 1.5 | 5.659 | <0.001 | 1.7 |

| ALMI (kg/m2) | -1.312 | 0.197 | 0.4 | -5.212 | <0.001 | 1.5 |

| Regional analysis | ||||||

| Arms FM (g) | 3.940 | <0.001 | 1.2 | 2.691 | 0.011 | 0.8 |

| Arms LM (g) | 0.968 | 0.339 | 0.3 | -7.660 | <0.001 | 2.0 |

| Arms BMC (g) | 0.270 | 0.788 | 0.1 | -3.963 | <0.001 | 1.0 |

| Arms total mass (g) | 3.277 | 0.002 | 1.0 | -3.940 | <0.001 | 1.0 |

| Arms RFM (%) | 3.923 | <0.001 | 1.2 | 6.038 | <0.001 | 1.7 |

| Legs FM (g) | 3.022 | 0.004 | 1.0 | 3.809 | 0.001 | 1.1 |

| Legs LM (g) | -2.102 | 0.042 | 0.7 | -4.769 | <0.001 | 1.2 |

| Legs BMC (g) | -2.585 | 0.014 | 0.8 | -3.149 | 0.003 | 0.8 |

| Legs total mass (g) | 0.324 | 0.748 | 0.1 | -1.366 | 0.180 | 0.3 |

| Legs RFM (%) | 4.525 | <0.001 | 1.4 | 7.512 | <0.001 | 2.1 |

| Trunk FM (g) | 3.515 | 0.001 | 1.1 | 0.491 | 0.626 | 0.2 |

| Trunk LM (g) | -0.694 | 0.492 | 0.2 | -9.131 | <0.001 | 2.2 |

| Trunk BMC (g) | -0.961 | 0.343 | 0.3 | -4.495 | <0.001 | 1.1 |

| Trunk total mass (g) | 1.820 | 0.077 | 0.6 | -3.781 | 0.001 | 0.9 |

| Trunk RFM (%) | 4.443 | <0.001 | 1.4 | 3.241 | 0.003 | 0.9 |

| Android FM (g) | 3.682 | 0.001 | 1.2 | 0.405 | 0.688 | 0.1 |

| Android RFM (%) | 4.692 | <0.001 | 1.5 | 2.783 | 0.008 | 0.7 |

| Gynoid FM (g) | 2.900 | 0.006 | 0.9 | 3.684 | 0.001 | 1.0 |

| Gynoid RFM (%) | 3.845 | <0.001 | 1.2 | 7.804 | <0.001 | 2.1 |

| A/G ratio (n) | 4.126 | <0.001 | 1.3 | -3.967 | <0.001 | 1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).