Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Biosorbent Preparation

Biosorbent Characterization

Biosorption Tests with Synthetic Polluted Water

Statistical Analysis

Kinetics Study

Saturated Biosorbent Regeneration

Biosorption of Fur Industry Effluent

3. Results and Discussion

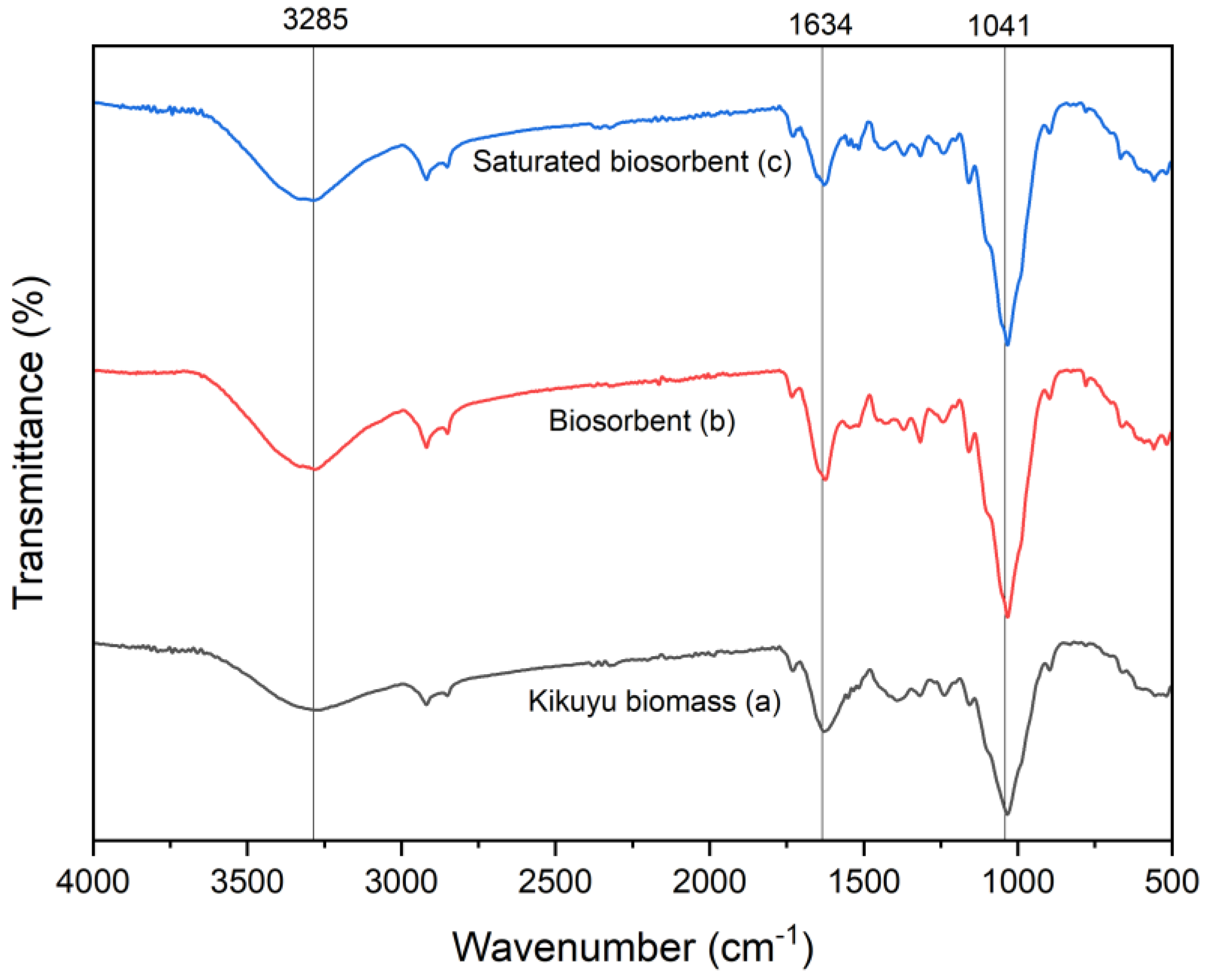

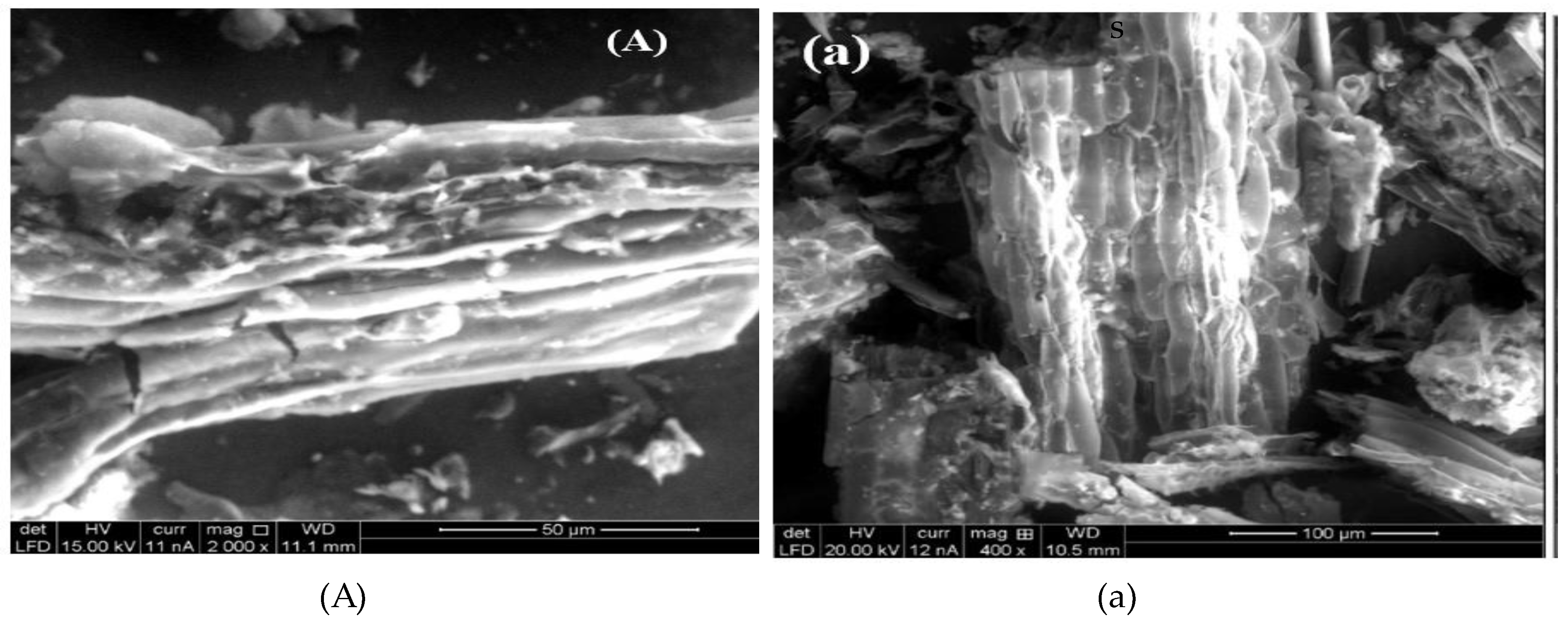

3.1. Biosorbent Characterization

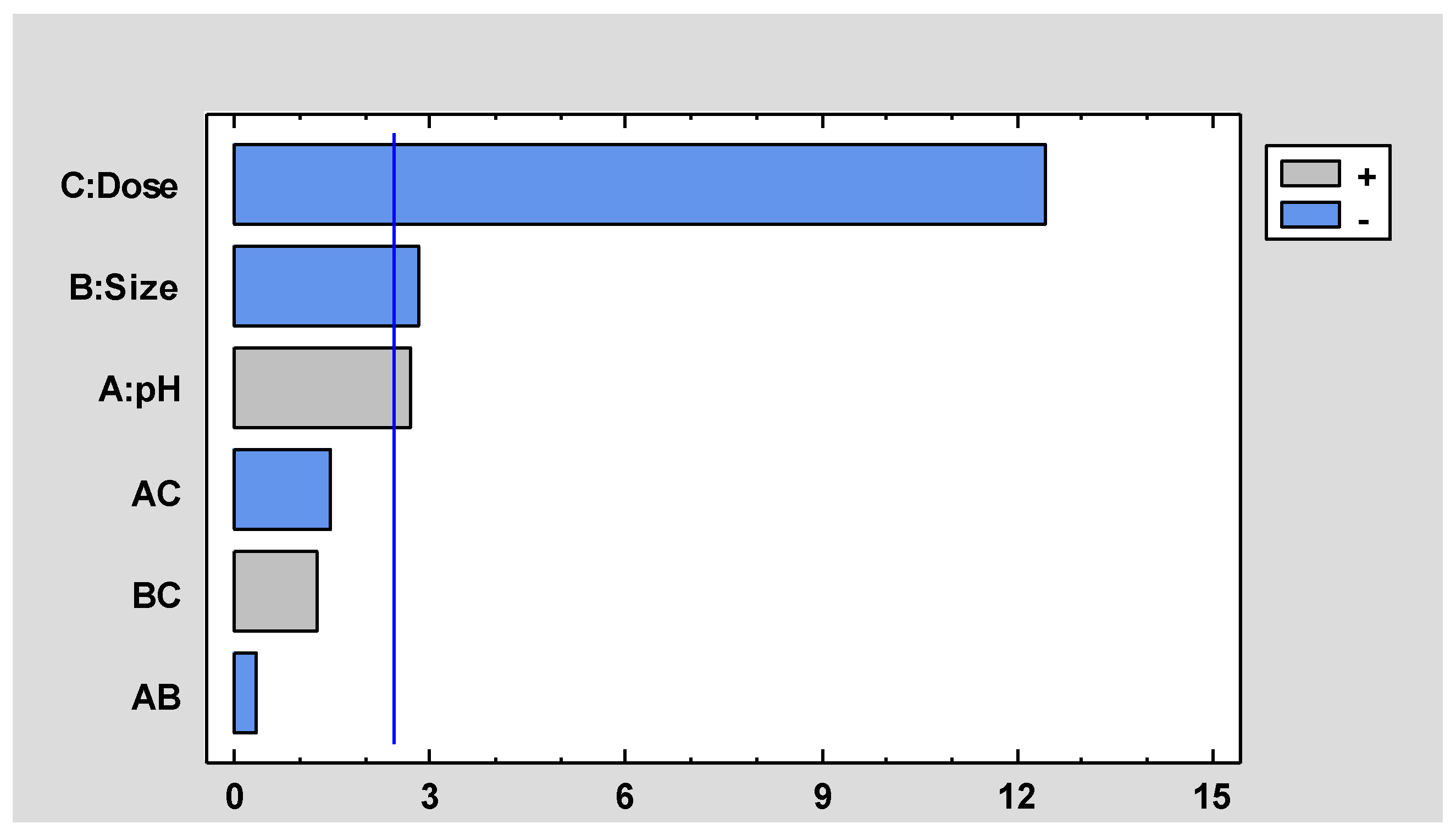

3.2. Biosorption Tests and Statistical Analysis

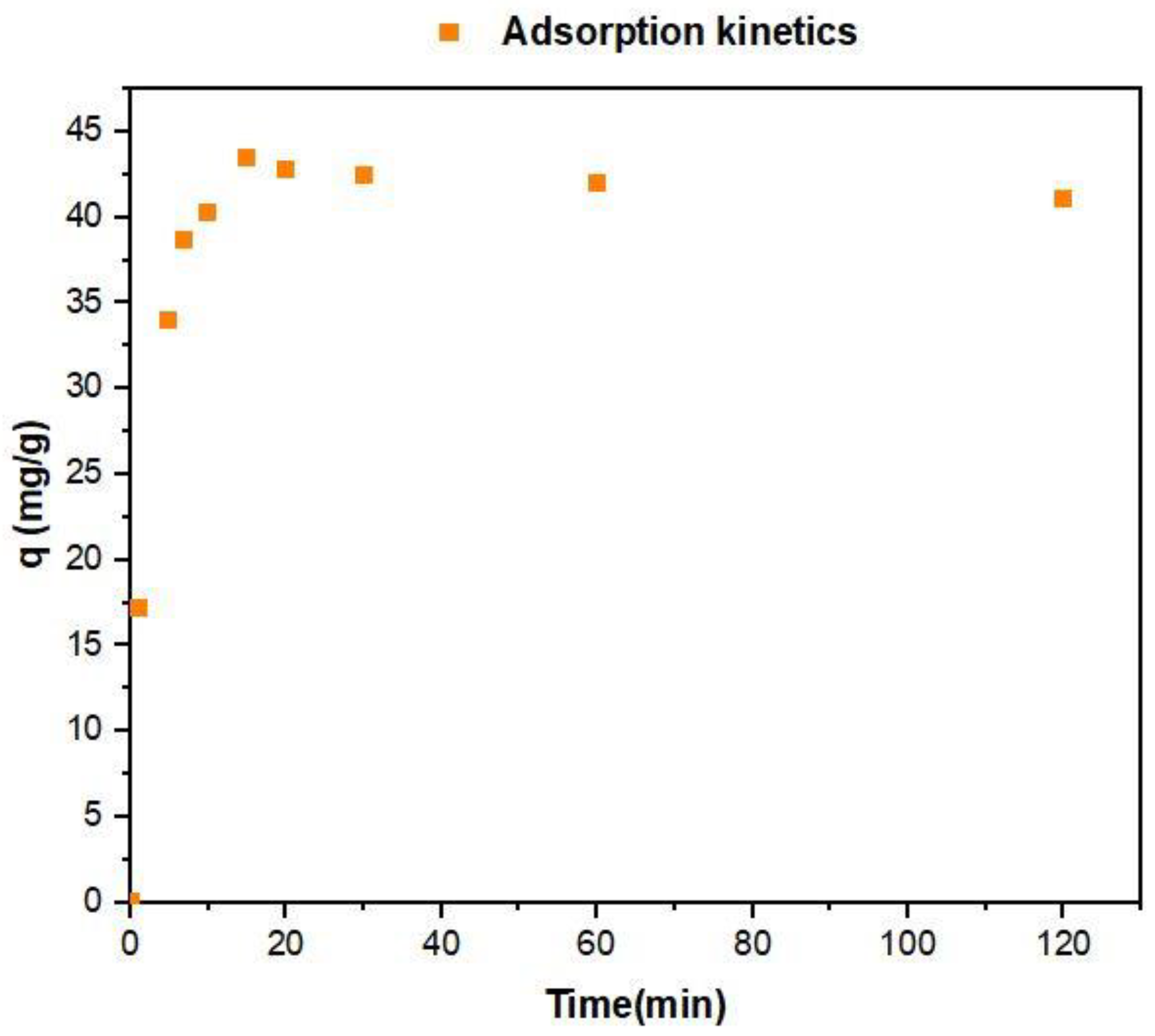

3.3. Kinetics Study

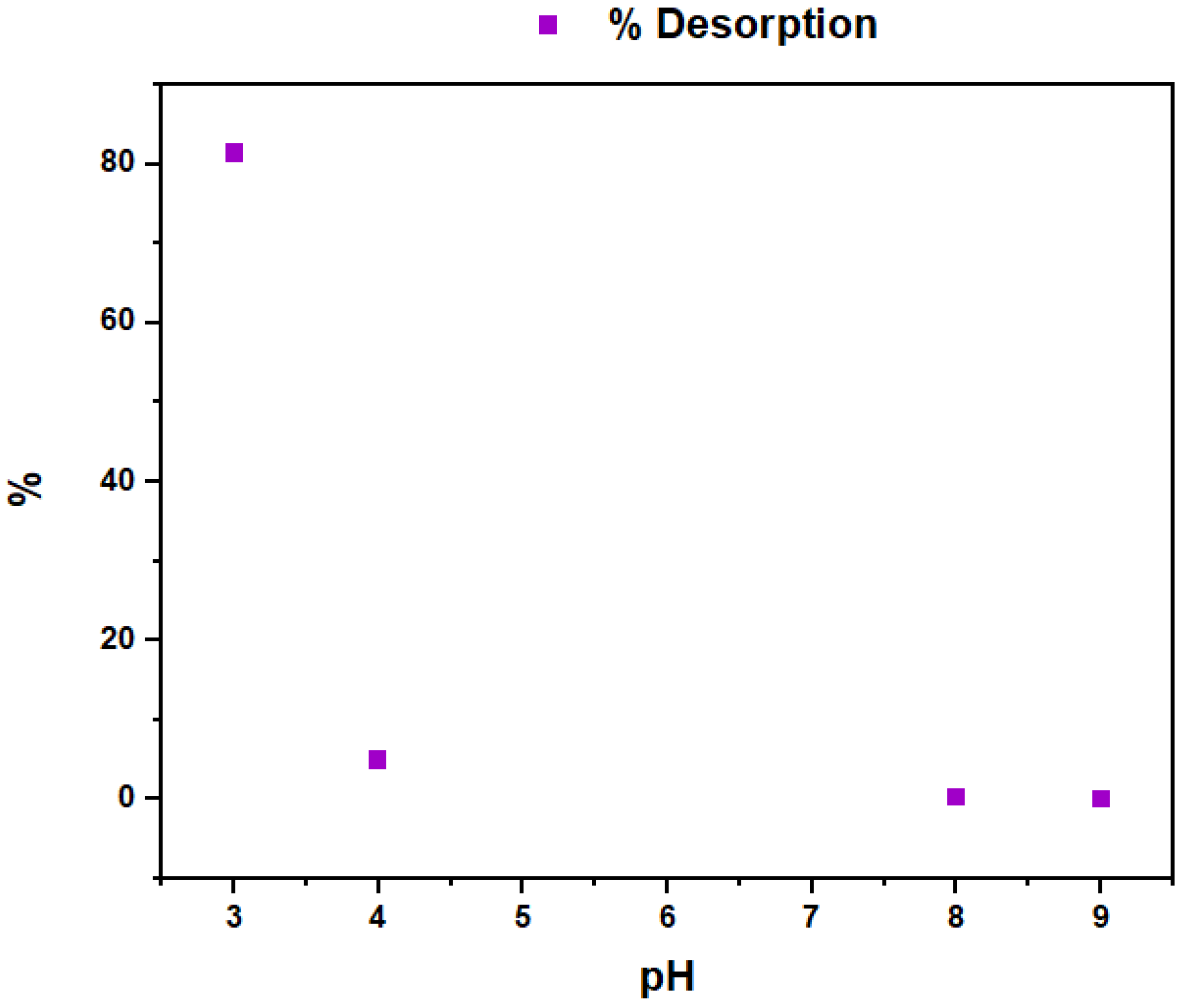

3.4. Biosorbent Regeneration

3.5. Bioadsorption Tests with Fur Industry Effluent

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- H. Cheng, T. Zhou, Q. Li, L. Lu, and C. Lin, “Anthropogenic Chromium Emissions in China from 1990 to 2009,” vol. 9, no. 2, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Alemu, B. Lemma, N. Gabbiye, M. T. Alula, and M. T. Desta, “Removal of chromium (VI) from aqueous solution using vesicular basalt: A potential low cost wastewater treatment system,” Heliyon, no. December 2017, p. e00682, 2018. [CrossRef]

- I. Ghorbel-abid, A. Jrad, K. Nahdi, and M. Trabelsi-ayadi, “Sorption of chromium (III) from aqueous solution using bentonitic clay,” DES, vol. 246, no. 1–3, pp. 595–604, 2009. [CrossRef]

- A. Maldonado-Farfán, U. Fernandez-Bernaola, H. Salas-Cernades, O. Guillen-Zevallos, and E. Medrano- Meza, “Modeling of Chromium (III) Adsorption of Aqueous Solutions Using Residual Cassava Biomass in Fixed Bed Columns,” LACCEI iInternational Multi-Conference Eng. Educ. Technol. 2021, no. Iii, 2021.

- Á. C. Porras, “Descripción de La nocividad del cromo proveniente de la industria curtiembre y de las posibles formas de removerlo,” Rev. Ing. Univ. Medellín, vol. 9, no. 17, pp. 41–49, 2010, [Online]. Available: http://www.redalyc.org/resumen.oa?id=75017164003%5Cnhttp://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=75017164003%5Cnhttp://www.redalyc.org/pdf/750/75017164003.pdf.

- N. E. Alam, A. S. Mia, F. Ahmad, and M. Rahman, “An overview of chromium removal techniques from tannery effluent,” Appl. Water Sci., 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Maldonado, C. Luque, and D. Urquizo, “Lead biosortion of contaminated waters using Pennisetum clandestinum Hochst (Kikuyu),” Rev. Latinoam. Metal. y Mater., no. SUPPL.4, 2012.

- E. Carvajal-flórez, L. Fernanda, and M. Giraldo, “Uso de residuos de café como biosorbente para la remoción de metales pesados en aguas residuales,” vol. 11, pp. 44–55, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Lavado-meza, M. R. Sun-kou, T. K. Castro-arroyo, and H. D. Bonilla-mancilla, “Química Aplicada y Analítica Biosorción de plomo (II) en de los cladodios de la tuna Biosorption of lead (II) in aqueous solution with biomass of prickly pear Resumen Resumo Introducción Materiales y métodos Preparación del biosorbente y de las disolu,” vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 36–46, 2020.

- J. De Jesús, V. Martínez, A. Milena, S. Alarcón, E. Augusto, and A. Y. El, “Kikuyu , present grass in ruminant production systems in tropic Colombian highlands El kikuyo , una gramínea presente en los sistemas de rumiantes en trópico alto colombiano Kikuyo , uma gramínea presente em sistemas de ruminantes no alto trópico colombiano,” 2018.

- I. Simona, D. Bulgariu, I. Ahmad, and L. Bulgariu, “Valorisation possibilities of exhausted biosorbents loaded with metal ions – A review,” vol. 224, no. April, pp. 288–297, 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Qin, T. Hu, Y. Zhai, N. Lu, and J. Aliyeva, The improved methods of heavy metals removal by biosorbents: A review. Elsevier, 2020.

- U. R. Fernández-Bernaola and A. R. Maldonado-Farfán, “Lead adsorption from polluted water using Opuntia larreyi cactus,” no. July 2019, pp. 24–26, 2019. [CrossRef]

- I. Enniya, L. Rghioui, and A. Jourani, “Adsorption of hexavalent chromium in aqueous solution on activated carbon prepared from apple peels,” Sustain. Chem. Pharm., vol. 7, no. September 2017, pp. 9–16, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. J. Perez Cuasquer, “TRATAMIENTO DE AGUAS RESIDUALES DE LA INDUSTRIA TEXTIL MEDIANTE PROCESOS ELECTROQUÍMICOS,” Universidad Central de Ecuador. pp. 1–93, 2015, [Online]. Available: http://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/cc2538.html.

- Y. Li, D. Wang, Q. Xu, X. Liu, and Y. Wang, “Chemosphere New insight into modi fi cation of extracellular polymeric substances extracted from waste activated sludge by homogeneous Fe (II)/ persulfate process,” Chemosphere, vol. 247, p. 125804, 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. R. Xu, Z. Y. Zhao, X. Y. Li, and J. D. Gu, “Chemical oxidative degradation of methyl tert-butyl ether in aqueous solution by Fenton’s reagent,” Chemosphere, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 73–79, 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. Valladares-Cisneros, C. Valerio, P. De la Cruz, and R. M. Melgoza, “Adsorbentes no-convencionales, alternativas sustentables para el tratamiento de aguas residuales,” Rev. Ing. Univ. Medellín, vol. 16, no. 31, pp. 55–73, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Mussatto, M. Fernandes, A. M. F. Milagres, and C. Roberto, “Effect of hemicellulose and lignin on enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose from brewer’ s spent grain,” vol. 43, pp. 124–129, 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Mussatto, G. Dragone, G. Jackson, D. M. Rocha, and I. Roberto, “Efecto de los tratamientos de hidrólisis ácida y hidrólisis alcalina en la estructura del bagazo de malta para liberación de fibras de celulosa,” no. January 2015, 2006.

- A. F. Moreno-García et al., “Sustainable biorefinery associated with wastewater treatment of Cr (III) using a native microalgae consortium,” Fuel, vol. 290, no. January, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. T. H. A. Kana, “Feasibility of metal adsorption using brown algae and fungi: Effect of biosorbents structure on adsorption isotherm and kinetics,” J. Mol. Liq., no. 2017, p. #pagerange#, 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Rearte, P. B. Bozzano, M. L. Andrade, and A. F. De Iorio, “Biosorption of Cr (III) and Pb (II) by Schoenoplectus californicus and Insights into the Binding Mechanism,” vol. 2013, 2013.

- M. Galbe and G. Zacchi, “Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Materials for Efficient Bioethanol Production,” no. July, pp. 41–65, 2007.

- S. Ho, Y. Chen, W. Qu, F. Liu, and Y. Wang, Chapter 8 - Algal culture and biofuel production using wastewater, Second Edition. Elsevier B.V., 2019.

- Y. Rajesh and L. Rao, “Materials Today: Proceedings Synthesis and Characterization of Low-Cost Wood based Biosorbent,” Mater. Today Proc., vol. 57, pp. 34–37, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Luisa, U. M. F, G. Nancy, F. Marittza, and V. Verónica, “el bagazo de caña como biosorbente,” pp. 43–49, 2016.

- A. Jacques, E. C. Lima, S. L. P. Dias, A. C. Mazzocato, and A. Pavan, “Yellow passion-fruit shell as biosorbent to remove Cr (III) and Pb (II) from aqueous solution,” vol. 57, pp. 193–198, 2007. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Jain et al., “Nonlinear regression approach for acid dye remediation using activated adsorbent: Kinetic, isotherm, thermodynamic and reusability studies,” Microchem. J., vol. 148, no. February, pp. 605–615, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Beni and A. Esmaeili, Biosorption and efficient method for removing heavy metals from industrial effluents: A Review. Elsevier B.V., 2019.

- B. Huseyin, R. Turker, L. Mustafa, and T. Adalet, “Separation and speciation of Cr (III) and Cr (VI) with Saccharomyces cerevisiae immobilized on sepiolite and determination of both species in water by FAAS,” Talanta, vol. 51, no. 5, pp. 895–902, 2000. [CrossRef]

- A. Basu et al., “Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers A study on removal of Cr (III) from aqueous solution using biomass of Cymbopogon flexuosus immobilized in sodium alginate beads and its use as hydrogenation catalyst,” J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng., vol. 102, pp. 118–132, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Elabbas, L. Mandi, F. Berrekhis, M. N. Pons, J. P. Leclerc, and N. Ouazzani, “Removal of Cr (III) from chrome tanning wastewater by adsorption using two natural carbonaceous materials: Eggshell and powdered marble,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 166, pp. 589–595, 2016. [CrossRef]

- I. A. Bhatti, N. Ahmad, N. Iqbal, M. Zahid, and M. Iqbal, “Chromium adsorption using waste tire and conditions optimization by response surface methodology,” J. Environ. Chem. Eng., vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 2740–2751, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang and X. Guo, “Adsorption kinetic models: Physical meanings, applications, and solving methods,” J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 390, no. January, p. 122156, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Chan, Y. P. Tan, A. H. Abdullah, and S. T. Ong, “Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies of a new potential biosorbent for the removal of Basic Blue 3 and Congo Red dyes: Pineapple (Ananas comosus) plant stem,” J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng., vol. 61, pp. 306–315, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Iftikhar, H. N. Bhatti, M. A. Hanif, and R. Nadeem, “Kinetic and thermodynamic aspects of Cu(II) and Cr(III) removal from aqueous solutions using rose waste biomass,” J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 161, no. 2–3, pp. 941–947, 2009. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Dias, J. G. Silva, V. L. Cardoso, and M. M. De Resende, “ScienceDirect Removal and desorption of chromium in synthetic effluent by a mixed culture in a bioreactor with a magnetic field,” J. Environ. Sci., vol. 91, no. 430, pp. 151–159, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Vakili, S. Deng, G. Cagnetta, W. Wang, and P. Meng, “Separation and Puri fi cation Technology Regeneration of chitosan-based adsorbents used in heavy metal adsorption: A review,” Sep. Purif. Technol., vol. 224, no. May, pp. 373–387, 2019. [CrossRef]

| Independent Variables | Levels | |

|---|---|---|

| Biosorbent size, T (μm) | 106 | 212 |

| Biosorbent dose, D (mg/L) | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| pH | 4.8 | 5.5 |

| Element | Unit | Zone Nº1 | Zone Nº2 | Zone Nº3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area 1 | Area 1 | Area 1 | Area 2 | Area 3 | ||

| Carbon, C | % | 54.11 | 55.88 | 67.85 | 68.27 | 63.73 |

| Oxigen, O | % | 42.17 | 41.27 | 30.83 | 30.47 | 33.47 |

| Chromium, Cr | % | 0.48 | 1.02 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.86 |

| Aluminum, Al | % | 0.41 | - | - | 0.23 | - |

| Silicon, Si | % | 2.82 | 0.49 | 0.4 | 0.39 | 1.45 |

| Calcium, Ca | % | - | 0.66 | 0.27 | - | 0.49 |

| N º | pH | Dose (g/L) | Size (μm) | Cf (mg/L) | q (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.15 | 0.75 | 150 | 28.3 2.23 | 28.9 3 |

| 2 | 5.5 | 0.5 | 212 | 29.7 1.21 | 40.6 2.4 |

| 3 | 4.8 | 0.5 | 212 | 31.91.89 | 36.1 3.8 |

| 4 | 5.5 | 1 | 106 | 24.8 3.15 | 25.2 3.2 |

| 5 | 4.8 | 1 | 106 | 26.0 0.53 | 24.0 0.5 |

| 6 | 4.8 | 1 | 212 | 28.73.62 | 21.3 3.6 |

| 7 | 5.5 | 1 | 212 | 26.5 3.86 | 23.5 3.9 |

| 8 | 4.8 | 0.5 | 106 | 29.8 2.95 | 40.4 5.9 |

| 9 | 5.15 | 0.75 | 150 | 29.4 3.03 | 27.5 4 |

| 10 | 5.5 | 0.5 | 106 | 26.12.24 | 47.9 4.5 |

| 11 | 5.15 | 0.75 | 150 | 30.7 1.49 | 25.7 2 |

| Efect | Estimated | Confidence Int. |

|---|---|---|

| Average | 31.01 | +/- 1.42921 |

| A: pH | 3.86 | +/- 3.3518 |

| B: Dose | -17.74 | +/- 3.3518 |

| C: Size | -3.99 | +/- 3.3518 |

| AB | -2.11 | +/- 3.3518 |

| AC | -0.49 | +/- 3.3518 |

| BC | 1.77 | +/- 3.3518 |

| Source | Sum of squares | LG | Square medium | F-Ratio | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: pH | 89.3204 | 1 | 89.3204 | 5.64 | 0.0258 |

| B: dose | 1888.6 | 1 | 1888.6 | 119.35 | 0 |

| C: size | 95.6004 | 1 | 95.6004 | 6.04 | 0.0216 |

| AB | 26.6704 | 1 | 26.6704 | 1.69 | 0.2065 |

| AC | 1.45042 | 1 | 1.45042 | 0.09 | 0.7647 |

| BC | 18.9038 | 1 | 18.9038 | 1.19 | 0.2853 |

| Blocks | 91.1297 | 2 | 45.5648 | 2.88 | 0.0757 |

| Total error | 379.787 | 24 | 15.8245 | ||

| Total (corr.) | 2591.46 | 32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).