1. Introduction

Vehicular Ad-hoc Network (VANET) has attracted considerable attention due to its potential to enhance driving safety in future transportation systems [

1]. VANET provides road information for vehicle assistance systems, including lane change reminders and collision warnings, through broadcast messages such as Cooperative Awareness Messages (CAM). However, the real-time nature of this communication introduces privacy and security risks. Broadcast messages often contain sensitive information, including vehicle IDs, locations, speeds, and other data in plaintext at intervals of 100 milliseconds [

2,

3]. This frequent transmission makes it relatively easy for eavesdroppers to obtain private information, such as personal preferences and home addresses [

4]. Thus, ensuring the privacy and security of VANET users is crucial, and implementing effective strategies to enhance vehicle unlinkability is essential.

Performing pseudonym changes in a mix-zone is a common strategy for protecting vehicle location privacy [

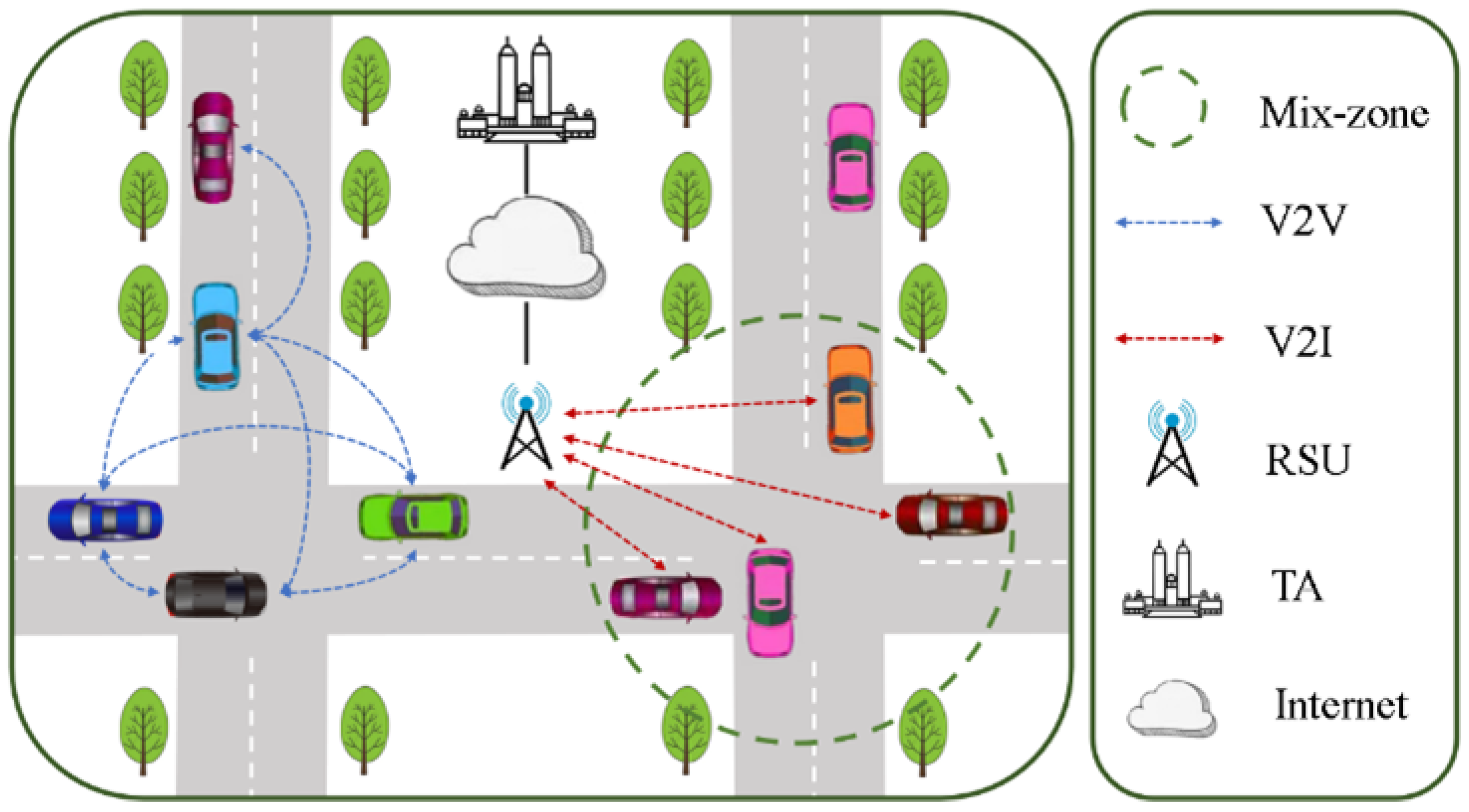

5]. As shown in

Figure 1, the TA (Trusted Authority) is typically a government-led trusted entity responsible for authenticating OBUs (On-Board Units) in the VANET and generating the pseudonyms required by the OBUs. The Road-Side Units (RSUs) define the mix-zones in the VANET, and within the mix-zones, vehicles follow the pseudonym change strategy of the RSUs, executing the strategy to protect their own location privacy and security. This strategy requires vehicles to use the pseudonyms generated by the TA as their unique identifiers and change the pseudonyms periodically under the management of the RSUs to increase the difficulty of tracking. However, relying solely on pseudonym changes is not enough to ensure user privacy, as adversaries can use independent pseudonym changes, road information, and trajectory prediction algorithms to link the pseudonym of a vehicle before and after the change, rendering the strategy ineffective.These methods are classified into two categories: syntactic linking attacks and semantic linking attacks. Syntactic linking attacks target the temporal consistency of pseudonym changes, while semantic linking attacks involve combining data from broadcast information, such as speed, acceleration, and coordinates. Additionally, the rapid advancements in the field of machine learning have significantly increased adversaries’ capabilities, thereby amplifying the threats to privacy strategies [

6].

To prevent potential syntactic linking attacks and semantic linking attacks by adversaries, strategies proposed by researchers based on pseudonym changing can be categorized into three types: encryption, silent, and chaff. Freudiger et al. [

7] proposed creating encrypted mix-zones at road intersections, where vehicles encrypt all the broadcast messages to avoid tracking. However, this approach introduces additional encryption and decryption delays. Boualouache et al. [

8] proposed using pseudonym change strategy that based on silent period in traffic-dense areas, where vehicles remain silent and do not broadcast beacon messages for a period of time. During this period, vehicles change their routes and pseudonyms to avoid tracking. Notably, this strategy weakens the environmental perception of vehicles and increases the driving safety risks in VANET [

9] as vehicles cannot receive broadcasts from other vehicles during the silent period. Additionally, mix-zones are typically deployed at crowded intersections to achieve better effect [

10], implying that this strategy may prevent vehicles from broadcasting when they need it the most. Li et al. proposed reducing the silent period to avoid collisions [

11]. However, this solution raises concerns about its ability to simultaneously ensure privacy security and driving safety. Reducing the silent time diminishes the privacy protection offered by the strategy, while the driving safety approach remains vulnerable in collision-prone areas. Vaas et al. proposed using both encryption and generated chaff messages to confuse eavesdroppers [

12], where the chaff traffic is broadcasted by assisting vehicles using pseudonyms generated by RSU and mimicking real vehicle broadcasts. However, this strategy may introduce additional delays due to encryption and decryption of all messages within the mix-zone and could potentially disrupt some legitimate vehicle communications.

To address the above issues, this paper proposes a pseudonym change strategy based on chaff traffic, which does not use encryption or silent mechanisms. Our strategy uses a neural network model to generate the chaff messages. The generated chaff messages only exists within the mix-zones and chaff filters are distributed to the verified vehicles to filter chaff messages so that the strategy do not affect the driving safety of the vehicles. The proposed strategy is proven to be able to withstand attacks from global passive adversaries. The proposed strategy outperforms previous strategies and requires lower communication overhead from vehicles compared to other chaff-based pseudonym change strategies.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

We propose the TCCM pseudonym change strategy, which uses chaff traffic to protect the location privacy of vehicles without affecting their driving safety mechanisms. The strategy does not use encryption mechanisms and can effectively defend against adversaries with machine learning capabilities from conducting syntax linking attacks and semantic linking attacks. The strategy selects better mix-zone deployment locations based on the privacy level of the vehicles, balancing the privacy level of the vehicles.

We propose a chaff traffic generation method based on the sequence-to-sequence (Seq2Seq) model, using neural networks to generate chaff traffic that closely resembles real traffic, and converge the chaff traffic with the trajectories of assisting vehicles within the mix-zone. This ensures that the chaff traffic only exists within the mix-zone and does not affect other vehicles outside the mix-zone, while reducing the communication overhead of the assisting vehicles.

Compared to existing pseudonym change strategies, although TCCM requires RSUs to use computational resources to generate chaff traffic, it can achieve a high level of privacy protection without affecting the driving safety mechanisms of vehicles.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 discusses the research on pseudonym change strategies. In

Section 3, we describe the adversary model.

Section 4 details the proposed strategy. In

Section 5, we evaluate the effectiveness of our strategy.

Section 6 discuss about current pseudonym change mix-zone strategies and future research directions. Finally,

Section 7 concludes this study.

2. Related Work

2.1. Pseudonym Change Strategies

Security is a fundamental issue in VANET. Based on the plaintext beacon messages from vehicles, attackers can launch two types of attacks: syntactic and semantic linking attacks [

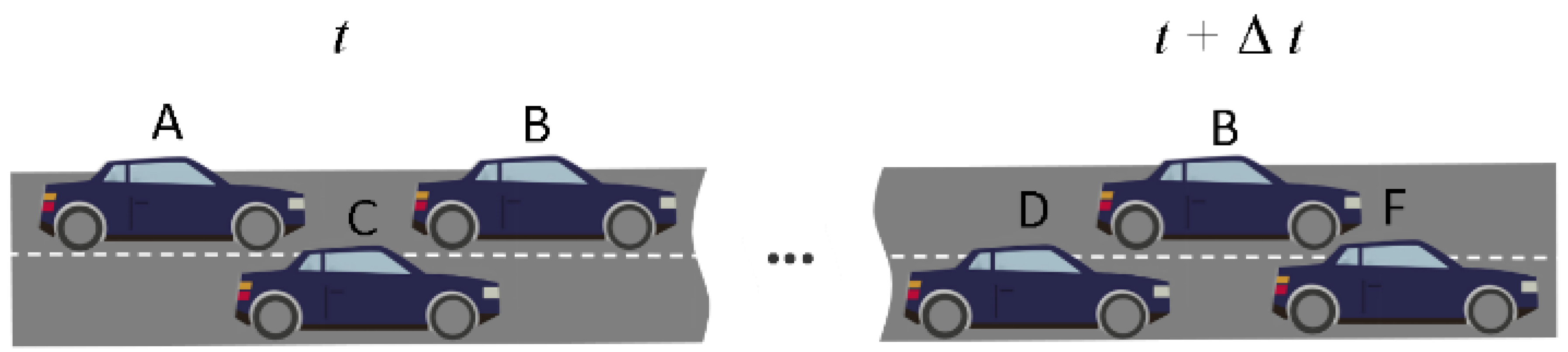

13]. Syntactic linking attacks focus on analyzing the pseudonyms used by vehicles, which can be mitigated by synchronized pseudonym changes. Semantic linking attacks utilize more complex information in the plaintext messages broadcast by vehicles, including speed, acceleration, coordinates, etc. As shown in

Figure 2, the vehicle with an original pseudonym of

B should have changed its pseudonym at time

t, but failed to do so, making it easier for the attacker to perform syntactic linking attacks on other vehicles. In addition to using filters or logical reasoning for pseudonym linking attacks, adversaries can also predict vehicle trajectories based on machine learning to link vehicles before and after pseudonym changes. Jaiswal et al. used Kalman filter to predict the trajectories of non-linear driving vehicles [

14], while Jeong et al. used deep neural networks to predict the positions of vehicles a few seconds ahead [

6]. The emergence of such syntactic linking attacks makes it difficult to ensure vehicle location privacy solely through time-synchronized pseudonym changes.

To avoid the exploitation of vehicle broadcast information by attackers, researchers have proposed pseudonym change schemes that utilize silent periods [

15]. These schemes require vehicles to temporarily pause broadcast message transmission and change pseudonyms in suitable environments. After a certain period, the vehicle travels a distance and may change its road and relative position with other vehicles. For the acknowledged adversary models in these studies, vehicles are untraceable during the silent period, so the longer the silent period, the harder it is for the attacker to link vehicles before and after pseudonym changes, such as in CSLPPS [

16], Silent cascade [

17], SLOW [

18], and BSP schemes [

11]. The paper [

10] proposes setting up a silent mix-zone in front of red traffic lights, and using data from the previous traffic light cycle to predict the length of the mix-zone for the next cycle. The silent period-based pseudonym change strategy relies on the untraceability provided by the mechanism of vehicles temporarily pausing broadcast message transmission, but broadcast messages are crucial safety information to ensure vehicle driving safety, which will lead to a decline in the situational awareness of drivers or autonomous driving systems in VANET, such as collision avoidance system [

9]. The protection capability of these schemes are often positively correlated with the duration of the silent period. Although schemes like BSP reduce the silent period to avoid collisions, this will also reduce the location privacy protection capability of the scheme, and the vehicles are still vulnerable to trajectory prediction by attackers [

19]. Therefore, it is questionable whether such schemes can balance driving safety and location privacy security.

Some researchers have proposed schemes with pseudonym changes to provide unlinkability for vehicles. These strategies require vehicles to uniformly change their pseudonyms within a mix-zone at a certain broadcast message sending interval. Some researchers have proposed establishing a simple mix-zone to enhance the location privacy of vehicles within [

20,

21]. Li et al. [

22] proposed a scheme where vehicles with lower differential exchange pseudonyms to avoid semantic linking attacks from differential attacks. In this pseudonym change strategy, vehicles will continuously transmit broadcast messages, avoiding driving safety risks due to the lack of broadcast messages. However, the continuous transmission of broadcast messages is vulnerable to trajectory-based pseudonym linking attacks, where an attacker can use the vehicle’s driving trajectory before the pseudonym change to predict the position of the vehicle in the next broadcast message after the pseudonym change [

6,

14], thereby identifying the vehicle and link the pseudonyms before and after the change. Therefore, such schemes are not sufficient to ensure location privacy. Freudiger et al. suggested encrypting the broadcast messages in the mix-zone. This scheme is called CMIX [

7]. However, using encryption in the mix-zone will introduce additional encryption and decryption delays, potentially preventing vehicles from timely processing the received broadcast messages, thereby increasing traffic risks.

Some researchers have proposed adding chaff messages in encrypted pseudonym change strategies to protect the privacy of vehicles in low-traffic density environments. These strategies not only encrypt broadcast messages within the mix-zone, but also relies on chaff messages generated by the RSU to confuse eavesdroppers and provide unlinkability [

23]. This pseudonym change strategy does not have a silent period, but it will allocate one or more corresponding chaff messages to the vehicles passing through the mix-zone and match assisting vehicles. The assisting vehicles will assist in broadcasting the chaff messages, mixing the chaff messages with the traffic on the road, making it difficult for the eavesdropper to track vehicles. Additionally, these schemes will distribute chaff message filters to verified vehicles [

24,

25], ensuring that the chaff messages only affects eavesdropper and does not impact the normal vehicles driving on the road. However, these strategies has their own issues, such as the chaff messages affecting vehicles outside the mix-zone and significantly increasing communication overhead. Moreover, these schemes also use encryption in the mix-zone that will introduce additional encryption and decryption delays.

We choose the pseudonym change strategy with chaff messages in the mix-zone, without using encryption and silent period mechanisms, based on the average privacy level of vehicles within the region to deploy the mix-zones. Within the mix-zone, vehicles will have their pseudonyms changed uniformly by the RSU, and assist each other in transmitting chaff messages to prevent attacks.

2.2. Vehicle Tracking Schemes

We assume the adversary model as a passive eavesdropper who can collect all broadcast messages on the map and has machine learning capability. After obtaining the broadcast messages, the eavesdropper will use the GPS coordinates, speed, acceleration, and heading information in the broadcast messages to perform trajectory prediction on the tracked vehicles that have implemented the pseudonym change strategy, it will attempt to link the pseudonyms of the vehicles entering and leaving the mix-zone. Kalman filter is currently a widely used trajectory prediction method.

Emara et al. [

26] used the Kalman filter to track a pseudonym change strategy based on silent periods and showed a high tracking success rate. Wiedersheim et al. proposed a Multi-Hypothesis-Tracking (MHT) method [

29] to match the most similar vehicles. Jeong et al. proposed using a deep neural network to predict vehicle trajectories in [

6], which can achieve prediction time of several seconds and provide good performance in trajectory prediction.

In this paper, we use both the Kalman filter and an LSTM-based neural network for vehicle tracking.

3. Adversary Model

We classify the Adversary models as follows:

Passive and active: A passive adversary only eavesdrops on the messages transmitted in the VANET, while an active adversary can disrupt the communication to interfere with normal applications.

Global and local: A global adversary can eavesdrop on all messages broadcast by any vehicle at any time. In contrast, a local adversary only covers a portion of the VANET for a certain period.

Internal and external: An internal adversary is a legitimate user or an authenticated member with malicious intent, while an external adversary cannot pass the identity verification.

For adversaries using active attacks, we can utilize solutions such as intrusion detection, network firewalls, and authentication. Such attacks may leave traces of the intrusion and lead to the attacker being tracked by law enforcement. Strategies that can defend against a global adversary are more robust than those against a local adversary, as the former can acquire more information. Internal adversaries require higher device overhead or higher privileges compared to external adversaries, and thus are not within the scope of this work. In VANET, vehicles broadcast their real-time location, speed, and acceleration, creating opportunities for passive eavesdropping attacks. We consider the attack model of a global passive external adversary, where the adversaries can obtain unencrypted data of all vehicles on the map, and can use trajectory prediction algorithms to perform semantic linking attacks and syntactic linking attacks, obtaining the driving trajectories of vehicles for their own benefit.

4. Trajectory Converged Chaff-Based Mix-Zone (TCCM)

4.1. Existing Problems and Challenges

In this section, we introduce existing pseudonym change strategies and highlight their shortcomings. In the current pseudonym change strategies, the following challenges remain to be solved:

Unable to simultaneously guarantee vehicle driving safety and location privacy security. The security strategy based on the silent period requires vehicles to temporarily stop sending broadcast messages during driving, which poses the risk of vehicle collisions due to missing broadcast messages. Additionally, the use of encrypted mix-zones introduces additional encryption and decryption delays, which will affect the vehicle’s driving safety strategy.

Unable to effectively defend against syntactic and semantic linking attacks, especially machine learning-based semantic linking attacks. Even with periodic pseudonym changes and use of silent period, attackers can still successfully match new and old pseudonyms with a high probability through trajectory prediction algorithms, thereby compromise the privacy security of vehicles.

Interfere with normal vehicles in the VANET. The pseudonym change strategies set up to protect vehicle location privacy may have impacts on vehicle driving safety, increased overhead, and inability to filter chaff, which may bring risks to the VANET. For example, the strategies that based on chaff messages have the problem that vehicles outside the mix-zone cannot filter out the chaff messages.

4.2. General Architecture

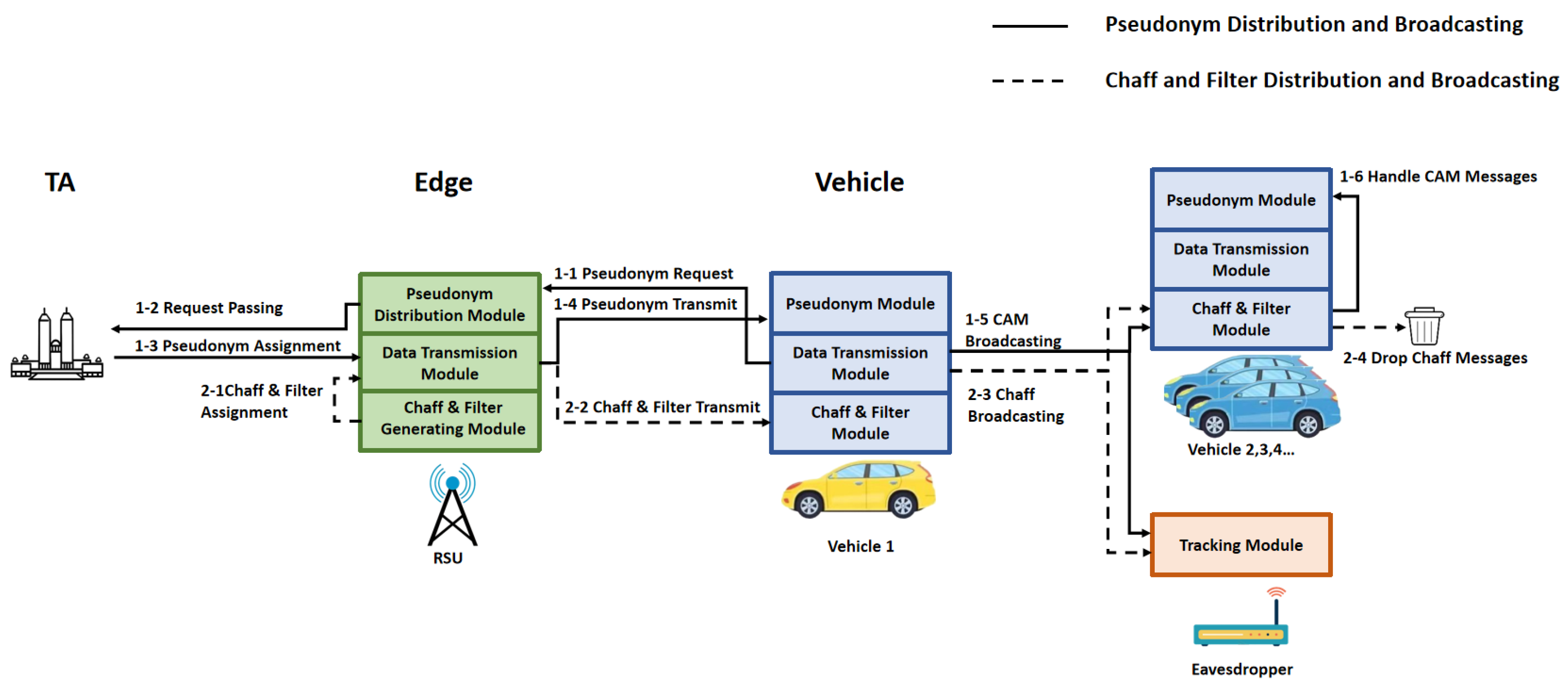

Figure 3 shows the overall architecture and the message transmission flow. Our strategy consists of three basic communication entities: OBU, RSU, and TA.

TA: The Trusted Authority (TA) is a government-led institution. We assume that each legitimate vehicle must register with the TA before joining the Vehicular Ad Hoc Network (VANET), creating a public key, a private key, and a certificate. The TA is responsible for tracking and revoking the pseudonyms of any non-compliant vehicles, as well as generating and delivering requested pseudonyms to the Roadside Unit (RSU).

RSU: RSU collects broadcast information from vehicles, performs mix-zone partitioning, delivers vehicle pseudonym generation requests, and generates and distributes chaff messages. Compared to vehicles, RSU has larger storage and computing resources.

OBU: Each vehicle is equipped with an on-board unit (OBU) and a satellite positioning device. Vehicles use the OBU to communicate with other vehicles and the RSU, and only legitimate OBU devices can pass the authentication and receive the chaff traffic filters sent by the RSU.

In our strategy, the pseudonym-related operations and chaff-related operations run simultaneously. Pseudonyms are generated by TA, while chaff traffic is generated by RSU. After vehicle 1 passes the legitimacy verification, the RSU will add vehicle 1 to the candidate list of assistant, and TA will deliver the pseudonym set of vehicle 1 to the RSU. Subsequently, the RSU will transmit the pseudonym set of vehicle 1, the chaff filter and the chaff messages that it helps to broadcast, all of which will be encrypted to prevent the filter and the pseudonym set of vehicle 1 being eavesdropped. After obtaining the above information, vehicle 1 will broadcast its own messages and the chaff messages simultaneously, while using chaff filter to exclude the chaff messages sent by other vehicles in the mix-zone, retaining only the broadcast information that needs to be processed by the driving safety application.

4.3. Mix-zone Deployment

Deploying mix-zones at all intersections can lead to excessive overhead; therefore, selecting effective mix-zones is a crucial consideration. For a given mix-zone strategy, the effectiveness of the deployment is typically assessed using metrics such as the average privacy level, the average number of vehicles passing through the mix-zones, and the average vehicle density within the mix-zones. Since the problem of optimal mix-zone placement is NP-hard, Xu et al. [

27] employed heuristic algorithms to address this challenge. In this paper, we propose a user-centric privacy protection model and utilize a genetic algorithm for the placement of mix-zones.

Assuming the target number of mix-zones is M, we first select candidate intersections, selecting from the target intersections from high to low, where N is a positive integer, determined by the actual computational capability. The purpose of this step is to select a portion of potentially better intersections as the genes for the next step of the genetic algorithm, in order to accelerate the genetic algorithm to achieve better effect.

We first analyze the traffic flow in the region, record all the traffic intersections passed by the vehicles, and then sort the intersections to obtain the set of intersections

with traffic density sorted from high to low, where

represents the

i-th intersection and

represents the traffic flow of the

i-th intersection. For any two intersections

, we have

when

. We select the

intersections with the highest traffic flow from this set to form a new set

, which can be expressed as:

will be the gene pool that the genetic algorithm can choose from in the initial stage. For each individual in the next step of the genetic algorithm, its genome is composed of M elements from , representing a layout of mix-zones.

We model the system from the user’s perspective, using the privacy level of vehicles as the evaluation criterion. The privacy level

P of vehicle

i in

is modeled based on the privacy level loss function

, where

t is the current time and

is the time elapsed since vehicle

i last left the mix-zone,

is the sensitivity parameter of the vehicle’s privacy level change over time. Whenever a vehicle passes through a mix-zone, the vehicle’s privacy loss is reset to 0. When the vehicle’s privacy loss exceeds the threshold

, the vehicle is considered to be in an unsafe state. The goal of the genetic algorithm is to select the optimal mix-zones to minimize the average time that vehicles are in an unsafe state. The privacy level loss function for vehicle

i is represented as:

where

is the time required for vehicle

i to reach an unsafe state. We define the average unsafe time for all vehicles under a given mix-zone layout

as:

where

represents the average unsafe time for all vehicles under a given mix-zone layout

,

indicates the total number of vehicles in the area.

is the unsafe time for vehicle

i under the mix-zone layout

, which can be indirectly calculated through a privacy loss function. After a vehicle becomes unsafe, the time in this state accumulates until the privacy loss is reset. Therefore, the objective function and constraints of the genetic algorithm can be described as:

It should be noted that in the mix-zone selection algorithm, we use the privacy level as the objective function of the genetic algorithm to select near-optimal mix-zone layout positions, which are independent of the specific pseudonym change strategy. By using the privacy level as the objective function, we adopt a user-centric approach, aiming to allow all vehicles to maintain relatively average time intervals when passing through mix-zones, thereby avoiding scenarios where some vehicles frequently enter mix-zones while others do not enter for an extended period.

4.4. Pseudonym Change Strategy

In the mix-zone, the pseudonym changes for vehicles are governed by broadcast information from the Roadside Unit (RSU), which collaborates with the dissemination of chaff messages to obscure the activities from potential eavesdroppers. Ideally, vehicles pair with one another, taking responsibility for the broadcasting of each other’s chaff messages. These vehicles will initiate or cease the broadcasting of chaff messages in conjunction with uniform pseudonym changes.

Each mix-zone, once deployed, generates and distributes chaff messages based on the collected vehicle trajectory data.

Figure 3 illustrates the complete travel process of vehicles within the mix-zone, including the trajectories of vehicles, the chaff messages, and the communication process between vehicles and the RSU. The pseudonyms used by vehicle A are

, and the pseudonyms used by vehicle A’s chaff messages are

, while the pseudonyms used by vehicle B’s chaff messages are

. Vehicles A and B collaborate in propagating each other’s chaff messages, specifically, vehicle A assists in broadcasting

, and vehicle B assists in broadcasting

. The figure shows six time points of communication between the RSU and vehicles, which are:

Authentication/Chaff Message Distribution. The RSU verifies the identity of vehicle A and distributes the pseudonyms , chaff messages , , and filters;

Start of Chaff Message Broadcast. The RSU synchronizes the pseudonym change for vehicles, vehicle A changes its pseudonym to and simultaneously starts sending chaff message .

Separation of Vehicle and Chaff Message. Vehicle A and chaff message C simultaneously change their pseudonyms to and respectively and proceed on their respective paths.

Start of Chaff Trajectory Converging. Vehicle A, as an assistant broadcaster for chaff message , Converging its trajectory with chaff after passing the intersection.

Trajectory Converging Complete. The trajectory converging of vehicle A and chaff message is complete, vehicle A is prepared for a uniform pseudonym change and stopping the chaff message broadcast.

Stop Chaff Message Broadcast. At the next synchronized pseudonym change, vehicle A changes its pseudonym and stops broadcasting chaff message , then leaves the mix-zone.

In our strategy, vehicles need to change their pseudonyms at the start and end of chaff message broadcasting. The RSU determines the appropriate timing for pseudonym changes based on the current vehicles designated as assistants, which are either about to start or stop broadcasting chaff messages. Even in the least favorable scenarios, vehicles must change their pseudonyms at the start and end of chaff broadcasting to mitigate the risk of detection by eavesdroppers, who may differentiate chaff messages from those of normal vehicles based on isolated pseudonym changes.

Formula 1 shows the process of the RSU assigning partners to vehicles newly entering the mix-zone.

|

Algorithm 1:Chaff Partner Selection Algorithm. |

- 1:

Input: list of vehicles L, chaff partner request by vehicle

- 2:

Output: Distributed partner

- 3:

if request is valid then

- 4:

for in L do

- 5:

if and on the same road then

- 6:

if == null then

- 7:

- 8:

else if distance(, ) < distance(, ) then

- 9:

- 10:

else

- 11:

skip - 12:

end if

- 13:

end if

- 14:

end for

- 15:

end if - 16:

return

|

4.5. Chaff Generation

We employ a sequence-to-sequence (Seq2Seq) model to generate the necessary chaff traffic. This chaff traffic comprises two stages: the trajectory prediction stage that based on the trajectory of assisted vehicle, and the converging stage that converges the chaff traffic with the assisting vehicle. The assisted and assisting vehicles are legitimate, existing entities identified by the RSU. The assisted vehicle are the source of the chaff traffic and is not responsible for disseminating its own messages. In contrast, the assisting vehicle acts as the actual broadcaster of the chaff traffic, transmitting messages in accordance with the RSU’s directives. When two vehicles are on the same road and in close proximity, they can function as assisting and assisted vehicles, collaboratively supporting each other in the broadcasting of chaff messages.

-

Trajectory Prediction Stage: In this stage, the RSU will use the large amount of data collected in the mix-zone as the dataset, based on the broadcast information of the assisted vehicle in the past period to generate the possible trajectory of the assisted vehicle in the next period as part of the chaff traffic. We use the Seq2Seq model to complete the task of generating the trajectory of the chaff traffic, the dataset for model training is based on the vehicle broadcast messages collected by each RSU in its responsible mix-zones.

The RSU will separately generate a segment of trajectory on all possible roads that the assisted vehicle may travel. These chaff messages are broadcasted by the assisting vehicle. After the assisting vehicle passes through the intersection and the road it heading is determined, the assisting vehicle will only retain the chaff trajectory in the same direction in the next stage. If the RSU can somehow obtain the driving intention of the assisting vehicle in advance, such as obtaining the navigation information of the assisting vehicle, then only one correct trajectory need to be generated.

Trajectory Converging Stage: The purpose of trajectory converging is to confuse the eavesdropper. In this stage, the RSU generates a sequence of the relative positions between the chaff traffic and the assisting vehicle, based on the relative position, the assisting vehicle perform a simple weighted calculation of its own coordinates and the relative position to obtain the actual coordinate of the chaff traffic, in which the absolute value of the relative position gradually approaches zero. After a certain time, the assisting vehicle will travel on the road with the same coordinates as the chaff traffic. Then, In the next pseudonym change time point, the assisting vehicle will stop sending chaff traffic and change its own pseudonym, and then the chaff traffic mechanism will end. Finally, the assisted vehicle and the assisting vehicle will leave the mix-zone.

After the chaff traffic converged with assisting vehicle, their coordinates, speed, and other driving characteristics in CAM messages will remain consistent. Doing so can confuse the eavesdropper regarding the identities of the assisting and assisted vehicles. Since the eavesdropper, unable to filter out the chaff traffic, may assume that the assisted vehicle is traveling along the trajectory of the chaff traffic toward the assisting vehicle, it might subsequently continue its journey while pretending to be the assisting vehicle and vice versa. Given that the two vehicles are mutually assisting and assisted, once they exit the mix-zone, the eavesdropper will be unable to distinguish the identities of the assisting and assisted vehicles, even when employing high-accuracy trajectory prediction schemes.

4.6. Chaff Filter

To ensure that the chaff messages does not produce effects similar to the sybil attack [

13],it is essential to distribute filters to all legitimate vehicles that may receive these messages. This approach prevents chaff traffic from being misidentified as real vehicles. We use the cuckoo filter [

24] as the filter for the chaff messages, which is a probabilistic data structure used to quickly determine whether an element is in the set or not. Pseudonyms are utilized as indicators to denote whether a broadcast message is a chaff message. The RSU will add the pseudonyms of chaff messages that are currently in use or may be used in the upcoming future into the filter. RSU will transmit it in encrypted form to the vehicles that have passed the identity authentication.

In [

12] and [

23], chaff messages are broadcast alongside assisting vehicles until they enter a new mix zone. Although the chaff filter is configured, it cannot be guaranteed that all vehicles can effectively filter the received chaff messages. Ensuring that all valid vehicles can obtain the appropriate filter for the chaff messages they receive remains an unresolved issue. For instance, if all chaff messages in an entire city are consolidated into a single filter and distributed to all vehicles, this may result in low filter efficiency. Attackers would only need access to one valid vehicle to easily obtain the filter and distinguish all chaff messages. Conversely, if the chaff filter is distributed only to a limited number of vehicles in the vicinity of mix zones, it becomes challenging for eavesdroppers to acquire all filters. However, determining the optimal distribution range for the chaff filter is still unsolved. Furthermore, newly introduced vehicles may not be able to filter the chaff messages as they have not yet entered a mix zone, which poses potential risks to driving safety.

In this paper, we solve these problems by limiting the existence area of the chaff traffic. The chaff messages only appear in a small range around the mix-zone, so RSU can easily determine which chaff traffic a vehicle might receive and create chaff filters according to demand. This will also be reflected in the average amount of chaff messages received by the vehicles.

5. Performance Evaluation

In this section, we introduce the simulation and analysis of the experimental results of the proposed (TCCM) scheme. We tested the TCCM strategy against the global passive adversary (GPA) introduced in

Section 3 and compared it with three representative mix-zone schemes discussed in

Section 2 that also do not utilize encryption: BSP, TAPCS, and PAPU. This comparison was based on the metric of traceability and anonymity set, allowing us to evaluate the effectiveness of each approach in mitigating the risks associated with adversarial tracking. The metrics for comparison included traceability and anonymity set size. We also analyzed the average chaff message received by vehicles by comparing our scheme with [

23].

We conducted experiments in a 155.9 km2 area using the Veins simulator on the LuST dataset. Vehicles generated beacon messages every 100 ms on the map, and RSU distributed chaff filters to all vehicles that may have received the chaff messages nearby the mix-zones. The simulation used the Simulation of Urban MObility (SUMO) tool, and the experimental parameters are listed in Table 1. The CPU we used was Ryzen 9 5900HS, while GPU was RTX 3050.

We recorded the broadcast messages of vehicles in the mix-zones selected by the algorithm in

Section 4 as the vehicle density changed over time. The eavesdropper obtained all plaintext information on the roads and attempted to track the vehicles before and after the pseudonym change using an LSTM model or Kalman filter.

The comparison of traceability and anonymity set size included BSP, TAPCS, and PAPU. The BSP scheme dynamically set the location of the mix-zone over time. In order to reduce the impact of the silent period on vehicle driving safety, the scheme reduced the silent duration. TAPCS proposed a traffic-aware pseudonym change strategy, which determined the silent zone by detecting vehicle speed to ensure that high-speed vehicles did not enter the silent zone, thereby reducing the impact of the silent period on driving safety. PAPU proposed differential privacy, where the strategy exchanged pseudonyms between vehicles with similar characteristics to confuse the eavesdropper. In our scheme, we added chaff traffic that simulated the trajectory of real vehicles in the mix-zone to confuse the eavesdropper.

We considered scenarios with different vehicle densities. We divided the 24-hour simulation data into multiple groups at 5-minute intervals. We first identified the group with the highest vehicle density in the mix-zone, assuming its vehicle density was N. Then, we found the data groups with vehicle densities around , ,..., within a certain error range of , and conducted comparative experiments with different vehicle density.

We compared our solution with the three schemes of BSP, TAPCS, and PAPU, which represented most of the non-encrypted pseudonym change mix-zone strategies.

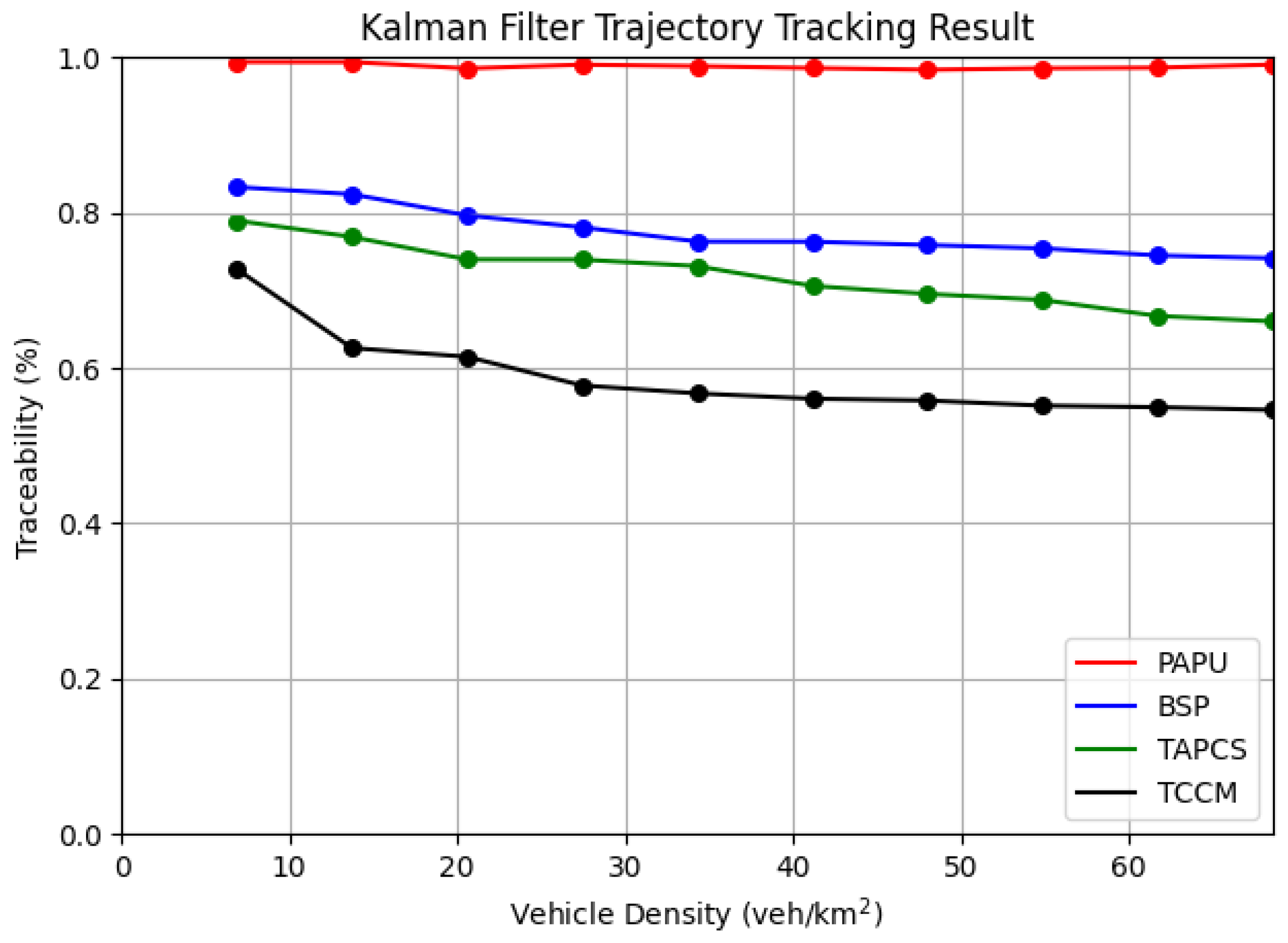

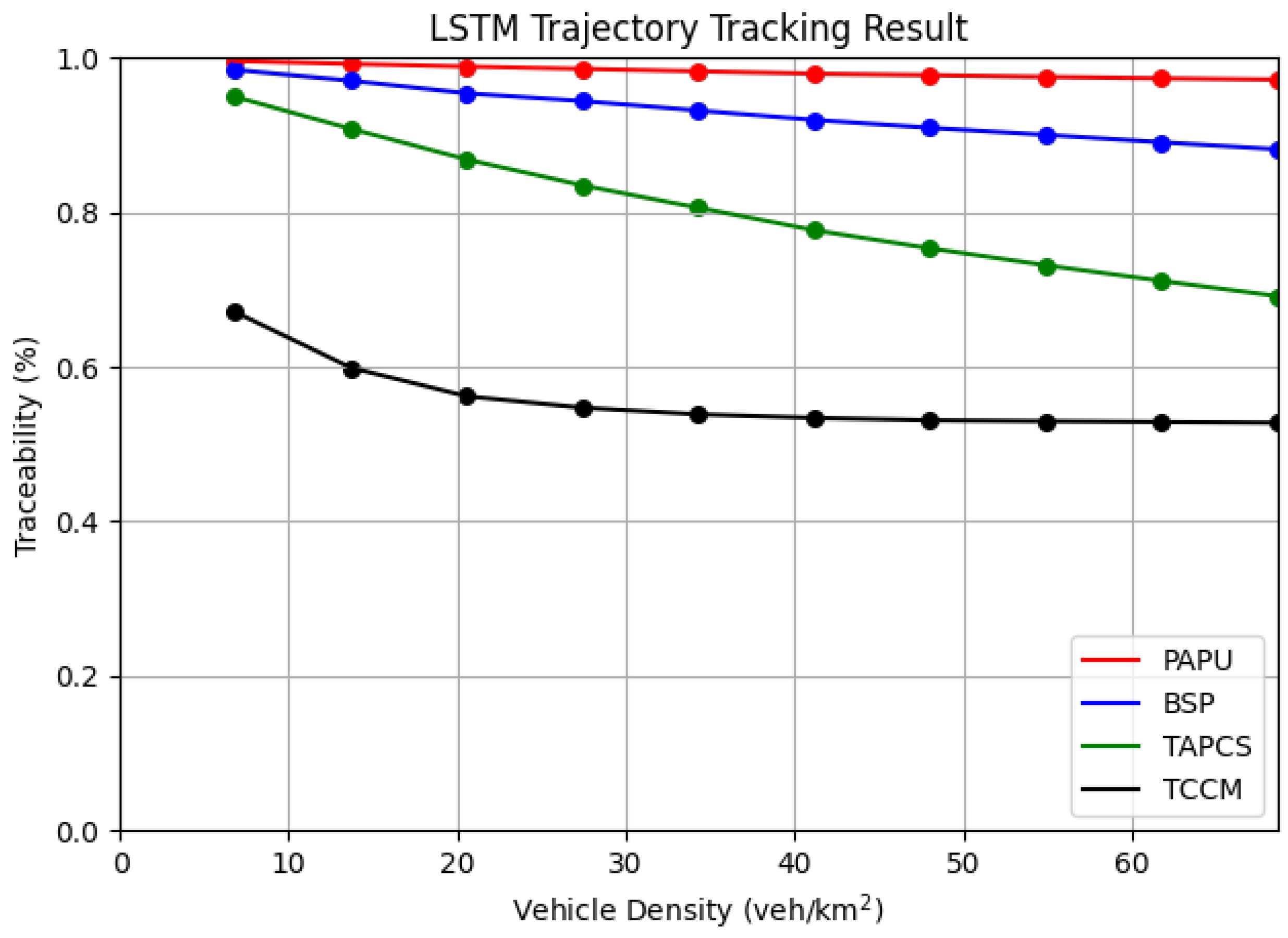

For adversaries with machine learning capabilities, we evaluated the traceability of the above schemes under different vehicle densities. Whenever the pseudonym change strategy perform a pseudonym change, pseudonym exchange, start a silent period, or increase chaff traffic, the adversary use LSTM model and Kalman filter to predict the trajectory of the target vehicle and identified the nearest vehicle from the predict position as the result of the semantic linking attack. As shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, the results show that the schemes using silent period exhibited high sensitivity to vehicle density when facing adversaries with machine learning capabilities. Our scheme, due to the addition of chaff traffic with similar trajectories to the target vehicle, had the best privacy protection performance at any vehicle density, however, in low density scenarios, some vehicle couldn’t find qualified assisting vehicles to help broadcasting chaff messages, Thus increased traceability. For adversaries using Kalman filters, the changes were not significant under different densities, but were more sensitive to the silent duration and chaff traffic mechanism. In summary, our scheme has the strongest privacy protection capability against adversaries with strong tracking capabilities using trajectory prediction.

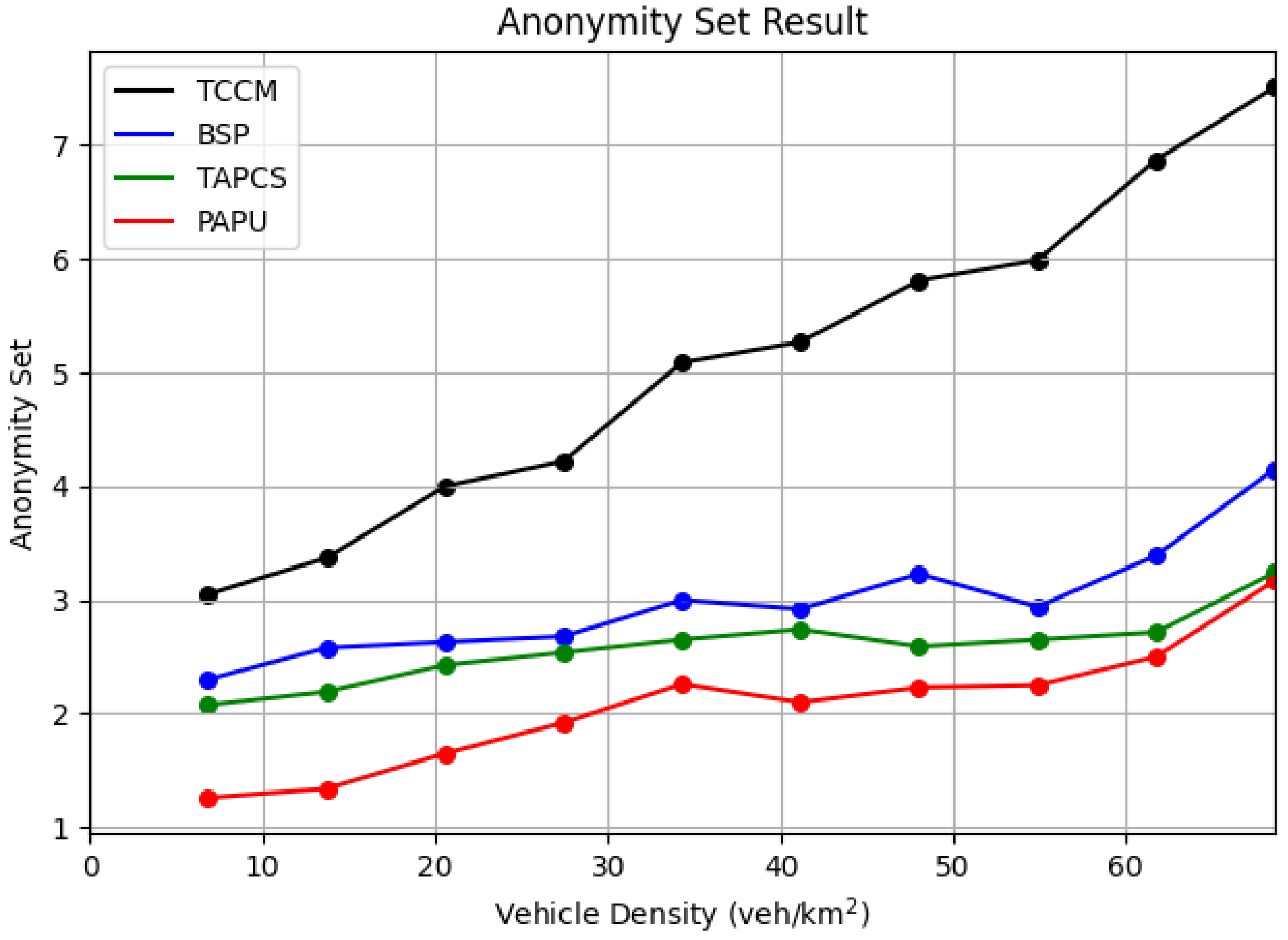

We also used the anonymity set as a comparison metric, where

represented the size of the anonymity set in the mix-zone. Each vehicle in the anonymity set has an equal probability of being the target vehicle for the adversary. As shown in

Figure 7, after adding chaff traffic, our scheme has a larger anonymity set compare to the other schemes, and therefore has higher obfuscation.

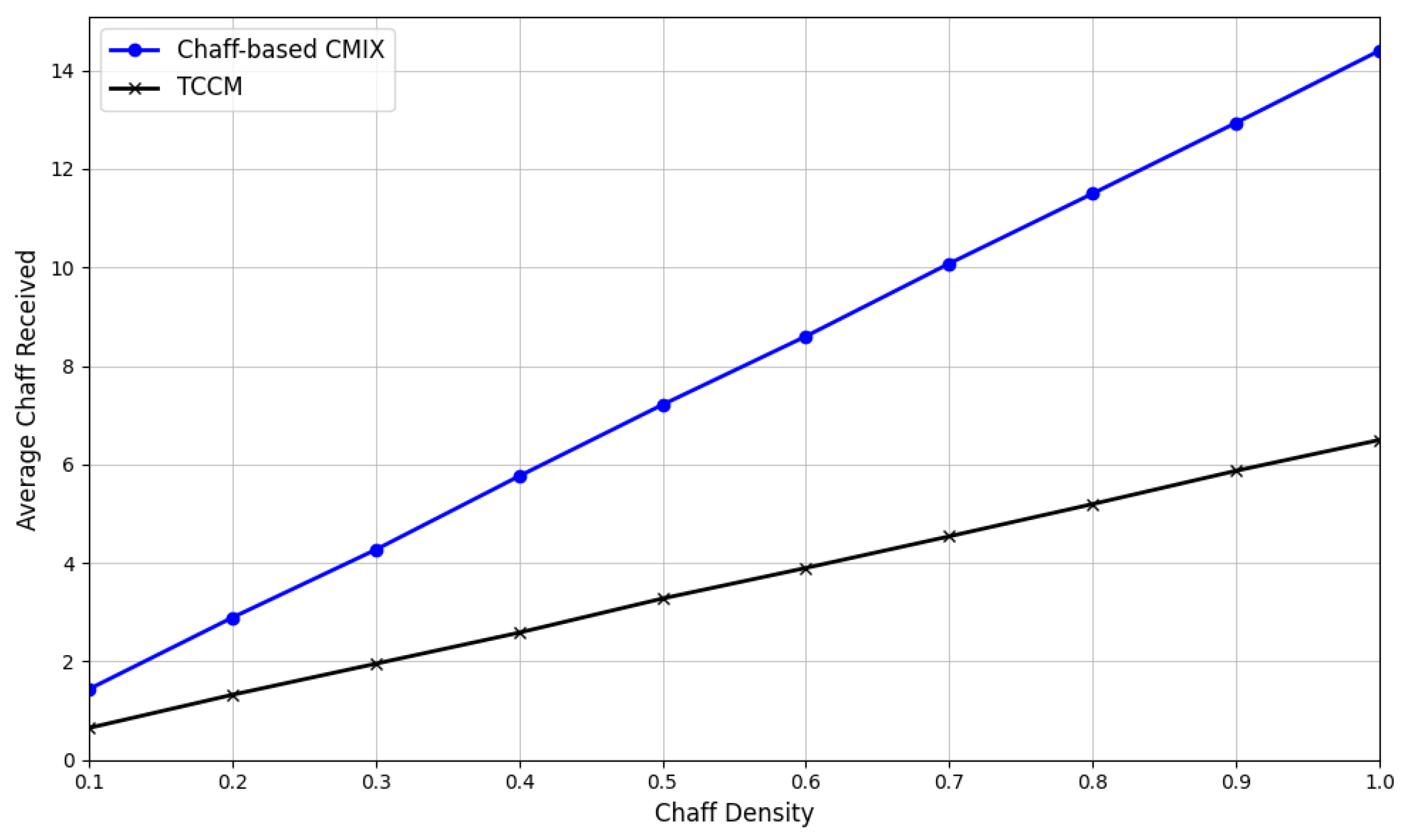

In

Figure 8, we compared our scheme with [

23]. The chaff density refers to the proportion of vehicles on the road that have been assigned chaff traffic by the RSU and are therefore required to assist in broadcasting.For instance, if half of the vehicles are requested to assist in broadcasting chaff messages, the chaff density would be 0.5. We compared the average amount of chaff messages received by vehicles under different chaff densities. The results indicate that our scheme effectively reduces the amount of chaff traffic on the road, thereby minimizing the additional overhead associated with chaff traffic.

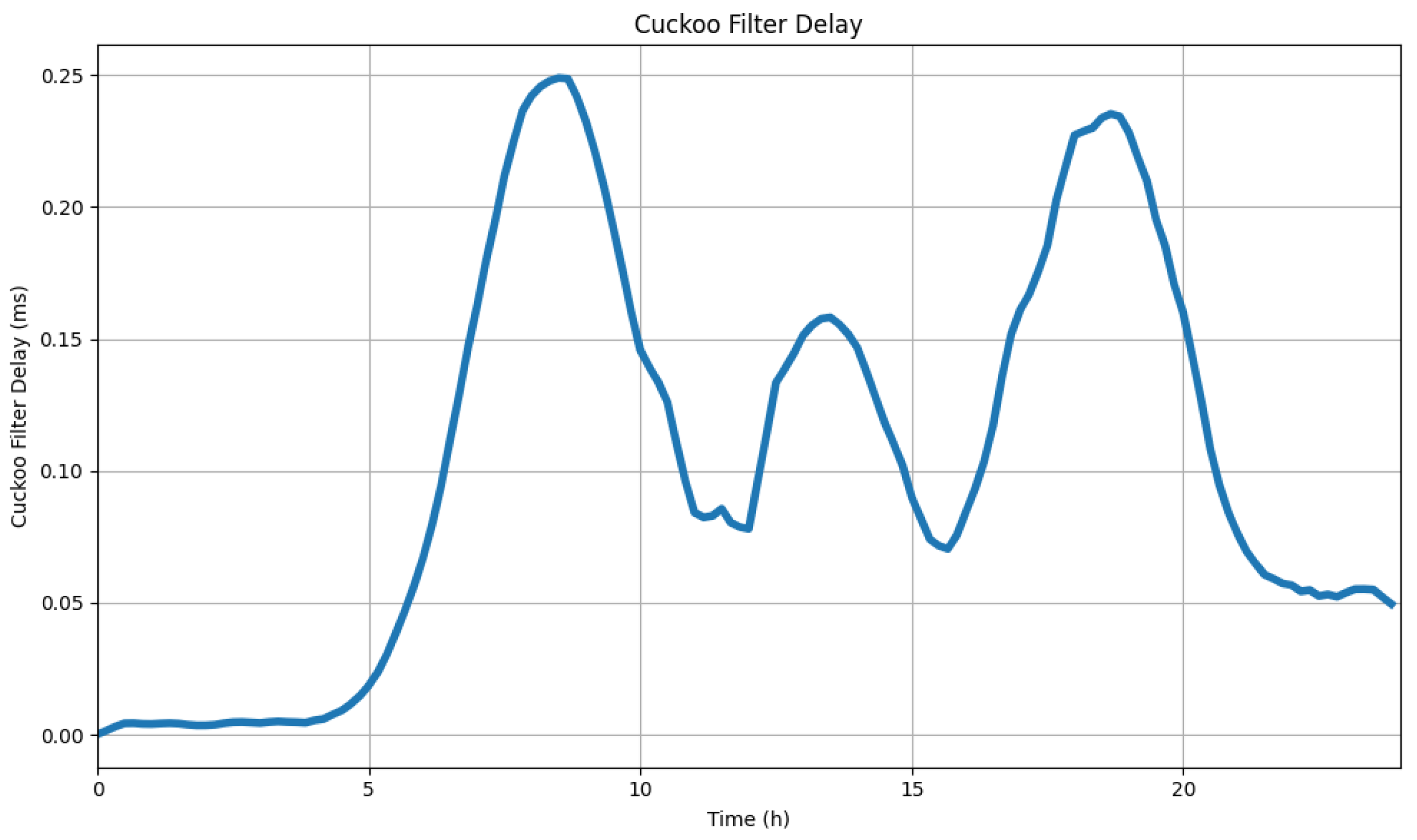

In the mix-zone, vehicles are required to use chaff filter to filter out chaff messages, typically based on efficient data structures such as Cuckoo Filters. In

Figure 9, we evaluate the average delay of using a Cuckoo Filter as chaff filter within the experimental environment. This study conducts experiments using the LuST dataset over a 0-24 hour range, calculating the average time spent by vehicles filtering the received chaff traffic every 100 ms under the proposed chaff traffic strategy. It is observed that within each broadcast interval, the additional time delay is below 0.25 ms, while the average time for a vehicle to filter a single chaff message is 0.001958 ms.

6. Discussion

In this section, we discuss about current pseudonym change mix-zone strategies and future research directions. Our adversary model is a global passive adversary that uses a low-cost transceiver to eavesdrop on all vehicles on the map, and enhances its capabilities through trajectory tracking methods, including deep learning models.

Vehicles on the road are advised to broadcast information such as coordinates, speed, heading angle, and pseudonym at intervals of 100 ms. When a vehicle does not change its pseudonym, an eavesdropper can easily correlate message from the same vehicle using a consistent pseudonym. However, when the vehicle changes its pseudonym, the eavesdropper can predict the vehicle’s trajectory using data such as coordinates, speed, and heading. Even with a simple physical model constructed from the above data, the eavesdropper can accurately predict the position of the vehicle in 100 ms, or even in 1-2 seconds. The eavesdropper can then infer that the vehicle closest to the predicted coordinates is the original vehicle, thereby undermining the pseudonym change mechanism. The Kalman filter effectively achieves good tracking performance based on this principle.

For strategies that utilize silent periods, increasing the interval between vehicle broadcasts does indeed make it more difficult for eavesdroppers to predict accurate results. However, one of the primary purposes of vehicles broadcasting messages is to enhance their situational awareness to avoid risks such as collisions. Additionally, mix-zones are often implemented in areas of high traffic density, which are typically the locations where the probability of traffic accidents is higher [

9]. Therefore, the rationale for reducing broadcast messages by over 90% in areas where they are most crucial warrants further discussion. Our experimental results in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 indicate that the privacy protection capability of silent-based mix-zones is positively correlated with the duration of silence before and after pseudonym changes. If researchers choose to reduce the silent period or maintain silence only when vehicles are moving slowly at intersections while waiting for a red light, this may decrease the effectiveness of the privacy protection afforded by silence, because the physical movement of vehicles becomes easier to predict.

For strategies that utilize the CMIX scheme, it can be assumed that vehicles within the mix-zone cannot be eavesdropped on, as all originally plaintext broadcast messages are encrypted, and only verified vehicles can decrypt them. However, this introduces similar issues to the silent-based mix-zone. Existing strategies often opt to broadcast vehicles’ CAM messages in plaintext for the majority of the time. One important reason for this is that the additional delay introduced by encryption and decryption could be fatal for high-speed vehicles that are sensitive to delays. Failure to process broadcast messages in a timely manner can reduce the availability of these messages, which is not suitable for mix-zones, where the risk of vehicle collisions is high, and also where these strategies must be implemented.

Our approach utilizes chaff messages to enhance the mix-zone, similar to how silent-based mix-zone strategies rely on silence and CMIX strategies rely on encryption. Our method obfuscates the identities of assisting and assisted vehicle groups, thereby interfering with the traffic and disrupting potential linking attacks by eavesdroppers with trajectory prediction capabilities. This effectively protects vehicle privacy with minimal impact.

While TCCM shows promising results, there are several areas for future research. One direction is to optimize the generation and distribution of chaff to minimize computational and communication overheads. Additionally, exploring the use of advanced machine learning techniques to dynamically adjust chaff parameters based on real-time traffic conditions could further enhance the strategy’s effectiveness.

7. Conclusions

We propose a new pseudonym change strategy called TCCM to address the challenge of location privacy breach in VANET. The strategy follows a user-centric design, where a genetic algorithm is used to select the mix-zones that minimizes the vehicle’s unsafe time, chaff messages that only exists within the mix-zone is added to confuse the eavesdropper along with periodic pseudonym changes. The analysis results show that the TCCM pseudonym change strategy provides relatively strong privacy protection against adversaries using Kalman filters and neural networks, and has better vehicle anonymity set. Furthermore, TCCM mix-zone does not use silent periods or encryption techniques, which allows it to minimize the impact on vehicle location service. In future work, we plan to explore more advanced models to generate more realistic chaff traffic.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Qiu, J.; Chen, Y.; Tian, Z.; Guizani, N.; Du, X. The security of internet of vehicles network: Adversarial examples for trajectory mode detection. IEEE Network 2021, 35, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräfling, S.; Mähönen, P.; Riihijärvi, J. Performance evaluation of IEEE 1609 WAVE and IEEE 802.11 p for vehicular communications. In 2010 Second International Conference on Ubiquitous and Future Networks (ICUFN); IEEE: 2010; pp. 344–348.

- Festag, A. Cooperative intelligent transport systems standards in Europe. IEEE Communications Magazine 2014, 52, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyan, M.K.; Devi, G.U. A survey on internet of vehicles: applications, technologies, challenges and opportunities. International Journal of Advanced Intelligence Paradigms 2019, 12, 98–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, I.; Mirza, H.T.; Arain, Q.A.; Memon, H. Multiple mix zones de-correlation trajectory privacy model for road network. Telecommunication Systems 2019, 70, 557–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.; Baek, M.; Lee, S.-S. Long-term prediction of vehicle trajectory based on a deep neural network. In 2017 International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC); IEEE: 2017; pp. 725–727.

- Freudiger, J.; Raya, M. Mix-zones for location privacy in vehicular networks. In Proc. of ACM Workshop on Wireless Networking for Intelligent Transportation Systems 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Boualouache, A.; Senouci, S.-M.; Moussaoui, S. Vlpz: The vehicular location privacy zone. Procedia Computer Science 2016, 83, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefevre, S.; Petit, J.; Bajcsy, R.; Laugier, C.; Kargl, F. Impact of v2x privacy strategies on intersection collision avoidance systems. In 2013 IEEE Vehicular Networking Conference; IEEE: 2013; pp. 71–78.

- Li, Y.; Yin, Y.; Chen, X.; Wan, J.; Jia, G.; Sha, K. A secure dynamic mix zone pseudonym changing scheme based on traffic context prediction. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2021, 23, 9492–9505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lai, Y.X.; Chen, Y. Broadcast and Silence Period (BSP): A Pseudonym Change Strategy. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2023, 72, 13618–13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaas, C.; Khodaei, M.; Papadimitratos, P.; Martinovic, I. Nowhere to hide? Mix-zones for private pseudonym change using chaff vehicles. In 2018 IEEE Vehicular Networking Conference (VNC); IEEE: 2018; pp. 1–8.

- Abuarqoub, A.; Alzu’bi, A.; Hammoudeh, M.; Ahmad, A.; Al-Shargabi, B. A Survey on Vehicular Ad hoc Networks Security Attacks and Countermeasures. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Future Networks & Distributed Systems; 2022; pp. 701–707.

- Jaiswal, R.K.; Jaidhar, C.D. Location prediction algorithm for a nonlinear vehicular movement in VANET using extended Kalman filter. Wireless Networks 2017, 23, 2021–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Matsuura, K.; Yamane, H.; Sezaki, K. Enhancing wireless location privacy using silent period. In IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference; IEEE: 2005; pp. 1187–1192.

- Benarous, L.; Bitam, S.; Mellouk, A. CSLPPS: Concerted silence-based location privacy preserving scheme for internet of vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2021, 70, 7153–7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yamane, H.; Matsuura, K.; Sezaki, K. Silent cascade: Enhancing location privacy without communication QoS degradation. In Security in Pervasive Computing: Third International Conference, SPC 2006, York, UK, April 18-21, 2006. Proceedings; Springer: 2006; pp. 165–180.

- Khodaei, M.; Papadimitratos, P. Evaluating on-demand pseudonym acquisition policies in vehicular communication systems. In Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Internet of Vehicles and Vehicles of Internet; 2016; pp. 7–12.

- Emara, K.; Woerndl, W.; Schlichter, J. CAPS: Context-aware privacy scheme for VANET safety applications. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Security & Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks; 2015; pp. 1–12.

- Zhang, Z.; Feng, T.; Wong, W.-C.; Sikdar, B. A Geo-Indistinguishable Context-Based Mix Strategy for Trajectory Protection in VANETs. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, H.; Pan, M.; Yue, H.; Li, X.; Fang, Y. Traffic-aware multiple mix zone placement for protecting location privacy. In 2012 Proceedings IEEE INFOCOM; IEEE: 2012; pp. 972–980.

- Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Ren, Y.; Ma, S.; Luo, B.; Weng, J.; Ma, J.; Huang, X. PAPU: Pseudonym swap with provable unlinkability based on differential privacy in VANETs. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, 7, 11789–11802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaei, M.; Papadimitratos, P. Cooperative location privacy in vehicular networks: Why simple mix zones are not enough. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, 8, 7985–8004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Andersen, D.G.; Kaminsky, M.; Mitzenmacher, M.D. Cuckoo filter: Practically better than bloom. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM International Conference on Emerging Networking Experiments and Technologies; 2014; pp. 75–88.

- Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Phillips, C. Enhanced Pseudonym Changing in VANETs: How Privacy is Impacted Using Factitious Beacons. In 2023 Wireless Telecommunications Symposium (WTS); IEEE: 2023; pp. 1–6.

- Emara, K. Safety-aware location privacy in VANET: Evaluation and comparison. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2017, 66, 10718–10731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yu, X. Multiple mix-zones deployment for continuous location privacy protection. In 2016 IEEE Trustcom/BigDataSE/ISPA; IEEE: 2016; pp. 760–766.

- Emara, K.; Woerndl, W.; Schlichter, J. On evaluation of location privacy preserving schemes for VANET safety applications. Computer Communications 2015, 63, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedersheim, B.; Ma, Z.; Kargl, F.; Papadimitratos, P. Privacy in inter-vehicular networks: Why simple pseudonym change is not enough. In 2010 Seventh International Conference on Wireless On-Demand Network Systems and Services (WONS); IEEE: 2010; pp. 176–183.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).