Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

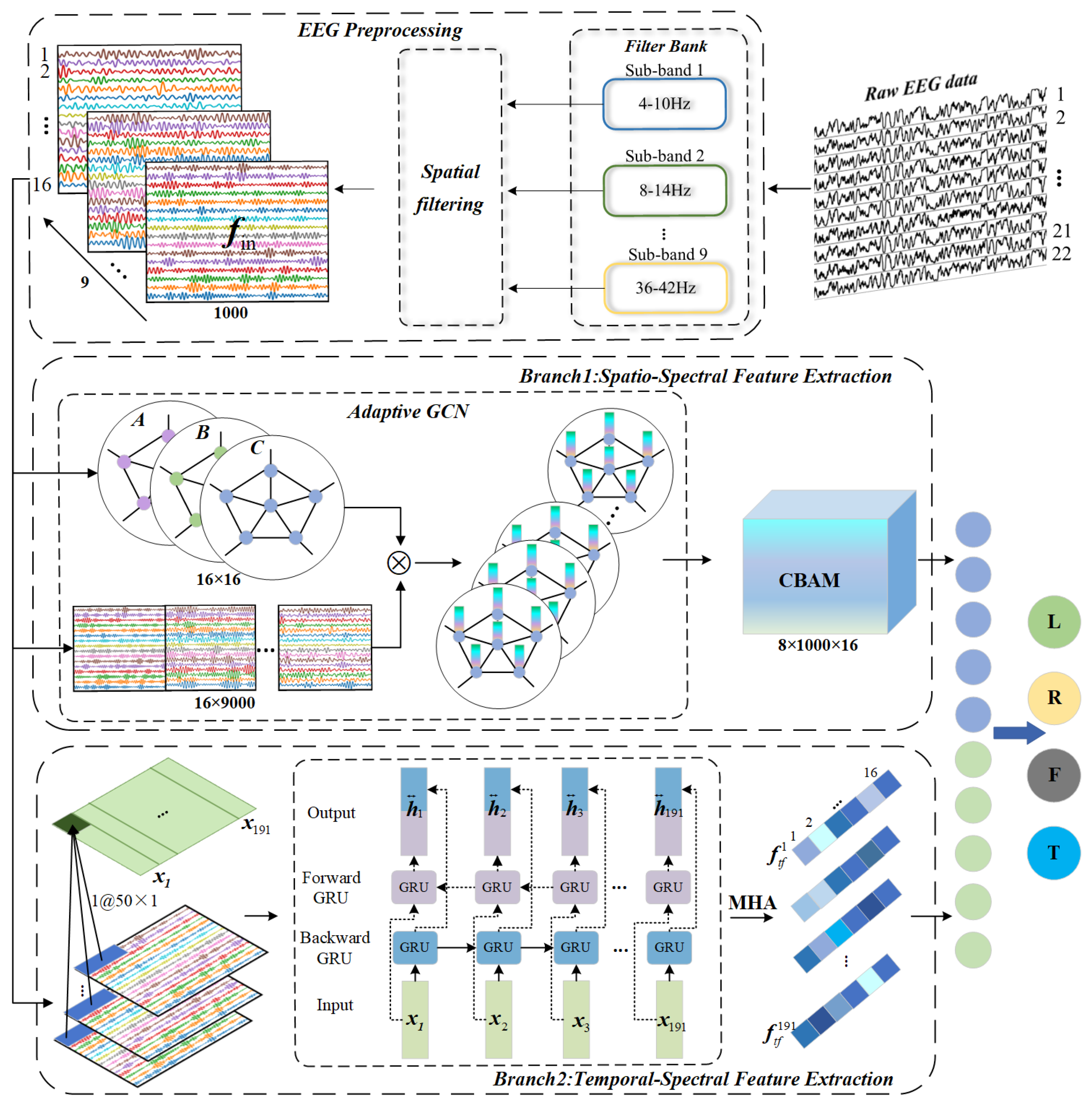

Decoding motor imagery electroencephalography (MI-EEG) signals presents significant challenges due to the difficulty in capturing the complex functional connectivity between channels and the temporal dependencies of EEG signals across different periods. These challenges are exac- erbated by the low spatial resolution and high signal redundancy inherent in EEG signals, which traditional linear models struggle to address. To overcome these issues, we propose a novel dual- branch framework that integrates an Adaptive Graph Convolutional Network (Adaptive GCN) and Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Units (Bi-GRU) to enhance the decoding performance of MI-EEG sig- nals by effectively modeling both channel correlations and temporal dependencies. The Chebyshev Type Il filter decomposes the signal into multiple sub-bands giving the model frequency domain insights. The Adaptive GCN, specifically designed for the MI-EEG context, captures functional connectivity between channels more effectively than conventional GCN models, enabling accurate spatial-spectral feature extraction. Furthermore, combining Bi-GRU and Multi-Head Attention (MHA) captures the temporal dependencies across different time segments to extract deep time-spectral features. Finally, feature fusion is performed to generate the final prediction results. Experimental results demonstrate that our method achieves an average classification accuracy of 80.38% on the BCI-IV Dataset 2a and 87.49% on the BCI-I Dataset 3a, outperforming other state-of-the-art decoding approaches. This approach lays the foundation for future exploration of personalized and adaptive brain-computer interface (BCI) systems.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

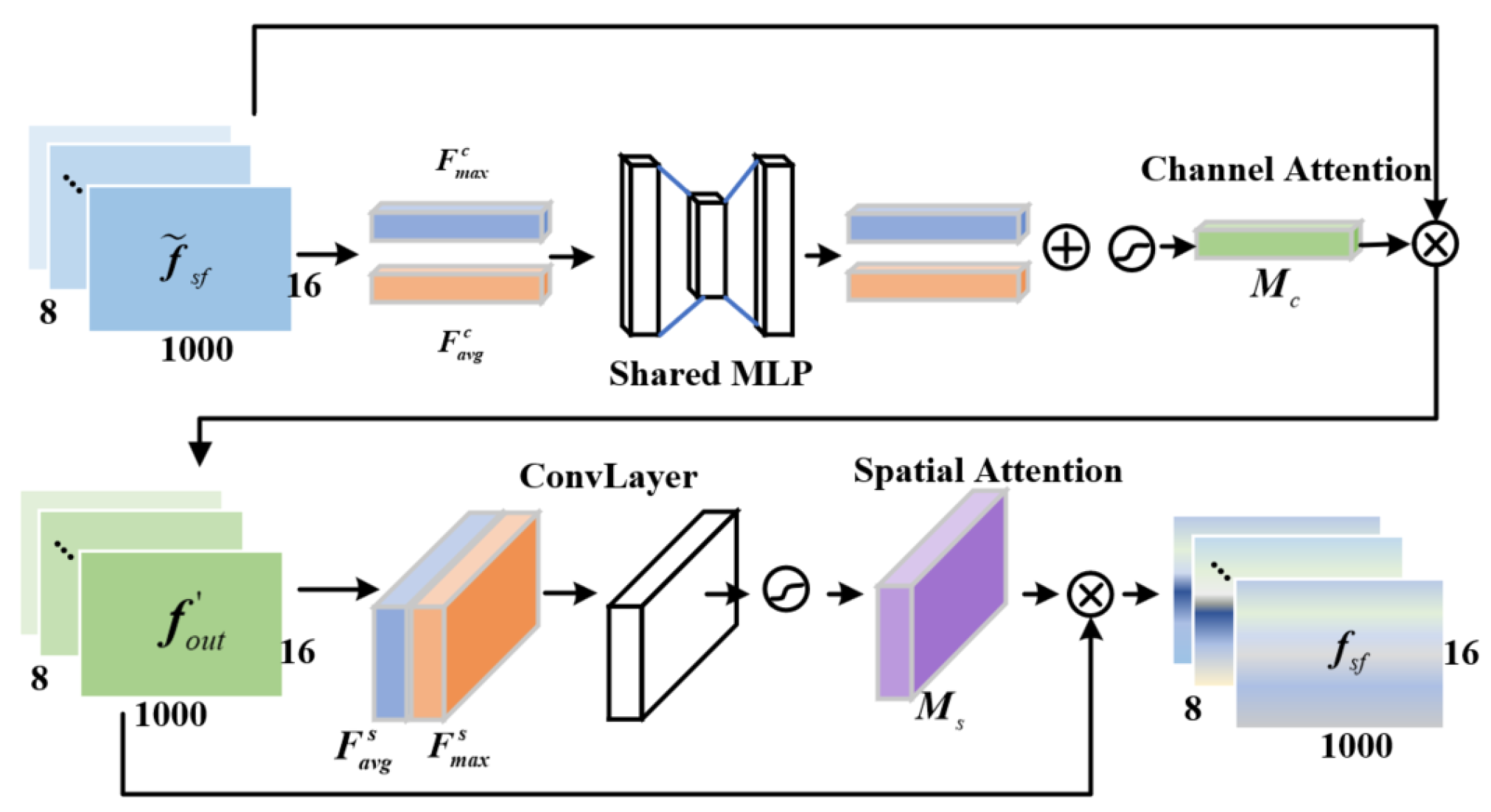

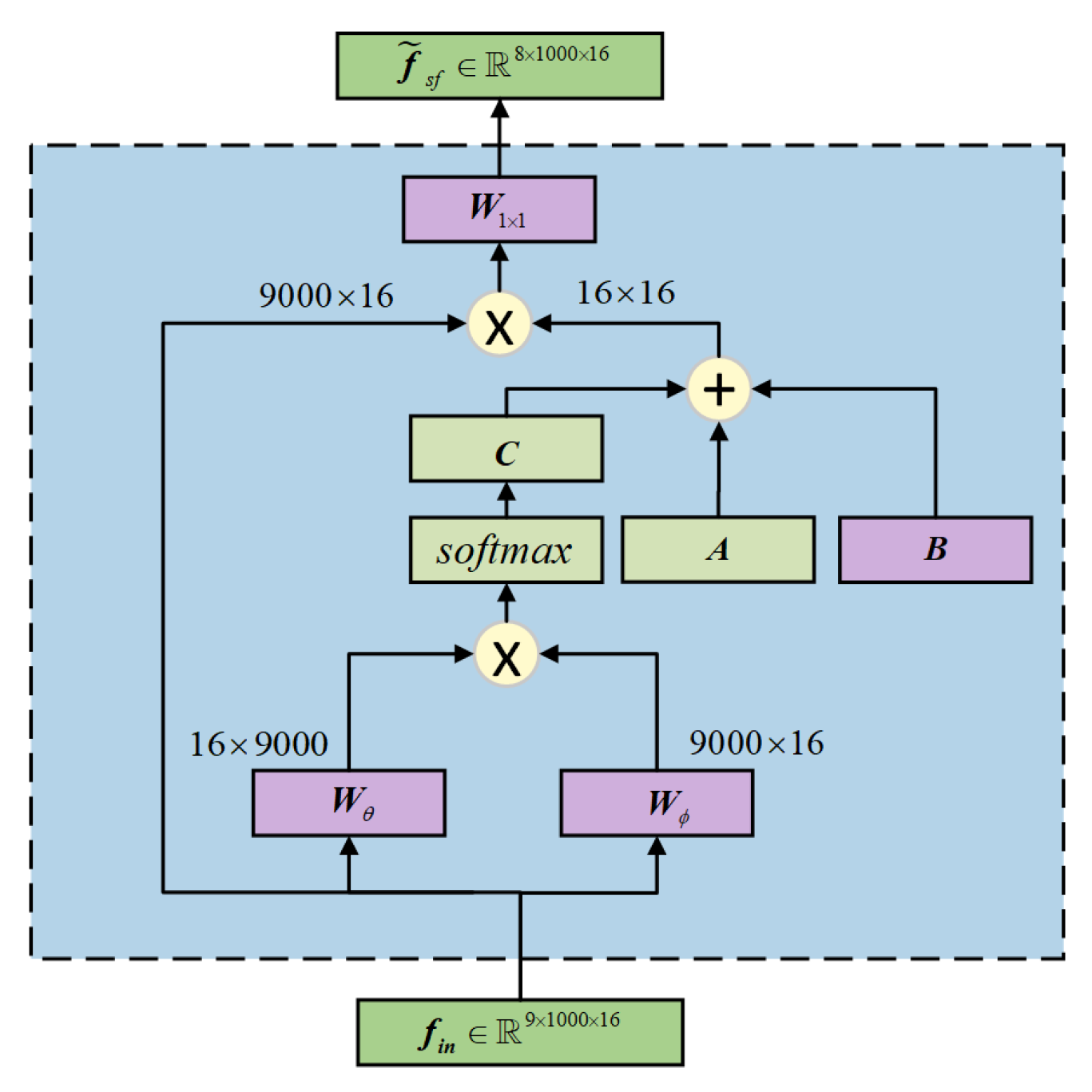

- An adaptive graph convolutional network is proposed, which constructs the graph convolutional layers of MI-EEG signals using a dynamic adjacency matrix. The CBAM is employed to focus on important features, capturing the synchronized activity states and dynamic processes of the brain, thereby improving the quality of spatial-temporal feature decoding.

- Propose a time-frequency feature extraction model to fully explore the sequential dependencies and global dependencies among features of different time segments. This study combines the bidirectional gated recurrent unit (Bi-GRU) with the multi-head self-attention mechanism to obtain deep-level time-frequency features.

- Experiments on multiple public EEG datasets show that, compared with state-of-the-art methods, the proposed model achieves significant improvements, enhancing the decoding quality of MI-EEG multi-classification tasks.

2. Materials and Methods

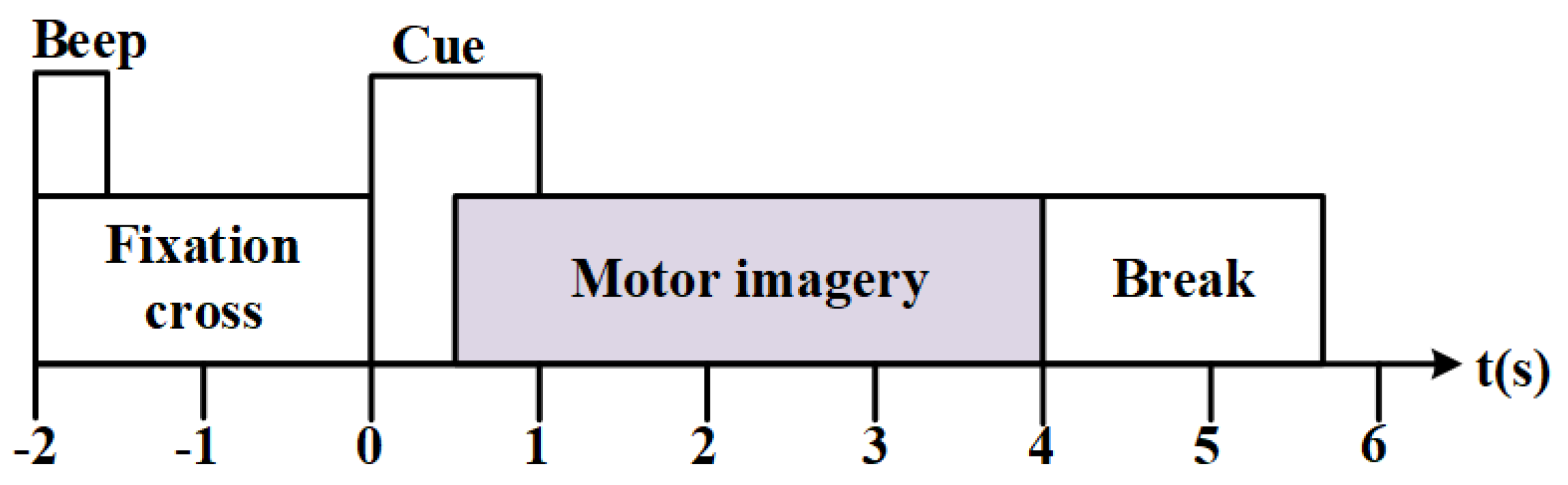

2.1. Dataset

2.2. Proposed Model Framework

2.3. Preprocessing

2.4. Spatio-Spectral Feature Extraction Module

2.5. Temproal-Spectral Feature Fxtraction Module

2.6. Feature Fusion

3. Results

3.1. Software and Hardware Environment

3.2. Classification Results

3.3. Ablation Experiments

3.4. Comparison Experiments of Adjacency Matrices

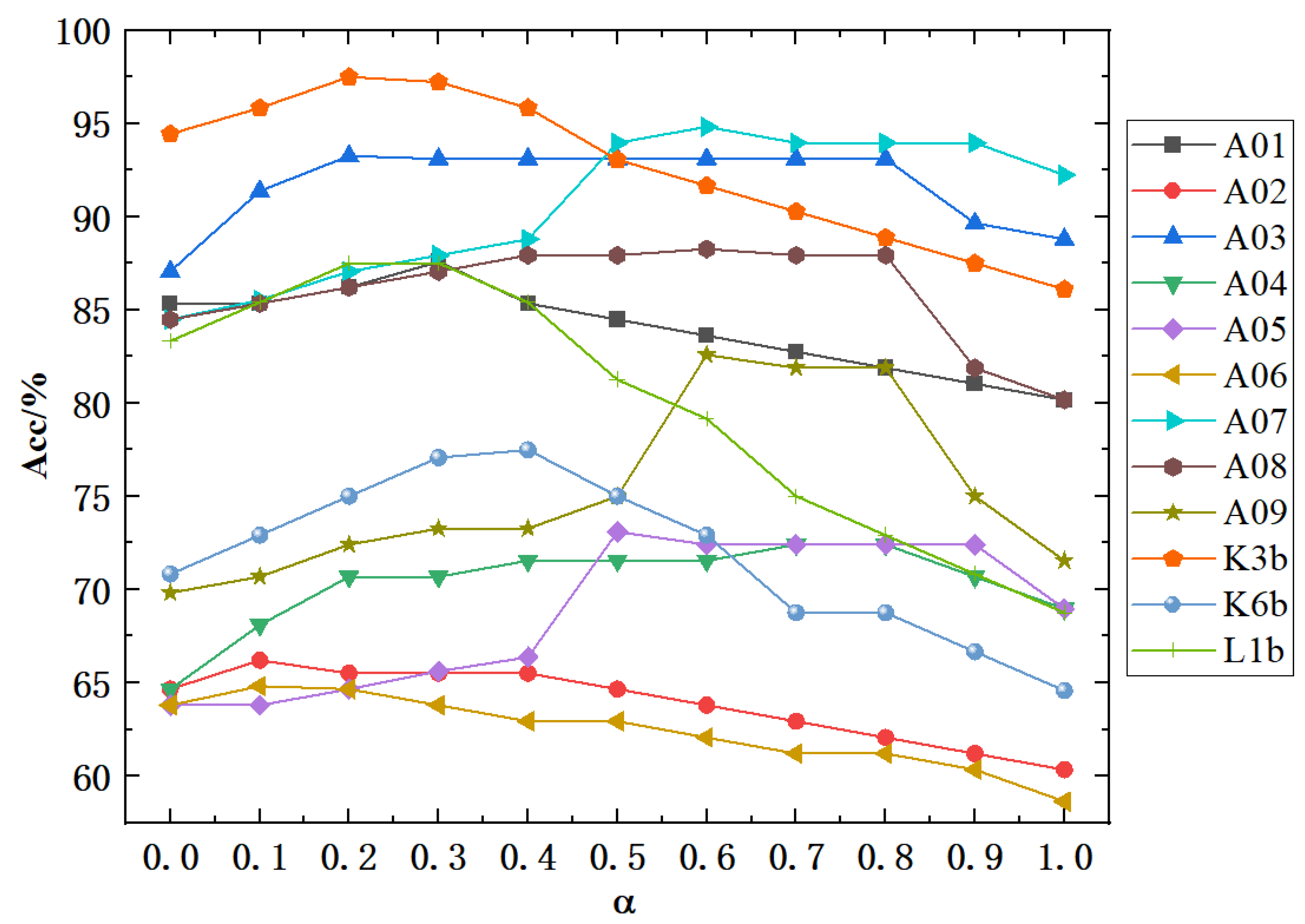

3.5. Effect of Self-Connection Coefficients

4. Discussion

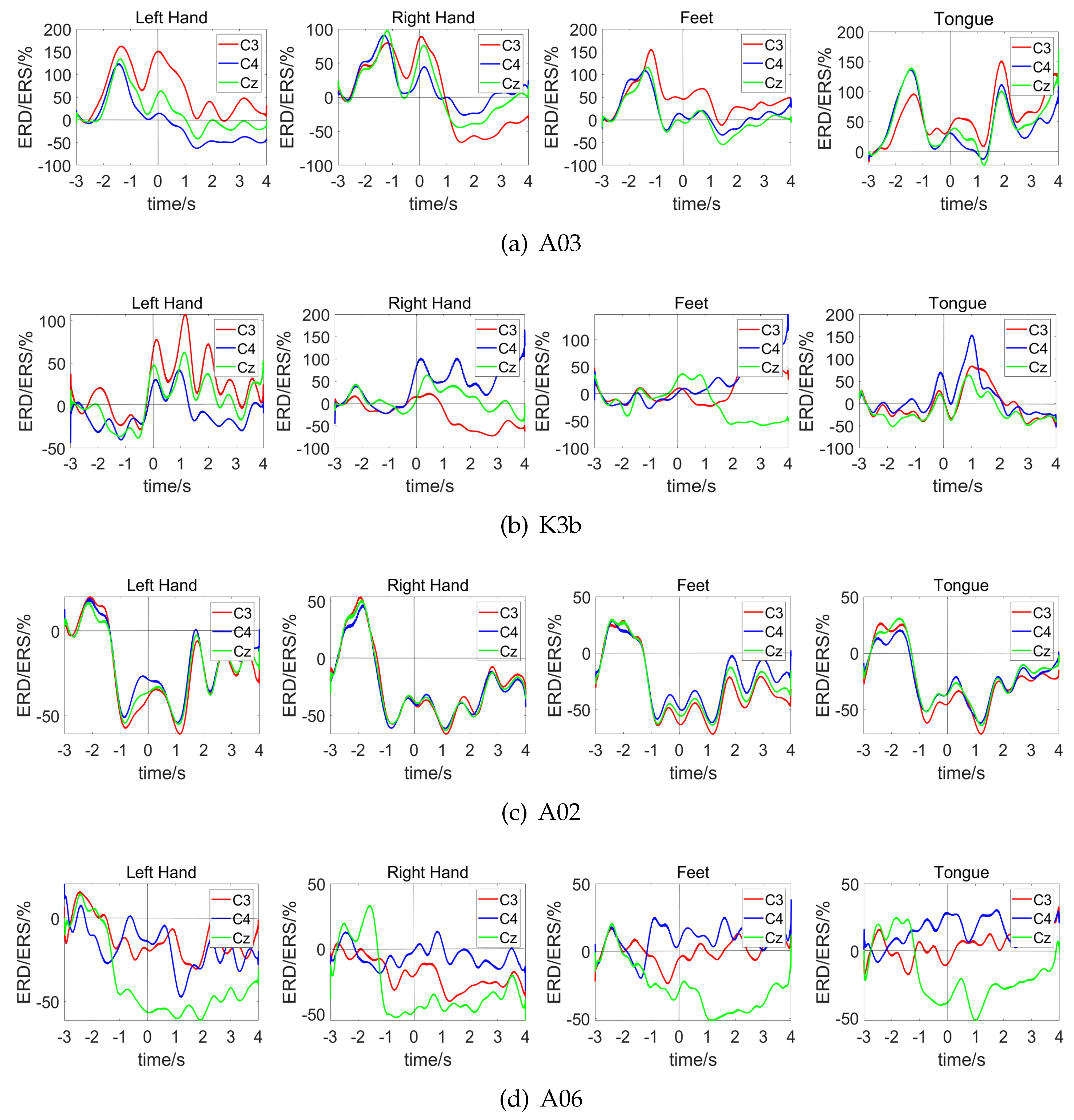

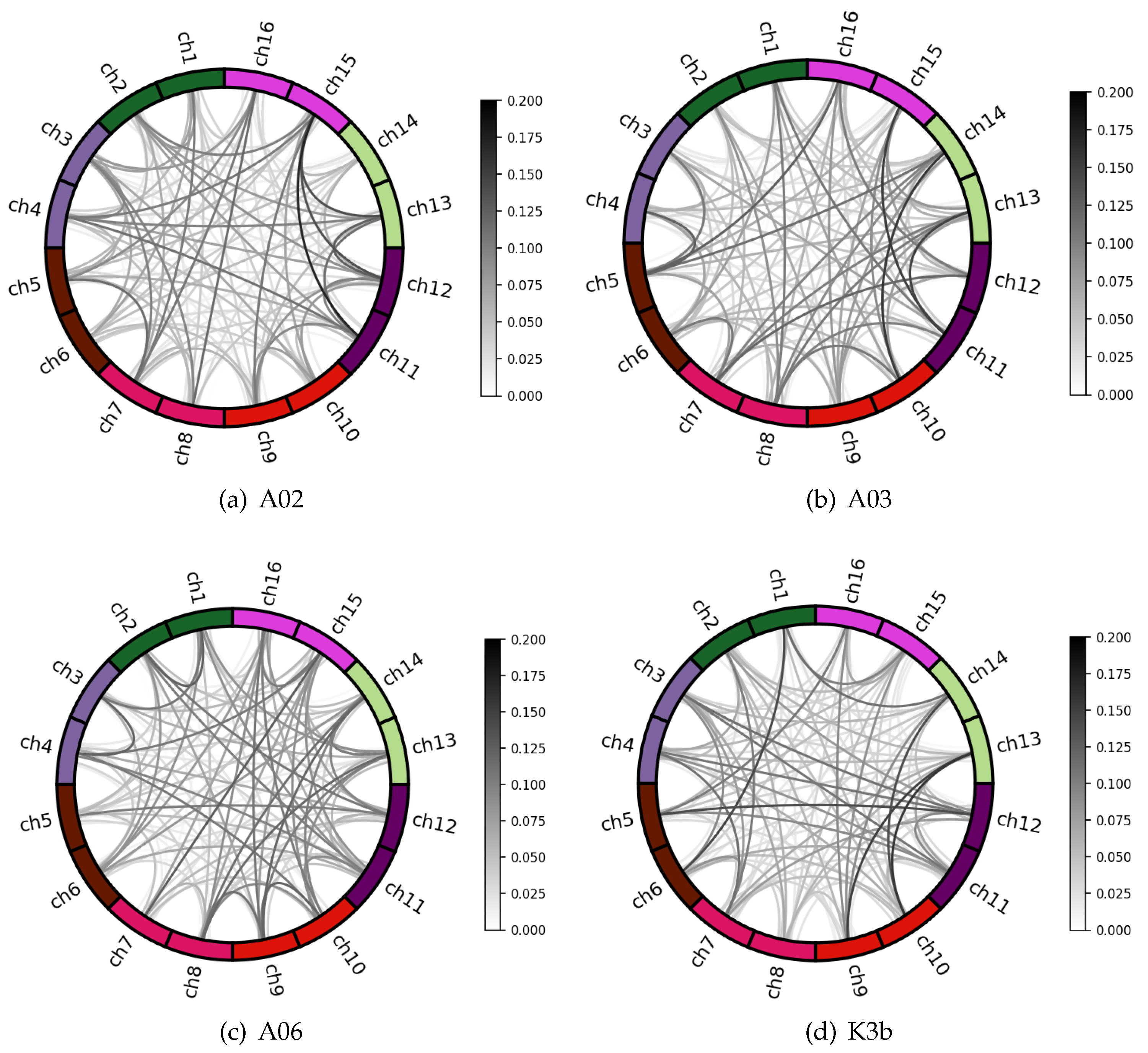

4.1. Channel Correlation Visual Analysis

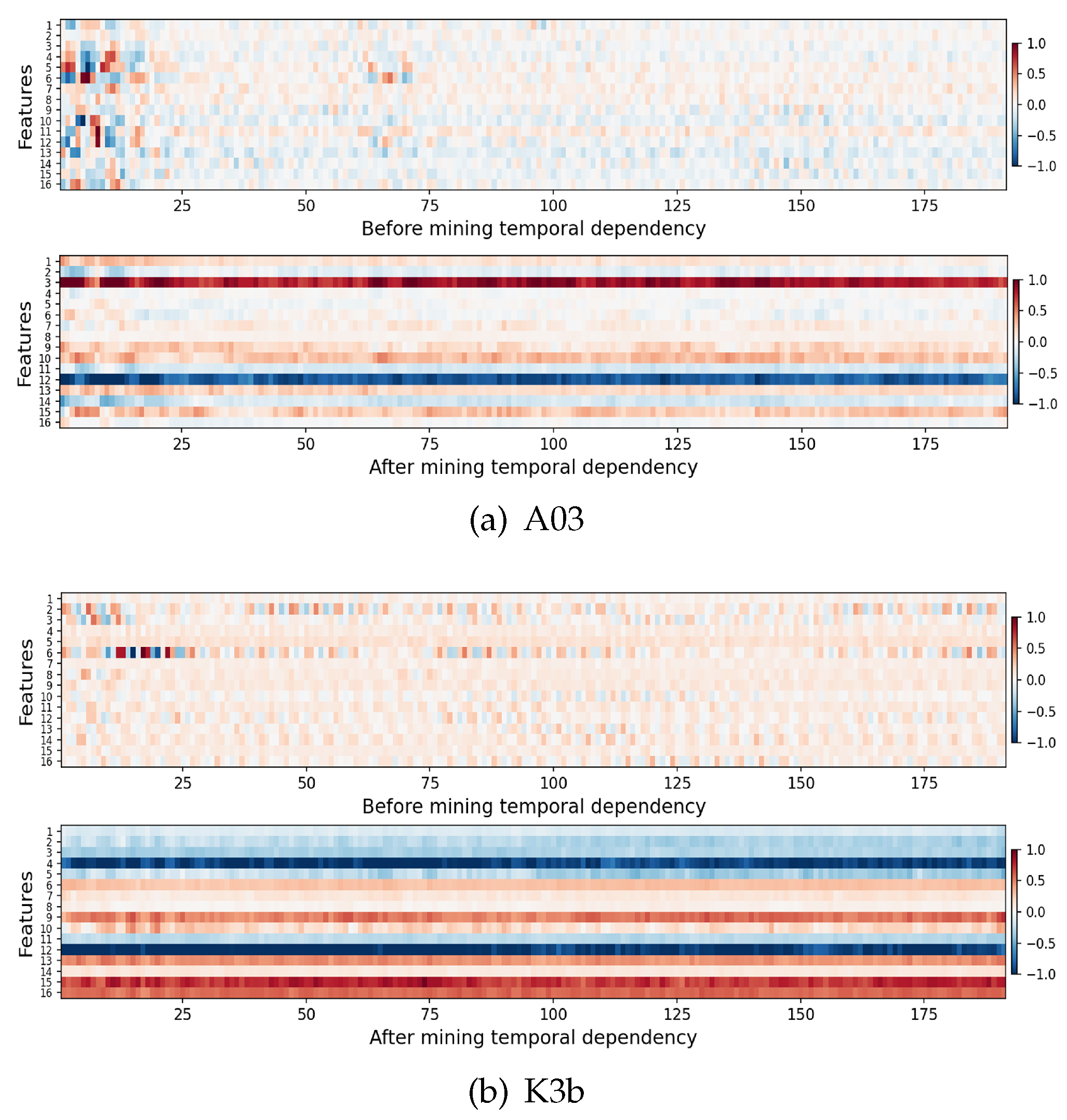

4.2. Time Dependence Visual Analysis

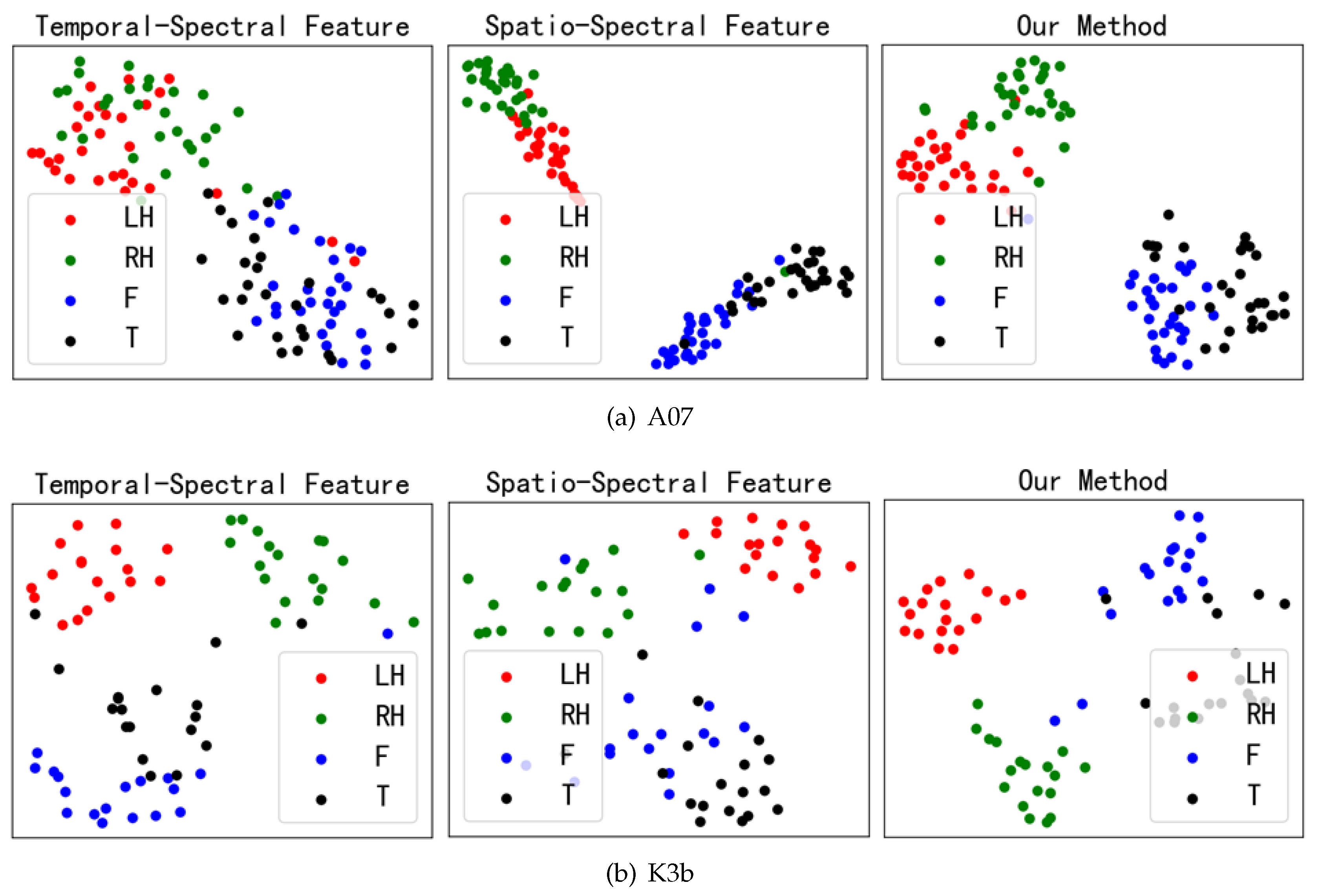

4.3. Feature Fusion Visual Analysis

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- J. R. Wolpaw and D. J. McFarland, “Control of a two-dimensional movement signal by a noninvasive brain-computer interface in humans,” Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, vol. 101, no. 51, pp. 17 849–17 854, Dec. 2004.https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.0403504101.

- K. Tanaka, K. Matsunaga, and H. O. Wang, “Electroencephalogram-based control of an electric wheelchair,” IEEE transactions on robotics, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 762–766, Aug. 2005.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1492493.

- Y. Wang, B. Hong, X. Gao, and S. Gao, “Implementation of a brain-computer interface based on three states of motor imagery,” in 2007 29th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE, 2007, pp. 5059–5062.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/4353477.

- K. LaFleur, K. Cassady, A. Doud, K. Shades, E. Rogin, and B. He, “Quadcopter control in three-dimensional space using a noninvasive motor imagery-based brain–computer interface,” Journal of neural engineering, vol. 10, no. 4, p. 046003, Aug. 2013.https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1741-2560/10/4/046003.

- C. Herff, D. Heger, A. De Pesters, D. Telaar, P. Brunner, G. Schalk, and T. Schultz, “Brain-to-text: decoding spoken phrases from phone representations in the brain,” Frontiers in neuroscience, vol. 8, p. 141498, Jun. 2015.https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2015.00217/full.

- C. Tang, T. Zhou, Y. Zhang, R. Yuan, X. Zhao, R. Yin, P. Song, B. Liu, R. Song, W. Chen et al., “Bilateral upper limb robot-assisted rehabilitation improves upper limb motor function in stroke patients: a study based on quantitative eeg,” European Journal of Medical Research, vol. 28, no. 1, p. 603, Dec. 2023.https://eurjmedres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40001-023-01565-x.

- M. Xu, X. Xiao, Y. Wang, H. Qi, T.P. Jung, D. Ming, “A brain-computer interface based on miniature-event-related potentials induced by very small lateral visual stimuli,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., vol. 65, no. 5, pp. 1165-1175, May 2018.

- J. Mei, R. Luo, L. Xu, W. Zhao, S. Wen, K. Wang, X. Xiao, J. Meng, Y. Huang, J. Tang et al., “Metabci: An open-source platform for brain–computer interfaces,” Computers in Biology and Medicine, vol. 168, p. 107806, Jan. 2024.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010482523012714?

- Z. J. Koles, M. S. Lazar, and S. Z. Zhou, “Spatial patterns underlying population differences in the background eeg,” Brain topography, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 275–284, 1990.https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01129656.

- K. K. Ang, Z. Y. Chin, H. Zhang, and C. Guan, “Filter bank common spatial pattern (fbcsp) in brain-computer interface,” in 2008 IEEE international joint conference on neural networks (IEEE world congress on computational intelligence). IEEE, 2008, pp. 2390–2397.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/4634130.

- M. Tavakolan, Z. Frehlick, X. Yong, and C. Menon, “Classifying three imaginary states of the same upper extremity using time-domain features,” PloS one, vol. 12, no. 3, p. e0174161, Mar. 2017.https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0174161.

- S. Liu, J. Tong, J. Meng, J. Yang, X. Zhao, F. He, H. Qi, and D. Ming, “Study on an effective cross-stimulus emotion recognition model using eegs based on feature selection and support vector machine,” International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics, vol. 9, pp. 721–726, May. 2018.https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13042-016-0601-4.

- Y. Zhang, B. Liu, X. Ji, and D. Huang, “Classification of eeg signals based on autoregressive model and wavelet packet decomposition,” Neural Processing Letters, vol. 45, pp. 365–378, Apr. 2017.https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11063-016-9530-1.

- P. Yang, J. Wang, H. Zhao, and R. Li, “MLP with riemannian covariance for motor imagery based eeg analysis,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 139 974–139 982, 2020.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9149576.

- P. Wang, A. Jiang, X. Liu, J. Shang, and L. Zhang, “LSTM-Based EEG classification in motor imagery tasks,” IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Reha Eng., vol. 26, no. 11, pp. 2086–2059, Oct. 2018.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8496885.

- T. Luo, C. Zhou, F. Chao, “Exploring spatial-frequency-sequential relationships for motor imagery classification with recurrent neural network,” BMC BIOINFORMATICS., vol. 19, p. 344, Sep. 2018.https://bmcbioinformatics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12859-018-2365-1.

- S. Alhagry, A. A. Fahmy, and R. A. El-Khoribi, “Emotion recognition based on eeg using lstm recurrent neural network,” International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, vol. 8, no. 10, Oct. 2017.https://www.proquest.com/docview/2656455515?

- L. Li and N. Sun, “Attention-based dsc-convlstm for multiclass motor imagery classification,” Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, vol. 2022, no. 1, p. 8187009, May. 2022.https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/2022/8187009.

- R. T. Schirrmeister, J. T. Springenberg, L. D. J. Fiederer, M. Glasstetter, K. Eggensperger, M. Tangermann, F. Hutter, W. Burgard, and T. Ball, “Deep learning with convolutional neural networks for eeg decoding and visualization,” Human brain mapping, vol. 38, no. 11, pp. 5391–5420, Nov. 2017.https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hbm.23730.

- V. J. Lawhern, A. J. Solon, N. R. Waytowich, S. M. Gordon, C. P. Hung, and B. J. Lance, “EEGNet: a compact convolutional neural network for eeg-based brain–computer interfaces,” Journal of neural engineering, vol. 15, no. 5, p. 056013, Oct. 2018.https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1741-2552/aace8c.

- X. Zhao, H. Zhang, G. Zhu, F. You, S. Kuang, and L. Sun, “A multi-branch 3d convolutional neural network for eeg-based motor imagery classification,” IEEE transactions on neural systems and rehabilitation engineering, vol. 27, no. 10, pp. 2164–2177, Oct. 2019.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8820089.

- H. Wu, Y. Niu, F. Li, Y. Li, B. Fu, G. Shi, and M. Dong, “A parallel multiscale filter bank convolutional neural networks for motor imagery eeg classification,” Frontiers in neuroscience, vol. 13, p. 1275, Nov. 2019.https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2019.01275/full.

- J. Zhang, X. Zhang, G. Chen, and Q. Zhao, “Granger-causality-based multi-frequency band eeg graph feature extraction and fusion for emotion recognition,” Brain Sciences, vol. 12, no. 12, p. 1649, 2022.https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3425/12/12/1649.

- J. Jia, B. Zhang, H. Lv, Z. Xu, S. Hu, and H. Li, “CR-GCN: channel-relationships-based graph convolutional network for eeg emotion recognition,” Brain Sciences, vol. 12, no. 8, p. 987, Dec. 2022.https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3425/12/8/987.

- W. Tian, M. Li, X. Ju, and Y. Liu, “Applying multiple functional connectivity features in gcn for eeg-based human identification,” Brain Sciences, vol. 12, no. 8, p. 1072, Aug. 2022.https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3425/12/8/1072.

- M. Vaiana and S. F. Muldoon, “Multilayer brain networks,” Journal of Nonlinear Science, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 2147–2169, Oct. 2020.https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00332-017-9436-8.

- J. Lv, X. Jiang, X. Li, D. Zhu, S. Zhang, S. Zhao, H. Chen, T. Zhang, X. Hu, J. Han et al., “Holistic atlases of functional networks and interactions reveal reciprocal organizational architecture of cortical function,” IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, vol. 62, no. 4, pp. 1120–1131, Apr. 2015.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6960842.

- J. Lv, V. T. Nguyen, J. van der Meer, M. Breakspear, and C. C. Guo, “N-way decomposition: Towards linking concurrent eeg and fmri analysis during natural stimulus,” in Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention- MICCAI 2017: 20th International Conference, Quebec City, QC, Canada, September 11-13, 2017, Proceedings, Part I 20. Springer, 2017, pp. 382–389.https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-66182-744.

- T. Zhang, X. Wang, X. Xu, and C. P. Chen, “GCB-Net: Graph convolutional broad network and its application in emotion recognition,” IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 379–388, Jan. 2022.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8815811.

- T. Song, W. Zheng, P. Song, and Z. Cui, “EEG emotion recognition using dynamical graph convolutional neural networks,” IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 532–541, 2018.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8320798.

- L. Chen and Y. Niu, “EEG motion classification combining graph convolutional network and self-attentiion,” in 2023 International Conference on Intelligent Supercomputing and BioPharma (ISBP). IEEE, 2023, pp. 38–41.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10061298.

- X. Tang, J. Zhang, Y. Qi, K. Liu, R. Li and H. Wang, “A Spatial Filter Temporal Graph Convolutional Network for decoding motor imagery EEG signals,” EXPERT SYSTEMS WITH APPLICATIONS, vol. 238, p. 121915, May. 2024.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S095741742302417X?

- Y. Li, L. Guo, Y. Qi, Y. Liu, J. Liu and F. Meng, “A Temporal-Spectral-Based Squeeze-and- Excitation Feature Fusion Network for Motor Imagery EEG Decoding,” IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON NEURAL SYSTEMS AND REHABILITATION ENGINEERING, vol. 29, pp. 1534–1545, 2021.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9495768.

- L. Zhao, X. Li, B. Yan, X. Wang, and G. Yang, “Study on feature modulation of electroencephalogram induced by motor imagery under multi-modal stimulation,” Journal of Biomedical Engineering, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 343–349, 2018.https://www.biomedeng.cn/article/10.7507/1001-5515.201708061.

- K. K. Ang, Z. Y. Chin, C. Wang, C. Guan, and H. Zhang, “Filter bank common spatial pattern algorithm on bci competition iv datasets 2a and 2b,” Frontiers in neuroscience, vol. 6, p. 21002, 2012.https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2012.00039/full.

- W. Ma, C. Wang, X. Sun, X. Lin, and Y. Wang, “A double-branch graph convolutional network based on individual differences weakening for motor imagery eeg classification,” Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, vol. 84, p. 104684, Jul. 2023.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1746809423001179?

- L. Shi, Y. Zhang, J. Cheng, and H. Lu, “Two-stream adaptive graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 12 026–12 035.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8953648.

- S. Wo, J. Park, J. Lee, I. Kweon, “CBAM: convolutional block attention module,” Computer vision -ECCV, pp. 3–19, 2018.https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-01234-21.

- X. Ma, W. Chen, Z. Pei, J. Liu, B. Huang, and J. Chen, “A temporal dependency learning cnn with attention mechanism for mi-eeg decoding,” IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 2023.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10196350.

- S. Yang, S. Chen, C. Liu, M. Li, M. Wang, and J. Wang, “A ship trajectory prediction model based on ECA-BiGRU,” in 2023 IEEE 8th International Conference on Big Data Analytics (ICBDA). IEEE, 2023, pp. 94–99.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10104909.

- I. Fung, B. Mark, “Multi-Head Attention for end-to-end neural machine translation,” in 2018 11th International Symposium on Chinese Spoken Language Processing (ISCSLP). 2018, pp. 250–254.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8706667.

- G. Pfurtscheller and A. Aranibar, “Evaluation of event-related desynchronization (ERD) preceding and following voluntary self-paced movement,” Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology, vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 138–146, 1979.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0013469479900634?

- G. Pfurtscheller, C. Brunner, A. Silva and Da. Silva, “Mu rhythm (de)synchronization and EEG single-trial classification of different motor imagery tasks,” Neuroimage, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 153–159, May. 2006.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1053811905025140?

- G. Pfurtscheller and F. L. Da Silva, “Event-related eeg/meg synchronization and desynchronization: basic principles,” Clinical neurophysiology, vol. 110, no. 11, pp. 1842–1857, 1999.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1388245799001418?

- Y. Song, Q. Zheng, B. Liu, and X. Gao, “EEG conformer: Convolutional transformer for eeg decoding and visualization,” IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, vol. 31, pp. 710–719, 2022.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9991178.

- D. Zhang, K. Chen, D. Jian, and L. Yao, “Motor Imagery Classification via Temporal Attention Cues of Graph Embedded EEG Signals,” in IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, vol. 24, no. 9, pp. 2570–2579, Sep. 2022.https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8961150.

- L. van der Maaten, G. Hinton, “Visualizing data using t-SNE,” J.Mach.Learn.Res., vol. 39, pp. 2579–2605, Nov. 2008.https://web.p.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?

| Parameters | Setting |

|---|---|

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Loss function | Categorical Cross-entropy |

| Learning rate | 0.01 |

| Batch size | 16 |

| Epochs | 100 |

| Subject | Acc% | Kappa | Precision% | Recall% | ||||||

| Left | Right | Feet | Tongue | Left | Right | Feet | Tongue | |||

| A01 | 88.18 | 0.834 | 94.26 | 90.37 | 84.59 | 83.47 | 86.89 | 93.79 | 84.14 | 85.51 |

| A02 | 66.21 | 0.549 | 57.57 | 53.04 | 87.25 | 68.57 | 60.00 | 51.72 | 84.13 | 68.96 |

| A03 | 93.26 | 0.910 | 90.67 | 99.31 | 92.99 | 91.20 | 97.93 | 95.86 | 88.96 | 90.34 |

| A04 | 72.41 | 0.632 | 69.61 | 70.34 | 77.41 | 74.36 | 68.96 | 70.34 | 82.07 | 68.27 |

| A05 | 73.09 | 0.641 | 83.38 | 75.87 | 64.32 | 71.01 | 71.03 | 88.96 | 61.38 | 71.03 |

| A06 | 64.65 | 0.528 | 64.90 | 60.42 | 68.69 | 67.11 | 66.21 | 59.99 | 65.51 | 66.90 |

| A07 | 94.82 | 0.931 | 95.20 | 95.92 | 94.03 | 94.51 | 93.79 | 96.55 | 95.17 | 93.79 |

| A08 | 88.27 | 0.843 | 87.96 | 84.99 | 88.94 | 92.62 | 94.48 | 91.72 | 81.38 | 85.51 |

| A09 | 82.58 | 0.767 | 78.92 | 85.84 | 80.62 | 87.54 | 89.65 | 71.72 | 78.62 | 90.34 |

| K3b | 97.49 | 0.966 | 100.0 | 96.84 | 94.84 | 98.94 | 97.77 | 100.0 | 98.88 | 93.33 |

| K6b | 77.49 | 0.699 | 75.34 | 70.34 | 75.12 | 90.86 | 63.33 | 71.66 | 85.00 | 90.00 |

| L1b | 87.49 | 0.833 | 91.60 | 90.86 | 81.98 | 70.09 | 86.66 | 95.00 | 81.66 | 86.66 |

| average | 82.16 | 0.761 | 82.45 | 81.18 | 82.56 | 82.52 | 81.39 | 82.27 | 82.24 | 82.55 |

| Dataset | Method | Acc% | Kappa |

| BCI-IV Dataset 2a | CSP+SVM | 63.22±17.08 | 0.508±0.230 |

| FBCSP+SVM | 69.25±15.49 | 0.589±0.206 | |

| Shallow ConvNet | 79.21±11.87 | 0.722±0.158 | |

| Deep ConvNet | 75.65±14.58 | 0.675±0.194 | |

| EEGNet | 70.49±15.68 | 0.606±0.209 | |

| EEG-Conformer | 79.18±9.625 | 0.722±0.128 | |

| LightConvNet | 74.54±12.20 | 0.659±0.164 | |

| Our method | 80.38±10.89 | 0.737±0.144 | |

| BCI-III Dataset 3a | CSP+SVM | 69.90±16.86 | 0.598±0.224 |

| FBCSP+SVM | 75.69±14.66 | 0.675±0.195 | |

| Shallow ConvNet | 80.08±14.39 | 0.734±0.191 | |

| Deep ConvNet | 81.57±8.614 | 0.754±0.114 | |

| EEGNet | 76.84±14.26 | 0.691±0.190 | |

| EEG-Conformer | 81.93±10.03 | 0.759±0.133 | |

| LightConvNet | 87.36±0.783 | 0.831±0.104 | |

| Our method | 87.49±8.164 | 0.833±0.108 |

| Dataset | Method | Precision% | Recall% | ||||||

| Left | Right | Feet | Tongue | Left | Right | Feet | Tongue | ||

| Dataset 2a | Branch1 | 73.26±15.71 | 72.38±17.68 | 72.19±12.54 | 76.95±12.34 | 72.48±17.72 | 71.64±19.20 | 73.33±14.78 | 73.56±12.27 |

| Branch2 | 71.32±16.60 | 71.62±14.10 | 67.88±10.90 | 72.25±13.27 | 70.88±16.88 | 70.72±20.62 | 69.23±10.90 | 68.73±10.55 | |

| Ours | 80.27±12.74 | 79.57±14.95 | 82.09±9.77 | 81.15±10.33 | 80.99±13.52 | 80.07±15.96 | 80.15±10.05 | 80.07±10.41 | |

| Dataset 3a | Branch1 | 88.42±7.45 | 71.81±14.32 | 74.21±10.21 | 78.69±14.22 | 69.44±29.57 | 83.88±21.67 | 76.10±15.29 | 81.84±8.121 |

| Branch2 | 72.81±19.62 | 78.09±16.64 | 77.96±8.830 | 81.10±9.475 | 75.55±23.14 | 77.22±20.65 | 68.51±13.83 | 82.59±4.286 | |

| Ours | 88.98±10.23 | 86.01±11.34 | 83.98±8.17 | 86.63±12.15 | 82.59±14.35 | 88.88±12.34 | 88.51±7.458 | 90.00±2.72 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).