1. Introduction

Investment inefficiency in listed firms, where ownership is distinct from management, tends to raise concern over their profitability (Revsine, 2002; Alsayegh et al., 2022). As a result of separation of ownership in corporate relationship, managers have the monopoly of information which they may conceal from investors. When this happens, investors may not have enough information to evaluate the probable risk and anticipated returns on their investments (Khan et al., 2024).

Investment efficiency, as conceptualised in this study, is the effective allocation and utilisation of resources for viable or profitable capital projects (Blanco et al., 2015; Ardianto et al., 2023). This concept is seen as a determining factor of the risk, cost, and overall profitability of an investment, as risks and returns are intervening parameters for measuring investment efficiency of firms (Biddle et al., 2009). While it is imperative for determining the growth of the firms, managers still find it difficult to balance risks and returns in their approach to taking investment decisions (Biddle et al., 2009; Al-Hadi et al., 2017). Based on this complexity involved in investment decision process, it is important for managers to select profitable projects that would reach optimal investment level, specifically devoid of over-investment or under-investment. Therefore, the investment that is worthwhile is one with higher anticipated yield over the cost of capital of firms (Blanco, 2011; Agoraki et al., 2024).

Cost of capital (CoC), which denotes the least rate of return expected by investors, is also essential in the investment evaluation process of firms. This is because an investment is considered viable only if the anticipated yield on capital invested is greater than the CoC (Blanco et al., 2015; Cho, 2015; Akinlo & Sule, 2020). Basically, studies have shown that reduced CoC offers firms diverse alternatives to fund their projects from external sources rather than internal sources or cash flow, which could translate into real opportunity to engage in diverse projects that will generate value (Abbas et al., 2018). In many developing economies, including Nigeria, the capital market is marked by high CoC (Adeyemi & Oboh, 2011; Uremadu & Onyekachi, 2019). Consequently, many firms in Nigeria rely on short-term loans for funding projects due to limited access to equity capital. This financial strain might make investors to perceive significant risks, which could diminish their interests in purchasing the firms’ shares due to the concerns that earnings will be diverted to debt repayment rather than dividends.

Investors’ loss of confidence in the growth prospects of firms has, thus, been attributed to inadequate disclosure practices of firms (Revsine et al., 2002; Al-Hadi et al., 2017). Major frauds involving big firms like Enron and Lehman Brothers have affected investors’ confidence in the disclosure practices of firms (Moncarz et al., 2016). As innovations in global business and technology advance, investors need comprehensive and transparent information about firms’ financial performance and business segment to make informed decisions. However, in Nigeria, there has been a growing concern over the inadequate disclosure practices of managers of firms, consequently impacting their performance in the stock market. This concern was affirmed by the collapse and takeover of some Nigerian firms, such as Intercontinental Bank, Diamond Bank and the delisting of Alumaco Nigeria Plc and Costain Plc from the Nigerian Exchange Group (NGX), resulting in investors’ loss of confidence in the disclosure practices of these firms (Opara, 2017).

Empirical findings have largely focused on the broader economic landscape of Nigeria, without adequate emphasis on investment efficiency of firms (Adelegan, 2009; Ajide, 2017). Also, extant research that focuses on the disclosure practices of firms specifically looked at related variables, such as CoC and governance, but not on its impact on investment efficiency of firms. Furthermore, other studies have only shown that Nigerian firms have not been completely transparent in their disclosure practices; however, they did not examine the impact on the investment efficiency of these firms (Adeyemi & Fagbemi, 2010; Akinlo & Sule, 2020). Against this background, this study empirically investigates the relationship between segment disclosure, CoC, and investment efficiency of Nigerian firms. This is with a view to analysing the potential impact of enhancing segment disclosure and lowering CoC in relation to improving the investment efficiency of firms, consequently resulting in investors’ confidence in the reporting practices of Nigerian firms.

2. Conceptual Review

2.1. Segment Disclosure

Segment disclosure (SD) is defined in accounting literature as the process of providing economic information about the financial and non-financial activities of firms’ business and geographic segments to investors (Owusu-Ansah, 1998; Shehata, 2014; Botosan et al., 2021). Within this framework, SD emerges as a crucial part of the economic information of firms. It plays an indispensable role in firms’ valuation and has drawn attention from researchers across different countries. In addition, the attention to SD has become increasingly popular in academic discussions within the field of accounting, because of its role in providing critical signals that guide capital investment decisions (Chen & Zhang, 2003; Elberry, 2018; Gao et al., 2018). Furthermore, both users of financial statements and standard setters have heightened their focus on how firms disseminate information about their operating segments. This is especially important given that there are divergent levels of profitability and growth in segments within a firm.

As defined in International Financial Reporting Standards 8 (IFRS 8, 2007), an operating segment is a constituent of a firm that undertakes business operations that generate revenues and incur expenditure. Consequently, such constituent is categorised as a reportable segment only if its revenue or loss accounts for 10 percent or more of its total revenue or loss. Increase in business expansion and diversification, coupled with demand for transparency from investors, has necessitated revision of the former IAS 14 and the consequent application of IFRS 8. The motivation for implementing IFRS 8 was that stakeholders should also have information about internal operation of the firms that manager uses in allocating resources to different segments (Mateescu, 2016).

IFRS 8 mandates listed firms to disclose economic information, such as its major products, geographical area in which it operates, management’s assessment of internal control system, and their main customers. Empirical findings have established that embracing these standards provides an array of benefits (Berger & Hann, 2003; Shehata, 2014; Elberry, 2018). It helps the assessment of firms by stakeholders who continuously demand disaggregated information about business and geographic segments of firms, because growth, opportunities, and risk vary across segments (Chen & Zhang, 2003). Also, SD reduces the level of information discrepancies between managers and stakeholders, particularly investors (Botosan, 1997). This, therefore, reduces firm’s cost of raising capital and sensitivity to cash flow (Healy & Palepu, 2001; Botosan & Stanford, 2005). It reduces the efforts of shareholders in monitoring the activities of managers and thereby boosts investment efficiency (Chen et al., 2011; Biddle & Hillary, 2006). Furthermore, SD decreases the cost of raising capital from external sources, which, in turn, lessens the volatility of investments to cashflows as engendered by internal activities and eventual under investment problems (Hope & Thomas, 2008). It also enables shareholders to investigate managers’ investment decisions that may sometimes result in unwanted over-investment (Biddle et al., 2009). Consequently, segment information is useful in discovering and discouraging investment choices that do not advance the value of firms (Blanco et al., 2015).

In contrast, firms that disseminate inadequate segment information tend to fund their projects with funds derived or generated internally. This is because these categories of firms see internal funds as a cheaper financial alternative, and such firms may not be able to expand and compete globally. Therefore, comprehensive SD is important, not only for transparency and accountability, but also for sustainability and growth in a rapidly evolving and competitive business environment.

2.2. Investment Efficiency

Investment efficiency can be defined as a situation in which firms implement all or part of a project that is considered worthwhile (Biddle et al., 2009). This implies that only projects with positive Net Present Value (NPV) are considered viable. This perspective is in tandem with the position of Biddle et al. (2009), who posited that investment efficiency is the measure of skewness from anticipated investment yields, adopting a model which expresses investment as a determinant of growth prospects. Thus, a negative skew from the anticipated return is considered as under-investment, while on the contrary, a positive skew is viewed as over-investment. In relation to CoC Blanco et al. (2015) argues that an investment is only considered viable, if the anticipated yield on capital invested is greater than the cost of financing it. Thus, an investor can filter out unviable investments, given a series of investment opportunities to optimise profit and enable the resourceful apportionment of capital in the economy (Chen & Zhang, 2003).

2.3. Cost of Capital

The cost of capital (CoC) is the minimum yield that investors demand for providing capital to a firm (Akinsulire, 2008). This metric is indispensable in corporate decision making and valuation, because it influences investment decisions by determining a firm’s growth potential, cash flow stability, and overall value creation (Domantas, 2010). According to Drake (2010), it is a firms’ costs of acquiring capital or funds from creditors and shareholders. Adequate knowledge of the capital blend of firms through financial reports decreases investors’ pessimism regarding the future prospect and profitability of firms. This is because shareholders tend to overestimate their expected return if they don’t have adequate information regarding the true parameter of their stock return. It is therefore logical and reasonable for firms to determine the proportion of their capital mix.

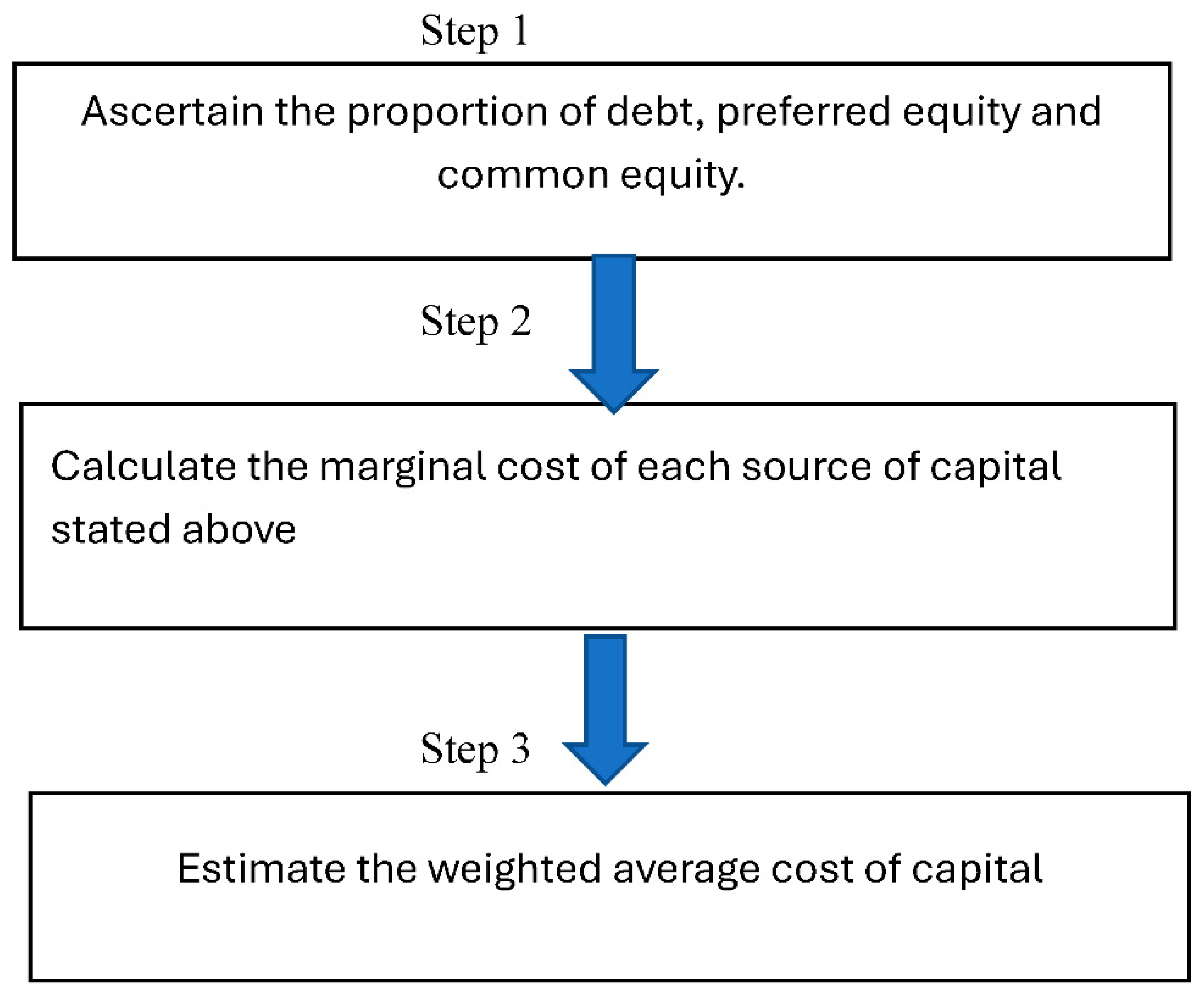

Figure 1 displays the steps that can be taken by firms to ascertain their capital mix.

3. Empirical Review

3.1. Extent of Segment Disclosure

Managers serve as custodians of segment information, and their discretion to disclose this information significantly impacts disclosure practices. Studies have revealed that agency and proprietary costs are two main determinants of the rate at which segment information is made available by managers (Harris, 1998; Prencipe, 2004; Botosan & Stanford, 2006). Beneath the agency intention, managers are inclined to conceal segment information to accomplish selfish motives leading to selective disclosure, which, one way or the other, tends to defeat the monitoring ability of investors or shareholders (Ben et al., 2011; Aboud & Diab, 2018).

Berger and Hann (2007) corroborated this view as they revealed that managers often conceal segment information regarding under-performing segments, because of agency and proprietary cost. This assertion was further given credence by Hope and Thomas (2008) when they opined that firms tend to conceal segment information regarding their foreign segments do so when such investment is not viable. Given a different perspective, Aboud and Diab (2018) revealed that reaction of investments to accessibility of internally generated cashflows is another determinant of SD.

Furthermore, Botosan and Plumlee (2006) investigated managers intention to conceal segment information and the consequent effect on analysts’ information environment using stipulated mandatory disclosure requirements in (SFAS) No. 131. They examined why managers conceal segment information for selected firms that initially reported as single segments. According to them, these categories of firms have tendencies to under-disclose, and analysts will benefit if they are mandated to disclose full segment information. The results revealed that firms might choose to under-disclose to protect profits and avoid competitive harm. However, this strategy can create the perception that the firms are underperforming, potentially allowing their competitors to outshine them in the long run.

3.2. Segment Disclosure and Cost of Capital

There is a continuous argument in literature on whether segment disclosure (SD) decreases the cost of capital (CoC) of firms around the world. Many empirical findings provide consistent evidence with previous studies leading to increased certainty regarding the negative relationship between CoC and SD (Mardini et al., 2013; Moldovan, 2016; He et al., 2019). Given the expected negative association between SD and CoC, it is anticipated that the advantages of SD, in terms of the reduced cost of financing, are imperative.

He et al. (2019) examined the link between CoC of firms and voluntary and mandatory disclosures. This research is different from previous studies because it further segmented mandatory disclosure into recurring and event-driven with the view to analyse profoundly, the impact of mandatory and voluntary disclosures on CoC.

Similarly, Hann et al. (2012) documented that multi-segment firms experience reduced CoC, because these firms disseminate more segment information, based on business and geographic levels of diversification. According to them, diversified firms tend to provide more segment information compared to stand-alone firms. They also investigated whether organisational arrangement affects firms’ CoC. Differing from conventional view, they affirmed that the likelihood of co-insurance among firms’ segments can mitigate systematic risk via the evasion of recurring deadweight expenditure. They found that multi-segment firms usually have a lower cost of financing while compared to a number of stand-alone firms. They further argued that diversified firms, with reduced correlated cashflows, also experience lower costs of capital like co-insurance impact. They assessed the utilised variables in the study, based on their prediction by introducing a sample size that comprises stand-alone and multi-segment firms spanning through the period 1988-2006. They employed Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) and Cost of Debt as proxy for CoC. Holding cashflow constant, their result suggests approximately 5% movement from high to low along the cashflow correlation quantile.

Lopes and Alencar (2010) compared disclosure level in the high disclosure environment like United States (US) to the low-disclosure environment like Brazil, based on the impact of disclosure on the CoC of firms in Brazil. They estimated that the connection between disclosed information and CoC as explained in extant studies can be ascribed to increased level of mandatory disclosure, which is prevalent in the US than developing countries. Using a self-developed Brazilian Disclosure Guide to measure the level of disclosed information and Price Earning Growth ratio based on Easton (2004), they measure CoC, using Capital Asset Pricing Method (CAPM) of the observed firms. Findings revealed that disclosure is greatly associated with CoC for Brazilian companies. Brazil presents higher standard deviation compared to other countries observed in the study with the value of 17.11 while the mean difference is 7.09. The study therefore concluded that findings are evidently significant for companies with less analyst monitoring and minimal ownership attention.

In another investigation by Botosan and Plumlee (2002) where they examined 3618 firms from the year 1985 to 1996 to ascertain the relationship between voluntary disclosure and CoC, it was revealed that a negative relationship exists between the two variables. In a related study, Kristandl and Bontis (2007) used 95 listed firms selected from Denmark, Austria, Sweden, Germany in 2005, and discovered a negative relationship between voluntary disclosure and CoC.

Botosan (1997) investigated the correlation between disclosure level and forecasted CoC. Considering a self-built disclosure index, the author explained the interplay between disclosure level and CoC acquisition in the US. The study differs from the previous studies in this area, because the author incorporated companies with little analysts monitoring. The author used data gathered from analysts based on the forecasts of future cashflows to predict future market expectations. By comparing companies with few analysts monitoring with high analysts monitoring, the study revealed that greater disclosure correlates with a reduced CoC (as low as 2.8%).

In contrast, Johnstone (2013) documented that disclosing more information could lead to higher CoC, due to operational or financial risks which the firm may be exposed to. In consonance, Bugeja et al. (2015) reported that firms may be reluctant to disseminate segment information if their segments are profitable and dissemination of this information can pose competition problems. Given this context, Blanco et al. (2015) concluded that, even though, increased SD reduces CoC, not all firms are motivated to go in this direction due to competitive disadvantage. Also, the study corroborated the assertion of Hope and Thomas (2008) that empire building managers do not mind high CoC as they prefer to pursue their own personal interest rather than disclose information for investors benefits.

In the Nigerian context, Ganiyu et al. (2019) delved into capital mix and firms’ performance. The study advanced the relationship between CoC and firms’ performance from a different viewpoint by considering the influence of agency relationship and debt financing, which deviates from most studies that only considered the monotonic relationship in terms of the impact of capital mix and firms’ performance. Based on the factors introduced, the study used Generalized Method of Moments to estimate the data extracted from 115 non-financial firms on the NGX. They revealed that firms in Nigeria rely on short debt financing to boosts capital and this limits their financial performance and investment exploration capacity.

3.3. Segment Disclosure, Cost of Capital, and Investment Efficiency

The primary purpose of financial reporting is to disseminate adequate and relevant financial information on all the components of firms to stakeholders, which will in turn facilitate efficient allocation of resources among segments. According to Botosan (2021) and Blanco et al. (2015), SD is useful to investors as it helps them in making complex investment decisions. As business environment is evolving and corporate structure and activities are becoming more complex, investors are not only demanding for the overall financial performance of firms, but increasingly demanding information about their various reportable and explainable business and geographic segments (Botosan & Stanford, 2006; Elberry, 2018). This is necessitated by the collapse of big corporations, such as Enron in 2001, which has negatively impacted investors’ trust in the economic reporting practices and integrity of firms. Part of the efforts to ameliorate these problems and restore investors’ confidence is the emphasis placed by standard setters on the need for a clear disclosure of the activities of every reportable segment in a firm. In effect, standard setters constantly converge to review financial disclosure policies and requirements to ensure transparency, accountability and reliability of financial reports (IFRS 8, 2007).

The introduction and serious campaign for the adoption of segment reporting has therefore necessitated increase in the volume of SD by firms to investors (Andre et al., 2016; Berger & Hann, 2003). Also, SD has now been considered as a way of disaggregating financial information in the financial statement of firms rather than the hitherto consolidated financial statement reporting. This, in a way, would prevent managers from masking unprofitable segments under the profitable ones as SD will certainly expose disparate risks and returns of each segment (Elsayed et al., 2019). Similarly, Hope and Thomas (2008) documented that the implementation of IFRS 8 has significantly enhanced SD as it has provided investors with important information to take decisions on investment. Furthermore, Balakrishnan et al. (2014) revealed that transparent disclosure tends to attract better investment conditions since capital providers are less likely to demand collateral. This effort, according to extant literature, is anticipated to invariably bridge the information gap in firms’ managers and investors relationship, thereby culminating in reduced CoC and improved investment efficiency (He et al., 2019; Hwang, 2019).

Also, CoC represents the minimum return that investors demand for granting capital to a firm (Blanco et al., 2015). It encompasses the costs associated with acquiring funds from creditors and shareholders (Drake, 2010). Cost of capital is critical for investment decisions, and it influences growth potential and cash flow stability (Domantas, 2010). Fundamentally, it connects anticipated dividends with share prices of firms, serving as a benchmark for evaluating investment opportunities. The resulting investment effect, according to Cho (2015) and Gao et al. (2018), is a drastic reduction in under-investment (inadequate investment) for firms that are not financially constrained. On the other hand, it is well anticipated that firms disclosing or providing improved segment information quality has lesser tendency to over-invest (Chen et al., 2011).

A viable investment must yield returns greater than its financing costs (Blanco et al., 2015). Firms can improve their investment decisions by analysing future returns and filtering out unviable projects. Similarly, Mashayekhi and Kalhornia (2019) documented a positive association between financial transparency and investment in a study conducted on Iranian firms from 2012 to 2015. In contrast, Abd-Elnaby and Aref (2019) explored the effects of accounting conservatism on investment efficiency in Egyptian firms and found that conservatism negatively impacted over-investment while positively influencing debt financing in under-invested firms.

Improved SD has been shown to reduce CoC by diminishing estimation risk and information gap, while also enhancing investment efficiency (Blanco et al., 2015). According to Andre et al. (2016), SD provides signals guiding capital investments by highlighting profitability variations across segments. Higher quality disclosure can lead to reduced adverse selection risks, thereby increasing market liquidity. Research by Abbas et al., (2015) revealed that quality SD significantly lower equity capital costs among listed companies. Furthermore, enhanced disclosure quality correlates with positive economic outcomes, such as improved investment decision efficiency (Peláez, 2011). However, Bushman and Smith (2001) argue that transparency enhances investment efficiency primarily when agency conflicts are absent.

Despite the recognised impact of SD on CoC and investment efficiency, academic research exploring this phenomenon remains diverse and inconclusive. Some research focused on the relationship between investment efficiency and SD (Cho, 2015; Elberry 2018; Gao et al., 2018; Chen, 2011). Some others have explored the impact of SD on CoC (Blanco et al., 2015; Saini, 2010). Scholars in developed countries like Basu et al. (1999) and Hope et al. (2009) have provided insights into firms’ financial reporting practices and investment efficiency. This relationship is well documented in developed economies but requires further exploration in developing contexts like Nigeria. This study, therefore, investigates the relationships between SD and CoC as they affect investment efficiency of listed firms in Nigeria.

4. Theoretical Underpinning and Hypothesis Development

4.1. Signaling Theory

Investment inefficiency can trigger high CoC for firms, as investors may request higher returns to mitigate potential risks (Majeed et al., 2018). To mitigate the CoC, firms must disclose adequate information regarding capital across projects, particularly in each segment. Extant studies have used several theories to explain the link between investment efficiency and SD of firms. These theories include, but are not constrained to agency theory, information asymmetry theory, stakeholder theory, and signaling theory (Komara et al., 2019). The most suitable theories for this study, based on the reviewed literature, are agency and signaling theories. These theories provide theoretical background and elucidation on why firms disclose their investment values and prospects to investors to make informed investment decisions.

Signaling theory postulates that firms deliberately send signals about their plans to investors to avoid information asymmetry (Yasar et al., 2020). These deliberate signals are sent to investors to bridge information gaps between the management who have more information and investors who have less information. By strategically disseminating segment information, firms can signal their growth potential across different business and geographic segments. For instance, if a firm sends positive information about a particular segment, it signifies good management practices, making investors to understand and exploit the prospect of the firm’s low-risk investment profile. On the other hand, a negative signal may imply high-risk investment profile, and consequently undermine investing in the firm. Therefore, signaling provides an opportunity for investors to make informed decisions given the perceived value of the firm. This will consequently reduce the CoC of firms as investors are not likely to demand high returns for capital provided if their risk profile is low. By providing adequate SD, firms can boost their credibility and reduce anticipated risks that relate to their business operations. Firms can gain investors’ trust with positive reporting practices and potentially lower their CoC and improve investment efficiency through signaling (Svetek, 2022).

4.2. Agency Theory

This theory was propounded by Jensen and Meckling in 1976. This theory posits that divergence of interest arises between managers and investors as managers tend to advance their interests over investors’ interests (Meiryani et al., 2023). Agency relationship exists between managers and investors because investors do not participate in the daily activities of firms. The obligation of the day-to-day activities of a firm rests with the managers. Once shareholders have invested their capital in firms, self-centred managers may take decisions that would give them more incentives, thereby expropriating investors’ resources (Botosan, 2002). The misalignment of interest between managers and investors tends to culminate into inefficiencies in investment decisions, which can only be mitigated by adequate SD (Botosan & Standford, 2006). Therefore, from the perspective of the agency theory, it could be argued that adequate SD potentially reduces CoC and boosts investment efficiency. Against this backdrop, the proposed hypotheses for this study are:

H1. There is a positive relationship between segment disclosure and investment efficiency.

H2. There is a negative relationship between cost of capital and investment efficiency.

5. Methodology

A total of 85 listed companies were purposively selected from 12 key sectors in the Nigerian Exchange Group (NGX). The analysis spanned from 2015 to 2022, utilising secondary data and a longitudinal research design. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were applied, including Pooled OLS, fixed effects, and random effects estimators. The suitability of these methods was evaluated using the Hausman test, while the t-test was employed to determine the impact of SD and CoC on investment efficiency of the selected firms.

A total of 42 disclosure items adapted from Mardini et al. (2013) and Blanco et al. (2015) were used to determine the Total Segment Disclosure (TSD) of the firms. Mandatory Segment Disclosure (MSD), Voluntary Segment Disclosure (VSD), and Total Segment Disclosure (TSD) were calculated using the formula below:

Model Specification

To determine the investment efficiency of the firms, this study regressed total segment disclosure (TSD), cost of capital (CoC) and other control variables on investment efficiency (INV_EFF).

The model for this relationship is therefore expressed below:

The model stated above was adapted from Biddle et al. (2009).

Where TSDit denotes the total segment disclosure (SD) by firm in year i over the period t.

INV-EFF is the investment efficiency of the firms. CoC is the cost of capital, Sizeit stands for the size of the firm, cashfl is cashflow, Tang is tangibility of firms, Prof is the profitability of the firms, and MTB is market-to-book ratio.

Table 1 presents the measurement methods for the variables examined in the study. It includes the formulas used to measure the main variables such as total segment disclosure, investment efficiency, cost of capital and control variables.

6. Findings and Discussions

6.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of all the variables examined in 85 listed firms on NGX from 2015 to 2022, which culminated in 680 firm-year observation. A total of 42 disclosure items adapted from Mardini et al. (2013) and Blanco et al. (2015) were used to assess the TSD of firms. TSD (total segment disclosure) represents the addition of mandatory and voluntary disclosure of firms from 2015 to 2022. The mean, minimum and maximum values for TSD, as presented in

Table 2 is 18.18, 13.00, and 24.00, respectively. If these values are compared to the total disclosure index (42) used to assess the extent of SD in the study, it is evident that the disclosure level of firms is low, given the mean value of 18.18. Furthermore, the mean age of the firms is 23.7, the minimum is 1, while the maximum age is 60. This implies the youngest of the firms was a year as of 2015, the base year of the study and the oldest was 60 years. Also, this shows that some of the firms have been operating for many years, while others are relatively new. This gives further credence to the difference in the extent of SD by firms as researchers have posited that older firms disclose more segment information since they tend to expand their business, based on their years of operation. Furthermore, the average firm size is 18.78billion. The firm with the smallest size is worth 5.76billion, while the biggest firm is worth 35.5 billion, and SD is 9.40. This denotes that the sample comprises of big and small firms as SD showed a wide disparity among size of the firms. Furthermore,

Table 2 reports the mean investment efficiency of the firms as 0.3367, minimum as 0.0700 and maximum as 0.4700. According to Leowenstein (1988), firms’ extent or optimum level of investment efficiency should be 100%. Hence the investment level that is below 100% is categorised as under-investment or low investment efficiency, while above 100% is considered over investment. With all the firms presenting below 100%, it implies that the level of investment efficiency of the examined firms can be considered low. The MTB of firms on average is 0.88, maximum the maximum is 3.45 and minimum 0.20. This means that the stock price of the observed firms is high. Also, the average tangibility of firms is 0.29, while the minimum tangibility of firms is 0.15, and maximum value of 0.46.

6.2. Correlation Matrix Analysis

Table 3 presents the pairwise correlation matrix of the effects of SD and CoC on investment efficiency of firms. This revealed the kind of association that exists among the dependent variable which is INV_EFF and the independent variables which are CoC, TSD, PROF, SIZE, GROWTH, TANG, MTB, CASHFL, and AGE. Based on the correlation test carried out in

Table 3, investment efficiency and CoC are negatively correlated (-0.24). This implies that CoC has a strong negative relationship with investment efficiency. Also, profitability showed a positive (0.1269) and significant (0.0009) correlation with investment efficiency. In contrast, there is a positive association (0.1512) between investment efficiency and TSD.

Furthermore, there is a positive and insignificant correlation between investment efficiency and size (Corr= 0.0235, pvalue= 0.5402). In a similar manner, growth and tangibility exhibited a positive and insignificant correlation with investment efficiency (corr= 0.0512, pvalue= 0.1824), (corr= 0.0293, pvalue= 0.4456) respectively. In contrast, Market to Book ratio and cash flow are positively and significantly correlated with investment efficiency with (corr= 0.0639, p-value= 0.0960) and (corr= 0.2619, p-value= 0.0000) respectively. Lastly, AGE is positively but not significantly connected with investment efficiency.

6.3. Effect of Segment Disclosure and Cost of Capital on Investment Efficiency

Based on the results in

Table 4, the Hausman test yielded a p-value of 0.865 for fixed effect. Since this p-value exceeds the 0.05 threshold, the study opted for the results of the random effects estimation method. The findings from the random effect method indicate that the CoC has a negative and statistically significant effect on investment efficiency (Coefficient = -0.0268, p-value = 0.03079). This validates hypothesis 2 by showing that a lower cost of capital will help firms to attain a favourable level of investment. The result finds support in the study of Blanco et al. (2015), Biddle et al. (2009) and Elberry (2018). Furthermore, the Total Segment Disclosure (TSD) of the examined firms showed a positive and significant impact on their investment efficiency (Coefficient = 0.0119, p-value = 0.0303). This finds support in previous studies conducted by Botosan (2000), Balakrishnan et al. (2014) which documented that increased SD enhances investment efficiency by providing investors with more information to make management accountable for their investment decisions. In contrast to many previous studies, profitability, which is a control variable, exhibited a negative and significant effect (coefficient = -0.0126, P-value = 0.0001) on investment efficiency. This indicates that for the firms observed, an increase in profitability did not translate into improved investment efficiency.

Similarly, firm size showed a positive and significant effect on investment efficiency (Coefficient = 0.004274, p-value = 0.0835), suggesting that larger firms are better positioned to invest optimally. This finding is consistent with Chen and Zhang’s (2003) conclusion that larger firms tend to achieve more efficient investments. Growth also displayed a positive and significant correlation with investment efficiency (Coefficient = 0.025811, p-value = 0.0272). This implies that increase in the growth rate of firms contributes positively to their investment efficiency, corroborating earlier findings that suggest growth enables firms to diversify and invest in viable projects. In terms of tangibility, the analysis revealed a negative and insignificant relationship with investment efficiency (Coefficient = -0.025731, p-value = 0.2539).

Furthermore, findings revealed that MTB positively impacts investment efficiency, but the effect is not significant (Coefficient = 0.003543, p-value = 0.2583). In contrast, cashflow positively (Coefficient = 0.08035) and significantly (p-value = 0.0016) impacts on the investment efficiency of the firms. This result finds support in the study of Huang and Tarkom (2022) as they documented that improved cashflow tends to provide capital for firms to engage in diverse capital projects that would add value to them. Lastly, the age of the firms showed a positive (Coefficient = 0.0097) and significant (p-value = 0.0571) relationship with investment efficiency. This implies that older firms tend to have capital for investment purposes than younger firms. This finding is corroborated by the findings of Blanco (2015).

7. Conclusions

The study found that there is a positive and significant relationship between the SD of the observed firms and their investment efficiency. In contrast, CoC negatively impacts on investment efficiency of the sampled firms. These findings imply that improved SD will, in many cases, boost investors’ confidence, reduce CoC and consequently culminate in investment efficiency for the firms. Therefore, management of firms should improve their SD practices. Lastly, standard setters and regulatory bodies should also ensure that firms comply with disclosure regulations to further boost investors’ confidence and for investors to invest in firms that positively impacts the society.

7.1. Policy Implications

The findings of this study offer valuable empirical insights into the importance of increased segment disclosure in listed firms. First, the positive and significant impacts of segment disclosure on investment efficiency suggests that firms that prioritise investors interest, by disseminating segment information, can make more efficient investment decisions. This is possible as investors will be able to monitor investment viability across segments and dissuade managers from making investment decisions that are not in their interest. Additionally, the negative relationship between CoC and investment efficiency indicates that improved SD leads to reduced CoC for firms, which, in many cases, translates into investment efficiency. By increasing segment disclosure, listed firms can attain an optimal level of investment. Lastly, this research is a pointer to standard setters to broaden disclosure requirements for firms and emphasise the importance of compliance with segment disclosure standards by firms.

7.2. Limitations of the Study and Future Research Directions

Despite the empirical contributions of this study, there are limitations to be pointed out. This study utilised data of firms from different sectors, which could cause significant variations in the data and eventual outcome. Future research could focus on sector-by-sector analysis using examined variables in this study. By analysing the data within individual sectors, researchers can reduce variability and allow for an in-depth analysis of firms in the same business environment. Additionally, future research might as well introduce the influence of other variables, such as auditors influence, listing status, and so on.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

This study utilised secondary data of companies which were downloaded from the Nigerian Exchange Group (NGX) website.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbas, N.; Ahmed, H.; Malik, Q.A.; Waheed, A. Impact of investment efficiency on cost of equity: An empirical study on Shariah and non-Shariah compliance firms listed on Pakistan Stock Exchange. Administrative Review 2018, 2, 307–322. [Google Scholar]

- Abd-Elnaby, H.; Aref, O. The Effect of Accounting Conservatism on Investment Efficiency and Debt Financing: Evidence From Egyptian Listed Companies. Int. J. Account. Financ. Rep. 2019, 9, 116–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboud, A.; Diab, A.A. The impact of social. environmental and corporate governance disclosure on firm value evidence from Eqypt. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 2018, 8(4), 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelegan, O.J. (2009). Capital market development and investment efficiency in Nigeria. Savings and Development, 113-132. https://aisberg.unibg.it/retrieve/handle/10446/27432/9075/ADELEGAN%202-2009.

- Adeyemi, S.B.; Fagbemi, T.O. Audit quality. corporate governance and firm characteristics in Nigeria. International Journal of Business and Management. [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, S.B.; Oboh, C.S. Perceived relationship between corporate capital structure and firm value in Nigeria. International Journal of Business and Social Science 2011, 2, 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Agoraki, K.K.; Giaka, M.; Konstantios, D.; Negkakis, I.; Negkakis, G. The relationship between firm-level climate change exposure, financial integration, cost of capital and investment efficiency. J. Int. Money Financ. 2023, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajide, F.M. Firm-specific, and institutional determinants of corporate investments in Nigeria. Futur. Bus. J. 2017, 3, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinlo, O.O.; Sule, D.F. Voluntary disclosure and cost of equity capital in Nigerian banks: an empirical study. Ife Journal of Economics and Finance 2019, 8, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hadi, A.; Hasan, M.M.; Taylor, G.; Hossain, M.; Richardson, G. Market Risk Disclosures and Investment Efficiency: International Evidence from the Gulf Cooperation Council Financial Firms. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2016, 28, 349–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayegh, M.F.; Rahman, R.A.; Homayoun, S. Corporate Sustainability Performance and Firm Value through Investment Efficiency. Sustainability 2022, 15, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, P.; Filip, A.; Moldovan, R. Segment disclosure. quality and quantity under IFRS 8: Determinant and the effects on financial analysts’ earnings forecast errors. International Journal of Accounting 2016, 51, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardianto, A.; Anridho, N.; Ngelo, A.A.; Ekasari, W.F.; Haider, I. Internal audit function and investment efficiency: Evidence from public companies in Indonesia. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, K.; Core, J.E.; Verdi, R.S. The Relation Between Reporting Quality and Financing and Investment: Evidence from Changes in Financing Capacity. J. Account. Res. 2013, 52, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Kim, O.; Lim, L. (1999). The usefulness of industry segment information’, Working paper, Baruch College-City University of New York. https://www/researchgate.net/publication/228306664_The_Usefulness_of_Industry_Seg ment_Information.

- Bens, D.A.; Berger, P.G.; Monahan, S.J. Discretionary Disclosure in Financial Reporting: An Examination Comparing Internal Firm Data to Externally Reported Segment Data. Account. Rev. 2011, 86, 417–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P.; Hann, R. The impact of SFAS No. 131 on information and monitoring. Journal of Accounting Research 2003, 41, 163–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P.G.; Hann, R.N. Segment Profitability and the Proprietary and Agency Costs of Disclosure. Account. Rev. 2007, 82, 869–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, G.C.; Hilary, G. Accounting Quality and Firm-Level Capital Investment. Account. Rev. 2006, 81, 963–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, G. C., Hilary, G. & Verdi, R. S., (2009). How does financial reporting quality improve investment efficiency? Journal of Financial Economics, 48, 112-131. [CrossRef]

- Blanco, B.; García, L.; Juan, M.; Tribo, G.; Joseph, A. Segment disclosure and cost of capital. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 2014, 42, 367–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botosan, C.A. Disclosure level and the cost of equity capital. The Accounting Review 1997, 72, 323. [Google Scholar]

- Botosan, C.A. Evidence. that greater disclosure lowers the cost of equity capital. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 2000, 12, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botosan, C.A.; Plumlee, M.A. A Re-examination of Disclosure Level and the Expected Cost of Equity Capital. J. Account. Res. 2002, 40, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botosan, C.A.; Stanford, M. Managers' Motives to Withhold Segment Disclosures and the Effect of SFAS No. 131 on Analysts' Information Environment. Account. Rev. 2005, 80, 751–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botosan, C.A.; Huffman, A.; Stanford, M.H. The State of Segment Reporting by U.S. Public Entities: 1976–2017. Account. Horiz. 2020, 35, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugeja, M.; Czernkowski, R.; Moran, D. The Impact of the Management Approach on Segment Reporting. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2015, 42, 310–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushman, R.M.; Smith, A.J. Financial accounting information and corporate governance. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 32, 237–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A. (2003). Quality of financial reporting choice: determinants and economic Consequences. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Hope, O.-K.; Li, Q.; Wang, X. Financial Reporting Quality and Investment Efficiency of Private Firms in Emerging Markets. Account. Rev. 2011, 86, 1255–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.F.; Zhang, G. Heterogeneous Investment Opportunities in Multiple-Segment Firms and the Incremental Value Relevance of Segment Accounting Data. Account. Rev. 2003, 78, 397–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J. Segment Disclosure Transparency and Internal Capital Market Efficiency: Evidence from SFAS No. 131. J. Account. Res. 2015, 53, 669–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domantas, S. (2010). Practical approach to estimating cost of capital. University library of Munich, Germany. https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:pra:mprapa:31011.

- Drake, P. (2010). A reading prepared by Pamela Peterson Drake. J.J Newberry. https://books.google.com.ng/books?hl=en&lr=&id=4zqgXdITQuAC&oi=fnd&pg=PR13&dq=info:05Js4eVN6N4J:scholar.google.

- Easton, P.D. PE Ratios, PEG Ratios, and Estimating the Implied Expected Rate of Return on Equity Capital. Account. Rev. 2004, 79, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elberry, N.S. (2018). Corporate investment efficiency, disclosure practices and governance. Doctoral thesis, University of Portsmouth. https://researchportal.port.ac.uk/en/studentThe ses/corporate-investment-efficiency-disclosure-practices-andF-governance.

- Elsayed, N.; Ammar, S.; Mardini, G.H. The impact of ERP utilization experience and segmental reporting on corporate performance in the UK context. Enterprise information systems 2019, 15(1), 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easley, D.; O'Hara, M. Information and the Cost of Capital. J. Financ. 2004, 59, 1553–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.; Nanda, D.J.; Olsson, P. Voluntary disclosure, earnings quality, and costs of capital. Journal of Accounting Research 2008, 46, 53–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Sidhu, B.K. The Impact of Mandatory International Financial Reporting Standards Adoption on Investment Efficiency: Standards, Enforcement, and Reporting Incentives. Abacus 2018, 54, 277–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganiyu, O.Y.; Adelopo, I.; Rodionova, Y.; Samuel, L.O. Capital structure and firm performance in Nigeria. African Journal of Economic Review 2019, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Hann, R.N.; Ogneva, M.; Ozbas, O. (2012). Corporate Diversification and the Cost of Capital. Journal of Finance, Forthcoming, Marshall School of Business Working Paper No. FBE 32-09, Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University Working Paper No. 58, AFA 2011 Denver Meetings Paper. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1364481. [CrossRef]

- Hail, L. The impact of voluntary corporate disclosures on the ex-ante cost of capital for Swiss firms. Eur. Account. Rev. 2002, 11, 741–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hail, L.; Leuz, C. International Differences in the Cost of Equity Capital: Do Legal Institutions and Securities Regulation Matter? J. Account. Res. 2006, 44, 485–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M. (1998). The association between competition and managers' business segment reporting choices. Journal of Accounting Research. Spring, 111-128.

- He, J.; Plumlee, M.A.; Wen, H. Voluntary disclosure, mandatory disclosure and the cost of capital. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2018, 46, 307–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P.M.; Palepu, K.G. Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 31, 405–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, O.; Thomas, W.B. Managerial Empire Building and Firm Disclosure. J. Account. Res. 2008, 46, 591–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Tarkom, A. Labor investment efficiency and cash flow volatility. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H. (2019), Essays on corporate disclosure and organizational structure. Working paper, Tepper school of business, Carnegie, Mellon University.

- IFRS 8 (2007). Operating Segments. International Accounting Standards Board. https://www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/publications/pdfstandards/english/2022/issued/part- a/ifrs-8-operating-segments.pdf?

- Johnstone, D.J. (2013). Information, uncertainty and the cost of capital in a mean- variance efficient market. Working Paper (Sydney: University of Sydney).

- Khan, M.A.; Yau, J.T.-H.; Sarang, A.A.A.; Gull, A.A.; Javed, M. Information asymmetry and investment efficiency: the role of blockholders. J. Appl. Account. Res. [CrossRef]

- Komara, A.; Ghozali, I.; Januarti, I. (2020, March). Examining the firm value based on signaling theory. In 1st International Conference on Accounting, Management and Entrepreneurship (ICAMER 2019) (pp. 1-4). Atlantis Press.

- Kristandl, G.; Bontis, N. The impact of voluntary disclosure on cost of equity capital estimates in a temporal setting. J. Intellect. Cap. 2007, 8, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, W.; Coles, J. Equilibrium pricing and portfolio composition in the presence of uncertain parameters. Journal of Financial Economics 1988, 7, 279–303. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, A.B.; Alencar, R.C. Disclosure and cost of equity capital in emerging markets: the Brazilian case. SSRN Electronic Journal 2010, 45, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardini, G.H.; Tahat, Y.A.; Power, D.M. Determinants of segmental disclosures: evidence from the emerging capital market of Jordan. Int. J. Manag. Financ. Account. 2013, 5, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashayekhi, B.; Kalhornis, H. (2019). Relationship between financial reporting transparency and investment efficiency: Evidence from Iran. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology. https://ideas.repec.org/a/hur/ijarbs/v4y2014i6p104-113.

- Mateescu, R. , (2016). Segment disclosure practices and determinants: Evidence from Romanian listed companies. The International Journal of Management Science and Information Technology (IJMSIT), 20, 40-50. https://hdl.handle.net/10419/178824.

- Majeed, M.A.; Zhang, X.; Umar, M. Impact of investment efficiency on cost of equity: evidence from China. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2018, 12, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiryani, S.; Huang, S.M.; Soepriyanto, G.; Jessica, S.; Fahlevi, M.; Grabowska, S.; Aljuaid, M. The effect of voluntary disclosure on financial performance: Empirical study on manufacturing industry in Indonesia. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0285720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldovan, R. (2015). Three essays on operating segment disclosure. Essex Business School.

- Cabello, A.; Moncarz, E.; Moncarz, R.; Moncarz, B. The rise and collapse of Enron: financial innovation, errors and lessons. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Nagar, V.; Nanda, D.; Wysocki, P. Discretionary disclosure and stock-based incentives. J. Account. Econ. 2003, 34, 283–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, N.B.; Street, D.L.; Tarca, A. The Impact of Segment Reporting Under the IFRS 8 and SFAS 131 Management Approach: A Research Review. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2013, 24, 261–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, S. (2017), March 5. 15 firms delisted from Nigerian Stock Exchange in 2016. Punch Newspaper. https://punchng.com/15-firms-delisted-from-nigerian-stock-exchange-in-201 6-report/#google_vignette.

- Owusu-Ansah, S. The impact of corporate attribites on the extent of mandatory disclosure and reporting by listed companies in Zimbabwe. Int. J. Account. 1998, 33, 605–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prencipe, A. Proprietary costs and determinants of voluntary segment disclosure: evidence from Italian listed companies. Eur. Account. Rev. 2004, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffournier, B. The determinants of voluntary financial disclosure by Swiss listed companies. Eur. Account. Rev. 1995, 4, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revsine, L.; Collins, D.; Johnson, B. (1999). Financial reporting and analysis, Prentice Hall International, London. https://books.google.co.za/books/about/Financial_Reporting_and_Analysis.html?

- Richardson, A.J.; Welker, M. Social disclosure, financial disclosure and the cost of equity capital. Account. Organ. Soc. 2001, 26, 597–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, J.S. (2010). Cost of equity capital, information asymmetry, and segment disclosures’, Doctoral Thesis, Oklahoma State University. [CrossRef]

- Serghiescu, L.; Văidean, V.-L. Determinant Factors of the Capital Structure of a Firm- an Empirical Analysis. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 15, 1447–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, N.F. Theories and Determinants of Voluntary Disclosure. Account. Financ. Res. 2013, 3, p18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetek, M. Signaling in the context of early-stage equity financing: review and directions. Ventur. Cap. 2022, 24, 71–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uremadu, S.O.; Onyekachi, O.; Yanar, Y. The Impact of Capital Structure on Corporate Performance in Nigeria: A Quantitative Study of Consumer Goods Sector. Curr. Investig. Agric. Curr. Res. 2018, 5, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valta, P. Competition and the cost of debt. J. Financ. Econ. 2012, 105, 661–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhu, Z.; Hoffmire, J. (2015). Financial reporting quality, free cash flow and investment efficiency. EDP Sciences, SHS Web Conferences, 701027. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Tarkom, A. Labor investment efficiency and cash flow volatility. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasar, B.; Martin, T.; Kiessling, T. An empirical test of signalling theory. Manag. Res. Rev. 2020, 43, 1309–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).