1. Introduction

Rare earth elements (REE) represent an important family of critical elements of technology. REE are used for various electronic components such as semiconductors, plasma screens, LED and batteries (Smith Stegen, 2015). Indeed, REE share unique conductive, magnetic, luminescent and catalytic properties that support electronic components function and durability. As a consequence, REE are extracted at large scales over the world reaching some 300 000 tons in 2022 (Duchna and Cieślik 2022). During their extensive extraction and inclusion in various electronic devices that are ultimately discarded in solid disposal sites, REEs are now considered as emerging contaminants of emerging concerns (MacMillan et al. 2017). On the one hand, the relative composition of REE found in mine contaminated lakes differs from those found in municipal wastewaters draining solid waste disposal sites (Hanana et al., 2022; Turcotte et al., 2022). For example, the major REEs from 10 mining contaminated lakes consists of La, Ce, Pr, Nd and Sm with a total loading of 580 µg/L at concentration ratios like those found in the Earth’s crust (Beaubien, 2015). These REEs are operationally called mining REE mixture and re-enter the environment through disposal of consumer and industrial products from landfills and wastewater discharged from both domestic and industrial processes (Gwenzi et al., 2018). However the major REEs composition differs in the municipal effluents and at much lower concentration. The 5 major REEs from 6 municipal effleunts consist of Gd, Ce, Nd, Yb and Dy at concentration ratios differing from the Earth crust composition with a mean total REE concentration of 13.7 µg/L. These REEs are operationally termed urban REE mixture characterized by the Gd anomaly (Inoue et al., 2020). Gd is used as contrast agent during magnetic resonance imaging and is released mostly in the dissolved phase (urine elimination) in wastewater treatment plant (Brunjes and Hofman, 2020). The toxicity of the mining REE mixture (at the same relative concentration found in contaminated lakes) was recently examined in Hydra attenuata and revealed antagonistic (competitive ?) interactions between the REEs based on the individual toxicity profiles of each REE (Hanana et al., 2022). Nevertheless, the mining mixture reduced reproduction, head regeneration and irreversible morphology (mortality) at concentrations below than those reported in contaminated lakes. However, the toxicity of the urban mix has yet to be examined to determine whether the urban REE mixture poses similar toxic risk to hydra.

Hydra vulgaris Pallas, 1766 belongs to the Hydrozoa class of the Cnidaria phylum and found in freshwaters. This organism has been cultivated in the laboratory since the 1950s (Loomis, 1954) and more recently used as bioassay to investigate the toxicity of various xenobiotics and liquid mixtures (Fatima et al., 2024; Vimalkumar et al., 2022). The hydra are relatively small organisms between 2-10 mm length composed of a tubular body with a head composed of 7 tentacles (

Figure S1). They fed on small preys such as copepods and other zooplankton. The hydra are unisexual ands reproduce by budding of polyps which will eventually detach and form an independent organism with doubling times from 4-5 days up to 20 days depending on the cultivation methods. They have unique regenerative abilities, growing and reproducing without aging (Blaise and Kusui, 1997; Ghaskadbi 2020). Hydras are simple organism composed of 2 layers of epithelial cells making them very sensitive to environmental attacks by various contaminants. An attractive feature of the hydra bioassay is that the intensity in toxicity could be visually observed by characteristic alterations in morphology (

Figure S1). First, tentacles for a button/bud at the the tip and retract (less long) followed by severe tentacle contraction at the body forming a tulip-like appearance followed by disintegration of the body. Tentacle budding and retraction are considered reversible (sublethal) changes as the regenerate when the stressor is removed from the media. Severe tentacles formation, tulip stage and, of course, body disintegration are consirered irreversible (lethal) exceeding the organism’s ability to regenerate. The hydra is considered a sensitive test species for ecotoxicity testing (Blaise et al., 2018; MacKinley et al. 2019) surpassing the rainbow trout toxicity test (Dubé et al., 2019) most notably for metals and rare earth elements. The small size of these organisms complicates investigations at the biomolecular level, requiring an important amount of starting material or highly sensitive means. Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) represents a very sensitive and species methodology for quantifying specific mRNA targets. A novel quantitative RT-PCR methodology was developed to determine the effects of xenobiotics on the gene expression involved in oxidative stress, oxidated DNA (guanosine) repair, protein salvaging and tagging by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, autophagy, cell regeneration and neural activity. The analysis of gene expression changes preceding changes in morphology could be of predictive value to prevent toxicity and better understand the mode of action of environmental contaminants.

The purpose of this study was to examine the sublethal and lethal toxicity in Hydra vulgaris of a realistic urban mixture composed of the following most abundant rare earth elements in municipal effluents: gadolinium, cerium, neodynium, ytterbium and dysprosium. The sublethal toxicity was examined the morphological and molecular levels to better understand the mode of action of REE mixtures that precedes morphological alterations. An attempt was made to determine the threshold concentrations of molecular changes that occur before the onset of altered morphology in hydra.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

Pure powders of the REE (Gd(III), Ce(III), Nd(III), Yb (III) and Dy(III)) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (On, Canada). The were prepared in the following proportion based on the reported concentrations (dissolved phase) found in Canada wastewater effluents (Turcotte et al., 2022): Gd (105 ng/L), Ce (9 ng/L), Nd (8 ng/L), Yb (6.2 ng/L) and Dy (4 ng/L) corresponding to total REE loading of 137 ng/L. This mixture is referred as the urban mixture where the 1 X mixture represents the actual concentrations of REE in the dissolved phase in municipal effluents. These concentrations are relatively low and far beyond their water solubility (>1 g/100 mL) where precipitation is not expected. The conductivity of the 1000 and 500 X solution was measured following 1 h dissolution in MilliQ water or the Hydra medium and revealed no loss of ion activity.

2.2. Aquatic Toxicity Assessment with Hydra vulgaris

Hydra vulgaris were reared in 100 mL crystallization bowls with the Hydra medium: 1 mM CaCl2 containing 0.4 mM TES buffer pH 7.5 without EDTA (Blaise et al., 2018). They were fed daily with live Artemia salina brine shrimps as previously described. They were allowed to grow and reproduce under 16h/8h light/dark cycles at 20-22oC with a doubling time of 4.5 days. Hydra were not fed prior the initiation of the exposure experiments. Adult hydras (3) were placed in each of three wells in 24-well microplates in 4 mL of the Hydra medium. They were exposed to increasing concentrations of the REE urban mixture at 0.5, 1, 10, 25, 50 and 100 X concentration range for 96 h at 20oC. Two other microplates were prepared for gene expression analysis, This represent a total REEs range of 0.137 to 13.7 µg/L. The lethal and sublethal toxicity were determined and expressed as the lethal concentration of 50 % of the hydra (LC50) and the sublethal effect concentration of 50 % of the hydra (EC50) using the Spearman-Karber method (Finney, 1964). Given the exposure period encompasses the doubling time, the exposure period is considered chronic. The morphological changes for lethality (tulip and disintegrated body) and sublethality (budding and shortening of tentacles) were determined using at 6X stereomicroscope. Morphological unaffected hydras were collected for gene expression analysis at some of the exposure concentrations. Hydra were harvested with a 1 mL pipet and immediately transferred in RNA later solution (Millipore Sigma, ON, Canada) and stored at -20oC for gene expression analysis.

2.3. Gene Expression Analysis

Preliminary experiments revealed that RNA extraction from pooled 2 wells (N=6 total hydra per treatment) were sufficient for RNA purity analysis. Hence gene expression analysis was performed with 3 groups of 2 wells. Total RNA was extracted from each pooled hydra using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Qc, Canada). RNA concentration and purity were assessed with the NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, ON, Canada) and RNA integrity was confirmed using the TapeStation 4150 system (Agilent) with the Agilent RNA ScreenTape Assay (cat # 5067-5576, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, USA). Reverse transcription was performed with the QuantiTect® Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen), ensuring the complete removal of genomic DNA. The resulting cDNA samples were stored at -80 °C until quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis.

For each target genes (

Table 1), the selected forward and reverse primers were validated with cDNA concentration at 10 ng followed by 6-8 serial dilutions (10, 8, 6 ng etc) with an amplification performance between 95% and 115%. This also permitted to establish the limit of quantification for each gene targets. Each reaction was run in duplicate and consisted of 5 µL cDNA, 6.5 µL of 2× SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad), 300 nM of each primer, and DEPC-treated water (Ambion) up to a total volume of 13 µL. Cycling parameters were as follows: 95 °C for 30 s, then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 10 s for HPRT (reference gene), RPLPO (reference gene), Efα (reference gene), DDC1, SRF, and OGG; 95 °C for 30 s, then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 56 °C for 10 s for CAT and MANF; and 95 °C for 30 s, then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 56 °C for 30 s for MAPC3. All qPCR analyses were conducted using SsoFast™ EvaGreen

® Supermix (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, ON, Canada) and the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Amplification specificity was verified by denaturation (melting curve) temperature analysis at the end of the amplification cycles. A no-template control (NTC) was included on each plate. Data analysis was performed using CFX Maestro (Bio-Rad).

2.4. Data Analysis

The exposure experiments were repeated twice with n=3 replicates for each treatments. Toxicogenomic data was expressed as effect threshold concentration (X or ug/L total REE loadings) and defined as follows: Effect threshold = (no effect concentration x lowest significant effect concentration)1/2. The gene expression data were analyzed using a rank-based analysis of variance followed by the Conover-Iman test for differences from the controls. Relationships between toxicity and the gene expression data were determined using the Spearman rank procedure. The gene expression data were also analyzed by hierarchical tree to determine similarity of effects between the elements using the square Pearson-moment correlation (1-R) as the metric distance between the observed gene expression changes. Significance was set at p < 0.05. All the statistical analyses were conducted using SYSTAT (version 13, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

The physical-chemical properties of the REEs in the urban mixture are provided (

Table 2). The mixture was composed with the following proportion of REEs: Gd (80%)<Ce (7%)<Nd (6%)<Yb (4%)<Dy (3%) with total REEs mass concentration of 0.137 µg/L for the 1 X concentration. Both the levels and relative proportion of REEs in this mixture were calculated based the dissolved REE levels from 6 different municipal effluents in Canada (Turcotte et al., 2022). The atomic mass range was relatively narrow between 140.12-173.04 g/mol with an ionic radius range between 91-107 pm. Electronegativity generally increased with the atomic mass and somewhat with the ionic radius. These metrics were relatively far from the major trivalent bioelement in organisms Fe (atomic weight 55.85, ionic radius 79 pm and electronegativity of 1.83). The lethal and sublethal toxicity data for each individual REE in Hydra were reported also in

Table 2. In general, lighter REE with higher ionic radius were more toxic to hydra corroborating previous findings for REEs LC50 and EC50 values in hydra (Hanana et al., 2022). The lethal (LC50) and sublethal (EC50) concentrations ranged from 310-690 µg/L and 50-270 µg/l respectively based on morphological changes. This suggests that the 100 X urban mixture for Gd (11.7 µg/L) was 47 times less concentrated than the LC50 for Gd and 9 times lower than the EC50 for Gd in Hydra. The highest reported levels of dissolved Gd in municipal wastewaters reached 229 ng/L in the dissolved fraction for a secondary activated sludge effluent in the Saint-Lawrence River area (Turcotte et al., 2022). In another study, dissolved Gd levels reached from 286 ng/L from an advanced wastewater treatment plant in the American east coast (Virginia, USA; Smith et al., 2021). These values could reach upper lower µg/L (700 µg/L) in highly populated areas (37 million inhabitants) supporting many hospitals since Gd used as a contrast agent in MRI represent the main source of dissolved Gd in effluents (Inoue et al., 2022).

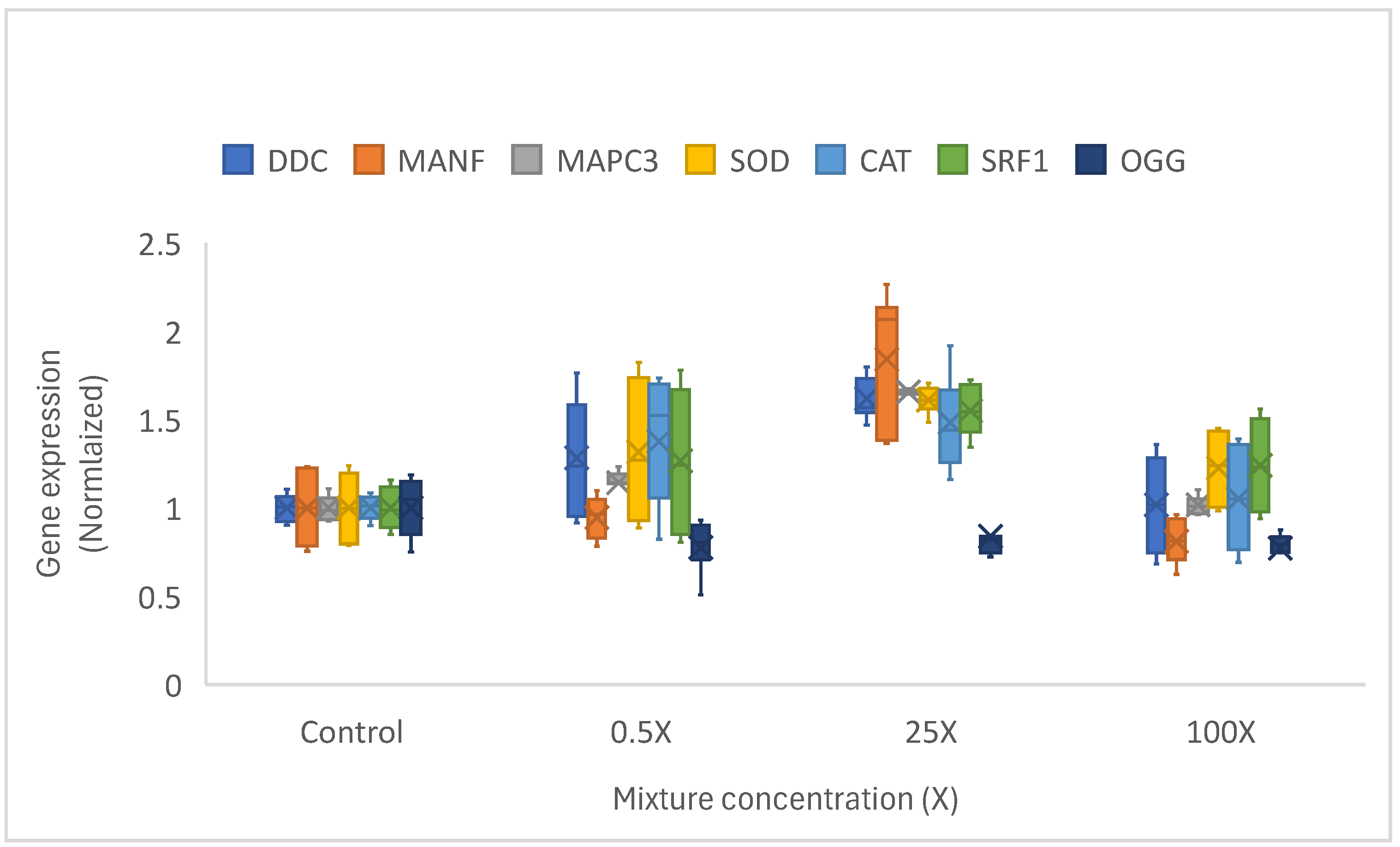

The sublethal effects of the representative mixture were investigated in Hydra attenuata (

Table 3). The urban mixture did not lead to sublethal morphological changes in hydra up to an equivalent of 13.7 µg/L of total REEs where Gd representing 80% by mass of the REE. However, significant changes were observed in the mixture for all the gene targets examined (

Figure 1). Most genes were upregulated at mixture concentrations between 0.5 X (0.0685 µg/L total REE) and 25 X (3.25 µg/L total REE) except for the downregulated expression of OGG gene involved in the repair of oxidatively-damage DNA. Interestingly, the responses were dampened at the highest concentration tested of 100 X (13.7 µg/L total REE) suggesting pre-morphological toxicity given that the Gd (11.7 µg/L) in the urban mixture was approaching the EC50 range of Gd (first appearance of tentacle budding at 40 µg/L for Gd). This suggests that municipal effluents release Gd at concentrations that could induce gene expression in hydra especially for those involved in oxidative stress (CAT, OGG) and protein salvage pathways (MAPC3), which precedes sublethal morphological changes (

Table 3). However, no apparent change in morphology was observed at concentrations reaching 13.7 µg/L (Gd representing 80% of the REEs in the urban mixture) after 96 h exposure period. Future research should examine more long-term exposure periods (>96 h) in hydra for REEs. In zebra mussels exposed to either GdCl

3 or the medical organic form (Omniscan) Gd used for medical imaging, CAT and SOD gene expression were decreased at concentrations (10-50 µg/L) followed by significant increases at much higher concentration (1250 µg/L) (Houda et al., 2017). Decreased OGG gene expression suggests an accumulation of DNA damage (8-oxoguanosine adducts), which could lead to cytogenetic damage. Indeed, Gd was reported to increase the frequency of micronuclei in human lymphocytes (Yongxing et al., 2000; Cho et al. 2014) and in the plant

Arabidopsis thaliana at environmentally relevant concentrations in soils (Liu et al., 2021).

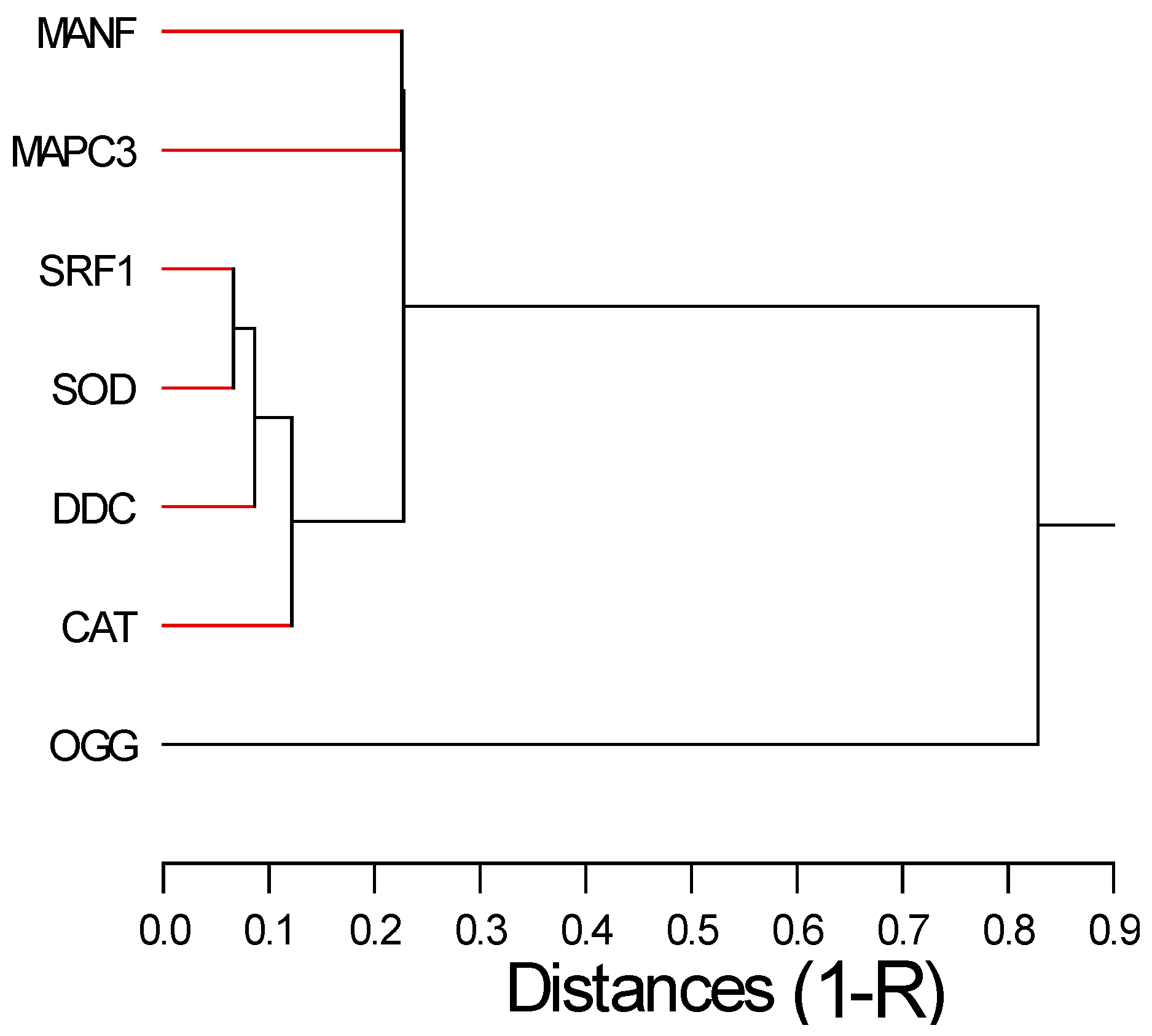

Correlation analysis revealed that SRF-1 gene expression was clustered (i.e., strongly correlated) with oxidative stress (SOD and CAT) and DDC biomarkers (

Figure 2). This suggests that the gene involved in regeneration and growth involved dopamine-dependent neuroactivity and oxidative stress. DDC activity increases the conversion of L-DOPA to dopamine during the wake stage, feeding activity and tentacles regeneration (Omond et al., 2022; Markova et al., 2008). This is consistent with the significant correlation between DDC and SRF1 gene expression involved in regeneration and cell differentiation. This suggests that genes involved in oxygen radical elimination (CAT and SOD) are coupled to hydra neural activity (DDC) and cell regeneration. In a previous study, hydra was exposed to a representative mixture of REE from lakes contaminated with mine tailings led to decreased head (tentacles) regeneration and reproduction rates (Hanana et al., 2022). The mixture consisted of the 5 most-abundant REEs (La, Ce, Pr, Nd and Sm), 2 of which are also found in the urban mixture at a total REE concentration of 580 µg/L, which is 42 times more concentrated than the urban effluent mixture. Hence, mining mixtures present an higher risk in hydra compared to the urban mixture. This suggests that increased activity in DDC, SRF1, SOD and CAT observed at low concentrations followed by a dampening at higher concentrations precedes sublethal morphological changes. Nevertheless, the threshold effect concentration for lethal and sublethal toxicity were between 0.3-0.7 µg/L of the total REE loading, which is in the same order of magnitude that with the present study (<0.0685-0.137 µg/L total REEs loading) for gene expression changes. Hydra doubling time was significantly reduced at 0.2 X corresponding to 116 µg/L total REE loadings in the mining lake mixture. Nevertheless, the hydra could be used as a sensitive model organism for the assessment of aquatic ecotoxicological risks of REE of not only mining contaminated lakes but in urban mixtures as well. More research on early biochemical and/or gene expression levels should improve our understanding of the long-term effects of REEs mixtures.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, hydra exposed to increasing concentrations of a realistic urban mixture did not lead to morphological changes at concentrations reaching 13.7 total REEs loadings. However, changes at the gene expression level for protein salvaging and oxidative stress occurred at concentrations below those found in municipal effluents. Genes involved in neural activity, regeneration and oxidative stress were activity at concentrations 3.5 X those found in the effluents but still environmentally realistic in respect to larger urban effluents from more populated cities.

Supplementary Materials

Figure 1S.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AuClair J, Gagné F; methodology, Auclair J, André C, Roubeau-Dumont E.; software, C. André, validation, André C, Roubeau-Dumont E.; formal analysis, André C, Roubeau-Dumont E. X.X.; investigation, J. Auclair, F.Gagné; resources, F. Gagné; data curation, André C, Roubeau-Dumont E, writing—original draft preparation, Gagné F. writing—review and editing, André C, Roubeau-Dumont E, Auclair J, Gagné F; visualization, Gagné F; supervision, Gagné F, C André; project administration, Gagné F; funding acquisition, Gagné F.

Funding

this work was funded by the Chemical management plan of Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be available upon request to the authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the assistance of Maxime Gauthier for hydra preparation for genomic analyses.

References

- Beaubien C 2015. Toxicité de deux lanthanides (La, Ce) sur l′algue verte Chlorella fusca, Université du Québec, Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique Centre Eau Terre Environnement.

- Blaise C, Kusui T. Acute toxicity assessment of industrial effluents with a microplate-based Hydra attenuata assay. Environ. Toxicol. Water Qual 1997, 12, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaise C, Gagné F, Harwood M, Quinn B, Hanana H. Ecotoxicity responses of the freshwater cnidarian Hydra attenuata to 11 rare earth elements. Ecotoxicol and Environ Saf 2018, 163, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brünjes R, Hofmann T. Anthropogenic gadolinium in freshwater and drinking water systems. Water Res 2020, 182, 115966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho S, Lee Y, Lee S, Choi YJ, Chung HW. Enhanced cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of gadolinium following ELF-EMF irradiation in human lymphocytes. Drug Chem Toxicol 2014, 37, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubé M, Auclair J, Hanana H, Turcotte P, Gagnon C and F., Gagné. Gene expression changes and toxicity of selected rare earth elements in rainbow trout juveniles. Comparative Biochem Physiol 2019, 223 C, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Duchna M, Cieślik I 2022. Rare earth elements in new advanced engineering applications. Rare earth elements - emerging advances, technology utilization, and resource procurement. [CrossRef]

- Fatima, J., Ara, G., Afzal, M., & Siddique, Y. H. (2024). Hydra as a research model. Toxin Reviews, 43(1), 157–177. [CrossRef]

- Finney DJ 1964. Statistical method in biological assay. Hafner Publishing Company, 668 pages.

- Ghaskadbi, S., 2020. Hydra: a powerful biological model. Resonance 25, 1197–1213. [CrossRef]

- Gwenzi W, Mangori, L., Danha, C., Chaukura, N., Dunjana, N., Sanganyado, E., 2018. Sources, behaviour, and environmental and human health risks of high-technology rare earth elements as emerging contaminants. Sci Total Environ 636, 299–313. [CrossRef]

- Hanana H, Turcotte P, André C, Gagnon C, Gagné F. Comparative study of the effects of gadolinium chloride and gadolinium e based magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent on freshwater mussel, Dreissena polymorpha. Chemosphere 2017, 181, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanana H, Gagné F, Trottier S, Bouchard P, Farley G, Auclair J, Gagnon C 2022. Assessment of the toxicity of a mixture of five rare earth elements found in aquatic ecosystems in Hydra vulgaris. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 241, 113793. [CrossRef]

- Inoue K, Fukushi M, Furukawa A, Sahoo SK, Veerasamy N, Ichimura K, Kasahara S, Ichihara M, Tsukada M, Torii M, Mizoguchi M, Taguchi Y, Nakazawa S. 2020 Impact on gadolinium anomaly in river waters in Tokyo related to the increased number of MRI devices in use. Mar Pollut Bull 154, 111148. [CrossRef]

- Inoue K, Fukushi M, Sahoo SK, Veerasamy M, Furukawa A, Soyama S, Sakata A, Isoda R, Taguchi Y, Hosokawa S, Sagara H, Natarajan T. Baseline Measurements and future projections of Gd-based contrast agents for MRI exams in wastewater treatment plants in the Tokyo metropolitan area. Marine Poll Bull 2022, 174, 113259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loomis WF 1954. Environmental factors controlling growth in Hydra. J Exp Zool 126, 223-234. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Guo C, Tai P, Sun L, Chen Z 2021. The exposure of gadolinium at environmental relevant levels induced genotoxic effects in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 215, 112138. [CrossRef]

- McKinley K, Gagné F, Quinn B 2019. The toxicity of potentially toxic elements (Cu, Fe, Mn, Zn and Ni) to the cnidarian Hydra attenuata at environmentally relevant concentrations. Sci Total Environ 665, 848–854. [CrossRef]

- MacMillan GA, Chetelat J, Heath JP, Mickpegak R, Amyot M 2017. Rare earth elements in freshwater, marine, and terrestrial ecosystems in the eastern Canadian Arctic. Environ Sci Process Impacts 19, 1336–1345. [CrossRef]

- Markova LN, Ostroumova TV, Akimov MG, Bezuglov VV 2008. [N-arachidonoyl dopamine is a possible factor of the rate of tentacle formation in freshwater hydra]. Ontogenez 39, 66-71. [CrossRef]

- Omond SET, Hale MW, Lesku JA 2022. Neurotransmitters of sleep and wakefulness in flatworms. Sleep 45, zsac053. [CrossRef]

- Smith JP, Boyd TJ, Cragan J, Ward MC 2021. Dissolved rubidium to strontium ratio as a conservative tracer for wastewater effluent-sourced contaminant inputs near a major urban wastewater treatment plant. Water Research 205, 117691. [CrossRef]

- Smith Stegen K (2015) Heavy rare earths, permanent magnets, and renewable energies: an imminent crisis. Energy Policy 2015, 79, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Turcotte P, Smyth SA, Gagné F, Gagnon C 2022. Lanthanides Release and Partitioning in Municipal Wastewater Effluents. Toxics 10, 254. [CrossRef]

- Vimalkumar K, Sangeetha S, Felix L, Kay P, Pugazhendhi A 2022. A systematic review on toxicity assessment of persistent emerging pollutants (EPs) and associated microplastics (MPs) in the environment using the Hydra animal model. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 256: 109320. [CrossRef]

- Yongxing W, Xiaorong W, Zichun H 2000. Genotoxicity of lanthanum (III) and gadolinium (III) in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 64, 611-616. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).