Submitted:

30 November 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

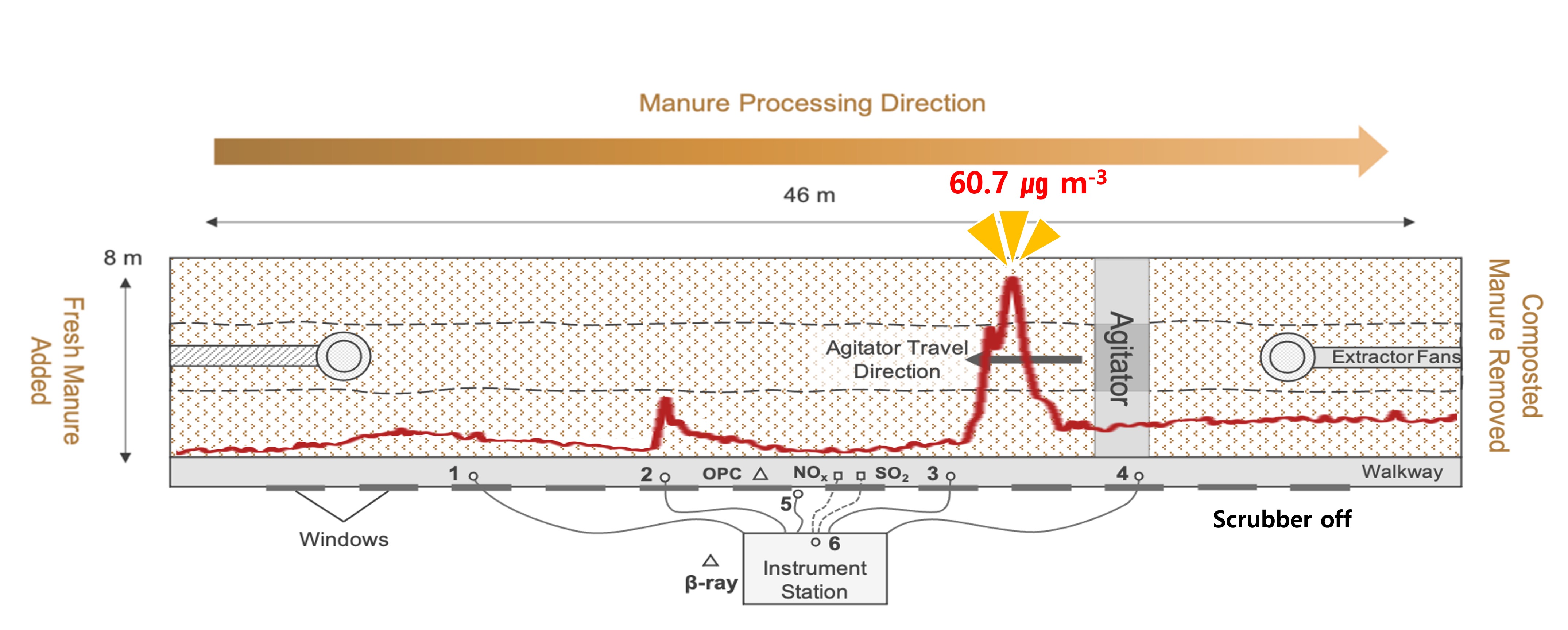

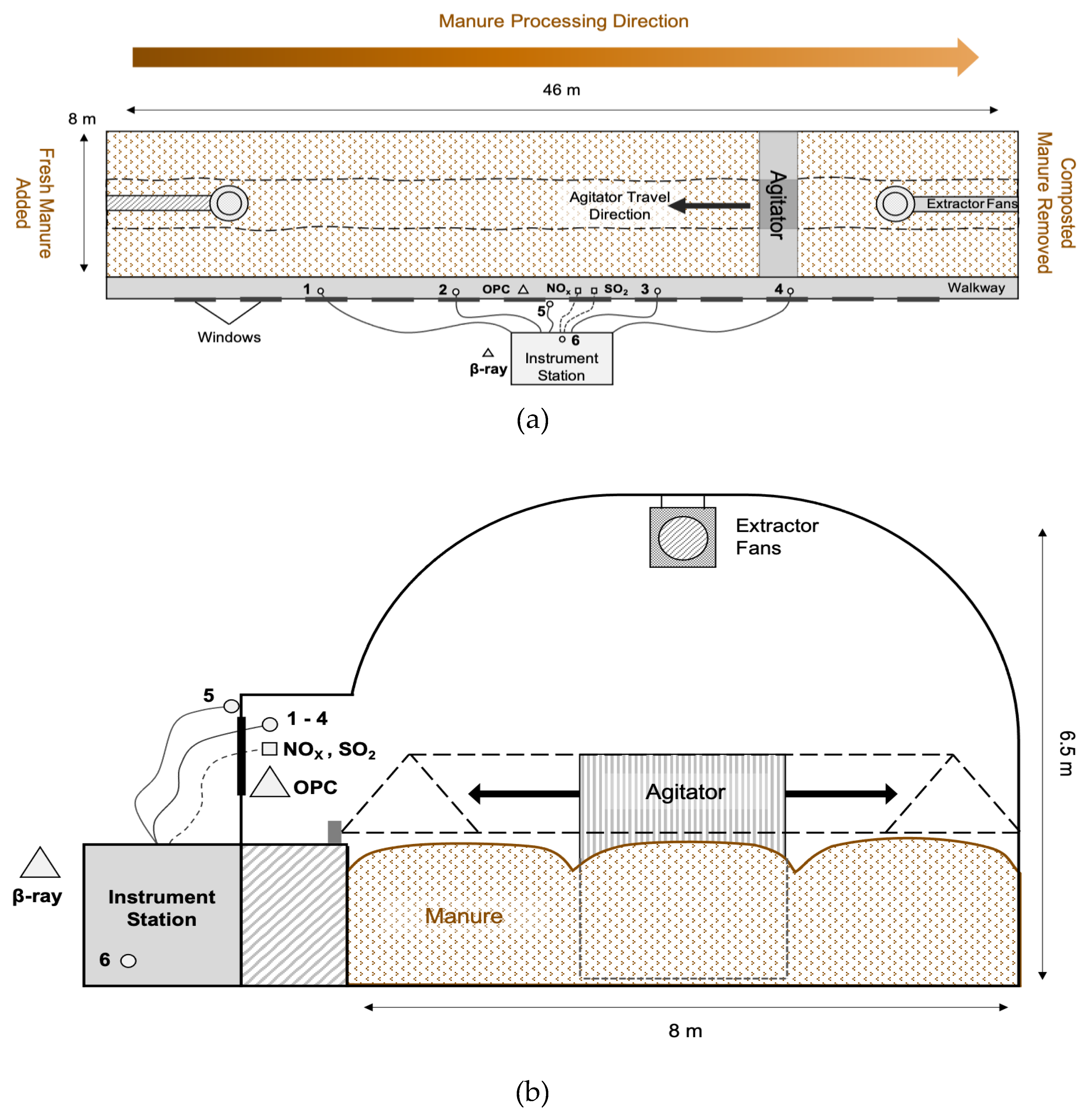

2.1. Monitoring Site

2.2. Monitoring System

2.2.1. Precursor gas measurement

2.2.2. Particulate Matter measurement

2.2.3. Environmental Variables

2.3. Ammonia Emission Flux Calculations

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

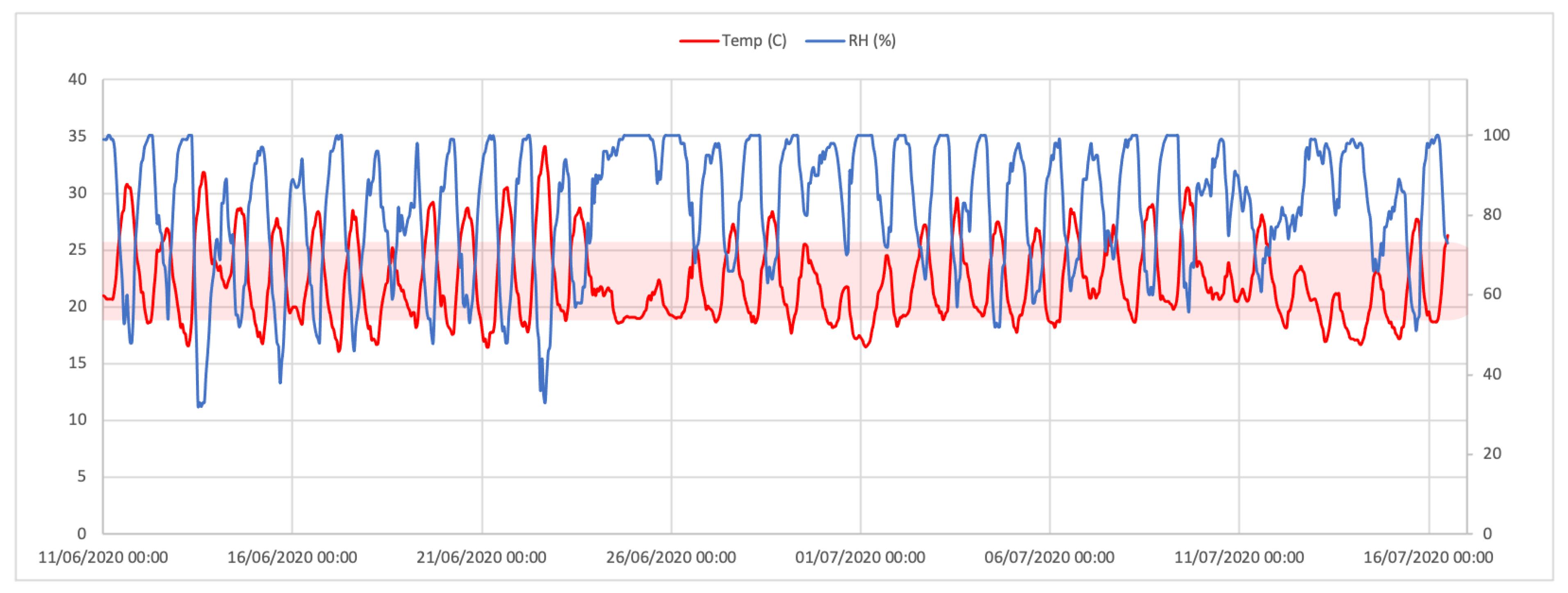

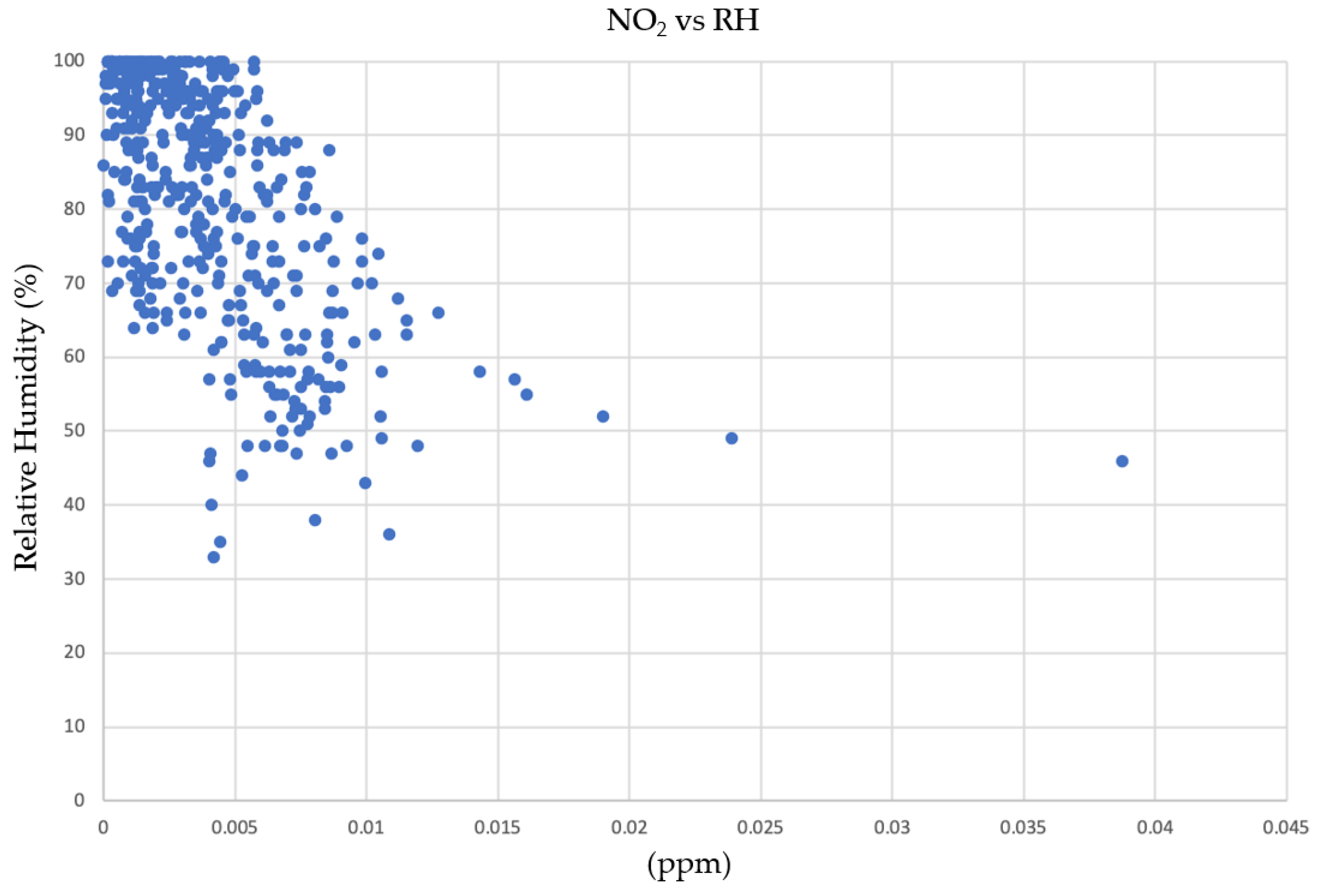

3.1. Environmental Variables: Temperature and Relative Humidity

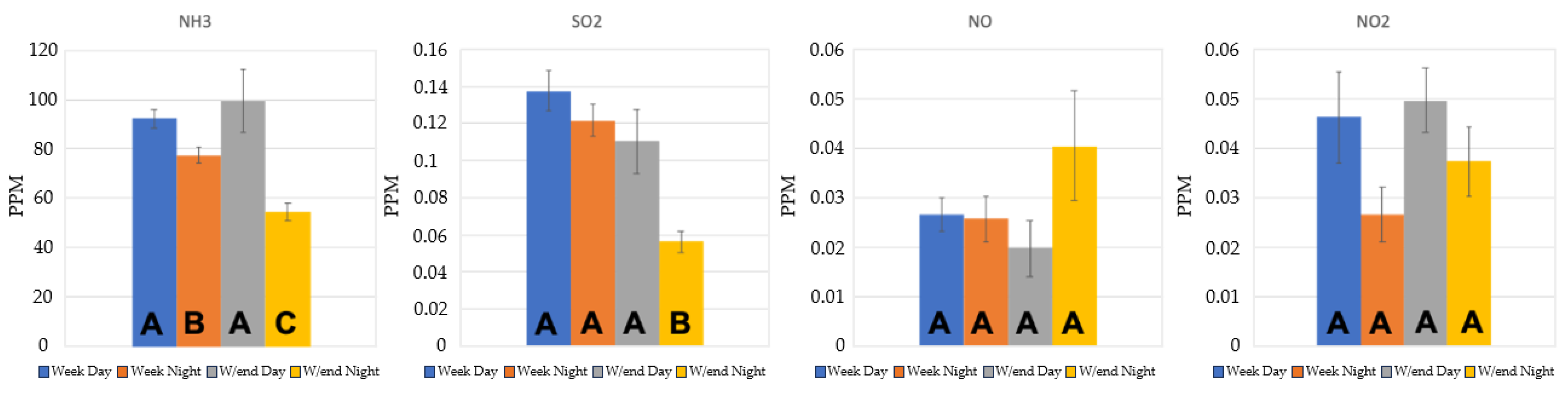

3.2. Gas Concentrations

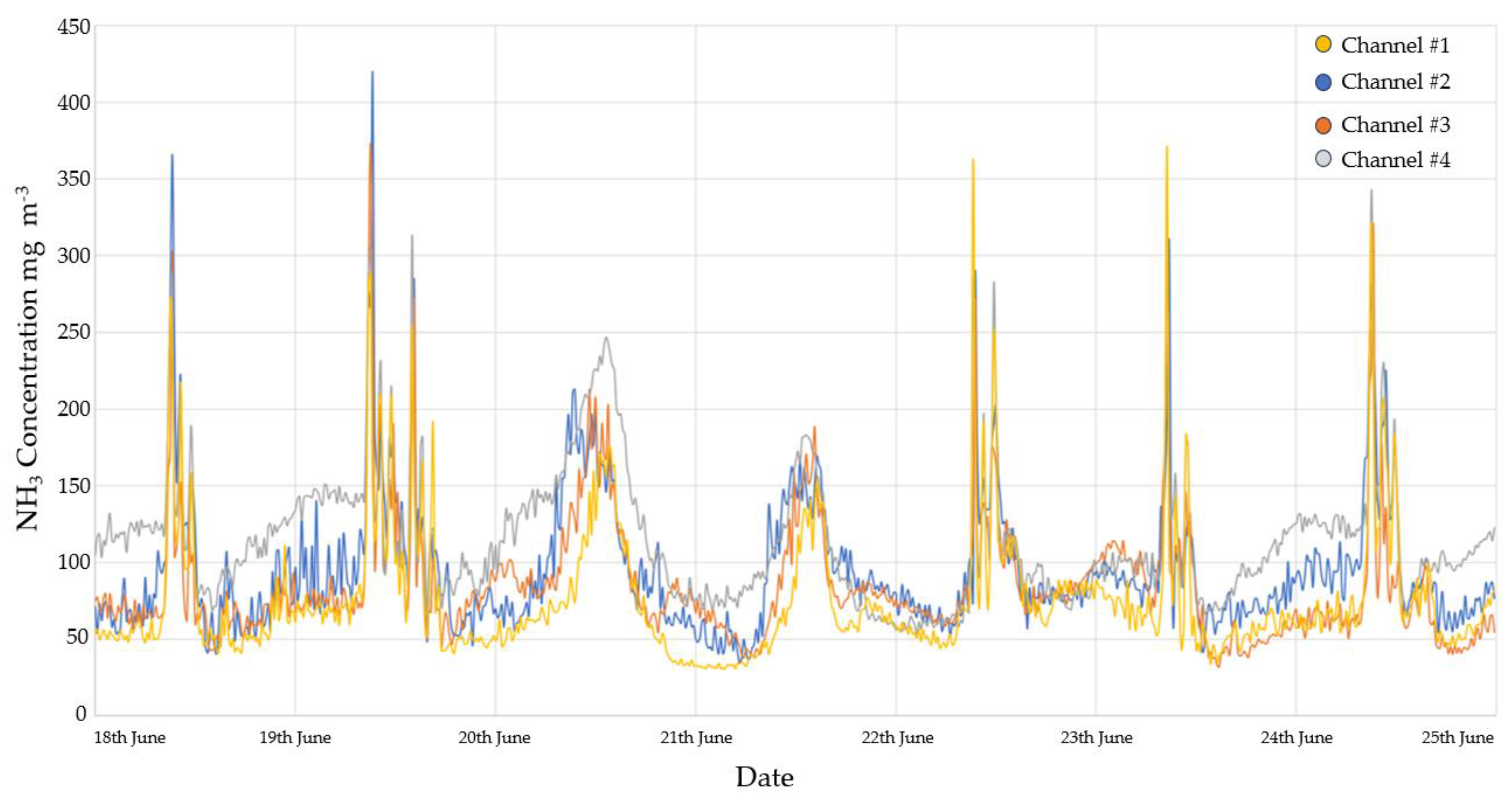

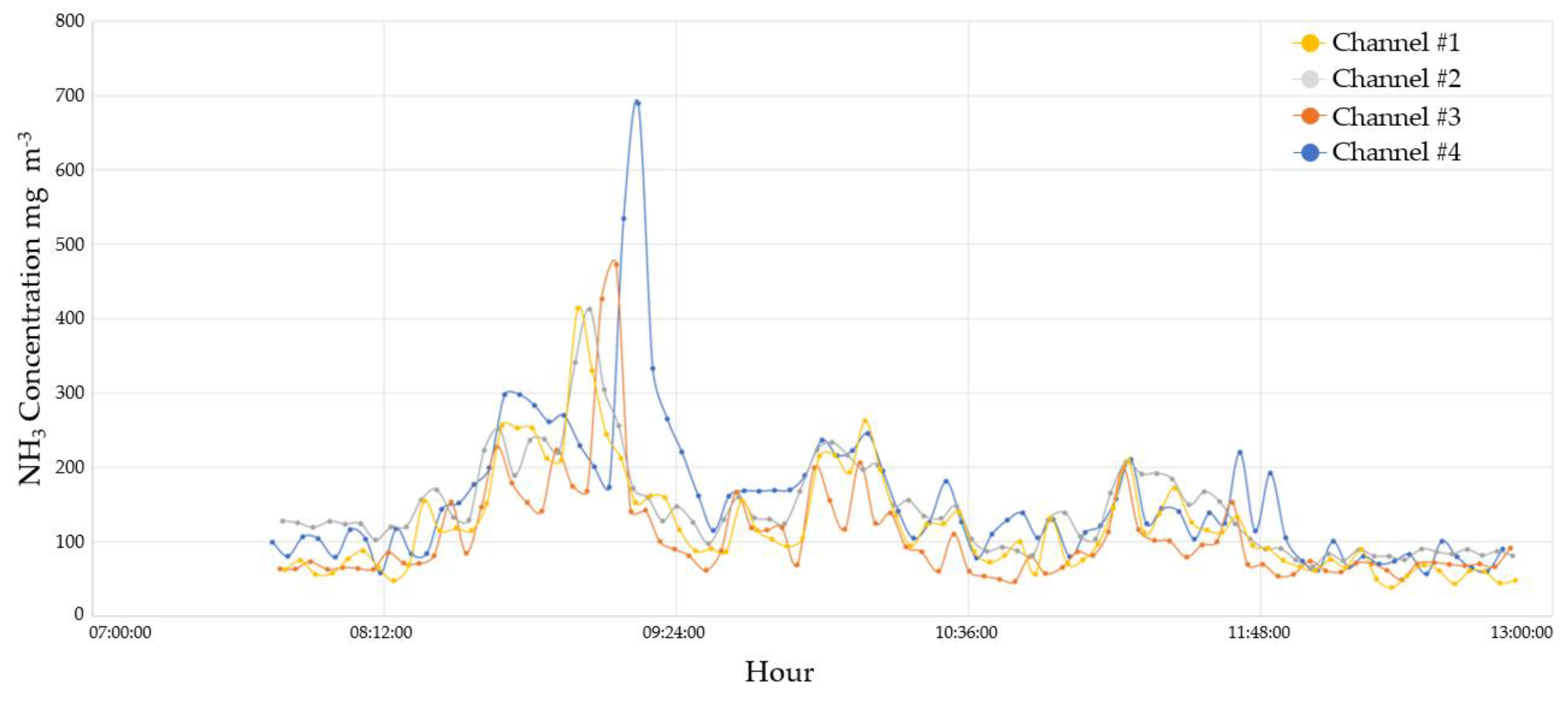

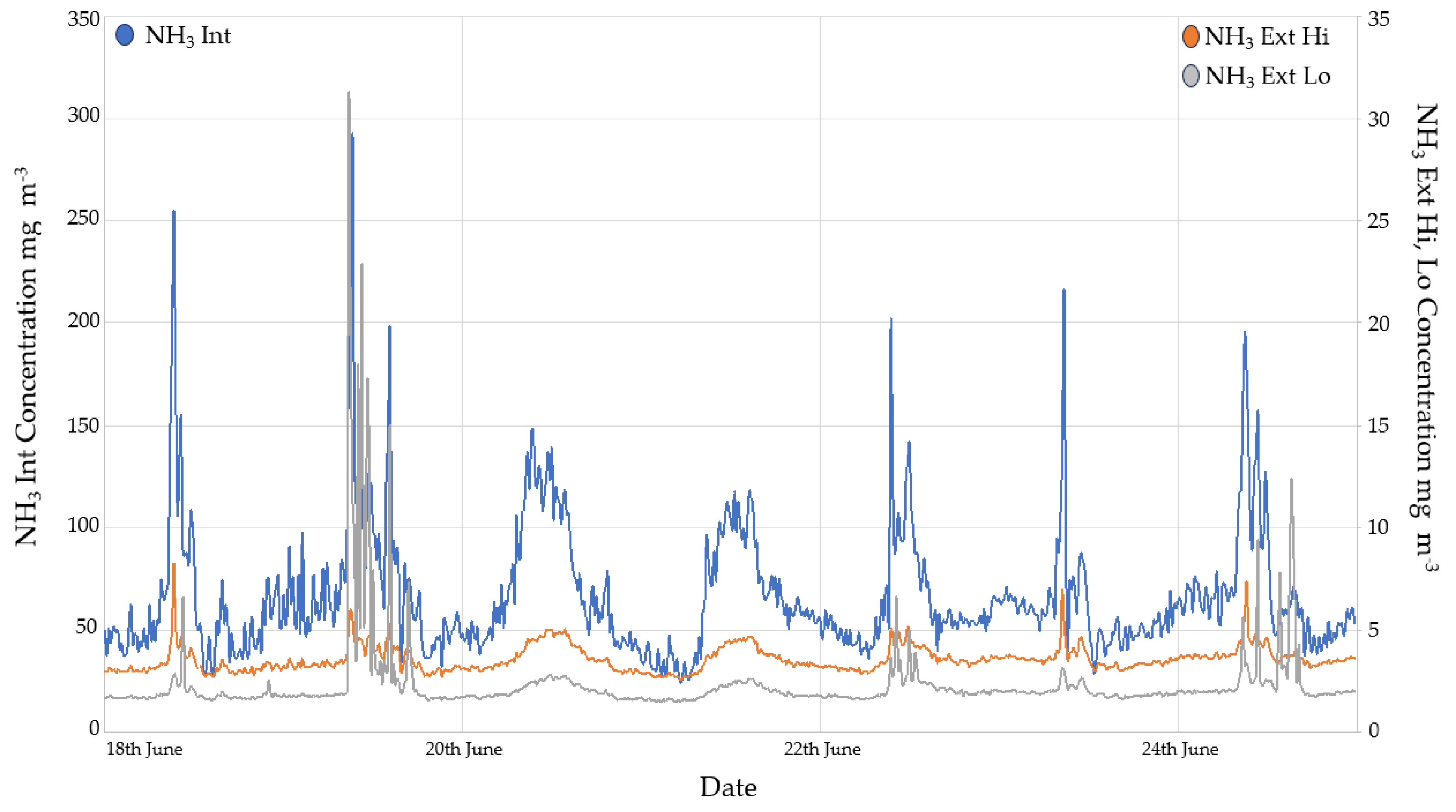

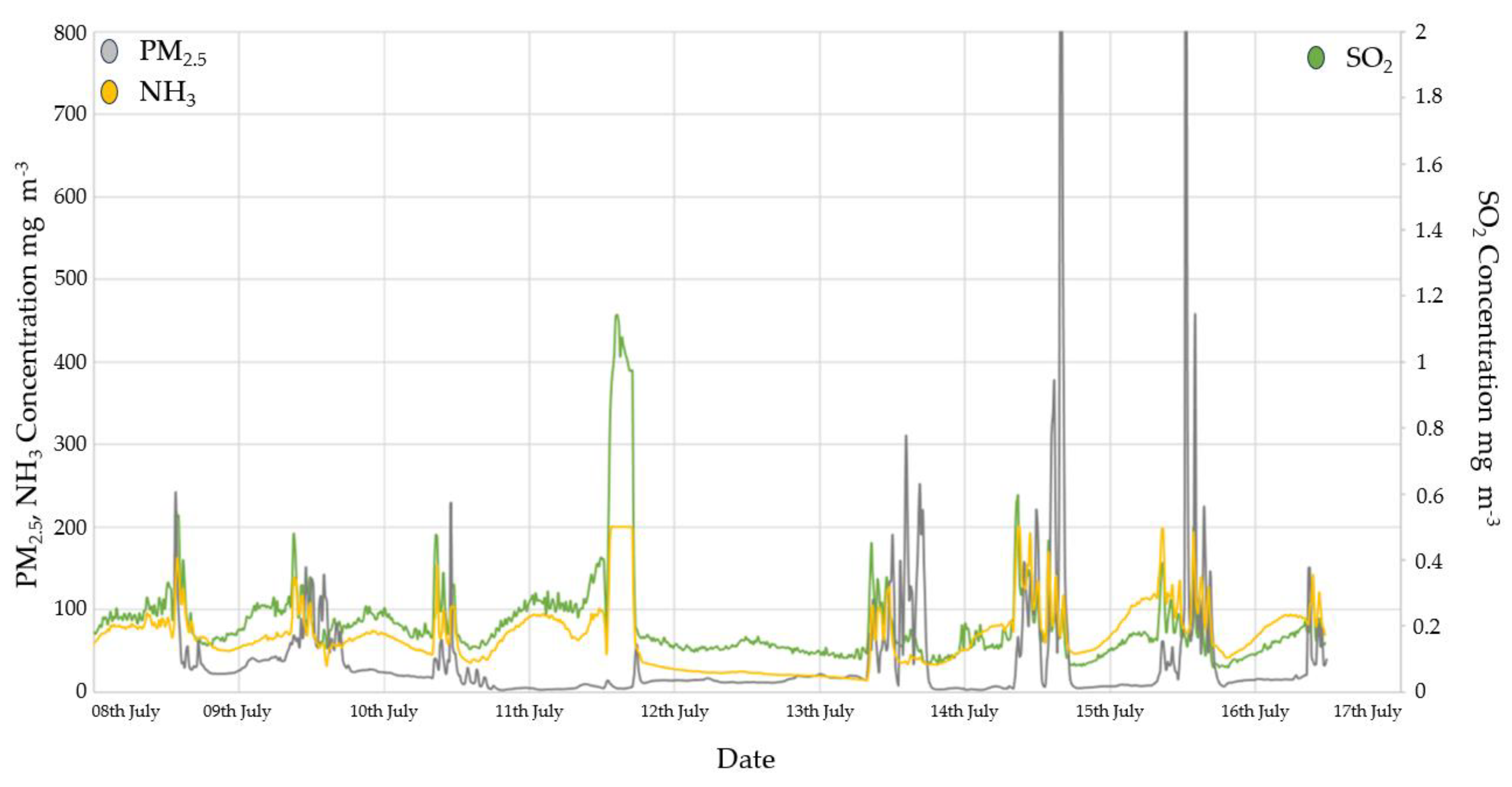

3.2.1. Ammonia monitoring results

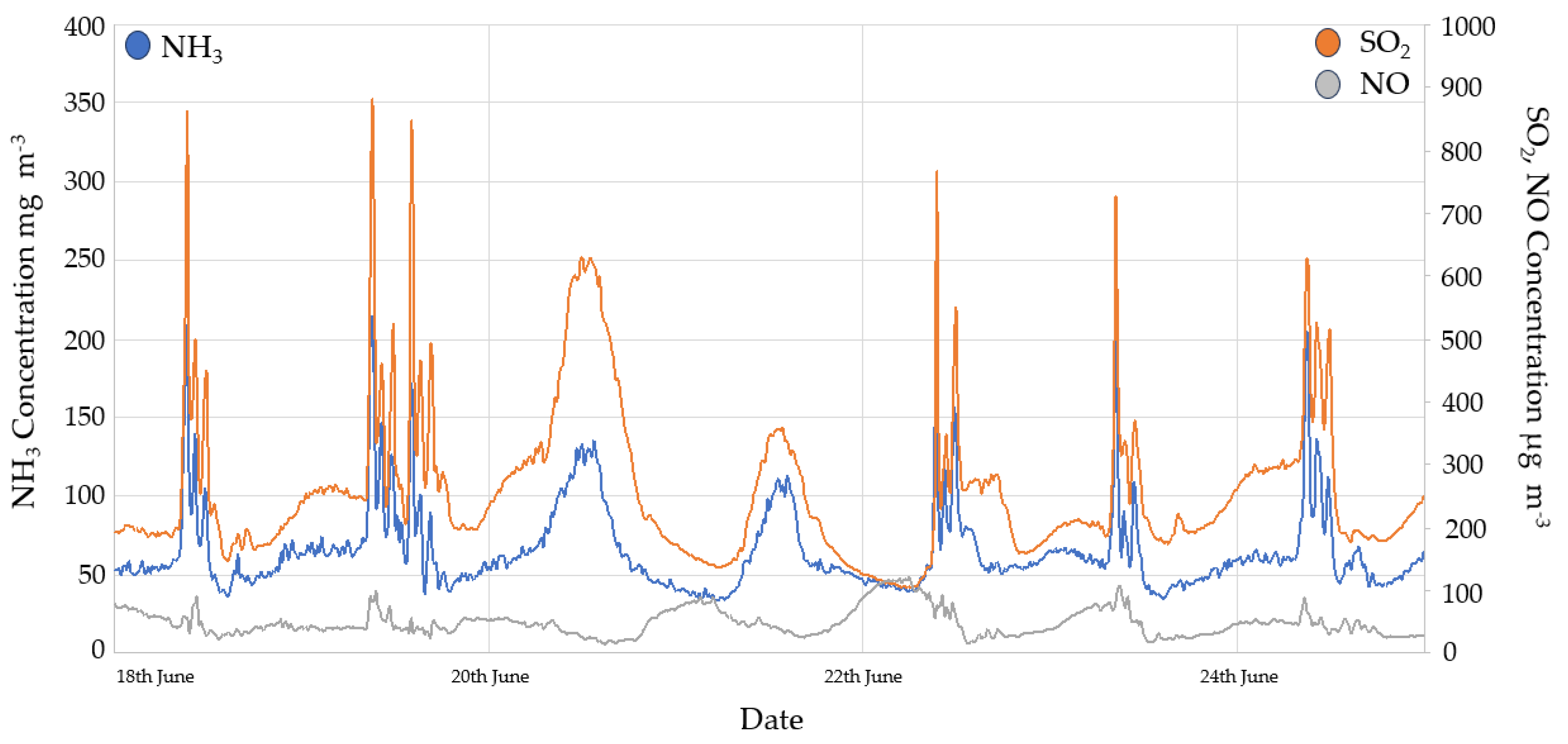

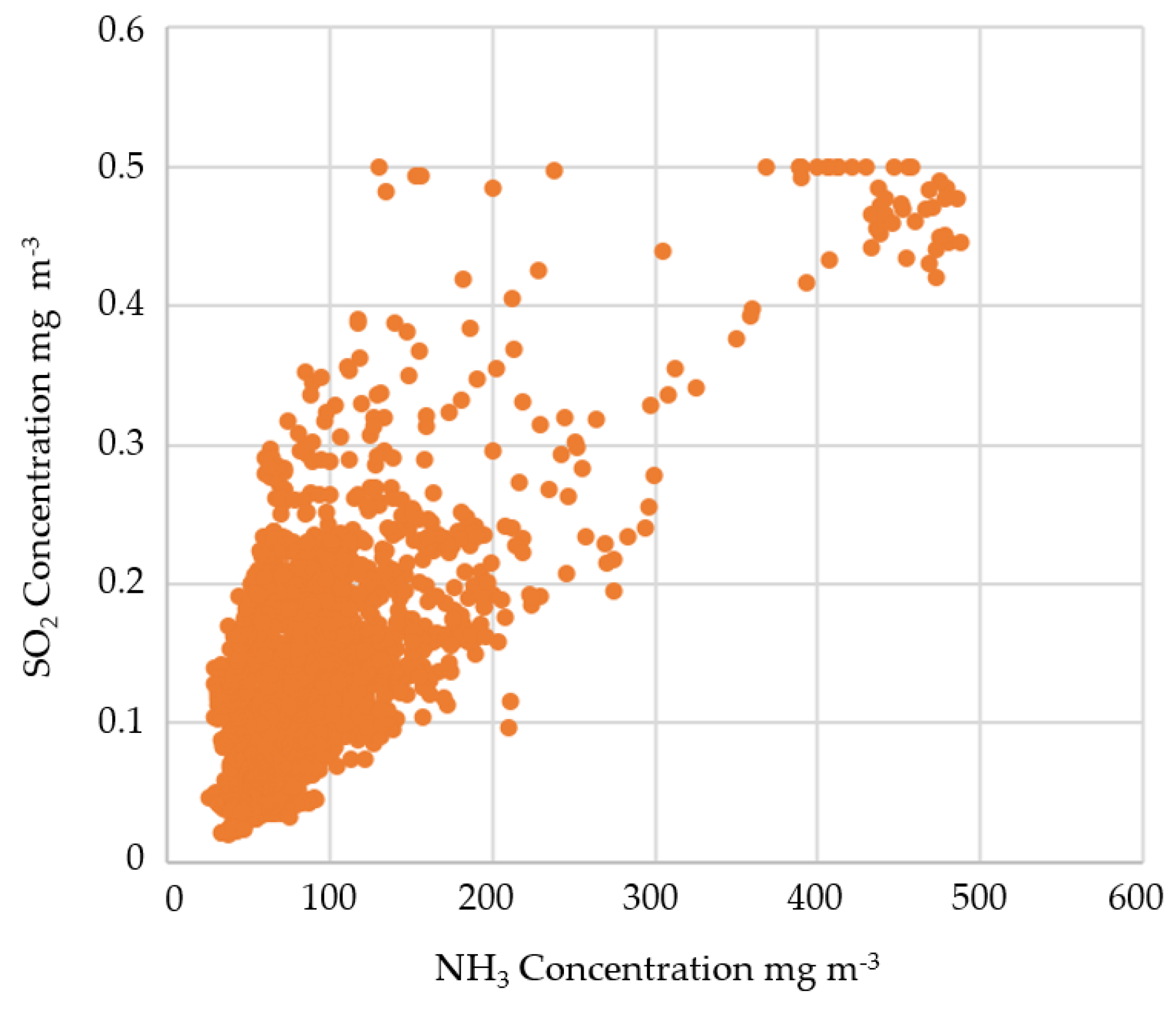

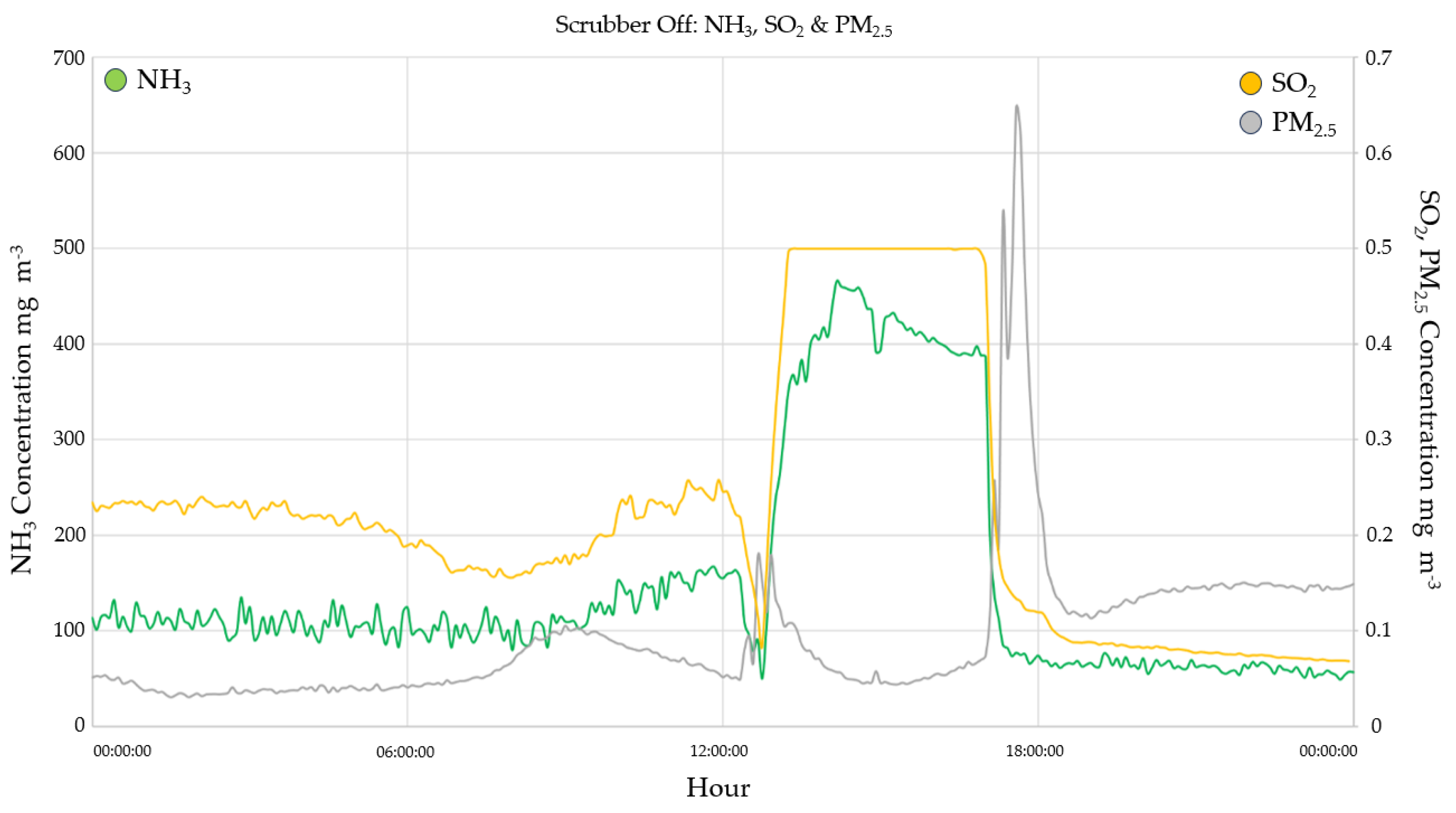

3.2.2. SO2

3.2.3. NOx

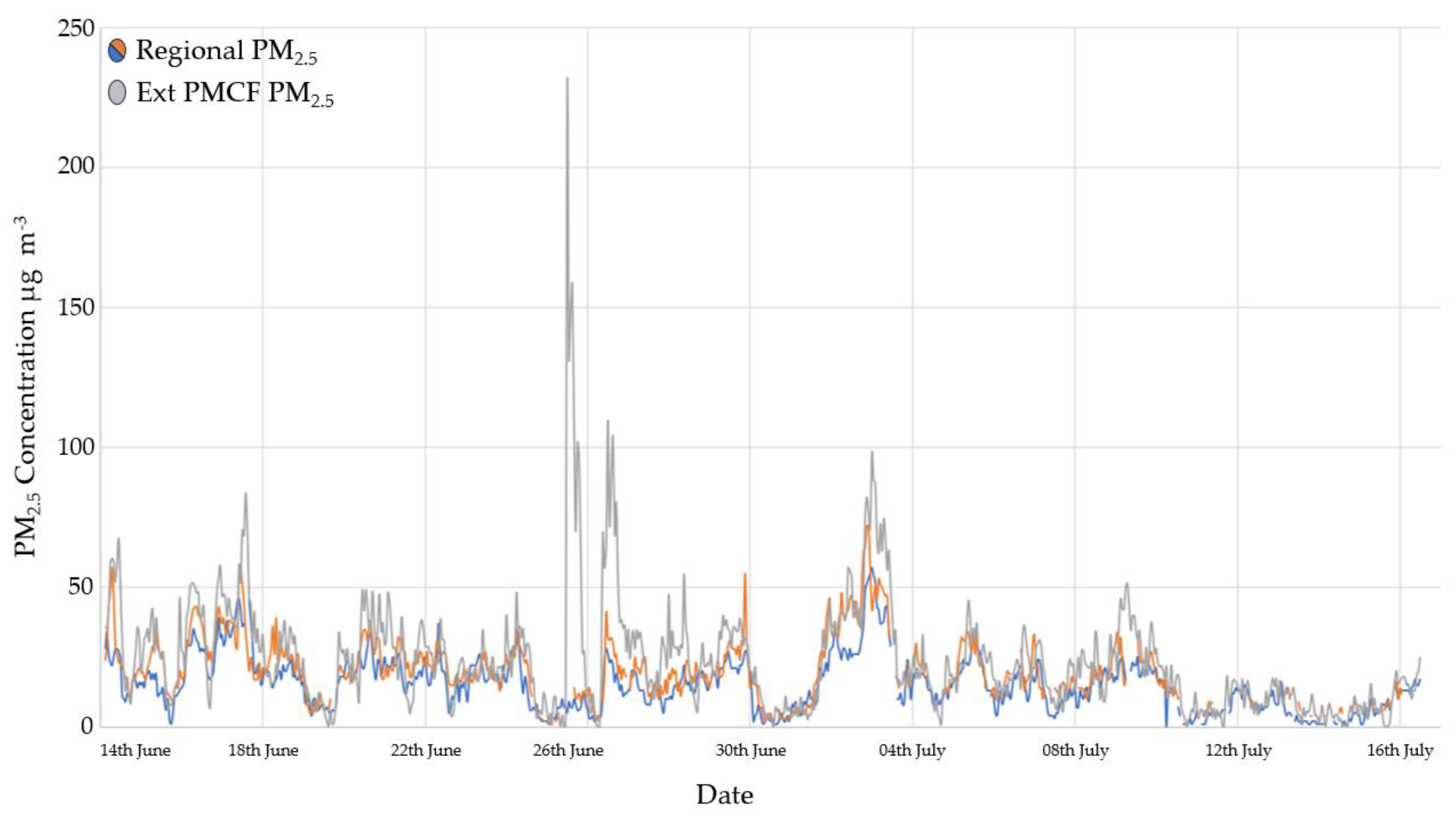

3.3. Particulate Matter Concentrations

3.4. Ammonia Emission Rate

4. Conclusions

References

- Korean National Air Pollutants Emission Service. Gaseous Emissions by Sector. 2017. (Accessed on 3 February 2021).

- Streets, D.G.; Bond, T.C.; Carmichael, G.R.; Fernandes, S.D.; Fu Q.; He, D.; Klimont, Z.; Nelson, S.M.; Tsai, N.Y.; Wang, M.Q. An inventory of gaseous and primary aerosol emissions in Asia in the year 2000. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003, 108. [CrossRef]

- Velthof, G.L.; van Bruggen, C.; Groenestein, C.M.; de Haan, B.J.; Hoogeveen, M.W.; Huijsmans, J. A model for inventory of ammonia emissions from agriculture in the NetherlandsAtmos. Environ. 2012, 46, 248–255.

- Wang, S., Nan, J.; Shi, C.; Fu, Q.; Gao, S.; Wang, D.; Cui, H.; Saiz-Lopez, A.; Zhou, B. Atmospheric ammonia and its impacts on regional air quality over the megacity of Shanghai, China. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Hadlocon, L.J.S.; Manuzon, R.B.; Darr, M.J.; Keener, H.M.; Heber, A.J.; Ni, J. Ammonia concentrations and emission rates at a commercial poultry manure composting facility. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 150, 69–78. [CrossRef]

- Sommer, S.G.; Webb, J.; Hutchings, N.D. New emission factors for calculation of ammonia volatilization from European livestock manure management systems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Hristov, A.N. Technical note: Contribution of ammonia emitted from livestock to atmospheric fine particulate matter (PM2. 5) in the United States. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 3130–3136. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Bai, Z.; Winiwarter, W.; Ledgard, S.; Luo, J.; Liu, J.; Guo, Y.; Ma, L. Reducing ammonia emissions from dairy cattle production via cost-effective manure management techniques in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 11840–11848. [CrossRef]

- Sutton, M.A.; Oenema, O.; Erisman, J.W.; Leip, A.; van Grinsven, H.; Winiwarter, W. Too much of a good thing. Nature 2011, 472, 159–161.

- Hristov, A.H.; Hanigan, M.; Cole, A.; Todd, R.; Mcallister, T.A.; Ndegwa, P.M.; Rotz, A. Review: ammonia emissions from dairy farms and beef feedlots. Can. J. Ani. Sci. 2011, 91, 1–35. [CrossRef]

- OECD. Meat consumption (indicator). 2021. (Accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Won, S.; Yoon, Y.; Hamid, M.M.A.; Reza, A.; Shim, S.; Kim, S.; Ra, C.; Novianty, E.; Park, K. Estimation of greenhouse gas emission from Hanwoo (Korean native cattle) manure management systems. Atmosphere (Basel) 2020, 11, 845. [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, K.; Jeon, B.; Lee, M.; Kim, Y.; Kim, B.; Cho, S.; Hwang, O.; Bhattacharya, S.S. Odor characterization from barns and slurry treatment facilities at a commercial swine facility in South Korea. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 119, 339–347. [CrossRef]

- Ba, S.; Qu, Q.; Zhang, K.; Groot, J.C.J. Meta-analysis of greenhouse gas and ammonia emissions from dairy manure composting. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 193, 126–137. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Xue, W.; Guo, H.; Li, X.; Zou, G.; Zhao, T.; Dong, H. The characteristics of carbon, nitrogen and sulfur transformation during cattle manure composting—based on different aeration strategies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public health 2019, 16, 3930. [CrossRef]

- Fillingham, M.A.; VanderZaag, A.C.; Burtt, S.; Baldé, H.; Ngwabie, N.M.; Smith, W.; Hakami, A.; Wagner-Riddle, C.; Bittman, S.; MacDonald, D. Greenhouse gas and ammonia emissions from production of compost bedding on a dairy farm. Waste Manag. 2017, 70, 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Li, G.; Tang, Q.; Ma, X.; Wang, G.; Schuchardt, F. Effects of aeration method and aeration rate on greenhouse gas emissions during composting of pig feces in pilot scale. J. Environ. Sci. (China) 2015, 31, 124–132. [CrossRef]

- Pardo, G.; Moral, R.; Aguilera, E.; Prado, A. Gaseous emissions from management of solid waste: a systematic review. Glo. Chang. Biol. 2015, 21, 1313–1327. [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.N.; Sharma, M.; Aneja, V.P.; Balasubramanian, R. Ammonia in the atmosphere: a review on emission sources, atmospheric chemistry and deposition on terrestrial bodies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 8092–8131. [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.N.; Sharma, M. Degradation of SO2, NO2 and NH3 leading to formation of secondary inorganic aerosols: An environmental chamber study. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 4015–4024. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Kishore, S.; Tripathi, S.N.; Behera, S.N. Role of atmospheric ammonia in the formation of inorganic secondary particulate matter: a study at Kanpur, India. J. Atmos. Chem. 2007, 58, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Guo, X.; Cheng, L.; Cheng, S.; Chen, D.; Wang, W.; Liu, B. Reducing PM2. 5 and secondary inorganic aerosols by agricultural ammonia emission mitigation within the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, China. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 219, 116989. [CrossRef]

- Backes, A.; Aulinger, A.; Bieser, J.; Matthias, V.; Quante, M. Ammonia emissions in Europe, part I: Development of a dynamical ammonia emission inventory. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 131, 55–66. [CrossRef]

- Erisman, J.W.; Schaap, M. The need for ammonia abatement with respect to secondary PM reductions in Europe. Environmental Pollution 2004, 129, 159–163. [CrossRef]

- Pozzer, A.; Tsimpidi, A.P.; Karydis, V.A.; Meij, A.; Lelieveld, J. Impact of agricultural emission reductions on fine-particulate matter and public health. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2017, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Kashima, S.; Yorifuji, T.; Bae, S.; Honda, Y.; Lim, Y.; Hong, Y. Asian dust effect on cause-specific mortality in five cities across South Korea and Japan. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 128, 20–27. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.J; Cho, S.H.; Chun, Y.; Lagarde, F.; Pershagen, G. Effects of the Asian dust events on daily mortality in Seoul, Korea. Environ. Res. 2002, 90, 1–5.

- Jeong, D. Socio-economic costs from yellow dust damages in South Korea. Korean Soc. Sci. J. 2008, 35, 1–29.

- Wang, Y.; Niu, B.; Ni, J.; Xue, W.; Zhu, Z.; Li, X.; Zou, G. New insights into concentrations, sources and transformations of NH3, NOx, SO2 and PM at a commercial manure-belt layer house. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 262, 114355.

- Løes, A.; Khalil, R.; McKinnon, K. Exhaust Gas Concentrations and Elemental Losses from a Composting Drum Treating Horse ManureCompost. Sci. Util. 2020, 28, 36–48.

- Fukumoto, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Kuroda, K.; Waki, M.; Yasuda, T. Effects of struvite formation and nitratation promotion on nitrogenous emissions such as NH3, N2O and NO during swine manure composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 1468–1474. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, H.; Zhu, Z.; Li, L.; Zhou, T.; Jiang, B.; Xin, H. CH4, NH3, N2O and NO emissions from stored biogas digester effluent of pig manure at different temperatures. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 217, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Huang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, B.; Peng, H.; Qin, P.; Wu, G. Concentrations and emissions of particulate matter and ammonia from extensive livestock farm in South China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 1871–1879. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.J.; Wood, D.J.; Van Heyst, B.J. The development of seasonal emission factors from a Canadian commercial laying hen facility. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 86, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, J.; Su, J.; Gates, R.S. Characterization of trace elements and ions in PM10 and PM2. 5 emitted from animal confinement buildings. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 7096–7104. [CrossRef]

- Matsusada, J.; Maeda, T.; Ohmiya, K. Ammonia emissions from composting of livestock manure 2002, 283–286.

- Bai, M.; Flesch, T.; Trouvé, R.; Coates, T.; Butterly, C.; Bhatta, B.; Hill, J.; Chen, D. Gas emissions during cattle manure composting and stockpiling. J. Environ. Qual. 2020, 49, 228–235. [CrossRef]

| Temperature (℃) | Relative Humidity (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Average | 22.3 | 82 |

| Min. | 16.1 | 32 |

| Max. | 34.1 | 100 |

| St. Dev. | 3.6 | 15.9 |

| Daily Max. Average | 27.1 | 98.4 |

| St. Dev. | 2.9 | 2.9 |

| Daily Min. Average | 18.3 | 60.2 |

| St. Dev. | 1.3 | 13.7 |

| NH3 Int | NH3 Ext Hi | NH3 Ext Lo | NO Fac | NO2 Fac | SO2 Fac | PM2.5 Int | PM2.5 Ext | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg m−3 | μg m−3 | ||||||||

| Week Day | Mean | 63.951 | 3.850 | 3.155 | 34.007 | 9.000 | 371.004 | - | 23.570 |

| Std. Err. | 2.530 | 0.070 | 0.366 | 4.052 | 1.846 | 30.452 | - | 3.832 | |

| Week Night | Mean | 54.217 | 3.555 | 2.053 | 31.928 | 4.991 | 321.118 | - | 22.171 |

| Std. Err. | 2.074 | 0.084 | 0.092 | 5.421 | 1.052 | 23.671 | - | 3.277 | |

| W / end Day | Mean | 66.278 | 3.793 | 2.079 | 27.939 | 10.332 | 264.985 | - | 22.337 |

| Std. Err. | 8.157 | 0.179 | 0.092 | 6.616 | 1.363 | 45.646 | - | 3.529 | |

| W / end Night | Mean | 37.911 | 3.180 | 1.736 | 49.723 | 7.032 | 147.155 | - | 23.319 |

| Std. Err. | 2.558 | 0.112 | 0.056 | 13.629 | 1.328 | 15.669 | - | 2.644 | |

| Over all | Mean | 57.063 | 3.642 | 2.425 | 33.350 | 7.276 | 307.224 | 36.901 | 23.713 |

| Std. Err. | 1.316 | 0.056 | 0.159 | 3.153 | 0.846 | 17.426 | 2.599 | 1.959 | |

| NH3 Int | NH3 Ext wi | NH3 Ext gr | NO Fac | NO2 Fac | SO2 Fac | PM2.5 Int | PM2.5 Ext | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp | 0.101 | 0.086 | 0.071 | -0.191 | 0.476 | 0.073 | 0.277 | 0.033 | |

| RH | -0.072 | -0.012 | -0.063 | 0.059 | -0.600 | -0.047 | -0.322 | 0.078 | |

| PM2.5 Paju | 0.191 | 0.154 | -0.139 | 0.072 | 0.096 | 0.053 | 0.341 | 0.666 | |

| NO2 Paju | 0.023 | -0.025 | 0.084 | 0.412 | |||||

| SO2 Paju | -0.204 | -0.017 | 0.404 | ||||||

| NH3 Int | |||||||||

| NH3 Ext wi | 0.831 | ||||||||

| NH3 Ext gr | 0.429 | 0.345 | *=0.05 | ||||||

| NO Fac | 0.191 | 0.140 | 0.107 | **=0.01 | |||||

| NO2 Fac | -0.084 | -0.139 | -0.102 | 0.290 | ***=0.001 | ||||

| SO2 Fac | 0.751 | 0.702 | 0.400 | -0.008 | -0.201 | ||||

| PM2.5 Int | 0.047 | 0.117 | 0.026 | 0.063 | 0.051 | 0.155 | |||

| PM2.5 Ext | 0.096 | 0.072 | -0.110 | -0.030 | 0.028 | -0.065 | 0.088 |

| Emission Rate | Scaled Emission Rates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg min−1 m−3 | g h−1 m−2 manure | g h−1 m−3 manure | g kg−1 manure* | |

| Mean | 7.28 | 2.77 | 1.85 | 1.52 |

| Std. Error | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.1 | 0.09 |

| * over entire 18 day composting period | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).