1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has exhibited rapid improvement in recent years, with a lot of potential application in all aspects of medicine and healthcare. The most recent leap in AI capabilities and applications was demonstrated with the release of Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT 3.5 and 4 from OpenAI [

1].

LLMs originate from the transformer neural network architecture [

2], and they are (pre)trained on large amounts of internet and textbook data, with the goal of predicting the next word (token) in a sentence (sequence) [

3]. Moreover, recent state-of-the-art foundation models are multimodal, ie. other than text, they are also trained on images, videos, and even audio (eg. GPT-4o) [

4].

This type of pretraining via self-supervised learning leads to impressive performances at a wide array of downstream tasks and benchmarks [

5]. For example, the most capable models like GPT-4 and Claude 3.5 achieve very high scores in the Massive Multi-task Language Understanding (MMLU) benchmark (86.4% and 86.8%, respectively) [

6,

7]. MMLU benchmark was designed to test the model’s understanding and problem-solving capabilities across multiple topics and domains (from mathematics and computer science, to law and medicine). For reference, an expert-level human (at particular subject) in average achieves a score of 89.8% [

7].

A lot of aspects of medicine and healthcare can benefit from the use of LLMs. From the automation of administrative tasks, to improving and personalizing education, enabling decision-support tools, and others. Moreover, models like GPT-4 have demonstrated impressive capabilities on rigorous assessments such as medical licensing examinations, suggesting a robust foundation for medical reasoning, which is an essential component that enables later usage in medical education and decision-support [

8,

9].

Given the amount of time doctors currently spend on drafting medical documentation, a significant proportion of this time could be saved by incorporating LLMs into the process. With a proper and detailed prompt (text input provided by the user), LLMs are great for drafting documents with proper structure and filling them with relevant patient data provided in the context [

10]. By automating aspects of this process, LLMs could significantly alleviate the administrative burden faced by clinicians, potentially enhancing efficiency and reducing burnout.

As mentioned, LLMs are poised to play a transformative role in medical education and as decision support systems [

11,

12]. They could serve as an on-demand knowledge base for less experienced practitioners, offering guidance that aligns with the latest medical standards and guidelines, especially when enhanced with techniques like Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) [

13,

14]. Such tools integrate real-time, up-to-date medical information (like the Uptodate and Statspearls databases) and treatment protocols directly into the LLM’s responses, enriching the model's utility and accuracy [

13,

15].

However, the integration of LLMs into clinical practice is not without challenges. Studies have shown mixed results regarding their effectiveness as decision support tools. For instance, while some research highlights their proficiency in generating accurate diagnostic and treatment recommendations based on clinical casebooks, other studies, particularly in specialized fields like precision oncology, indicate that LLMs may not yet achieve the reliability and personalized insight provided by human experts [

12,

16].

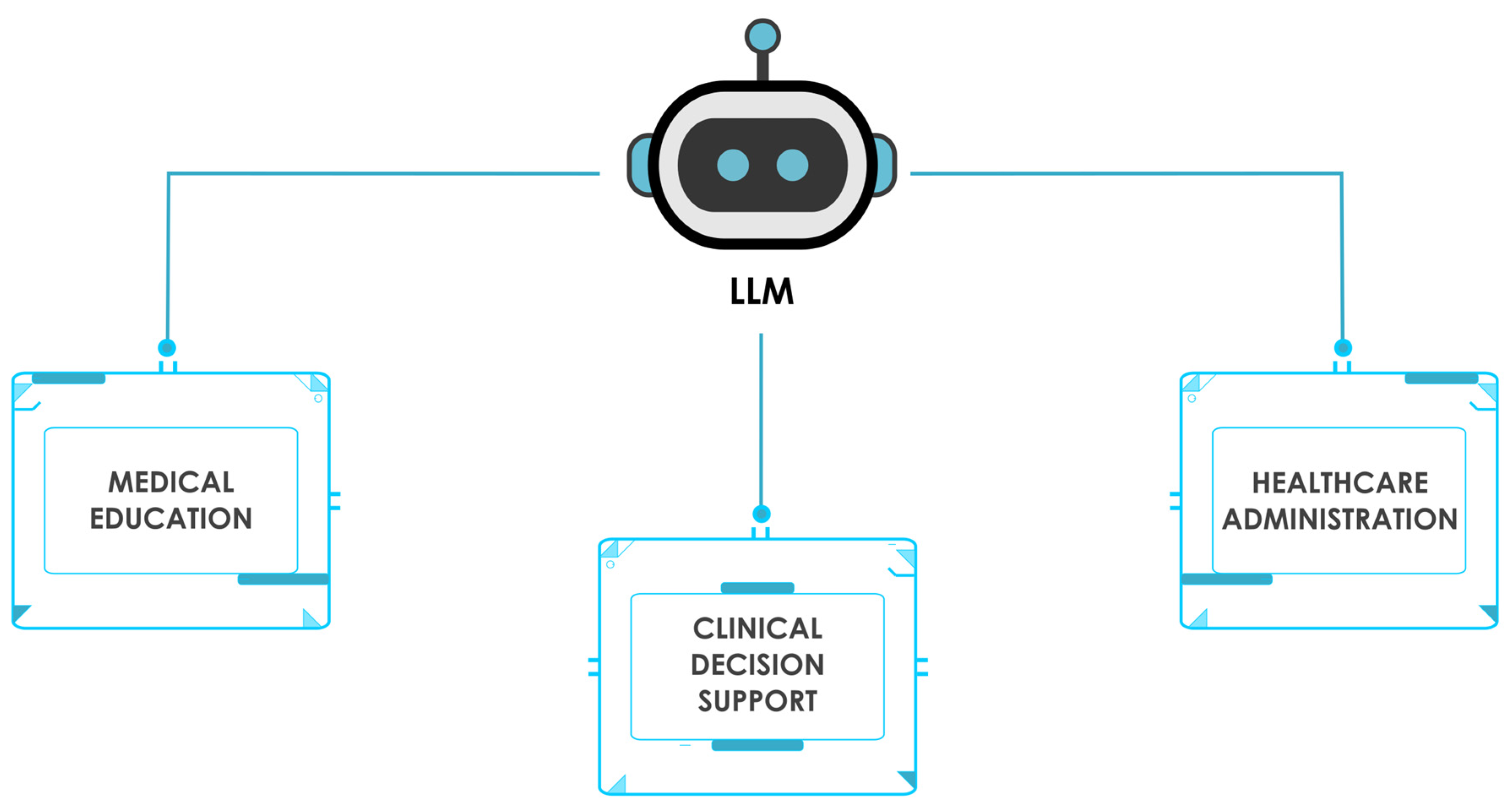

In this comprehensive review, we will critically examine the current applications and future potential of Large Language Models (LLMs) across three key healthcare domains: medical education, clinical decision support and knowledge retrieval, and healthcare administration (

Figure 1.). By synthesizing the latest research findings, we aim to provide a balanced assessment of the benefits, challenges, and limitations associated with LLM integration in these areas. Furthermore, we will discuss the ethical considerations and regulatory challenges that must be addressed to ensure the responsible deployment of LLMs in healthcare settings. Finally, we will explore emerging techniques and future directions for enhancing LLM performance, reliability, and safety, highlighting the importance of collaborative efforts between AI developers, healthcare professionals, and policymakers in realizing the transformative potential of LLMs in medicine while prioritizing patient well-being and the integrity of healthcare delivery.

2. Materials and Methods

To find the relevant literature for this comprehensive review, two authors have independently performed a search in the following databases:

The following keywords were used in the search: (LLMs AND medicine) OR (LLMs AND healthcare) OR (LLMs AND medical decision support) OR (LLMs and medical education). The initial combined PubMed search yielded 613 studies, which we then filtered by performing a step-wise search. The search term (LLMs AND medicine) yielded 504 search results. The term (LLMs AND healthcare) yielded 216 search results, (LLMs AND medical decision support) yielded 55 results, and (LLMs and medical education) yielded 159 results. Searching for (LLMs and medicine) on ArXiv yielded 117 results. Relevant studies were filtered by title and abstract to finally extract studies pertaining to LLM usage in medical education, clinical decision support and healthcare administration. This approach has yielded a final of 21 studies we deemed the most relevant.

3.1. Large Language Models in Medical Education

LLMs have significant potential to improve all phases of medical education programs, from curriculum development to augmenting teaching methodologies, personalizing study plans and learning materials, streamlining medical research and literature review [

17]. In this section we will review and provide examples from studies that have investigated LLM application in medical education (

Table 1.).

In one single-site exploratory evaluation of publicly available Chat-GPT-3.5, researchers have implemented the tool into the daily attending rounds of a general internal medicine inpatient service at a large urban academic medical center. They have noted how ChatGPT integration proved beneficial for addressing medical knowledge gaps, in drafting initial differential diagnosis, as well as for supporting acute care decision making [

18]. On the other hand, the authors warn of LLM biases, misinformation, ethics, and health equity as areas of concern and limitations [

18].

Furthermore, in one review article, Abd-Alrazaq et al. outline the pearls and pitfalls of LLM usage in medical education [

17]. For example, LLMs can provide great usecase as acting like virtual patients with whom students can interact. They can be personalized medical tutors, can generate medical case studies, and develop personalized study plans. The current major limitation, especially concerning medicine where errors have to be minimized, is in LLM hallucinations (generating inaccurate information). This problem is emphasized by the fact that LLMs tend to use a very assertive and confident/authoritative writing style, which makes it harder for students to spot the incorrect information. We can mitigate this issue by using techniques such as Retrieval-Augmented-Generation (RAG), which provides the relevant data (based on semantic similarity), directly into LLM context, and thus decreases the potential for hallucination [

19].

One other study that showcases the LLM’s strength in medical knowledge was performed by Bonilla et al., where GPT-4-turbo has outperformed lower-level radiation-oncology trainees [

20]. Whereby GPT-4-turbo has demonstrated clinical accuracy comparable to upper-level and superior to lower-level trainees in nearly all clinical domains [

20]. This fact proves that GPT-4-turbo has the necessary domain knowledge, and hence can be utilized for downstream medical education tasks.

Similar benefits of LLM usage in medical education are highlighted in an article by Benitez et al., while also expressing notable challenges like overreliance on AI, loss/dilution of critical thinking skills, and the risk of fostering academic misconduct [

21].

In one interesting study by Arraujo and Correia, the authors have investigated student perceptions on LLM usage and potential integration into their study program [

22]. The majority of students were satisfied with ChatGPT, finding it helpful for generating content, brainstorming, and rewriting text, despite some concerns about biases and informed use. The study proposed integrating ChatGPT into master's courses in medicine and medical informatics to enhance learning, assist in project planning, code generation, exam preparation, workflow exploration, and technical interviews, as well as simplifying concepts and solving problems in medical teaching [

22].

Similarly, in a study by Ali et al., the authors have investigated the accuracy of ChatGPT (3.5) in solving a wide range of assessments in healthcare education, with a primary focus on Dental Medicine [

23]. The study evaluated ChatGPT's performance on 50 different learning outcomes using multiple question formats, including MCQs, SAQs, SEQs, true/false, and fill-in-the-blank questions. ChatGPT accurately answered most knowledge-based assessments but struggled with image-based questions and critical literature appraisal, with word count being a notable limitation [

23]. The struggle with the image-based questions is somewhat expected due to relative lack of domain specific image data (compared to text).

Another study that investigated practical implementation of LLMs in medical education was performed by Ow et al. [

24]. The researchers have developed a custom GPT, which had access to an online platform for medical education ("MedEdMENTOR”), and investigated the usefulness of such a GPT system in helping medical researchers select theoretical constructs [

24]. MedEdMENTOR AI was tested against 6 months of qualitative research from 24 core medical educational journals, where it was asked to recommend 5 theories for each study's phenomenon. MedEdMENTOR AI correctly recommended the actual theoretical constructs for 55% (29 of 53) of the studies [

24].

Finally, one potential use-case for LLMs in medical education is in crafting multiple choice question examinations for medical students, as was shown in a study by Klang et al [

25] (

Table 1.)

In this study, researchers have studied the medical accuracy of GPT-4 in generating multiple choice medical questions. Out of 210 multi choice questions, only 1 generated question was deemed false, while 15% of questions necessitated revisions. While these results are promising, the study also highlighted important limitations. The AI-generated questions contained errors related to outdated terminology, age and gender insensitivities, and geographical inaccuracies, emphasizing the need for thorough review by specialist physicians before implementation. This underscores that while AI can be a valuable tool in medical education, human expertise still remains crucial for ensuring the quality and appropriateness of educational materials.

Similar findings were shown in another study that compared ChatGPT versus human in generating medical graduate exam multiple choice questions [

26] (

Table 1.). The researchers found no significant difference in question quality between questions drafted by A.I. versus humans, in the total assessment score as well as in other domains, while the questions generated by A.I. yielded a wider range of scores, while those created by humans were consistent and within a narrower range. These studies highlight the potential of using LLMs to generate exam content. Pairing that with techniques like Retrieval-Augmented-Generation (RAG) where we also provide the relevant knowledge base to the LLM, could also improve the question relevance, since the LLM would not rely only on its pretraining knowledge, but also on the relevant domain data [

27].

In summary, the studies reviewed in this section demonstrate the significant potential of LLMs in various aspects of medical education. From addressing knowledge gaps and supporting clinical decision-making to serving as virtual patients and personalized tutors, LLMs show promise in enhancing the learning experience for medical students and professionals. The integration of LLMs into medical education curricula appears to be well-received by students, offering benefits in content generation, exam preparation, and problem-solving. While LLMs like GPT-4 have shown impressive performance in certain medical domains, their limitations in areas such as image interpretation and critical analysis highlight the need for continued refinement and careful implementation. As the field progresses, further research is needed to optimize LLM use in medical education, addressing current limitations and developing best practices for their integration into existing educational frameworks. The development of specialized tools like MedEdMENTOR AI suggests a promising direction for tailoring LLMs to specific medical education needs, potentially revolutionizing how medical knowledge is acquired, applied, and evaluated in academic settings.

3.2. LLMs in Clinical Decision Support and Knowledge Retrieval

As outlined previously, LLMs show great promise in clinical decision support and knowledge retrieval. In this section we will review the present state of the evidence for this subject.

In one recent study by Wang et al., researchers have shown how LLM utility in medical knowledge retrieval can be greatly improved by augmenting the LLMs with medical textbooks [

28]. The authors introduce a specific RAG pipeline, which consists from the following parts: 1) “Query Augmenter”, 2) “Hybrid Textbook Retriever”, 3) “Knowledge Self-Refiner” and 4) “LLM Reader” [

28]. Firstly, in the “Query Augmenter”, GPT-3.5 is used to rewrite and expand the user query, in order to improve the semantic search and retrieval results. Secondly, “Hybrid Textbook Retriever” uses both sparse and dense Retrievers, after which the retrieved text chunks are also sent to a reranking model. In the next step, GPT-3.5 is again used, but this time as a “Relevance Filter” and a “Usefulness Filter”, in which the model filters the retrieved text chunks and narrows down the final context sent to the aggregator LLM. Finally, in the “LLM Reader” part, the aggregator LLM of choice (eg. GPT-4), receives both the original user input, as well as the retrieved relevant and filtered context, based on which it generates an improved response [

28]. Implementing such a pipeline improves the score on medical QA tasks ranging from 11.6% to 16.6%, while also significantly reducing hallucinations. [

28] (

Table 2.). This study outlines the potential of using RAG for solving the common pitfalls of using LLMs in medicine (like the lack of domain knowledge and hallucinations).

In a diagnostic study by Benary et al., researchers evaluated four LLMs (ChatGPT, Galactica, Perplexity and BioMedLM) as support tools for precision oncology, comparing their performance to an expert physician in generating treatment options for 10 fictional advanced cancer cases [

12]. The study found that while LLMs generated more treatment options than the expert, their precision and recall were lower, with combined LLM performance achieving an F1 score of 0.29 [

12]. Despite not matching human expert quality, LLMs produced at least one helpful option per case and identified two unique useful treatments, suggesting potential to complement established procedures. However, the study had limitations, including a small sample size and the use of fictional cases, which may affect the generalizability of the results [

12] (

Table 2.).

The limitations of current open-source LLMs in clinical decision-making were further demonstrated in a subsequent study, which revealed significant performance gaps between these models and clinicians in patient diagnosis [

29]. The research found that existing open-source LLMs (specifically Llama 2 Chat (70B), Open Assistant (70B), WizardLM (70B), Camel (70B) and Meditron (70B)) struggled to adhere to diagnostic and treatment guidelines, and encountered difficulties with fundamental tasks such as laboratory result interpretation. The authors concluded that these models are not yet suitable for autonomous clinical decision-making and require substantial clinician oversight. However, it is important to note that both this study and the one by Benary et al. may not reflect the capabilities of the most recent open-source models, such as Llama 3 70b and 405b, which have demonstrated performance comparable to GPT-4 [

29,

30]. This rapid advancement in model capabilities highlights a persistent challenge in AI research: the potential for studies to become outdated during the publication process due to the accelerated pace of technological development. Consequently, the reported underperformance of open-source models may not accurately represent the current state of the field, as the latest iterations have shown marked improvements across relevant benchmarks.

In another comparative study by Marchi et al., researchers evaluated ChatGPT's ability to provide therapeutic recommendations for head and neck cancers by simulating scenarios from NCCN Guidelines [

31]. The study assessed ChatGPT's performance across 68 hypothetical cases and 204 clinical scenarios, comparing its responses to NCCN Guidelines for primary treatments, adjuvant treatments, and follow-up care. Results showed that ChatGPT demonstrated high sensitivity and overall accuracy in addressing NCCN-related queries, although some inaccuracies were noted, particularly in primary treatment scenarios [

31]. The researchers concluded that while ChatGPT shows promise in providing treatment suggestions aligned with NCCN Guidelines, challenges remain regarding AI interpretability in clinical decision-making, emphasizing the need for collaboration between AI models and medical experts in advancing personalized cancer care [

31] (

Table 2.).

Another example of LLM potential in clinical decision support was given in a proof-of-concept study by Sorin et al., where researchers evaluated ChatGPT-3.5 as a support tool for breast tumor board decision-making [

32]. The study involved inputting clinical information from ten consecutive breast tumor board patients into ChatGPT and comparing its management recommendations to those of the actual tumor board. Results showed that ChatGPT's recommendations aligned with the tumor board's decisions in 70% of cases, with two senior radiologists independently grading ChatGPT's performance favorably across summarization, recommendation, and explanation categories [

32]. The researchers concluded that while these initial results demonstrate potential for LLMs as decision support tools in breast tumor boards, clinicians should be aware of both the benefits and potential risks associated with this technology [

32] (

Table 2.). Again, since GPT-3.5 was used, we can only expect that performance will be better with more recent models like GPT-4, and Claude-3.5. Further studies on a larger number of real-world examples should be conducted to obtain a more robust evaluation.

One other interesting study has shown the potential of ChatGPT-4 in predicting refractive surgery categorizations [

33]. Ćirković and Katz compared ChatGPT-4's performance to a clinician's categorizations using data from 100 refractive clinic patients. The study found statistically significant agreement between ChatGPT-4 and the clinician, with a Cohen κ coefficient of 0.399 for 6 categories and 0.610 for binary categorization [

33]. While the results were promising, the researchers noted limitations such as temporal instability, response variability, and dependency on a single human rater, emphasizing the need for further research to validate the use of LLMs in healthcare decision-making processes.

Researchers from Stanford have conducted a study in which they aimed to tackle the current LLM limitations (like response variability, lack of domain medical knowledge, and hallucinations), by incorporating a RAG system connected to medical databases like PubMed and UpToDate [

34]. They have also created a new ClinicalQA benchmark to avoid contamination and to investigate the RAG-LLM performance on questions that are more in line with everyday clinical practice and medical decision making [

34]. Their RAG-LLM system, called Almanac, has outperformed other AI models in the ClinicalQA evaluation, demonstrating superior performance in factuality, completeness, and user preference across various medical specialties. Additionally, Almanac excelled in providing accurate citations, handling adversarial prompts, and achieving significantly higher scores on the LiveQA dataset compared to previous best-performing models [

34] (

Table 2.).

All aforementioned studies describe a common theme, how LLMs show promise as clinical decision support tools, given their accuracy in providing the correct diagnosis and treatment recommendations (

Table 2.). Furthermore, most of the studies also state the same limitations, such as LLM hallucinations, lack of domain-specific knowledge, and a lack of LLM response consistency. We already have solutions to these limitations, as can be seen in the works by Wang et al. and Zakka et al., where incorporating vector embeddings and semantic search to retrieve relevant medical knowledge (from up-to-date databases), along other methods like knowledge graphs, reranking models and query transforms. With the ongoing release of advanced large language models (LLMs) incorporating novel algorithmic enhancements, it is reasonable to anticipate continued improvements in clinical performance. Consequently, the integration of LLMs into real-world clinical workflows can be expected in the foreseeable future.

3.3. LLMs in Healthcare Administration

Large language models have the potential to automate lots of tasks from healthcare administration, that currently take up a lot of clinician’s time. Such as clinical note taking, drafting patient or diagnostic reports, and patient data summarization. What is more, LLMs could help in accurately coding medical procedures and diagnoses for billing purposes, potentially reducing errors and improving reimbursement processes.

In this section we will review studies that investigated the LLM use-case in healthcare administration.

Huang et al. have investigated ChatGPT-3.5’s potential for extracting structured data from clinical notes [

35]. In particular, ChatGPT-3.5 demonstrated high accuracy in extracting pathological classifications from lung cancer and pediatric osteosarcoma pathology reports, outperforming traditional NLP methods and achieving accuracy rates of 89% to 100% across different datasets [

35]. The study highlights the potential of LLMs in efficiently processing clinical notes for structured information extraction, which could significantly support healthcare research and clinical decision-making without requiring extensive task-specific human annotation and model training (

Table 3.).

In another study, Wei et al. explored ChatGPT's capability in converting COVID-19 symptom narratives into structured symptom labels [

36]. The study found that GPT-4 achieved high specificity (0.947-1.000) for all symptoms and high sensitivity for common symptoms (0.853-1.000), with moderate sensitivity for less common symptoms (0.200-1.000) using zero-shot prompting [

36]. The research demonstrates ChatGPT's efficacy as a valuable tool in medical research, particularly for efficiently extracting structured data from free-text responses, which could accelerate data compilation and synthesis in future disease outbreaks and improve the accuracy of symptom checkers (

Table 3.).

Moreover, when investigating the feasibility of LLMs in clinical text summarization, Van Veen et al. found that in most cases, summaries from the best-adapted LLMs were deemed either equivalent (45%) or superior (36%) to those produced by medical experts, as evaluated by 10 physicians on completeness, correctness, and conciseness [

37]. This research suggests that integrating LLMs into clinical workflows could significantly reduce documentation burden, allowing clinicians to allocate more time to patient care, while also highlighting the need for careful consideration of potential errors and safety implications (

Table 3.).

In another similar study, Liu et al. investigated the potential of ChatGPT in medical dialogue summarization, comparing it with fine-tuned pre-trained language models like BERTSUM and BART [

38]. While BART achieved higher scores in automated metrics such as ROUGE and BERTScore, ChatGPT's summaries were more favored by human medical experts in manual evaluations, demonstrating better readability and overall quality [

38]. The study highlights the promise of LLMs like GPT-3.5 in automated medical dialogue summarization, while also emphasizing the limitations of current automated evaluation metrics in assessing the outputs of these advanced models (

Table 3.).

Other authors have investigated LLM’s ability to transform inpatient discharge summaries to a patient-friendly language and format [

39]. The study found that LLM-transformed discharge summaries were significantly more readable and understandable, with lower Flesch-Kincaid Grade Levels (6.2 vs 11.0) and higher PEMAT understandability scores (81% vs 13%) compared to the original summaries [

39]. While the results demonstrate the potential of LLMs in improving patient comprehension of medical information, the study also highlighted the need for improvements in accuracy, completeness, and safety before implementation, emphasizing the importance of physician review to address potential safety concerns (

Table 3.).

The aforementioned studies demonstrate the significant potential of current Large Language Models (LLMs) in healthcare administration. These findings suggest that the integration of LLMs into daily clinical workflows could substantially alleviate the administrative burden on physicians and other healthcare professionals. By automating tasks such as clinical note summarization, patient data extraction, and report generation, LLMs show promise in streamlining administrative processes, potentially allowing healthcare workers to allocate more time to direct patient care.

4. Mitigating Current LLM Limitations in Healthcare

In this section, we will more closely explore the techniques which can be implemented to mitigate current LLM limitations in the healthcare setting (such as hallucinations and the lack of domain-specific medical knowledge). Specifically, we will focus on Retrieval-Augmented-Generation (RAG), where we will outline what contributes to a successful RAG system and what are its main functionalities.

Retrieval-Augmented-Generation (RAG) is a technique that allows the addition of semantically relevant context to the input/prompt we provide to LLMs. The main constituents of RAG are: 1) relevant knowledge base, 2) embedding models, 3) vector database, 4) search via semantic similarity. Relevant knowledge base represents the additional data we want to provide to the LLM’s context, eg. books and research papers (pdf files) or external medical knowledge databases (like StatsPearls or Up-to-date). Embedding models are specialized machine learning models that transform text into numerical vector representations that capture semantic meaning and relationships. In the medical domain, these models can be specifically fine-tuned to understand complex medical terminology and concepts, with applications ranging from disease diagnosis to patient risk stratification. The choice of embedding model is particularly important in healthcare applications, as it directly affects the quality and relevance of retrieved medical information, with domain-specific models often performing better at capturing the nuances of medical language.

A vector database functions as a specialized storage system that maintains both textual segments and their corresponding vector representations, facilitating subsequent retrieval during semantic search operations. The semantic search mechanism operates through a multi-step process: initially, the user's query undergoes vectorization through an embedding model, followed by the computation of vector similarity metrics (utilizing dot product or cosine similarity calculation) between the query vector and the stored vector representations. This process culminates in the identification and retrieval of the most semantically relevant text segments, which are then incorporated into the LLM's contextual window. The mathematical formula for similarity computation can be expressed as:

Next, we will provide a specific example of how might RAG be used to improve LLM performance in the clinical decision-making setting. For example, as input we have patient data for a particular visit (signs and symptoms, physical examination results, laboratory results, and other diagnostic procedures), and based on this input we want the LLM to provide support in differential diagnosis and therapy recommendations. The RAG system can be connected to an external database like UptoDate, and based on the similarity of input text (eg. signs and symptoms), fetch and provide the most relevant text chunks from the database. Which can then provide the LLM with additional hints of what diagnosis might be considered given a specific set of symptoms. Then, in the next step, after the LLM provides the differential diagnosis, we can do another round of RAG, and fetch the latest therapy guidelines for a given diagnosis, which are finally synthesized and provided to the user as the LLM’s response.

We also provide a code example of performing RAG for healthcare, by connecting the LLM to an open-source StatsPearls database from PubMed (as inspired by Xiong et al.) [

15]. We first preprocessed 2332 StasPearls articles as jsonl files, after which we embed them to a vector database utilizing open-source embedding model form “HuggingFace” (“all-MiniLM-L6-v2”), the “Langchain” library, and GPT-4 from OpenAI for response synthesis. Finally, we showcase how such a RAG system can be used for improving patient care in a primary physician’s office setting, where the initial input is given by ICD-code diagnosis and current treatment the patient takes. Given the initial input, LLM first generates a set of questions about how to improve patient care for a given case, which are then used to extract the relevant text chunks from the StatsPearls database. Initial patient data and relevant retrieved content are then provided to the LLM’s context for synthesizing the final recommendations. Code and relevant data are available at:

https://github.com/vrda23/Medical-RAG-showcase.

5. Ethical Considerations and Regulatory Challenges

As with other high impact technologies, LLM usage also raises major ethical concerns and regulatory challenges, that need to appropriately dealt with prior to successful integration into a real-world clinical practice. Firstly, we must take care of patient privacy and data security. This raises a concern in outsourcing patient data to close-source API providers like OpenAI or Anthropic, where patient data could be misused/used in future LLM training. Hence, hospitals could potentially host their own versions of open-source models, and therefore not worry about patient data leakage. LLMs must be implemented in ways that ensure full HIPAA compliance and protection of sensitive patient information. Moreover, clear protocols are needed for data handling, storage, and transmission when LLMs are used to process patient records.

Also, questions remain about who bears legal responsibility when LLM-assisted decisions lead to adverse outcomes? For starters, the role of LLMs needs to be clearly defined as decision support tools rather than autonomous decision makers.

There is also the challenge of bias in medical pretraining data. LLMs can perpetuate or amplify existing healthcare disparities through biased outputs based on protected attributes like race, gender, or socioeconomic status. Studies show that even larger models or those fine-tuned on medical data are not necessarily less biased [

40]. Hence, proactive approaches to fairness in LLM development and deployment are needed to prevent exacerbating health inequities.

6. Future Direction and Conclusion

In contrast to current LLMs, there has been a new paradigm shift with the release of the latest OpenAI models, GPT-o1-preview and GPT-o1-mini [

41]. While the exact mechanism is closed-source, these models implement reinforcement learning techniques that enable them effectively to “reason”. For each question the models generate a long stream of reasoning steps (Chain-of-Thought) which enable longer test-time compute and in essence enable the model to spend more compute to “think” about a certain problem [

41]. This has led to impressive performance in areas like math, coding and formal logic. The models also show great promise in healthcare, and especially areas that benefit from improved reasoning capabilities, such as clinical decision support [

42]. This new paradigm in model pre-training extracts the most benefit in already mentioned area like math and coding where a clear reward signal can be derived. We argue how that can also hold true for medicine, where a clear reward signal (ie. gold standard solution) can also be derived from for example, diagnosis, prescribed medication, exact dosage, based on specific patient cases. This could in theory, lead to above-expert performance in certain subfields of medicine, or medicine in general, as similar underlying techniques were used in achieving superhuman performance in AlphaGo and chess [

43].

By reviewing the current state of the evidence of LLM usage feasibility in medical education, clinical decision support and knowledge retrieval, as well as in healthcare administration, we can conclude that LLMs hold great potential, and will most likely be integrated in real-world workflows in the near future. Common pitfalls that postpone current LLM integration into clinical workflows, such as hallucinations and lack of specific knowledge, can be mitigated with already mentioned techniques like RAG via vector retrieval or knowledge graphs. Other possible venue to explore is LLM fine-tuning, which could also improve performance at specific downstream tasks (eg. medical information extraction, or specific patient report draft generation) [

44]. Moreover, simply scaling the LLMs, and using better curated medical pretraining data, should also lead to improved performance across all medical benchmarks.

As the field rapidly evolves, it is crucial for healthcare professionals, researchers, and policymakers to stay informed about these developments and actively participate in shaping the responsible integration of LLMs in healthcare. Future research should focus on rigorous real-world evaluations, addressing ethical concerns, and developing standardized protocols for LLM implementation to ensure patient safety and improve overall healthcare delivery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.V. and J.B; methodology, J.V.; software, J.V.; investigation, J.V., M.V. and M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.V., Z.B. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, J.V. and M.V.; visualization, Z.B.; supervision, J.B.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- OpenAI. https://openai.com/research/gpt-4. 2023.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Minaee, S.; Mikolov, T.; Nikzad, N.; Chenaghlu, M.; Socher, R.; Amatriain, X.; Gao, J. Large language models: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.06196 2024. arXiv:2402.06196 2024.

- Yin, S.; Fu, C.; Zhao, S.; Li, K.; Sun, X.; Xu, T.; Chen, E. A survey on multimodal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.13549 2023.

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z. A survey of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.18223 2023. arXiv:2303.18223 2023.

- Lemos, J.I.; Resstel, L.B.; Guimarães, F.S. Involvement of the prelimbic prefrontal cortex on cannabidiol-induced attenuation of contextual conditioned fear in rats. Behavioural Brain Research 2010, 207, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrycks, D.; Burns, C.; Basart, S.; Zou, A.; Mazeika, M.; Song, D.; Steinhardt, J. Measuring massive multitask language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.03300 2020. arXiv:2009.03300 2020.

- Gilson, A.; Safranek, C.W.; Huang, T.; Socrates, V.; Chi, L.; Taylor, R.A.; Chartash, D. How Does ChatGPT Perform on the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE)? The Implications of Large Language Models for Medical Education and Knowledge Assessment. JMIR Medical Education 2023, 9, e45312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nori, H.; King, N.; McKinney, S.M.; Carignan, D.; Horvitz, E. Capabilities of gpt-4 on medical challenge problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.13375 2023.

- Clusmann, J.; Kolbinger, F.R.; Muti, H.S.; Carrero, Z.I.; Eckardt, J.-N.; Laleh, N.G.; Löffler, C.M.L.; Schwarzkopf, S.-C.; Unger, M.; Veldhuizen, G.P.; et al. The future landscape of large language models in medicine. Communications Medicine 2023, 3, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehandru, N.; Miao, B.Y.; Almaraz, E.R.; Sushil, M.; Butte, A.J.; Alaa, A. Evaluating large language models as agents in the clinic. npj Digital Medicine 2024, 7, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benary, M.; Wang, X.D.; Schmidt, M.; Soll, D.; Hilfenhaus, G.; Nassir, M.; Sigler, C.; Knödler, M.; Keller, U.; Beule, D.; et al. Leveraging Large Language Models for Decision Support in Personalized Oncology. JAMA Network Open 2023, 6, e2343689–e2343689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Jin, Q.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, A. Benchmarking retrieval-augmented generation for medicine. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.13178 2024.

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, X.; Jia, K.; Pan, J.; Bi, Y.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, H. Retrieval-augmented generation for large language models: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.10997 2023.

- StatPearls Publishing. Treasure Island, F. StatPearls [Database]. 2024.

- Sandmann, S.; Riepenhausen, S.; Plagwitz, L.; Varghese, J. Systematic analysis of ChatGPT, Google search and Llama 2 for clinical decision support tasks. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Alrazaq, A.; AlSaad, R.; Alhuwail, D.; Ahmed, A.; Healy, P.M.; Latifi, S.; Aziz, S.; Damseh, R.; Alabed Alrazak, S.; Sheikh, J. Large Language Models in Medical Education: Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Directions. JMIR Med Educ 2023, 1, 48291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skryd, A.; Lawrence, K. ChatGPT as a Tool for Medical Education and Clinical Decision-Making on the Wards: Case Study. JMIR Form Res 2024, 8, 51346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béchard, P.; Ayala, O.M. Reducing hallucination in structured outputs via Retrieval-Augmented Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.08189 2024.

- Loaiza-Bonilla, A.; Thaker, N.G.; Redjal, N.; Doria, C.; Showalter, T.; Penberthy, D.; Dicker, A.P.; Choudhri, A.; Williamson, S.; Shah, C.; et al. Large language foundation models encode clinical radiation oncology domain knowledge: Performance on the American College of Radiology Standardized Examination. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2024, 42, e13585–e13585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, T.M.; Xu, Y.; Boudreau, J.D.; Kow, A.W.C.; Bello, F.; Van Phuoc, L.; Wang, X.; Sun, X.; Leung, G.K.; Lan, Y.; et al. Harnessing the potential of large language models in medical education: promise and pitfalls. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2024, 31, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães Araujo, S.; Cruz-Correia, R. Incorporating ChatGPT in Medical Informatics Education: Mixed Methods Study on Student Perceptions and Experiential Integration Proposals. JMIR Med Educ 2024, 20, 51151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, K.; Barhom, N.; Tamimi, F.; Duggal, M. ChatGPT-A double-edged sword for healthcare education? Implications for assessments of dental students. Eur J Dent Educ 2024, 28, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ow, G.; Rodman, A.; Stetson, G.V. MedEdMENTOR AI: Can artificial intelligence help medical education researchers select theoretical constructs? In Proceedings of the medRxiv, 2023.

- E, K.; S, P.; R, G.; R, K.L.; A, B.; M, G.; T, O.; S, R.; V, R.; H, M.; et al. Advantages and pitfalls in utilizing artificial intelligence for crafting medical examinations: a medical education pilot study with GPT-4. BMC Medical Education 2023, 23, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, B.H.H.; Lau, G.K.K.; Wong, G.T.C.; Lee, E.Y.P.; Kulkarni, D.; Seow, C.S.; Wong, R.; Co, M.T. ChatGPT versus human in generating medical graduate exam multiple choice questions-A multinational prospective study (Hong Kong S.A.R., Singapore, Ireland, and the United Kingdom). PLoS One 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardhana, S.; Weerasekera, R.; Wen, E.; Kaluarachchi, T.; Rana, R.; Nanayakkara, S. Improving the Domain Adaptation of Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) Models for Open Domain Question Answering. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2023, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Chen, W. Augmenting black-box llms with medical textbooks for clinical question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.02233 2023. arXiv:2309.02233 2023.

- Hager, P.; Jungmann, F.; Holland, R.; Bhagat, K.; Hubrecht, I.; Knauer, M.; Vielhauer, J.; Makowski, M.; Braren, R.; Kaissis, G.; et al. Evaluation and mitigation of the limitations of large language models in clinical decision-making. Nature Medicine 2024, 30, 2613–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MetaAI. Introducing Llama 3.1. 2024.

- Marchi, F.; Bellini, E.; Iandelli, A.; Sampieri, C.; Peretti, G. Exploring the landscape of AI-assisted decision-making in head and neck cancer treatment: a comparative analysis of NCCN guidelines and ChatGPT responses. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2024, 281, 2123–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorin, V.; Klang, E.; Sklair-Levy, M.; Cohen, I.; Zippel, D.B.; Balint Lahat, N.; Konen, E.; Barash, Y. Large language model (ChatGPT) as a support tool for breast tumor board. npj Breast Cancer 2023, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćirković, A.; Katz, T. Exploring the Potential of ChatGPT-4 in Predicting Refractive Surgery Categorizations: Comparative Study. JMIR Form Res 2023, 28, 51798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakka, C.; Shad, R.; Chaurasia, A.; Dalal, A.R.; Kim, J.L.; Moor, M.; Fong, R.; Phillips, C.; Alexander, K.; Ashley, E.; et al. Almanac - Retrieval-Augmented Language Models for Clinical Medicine. Nejm Ai 2024, 1, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Yang, D.M.; Rong, R.; Nezafati, K.; Treager, C.; Chi, Z.; Wang, S.; Cheng, X.; Guo, Y.; Klesse, L.J.; et al. A critical assessment of using ChatGPT for extracting structured data from clinical notes. NPJ Digit Med 2024, 7, 024–01079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.I.; Leung, C.L.K.; Tang, A.; McNeil, E.B.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Kwok, K.O. Extracting symptoms from free-text responses using ChatGPT among COVID-19 cases in Hong Kong. Clin Microbiol Infect 2024, 30, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Veen, D.; Van Uden, C.; Blankemeier, L.; Delbrouck, J.-B.; Aali, A.; Bluethgen, C.; Pareek, A.; Polacin, M.; Reis, E.P.; Seehofnerová, A.; et al. Adapted large language models can outperform medical experts in clinical text summarization. Nature Medicine 2024, 30, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ju, S.; Wang, J. Exploring the potential of ChatGPT in medical dialogue summarization: a study on consistency with human preferences. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2024, 24, 024–02481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaretsky, J.; Kim, J.M.; Baskharoun, S.; Zhao, Y.; Austrian, J.; Aphinyanaphongs, Y.; Gupta, R.; Blecker, S.B.; Feldman, J. Generative Artificial Intelligence to Transform Inpatient Discharge Summaries to Patient-Friendly Language and Format. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulain, R.; Fayyaz, H.; Beheshti, R. Bias patterns in the application of LLMs for clinical decision support: A comprehensive study. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.15149 2024.

- OpenAI. Introducing OpanAI o1-preview. 2024.

- Xie, Y.; Wu, J.; Tu, H.; Yang, S.; Zhao, B.; Zong, Y.; Jin, Q.; Xie, C.; Zhou, Y. A Preliminary Study of o1 in Medicine: Are We Closer to an AI Doctor? arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.15277 2024.

- Silver, D.; Huang, A.; Maddison, C.J.; Guez, A.; Sifre, L.; van den Driessche, G.; Schrittwieser, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Panneershelvam, V.; Lanctot, M.; et al. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 2016, 529, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophe, C.; Kanithi, P.K.; Munjal, P.; Raha, T.; Hayat, N.; Rajan, R.; Al-Mahrooqi, A.; Gupta, A.; Salman, M.U.; Gosal, G. Med42--Evaluating Fine-Tuning Strategies for Medical LLMs: Full-Parameter vs. Parameter-Efficient Approaches. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.14779 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).