Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

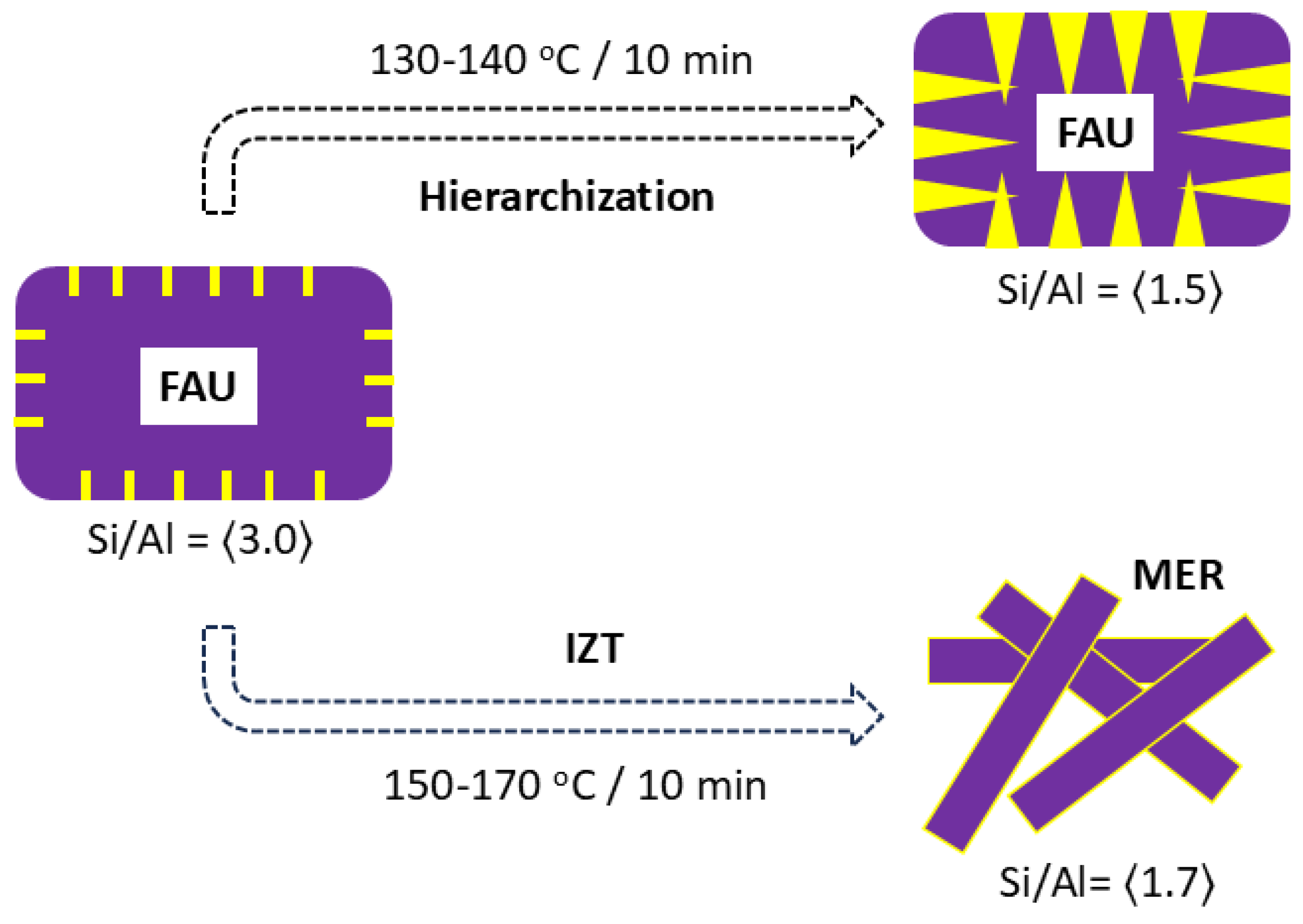

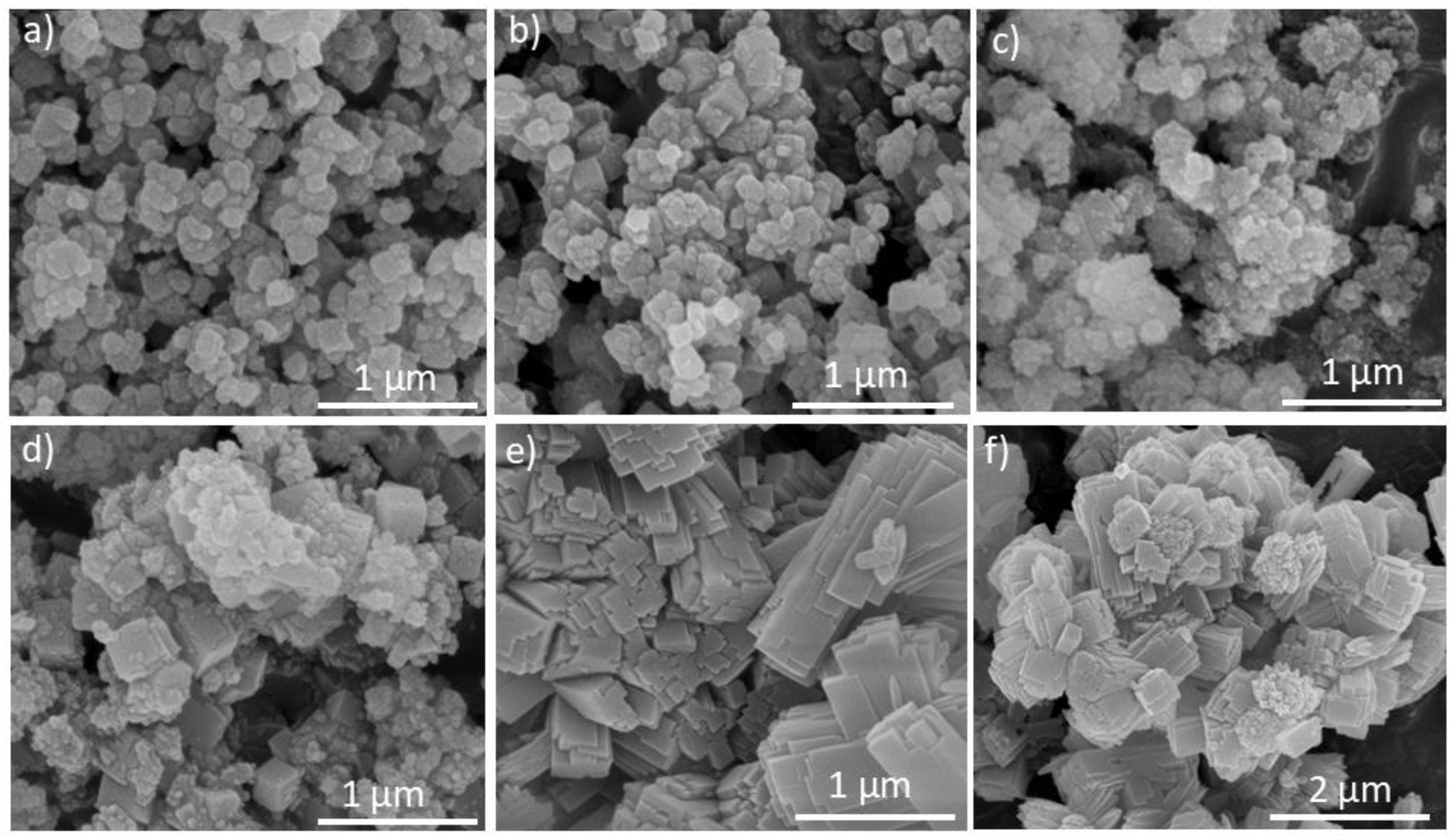

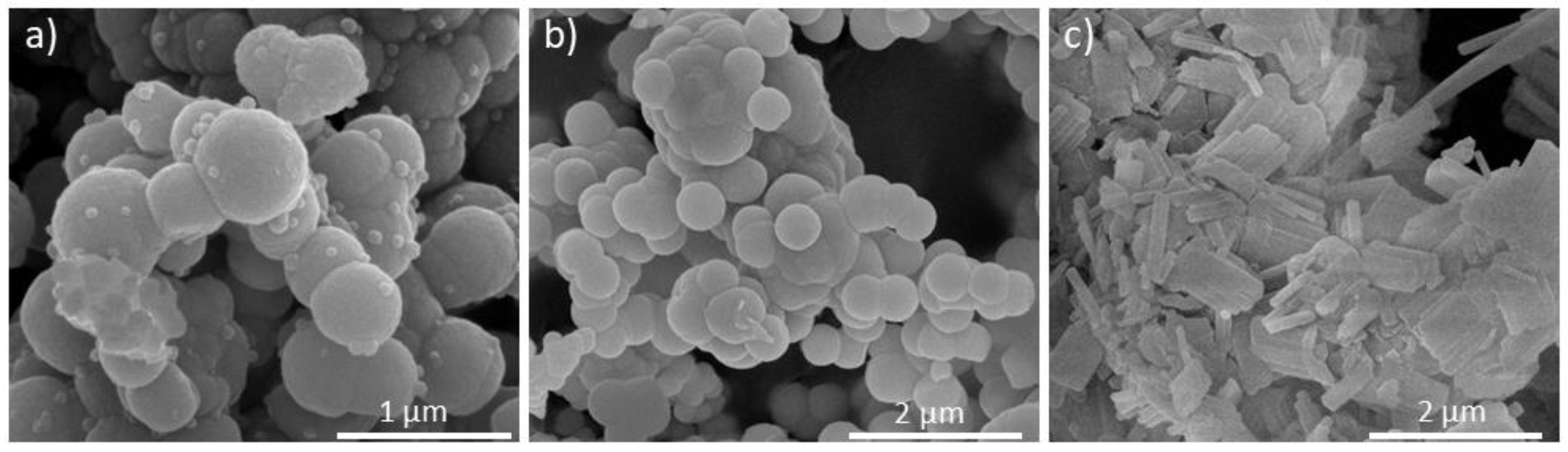

2. Results and Discussion

3. Experimental

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mallette, A.J.; Shilpa, K.; Rimer, J.D. The Current Understanding of Mechanistic Pathways in Zeolite Crystallization. Chemical Reviews 2024, 124, 3416–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdov, S.; Shivachev, B.; Koseva, I.; Petrova, P.; Petrova, N.; Titorenkova, R.; Nikolova, R. Metastable microporous lanthanide silicates – Light emitters capable of 3D-2D-3D transformations. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 492, 152355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.; Anderson, M.W. Microporous titanosilicates and other novel mixed octahedral-tetrahedral framework oxides. European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry 2000, 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrer, R.; Hinds, L.; White, E. 299. The hydrothermal chemistry of silicates. Part III. Reactions of analcite and leucite. Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed) 1953, 1466–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, T.; Itakura, M.; Sadakane, M. High Potential of Interzeolite Conversion Method for Zeolite Synthesis. Journal of the Japan Petroleum Institute 2013, 56, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdov, S. Interzeolite Transformation from FAU-to-EDI Type of Zeolite. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2024, 29, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devos, J.; Robijns, S.; Van Goethem, C.; Khalil, I.; Dusselier, M. Interzeolite Conversion and the Role of Aluminum: Toward Generic Principles of Acid Site Genesis and Distributions in ZSM-5 and SSZ-13. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 2516–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Mallette, A.J.; Rimer, J.D. Controlling Nucleation Pathways in Zeolite Crystallization: Seeding Conceptual Methodologies for Advanced Materials Design. J Am Chem Soc 2021, 143, 21446–21460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pornsetmetakul, P.; Coumans, F.J.A.G.; Heinrichs, J.M.J.J.; Zhang, H.; Wattanakit, C.; Hensen, E.J.M. Accelerated Synthesis of Nanolayered MWW Zeolite by Interzeolite Transformation. Chemistry – A European Journal 2024, 30, e202302931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Castro, M.J.; De Oliveira-Jardim, E.; Ramírez-Marquez, N.-T.; Trujillo, C.-A.; Linares, N.; García-Martínez, J. Hierarchical Catalysts Prepared by Interzeolite Transformation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 5163–5171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, J.C.; Correia, D.M.; Salado, M.; Gonçalves, R.; Ferdov, S.; de Zea Bermudez, V.; Costa, C.M.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Three-Component Solid Polymer Electrolytes Based on Li-Ion Exchanged Microporous Silicates and an Ionic Liquid for Solid-State Batteries. Advanced Engineering Materials, 2023; 25, 2200849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruter, D.V.; Pavlov, V.S.; Ivanova, I.I. Interzeolite Transformations as a Method for Zeolite Catalyst Synthesis. Petroleum Chemistry 2021, 61, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tendeloo, L.; Gobechiya, E.; Breynaert, E.; Martens, J.A.; Kirschhock, C.E.A. Alkaline cations directing the transformation of FAU zeolites into five different framework types. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 11737–11739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Yan, W.; Xu, R. Phase Transition Behavior of Zeolite Y under Hydrothermal Conditions. Acta Chimica Sinica 2017, 75, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakupec, N.; Ardila-Fierro, K.J.; Martinez, V.; Halasz, I.; Volavšek, J.; Algara-Siller, G.; Etter, M.; Valtchev, V.; Užarević, K.; Palčić, A. Mechanochemically Induced OSDA-Free Interzeolite Conversion. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2024, 12, 5220–5228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez González, N.K.; Díaz Guzmán, D.; Vargas Ramírez, M.; Legorreta García, F.; Chávez Urbiola, E.A.; Trujillo Villanueva, L.E.; Ramírez Cardona, M. Interzeolite conversion of a clinoptilolite-rich natural zeolite into merlinoite. Boletín de la Sociedad Española de Cerámica y Vidrio 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiyoda, O.; Davis, M.E. Hydrothermal conversion of Y-zeolite using alkaline-earth cations. Micropo. Mesopor. Mater. 1999, 32, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Xue, Z.; Dai, L.; Xie, S.; Li, Q. Preparation of Zeolite ANA Crystal from Zeolite Y by in Situ Solid Phase Iso-Structure Transformation. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2010, 114, 5747–5754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, S.; Tan, Z.; Liu, X.; Cao, J. Rapid and high efficient synthesis of zeolite W by gel-like-solid phase method. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2019, 281, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novembre, D.; Gimeno, D. Synthesis and characterization of analcime (ANA) zeolite using a kaolinitic rock. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 13373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdov, S.; Marques, J.; Tavares, C.J.; Lin, Z.; Mori, S.; Tsunoji, N. UV-light assisted synthesis of high silica faujasite-type zeolite. Micropo. Mesopor. Mater. 2022, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Xu, L.; Chen, P.; Ma, T.; Lin, C.; Wang, X.; Xu, D.; Sun, J. Hydroxyl free radical route to the stable siliceous Ti-UTL with extra-large pores for oxidative desulfurization. Chemical Communications 2019, 55, 1390–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Qiu, M.; Li, S.; Yang, C.; Shi, L.; Zhou, S.; Yu, G.; Ge, L.; Yu, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. Gamma-Ray Irradiation to Accelerate Crystallization of Mesoporous Zeolites. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2020, 59, 11325–11329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, T.; Liu, Z.; Iyoki, K.; Chokkalingam, A.; Yonezawa, Y.; Hotta, Y.; Ohnishi, R.; Matsuo, T.; Yanaba, Y.; Ohara, K.; et al. Ultrafast and continuous-flow synthesis of AFX zeolite via interzeolite conversion of FAU zeolite. Reaction Chemistry & Engineering 2021, 6, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, Y.-W.; Wong, K.-L.; Ling, T.C.; Ng, E.-P. Rapid synthesis of nanocrystalline zeolite W with hierarchical mesoporosity as an efficient solid basic catalyst for nitroaldol Henry reaction of vanillin with nitroethane. Materials Express 2018, 8, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatlier, M.; Barış Cigizoglu, K.; Tokay, B.; Erdem-Şenatalar, A. Microwave vs. conventional synthesis of analcime from clear solutions. Journal of Crystal Growth 2007, 306, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathupunya, M.; Gulari, E.; Wongkasemjit, S. Microwave preparation of Li-zeolite directly from alumatrane and silatrane. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2004, 83, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomyakov, A.P.; Nechelyustov, G.N.; Sokolova, E.; Bonaccorsi, E.; Merlino, S.; Pasero, M. Megakalsilite, a New Polymorph of KAISiO4 from the Khibina Alkaline Massif, Kola Peninsula, Russia: Mineral Description and Crystal Structure. The Canadian Mineralogist 2002, 40, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Ma, H.; Luo, Z.; Ma, X.; Guo, Q. Synthesis of KAlSiO4 by Hydrothermal Processing on Biotite Syenite and Dissolution Reaction Kinetics. Minerals 2021, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verboekend, D.; Nuttens, N.; Locus, R.; Van Aelst, J.; Verolme, P.; Groen, J.C.; Pérez-Ramírez, J.; Sels, B.F. Synthesis, characterisation, and catalytic evaluation of hierarchical faujasite zeolites: Milestones, challenges, and future directions. Chemical Society Reviews 2016, 45, 3331–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verboekend, D.; Vilé, G.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. Hierarchical Y and USY Zeolites Designed by Post-Synthetic Strategies. Advanced Functional Materials 2012, 22, 916–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdov, S. Conventional synthesis of layer-like zeolites with faujasite (FAU) structure and their pathway of crystallization. Micropo. Mesopor. Mater. 2020, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, I.I.; Wahab, A.W.; Mukti, R.R.; Taba, P. Synthesis and characterization of zeolite type ANA and CAN framework by hydrothermal method of Mesawa natural plagioclase feldspar. Applied Nanoscience 2023, 13, 5389–5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breck, D.W.; Flanigen, E.M. Synthesis and properties of union carbide zeolites L, X and Y. In Molecular Sieves; Society of Chemical Industry: London, 1968; pp. 47–60. [Google Scholar]

| IZT | Heating | Time | Temp (oC) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAU→MER | Conventional | 4 d | 95 | [13] |

| FAU→Cs-ANA | Conventional | 2 d | 95 | [13] |

| FAU→EDI | Conventional | 6 h | 60 | [6] |

| FAU→Na-ANA | Conventional & MC | 2 h | 110 | [15] |

| FAU→Cs-ANA | Conventional & MC | 2 h | 110 | [15] |

| FAU→MER | Conventional & MC | 2 h | 110 | [15] |

| FAU→ANA | Conventional & MC | 2 h | 110 | [15] |

| FAU→CAN | Conventional & MC | 2 h | 110 | [15] |

| FAU→Kalsilite* | Microwave | 10 min | 160 | This work |

| FAU→MER | Microwave | 5 min | 150-170 | This work |

| FAU→Cs-ANA | Microwave | 10 min | 160 | This work |

| FAU→EDI | Microwave | 5 min | 160 | This work |

| FAU→CAN | Microwave | 10 min | 160 | This work |

| Parent Phase | Temperature (°C) | rpm | KOH/FAU | H₂O/KOH | Time | Daughter Phase/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAU | 60 | 10 | 8.94 | 0.87 | 3 h | am |

| FAU | 60 | 600 | 8.94 | 0.87 | 6 h | am |

| FAU | 60 | 10 | 8.94 | 0.87 | 6 h | EDI |

| FAU | 60 | 10 | 8.94 | 0.87 | 22 h | EDI |

| FAU | 80 | 10 | 8.94 | 0.87 | 6 h | EDI |

| FAU | 80 | 10 | 8.94 | 0.87 | 22 h | KAlSiO4 |

| FAU | 80 | 600 | 8.94 | 0.87 | 10 min | am |

| FAU | 80 | 10 | 8.94 | 0.87 | 3 h | KAlSiO4 |

| FAU | 80 | 10 | 0.4 | 19.5 | 22 h | FAU, CHA |

| FAU | 80 | 10 | 8.94 | 0.87 | 1 h | EDI |

| FAU | 80* | 8.94 | 0.87 | 1 h | am | |

| FAU | 100 | 10 | 2 | 4.5 | 10 min | FAU |

| FAU | 100 | 20 | 0.62 | 12.6 | 11 h | CHA, GME, MER, NAT |

| FAU | 100 | 20 | 0.62 | 12.6 | 15 h | CHA, GIS, MER |

| FAU | 100 | 20 | 0.60 | 13 | 22 h | CHA, GME, MER |

| FAU | 120 | 10 | 8.94 | 0.87 | 6 h | KAlSiO4 |

| FAU | 120 | 10 | 2 | 4.5 | 10 min | FAU |

| FAU | 130 | 1200 | 2 | 4.5 | 10 min | FAU |

| FAU | 140 | 1200 | 2 | 4.5 | 10 min | FAU |

| FAU | 150 | 10 | 2 | 4.5 | 10 min | CHA, GME, GIS |

| FAU | 150 | 1200 | 2 | 4.5 | 5 min | MER |

| FAU | 160 | 10 | 1 | 4.5 | 5 min | CHA, GME, MER |

| FAU | 160 | 10 | 1 | 9 | 10 min | GME, GIS, AMI, CHA |

| FAU | 160 | 10 | 2 | 4.5 | 10 min | CHA, GME |

| FAU | 160 | 10 | 2a | 4.5 | 10 min | CAN |

| FAU | 160 | 10 | 8.94 | 0.87 | 10 min | KAlSiO4 |

| FAU | 160 | 1200 | 0.56 | 16.1 | 10 min | ANA, GIS |

| FAU | 160 | 1200 | 0.6 | 15 | 1 h | MER |

| FAU | 160 | 1200 | 0.7 | 4.5 | 10 min | MER |

| FAU | 160 | 1200 | 1 | 4.5 | 10 min | MER |

| FAU | 160 | 1200 | 1.42b | 4.9 | 10 min | Cs-ANA |

| FAU | 160 | 1200 | 2 | 1 | 10 min | KAlSiO4 |

| FAU | 160 | 1200 | 2 | 2 | 5 min | EDI |

| FAU | 160 | 1200 | 2 | 2 | 10 min | EDI |

| FAU | 160 | 1200 | 2 | 3 | 10 min | EDI, GIS |

| FAU | 160 | 1200 | 2 | 4 | 10 min | EDI, GIS, PHI |

| FAU | 160 | 1200 | 2 | 4.5 | 1 min | FAU |

| FAU | 160 | 1200 | 2 | 4.5 | 5 min | CHA, GME |

| FAU | 160 | 1200 | 2 | 4.5 | 10 min | CHA, MER |

| FAU | 160 | 1200 | 2 | 5 | 10 min | GIS, PHI, MER |

| FAU | 170 | 10 | 2 | 4.5 | 10 min | PHI, MER, NAT, Na₂Si₄O₉ |

| FAU | 170 | 20 | 2.7b | 2.59 | 1 h | ANA |

| FAU | 170 | 1200 | 2 | 4.5 | 10 min | MER |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).