6.1. Modular Derivatives on the Real line

As indicated in

Section 1, the derivatives can be generalized in different directions. If locality is the leading requirement, then the most natural way for such generalization is to replace the assumption of local Lipschitz growth with the more general modular-bound growth.

Definition 16 (Modulus of continuity). A point-wise modulus of continuity of a function is a

- 1.

non-decreasing, non-constant continuous function, such that

- 2.

and

- 3.

holds in the interval for some constant K.

A regular modulus is such that .

In the subsequent sections we will assume that all considered moduli are regular. The following definition of a modular function is adopted to avoid singular moduli.

Definition 17. A modular function is a regular modulus of continuity, which is also differentiable everywhere in for certain .

Note that the dependence on the point x of the modulus of continuity is suppressed in the above definition. By duality, one can denote the set as the set of points where g is the modulus of continuity of f. From practical point of view, mostly moduli comprising elementary functions are of interest.

Example 1. for is a modular function, which is not differentiable at . This modulus determines the Hölder growth class .

Example 2. Another non-trivial example is the function for is a modular function.

Definition 18.

Define the parameterized difference operators as

for the variable and the function . The two operators are referred to as forward difference and backward difference operators, respectively.

Definition 19.

Define g-variation operators as

for a positive ϵ and a regular modular function g.

Define the modular derivative as:

Definition 20 (Modular derivative, g-derivative).

Consider an interval and define the limit if it exists

for a modulus of continuity . The limit will be understood in topological sense (e.g., Def. 15). The last limit will be called modular derivative with regard to the function g or g-derivative.

NB! Equality of and is not required.

At this point it can be observed that the above definition is not vacuous since for a non-singular function of bounded variation on an interval

by L’Hôpital’s rule. In this regard it is useful to consider the following result:

Proposition 5. Suppose that at x and , where g is a modular function. Then =0.

Proof. By L’Hôpital’s rule

since differentiability of

f implies continuity of the derivative at x. □

Definition 21.

Consider a function f continuous on the closed interval I. The set

is called the set of change.

By this definition the geometrical meaning of the sets becomes clear as the sets of points where the function f can be optimally approximated by a right, respectively left, modular function g.

Remark 3. Together with the L’Hôpital’s rule this proposition can be used in practice for computations of g-derivatives. For suitable types of functions the process can be automated and implemented in computer algebra systems.

6.2. Topology Induced by the Set of Change

This section characterizes the topology induced by a modular function g. To this end we use the notion of the set of change .

Definition 22.

Consider the infinite bounded sequence . Let , , where and/or are not necessarily in . Define the Cauchy operator

The sequences, for which , will be called Cauchy-complete.

Definition 23 (Closure twist map).

Define the closure defect map as the set-valued map

Lemma 3. The operator satisfies axioms K1 – K3 for any sequence . If then satisfies also K4 for the sequences A and B.

Proof. Axiom K1 is satisfied vacuously since .

Axiom K2 is satisfied since .

. However, and

. Therefore, so that Axiom K3 is satisfied.

Axiom K4 is satisfied only for a certain type of sequences. Let

. Observe that

and

. Then

On the other hand,

Therefore,

since for finite sets

min coincides with

inf and

max coincides with

sup, respectively. Therefore, if

the K4 holds. □

From the above we can see that the is a closure operator for a fixed sequence.

Proposition 6. Suppose that then the axiom K4 holds for and .

Proof. We need to demonstrate that

Observe that

Also

Therefore,

. On the other hand,

. Therefore,

□

Theorem 2 (Induced topology). Let A be a bounded sequence. Then and are topological spaces and is a closure operator for them. Every set is closed. This topology is denoted by .

Proof. By Lemma 3 and Proposition 6 K1 – K4 are satisfied. K5 is satisfied since . Therefore, is a space. Furthermore, by idempotence is a space.

For the second part, let then the boundary is . By idempotence . Therefore, the set X is closed. □

Remark 4. The term Cauchy complete is justified by the observation that for a Cauchy sequence A the set can have only 3 values or ∅ depending on whether A has a minimum, a maximum or both.

In the next paragraphs we give a more conventional treatment of so-identified topology. In the conventional approach, the topology

, induced by

, can be characterized by the open sets

The points in the topological space

then are the singletons

. Therefore, this topology can be recognized as the co-finite topology of the infinite (!) set

A. Furthermore, one can claim that

Proposition 7. The sets form a basis in the topology .

Proof. To prove the statement we need to verify two properties:

(1) Every point lies in some set .

(2) For each pair of sets and each point there exists a set such that . Property 1 holds as . Property 2 holds for , such that . Under this hypothesis and for . □

Having established the appropriate topological background, we are ready to relax the definition of

by requiring only that the limit

exists in the topological sense of Definition 15. If said limit exists we write as above

.

Theorem 3 (Topological continuity of g-derivatives). Suppose that is an infinite set inducing a topology . Suppose that S is dense in . Then the images are continuous on S under .

Proof. Suppose that S is dense in . Since S is dense in it is Cauchy-complete, which implies that .

Let further , where exists finitely. Since is finite, the action of is defined . Therefore we can write . . Therefore, and by the Hausdorff Theorem is continuous on S. □

Note that the last result does not imply continuity of

in the usual topology of

. In contrast, strictly sub-additive modules give rise to g-derivatives, which are discontinuous in the usual topology [

23]. We further specialize the argument to Hölder-continuous functions where

,

. The g-derivative in this case specializes to fractional velocity denoted by

. There are two composition formulas that are useful for the subsequent discussion and examples:

and

for a composition of

function

f with a differentiable function

h evaluated at the argument

x, depending on the order of the functions in the composition. We give some examples of singular function which have for sets of change a countable subset of the Cantor set; the dyadic rationals

; and the rational numbers

.

The Cantor set is the prototypical example of a totally disconnected, uncountable, perfect set. The set gives rise to the eponymical singular function.

Example 3 (Cantor singular function).

On , Cantor’s singular function is the unique solution of the functional equation

with fixed points , .

Cantor’s function can be approximated by a possibly non-terminating iterative algorithm from the discrete floor map as follows:

From the above system it is apparent that the set of increase of the Cantor’s function is a countable subset of Cantor’s ternary set (and hence of measure zero). That is, we have

natural numbers. To calculate the fractional velocity on the co-fininte topology of the Cantor set we select a sequence, such that . Such a sequence is . Let

By the functional Equation (12) the following identity holds: ; so that . Therefore,

Therefore, . By the functional Equation (12) , therefore

Then

so that On the other hand, .

We can formally adjoin to respect the functional equation. Therefore, we obtain the functional equation system

as prescribed by formal g-differentiation of the functional equations.

Another interesting example is the De Rham’s singular function, which was also rediscovered by Takacs in a different context [

30]. The function depends on a real-valued parameter

and has for a set of change the dyadic rationals

and is constant almost everywhere in

.

Example 4 (De Rham-Takacs singular function).

In 1978 Takacs [30] introduced a new singular function defined in the unit interval, such that for a number

where the sequence is increasing, the function is defined as

where , .

If we consider the usual binary representation

for and restrict the discussion the dyadic rationals , which are dense in , we can establish the following. Suppose that . Then,

On the other hand,

Therefore, .

For let

as above. By a simple re-indexing of the number

observe that

Therefore,

if we set . On the other hand, for

the function evaluates to

Therefore,

To summarize,

This corresponds to the functional equation of the De Rham’s function since one can identify [31].

To compute the fractional velocity on the dyadic rationals we can formally g-differentiate the system as

Therefore, for the fractional velocity to be finite either

or

>

should hold. Suppose that then the maximal Hölder exponent is

At this point the direction of differentiation should be fixed in a way consistent with a direct calculation. We calculate . Suppose that

by induction for . Therefore, for

Therefore,

where also .

Conversely, if then the maximal Hölder exponent is

We calculate as

Therefore, and

where now holds.

A third interesting example is the Neidinger function called also the

fair-bold gambling function [

32]. The function is based on De Rham’s construction and is also constant almost everywhere in

.

Example 5 (Neidinger singular function).

Consider the iterated function system (IFS) for , which swaps the value of parameter at every step of the iteration:

starting from . Define the Neidinger’s function as the limit

The fractional velocity of the function has been exhibited in [19]. Here we work on the dyadic rationals . Formal g-differentiation of the defining IFS without regard to the parameter swapping rule results in

The actual computation can be carried out in the following way. Starting from define recursively the auxiliary IFS

Therefore, either or must hold for the IFS to converge. The maximal Hölder exponent is then

Consider the case when . Then

In a similar way, whenever we have

Therefore, in the general case we have

From the presented calculation we see that the set of change of the Neidinger function are the dyadic rationals.

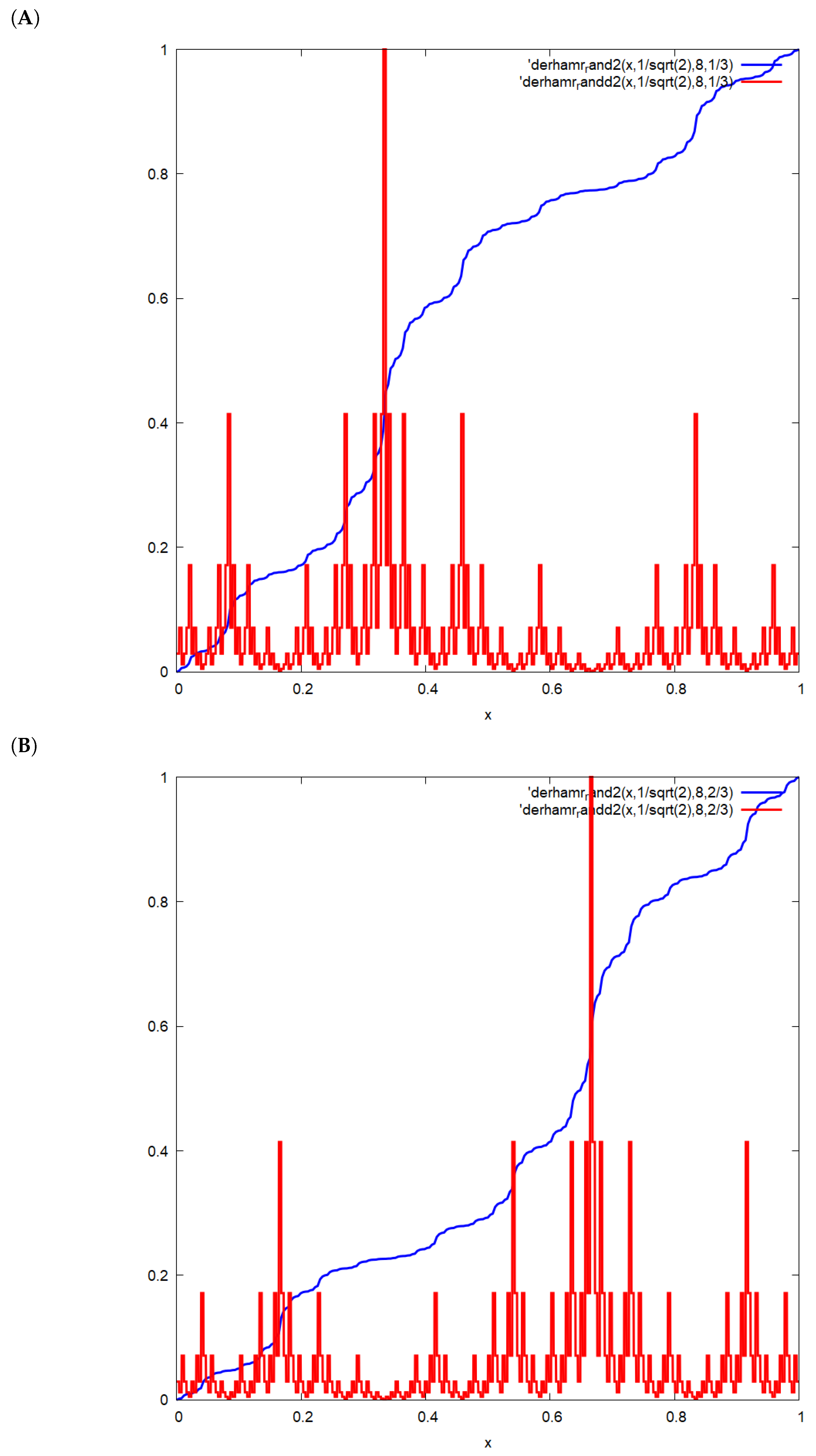

Plotting of the graph of the fractional velocity is challenging due to the fact that it does not vanish only on a null set in any given interval. Therefore, one could only plot the covering graph approximating the fractional velocity at certain iteration order. This can be done by defining recursively an IFS that in limit converges point-wise to the fractional velocity of the given singular function.

The construction of the Neidinger function can be generalized using the Bernoulli map. The result is another singular function, which we can call tentatively De Rham-Bernoulli function. The construction can be carried out as follows.

Example 6 (De Rham-Bernoulli singular function).

Suppose that . Starting from define , where evaluates to either 0 or 1. Define the auxiliary function

where z is computed as above.

Finally, starting from define the IFS

Then

Observe that the limit exists since . Indeed, suppose that . Then

By symmetry, the same estimate holds also whenever . Therefore, the IFS will converge point-wise to a limit.

The fractional velocity of the above function can be computed in a similar way as above setting . The IFS in this case is

starting from . Then in order for the IFS to converge the maximal Hölder exponent is

and the IFS transforms as

Note that the form of the IFS is identical to the one in the previous example. Finally,

A plot of the Neidinger-Bernoulli function and its fractional variation at iteration level

is presented in

Figure 1.