1. Introduction

Researchers are increasingly interested in finding new alternative methods of combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria, including the use of phage therapy (PT) [1-3]. Bacteriophages may interact with the immune system, which may affect the induction of antiphage antibodies in both animals and humans, but their clinical significance is unclear [4-9]. Antiphage antibodies can neutralize phage activity, which may reduce the ability of phages to destroy bacteria.

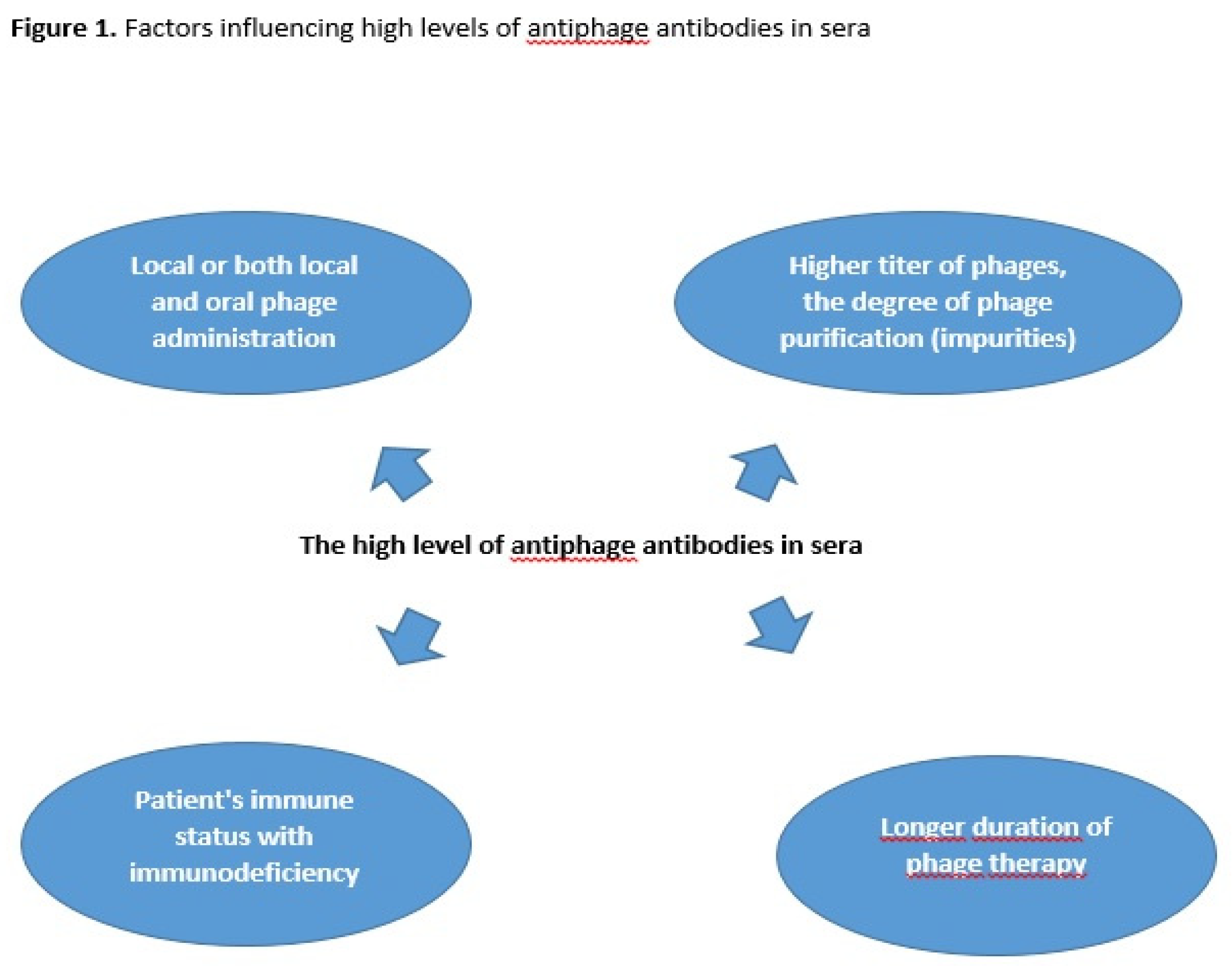

Our previous studies have shown that the level of antiphage activity of sera (AAS) calculated as the rate of phage inactivation (K) in patients undergoing phage therpy (PT) depends on several factors such as the route of phage administration, phage type and the dose of the phage preparation (

Figure 1) [

7,

8]. Oral and rectal administration of phages are considered the least immunogenic, whereas local and both local and oral administration are more immunogenic. Purified phage preparations with higher titer of phages may be more immunogenic in comparison to phage lysates [

8]. The influence of a higher phage titer on a higher antibody level is not a rule, and the degree of preparation purification may also be important. Żaczek et al. [

9] showed that sometimes lysates are more immunogenic (despite lower titers) than purified preparations, which was explained by the influence of impurities on the higher antibody level result. Antibody responses to phage administration may also depend on the patient's immune status, which is clinically relevant as approximately 50% of them are immunodeficient. We observed that the frequency of high levels of AAS during PT depends on the type of phage preparation (monovalent phage or phage cocktail) [

10]. Moreover, the positive correlation was indicated between the level of IgG and IgM antiphage antibodies and the K rate in sera of patients treated with phages [

9]. We demonstrated that the level of AAS is not correlated with the outcome of PT [

7,

8].

Nick et al. [

11] and Le et al. [

12] confirmed our observations. The authors revealed that clinical improvement in PT was observed in case of lung or urinary tract infection despite an antiphage antibody response.

The aim of the current study is to determine when the earliest high levels of AAS arise during local and both local and oral PT of bone infections, soft tissue infections or upper respiratory tract infections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

27 patients with bacterial infections such as bone infections, soft tissue infections or upper respiratory tract infections underwent PT between 2017 and 2023 at the Phage Therapy Unit (PTU) of Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy (HIIET). The patients were administered with monovalent phage lysate

Staphylococcus aureus Staph_1N or Staph_A5L (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Bacteriophage preparations were from the Laboratory of Bacteriophages (HIIET) Wrocław. Phage lysates were prepared according to the procedure described in Żaczek et al. [

9]. Titer of phage preparations varied between 10

6 and 10

8 plaque forming unit/mL (pfu/mL). Lytic phages were selected for treatment on the basis of phage typing procedure. Phages were used locally (

Table 1) or both locally and orally (

Table 2) according to the protocol "Experimental phage therapy of drug-resistant bacterial infections, including MRSA infections” [

13]. The local phage administration was performed two- to three- times daily (compress, fistula irrigation, spraying onto the skin, spraying wound, nasal spray, sinus irrigation). The oral phage administration was performed in the dose of 10 ml phage preparation two- to three- times daily, at least 30 min before meals. About 10 ml of suspension of dihydroxyaluminium sodium carbonate (68 mg/ml) was applied up to 20 min before a phage application to prevent phage inactivation by gastric juice.

The Blood was collected before, during and after PT. As previously described, patients underwent phage therapy (PT) according to the established experimental therapy protocol, and the number of visits ranged from 1 to 11 depending on the course of therapy [

9]. Despite our efforts, it was impossible to collect samples according to clinical trial protocols. The blood was centrifuged at 1500× g for 10 min and separated sera samples were stored at − 70 °C. AAS was performed immediately after obtaining sera samples. The AAS studies were performed in line with the approval of the Bioethics Committee of the Wrocław Medical University (Poland). All patients gave written informed consent to participate in these studies.

2.2. Bacteriophages

Staphylococcus aureus bacteriophages vB_SauH_A5L18349 and vB_SauH_1N/80 from the Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy, Polish Academy of Sciences phage collection, were used in the study. Both phages represent polyvalent, obligatory lytic phages from serological group D (with 93%- 99.8% genome homology inside the group). According to ICTV taxonomy, they belong to the family

Herelleviridae, subfamily Twortvirinae, and genus

Kyavirus G1. Their genomes consist of double-stranded DNA, and they do not exhibit the ability to package foreign DNA into the virione. Additionally, they do not encode any homologues of known virulence factors or determinants of antibiotic resistance [

14]. These phages demonstrate a broad host range and lytic spectrum, with effectiveness against 73% - 84% of tested strains.

2.3. Plate Phage Neutralization Test

The AAS level of patients undergoing PT was calculated using the plate phage neutralization test as described earlier [

8,

15]. Briefly, the phage was used at a concentration of 1 × 10

6 pfu/mL and the sera samples were diluted from 1:10 up to 1:1500. 50 μL of phage was mixed with an undiluted serum and with each of the serum dilutions (450 μL). The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After incubation, the mixture was diluted 100-fold with cold-enriched broth (5.4 g of enzymatic hydrolysate of casein, 4 g of Bacto Pepton, 3.5 g of NaCl, 1.7 g of yeast extract, 0.4 g of beef extract and 1000 ml of distilled water). The phage titer was determined by the double-agar layer method described by Adams [

16]. 100 μL of the mixture and 200 μL of bacterial culture were added to 3 mL of semi-liquid agar (0.7%) at 45°C and the mixture was flowed out on the agar plate. After 8 hours of incubation at 37°C, plaques were detected. AAS was assessed as the rate of phage inactivation K (K = 2.3 x (D / T) x log (P0 / Pt), where D is the reciprocal of the serum dilution, T is the phage-serum reaction time (30 min.), P0 is the phage titer at the beginning of the phage-serum reaction and Pt is the phage titer after time T of the phage-serum reaction). A K rate of less than 5 was determined as a low level of phage inactivation, a K of between 5 and 18 as a medium level of phage inactivation and above 18 as a high level of phage inactivation.

2.4. Categories of the Results of PT

The outcome of PT was described according to Międzybrodzki et al. [

13].

Categories A–C were assigned as positive responses to PT.

A – pathogen eradication and/or recovery (eradication confirmed by the results of bacterial cultures; recovery refers to wound healing or complete subsidence of the infection symptoms),

B – good clinical result (almost complete subsidence of some infection symptoms, together with significant improvement in the patient’s general condition after completion of PT),

C – clinical improvement (discernible reduction in the intensity of some infection symptoms after completion of PT to a degree not observed before PT, when no treatment was used).

Categories D–G were assigned as inadequate responses to PT.

D – questionable clinical improvement (reduction in the intensity of some infection symptoms to a degree that could also be observed before PT),

E – transient clinical improvement (reduction in the intensity of some infection symptoms observed only during application of phage preparations and not after termination of PT),

F – no response to treatment (lack of reduction in the intensity of some infection symptoms observed before PT),

G – clinical deterioration (exacerbation of symptoms of infection at the end of PT).

3. Results

27 patients with bone infections, soft tissue infections or upper respiratory tract infections were treated either locally (

Table 1) or both locally and orally (

Table 2) with

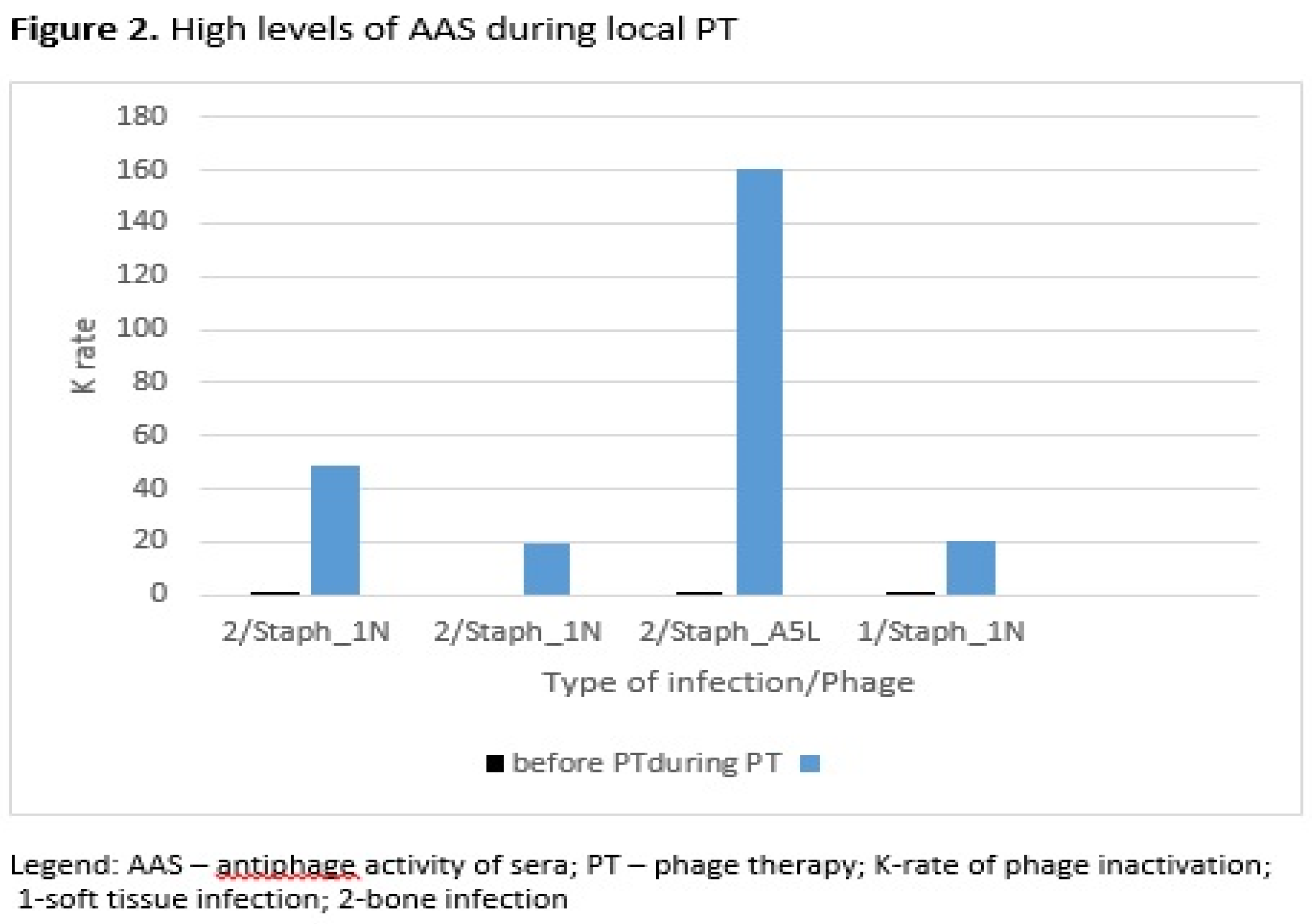

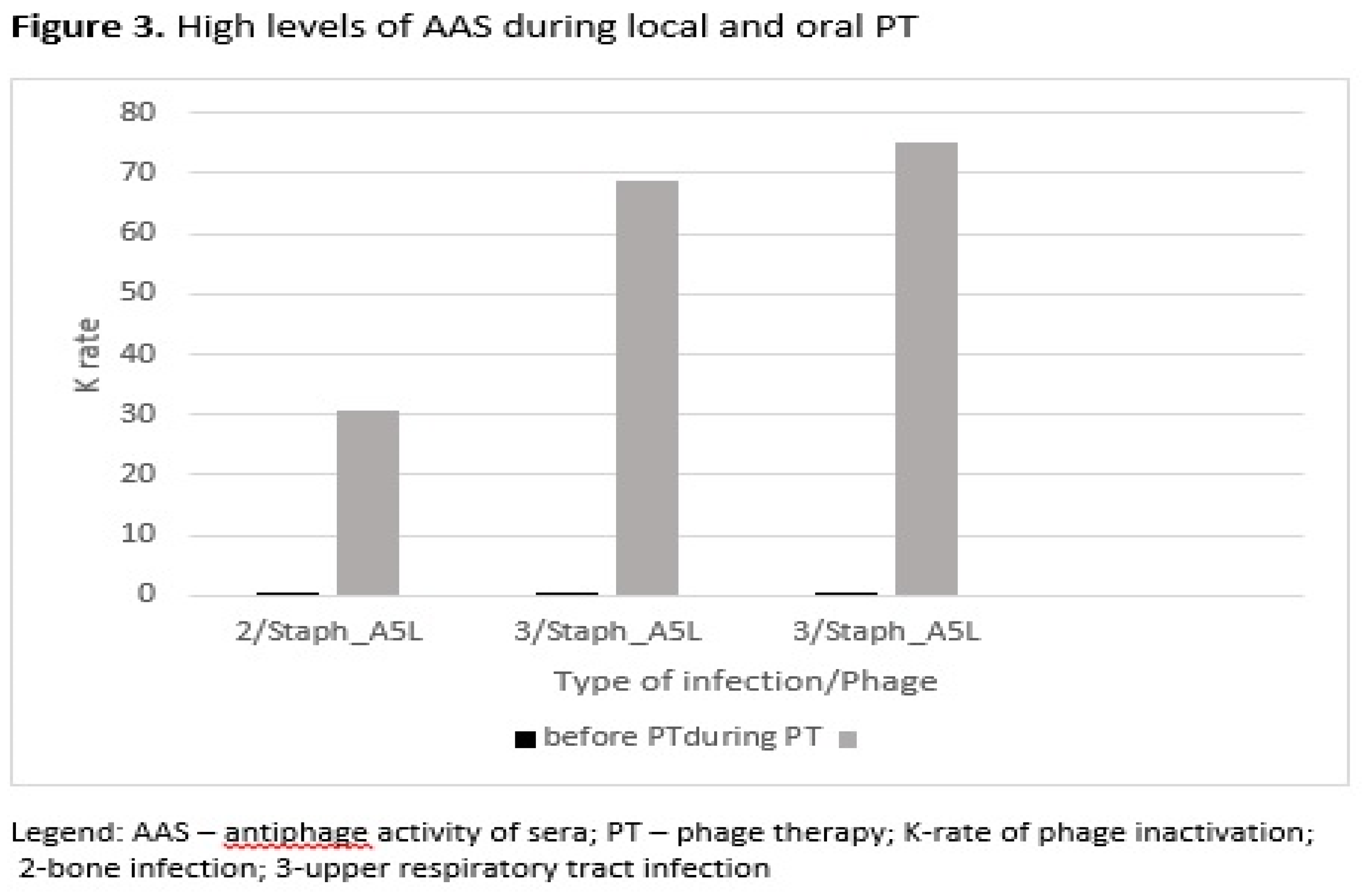

Staphylococcus aureus phages Staph_1N or Staph_A5L. Patients underwent phage therapy (PT) until week 8 after the administration of first dose. Prior to the PT patients had low rates of phage inactivation (K=0.00-0.52) in sera. After 2-2.5 weeks of PT administered locally patients had low K =0.29-0.67, whereas in weeks 3-8 their K was classified as low or high with values up to K=160.08 in sera (

Table 1). After 2-2.5 weeks of PT applied locally and orally patients had low K =0.10-2.59, whereas in weeks 3-8 their sera samples yielded low or high K up to K=75.12 (

Table 2). The earliest time of appearance of high levels of antiphage antibodies in sera was observed in weeks 3-8 of PT.

High levels of AAS during local PT were detected in three patients with bone infection and in one patient with soft tissue infection (

Figure 2). Three patients in this group of patients used

S. aureus phage Staph_1N, and one patient used

S. aureus phage Staph_A5L. In the second group of patients who used phages locally and orally, high levels of AAS were detected in one patient with bone infection and in two patients with upper respiratory tract infection (

Figure 3). All patients in this group were administered

with S. aureus phage Staph_A5L.

Twice as few patients had K>18 during or after local and oral treatment (25%) than those treated only locally (45.4%), which may be the result of a different route of phage administration to patients, type of infection and phage type. As for the treatment outcome, 27.3% of patients treated locally with phages had positive clinical response to PT (A-C). Higher percent of positive outcome of PT 43.7% (A-C) was observed in patients treated with phages both locally and orally.

4. Discussion

The above-mentioned studies confirm our previous findings [

7,

8], which are of high importance for phage therapy: the idea that bacteriophages are neutralized during PT and that the level of antiphage antibodies does not affect the result of PT, which is still very poorly understood. Recent studies from 2022 by Nick et al. [

11] and from 2023 by Le et al. [

12] confirm the lack of influence of a strong antiphage antibody response in sera during PT, in lung or urinary tract infection, on the outcome of PT.

In this article the time of occurrence of high K level in sera, in local and both local and oral PT was compared. The same staphylococcal phages (two types of phages Staph_1N or Staph_A5L) were used in bone infections, soft tissue infections or upper respiratory tract infections. Similarly, to local PT in both local and oral PT high K levels in sera occurred at the earliest in the weeks 3-8 of PT. The higher number of patients with K>18 during or after local PT vs. local and oral PT may also be a result of the type of infection with bone infection and use of the S. aureus phage Staph_1N. Our studies also indicated a positive clinical response in some patients with high AAS during or after local PT in soft tissue infection and bone infection, who used S. aureus phage Staph_1N. Also, a clinical improvement was observed during local and oral PT in a patient with high AAS with bone infection who used S. aureus phage Staph_A5L.

In studies of Le et al. [

12] in case of urinary infection partial sera inactivation of two

Klebsiella phages out of 3 from phage cocktail was observed in the 1st week during intravenous phage administration. Phage therapy was conducted for 4 weeks without concomitant use of antibiotics. Higher level of phage inactivation in the serum was observed at 8 day versus 15 day. The reason of this phenomenon is unclear. Other studies of Nick et al. [

11] focusing on lung infections demonstrated that the level of antiphage antibody in the serum to one mycobacteriophage out of 2 from phage cocktail increased with time. Gradual increase of neutralization was observed from 3 to 500 days post-phage treatment administered intravenously with substantial inactivation after 242 days. The study indicated that the appearance of high levels of antiphage antibody in the late phage treatment does not exclude the positive results of PT. Studies by Dan et al. also reported that the robust phage-specific immune response did not prevent clinical treatment success, as evidenced by the absence of pneumonia and microbiological tests [

17]. A multidrug-resistant

Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a lung transplant recipient was treated with adjunctive intravenous and inhaled PT. A patient was administered with two phage cocktails AB-PA01 and its modified version AB-PA01-m1, as well as the United States Navy antipseudomonal phage cocktail successively until day 92. Neutralizing antibodies for two phage cocktails peaked at days 63 and 70.

However a limited phage therapeutic efficacy was observed in a case of a pulmonary

Mycobacterium abscessus infection with the antibody response to phage [

18]. A patient with refractory lung disease was treated intravenously for six months with a three-phage cocktail. After two months high levels of IgM and IgG neutralizing antibodies to phages were associated with clinical deterioration. An increase in the number of bacteria in sputum was detected.

Dedrick et al. presented the results of aerosolized phage therapy in a patient with refractory

Mycobacterium abscessus lung disease. Intravenous cocktails composed of three mycobacteriophages were administered over a six-month period, alongside a dedicated antibiotic regimen [

19]. A transient decline in the

Mycobacterium abscessus burden, followed by a rebound in mycobacterial colony-forming units, was observed. The authors reported no changes in the phage and antibiotic susceptibility of

Mycobacterium abscessus isolates after eight months of nebulization. However, there was no substantial clinical effectiveness noted after six months of twice-daily intravenous and nebulized phage treatment. The study provides valuable insights into the interaction between phages and the immune system, particularly the role of IgA in sputum. While initial phage administration may face challenges due to weak neutralization by IgA, the potential for an enhanced immune response over time suggests that phage therapy could still be a viable treatment option, especially with individualized approaches that consider the unique immune responses of patients. Further research and clinical trials are warranted to optimize phage therapy protocols for mycobacterial infections.

Our previous studies have shown an increase in the level of IgM and IgG antiphage antibodies in sera of some patients with bone infections treated locally with staphylococcal MS-1 phage cocktail, while the level of IgA antiphage antibodies in sera was low [

9]. The authors observed two exceptions in this group of patients where IgA levels in sera were elevated. It is possible that higher levels of IgA antiphage antibodies could be detected in saliva instead of serum.

5. Conclusions

In some patients high levels of antiphage antibodies in sera may appear as early as in the 3rd-8th week of PT. This is especially visible during local or both local and oral therapy in bone infections, soft tissue infections or upper respiratory tract infections. This phenomenon does not weaken the outcome of PT. Additionally, we observed that the high level of AAS during local PT was correlated with the type of infection and phage type, especially with bone infection and treatment with the S. aureus phage Staph_1N. Whereas, the high level of AAS during local and oral PT was observed especially in upper respiratory tract infection with use of the S. aureus phage Staph_A5L. The studies should be used to monitor the occurrence of neutralizing antiphage antibodies in patients undergoing PT. It is also important to develop studies to determine the level of IgM, IgG and IgA antiphage antibodies in the sera of patients using PT. Further research is necessary to explain antibody production during PT in more depth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Ł.-S. and A.G.; methodology, M.Ł.-S.; formal analysis, M.Ł.-S., B.W.-D., M.Ż. and R.M.; investigation, M.Ł.-S.; conducting phage therapy, R.M.; resources, M.Ł.-S. and A.G.; writing-original draft preparation, M.Ł.-S., B.W.-D. and A.G.; writing-review & editing, M.Ł.-S., M.Ż. and A.G.; supervision, A.G., M.Ł.-S. and B.W.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by institutional funds from the Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Bioethics Committee of the Wrocław Medical University (Poland) (protocol title “Phage inactivation by sera from patients with bacterial infections undergoing phage therapy and healthy subjects”, protocol code KB-414/2014, date of approval 24.06.2014; protocol code KB-411/2017, date of approval 13.06.2017; protocol code KB-504/2020, date of approval 14.09.2020) for studies involving humans. Phage therapy was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Bioethics Committee of the Wroclaw Medical University (title of the therapeutic experiment project “Experimental phage therapy of antibiotic therapy-resistant infections, including MRSA infections”, approval No. KB-349/2005) on 15 June 2005.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are derived from personal patients’ medical records maintained at the Phage Therapy Unit of the Medical Centre as well as Bacteriophage Laboratory of the Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy Polish Academy of Sciences in Wrocław, Poland. Those data are not publicly available due to privacy and legal issues (The General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 and Act on the rights of the patient and the Patient’s Rights Ombudsman from 6 November 2008).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by statutory funds from the Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

Conflicts of Interest

B.W.-D., R.M. and A.G. are co-inventors of patents owned by the Institute and covering phage preparations. Other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Górski, A.; Międzybrodzki R.; Węgrzyn, G.; Jończyk-Matysiak, E.; Borysowski, J.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B. Phage therapy: Current status and perspectives. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40(1), 459-463. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Wang, C.; Zhou, X.; Guo, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhao, R.; Song H. Bacteriophage therapy for drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1336821. [CrossRef]

- Olawade, D.B.; Fapohunda, O.; Egbon, E.; Ebiesuwa, O.A.; Usman, S.O.; Faronbi, A.O.; Fidelis, S.C. Phage therapy: A targeted approach to overcoming antibiotic resistance. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 197, 107088. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowska, K.; Miernikiewicz, P.; Piotrowicz, A.; Hodyra, K.; Owczarek, B.; Lecion, D.; Kaźmierczak, Z.; Letarov, A.; Górski A. Immunogenicity studies of proteins forming the T4 phage head surface. J. Virol. 2014, 88(21), 12551-7. [CrossRef]

- Gembara, K.; Dąbrowska, K. Interaction of bacteriophages with the immune system: induction of bacteriophage-specific antibodies. Methods Mol. Biol. 2024, 2734, 183-196. [CrossRef]

- Majewska, J.; Kaźmierczak, Z.; Lahutta, K.; Lecion, D.; Szymczak, A.; Miernikiewicz, P.; Drapała, J.; Harhala, M.; Marek-Bukowiec, K.; Jędruchniewicz, N.; Owczarek, B.; Górski, A.; Dąbrowska, K. Induction of phage-specific antibodies by two therapeutic staphylococcal bacteriophages administered per os. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2607. [CrossRef]

- Łusiak-Szelachowska, M.; Żaczek, M.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B.; Międzybrodzki, R.; Kłak, M.; Fortuna, W.; Letkiewicz S., Rogóż P., Szufnarowski K., Jończyk-Matysiak E., Owczarek, B.; Górski, A. Phage neutralization by sera of patients receiving phage therapy. Viral Immunol. 2014, 27, 295-304. [CrossRef]

- Łusiak-Szelachowska, M.; Żaczek, M.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B.; Międzybrodzki, R.; Letkiewicz, S.; Fortuna, W.; Rogóż, P.; Szufnarowski, K.; Jończyk-Matysiak, E.; Olchawa, E.; Walaszek, K. M.; Górski, A. Antiphage activity of sera during phage therapy in relation to its outcome. Future Microbiol. 2017, 12, 109-117. [CrossRef]

- Żaczek, M.; Łusiak-Szelachowska, M.; Jończyk-Matysiak, E.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B.; Międzybrodzki, R.; Owczarek, B.; Kopciuch, A.; Fortuna, W.; Rogóż, P.; Górski A. Antibody production in response to staphylococcal MS-1 phage cocktail in patients undergoing phage therapy. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1681. [CrossRef]

- Łusiak-Szelachowska, M.; Żaczek, M.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B.; Kłak, M.; Międzybrodzki, R.; Fortuna, W.; Rogóż, P.; Szufnarowski, K.; Jończyk-Matysiak, E.; Górski A. Antiphage activity of sera from patients receiving staphylococcal phage preparations. In: Microbes in the spotlight: recent progress in the understanding of beneficial and harmful microorganisms; Méndez-Vilas A., Eds; BrownWalker Press, 2016; pp. 245-249.

- Nick, JA.; Dedrick, R.M.; Gray, A.L.; Vladar, E.K.; Smith, B.E.; Freeman, K.G.; Malcolm, K.C.; Epperson, L.E.; Hasan, N.A.; Hendrix, J.; Callahan, K.; Walton, K.; Vestal, B.; Wheeler, E.; Rysavy, N.M.; Poch, K.; Caceres, S.; Lovell, V.K.; Hisert, K.B.; de Moura, V.C.; Chatterjee, D.; De, P.; Weakly, N.; Martiniano, S.L.; Lynch, D.A.; Daley, C.L.; Strong, M.; Jia, F.; Hatfull, G.F.; Davidson, R.M. Host and pathogen response to bacteriophage engineered against Mycobacterium abscessus lung infection. Cell. 2022, 185(11), 1860-1874.e12. [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Nang, S.C.; Zhao, J.; Yu, H. H.; Li, J.; Gill, J. J.; Liu, M.; Aslam, S. Therapeutic potential of intravenous phage as standalone therapy for recurrent drug-resistant urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2023, 67(4), e0003723. [CrossRef]

- Międzybrodzki, R.; Borysowski, J.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B.; Fortuna, W.; Letkiewicz, S.; Szufnarowski, K.; Pawełczyk, Z.; Rogóż, P.; Kłak, M.; Wojtasik, E.; Górski, A. Clinical aspects of phage therapy. Adv. Virus Res. 2012, 83, 73-121. [CrossRef]

- Łobocka, M.; Hejnowicz, M.S.; Dąbrowski, K.; Gozdek, A.; Kosakowski, J.; Witkowska, M.; Ulatowska, M.I.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B.; Kwiatek, M.; Parasion, S.; Gawor, J.; Kosowska, H.; Głowacka, A. Genomics of staphylococcal Twort-like phages--potential therapeutics of the post-antibiotic era. Adv. Virus Res. 2012, 83, 143-216. [CrossRef]

- Pescovitz, M.D.; Torgerson, T.R.; Ochs, H.D.; Ocheltree. E.; McGee, P.; Krause-Steinrauf, H.; Lachin, J. M.; Canniff, J.; Greenbaum, C.; Herold, K. C.; Skyler, J. S.; Weinberg, A.; Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group. Effect of rituximab on human in vivo antibody immune responses. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128(6), 1295-1302. [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.H. Methods of study of bacterial viruses. In Bacteriophages; Adams, M.H., Eds.; Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1959; pp. 443–522.

- Dan, J.M.; Lehman, S.M.; Al-Kolla, R.; Penziner, S.; Afshar, K.; Yung, G.; Golts, E.; Law, N.; Logan, C.; Kovach, Z.; Mearns, G.; Schooley, R.T.; Aslam, S.; Crotty, S. Development of host immune response to bacteriophage in a lung transplant recipient on adjunctive phage therapy for a multidrug-resistant pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 227(3), 311-316. [CrossRef]

- Dedrick, R.M.; Freeman, K.G.; Nguyen, J.A.; Bahadirli-Talbott, A.; Smith, B.E.; Wu, A.E.; Ong, A.S.; Lin, C.T.; Ruppel, L.C.; Parrish, N.M.; Hatfull, G.F.; Cohen, K.A. Potent antibody-mediated neutralization limits bacteriophage treatment of a pulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus infection. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1357–1361. [CrossRef]

- Dedrick, R.M.; Freeman, K.G.; Nguyen, J.A.; Bahadirli-Talbott, A.; Cardin, M.E.; Cristinziano, M.; Smith, B.E.; Jeong, S.; Ignatius, E.H.; Lin, C.T.; Cohen, K.A.; Hatfull, G.F. Nebulized bacteriophage in a patient with refractory Mycobacterium abscessus lung disease. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9(7), ofac194. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).