1. Introduction

1.1. Media Agenda

Much has been written about the relationship between the political agenda of social movements and the agenda of hegemonic media and their role in preserving the status quo; even about the antagonism of both agendas and how, over time, the contents of activism tend to prevail (Candón, 2012).

Although agenda theories (Lippman, 1922; McCombs & Shaw, 1972; Roberts, 1972; Weaver, Graber, McCombs & Eyal, 1981; Dearing & Rogers, 1992; Aruguete, 2016; Zunino, 2018; Ardèvol-Abreu, Gil de Zuñiga & McCombs, 2020) imply, on the one hand, the different levels of accessibility that they have for the various social actors, they tend to explain more from hegemonic than counter-hegemonic rationalities. However, this should not be understood as a problem of the explanatory model, but rather of how it is applied, especially if we consider the reversal experiences we observe today, which account for how social movements relate to power and challenge it.

There is no doubt that the nature and character of information is at the heart of the debate on the agenda. However, if we consider information as a social good, it is a right of citizens; if instead it is considered a consumer good, it becomes a right of the media. Here lies the main difference between the conception of freedom of expression and that of the right to communication. In the first case, it is about information as a private good and in the second as a social good (Muleiro, 2006).

As commercial purposes prevail and operations are carried out with high levels of concentration, certain discourses, certain sources, and certain economic, political, and ideological interests predominate. The latter tends to contribute to a private media model, which is disputed in the advertising market.

1.2. New Agendas and Social Movements

Here we are interested not only in analyzing how social movements can access the agendas of traditional hegemonic media, when the latter -in some way- adjust to the new social realities because we observe a coincidence between the interests and values of social movements and the political and media interests and values of the elites (Gitlin, 1986).

We are interested in understanding what the characteristics of communicative interventions are (Obregón & Tufte, 2017), as well as knowing how it is possible to build new agendas with new media. These cases that we will see can be better explained from one of the most recent stages of agenda-setting research, agenda building, which is characterized by the relationships between the different actors and their mutual influence in the agenda-setting process (Zunino, 2018). Although, as Zunino (2018) argues, the protagonism of the public, for example through the widespread use of social networks, could affect the power of the agenda-setting hypotheses; it is important to consider that such activism - as we will see - occurs within the same journalistic system, although in a first phase it will be through intervention in traditional media and in a second moment the media system will be expanded by incorporating new media. These operations of setting an alternative agenda take place within the framework of a highly concentrated media system and, on the other hand, imply a strategic analysis of the journalistic and media system, specifically the weaknesses of journalistic routines and the sensitivities of the information input (the criteria of newsworthiness). There is no doubt that, at least, the canonical concept of agenda must be problematized (Zunino, 2018), in which case the analysis of new practices, new media, and complexities in relationships constitute a challenge for the field of communication.

While agenda building considers the process of news construction and the different elements that influence it, with emphasis even on collective construction and the role of spokespersons (Charron, 1998; Lang and Lang, 1981; Sheafer and Weimann, 2005; Sádaba, 2008), in the case of the construction of an agenda by social movements, it is particularly about analyzing the possibilities generated by the relationships between the media and the sources, articulations that even agenda building fails to explain sufficiently, so to explain some situations it is necessary to understand how certain voices of actors and sources can become agenda setters at a given time, that is, occupy spaces of enunciation that allow them privileged access to the media. The questions, however, are more complex, since they imply distinguishing, on the one hand, between the influence that the different media have and, on the other hand, the influence that the different social actors may have. If we grant a relevant role to these agenda-setting actors, we must ask ourselves whether we are talking about a predominance of the agenda of the public, who in certain particular circumstances also become decision-makers. If this is the case, we must explain how it is possible that they interrelate in certain socio-political situations and even merge, the agenda of the public (who become political actors in these circumstances and, therefore, some of them become agenda-setters), the political agenda (highly sensitive to the public, as voters) and the agenda of the media (whose structure, despite being highly concentrated, opens spaces for certain counter-hegemonic discourses that feed the conflictual nature of the news). Finally, we can ask ourselves whether, in this case, the explanatory model of agenda setting is operational or whether, on the contrary, we should look for other explanatory models.

The idea of an interest group agenda promoted to identify and address social problems through different new media that play a key role is certainly relevant (Zhu, 1992). Evidently, the media agenda is in permanent dispute, so that when some issues/problems emerge, others fall by the wayside (Dearing and Rogers, 1992; Zhu, 1992).

The idea of a Network Agenda Setting Model (NAS) also contributes to the explanation of the phenomena discussed here, specifically in the sense that new media can build connections between agendas to reach audiences (Guo, Vu & McCombs, 2012). Without a doubt, a dynamic understanding of the media and their agendas allows us to better explain the role of existing connections in the construction of new agendas. For example, the role that the network plays in the hands of social movements in accessing the media agenda is fundamental. This network manages in certain sociopolitical situations to force the hegemonic media to cover information about the movements and their protests (Candón, 2012). Although the relationship between the use of the network and access to the media agenda is not completely quantified, it is evident that social movements incorporate various agendas, such as the public, the media and the political-electoral agenda.

Of particular interest here is how an analysis of frames is currently related to an understanding of organized social movements; specifically because the latter mobilize their members towards collective actions with political ends. These are collective actions that are sustained over time, organized in a relatively structured way, and whose members not only have common interests but also have concrete strategies (Sádaba, 2008). In a similar sense, the idea of “civic osmosis” is used to highlight “the collective role of the media” (McCombs, 2012).

1.3. From Resistance to Offensive Strategy: Genealogy of a Movement

The Mapuche indigenous social movement has its origins in 1910, with the creation of the Caupolicán Society for the Defense of Araucanía. Since 1910 was the year of the Centenary of Chilean Independence, the Society set out to commemorate the movement.

In the 1920s, we find the Araucanian Federation and the holding of the First Araucanian Congress. In this case, a critical and at the same time dialoguing stance is evident. In the same direction, we found the initiative to create the Araucanian Corporation, whose purpose was to unite efforts. All of this was recorded in the press of the time (La Época, 1910a; La Época, 1910b; La Época, 1910c; El Diario Austral, 1938), as well as in the minutes of the movement's documents (Asamblea de Caciques del Sur y Dirigentes de Indios, 1961; Comisión Organizadora del Primer Congreso del Movimiento Netuaiñ Mapu, 1972).

However, from the mid-1980s, the indigenous movement assumed a more critical and demanding character, which coincided with the end of the dictatorship and the beginning of the government returning to democracy (Proclama de la Coordinadora de Resistencia Mapuche Pelentaro, 1986; Centro de Estudios y Documentación Mapuche Liwen, 1990).

From the 1990s onwards, the critical position became increasingly intense, through different organisations (Council of All Lands, 1991; Lafkenche Territorial Identity, mid-1990s; Coordinadora Arauco Malleco, 1996; Partido Político Mapuche Wallmapuwen, mid-2000s; Organs of Territorial Resistance, since 2012).

1.4. From the Agenda to the Against-Agenda

For the political economy of communication, social movements will experience, among other things, transformations in communication dynamics, such as at the level of internal, external, and media communication, so that “social movements have developed communication strategies and policies” as well as “have questioned the dominant forms, technologies, images and communication messages”, using “literacy campaigns, street theatre, alternative newspapers, video and film production, alternative computer networks” (Mosco, 2009, p. 347-348).

It is unnecessary to mention the details of the correspondence between these descriptions and what was observed in the Mapuche Indigenous social movement that we analyze here. It is enough to indicate, as we will see below, the widespread use of the media, first hegemonic traditional media belonging to the large power groups and then against hegemonic alternative media.

2. Materials and Methods

The study considered three methodological strategies:

a) Analysis of a total of 1033 news items corresponding to six hegemonic media and four against hegemonic media from Argentina and Chile. The news corpus was analyzed with the content analysis technique, based on the variables and categories (146) and using SPSS.

b) 21 individual and group interviews with Mapuche Indigenous leaders from Chile and Argentina. For the analysis, a Qualitative Content Analysis was used, using open, axial, and selective coding. First, an attempt is made to express the data through concepts. In this, the researcher dissects, fragments, and segments, and unravels the data contained in the text, trying to enumerate a series of emerging categories (Carrero, Soriano & Trinidad, 2006). To do this, the work of coding and analyzing the data was carried out with the support of the Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS) Nvivo 12, to categorize the codes and categories of the open and axial coding and group them in a dendrogram.

c) Review and documentary analysis of historical texts of the Indigenous movement. Qualitative content analysis was used.

3. Results

Based on the results and their analysis, it was mainly possible to

a) Identify the strategies used by the Mapuche movement, and

b) Characterize the against-agenda

3.1. The Dispute for the Agenda

1) The against-agenda is another agenda built within the framework of a dispute for control of the semiotic-communicational code that gives meaning to society, its relationships, and, especially, its possible transformations.

Here we are interested not only in analyzing how social movements can access agendas and intervening in them, but especially in how it is possible to build new agendas. These cases that we will see can be better explained from one of the most recent stages of agenda-setting research, agenda building, which is characterized by “the complex relationships that occur between the different actors and norms of communication; and that mutually influence the formation of the media agenda” (Zunino, 2018, p. 200). Although, as Zunino (2018) maintains, the prominence of the public, for example through the widespread use of social networks, could affect the power of the agenda-setting hypotheses; It is important to consider that said activism - as we will see - occurs within the same journalistic system, although in a first phase it will be through intervention in traditional media and a second phase the media system will be expanded by incorporating new media. What is interesting, furthermore, is that these operations to configure an alternative agenda occur within the framework of a highly concentrated media system that can inhibit activists (Youmans & York, 2012); and, on the other hand, imply a strategic analysis of the journalistic and media system, specifically the weaknesses of journalistic routines and the sensitivities of the informative input (the newsworthiness criteria). In this way, effectively “the usefulness of the concept of agenda should be problematized” (Zunino, 2018, p. 205), in which case the analysis of new practices, new media, and the complexities in relationships, without a doubt, constitute a challenge for the field of communication.

Although agenda building “focuses on the news construction process and the elements that influence it” (Aruguete, 2017, p. 38-39) and even emphasizes collective construction and the role of spokespersons (Charron, 1998; Lang and Lang, 1981; Sádaba, 2008), in the case of the construction of an agenda by social movements, it is particularly about analyzing the possibilities generated by the relationships between the media and sources, articulations that even agenda building fails to explain sufficiently, so to explain some situations it is necessary to understand how certain voices of actors and sources (which are not the same, of course) can be transformed at a given moment into “newsmakers” (agenda setters), that is, occupy spaces of enunciation that allow them privileged access to the media. The questions, however, are more complex, since they involve distinguishing, on the one hand, between the influence that different media have and, on the other hand, the impact that various social actors can have. If we grant a relevant role to these actors or “newsmakers”, we should ask ourselves if we are talking about a predominance of the public´s agenda, which in certain circumstances also become decision makers? That being so, should we explain, in certain socio-political conjunctures, how the agenda of the public - who become political actors in such circumstances and, therefore, some of them constitute “newsmakers” - are interrelated, and even merged? -, the political agenda, highly sensitive to the public -as voters-, and the media agenda, whose structure, even though it is highly concentrated, opens spaces for certain counter-hegemonic discourses that nourish the conflictive nature of the news? Finally, we can ask ourselves if, in this case, the explanatory model of agenda setting is operational or if, on the contrary, we have to look for other explanatory models.

Certainly of interest is the idea of an interest group agenda, promoted by diverse groups that “identify, define and raise social problems [whose] agenda is the source of the public agenda” and for whom new technologies, video cameras, newsletters, and other grassroots activities, play a key role (Zhu, 1992, p. 826). In this sense, it is interesting to analyze the media agenda as topics that compete for attention and space, in such a way that it is also possible to identify how some topics/problems arise at the expense of others that fall by the wayside (Dearing and Rogers, 1992; Zhu, 1992).

The idea of a Network Agenda Setting Model (NAS) also contributes to the explanation of the phenomena raised here, specifically in the sense that “the media can group different objects and attributes and highlight these packages of elements in the public's mind simultaneously [that is,] the media can construct the connections between agendas, thus constructing the centrality of the elements of a certain agenda in the public's mind” (Guo, Vu & McCombs, 2012, p. 55-56). Without a doubt, a dynamic understanding of the media and their agendas allows us to better explain the role of existing interconnections in the construction of new agendas. For example, the role that the network plays in the hands of social movements to access the media agenda is fundamental. In fact, “The Network then plays a crucial role in forcing the media to pay attention to the movement, both as a way of organizing new protests and in disseminating criticism of the media system and achieving an international diffusion that forced the state media to include the protests in their agenda” (Candón, 2012, p. 225); and although the relationship between the use of the Internet and access to the media agenda is not completely quantified, it is evident that social movements incorporate various agendas, such as the public, the media and the political-electoral agenda.

3.2. The Importance of Networking

Regarding the broad and complex presence of different media, amplified by the multiple virtual networks in use, some hypotheses are proposed. Probably one of the most pertinent cases that concerns us here is the one that indicates that there is a thematic influence between the various media (Aruguete, 2016). To the hegemonic persistence that this could imply if we consider that the emerging media would tend to replicate the contents of the dominant media - as another form of domination - it is worth mentioning recent experiences in which a scenario of political crisis (discredit of traditional actors ) and media (disbelief in the function of traditional media) generates a different correlation, particularly when it is the alternative media that practically assume a spokesperson role for the mobilized social groups. Several of the media emerge amid the situation and from it, they even manage to project themselves. Aruguete (2016) proposes a refreshing analysis in this regard, indicating some very necessary doubts and concerns. She asks, for example, “If social media begins to occupy that leadership role, will it be necessary to adapt the postulates of the agenda setting to a new model?” (Aruguete, 2016, p. 165).

3.3. The Role of New Media

On the other hand, as the counter-agenda arises in contexts of crisis, the need for guidance becomes an important axis, more than other factors such as personal experience or the extent of exposure to the media. This “need for guidance is manifested in all areas that the individual perceives as important for his life or for the society of which he is a part (relevance) and about which he has no information (uncertainty)” (Ardèvol-Abreu, Gil de Zúñiga and McCombs, 2020, p. 7). In fact, the need for orientation may be rather associated with the search for new experiences with new media (for example, the appearance of new media, usually digital, that address topics and problems in a counter-informational way, as well as to relatively new exhibition dynamics, with a tendency towards multimedia and transmedia practices).

However, it is important to consider that we are talking about situations in which the role of traditional political authorities as main agenda-setters is broken, giving rise to new emerging leadership. Let us remember that in the case at hand, it is a political rupture generated within the framework of a social outbreak, a period of various mobilizations, and a comprehensive criticism of the current policy, which finally gives rise to the drafting of a new constitution. The harsh social dispute that, in this case, gives rise to a new constitution is a political fact that, without a doubt, disrupts the bases of any explanatory model.

3.4. The Socio-Political Situation is Key

All of the above, for example, we can raise and problematize regarding the process of the Mapuche indigenous movement in Chile, whose media actions, along with transforming the ecosystem, have managed to install content with unusual efficiency, as “actors who strive to access the media agenda and install their demands and proposals there” (Aruguete, 2017: 47).

3.5. Production of the Emergent

Very probably the most emblematic case is how a concept like wallmapu manages to position itself on the media and political agenda, practically going from its absence or presence linked mainly to certain demand and protest groups to broad visibility in the political discourse and of the means, in a few years. This concept is an example of the result of persistence in agendas, through the intervention of traditional media, but especially through the installation of new media.

From a critical perspective, we will understand that this concept is inevitably part of an ideological discursive framework, to which it is integrated in a situated way in a contingency that gives it meaning, even if it is counterhegemonic.

The above, namely, the linguistic and ideological character of wallmapu, make this expression, above all, a triumph of linguistic human work; the result of a lack, of a need for relationships with others. Thus, wallmapu is a profound expression of the lack of genuine dialogue and horizontal relationships. It is a cry, both of confusion and hope because it entails The Utopia of the construction of the Mapuche Country (Ancán and Calfío, 1998). That of language, we must not forget, is a collective and community social activity. In effect, wallmapu is the product of a collective linguistic work that produces the collective language, within the framework of the speech exercise of individuals who, by the way, come together in the same common space; and that is then capable of scaling the discursive planes from the most intimate of the communities to the general public opinion.

3.6. Collective Production of Language

Now, it is not possible to understand this case without considering the specific weight that some actors and sources suddenly acquire, as is the case, for example, of the political role that Mapuche actors suddenly assume as conventional constituents, as is the case of Elisa Loncón, who even presided over the Constituent Convention. The above is also explained because “not all news has the same power to influence the political agenda” (Aruguete, 2017, p. 48) and because the quantification of which sources and actors appear in the media does not allow us to explain the capacity that They have certain sources - at a certain time and space - of negotiating everyday reality and helping to build, from said negotiation, the media representations of said everyday reality.

3.7. Strategies

Continuing with the above, we can observe two strategies:

3.7.1. Intervention of Hegemonic Agendas

One of the main problems for understanding counterhegemonic phenomena and processes has been the hegemonic conception and interpretation of some communicative and media theories and models, such as the effects model and the current of uses and gratifications. In the case of the latter, the question of gratifications (tastes, expectations, and experiences) prevails, but in its Latin American aspect, we observe an interesting focus on social uses (Orozco and González, 2012). In this sense, there are two challenges for a sufficiently critical view, which has been ignored and which we can represent with two types of questions: (a) about the nature of the study, that is, going from what do the media do with the public? towards what audiences do with the media?, and (b) about the purpose of the study, that is, how is greater empowerment of audiences achieved? These seemingly simple twists will allow us to overcome the determinism of the media to enable the emancipation of audiences. Likewise, they invite us to see beyond the limits of the theory itself, for example, that “mediations and practices converge in uses” (Orozco, 1998). In a similar sense, we can reverse the logic of the agendas, moving from the question: how do the media affect/influence the issues that audiences will consider? Towards How do the interests of the public affect/influence the topics that the agendas will consider? Furthermore, in what ways could audiences generate these transformations?

As we will see below, one of the first ways is the intervention of agendas. In the section that follows this one, we will see the second, the production of new media.

If we consider that the media agenda establishes a correlation between the themes raised in the media content and the problems reported by the public, we will understand that what has not been included in the media does not exist for public opinion.

This phenomenon, “which has been demonstrated in numerous investigations in different areas of study, political-electoral, social, cultural, religious, marketing, business” (Abela, 2012, p. 522) explains, on the one hand, the need to reverse the situation. of invisibility of certain groups or movements and, on the other hand, the efforts deployed to achieve said visibility. In this sense, effectively, it is about installing certain themes and problems in public opinion.

Although studies of the conflict between the nation-state and the Mapuche people usually incorporate press information as a source (Rojas and Miranda, 2015), they fail to visualize the media-conflict framework, in which the media constitute another actor (Del Valle, 2024, 2023, 2022b and 2022c). This is mainly due to a double focus, on the one hand, historiographical and on the other hand sociopolitical, which prevents an in-depth understanding of the singularities of the media, beyond the coverage and treatment of the content.

The analysis of the first of the arson attacks against the machinery of one of the forestry companies in the region allows us to understand one of the milestones of the conflict, beyond the purely conflictual. This arson attack will play an important role, both because it gives rise to a new phase and because it implies a more strategic view, whether intended with the facts or derived later from them. However, certainly, we must begin by pointing out that this arson attack supposes: (a) the failure of indigenous protest as a mechanism of political inclusion, and (b) that social protest had not generated any benefit for the Mapuche movement. Considering the latter, the move towards violence seemed an obvious strategy. However, is it sufficiently explained by the failure of previous forms of protest? Are there other elements to consider?

It is not possible to understand the emergence of violence in the Mapuche movement -expressed in the arson attacks against the machinery of forestry companies and the subsequent ones- without also considering the installation of a new media culture starting from the post-dictatorship (1990), which was expressed not only in morning television as the main format but also in a more casual coverage and treatment of the press and radio, particularly of some dissident sectors. This opening, however, as it later became evident, only consisted of a one-time exercise and had no relationship with the strong economic, ideological, and cognitive concentration of the media structure in Chile, which will continue to be maintained. What is evident is the correlation between the events that occurred in the region and their presence in the media.

The milestone represented by the first arson attack on three logging trucks belonging to the Bosques Arauco forestry company, which occurred in December 1997, is characterized by high coverage and informative treatment at the regional and national levels (Pairicán y Álvarez, 2011). The political-strategic nature of the events (1997) has been widely recorded as a milestone (Pairicán and Álvarez, 2011).

The coverage and treatment of this event and subsequent ones are part of a global strategy that will include various platforms, with the purpose of breaking into the media ecosystem head-on (García, 2014: 177).

Before the widespread use of social networks, the strategy consisted of using the power of hegemonic media in a counter-informative manner. This was a complex agenda intervention strategy. On the one hand, because it had to break the existing information fence against the different actions that will affect the interests of the nation-state and forestry companies and, on the other hand, because it required a “wake-up call” truly capable of giving visibility by circumventing guidelines, practices and journalistic routines strongly rooted in power.

3.7.2. Creating New Media to Build a Media Against-Agenda

With the beginning of the new century, the need to create new media will emerge with enthusiasm, to move from the intervention of the agendas of the hegemonic media to the formation of its agenda, as well as to constitute a discursive counterhegemony that reinforces the first advances. of the counter-information activity of the second half of the 90s of the last century (Marimán, 2011). Meanwhile, from the point of view of the users of the different media, we observe a clear trend towards the incorporation of these networks in political activity.

Now situated in the era of widespread use of social networks, the appropriation of virtual spaces is as noticeable as it is efficient, as shown today, for example, by the intense activism of social movements on Twitter (Sierra, 2021). Notwithstanding the above, research also shows us that Mapuche actors distinguish three roles associated with the media, namely, (a) hegemonic roles (especially in the case of media belonging to the country's economic groups), ( b) counterhegemonic roles (especially in the case of the media belonging to the groups themselves), and (c) relative roles, which together with allowing the visibility of the Mapuche movement generate uncontrolled scenarios lacking planning (Del Valle, 2022a). Now, the interviewed actors do not hesitate to highlight some of the main strengths of new media and the use of social networks (Del Valle, 2022a).

a) Allows the active incorporation of new actors: “incorporate Mapuche youth into these processes.” (Interviewed, April 2, 2020).

b) It allows for dissemination, validation, and cohesion: “establishing communication justice, equating Mapuche presence in the Chilean collective imagination” (Interviewed, May 11, 2020).

c) It allows us to inform and achieve unity: “which allows us to be united and active, despite the multiple adversities, which are triggered from time to time because this living resistance is latent, in a silent network” (Interviewee, May 22, 2020).

d) Allows you to think differently: “Without independent media, it would be impossible to think differently” (Interviewee, June 13, 2020).

e) It allows for incorporating new allies and transmitting hope: “The multiple voices from different places can awaken hope in those who are fainting or reinforce the conviction of those who remain fighting, finding allies who fight on other rivers” (Interviewee, 16 June 2020).

f) It allows access to the diversity of perspectives: “When this type of communication did not exist, you could only find out about alternative initiatives and/or resistance if the traditional media were interested in this type of news or if someone traveled and acted as nexus […] allow access to views of the most diverse facts; which has been fundamental when there is a policy of demonization of the resistance movement” (Interviewed, June 16, 2020).

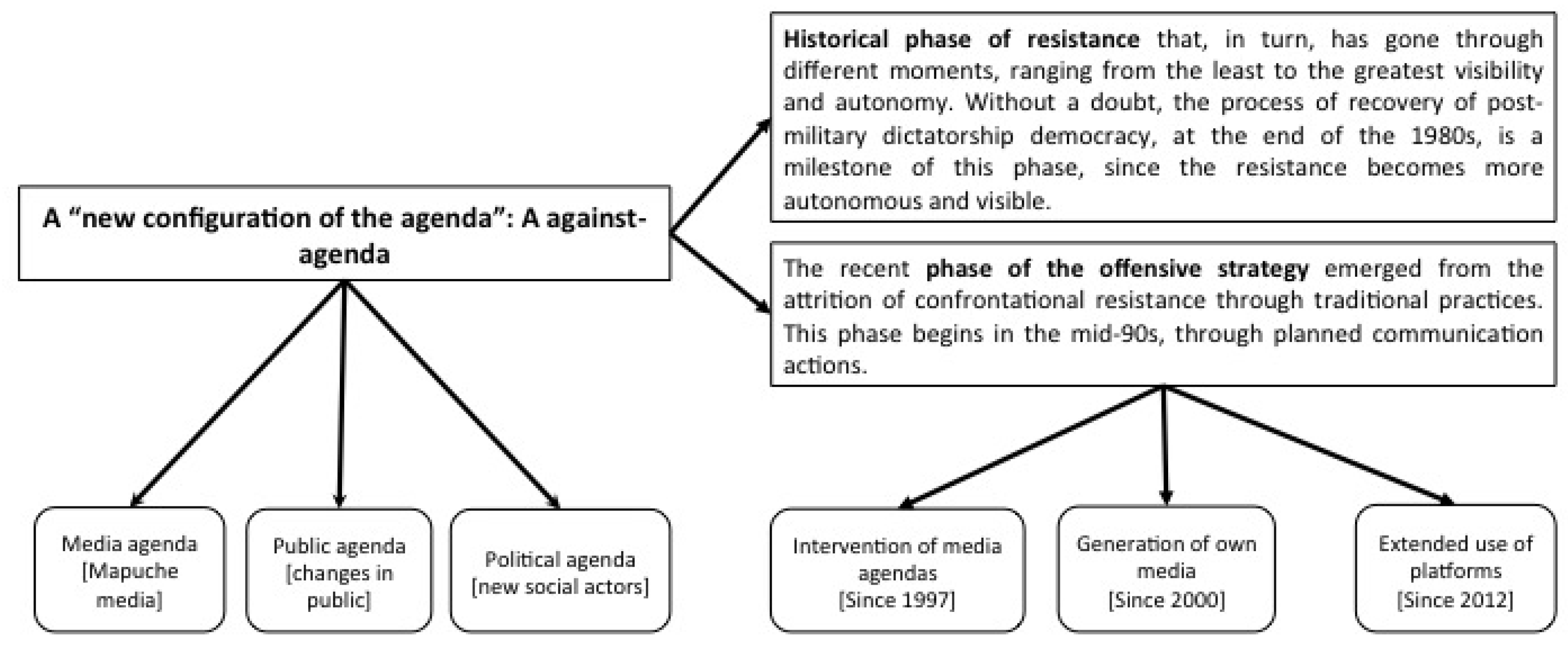

Below, we can see a summary of what has been stated up to this point (Figure 1):

In this way, the creation and use of our media constitute a strategy that has shown its effectiveness over time, because it manages to permeate both the intra-community space and the rest of the population: “Thus, indigenous media accelerate the process of recreation and reinvention of rituals favoring a (re)elaboration of their Mapuche identity and the recovery of their ethnic consciousness” (García, 2014, p. 184).

Now, if we synthetically consider the media strategies used during the second half of the 90s of the 20th century and compare them with the strategies used more than twenty years later, we will observe the following comparative table (Table 1):

Since 1997

(arson attacks) |

Since 2019

(social outbreak) |

| Installation of a more planned media narrative, with very clear justification speeches; belligerent discourse |

More consolidated speech, with a clear conceptual basis; unifying speech |

| There are no means and there is the discourse of a story that one wants to establish. |

Greater discursive control, with the positioning of content (wallmapu) and places (constituent convention), allows for greater strengthening of the discourse |

| Context of intervention of hegemonic agendas |

Context of creating own media |

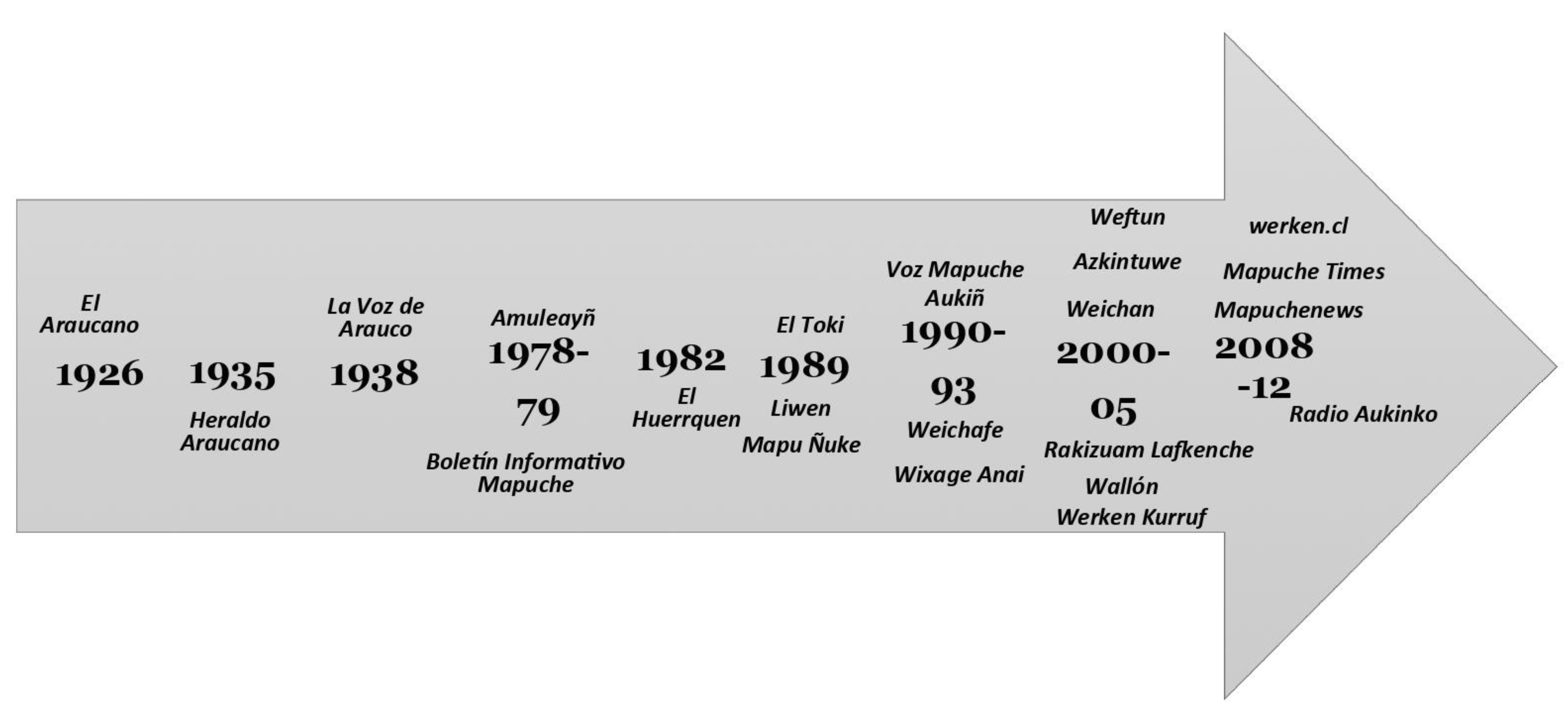

Although we have mentioned some Mapuche media so far, we must remember that it is not a recent phenomenon and that it is expressed in multiple ways (Gutiérrez, 2014) (Figure 2).

4. Discussion

The discussion on the possibilities for social movements associated with different groups to be able to install an alternative agenda to the agendas of the big business or commercial media is open.

This paper addresses their possibilities based on a particular experience associated with the Mapuche indigenous movement present in the territories of Argentina and Chile. This case provides relevant data that allow a cautious analysis of these same possibilities. On the one hand, the contexts of social and political conflict usually contribute to the establishment of these alternative agendas or against-agendas. However, for the same reason, it is possible to think that their duration is also restricted to the context that supports them.

Therefore, it is important to advance in this line of research on the possibilities of the emergence of alternative agendas or against-agendas of socially excluded groups, based on comparative studies and analyzing in detail the impact of post-conflict social conditions on their permanence. In the case analyzed, the results of the work of collective production and reproduction of language remain.

On the other hand, it is important to consider the detailed analysis of the different variables that make up the contexts of socio-political conflict when studying the possibilities of alternative media agendas (counter-agendas). Precisely here are the limitations of the present work, which allow us to explore new hypotheses to guide future research, namely, if the construction of alternative agendas or counter-agendas by social movements is subject to the contingency that generates the possibilities of their emergence, it is possible to think of limited possibilities as well as to think of the strategies and tactics of maintaining the conflicts as more or less permanent situations. This, for example, would explain the characteristics of the interactions between social movements and socially excluded groups with the State and its institutions.

Finally, it is important to consider the role played by the subsistence of alternative media that maintain discourses over time. In this way, alternative media cannot be understood only as momentary devices, but as permanent bets capable of giving continuity to the discourses of social movements and socially excluded groups.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the dispute over the code through the configuration of agendas to achieve social transformations, gives us an account, at least, of the following situations that must be taken into consideration:

On the one hand, the high levels of concentration of media ownership and content generate important imbalances as they do not make room for emerging voices, themes, and problematizations, which are systematically marginalized or mistreated.

Secondly, as the media not only put into circulation a more or less objectified event but also select, frames and ideologically interpret certain events considered important, based on hegemonic interests; A complex situation of inaccessibility, marginalization, and lack of information justice is generated that damages the right to communication as a social good.

On the other hand, the need to dispute the code and social meaning by making excluded subjectivities public forces newsworthiness to be managed in various ways, such as the media reaction to conflict and violence. The notions of conflict and violence often act simultaneously as categories of social denunciation and as media responses to expectations that the media themselves have about the social and political. In this way, for example, expressions such as “Mapuche conflict” are not mere factual descriptions, but also arise as sociopolitical complaints and, at the same time, as a materialization of the expectations of the media system and not necessarily as an informative condition. -communicational. We could maintain that just as violence and conflict are sustained by processes of social and historical accumulation, violence and conflict in the media also operate as a process of media accumulation of informational expectations about said violence and conflict.

For its part, strategies that achieve high informational-communicational profitability, that is, that allow breaking hegemonic inertia, end up prevailing and becoming a learned practice.

On the other side, if violence is imposed as a media strategy and political positioning, it will tend to remain a practice.

Finally, the relational practice of violence is never managed in such a way that it is controlled, so that once generated and installed it will inevitably give rise to uncontrolled violence, which will not discriminate between material goods and human lives.