Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

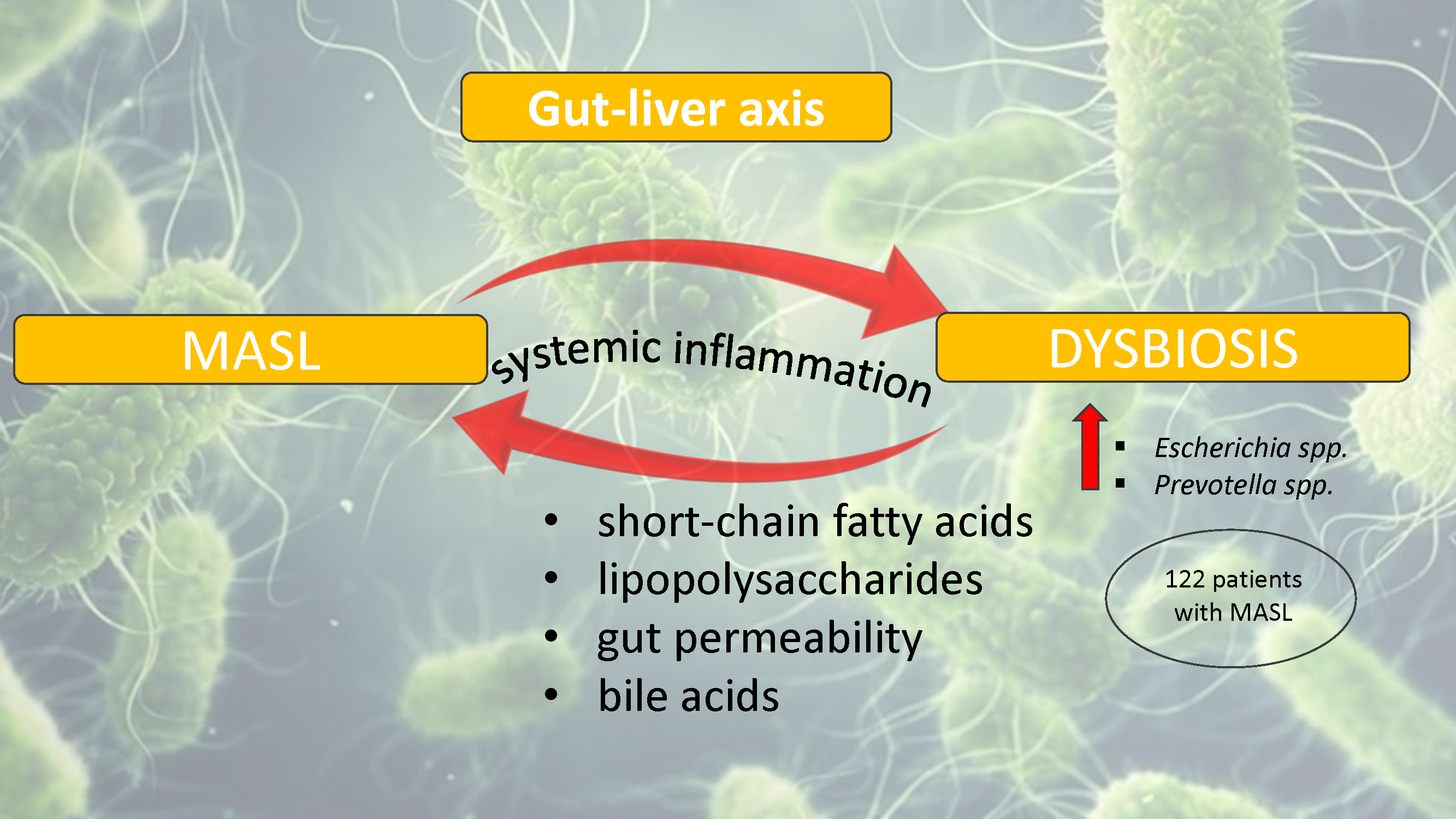

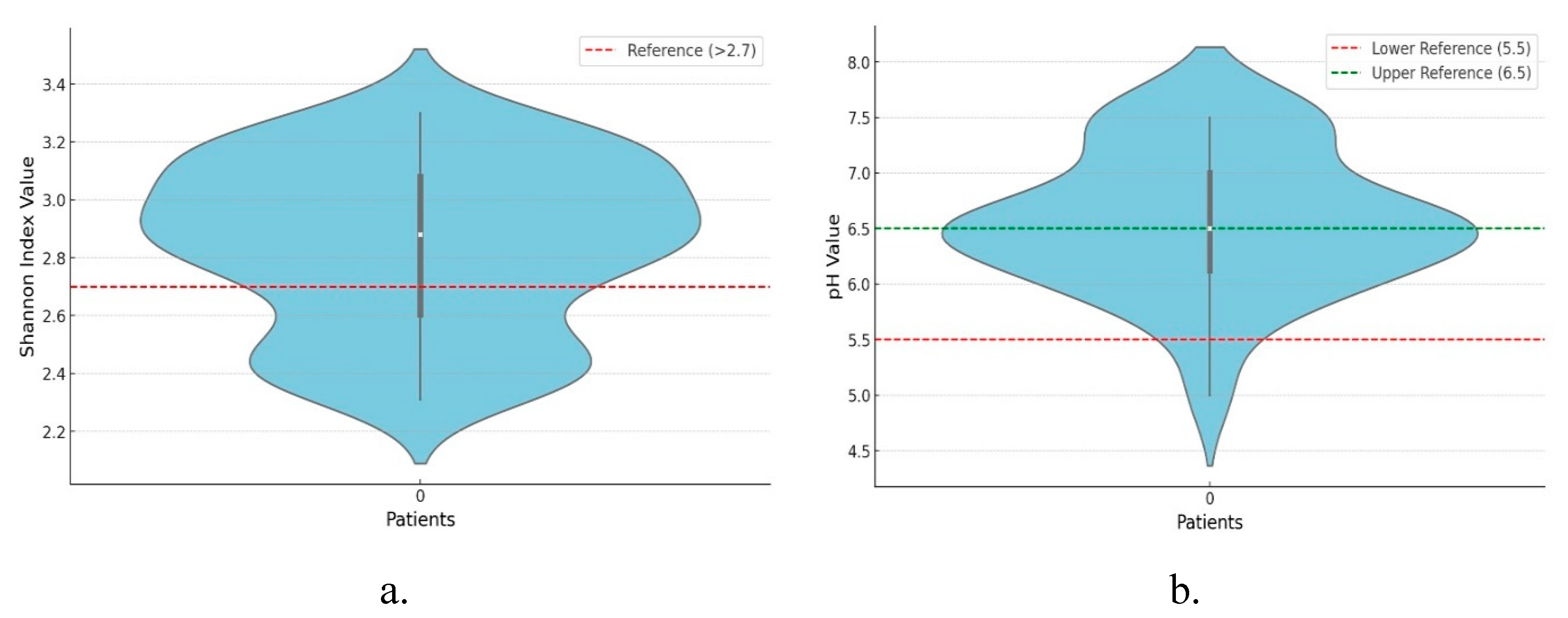

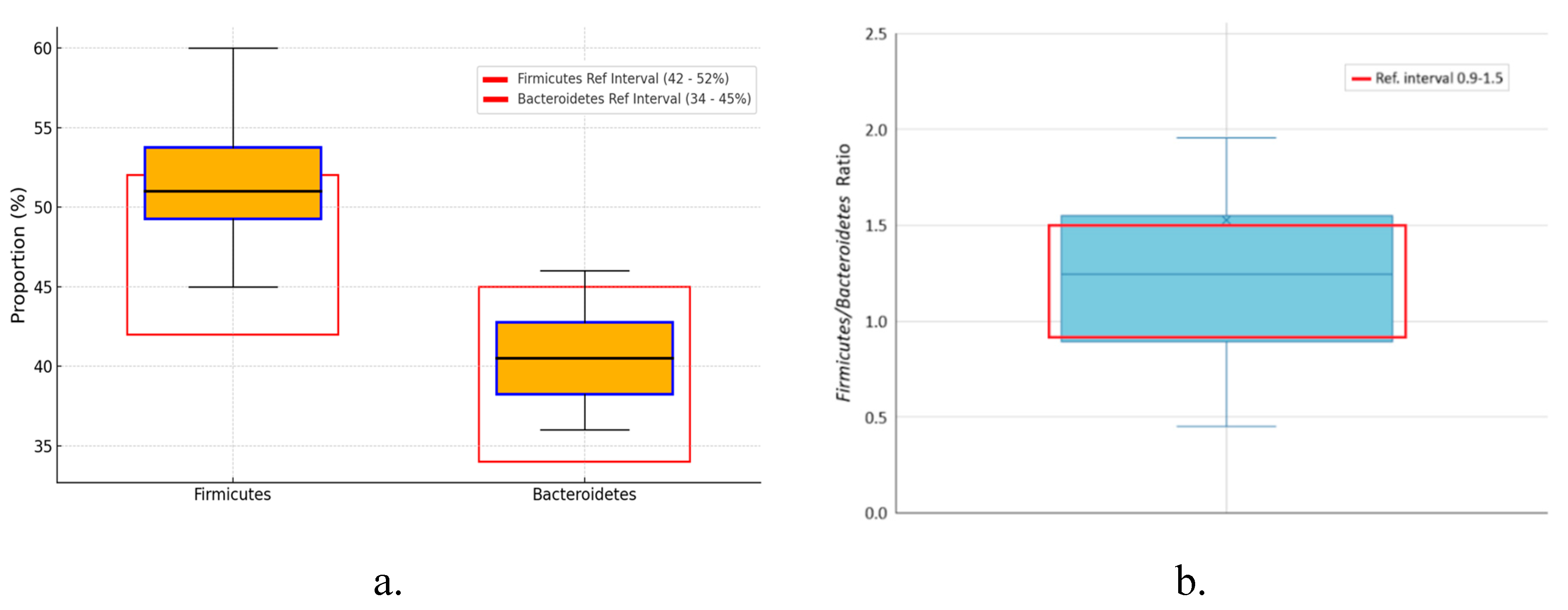

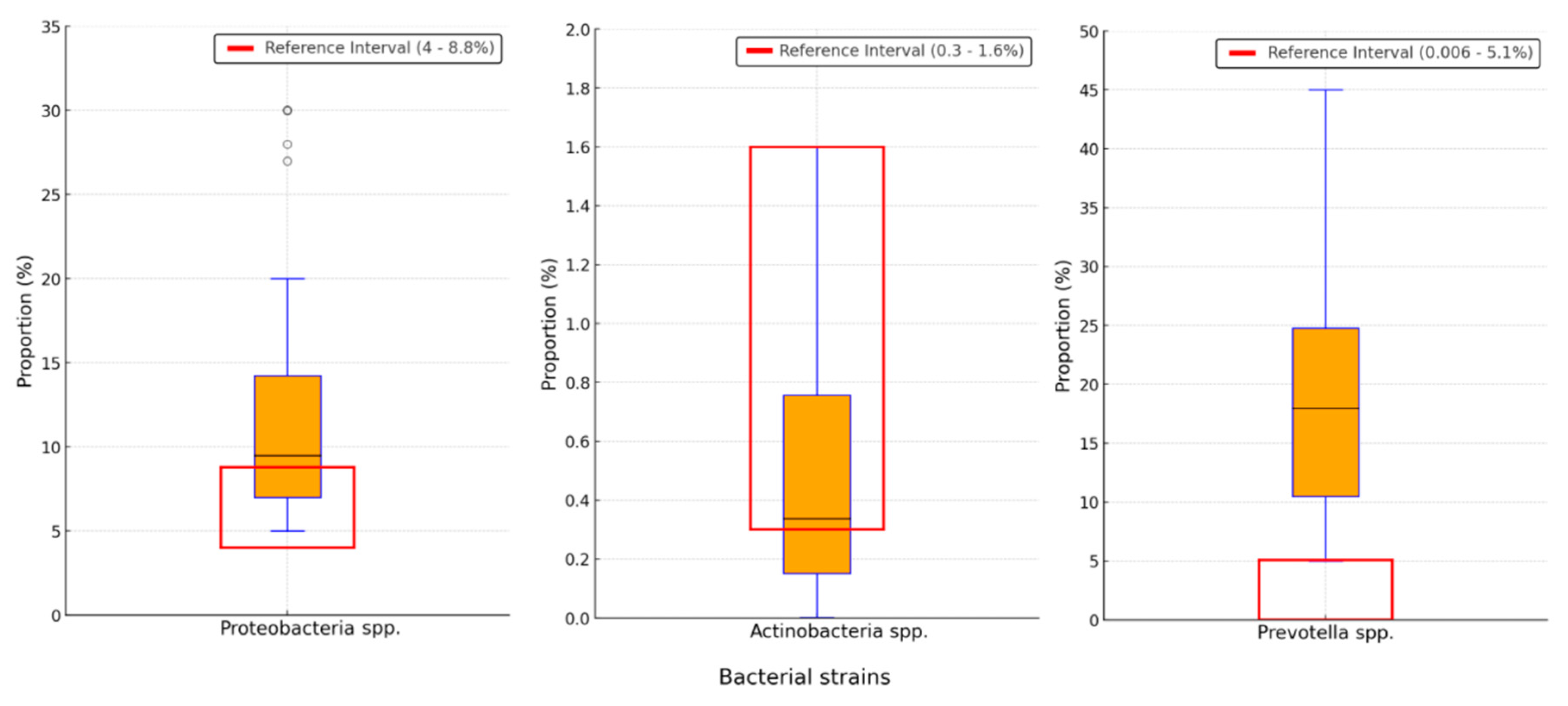

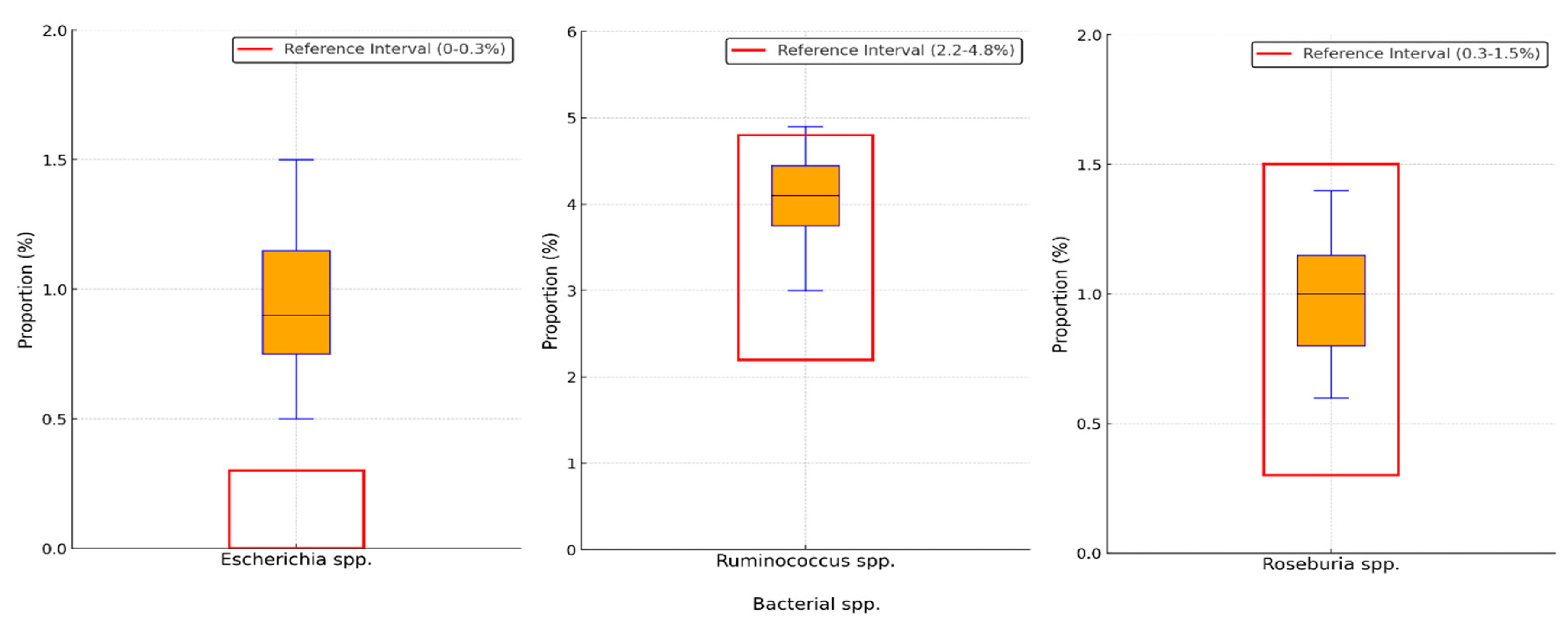

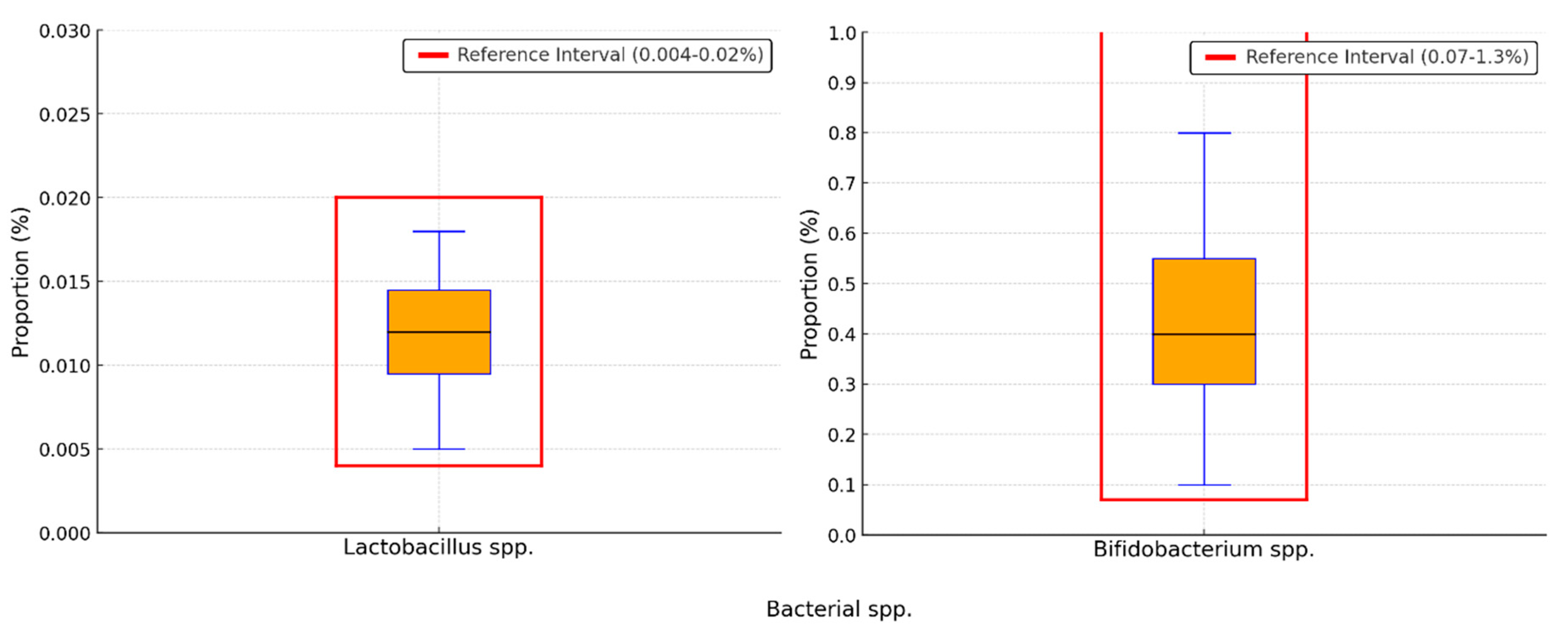

Background/Objectives: The gut-liver axis is bidirectional and influences the body's homeostasis. Pathologies such as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver (MASL) can have detrimental effects on the human microbiome, with multiple systemic effects. Furthermore, the geographical particularities of the intestinal microbiome may influence liver disease. The study's outcome was to identify dysbiosis in a group of patients with MASL from the western region of Romania. Methods: The NGS shotgun genomic sequencing (WGS metagenomics) method was used to identify bacteria in fecal samples. The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics software. Results: Out of the 122 MASL patients included in the study, 43 (35.24%) exhibited low alpha diversity. In the subgroup with a normal biodiversity index, approximately half were identified with a Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio below the lower reference value, while the remaining patients presented dysbiosis based on decreased concentrations of Proteobacteria and Prevotella, considered among the most relevant species supporting dysbiosis. A higher prevalence of Prevotella species (15.99± 13.65%) was identified in the study cohort. Conclusions: The present study demonstrates that patients with MASL from the western region of Romania exhibit criteria for intestinal dysbiosis, namely reduced bacterial diversity, along with significant alterations in populations of Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Prevotella. Together, these findings suggest a possible influence of geo-cultural factors on the intestinal microbiome, highlighting the need for regionally adapted therapeutic interventions to support liver health.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Gut-Liver Axis and the Role of Gut Microbiota in Liver Diseases

1.2. External Influences on Microbiota and Regional Implications

2. Results

2.1. Baseline Characteristics

2.2. Distribution of the Biodiversity Index and Bacterial Strains

3. Discussion

3.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

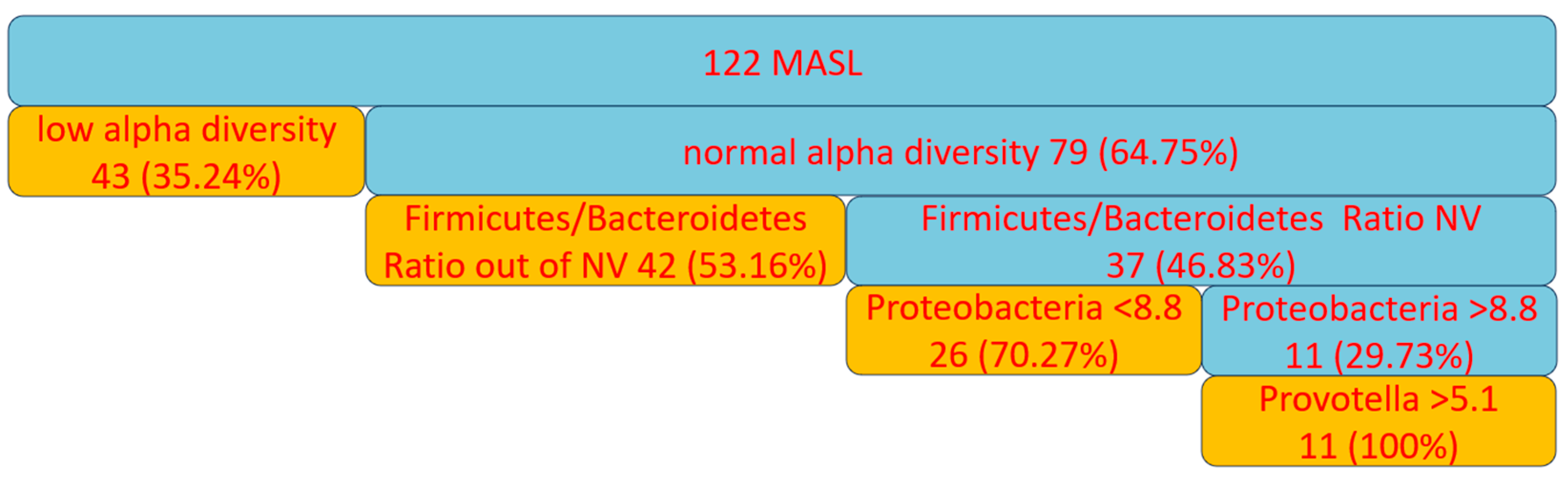

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

- age over 18 years,

- at least 4 weeks after a colonoscopy or enema,

- confirmed diagnosis of MASL,

- absence of fibrosis (F0-F1 on FibroScan),

- signed informed consent to participate in the study,

- born and lived only in the western region of Romania.

- age under 18,

- treatment with antibiotics, antifungals, probiotics, proton pump inhibitors, bismuth, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, rectal suppositories, enemas, activated charcoal, digestive enzymes, laxatives, mineral oil, castor oil, and/or bentonite clay and quercetin within 90 days,

- medical history of severe liver disease, gastrointestinal disorders, gastrointestinal surgery within the last 6 months

- active bleeding gastrointestinal/ rectal/ menstruation,

- long-term treatment with immune suppression therapy,

- chronic alcohol /illicit substance use,

- pregnancy or breastfeeding,

- restrictive diet,

- food allergies or intolerances.

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Younossi, Z. M.; Golabi, P.; Paik, J. M.; Henry, A.; Van Dongen, C.; Henry, L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): A systematic review. Hepatology 2023, 77, 1335–1347. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Debelius, J.; Brenner, D. A.; Karin, M.; Loomba, R.; Schnabl, B.; Knight, R. The gut–liver axis and the intersection with the microbiome. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2018, 15, 397–411. [CrossRef]

- Bäckhed, F.; Ding, H.; Wang, T.; Hooper, L. V.; Koh, G. Y.; Nagy, A.; Semenkovich, C. F.; Gordon, J. I. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101, 15718–15723. [CrossRef]

- Buzzetti, E.; Pinzani, M.; Tsochatzis, E. A. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism 2016, 65, 1038–1048. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, E.; Yilmaz, Y. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD): A multi-systemic disease beyond the liver. Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology 2021, 10, 329–338. [CrossRef]

- Le Roy, T.; Llopis, M.; Lepage, P.; Bruneau, A.; Rabot, S.; Bevilacqua, C.; Martin, P.; Philippe, C.; Walker, F.; Bado, A.; Perlemuter, G.; Cassard-Doulcier, A.-M.; Gérard, P. Intestinal microbiota determines development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Gut 2012, 62, 1787–1794. [CrossRef]

- Schnabl, B.; Brenner, D. A. Interactions between the intestinal microbiome and liver diseases. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 1513–1524. [CrossRef]

- Rau, M.; Rehman, A.; Dittrich, M.; Groen, A.K.; Hermanns, H.M.; Seyfried, F.; Beyersdorf, N.; Dandekar, T.; Rosenstiel, P.; Geier, A. Fecal SCFAs and SCFA-producing bacteria in gut microbiome of human NAFLD as a putative link to systemic T-cell activation and advanced disease. United European Gastroenterol J 2018, 6, 1496-1507. [CrossRef]

- Saltzman, E.T.; Palacios, T.; Thomsen, M.; Vitetta, L. Intestinal Microbiome Shifts, Dysbiosis, Inflammation, and Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 61. [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.; Rivera, L.; Furness, J. B.; Angus, P. W. The role of the gut microbiota in NAFLD. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2016, 13, 412–425. [CrossRef]

- Loomba, R.; Seguritan, V.; Li, W.; Long, T.; Klitgord, N.; Bhatt, A.; Dulai, P. S.; Caussy, C.; Bettencourt, R.; Highlander, S. K.; Jones, M. B.; Sirlin, C. B.; Schnabl, B.; Brinkac, L.; Schork, N.; Chen, C.-H.; Brenner, D. A.; Biggs, W.; Yooseph, S.; Venter, J. C.; Nelson, K. E. Gut microbiome-based metagenomic signature for non-invasive detection of advanced fibrosis in human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Metabolism 2017, 25. [CrossRef]

- Linares, R.; Francés, R.; Gutiérrez, A.; Juanola, O. Bacterial Translocation as Inflammatory Driver in Crohn's Disease. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 703310. [CrossRef]

- Di Vincenzo, F.; Del Gaudio, A.; Petito, V.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F. Gut microbiota, intestinal permeability, and systemic inflammation: a narrative review. Intern Emerg Med 2024, 19, 275-293. [CrossRef]

- Chakaroun, R.M.; Massier, L.; Kovacs, P. Gut Microbiome, Intestinal Permeability, and Tissue Bacteria in Metabolic Disease: Perpetrators or Bystanders? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1082.

- Ilan, Y. Leaky gut and the liver: a role for bacterial translocation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2012, 18, 2609-2618. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Iwaki, M.; Nakajima, A.; Nogami, A.; Yoneda, M. Current Research on the Pathogenesis of NAFLD/NASH and the Gut–Liver Axis: Gut Microbiota, Dysbiosis, and Leaky-Gut Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11689. [CrossRef]

- Fukui, H. Gut-liver axis in liver cirrhosis: How to manage leaky gut and endotoxemia. World J Hepatol 2015, 7, 425-442. [CrossRef]

- LaBouyer, M.; Holtrop, G.; Horgan, G.; Gratz, S.W.; Belenguer, A.; Smith, N.; Walker, A.W.; Duncan, S.H.; Johnstone, A.M.; Louis, P.; et al. Higher total faecal short-chain fatty acid concentrations correlate with increasing proportions of butyrate and decreasing proportions of branched-chain fatty acids across multiple human studies. Gut Microbiome 2022, 3, e2. [CrossRef]

- Ecklu-Mensah, G.; Choo-Kang, C.; Maseng, M.G.; Donato, S.; Bovet, P.; Viswanathan, B.; Bedu-Addo, K.; Plange-Rhule, J.; Oti Boateng, P.; Forrester, T.E.; et al. Gut microbiota and fecal short chain fatty acids differ with adiposity and country of origin: the METS-microbiome study. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 5160. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, S. H.; Belenguer, A.; Holtrop, G.; Johnstone, A. M.; Flint, H. J.; Lobley, G. E. Reduced dietary intake of carbohydrates by obese subjects results in decreased concentrations of butyrate and butyrate-producing bacteria in feces. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2007, 73, 1073–1078. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, J. S.; Hylemon, P. B.; Ridlon, J. M.; Heuman, D. M.; Daita, K.; White, M. B.; Monteith, P.; Noble, N. A.; Sikaroodi, M.; Gillevet, P. M. Colonic mucosal microbiome differs from stool microbiome in cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy and is linked to cognition and inflammation. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2012, 303. [CrossRef]

- Ridaura, V. K.; Faith, J. J.; Rey, F. E.; Cheng, J.; Duncan, A. E.; Kau, A. L.; Griffin, N. W.; Lombard, V.; Henrissat, B.; Bain, J. R.; Muehlbauer, M. J.; Ilkayeva, O.; Semenkovich, C. F.; Funai, K.; Hayashi, D. K.; Lyle, B. J.; Martini, M. C.; Ursell, L. K.; Clemente, J. C.; Van Treuren, W.; Walters, W. A.; Knight, R.; Newgard, C. B.; Heath, A. C.; Gordon, J. I. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science 2013, 341. [CrossRef]

- Di Ciaula, A.; Bonfrate, L.; Khalil, M.; Portincasa, P. The interaction of bile acids and gut inflammation influences the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Internal and Emergency Medicine 2023, 18, 2181–2197. [CrossRef]

- Ridlon, J.M.; Kang, D.J.; Hylemon, P.B.; Bajaj, J.S. Bile acids and the gut microbiome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2014, 30, 332-338. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Cowley, E.S.; Wolf, P.G.; Doden, H.L.; Murai, T.; Caicedo, K.Y.O.; Ly, L.K.; Sun, F.; Takei, H.; Nittono, H.; et al. Formation of secondary allo-bile acids by novel enzymes from gut Firmicutes. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2132903. [CrossRef]

- Osuna-Prieto, F.J.; Xu, H.; Ortiz-Alvarez, L.; Di, X.; Kohler, I.; Jurado-Fasoli, L.; Rubio-Lopez, J.; Plaza-Díaz, J.; Vilchez-Vargas, R.; Link, A.; et al. The relative abundance of fecal bacterial species belonging to the Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla is related to plasma levels of bile acids in young adults. Metabolomics 2023, 19, 54. [CrossRef]

- Iljazovic, A.; Amend, L.; Galvez, E.J.C.; de Oliveira, R.; Strowig, T. Modulation of inflammatory responses by gastrointestinal Prevotella spp. – From associations to functional studies. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2021, 311, 151472. [CrossRef]

- Adamberg, S.; Adamberg, K. Prevotella enterotype associates with diets supporting acidic faecal pH and production of propionic acid by microbiota. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31134. [CrossRef]

- Betancur-Murillo, C. L.; Aguilar-Marín, S. B.; Jovel, J. Prevotella: A key player in ruminal metabolism. Microorganisms 2022, 11, 1. [CrossRef]

- Miele, L.; Valenza, V.; La Torre, G.; Montalto, M.; Cammarota, G.; Ricci, R.; Mascianà, R.; Forgione, A.; Gabrieli, M. L.; Perotti, G.; Vecchio, F. M.; Rapaccini, G.; Gasbarrini, G.; Day, C. P.; Grieco, A. Increased intestinal permeability and tight junction alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2009, 49, 1877–1887. [CrossRef]

- Del Chierico, F.; Nobili, V.; Vernocchi, P.; Russo, A.; De Stefanis, C.; Gnani, D.; Furlanello, C.; Zandonà, A.; Paci, P.; Capuani, G.; Dallapiccola, B.; Miccheli, A.; Alisi, A.; Putignani, L. Gut microbiota profiling of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and obese patients unveiled by an integrated meta-omics-based approach. Hepatology 2016, 65, 451–464. [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Wirth, U.; Koch, D.; Schirren, M.; Drefs, M.; Koliogiannis, D.; Nieß, H.; Andrassy, J.; Guba, M.; Bazhin, A. V.; Werner, J.; Kühn, F. The role of gut-derived lipopolysaccharides and the intestinal barrier in fatty liver diseases. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 2022, 26, 671–683. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Lee, T.H.; Cheng, M.J. Secondary Metabolites with Anti-Inflammatory Activities from an Actinobacteria Herbidospora daliensis. Molecules 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- Binda, C.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Rizzatti, G.; Gibiino, G.; Cennamo, V.; Gasbarrini, A. Actinobacteria: A relevant minority for the maintenance of gut homeostasis. Digestive and Liver Disease 2018, 50, 421-428. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.T.; Amos, G.C.A.; Murphy, A.R.J.; Murch, S.; Wellington, E.M.H.; Arasaradnam, R.P. Microbial imbalance in inflammatory bowel disease patients at different taxonomic levels. Gut Pathogens 2020, 12, 1. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, H.E.; Teterina, A.; Comelli, E.M.; Taibi, A.; Arendt, B.M.; Fischer, S.E.; Lou, W.; Allard, J.P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with dysbiosis independent of body mass index and insulin resistance. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 1466. [CrossRef]

- Boursier, J.; Mueller, O.; Barret, M.; Machado, M.; Fizanne, L.; Araujo-Perez, F.; Guy, C.D.; Seed, P.C.; Rawls, J.F.; David, L.A.; et al. The severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with gut dysbiosis and shift in the metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Hepatology 2016, 63, 764-775. [CrossRef]

- Long, Q.; Luo, F.; Li, B.; Li, Z.; Guo, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wu, W.; Hu, M. Gut microbiota and metabolic biomarkers in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Hepatol Commun 2024, 8. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Study group |

|---|---|

| DD | |

| Age, years, mean ± SD (min, max) | 54.34±11.99 (25, 74) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 72 (59.01) |

| Urban residence, n (%) | 81 (66.39) |

| Clinical data | |

| Co-morbidities, n (%) | 49 (40.16) |

| hypertension | 15 (12.29) |

| diabetes | 10 (8.19.3) |

| dyslipidemia | 85 (69.67) |

| obesity | 28 (22.95) |

| Paraclinical investigations, mean ± SD | |

| ALT, (U/L) | 30.09 ± 15.09 |

| AST, (U/L) | 25.60 ± 8.39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).