1. Introduction

As artificial intelligence (AI) and human-robot interaction technology advance, intelligent robotic systems are becoming increasingly prominent in human life. These robots have become essential in our everyday lives, functioning as helpers and even friends [

36]. They can sense and assist us through social interactions, aiming to enhance our mental and emotional wellness in the long run [

11]. These robots go beyond helping with high-precision, high-accuracy industrial tasks. Effective robots is a challenging study field that is currently in its early stages that focuses on analyzing human social-emotional signals to enhance HRI. For robots to assist human users physically and socially and to participate in and maintain ongoing engagements with people in a range of application areas that call for human-robot interaction, such as healthcare, education, and entertainment, among others, these skills are crucial. Understanding the fundamental mechanics of human behavior in everyday contexts and figuring out how to represent these systems for the embodiment of naturalistic, human-inspired behaviors in robots is the major problem for effective robotics. In order to effectively tackle this challenge [

5], it’s important to grasp the basic elements of social interaction, including nonverbal cues like how close people stand, how they position their bodies, the movements of their arms, hands, head, and face, where they look, moments of silence, and sudden vocal expressions. By interpreting these cues, we can build a deeper understanding of more complex concepts like initial perceptions, social roles, relationships between individuals, what they are paying attention to, synchronization, emotional states, personalities, and how engaged they are. This understanding is vital if we want to create social robots that are truly intelligent in their interactions with humans. Social robots are required to give a lifelike and engaging interactive experience that is tailored to each user to handle this difficulty. Individual variances in how people display emotional behaviors may arise owing to culture, gender, or personality, among other variables (Han and Jo).

So, Lifelong or Continual Learning (CL) is the ability of agents to continuously learn and adapt throughout their lifespan, collecting new information while maintaining the previously learned knowledge. This is especially advantageous for agents that deal with unpredictable and dynamic settings, such as those that include human relationships. [

27] A robot is a computer-controlled entity that interacts with the physical environment. It implies robots can’t revise their learning and improve on what it’s

∗Seoul National University of Science and Technology, South Korea

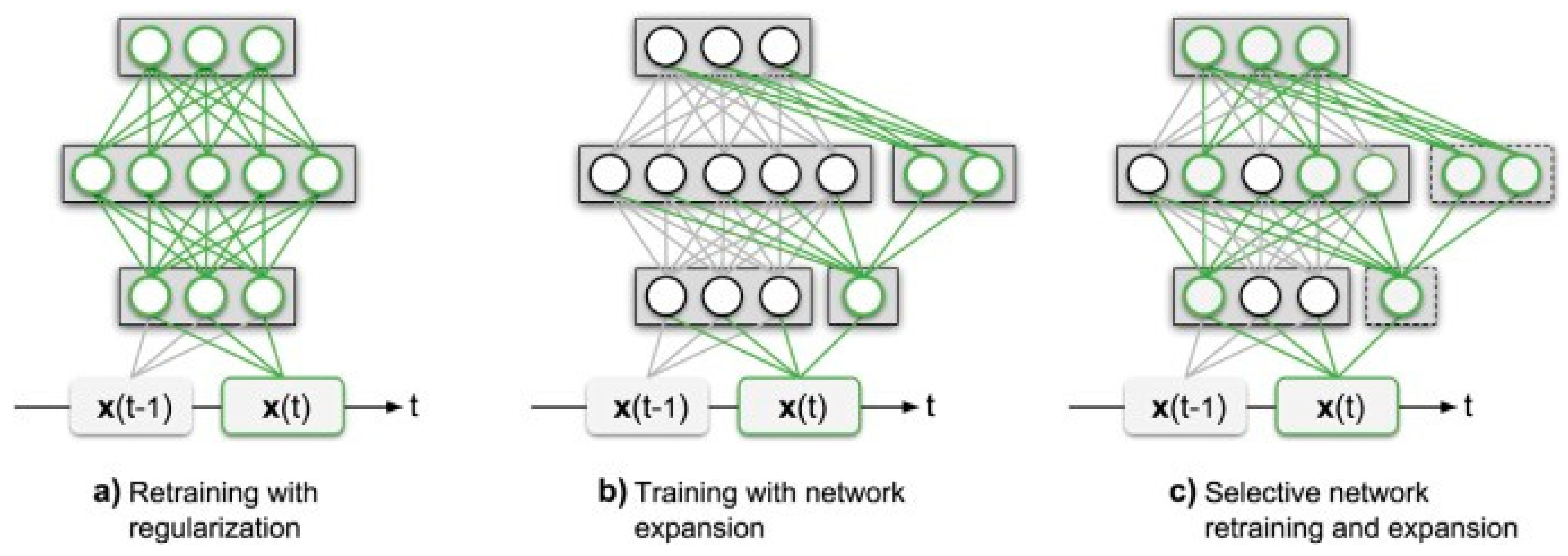

Figure 1.

schematic representation of ANN approaches for lifelong learning (a) retraining the network while applying regularization techniques to avoid catastrophic forgetting tasks that were learned before,. (b) extending the network without altering existing parameters to accommodate representation of new tasks, and (c) selectively retraining the network while allowing for potential expansion. [

32]. learned previously. Robotic systems are a suitable playground for CL algorithms because of their unique characteristics. Furthermore, robots have several limitations in terms of power or memory, which CL aims to alleviate through its approach to learning difficulties. Conversely, robots have a lot of information about their past experiences and can control how they interact with the things around them, which may aid in understanding causation and retrieving information from various types of sensors e.g. images, sound, and depth. This large amount of data helps to create strong patterns, which are really important for a successful CL algorithm. We may nearly infer that CL was created for robotics, which is correct. Nevertheless, nowadays, most CL techniques are not robotics-related and rely on image processing studies or virtual environments. The following section will cover the challenges of using continuous learning in robotic settings

Figure 1.

schematic representation of ANN approaches for lifelong learning (a) retraining the network while applying regularization techniques to avoid catastrophic forgetting tasks that were learned before,. (b) extending the network without altering existing parameters to accommodate representation of new tasks, and (c) selectively retraining the network while allowing for potential expansion. [

32]. learned previously. Robotic systems are a suitable playground for CL algorithms because of their unique characteristics. Furthermore, robots have several limitations in terms of power or memory, which CL aims to alleviate through its approach to learning difficulties. Conversely, robots have a lot of information about their past experiences and can control how they interact with the things around them, which may aid in understanding causation and retrieving information from various types of sensors e.g. images, sound, and depth. This large amount of data helps to create strong patterns, which are really important for a successful CL algorithm. We may nearly infer that CL was created for robotics, which is correct. Nevertheless, nowadays, most CL techniques are not robotics-related and rely on image processing studies or virtual environments. The following section will cover the challenges of using continuous learning in robotic settings

2. Current challenges in Continual Learning for Robotics

CL is useful for a robot. It learns about the world on its own and gradually builds up a collection of advanced skills and knowledge over time.

Table 1 summarizes the comprehensive discussion of the performance-based issues of continuous learning for robots and their solutions. The concerns described in

Table 2 are not all conceivable difficulties and their remedies, but we attempted to address as many known issues as possible as they arrived at the time of this study. However, a detailed explanation of the known methods is discussed as follows:

2.1. Robotic Hardware

When doing any robot experiment, the first hurdle to overcome is the hardware. Robots have a reputation for being unreliable and delicate. One of the most significant impediments to academics proposing innovative methods for robotics tasks is robot failure. They introduce inevitable delays into every experiment and are costly to repair. Furthermore, if the problem is in software instead of hardware then it’s not practical to automatically reset the robot. The personal assistance is frequently required such as guiding the robot back to its initial state or rescuing it from unrecoverable situations. Additionally, the cost of creating or purchasing a robot is rather high. Once the robot has been properly programmed, a new difficulty arises in the robot’s energy autonomy. When it comes to setting up experiments, is also a major challenge. It’s not easy to run lengthy experiments on a robot without recharge it by hand and making sure it doesn’t stop unexpectedly due to a loss of power or malfunction. [

27] Finally, because robots are embedded platforms, memory and compute resources are restricted, which must be properly maintained to avoid overflow. Since using robots for studies is not easy, there are not many methods in the literature for CL of robots. In the next section, the robotic settings, sampling, and labeling are discussed to utilize continuous learning systems.

2.2. Data Sampling/Labeling

A robot must acquire its training data in the actual world to learn how to do something for either for unknown or known environment. Data is the foundation for understanding and exploring the environment. This difficulty is identical to the one encountered by Reinforcement Learning algorithms. The capacity of babies to form objectives and explore the environment on their own, driven by intrinsic desire, is a critical component of lifelong learning. Self-supervised methods can also aid in the autonomous exploration of surroundings [

53]. self-Supervision [

19] and curiosity [

6] enable us to explore new information and create a foundation of understanding that can be used for current or upcoming tasks through transfer learning. Manipulation tasks such as holding objects [

41] onto them, can provide data which might be used immediately to learn in real-time or saved for future use. However outside assistance, annotations and improvement in learning algorithms are required [

34]. A robot must comprehend the items that make up its environment to comprehend it.

For this, the robot will need an approval from an external expert at some stage to make sure it’s learned about objects correctly. The robot needs labels for objects as the first kind of information [

12]. And if we want the robot to do something, we must provide the knowledge about the goals we have set for it as well as what it must avoid doing. This process is commonly achieved using a reward function that determines how credit is given. However, it can also be achieved through less specific guidelines like curiosity, self-supervision, or intrinsic motivation [

12]. Finally, the robot needs to know when the task changes and which task it should try to do. The job is labeled in this procedure, and the label is referred to as the task identifier. All these labels are optional, but they significantly aid and influence the learning process. Labeling has the disadvantage of being costly and time-consuming, slowing down learning algorithms. CL must devise efficient ways that make the most of the available labels for learning to address these two issues. Few-shot learning and active learning are two fields that seek to answer these problems. The former attempts to understand an idea based on a small number of data points. To optimize learning, active learning seeks to detect and pick the most important annotations. The constant learning settings could be more suitable for real-world applications in the field of robotics by integrating optimization processes in learning from few occurrences and decreasing the requirement for labeling. Furthermore, learning efficiency minimizes the likelihood of forgetting and memory degradation [

43].

2.3. Learning Algorithms Stability

Algorithms in continuous learning are exposed to several learning instances in succession. Some memory should be saved from each learning experience so that it is not forgotten later. The stability of learning algorithms becomes critical at this point: if just one learning event fails, the entire process may be tainted. Furthermore, if follow ongoing learning causality, unable to handle travel back in time and fix an issue that has already occurred. While one learning event is tainted, memories are tainted, and the model is degraded when learning subsequent tasks. To retain sane memory and weights, strong procedures to check or reject learning algorithm results are essential; nevertheless, it’s important to tackle the issue of deep learning models being unstable in order to overcome this drawback. For example, generative models work well for CL, but their unreliability may not be appropriate for this application [

26]. Reinforcement learning algorithms are known for being unstable and hard to predict, which is not good for learning over a long period.

3. Learning Approaches for Robotic Applications

Continuous learning has an almost limitless number of real-world applications. When learning algorithms deal with real-world data, they often encounter non-IID data. This applies to scenarios like robots learning tasks or vehicles adapting to new situations. Algorithms predicting trends from user behaviors or learning new information such as form advertisement or finance, also encounter non-static situations. The challenge arises when a pre-trained algorithm needs to learn new information without forgetting the previously learned knowledge. For example, the algorithm should be able to find new classes or identify anomaly without disturbing previous knowledge. Yet our focus here is on continuous learning in robotics. Most algorithms are tested on object recognition tasks involving both static and non-static objects. This makes sense since robots must understand their environment before acting. While a robot may be partially trained on initial data set but to enhance its capabilities, it is beneficial to incorporate new variations of previously learned objects like different perspectives, lighting conditions and encompassing diverse positions [

26].

To deal with such dynamic conditions, CL is essential. The first steps in this direction have been recommended in [

7]. Continual learning techniques to object segmentation and object identification may be found in [

28]. Other equally significant applications that have recently been addressed under continuous learning and robotics contexts include semantic segmentation and unsupervised object recognition [

26]. In simple terms, we are using a autonomous way for a robot to explore and learn in a complicated environment by staying curious and active [

1].

Furthermore,

Table 2 provides a more extensive discussion of the challenges of continuous learning for robots and proposed suggestions.

3.1. Reinforcement Learning

The distribution of data in reinforcement learning is determined by the controlled agent’s activities. This leads to a situation where the distribution of data keeps changing because the actions taken are not random. Similar strategies to those presented in CL are frequently used in reinforcement learning to learn across a nearly steady data distribution. Using an external memory to practice or remember things, which is also called experience or training memory bank, is one way to apply these strategies [

28]. The initial challenge in RL is to take out significant parts from incoming data and condense them into meaningful representations. The approaches used in both situations can be quite similar or even useful to each other. Learning how to represent states in RL is quite like representation-learning or unsupervised-learning representations for classifying things. The second challenge in RL is learning a strategy to complete a particular task. The problem of learning policies in CL is special because it often involves thinking about both the situation and the context. Recurrent neural networks are commonly used to manage context; however, this type of model has not yet been fully researched in CL, [

46] is a good example. For example, in

Figure 3, observed how in-state representation learning is applied to goal-based tasks in the field of robotics. The various tasks involving robots manipulating objects, like picking up and extending to reach things, are used as standards for comparison. A continuous problem arises in these tasks when attempting to learn patterns and strategies from data distributions that keep changing. However, it’s important to distinguish between the two issues since learning and transferring across activities are two distinct concerns. Comparable representations with different policies may be required for two activities, whereas similar policies may necessitate diverse representations. The number of proposed RL approaches is limited in the context of robotics than in video games or simulations. The low data efficiency of RL algorithms is one of the reasons for this. There are still many ways that effectively solve this problem [

1] or the problem can be tackled separately. For instance, one approach could involve learning a state representation initially, followed by policy learning. This way, the complexities can be managed in a more organized manner. Yet, a way to address this issue is by first applying the policy through simulation and then applying it to an actual robot in the real world [

16].

3.2. Model-based Learning

Only a few numbers of RL methods have been suggested in the context of robotics than in video games or simulations. The low data efficiency of RL algorithms is one of the reasons for this. There are still many ways that effectively solve this issue, either end-to-end or by splitting the two challenges to address them separately, e.g., learning a state representation first and then performing policy learning [

1]. Yet, understanding the policy in a simulation and then applying it to an actual robot [

18] is one solution to this problem. In robots, they’ve used inverse dynamics (online learning), but not with deep learning. They taught the dynamics of a robot step by step, both using semi-parametric dynamics and inverse approaches [

8]. This implies that a combination of parametric modeling techniques, utilizing rigid body dynamics equations, and non-parametric modeling techniques, employing incremental kernel approaches, are utilized. When utilized in case of involving non-parametric models, such as Gaussian processes that incorporate a kernel function then these models perform better than numerical methods in online situations [

8]. Some researchers used reinforcement learning to train a robot for navigation challenges. Recent research suggests a model-based approach could be crucial, especially when many trials aren’t possible [

50].

3.3. Towards autonomous agents

The challenge of learning sets of tasks in families of contexts throughout a lifetime is known as the lifelong learning issue. The issue of lifelong learning for robots that are permanently confined to one environment. This particular subset of lifelong learning situations is crucial to the study of autonomous agents. Several potential robot agents, such as artificial insects, industrial robot arms, or housekeeping robots, encounter a range of learning challenges in the same setting. These situations allow for the reuse of environmental information since trained action models, which are learned experimentally during problem- solving, maintain the same environment for each task. Consequently, the robot’s sensors might be used to detect how the world has altered. For the sake of simplicity, let’s suppose that the robot can precisely perceive the status of the environment. Learning control boils down to mastering a reactive controller, as was noted in the preceding section. Neural network learning methods, such as the Backpropagation training approach, can be used to simulate the environment if it is sufficiently predictable.

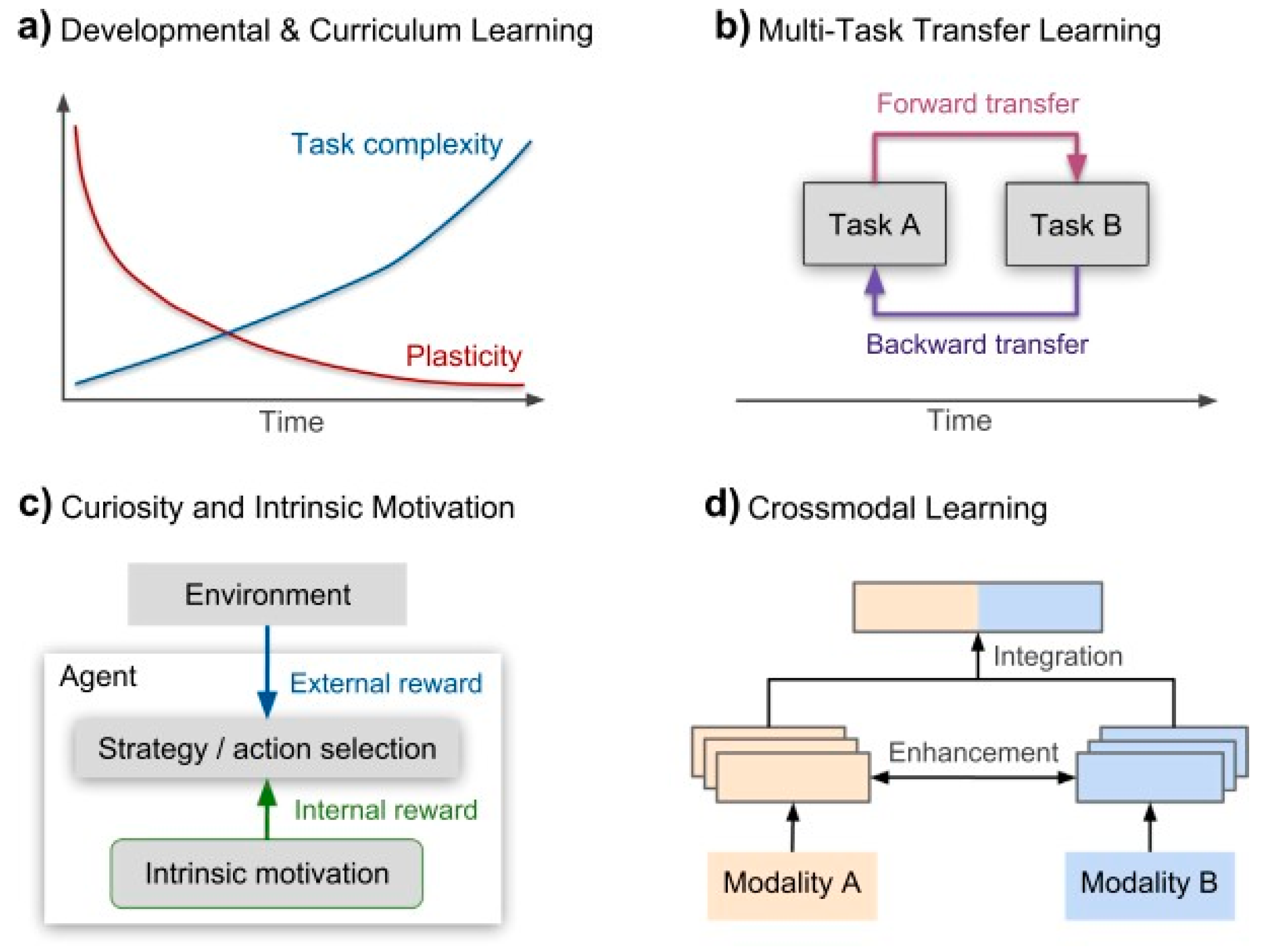

Given recent advancements in models designed for incremental learning tasks, as shown in

Figure 2, these models aim to reduce the problem of forgetting previously learned information. However, the datasets used to assess lifelong learning tasks are often simplified and don’t reflect the real-world complexity and uncertainty. Also, neural models are usually trained with randomly ordered or isolated data samples. This contrasts with how humans and animals quickly learn meaningful concepts and skills. Life- long learning involves more than just accumulating domain-specific knowledge. It enables transferring generalized skills and knowledge across tasks and domains, using multi-sensor information for complex cognitive functions. It’s unrealistic to expect artificial agents to have all prior knowledge needed for real- world performance [

59]. Consequently, In order for artificial agents to engage with complex contexts and comprehend and effectively interpret a constant flow of information, they must have a broader range of learning skills. The article concludes by suggesting that combining these approaches can improve current models for lifelong learning in artificial agents.

3.3. Curriculum and Developmental Learning

Learning and development involve a remarkable ability to learn all over life, and when compared to other species, they go through the longest development process to become mature. Youngsters are particularly susceptible to the consequences of their experiences within a certain developmental window. Often known as a sensitive or crucial time of growth, during which initial experiences hold significant sway, sometimes leading to permanent effects on behavior. Afterward, When the system stabilizes, flexibility gradually fades away while still retaining some of it for later adaptation and rearrangement at smaller scales [

45]. Researchers have looked into the fundamental processes of this particular learning

Figure 2.

Essential elements of CL agents to acquire knowledge and skills over extended periods in complex environments.[

32]. phases using contortionist models, especially when topographic neural maps are trained in two phases and self-organizing learning methods are employed to minimize levels of functional plasticity.

Figure 2.

Essential elements of CL agents to acquire knowledge and skills over extended periods in complex environments.[

32]. phases using contortionist models, especially when topographic neural maps are trained in two phases and self-organizing learning methods are employed to minimize levels of functional plasticity.

First, the neural network is trained with a higher learning rate and a larger neighborhood size, which aids the network’s initial organization. The parameters are then changed and decreased in the second phase to improve the details. This method has been used to simulate language learning, visual development and brain damage recovery. Recent research on deep neural networks indicates that the speed with which the networks learn is critical to how effectively they finally perform. In the first step, the neural map is trained with an increased learning rate and a significant spatial neighborhood size, enabling the network to achieve an early stage of topological organization. In the second phase, the learning rate and the neighborhood size are iterative and reduced for fine-tuning. Implementations have been made to develop models of visual development, language acquisition, and recovery from brain injuries. Recent research on deep neural networks has highlighted that the initial phase of rapid learning is crucial in determining the ultimate performance of these networks. During this phase, the network absorbs essential information and establishes foundational patterns that greatly influence its overall capabilities. For the distribution of resources among the several layers, which is determined by the initial input distribution, the initial few training epochs are crucial. After this critical period, the neural resources that were initially assigned can be redistributed during further learning stages. [

25].

Researchers have conducted experiments to examine how embedded agents can interact with their surroundings in real-time by utilizing developmental learning methods. Unlike traditional models that process information in batches, these agents acquire skills independently through their sensor-motor experiences. This emphasizes the significance of staged development in fostering cognitive abilities with minimal guidance. However, implementing developmental strategies in artificial learning systems is intricate, particularly when determining the appropriate stages for learning in dynamic environments. For example, in the context of predictive coding, the goal can be inferred by predicting an action through analyzing prediction errors. Generative models in active inference aid in comprehending the selection of data in uncertain environments by integrating action and perception. Nevertheless, the systematic definition of developmental stages based on innate structure, embodiment, and active inference remains ambiguous. Humans and animals exhibit superior learning outcomes when tasks gradually increase in difficulty and possess meaningful organization. The concept of curriculum learning, where tasks become progressively harder, has been shown to improve neural network training efficiency. This has influenced other fields like robotics and newer machine learning techniques. When conducting experiments on simpler datasets such as MNIST, it has been observed that curriculum learning operates similarly to unsupervised pre-training, leading to improved generalization and quicker convergence. However, the effectiveness of curriculum learning relies on the progression of tasks and assumes a singular axis of difficulty. It is important to also consider intrinsic motivation, were signals of learning progress direct exploration. Curriculum methods represent a type of transfer learning that leverages initial task knowledge to guide the acquisition of more complex tasks. [

64].

3.4. Transfer learning

Transfer learning involves using knowledge gained in one area to address a new problem in a different area [

24]. Backward transfer looks at how the ongoing task (T-II) affects a former task (T-I), while forward transfer explores how learning a task (T-I) affects performing a future task (T-II). This makes transfer learning valuable for extracting general insights from specific examples, especially when multiple learning tasks are available. Despite its inherent value, machine learning and autonomous agents continue to face challenges when it comes to the implementation of transfer learning [

57]. The precise brain mechanisms underlying high-level transfer learning are not yet fully understood. However, there is ongoing debate suggesting that the transfer of abstract information may occur through the utilization of conceptual representations that store relationships unaffected by specific individuals, objects, or scene parts [

54]. Zero-shot learning and one-shot learning methods aim to perform well on new tasks. Nevertheless, they do not tackle the problem of forgetting previously learned information or catastrophic forgetting when facing new tasks [

38] [

58]. In 1997, Ring proposed an innovative approach to lifelong learning through the utilization of transfer learning. He illustrated this concept by employing a hierarchical neural network capable of solving increasingly complex tasks over time. By expanding the number of neurons and incorporating a broader contextual understanding of action occurrences, the network exhibited effective task learning. In more recent times, advanced deep learning techniques have also focused on addressing lifelong transfer learning challenges across diverse domains. As an example, in [

65] the idea of progressive neural networks was introduced. This involves transferring knowledge from simulated environments to real-world scenarios. In [

62], the goal is to teach a physical robot manipulator how to perform tasks using visual data. The learning process includes developing policies that connect pixels to actions, even with limited rewards, to control the robot. To facilitate the reuse and transfer of knowledge across tasks, [

35] proposed a hierarchical deep reinforcement learning method characterized as a collection of skills and skill distillation. The efficacy of the approach was confirmed through training an agent to complete tasks within the Minecraft video game. However, a prerequisite for this technique is the pre-training of skill networks, as they cannot be simultaneously taught alongside the overarching architecture. To tackle the problem of catastrophic forgetting and enhance the ability to apply past learning to new tasks, researchers introduced the Gradient Episodic Memory (GEM) model. This innovative approach grasps the connections between different distributions or tasks, allowing it to forecast outcomes for both familiar and novel tasks without needing specific task information [

29].

3.5. Multi-sensor learning

The brain’s capacity to integrate multi-sensor information is a critical trait that allows it to interact with the world in a cohesive, resilient, and efficient manner. Different types of sensors, like those for vision and hearing, can work together to create combined or improved representations. This is important for understanding and reacting to the environment. When different sensor inputs are processed together, it helps us recognize things and make decisions based on what we’ve learned before. Learning from multiple sensors is a changing process affected by short-term and long-term factors [

13]. Perceptual representations that are learned and link progressively complicated information qualities at a greater level e.g., semantic concurrency. Multi-sensor integration perceptive mechanisms become more complex. beginning with minimal processing skills throughout development and gradually specializing in increasingly difficult cognitive tasks sensorimotor experience is used to perform functions. Modeling multi-modal learning from a computational standpoint can be beneficial for a variety of reasons. Firstly, the design of multi-sensor functions is aimed at providing consistent responses even when faced with uncertain sensory data. This is achieved by using models of causal inference to resolve conflicts between different sensory inputs. For example, when audio and visual information doesn’t match, these models help in making sense of the situation. Secondly, the information in one form of sensory input is used to reconstruct the missing information in another form. Moon, Kim, and Wang [

3] proposed the utilization of multi-modal processing to address an audio-visual recognition challenge, where information from one modality is transferred to an- other. They suggested that abstract representations derived from a network encoding the source modality can be employed to refine the network in the target modality. This approach helps mitigate the issue of imbalanced data availability in the target modality. Additionally, they introduced a deep architecture that models cross-modal expectation learning. After a training phase using multi-modal audiovisual in- formation, uni-sensory network channels can reproduce the predicted output from the other modality. Furthermore, attention processes play a crucial role in handling significant information within complex contexts and effectively trigger goal-directed actions from continuous streams of multi-sensory input, particularly in lifelong learning scenarios. To constantly influence perception, cognition, and behavior

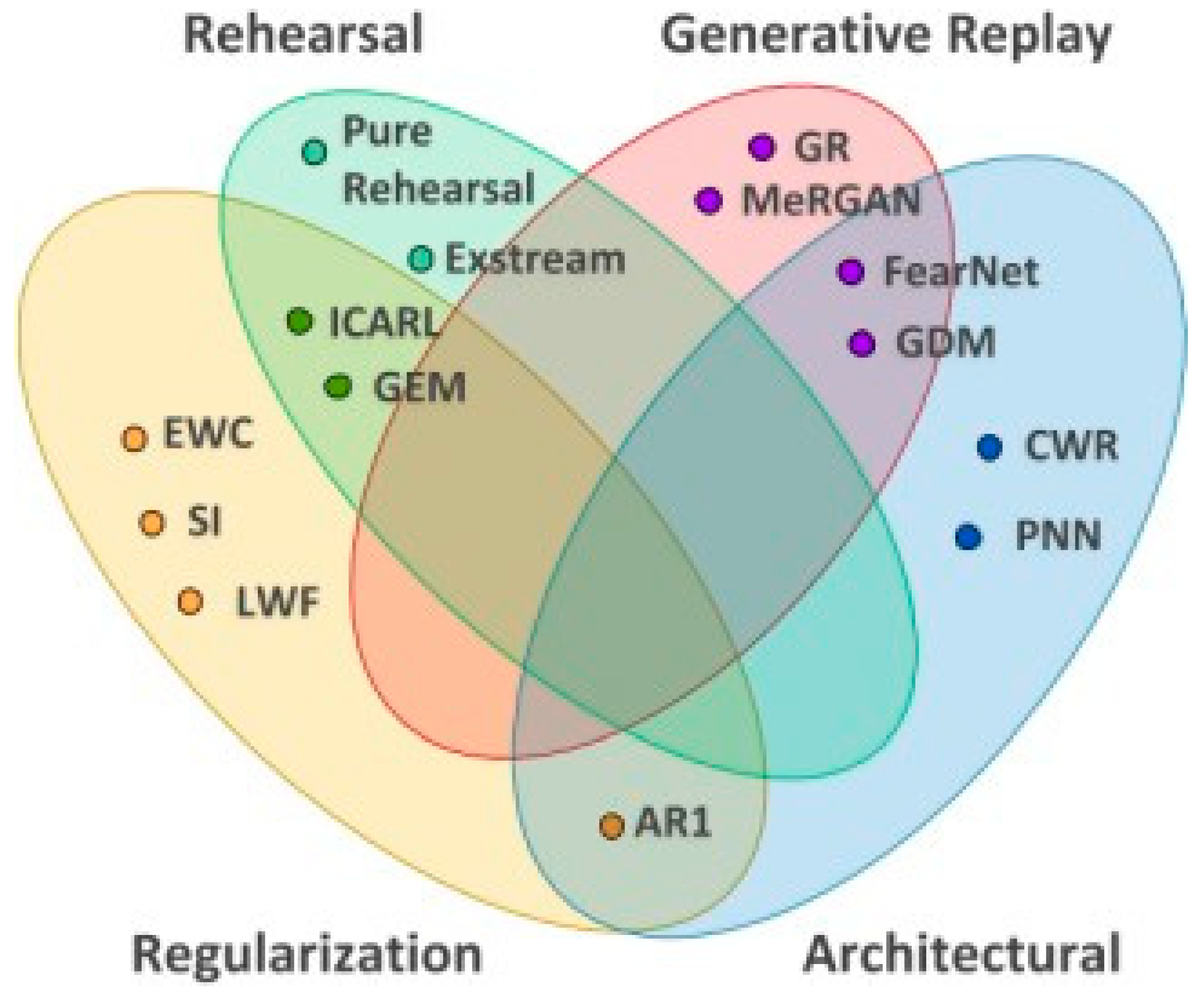

Figure 3.

Various CL strategies in relation to the four approaches [

32]. in autonomous agents, these mechanisms can be represented by incorporating a combination of external properties from cross-modal input, acquired associations and correspondences between different modalities, and internally generated expectations [

66].

Figure 3.

Various CL strategies in relation to the four approaches [

32]. in autonomous agents, these mechanisms can be represented by incorporating a combination of external properties from cross-modal input, acquired associations and correspondences between different modalities, and internally generated expectations [

66].

3.6. Modular Continuous Learning

The Modular Continuous Learning Framework (MCLF) is designed to facilitate autonomous and open- ended learning in robots. The MCLF comprises three main components: a Goal Discovery Module, a Goal Management Module, and a Learning Module. The Goal Discovery Module autonomously identifies objectives for the robot, while the Goal Management Module prioritizes and organizes these objectives. The Learning Module utilizes reinforcement learning algorithms to acquire the necessary skills to achieve the identified goals. [

14]

The autonomous behavior in robots and underscores the necessity of a goal management module for effective prioritization of goals is the significance of modular approach. It also highlights the flexibility of the framework, permitting the utilization of various clustering algorithms for goal discovery and reinforcement learning algorithms for goal attainment. The study validates the comprehensive nature of the proposed framework by meeting three essential criteria: goal discovery, goal management, and goal learning. The primary contribution lies in presenting a continuous learning framework that autonomously discovers goals, stores and recalls learned knowledge, and learns to achieve self-discovered goals in an open-ended manner. The framework facilitates autonomous and flexible learning for robots, enabling them to adapt to dynamic environmental changes. The experimental validation confirms the effectiveness of the MCLF in promoting autonomous and open-ended learning in robots. The robot, when introduced to a new environment, autonomously formulated and acquired new goals, the Modular Continuous Learning Framework can continually learn and adapt in diverse settings.

3.7. Hybrid based Learning

Models trained using the previously mentioned methods are unable to scale up as the complexity of the data and tasks rises. This is caused by memory depletion from storing samples for practice or capacity overload caused by weights frozen from previously learned jobs [

2]. This issue may be solved by allocating more neural resources to enhance the capacity, either by enlarging the trainable parameters or letting the architecture expand to accommodate the heightened complexity as explained in

Figure 3 The model is expanded by adding more neurons or network layers [

17] as and when necessary, starting with a very simple design. It is possible to manage the model’s performance, based on how well it performs on tasks that have been previously learned, how the brain responds to data samples, or how well the model uses its existing set of parameters to complete new tasks. These models are efficient in preventing catastrophic forgetting and enabling ongoing information learning [

9], despite the additional difficulty of adding new brain resources.

In addition, in

Table 2 the learning methodologies, the associated difficulties, and potential solutions are described in detail. This research made every effort to condense and organize the advice as effectively as it could.

Table 2.

A summary of the constraints for learning techniques, as well as their recommended solutions.

Table 2.

A summary of the constraints for learning techniques, as well as their recommended solutions.

| LearningApproaches |

Dilemma/Challenges |

Proposed Solutions |

Reference |

| Reinforcement |

Sample inefficiency, Exploitation |

Experience Replay, Dual |

[68], [42],[21], |

| Learning |

dilemma, Catastrophic |

Memory Architectures, Actor- |

[39],[56] |

| |

Forgetting |

Critic Architectures, Continual |

|

| |

|

Learning Frameworks |

|

| Model-based |

Model Inaccuracy, Model Mis- |

Model Regularization, Un- |

[44],[15],[33], |

| Learning |

match, Model Complexity |

Certainty Estimation, Model |

[67], [23] |

| |

|

Selection, Continual Learning |

|

| |

|

Frameworks |

|

| Developmental |

Slow Learning, Task Interference, |

Curriculum Design, Self-paced |

[23], [47], [55], |

| and Curriculum |

Limited Capacity |

Learning, Dynamic Learning |

[69], [4], [51] |

| Learning |

|

Rate, Continual Learning |

|

| |

|

Frameworks |

|

| Transfer Learning |

Negative Transfer, Domain |

Domain Adaptation, Meta- |

[70], [30], [37], |

| |

Shift, Task Distribution Mis- |

learning, Shared Representations |

[49], [67], [51] |

| |

match |

Continual Learning |

|

| |

|

Frameworks |

|

| Multisensory |

Sensorimotor Integration, Sensor |

Sensor Fusion, Multimodal |

[31], [10], [40] |

| Learning |

Mismatch, Redundancy |

Learning, Transfer Learning, |

|

| |

|

Continual Learning Frame- |

|

| |

|

works |

|

| Hybrid-based |

Model-Free and Model-Based |

Hybrid Architecture Design, |

[61], [20], [63], |

| Learning |

Tradeoffs, Sample Efficiency, |

Model Compression, Transfer |

[60], [52], [48] |

| |

Scalability |

Learning, Continual Learning |

|

| |

|

Frameworks |

|

4. Ablation Study

Multiple concepts emerge as crucial for accurately characterizing learning algorithms within the context of continual learning (CL), facilitating fair comparisons between them, and enabling their transfer from simulated environments to real-world autonomous systems and robotics.

First and foremost,

Table 2 determines the specific challenge that needs to be tackled as well as the restrictions that exist. The methodology should aid in the classification of various environments. This formal phase aids in determining the best path to take and recognizing parallels with other situations.

Second, in the same vein as defining what to learn, defining the degree of supervision that can provide to the learning algorithm is critical e.g. data distribution and the number of instances/classes of each task. Finally, it’s critical to specify exactly what the algorithm’s expected performance is. The collection of metrics and benchmarks should aid in defining and expressing the dimension of assessment for crucial qualities to consider in the construction of embodied agents that learn continuously. A series of recommendations for more concrete indicators of what we think is worth evaluating while developing a CL method is explained in the discussion.

Reinforcement learning has its own set of difficulties, including sample inefficiency and the problem of catastrophic forgetting, which may be resolved with dual memory architectures and continuous learning. Model-based learning has some drawbacks, such as accuracy problems caused by complicated models being used with simple models, which may be reduced by employing regularization and the optimum model choice. Self-paced and dynamic learning rates can address the poor learning and restricted capacity challenges in curriculum learning. Another well-known approach is transferring learning, which has several known issues including negative transfer, domain shift, and task distribution. Domain adaptation and shared learning are the suggested fixes, and both are highly good at transferring knowledge. Hybrid learning is now the finest teaching technique available. The most effective learning strategies to date are compression and hybrid continual learning model designs, which overlap the weaknesses and strengths of existing learning strategies, as summarized in

Table 2.

4.1. Opportunities for continual learning in robotics

In this discussion, the focus is on the symbiotic relationship between robots and Continual Learning (CL) algorithms. A robot, being an agent engaged in real-world interactions, lacks the ability to revisit and improve past learning instances, a fundamental characteristic setting it apart from other learning models. These inherent limitations of robotic systems render them an ideal scenario for exploring and optimizing CL algorithms. Given the constraints in power and memory often encountered in robotic platforms, CL endeavors to enhance learning methodologies to align with these limitations.

Robots possess a wealth of experiential data due to their direct interaction with the environment, presenting a promising avenue for grasping the concept of causality and extracting diverse knowledge from various sensory inputs such as images, sound, and depth. Leveraging this comprehensive experiential data allows for the creation of robust representations essential for effective CL algorithm performance. Despite the apparent compatibility of CL with robotics, contemporary CL approaches primarily concentrate on domains unrelated to robotics, notably emphasizing experiments in image processing or simulated environments.

In conclusion, the present status of continuous learning is discussed, and the suggested framework is used to demonstrate several techniques. The most recent assessment techniques and benchmarks for continuous learning algorithms are outlined. This article urges the AI community to improve the categorization and comparative analysis of techniques, while also adapting to the challenges encountered in the modern industry. Robotics and machine learning are two disciplines that are developing quickly. To comprehend one another and gain success, it is essential to discover solutions that would facilitate transfer across the two areas, as this paper summarizes.

5. Conclusion

Artificial systems and autonomous agents that interact with real-world data, which is frequently non- stationary and temporally correlated, encounter a challenging component: lifelong learning. The brain is still the best model for lifelong learning, making learning models with biological inspiration an enticing choice. Even when biological desiderata are ignored, the overall idea of structural plasticity is widely employed across the machine learning literature and constitutes a viable answer to lifelong learning. To mitigate catastrophic forgetting and interference, various computational solutions have been proposed, involve controlling the inherent flexibility of the system to maintain learned information, and adapting by adding new neurons or network layers to handle new information, and employing complementary learning networks that leverage past experiences. Despite significant advancements, contemporary models of lifelong learning still face limitations in terms of adaptability, resilience, and scalability.

The most common lifelong learning deep and shallow learning models are supervised and rely on vast quantities of annotated data acquired in controlled contexts. Autonomous agents or robots operating in extremely dynamic, unstructured contexts cannot benefit from such a domain-specific training approach. To combine several techniques that include a range of elements found and explained in terms of challenges and their concerning solutions. The effectiveness of the model for later learning tasks may be improved by empirically identifying the most effective neural network design and initial patterns of connection. The utilization of curriculum and transfer learning methods is vital for leveraging previously acquired information and skills to solve problems in new domains by sharing both low-level and high-level representations. Intrinsic motivation-based approaches play a crucial role in enabling autonomous learning agents and robots to generate their own objectives, facilitating an iterative process of exploration and the gradual acquisition of increasingly complex abilities. Additionally, integration is a fundamental characteristic of autonomous agents and robots operating in dynamic and noisy environments, enabling them to learn and behave reliably even in uncertain conditions.

References

- Mohammed, Abdou; et al. “End-to-end deep conditional imitation learning for autonomous driving”. In: 2019 31st International Conference on Microelectronics (ICM). IEEE. 2019, pp. 346–350.

- Ajay Babu and S Ashok. “Comparison of T source inverter and voltage source inverter based drives for parallel hybrids”. In: 2014 International Conference on Advances in Green Energy (ICAGE). IEEE. 2014, pp. 138–143.

- Pablo Barros and Alessandra Sciutti. “Across the Universe: Biasing Facial Representations Toward Non-Universal Emotions With the Face-STN”. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 103932–103947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdalena Biesialska, Katarzyna Biesialska, and Marta R Costa-Jussa. “Continual lifelong learning in natural language processing: A survey”. In: arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.09823 (2020).

- Laura, Bishop; et al. “Social robots: The influence of human and robot characteristics on acceptance”. Paladyn, Journal of Behavioral Robotics 2019, 10, 346–358. [Google Scholar]

- Laura, Bishop; et al. “Social robots: The influence of human and robot characteristics on acceptance”. Paladyn, Journal of Behavioral Robotics 2019, 10, 346–358. [Google Scholar]

- Raffaello, Camoriano; et al. “Incremental robot learning of new objects with fixed update time”. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE. 2017, pp. 3207– 3214.

- Raffaello, Camoriano; et al. “Incremental semiparametric inverse dynamics learning”. In: 2016 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation (ICRA). IEEE. 2016, pp. 544–550.

- Tommaso, Cavallari; et al. “On-the-fly adaptation of regression forests for online camera relocali- sation”. In: Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2017, pp. 4457–4466.

- Vinay, Chamola; et al. “Brain-computer interface-based humanoid control: A review”. Sensors 2020, 20, 3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikhil, Churamani; et al. “Affect-driven learning of robot behaviour for collaborative human-robot interactions”. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2022, 9, 717193. [Google Scholar]

- C´eline, Craye; et al. “Exploring to learn visual saliency: The RL-IAC approach”. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2019, 112, 244–259. [Google Scholar]

- Suvi Lasan De Silva and Nalaka Dissanayaka. “Multisensory learning approach to create a sen- tence learning platformfor students with autism spectrum disorder”. In: 2018 3rd International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT). IEEE. 2018, pp. 1–5.

- Paresh Dhakan et al. “Modular Continuous Learning Framework”. In: 2018 Joint IEEE 8th Inter- national Conference on Development and Learning and Epigenetic Robotics (ICDL-EpiRob). 2018, pp. 107–112. [CrossRef]

- Linsen, Dong; et al. “Intelligent trainer for dyna-style model-based deep reinforcement learning”. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2020, 32, 2758–2771. [Google Scholar]

- Chelsea, Finn; et al. “Deep spatial autoencoders for visuomotor learning”. In: 2016 IEEE Interna- tional Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE. 2016, pp. 512–519.

- S´ebastien, Forestier; et al. “Intrinsically motivated goal exploration processes with automatic cur- riculum learning”. The Journal of Machine Learning Research 2022, 23, 6818–6858. [Google Scholar]

- Dhiraj Gandhi, Lerrel Pinto, and Abhinav Gupta. “Learning to fly by crashing”. In: 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE. 2017, pp. 3948–3955.

- Yuan Gao, Xiaojuan Sun, and Chao Liu. “A General Self-Supervised Framework for Remote Sensing Image Classification”. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Huang; et al. “Learning physical human–robot interaction with coupled cooperative primitives for a lower exoskeleton”. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2019, 16, 1566–1574. [Google Scholar]

- Christos Kaplanis, Murray Shanahan, and Claudia Clopath. “Continual reinforcement learning with complex synapses”. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR. 2018, pp. 2497– 2506.

- James, Kirkpatrick; et al. “Overcoming catastrophic forgetting in neural networks”. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 2017, 114, 3521–3526. [Google Scholar]

- Taisuke Kobayashi and Toshiki Sugino. “Reinforcement learning for quadrupedal locomotion with design of continual–hierarchical curriculum”. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2020, 95, 103869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton Koval, Sina Sharif Mansouri, and Christoforos Kanellakis. “Machine learning for ARWs”. In: Aerial Robotic Workers. Elsevier, 2023, pp. 159–174.

- Dedi, Kuswandi; et al. “Development Curriculum e-Learning: Student Engagement and Student Readiness Perspective”. In: 2021 7th International Conference on Education and Technology (ICET). IEEE. 2021, pp. 156–160.

- Timoth´ee, Lesort; et al. “Generative models from the perspective of continual learning”. In: 2019 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE. 2019, pp. 1–8.

- Timoth´ee, Lesort; et al. “State representation learning for control: An overview”. Neural Networks 2018, 108, 379–392. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Liu; et al. “Incremental learning with neural networks for computer vision: a survey”. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 4557–4589. [Google Scholar]

- David Lopez-Paz and Marc’Aurelio Ranzato. “Gradient episodic memory for continual learning”. In: Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

- Saeid, Motiian; et al. “Few-shot adversarial domain adaptation”. In: Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

- Prajval Kumar, Murali; et al. “Deep active cross-modal visuo-tactile transfer learning for robotic object recognition”. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2022, 7, 9557–9564. [Google Scholar]

- German I, Parisi; et al. “Continual lifelong learning with neural networks: A review”. Neural networks 2019, 113, 54–71. [Google Scholar]

- German I, Parisi; et al. “Continual lifelong learning with neural networks: A review”. Neural networks 2019, 113, 54–71. [Google Scholar]

- German I, Parisi; et al. “Lifelong learning of spatiotemporal representations with dual-memory re- current self-organization”. Frontiers in neurorobotics 2018, 12, 78. [Google Scholar]

- Shubham, Pateria; et al. “End-to-end hierarchical reinforcement learning with integrated subgoal dis- covery”. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2021, 33, 7778–7790. [Google Scholar]

- Tony J Prescott and Julie M Robillard. “Are friends electric? The benefits and risks of human-robot relationships”. In: Iscience 24.1 (2021).

- Haozhi Qi et al. “Learning long-term visual dynamics with region proposal interaction networks”. In: arXiv preprint arXiv:2008.02265 (2020).

- Shafin Rahman, Salman Khan, and Fatih Porikli. “A unified approach for conventional zero-shot, generalized zero-shot, and few-shot learning”. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2018, 27, 5652–5667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, Ritter; et al. “Been there, done that: Meta-learning with episodic recall”. In: International conference on machine learning. PMLR. 2018, pp. 4354–4363.

- Yara Rizk, Mariette Awad, and Edward W Tunstel. “Cooperative heterogeneous multi-robot sys- tems: A survey”. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2019, 52, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cl´ement, Rolinat; et al. “Learning to model the grasp space of an underactuated robot gripper using variational autoencoder”. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2021, 54, 523–528. [Google Scholar]

- Tom, Schaul; et al. “Universal value function approximators”. In: International conference on ma- chine learning. PMLR. 2015, pp. 1312–1320.

- Ju¨rgen Schmidhuber. Formal theory of creativity, fun, and intrinsic motivation (1990–2010). IEEE transactions on autonomous mental development 2010, 2, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruan Al-Shedivat et al. “Continuous adaptation via meta-learning in nonstationary and com- petitive environments”. In: arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.03641 (2017).

- Tsuyoshi Shimada. “A locally active unit for neural networks and its learning method”. In: Pro- ceedings of 1993 International Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN-93-Nagoya, Japan). Vol. 1. IEEE. 1993, pp. 359–362.

- Shagun Sodhani, Sarath Chandar, and Yoshua Bengio. “Toward training recurrent neural networks for lifelong learning”. In: Neural computation 32.1 (2020), pp. 1–35.

- Siddharth Swaroop et al. “Improving and understanding variational continual learning”. In: arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.02099 (2019).

- Lei Tai, Giuseppe Paolo, and Ming Liu. “Virtual-to-real deep reinforcement learning: Continuous control of mobile robots for mapless navigation”. In: 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE. 2017, pp. 31–36.

- Lazar, Valkov; et al. “Houdini: Lifelong learning as program synthesis”. In: Advances in neural information processing systems 31 (2018).

- Herke Van, Hoof; et al. “Stable reinforcement learning with autoencoders for tactile and visual data”. In: 2016 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems (IROS). IEEE. 2016, pp. 3928–3934.

- Tom Veniat, Ludovic Denoyer, and Marc’Aurelio Ranzato. “Efficient continual learning with mod- ular networks and task-driven priors”. In: arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.12631 (2020).

- Yonghao, Wang; et al. “Joint Latency-Oriented, Energy Consumption, and Carbon Emission for Space-Air-Ground Integrated Network with New Designed Power Technology”. In: (2023).

- Chenshen, Wu; et al. “Memory replay gans: Learning to generate new categories without forgetting”. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 31 (2018).

- Shengshuai, Wu; et al. “Path planning for autonomous mobile robot using transfer learning-based Q-learning”. In: 2020 3rd International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS). IEEE. 2020, pp. 88–93.

- Houhong, Xiang; et al. “Improved de-multipath neural network models with self-paced feature-to- feature learning for DOA estimation in multipath environment”. IEEE Transactions on Vehic- ular Technology 2020, 69, 5068–5078. [Google Scholar]

- Annie Xie, James Harrison, and Chelsea Finn. “Deep reinforcement learning amidst continual structured non-stationarity”. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR. 2021, pp. 11393–11403.

- Dongsheng Xu, Peng Qiao, and Yong Dou. “Aggregation transfer learning for multi-agent rein- forcement learning”. In: 2021 2nd International Conference on Big Data & Artificial Intelligence & Software Engineering (ICBASE). IEEE. 2021, pp. 547–551.

- Xiaofeng, Xu; et al. “End-to-end supervised zero-shot learning with meta-learning strategy”. In: 2021 8th International Conference on Information, Cybernetics, and Computational Social Systems (ICCSS). IEEE. 2021, pp. 326–330.

- Zhenbo Xu, Haimiao Hu, and Liu Liu. “Revealing the real-world applicable setting of online con- tinual learning”. In: 2022 IEEE 24th International Workshop on Multimedia Signal Processing (MMSP). IEEE. 2022, pp. 1–5.

- Zhongwen, Xu; et al. “Meta-gradient reinforcement learning with an objective discovered online”. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 15254–15264. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaoxian, Yang; et al. “An information fusion approach to intelligent traffic signal control using the joint methods of multiagent reinforcement learning and artificial intelligence of things”. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2021, 23, 9335–9345. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui Muhammad Yasir and Hyunsik Ahn. “Faster Metallic Surface Defect Detection Using Deep Learning with Channel Shuffling”. In: CMC-COMPUTERS MATERIALS & CONTINUA 75.1 (2023), pp. 1847–1861.

- Yang, Yu; et al. “Automated damage diagnosis of concrete jack arch beam using optimized deep stacked autoencoders and multi-sensor fusion”. In: Developments in the Built Environment 14 (2023), p. 100128.

- Kevin Kam Fung Yuen. “Towards research-led teaching curriculum development for machine learn- ing algorithms”. In: 2017 IEEE 6th International Conference on Teaching, Assessment, and Learn- ing for Engineering (TALE). IEEE. 2017, pp. 478–481.

- Fan Zhang. “Learning Unsupervised Side Information for Zero-Shot Learning”. In: 2021 Inter- national Conference on Signal Processing and Machine Learning (CONF-SPML). IEEE. 2021, pp. 325–328.

- Huaying, Zhang; et al. “Cross-Modal Image Retrieval Considering Semantic Relationships With Many-to-Many Correspondence Loss”. In: IEEE Access 11 (2023), pp. 10675–10686.

- Lulu, Zheng; et al. “Episodic multi-agent reinforcement learning with curiosity-driven exploration”. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (2021), pp. 3757–3769.

- Zhaohui, Zheng; et al. “Distance-IoU loss: Faster and better learning for bounding box regression”. In: Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence. Vol. 34. 07. 2020, pp. 12993–13000.

- Tianyi Zhou, Shengjie Wang, and Jeff Bilmes. “Curriculum learning by optimizing learning dynam- ics”. In: International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics. PMLR. 2021, pp. 433– 441.

- Zhuangdi, Zhu; et al. “Transfer learning in deep reinforcement learning: A survey”. In: IEEE Trans- actions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).