Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Measurement Tools

2.4.1. Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI)

2.4.2. Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS)

2.4.3. Brief Resilience Scale (BRS)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Štěpánek, L.; Nakládalová, M.; Janošíková, M.; et al. Prevalence of Burnout in Healthcare Workers of Tertiary-Care Hospitals during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey from Two Central European Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tselebis, A.; Pachi, A. Primary Mental Health Care in a New Era. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikaras, C.; Zyga, S.; Tsironi, M.; et al. Assessment of insomnia and fatigue in nursing staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nosileftiki 2023, 62, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hovland, I.S.; Skogstad, L.; Diep, L.M.; et al. Burnout among intensive care nurses, physicians and leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national longitudinal study. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhart Sasangohar, F.; Jones, S.L.; Masud, F.N.; et al. Provider burnout and fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned from a high-volume intensive care unit. AnesthAnalg 2020, 131, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, R.G.; Bartlett, R. Healthcare worker resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review. Journal of Nursing Management 2021, 29, 2329–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firew, T.; Sano, E.D.; Lee, J.W.; et al. Protecting the front line: a cross-sectional survey analysis of the occupational factors contributing to healthcare workers' infection and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e042752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preti, E.; Di Mattei, V.; Perego, G.; et al. The Psychological Impact of Epidemic and Pandemic Outbreaks on Healthcare Workers: Rapid Review of the Evidence. Current Psychiatry Reports 2020, 22, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahrami, H.A.; Alhaj, O.A.; Humood, A.M.; et al. Sleep disturbances during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2022, 62, 101591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarafis, P.; Rousaki, E.; Tsounis, A.; et al. The impact of occupational stress on nurses' caring behaviors and their health related quality of life. BMC Nursing 2016, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnsten, A.F.T.; Shanafelt, T. Physician Distress and Burnout: The Neurobiological Perspective. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2021, 96, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Greenglass, E.R. Introduction to special issue on burnout and health. Psychology & Health 2001, 16, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada, M.E.; Moreno, R.; Mejías, M.Z.; et al. Job satisfaction and burnout syndrome in the nursing staff of the Instituto Autónomo Hospital Universitario Los Andes, Mérida, Venezuela. Rev. Fac. Nac 2005, 23, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.L.; Wu, M.P.; Ho, C.H.; Wang, J.J. Risks of treated anxiety, depression, and insomnia among nurses: A nationwide longitudinal cohort study. PloS ONE 2018, 13, e0204224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.L.; Li, Y.M.; Chang, E.T.; Lai, H.L.; Wang, W.H.; Wang, S.C. Sleep disorder in Taiwanese nurses: a random sample survey. Nursing & Health Sciences 2011, 13, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanshenas Ghazwin, M.; Kavian, M.; Ahmadloo, M.; et al. The Association between Life Satisfaction and the Extent of Depression, Anxiety and Stress among Iranian Nurses: A Multicenter Survey. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry 2016, 11, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.P.; Peng, Y.X. Influence of rotating shifts and fixed night shifts on sleep quality of nurses of different ages: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Chronobiology International 2021, 38, 1384–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger-Brown, J.; Rogers, V.E.; Trinkoff, A.M.; et al. Sleep, sleepiness, fatigue, and performance of 12-hour-shift nurses. Chronobiology International 2012, 29, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Membrive-Jiménez, M.J.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Suleiman-Martos, N.; et al. Relation between Burnout and Sleep Problems in Nurses: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consensus Conference Panel; Watson, N.F.; Badr, M.S.; et al. Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the Recommended Amount of Sleep for a Healthy Adult: Methodology and Discussion. Sleep 2015, 38, 1161–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, C.; Upton, D.; Ranse, K.; et al. Nurses' resilience and the emotional labour of nursing work: An integrative review of empirical literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2017, 70, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.L.; Brannan, J.D.; De Chesnay, M. Resilience in nurses: an integrative review. Journal of Nursing Management 2014, 22, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAllister, M.; McKinnon, J. The importance of teaching and learning resilience in the health disciplines: a critical review of the literature. Nurse Education Today 2009, 29, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, L.J.; Revell, S.H. Resilience in nursing students: An integrative review. Nurse Education Today 2016, 36, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachi, A.; Kavourgia, E.; Bratis, D.; et al. Anger and Aggression in Relation to Psychological Resilience and Alcohol Abuse among Health Professionals during the First Pandemic Wave. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Cabrera, M.L.; Betancort, M.; Muñoz-Rubilar, C.A.; et al. The Mediating Role of Resilience in the Relationship between Perceived Stress and Mental Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 9762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachi, A.; Tselebis, A.; Sikaras, C.; et al. Nightmare distress, insomnia and resilience of nursing staff in the post-pandemic era. AIMS Public Health 2023, 11, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagini, L.; Moretto, U.; Novi, M.; et al. Lack of resilience is related to stress-related sleep reactivity, hyperarousal, and emotion dysregulation in insomnia disorder. J Clin Sleep Med 2018, 14, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisi, L.; Ciaffi, J.; Bruni, A.; et al. Levels and Factors Associated with Resilience in Italian Healthcare Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Web-Based Survey. Behavioral Sciences 2020, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrague, L.J. Psychological resilience, coping behaviours and social support among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Journal of Nursing Management 2021, 29, 1893–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tziallas, D.; Goutzias, E.; Konstantinidou, E.; et al. Quantitative and qualitative assessment of nurse staffing indicators across NHS public hospitals in Greece. Hell J Nurs 2018, 57, 420–449. [Google Scholar]

- Tselebis, A.; Sikaras, C.; Milionis, C.; et al. A Moderated Mediation Model of the Influence of Cynical Distrust, Medical Mistrust, and Anger on Vaccination Hesitancy in Nursing Staff. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 2023, 13, 2373–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikaras, C.; Tsironi, M.; Zyga, S.; et al. Anxiety, insomnia and family support in nurses, two years after the onset of the pandemic crisis. AIMS Public Health 2023, 10, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikaras, C.; Zyga, S.; Tsironi, M.; et al. The Mediating Role of Depression and of State Anxiety οn the Relationship between Trait Anxiety and Fatigue in Nurses during the Pandemic Crisis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, T.S.; Borritz, M.; Villadsen, E.; et al. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: a new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work Stress 2005, 19, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikaras, C.; Ilias, I.; Tselebis, A.; et al. Nursing staff fatigue and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece. AIMS Public Health 2021, 9, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachi, A.; Sikaras, C.; Ilias, I.; et al. Burnout, Depression and Sense of Coherence in Nurses during the Pandemic Crisis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaefstathiou, E.; Tsounis, A.; Malliarou, M.; et al. Translation and validation of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory amongst Greek doctors. Health Psychology Research 2019, 7, 7678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, L.; Lukasse, M. Burnout among Norwegian midwives and the contribution of personal and work-related factors: A cross-sectional study. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare: Official Journal of the Swedish Association of Midwives 2016, 9, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, I.E.; Lange, T.; Borritz, M.; et al. Burnout as a risk factor for antidepressant treatment - a repeated measures time-to-event analysis of 2936 Danish human service workers. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2015, 65, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovland, I.S.; Skogstad, L.; Diep, L.M.; et al. Burnout among intensive care nurses, physicians and leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national longitudinal study. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 2024. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, S.; Sammour, T.; Neuhaus, S.J.; et al. Burnout in Australasian Younger Fellows. ANZ Journal of Surgery 2009, 79, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, L.P.; Li, C.Y.; Hu, S.C. Job stress and burnout in hospital employees: comparisons of different medical professions in a regional hospital in Taiwan. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, K.Y.; Chan, L.W.; Cheng, P.; Leung, G.K.; Lau, C. Burnout and well-being in young doctors in Hong Kong: a territory-wide cross-sectional survey. Hong Kong Medical Journal = Xianggang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2021, 27, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creedy, D.K.; Sidebotham, M.; Gamble, J.; et al. Prevalence of burnout, depression, anxiety and stress in Australian midwives: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2017, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldatos, C.R.; Dikeos, D.G.; Paparrigopoulos, T.J. The diagnostic validity of the Athens Insomnia Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2003, 55, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldatos, C.R.; Dikeos, D.G.; Paparrigopoulos, T.J. Athens Insomnia Scale: validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2000, 48, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tselebis, A.; Lekka, D.; Sikaras, C.; et al. Sleep Disorders, Perceived Stress and Family Support Among Nursing Staff During the Pandemic Crisis. 2020; 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; et al. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriazos, T.A.; Stalikas, A.; Prassa, K.; et al. Psychometric evidence of the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) and modeling distinctiveness of resilience from depression and stress. Psychology 2018, 9, 1828–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tselebis, A.; Lekka, D.; Sikaras, C.; et al. Insomnia, Perceived Stress, and Family Support among Nursing Staff during the Pandemic Crisis. Healthcare 2020, 8, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Malliarou, M.; et al. Social Support and Resilience Are Protective Factors against COVID-19 Pandemic Burnout and Job Burnout among Nurses in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Healthcare 2024, 12, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulmohdi, N. The relationships between nurses' resilience, burnout, perceived organisational support and social support during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: A quantitative cross-sectional survey. Nursing Open 2024, 11, e2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health at a Glance: Europe 2020 STATE OF HEALTH IN THE EU CYCLE. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/system/files/2020-12/2020_healthatglance_rep_en_0.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/health-at-a-glance-2023_7a7afb35-en.html (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Bratis, D.; Tselebis, A.; Sikaras, C.; et al. Alexithymia and its association with burnout, depression and family support among Greek nursing staff. Human Resources for Health 2009, 7, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachi, A.; Anagnostopoulou, M.; Antoniou, A.; et al. Family support, anger and aggression in health workers during the first wave of the pandemic. AIMS Public Health 2023, 10, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanis, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; et al. Increased Job Burnout and Reduced Job Satisfaction for Nurses Compared to Other Healthcare Workers after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nursing Reports 2023, 13, 1090–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; et al. Impact of workplace bullying on job burnout and turnover intention among nursing staff in Greece: Evidence after the COVID-19 pandemic. AIMS Public Health 2024, 11, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, S.; Vargas, M.; Servillo, G. Organizational strategies to reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 2021, 33, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, S.; Kurt, S.; Bennett, J.A.; et al. Nurses' resilience in the face of coronavirus (COVID-19): An international view. Nursing & Health Sciences 2021, 23, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkow, A.P.; Barger, L.K.; O'Brien, C.S.; et al. Associations between sleep disturbances, mental health outcomes and burnout in firefighters, and the mediating role of sleep during overnight work: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Sleep Research 2019, 28, e12869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Söderström, M.; Jeding, K.; Ekstedt, M.; et al. Insufficient sleep predicts clinical burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 2012, 17, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armon, G.; Shirom, A.; Shapira, I.; et al. On the nature of burnout-insomnia relationships: a prospective study of employed adults. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2008, 65, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, M.D.; Robbins, R.; Quan, S.F.; et al. Association of Sleep Disorders With Physician Burnout. JAMA Network Open 2020, 3, e2023256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assefa, S.Z.; Diaz-Abad, M.; Wickwire, E.M.; Scharf, S.M. The Functions of Sleep. AIMS Neuroscience 2015, 2, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, N.H.; Arora, V.M. The Impact of Sleep and Circadian Disorders on Physician Burnout. Chest 2019, 156, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvagioni, D.A.J.; Melanda, F.N.; Mesas, A.E.; et al. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: a systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0185781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriyama, K. The association between work burnout and insomnia: how to prevent workers' insomnia. Sleep Biol Rhythms 2023, 21, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sørengaard, T.A.; Saksvik-Lehouillier, I. Associations between burnout symptoms and sleep among workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep Med 2022, 90, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zarei, S.; Fooladvand, K. Mediating effect of sleep disturbance and rumination on work-related burnout of nurses treating patients with coronavirus disease. BMC Psychol 2022, 10, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khammissa, R.A.G.; Nemutandani, S.; Feller, G.; et al. Burnout phenomenon: neurophysiological factors, clinical features, and aspects of management. J Int Med Res 2022, 50, 3000605221106428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Metlaine, A.; Sauvet, F.; Gomez-Merino, D.; et al. Association between insomnia symptoms, job strain and burnout syndrome: a cross-sectional survey of 1300 financial workers. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e012816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ye, Z.; Yang, X.; Zeng, C.; et al. Resilience, Social Support, and Coping as Mediators between COVID-19-related Stressful Experiences and Acute Stress Disorder among College Students in China. Applied Psychology. Health and Well-Being 2020, 12, 1074–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Luo, S.; Mu, W.; et al. Effects of sources of social support and resilience on the mental health of different age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMCpsychiatry 2021, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Kolisiati, A.; et al. Resilience and Social Support Improve Mental Health and Quality of Life in Patients with Post-COVID-19 Syndrome. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 2024, 14, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekstedt, M.; Söderström, M.; Akerstedt, T. Sleep physiology in recovery from burnout. Biological psychology 2009, 82, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, H.; Tanaka, H.; Ohkubo, R.; et al. Self-help therapy for sleep problems in hospital nurses in Japan: a controlled pilot study. Sleep and Biological Rhythms 2016, 14, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılınç, T.; Sis Çelik, A. Relationship between the social support and psychological resilience levels perceived by nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A study from Turkey. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 2021, 57, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, K.; Knowlton, M.; Riseden, J. Emergency Department Nursing Burnout and Resilience. Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal 2022, 44, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, K.; Cuzzillo, C.; Furness, T. Strengthening mental health nurses' resilience through a workplace resilience programme: A qualitative inquiry. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 2018, 25, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foureur, M.; Besley, K.; Burton, G.; et al. Enhancing the resilience of nurses and midwives: pilot of a mindfulness-based program for increased health, sense of coherence and decreased depression, anxiety and stress. Contemporary Nurse 2013, 45, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisto, A.; Vicinanza, F.; Campanozzi, L.L.; et al. Towards a Transversal Definition of Psychological Resilience: A Literature Review. Medicina 2019, 55, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barthélemy, E.J.; Thango, N.S.; Höhne, J.; et al. Resilience in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic: How to Bend and not Break. World Neurosurgery 2021, 146, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alameddine, M.; Clinton, M.; Bou-Karroum, K.; et al. Factors Associated With the Resilience of Nurses During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 2021, 18, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Age | Work experience (in years) | Athens Insomnia Scale | Brief Resilience Scale | Copenhagen Burnout Inventory | ||||

| Total | Personal Burnout | Work Related Burnout | Patient Related Burnout | ||||||

| Male | Mean | 47.57 * | 21.89 | 6.35 | 3.58 | 44.91 * | 44.76 ** | 47.83 ** | 41.67 |

| N | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | |

| S.D. | 10.85 | 11.92 | 4.23 | 0.89 | 17.93 | 18.71 | 20.89 | 21.26 | |

| Female | Mean | 44.58 * | 19.92 | 7.31 | 3.40 | 49.64 * | 52.67 ** | 55.45 ** | 39.84 |

| N | 306 | 306 | 306 | 306 | 306 | 306 | 306 | 306 | |

| S.D. | 10.41 | 11.47 | 4.92 | 0.81 | 19.03 | 19.86 | 22.74 | 23.68 | |

| Total | Mean | 45.16 | 20.30 | 7.12 | 3.43 | 48.72 | 51.13 | 53.97 | 40.20 |

| N | 380 | 380 | 380 | 380 | 380 | 380 | 380 | 380 | |

| S.D. | 10.55 | 11.57 | 4.80 | 0.83 | 18.89 | 19.87 | 22.56 | 23.21 | |

| * t test p < 0.05, ** t test p < 0.01 | |||||||||

| Pearson Correlation N: 380 | Age | Work experience (in years) | AIS | BRS | CBI Total | CPB | CWB | |

| Work experience (in years) | r | 0.894 ** | ||||||

| p | 0.001 | |||||||

| Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) | r | -0.064 | -0.126 * | |||||

| p | 0.214 | 0.014 | ||||||

| Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) | r | 0.080 | 0.111 * | -0.423 ** | ||||

| p | 0.120 | 0.030 | 0.001 | |||||

| Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI Total) | r | -0.031 | -0.058 | 0.587 ** | -0.457 ** | |||

| p | 0.552 | 0.257 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||

| Copenhagen Personal Burnout (CPB) | r | -0.024 | -0.068 | 0.634 ** | -0.449 ** | 0.866 ** | ||

| p | 0.642 | 0.183 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| Copenhagen Work-related Burnout (CWB) | r | -0.029 | -0.047 | 0.567 ** | -0.397 ** | 0.919 ** | 0.789 ** | |

| p | 0.578 | 0.362 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Copenhagen Patient-related Burnout | r | -0.026 | -0.039 | 0.327 ** | -0.343 ** | 0.794 ** | 0.482 ** | 0.559 ** |

| p | 0.615 | 0.454 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Dependent Variable: Athens Insomnia Scale | R Square | R Square Change | Beta | t | p | VIF | Durbin-Watson |

| Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI Total) | 0.344 | 0.344 | 0.497 | 10.863 | 0.001 * | 1.264 | 1.918 |

| Brief Resilience Scale | 0.375 | 0.030 | -0.195 | -4.267 | 0.001 * | 1.264 | |

| Notes: Beta = standardized regression coefficient; * Correlations are statistically significant at the p < 0.001 level (only statistically significant variables are included). | |||||||

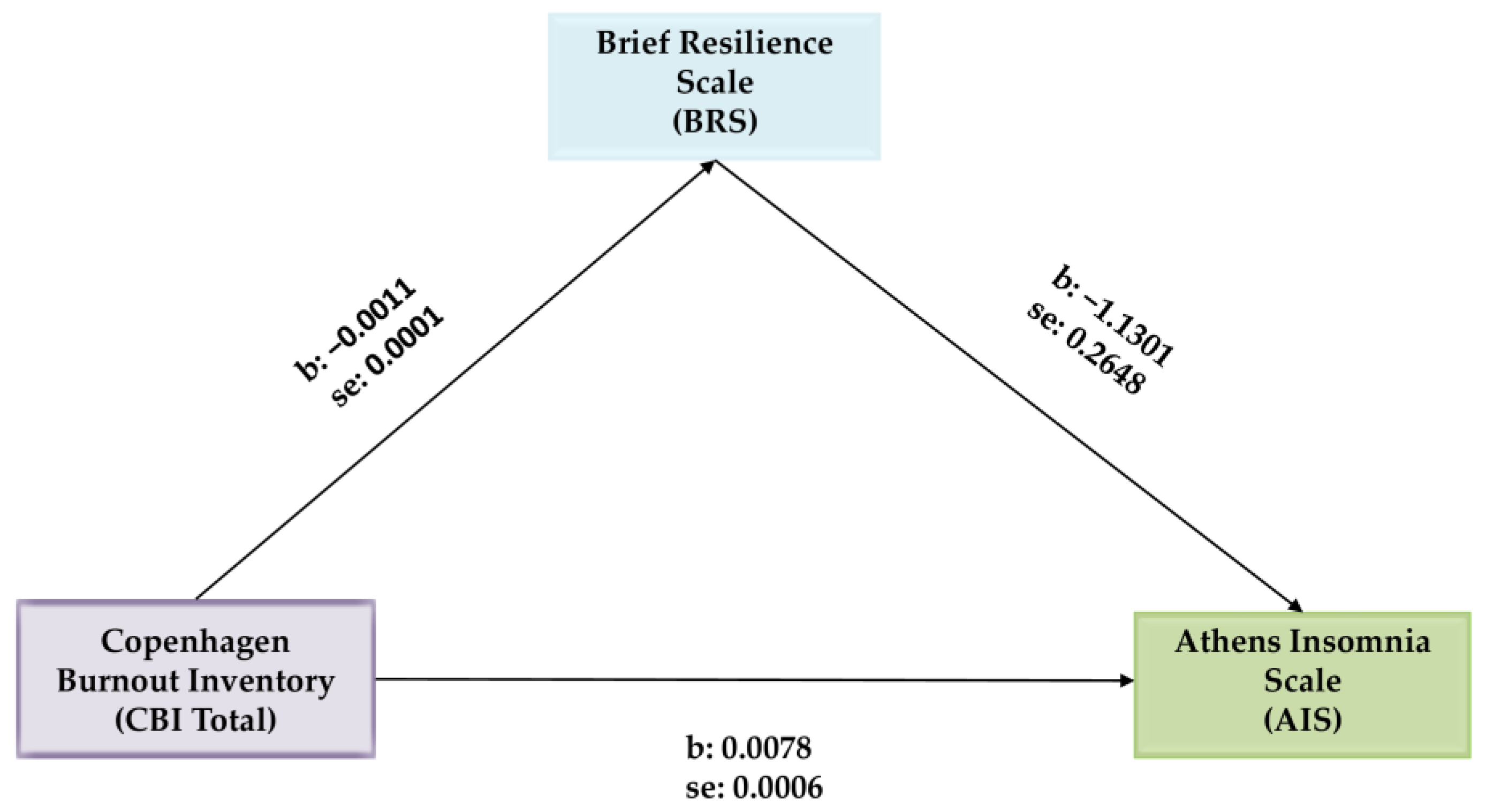

| Variables | b | SE | t | p | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| LLCI | ULCI | |||||

| CBI Total → BRS | −0.0011 | 0.0001 | −9.9928 | 0.001 | −0.0013 | −0.0008 |

| CBI Total → AIS | 0.0078 | 0.0006 | 14.0899 | 0.001 | 0.0068 | 0.0089 |

| CBI Total → BRS → AIS | −1.1301 | 0.2648 | −4.2673 | 0.001 | −1.6509 | −0.6094 |

| Effects | ||||||

| Direct | 0.0066 | 0.0006 | 10.8629 | 0.001 | 0.0054 | 0.0079 |

| Indirect * | 0.0012 | 0.0003 | 0.0006 | 0.0019 | ||

| Total | 0.0078 | 0.0006 | 14.0899 | 0.001 | 0.0068 | 0.089 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).