1. Introduction

The rapid proliferation of web services has revolutionized the way organizations deliver functionality and data to users. From e-commerce platforms to online banking systems, web services form the backbone of modern digital infrastructure. However, the growing reliance on web applications has also led to an increase in their exploitation as attack vectors, exposing them to various cybersecurity threats.

Among the most prevalent and damaging forms of web attacks are SQL Injection (SQLi) attacks [

1,

2], which target the database layer of web applications. By exploiting vulnerabilities in query handling, attackers can manipulate backend databases, retrieve sensitive information, or even disrupt services. The significance of SQLi attacks cannot be overstated; they remain a top concern for organizations due to their frequency and the severe impact they can have on data confidentiality, integrity, and availability [

3]

To defend against SQLi attacks, Web Application Firewalls (WAFs) are widely deployed as a first line of defense [

4]. WAFs detect and block malicious payloads by analyzing incoming HTTP traffic for known attack patterns. However, traditional WAFs often struggle to keep pace with the constantly evolving landscape of attack techniques. Sophisticated attackers can craft novel SQLi payloads that bypass even state-of-the-art WAF rules, highlighting the need for adaptive and proactive defense mechanisms.

Generative AI offers a promising avenue for addressing this challenge [

5]. Generative AI Large Language Models (LLMs), such as GPT-4o from OpenAI [

6], Gemini from Google [

7], Llama 3.2 from Meta [

8] and Claude Sonnet 3.5 from Anthropic [

9], represent the cutting edge of artificial intelligence, capable of producing human-like text, generating code, and even simulating complex attack vectors. By leveraging large-scale neural networks and in-context learning, generative AI systems can synthesize novel outputs based on carefully curated input examples, making them highly adaptable across a range of domains.

The use cases for generative AI are diverse, spanning creative content generation, natural language processing, and advanced problem-solving tasks. In the realm of cybersecurity, generative AI has shown potential for both offensive and defensive applications [

10]. It can simulate attack scenarios to stress-test defenses, assist in vulnerability detection, and automate the creation of countermeasures. These capabilities position generative AI as a transformative tool for addressing emerging security threats.

In this paper, we propose a novel generative AI framework for evolving and securing against SQL Injection Attacks. Our framework leverages the power of generative AI to achieve two primary objectives:

Generation of Novel SQL Injection Attacks: Using in-context learning, our approach uses LLMs to generate diverse SQLi payloads based on curated examples. These attacks are validated against actual database implementations to ensure authenticity and guard against hallucinated payloads.

Automated Defense Mechanisms: By testing the generated attacks against a vulnerable web application secured by a Web Application Firewall (WAF), we identify payloads that successfully bypass state-of-the-art WAF rules. These bypassing attacks are classified using machine learning algorithms, and new WAF rules are automatically generated using LLMs. The updated rules are then incorporated into the WAF, and the attack scenarios are re-executed to validate their effectiveness.

Through this iterative process, the framework demonstrates a unique capability to improve WAF security dynamically. By using generative AI for both attack generation and defense optimization, the framework provides a holistic approach to addressing SQL injection vulnerabilities.

Our experimental results demonstrate the efficacy of this approach. Using GPT-4o LLM, we successfully generated 514 new SQLi payloads, 92.5% of which were validated against a MySQL database. Of these attacks, 89% bypassed state-of-the-art WAFs such as ModSecurity [

11] equipped with the latest version of the OWASP CoreRuleSet [

12]. By applying our machine learning classification and GPT-4o LLM rule-generation methodology, we were able to develop and validate security rules that effectively blocked 99% of all previously successful attacks with only 23 new rules. To facilitate the replication of our work, we have provided detailed appendices that include the prompts used. We also present results with the Google Gemini-Pro LLM. We plan to open-source the GenSQLi framework so that the capabilities of Generative AI can be harnessed by cybersecurity practitioners to safeguard against evolving SQLi attacks.

The paper makes the following contributions -

Novel Framework for SQLi Mitigation: Development of a generative AI-based framework that generates novel SQL injection attacks and automatically evolves WAF defenses.

In-Context Learning for Attack Generation: Utilization of generative AI models with curated examples to produce diverse and validated SQLi payloads, minimizing hallucinations.

Automated WAF Rule Optimization: Integration of machine learning and generative AI techniques to classify bypassing attacks and generate effective WAF rules.

Demonstrated Efficacy: Experimental validation showing improved WAF security by blocking 99% of previously bypassing SQLi attacks with only a limited number of new rules.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the existing literature on the application of generative AI in cybersecurity.

Section 3 provides a concise background on SQL injection (SQLi) attacks and generative AI.

Section 4 outlines the proposed framework in detail.

Section 5 presents the evaluation results.

Section 6 discusses the broader implications of the proposed approach. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the paper by summarizing the findings and suggesting directions for future research.

2. Related Work

Web Application Firewalls (WAFs) are one of the most widely used defense systems against SQL injection (SQLi) attacks (See

Section 3 for a brief background on WAFs). WAFs utilize two common strategies to defend against SQLi attacks -

Rule-based approach detects attacks based on known attack signatures. Rules are typically written as a sequence of regular expressions designed to detect many forms of attacks. Rule based methods enjoy the advantages of being deterministic and transparent, having low false positive rates, are quickly deployable, being compliance friendly, and are resource efficient. However, they are limited to known patterns, require regular updates, are unable to adapt to slight variations in attack patterns, and have scalability issues.

Machine learning-based approach detects attacks by learning from data to identify anomalous or malicious patterns in SQL queries. These methods typically involve training models on historical data, including both benign and malicious queries, to classify or detect suspicious behavior. Machine learning-based methods enjoy the advantages of being adaptable to novel or obfuscated attack patterns, detecting deviations from normal behavior rather than relying on static signatures, improving continuously with more data, and reducing the need for explicit rule maintenance. However, they have drawbacks such as high false positive rates in poorly trained models, being resource-intensive, having complex and non-transparent decision-making processes, depending heavily on the availability and quality of labeled data, and requiring significant time and effort for initial deployment and fine-tuning.

El Ghawazi et. al. [

13] and Applebaum et. al. [

14] present a review of literature that employs machine learning and deep learning techniques to detect SQLi attacks.

Since our work focuses on enhancing WAF robustness through a Generative AI-driven framework capable of generating novel SQLi attacks and updating existing WAF rules, we review related work in the areas of SQLi attack generation, rule adaptation, and WAF robustness improvement.

Qu et. al. [

15] proposes a technique that transforms an original SQLi payload into generated SQLi payloads that can bypass WAF, through the use of context free grammar (CFG) for generation, and a Monte Carlo tree search for selection.

Zhang et. al. [

16] addresses the challenge of unevenly distributed effective attack payloads by leveraging context-free grammar (CFG) to describe attack patterns and decomposing payloads into tokens. Feature vectors are extracted using label cleaning, and cosine distance metrics are employed to measure similarity between payloads. By adaptively selecting and executing promising payloads based on these metrics, they reduce unsuccessful attack trials

Demetrio et. al. [

17] use a series of mutation operators — such as case swapping, whitespace substitution, and comment injection, to iteratively generate new payloads starting with a malicious payload that is detected by WAF. These mutation operators preserve the semantic integrity of the payloads, ensuring they remain functionally identical from the adversary’s perspective. However, these transformations gradually reduce the confidence of the WAF’s classification algorithm. This process continues until the payload’s classification falls below the rejection threshold, resulting in successful SQLi attacks.

Appelt et al. [

18] propose an automated approach to generate SQL injection attacks capable of bypassing WAFs. They utilize a genetic algorithm to evolve effective attack patterns. By training a decision tree model on a dataset of labeled attacks, the system identifies successful patterns and generates new attacks based on them. This iterative process allows for the discovery of increasingly sophisticated attacks that can evade WAF defenses.

Hemmati et al. [

19] utilize Deep Reinforcement Learning algorithms, specifically DQN and PPO, to iteratively apply a set of modification operators to an initial malicious SQLi attack. The goal is to generate new SQLi attacks that successfully evade the WAF while preserving the malicious intent of the original payload.

In contrast to the aforementioned works, our approach leverages Generative AI trained on SQLi attack data to generate novel SQLi attacks capable of bypassing WAFs. Additionally, we close the loop by using Generative AI to generate WAF security rules that can effectively detect these attacks. A key advantage of Generative AI over techniques such as context-free grammars is the reduced technical expertise required to enhance WAF robustness. Furthermore, methods like context-free grammars, genetic algorithms, and reinforcement learning could be employed to generate in-context data for training Generative AI models. Exploring this integration is left for future work.

3. Background

In this Section, we provide a brief background on SQL injection attacks, Web Application Firewalls, and Generative AI.

3.1. SQL Injection Attacks

SQL injection (SQLi) attacks are a type of security vulnerability that occurs when an attacker manipulates SQL queries executed by a web application [

2]. These attacks exploit improper handling of user inputs in SQL statements, allowing attackers to access, modify, or delete sensitive database information. Common attack vectors include login forms, search fields, and URL parameters.

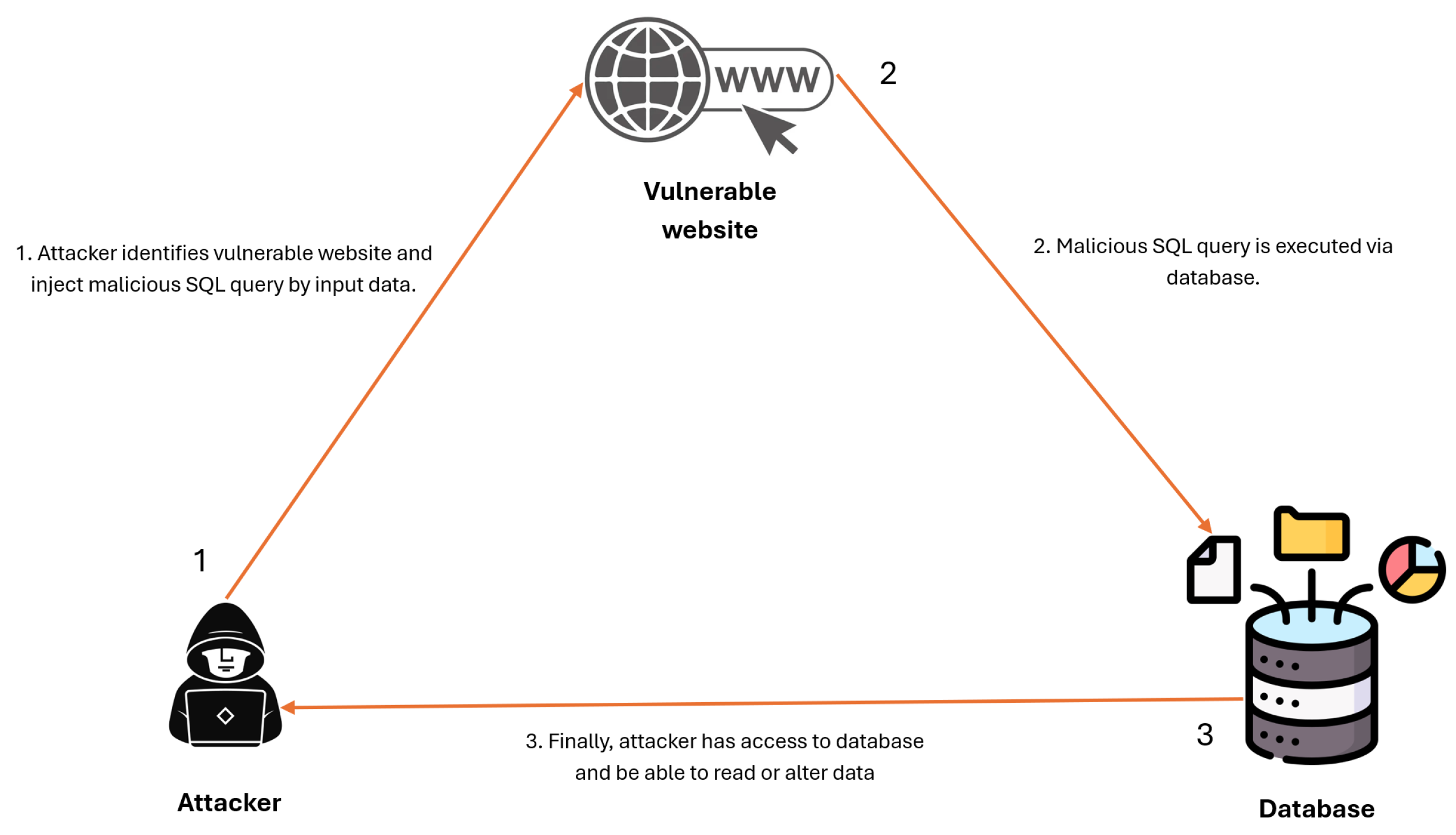

Figure 1 illustrates the operational mechanism of an SQL injection attack.

As a simple illustrative example, consider a web application with a login form where users enter their username and password. The backend code might construct an SQL query like this:

If the application does not properly sanitize user inputs, an attacker could input the following in the username field:

This modifies the query to:

The – marks the rest of the query as a comment, so everything after it is ignored.

Since ’1’=’1’ is always true, the query retrieves all rows from the users table.

SQLi attacks today are far more complex. SQLi attacks can be broadly categorized based on the techniques used [

2]. In this paper we focus on the following types of SQLi attacks:

Conditional attacksuse payloads that manipulate query conditions to infer database information by observing changes in the application’s behavior.

Error-based attacks exploit error messages returned by the database to extract details about its structure or configuration.

Tautology attacks involve injecting always-true conditions (e.g., 1=1) into queries to bypass authentication or retrieve unintended data.

Tautology and conditional attacks combine these techniques, using tautologies to identify vulnerable points and conditions to refine the extraction of specific information.

Exist-based attacks rely on verifying the existence of certain data or tables in the database through crafted payloads, often by leveraging subtle response differences.

In addition to the above attacks, other attack types include - Union-based attacks uses the UNION operator to merge legitimate query results with attacker-crafted data, allowing data retrieval from other tables. Inferential attacks (Blind SQLi) relies on deducing database information indirectly through application responses or execution delays, without receiving direct query results. Time-based attacks, a subset of Blind SQLi, injects queries that trigger delays to infer true/false conditions. Out-of-band attacks exploits alternative communication channels, such as DNS or HTTP, for data exfiltration, often useful when traditional channels are unavailable. Stored attacksinvolves inserting malicious payloads into a database, which executes later when accessed, making it particularly dangerous in shared or dynamic environments. Second-order attacksembeds payloads that are stored and later executed in a different context within the application, often bypassing traditional input sanitization.

3.1.1. Obfuscation in SQL Injection Attacks

Obfuscation refers to techniques used by attackers to disguise or modify malicious SQLi payloads in order to evade detection by security mechanisms such as Web Application Firewalls (WAFs), intrusion detection systems (IDS), or input validation filters [

20]. By altering the appearance of SQLi payloads without changing their functionality, attackers aim to bypass pattern-based defenses or heuristic checks.

Some common obfuscation techniques include - Encoding and escaping involve using character encoding schemes like URL encoding, hexadecimal, or Unicode to mask malicious inputs. Case alteration changes the capitalization of SQL keywords to bypass case-sensitive filters. Comment injection adds inline or end-of-line comments to split payloads and confuse signature-based detection. White space manipulation replaces spaces with tabs, newlines, or comment breaks to modify query structure. String concatenation breaks strings into smaller parts and recombines them during query execution. Keyword substitution replaces standard SQL keywords with database-specific alternatives or synonyms. Hexadecimal or binary representations encode strings or commands in hexadecimal or binary formats. Using false logic or complex queries introduces redundant logic or unnecessary operations to make the query appear legitimate. Exploiting database-specific functions leverages database-specific syntax, features, or quirks to evade detection.Dynamic query construction employs nested queries or dynamic expressions to obscure the true intent of the malicious payload.

A comprehensive review of SQL injection attacks can be found in [

21].

3.2. Web Application Firewalls (WAFs)

A Web Application Firewall (WAF) is a security mechanism designed to protect web applications by monitoring, filtering, and blocking malicious HTTP/S traffic. Unlike traditional firewalls that safeguard networks, WAFs focus on protecting the application layer (Layer 7 of the OSI model) [

22]. They are commonly used to defend against web-based attacks such as SQL injection (SQLi), cross-site scripting (XSS), and distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks. WAFs match incoming traffic against a database of known attack patterns. Some notable WAFs include AWS WAF, Microsoft Azure WAF, CloudFlare WAF, Imperva, Fortinet and ModSecurity.

In this research, we use Modsecurity [

11], since it is an open-source WAF and used in conjunction with Apache and Nginx servers. It uses rules to identify and mitigate malicious HTTP/S requests. These rules form the backbone of ModSecurity’s ability to protect web applications by defining patterns, behaviors, and conditions that determine what traffic should be allowed, denied, or flagged for review. Each ModSecurity rule is written in its SecRule directive and typically includes:

Input to Monitor - specifies which part of the request or response to inspect (e.g., headers, parameters, or body).

Operator - defines the condition to match (e.g., checking for specific patterns or keywords).

Action - Specifies what to do if the rule is triggered (e.g., deny, log, or redirect).

The OWASP CRS [

12] is a set of generic attack detection rules for use with ModSecurity.

It should be noted that the proposed GenSQLi framework is generic, and can be used to enhance the robustness of any WAF against SQLi attacks.

3.3. Generative AI

Generative AI refers to a branch of artificial intelligence that creates new data or content, such as text, images, audio, or code, by learning patterns from existing datasets. Central to this field are large language models (LLMs), which are deep learning architectures trained on massive amounts of text data to generate coherent and contextually appropriate language [

23,

24]. These models, such as GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), leverage advancements in machine learning and deep learning, particularly transformer architectures, to capture complex relationships within data. Deep learning enables these models to process and understand vast datasets through multi-layered neural networks, where each layer extracts increasingly abstract features. The complexity of LLMs arises from their scale, with billions (or even trillions) of parameters, requiring significant computational resources for training.

Applications of generative AI are diverse, including natural language processing tasks like chatbots, translation, and summarization, as well as creative fields such as content generation, code completion, and synthetic data creation for research. As of the time of writing of this paper, GPT-4o from OpenAI [

6], Gemini-Pro from Google [

7], Llama 3.2 from Meta [

8], and Claude Sonnet 3.5 from Anthropic [

9], represent the cutting edge of LLMs. For a modest price, these LLMs can be accessed programmatically via REST APIs without requiring direct deployment or infrastructure management. Additionally, Llama models from Meta are open source, and can be hosted locally.

Customizing Large Language Models (LLMs) involves adapting pre-trained models to specific tasks, domains, or user requirements. Below are common techniques used for this purpose [

25]:

Fine-Tuning: The model is retrained on a smaller, task-specific dataset while retaining knowledge from its pre-training phase.

Prompt Engineering: Carefully crafting input prompts to guide the model’s behavior without altering its parameters.

In-Context Learning: Providing examples of the desired task within the input prompt so the model can infer patterns and mimic behavior.

Reinforcement Learning With Human Feedback (RLHF): Uses reinforcement learning to align the model’s outputs with human preferences

Additionally, LLMs can be augmented with additional data source (Retrieval Augmented Generation) [

26], call external APIs or invoke specific tools, and augmented with persistent memory to store and recall context beyond a single prompt-response cycle [

27]. Further with agentic LLMs, multiple LLM based agents can act collaboratively to reason, plan, and execute actions in a dynamic or goal-oriented manner [

28].

4. GenSQLi Framework

In this Section we present the details of GenSQLi, a general and extendable framework for robustifying WAFs against SQLi attack. To the best of our knowledge, GenSQLi represents the first reported application of Generative AI to both generate and defend against SQLi attacks. The proposed framework is independent of any particular LLM, database, application, and WAF.

4.1. Architecture

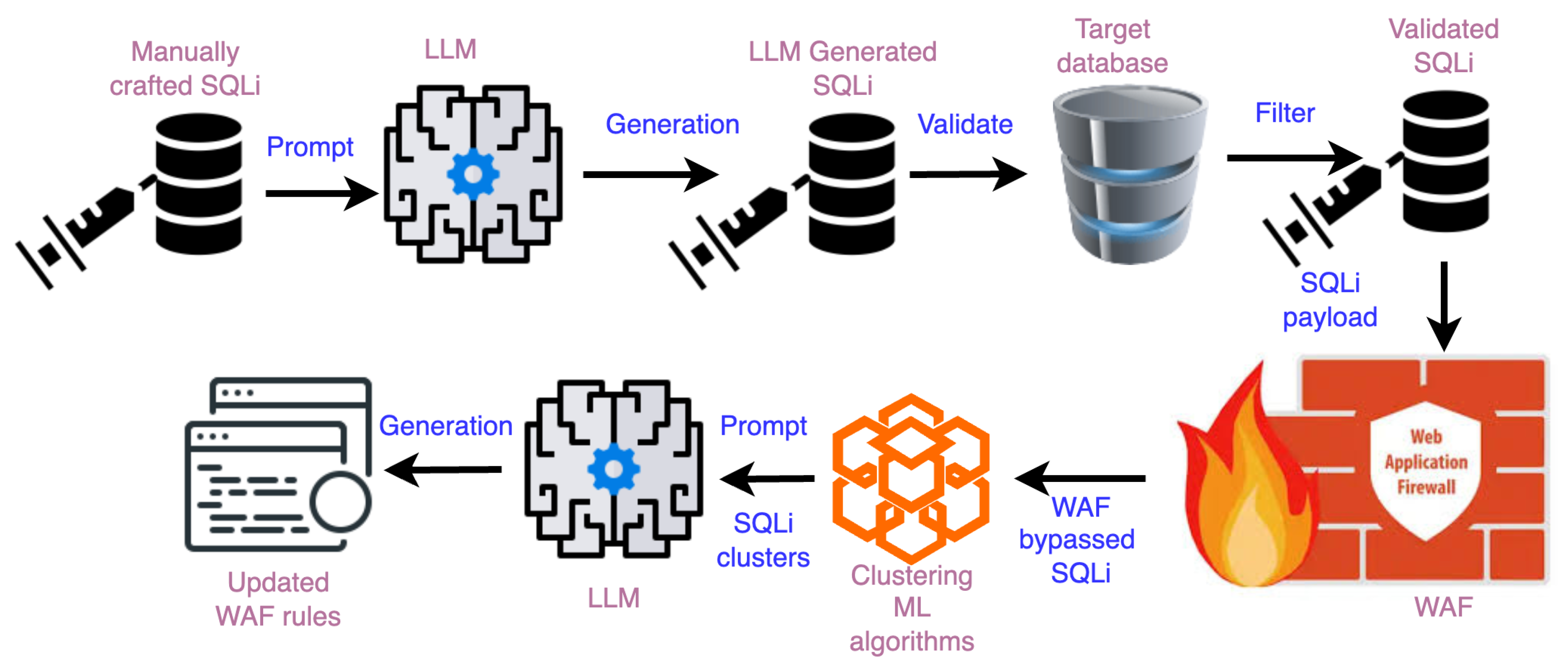

Figure 2 illustrates the architecture of GenSQLi. The process begins with generative large language models (LLMs) being prompted using carefully curated in-context examples of SQL injection (SQLi) attacks to generate potential SQLi payloads. Since LLMs may produce inaccurate or irrelevant outputs (referred to as "hallucinations"), generated SQLi samples are validated against a target database to confirm their effectiveness as legitimate SQLi attacks.

Validated SQLi samples are then evaluated within a test setup comprising a vulnerable application and a Web Application Firewall (WAF). SQLi attacks that successfully bypass the WAF are recorded and analyzed using machine learning clustering algorithms to group similar attack types. LLMs are subsequently tasked with generating WAF rules tailored to mitigate these identified attack patterns.

To optimize the effectiveness of the WAF rules, a reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF) methodology is applied. This iterative refinement process continues until all SQLi attacks are successfully mitigated. The entire workflow is repeatable to iteratively develop a robust set of security rules.

In the remainder of this Section, we describe each of these steps in detail.

4.2. SQLi Generation

The in-context learning examples used to prompt the large language models (LLMs) were manually crafted and validated against a vulnerable application connected to a MySQL database. These examples served as a foundation for the LLMs to generate obfuscated SQL injection (SQLi) samples. The prompts provided clear instructions, guiding the LLMs to systematically apply various obfuscation techniques to create complex and diverse SQLi payloads while ensuring compatibility with the target database syntax.

Key elements of the prompt included a task description emphasizing the generation of obfuscated SQLi attacks by applying relevant bypass methods. The LLMs were instructed to maintain the logical integrity and functionality of the original SQLi attack. The database context — such as database name, table name, and column names — as specified to enable accurate replacement of placeholders within the generated queries. Output requirements were defined to produce a specific number of samples with consistent formatting and without extraneous explanations. Constraints were also outlined to prevent the use of incompatible techniques and to ensure adherence to the target database syntax. The overall objective was to generate a comprehensive set of obfuscated SQLi attacks for testing and improving the effectiveness of Web Application Firewalls (WAFs).

4.3. SQLi Validation

The validation process involved a predefined test database containing a users table with three columns: id, username, and password. The SQLi attacks used as in-context learning examples were first tested in a vulnerable application configured with the target database to ensure their effectiveness. These examples were then evaluated against the target WAF to assess their ability to bypass defenses. Similarly, the SQLi attacks generated by LLMs were validated within the same vulnerable application setup to confirm their functionality. This step ensured that all generated SQLi queries adhered to target database syntax and successfully executed as intended within the database context. The validated SQLi attacks were subsequently used in further evaluations of WAF effectiveness and rule refinement.

4.4. SQLi Clustering

To cluster and analyze SQL injection (SQLi) attacks, three different machine learning algorithms were employed: TF-IDF with Agglomerative Clustering, SequenceMatcher with DBSCAN, and Regex-Inspired Clustering. Each method offers distinct advantages and is suited to different aspects of the clustering task.

4.4.1. TF-IDF with Agglomerative Clustering

Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) is a statistical measure used to evaluate the importance of words in a document relative to a collection of documents (or queries, in our case) [

29]. It combines two concepts: Term Frequency (TF): Measures how frequently a word appears in a query. Inverse Document Frequency (IDF): Diminishes the weight of words that are common across all queries, such as logical operators like AND or OR. By focusing on unique or less common words, TF-IDF highlights the distinctive terms within each SQLi query.

Agglomerative Clustering is a hierarchical clustering method that treats each query as an individual cluster initially [

30]. It then iteratively merges the clusters based on their similarity until a stopping criterion is met.

Each SQLi query is converted into a TF-IDF vector, capturing the importance of its terms. The clustering algorithm computes the similarity between these vectors to group similar queries. For example: Query 1: SELECT 1=1 focuses on the terms SELECT and 1=1. Query 2: SELECT 1=1 OR 0x61=0x61 shares similar terms and would be grouped with Query 1.

4.4.2. Sequence Matcher with DBSCAN

SequenceMatcher is an algorithm that computes the similarity between two strings by comparing their sequences of characters. It is adept at identifying structural similarities even when the exact words differ. DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise) is a clustering algorithm that groups together points (queries) that are closely packed together, marking points that lie alone in low-density regions as outliers or noise [

31].

Each pair of SQLi queries is compared using SequenceMatcher to calculate a similarity score based on their character sequences. For example: Query 1: SELECT 1=1 Query 2: SELECT 0x61=0x61 SequenceMatcher identifies structural similarity due to the common use of a SELECT statement with a condition. These similarity scores are used by DBSCAN to cluster queries based on the density of similar queries, effectively grouping structurally similar attacks.

4.4.3. Regex-Inspired Clustering

Regular Expressions (Regex) are patterns that describe sets of strings and are used for string matching. In the context of SQLi clustering, regex patterns are designed to match specific SQLi techniques [

32]. Defined regex patterns correspond to common SQLi obfuscation techniques: Each SQLi query is checked against these patterns to identify the techniques used. Queries are clustered based on the matched pattern. For example, Query 1: SELECT 0x61=0x61 is assigned to the “Hexadecimal Encoding” cluster. Query2 : CONCAT(’a’, ”) = ’a’ falls under the “String Manipulation” cluster.

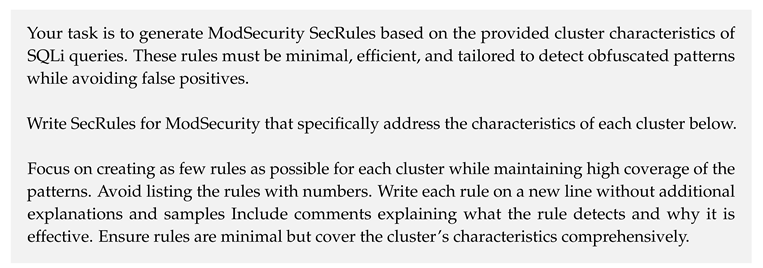

4.5. WAF Security Rule Generation

To generate Web Application Firewall (WAF) security rules based on clusters of SQL injection (SQLi) attacks, the process involved crafting specialized prompts for LLMs. The prompts assigned the LLM the role of a security expert tasked with creating efficient WAF rules to protect against SQLi attacks. For each identified cluster—characterized by specific obfuscation techniques such as character manipulation, encoding methods, and logical tautologies—the prompt included detailed characteristics and one or two example queries exemplifying the cluster’s traits.

The LLM was instructed to generate minimal and efficient targeted WAF rules that effectively detect the obfuscated patterns specific to each cluster. Emphasis was placed on combining rules where feasible to enhance efficiency and reduce false positives. The output requirements specified that the rules must follow proper targeted WAF rule syntax, include comments explaining each rule’s purpose and effectiveness, and ensure comprehensive coverage of all identified characteristics. Constraints were set to focus on efficiency and compatibility, ensuring the generated rules are valid and effective in mitigating the obfuscated SQLi patterns across all clusters.

5. Evaluation and Results

This section presents an experimental evaluation of GenSQLi and reports its performance metrics. The evaluation addresses the following key research questions:

RQ1: Generative Effectiveness – How effective are the SQL injection (SQLi) attacks generated by the large language model (LLM)?

RQ2: Attack Novelty – How many of these generated attacks successfully bypass web application firewalls (WAFs) configured with state-of-the-art rules?

RQ3: Rule Generation – How effective are the defense rules produced by our combined machine learning and generative AI approach in mitigating these attacks?

RQ4: LLM Portability – How well does the methodology generalize when applied to different LLMs?

5.1. Experimental Setup

The GenSQLi architecture of

Figure 2 was implemented with the following open-source projects shown in

Table 1

A custom PHP application was developed to interact with a MySQL database by executing SQL queries based on user input received via HTTP requests. The application lacks proper input sanitization, making it vulnerable to SQL injection attacks. This design enables testing the effectiveness of the web application firewall (WAF) independently of any application-level query sanitization mechanisms.

5.2. Sample SQLi Generation

To demonstrate the operation of GenSQLi, we present a specific example of a generated SQL injection (SQLi) attack that successfully bypasses ModSecurity.

5.2.2. Analysis of the Generated Query

The payload is designed to exploit a numeric-based SQL injection vulnerability with the following key components:

-7552: A numeric value that integrates seamlessly into the backend SQL query syntax.

OR: A logical operator that overrides the original query condition if the injected condition evaluates to TRUE.

-

SELECT CASE WHEN ... THEN 1 ELSE 0 END: A subquery introducing conditional logic that evaluates specific conditions:

- –

6872=6872: A tautology ensuring this condition always evaluates to TRUE.

- –

ASCII(’a’)=97 COLLATE utf8mb4_bin: Confirms the ASCII value of ’a’ matches 97, which is also TRUE.

=1: Forces the overall query condition to evaluate as TRUE when the subquery result equals 1.

5.2.3. Payload Submission to the Vulnerable Application

The payload is typically injected through parameters such as URLs or form fields. For example, using a URL-based attack:

The application appends the user-supplied input (-7552 OR (SELECT CASE WHEN ...)) directly into its backend query due to inadequate input sanitization or the absence of parameterized queries.

5.2.4. Final Backend SQL Query

The vulnerable application generates the following backend query:

The query operates as follows:

id = -7552: Checks for a user with an id of -7552. Typically, this returns no results unless such an ID exists.

-

OR (SELECT CASE WHEN ...) = 1:

- –

The OR operator ensures that if the first condition fails, the injected condition is evaluated.

- –

-

The CASE WHEN statement evaluates the following conditions:

- *

6872=6872: A tautology, always TRUE.

- *

ASCII(’a’)=97 COLLATE utf8mb4_bin: Verifies that the ASCII value of ’a’ matches 97, also TRUE.

- –

Since both conditions are TRUE, the CASE WHEN statement returns 1, making the overall expression evaluate to TRUE.

5.2.5. Execution and Outcome

As the injected condition evaluates to TRUE, the query bypasses the original id = -7552 condition and retrieves all rows from the users table.

5.2.6. Bypassing ModSecurity

The payload bypasses ModSecurity by leveraging the following techniques:

Numeric Input: Begins with a numeric value (-7552), evading common WAF rules targeting string-based SQL injections.

Conditional Logic and Obfuscation: Uses CASE WHEN, arithmetic (6872=6872), and character functions (ASCII(’a’)=97) to introduce complexity and obscure intent.

Valid SQL Syntax: Maintains proper syntax, allowing it to integrate seamlessly into the backend query without causing errors.

This example highlights the effectiveness of GenSQLi in generating novel and obfuscated SQLi attacks capable of bypassing modern WAFs.

5.3. Results

Table 2 summarizes the results of SQL injection (SQLi) generation using the GPT-4o and Gemini LLM models. Both models were provided a prompt (detailed in

Appendix A) along with 11 manually crafted obfuscated SQLi samples as in-context examples. The generated samples were validated for correctness using a MySQL database.

GPT-4o: Generated 514 samples, of which 475 were valid SQLi payloads, achieving a validity rate of 92.5%.

Gemini: Generated 393 samples, of which 209 were valid, resulting in a validity rate of 53.1%.

These results indicate that GPT-4o is more consistent in generating valid SQLi attacks. Notably, Gemini Pro exhibits a higher tendency to generate hallucinated outputs compared to GPT-4o.

Table 3 and

Table 4 provides a breakdown of the validated SQLi samples genreated by GPT-4o and Gemini-Pro respectively. The SQLi attacks are listed by type of attack.

GPT-4o: Of the 475 validated SQLi attacks, 422 (89%) bypassed ModSecurity.

Gemini Pro: Of the 209 validated SQLi attacks, 118 (56.5%) bypassed ModSecurity.

Both models predominantly generated conditional and tautology-based SQLi attacks, accounting for over 60% of the total attacks. Overall, 89% of the SQLi attacks generated by GPT-4o, and 56.5% for Gemini-Pro were able to bypass Modsecurity. These findings demonstrate the ability of GPT-4o to produce novel and effective SQLi payloads through proper prompting and in-context learning.

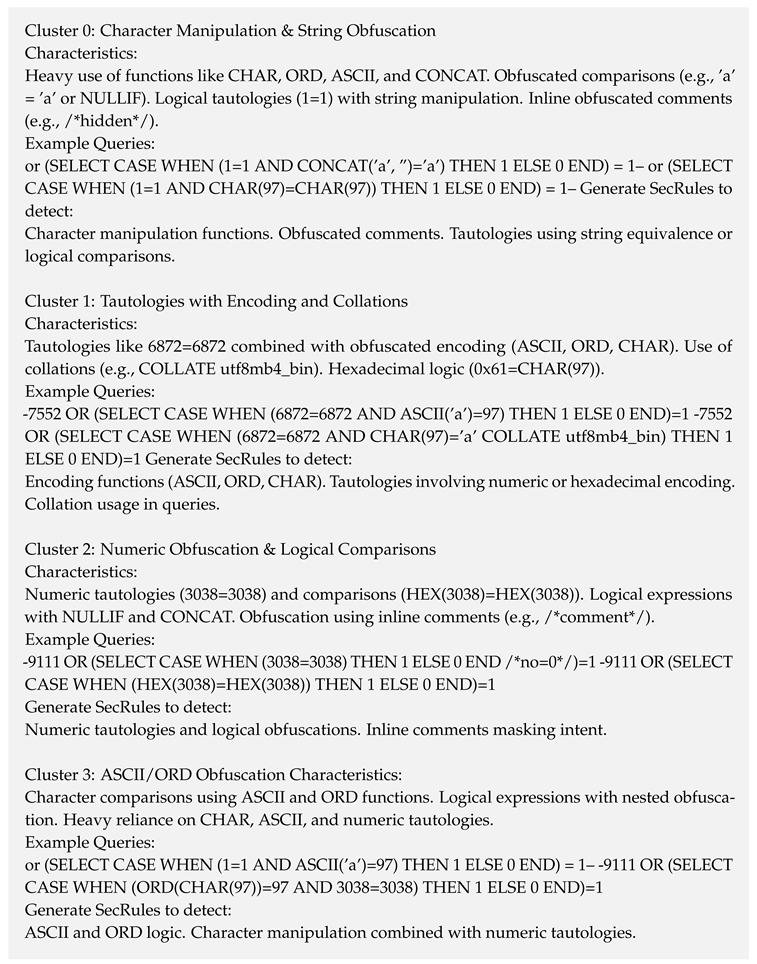

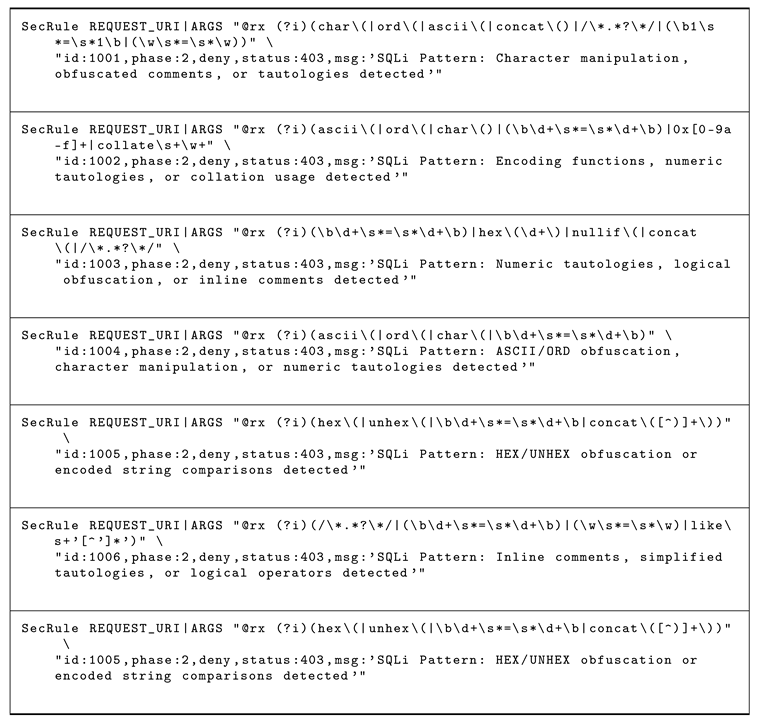

Table 5 presents the evaluation results for ModSecurity rules generated using the three clustering techniques described in

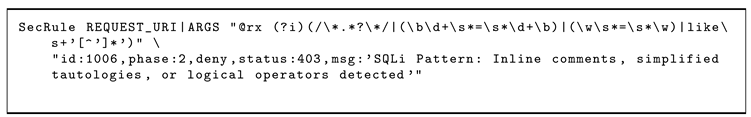

Section 4. We note that TF-IDF and SeqMatcher+DBSCAN clustering driven rule generation by GPT-4o shows the best performance. A total of 23 SecRules, generated using the SeqMatcher algorithm combined with the DBSCAN classifier, successfully blocked 99% of the 475 SQLi attacks that had previously bypassed ModSecurity. Samples of these rules are provided in

Appendix B.

We provide a brief intuition on the performance of the clustering strategies based on the results of

Table 5. DBSCAN excels at grouping SQLi queries with similar structures, even when obfuscated, by dynamically adapting to the dataset and identifying natural clusters without needing predefined cluster counts. It focuses on meaningful patterns while excluding outliers, though it may cluster noisy data if their structure appears similar. In contrast, TF-IDF identifies important terms across the dataset, emphasizing unique features of SQLi attacks and reducing noise by de-emphasizing irrelevant terms. This approach enables precise clustering and rule generation, making it effective for targeting specific attack types with high precision and minimal false positives. While regex rules rely on manual creation and the intuition of the rule writer, they are limited by their inability to anticipate the diverse and creative obfuscation techniques used in SQLi attacks. Overall, TF-IDF provides a global perspective on query patterns, while DBSCAN offers localized similarity clustering. Our results suggest that both strategies could be used to identify the most effective SecRules that can be generated.

6. Discussion

The increasing capabilities of Generative AI are significantly influencing the field of cybersecurity. Threat actors are leveraging Generative AI to scale the scope and sophistication of their attacks. In this paper we introduced GenSQLi, a Generative AI-based framework designed to help cybersecurity defenders strengthen their systems against SQL injection (SQLi) attacks. GenSQLi employs Generative AI to synthesize novel SQLi attack patterns capable of bypassing existing Web Application Firewall (WAF) security rules. The framework then combines machine learning with Generative AI to generate defense rules that address entire classes of these attacks.

This approach exemplifies the potential of using Generative AI to proactively enhance cybersecurity defenses by synthesizing potential attack scenarios before they are encountered in real-world systems. The process can be iterated with multiple generation strategies until a satisfactory level of robustness is achieved. Existing SQLi generation techniques, such as context-free grammars and evolutionary algorithms (see

Section 2), can serve as in-context learning examples to create families of similar attacks. Additionally, newly discovered attacks can immediately be incorporated as in-context examples to generate similar attack vectors and corresponding defense rules.

An advantage of using Generative AI in this capacity is the relative ease of generating both attacks and defenses, particularly when compared to traditional methods like context-free grammars. This lowers the technical barrier, enabling a broader range of cybersecurity practitioners to enhance system defenses against cyberattacks.

6.1. Observations on Generative AI Model Restrictions

Our research highlights an important observation: some publicly available models, such as Anthropic Claude and Meta’s LLaMA, refused to generate SQLi attack vectors. While such restrictions aim to limit misuse by attackers, they also inhibit defenders from leveraging these models for creating proactive defenses. This creates a double-edged sword; while the restrictions may curb certain malicious activities, they can also disadvantage smaller defenders who lack the resources to develop proprietary Generative AI models.

We argue that determined adversaries, such as nation-states and large criminal organizations, are likely to possess the resources to build their own Generative AI systems for crafting sophisticated attacks. Consequently, enabling smaller defenders to access similar capabilities becomes crucial. However, we recognize this as a significant public policy question requiring further investigation.

Our work aims to catalyze discussions on the role of publicly available Generative AI models in cybersecurity. The balance between restricting Generative AI for ethical concerns and empowering defenders to address emerging threats is a nuanced issue deserving deeper exploration.

6.2. Limitations

While the generated SQLi samples offer significant insights, this research has certain limitations. Although GPT-4o successfully generated a diverse range of SQLi samples, its output is limited by token constraints, impacting both the quantity and complexity of the samples produced. Additionally, the validation was conducted in a controlled environment with ModSecurity as the sole defense layer. This approach may not fully capture the challenges faced in more complex, real-world scenarios where multiple security mechanisms (for example, input sanitization) are involved.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we presented a novel generative AI framework designed to enhance the security posture against SQLi attacks by leveraging the advanced capabilities of large language models (LLMs). Our framework achieves two pivotal objectives:

Generation of Novel SQLi Attacks: Utilizing in-context learning with carefully curated examples, we harnessed generative AI to produce a diverse array of SQLi payloads. This approach significantly reduces the occurrence of hallucinations—a common issue in AI-generated content—by ensuring that generated attacks are both syntactically and semantically valid. The high validation rate of 92.5% against a MySQL database attests to the effectiveness of this method.

Automated Defense Mechanisms: By systematically testing the generated payloads against a vulnerable web application fortified with a WAF, we identified attacks that successfully bypassed existing security measures. These bypassing attacks were then subjected to classification using machine learning algorithms. Leveraging natural language processing techniques, we automatically generated new WAF rules tailored to counter these specific attack patterns. The iterative refinement of WAF defenses culminated in the successful blocking of all previously bypassing attacks.

Our experimental evaluation demonstrated the framework’s efficacy and generality. With the GPT-4o LLM, we generated 514 new SQLi payloads, of which 89% bypassed the ModSecurity WAF equipped with the latest OWASP Core Rule Set. Remarkably, the introduction of just 23 new WAF rules was sufficient to block 475 unique SQLi attacks, highlighting the broad applicability and effectiveness of the generated defenses.

By planning to open-source our framework, we aim to democratize access to advanced cybersecurity tools, enabling a wider range of practitioners to proactively defend against evolving threats. This approach lowers the technical barriers associated with traditional methods, such as manual rule crafting or the use of context-free grammars, and fosters a collaborative environment where defense strategies can be rapidly shared and improved upon.

Our work also brings to light important considerations regarding the dual-use nature of generative AI in cybersecurity. While these technologies offer powerful tools for defenders, they can equally be exploited by malicious actors. The reluctance of some publicly available models to generate attack vectors reflects a broader debate on responsible AI usage. We acknowledge the complexity of this issue and advocate for ongoing dialogue among policymakers, technologists, and the cybersecurity community to establish guidelines that balance innovation with security.

7.1. Future Work

The promising results of our framework open several avenues for future research and development:

Extension to Other Attack Types: The methodology could be adapted to generate and defend against other forms of web application attacks, such as Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) or Remote Code Execution (RCE) exploits, enhancing the overall security landscape.

Real-Time Adaptation: Integrating real-time monitoring and adaptive learning capabilities could enable the WAF to respond dynamically to emerging threats without manual intervention.

Ethical Frameworks and Policy Development: Collaborating with stakeholders to develop ethical guidelines and policies governing the use of generative AI in cybersecurity will be crucial to ensure these tools are used responsibly.

Enhanced Validation Mechanisms: Improving the validation process for generated payloads to include a wider range of database systems and configurations could increase the robustness of the framework.

Machine learning based SQLi detection: Generative AI could be used to generate datasets to train machine-learning based SQLi detection models, so as to improve the robustness of the models.

In summary, our generative AI framework represents a significant advancement in the proactive defense against SQL Injection attacks. By uniting the offensive and defensive potentials of generative AI, we have demonstrated a holistic approach to cybersecurity that not only anticipates and neutralizes current threats but also adapts to future challenges. We believe that this work contributes valuable insights to the cybersecurity field and encourages further exploration into the integration of artificial intelligence for safeguarding critical digital infrastructures.

Appendix A

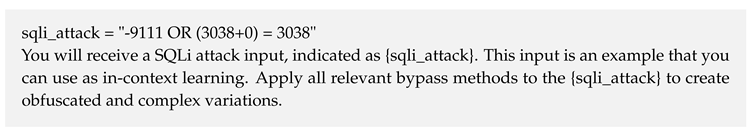

Appendix A.1. Instruction for in-context learning

The model is explicitly informed that the input serves as in-context learning examples for guiding the LLM to generate creative yet logically consistent variations. Then LLM transforms the base input into complex, obfuscated forms using a systematic application of multiple bypass techniques.

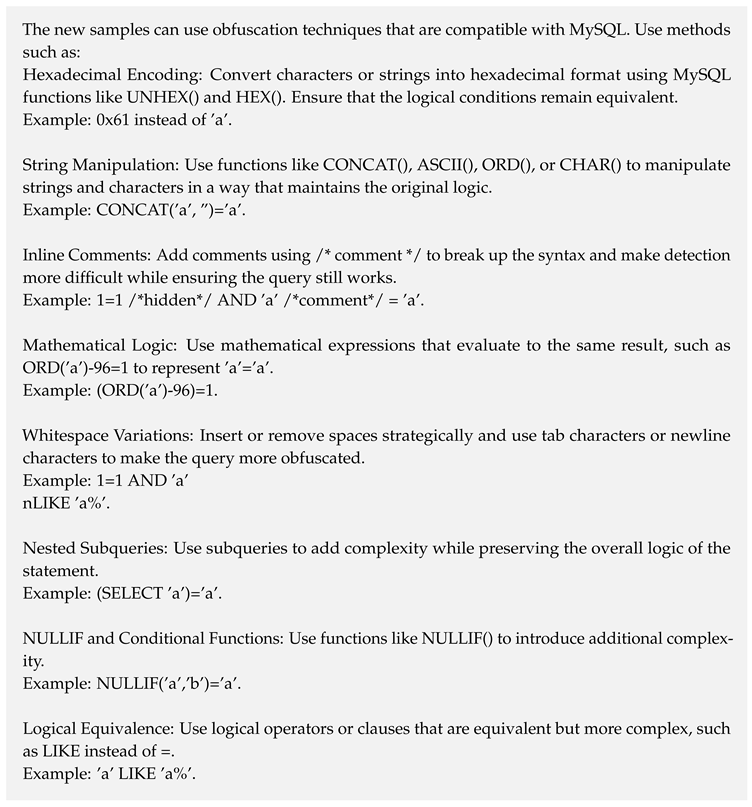

Appendix A.2. List of Bypass Methods

A comprehensive list of obfuscation strategies is provided. Each method includes a brief explanation and an example to guide the LLM in crafting variations:

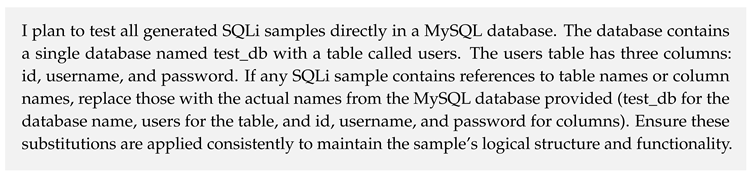

Appendix A.3. Database Context

Context about the database schema is provided, ensuring compatibility of the generated SQLi samples with the actual database environment. This step grounds the variations in practical scenarios.

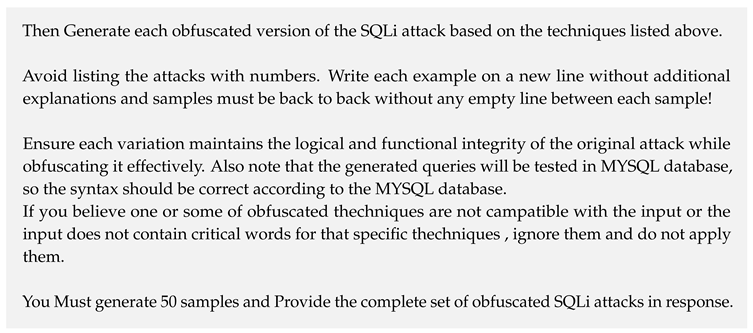

Appendix A.4. Tasks

The prompt mandates the LLM to apply all relevant techniques systematically, ensuring comprehensive exploration of obfuscation strategies while skipping incompatible techniques. The output format is clearly specified, focusing on generating a seamless list of variations for ease of testing. The generated samples must remain functional and syntactically valid for MySQL, ensuring their utility for real-world testing. The prompt emphasizes relevance, instructing the LLM to avoid unnecessary or non-functional transformations, thereby enhancing the quality of the output. The required number of samples ensures a diverse set of obfuscated payloads for robust testing. Ensures the LLM generates a comprehensive output that can be directly used for testing in the specified database environment.

Appendix B

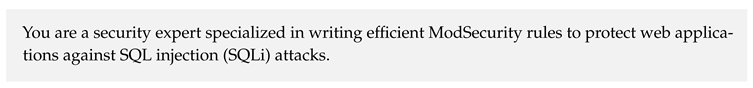

This prompt is a detailed instruction designed to guide LLM in generating ModSecurity SecRules tailored to detect obfuscated SQL injection (SQLi) patterns. Below is an explanation of each element, focusing on how it contributes to the creation of effective and efficient rules:

Appendix B.1. System Role

Appendix B.2. Cluster-Based Organization

The prompt groups SQLi patterns into six clusters, each with unique characteristics and examples. This organization helps the LLM focus on distinct types of obfuscation and simplifies the process of creating tailored rules.

Appendix B.3. Tasks

The task is clearly defined: the LLM must generate rules that detect specific obfuscated SQLi patterns while minimizing false positives. This instruction emphasizes efficiency, precision, and the need for broad pattern coverage. The rules should be presented as a continuous block, which facilitates easy integration into ModSecurity configurations. Comments provide context for each rule, explaining what it detects and why it is effective.

Appendix C

Table A1.

Sample SQL injection generated by GPT-4o.

Table A1.

Sample SQL injection generated by GPT-4o.

| or (SELECT CASE WHEN (1=1 AND ’a’ LIKE CONCAT(’a’, ’%’)) THEN 1 ELSE 0 END) = 1– |

| or (SELECT CASE WHEN (1=1 AND UNHEX(HEX(’a’))=0x61) THEN 1 ELSE 0 END) = 1– |

| -7552 OR (SELECT CASE WHEN (6872=6872 AND (SELECT ’a’)=’a’) THEN 1 ELSE 0 END)=1 |

| -9111 OR (0x0bde+0x0) = 0x0bde |

| or (SELECT 1) = 1 AND (SELECT 1) = 1 AND (SELECT CHAR(52), CHAR(53), CHAR(57), CHAR(53)) = (’4’, ’5’, ’9’, ’5’) – |

| -3520 OR 0 + 8571 = 8571 OR (SELECT CASE WHEN (8571 = 8571 OR ’b’ = ’b’) THEN 1 ELSE 0 END) = 1 – |

| or EXISTS(SELECT COUNT(*) FROM test_db.users AS sys1, test_db.users AS sys2, test_db.users AS sys3, test_db.users AS sys4, test_db.users AS sys5, test_db.users AS sys6, test_db.users AS sys7 WHERE 2462=2462 AND 2716=(SELECT 2716))– |

Appendix D

Table A2.

Sample Modsecurity SecRules generated by GPT-4o.

Table A2.

Sample Modsecurity SecRules generated by GPT-4o.

References

- SQL Injection, 2024. https://owasp.org/www-community/attacks/SQL_Injection. Accessed: 2024-12-02.

- Clarke-Salt, J. SQL injection attacks and defense; Elsevier, 2009.

- OWASP Top Ten Project, 2024. https://owasp.org/www-project-top-ten/, Accessed: 2024-12-02.

- Dermann, M.; Dziadzka, M.; Hemkemeier, B.; Hoffmann, A.; Meisel, A.; Rohr, M.; Schreiber, T. Best practices: use of web application firewalls. The Open Web Security Application Project, OWASP Papers Program 2008.

- Zewe, A. Explained: Generative AI. MIT News 2023.

- GPT-4o: OpenAI’s Optimized GPT-4 Model, 2024. https://openai.com. Accessed: 2024-12-02.

- Gemini: Google’s Multimodal AI Model, 2024. https://deepmind.com. Accessed: 2024-12-02.

- LLaMA: Large Language Model Meta AI, 2024. https://ai.facebook.com. Accessed: 2024-12-02.

- Claude: An AI Assistant by Anthropic, 2024. https://anthropic.com. Accessed: 2024-12-02.

- Gupta, M.; Akiri, C.; Aryal, K.; Parker, E.; Praharaj, L. From chatgpt to threatgpt: Impact of generative ai in cybersecurity and privacy. IEEE Access 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project, M. ModSecurity: Open Source Web Application Firewall, 2024. Accessed: 2024-12-03.

- Foundation, O. OWASP ModSecurity Core Rule Set Project, 2024. Accessed: 2024-12-03.

- Alghawazi, M.; Alghazzawi, D.; Alarifi, S. Detection of sql injection attack using machine learning techniques: a systematic literature review. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 2022, 2, 764–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applebaum, S.; Gaber, T.; Ahmed, A. Signature-based and machine-learning-based web application firewalls: a short survey. Procedia Computer Science 2021, 189, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Ling, X.; Wang, T.; Chen, X.; Ji, S.; Wu, C. AdvSQLi: Generating Adversarial SQL Injections against Real-world WAF-as-a-service. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, D.; Wang, C.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Z. ART4SQLi: The ART of SQL injection vulnerability discovery. IEEE Transactions on Reliability 2019, 68, 1470–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetrio, L.; Valenza, A.; Costa, G.; Lagorio, G. Waf-a-mole: evading web application firewalls through adversarial machine learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 35th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, 2020, pp. 1745–1752.

- Appelt, D.; Panichella, A.; Briand, L. Automatically repairing web application firewalls based on successful SQL injection attacks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 28th international symposium on software reliability engineering (ISSRE). IEEE, 2017, pp. 339–350.

- Hemmati, M.; Hadavi, M.A. Using deep reinforcement learning to evade web application firewalls. In Proceedings of the 2021 18th International ISC Conference on Information Security and Cryptology (ISCISC). IEEE, 2021, pp. 35–41.

- Halder, R.; Cortesi, A. Obfuscation-based analysis of SQL injection attacks. In Proceedings of the The IEEE symposium on Computers and Communications. IEEE, 2010, pp. 931–938.

- Nasereddin, M.; ALKhamaiseh, A.; Qasaimeh, M.; Al-Qassas, R. A systematic review of detection and prevention techniques of SQL injection attacks. Information Security Journal: A Global Perspective 2023, 32, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, A.; Hur, A.; Shahbaz, S.; Masood, M.; Ahmad, H.F. Critical analysis on web application firewall solutions. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Eleventh International Symposium on Autonomous Decentralized Systems (ISADS). IEEE, 2013, pp. 1–6.

- Bandi, A.; Adapa, P.V.S.R.; Kuchi, Y.E.V.P.K. The power of generative ai: A review of requirements, models, input–output formats, evaluation metrics, and challenges. Future Internet 2023, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerriegel, S.; Hartmann, J.; Janiesch, C.; Zschech, P. Generative ai. Business & Information Systems Engineering 2024, 66, 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, P.; Singh, A.K.; Saha, S.; Jain, V.; Mondal, S.; Chadha, A. A systematic survey of prompt engineering in large language models: Techniques and applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.07927 2024.

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.t.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive nlp tasks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 9459–9474. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. A Review of Prominent Paradigms for LLM-Based Agents: Tool Use (Including RAG), Planning, and Feedback Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.05804 2024.

- Talebirad, Y.; Nadiri, A. Multi-agent collaboration: Harnessing the power of intelligent llm agents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.03314 2023.

- Ramos, J.; et al. Using tf-idf to determine word relevance in document queries. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the first instructional conference on machine learning. Citeseer, 2003, Vol. 242, pp. 29–48.

- Tokuda, E.K.; Comin, C.H.; Costa, L.d.F. Revisiting agglomerative clustering. Physica A: Statistical mechanics and its applications 2022, 585, 126433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, E.; Sander, J.; Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Xu, X. DBSCAN revisited, revisited: why and how you should (still) use DBSCAN. ACM Transactions on Database Systems (TODS) 2017, 42, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soewito, B.; Gunawan, F.E.; et al. Prevention Structured Query Language Injection Using Regular Expression and Escape String. Procedia Computer Science 2018, 135, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).