1. Introduction

Amyloidosis is a severe condition resulting from the systemic accumulation of amyloid protein deposits in various tissues, leading to structural and functional abnormalities. It is primarily associated with cardiac and neurological manifestations, with cardiac and renal forms posing significant threats to health and life. Cardiac amyloidosis (CA) primarily manifests as restrictive cardiomyopathy, which can result in heart failure and arrhythmias. Amyloidosis can arise from various types of amyloid proteins, but in Europe, the most prevalent forms are AL (amyloid light-chain) and ATTR (transthyretin) amyloidosis [

1,

2].

The hereditary form of ATTR cardiac amyloidosis (ATTRv-CA) disproportionately afflicts the black Afro-Caribbean population, who when compared to mainly whites with wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis (wt-ATTR-CA), a phenotypically similar condition, present with more advanced disease despite genetic testing may permit early identification [

3].

Current scientific understanding highlights the typically “late” diagnosis of amyloidosis, emphasizing the challenges of achieving an earlier diagnosis. Numerous scientific publications suggest that systemic manifestations might precede the phenotypic presentation of the traditionally recognized cardiac and neurological forms by several years. Patients with ATTR amyloidosis may experience musculoskeletal symptoms 5 to 15 years prior to signs or symptoms of systemic disease [

4,

5,

6]. Carpal tunnel syndrome, the most prevalent non-cardiac symptom in patients with ATTR-CA, often appears years before a formal diagnosis of either wt-ATTR-CA or hereditary ATTRv-CA [

4]. ATTR amyloid deposits could be identified in various tissues of patients with amyloidosis removed during orthopedic procedures including carpal tunnel syndrome, rotator cuff tears, and lumbar canal stenosis [

7].

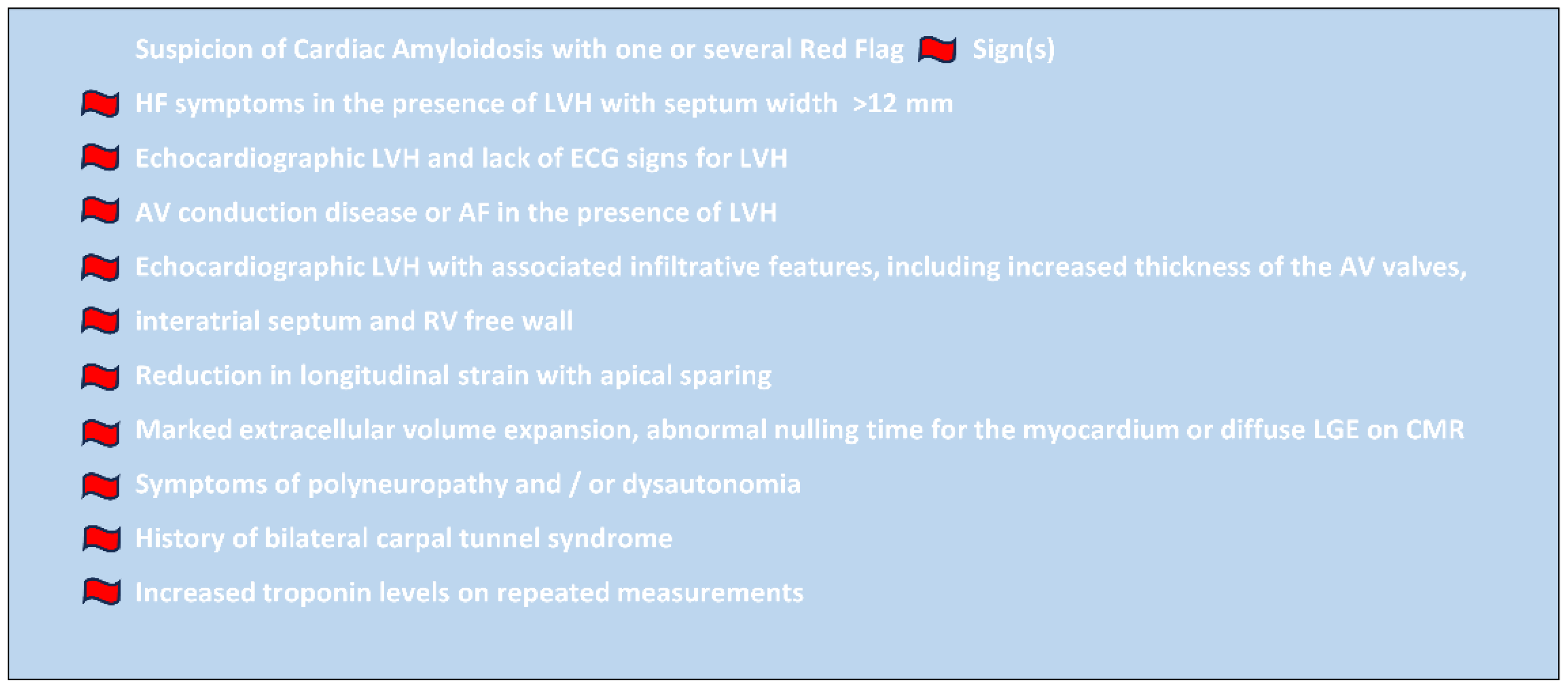

Identifying early manifestations of CA could potentially shorten the diagnostic delay, enabling early therapeutic intervention [

2,

8,

9]. Among these early signs, conduction disorders or other arrhythmias necessitating the implantation of pacemakers or defibrillators, may be an early manifestation of CA. Early signs of CA, often referred to as “red flag” symptoms (

Figure 1), should prompt suspicion of CA and initiate further diagnostic evaluation [

1,

6,

10].

Definitive diagnosis relies on histopathological examination, which involves biopsy procedures that can be particularly challenging and pose risks, especially in cardiac and renal forms of the disease. Historically, a conclusive diagnosis of amyloidosis has been made through a tissue biopsy stained with Congo red [

11]. When observed under polarized light, this reveals the characteristic green birefringence of amyloid deposits, confirming the presence of the disease [

11]. Histological confirmation is still required in cases where both bone scintigraphy (indicating ATTR-CA) and tests for monoclonal protein (indicating potential AL amyloidosis) show abnormalities or are inconclusive [

11]. It is also reasonable to verify and classify amyloid deposits through immunohistochemistry or mass spectrometry [

12]. Mass spectrometry is the currently preferred method for amyloid typing, as immunohistochemistry results are often subtle and can be misinterpreted without significant expertise [

12].

Bone scintigraphy, particularly using 99m-technetium-labeled bisphosphonates, has emerged as a valuable diagnostic tool for ATTR-CA [

13]. This imaging technique can non-invasively detect myocardial uptake of amyloid deposits, offering high sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing ATTR-CA from other forms such as AL-CA after exclusion of monoclonal gammopathy [

13]. 99mTc-scintigraphy for cardiac amyloidosis imaging involves administering 10 to 25 mCi of radiotracer intravenously, followed by planar and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging, typically performed 1 or 3 hours later. The degree of myocardial tracer uptake on planar imaging can be assessed using both qualitative and quantitative grading systems. Qualitative grading compares heart uptake to rib bone uptake, with grade 0 indicating no uptake, grade 1 representing mild uptake (less than rib, or less than bone in the case of 99mTc-DPD), grade 2 showing moderate uptake (equal to rib), and grade 3 indicating severe uptake (greater than rib). Quantitative assessments rely on the heart-to-contralateral (H/CL) ratio (for 99mTc-PYP) or the heart-to-whole body ratio (for 99mTc-DPD and 99mTc-HMDP) [

13]. The limited availability of bone scintigraphy in less equipped healthcare settings may pose a significant barrier to timely and accurate diagnosis of cardiac ATTR amyloidosis.

Both ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias are frequently observed in CA, particularly in ATTR-CA, with their occurrence closely linked to disease progression [

14]. The prognostic significance of sustained and non-sustained ventricular tachycardias remains uncertain, and there are currently no clear guidelines for the use of implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICD) in these patients [

14]. Atrial fibrillation is the most common supraventricular arrhythmia, affecting up to 88% of individuals with ATTR-CA [

14]. Anticoagulation should be considered regardless of the CHADsVA score [

15]. Conduction abnormalities and bradyarrhythmias are also prevalent in ATTR-CA, with up to 40% of patients requiring pacemaker implantation [

14].

The implantation of pacemakers involves creating a pre-pectoral pocket between the superficial skin plane and the deeper muscular plane. One case report described amyloid deposits within the pacemaker pocket of a patient who had already been diagnosed with ATTRv-CA [

16].

The potential for amyloid infiltration in the pacemaker or ICD pocket during the early stages of the disease has not been systematically investigated and warrants further study. As conduction abnormalities and other arrhythmias are linked to amyloidosis, the presence of peripheral deposits in the pacemaker or ICD pocket would not be unexpected.

The current study aims to assess the diagnostic utility of thoracic fat pad biopsy obtained from the pacemaker or ICD pocket as a potential alternative biopsy site for patients with suspicion of systemic amyloidosis. This exploratory, hypothesis generating study will compare the sensitivity and specificity of thoracic fat pad biopsy against standard diagnostic approaches for detecting CA, providing insights into the value of histopathological analysis of fat pad samples collected during pacemaker or ICD implantation. By exploring this previously unstudied method, we aim to determine the clinical yield of an accessible diagnostic tool that could facilitate earlier intervention and improve the management of patients with CA.

2. Methods

Patients with suspicion or diagnosis of CA and indication for pacemaker or ICD implantation or generator change, admitted in our electrophysiology (EP) lab between October 2020 and August 2024, were included into this exploratory, observational, retrospective single center study.

Inclusion criteria are displayed in

Figure 1. All patients were managed in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki (

https://www.wma.net/what-we-do/medical-ethics/declaration-of-helsinki/). Written informed consent from the patients or patients’ legal guardians/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with current legislation and institutional requirements. All patients provided written informed consent prior to the procedure. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University Hospital of Martinique.

Patient and procedure selection were non-randomized and carried out upon the discretion of the electrophysiologist in charge. All study procedures were performed under local anesthesia by two experienced electrophysiologists (AM, RV) or by a fellow electrophysiologist (CM).

The indication for pacemaker and ICD therapy followed current guidelines [

17,

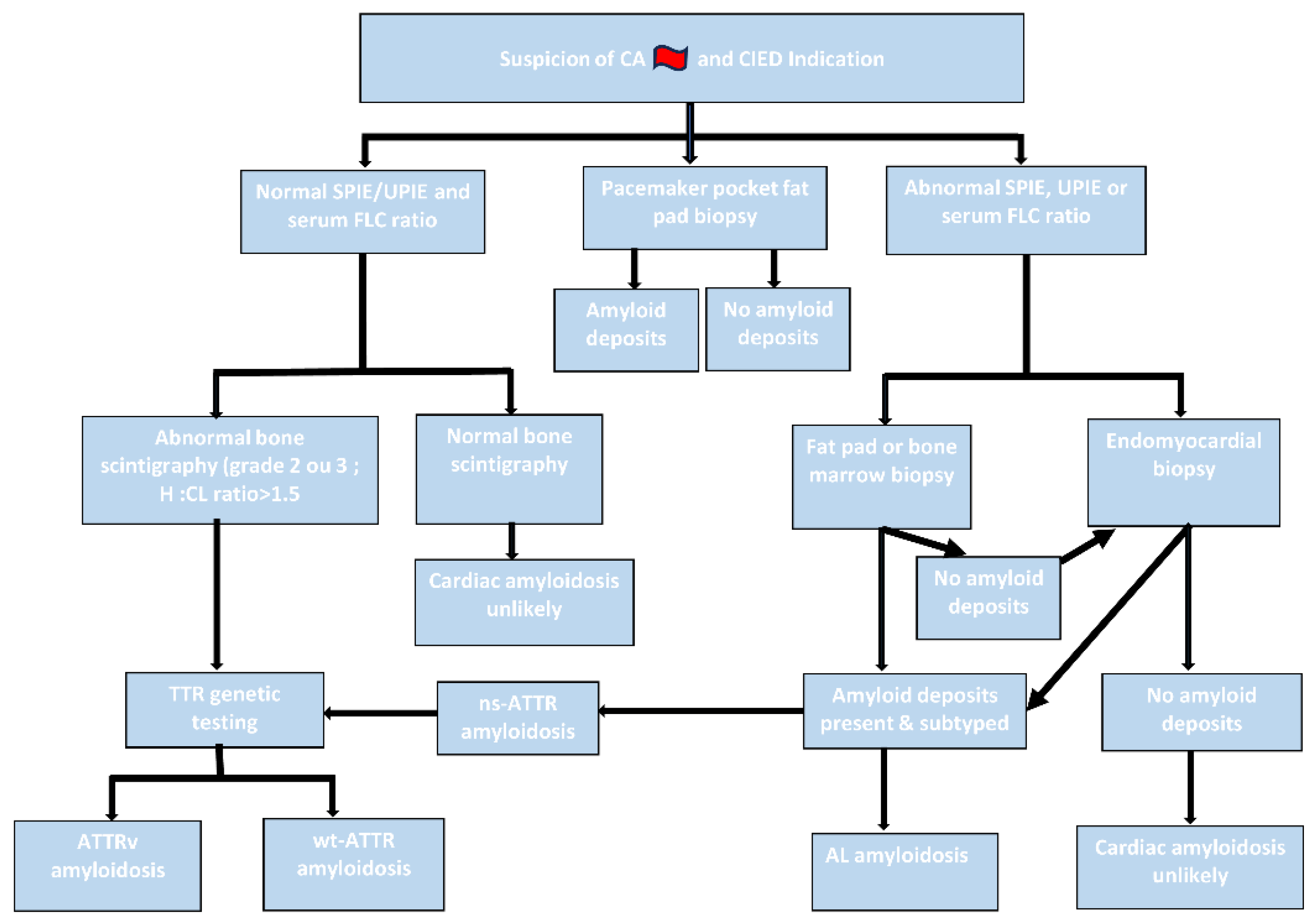

18]. Diagnosis of suspected cardiac amyloidosis (

Figure 1) was confirmed or excluded with current gold standard diagnostic tools (

Figure 2) [

19].

Study data (patient and procedure characteristics) were retrospectively collected. Power calculations were not performed in this exploratory, retrospective study, as it is the first to evaluate this novel fat biopsy site with no prior data to guide sample size estimation. Additionally, limited number of available patients further precluded power calculations.

Statistical analysis was performed with JASP Team (2024, Version 0.19.1). Mean and standard deviations were reported for quantitative variables, while categorical variables were presented as absolute values and percentages. The following tests were accordingly used for group comparisons: t-test, Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test, Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

3. Results

A total of 27 patients were included in this study. Of these, 16 were diagnosed with CA, while 11 did not have CA based on standard diagnostic criteria (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Among the 16 CA patients, 15 (93.8%) had ATTR-CA and 1 (6.3%) had AL-CA (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Of the ATTR-CA patients, 8 individuals were found to carry a heterozygous mutation for the amyloidogenic allele where isoleucine substitutes for valine at codon position 142 (122 of the mature protein) (p.Val142Ile), leading to the diagnosis of hereditary ATTR-CA (ATTRv-CA). Genetic testing was negative in 3 patients, leading to the diagnosis of wild-type ATTR-CA (wt-ATTR-CA). Genetic testing was not performed in 4 patients with ATTR-CA. As no definitive diagnosis of ATTRv-CA or wt-ATTR-CA could be made, we defined those patients as non-specified ATTR-CA (ns-ATTR-CA) (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

No complications occurred, related to the intervention. Baseline characteristics were similar between patients with and without CA, with no significant differences in age, sex, BMI, QRS width, LVEF, renal function, or BNP levels. However, patients with CA had higher baseline heart rate, lower LVEF, and greater septal thickness (

Table 1). Indication for pacemaker therapy was atrioventricular conduction disease in 13 patients (81.3%) in the amyloidosis group and in 10 patients (90.9%) in the group without amyloidosis. Atrioventricular (AV) conduction disease was defined as second degree AV-block, complete AV-block, alternating bundle branch block, bi-fascicular block or AF with bradyarrhythmia. One patient (9.1%) in the group without amyloidosis was diagnosed with symptomatic sick sinus syndrome. Three patients received an ICD. ICD indications were LVEF of 30% and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia in a 63 year-old patient with wt-ATTR-CA, LVEF of 30% in a 64 year-old patient with ATTRv-CA and LVEF of 28% in a 56 year-old patient with AL-CA.

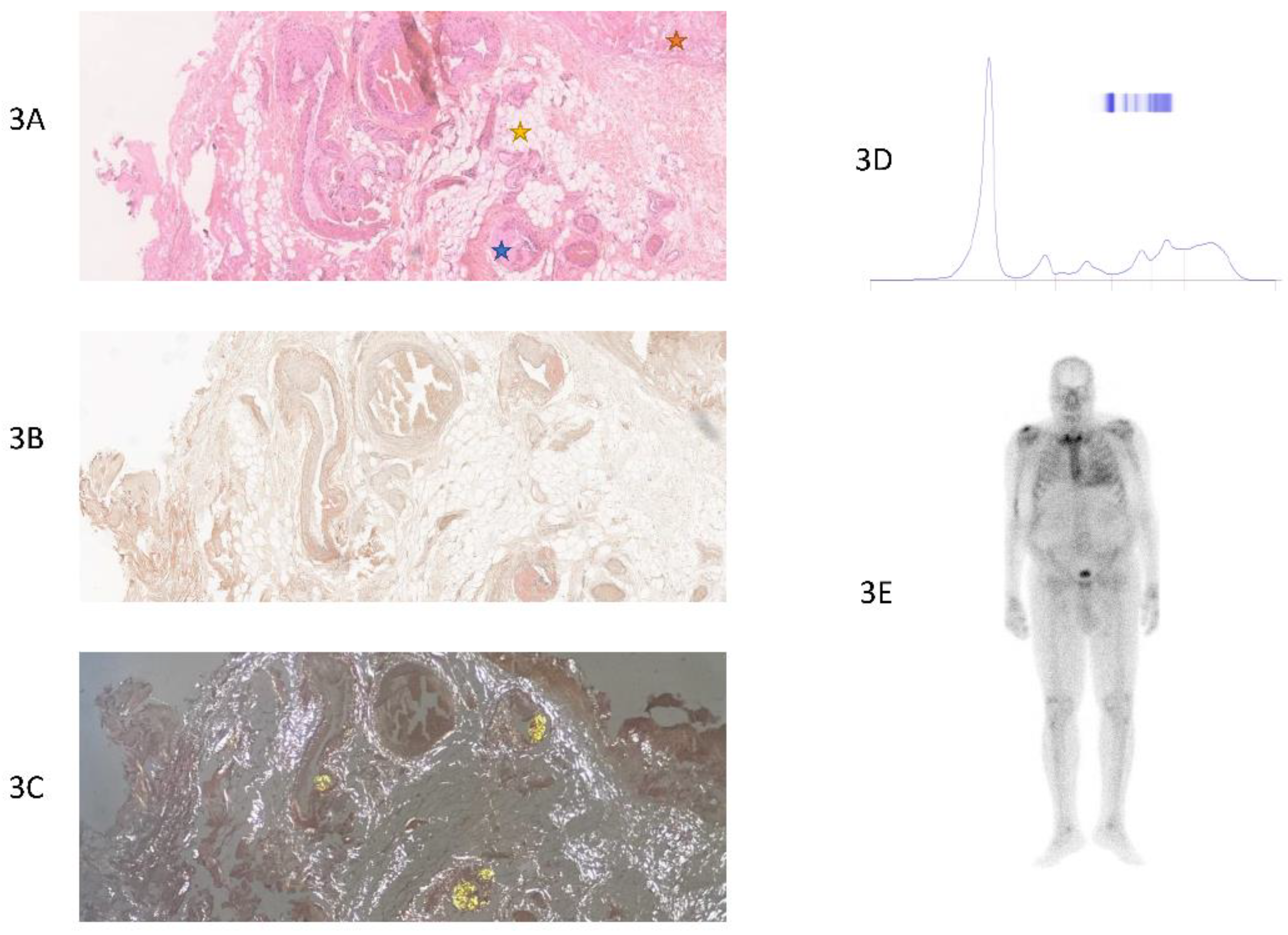

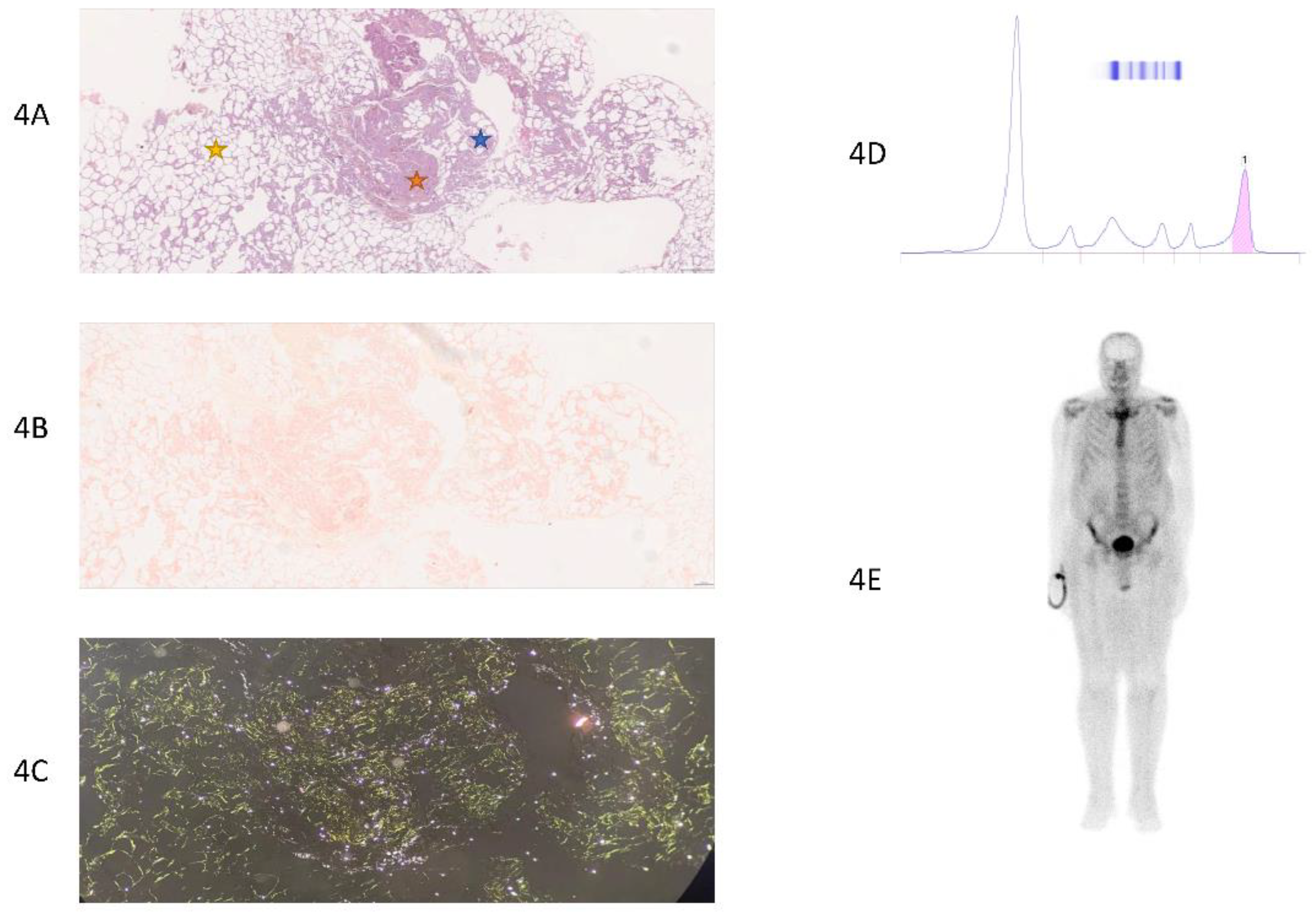

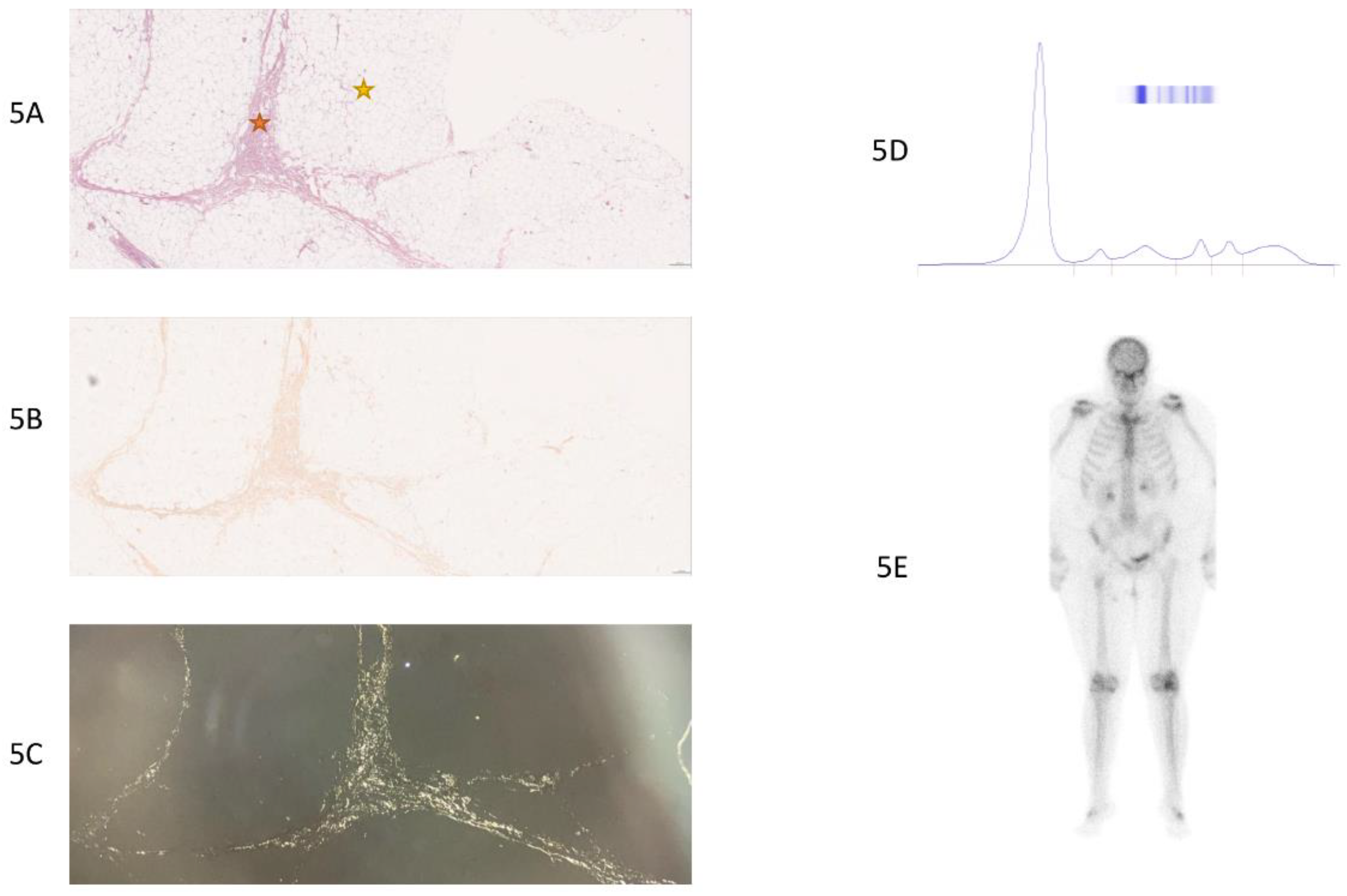

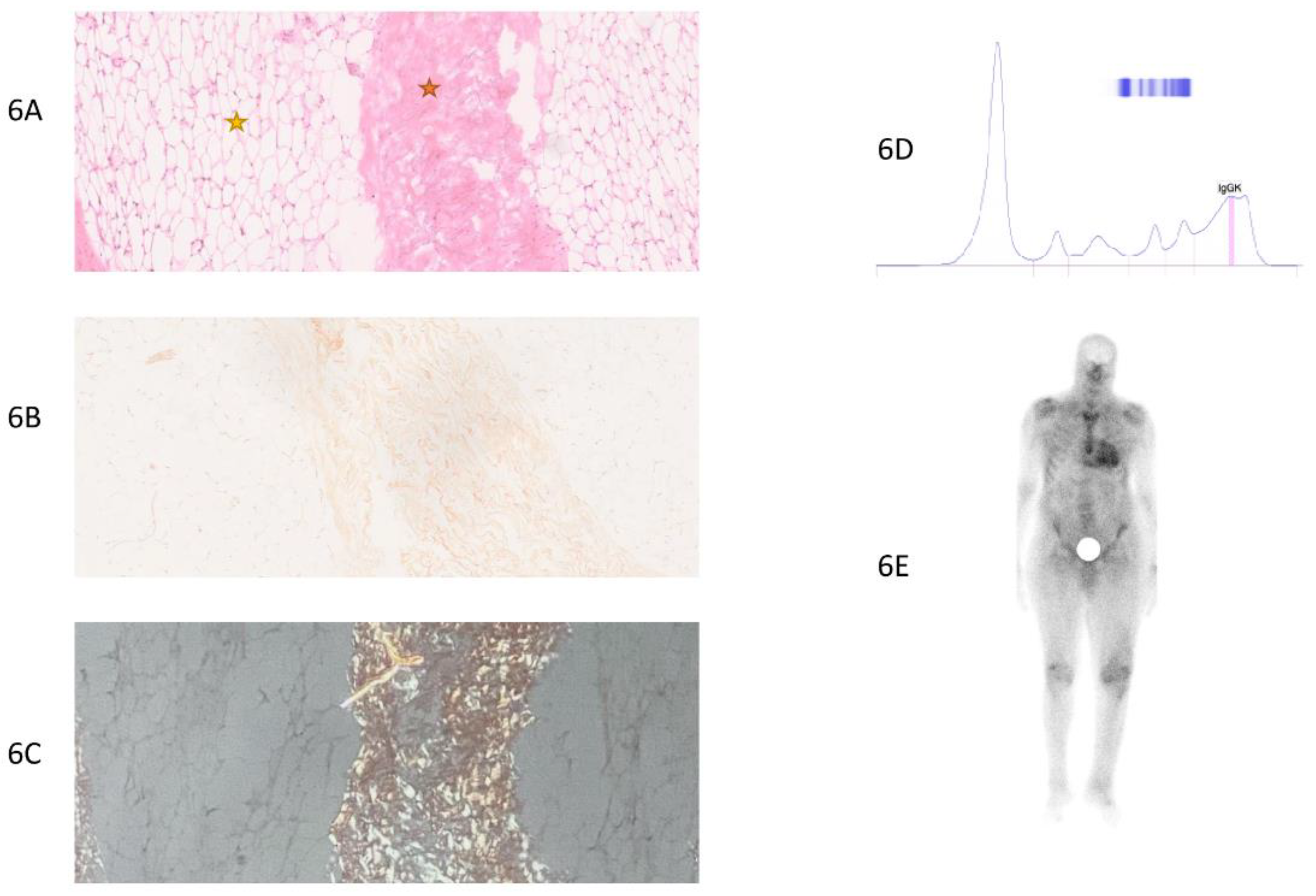

The histopathological analysis showed a specificity of 100% and a sensitivity of 31.3% in the studied cohort (

Table 3).

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 provide examples of two true-positive cases, one true-negative and one false-negative case. With no false-positive results, the positive predictive value (PPV) based on the cohort data was 100%, indicating that all positive biopsy results were true positives for CA. When accounting for the cohort prevalence of 59.3%, the PPV was calculated to be 18.5%, reflecting the diagnostic performance in the context of this specific population. The negative predictive value (NPV) was 50%, indicating that half of the negative biopsies were false negatives (

Table 3).

As previous studies have demonstrated a lower sensitivity of abdominal fat pad biopsy in patients with ATTR-CA compared to those with AL-CA, we separately analyzed the sensitivity and specificity for ATTR-CA, excluding the patient with AL-CA. Sensitivity was again found to be poor at 26.7%, with a specificity at 100% (

Table 4).

In our study, we did not routinely perform biopsies from the abdominal fat pad. Therefore, fat pad biopsies from only eight patients could be compared with the results from thoracic fat pad biopsies. Three patients with evidence of amyloid in the abdominal fat pad biopsy had also evidence of amyloid in the thoracic fat pad biopsy. One of them was diagnosed with ns-ATTR-CA (grade 3 myocardial uptake), one with ATTRv-CA (grade 4 uptake) and one with AL-CA. Five patients without evidence of amyloid in the abdominal fat pad biopsy had also no evidence of amyloid in the thoracic fat pad biopsy (p=0.018). Among the five patients without amyloid evidence in their abdominal fat pad biopsies, two had ATTRv-CA with grade 2 and 3 myocardial uptake (false negative cases), respectively, while three showed no evidence of CA (true negative cases) based on standard diagnostic criteria (p=0.196). In this group of eight patients with thoracic and abdominal fat pad biopsies we found an excellent correlation with identical results from both anatomical sites (p=0.018). In this small group, thoracic and abdominal fat pad biopsies detected only three out of five cases with CA (sensitivity 60%, specificity 100%, p=0.196). Seven patients also received a salivary gland biopsy. We found three true positive cases, four false negative cases, when compared to gold standard diagnostic.

4. Discussion

The prevalence of amyloidosis in the general population of Martinique is unknown. However, deducing from the known 3.43% prevalence of the p.Val142Ile variant in African Americans and assuming disease manifestation in 10-15% of carriers, one could estimate a prevalence of manifest ATTRv-CA between 0.3% and 0.5% in Martinique, a Caribbean island where approximately 90% of the population is of African descent [

3,

20]. The prevalence of manifest amyloidosis in African countries is also unknown but is likely to increase in the future due to the increasing life expectancy [

21]. This emphasizes the need for reliable and affordable diagnostic tools.

In patients with clinical amyloidosis (cardiac or neurological), the diagnostic yield of peripheral biopsies varies across studies. Specificity rates are excellent, consistently reaching 100%, while sensitivity rates show more variation. Depending on the etiology and in the most favorable studies, abdominal fat biopsies demonstrate a sensitivity from 58 to 95%, and rectal mucosal biopsies range from 74 to 95% [

22,

23,

24]. Biopsies of accessory salivary glands exhibit sensitivities between 45 and 61%, and renal biopsies range from 85 to 100% [

25,

26,

27]. Additionally, some studies report a very high diagnostic yield from endomyocardial biopsies in characteristic cardiac amyloidosis cases [

11,

28].

In this exploratory analysis, histopathological analysis of thoracic fat pad sample from the pacemaker or ICD pocket could diagnose only five from 16 patients with CA. 11 from in total 16 patients with diagnosis of CA had no evidence of amyloid in the histopathological analysis of the thoracic fat pad biopsy. Thus, the sensitivity of histopathological analysis to diagnose CA was poor with only 31%. Noteworthy, there were no false positive findings.

No correlation was observed between the myocardial uptake in bone scintigraphy and the thoracic fat pad biopsy results. Even though no wt-ATTR-CA was among the cases with positive amyloid finding in the thoracic fat pad sample, no reasonable conclusion can be drawn due to the small sample size.

Although this observation should be interpreted with great caution due to the small number of cases, we found in a group of eight patients with thoracic and abdominal fat pad biopsies an excellent correlation with identical results from both anatomical sites (p=0.018).

The limited sensitivity of 31% at thoracic fat pad biopsy in our study with 94% of patients with ATTR-CA is similar to findings of previous studies on abdominal fat pad aspiration. These studies demonstrated that sensitivity of abdominal fat pad aspiration greatly varies depending on the type of amyloid protein. Sensitivity for diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis using abdominal fat pad aspiration or biopsy was 15% in wt-ATTR-CA, 39% in ns-ATTR-CA and 45% in ATTRv-CA, whereas sensitivity in patients with AL-CA is up to 84-90% [

29,

30].

Limitations of this study include the small sample size (n=27), the retrospective single-center design, and the lack of power calculations due to the exploratory nature of the research, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader populations.

5. Conclusions

Our initial hypothesis that cardiac amyloidosis (CA) could be reliably diagnosed through histopathological analysis of thoracic fat pad samples obtained from pacemaker or ICD pockets was not confirmed. In this study, involving an Afro-Caribbean population with 94% diagnosed with ATTR-CA, thoracic fat pad biopsy demonstrated a sensitivity of 31% and specificity of 100% compared to protein electrophoresis or technetium-labeled bisphosphonate bone scintigraphy as standard diagnostic tools. Given its low diagnostic yield, histopathological analysis of thoracic fat pad biopsies cannot currently be recommended as a standard diagnostic tool for ATTR-CA. However, it may still hold significant value in diagnosing AL-CA, potentially obviating the need for further invasive procedures. This study underscores the importance of utilizing established standard diagnostic criteria for CA while also highlighting the need for less expensive and more accessible diagnostic methods, especially in resource-limited settings.

Credit statement

Cedric Mvita: data curation, investigation, writing of the original draft; Romain Vergier: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, editing of the original draft; Mathilda Simeon: formal analysis, investigation, editing of the original draft; Nathan Buila Bimbi: supervision; Nathan Malka: conceptualization; Karima Lounaci: data curation, validation; Maria Herrera Bethencourt: data curation, validation; Karim Farid: methodology, supervision; Arnt Kristen: methodology, supervision; Rishika Banydeen: conceptualization, methodology; Astrid Monfort: methodology, supervision; Jocelyn Inamo: methodology, supervision; Andreas Müssigbrodt: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing of the original draft

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, (AM), upon reasonable request.

Conflict of interest

None declared

References

- Maurer, M.S.; Bokhari, S.; Damy, T.; Dorbala, S.; Drachman, B.M.; Fontana, M.; Grogan, M.; Kristen, A.V.; Lousada, I.; Nativi-Nicolau, J.; et al. Expert Consensus Recommendations for the Suspicion and Diagnosis of Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. Circ: Heart Failure 2019, 12, e006075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittleson, M.M.; Maurer, M.S.; Ambardekar, A.V.; Bullock-Palmer, R.P.; Chang, P.P.; Eisen, H.J.; Nair, A.P.; Nativi-Nicolau, J.; Ruberg, F.L. ; On behalf of the American Heart Association Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology Cardiac Amyloidosis: Evolving Diagnosis and Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, K.B.; Mankad, A.K.; Castano, A.; Akinboboye, O.O.; Duncan, P.B.; Fergus, I.V.; Maurer, M.S. Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis in Black Americans. Circ: Heart Failure 2016, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.P.; Hanna, M.; Sperry, B.W.; Seitz, W.H. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Potential Early, Red-Flag Sign of Amyloidosis. The Journal of Hand Surgery 2019, 44, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, J.; Alvarez, J.; Teruya, S.; Castano, A.; Lehman, R.A.; Weidenbaum, M.; Geller, J.A.; Helmke, S.; Maurer, M.S. Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Are Common among Patients with Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis, Occurring Years before Cardiac Amyloid Diagnosis: Can We Identify Affected Patients Earlier? Amyloid 2017, 24, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papoutsidakis, N.; Miller, E.J.; Rodonski, A.; Jacoby, D. Time Course of Common Clinical Manifestations in Patients with Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis: Delay From Symptom Onset to Diagnosis. Journal of Cardiac Failure 2018, 24, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, T.; Ueda, M.; Jono, H.; Irie, H.; Sei, A.; Ide, J.; Ando, Y.; Mizuta, H. Wild-Type Transthyretin-Derived Amyloidosis in Various Ligaments and Tendons. Human Pathology 2011, 42, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobner, S.; Zarro, S.; Wieser, F.; Kassar, M.; Alaour, B.; Wiedemann, S.; Bakula, A.; Caobelli, F.; Stortecky, S.; Gräni, C.; et al. Effect of Timely Availability of TTR-Stabilizing Therapy on Diagnosis, Therapy, and Clinical Outcomes in ATTR-CM. JCM 2024, 13, 5291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, M.S.; Schwartz, J.H.; Gundapaneni, B.; Elliott, P.M.; Merlini, G.; Waddington-Cruz, M.; Kristen, A.V.; Grogan, M.; Witteles, R.; Damy, T.; et al. Tafamidis Treatment for Patients with Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witteles, R.M.; Bokhari, S.; Damy, T.; Elliott, P.M.; Falk, R.H.; Fine, N.M.; Gospodinova, M.; Obici, L.; Rapezzi, C.; Garcia-Pavia, P. Screening for Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy in Everyday Practice. JACC: Heart Failure 2019, 7, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, N.M.; Arruda-Olson, A.M.; Dispenzieri, A.; Zeldenrust, S.R.; Gertz, M.A.; Kyle, R.A.; Swiecicki, P.L.; Scott, C.G.; Grogan, M. Yield of Noncardiac Biopsy for the Diagnosis of Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. The American Journal of Cardiology 2014, 113, 1723–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, T.; Gilbertson, J.A.; Mangione, P.P.; Rowczenio, D.; Rendell, N.B.; Canetti, D.; Lachmann, H.J.; Wechalekar, A.D.; Bass, P.; Hawkins, P.N.; et al. The Complementary Role of Histology and Proteomics for Diagnosis and Typing of Systemic Amyloidosis. The Journal of Pathology CR 2019, 5, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M.; Ruberg, F.L.; Maurer, M.S.; Dispenzieri, A.; Dorbala, S.; Falk, R.H.; Hoffman, J.; Jaber, W.; Soman, P.; Witteles, R.M.; et al. Cardiac Scintigraphy With Technetium-99m-Labeled Bone-Seeking Tracers for Suspected Amyloidosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2020, 75, 2851–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresi, L.; Trimarchi, G.; Liotta, P.; Restelli, D.; Licordari, R.; Carciotto, G.; Francesco, C.; Crea, P.; Dattilo, G.; Micari, A.; et al. Electrocardiographic Patterns and Arrhythmias in Cardiac Amyloidosis: From Diagnosis to Therapeutic Management—A Narrative Review. JCM 2024, 13, 5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelder, I.C.; Rienstra, M.; Bunting, K.V.; Casado-Arroyo, R.; Caso, V.; Crijns, H.J.G.M.; De Potter, T.J.R.; Dwight, J.; Guasti, L.; Hanke, T.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation Developed in Collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). European Heart Journal 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribbin, G.M. Diagnosis of Amyloidosis by Histological Examination of Subcutaneous Fat Sampled at the Time of Pacemaker Implantation. Heart 2002, 87, 7e–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeppenfeld, K.; Tfelt-Hansen, J.; De Riva, M.; Winkel, B.G.; Behr, E.R.; Blom, N.A.; Charron, P.; Corrado, D.; Dagres, N.; De Chillou, C.; et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death. European Heart Journal 2022, 43, 3997–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glikson, M.; Nielsen, J.C.; Kronborg, M.B.; Michowitz, Y.; Auricchio, A.; Barbash, I.M.; Barrabés, J.A.; Boriani, G.; Braunschweig, F.; Brignole, M.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on Cardiac Pacing and Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. EP Europace 2022, 24, 71–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witteles, R.M.; Liedtke, M. AL Amyloidosis for the Cardiologist and Oncologist. JACC: CardioOncology 2019, 1, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, D.R.; Alexander, A.A.; Tagoe, C.; Buxbaum, J.N. Prevalence of the Amyloidogenic Transthyretin (TTR) V122I Allele in 14 333 African–Americans. Amyloid 2015, 22, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Life Expectancy Projections. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/future-life-expectancy-projections (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Li, T.; Huang, X.; Cheng, S.; Zhao, L.; Ren, G.; Chen, W.; Wang, Q.; Zeng, C.; Liu, Z. Utility of Abdominal Skin plus Subcutaneous Fat and Rectal Mucosal Biopsy in the Diagnosis of AL Amyloidosis with Renal Involvement. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libbey, C.A. Use of Abdominal Fat Tissue Aspirate in the Diagnosis of Systemic Amyloidosis. Arch Intern Med 1983, 143, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guy, C.D.; Jones, C.K. Abdominal Fat Pad Aspiration Biopsy for Tissue Confirmation of Systemic Amyloidosis: Specificity, Positive Predictive Value, and Diagnostic Pitfalls. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2001, 24, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercan, R.; Bıtık, B.; Tezcan, M.E.; Kaya, A.; Tufan, A.; Özturk, M.A.; Haznedaroglu, S.; Goker, B. Minimally Invasive Minor Salivary Gland Biopsy for the Diagnosis of Amyloidosis in a Rheumatology Clinic. ISRN Rheumatology 2014, 2014, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporali, R.; Bonacci, E.; Epis, O.; Bobbio-Pallavicini, F.; Morbini, P.; Montecucco, C. Safety and Usefulness of Minor Salivary Gland Biopsy: Retrospective Analysis of 502 Procedures Performed at a Single Center. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2008, 59, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Suarez, M.L.; Zhang, P.; Nasr, S.H.; Sathick, I.J.; Kittanamongkolchai, W.; Kurtin, P.J.; Alexander, M.P.; Cornell, L.D.; Fidler, M.E.; Grande, J.P.; et al. The Sensitivity and Specificity of the Routine Kidney Biopsy Immunofluorescence Panel Are Inferior to Diagnosing Renal Immunoglobulin-Derived Amyloidosis by Mass Spectrometry. Kidney International 2019, 96, 1005–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellikka, P.A. Endomyocardial Biopsy in 30 Patients With Primary Amyloidosis and Suspected Cardiac Involvement. Arch Intern Med 1988, 148, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, D.; Dong, F.; Chi, H. Diagnostic Sensitivity of Abdominal Fat Aspiration Biopsy for Cardiac Amyloidosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Surg Pathol 2024, 32, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quarta, C.C.; Gonzalez-Lopez, E.; Gilbertson, J.A.; Botcher, N.; Rowczenio, D.; Petrie, A.; Rezk, T.; Youngstein, T.; Mahmood, S.; Sachchithanantham, S.; et al. Diagnostic Sensitivity of Abdominal Fat Aspiration in Cardiac Amyloidosis. European Heart Journal 2017, 38, 1905–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).