1. Introduction

The U.S. mandates 5-year rotation of lead audit partners

as a solution to the potential independence problems linked to auditor tenure.

Regulators in Europe and in the U.S., however, seem unconvinced that partner

rotation is an effective solution to the tenure-related independence problem.

For instance, in Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, the European Union requires full

auditor rotation, noting,

“Rotation of the key audit partner within an audit

firm is insufficient because the main focus of the audit firm remains client

retention. A new partner would be under pressure to retain a long-standing

client of the firm. Mandatory audit firm rotation will help reduce excessive

familiarity between the auditor and its clients, limit the risks of carrying

over repeated inaccuracies, …, promoting genuine professional skepticism”

(European Commission 2011, Memo 14-427).

In 2017, the Public Company Accounting Oversight

Board (PCAOB) amended the Auditing Standard (AS) 3101 to require audit reports

to disclose the first year the auditor began serving consecutively as the client’s

auditor and to include a statement that the auditor is required to be

independent (PCAOB, 2017). The amendment is, in effect, PCAOB’s continuing

concerns about the possible effects of auditor tenure on auditor independence.

Dunn, Lundstrom, and Wilkins (2021) show that the new disclosures have indeed

resulted in an increase in votes against reappointing auditors. Singer and

Zhang (2018) also observe that partner rotation does not eliminate the negative

effects of long audit firm tenure. The implication is that partner rotation is

not an effective counter to the observed independence problems linked to the

audit firm’s tenure. What then, if any, is the source of the noted tenure

effect?

As a new insight, this study examines whether

auditor independence shifts during their life cycle in their clients as a

function of the life cycle phases—entry, adjustment, and recursion

phases (described in Section 3). In

particular, the study examines whether outcomes of auditors’ decisions that

convey acts of auditor independence follow a systematic pattern across the

phases of the auditors’ life cycle in client firms. The analysis draws from the

Executives’ Seasons hypothesis (Hambrick and Fukutomi 1991) and proposes

that new engagement auditors face pressures during entry to respond to their

professional mandate and maintain a high level of independence. Accordingly,

auditors are expected to exercise a high level of independence during this

phase. With a successful entry, the pressures to exercise strict independence

in audit decisions wane and auditors ease their stance on independence. (The

intense regulatory scrutiny that characterizes early-period audits dies down

over time, and auditors may then relax their stance on independence due to the

efforts that may be needed to maintain high level of independence). In the

final phase, recursion, the pressures and vigor that characterized

earlier audit decisions give way to indifference caused by repetitive audits of

the same client. During this period, auditors rely more on the client and

resorts to “checking the boxes.”

To test this view, the required disclosures under

SEC Regulation S-K are used to identify events that reflect auditors’ exercise

of independence. In particular, auditor changes following auditor-client

disputes as reported under Regulation S-K are used as signals of auditors’

exercise of independence. The choice of this instrument is based on several

factors. First, the actual exercise of independence is unobservable and must be

ascertained from outcomes that depict acts of independence. Second, auditor

changes stemming from auditor-client disputes more clearly reflect the

auditor’s resolve to reject the client’s demand for more favorable audit

decisions (Notably, auditor-client disagreements are

frequent and often resolved without any changes in the auditor-client relation.

By contrast, auditor change following auditor-client disputes depicts the

auditor’s unwillingness to side with the client -- a clear break from the

client. The contention in this study is that such acts have temporal pattern

over the phases of the auditors’ life cycle in clients). The tests begin

by plotting the distribution of event-related auditor changes across years of

the auditors’ tenure. Next, the Cox proportional hazard model of

dispute-related auditor exit is fitted on the three life-cycle phases and other

covariates linked to such auditor exits. The life-cycle phases permit tests of

the extent to which the hazard rates are time-dependent (see, e.g., Moreau,

O’Quigley, and Mesbah 1985, for tests of time-varying hazard rates).

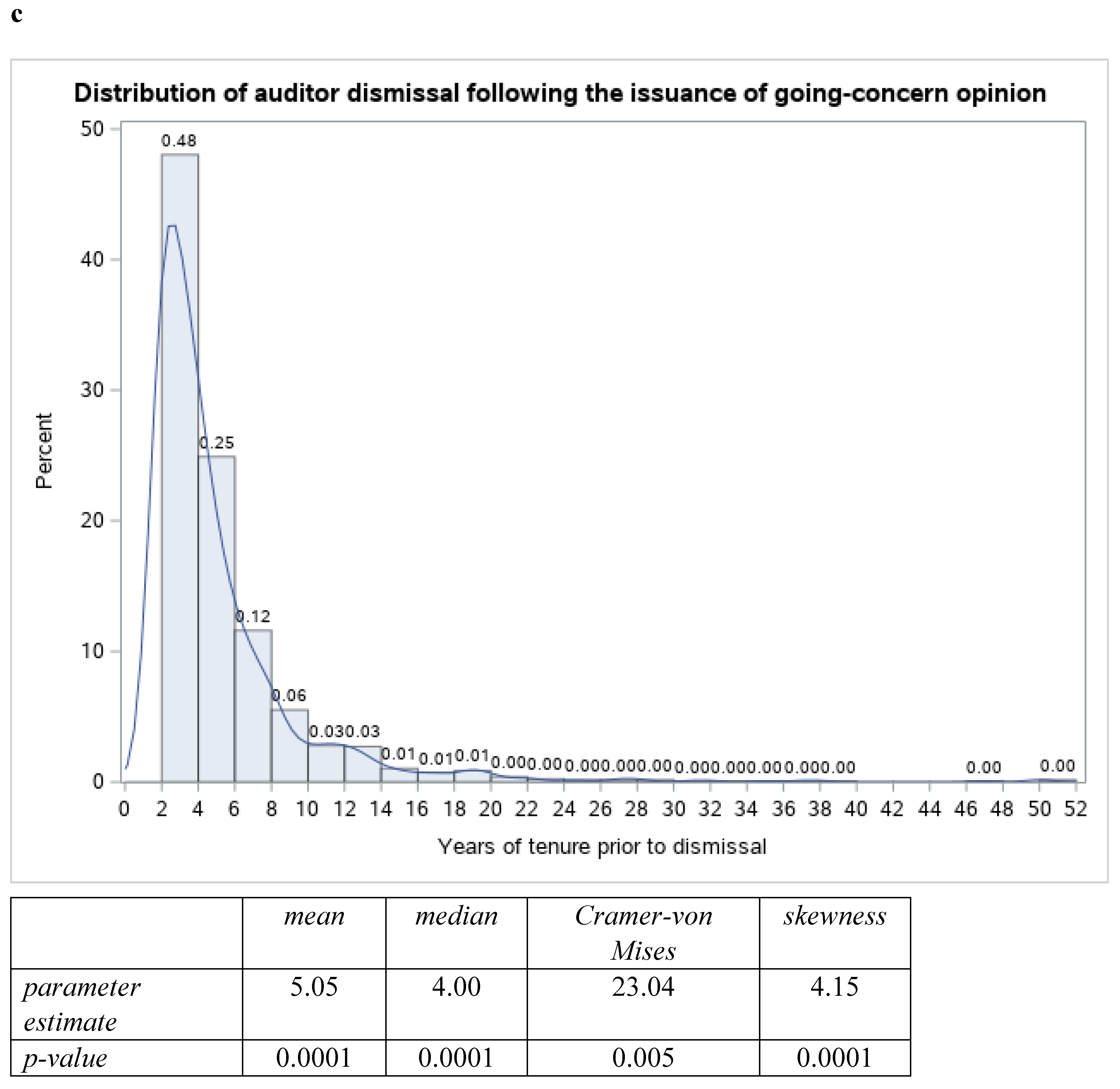

The results show that dispute-related auditor

changes are clustered around the early years of tenure: 65 percent of auditor

resignations, 60 percent of auditor dismissals, and 75 percent of auditor

dismissals related to going-concern opinion (GCO) occur in the first six years

of the auditors’ tenure. Fewer than 10 percent of such auditor changes occurs

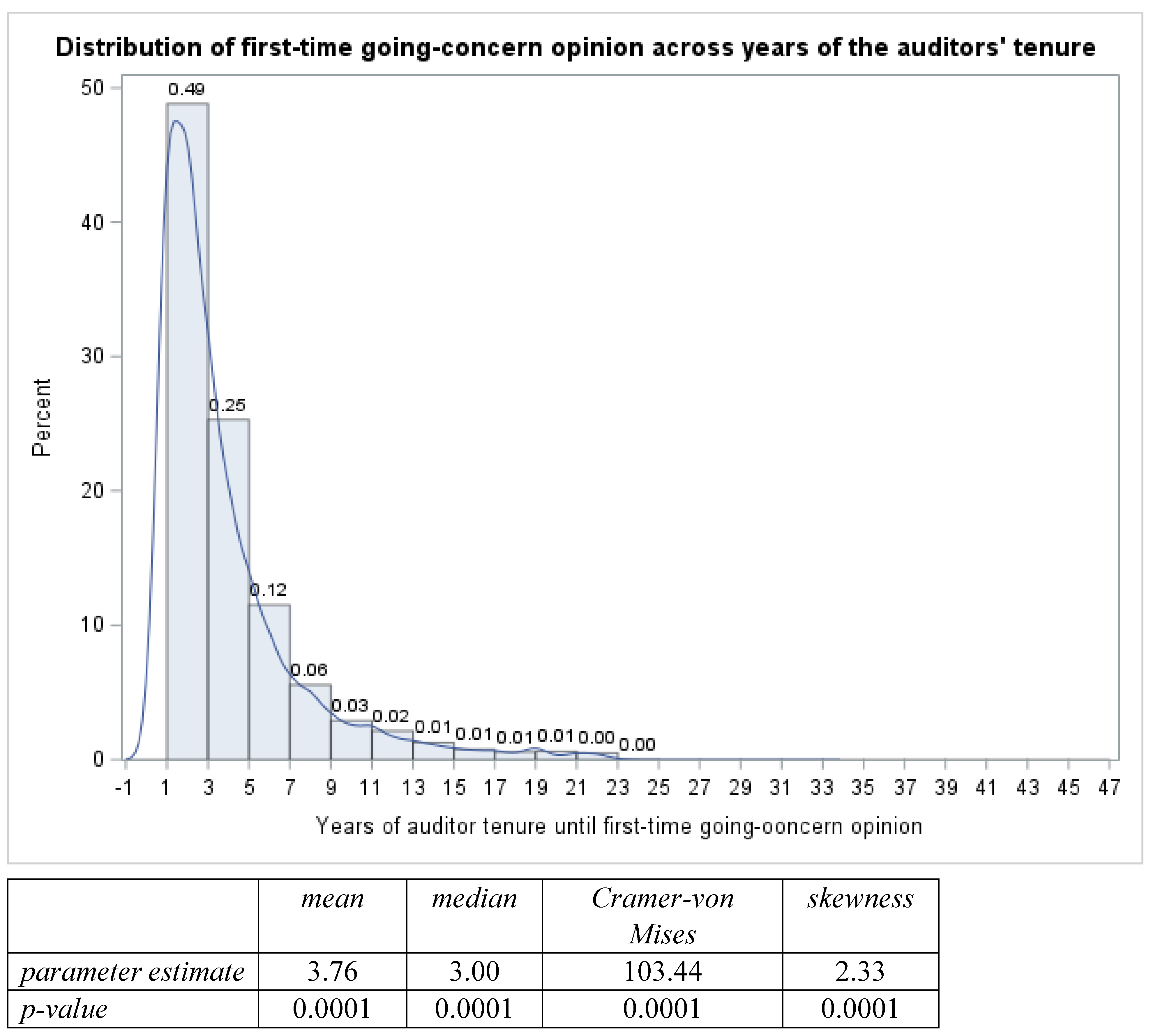

after 15 years of tenure. The temporal pattern of first-time going-concern

opinion (GCO) is similar: 64 percent of the GCOs occur in the first three years

and 75 percent of the GCOs is in the first five years of tenure. Only 8 percent

of such GCOs is issued after 11 years. Based on the hazard model, the hazard of

dispute-related auditor changes is highest during the early years of the

auditors’ tenure and declines afterwards, independent of factors commonly

linked to auditor changes. A logit analysis of first-time GCOs yields similar

results. These findings corroborate the Professional-mandate view that

auditors exercise the highest levels of independence during entry, contrary to

the view that auditors acquiesce to clients’ demand during entry to secure

incumbency. The results also show that the clustering of auditor dismissals

around the early years of the auditors’ tenure are much less related to the

known determinants of auditor dismissal.

In summary, this study uses the theory on group

life cycle to shed light on an often-ignored source of auditors’

independence—"tenure phase” itself. Using incidents of dispute-related

auditor changes as a more direct indicator of auditor independence, the study

provides robust evidence of time-related variation in auditors’ acts of

resisting clients’ pressure. In addition, the high incidents of dispute-related

auditor changes during the auditors’ entry years suggest that auditors care

more about their professional mandate during their early tenure years. It is

also notable that auditor dismissals are unrelated to the events commonly

linked to such decisions. This suggests that the disclosures are less effective

in conveying key factors surrounding the dismissals. Policy-wise, the study

reinforces the merits of re-examining audit-firm tenure and the number of years

an auditor may audit the same client.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows: Section

two provides a brief background on the concerns about the effects of auditor

tenure on auditor behavior. Section three develops the hypotheses. Section

fours outlines the empirical design, comprising empirical models, variables

definition, and sampling. Section five presents the results, and Section six

concludes the study.

2. Background

The U.S. adopts audit partner rotation as a

solution to the tenure-independence problem. Stakeholders, however, continue to

raise concerns about the effects of audit firm tenure. (Many studies focus on

the impact of partner tenure on audit outcomes (e.g., Manry, Mock, and Turner,

2008; Litt, Sharma, Simpson, and Tanyi, 2014; Lennox, Wu, and Zhang, 2014;

Laurion, Lawrence, and Ryan, 2017; Gipper, Hail, and Leuz, 2021). However,

regulators continue to stress threats to independence arising from audit firm

tenure). In a Concept Release, the PCAOB (2011a) amplifies the concern

by noting that putting a limit on the continuous stream of revenues that

an auditor may receive from one client would alleviate the pressure that a

client can put on the auditor for more favorable audits and offer an

opportunity for a fresh look at the client’s financial reporting. In a recent

speech about tenure disclosure requirements under AS 3101, the chief auditor of

the PCAOB, Marty Baumann, observes:

Some academic research concludes, and others share

this view, that short-term tenure, or first year audits, present risk to

investors because the auditor may not be sufficiently aware of risks within the

company, especially at a large complex multi-national. Other research suggests,

and many others share this differing view, that long-term auditor-company

relationships adversely affect audit quality. Does the engagement partner

auditing a company where the relationship has existed for, say, 50 years worry

not only about the audit but also about the risk of losing the long-standing

"crown jewel" client? Could this affect his or her decision making? I

don't know the answer to which situation poses greater risk to audit quality

but I do know that investors have expressed an interest in tenure, either way.

(Baumann, December 10, 2013).

Recently, the Institutional Shareholder Services

and Glass Lewis (a corporate governance advisory firm) recommend voting against

a proposal to ratify the re-appointment of KPMG as the GE’s auditor in the 2018

GE annual shareholders meeting, citing audit quality and auditor long tenure as

the underlying factor (Posner 2018). In its recommendation, Glass Lewis

observes that the long relationship between KPMG and GE raises questions about

the effectiveness of the firm’s audits. (There is a view that, with longer

tenure, auditors have more client-specific knowledge that allows them to

perform higher quality audits (e.g., Sorenson, Grove, and Selto, 1983;

Loebbecke,Eining, and Willingham, 1989; Krishnan and Krishnan, 1997; Bell and

Carcello, 2000; Johnson, Khurana, and Reynolds, 2002; Geiger and Raghunandan,

2002; Myers, J., Myers L, and Omer, 2003; Carcello and Nagy, 2004; Gosh and

Moon, 2005; Stanley and DeZoort, 2007; Chen, Lin, and Lin, 2008; Jenkins and

Velury, 2008; Cassell, Myers, J., and Myers L., 2016). However, the audit

quality issues due to deficiency in client-specific knowledge are distinct from

audit decisions driven by lack of objectivity or by intentional bias on the

part of the auditor). While auditor-client familiarity is often touted

as the channel through which long tenure affects auditor independence, several

studies fail to confirm the view. The narrative examined in this study draws

from the theory that auditors start out in client firms with a strong

commitment to their professional mandate but, over an extended tenure, lose

task interest, become less engaged, and resort to checking the boxes. The

independence problem stems from disinterest and disengagement rather than

willful bias.

3. Hypotheses Development

In an earlier study, Bamber and Iyer (2007) rely on

Social Identity Theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1985) to model auditors’ approach to

independence. In their study, auditors’ attachment to clients relative to their

identification with the profession affects auditors’ independence: Auditors who

attach more to their clients are more likely to acquiesce to the clients’

pressure to issue more favorable reports whereas those who are more loyal to

the profession are more likely to resist such pressures. To extend the

analysis, this study proposes that auditors’ responsiveness to their

professional obligations varies over time and influences the inter-temporal

pattern of their independence. The study uses the life cycle paradigm (Hambrick

and Fukutomi, 1991) to generate predictions about the auditor’s independence

across their life cycles in their clients.

3.1. The Auditor Life-Cycle Hypothesis

A strand of literature in organization behavior

posits that, early in their life cycle in a job, groups exhibit excitement

about, and commitment to the task for which they are hired, but later become

wedded to old routines and less responsive to changes in their environments

(e.g., Katz, 1978). During their life cycle on a project, the group strives to

build a stable structure of decision making and, over time, develops routines

and standards of work patterns that are more responsive to the group norms and

customary ways of doing things than to the challenging aspects of their task

(Katz,1982). There is a strong tendency among the group members to adhere to a

stable structure of interlocked behaviors as a strategy to validate one another

and the group’s decisions. In a more formal analysis of the phenomenon among

executives, Hambrick and Fukutomi (1991, 720) observe, “there are discernible

phases, or seasons, within an executive's tenure in a position, and that these

seasons give rise to distinct patterns of executive attention, behavior, and,

ultimately, organizational performance.” They identify five life cycle seasons—response

to mandate, experimentation, selection of an enduring theme, convergence,

and dysfunction—that give rise to distinct patterns of the executives’

behavior. As a context for empirical predictions and

tests in this study, the five seasons are classed into the three life-cycle

phases: Response to mandate (entry phase), experimentation,

selection of enduring theme, and convergence, (adjustment

phase) and dysfunction (recursion phase).

Audit firm as the unit of analysis:

Hambrick and Fukutomi (1991) develop the life-cycle hypotheses based on the

expected behavior of executives during their tenure in a job. The phenomena

depicted in the analysis parallel those that are likely to characterize the

audit firm’s life cycle in a client firm. The key premise, supported by the

life-cycle theory (Katz, 1982; Tushman and Romanelli, 1985; Papadakis and

Bourantas, 1998), is that in a group with a defined task and mandate (e.g., an

audit team), the behavior of the group, through group interactions and social

interplay, will converge to a set practices and patterns, with members’

behavior largely reflecting the group’s accepted norms and decision model. On

this point, Papadakis and Bourantas (1998, 4) argue, “the longer executives

stay with a company the more they will become inculcated with the company's way

of thinking and acting. This management longevity fosters a shared

understanding of issues by managers, a common vocabulary, a reliance on 'tried

and true’ decision practices and the like.” Furthermore, “As with individuals,

groups attempt to increase their control of their work environments through

routinizing and stabilizing workflows, by minimizing their dependence on others

and maximizing others’ dependence on the group, and by socializing recruits to

the group’s norms, values and belief” (Tushman and Romanelli, 1985, 193). For

the audit team, this implies group behavior that reflects the audit firm’s

established procedures and practices, notwithstanding periodic transfers of

members in and out of the group (as alluded to by the European Union). 9Partner rotation as an internal control mechanism is

unlikely to disrupt the audit firm’s established processes or strategies. As

per Tushman and Romanelli (1985), the organization’s (audit firm’s) core values

and strategies are the partner’s frame of reference and serve to align the

patterner’s behavior with the audit firm’s way of doing things). The

discussions below outline the linkages between the various phases of the

auditors’ life-cycle and auditors’ approach to their independence mandate.

3.1.1. Entry (Response to Mandate)

Under the Seasons’ paradigm, entry is

a period during which there is pressure on new hires to show strong commitment

to the mandate for which they are hired. During this period, the individual’s

or group’s primary attention is in developing early track record in the areas

that comprise its going-in mandate (Katz, 1982; Mowday, Porter, and Steers,

1982; Hambrick and Fukutomi, 199). In academic research institutions, for

instance, assistant professors are under pressure to demonstrate research

excellence to justify their hire and get tenure during their early years of

hire. During this period, they put considerable effort into building solid

research records. For a new audit team, the mandate entails emphasis on due

professional care, including strong commitment to independence. (Admittedly,

auditors’ knowledge of a client’s business is limited at the outset. However,

the audit-quality problems caused by auditors’ lack of knowledge are distinct

from those caused by auditors’ lack of independence. The former PCAOB chair, James

Doty (2011), notes that many independence violations flagged by PCAOB are not

due to a lack of technical competence but the failure by the auditor to abide

by the independence rules). The public and PCAOB scrutiny that follows auditor

changes puts further pressures on new audit teams to be mindful of acts that

may erode public confidence in the results of their audits (PCAOB, 2011b). (A

few studies find audit outcomes that align with this view. For example,

using confidential data on partner identity in the banking industry, Gopalan,

Imdieke, Schroeder, and Stuber (2022) find higher loan loss reserves and higher

quality accounting estimates during the early years of audit partners’ tenure,

and notes that partners seem to exhibit high professional skepticism during

their early years of tenure. Carey and Simnett (2006), also, find that the

likelihood of GCO for distressed clients declines with the engagement partner’s

tenure). Also, the required disclosures by both the predecessor and successor

auditors in the event of auditor change (Item 304(a) of Regulation S-K) put

pressure on new engagement teams to be transparent and apply more rigorous

standards of independence during entry. To the extent that new engagement team

responds to these pressures by exercising greater independence, we shall

observe increased auditor-client tensions and more pronounced dispute-related

auditor changes during entry.

3.1.2. Adjustment

In the sense of Hambrick and Fukutomi (1991), the

auditor that survives the entry tournament would relax its commitment to the

“going-in” mandate and undergo a period of “loosening up” (see, also, Gabarro

1987). During this period, the public and regulatory scrutiny of the

auditor-client relation shall have subsided, and the tendency would be for the

auditor to adjust its decision approach based on what was learned during entry.

The premise is that the auditor shall have gained some knowledge of the client’s

business and accounting systems. Importantly, the scrutiny that accompanies

entry-phase audits will have subsided, allowing the audit team to adjust the

stance on independence. Those conditions favor an “easing up” on independence,

perhaps, to lower the effort and costs needed to adhere strictly to the rules.

The conditions further favor a more tailored and predictable structure of

audits that draw from the knowledge and experience gained from prior audits.

This phase, therefore, portends less auditor-client tension and lower level of

auditor independence.

3.1.3. Recursion

During extended tenure, executives’ attention and

task interest drop sharply as “job mastery gives way to boredom; exhilaration

to fatigue; strategizing to habituation” due to repetitive processes (Hambrick

and Fukutomi, 1991, 731). Katz (1978) notes that even the most challenging jobs

eventually become routinized and habitual as the employees become more

proficient and accustomed to their tasks. Given this premise, task approach

during extended tenure will be largely in form of established templates that

are less responsive changes in the environment or task characteristics

(Hambrick and Fukutomi, 1991; Miller and Shamsie, 2001). Old solutions will be

applied to new problems. In the sense of this paradigm, extended auditor tenure

is a prime laboratory for the noted effects of extended tenure on individuals’

attention and effort in the job. In particular, audit processes are largely

recursive. Over an extended tenure, the processes will become overly

repetitive, less challenging, and less exciting for the auditor. As the task

interest fades, audit steps will become boilerplates with preset decision

rules. Conceivably, audits in this phase will be less rigorous, with the

auditor paying less attention to due professional care (e.g., Arrunada and

Paz-Ares, 1997). The independence problem posed by such acts reflects the

auditor’s diminished task interest and complacency not willful bias (e.g.,

Shockley 1981). This further predicts fewer incidents of auditor-client

disputes during recursion.

Hypothesis 1a:

Auditor independence is decreasing in auditors’ life-cycle phases

Hypothesis 1b:

Auditor-client disputes are decreasing in auditors’ life-cycle phases

4. Empirical Design

4.1. Measures of Auditor Independence and Life-Cycle Phases

The SEC Release 33–8400 (SEC, 2004) and several

predecessor releases govern the disclosures pertaining to auditor changes. (See,

Burks and Stevens (2022) for the evolution of the disclosure requirements). The

releases require Form 8-K filing in the event of an auditor change, with

details of the events surrounding the change. Item 304(a)(i) and (ii) of the

mandate requires the client to state whether the auditor resigned, declined to

stand for reappointment, or was dismissed, and whether any audit reports in the

past two years contained unfavorable audit opinions. Item 304(a)(1)(iv) further

requires the disclosures of any auditor-company disagreements on matters of

accounting principles or practices, financial statement disclosures, or

auditing scope or procedure during the two most recent fiscal years preceding

the auditor change; Item 304(a)(1)(v)(A) through (D), requires disclosures of

other events surrounding the auditor change (even if there were no

auditor-client disagreements) within the two most recent fiscal years preceding

the auditor change including any issues raised about audit opinion, accounting

methods, internal controls, management representation, and/or scope-related

matters. Auditor changes under such conditions more clearly reflect the

auditor’s resolve to preserve the integrity of the audit process.

The auditors’ life cycle in client firms is

partitioned into three non-overlapping phases consisting of entry phase

(the first four years of tenure), adjustment phase (the next six

years of tenure, starting in the fifth year) and recursion phase

(tenure over nine years). (The adjustment phase

encompasses the middle three seasons in Hambrick and Fukutomi (1991)--experimentation,

selection of an enduring theme, and convergence--during which the

executives are predicted to reflect on their early strategies, make

adjustments, and settle into a task approach deemed most effective and appropriate.

Applied to audit firms or teams, the adjustment phase entails settling into an enduring

audit routine that would be applied recursively to future audits). These

tenure phases reflect major milestones in the auditor-client relationship

(e.g., SOX 2002; Myers et al. 2003, Davis et al. 2009). Other studies that

adopt similar designs include Stice (1991), Johnson et al. 2002, and Carcello

and Nagy (2004). In the current design, an auditor’s tenure in a client firm

may survive only the first phase, up to the second phase, or through all three

phases.

4.2. The Sample

Auditor changes are obtained from

Audit

Analytics from 1995 to 2022. The sample includes only auditor changes

preceded by one or more reportable events. The sample is divided into three:

Group I comprises 1,158 auditor resignations following reportable events; Group

II has 3,346 auditor dismissals following reportable events; Group III has

1,378 auditor dismissals following GCO and other reportable events. Each group

is then merged with data on Compustat, reducing the sample to 1,135 auditor

resignations, 3,335 auditor dismissals, and 1,373 GCO-related auditor dismissals.

In addition, Group I has 181 auditors that resigned after confirmed

auditor-client disputes; the remaining 954 auditors resigned after at least one

reportable event other than auditor-client disputes. The latter resignations

include cases in which the auditor raised concerns about the client’s

accounting methods but had no disputes prior to resigning. (Auditors may break

from clients that are perceived to be too risky or difficult-to-audit even when

there are no disputes with the client (Bockus and Gigler, 1998; Dunn and

Stewart ,1999; Ghosh and Tang, 2015)). Group II has 378 dismissals after

confirmed auditor-client disputes and 2957 dismissals after one or more

reportable events other than auditor-client disputes. (Notably, auditor

dismissal disclosures are ambiguous about the underlying cause (Burks and

Stephens, 2022). It is difficult to discern from the disclosures whether a

dismissal is an attempt by the client to conceal problems, preempt negative

audit report, or seek a more lenient auditor (e.g., Smith and Nichols, 1982;

DeFond and Jiambalvo, 1993))). Group III has 98 dismissals after confirmed

auditor-client disputes and 1,275 dismissals with at least one reportable event

other than auditor-client disputes.

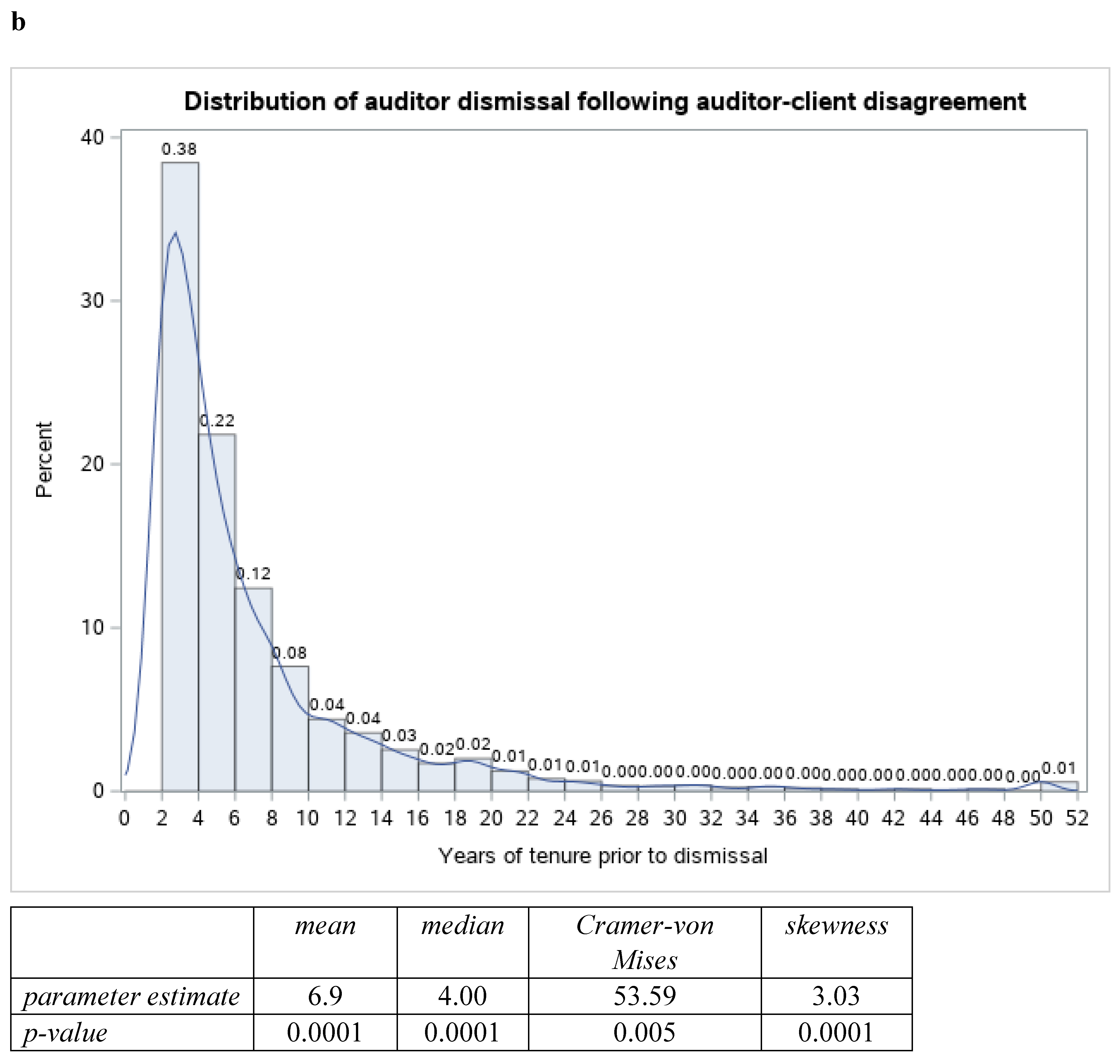

Table 1,

Panel A shows the sampling process.

Panel B shows the frequency of the event-related

auditor changes in each tenure phase. Notably, the bulk of the auditor changes

(3,258 or 56.44 percent out of 5843) occur during the entry phase. In addition,

657 or about 11 percent of the auditor changes are preceded by auditor-client

disputes, with 437 or 66.52 percent of such changes occurring in the entry

phase. Z-tests (at the bottom of the Panel) also show that entry phase

has the highest relative frequency of dispute-related auditor changes. These

results are consistent with Hypothesis 1b that incidents of dispute-related

auditor changes will peak during the entry phase and decline afterwards.

4.3. Empirical Models

4.3.1. Univariate analysis: Temporal pattern of opinion-related auditor changes

Using Item 304(a) disclosures under Regulation S-K, the

time to event,

tenure length, is defined as the number of years of

tenure before the auditor’s exit; next, an event indicator,

auditor-exit,

is assigned an event value of 1 in the last year of the auditor’s tenure. Since

the sample contains only clients for which there is an auditor exit, the event

sample is right-truncated. For the univariate analysis, the probability of observing

the event

(auditor_exit=1) in the interval [

m,

m+τ] after

appointment is

Pr(

m ≤

event ≤

m+τ) = ∫

mm+τ f(t)dt for continuous

time. For discrete time intervals, the expression is approximated by:

4.3.2. Multivariate analysis: Auditor independence and phases of the auditors’ tenure

To test the hypothesis that dispute-related auditor

changes (the proxy for auditor independence) have temporal components aside

from the common factors linked to auditor changes, the study employs the COX

proportional hazard specified in three ways:

ℓj is the log of the ratio, λj(t;(Disagree, Xj))/λ0(t), where λj is the hazard of exit for the jth auditor in a given interval, λ0 is the baseline hazard for auditor-exit = 1. Model (2a) has covariates, Disagree and X, representing a set of known determinants of auditor change; v is the coefficient on Disagree and w is the set of the coefficients on X. Model (2b) adds life-cycle phases, entry and adjustment; entry is coded 1 for tenure interval from one to four years; adjustment is coded 1 for the interval from five to nine years; recursion is the reference phase, representing the interval from 10 years and longer. (If an auditor leaves a client after three years, then entry =1, adjustment =0, and recursion =0. If the auditor leaves at the end of nine years, then entry =1, adjustment =1, and recursion =0. If the auditor stays for 17 years, then entry =1, adjustment =1, and recursion =1). The coefficient, βi (i=1,2), is the effect of the ith phase relative to that of the recursion phase, holding the effects of other covariates constant. Model (2c) includes interactions of Disagree with entry and adjustment; the coefficients, ρ1 and ρ2, capture the time-varying effects of Disagree. The model excludes the main effect of Disagree to facilitate interpretations of ρ1 and ρ2. The models control for auditor- and year-fixed effects.

Covariates: For each auditor change group, Disagree is coded 1 for auditor change preceded by confirmed auditor-client disputes, and 0 for auditor changes with reportable events other than auditor-client disputes. Disagree permits tests of the extent to which the reported auditor-client disputes explain auditor changes. Prior studies also identify other sources of auditor-client tension in the run-up to auditor change. Kluger and Shields (1989), for example, suggest that financial distress is linked to auditor change: Firms in financial distress attempt to conceal the problems via improper accounting methods. When the auditors object, they will likely resign or face dismissal. Dhaliwal, Schatzberg, and Trombley (1993) and DeFond and Jiambalvo (1993) also find that clients that disclose disagreement with their auditors when switching auditors exhibit lower performance and higher leverage. There is also a view that auditors whose clients operate in more litigious environments are less willing to tolerate accounting irregularities. Accounts commonly linked to such frictions include (i) intangible assets, (ii) asset values, (iii) debt and financial health, (iv) revenue and expense accounts.

Intangibles. Intangibles, such as goodwill, are recorded as long-term assets evaluated periodically for impairment. For goodwill, entities are required to perform regular impairment tests to determine whether it is more likely than not that the fair value is less than the carrying value. Tests of possible impairment, however, involve considerable judgment. The accounting standards codification (ASC) 350-20-35-3C, outlies several examples of events and factors that should be considered in performing the test. Notably, clients have incentives to conceal or understate impairments. By contrast, auditors have a mandate to question client’s preferred treatment, especially in matters that require considerable judgment. The likelihood of disputes over impairment estimate is likely to increase with the relative size of the goodwill. The proxy used in analysis, issue-Gdwlt–1, is prior year industry-adjusted ratio of goodwill to total assets, where higher ratio is expected to increase auditor-client tension.

Asset value. Asset valuation is also seen as another frequent source of auditor-client disputes. Clients have vintages of assets that require varied valuation methods. Incentives and opportunities exist for clients to use accounting methods that embellish asset values. However, as part of their professional mandate, auditors will be reluctant to sign off on asset values perceived to materially exceed the expected economic benefits. A measure popularly used to identify such overvaluation is the ratio of book-to-market value of assets. The ratio captures the disparity between the recorded values and market’s expectation of the assets’ future economic benefits. Higher ratios are an indication of overvalued assets, and conversely. The indicator, issue-Asset-value t – 1, is set to 1 for clients in the top quintile of clients in the same four-digit SIC code ranked by prior year industry-adjusted ratio of book to market value of assets, and 0 otherwise.

Debt and financial health. Clients with high debt have been shown to engage in aggressive accounting practices to lower concerns about their going-concern status. Such firms are likely to face greater scrutiny about their ability to meet their debt obligations. The proxy for the potential auditor-client tension related to debt, issue-Debtt–1, is prior year industry-adjusted ratio of total debt to total asset. In addition, firms in distress may take questionable accounting actions to shore-up stakeholders’ confidence. However, such firms will face greater scrutiny by the risk-averse auditors to reduce the risk of issuing a clean report to a client that deserves GCO. The proxy for financial distress is the Altman’s Z-score, Altman-Zt–1. In addition, clients with losses have incentives to take aggressive accounting actions to allay investor and creditors’ concerns. However, loss incidents will raise auditors’ concern about the client’s ability to survive. The auditor-client issue related to losses, issue-Losst–1, is an indicator set to 1 if prior-year net income is negative, and 0 otherwise.

Income statement. Income statement issues in auditor-client disputes often pertain to revenue and expense recognition methods, adequacy of provisions for possible losses, possible disclosure issues. More generally, the issues pertain to the auditors’ concerns that the client’s preferred methods overstate income or understate expenses. The auditor may allege premature revenue recognition, inadequate allowance for sales returns or warranty claims, under-provision for uncollectible accounts, understated expenses, etc. In essence, the tensions arising from one or more such issues reflect concerns about the relative level of accruals in the income statement. For ease, the ratio of accruals to total assets immediately preceding the reportable event year is used to capture the potential tension arising from such issues. In particular, issue-Tact–1 is defined as prior year industry-adjusted ratio of total accruals to total assets, where higher ratio is expected to increase auditor-client tension. (Total accruals ratio avoids measurement and estimation issues associated with other accrual models).

Additional client-specific controls include profitability, size, age, illiquidity, big auditor, and litigation exposure. Auditors may view more profitable clients to be less risky and less prone to GAAP violations. To control for the possible effect on audit decisions, the model includes

roat–1, defined as prior-year industry-adjusted ratio of operating profits to total assets. Client size may also affect audit decisions. Smaller clients have greater staffing and control problems that could lead to GAAP violations and disagreements with auditors. The indicator,

Small-client, is set to 1 if the client is in the bottom quintile of the clients ranked by total assets. Client age is another factor that may affect auditor-client relation. Older (younger) clients are more (less) experienced in resolving disputes with auditors. Client age,

Client-age, is the natural log of the number of years the client is listed on Compustat. The model also includes the indicator,

Ilquidityt–1, set to 1 for clients in the bottom quintile of clients in the same four-digit SIC code ranked by prior year industry-adjusted ratio of current asset to current liabilities, and 0 otherwise. The indicator captures the concerns that auditors may have about the client’s ability to meet its financial obligations.

Big8, is an indicator set to 1 if the auditor is one of the largest eight auditors based on total revenues, and 0 otherwise. Big auditors have resources to vet and select clients that are less risky. Next an indicator of litigation exposure,

Lit-climate, is set to 1 for clients that operate in highly litigious industries to control for the effects of litigation incentive on audit decisions. The test models are (firm and time subscripts are suppressed for clarity):

The event type modelled by ℓj is alternately dispute-related auditor resignation, dispute-related auditor dismissal, and auditor dismissal preceded by GCO and one or more reportable events. Detailed definitions of the variables are in the Appendix.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

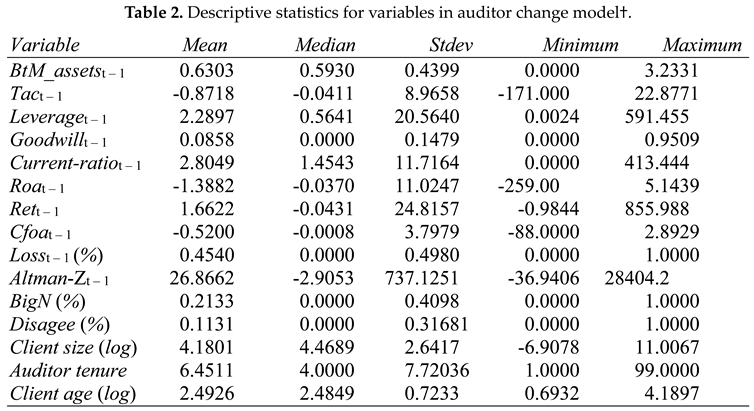

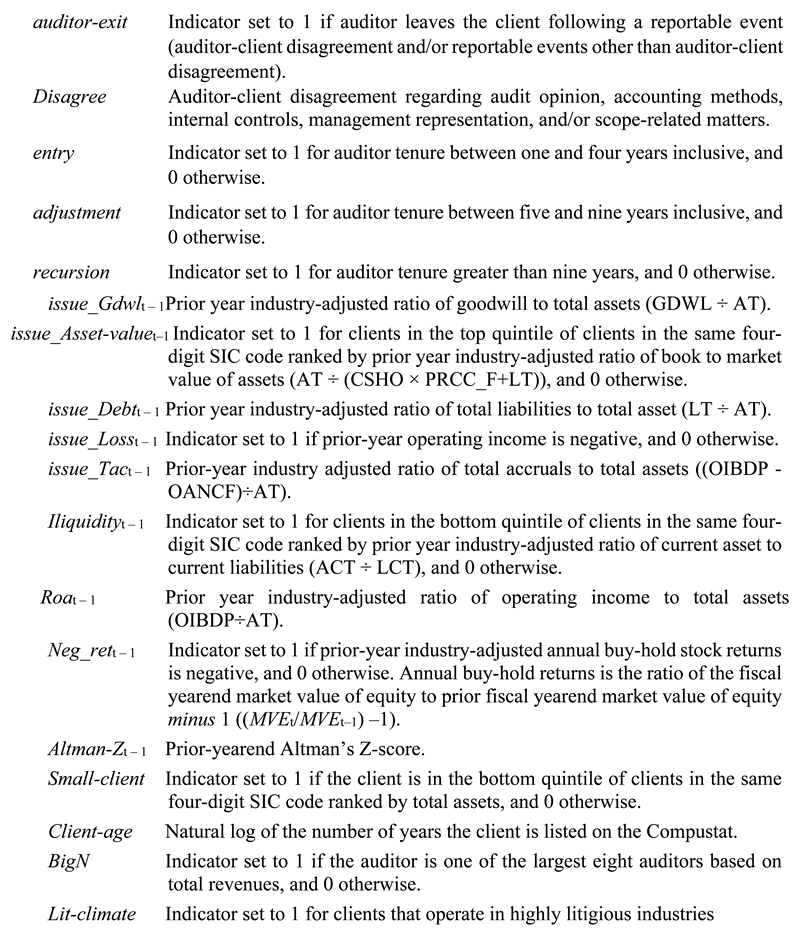

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the variables. In the Panel, the mean

BtMt–1 is 0.6303, which indicates that the market values of assets average just about 1.59 percent of their stated values. The medians of

Roat–1 and

Cfoat–1 are also negative, indicating that many clients experienced poor operating results in the lead up to the auditor change. There are also high incidents of operating losses (approximately 46 percent of the observations). Notably, the median tenure is only four years. In other words, tenure for the bottom half of the auditors in the sample lasted for four or fewer years. Reflecting the sampling information in Panel B of

Table 1, open auditor-client disagreements occurred in about 11 percent of the auditor changes.

The subpanel for the GCO sample shows high stock issue relative to debt issue, possibly reflecting increased borrowing constraints as the clients’ financial conditions deteriorate. About 58 percent of the GCO audits are performed by Big N audit firms, consistent with the view that BigN audit firms, in general, exhibit greater propensity to issue GCO. The clients’ profit performance is markedly negative for the GCO years. The mean (median) Roat is -0.41 (-0.14) for the GCO years. The means and medians of both annual stock returns (Rett-1) and cash flow (Cfoat-1) are also negative for the GCO years.

5.2. The Temporal Pattern of Dispute-related Auditor Changes

The temporal pattern of auditor independence is examined by plotting the probability of observing auditor exit

(auditor_exit=1) in the interval [

m,

m+τ] during the auditor’s tenure.

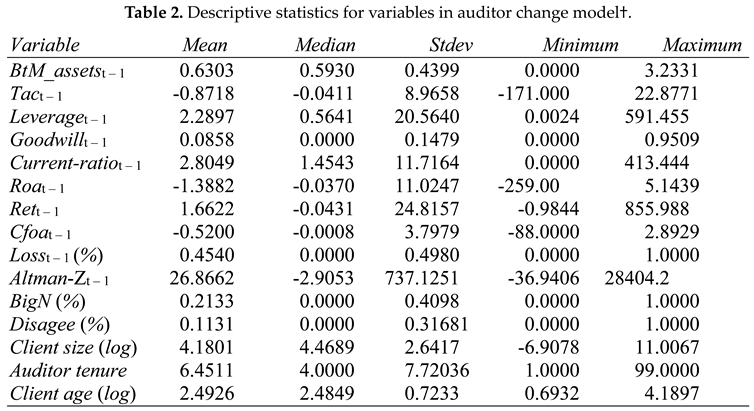

Figure 1 shows the results.

Figure 1a shows the distribution of dispute-related auditor resignations. Notably, 41 percent of the resignations occur in the first four years of tenure; by the end of sixth year, 65 percent of such resignations has occurred; by the end of 10

th year, 85 percent of such resignations has occurred. Beyond the 14

th year, there are no discernible resignations following auditor-client disputes. The skewness statistic is 2.91 (Z

skewness = 40.08,

p < 0.0001) and the Cramer-von Mises statistic,

W-sq, is 17.43 (

p > 0.005), indicating that the distribution is not normal. To the degree that auditor resignation following auditor-client disputes are a credible indicator of auditors’ independence, the results suggest that auditors exhibit greater independence during the early years of their tenure and also resign more frequently during the phase, consistent with hypotheses 1a and 1b.

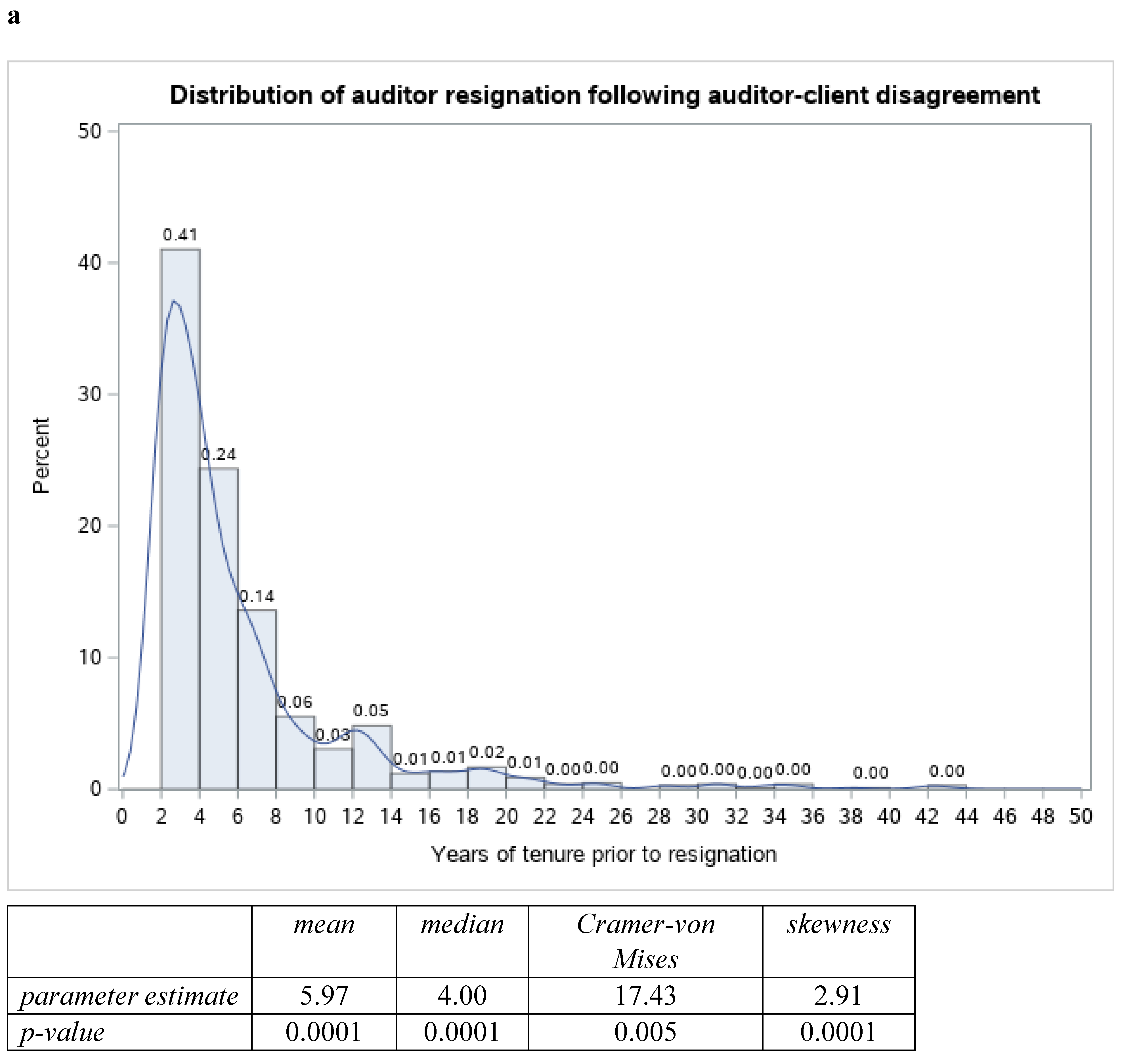

Figure 1b shows the distribution of auditor dismissals following disputes with clients. In the figure, 38 percent of the dismissals occur in the first four years of tenure; by the end of six years, 60 percent of such dismissals has occurred; and by the end of 10 years, 80 percent of such dismissals has occurred. The skewness statistic is 3.03 (Z

skewness = 67.76,

p < 0.0001) and the Cramer-von Mises statistic,

W-sq, is 53.59 (

p > 0.005), which rejects the hypothesis that the dismissals are normally distributed. The results again suggest that auditors exhibit greater independence during the early years of their tenure auditors exhibit greater independence during the early years of their tenure and are also dismissed more frequently during the phase, consistent with hypotheses 1a and 1b.

Figure 1c focuses on auditor dismissal following the issuance of GCO. Such a dismissal decision is a strong signal of the auditor’s resolve to withstand client’s pressure for a more favorable audit decision. In the figure, the dismissal pattern following the issuance of GCO is similar to the pattern in

Figure 1b. For instance, 48 percent of the GCO-related dismissals occur in the first four years of tenure; by the end of six years, 73 percent of such dismissals has occurred; and by the end of 10 years, 91 percent of such dismissals has occurred. The skewness statistic is 4.15 (Z

skewness = 59.95,

p < 0.0001) and the Cramer-von Mises statistic,

W-sq, is 23.04 (

p > 0.005). Again, both statistics reject the hypothesis that such dismissals are normally distributed and indicate that auditors exercise greater independence during their entry years and are dismissed more frequently for issuing GCO during the period, consistent with H1a and H1b.

5.3. Supporting Evidence:

As supporting evidence, the probability of observing a first-time GCO event

(gco=1) in the interval [

m,

m+τ] during the auditor’s tenure years. The plot is based on 3,232 observations of first-time GCO from 1995 to 2020. The result is presented in

Figure 2

The first-time GCOs are clustered around the early years of the auditors’ tenure, with 64 percent of the opinions issued in the first three years and 75 percent of the opinions issued by the end of the fifth year; 88 percent of the opinions has been issued by the end of the ninth year. The distribution is highly skewed, with has a skewness statistic of 3.00 (Zskewness = 50.63, p < 0.0001). The Cramer-von Mises statistic for the test of normality, W-sq, is 41.60 and significant (p > 0.005), which indicates non-normal distribution for the first-time GCOs. The results again suggest that auditors exercise greater independence during their early tenure years.

5.4. Multivariate Analysis:

5.4.1. Auditor resignation following disputes with clients

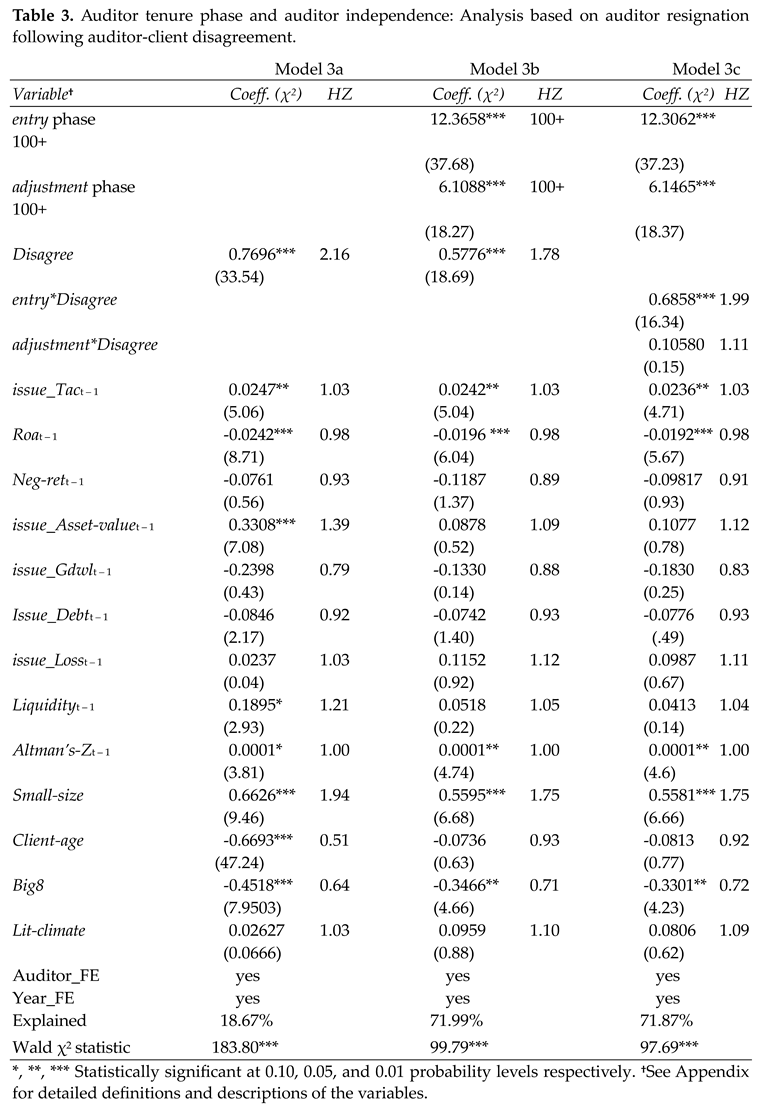

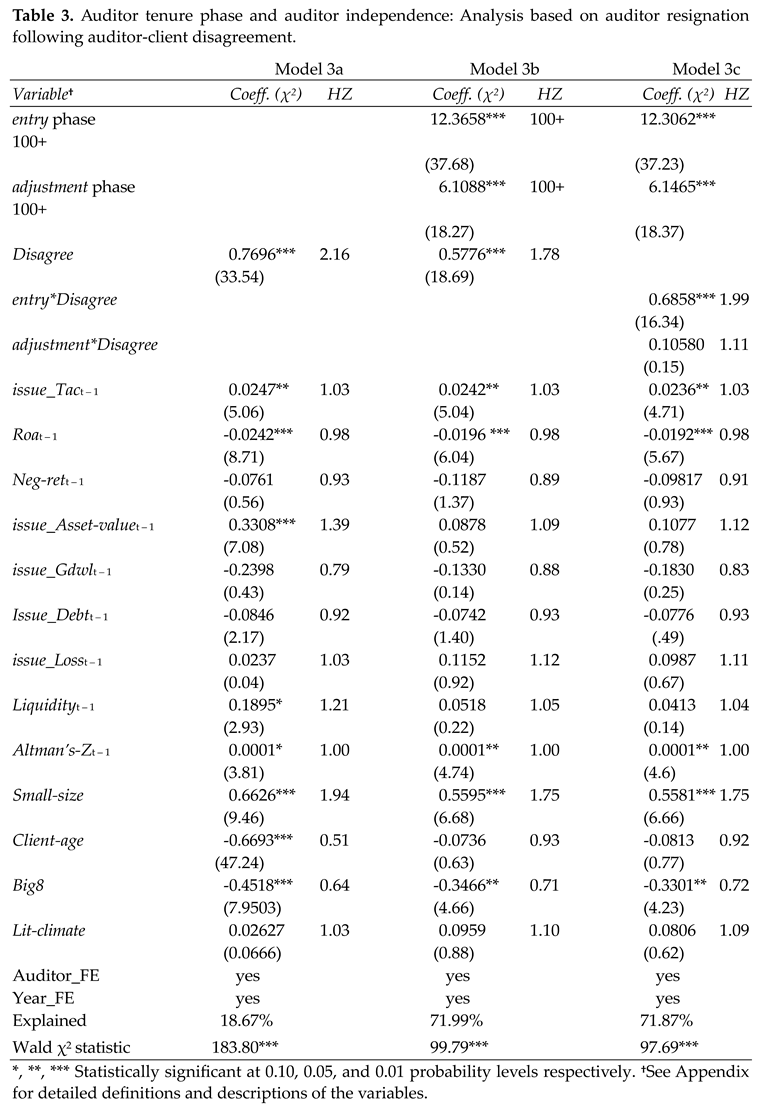

Table 3 presents the results of estimating the proportional hazard model using dispute-related auditor resignation as the event of interest.

Column 1 shows the base mode results. Notably, Disagree has the most significant impact on the hazard model (coeff. = 0.7696, p < 0.01). The hazard ratio is 2.16 indicating that the hazard of auditor resignation is 2.16X higher when there is auditor-client disagreement. The results for other covariates generally corroborate the findings in prior studies. For example, large accruals to asset ratio, overstated assets, poor financial health, illiquidity, and small firms have positive impacts on the hazard that the auditor will resign, whereas return on assets, firm age, and Big8 auditors are associated with lower hazards of auditor resignation. The model explains 18.67% variation in auditors’ resignation. (Some argue that auditor tenure is endogenous to the clients’ contracting process in that firms with greater accounting quality problems will have more auditor-client disputes, receive unfavorable opinions more often, and replace their auditors more frequently (e.g., DeFond and Zhang, 2014; Lennox et al., 2014). Such a dynamic in auditor-client disputes and auditor turnover, in effect, portrays auditors as exercising more independence by opting to withstand the pressures by such clients, despite the associated costs to the auditor).

In column 3, the coefficients on entry and adjustment are positive and highly significant. In other words, the hazard of dispute-related auditor turnover is much higher during those two life-cycle phases compared to that during the recursion phase. Notably, the entry-phase effect is more than double that of the adjustment phase, indicating that entry phase poses the greatest hazard of dispute-related auditor resignation. The results also corroborate the temporal pattern of dispute-related auditor resignations in figure 1a which shows a concentration of resignations during the entry phase. The coefficient on Disagree is also positive and significant, indicating that a reliable component of the auditors’ resignations is linked to auditor-client disputes. The explained variation of 72 percent is about four times that of the base model of 18.67 percent. In other words, life-cycle phases have a considerable impact on dispute-related auditor resignations.

Column 5 examines whether the effect of Disagree on auditor resignation has a phase-dependent component. The test focuses on the coefficients on interactions of Disagree with entry and adjustment. In the column, the effects of entry and adjustment remain reliably positive. The coefficient on Disagree*entry is positive and highly significant, but that on Disagree*adjustment is insignificant. Auditors, thus, seem more apt to resign following disputes with their clients during their entry period compared to subsequent periods. The explained variation is about four times that of the base model. These results strongly suggest that the hazard of auditor resignation following auditor-client dispute or reportable events is most pronounced in the early years of auditors’ tenure. If auditors’ resignation following auditor-client disputes or issuance of unfavorable opinions are signals of auditor independence, then the results provide strong support for the view that auditors exercise greater independence at the outset of their tenure.

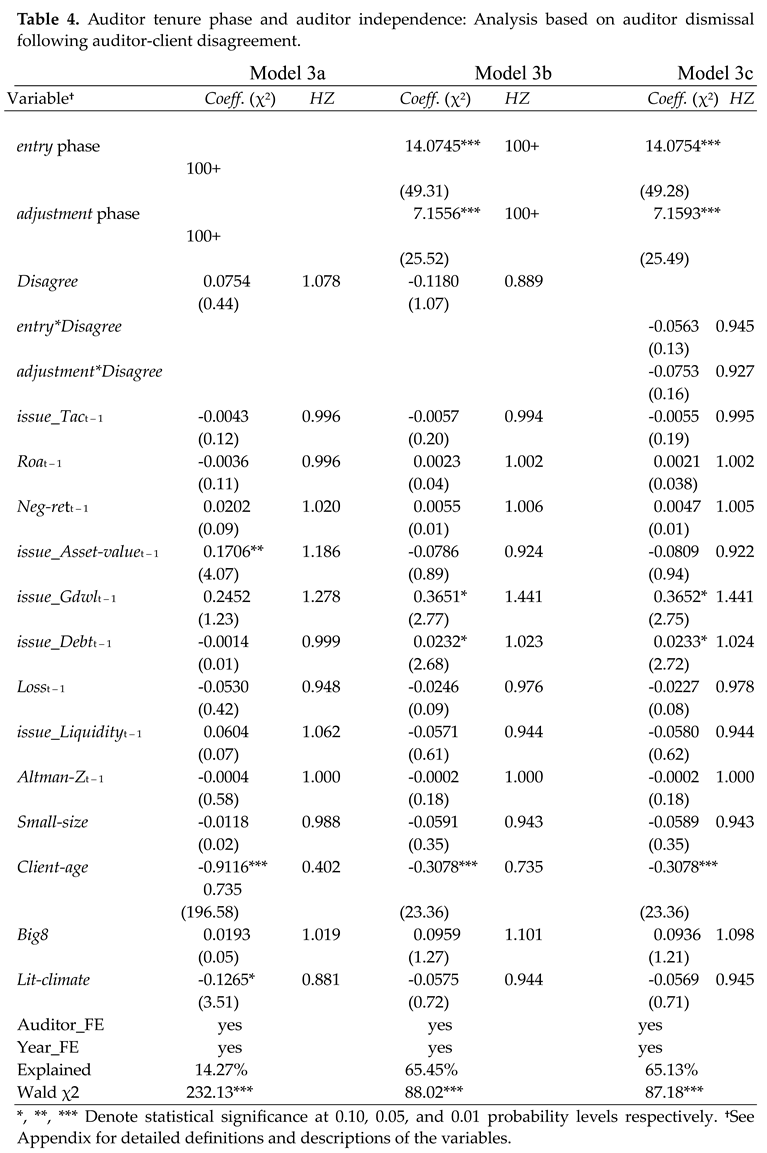

5.4.2. Auditor dismissal following disputes with clients

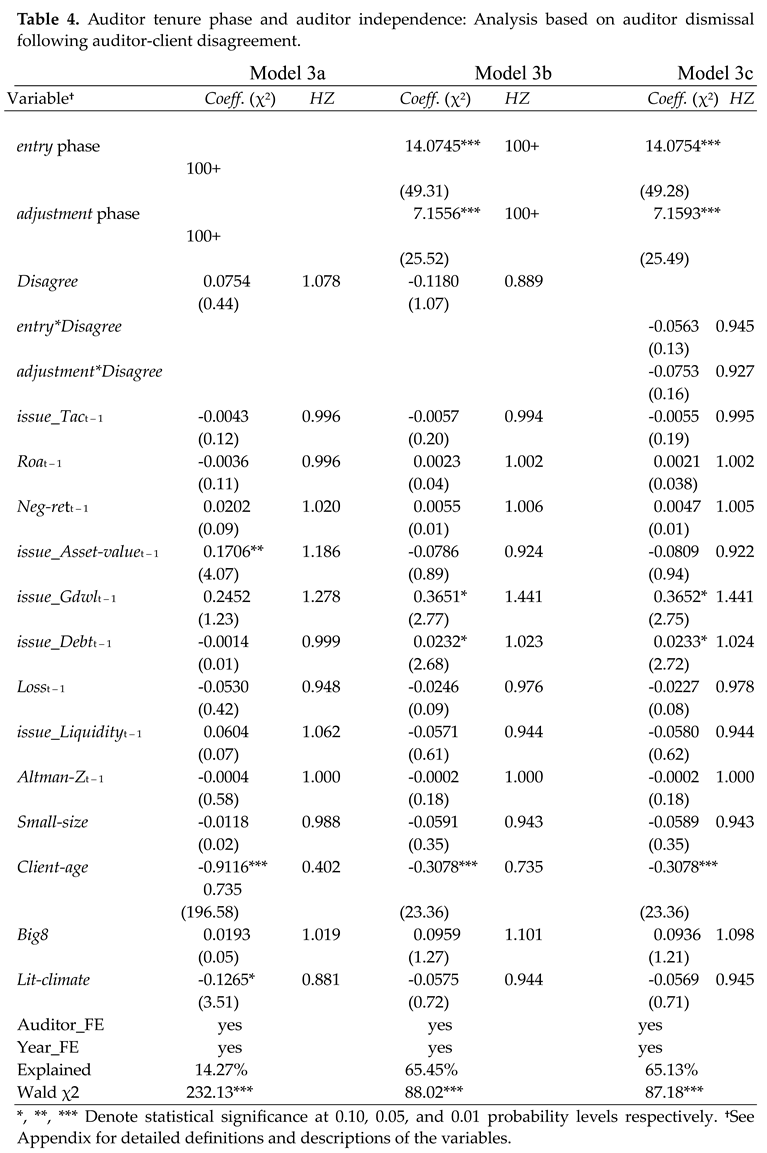

Table 4 presents the results for dispute-related auditor dismissals. Notably,

Disagree has insignificant effect on the hazard function in all in columns. Also, the bulk of the variables commonly linked to auditor-client disputes (e.g., accruals, profits, losses, debt, and financial health) has little effects on the hazard model. (In a separate test, one-year ahead accruals, loss indicator, return on assets, negative security returns, and debt-overhang are included in the model on the possibility that clients anticipating poor performance and/or going-concern problems replace the incumbent to create an opportunity to select more favorable accounting methods. The results (omitted for brevity) show that future performance and accounting variables do not explain the dismissals). The results support Burks and Stevens’ (2022) view that the dismissal disclosures provide little information about the underlying circumstances (see, also, Griffin and Lont 2010).

In column 3, the coefficients on entry and adjustment are positive and significant. The results, again, indicate that the hazard of auditor dismissal following GCO is higher during the two phases compared to that during recursion. Notably, the entry phase effect is more than double that of the adjustment phase, indicating that entry phase poses the highest hazard of auditor dismissal, holding constant the effects of other covariates. The results corroborate the temporal pattern of dispute-related auditor dismissal in figure 1b. The effect of Disagree is, again, insignificant. The explained variation of 72% is about four times that of the base model of 18.67%, which again suggests that the effects of the life-cycle phases are considerable.

In column 5, the main effects of entry and adjustment remain as shown in column 3. In other words, in the absence of the other covariates, the entry and adjustment phases have more impact on dispute-related auditor dismissal than the recursion phase. The coefficients on Disagree*entry and Disagree*adjustment are insignificant. The explained variation remains about four times that of the base model. The results, again, provide support for the view that auditors exercise greater independence (i.e., resist clients’ pressures for more favorable audit decisions) at the outset of their tenure, consistent with H1a.

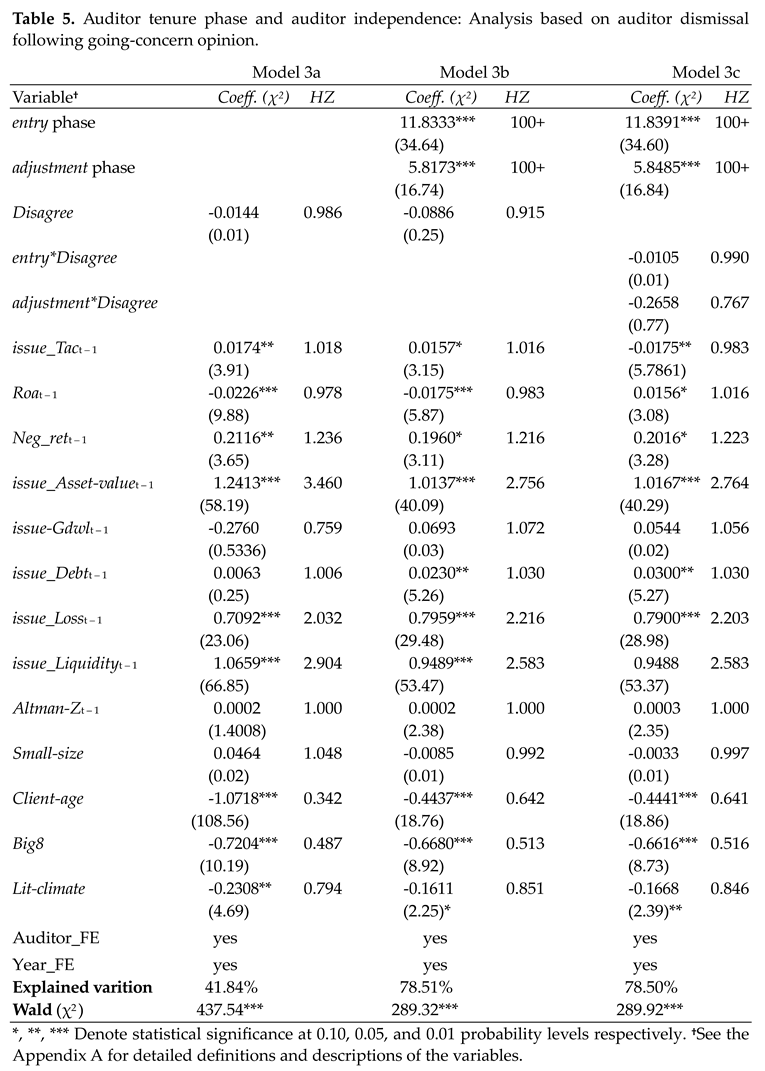

5.4.3. GCO-Related Auditor Dismissal Following Disputes with Clients

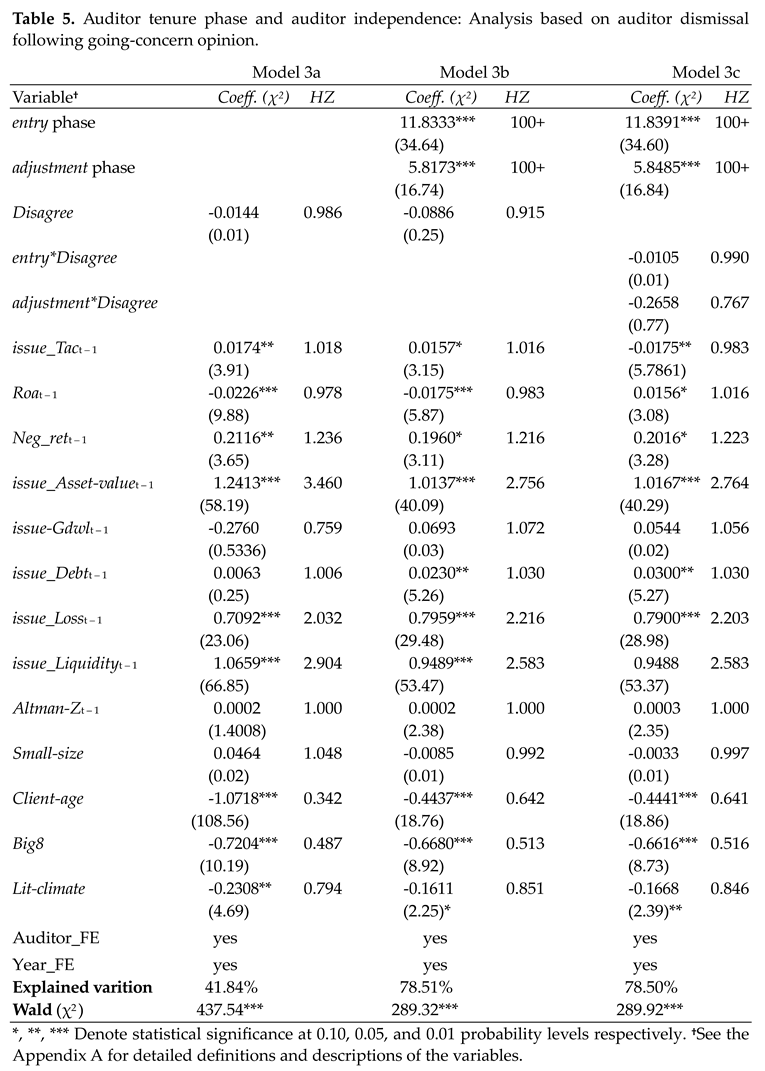

Table 5 presents results for GCO-related auditor dismissal. For the base model (column 1),

Disagree has no discernible effects on the hazard model. The most significant effects are due to poor financial performance, similar to the findings in prior studies. For example, large accruals, negative stock returns, overvalued assets, loss, and illiquidity in the year preceding the GCO event have positive and significant effects on the hazard model. Notably, the hazard rate for clients that operate in more litigious industries are lower relative to those in other industries. In perspective, increased exposure to litigation may reduce the client’s incentive to dismiss the auditor for fear of increased scrutiny.

In column 3, the effects of entry and adjustment phases are, again, positive and significant. Their hazard ratios show that auditors face higher hazard of dismissal following GCO during entry and adjustment compared to the risk of such dismissal during recursion. The entry phase effect is, again, more than double that of the adjustment phase, further validating the declining trend in the hazard of GCO-related auditor dismissal over the life-cycle. The explained variation of 78.51% is about twice that of the base model of 41.81%, which support the notion that auditors exercise more independence during entry years, in line with hypothesis 1a.

The results in columns 5 focus not only on the effects of entry and adjustment, but also on the effects of their interactions with Disagree. In the column, the effects of entry and adjustment remain positive and significant. Notably, the effect of entry is, again, double that of adjustment, corroborating the notion that auditors face the highest hazard of GCO-related dismissal during the entry period. As in Table 4, the coefficients on the interactions of Disagree with entry and with adjustment are insignificant. That is, the effects of entry and adjustment on the hazard function are unaffected by auditor-client dispute.

5.4.4. Further Test the Pattern of Auditor Independence Based on First-Time GCO

GCO has been used as proxy for auditor independence (e.g., DeFond and Zhang, 2014). As a further test of the mandate perspective, a logit model of first-time GCO is fitted on the the life-cycle phases and a variety of other factors linked to going-concern decisions. The results (omitted for brevity) show that the odds of receiving first-time GCO is highest during the entry phase of the auditors’ tenure after controlling for a variety of factors previously shown to affect the issuance of GCO. To the extent that GCO credibly conveys auditor independence, the results suggest that auditors are more independent during the entry phase compared to their later life-cycle phases, in line with the predicted pattern under the Tenure Seasons hypothesis.

6. Conclusion

This study tests that auditor independence is linked to the phase of the auditors’ tenure. Using auditor changes following auditor-client disputes as surrogates of auditor independence, this study provides strong evidence that auditors exercise greater independence during the early years of their tenure. The study further shows a stronger impact of accounting quality problems on the likelihood of dispute-related auditor changes during the early years of the auditors’ tenure. These results are not sensitive to the presence of conventional factors previously shown to affect auditor changes. Collectively, the findings strongly suggest that auditors exercise more independence in the early stages of their tenure. Policy-wise, the findings highlight that auditor tenure phase is a factor that may be considered in the effort to address the auditor independence problem as it relates to audit firm tenure.

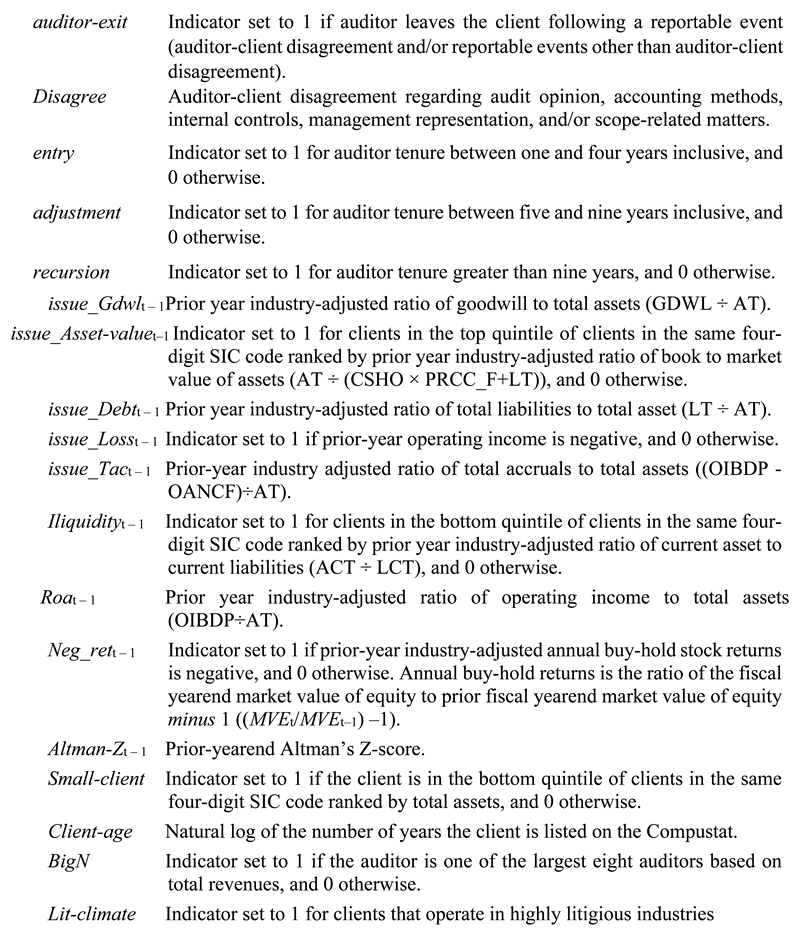

Appendix A Variables definition (WRDS mnemonics for variables are in parenthesis)

Data Sources:

Data Sources: All data used in analyses are publicly available from sources identified in the text.

References

- Arrunada, B.; Paz-Ares, C. Mandatory rotation of company auditors: A critical examination. International review of law and economics 1997, 17, 31–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamber, E.M.; Iyer, V.M. Auditors’ identification with their clients and its effect on auditors’ objectivity. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 2007, 26, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, M. 2013. Update on PCAOB auditing standard setting. AICPA National Conference on SEC and PCAOB Developments, Washington, DC.

- Bazerman, M.H.; Morgan, K.P.; Loewenstein, G.F. Auditing: The impossibility of auditor independence. Sloan Management Review 1997, 38, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, T.B. , Carcello, J.V. A decision aid for assessing the likelihood of fraudulent financial reporting. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 2000, 19, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockus, K.; Gigler, F. A theory of auditor resignation. Journal of Accounting Research 1998, 36, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burks, J.J.; Stevens, J.S. Opaque auditor dismissal disclosures: What does timing reveal that disclosures do not? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 2022, 41, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcello, J.V.; Nagy, A.L. Audit firm tenure and fraudulent financial reporting. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 2004, 23, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, P.; Simnett, R. Audit partner tenure and audit quality. The Accounting Review 2006, 81, 653–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassell, C.A. , Myers, J. Available at SSRN 244 8680.

- Chen, C.Y.; Lin, C.J.; Lin, Y.C. Audit partner tenure, audit firm tenure, and discretionary accruals: Does long auditor tenure impair earnings quality? Contemporary accounting research 2008, 25, 415–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelo, L. Auditor independence, "low-balling," and disclosure regulation, Journal of Accounting and Economics (August) 198l, 113-127.

- DeFond, M.L.; Jiambalvo, J. Factors related to auditor-client disagreements over income increasing accounting methods. Contemporary Accounting Research 1993, 9, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFond, M.; Zhang, J. A review of archival auditing research. Journal of Accounting and Economics 2014, 40, 1247–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D.; Schatzberg, J.; Trombley, M. An analysis of the economic factors related to auditor-client disagreements preceding auditor changes. Auditing 1993, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Doty, J.R. 2011. Keynote address: The global dimension conference on audit policy. FEE Conference on Audit Policy, Brussels. At https://pcaobus.org/news-events/speeches/speech-detail/keynote-address-the-global-dimension-conference-on-audit-policy_325.

- Dunn, J.; Stewart, M. Resignation or abdication—the credibility of auditor resignation statements. Accounting Forum 1999, 23, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R.T.; Lundstrom, N.J.; Wilkins, M.S. The impact of mandatory auditor tenure on disclosures on ratification voting, auditor dismissal, and audit pricing. Contemporary Accounting Research 2021, 38, 2871–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union, 2014. Regulation (EU) No 537/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of on specific requirements regarding statutory audit of public-interest entities and repealing Commission Decision 2005/909/EC Text with EEA relevance (OJ L 158 27.05.2014, p. 77, CELEX: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/? 16 April 3201.

- Gabarro, J. J. 1987.

- Ghosh, A.; Moon, D. Auditor tenure and perceptions of audit quality. The Accounting Review 2005, 80, 585–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Tang, C.Y. Auditor resignation and risk factors. Accounting Horizons 2015, 29, 529–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, M.A.; Raghunandan, K. Auditor tenure and audit reporting failures. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 2002, 21, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gipper, B. , Hail, L., Leuz, C. On the economics of mandatory audit partner rotation and tenure: Evidence from PCAOB data. The Accounting Review 2021, 96, 303–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, Y.K. , Imdieke, A.J., Schroeder, J.H., Stuber, S.B. 2022. Audit partner tenure and accounting estimates. Working paper, University of Notre Dame.

- Griffin, P.A.; Lont, D.H. Do investors care about auditor dismissals and resignations? What drives the response? Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 2010, 29, 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Fukutomi, G.D. The seasons of a CEO's tenure. Academy of Management Review 1991, 16, 719–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, D.S.; Velury, U. Does auditor tenure influence the reporting of conservative earnings? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 2008, 27, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, V.E. , Khurana, I.K., Reynolds, J.K. Audit-firm tenure and the quality of financial reports. Contemporary Accounting Research 2002, 19, 637–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, R. Job longevity as a situational factor in job satisfaction. Administrative Science Quarterly 1978, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, R. The effects of group longevity on project communication and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly 1982, 27, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, J. , Krishnan, J. 1997. Litigation risk and auditor resignations. The Accounting Review.

- Kluger, B.D.; Shields, D. Auditor changes, information quality, and bankruptcy prediction. Managerial and Decision Economics 1989, 10, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurion, H. , Lawrence, A., Ryan, J.P. U.S. audit partner rotations. The Accounting Review 2017, 92, 209–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennox, C.; Wu, X.; Zhang, T. Does mandatory rotation of audit partners improve audit quality? The Accounting Review 2014, 89, 1775–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litt, B.; Sharma, D.S.; Simpson, T.; Tanyi, P.N. Audit partner rotation and financial reporting quality. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 2014, 33, 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Loebbecke, J.K.; Eining, M.M.; Willingham, J.J. Auditors experience with material irregularities-frequency, nature, and detectability. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 1989, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Manry, D.L. , Mock, T.J., Turner, J.L. Does increased audit partner tenure reduce audit quality? Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance 2008, 23, 553–572. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.; Shamsie, J. Learning across the life cycle: Experimentation and performance among the Hollywood Studio heads. Strategic Management Journal 2001, 22, 725–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, T.; O’Quigley, J.; Mesbah, J. A global goodness of-fit statistic for the proportional hazards model. Applied Statistics 1985, 34, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T. , Porter, L.W., Steers, R.M. 1982. Employee organizational linkages: The psychology of commitment, absenteeism, and turnover.

- Myers, J.N.; Myers, L.A.; Omer, T.C. Exploring the term of the auditor-client relationship and the quality of earnings: A case for mandatory auditor rotation? The Accounting Review 2003, 78, 779–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, V.; Bourantas, D. The chief executive officer as corporate champion of technological innovation: An empirical investigation. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 1998, 10, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, C. 2018. Auditors in crosshairs. Cooley PubCo (). Available at: https://cooleypubco. 11 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- PCAOB. 2011a. <i>Concept release on auditor independence and audit firm rotation</i>. PCAOB release No. 2011-006. Washington, D.C. PCAOB. 2011a. Concept release on auditor independence and audit firm rotation, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- PCAOB. 2011b. <i>Concept release on auditor independence and audit firm rotation: Notice of roundtable</i>. PCAOB release No. 2011-006. Washington, D.C. PCAOB. 2011b. Concept release on auditor independence and audit firm rotation: Notice of roundtable, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- PCAOB, 2017. AS 3101. The auditor’s report on an audit of financial statements when the auditor expresses an unqualified opinion, 2017.

- Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). 2004. Additional Form 8-K disclosure requirements and acceleration of filing date. Release no. 33-8400. Washington, D.C. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). 2004. Additional Form 8-K disclosure requirements and acceleration of filing date. Release no. 33-8400. Washington, D.C.: SEC.

- Shockley, R.A. Perceptions of auditors' independence: An empirical analysis. The Accounting Review 1981, 56, 785–800. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.B.; Nichols, D.R. A market test to investor reaction to disagreements. Journal of Accounting and Economics 1982, 4, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, Z.; Zhang, J. Auditor tenure and the timeliness of misstatement discovery. The Accounting Review 2018, 93, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, J.E.; Grove, H.D.; Selto, F.H. Detecting management fraud: An empirical approach. In Symposium on Auditing Research 1983, 5, 73–116. [Google Scholar]

- Sriram, S. 1987. An investigation of asymmetrical power relationships existing in auditor-client relationship during auditor changes. Unpublished dissertation, University of North Texas, http://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc331678/.

- Stanley, J.D.; DeZoort, F.T. Audit firm tenure and financial restatements: An analysis of industry specialization and fee effects. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 2007, 26, 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. , Turner, J.C. 1985. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Psychology on Intergroup Relations, edited by S. Worchel and W. G. Austin, 7–24. 2nd edition. Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall.

- Tushman, M.L.; Romanelli, E. Organizational evolution: A metamorphosis model of convergence and reorientation. Research in Organizational Behavior 1985, 7, 171–222. [Google Scholar]

Table 1.

Panel A: Auditor-change sample selection.

Table 1.

Panel A: Auditor-change sample selection.

| |

Resigned |

Dismissed |

GCO-dismissed |

| Initial sample of auditor changes (from 2001 to 2020) |

8,804 |

4,158 |

10,329 |

| Retain auditor changes following reportable events |

1,158 |

3,346 |

1,378 |

| Drop clients with missing financial data on Compustat |

(23) |

(11) |

(5) |

| Sample of auditor changes with reportable events |

1,135 |

3,335 |

1,373 |

| Subset with auditor-client disagreements |

181 |

378 |

98 |

| Subset with reportable events other than disagreements |

954 |

2,957 |

1,275 |

| Panel B: Distribution of auditor changes across tenure phases |

| Tenure phase |

entry |

adjustment |

recursion |

Total |

| All auditor changes with reportable events |

N1 = 3,298 |

N2 = 1,514 |

N3 = 1,031 |

NT = 5843 |

| Subset of auditor changes with client disputes |

n1 = 437 |

n2 = 150 |

n3 = 70 |

nT = 657 |

| Column relative frequency (ρi = ni/Ni) |

ρ1 = 13.25% |

ρ2 = 9.92% |

ρ3 = 6.79% |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Data Sources: All data used in analyses are publicly available from sources identified in the text.

Data Sources: All data used in analyses are publicly available from sources identified in the text.