Submitted:

06 December 2024

Posted:

09 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie Y, Al-Aly Z. Risks and burdens of incident diabetes in long COVID: a cohort study. Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinol. 2022;10(5):311-321. [CrossRef]

- Wander PL, Lowy E, Beste LA, et al. The Incidence of Diabetes Among 2,777,768 Veterans With and Without Recent SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(4):782-788.

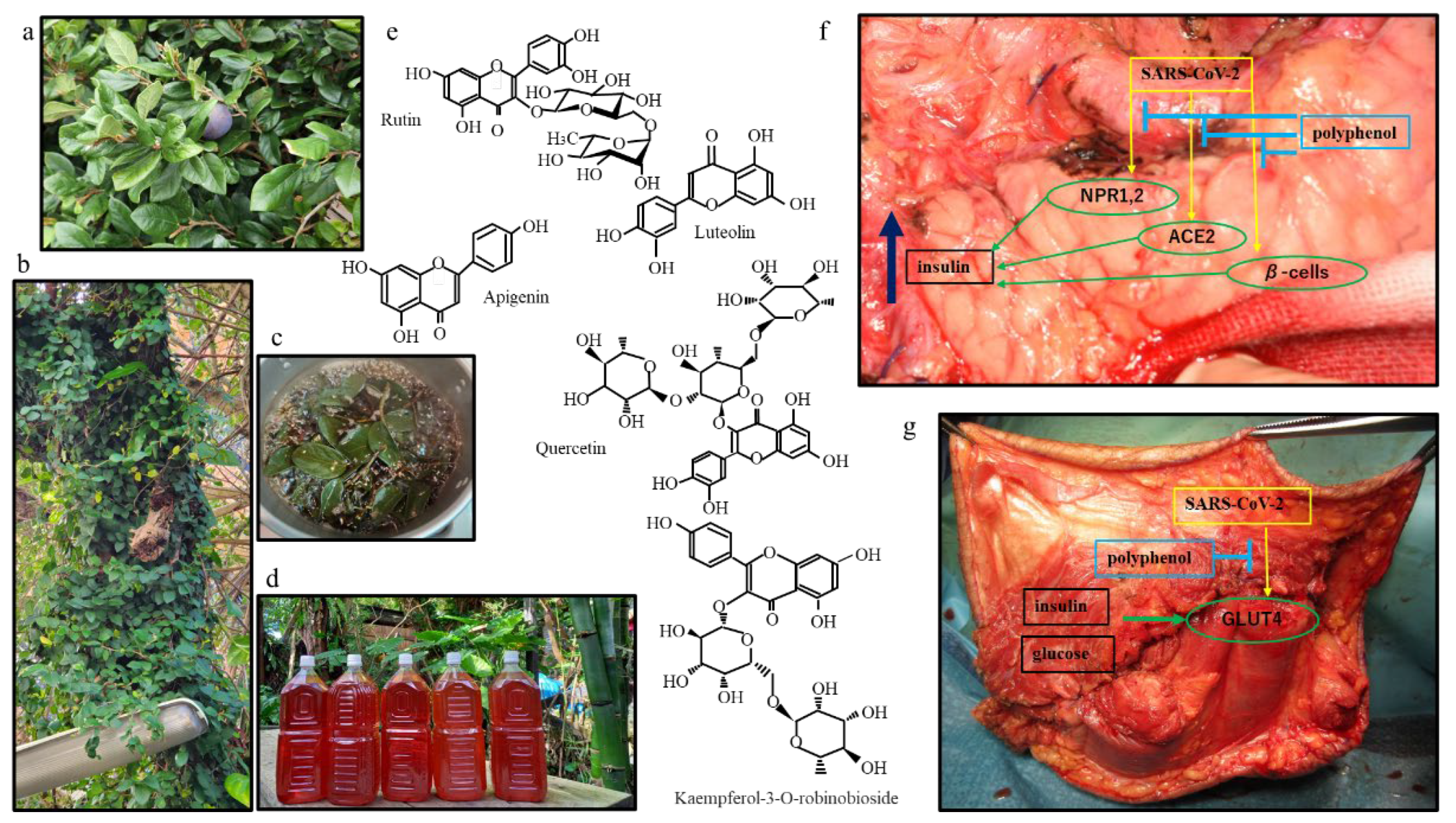

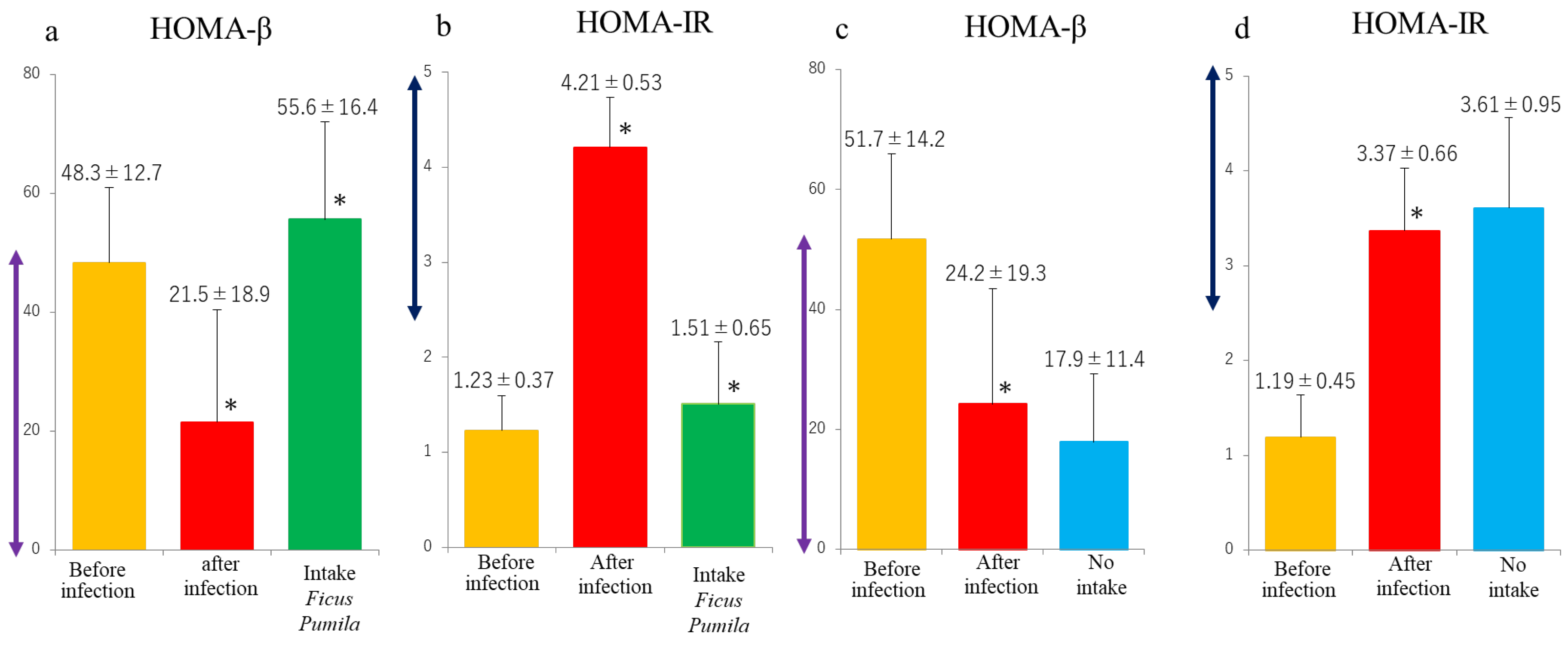

- Suzuki K, Gonda K, Kishimoto Y, et al. Potential curing and beneficial effects of Ooitabi (Ficus pumila L.) on hypertension and dyslipidaemia in Okinawa. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2021;34(2):395-401.

- Zhi-Yong Qi, Jia-Ying Zhao, Fang-Jun Lin, et al. Bioactive Compounds, Therapeutic Activities, and Applications of Ficus pumila L. Agronomy 2021;11:89.

- Wu CT, Lidsky PV, Xiao Y, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infects human pancreatic β cells and elicits β cell impairment. Cell Metab. 2021;33(8):1565-1576.

- Ji N, Zhang M, Ren L, et al. SARS-CoV-2 in the pancreas and the impaired islet function in COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11(1):1115-1125.

- Costa R, Rodrigues I, Guardão L, et al. Modulation of VEGF signaling in a mouse model of diabetes by xanthohumol and 8-prenylnaringenin: Unveiling the angiogenic paradox and metabolism interplay. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017;61(4). [CrossRef]

- Drzymała A. The Functions of SARS-CoV-2 Receptors in Diabetes-Related Severe COVID-19. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(17):9635.

- Kakavandi S, Zare I, VaezJalali M, et al. Structural and non-structural proteins in SARS-CoV-2: potential aspects to COVID-19 treatment or prevention of progression of related diseases. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21(1):110.

- Suručić R, Radović Selgrad J, Kundaković-Vasović T, et al. In Silico and In Vitro Studies of Alchemilla viridiflora Rothm-Polyphenols' Potential for Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Internalization. Molecules. 2022;27(16):5174.

- Fignani D, Pedace E, Licata G, et al. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme type 2 expression is increased in pancreatic islets of type 2 diabetic donors. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2023:e3696. [CrossRef]

- Guo TL, Germolec DR, Zheng JF, et al. Genistein protects female nonobese diabetic mice from developing type 1 diabetes when fed a soy- and alfalfa-free diet. Toxicol Pathol. 2015;43(3):435-48. [CrossRef]

- Jani V, Koulgi S, Uppuladinne VNM, et al. An insight into the inhibitory mechanism of phytochemicals and FDA-approved drugs on the ACE2-Spike complex of SARS-CoV-2 using computational methods. Chem Zvesti. 2021;75(9):4625-4648.

- Liu X, Raghuvanshi R, Ceylan FD, et al. Quercetin and Its Metabolites Inhibit Recombinant Human Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) Activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;68(47):13982-13989. [CrossRef]

- Omrani M, Keshavarz M, Nejad Ebrahimi S, et al. Potential Natural Products Against Respiratory Viruses: A Perspective to Develop Anti-COVID-19 Medicines. Front Pharmacol. 2021;11:586993. [CrossRef]

- Chen TH, Tsai MJ, Chang CS, et al. The exploration of phytocompounds theoretically combats SARS-CoV-2 pandemic against virus entry, viral replication and immune evasion. J Infect Public Health. 2023;16(1):42-54.

- Rashid Z, Fatima A, Khan A et al. Drug repurposing: identification of SARS-CoV-2 potential inhibitors by virtual screening and pharmacokinetics strategies. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2024;18(4):520-531.

- Gao J, Cao C, Shi M, et al. Kaempferol inhibits SARS-CoV-2 invasion by impairing heptad repeats-mediated viral fusion. Phytomedicine. 2023;118:154942.

- Ożarowski M, Karpiński TM. The Effects of Propolis on Viral Respiratory Diseases. Molecules. 2023;28(1):359. [CrossRef]

- Zarei A, Ramazani A, Rezaei A, et al. Screening of honey bee pollen constituents against COVID-19: an emerging hot spot in targeting SARS-CoV-2-ACE-2 interaction. Nat Prod Res. 2023;37(6):974-980.

- Salamat A, Kosar N, Mohyuddin A, et al. SAR, Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamic Simulation of Natural Inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Spike Protein. Molecules. 2024;29(5):1144.

- Tang X, Uhl S, Zhang T, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces beta cell transdifferentiation. Cell Metab. 2021;33(8):1577-1591.

- Elroy Saldanha, Suresh Rao, Mohammed Adnan, et al. Chapter 1 - Polyphenols in the Prevention of Acute Pancreatitis in Preclinical Systems of Study: A Revisit. Polyphenols: Mechanisms of Action in Human Health and Disease (Second Edition) 2018, Pages 3-9.

- Herman R, Kravos NA, Jensterle M, et al. Metformin and Insulin Resistance: A Review of the Underlying Mechanisms behind Changes in GLUT4-Mediated Glucose Transport. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1264. [CrossRef]

- van Gerwen J, Shun-Shion AS, Fazakerley DJ. Insulin signalling and GLUT4 trafficking in insulin resistance. Biochem Soc Trans. 2023;51(3):1057-1069. [CrossRef]

- Govender N, Khaliq OP, Moodley J, et al. Insulin resistance in COVID-19 and diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2021;15(4):629-634. [CrossRef]

- Behera J, Ison J, Voor MJ, et al. Diabetic Covid-19 severity: Impaired glucose tolerance and pathologic bone loss. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022; 620:180-187. [CrossRef]

- Pescaru CC, Marițescu A, Costin EO, et al. The Effects of COVID-19 on Skeletal Muscles, Muscle Fatigue and Rehabilitation Programs Outcomes. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58(9):1199. [CrossRef]

- Knudsen JR, Persson KW, Henriquez-Olguin C, et al. Microtubule-mediated GLUT4 trafficking is disrupted in insulin-resistant skeletal muscle. Elife. 2023;12:e83338.

- Akdad M, Ameziane R, Khallouki F, et al. Antidiabetic Phytocompounds Acting as Glucose Transport Stimulators. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2023;23(2):147-168. [CrossRef]

- Ganjayi MS, Karunakaran RS, Gandham S, et al. Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside from Moringa oleifera Downregulates Adipogenesis and Lipid Accumulation and Improves Glucose Uptake by Activation of AMPK/Glut-4 in 3T3-L1 Cells. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2023;33(2):334-343. [CrossRef]

- Sri Prakash SR, Kamalnath SM, Antonisamy AJ, et al. In Silico Molecular Docking of Phytochemicals for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Therapy: A Network Pharmacology Approach. Int J Mol Cell Med. 2023;12(4):372-387. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Barragán E, Estrada-Soto S, Giacoman-Martínez A, et al. Antihyperglycemic and Hypolipidemic Activities of Flavonoids Isolated from Smilax Dominguensis Mediated by Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024 Oct 30;17(11):1451.Accili D. Can COVID-19 cause diabetes? Nat Metab. 2021;3(2):123-125. [CrossRef]

- Kashyap B, Saikia K, Samanta SK, et al. Kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside from Antidesma acidum Retz. Stimulates glucose uptake through SIRT1 induction followed by GLUT4 translocation in skeletal muscle L6 cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2023;301:115788. [CrossRef]

- Thabah D, Syiem D, Pakyntein CL, et al. Potentilla fulgens upregulate GLUT4, AMPK, AKT and insulin in alloxan-induced diabetic mice: an in vivo and in silico study. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2023;129(5):1071-1083. [CrossRef]

- Asghar A, Sharif A, Awan SJ, et al. "Ficus johannis Boiss. leaves ethanolic extract ameliorate streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats by upregulating the expressions of GCK, GLUT4, and IGF and downregulating G6P". Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023;30(17):49108-49124. [CrossRef]

- Accili D. Can COVID-19 cause diabetes? Nat Metab. 2021;3(2):123-125.

- Geravandi S, Mahmoudi-Aznaveh A, Azizi Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and pancreas: a potential pathological interaction? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2021;32(11):842-845.

- Mine K, Nagafuchi S, Mori H, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Pancreatic β Cell Failure. Biology (Basel). 2021;11(1):22.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).