Submitted:

05 December 2024

Posted:

06 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

In the mining industry, mineral characterization provides data and parameters to support efficient and profitable ore processing. However, mineral characterization techniques usually require extensive image analysis, making manual large-scale image segmentation of mineral phases impractical. Considering the accuracy level currently achieved with deep learning models, they represent a potential solution to the problem of automating mineralogical ore characterization. However, training deep learning models generally requires an abundance of annotated images. Additionally, supervised learning models trained on data of a given ore sample tend to perform poorly on a sample with different characteristics, or of a different ore. In this work, we consider those different samples as pertaining to different domains: a source domain, used for training the model, and a target domain, in which the model will be tested. In such application context, domain divergences, also regarded as domain shift, may emerge from differences in mineral composition, or from distinct sample preparation processes. This research evaluates the use of the unsupervised deep domain adaptation to obtain models that generalize properly for a target domain even though no labeled target domain samples are used during training. The task of the models is to discriminate between ore and resin pixels in reflected light microscopy images. Preliminary cross-validation experiments between different domains prior to domain adaptation revealed a pronounced difficulty in the models' generalization. This fact motivates the herein presented research regarding evaluation of the potential of domain adaptation as an attempt to compensate for the loss of performance caused by domain shifts. The results of the domain adaptation showed that a significative part of the adapted models presented performance metrics considerably above the cross-validation baseline, achieving F1 score gains of up to 33% and 38% in the best cases, although in some source-target combinations limited performance gains were obtained. This indicates that the intensity of the displacement between the source and target domains may limit the success of the domain adaptation method.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Domain Adaptation Fundamentals

3. Related Works

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Domain Adversarial Neural Network (DANN)

4.2. DeepLabv3+ Implementation

4.3. Discriminator Implementation

4.4. Domain Datasets

4.4.1. Fe19 dataset

4.4.2. Fe120 dataset

4.4.3. FeM dataset

4.4.4. Cu dataset

4.4.5. Dataset Complexity

4.5. Evaluation Metrics

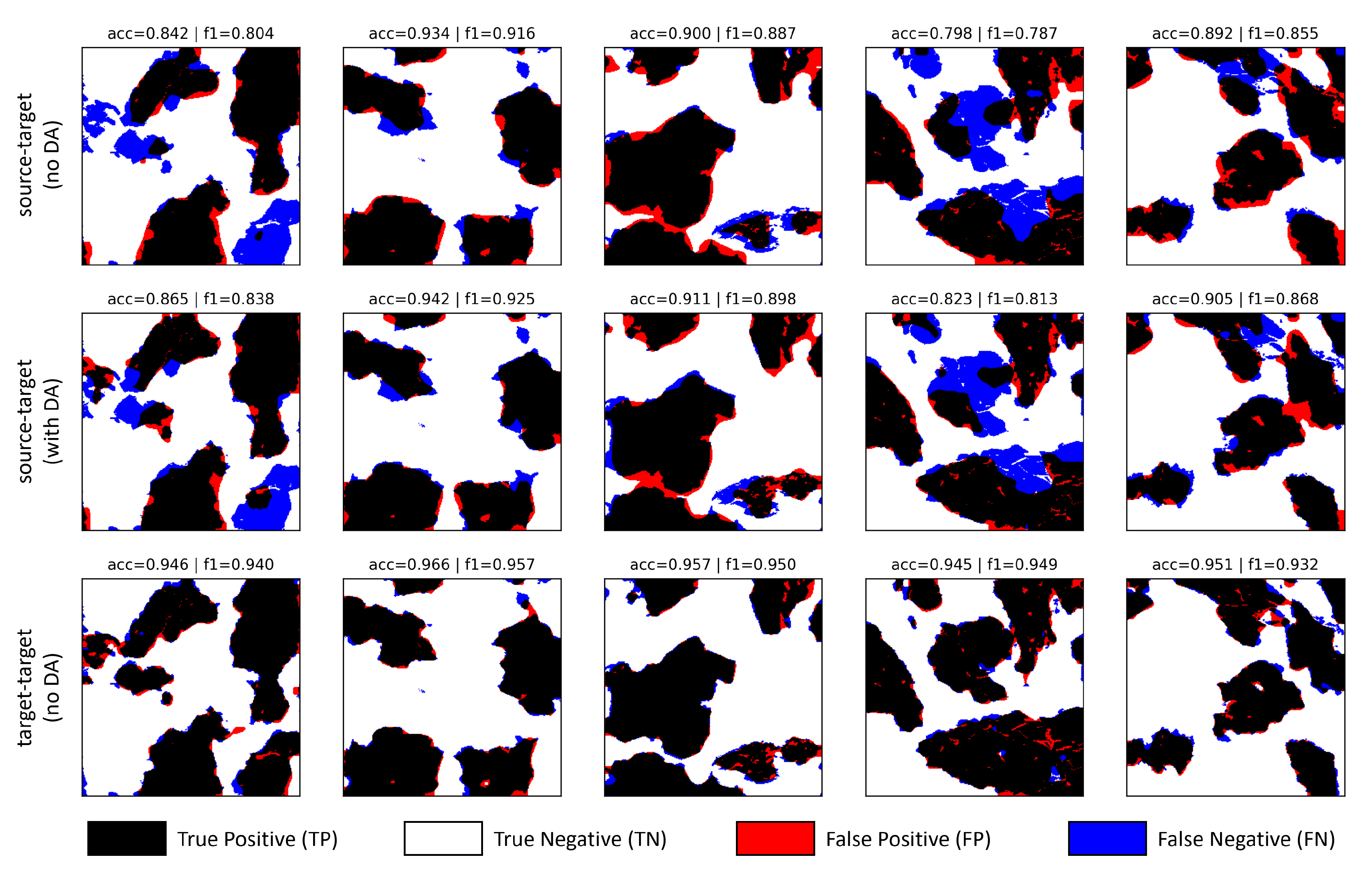

- True Positive () - pixels correctly predicted as ore;

- False Positive () - pixels predicted as ore, but should have been assigned to resin;

- True Negative () - pixels correctly predicted as resin;

- False Negative () - pixels predicted as resin, but should have been assigned to ore.

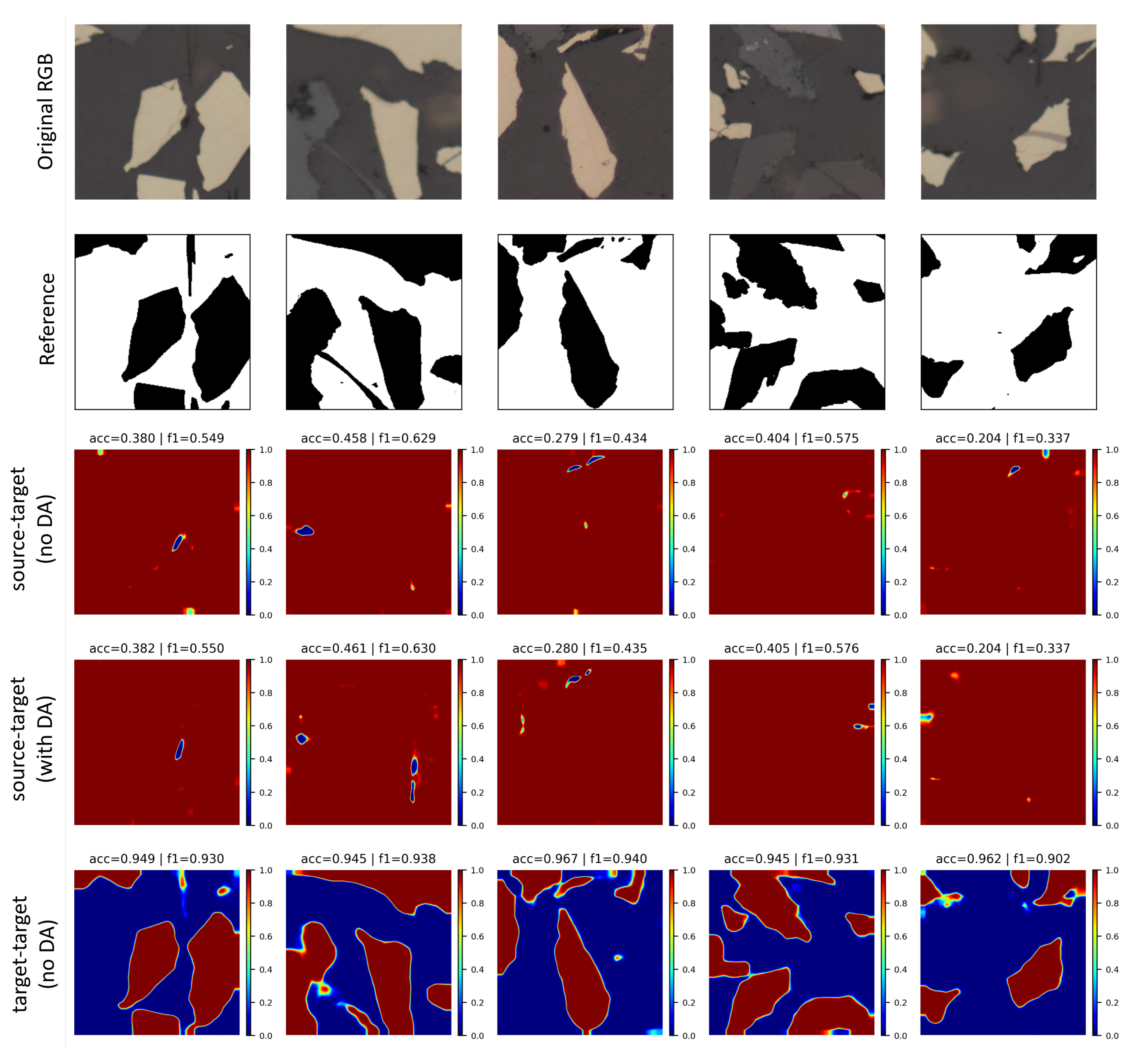

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Image Datasets

5.2. Experimental Parametrization

5.3. Cross-Validation Experiments

5.4. Domain Adaptation Experiments

| Training set | Fe19 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test set | Fe19 | Fe120 | FeM | Cu |

| Accuracy | 0.9175 (0.0086) | 0.9251 (0.0055) | 0.4354 (0.0154) | 0.3548 (0.0003) |

| Precision | 0.9148 (0.0153) | 0.9225 (0.0103) | 0.4048 (0.0066) | 0.3538 (0.0001) |

| Recall | 0.9287 (0.0036) | 0.9348 (0.0072) | 0.9757 (0.0096) | 0.9989 (0.0007) |

| F1 score | 0.9216 (0.0069) | 0.9285 (0.0035) | 0.5721 (0.0070) | 0.5225 (0.0001) |

| Avg. precision | 0.9753 (0.0066) | 0.9804 (0.0032) | 0.8213 (0.0194) | 0.6085 (0.2050) |

| Training set | Fe120 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test set | Fe19 | Fe120 | FeM | Cu |

| Accuracy | 0.9258 (0.0063) | 0.9345 (0.0092) | 0.4861 (0.0380) | 0.4073 (0.1017) |

| Precision | 0.9266 (0.0080) | 0.9375 (0.0088) | 0.4282 (0.0189) | 0.3783 (0.0481) |

| Recall | 0.9327 (0.0037) | 0.9398 (0.0087) | 0.9666 (0.0099) | 0.9876 (0.0202) |

| F1 score | 0.9296 (0.0056) | 0.9386 (0.0081) | 0.5932 (0.0177) | 0.5447 (0.0438) |

| Avg. precision | 0.9809 (0.0034) | 0.9867 (0.0030) | 0.8618 (0.0181) | 0.8064 (0.0837) |

| Training set | FeM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test set | Fe19 | Fe120 | FeM | Cu |

| Accuracy | 0.5199 (0.0026) | 0.5270 (0.0162) | 0.9557 (0.0010) | 0.3534 (0.0001) |

| Precision | 0.5249 (0.0028) | 0.5295 (0.0151) | 0.9467 (0.0033) | 0.3534 (0.0000) |

| Recall | 0.9748 (0.0111) | 0.9824 (0.0151) | 0.9384 (0.0036) | 0.9999 (0.0001) |

| F1 score | 0.6823 (0.0025) | 0.6881 (0.0162) | 0.9425 (0.0014) | 0.5222 (0.0001) |

| Avg. precision | 0.6255 (0.0929) | 0.6228 (0.0873) | 0.9884 (0.0004) | 0.4940 (0.1976) |

| Training set | Cu | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test set | Fe19 | Fe120 | FeM | Cu |

| Accuracy | 0.7033 (0.0233) | 0.7110 (0.0189) | 0.8894 (0.0060) | 0.9388 (0.0026) |

| Precision | 0.8936 (0.0246) | 0.8960 (0.0223) | 0.8666 (0.0190) | 0.9380 (0.0067) |

| Recall | 0.4759 (0.0368) | 0.5131 (0.0265) | 0.8448 (0.0132) | 0.8855 (0.0096) |

| F1 score | 0.6204 (0.0349) | 0.6522 (0.0256) | 0.8553 (0.0064) | 0.9109 (0.0040) |

| Avg. precision | 0.8015 (0.0368) | 0.8201 (0.0335) | 0.9284 (0.0032) | 0.9678 (0.0011) |

| Source | Target | |

|---|---|---|

| Fe19 | FeM | |

| Fe19 | Cu | |

| FeM | Fe19 | |

| FeM | Cu | |

| Cu | Fe19 | |

| Cu | FeM |

| Metrics | Performance Gap | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | F1 | AP | Accuracy [%] | F1 [%] | AP [%] | |

|

source-target (no DA) |

0.4405 | 0.5713 | 0.7241 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

|

source-target (DA) |

0.7079 | 0.7118 | 0.8007 | 52.35 | 38.41 | 29.29 |

|

target-target (no DA) |

0.9513 | 0.9369 | 0.9856 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Metrics | Performance Gap | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | F1 | AP | Accuracy [%] | F1 [%] | AP [%] | |

|

source-target (no DA) |

0.3556 | 0.5227 | 0.4781 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

|

source-target (DA) |

0.4009 | 0.5315 | 0.4749 | 7.743 | 2.248 | -0.6612 |

|

target-target (no DA) |

0.9419 | 0.9153 | 0.9707 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Metrics | Performance Gap | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | F1 | AP | Accuracy [%] | F1 [%] | AP [%] | |

|

source-target (no DA) |

0.5414 | 0.6648 | 0.6898 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

|

source-target (DA) |

0.5469 | 0.6688 | 0.6984 | 1.454 | 1.464 | 3.008 |

|

target-target (no DA) |

0.9181 | 0.9395 | 0.9750 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Metrics | Performance Gap | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | F1 | AP | Accuracy [%] | F1 [%] | AP [%] | |

|

source-target (no DA) |

0.3576 | 0.5237 | 0.6254 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

|

source-target (DA) |

0.3534 | 0.5222 | 0.6771 | -0.7228 | -0.3755 | 14.96 |

|

target-target (no DA) |

0.9419 | 0.9153 | 0.9707 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Metrics | Performance Gap | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | F1 | AP | Accuracy [%] | F1 [%] | AP [%] | |

|

source-target (no DA) |

0.6962 | 0.6057 | 0.7889 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

|

source-target (DA) |

0.7032 | 0.6286 | 0.7957 | 2.871 | 7.393 | 3.762 |

|

target-target (no DA) |

0.9181 | 0.9395 | 0.9750 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Metrics | Performance Gap | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | F1 | AP | Accuracy [%] | F1 [%] | AP [%] | |

|

source-target (no DA) |

0.8518 | 0.7887 | 0.8809 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

|

source-target (DA) |

0.8760 | 0.8380 | 0.9133 | 24.32 | 33.25 | 30.97 |

|

target-target (no DA) |

0.9513 | 0.9369 | 0.9856 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASPP | Atrous spatial pyramid pooling |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CRF | Conditional Random Fields |

| DA | Domain Adaptation |

| DANN | Domain Adversarial Neural Network |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| FN | False negative |

| FP | False positive |

| Domain discriminator | |

| Feature Extractor | |

| Label predictor | |

| GRL | Gradient reversal layer |

| OS | Output Stride |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| TN | True negative |

| TP | True positive |

References

- Gomes, O.d.F.M.; Iglesias, J.C.A.; Paciornik, S.; Vieira, M.B. Classification of hematite types in iron ores through circularly polarized light microscopy and image analysis. Minerals Engineering 2013, 52, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, R.; Stanley, C.J. Specular reflectance data for quartz and some epoxy resins: implications for digital image analysis based on reflected light optical microscopy. Ninth International Congress for Applied Mineralogy, 2008, pp. 703–705.

- Wang, M.; Deng, W. Deep visual domain adaptation: A survey. Neurocomputing 2018, 312, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, P.J.S.; da Costa, G.A.O.P.; Feitosa, R.Q.; Adarme, M.X.O.; de Almeida, C.A.; Heipke, C.; Rottensteiner, F. An unsupervised domain adaptation approach for change detection and its application to deforestation mapping in tropical biomes. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2021, 181, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittich, D.; Rottensteiner, F. Wittich, D.; Rottensteiner, F. Appearance Based Deep Domain Adaptation for the Classification of Aerial Images. CoRR 2021, abs/2108.07779. [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Nguyen, T.; Ho, N.; Bui, H.; Phung, D. LAMDA: Label Matching Deep Domain Adaptation. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research 2021, 139, 6043–6054. [Google Scholar]

- Ganin, Y.; Lempitsky, V. Unsupervised domain adaptation by backpropagation. Skoltech 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A Survey on Transfer Learning. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2010, 22, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuia, D.; Persello, C.; Bruzzone, L. Domain Adaptation for the Classification of Remote Sensing Data: An Overview of Recent Advances. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2016, 4, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, K.; Khoshgoftaar, T.; Wang, D. A survey of transfer learning. J Big Data 2016, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csurka, G. A comprehensive survey on domain adaptation for visual applications. In Domain Adaptation in Computer Vision Applications, 1 ed.; Csurka, G., Ed.; Springer: Cham, 2017; Vol. 1, Advances in Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, chapter 1, pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.; Cook, D.J. A Survey of Unsupervised Deep Domain Adaptation. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2020, 11, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masci, J.; Meier, U.; Ciresan, D.; Schmidhuber, J.; Fricout, G. Steel defect classification with Max-Pooling Convolutional Neural Networks. The 2012 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 2012, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Gu, Q.; Hao, H.; Li, N. Feature Extraction and Grain Segmentation of Sandstone Images Based on Convolutional Neural Networks. 2018 24th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), 2018, pp. 2636–2641. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jing, H.; Wang, L.; Zhao, S. Ore image segmentation method using U-Net and Res_Unet convolutional networks. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 9396–9406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, T. Semantic Segmentation of Iron Ore Pellets with Neural Networks. Master’s thesis, Luleå University of Technology, Department of Computer Science, Electrical and Space Engineering, 2019.

- Lorenzoni, R.; Curosu, I.; Paciornik, S.; Mechtcherine, V.; Oppermann, M.; Silva, F. Semantic segmentation of the micro-structure of strain-hardening cement-based composites (SHCC) by applying deep learning on micro-computed tomography scans. Cement and Concrete Composites 2020, 108, 103551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.W.; Qiu, K.F.; Petrelli, M.; Hou, Z.L.; Santosh, M.; Yu, H.C.; Armstrong, R.T.; Deng, J. The application of “transfer learning” in optical microscopy: the petrographic classification of metallic minerals. American Mineralogist 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows. International Conference on Computer Vision 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. ImageNet: A Large-Scale Hierarchical Image Database. Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. CoRR 2015, abs/1512.03385, [1512.03385]. [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.; Huang, D.; Cheng, L.; Jia, J.; Xiong, C.; Zhang, Y. Efficient and Lightweight Framework for Real-Time Ore Image Segmentation Based on Deep Learning. Minerals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Zhang, C.; Cao, Q. Image Segmentation Method on Quartz Particle-Size Detection by Deep Learning Networks. Minerals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukharev, A.; Budennyy, S.; Lokhanova, O.; Belozerov, B.; Zhukovskaya, E. The Task of Instance Segmentation of Mineral Grains in Digital Images of Rock Samples (Thin Sections). 2018 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations (IC-AIAI), 2018, pp. 18–23. [CrossRef]

- Caldas, T.D.P.; Augusto, K.S.; Iglesias, J.C.A.; Ferreira, B.A.P.; Santos, R.B.M.; Paciornik, S.; Domingues, A.L.A. A methodology for phase characterization in pellet feed using digital microscopy and deep learning. Minerals Engineering 2024, 212, 108730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollar, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 201. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, B.A.P.; Augusto, K.S.; Iglesias, J.C.A.; Caldas, T.D.P.; Santos, R.B.M.; Paciornik, S. Instance segmentation of quartz in iron ore optical microscopy images by deep learning. Minerals Engineering 2024, 211, 108681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittich, D.; Rottensteiner, F. Adversarial Domain Adaptation for the Classification os Arial Images and Height Data Using Convolutional Neural Networks. ISPRS 2019, IV-2/W7, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, E.; Hoffman, J.; Saenko, K.; Darrell, T. Adversarial discriminative domain adaptation. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 7167–7176.

- Du, M.; Liang, K.; Zhang, L.; Gao, H.; Liu, Y.; Xing, Y. Deep-Learning-Based Metal Artefact Reduction With Unsupervised Domain Adaptation Regularization for Practical CT Images. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2023, 42, 2133–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, P.; Ostwald, G.; Feitosa, R.; Ortega, M.; Bermudez, J.; Turnes, J. Domain-Adversarial Neural Networks for Deforestation Detection in Tropical Forests. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, P.; Ostwald, G.; Adarme, M.; Castro, J.; Feitosa, R. Weakly Supervised Domain Adversarial NeuralNetwork for Deforestation Detection in Tropical Forests. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2023, 16, 10264–10278. [Google Scholar]

- Filippo, M.P.; Gomes, O.d.F.M.; Ostwald, G.A.O.P.d.; Abelha, G.L.A. Deep learning semantic segmentation of opaque and non-opaque minerals from epoxy resin in reflected light microscopy images. Minerals Engineering 2021, 170, 107007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallat, S. A Wavelet Tour of Signal Processing; Academic Press, 2008.

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Rethinking Atrous Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation, 2017, [arXiv:cs.CV/1706.05587]. arXiv:cs.CV/1706.05587]. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. DeepLab: Semantic Image Segmentation with Deep Convolutional Nets, Atrous Convolution, and Fully Connected CRFs, 2017, [arXiv:cs.CV/1606.00915]. arXiv:cs.CV/1606.00915]. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Rabinovich, A.; Berg, A.C. ParseNet: Looking Wider to See Better, 2015, [arXiv:cs.CV/1506.04579]. arXiv:cs.CV/1506.04579]. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-Decoder with Atrous Separable Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation, 2018, [arXiv:cs.CV/1802.02611]. arXiv:cs.CV/1802.02611]. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, O.d.F.M.; Paciornik, S. Multimodal Microscopy for Ore Characterization. In Scanning Electron Microscopy; Kazmiruk, V., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2012; chapter 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; Tinevez, J.Y.; White, D.J.; Hartenstein, V.; Eliceiri, K.; Tomancak, P.; Cardona, A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, O.d.F.M.; Vasques, F.d.S.G.; Neumann, R. Cathodoluminescence and reflected light correlative microscopy for iron ore characterization. Process Mineralogy’18, 2018.

- King, R.P.; Schneider, C.L. An effective SEM-based image analysis system for quantitative mineralogy. KONA Powder and Particle Journal 1993, pp. 165–177.

- Gomes, O.d.F.M. Processamento de imagem digital com FIJI/ImageJ, 2018. Workshop em Microscopia Eletrônica e por Sonda. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, O.d.F.M.; Paciornik, S. Iron Ore Quantitative Characterisation Through Reflected Light-Scanning Electron Co-Site Microscopy. Ninth International Congress for Applied Mineralogy, 2008, p. 699–702.

- Gomes, O.d.F.M.; Paciornik, S. Co-Site Microscopy-Combining Reflected Light Microscopy and Scanning Electron Microscopy to Perform Ore Mineralogy. Ninth International Congress for Applied Mineralogy, 2008, p. 695–698.

- Caliński, T.; Harabasz, J. A dendrite method for cluster analysis. Communications in Statistics-theory and Methods 1974, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. ICLR 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glorot, X.; Bengio, Y. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; PMLR: Chia Laguna Resort, Sardinia, Italy, 2010; Vol. 9, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 249–256.

| Layer | Output shape |

|---|---|

| Input | (16, 16, 256) |

| Flatten | (65536, 1) |

| Dense | (1024, 1) |

| ReLU | |

| Dense | (1024, 1) |

| ReLU | |

| Dense | (2, 1) |

| Softmax |

| Domain | Clusters | |

|---|---|---|

| FeM | 9 | |

| Fe19 | 25 | |

| Fe120 | 25 | |

| Cu | 15 |

| Dataset | Total | Training + Validation | Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe19 | 19 | 15 | 4 |

| Fe120 | 120 | 116 | 4 |

| FeM | 81 | 77 | 4 |

| Cu | 121 | 117 | 4 |

| Dataset | Training + Validation | Test |

|---|---|---|

| Fe19 | 540 | 36 |

| Fe120 | 4176 | 36 |

| FeM | 1848 | 24 |

| Cu | 2808 | 24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).