1. Introduction

Microorganisms (such as bacteria, archaea, and fungi) are among the most diverse and versatile organisms on Earth and colonize and proliferate in various ecosystems. Antarctica is not an exception, since microorganisms are dominant and crucial for the functioning and stability of the different ecological niches that they occupy in soils [

1]. Antarctic microorganisms have coevolved and adapted to the extreme and unpredictable Antarctic climate [

2,

3,

4], which has led to the selection of strains and species with unusual metabolic properties that have sparked the interest of scientists and industry [

5,

6,

7]. As a result, diverse studies in Antarctica have focused on revealing the structures and functions of the microbial communities in soils and plants and evaluating their biotechnological potential [

8,

9,

10,

11]. However, most of these studies have focused on tropical and temperate latitudes, and our knowledge of the diversity, role and dynamics of microbial communities in the plant‒soil‒microbe continuum in Antarctica is still lacking.

Climate change is currently the main challenge facing our planet, particularly concerning soils and their biodiversity [

12]. In this sense, the expansion of ice-free habitats in the Antarctic Peninsula is projected [

13,

14], where microorganisms play crucial roles in soil-forming processes and biogeochemical cycling, promoting environmental changes that facilitate the colonization and succession of organisms with higher trophic levels (e.g., lichens, mosses, fungi, small invertebrates and birds) [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. These organisms incorporate organic compounds into the soil matrix and promote the colonization and establishment of specific native vascular plant species, such as

Deschampsia antarctica and

Colobanthus quitensis, which also regulate soil properties [

21].

Under a climate warming scenario in Antarctica, studies have recently described the influence of microorganisms on initial soil formation near glaciers [

22] and the influence of site conditions and vegetation on nutrient speciation (phosphorus and sulfur) in ice-free soils [

23]. In addition, studies have revealed not only high microbial diversity in Antarctic soils and plants but also beneficial plant‒microbe interactions [

24] and microbial differentiation between plant compartments, such as the rhizosphere, endosphere and phyllosphere [

25]. Studies on soils obtained from deglaciation and their concomitant succession of microbial communities could also provide indications of how climate change at the global scale may modulate the formation, biogeochemical processes and biodiversity of soils at the regional scale [

22,

23]. In this context, Ecology Glacier, located on King George Island (South Shetland Islands, Maritime Antarctic), is a highly relevant site for studying soil formation and associated microbial communities because it has experienced a high level of deglaciation over the past decades [

26]; therefore, it has traditionally been subjected to multiple interdisciplinary studies [

27,

28,

29]. For this reason, in this study, we aimed to describe the compositions of prokaryote (bacteria and archaea) and eukaryote (fungi) communities associated with soils collected from permafrost (frozen soil), moraine (debris and sediment left behind by deglaciation) and

D. antartica rhizosphere (colonized soil) near Ecology Glacier.

2. Materials and Methods

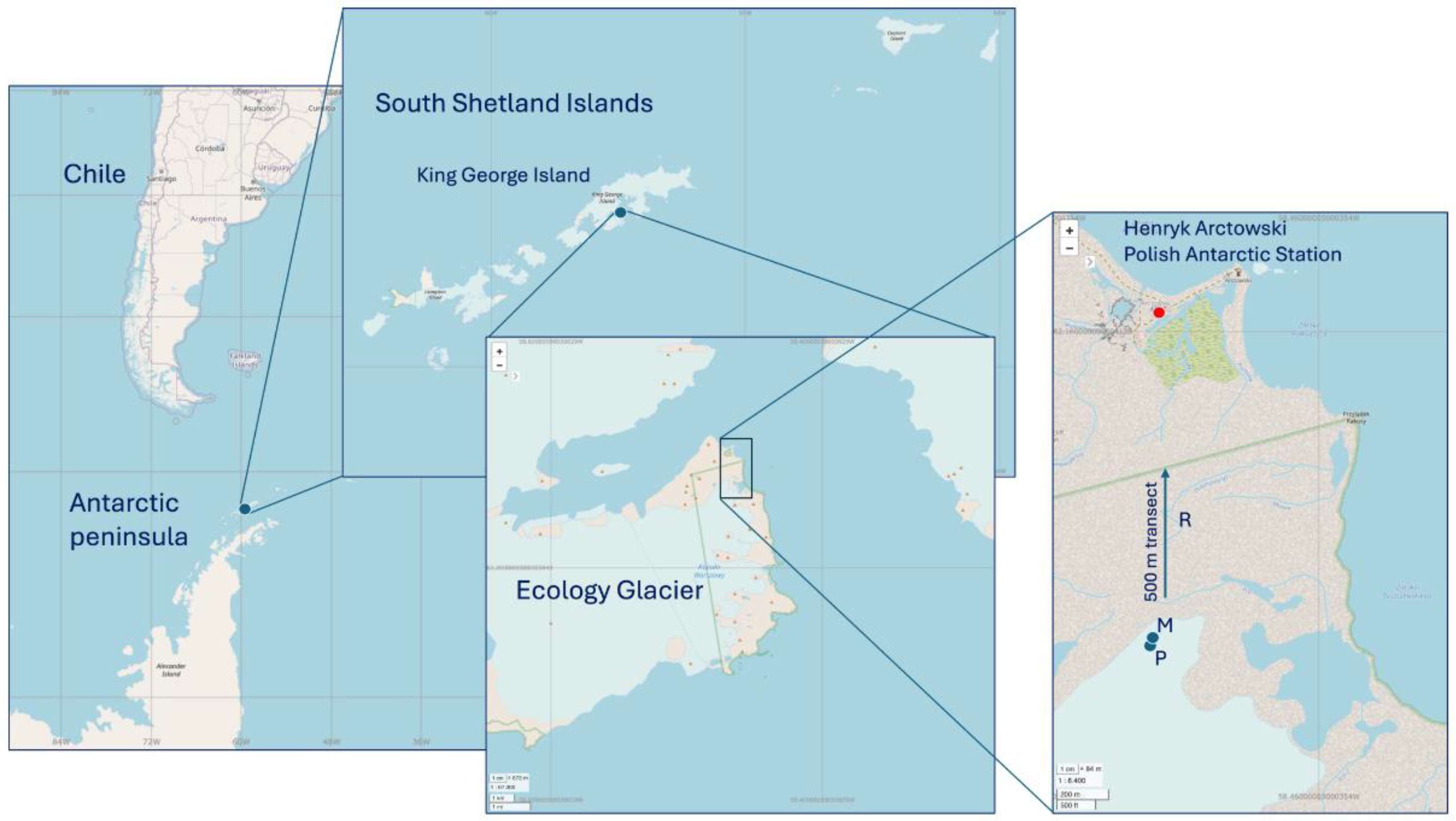

2.1. Sampling

Soil samples were collected near Ecology Glacier, which is located inside the Antarctic specially protected area (ASPA, N°128: Occidental coast of Admiralty Bay), during the 58

th Scientific Antarctic Expedition (ECA58) in the summer season (November 2021 to March 2022), and following the protocols and supervision of the Chilean Antarctic Institute (INACH;

https://www.inach.cl/). The samples were coded as ‘Permafrost (P)’, ‘Moraine (M)’ or ‘Rhizosphere (R)’ and were collected at the sites described in

Figure 1. Soil samples of both P (62°10’15.4” S, 58°28’21.6” W) and M (62°10’14.4” S, 58°28’20.5” W) were collected by removing a 10-cm surface layer and then placing 0.5 to 1 kg of the underlying soil into Whirl-Pak® sterile bags (Madison, WI, USA) using an aseptic spade. The R samples were subsequently collected from soil patches covered with the vascular plant

D. antarctica. Six samples were randomly taken along a 500-m transect from the moraine to the Henryk Arctowski Polish Antarctic Station (

Figure 1), and a clean spade was used to remove intact roots from the soil. Fifty grams of collected rhizosphere samples were placed within sterile 50-mL Falcon plastic tubes. The samples were kept at low temperature and transported for analysis.

2.2. Soil Physicochemical Properties

The soil samples were subjected to physicochemical analysis following standard procedures by the Soil Laboratory at the Universidad de La Frontera (Temuco, Chile). The pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were measured in 1:2.5 and 1:5 sediment/deionized water suspensions with a high-grade benchtop meter (model HI5522; Hanna Instruments Ltd., Leighton Buzzard, UK), respectively. The organic matter (OM) contents were estimated via wet digestion (the Walkley‒Black method; [

30]. Inorganic phosphorus (P

Olsen) was extracted using the bicarbonate method (pH 8.5 in 0.5 M NaHCO

3) and analyzed using the molybdate-blue method [

31]. Total carbon (TC) and total nitrogen (TN) were determined on an automated elemental analyzer EA 3000 (Eurovector, Milano, IT) in aliquots (1.5 to 2.5 mg) of sieved freeze-dried soils (150 μm pore size) as recommended by Schumacher [

32]. The elemental compositions of TC and TN were calculated using a calibration curve with EDTA as a standard (99.4% purity; LECO®, USA) and expressed as mg kg

−1 dw. Exchangeable cations (e.g., Ca

+2, Mg

2+, Na

+ and K

+) were extracted with 1 M CH

3COONH

4 at pH 7.0 and analyzed via flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry (FAAS) [

33]. Exchangeable iron (Fe

3+) was extracted with wet soil‒water at a ratio of 1:1 and analyzed via FAAS [

34].

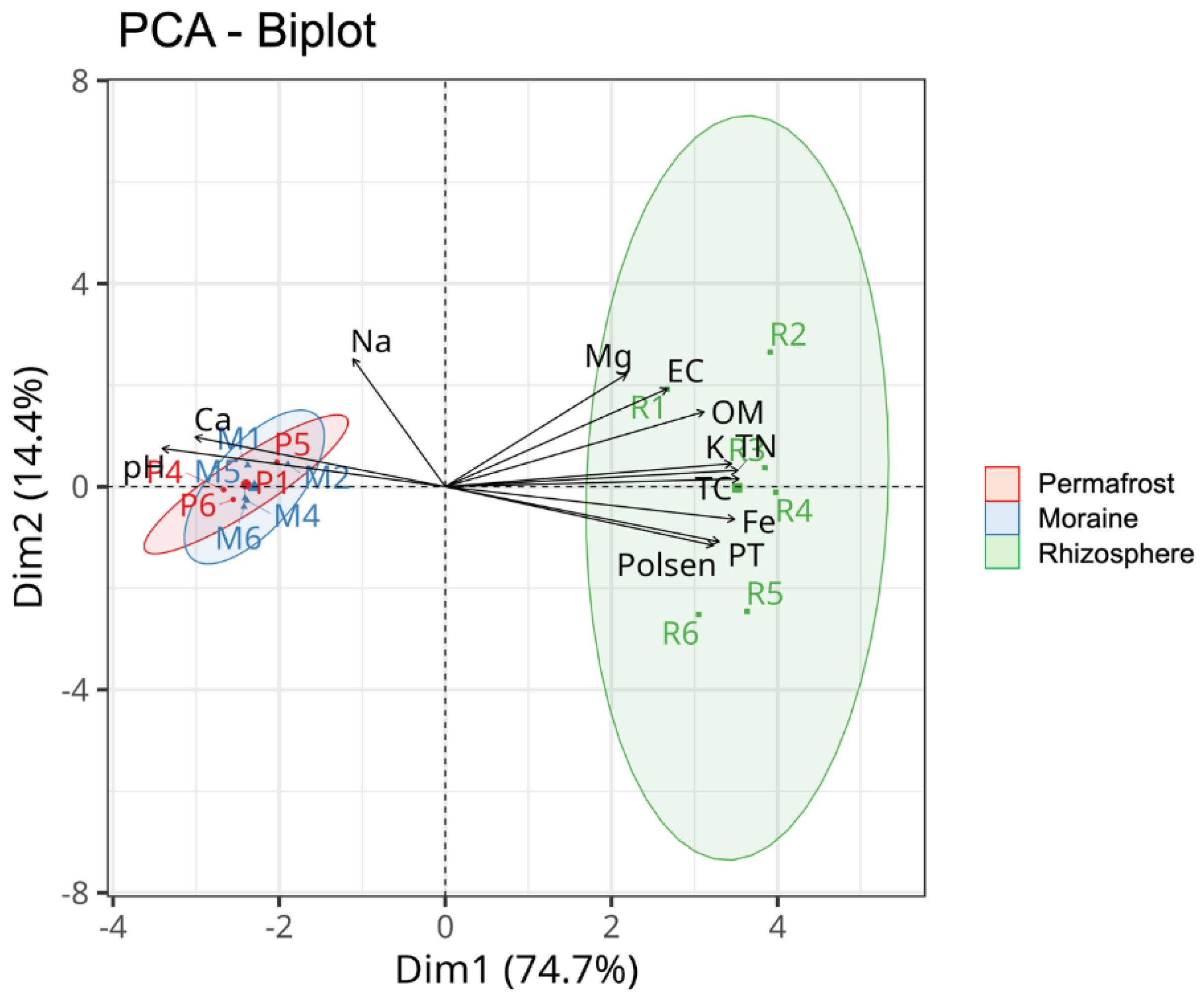

Significant differences in the physiochemical properties among the soil samples were analyzed via one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s HSD test (

p ≤ 0.05). In addition, with the centered and scaled values of the physicochemical properties of the soil samples, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed via R version 4.2.3 (

https://cran.r-project.org/ ) to visualize their influence on each soil sample.

2.3. DNA Isolation

First, each soil sample was sieved to remove rocks, small stones and/or root debris from the collected samples. Then, 500 mg of each soil sample was used for total DNA isolation using a FastDNA™ Spin Kit (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA, USA). Mechanical lysis was performed using glass beads of different sizes (0.1 mm, 1.4 mm and 4 mm) inside a 2-mL cryotube under shaking at 6 m s-1 for 45 s (three pulses) with a FastPrep-24™ homogenizer (MP Biomedicals), placing the samples on ice between each pulse, and then proceeding according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The DNA integrity was corroborated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified with an Invitrogen Qubit® 4 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) using a Qubit® dsDNA BR Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). Finally, the DNA extracts were stored at -20°C until use.

2.4. Amplicon Sequencing and Data Analysis

Primer sets targeting bacteria, archaea and fungi were used to construct 16S rRNA and ITS libraries (

Table 1), which were sequenced with a NovaSeq 6000 Sequencing System (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) using the services provided by the Novogene Corporation Inc. (

https://www.novogene.com/us-en/; Sacramento, CA, USA). The multiplexed reads were processed using the QIIME 2 version 2022.2 plugin [38]. Amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were generated via the paired-read DADA2 plugin [39] and taxonomically assigned using the scikit-learn plugin with a naive Bayes classifier trained on the SILVA 138 database ([40];

https://www.arb-silva.de/documentation/release-138/) for bacterial and archaeal ASVs or the UNITE database version 9.0 ([41];

https://unite.ut.ee/) for fungal ASVs. Only ASVs classified at least at the phylum level in the respective domain (bacteria, archaea, or fungi) were retained. Unfortunately, libraries of archaeal rRNA and fungal ITS could not be obtained by PCR in the P samples; therefore, they were discarded in this study.

For the diversity analyses, ASV abundance tables were first rarefied to 38,000, 1,000 and 3,000 counts per sample for bacteria, archaea and fungi, respectively. Then, the R package, vegan version 2.6-6.1 by Oksanen et al. [42]; (

https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.vegan), was used to calculate the alpha diversity indices (Shannon index, richness, and Pielou’s evenness) for each sample. Using R version 4.2.3, the Kruskal‒Wallis test was applied to assess statistically significant differences in the alpha diversity indices among groups when there were more than two groups. For pairwise comparisons, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used. Additionally, using Bray‒Curtis dissimilarities between samples and nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) were performed with the vegan package to visualize the beta diversity, and permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) implemented in QIIME 2 was used to test for significant differences between groups of samples.

Raw sequencing data obtained from amplicon sequencing were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA;

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under BioProject PRJNA11786053.

3. Results

The physicochemical properties of the soil samples are shown in

Table 2. The P and M soil samples presented neutral pH levels, with average values of 7.6 and 7.8, respectively. Moreover, the pH of the R soil samples was slightly acidic, with an average value of 5.3. A significantly (

p ≤ 0.05) greater average value of EC (51.2 μS cm

−1) was observed in the R samples than in the P (32.2 μS cm

−1) and M (32.7 μS cm

−1) samples. In terms of soil nutrients, significantly (

p ≤ 0.05) greater average values of total P (366 mg kg

−1), total N (8.5 mg kg

−1), total C (79.7 mg kg

−1) and P

Olsen (119 mg kg

−1) were detected in the R samples than in the P (109.9, 1.1, 3.3 and 16 mg kg

−1, respectively) and M (109, 1.5, 4 and 11.3 mg kg

−1, respectively) samples. Similarly, significantly (

p ≤ 0.05) higher average values of Mg (1,013.3 mg kg

−1), K (396.9 mg kg

−1) and Fe (152.1 mg kg

−1) were obtained for the R samples. In contrast, the P and M samples presented significantly (

p ≤ 0.05) greater average values of Na (669 mg kg

−1) and Ca (3,392 mg kg

−1). The considerable influence of the physicochemical properties on the R samples with respect to the P and M samples was visualized via PCA (

Figure 2).

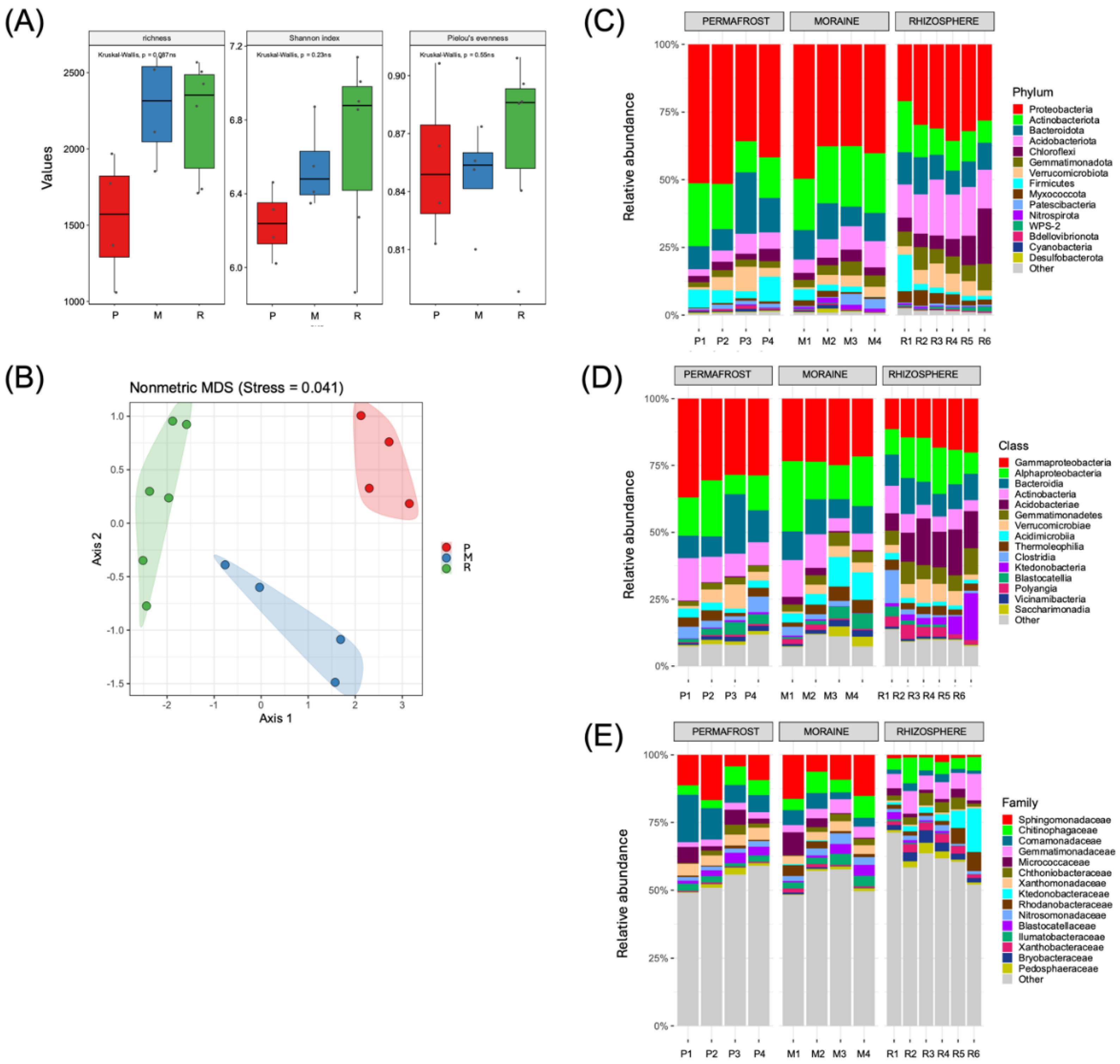

With respect to the bacterial communities, our results revealed a greater richness of ASVs in the M (1,853 to 2,601) and R (1,710 to 2,567) samples than in the P samples (1,059 to 1,968); however, these differences were not significant (

p > 0.05) according to the Kruskal−Wallis test (

Figure 3A). Similarly, the Shannon and Pielou evenness indices did not significantly differ among the samples. The Shannon index ranged from 5.87 to 7.14, whereas Pielou’s evenness index ranged from 0.79 to 0.91. In contrast, NMDS analysis revealed significant (

p ≤ 0.05) differences among the soil bacterial communities in the soil samples according to the Bray−Curtis dissimilarity metric (

Figure 3B).

All the samples presented relatively high relative abundances of members belonging to the phylum Proteobacteria (Pseudomonadota), ranging from 35.8% to 51.5%, 37.6% to 49.7% and 20.9% to 35.6% in P, M and R, respectively (

Figure 3C). In the P and M samples, members of the phyla Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes also presented relatively high relative abundance values, ranging from 8.2% to 23.2% and from 7.3% to 22.7%, respectively, whereas in the R samples, the phyla Acidobacteria (12.2% to 20.6%), Actinobacteria (8.2% to 18.9%) and Bacteroidota (8.9% to 13.7%) were more abundant. At the class level, the P and M samples were dominated by Gammaproteobacteria (21.6% to 36.9%) and Alphaproteobacteria (7.3% to 26.2%), followed by Bacteroidia (7.2% to 22.2%) and Actinobacteria (4.8% to 15.9%) (

Figure 3D). Interestingly, in addition to other dominant classes, Acidobacteria (Terriglobia) was exclusively observed as a dominant taxon (6.47% to 17.42%) in the R samples. At the family level, the P samples were characterized mainly by members belonging to the families, Sphingomonadaceae (4.3% to 16.7%), Comamonadaceae (6.3% to 17.5%) and Chitinophagaceae (2.9% to 6.9%) (

Figure 3E). The dominance of the same families was also observed in the M samples, with ranges of 6.2% to 16.3% and 4.2% to 8.1% for Sphingomonadaceae and Chitinophagaceae, respectively. In contrast, the R samples were dominated by the families Gemmatimonadaceae (5.2% to 9.8%), Chitinophagaceae (3.9% to 9.5%) and Ktedonobacteraceae (0.9% to 16.1%).

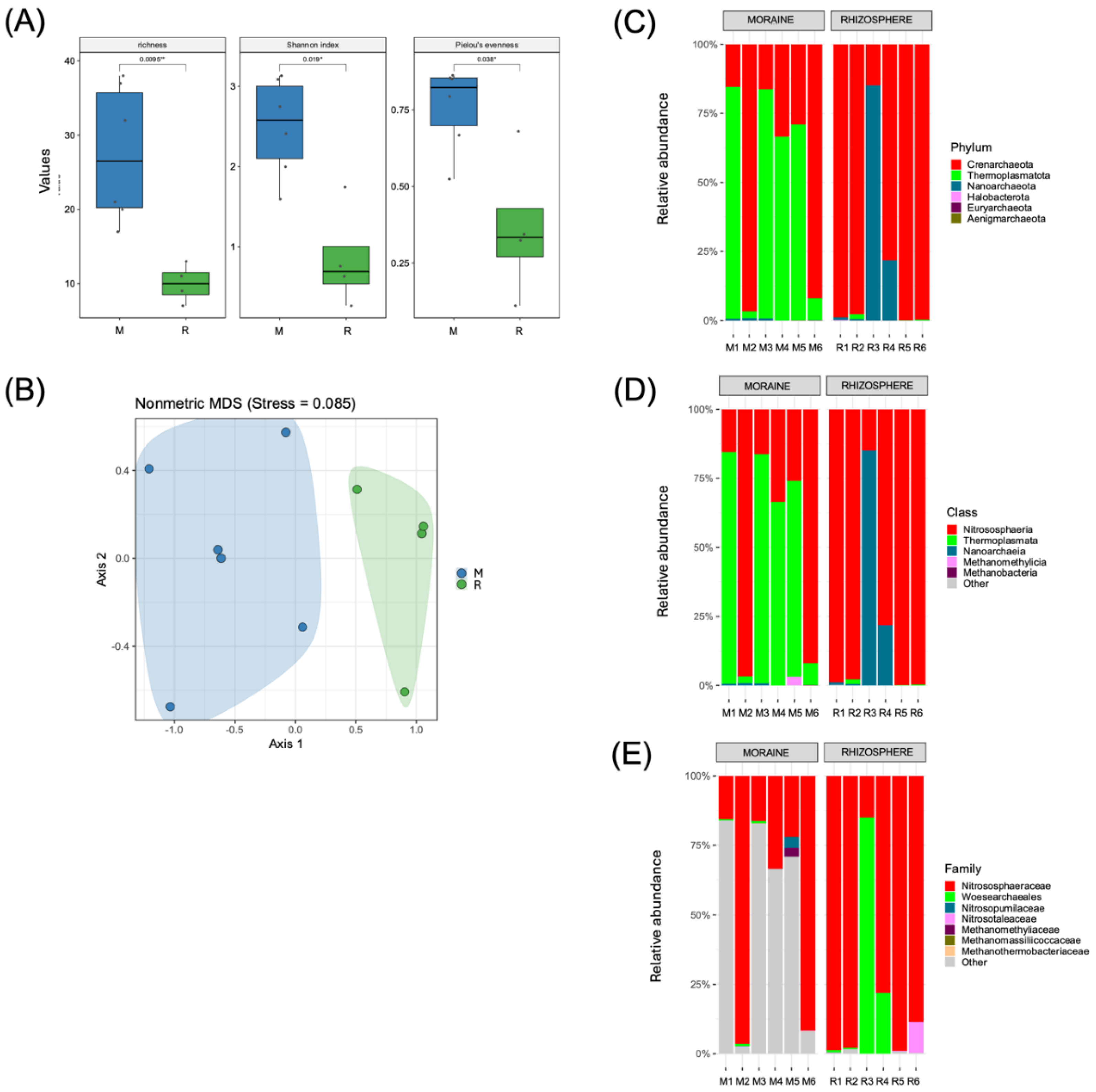

In contrast to the bacterial communities, our results for the soil archaeal communities revealed significantly (

p ≤ 0.05) greater richness and diversity in the M soil samples (17 to 38 for ASV richness, 1.59 to 3.13 for the Shannon index and 0.52 to 0.86 for the Pielou evenness index) than in the R samples (7 to 13 for ASV richness, 0.27 to 1.74 for the Shannon index and 0.11 to 0.68 for the Pielou evenness index) (

Figure 4A). These differences were also evident in the NMDS analysis, which revealed clear and significant (

p ≤ 0.05) differences between both soil samples according to the Bray−Curtis dissimilarity metric (

Figure 4B).

In the M samples, the soil archaeal community was dominated by members of the phyla Thermoplasmatota (2.5% to 83.9%) and Crenarchaeota (15.5% to 96.7%). In comparison, the archaeal community in the R samples was almost exclusively dominated by members of Crenarchaeota (14.9% to 99.9%), except for the R3 sample, which contained 85.10% Nanoarchaeota (

Figure 4C). At the class level, the M samples were dominated by members of the classes Thermoplasmata (2.5% to 83.9%) and Nitrososphaeria (15.5% to 96.7%) (

Figure 4D). Accordingly, the dominant family in the M samples was Nitrososphaeraceae (15.5% to 96.5%) (

Figure 4E). In the R samples, most of the sequences were assigned to Nitrososphaeraceae (14.9% to 98.9%); however, Woesearchaeales was also dominant in two samples (21.8% and 85.1%) (

Figure 4E).

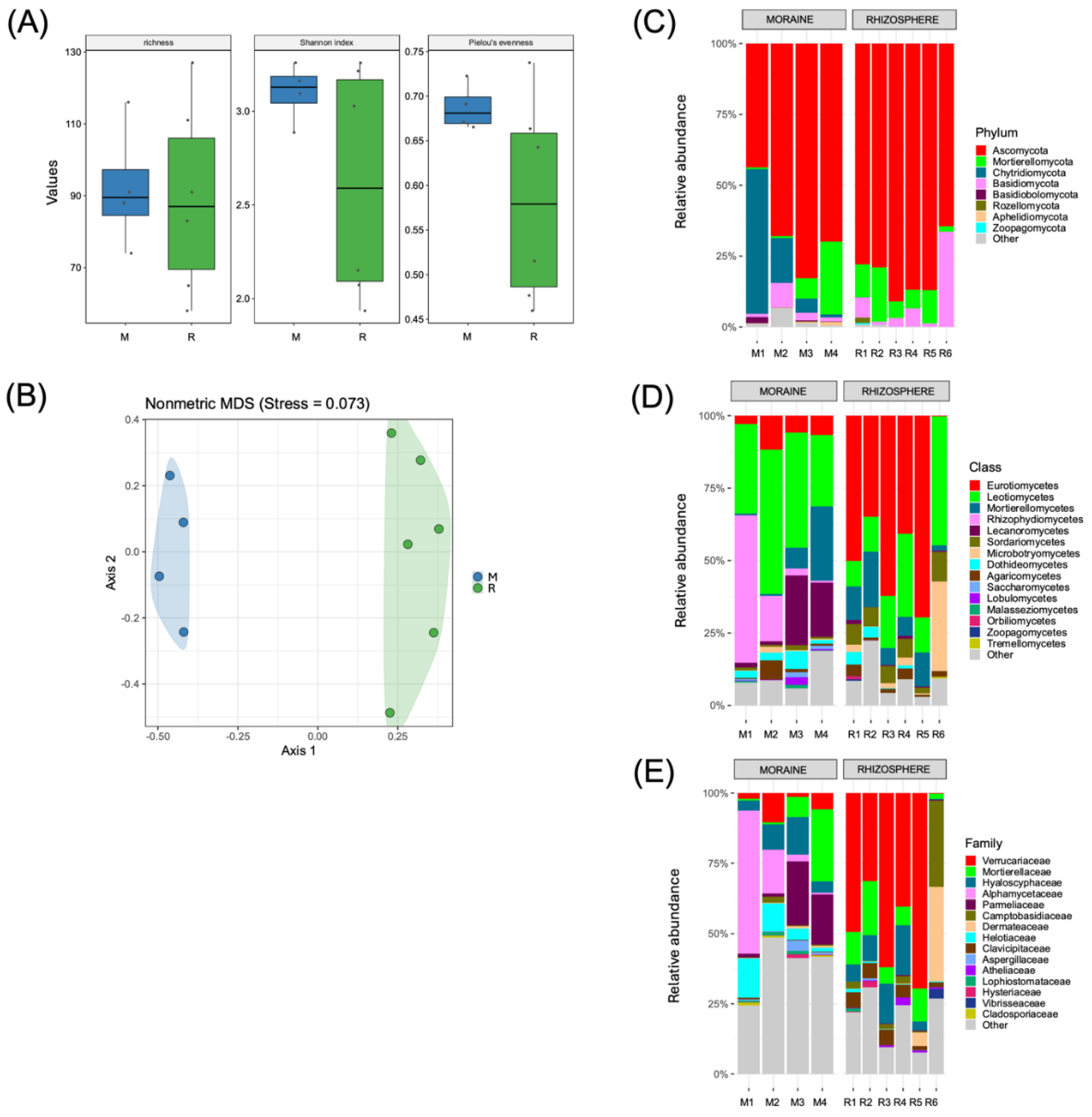

Our analysis did not reveal significant (

p ≤ 0.05) differences in the richness or diversity of the soil fungal communities, with narrower ranges for the M samples (74 to 116 for ASV richness, 2.89 to 3.26 for the Shannon index and 0.67 to 0.72 for the Pielou evenness index) than the R samples (58 to 127 for ASV richness, 1.94 to 3.26 for the Shannon index and 0.46 to 0.74 for the Pielou evenness index) (

Figure 5A). However, regarding the beta diversity, the groups were significantly (

p ≤ 0.05) different on the basis of Bray‒Curtis dissimilarity metric (

Figure 5B). In terms of the structures of the soil fungal communities, the M samples were dominated by the phylum Ascomycota (43.7% to 82.8%), but high relative abundances of the Chytridiomycota (1.1% to 51.1%) and Mortierellomycota (0.6% to 25.7%) phyla were also observed in some of the analyzed samples. The R samples also presented relatively high relative abundances of the phylum Ascomycota (64.5% to 91%), followed by the Mortierellomycota (1.9% to 19.2%) and Basidiomycota (1.1% to 33.6%) phyla (

Figure 5C). Varied structures were observed at the class level, where the classes Leotiomycetes (24.6% to 49.8%), Rhizophydiomycetes (0.7% to 50.9%), Mortierellomycetes (0.6% to 25.7%) and Lecanoromycetes (1.24% to 24.15%) were representative of the M samples. In contrast, the R samples were dominated by members of the class Eurotiomycetes (0.2% to 69.6%), followed by the classes Leotiomycetes (8.8% to 44.5%) and Mortierellomycetes (1.9% to 1.9%) (

Figure 5D). The varied taxonomic diversity was also observed at the family level, where the families Alphamycetaceae, Mortierellaceae and Parmeliaceae were dominant in some M samples, and the families Verrucariaceae, Mortierellaceae and Hyaloscyphaceae were dominant in the R samples.

4. Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into how microbial communities adapt to the environmental changes caused by receding glaciers on King George Island, Maritime Antarctic. By comparing the microbial communities in permafrost, moraine, and D. antarctica rhizosphere soils, we observed clear differences in the diversity, structure, and nutrient availability. The rhizosphere soils presented relatively high nutrient levels and unique microbial groups influenced by plant activity. These findings reinforce the idea that vegetation plays a key role in shaping soil microbiomes and nutrient dynamics in ice-free regions, offering new perspectives on soil formation in polar ecosystems.

In particular, the physicochemical properties of the soil samples collected from the three studied soil types were within the range of values reported in other studies on Antarctic permafrost and moraine [43–45] as well as D. antarctica rhizosphere soils [25,46,47]). Our study also revealed higher contents of nutrients and exchangeable cations but lower pH values in D. antarctica rhizosphere soils than in permafrost and moraine soils. In this sense, it is widely known that vascular plants can release diverse organic compounds as root exudates (e.g., organic acids), which modify the properties of soils, remarkably increasing the availability of nutrients and decreasing the pH [48–50].

Regarding the bacterial community in the D. antarctica rhizosphere soils, our results concerning microbial richness and diversity are similar to those reported in previous studies. However, amplicon metagenomics sequencing in Antarctic samples usually results in Shannon index values within the range of 1.5 to 4 in microbial communities [51], which are lower than the values reported in our study. In this context, Zhang et al. [25] reported average values of 1,551 taxonomic units (OTUs) and a Shannon index of 6 in D. antartica rhizosphere soils. Similarly, Shannon index values ranging from 6 to 7 were found mainly in D. antartica samples by Guajardo-Leiva et al. [52]. However, higher richness values (3,064 OTUs) can also be found in the rhizosphere of D. antarctica samples growing in the Antarctic Peninsula [47]. In the permafrost and moraine soils in our study, relatively low richness (37 to 144 OTUs) and diversity (0.2 to 1.98 for the Shannon index and 0.05 to 0.4 for Pielou’s evenness index) in the bacterial communities were detected near Union Glacier (Heritage Range, Antarctica) [53]. Similarly, lower values of the Shannon index (1 to 3) were also revealed in the soil bacterial communities via 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing in East Antarctica than our results [54].

In addition, our study revealed that members of the phyla Proteobacteria (mainly Gammaproteobacteria and Alphaproteobacteria), Actinobacteria (Actinobacteria), and Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidia) were the most representative bacterial taxa in the bacterial communities of the analyzed soil samples. These phyla are commonly reported as dominant taxa in permafrost, free-ice soils and vascular plant microbiomes in Antarctica [55–58]. Interestingly, members of Acidobacteria were also the dominant class in the D. antarctica rhizosphere. This finding coincides with a study on bacterial communities in diverse Antarctic plant compartments, which exclusively identified members of Acidobacteria in the D. antarctica rhizosphere [25]. Acidobacteria have also been described as part of the rhizosphere microbiome of D. antartica in other studies [52]. Members of the families Sphingomonadaceae and Chitinophagaceae were found to be representative taxa in the soil samples. In this sense, it has been postulated that greater proportions of the families Sphingomonadaceae and Chitinophagaceae can be found in both the early stages of deglaciation and in older moraines [59]. The Chitinophagaceae family has recently been shown to play a crucial role in the adaptation of plants to cold Antarctic conditions [60].

Studies on the archaeal soil communities during deglaciation and plant colonization in ice-free soils are still very limited; however, our results revealed similar richness and diversity levels compared with the average values of richness (51 OTUs) in soils from Vestfold Hills (Eastern Antarctic; [61]) and diversity (Shannon index of 1 to 3) in soils from the Kitezh Lake area (Maritime Antarctic; [62]). Our results also revealed Crenarchaeota (Nitrososphaeria) and Thermoplasmatota (Thermoplasmata) as the dominant archaeal groups in moraine and rhizosphere soils. During glacier recession, studies have described members of the phylum Euryarchaeota as predominant colonizers in young soils, whereas members of Crenarchaeota were mainly dominant in mature soils [63]. Members of Euryarchaeota, Crenarchaeota and Thermoplasmatota have also been reported as dominant archaeal taxa in soils from the Wanda Glacier forefield (Maritime Antarctic; Pessi et al. [18] and Vestfold Hills [61]. Interestingly, Nitrososphaeraceae was the dominant family in both the moraine and rhizosphere samples, indicating the presence of soil ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA), which could contribute to the nitrogen cycle and carbon fixation in these soils. Previous reports have pointed to the ecological significance of archaea in global nitrogen cycling even under extreme conditions, where members of the Nitrosocosmicus genus have been described as prominent ammonia oxidizers in the Arctic [64] and East Antarctica [65]. Recently, Nitrososphaeraceae and Nitrosocosmicus species were reported in Union Glacier soils and West Antarctica, revealing their capacity to inhabit cold and nutrient-limited environments [66]. Our results also highlighted the relative abundance of the Woesearchaeales family in D. antarctica rhizosphere soil samples. The occurrence of members of the Woesearchaeales family has recently been reported in Arctic lakes [67] and microbial mats on Livingston Island (South Shetland Islands) [68]; however, this family has not been reported as an inhabitant of plant rhizospheres thus far, particularly Antarctic vascular plants.

In addition, our results revealed a slightly lower richness in the soil fungal community than the richness reported in samples of soil and rhizosphere soils from vascular plants (D. antarctica and C. quitensis) collected on Antarctic islands, with the number of OTUs ranging from 87 to 211, which were mainly taxonomically assigned as members of Ascomycota, similar to our study [69]. Similarly, similar values of fungal richness were found in soils collected near glacial lakes in Taylor Valley (Antarctic), with a range of OTU numbers from 6 to 108 and a significant percentage (36%) assigned to the phylum Ascomycota [70]. A low diversity of fungi has also been detected in oligotrophic soils of continental Antarctica, including the isolation of several members of Ascomycota, including members of the Leotiomycetes class (Pseudogymnoascus) [71]. Similar to our study, a similar fungal diversity (Shannon index of 2.5 to 3.5) was also reported for soils collected from the South Shetland Islands, where a high percentage (70%) of fungal isolates belong to the phylum Ascomycota and are mainly members of the classes Leotiomycetes (e.g., Pseudogymnoascus, Lambertella and Cadophora) [72]. Interestingly, our study revealed varied diversity at the family level, including among members of the Alphamycetaceae, Mortierellaceae, Parmelaceaceae, Varrucariaceae and Hyaloscyphaceae. Various fungal assemblages, including common (Ascomycota, Basidiomycota and Mortierellomycota) and uncommon (Chytridiomycota, Rozellomycota, Monoblepharomycota, Zoopagomycota and Basidiobolomycota) phyla, have recently been observed in Antarctic soils during deglaciation on James Ross Island (northeast Antarctic Peninsula) [73].

In addition to the differences found in the physicochemical properties of the studied soils, significant differences were also revealed by the beta diversity analysis of the bacterial, archaeal, and fungal communities. In this context, temporal variations in the bacterial community structures in response to environmental changes in Antarctic soils have been demonstrated in several studies [55], including changes in the abundance and diversity of microbial communities that follow the receding snow lines in glaciers, such as for Ecology Glacier [28]. Similarly, studies have shown that deglaciation results in soil moisture, pH and conductivity gradients, leading to an orderly succession of bacterial communities in East Antarctica [43] and plants in the Antarctic Peninsula [44]. It has been reported that soil physical and chemical factors during the deglaciation of Ecology Glacier also influence the taxonomic diversity of cultivated bacteria [74]. Geochemical properties and water contents have also been identified as key drivers influencing the richness and structure of archaeal communities in Antarctic soils (McMurdo Dry Valleys) [62,75]. Soil texture has also been identified as the main parameter affecting the diversity and composition of fungal communities, influencing the retention of water and nutrients and the physicochemical properties of Antarctic soils in Taylor Valley [70]. During the deglaciation process of Collins Glacier (King George Island), it has also been proposed that the distance from the glacier and the contents of phosphorus and clay in the soil can modify the distribution of fungal species, particularly members of the genera Pseudogymnoascus and Pseudeutorium (Leotiomycetes family) [76].

5. Conclusions

This work reveals the two principal soil changes that are associated with the deglaciation process near Ecology Glacier. The analysis of soil physicochemical properties revealed a direct relationship between soil acidification and increased soil nutrient content when ice-free soils were colonized by vascular plant species. In addition, soil microbiome analysis revealed evident alterations in the relative abundances of microbes during deglaciation; specifically, there were significant increases in the bacterial phyla Acidobacteria, Chloroflexi, Gemmatimonadota and Myxococcota as the number of ice-free zones increased, whereas Actinobacteria revealed the opposite effect.

Our findings provide clues concerning how microbial communities may have contributed to soil formation and nutrient cycling during glacial recession events. The distinct microbial patterns observed across the three soil types highlight the complex interactions among microbes, soil properties, and vegetation. These results not only improve our understanding of microbial roles in Antarctic ecosystems but also emphasize the need for further research on how these communities respond to environmental changes. These results are essential for predicting the ecological impacts of climate change in polar regions, and specific microbial groups can be used as environmental markers of deglaciation progress, with a focus on increasing the number of ice-free soils.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.M., F.P.C., J.J.A., V.C. and M.A.J.; formal analysis, D.E.P., V.C. and M.A.J.; data curation, D.E.P.; investigation, D.E.P., A.G., D.L., A.E.M., F.P.C., L.A.B., J.J.A., V.C. and M.A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, D.E.P., V.C. and M.A.J.; writing—review and editing, D.E.P., A.G., A.E.M., F.P.C., L.A.B., J.J.A., V.C. and M.A.J.; funding acquisition, A.E.M., F.P.C., J.J.A., V.C. and M.A.J. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by The Regular Research Team Projects in Science and Technology & Thematic Research Team from The Chilean National Agency for Research and Development (ANID), code ACT210044. Partial support was also provided by The National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development (FONDECYT), Project nos. 1221228 and 1240602 (to J.J.A. and M.A.J.), and by the Millennium Science Initiative Program, code ICN2021_044 (to J.J.A. and V.C.).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Chilean Antarctic Institute (INACH) staff for their support during the Scientific Antarctic Expedition ECA58, which was conducted from December 2021 to March 2022 and for the permit to collect soil samples in an Antarctic specially protected area (ASPA N°128; Permit N°200; INACH).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cowan, D.A.; Makhalanyane, T.P.; Dennis, P.G.; Hopkins, D.W. Microbial ecology and biogeochemistry of continental Antarctic soils. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleine, C.; Albanese, D.; Ray, A.E.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Stajich, J.E.; Williams, T.J.; Larsen, S.; Tringe, S.; Pennacchio, C.; Ferrari, B.C.; et al. Metagenomics untangles potential adaptations of Antarctic endolithic bacteria at the fringe of habitability. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 917, 170290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, A.W.F.; dos Santos, J.A.; Vianna, M.V.; Vieira, J.M.F.; Mallagutti, V.H.; Inforsato, F.J.; Wentzel, L.C.P.; Lario, L.D.; Rodrigues, A.; Pagnocca, F.C.; et al. Cold-adapted enzymes produced by fungi from terrestrial and marine Antarctic environments. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2017, 38, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, K.P.; Mahawar, L.; Rajasabapathy, R.; Rajeshwari, K.; Miceli, C.; Pucciarelli, S. Comprehensive insights on environmental adaptation strategies in Antarctic bacteria and biotechnological applications of cold adapted molecules. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1197797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lemos, E.A.; da Silva, M.B.F.; Coelho, F.S.; Jurelevicius, D.; Seldin, L. The role and potential biotechnological applications of biosurfactants and bioemulsifiers produced by psychrophilic/psychrotolerant bacteria. Polar Biol. 2023, 46, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Montero, K.; Barrientos, L. Advances in antarctic research for antimicrobial discovery: A comprehensive narrative review of bacteria from antarctic environments as potential sources of novel antibiotic compounds against human pathogens and microorganisms of industrial importance. Antibiotics 2018, 7, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peck, L.S.; Convey, P.; Barnes, D.K. Environmental constraints on life histories in Antarctic ecosystems: tempos, timings and predictability. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2006, 81, 75–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Giudice, A.; Poli, A.; Finore, I.; Rizzo, C. Peculiarities of extracellular polymeric substances produced by Antarctic bacteria and their possible applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 2923–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, M.; Bosch, J.; Coclet, C.; Johnson, J.; Lebre, P.; Salawu-Rotimi, A.; Vikram, S.; Makhalanyane, T.; Cowan, D. Microbial Nitrogen Cycling in Antarctic Soils. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peixoto, R.J.; Miranda, K.R.; Lobo, L.A.; Granato, A.; de Carvalho Maalouf, P.; de Jesus, H.E.; Rachid, C.T.; Moraes, S.R.; Dos Santos, H.F.; Peixoto, R.S.; et al. Antarctic strict anaerobic microbiota from Deschampsia antarctica vascular plants rhizosphere reveals high ecology and biotechnology relevance. Extremophiles 2016, 20, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Styczynski, M.; Biegniewski, G.; Decewicz, P.; Rewerski, B.; Debiec-Andrzejewska, K.; Dziewit, L. Application of psychrotolerant antarctic bacteria and their metabolites as efficient plant growth promoting agents. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 772891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansson, J.K.; Hofmockel, K.S. Soil microbiomes and climate change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Raymond, B.; Bracegirdle, T.; Chadès, I.; Fuller, R.A.; Shaw, J.D.; Terauds, A. Climate change drives expansion of Antarctic ice-free habitat. Nature 2017, 547, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, D.A. Climate change and the microbiology of the Antarctic Peninsula region. Sci. Prog. 2008, 91, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abakumov, E.V.; Parnikoza, I.Y.; Zhianski, M.; Yaneva, R.; Lupachev, A.V.; Andreev, M.P.; Vlasov, D.Y.; Riano, J.; Jaramillo, N. Ornithogenic factor of soil formation in Antarctica: A review. Eurasian Soil Sc. 2021, 54, 528–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.P.D.; Veloso, T.G.R.; Costa, M.D.; Souza, J.J.L.L.; Soares, E.M.B.; Gomes, L.C.; Schaefer, C.E.G.R. Microbial successional pattern along a glacier retreat gradient from Byers Peninsula, Maritime Antarctica. Environ. Res. 2024, 241, 117548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, T.C. Micro-terraforming by Antarctic springtails (Hexapoda: Entognatha). J. Nat. Hist. 2016, 50, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessi, I.S.; Osorio-Forero, C.; Gálvez, E.J.C.; Simões, F.L.; Simões, J.C.; Junca, H.; Macedo, A.J. Distinct composition signatures of archaeal and bacterial phylotypes in the Wanda Glacier forefield, Antarctic Peninsula. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2015, 91, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rime, T.; Hartmann, M.; Brunner, I.; Widmer, F.; Zeyer, J.; Frey, B. Vertical distribution of the soil microbiota along a successional gradient in a glacier forefield. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24, 1091–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedov, S.; Zazovskaya, E.; Fedorov-Davydov, D.; Alekseeva, T. Soils of East Antarctic oasis: interplay of organisms and mineral components at microscale. Bol. Soc. Geol. Mex. 2019, 71, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.; Newsham, K.K.; Bardgett, R.D.; Farrar, J.F.; Jones, D.L. Vegetation cover regulates the quantity, quality and temporal dynamics of dissolved organic carbon and nitrogen in Antarctic soils. Polar Biol. 2009, 32, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauze, P.; Wagner, D.; Yang, S.; Spinola, D.; Kühn, P. Influence of prokaryotic microorganisms on initial soil formation along a glacier forefield on King George Island, maritime Antarctica. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prietzel, J.; Prater, I.; Colocho Hurtarte, L.C.; Hrbáček, F.; Klysubun, W.; Mueller, C.W. Site conditions and vegetation determine phosphorus and sulfur speciation in soils of Antarctica. GCA 2019, 246, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslovska, O.; Komplikevych, S.; Danylo, I.; Parnikoza, I.; Hnatush, S. Plant growth-promoting potential of bacterial isolates from the rhizosphere of Deschampsia antarctica. UAJ 2024, 22, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Acuña, J.J.; Inostroza, N.G.; Duran, P.; Mora, M.L.; Sadowsky, M.J.; Jorquera, M.A. Niche differentiation in the composition, predicted function, and co-occurrence networks in bacterial communities associated with antarctic vascular plants. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pętlicki, M.; Sziło, J.; MacDonell, S.; Vivero, S.; Bialik, R.J. Recent Deceleration of the ice elevation change of Ecology Glacier (King George Island, Antarctica). Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bintanja, R. The local surface energy balance of the Ecology Glacier, King George Island, Antarctica: measurements and modelling. Antarct. Sci. 1995, 7, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzesiak, J.; Zdanowski, M.K.; Górniak, D.; Świątecki, A.; Aleksandrzak-Piekarczyk, T.; Szatraj, K.; Sasin-Kurowska, J.; Nieckarz, M. Microbial community changes along the Ecology Glacier ablation zone (King George Island, Antarctica). Polar Biol. 2015, 38, 2069–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobota, I.; Kejna, M.; Araźny, A. Short-term mass changes and retreat of the Ecology and Sphinx glacier system, King George Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Antarct. Sci. 2015, 27, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, S.M.; Nathan, M.V. Soil organic matter. In Recommended Chemical Soil Test Procedures for The North Central Region; Brown, J.R., Ed.; 1998; pp. 53–58. Available online: https://www.canr.msu.edu/uploads/234/68557/rec_chem_soil_test_proce55c.pdf.

- Murphy, J.; Riley, J.P. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal Chim. Acta 1962, 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, B.A. Methods for the Determination of Total Organic Carbon (TOC) in Soils and Sediments; NCEA-C-1282; USEPA: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2002; 25p. [Google Scholar]

- Warncke, D.; Brown, J. Potassium and Other Basic Cations. In Recommended Chemical Soil Test Procedures for the North Central Region; Brown, J.R., Ed.; 1998; pp. 31–33. Available online: https://www.canr.msu.edu/uploads/234/68557/rec_chem_soil_test_proce55c.pdf.

- Loeppert, R.H.; Inskeep, W.P. Iron. In Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 3- Chemical Methods; Sparks, D.L., Page, A.L., Helmke, P.A., Loeppert, R.H., Soltanpour, P.N., Tabatabai, M.A., Johnston, C.T., Sumner, M.E., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America Book Series: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 517–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Lee, C.; Kim, J.; Hwang, S. Group-specific primer and probe sets to detect methanogenic communities using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2005, 89, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herfort, L.; Kim, J.H.; Coolen, M.J.L.; Abbas, B.; Schouten, S.; Herndl, G.; Damsté, J.S.S. Diversity of archaea and detection of crenar-chaeotal amoA genes in the rivers Rhine and Têt. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2009, 55, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.D.; Lee, S.B.; Taylor, J.W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abarenkov, K.; Nilsson, R.H.; Larsson, K.H.; Taylor, A.F.S.; May, T.W.; Frøslev, T.G.; Pawlowska, J.; Lindahl, B.; Põldmaa, K.; Truong, C.; et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification and taxonomic communication of fungi and other eukaryotes: Sequences, taxa and classifications reconsidered. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 52, D791–D797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. Ordination methods, diversity analysis and other functions for community and vegetation ecologists. [CrossRef]

- Bajerski, F.; Wagner, D. Bacterial succession in Antarctic soils of two glacier forefields on Larsemann Hills, East Antarctica. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2013, 85, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boy, J.; Godoy, R.; Shibistova, O.; Boy, D.; McCulloch, R.; de la Fuente, A.A.; Morales, M.A.; Mikutta, R.; Guggenberger, G. Successional patterns along soil development gradients formed by glacier retreat in the Maritime Antarctic, King George Island. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 2016, 89, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, A.; Convey, P.; Hodgson, D.A.; Roger Worland, M.; Ott, S. Soil properties of an Antarctic inland site: implications for ecosystem development. Polar Biol. 2008, 31, 1453–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prekrasna, I.; Pavlovska, M.; Miryuta, N.; Dzhulai, A.; Dykyi, E.; Convey, P.; Kozeretska, I.; Bedernichek, T.; Parnikoza, I. Antarctic hairgrass rhizosphere microbiomes: Microscale effects shape diversity, structure, and function. Microbes Environ. 2022, 37, ME21069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Znój, A.; Gawor, J.; Gromadka, R.; Chwedorzewska, K.J.; Grzesiak, J. Root-associated bacteria community characteristics of antarctic plants: Deschampsia antarctica and Colobanthus quitensis—a Comparison. Microb. Ecol. 2022, 84, 808–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeleke, R.; Nwangburuka, C.; Oboirien, B. Origins, roles and fate of organic acids in soils: A review. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 108, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.L. Organic acids in the rhizosphere – a critical review. Plant Soil 1998, 205, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives-Peris, V.; de Ollas, C.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Pérez-Clemente, R.M. Root exudates: from plant to rhizosphere and beyond. Plant Cell Rep. 2020, 39, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doytchinov, V.V.; Dimov, S.G. Microbial community composition of the Antarctic ecosystems: Review of the bacteria, fungi, and archaea identified through an ngs-based metagenomics approach. Life 2022, 12, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guajardo-Leiva, S.; Alarcón, J.; Gutzwiller, F.; Gallardo-Cerda, J.; Acuña-Rodríguez, I.S.; Molina-Montenegro, M.; Crandall, K.A.; Pérez-Losada, M.; Castro-Nallar, E. Source and acquisition of rhizosphere microbes in Antarctic vascular plants. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 916210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Cha, Q.Q.; Dang, Y.R.; Chen, X.L.; Wang, M.; McMinn, A.; Espina, G.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Blamey, J.M.; Qin, Q.L. Reconstruction of the functional ecosystem in the high light, low temperature Union Glacier region, Antarctica. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, B.; Pushkareva, E. Metagenomics Provides a Deeper Assessment of the Diversity of Bacterial Communities in Polar Soils Than Metabarcoding. Genes 2023, 14, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottos, E.M.; Scarrow, J.W.; Archer, S.D.J.; McDonald, I.R.; Cary, S.C. Bacterial community structures of Antarctic soils. In Antarctic Terrestrial Microbiology; Cowan, D.A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goordial, J.; Davila, A.; Lacelle, D.; Pollard, W.; Marinova, M.M.; Greer, C.W.; DiRuggiero, J.; McKay, C.P.; Whyte, L.G. Nearing the cold-arid limits of microbial life in permafrost of an upper dry valley, Antarctica. ISME J. 2016, 10, 1613–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, E.A.; Gladkov, G.V.; Kimeklis, A.K.; Kichko, A.A.; Karpova, D.V.; Andronov, E.E.; Abakumov, E.V. The structure of the prokaryotic communities of the initial stages of soil formation in Antarctic Peninsula. IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 862, 012056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysak, L.V.; Maksimova, I.A.; Nikitin, D.A.; Ivanova, A.E.; Kudinova, A.G.; Soina, V.S.; Marfenina, O.E. Soil microbial communities of Eastern Antarctica. Moscow Univ. Biol. Sci. Bull. 2018, 73, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pershina, E.V. , Ivanova, E.A.; Abakumov, E.V.; Andronov, E.E. The impacts of deglaciation and human activity on the taxonomic structure of prokaryotic communities in Antarctic soils on King George Island. Antarct. Sci. 2018, 30, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qu, Y.; Teng, X.; Xu, L.; Jin, L.; Xue, H.; Xun, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; et al. Meta-analysis of root-associated bacterial communities of widely distributed native and invasive Poaceae plants in Antarctica. Polar Biol. 2024, 47, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Thibaut, L.M.; Terauds, A.; Raven, M.; Tanaka, M.M.; van Dorst, J.; Wong, S.Y.; Crane, S.; Ferrari, B.C. Lifting the veil on arid-to-hyperarid Antarctic soil microbiomes: a tale of two oases. Microbiome 2020, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wang, N.; Han, W.; Zhang, B.; Zang, J.; Qin, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, T. Soil Geochemical properties influencing the diversity of bacteria and archaea in soils of the Kitezh Lake Area, Antarctica. Biology 2022, 11, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumsteg, A.; Luster, J.; Göransson, H.; Smittenberg, R.H.; Brunner, I.; Bernasconi, S.M.; Zeyer, J.; Frey, B. Bacterial, archaeal and fungal succession in the forefield of a receding glacier. Microb. Ecol. 2012, 63, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.J.E.; Kerou, M.; Zappe, A.; Bittner, R.; Abby, S.S.; Schmidt, H.A.; Pfeifer, K.; Schleper, C. Ammonia oxidation by the arctic terrestrial Thaumarchaeote Candidatus Nitrosocosmicus arcticus is stimulated by increasing temperatures. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, K.; Tanabe, Y.; Fujitake, N.; Kida, M.; Wang, Y.; Hayatsu, M.; Kudoh, S. Ammonia oxidation potentials and ammonia oxidizers of lichen–moss vegetated soils at two ice-free areas in East Antarctica. Microbes Environ. 2020, 35, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arros, P.; Palma, D.; Gálvez-Silva, M.I.; Gaete, A.; Gonzalez, H.; Carrasco, G.; Coche, J.; Perez, I.; Castro-Nallar, E.; Galbán, C.; et al. Life on the edge: Microbial diversity, resistome, and virulome in soils from the union glacier cold desert. Sci. Total Environ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Wang, N.; Zheng, L.; Li, Q.; Wang, L.; Xu, X.; Yin, X. Study of Archaeal Diversity in the Arctic Meltwater Lake Region. Biology 2023, 12, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doytchinov, V.V.; Peykov, S.; Dimov, S.G. Study of the bacterial, fungal, and archaeal communities structures near the Bulgarian Antarctic Research Base “St. Kliment Ohridski” on Livingston Island, Antarctica. Life 2024, 14, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, F.; Newsham, K.K.; Bol, R.; Dungait, J.A.J.; Robinson, C.H. Not poles apart: Antarctic soil fungal communities show similarities to those of the distant Arctic. Ecol. Let. 2016, 19, 495–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canini, F.; Geml, J.; D’Acqui, L.P.; Buzzini, P.; Turchetti, B.; Onofri, S.; Ventura, S.; Zucconi, L. Fungal diversity and functionality are driven by soil texture in Taylor Valley, Antarctica. Fungal Ecol. 2021, 50, 101041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho, V.M.; Gonçalves, V.N.; Santiago, I.F.; Figueredo, H.M.; Vitoreli, G.A.; Schaefer, C.E.; Barbosa, E.C.; Oliveira, J.G.; Alves, T.M.; Zani, C.L.; et al. Diversity and bioprospection of fungal community present in oligotrophic soil of continental Antarctica. Extremophiles 2015, 19, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, P.; Barra, P.J.; Jorquera, M.A.; Viscardi, S.; Fernandez, C.; Paz, C.; Mora, M.L.; Bol, R. Occurrence of soil fungi in Antarctic pristine environments. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, V.N.; Lirio, J.M.; Coria, S.H.; Lopes, F.A.C.; Convey, P.; de Oliveira, F.S.; Carvalho-Silva, M.; Câmara, P.E.A.S.; Rosa, L.H. Soil fungal diversity and ecology assessed using dna metabarcoding along a deglaciated chronosequence at Clearwater Mesa, James Ross Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Biology 2023, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zdanowski, M.K.; Żmuda-Baranowska, M.J.; Borsuk, P.; Świątecki, A.; Górniak, D.; Wolicka, D.; Jankowska, K.M.; Grzesiak, J. Culturable bacteria community development in postglacial soils of Ecology Glacier, King George Island, Antarctica. Polar Biol. 2013, 36, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, I.; Herbold, C.W.; Lee, C.K.; McDonald, I.R.; Barrett, J.E.; Cary, S.C. Influence of soil properties on archaeal diversity and distribution in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 89, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.A.d.; Meyer, E.; Sette, L.D. Fungal community in antarctic soil along the retreating Collins Glacier (Fildes Peninsula, King George Island). Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).