Submitted:

06 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Resilience in Military Personnel

Emotional Intelligence in Military Personnel

The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants, Procedures, and Instruments

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

| R | R2 | Corrected R2 | Cambios estadísticos | Durbin Watson | ||||||

| Standard error of estimate (SE) | Change in R2 |

Change in F |

Sig. of change in F |

|||||||

| Model | .39 | .15 | .15 | 7.94 | .15 | 136.65 | .00 | 1.98 | ||

| Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity | ||||||

| β | Standard error | Beta | ||||||||

| Tolerance | VIF | |||||||||

| .13 | .01 | .39 | 3.32 | .000 | .78 | 1.26 | ||||

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilén, N.; Williams, P.D. Peacekeeping armies: how the politics of peace operations shape military organizations. Int Aff. 2024, 100, 919–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Decree 96/2009, February 6, approving the Royal Ordinances for the Armed Forces. Official State Bulletin, 6 February.

- Flood, A.; Keegan, R.J. Cognitive resilience to psychological stress in military personnel. Front Psychol. 2022, 13, 809003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orak, U.; Kayaalp, A.; Walker, M.H.; Breault, K. Resilience and depression in military service: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). Mil Med. 2022, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, M.M.; Nash, W.P.; Litz, B.T. Post-traumatic stress disorder: review of the Comprehensive Soldier Fitness program. Am J Prev Med. 2013, 44, 507–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInerney, S.A.; Waldrep, E.; Benight, C.C. Resilience enhancing programs in the U.S. military: An exploration of theory and applied practice. Mil Psychol. 2024, 36, 241–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, J.L. Estrategia militar de la OTAN: doctrinas y conceptos estratégicos. Recepción en España. Rev Estud Segur Int. 2022, 8, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puell De La, F. Modernización de las fuerzas armadas durante el reinado de Juan Carlos I. Arauc. 2021, 23, 403–430. [Google Scholar]

- Del Mar, D.D.; Ruíz, A.; Pino, S.; Lazo, T.A.; Pacheco, A.B. La comunicación asertiva en las instituciones educativas militares: una revisión de la literatura científica del 2015-2020. Alpha Centauri. 2021, 2, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, E.; García, M. Benefits of PsyCap training on the wellbeing in military personnel. Psicoth. 2021, 33, 536–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachik, B.; Oakey-Frost, N.; Ganulin, M.L.; Adler, A.B.; Dretsch, M.N.; Cabrera, O.A. Military suicide prevention: The importance of leadership behaviors as an upstream suicide prevention target. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2021, 51, 316–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naifeh, J.A.; Mash, H.B.H.; Stein, M.B.; Vance, M.C.; Aliaga, P.A.; Fullerton, C.S. Sex differences in US Army suicide attempts during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Med Care. 2021, 59, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouweloos-Trines, J.; Te Brake, H.; Sijbrandij, M.; Boelen, P.A.; Brewin, C.R.; Kleber, R.J. A longitudinal evaluation of active outreach after an aeroplane crash: screening for post-traumatic stress disorder and depression and assessment of self-reported treatment needs. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2019, 10, 1554406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Song, J.; Chen, J.; Gan, X.; Li, Y.; Qiu, C. Preventing and mitigating post-traumatic stress: A scoping review of resilience interventions for military personnel in pre deployment. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2024, 17, 2377–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, M.; Norris, D.; Cramm, H.; Richmond, R.; Anderson, G.S. Public safety personnel family resilience: A narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19, 5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, D.; Kim, J. Posttraumatic growth and psychosocial gains from adversities of korean special forces: a consensual qualitative research. Curr Psychol. 2023, 42, 10186–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, D.; Samaranayaka, A.; Richardson, A.; Gardner, D.; Shepherd, D.; Wyeth, E. Factors associated with self-reported health among New Zealand military veterans: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022, 12, e056916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddah, Z.; Negarandeh, R.; Rahimi, S.; Pashaeypoor, S. Challenges of living with veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder from the perspective of spouses: a qualitative content analysis study. BMC Psychiatry. 2024, 24, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrionandia, A.; Ramos-Díaz, E.; Fernández-Lasarte, O. Resilience as a mediator of emotional intelligence and perceived stress: A cross-country study. Front Psychol. 2018, 9, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrei, F.; Mancini, G.; Agostini, F.; Epifanio, M.S.; Piombo, M.A.; Riolo, M. Quality of life and job loss during the COVID-19 pandemic: Mediation by hopelessness and moderation by trait emotional intelligence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilca-Pareja, V.; Luque Ruiz de Somocurcio, A.; Delgado-Morales, R.; Medina Zeballos, L. Emotional Intelligence, resilience, and self-esteem as predictors of satisfaction with life in university students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19, 16548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.; Zapata, I.; Lenz, A.; Ryznar, R.; Nevins, N.; Hoang, T.N. Medical students immersed in a hyper-realistic surgical training environment leads to improved measures of emotional resiliency by both Hardiness and Emotional Intelligence evaluation. Front Psychol. 2020, 11, 569035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goleman, D. Emotional intelligence. Bantam Books; 1995.

- Bar-On, R. The impact of emotional intelligence on health and wellbeing. In: Emotional Intelligence - New Perspectives and Applications. InTech; 2012.

- Hoffman, S.N.; Taylor, C.T.; Campbell-Sills, L.; Thomas, M.L.; Sun, X.M.; Naifeh, J.A. Association between neurocognitive functioning and suicide attempts in U.S. Army Soldiers. J Psychiatr Res. 2022, 145, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candeias, A.A.; Galindo, E.; Rocha, A. Adaptation and psychometric analysis of the Emotional Intelligence View Nowack’s (EIV) questionnaire in the Portuguese context. Psicolog. 2021, 35, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madahi, M.E.; Javidi, N.; Samadzadeh, M. The relationship between emotional intelligence and marital status in sample of college students. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2013, 84, 1317–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casino-García, A.M.; Llopis-Bueno, M.J.; Llinares-Insa, L.I. Emotional intelligence profiles and self-esteem/self-concept: An analysis of relationships in gifted students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goleman, D. El cerebro e inteligencia emocional: nuevos descubrimientos. Ediciones B; 2012.

- Cortellazzo, L.; Bonesso, S.; Gerli, F.; Pizzi, C. Experiences that matter: Unraveling the link between extracurricular activities and emotional and social competencies. Front Psychol. 2021, 12, 659526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, J. NASA resilience and leadership: examining the phenomenon of awe. Front Psychol. 2023, 14, 1158437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Misra, R.; Pathak, D.; Sharma, P. Boosting job satisfaction through emotional intelligence: A study on health care professionals. J Health Manag. 2021, 23, 414–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.L.; Ivcevic, Z.; Moeller, J.; Menges, J.I.; Reiter-Palmon, R.; Brackett, M.A. Gender and emotions at work: Organizational rank has greater emotional benefits for men than women. Sex Rol. 2022, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, N.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. A correlation study of military psychological stress, optimistic intelligence quotient, and emotion regulation of Chinese naval soldiers. Soc Behav Pers. 2022, 50, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H.; Bin Amin, M.; Yusof, M.F. , Islam, M.A.; Afrin, S. Influence of teachers’ emotional intelligence on students’ motivation for academic learning: an empirical study on university students of Bangladesh. Cogent Educ. 2024, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Luo, N.; Bai, R.; Xu, X. The role of empathy and perceived stress in the association between dispositional awe and prosocial behavior in medical students: a moderated mediation model. Educ Psychol. 2024, 44, 358–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirigotis, K. Division of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Department of Psychology, Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce, Kielce, Poland. Emotional intelligence, indirect self-destructiveness and gender. Psychiatr Psychol Klin, 21.

- Corzine, E.; Figley, C.R.; Marks, R.E.; Cannon, C.; Lattone, V.; Weatherly, C. Identifying resilience axioms: Israeli experts on trauma resilience. Traum. 2017, 23, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.C.; Castro, F.; Lee, L.O.; Charney, M.E.; Marx, B.P.; Brailey, K. Military unit support, postdeployment social support, and PTSD symptoms among active duty and National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq. J Anxiety Disord. 2014, 28, 446–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umucu, E.; Ghosh, A.; Castruita, Y.; Yasuoka, M.; Choi, H.; Urkmez, B. The impact of army resilience training on the self-stigma of seeking help in student veterans with and without disabilities. Stigm Healh. 2022, 7, 404–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Choi, B.; Lee, Y.; Kim, K.M.; Kim, D.; Park, T.W. The relationship between posttraumatic embitterment disorder and stress, depression, self-esteem, impulsiveness, and suicidal ideation in Korea soldiers in the local area. J Korean Med Sci. 2023, 38, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekesiene, S.; Smaliukienė, R.; Vaičaitienė, R.; Bagdžiūnienė, D.; Kanapeckaitė, R.; Kapustian, O. Prioritizing competencies for soldier’s mental resilience: an application of integrative fuzzy-trapezoidal decision-making trial and evaluation laboratory in updating training program. Front Psychol. 2023, 14, 1239481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevins, N.A.; Singer-Chang, G.; Dailey, S.F.; Roche, R.; Dong, F.; Peters, S.N. A mixed methods investigation on the relationship between perceived self-Regard, self-efficacy, and commitment to serve among military medical students. Mil Med. 2023, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forouzan, M.; Rawat, S.L. Emotional intelligence, resilience and hardiness among military spouses. Int J Psychol. 2023, 58, 751. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, N.N.; Petrides, K.V.; Hull, L.; Hadi, F. Trait emotional intelligence profiles of professionals in Kuwait. Front Psychol. 2023, 14, 1051558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int J Surg. 2014, 12, 1500–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennie, D. Trial registration: A great idea switches from ignored to irresistible. JAMA, 2004, 292, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagnild, G.M.; Young, H.M. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. J Nurs Meas. 1993, 1, 165–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Gázquez, J.J.; Mercader, I.; Molero, M.M. Brief Emotional Intelligence Inventory for senior citizens (EQ-i-M20). Psicoth. 2014, 26, 524–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-On, R.; Parker, J.D.A. Emotional Quotient Inventory: Youth Version (EQ-i:YV): Technical manual. Multi Health Systems; 2000.

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychom. 1951, 16, l297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Cui, Y.; Babenko, O. International consistency: Do we really know what it is and how to assess it? J of Psy Behav Scienc. 2014, 2, 205–20. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011, 2, 53–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992, 112, 155–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Erlbaum; 1988.

- Yoo, S.K.; Cotton, S.L.; Sofotasios, P.C.; Matthaiou, M.; Valkama, M.; Karagiannidis, G.K. The fisher–Snedecor $\mathcal F$ distribution: A simple and accurate composite fading model. IEEE Commun Lett. 2017, 21, 1661–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero, M.M.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Soriano, J.G.; Tortosa, B.M.; Oropesa, N.F.; Simón, M.M. Personality and job creativity in relation to engagement in nursing. An Psicol. 2020, 36, 533–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0, 2016.

- Kerry, A.; Sudom, K.A.; Lee, J.E.C. A Decade of longitudinal resilience research in the military across the technical cooperation program’s five nations. Res Militaris. 2016, 6, 16–7. [Google Scholar]

- Niederhauser, M.; Zueger, R.; Sefidan, S.; Annen, H.; Brand, S.; Sadeghi-Bahmani, D. Does training motivation influence resilience training outcome on chronic stress? Results from an interventional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19, 6179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Women | Men | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | |||||||

| 91 | 12.3 | 648 | 87.7 | |||||||

| n | % | |||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||

| 18-25 | 84 | 11.4 | ||||||||

| 26-35 | 410 | 55.5 | ||||||||

| 36-45 | 201 | 27.2 | ||||||||

| 46-55 | 38 | 5.2 | ||||||||

| 56-65 | 5 | 0.6 | ||||||||

| >65 | 1 | 0.1 | ||||||||

| Military scale | ||||||||||

| Officers | 36 | 4.9 | ||||||||

| Non-Commissioned Officers | 143 | 19.4 | ||||||||

| MPTM | 560 | 75.8 | ||||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Single | 294 | 39.8 | ||||||||

| Married | 387 | 52.4 | ||||||||

| Separated/divorced | 44 | 5.9 | ||||||||

| Widower | 14 | 1.9 | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Intrapersonal | 1 | ||||||||

| Interpersonal | .274* | 1 | |||||||

| Stress Management | .07* | .00 | 1 | ||||||

| Adaptability | .29** | .34** | .13** | 1 | |||||

| General Mood | .29** | .32** | .33** | .40** | 1 | ||||

| Emotional Intelligence (Global) | .63** | .61** | .46** | .71** | .73** | 1 | |||

| Factor 1 (Resilience) | .19** | .31** | .21** | .30** | .43** | .45** | 1 | ||

| Factor 2 (Resilience) | .16** | .26** | .21** | .27** | .42** | .41** | .82** | 1 | |

| Resilience (Gobal) | .13** | .28** | .18** | .27** | .39** | .39** | .91** | .85** | 1 |

| M | 10.54 | 11.06 | 12.31 | 11.52 | 12.75 | 58.19 | 89.65 | 42.32 | 132.15 |

| DT | 2.95 | 2.63 | 2.51 | 2.99 | 2.52 | 8.64 | 15.92 | 7.36 | 24.68 |

| n | M | SD | t | p | d | ||

| Factor 1 Resilience |

Man | 648 | 89.79 | 15.69 | .67 | .501 | .07 |

| Woman | 91 | 88.59 | 17.56 | ||||

| Factor 2 Resilience |

Man | 648 | 42.44 | 7.27 | 1.16 | 1.16 | .12 |

| Woman | 91 | 41.48 | 7.98 | ||||

| Resilience (Global) | Man | 648 | 132.31 | 24.45 | .46 | .642 | .05 |

| Woman | 91 | 131.02 | 26.41 | ||||

| EI (Intrapersonal) | Man | 648 | 10.48 | 2.99 | -1.48 | .138 | .17 |

| Woman | 91 | 10.97 | 2.59 | ||||

| EI (Interpersonal) | Man | 648 | 11.03 | 2.39 | -1.02 | .306 | .12 |

| Woman | 91 | 11.33 | 3.94 | ||||

| EI (Stress Management) | Man | 648 | 12.41 | 2.48 | 2.85** | .004 | .31 |

| Woman | 91 | 11.61 | 2.63 | ||||

| IE (Adaptability) | Man | 648 | 11.59 | 3.08 | 1.59 | .112 | .20 |

| Woman | 91 | 11.05 | 2.22 | ||||

| EI (General Mood) | Man | 648 | 12.89 | 2.49 | 2.78** | .005 | .32 |

| Woman | 91 | 12.07 | 2.63 | ||||

| EI (Global) | Man | 648 | 58.36 | 8.59 | 1.36 | .171 | .15 |

| Woman | 91 | 57.03 | 8.89 |

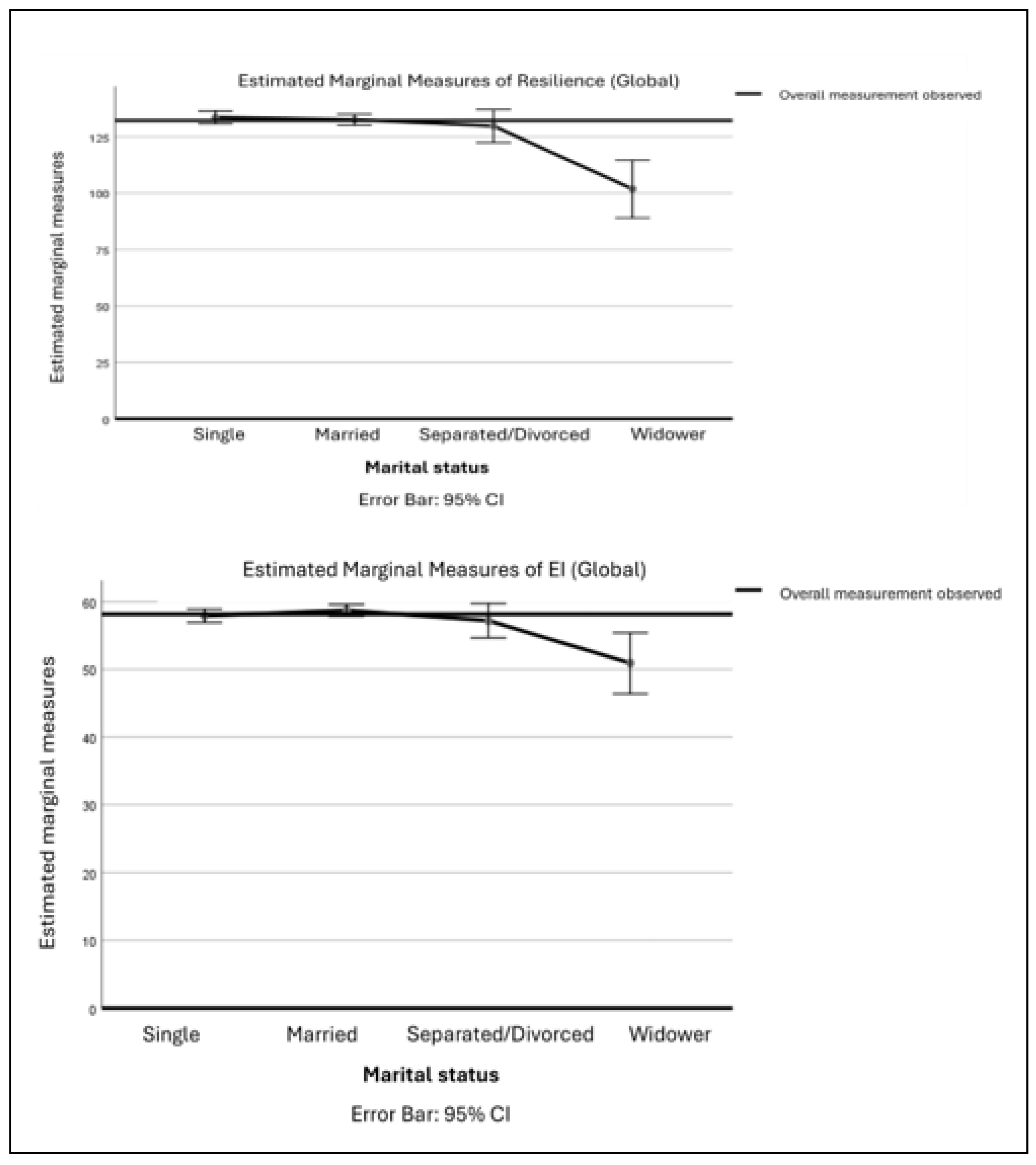

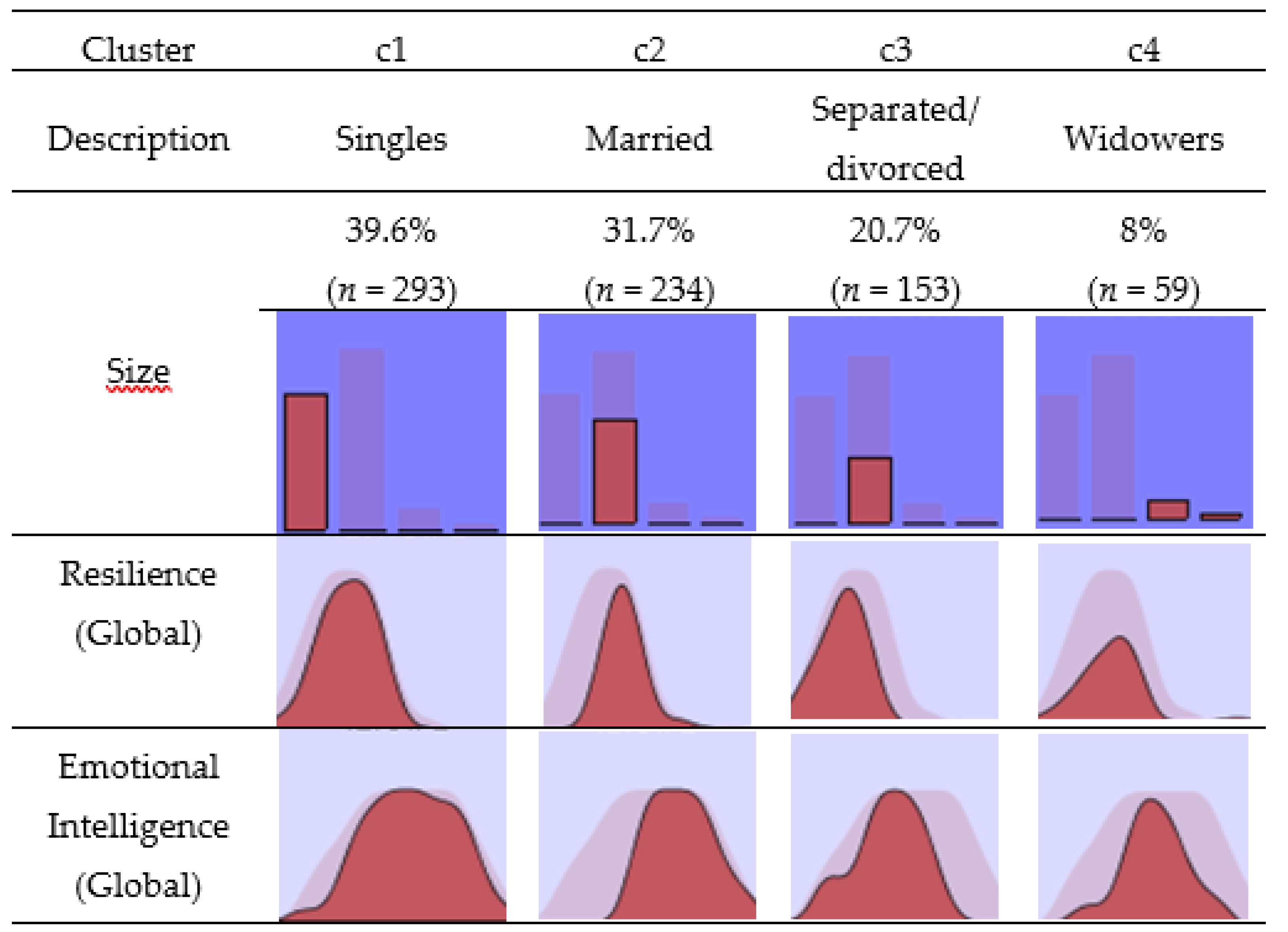

| Marital status | n | M | SD | MANOVA | Post hoc contrasts | |||

| F | p | η2 | ||||||

| Factor 1 Resilience |

g1 | 294 | 90.33 | 14.80 | 8.09 | .01 | .030 | │g1<g2││g1<g3│ │g1<g4│***│g2<g3│ │g2>g4│***│g3>g4│*** |

| g2 | 387 | 90.01 | 15.94 | |||||

| g3 | 44 | 88.32 | 16.86 | |||||

| g4 | 14 | 68.43 | 15.92 | |||||

| Factor 2 Resilience |

g1 | 294 | 42.85 | 6.51 | 13.45 | .01 | .050 | │g1>g2││g1>g3│ │g1>g4│***│g2>g3│ │g2>g4│***│g3>g4│*** |

| g2 | 387 | 42.46 | 7.56 | |||||

| g3 | 44 | 41.39 | 7.25 | |||||

| g4 | 14 | 30.50 | 9.55 | |||||

| Resilience (Global) | g1 | 294 | 133.52 | 23.76 | 7.73 | .01 | .030 | │g1>g2││g1>g3│ │g1>g4│***│g2>g3│ │g2>g4│***│g3>g4│*** |

| g2 | 387 | 132.48 | 24.86 | |||||

| g3 | 44 | 129.70 | 22.81 | |||||

| g4 | 14 | 101.79 | 31.55 | |||||

| EI (Intrapersonal) | g1 | 294 | 10.47 | 3.12 | .33 | .800 | .001 | │g1<g2││g1<g3│ │g1>g4││g2<g3│ │g2>g4 │ │g3>g4│ |

| g2 | 387 | 10.58 | 2.89 | |||||

| g3 | 44 | 10.80 | 2.28 | |||||

| g4 | 14 | 10.00 | 2.85 | |||||

| EI (Interpersonal) | g1 | 294 | 11.01 | 2.09 | 2.00 | .112 | .008 | │g1<g2││g1<g3│ │g1>g4││g2>g3│ │g2>g4 │ │g3>g4│ |

| g2 | 387 | 11.18 | 3.00 | |||||

| g3 | 44 | 10.91 | 1.89 | |||||

| g4 | 14 | 9.50 | 3.50 | |||||

| EI (Stress Management) |

g1 | 294 | 12.35 | 2.47 | 1.42 | .235 | .005 | │g1<g2││g1>g3│ │g1>g4││g2>g3│ │g2>g4 │ │g3<g4│ |

| g2 | 387 | 12.38 | 2.53 | |||||

| g3 | 44 | 11.61 | 2.40 | |||||

| g4 | 14 | 11.85 | 3.05 | |||||

| IE (Adaptability) | g1 | 294 | 11.43 | 3.39 | 3.21 | .022 | .012 | │g1<g2││g1<g3│* │g1<g4│* │g2>g3│ │g2>g4 │** │g3>g4│ |

| g2 | 387 | 11.67 | 2.72 | |||||

| g3 | 44 | 11.52 | 2.02 | |||||

| g4 | 14 | 9.21 | 3.33 | |||||

| EI (General Mood) |

g1 | 294 | 12.67 | 2.37 | 5.41 | .001 | .021 | │g1<g2││g1>g3│*** │g1>g4││g2>g3│ │g2>g4 │***│g3>g4│ |

| g2 | 387 | 12.94 | 2.52 | |||||

| g3 | 44 | 12.39 | 2.38 | |||||

| g4 | 14 | 10.36 | 4.37 | |||||

| EI (Global) |

g1 | 294 | 57.94 | 8.62 | 4.17 | .006 | .016 | │g1<g2│**│g1>g3│ │g1>g4│** │g2>g3│ │g2>g4 │*** │ g3>g4│ |

| g2 | 387 | 58.76 | 8.58 | |||||

| g3 | 44 | 57.23 | 7.10 | |||||

| g4 | 14 | 50.93 | 11.59 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).