Introduction

Chest pain is a significant reason for emergency department (ED) visits, as it is the second leading cause of adults visiting the ED in the US [

1]. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is typically ruled in or out through serial cardiac enzymes and electrocardiograms

[2]. Once ACS has been ruled out, patients are typically risk-stratified into low, intermediate, and high-risk categories. Multiple studies have proven the accuracy of risk assessment scoring systems [

3]

. Healthcare system policymakers introduced hospital chest pain observation units to admit patients within the intermediate and high-risk categories for an ischemic evaluation [

4].

A study that used a national database found that there were 42.5 million ED visits for chest pain in the US from 2006 to 2016. Furthermore, visit rates per 100,000 persons increased by 37% between 2006 and 2016 [

5]. Providers utilized different approaches to manage chest pain observation cases. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) released guidelines in 2021 that guide evaluating this population of patients. ACC/AHA patient-centric algorithms for acute chest pain incorporate history, physical exam, and troponin levels for risk stratification to direct testing choices [

6]. The advancement of various coronary disease and ACS diagnostic methods provides more accuracy in identifying underlying coronary artery disease, even with atypical presentations. However, that led to problems stemming from excessive test ordering with inappropriate resource utilization. One study estimated an annual cost of

$501 million and 491 future cases of cancer attributed to inappropriate testing [

7]. Julie C. Will et al. reported a doubling in the rates of stress testing during the periods from 1999-2002 and 2003-2006 [

8]. The rates remain high despite campaigns by professional societies such as Choosing Wisely to reduce over-testing. Between 2005 and 2012, Kini V et al. reported that using other modalities offset the 14.9% decrease in nuclear single-photon emission computed tomography [

9].

Methods

Setting:

The study location was a tertiary referral center with a 691-bed capacity, designated as a university-level academic center in central New Jersey.

Participants

This retrospective study included adult patients aged 18 years or above who presented to a tertiary care facility in New Jersey, USA ED, with a chief complaint of chest pain. We retrospectively reviewed charts of patients who visited the ED between November 2022 and December 2022.

We excluded patients whose presentation was consistent with ACS, including those with positive troponins and an ACS diagnosis based on Electrocardiogram (EKG) criteria (

Figure 1).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was quantifying the utilization of the HEART score risk stratification tool in patients admitted for chest pain evaluation.

The secondary outcome included identifying the diagnostic testing used to evaluate those patients and the outcomes of those tests.

Study design:

We retrieved patient data including date of presentation, age, gender, and past medical history as follows: Hypertension (HTN), Hyperlipidemia (HLD), Smoking history, obesity based on BMI more than 30 kg/m2, history of coronary artery disease (CAD), history of myocardial infarction (MI), history of peripheral artery disease (PAD), history of cerebrovascular disease (CVA), history of transient ischemic attack (TIA), Chronic kidney disease (CKD), End stage renal disease (ESRD), and if the patient is on dialysis or not (HD).

We reviewed the past surgical history for Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), history of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), or heart transplant).

We reviewed family history for premature CAD (male parent or sibling < 55 years old, female < 65 years old) and if there was a sudden cardiac death (SCD).

We verified if the patient had undergone any ischemic evaluation before the index presentation. The type of ischemic evaluation, whether within a year from the presentation or older and the test results were all identified. The types of ischemic evaluation included stress testing or Left heart catheter (LHC). If performed, we inquired about the timing of the patient's cardiac computed tomography angiogram (CCTA) and whether it was conducted within a year, between one and two years, or over two years before the presentation.

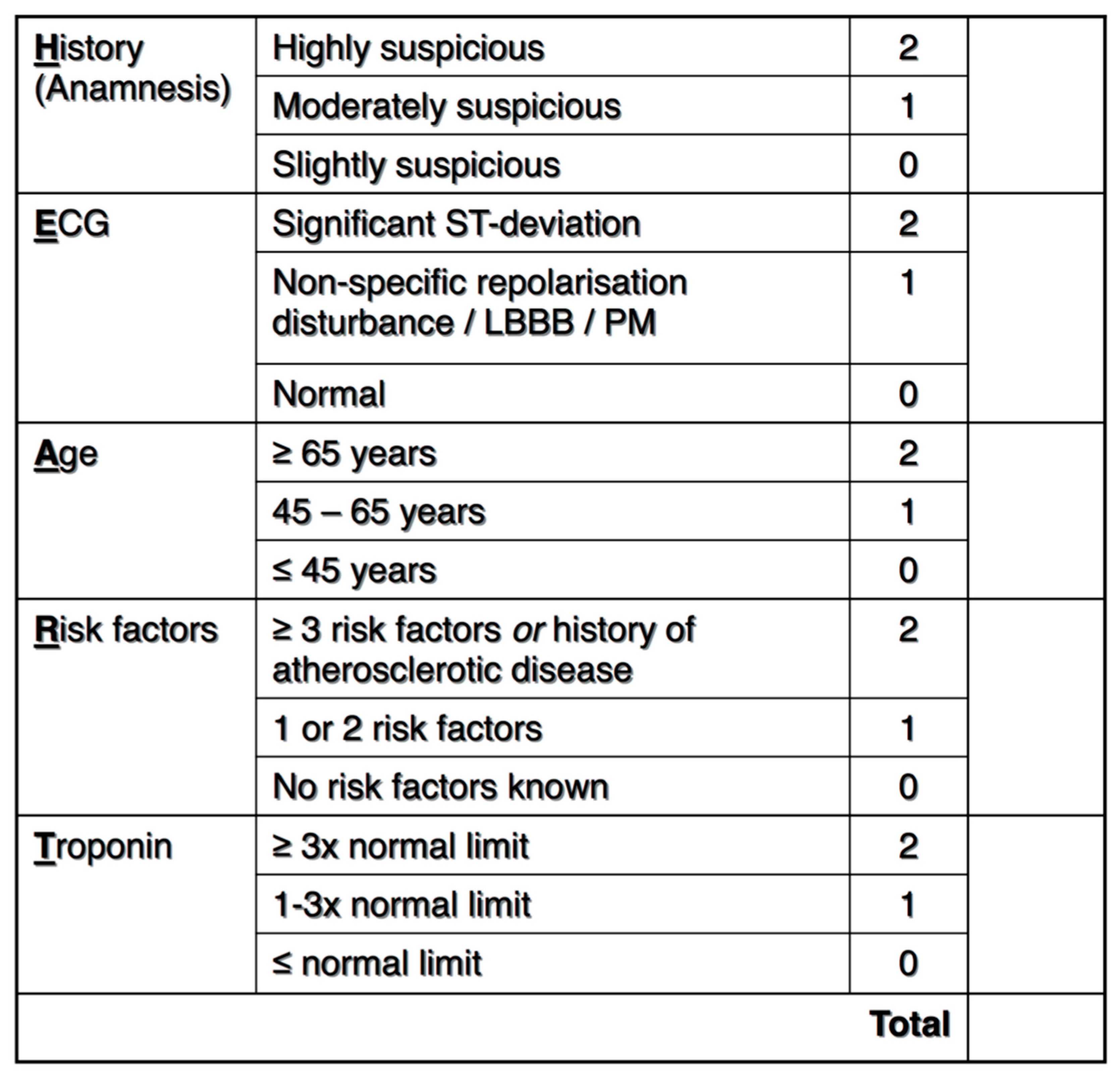

The patients were risk stratified before undergoing any testing using the HEART score (

Figure 2 HEART score) [

3]. The HEART score was independently calculated regardless of whether it was documented in the chart.

We evaluated the chart for diagnostic testing performed while the patient was admitted. Testing included any stress testing, LHC, or CCTA. The outcome of any diagnostic testing and all therapeutic interventions were recorded. Disposition, mortality, and length of stay were also evaluated.

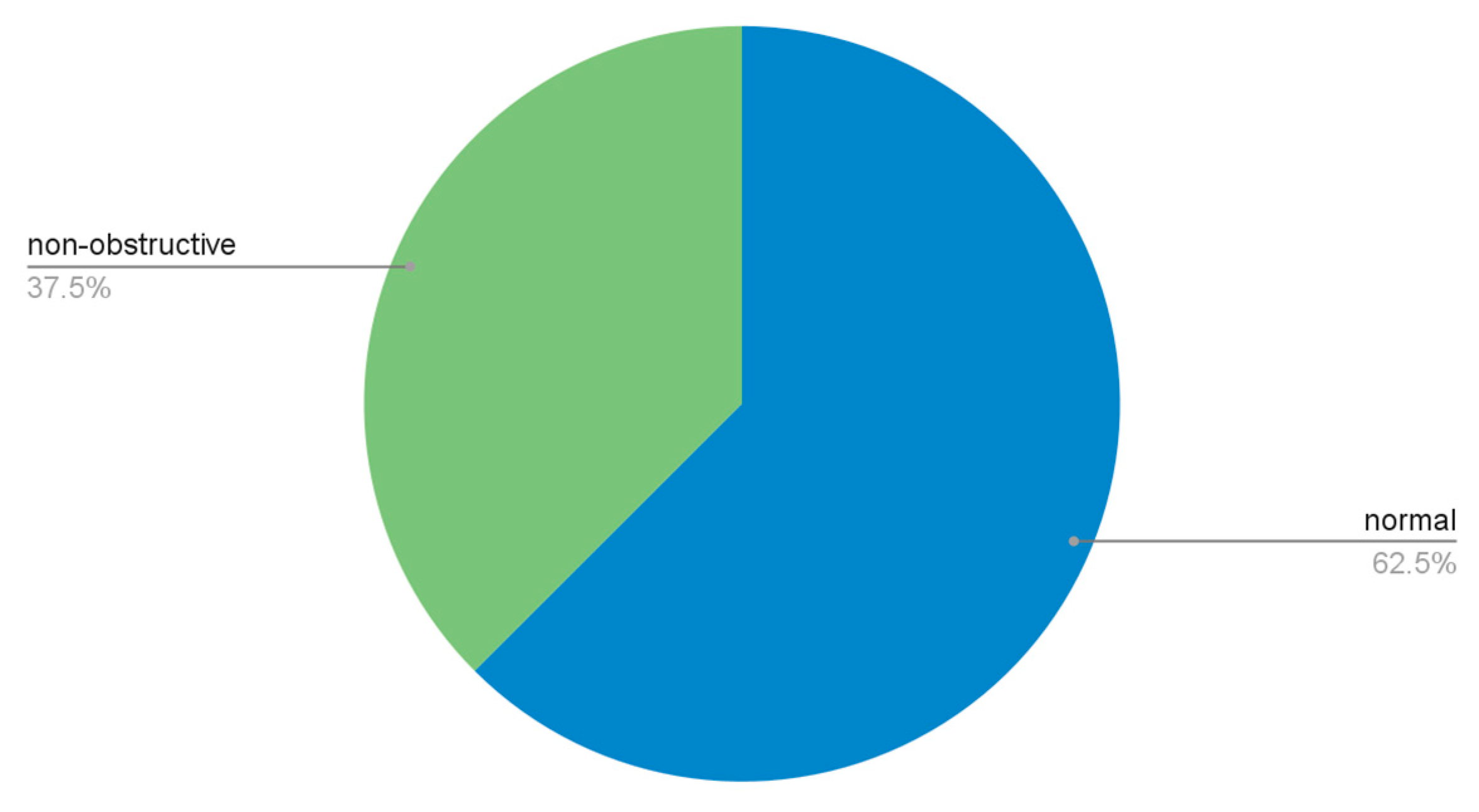

Patients who had one positive and one negative ischemic test were not considered to have a negative ischemic evaluation. We reported a negative LHC if it was normal or non-obstructive and negative stress when it was normal. A mildly abnormal stress test was considered positive.

The study was conducted under the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [

8]. We adhered to the observational cohort guideline.

Our organization's Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed the study protocol. Due to the study's retrospective nature, it provided patients’ consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) waivers (Study ID: Pro2022-0347). The study was conducted following Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and the Declaration of Helsinki [

10].

Variables and data sources:

Clinical information was obtained from patients' electronic medical records (EMRs) in the Epic system (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI). All data were collected and validated by physicians through a manual chart review. Data collected included patient demographics, comorbidities, cardiovascular risk factors, physical examination findings, home medications, imaging findings, EKGs, and telemetry strips.

Sample size calculation:

We intended to include all the patients admitted to our institution during the study period.

Statistical Analysis:

Shapiro–Wilk test and histograms were used to examine the normality of continuous variables. Categorical variables were described as frequency and percentages. We described continuous variables as means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), as appropriate. We used the chi-square test to compare categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney-U test to compare continuous non-parametric variables. We used the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with a two-way mixed model for absolute agreement to assess the consistency between the reported heart scores and those independently calculated. We performed all analyses using IBM SPSS statistics version 25.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). We used an alpha value (p) of 0.05 to ascertain statistical significance.

Results

We identified 550 patients, and 342 patients met the inclusion criteria. The most common reason for exclusion was insufficient data in the EMR, such as only one troponin and unclear duration of chest pain (

Figure 1). Eleven patients had a negative ischemic eval within one year; five patients were admitted (under observation or inpatient status). A prior ischemic evaluation was documented in 40.9% of patients (n=140), including 16.6% (n=57) of patients with ischemic testing performed within the past year. The median age of participants was 54 years (IQR 42-65), with 54.7% being females (n=187). The most common forms of prior ischemic evaluation were a stress test (18.4% of the total included sample, n=63) and LHC (18.4%, n=63), followed by coronary CTA (4.1%, n=14).

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the study participants

Utilization of Heart Score in Disposition:

Of the 342 patients, 49.1% (n=168) were discharged home from the ED, 46.5% (n=159) were admitted to the hospital (under observation or inpatient status), and 4.4% (n=15) left the hospital against medical advice. Physicians documented a Heart score in 24.6% of the patients (n=84), and all included patients' charts were used to calculate the Heart scores independently. For the 84 patients with reported Heart scores, there was a good agreement between the reported and the calculated scores (ICC 0.879, 95% CI 0.813-0.921). The calculated Heart score was higher in patients admitted to the hospital than those who were discharged from the ED [4 (IQR 3-5) versus 1.5 (IQR 1-3)]. Chart review demonstrated that 35.8% (n=57) of admitted patients had a Heart score of 3 or less, with 62 patients (40% of all admitted patients) being admitted despite having both a low HEART score (< 3) or a negative ischemic evaluation within the preceding year.

Inpatient Workup:

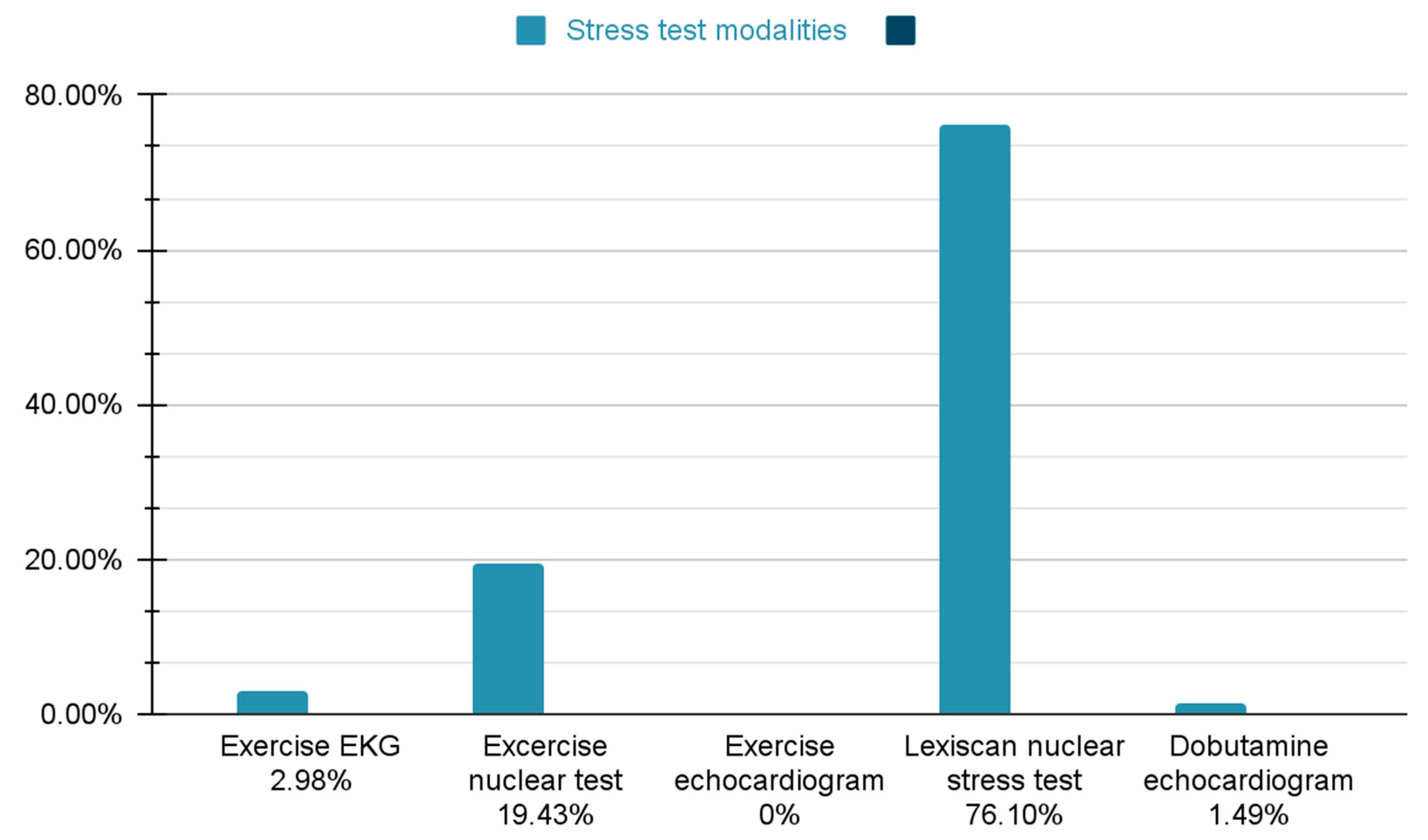

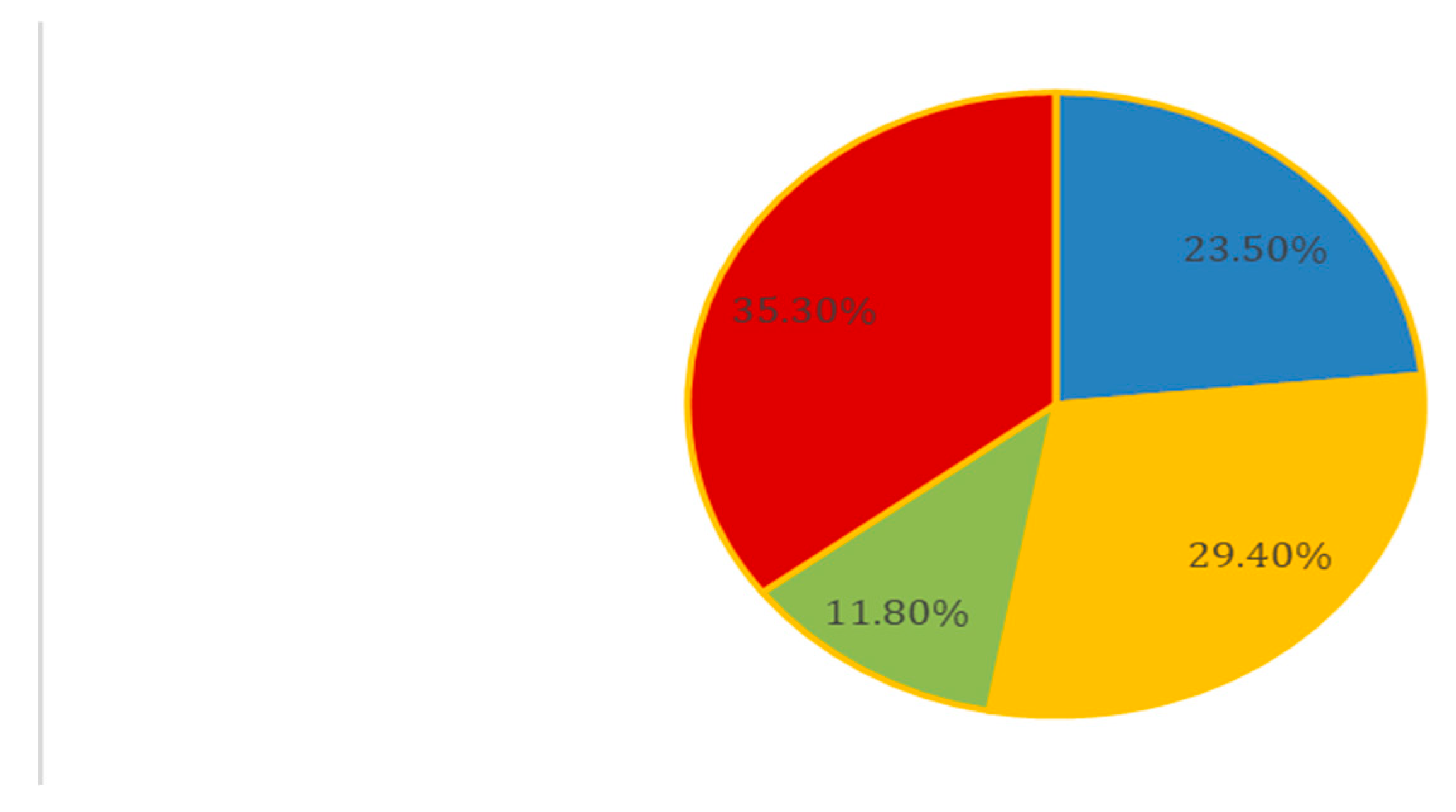

Of the admitted patients, 52.2% (n=82) went on to have an inpatient ischemic workup during that admission. This group was stratified into testing modules, with stress testing as the most common form of inpatient workup (69.5%, n=57), followed by LHC (20.7%, n=17), then CCTA (9.75%, n=8). Stress testing included different modalities (

Figure 3).

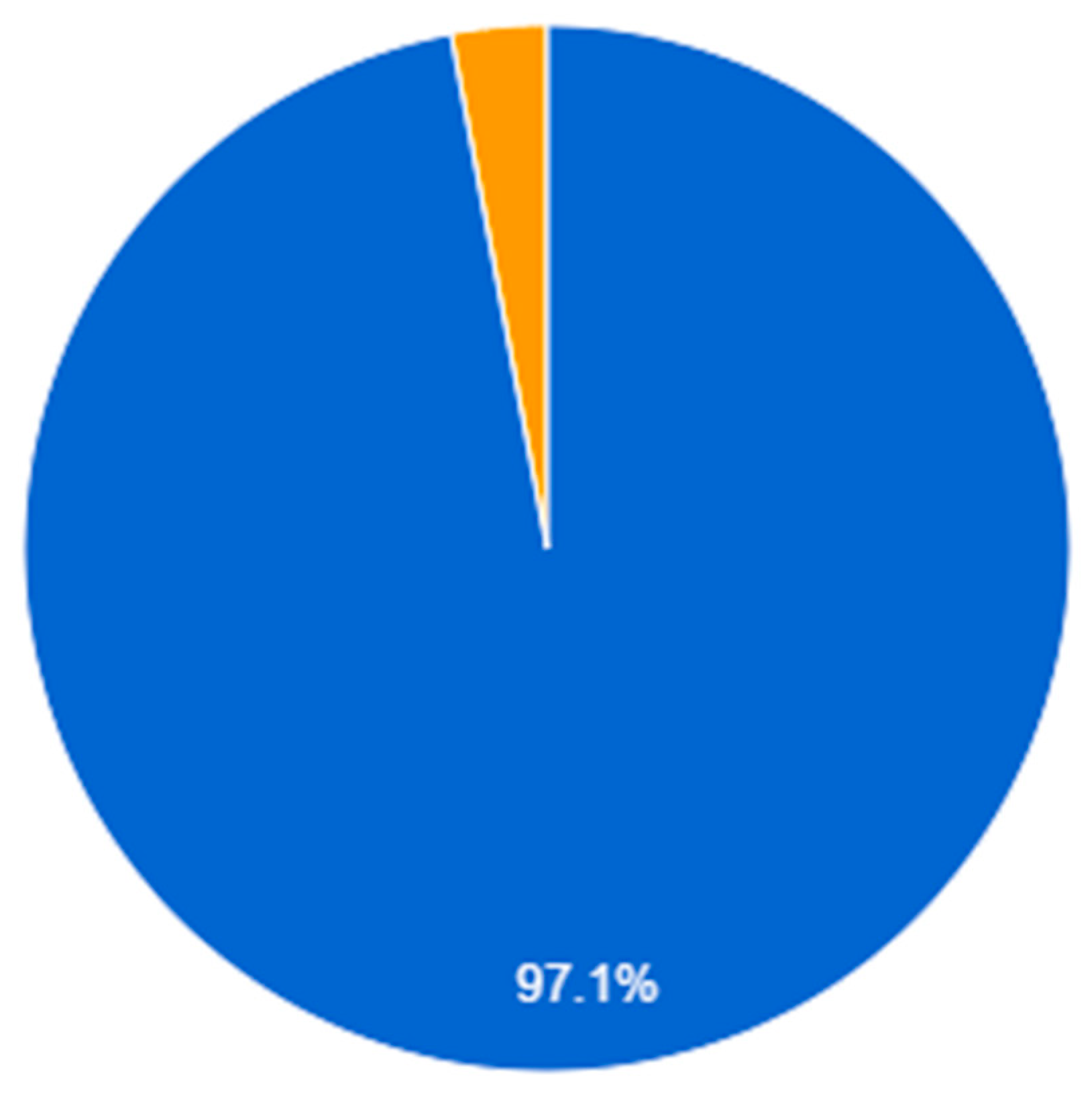

Of the patients with inpatient workups, 31.7% (n=26) had a Heart score of 3 or less, and 15.9% (n=13) had an ischemic evaluation within the preceding year. Only one patient with an inpatient ischemic workup had a positive stress test (

Figure 4). LHC and CCTA results are also shown in (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

Safety data:

Two patients underwent inpatient CABG, and six patients underwent inpatient PCI. Of the patients discharged home from the ER, only 6% (n=10) were discharged with a plan for outpatient stress testing, and no patient had a referral to a cardiologist documented in their charts.

Cost data:

75% of patients had a length of stay of at least one day. The hospital cost for 24 hours of observation is approximately $9600.

Discussion

As chest pain is one of the most common etiologies for which patients seek medical attention, the American College of Cardiology established guidelines for evaluating acute or stable chest pain in the outpatient and emergency rooms [

6]. Such guidelines are established to expedite assessing and managing patients exhibiting clinically significant chest pain. These guidelines consider CAD risk factors and prior ischemic testing (functional or anatomic) in conjunction with clinical and objective testing tools [

6]. The HEART score is one scoring pathway to risk stratifying patients presenting to the emergency room. Six-week major adverse cardiac events (MACE) occurred in (1.7%) of low-score patients (0-3), (16.6%) of the intermediate score (4-6), and (50.1%) of high scores (7-10) [

3]. Other diagnostic modalities include the TIMI score (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) and the HFA/CSANZ (Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand) rule [

11]. Since chest pain is such a common presenting complaint to the ED, we would expect a high cost on the national level, which would reach over

$3 billion in hospital costs per year. Yet, it is one of the reasons for the presentation to the ED with the lowest overall mortality rate [

11]. Inpatient admissions declined from ED visits, with a decline in aggregate admission costs and an increase in mean admission costs [

5]. That means there is a trend to reduce admission of chest pain cases to the hospital despite the increase in visit rates to US ED all over the country [

5].

As symptoms related to acute coronary syndrome and cardiovascular disease remain one of the most common reasons for emergency room visits and hospitalizations in the United States, clinical decision pathways and clinical practice guidelines have been established by the AHA and ACC to minimize unnecessary testing in low-risk populations and identify those most likely to benefit from additional testing [

6]. Researchers evaluate ED chest pain observation units' performance to assess clinical safety and cost efficiency. Continuing efforts are to utilize these units under the updated guidelines to manage chest pain cases effectively. More patients might benefit from these observation units, which would reduce costs and length of stay [

12]. ED physicians should consider prior testing and integrate it with the patient's risk profile to decide how necessary it is to repeat ischemic testing [

13]. There is a recommendation to use EKG stress testing as the first line for those patients. However, there is excessive utilization of radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging, which adds more financial burden on the healthcare system and more radiation exposure to patients. Researchers noted that teaching hospitals use radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging less often than non-teaching hospitals [

14]. Physicians use Heart scores to help stratify patient risks. A low HEART score provides high sensitivity and negative predictive value for predicting major adverse cardiac events [

15].

Our study included patients with significant comorbidities like hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and smoking. More than 40% of our study sample patients had a prior ischemic evaluation, and more than 16% had an ischemic review performed within 1 year of admission. The study's results also showed that utilization of heart score was only performed in 24.6% of patients, and 35.8% of patients were admitted with a low-risk HEART score documented (< 3). Of the patients admitted, more than half had an ischemic workup in the inpatient setting, and the majority had resulted in negative non-invasive workup during their admission.

This yields a significant area of improvement for our institution, where a closer evaluation of AHA/ACC guidelines can be performed and practiced to achieve more cost-effective care. With 75% of patients included in the study having an average length of stay of at least 1 day, the resulting cost accrued for admission was more than $1,500,000 for two months at our hospital. Continued improvement in implementing the protocol-driven risk stratification for chest pain admissions may result in tremendous healthcare cost reductions, as evidenced by our single-center experience during this two-month study period.

In the end, different factors affect the ED physician, hospitalist, or cardiologist's decision to admit or discharge patients presenting with chest pain, such as the reliability of cardiology follow-up. Our study has no clear documentation of how the ED referred the patient to a follow-up visit, including time and place. Only 6% of patients in our study had clear documentation of a scheduled plan for outpatient stress testing if they didn’t do it in the hospital. Although documentation might not be accurate here and might have missed many follow-up details, it helps improve communication and compliance between the patient and the healthcare system. ED physicians are responsible for ensuring patient safety upon discharge, which may result in significant inpatient over-testing [

16,

17,

18,

19].

Study Limitations

There are some limitations to the study. As this is a retrospective observational study, the data collected is limited to that available via electronic medical records. Decisions made regarding patient-centered care that may not have been documented or accessible would not have been considered within this study's scope. Moreover, the sample included in our study was of limited size and chronological timeline, which may not represent the population admitted to our institution.

Conclusions

This single-center, retrospective analysis of care delivery for non-ACS (acute coronary syndrome) chest pain patients demonstrates the infrequent utilization of validated chest pain scoring tools for risk stratification and the over-reliance on inpatient ischemic testing. This results in increased length of stay and costs for the institution and healthcare system. Furthermore, ischemic testing is often repeated despite recent testing within the past year. We also found that inpatient non-invasive ischemic testing in non-ACS chest pain patients is typically negative and thus would be unlikely to change their clinical course. This study serves not only as a quality improvement initiative within our institution but as a recommendation for others to explore similar data within their institutions and as a reminder of the importance of utilizing validated clinical pathways to streamline clinical care and reduce healthcare costs.

Conflict of interest

No conflict to disclose.

Abbreviation List

ED Emergency department

ACS Acute coronary syndrome

ACC American College of Cardiology

AHA American Heart Association

HTN Hypertension

HLD Hyperlipidemia

EKG Electrocardiogram

CAD Coronary artery disease

MI Myocardial infarction

PAD Peripheral artery disease

CVA Cerebrovascular disease

TIA Transient ischemic attack

CKD Chronic kidney disease

ESRD End-stage renal disease

HD Hemodialysis

LHC Left heart catheter

CCTA Cardiac computed tomography angiogram

CABG Coronary artery bypass graft

PCI Percutaneous coronary intervention

SCD Sudden cardiac death

STROBE Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

IRB Institutional Review Board

IQR Interquartile ranges

ICC Intraclass correlation coefficient

HIPAA Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

TIMI Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction

HFA/CSANZ Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand

References

- Sweeney M, Bleeze G, Storey S, Cairns A, Taylor A, Holmes C, et al. The impact of an acute chest pain pathway on the investigation and management of cardiac chest pain. Future Healthc J. 2020 Feb;7(1):53–9.

- Penumetsa SC, Mallidi J, Friderici JL, Hiser W, Rothberg MB. Outcomes of patients admitted for observation of chest pain. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Jun 11;172(11):873–7.

- Backus BE, Six AJ, Kelder JC, Mast TP, van den Akker F, Mast EG, et al. Chest pain in the emergency room: a multicenter validation of the HEART Score. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2010 Sep;9(3):164–9.

- Cafardi SG, Pines JM, Deb P, Powers CA, Shrank WH. Increased observation services in Medicare beneficiaries with chest pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2016 Jan;34(1):16–9.

- Aalam AA, Alsabban A, Pines JM. National trends in chest pain visits in US emergency departments (2006-2016). Emerg Med J EMJ. 2020 Nov;37(11):696–9.

- Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, Amsterdam E, Bhatt DL, Birtcher KK, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368–454.

- Ladapo JA, Blecker S, Douglas PS. Physician decision making and trends in the use of cardiac stress testing in the United States: an analysis of repeated cross-sectional data. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Oct 7;161(7):482–90.

- Will JC, Loustalot F, Hong Y. National trends in visits to physician offices and outpatient clinics for angina 1995 to 2010. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014 Jan;7(1):110–7.

- Kini V, McCarthy FH, Dayoub E, Bradley SM, Masoudi FA, Ho PM, et al. Cardiac Stress Test Trends Among US Patients Younger Than 65 Years, 2005-2012. JAMA Cardiol. 2016 Dec 1;1(9):1038–42.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet Lond Engl. 2007 Oct 20;370(9596):1453–7.

- Fanaroff AC, Rymer JA, Goldstein SA, Simel DL, Newby LK. Does This Patient With Chest Pain Have Acute Coronary Syndrome?: The Rational Clinical Examination Systematic Review. JAMA. 2015 Nov 10;314(18):1955–65.

- Navas A, Guzman B, Hassan A, Borawski JB, Harrison D, Manandhar P, et al. Untapped Potential for Emergency Department Observation Unit Use: A National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) Study. West J Emerg Med. 2022 Jan 18;23(2):134–40.

- Borawski JB, Graff LG, Limkakeng AT. Care of the Patient with Chest Pain in the Observation Unit. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017 Aug;35(3):535–47.

- Samtani K, Issak A, Liston J, Markert RJ, Bricker D. Stress Electrocardiography vs Radionuclide Myocardial Perfusion Imaging among Patients Admitted for Chest Pain: Comparison of Teaching and Nonteaching Hospital Services. South Med J. 2018 Dec;111(12):739–41.

- Laureano-Phillips J, Robinson RD, Aryal S, Blair S, Wilson D, Boyd K, et al. HEART Score Risk Stratification of Low-Risk Chest Pain Patients in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 Aug;74(2):187–203.

- Sabbatini AK, Nallamothu BK, Kocher KE. Reducing variation in hospital admissions from the emergency department for low-mortality conditions may produce savings. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2014 Sep;33(9):1655–63.

- Calder LA, Forster AJ, Stiell IG, Carr LK, Perry JJ, Vaillancourt C, et al. Mapping out the emergency department disposition decision for high-acuity patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2012 Nov;60(5):567-576.e4.

- Kachalia A, Gandhi TK, Puopolo AL, Yoon C, Thomas EJ, Griffey R, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the emergency department: a study of closed malpractice claims from 4 liability insurers. Ann Emerg Med. 2007 Feb;49(2):196–205.

- Katz DA, Williams GC, Brown RL, Aufderheide TP, Bogner M, Rahko PS, et al. Emergency physicians’ fear of malpractice in evaluating patients with possible acute cardiac ischemia. Ann Emerg Med. 2005 Dec;46(6):525–33.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).