1. Introduction

As traffic congestion continues to escalate with rapid economic and social development, network traffic has become a critical area of focus in recent research [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Network traffic can be conceptualized as a spreading process in a network, in which performance is intricately influenced by the underlying network topology, resource allocation, and employed routing strategies [

11].

Given the inherent challenges in modifying existing infrastructure—often suboptimal in nature—and the complexity of large-scale resource reallocation after network establishment, routing strategies emerge as a promising alternative for improving network performance. Modifications to routing strategies are less costly, easier to implement, and more feasible than changes to network topology or resource distribution. For example, adjustments can be made through software updates in computer network routing algorithms.

Consequently, designing efficient routing strategies has become a central focus of research, yielding a substantial body of work [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. However, many of these strategies rely on the FIFO queueing discipline, often neglecting the potential impact of alternative queueing strategies on network performance.

Among FIFO queueing rules, other alternatives, such as last-in-first-out (LIFO) and priority queueing rules, have been explored. Recent studies have examined non-FIFO queueing strategies in routing algorithms. For example, Tadić et al. investigated web-graph models using the LIFO discipline [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Wang et al. applied the LIFO queueing policy to network congestion scenarios with limited queue caches. Kim et al. introduced a priority routing strategy based on preestablished packet priorities, noting improvements in congestion states but deterioration under free-flow conditions [

25]. Tang and Zhou proposed a strategy in which nodes select the shortest path among unoccupied edges based on an effective distance metric by combining waiting time and path length, which significantly enhances network capacity [

26]. Du et al. introduced a shortest-remaining-path-first queueing strategy, prioritising packets by their distance to their destination. This strategy led to improvements in several transportation efficiency metrics despite unchanged network capacity [

27]. Zhang et al. presented a dynamic information-based queueing strategy, and they observed notable improvements in traffic indices, such as average travel time and waiting time rates, although network capacity remained unaffected [

28]. Wu et al. proposed a shortest-distance-first queueing strategy that notably improved the network throughput and packet arrival rates [

29].

Priority queueing rules exhibit varying degrees of performance enhancement; however, their efficacy is often contingent on specific routing policies. This raises the question of whether a universally applicable priority queueing rule exists that can consistently improve network transmission performance across all FIFO-based routing strategies. In this study, we propose a GPQ strategy, designed to enhance the performance of all FIFO-based routing approaches.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: In

Section 2, we present the materials and methods used in this study, followed by simulation results and analysis in

Section 3. Finally, the paper concludes with a summary of the findings in Section .

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Network Models

A. Barabási-Albert (BA) network model

Many real-world complex networks exhibit a scale-free nature characterised by a power law degree distribution

. To study the heterogeneous structure of such networks, the Barabási-Albert (BA) model proposed by Barabási and Albert provides a framework for generating scale-free networks [

30]. The BA model is described as follows:

- (1)

Initialization. Beginning with nodes, each node is fully connected to all other nodes in the initial network.

- (2)

Node addition. A new node is introduced to the network at each time step. This new node connects to existing nodes.

- (3)

Attachment mechanism. The probability that a new node connects to an existing node i with degree is given as follows:

where the summation is the degrees of all existing nodes. This model effectively captures the evolution of scale-free networks through its preferential attachment mechanism, in which nodes with higher degrees are more likely to receive new connections.

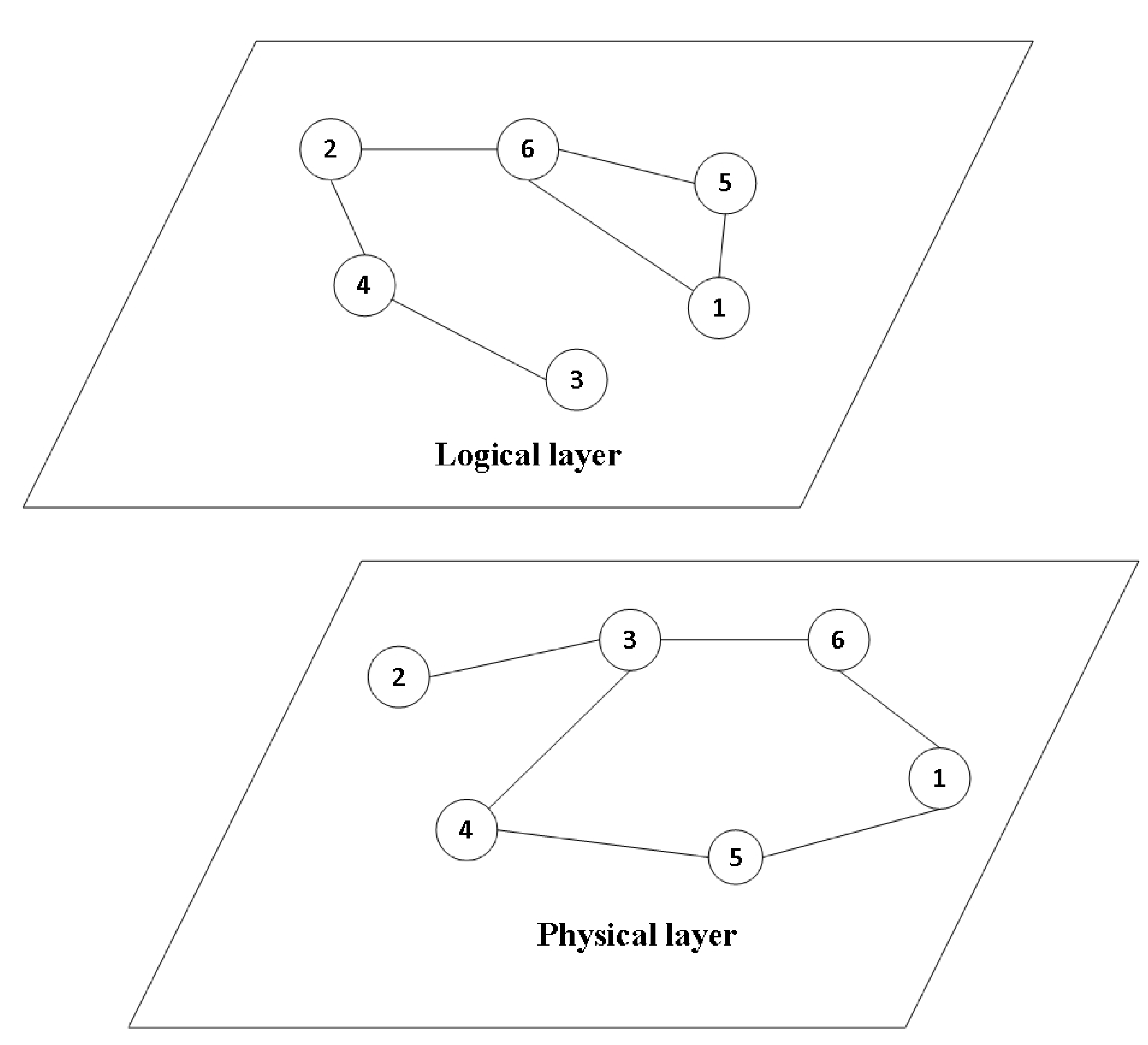

B. Two-layer network model

In real-world scenarios, many networks, including information, transport, and power networks, possess a multilayer structure in which layers are interconnected through shared links or nodes [

31,

32]. The two-layer network model is composed of two distinct layers: the physical network (Layer P) and the logical network (Layer L), which contain

and

nodes, respectively. For operational simplicity, we assume that the number of nodes in the logical network is equal to the number in the physical network and that there is a one-to-one correspondence between nodes in the two layers. This correspondence is established randomly, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

In

Figure 1, it is assumed that both the logical and physical layers use the shortest path routing strategy. In the logical layer, the routing path from node 2 to node 5 is

, and the corresponding logical edges are

and

. This logical layer path maps the physical layer paths as

and

. Consequently, the entire path for packet transmission through the physical layer, from source to destination, is

. The actual packet transmission in the physical layer is constrained by both the logical and physical layer routes. In this study, it is assumed that the two subnetworks are built by using a BA model of the same size.

C. Dynamic network model

Complex networks, such as social, biological, and technological networks, often exhibit dynamic behaviour, with nodes and edges evolving over time. In such dynamic networks, static network models may become insufficient due to real-time topology changes. Thus, new models are required to address these characteristics [

33].

Yang et al. proposed a dynamic network model in which

N agents, numbered from 1 to

N, move within a square area of size

with periodic boundary conditions [

34]. Initially, agents are randomly distributed. Each agent’s movement direction is updated randomly at each time step

, and speed

v is kept constant for simplicity. All agents have a uniform communication radius

, and two agents can communicate if the distance between them is less than

.

2.2. Traffic Model

The network model provides the foundational framework for dynamic traffic management, whereas the traffic model describes the evolving dynamics of traffic flow within this network framework.

A. Traffic model for a single-layer network

The traffic model for a single-layer network is defined as follows: Each node in the network functions both as a host and a router capable of generating and forwarding packets. At each time step,

R packets are generated, with each packet having randomly assigned source and destination nodes. Each node can transmit up to

C packets to its immediate neighbours. The transmission path of each packet is determined by the network routing strategy. When multiple paths are available, a single path is selected randomly. Packets are removed from the network after reaching their destination [

35].

The network traffic capacity is characterised by the maximum packet generation rate

at which a phase transition from free flow to congestion occurs. This transition is quantified by the order parameter, as follows [

36]:

where

and

represent the time average over windows of width

. Here,

denotes the number of packets in the network at time

t. For small values of

R, where

, the packet generation rate is balanced by the packet removal rate, thereby preventing congestion. However, as

R increases, more packets fail to be delivered in a timely manner, leading to accumulation at central nodes and, ultimately, traffic congestion.

B. Traffic model for a two-layer network

The traffic model for a two-layer network extends the principles of the single-layer network model by incorporating additional complexities. Packets are generated at the logical layer, and source and destination nodes are selected randomly within this layer. Each edge in the logical layer corresponds to a designated path in the physical layer, which handles the actual transmission of packets [

37]. For a detailed discussion and illustrative examples, refer to the subsection on the two-layer network model.

C. Traffic model for a dynamic network

In dynamic networks, the model must account for the continual evolution of nodes and links, which requires sophisticated approaches that are beyond those used in static network models. This paper introduces a traffic model specifically designed for dynamic networks [

34] that is built on the foundational single-layer network model.

At each time step, R packets are generated, and each packet is assigned a source and destination node at random. The transmission path of each packet is determined by the network routing strategy. Importantly, packets can only be transmitted between nodes when the communication distance between the nodes is less than a specified threshold, . After reaching their designated destination, packets are removed from the network.

2.3. Routing Strategy

This paper explores enhancements to the FIFO routing strategy by examining several routing approaches: shortest path routing [

38], global dynamic routing [

39], and greedy routing based on dynamic networks [

29]. Each strategy is introduced and analysed in the following sections.

A. Shortest path routing

The shortest path routing strategy selects the path with the minimum total length for packet transmission. For a given packet

m with multiple possible paths between the source and destination, the routing strategy aims to minimise the sum of the path weights. Formally, the shortest path

from node

i to destination node

for packet

m is denoted as follows:

where

denotes the weight of path segment

j, and

l is the total number of segments in the path.

B. Global dynamic routing

The global dynamic routing strategy selects paths based on the sum of the node queue lengths, aiming to minimise congestion. For a packet

m travelling from a source to a destination, this approach determines the path that minimises the cumulative queue lengths at intermediate nodes. Thus, path

is given as follows:

where

represents the queue length of node

, and

l denotes the path length.

C. Greedy routing strategy based on dynamic network

In this strategy, packets are directed to the neighbouring node that is closest to the destination. Specifically, for a given packet

m at time

t, the routing strategy selects the neighbour

that minimises the Euclidean distance to the packet’s destination. The routing path

is defined as follows:

where

J denotes the set of neighbouring nodes of agent

i, and

and

are the coordinates of the neighbour agent

j at time

t, and

and

are the coordinates of the packet destination at time

t. This strategy directs packets to the nearest neighbour relative to the destination at time

t. Because of the dynamic nature of node movements, the chosen neighbour may not remain optimal in subsequent time steps; therefore, this strategy is inherently locally optimal. Thus, it is referred to as a greedy routing strategy based on dynamic networks.

2.4. The Proposed Queueing Strategy

We propose an innovative GPQ strategy to enhance FIFO-based routing approaches. Consider a network node

i with

M packets queued for delivery. Each packet

has a designated destination node

and a set of possible delivery paths, denoted as

. The delivery path for a packet is determined by a routing function

F, as follows:

where

F selects the optimal path for each packet based on the routing strategy. If multiple paths are equivalent, one is selected randomly.

The GPQ strategy introduces a priority mechanism to the queueing process. Specifically, it prioritizes packets for transmission by leveraging the same routing function

F used to determine the packet’s delivery path. The priority queueing policy is expressed as:

where

represents the priority value of packet

k, and the packet with the highest priority is selected for transmission. In cases where multiple packets have the same priority, one is chosen randomly.

The core innovation of this strategy lies in aligning the queueing policy with the routing function. By using the same F function for both path selection and priority determination, the GPQ strategy ensures consistency and compatibility with the underlying routing policy.

To illustrate, consider a routing function F that minimizes the total queue length along the path from the source node i to the destination node . Under the GPQ strategy, F not only determines the delivery path but also identifies the packet with the shortest remaining path (based on queue lengths) as the priority packet for transmission. This approach effectively reduces congestion by dynamically adapting to real-time network conditions.

By incorporating this adaptive priority mechanism, the GPQ strategy significantly improves network transmission efficiency compared to traditional FIFO methods, while maintaining broad applicability across various routing paradigms and network configurations.

3. Simulation Results and Analysis

This section presents an evaluation of the proposed queueing strategy across various network scenarios, including single-layer, multilayer, and dynamic networks. The performance of the proposed approach is compared against that of the FIFO queueing rule to assess its impact on network transmission performance.

3.1. Simulation on a Single-Layer Network

We first evaluated the proposed queueing policy in a single-layer network employing global dynamic routing. In the proposed priority queueing policy, the F function is defined as , where represents the queue length of node . For any given packet m, path with the minimum sum of cache queue lengths, as determined by the F function, is selected. The path is subsequently selected from the set of paths , with a preference for the path that exhibits the smallest cumulative cache queue length among all available paths. The packet k is then preferentially transmitted. This selection process is executed iteratively at each time step, with the node continuing to select packets for transmission until its maximum sending capacity is reached.

Simulations were conducted to compare the transmission performance of the FIFO and GPQ policies under global dynamic routing conditions. The experiments were conducted on a scale-free network with the following parameters: network size

, initial number of nodes

, average degree

, sending capacity

, and network runtime

.

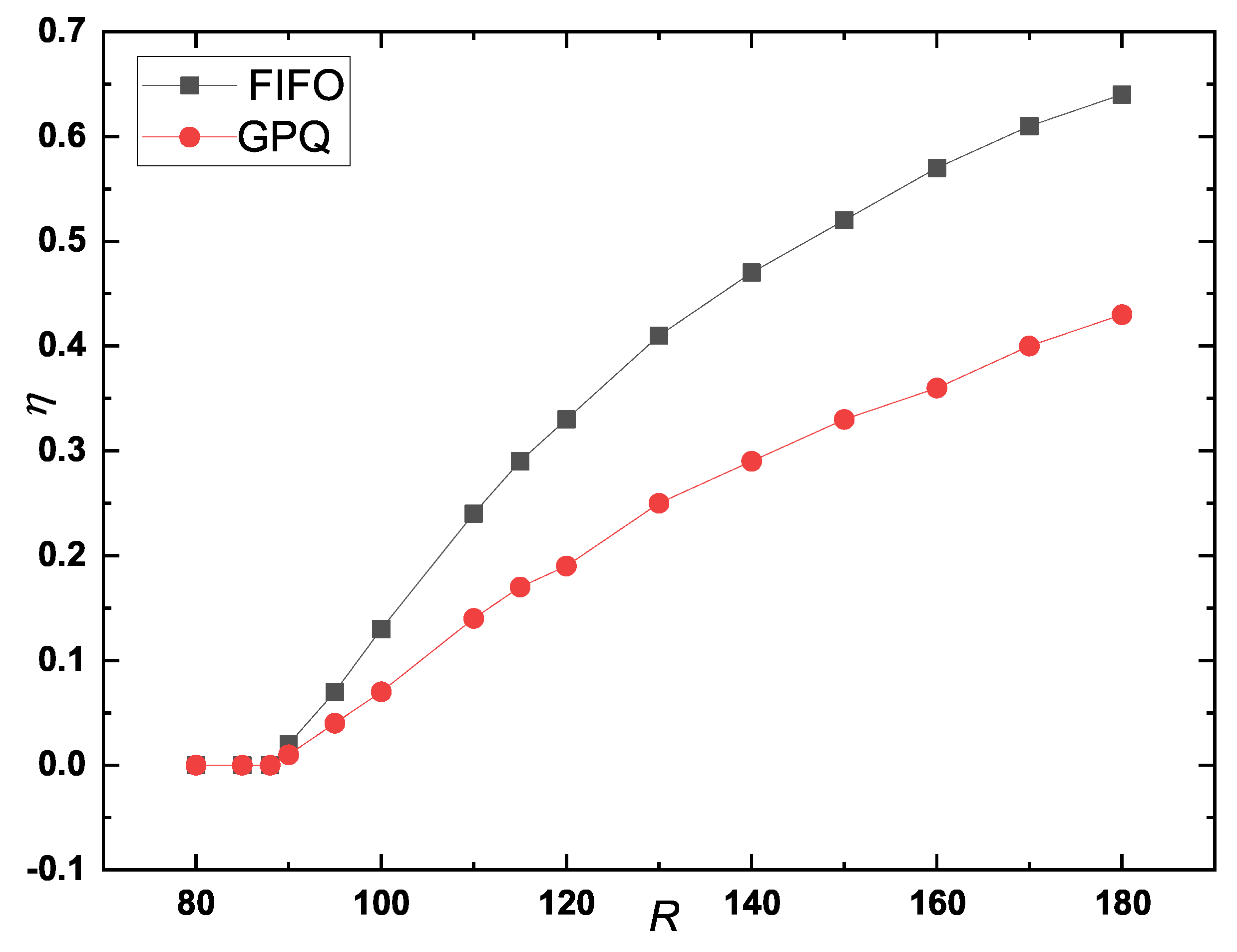

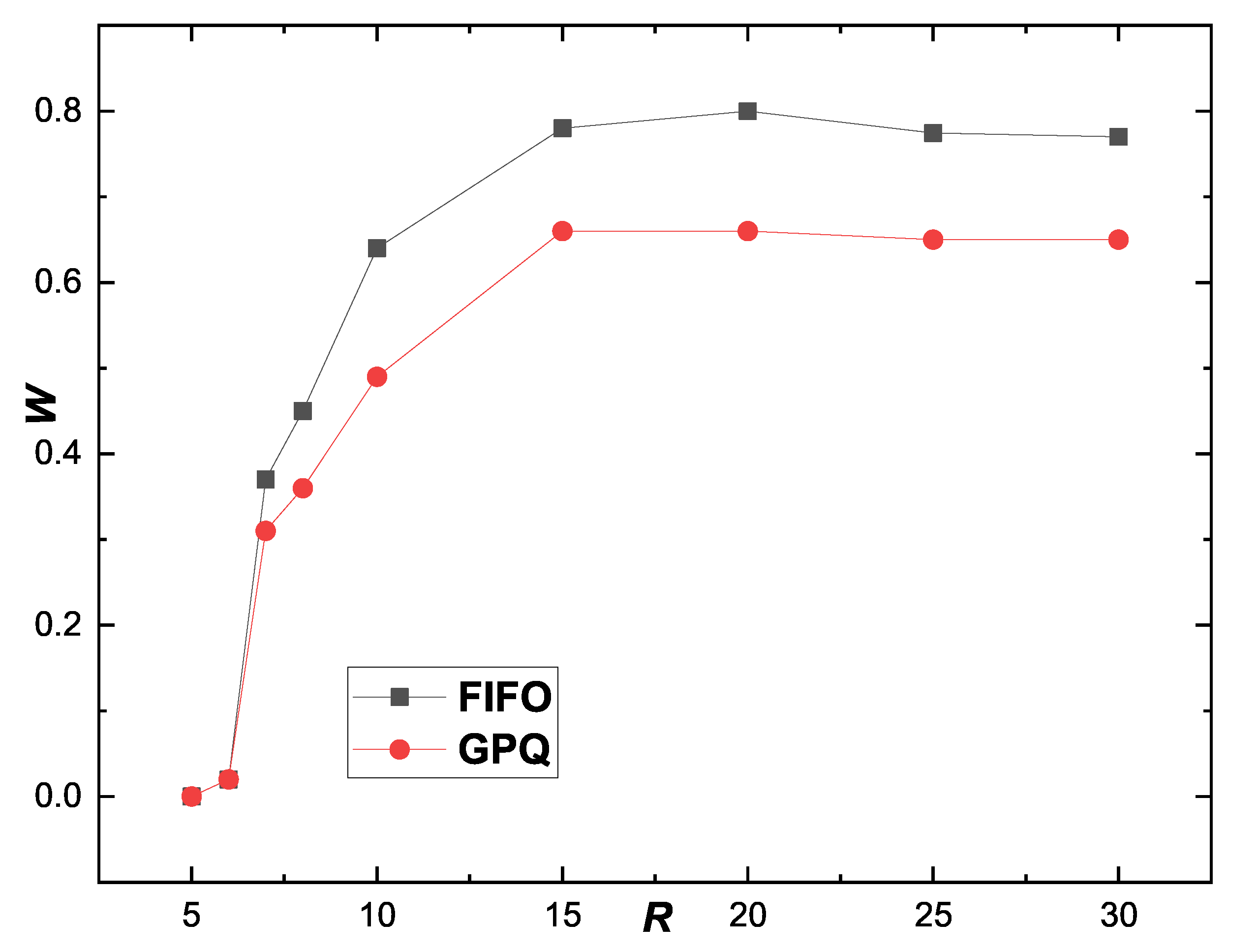

Figure 2 illustrates the variation in the order parameter

as a function of the packet generation rate

R.

It is evident from this figure that the critical packet generation rate is similar for both queueing strategies. However, when , the value of in FIFO is greater than that in the GPQ strategy, with the difference becoming more pronounced as R increases. This suggests that under congested conditions, the GPQ strategy is more effective at alleviating network congestion than the FIFO strategy, with the performance disparity becoming more significant at higher values of R.

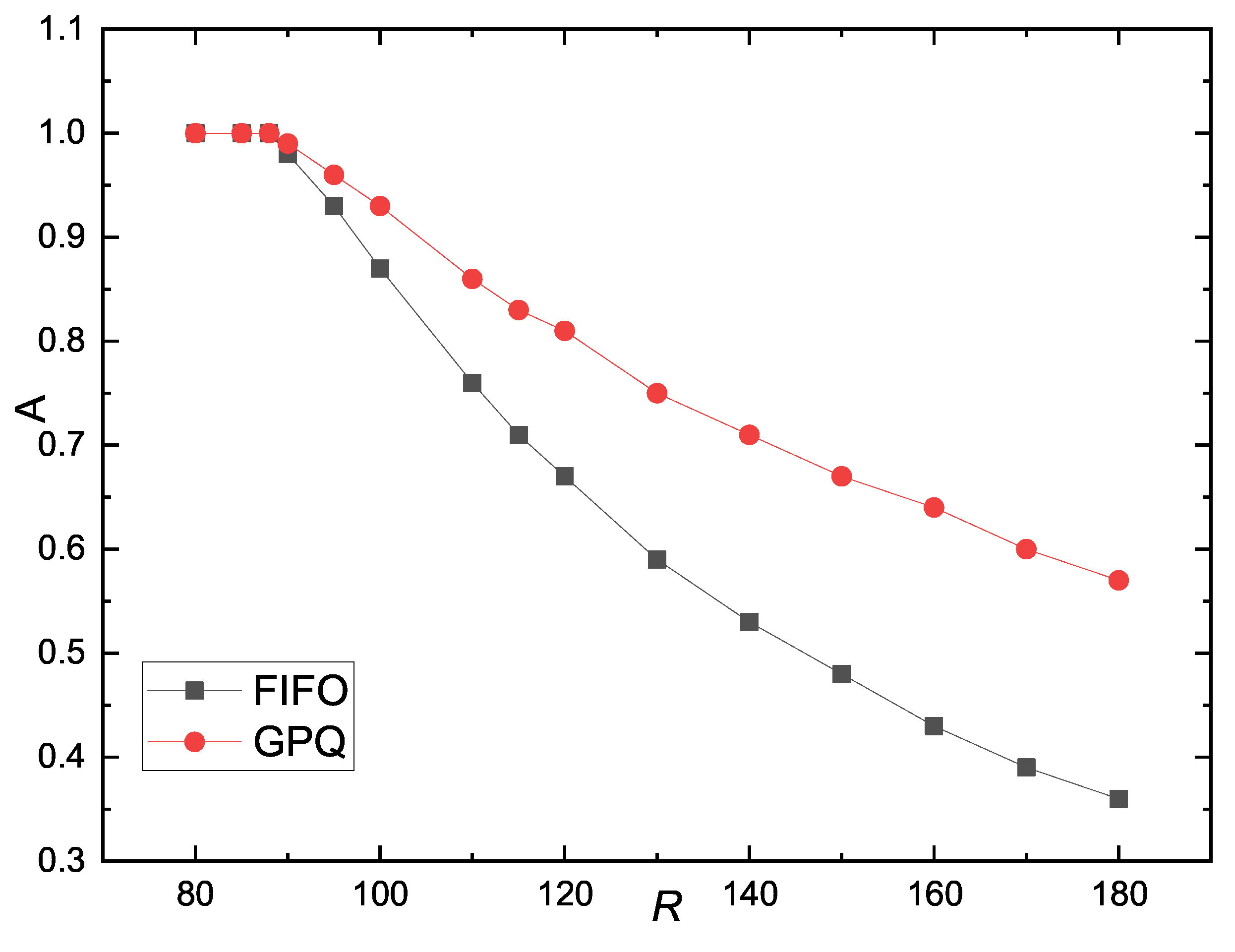

We also examined the relationship between packet arrival rate

A and packet generation rate

R. The rate

A is defined as the ratio of the number of arrived packets to the number of generated packets, as follows [

40]:

, where

represents the number of packets that have arrived, and

denotes the number of generated packets. The rate

A serves as an indicator of system throughput. In a free-flowing state, in which packets are delivered to their destination without delay,

A approaches 1. In contrast, in a congested state, in which packets accumulate in the network,

A is less than 1.

Figure 3 shows that

A is equal to 1 for both queueing strategies when

, indicating that all packets reach their destination without delay. For

,

A decreased gradually in both strategies, and a more gradual decrease is observed with the GPQ strategy. This result is consistent with the findings presented in

Figure 2.

3.2. Simulation on a Two-Layer Network

Next, we compared the performance of the FIFO and GPQ queueing strategies in a two-layer network via shortest-path routing. In our priority queueing policy, function F is defined as , where represents the weight of path segment j. For any packet m, path with the minimal path length, as determined by function F, is selected. The queueing policy selects the path with the smallest length according to the F function for all . Assuming , packet k is preferentially sent. We utilised a two-layer network model characterised by scale-free networks in both the logical and physical layers, with routing performed via shortest path algorithms. Nodes across the two layers are matched randomly. The network parameters are as follows: node size , initial number of nodes , average degree , sending capacity , and network runtime . Note that node cache queue lengths are considered unlimited. The simulation results were averaged over 20 networks of equal size.

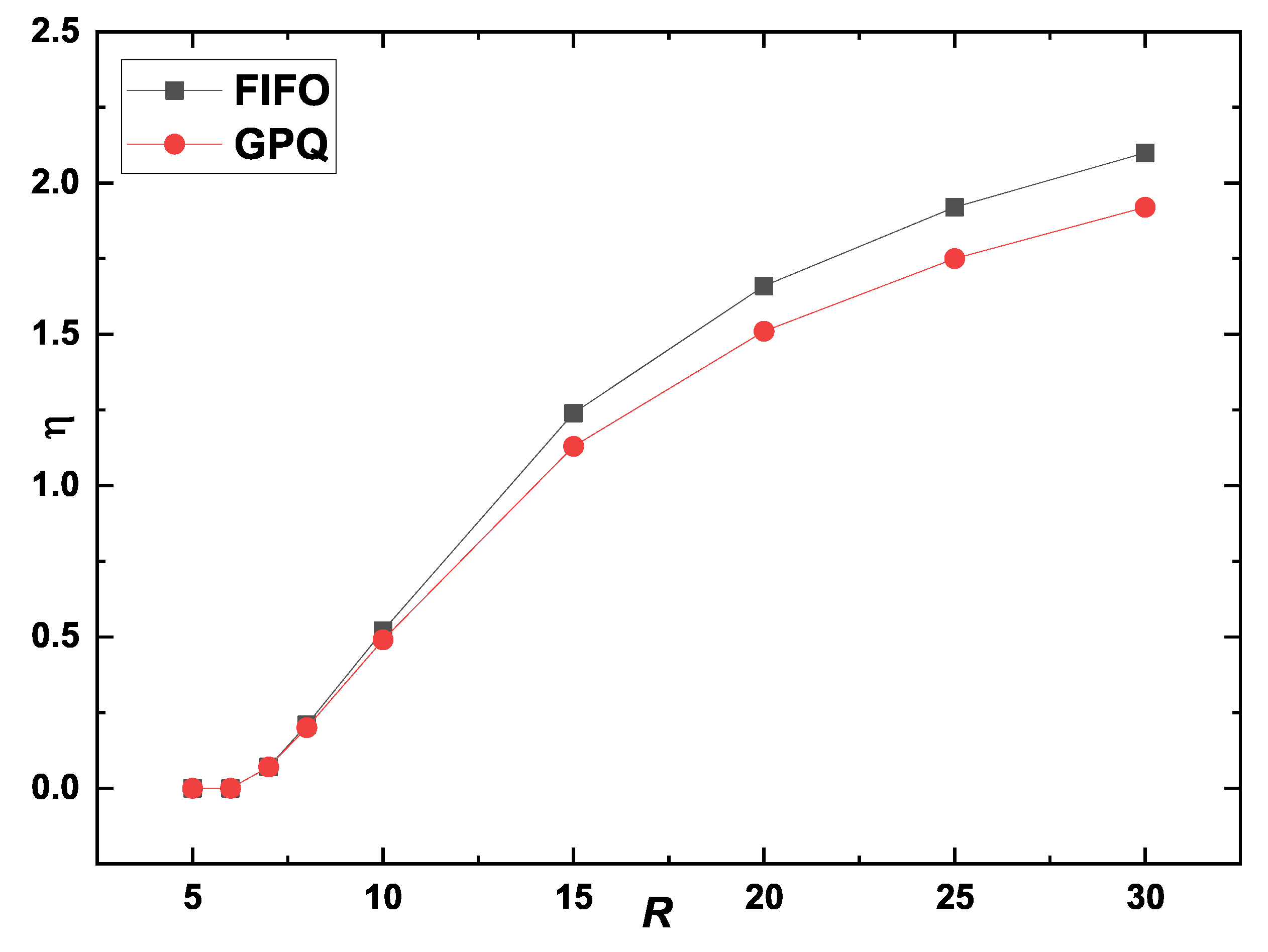

Figure 4 illustrates the relationship between order parameter

and packet generation rate

R. The results shown in

Figure 4 are consistent with those presented in

Figure 2, indicating that the critical packet generation rate

is approximately 6 for both queueing strategies. When

, the order parameter

in FIFO is greater than that in the GPQ strategy, suggesting that the GPQ strategy effectively reduces network congestion compared with FIFO, with the benefit becoming more significant as

R increases.

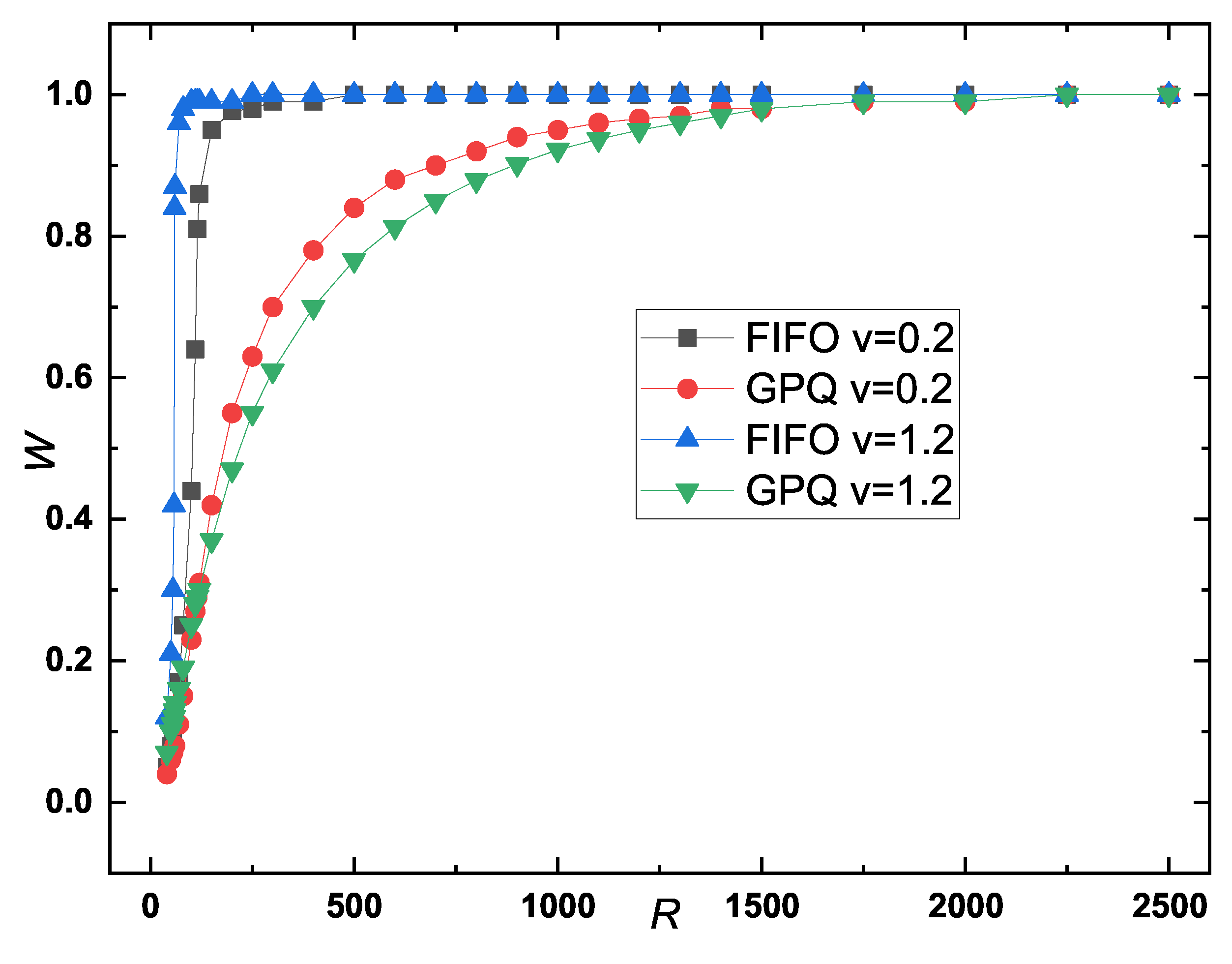

Figure 5 illustrates the relationship between the rate of waiting time to travel time

W and packet generation rate

R. The rate

W is defined as follows [

27]:

where

represents the travel time of packet

i,

denotes the waiting time of packet

i, and

is the number of packets that have arrived. In general,

W is an indicator of customer satisfaction. In various systems, such as airline operations and the Worldwide Web, users may exhibit increased impatience if the

W is high.

When , W is zero in both queueing strategies, indicating that packets do not experience any waiting in the free-flow state. However, when , W increases rapidly for both queueing strategies. Notably, in the GPQ strategy, the increase in W is more gradual, and this effect becomes more pronounced at higher values of R. This observation suggests that the GPQ strategy is more effective at reducing waiting times under congested conditions, particularly at higher values of R.

3.3. Simulation on a Dynamic Network

Finally, we examined the performance of the proposed priority queueing policy in a dynamic network employing a greedy routing strategy. In this context, function

F is defined as follows:

where

J represents the set of neighbouring nodes. For any packet

m, path

with the minimum path length is selected on the basis of the

F function. The queueing policy then determines the path with the smallest length among all possible paths

, denoted as

. Consequently, packet

k associated with

is given preferential treatment for transmission.

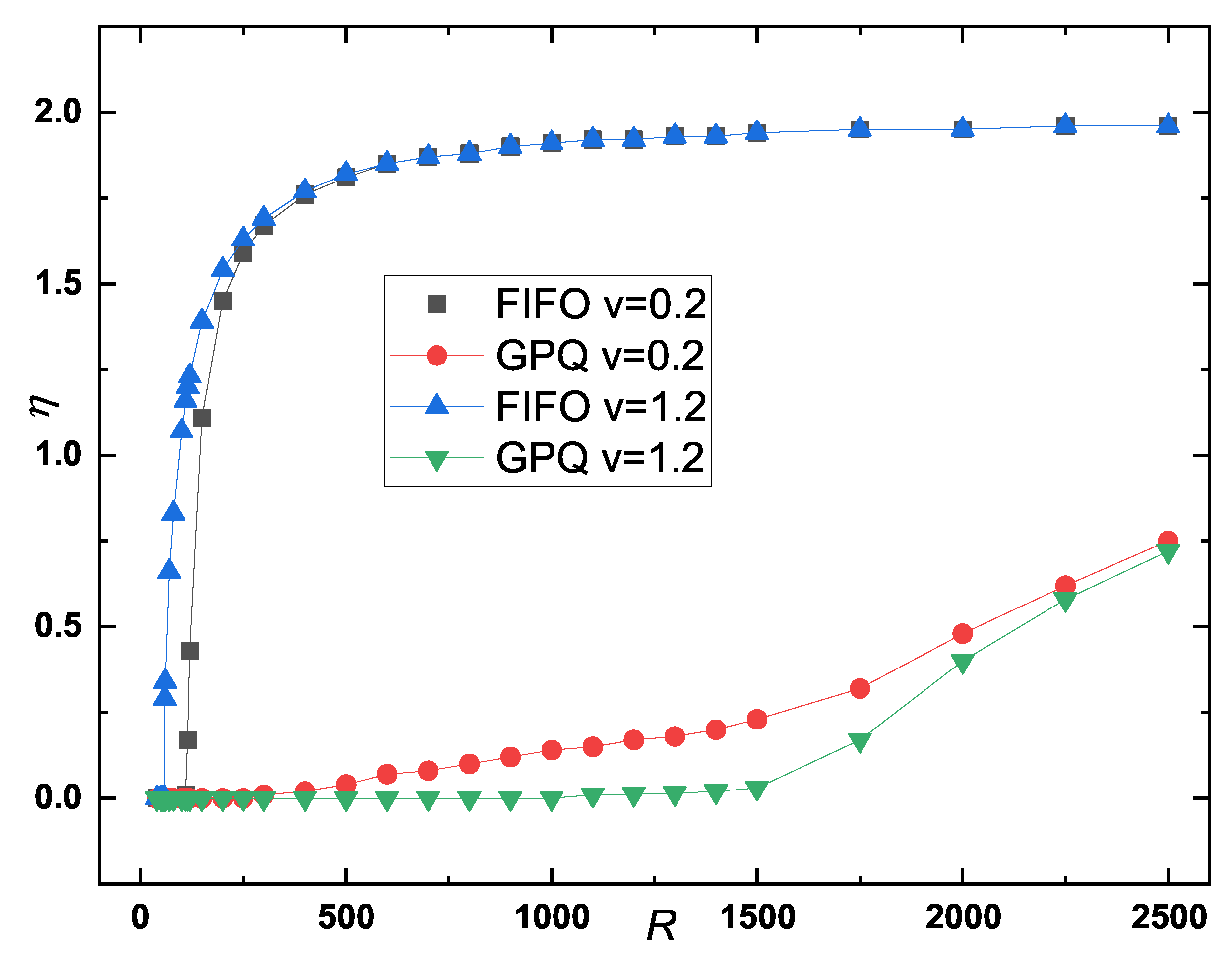

Figure 6 shows order parameter

versus packet generation rate

R for different moving speeds

v with

. The critical value

marks the transition from a free-flow state to congestion over a sharp interval of

R. The threshold

of the GPQ strategy is significantly greater than that of the FIFO strategy, especially at higher speeds. For example,

for the FIFO strategy is approximately 59 at

, whereas for the GPQ strategy, it is approximately 1100, indicating a substantial improvement in network throughput.

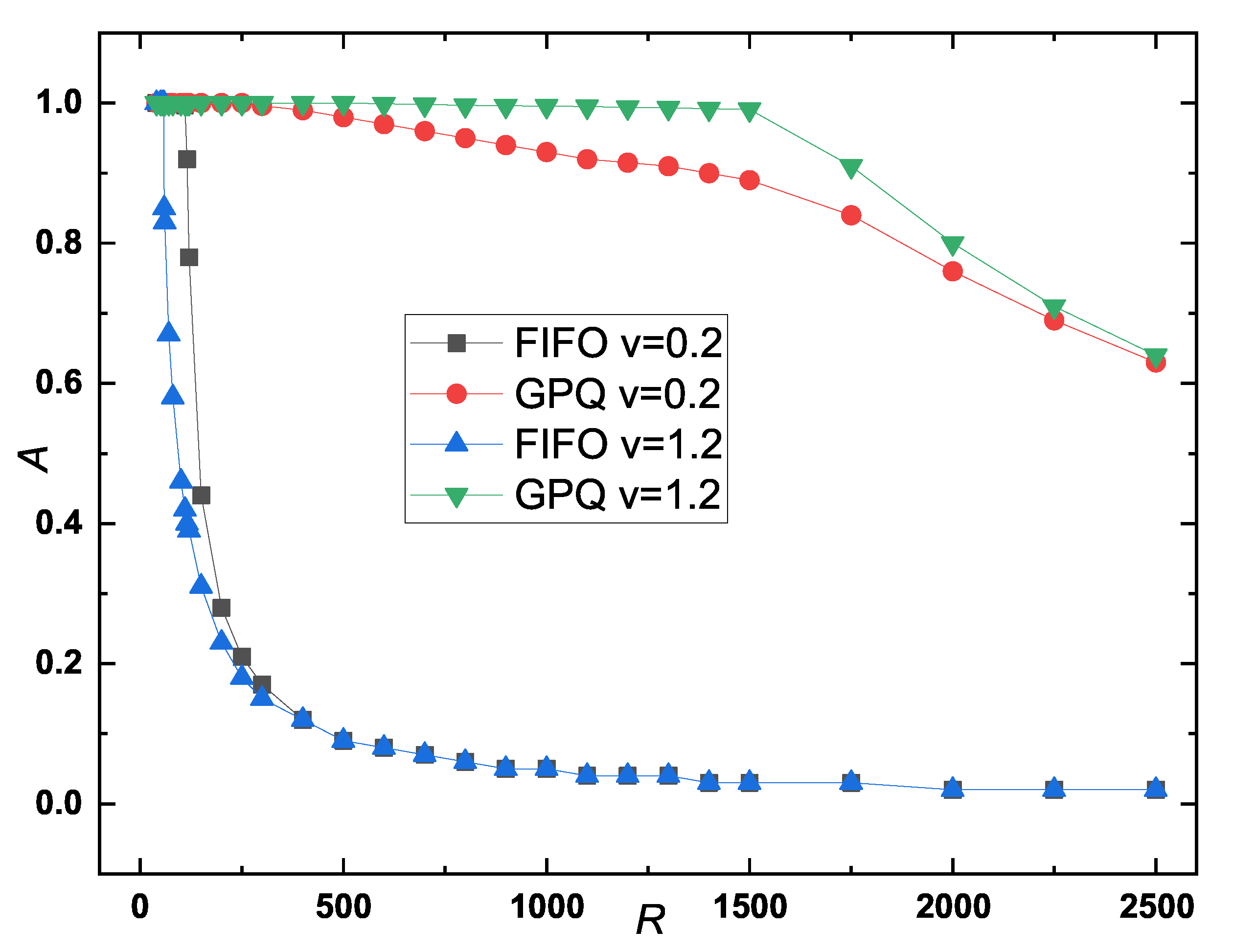

Figure 7 illustrates the relationship between packet arrival rates

A and

R. In the free-flow state,

A approaches 1 for both strategies. However, in the congested state, packet arrival rate

A decreased more rapidly in the FIFO strategy than in the GPQ strategy. For example, at

, in the FIFO strategy,

A approaches 0, whereas for the GPQ strategy, it remains approximately 0.76 and 0.8 at

and

, respectively.

Figure 8 illustrates the relationship between the rate of waiting time to travel time

W and packet generation rate

R. When

R is low, the rate

W is minimal for both routing strategies. However, as

R increases,

W increases sharply, and a more pronounced increase is observed in the FIFO strategy. At moving speeds of

and

,

W approaches its maximum value of 1 at approximately

and

, respectively. In contrast, for the GPQ strategy,

W approaches 1 only when

R reaches approximately 1750.

These results clearly indicate that compared with the FIFO strategy, the GPQ strategy improves network capacity, achieves a higher packet arrival rate, and reduces the rate of waiting time to travel time.

4. Conclusions

This study proposes a novel GPQ strategy aimed at enhancing the performance of FIFO-based routing approaches in complex networks. Through extensive empirical analysis conducted on single-layer, two-layer, and dynamic network configurations, the GPQ strategy demonstrates significant improvements in key performance metrics, including network throughput and average packet delay, across various scenarios. These results affirm the effectiveness of the proposed method in addressing congestion challenges inherent to diverse network environments.

The primary contribution of this work lies in the development of a universally applicable queueing strategy that aligns with underlying routing policies, enabling seamless integration across different network topologies and routing paradigms. By incorporating packet prioritization into the forwarding process, the GPQ strategy introduces a level of adaptability and optimization that has been largely overlooked in traditional FIFO-based methods. Furthermore, the flexibility and scalability of the GPQ strategy make it a promising solution for enhancing network transmission performance in a wide range of applications, from engineered systems to natural networks. While the proposed approach delivers substantial benefits, it also highlights the importance of tailoring queueing strategies to specific routing policies to achieve optimal results.

In summary, this work provides a significant advancement in the field of network optimization, offering a robust, scalable, and broadly applicable method for improving transportation efficiency in complex networks. The findings open new avenues for research into the integration of queueing strategies with routing protocols, paving the way for more effective and adaptive network management solutions.

References

- Toroczkai, Z.; Bassler, K. E. Jamming is limited in scale-free systems. Nature 2004, 428, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, M. A. D.; Barabási, A. L. Fluctuations in network dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 028701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Ruan, Z. Y.; Tang, M.; Do, Y. H.; Liu, Z. H. Influence of periodic traffic congestion on epidemic spreading. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C 2016, 27, 1650048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, T.; Yodo, N. A survey of road traffic congestion measures towards a sustainable and resilient transportation system. Sustainability 2020, 12(11), 4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez González, S.; Bedoya-Maya, F.; Calatayud, A. Understanding the effect of traffic congestion on accidents using big data. Sustainability 2021, 13(13), 7500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J. L.; Zhang, J. F.; Zhang, Y. Q. Effective gravitation path routing strategy on scale-free networks. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 96031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Y.; Huang, T.; Guo, Z. X.; He, Z. Complex-network-based traffic network analysis and dynamics: A comprehensive review. Physica A 2022, 607, 128063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokaba, T.; Doorsamy, W.; Paul B., S. A comparative study of ensemble models for predicting road traffic congestion. Applied Sciences 2022, 12(3), 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Song, X. Mitigation strategy of cascading failures in urban traffic congestion based on complex networks. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C 2023, 34, 2350022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G. H.; Yang, H. J. Traffic systems recovery from complete congestion by the targeted dropping of packets. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2019, 33, 1950096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Y.; Huang, W.; Cattani, C.; Altieri, G. Traffic dynamics on complex networks: A survey. Math. Probl. Eng. 2012, 2012, 732698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Tareen, W. U. K.; Usman, M.; Ali, H.; Bari, I.; Horan, B.; Mekhilef, S.; Asif, M.; Ahmed, S.; Mahmood, A. A review of optimal charging strategy for electric vehicles under dynamic pricing schemes in the distribution charging network. Sustainability 2020, 12(23), 10160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma J., L.; Wei, J.; Tang, X.; Zhao, X. An improved efficient routing strategy on two-layer networks. Pramana 2022, 96(2), 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Rourich M., A. , Rodríguez-Pérez F. J. Efficient data transfer by evaluating closeness centrality for dynamic social complex network-inspired routing. Applied Sciences, 1076. [Google Scholar]

- Ribalta, S.; Albert; Gomez, S. ; Arenas, A. Congestion induced by the structure of multiplex networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 108701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Wen, T.; Cheong, K. H. Efficient traffic management in networks with limited resources: The switching routing strategy. CHAOS SOLITON FRACT. 2024, 181, 114658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadić, B. , Thurner, S. Search and topology aspects in transport on scale-free networks. Phys. A 2005, 346, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, X.; Hu, B.; Liu, M.; Wang, X. Ship Network Traffic Engineering Based on Reinforcement Learning. Electronics 2024, 13(9), 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Wen, A.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J. An adaptive intelligent routing algorithm based on deep reinforcement learning. Comput. Commun. 2024, 216, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadić, B.; Thurner, S. Information super-diffusion on structured networks. Physica A 2004, 332, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadić, B.; Thurner, S.; Rodgers, G. J. Traffic on complex networks: Towards understanding global statistical properties from microscopic density fluctuations. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 69, 036102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadić, B.; Rodgers, G. J.; Thurner, S. Transport on complex networks: Flow, jamming and optimization. Int. J. Bifurcat. Chaos 2007, 17, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andjelković, M.; Gupte, N.; Tadić, B. Hidden geometry of traffic jamming. Phys. Rev. E 2015, 91, 052817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, X.; Wang, X. K.; Chen, J. J.; Liu, D.; Zhu, K. J.; Guo, N. Major impact of queue-rule choice on the performance of dynamic networks with limited buffer size. Chinese Phys. B 2020, 29, 018901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kahng, B.; Kim, D. Jamming transition in traffic flow under the priority queuing protocol. Europhys. Lett. 2009, 86, 58002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Zhou, T. Efficient routing strategies in scale-free networks with limited bandwidth. Phys. Rev. E 2011, 84, 026116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W. B.; Wu, Z. X.; Cai, K. Q. Effective usage of shortest paths promotes transportation efficiency on scale-free networks. Physica A 2013, 392, 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. J.; Guan, X. M.; Sun, D. F.; Tang, S. T. The effect of queueing strategy on network traffic. Commun. Theor. Phys. 2013, 60, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G. H.; Yang, H. J.; Pan, J. H. Efficient priority queueing routing strategy on networks of mobile agents. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2018, 32, 1850137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabási, A. L.; Albert, R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science 1999, 286(5439), 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurant, M.; Thiran, P. Layered complex networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96(13), 138701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R. G.; Barthelemy, M. Transport on coupled spatial networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109(12), 128703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, S. A.; Braha, D. Dynamic model of time-dependent complex networks. Phys. Rev. E 2010, 82(4), 046105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. X.; Wang, W. X.; Xie, Y. B.; Lai, Y. C.; Wang, B. H. Transportation dynamics on networks of mobile agents. Phys. Rev. E 2011, 83, 016102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W. X.; Wang, B. H.; Yin, C. Y.; Xie, Y. B.; Zhou, T. Traffic dynamics based on local routing protocol on a scale-free network. Phys. Rev. E 2006, 73, 026111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, A.; Guilera, A. D.; Guimera, R. Communication in networks with hierarchical branching. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J. L.; Wang, H. L.; Zhang, Z. X.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, C.; Qi, Z.; Liu, Y. An efficient routing strategy for traffic dynamics on two-layer complex networks. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2018, 32(13), 1850155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awerbuch, B. Shortest paths and loop-free routing in dynamic networks. Comput. Commun. Rev. 1990, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, X.; Hu, M. B.; Jiang, R.; Wu, Q. S. Global dynamic routing for scale-free networks. Phys. Rev. E 2010, 81(1), 016113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Tang, M.; Yang, H. Optimal forwarding ratio on dynamical networks with heterogeneous mobility. Eur. Phys. J. B 2013, 86(5), 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).