Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

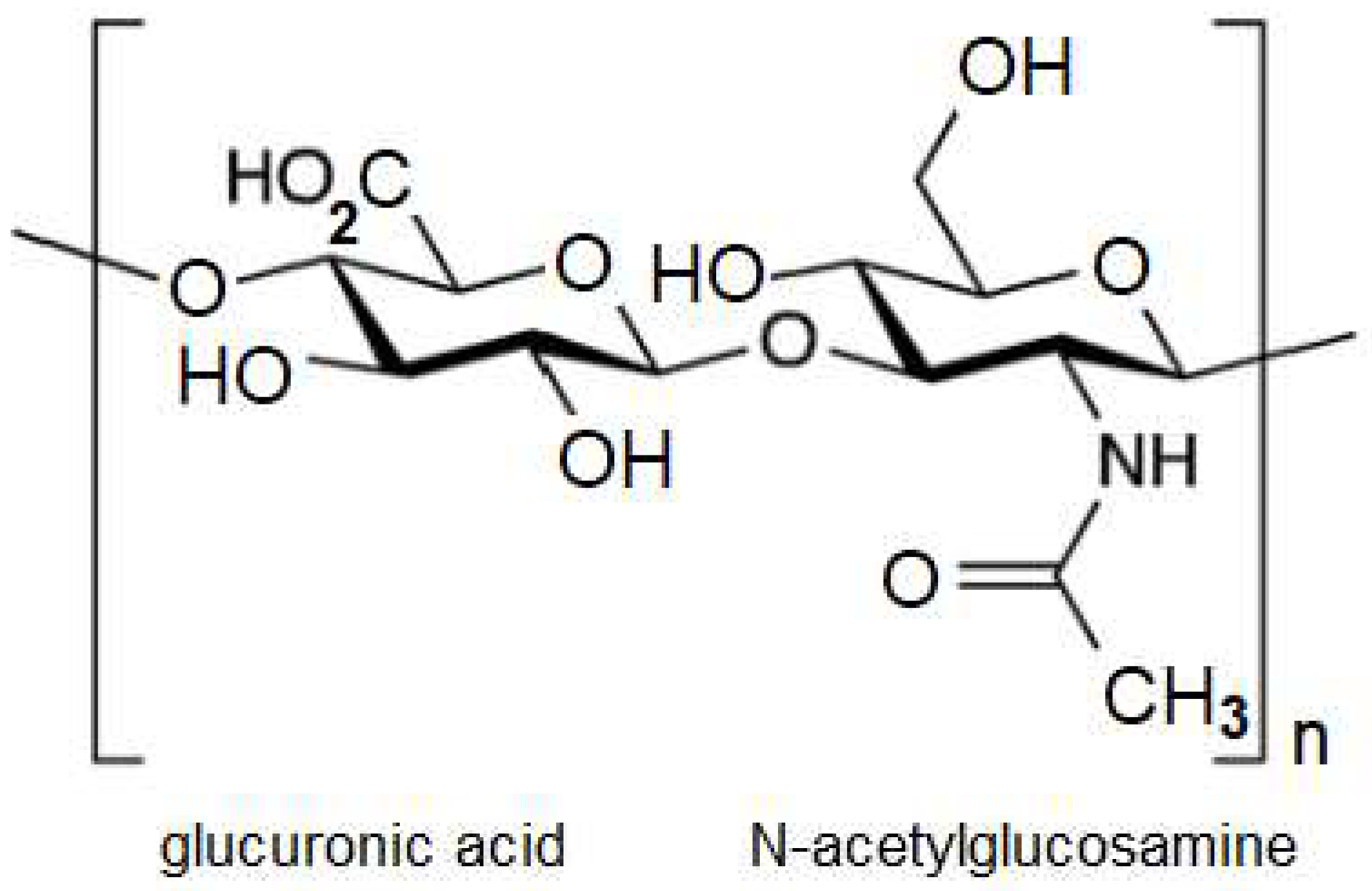

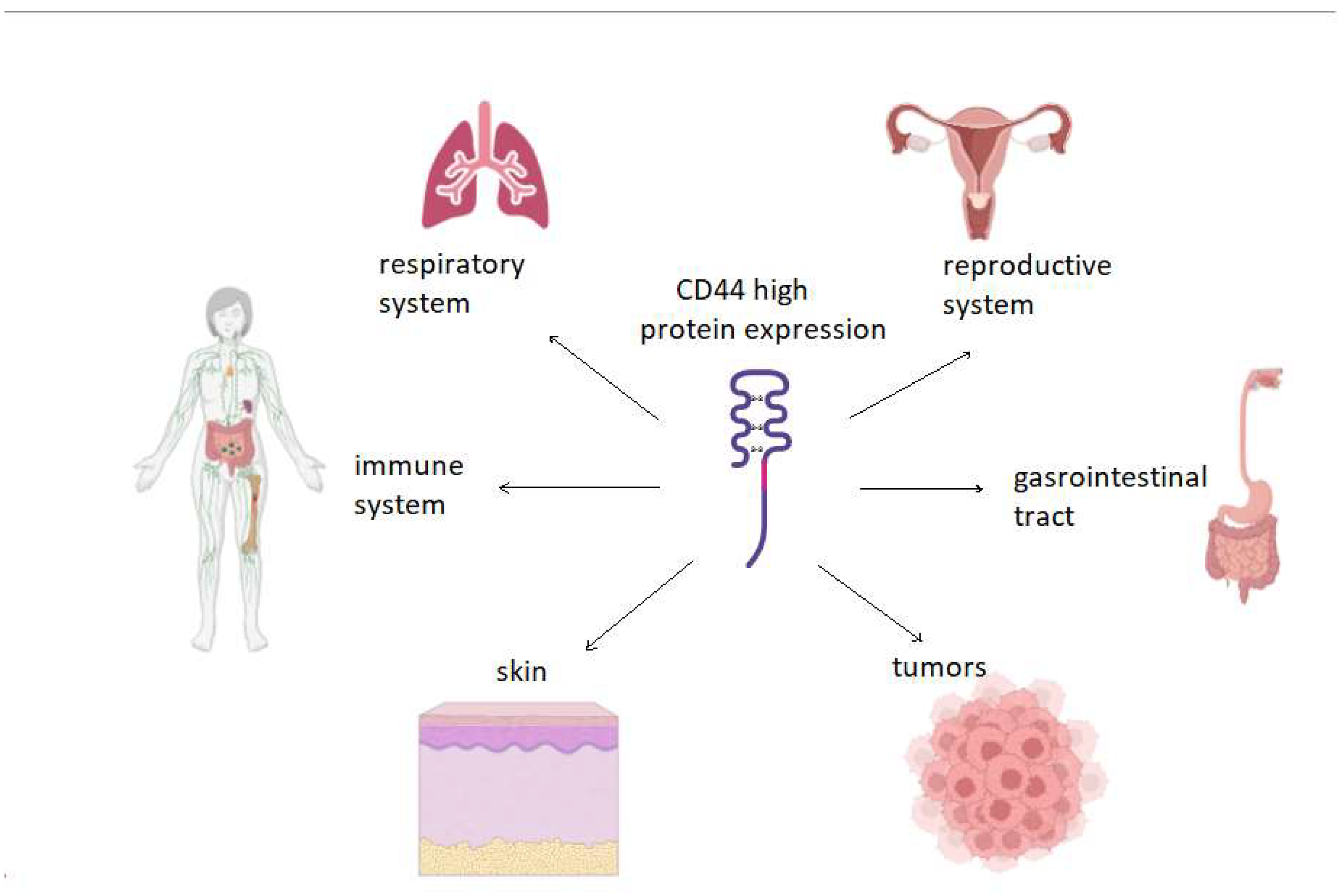

In recent years, hyaluronic acid (HA) has attracted increasing attention as a promising biomaterial for the development of drug delivery systems. Due to its unique properties, such as high biocompatibility, low toxicity, and modifiability, HA is becoming a basis for the creation of targeted drug delivery systems, especially in the field of oncology. Receptors for HA overexpressed in subpopulations of cancer cells and one of them, CD44, is recognized as a molecular marker for cancer stem cells. This review examines the role of HA and its receptors in health and tumors and analyzes existing HA-based delivery systems and their use in various types of cancer. The development of new HA-based drug delivery systems will bring new opportunities and challenges to anti-cancer therapy.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Hyaluronic Acid

3. Hyaluronic Acid and Oncology

4. Hyaluronic Acid and СD44

5. Hyaluronic Acid and Other Receptors of HA

6. HA-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Solid Tumors

7. HA-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Hematological Malignancies

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, J.; Yu, G.; Huang, F. , Supramolecular chemotherapy based on host–guest molecular recognition: a novel strategy in the battle against cancer with a bright future. Chem. Soc. Rev., 2017, 46, 7021–7053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, Z. , Supramolecular Chemotherapy Based on the Host–Guest Complex of Lobaplatin–Cucurbit [7]urilACS Applied Bio Materials 2020 3 (4), 2449-2454. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jing, L.; Meng, Q.; Li, B.; Chen, R.; Sun, Z. ,Supramolecular Chemotherapy: Noncovalent Bond Synergy of Cucurbit [7]uril against Human Colorectal Tumor Cells Langmuir 2021 37 (31), 9547-9552. [CrossRef]

- Wang; Wang; Cen et al. GOx-assisted synthesis of pillar [5]arene based supramolecular polymeric nanoparticles for targeted/synergistic chemo-chemodynamic cancer therapy. J Nanobiotechnol 20, 33 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Yu G; Jie K, Huang F. Supramolecular Amphiphiles Based on Host-Guest Molecular Recognition Motifs. Chem Rev. 2015 Aug 12;115(15):7240-303. [CrossRef]

- EA, A.; JD, B.; XJ, L.; Rev, S.O.A.S.P.H.C.S. 2012;41:6195–214.

- Xiong Q; Cui M; Bai Y; Liu Y; Liu D, Song T. A supramolecular nanoparticle system based on β-cyclodextrin-conjugated poly-l-lysine and hyaluronic acid for co-delivery of gene and chemotherapy agent targeting hepatocellular carcinoma. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2017 Jul 1;155:93-103. [CrossRef]

- Singh P; Chen Y; Tyagi D; Wu L; Ren X; Feng J; Carrier A; Luan T; Tang Y; Zhang J, Zhang X. β-Cyclodextrin-grafted hyaluronic acid as a supramolecular polysaccharide carrier for cell-targeted drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2021 Jun 1;602:120602. [CrossRef]

- GN, I. ; Lunetti P; Gallo N; AR, C.; Fiermonte G; Dolce V, Capobianco L. Hyaluronic Acid: A Powerful Biomolecule with Wide-Ranging Applications-A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jun 18;24(12):10296. [CrossRef]

- RD, A. ; Manjoo A; Fierlinger A; Niazi F, Nicholls M. The mechanism of action for hyaluronic acid treatment in the osteoarthritic knee: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015 Oct 26;16:321. [CrossRef]

- Litwiniuk, M; Krejner, A; MS, S.; AR, G. Litwiniuk M; Krejner A; MS, S.; AR, G., Grzela T. Hyaluronic Acid in Inflammation and Tissue Regeneration. Wounds. 2016 Mar;28(3):78-88.

- Antoszewska; M. ; Sokolewicz; E.M.; Barańska-Rybak, W. Wide Use of Hyaluronic Acid in the Process of Wound Healing—A Rapid Review. Sci. Pharm. 2024, 92, 23. [CrossRef]

- Gagneja S; Capalash N, Sharma P. Hyaluronic acid as a tumor progression agent and a potential chemotherapeutic biomolecule against cancer: A review on its dual role. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024 Aug;275(Pt 2):133744. [CrossRef]

- Chang W; Chen L, Chen K. The bioengineering application of hyaluronic acid in tissue regeneration and repair. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024 Jun;270(Pt 2):132454. [CrossRef]

- Lu, P; Takai, K; VM, W. Lu P; Takai K; VM, W., Werb Z. Extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling in development and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011 Dec 1;3(12):a005058. [CrossRef]

- Caon I; Parnigoni A; Viola M; Karousou E; Passi A, Vigetti D. Cell Energy Metabolism and Hyaluronan Synthesis. J Histochem Cytochem. 2021 Jan;69(1):35-47. [CrossRef]

- Piperigkou Z; Kyriakopoulou K; Koutsakis C; Mastronikolis S, Karamanos NK. Key Matrix Remodeling Enzymes: Functions and Targeting in Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Mar 22;13(6):1441. [CrossRef]

- AG, T. ; Caon I; Franchi M; Piperigkou Z; Galesso D, Karamanos NK. Hyaluronan: molecular size-dependent signaling and biological functions in inflammation and cancer. FEBS J. 2019 Aug;286(15):2883-2908. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya M; Jariyal H, Srivastava A. Hyaluronic acid: More than a carrier, having an overpowering extracellular and intracellular impact on cancer. Carbohydr Polym. 2023 Oct 1;317:121081. [CrossRef]

- BJ, M. ; Tolg C; JB, M.; AC, N., Turley EA. RHAMM Is a Multifunctional Protein That Regulates Cancer Progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Sep 24;22(19):10313. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Tabanera E, Melero-Fernández de Mera RM, Alonso J. CD44 In Sarcomas: A Comprehensive Review and Future Perspectives. Front Oncol. 2022 Jun 17;12:909450. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, A; AR, E. Hosseini A; AR, E.; Mirzaei A; Babaheidarian P; Nekoufar S; Khademian N; Jamshidi K, Tavakoli-Yaraki M. The clinical significance of CD44v6 in malignant and benign primary bone tumors. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023 Jul 25;24(1):607. [CrossRef]

- Zhai P; Peng X; Li B; Liu Y; Sun H, Li X. The application of hyaluronic acid in bone regeneration. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020 ;151:1224-1239. 15 May. [CrossRef]

- Dovedytis; M. ; Liu; Z.J.; Bartlett, S.Hyaluronic acid and its biomedical applications: A review,Engineered Regeneration, 2020, 1, 102–113.

- Zamboni; Fernanda; Vieira; Sílvia; Reis; Rui L. & Oliveira; Joaquim & Collins; Maurice. (2018). The Potential of Hyaluronic acid in Immunoprotection and Immunomodulation: Chemistry, Processing and Function. Progress in Materials Science. 97. 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martincorena, I; Roshan, A; Gerstung, M; Ellis, P; Loo P, V.; McLaren, S; DC, W.; Fullam, A; LB, A.; JM, T.; Stebbings, L; Menzies, A; Widaa, S; MR, S.; PH, J. Martincorena I; Roshan A; Gerstung M; Ellis P; Loo P, V.; McLaren S; DC, W.; Fullam A; LB, A.; JM, T.; Stebbings L; Menzies A; Widaa S; MR, S.; PH, J., Campbell PJ. Tumor evolution. High burden and pervasive positive selection of somatic mutations in normal human skin. Science. 2015 ;348(6237):880-6. 22 May. [CrossRef]

- Rivera C, Venegas B. Histological and molecular aspects of oral squamous cell carcinoma (Review). Oncol Lett. 2014 Jul;8(1):7-11. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T; Chanmee, T; Hyaluronan, I.N.; Biomolecules, F. Kobayashi T; Chanmee T; Hyaluronan, I.N.; Biomolecules, F. 2020 Nov 7;10(11):1525. [CrossRef]

- Slevin, M; Krupinski, J; Gaffney, J; Matou, S; West, D; Delisser, H; RC, S. Slevin M; Krupinski J; Gaffney J; Matou S; West D; Delisser H; RC, S., Kumar S. Hyaluronan-mediated angiogenesis in vascular disease: uncovering RHAMM and CD44 receptor signaling pathways. Matrix Biol. 2007 Jan;26(1):58-68. [CrossRef]

- Caon; I. ; D’Angelo; M.L.; Bartolini; B.; Caravà; E.; Parnigoni; A.; Contino; F.; Cancemi; P.; Moretto; P.; Karamanos; N.K.; Passi; et al. The Secreted Protein C10orf118 Is a New Regulator of Hyaluronan Synthesis Involved in Tumour-Stroma Cross-Talk. Cancers 2021, 13, 1105.

- Sapudom; J. ; Müller; C.D.; Nguyen; K.-T.; Martin; S.; Anderegg; U.; Pompe, T. Matrix Remodeling and Hyaluronan Production by Myofibroblasts and Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in 3D Collagen Matrices. Gels 2020, 6, 33. [CrossRef]

- Vigetti, D; Genasetti, A; Karousou, E; Viola, M; Moretto, P; Clerici, M; Deleonibus, S; Luca G, D.; VC, H. Vigetti D; Genasetti A; Karousou E; Viola M; Moretto P; Clerici M; Deleonibus S; Luca G, D.; VC, H., Passi A. Proinflammatory cytokines induce hyaluronan synthesis and monocyte adhesion in human endothelial cells through hyaluronan synthase 2 (HAS2) and the nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB) pathway. J Biol Chem. 2010 Aug 6;285(32):24639-45. [CrossRef]

- JB, M. ; El-Ashry D; Hyaluronan, T.E.A., Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts and the Tumor Microenvironment in Malignant Progression. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2018 ;6:48. 8 May; Erratum in: Front Cell Dev Biol. 2018 Sep 24;6:112. [CrossRef]

- Mele, V; Sokol, L; VH, K.; Pfaff, D; MG, M.; Keller, I; Stefan, Z; Centeno, I; LM, T. Mele V; Sokol L; VH, K.; Pfaff D; MG, M.; Keller I; Stefan Z; Centeno I; LM, T.; Dawson H; Zlobec I; Iezzi G, Lugli A. The hyaluronan-mediated motility receptor RHAMM promotes growth, invasiveness and dissemination of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2017 Aug 3;8(41):70617-70629. [CrossRef]

- Shigeeda W; Shibazaki M; Yasuhira S; Masuda T; Tanita T; Kaneko Y; Sato T; Sekido Y, Maesawa C. Hyaluronic acid enhances cell migration and invasion via the YAP1/TAZ-RHAMM axis in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Oncotarget. 2017 Sep 8;8(55):93729-93740. [CrossRef]

- PR, D.-G.; EP, K. ; Donelan W; Miranda M; Doty A; O’Malley P; PL, C., Kusmartsev S. Detection of PD-L1-Expressing Myeloid Cell Clusters in the Hyaluronan-Enriched Stroma in Tumor Tissue and Tumor-Draining Lymph Nodes. J Immunol. 2022 Jun 15;208(12):2829-2836. [CrossRef]

- Chen C; Zhao S; Karnad A, Freeman JW. The biology and role of CD44 in cancer progression: therapeutic implications. J Hematol Oncol. 2018 ;11(1):64. 10 May. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz P; Schwärzler C, Günthert U. CD44 isoforms during differentiation and development. Bioessays. 1995 Jan;17(1):17-24. [CrossRef]

- Goodison, S; Urquidi, V; CD, T.D. Goodison S; Urquidi V; CD, T.D. 1999 Aug;52(4):189-96. [CrossRef]

- Lesley J; Hyman R, Kincade PW. CD44 and its interaction with extracellular matrix. Adv Immunol. 1993;54:271-335. [CrossRef]

- Uhlén, M; Fagerberg, L; BM, H.; Lindskog, C; Oksvold, P; Mardinoglu, A; Sivertsson, Å; Kampf, C; Sjöstedt, E; Asplund, A; Olsson, I; Edlund, K; Lundberg, E; Navani, S; CA, S.; Odeberg, J; Djureinovic, D; JO, T.; Hober, S; Alm, T; PH, E.; Berling, H; Tegel, H; Mulder, J; Rockberg, J; Nilsson, P; JM, S. Uhlén M; Fagerberg L; BM, H.; Lindskog C; Oksvold P; Mardinoglu A; Sivertsson Å; Kampf C; Sjöstedt E; Asplund A; Olsson I; Edlund K; Lundberg E; Navani S; CA, S.; Odeberg J; Djureinovic D; JO, T.; Hober S; Alm T; PH, E.; Berling H; Tegel H; Mulder J; Rockberg J; Nilsson P; JM, S.; Hamsten M; von Feilitzen K; Forsberg M; Persson L; Johansson F; Zwahlen M; von Heijne G; Nielsen J, Pontén F. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015 347(6220):1260419.

- LT, S. , Chellaiah MA. CD44: A Multifunctional Cell Surface Adhesion Receptor Is a Regulator of Progression and Metastasis of Cancer Cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2017 Mar 7;5:18. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y; Bai Z; Lan T; Fu C, Cheng P. CD44 and its implication in neoplastic diseases. MedComm (2020). 2024 ;5(6):e554. 23 May. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Q; Zhang M; Zhou F; Zhang L, Meng X. The Breast Cancer Stem Cells Traits and Drug Resistance. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Jan 28;11:599965. [CrossRef]

- Mesrati, H. ; M. ; Syafruddin; S.E.; Mohtar; M.A.; Syahir, A. CD44: A Multifunctional Mediator of Cancer Progression. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birzele, F; Voss, E; Nopora, A; Honold, K; Heil, F; Lohmann, S; Verheul, H; Tourneau C, L.; JP, D.; van Herpen, C; Mahalingam, D; AL, C. Birzele F; Voss E; Nopora A; Honold K; Heil F; Lohmann S; Verheul H; Tourneau C, L.; JP, D.; van Herpen C; Mahalingam D; AL, C.; Meresse V; Weigand S; Runza V, Cannarile M. CD44 Isoform Status Predicts Response to Treatment with Anti-CD44 Antibody in Cancer Patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2015 Jun 15;21(12):2753-62. [CrossRef]

- Wu S; Tan Y; Li F; Han Y; Zhang S, Lin X. CD44: a cancer stem cell marker and therapeutic target in leukemia treatment. Front Immunol. 2024 Apr 26;15:1354992. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C; MB, Y. Cheng C; MB, Y., Sharp PA. A positive feedback loop couples Ras activation and CD44 alternative splicing. Genes Dev. 2006 Jul 1;20(13):1715-20. [CrossRef]

- AL, H.-T.; NJ, R.; SV, O.; JT, D. , Crompton T. Beta-selection: abundance of TCRbeta-/gammadelta- CD44- CD25- (DN4) cells in the foetal thymus. Eur J Immunol. 2007 Feb;37(2):487-500. [CrossRef]

- Stout, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; R., D.; Suttles, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; CD, J.T.C.B.T. Stout; R. D.; Suttles; CD, J.T.C.B.T. “memory” phenotype display characteristics of activated cells in G1 stage of cell cycle. Cellular Immunology, 1992., 141(2), 433–443. [CrossRef]

- Galluzzo, E; Albi, N; Fiorucci, S; Merigiola, C; Ruggeri, L; Tosti, A; CE, G. Galluzzo E; Albi N; Fiorucci S; Merigiola C; Ruggeri L; Tosti A; CE, G., Velardi A. Involvement of CD44 variant isoforms in hyaluronate adhesion by human activated T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1995 Oct;25(10):2932-9. [CrossRef]

- Schwärzler C; Oliferenko S, Günthert U. Variant isoforms of CD44 are required in early thymocyte development. Eur J Immunol. 2001 Oct;31(10):2997-3005. [CrossRef]

- Günthert U; Hofmann M; Rudy W; Reber S; Zöller M; Haussmann I; Matzku S; Wenzel A; Ponta H, Herrlich P. A new variant of glycoprotein CD44 confers metastatic potential to rat carcinoma cells. Cell. 1991 Apr 5;65(1):13-24. [CrossRef]

- YJ, L.; PS, Y. ; Li J, Jia JF. Expression and significance of CD44s, CD44v6, and nm23 mRNA in human cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2005 Nov 14;11(42):6601-6. [CrossRef]

- Todaro, M; Gaggianesi, M; Catalano, V; Benfante, A; Iovino, F; Biffoni, M; Apuzzo, T; Sperduti, I; Volpe, S; Cocorullo, G; Gulotta, G; Dieli, F; Maria R, D. Todaro M; Gaggianesi M; Catalano V; Benfante A; Iovino F; Biffoni M; Apuzzo T; Sperduti I; Volpe S; Cocorullo G; Gulotta G; Dieli F; Maria R, D., Stassi G. CD44v6 is a marker of constitutive and reprogrammed cancer stem cells driving colon cancer metastasis. Cell Stem Cell. 2014 Mar 6;14(3):342-56. [CrossRef]

- MS, S.; YJ, G. , Stamenkovic I. Distinct effects of two CD44 isoforms on tumor growth in vivo. J Exp Med. 1991 Oct 1;174(4):859-66. [CrossRef]

- MH, D.; PJ, S.; NF, R.E. , van der Valk MA, van Rijthoven EA, Roos E. Targeted disruption of CD44 in MDAY-D2 lymphosarcoma cells has no effect on subcutaneous growth or metastatic capacity. J Cell Biol. 1995 Dec;131(6 Pt 2):1849-55. [CrossRef]

- GF, W.; RT, B. ; Ilagan J; Cantor H; Schmits R, Mak TW. Absence of the CD44 gene prevents sarcoma metastasis. Cancer Res. 2002 Apr 15;62(8):2281-6.

- Yan Y; Zuo X, Wei D. Concise Review: Emerging Role of CD44 in Cancer Stem Cells: A Promising Biomarker and Therapeutic Target. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015 Sep;4(9):1033-43. [CrossRef]

- Morath, I; TN, H. Morath I; TN, H., Orian-Rousseau V. CD44: More than a mere stem cell marker. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2016 Dec;81(Pt A):166-173. [CrossRef]

- YJ, S.; HM, L.; YW, C.; GY, C. , Lee JL. Direct reprogramming of stem cell properties in colon cancer cells by CD44. EMBO J. 2011 Jun 24;30(15):3186-99. [CrossRef]

- Todaro, M; Gaggianesi, M; Catalano, V; Benfante, A; Iovino, F; Biffoni, M; Apuzzo, T; Sperduti, I; Volpe, S; Cocorullo, G; Gulotta, G; Dieli, F; Maria R, D. Todaro M; Gaggianesi M; Catalano V; Benfante A; Iovino F; Biffoni M; Apuzzo T; Sperduti I; Volpe S; Cocorullo G; Gulotta G; Dieli F; Maria R, D., Stassi G. CD44v6 is a marker of constitutive and reprogrammed cancer stem cells driving colon cancer metastasis. Cell Stem Cell. 2014 Mar 6;14(3):342-56. [CrossRef]

- WM, L. ; Teng E; HS, C.; KA, L.; AY, T.; Salto-Tellez M; Shabbir A; JB, S., Chan SL. CD44v8-10 is a cancer-specific marker for gastric cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2014 ;74(9):2630-41. 1 May. [CrossRef]

- LY, B. ; Wong G; Earle C, Chen L. Hyaluronan-CD44v3 interaction with Oct4-Sox2-Nanog promotes miR-302 expression leading to self-renewal, clonal formation, and cisplatin resistance in cancer stem cells from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Biol Chem. 2012 Sep 21;287(39):32800-24. [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, M; Quintana, E; ER, F. Shackleton M; Quintana E; ER, F., Morrison SJ. Heterogeneity in cancer: cancer stem cells versus clonal evolution. Cell. 2009 Sep 4;138(5):822-9. [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, C; Hoare, K; Owens, R; HP, H.; Hook, M; Moore, D; Cripps, V; Austen, L; DM, N. Hardwick C; Hoare K; Owens R; HP, H.; Hook M; Moore D; Cripps V; Austen L; DM, N., Turley EA. Molecular cloning of a novel hyaluronan receptor that mediates tumor cell motility. J Cell Biol. 1992 Jun;117(6):1343-50. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Q; Liu X; Lv M; Sun E; Lu X, Lu C. Genes That Predict Poor Prognosis in Breast Cancer via Bioinformatical Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2021 Apr 17;2021:6649660. [CrossRef]

- Katz, BZ. Adhesion molecules--The lifelines of multiple myeloma cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2010 Jun;20(3):186-95. [CrossRef]

- ST, B.; MS, H. ; Kumar A; Champeaux A; SV, N., Kruk PA. Increased RHAMM expression relates to ovarian cancer progression. J Ovarian Res. 2017 Sep 27;10(1):66. [CrossRef]

- Assmann, V; CE, G.; Poulsom, R; Ryder, K; IR, H. Assmann V; CE, G.; Poulsom R; Ryder K; IR, H., Hanby AM. The pattern of expression of the microtubule-binding protein RHAMM/IHABP in mammary carcinoma suggests a role in the invasive behaviour of tumour cells. J Pathol. 2001 Sep;195(2):191-6. [CrossRef]

- Minato A; Kudo Y; Noguchi H; Kohi S; Hasegawa Y; Sato N; Hirata K, Fujimoto N. Receptor for Hyaluronic Acid-mediated Motility (RHAMM) Is Associated With Prostate Cancer Migration and Poor Prognosis. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2023 Mar-Apr;20(2):203-210. [CrossRef]

- XB, C. ; Sato N; Kohi S; Koga A, Hirata K. Receptor for Hyaluronic Acid-Mediated Motility is Associated with Poor Survival in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. J Cancer. 2015 Sep 3;6(11):1093-8. [CrossRef]

- EA, T.; PW, N. , Bourguignon LY. Signaling properties of hyaluronan receptors. J Biol Chem. 2002 Feb 15;277(7):4589-92. [CrossRef]

- Lévy P; Vidaud D; Leroy K; Laurendeau I; Wechsler J; Bolasco G; Parfait B; Wolkenstein P; Vidaud M, Bièche I. Molecular profiling of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors associated with neurofibromatosis type 1, based on large-scale real-time RT-PCR. Mol Cancer. 2004 Jul 15;3:20. [CrossRef]

- AK, E.; AH, R.; LE, R.; EV, N.; BM, M. , Schwertfeger KL. LYVE-1-expressing Macrophages Modulate the Hyaluronan-containing Extracellular Matrix in the Mammary Stroma and Contribute to Mammary Tumor Growth. Cancer Res Commun. 2024 ;4(5):1380-1397. 31 May. [CrossRef]

- Tian X; Azpurua J; Hine C; Vaidya A; Myakishev-Rempel M; Ablaeva J; Mao Z; Nevo E; Gorbunova V, Seluanov A. High-molecular-mass hyaluronan mediates the cancer resistance of the naked mole rat. Nature. 2013 Jul 18;499(7458):346-9. [CrossRef]

- C. -P.; Cai; X.-Y.; Chen; S.-L.; Yu; H.-W.; Fang; Y.; Feng; X.-C.; Zhang; L.-M.; Li, C.-Y. Hyaluronic Acid-Based Nanocarriers for Anticancer Drug Delivery. Polymers 2023, 15, 2317. [CrossRef]

- Gholamali I; TT, V. ; SH, J.; SH, P., Lim KT. Exploring the Progress of Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogels: Synthesis, Characteristics, and Wide-Ranging Applications. Materials (Basel). 2024 May 18;17(10):2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triggs-Raine B, Natowicz MR. Biology of hyaluronan: Insights from genetic disorders of hyaluronan metabolism. World J Biol Chem. 2015 Aug 26;6(3):110-20. [CrossRef]

- Bayer, IS. Hyaluronic Acid and Controlled Release: A Review. Molecules. 2020 Jun 6;25(11):2649. [CrossRef]

- AN, B.; NV, D. , Skorik YA. Chemical modification of hyaluronic acid as a strategy for the development of advanced drug delivery systems. Carbohydr Polym. 2024 Aug 1;337:122145. [CrossRef]

- Xiong Q; Cui M; Bai Y; Liu Y; Liu D, Song T. A supramolecular nanoparticle system based on β-cyclodextrin-conjugated poly-l-lysine and hyaluronic acid for co-delivery of gene and chemotherapy agent targeting hepatocellular carcinoma. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2017 Jul 1;155:93-103. [CrossRef]

- Singh P; Chen Y; Tyagi D; Wu L; Ren X; Feng J; Carrier A; Luan T; Tang Y; Zhang J, Zhang X. β-Cyclodextrin-grafted hyaluronic acid as a supramolecular polysaccharide carrier for cell-targeted drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2021 Jun 1;602:120602. [CrossRef]

- KY, C. ; Saravanakumar G; JH, P., Park K. Hyaluronic acid-based nanocarriers for intracellular targeting: interfacial interactions with proteins in cancer. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2012;99:82-94. [CrossRef]

- Salari N; Mansouri K; Valipour E; Abam F; Jaymand M; Rasoulpoor S; Dokaneheifard S, Mohammadi M. Hyaluronic acid-based drug nanocarriers as a novel drug delivery system for cancer chemotherapy: A systematic review. Daru. 2021 Dec;29(2):439-447. [CrossRef]

- YF, D. ; Xu X; Li J; Wang Z; Luo J; GSP, M.; Li S, Wang R. Hyaluronic acid-based supramolecular nanomedicine with optimized ratio of oxaliplatin/chlorin e6 for combined chemotherapy and O2-economized photodynamic therapy. Acta Biomater. 2023 Jul 1;164:397-406. [CrossRef]

- Mansoori-Kermani, A; Khalighi, S; Akbarzadeh, I; FR, N.; Motasadizadeh, H; Mahdieh, A; Jahed, V; Abdinezhad, M; Rahbariasr, N; Hosseini, M; Ahmadkhani, N; Panahi, B; Fatahi, Y; Mozafari, M; AP, K. Mansoori-Kermani A; Khalighi S; Akbarzadeh I; FR, N.; Motasadizadeh H; Mahdieh A; Jahed V; Abdinezhad M; Rahbariasr N; Hosseini M; Ahmadkhani N; Panahi B; Fatahi Y; Mozafari M; AP, K., Mostafavi E. Engineered hyaluronic acid-decorated niosomal nanoparticles for controlled and targeted delivery of epirubicin to treat breast cancer. Mater Today Bio. 2022 Jul 6;16:100349. [CrossRef]

- SS, M. ; Laomeephol C; Thamnium S; Chamni S, Luckanagul JA. Hyaluronic Acid Nanogels: A Promising Platform for Therapeutic and Theranostic Applications. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Nov 25;15(12):2671. [CrossRef]

- C. -P.; Cai; X.-Y.; Chen; S.-L.; Yu; H.-W.; Fang; Y.; Feng; X.-C.; Zhang; L.-M.; Li, C.-Y. Hyaluronic Acid-Based Nanocarriers for Anticancer Drug Delivery. Polymers 2023, 15, 2317. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S; SA, L. Lee S; SA, L.; Shinn J, Lee Y. Hyaluronic Acid-Bilirubin Nanoparticles as a Tumor Microenvironment Reactive Oxygen Species-Responsive Nanomedicine for Targeted Cancer Therapy. Int J Nanomedicine. 2024 ;19:4893-4906. 27 May. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J; Deng M; Xu C; Li D; Yan X; Gu Y; Zhong M; Gao H; Liu Y; Zhang J; Qu X, Zhang J. Dual-Prodrug-Based Hyaluronic Acid Nanoplatform Provides Cascade-Boosted Drug Delivery for Oxidative Stress-Enhanced Chemotherapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2024 Sep 25;16(38):50459-50473. [CrossRef]

- Hu D; Mezghrani O; Zhang L; Chen Y; Ke X, Ci T. GE11 peptide modified and reduction-responsive hyaluronic acid-based nanoparticles induced higher efficacy of doxorubicin for breast carcinoma therapy. Int J Nanomedicine. 2016 Oct 7;11:5125-5147. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y; Qiao L; Zhang S; Wan G; Chen B; Zhou P; Zhang N, Wang Y. Dual pH-responsive multifunctional nanoparticles for targeted treatment of breast cancer by combining immunotherapy and chemotherapy. Acta Biomater. 2018 Jan 15;66:310-324. [CrossRef]

- CF, M. ; Shen J; Liang J; HS, Z.; Xiong Y; YH, W., Li F. Targeted drug delivery for tumor therapy inside the bone marrow. Biomaterials. 2018 Feb;155:191-202. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y; Lin W, Zhu L. Targeted Drug Delivery for the Treatment of Blood Cancers. Molecules. 2022 Feb 15;27(4):1310. [CrossRef]

- Swami, A.; Reagan, M.R.; Basto, P.; Mishima, Y.; Kamaly, N.; Glavey, S.; Zhang, S.; Moschetta, M.; Seevaratnam, D.; Zhang, Y. , et al. Engineered nanomedicine for myeloma and bone microenvironment targeting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:10287–10292. [CrossRef]

- HS, C.; BS, K. ; Yoon S; SO, O., Lee D. Leukemic Stem Cells and Hematological Malignancies. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jun 17;25(12):6639. [CrossRef]

- Hertweck MK, Erdfelder F, Kreuzer KA. CD44 in hematological neoplasias. Ann Hematol. 2011 May;90(5):493-508. [CrossRef]

- NI, K. ; Cisterne A; Devidas M; Shuster J; SP, H.; PJ, S.; KF, B.; CD, B.L.J.E.O.; but not CD44v6, predicts relapse in children with B cell progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia lacking adverse or favorable genetics. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008 Apr;49(4):710-8. [CrossRef]

- Quéré; Andradottir; Brun et al. High levels of the adhesion molecule CD44 on leukemic cells generate acute myeloid leukemia relapse after withdrawal of the initial transforming event. Leukemia 25, 515–526 (2011). [CrossRef]

- JC, G. ; Bayer E; Yu X; JM, L.; JP, H.; Tesanovic S; Härzschel A; Auer G; Rieß T; Salmhofer A; Szenes E; Haslauer T; Durand-Onayli V; Ramspacher A; SP, P.; Artinger M; Zaborsky N; Chigaev A; Aberger F; Neureiter D; Pleyer L; DF, L.; Orian-Rousseau V; Greil R, Hartmann TN. CD44 engagement enhances acute myeloid leukemia cell adhesion to the bone marrow microenvironment by increasing VLA-4 avidity. Haematologica. 2021 Aug 1;106(8):2102-2113. [CrossRef]

- LVC, M.; EP, N.; FG, A.; FV, D.S.-B.; MB, M. ; Terra-Granado E, Pombo-de-Oliveira MS. CD44 Expression Profile Varies According to Maturational Subtypes and Molecular Profiles of Pediatric T-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Front Oncol. 2018 Oct 31;8:488. [CrossRef]

- Piya; Yang; Bhattacharya et al. Targeting the NOTCH1-MYC-CD44 axis in leukemia-initiating cells in T-ALL. Leukemia 36, 1261–1273 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Jiang; Y. ; Lin; W.; Zhu, L. Targeted Drug Delivery for the Treatment of Blood Cancers. Molecules 2022, 27, 1310. [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.Y.; Correa, S.; Min, J.; Li, J.; Roy, S.; Laccetti, K.H.; Dreaden, E.; Kong, S.; Heo, R.; Roh, Y.H. , et al. Binary Targeting of siRNA to Hematologic Cancer Cells In Vivo using Layer-by-Layer Nanoparticles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019;29:1900018. [CrossRef]

- Kwak, E; Kim, T; Yang, K; YM, K.; HS, H.; KH, P.; KY, C. Kwak E; Kim T; Yang K; YM, K.; HS, H.; KH, P.; KY, C., Roh YH. Surface-Functionalized Polymeric siRNA Nanoparticles for Tunable Targeting and Intracellular Delivery to Hematologic Cancer Cells. Biomacromolecules. 2022 Jun 13;23(6):2255-2263. [CrossRef]

- Zhong Y; Meng F; Deng C; Mao X, Zhong Z. Targeted inhibition of human hematological cancers in vivo by doxorubicin encapsulated in smart lipoic acid-crosslinked hyaluronic acid nanoparticles. Drug Deliv. 2017 Nov;24(1):1482-1490. [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S; Aalhate, M; Chatterjee, E; Singh, H; Sharma, A; Maji, I; Gupta, U; SK, G. Mahajan S; Aalhate M; Chatterjee E; Singh H; Sharma A; Maji I; Gupta U; SK, G., Singh PK. Harnessing the targeting potential of hyaluronic acid for augmented anticancer activity and safety of duvelisib-loaded nanoparticles in hematological malignancies. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024 Oct 18;282(Pt 1):136600. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, et al. Anti-leukemia activity of hyaluronic acid coated silver nanoparticles for selective targeting to leukemic cells. J Biomater Tissue Eng. 2018;8(6):906–910. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).