Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

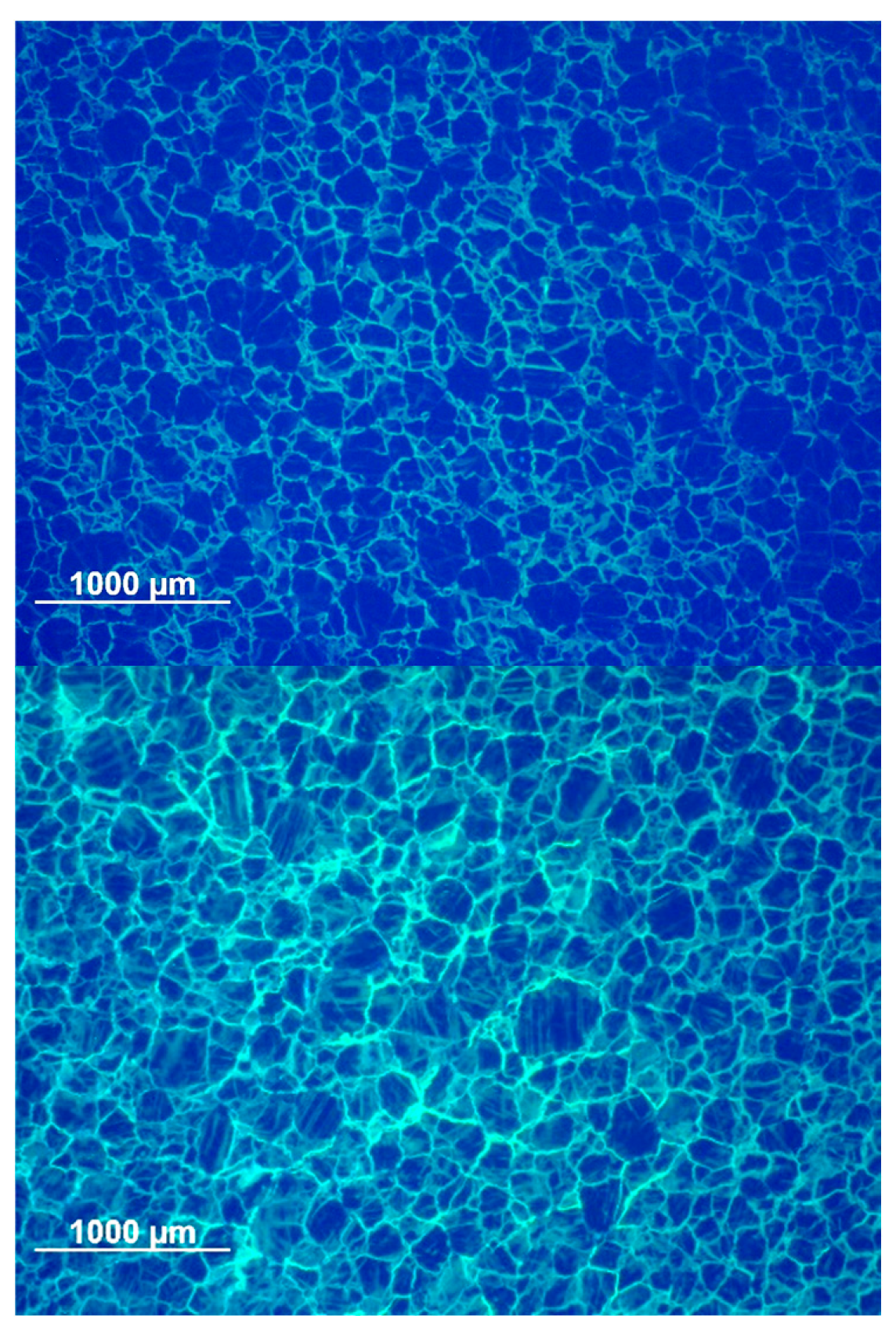

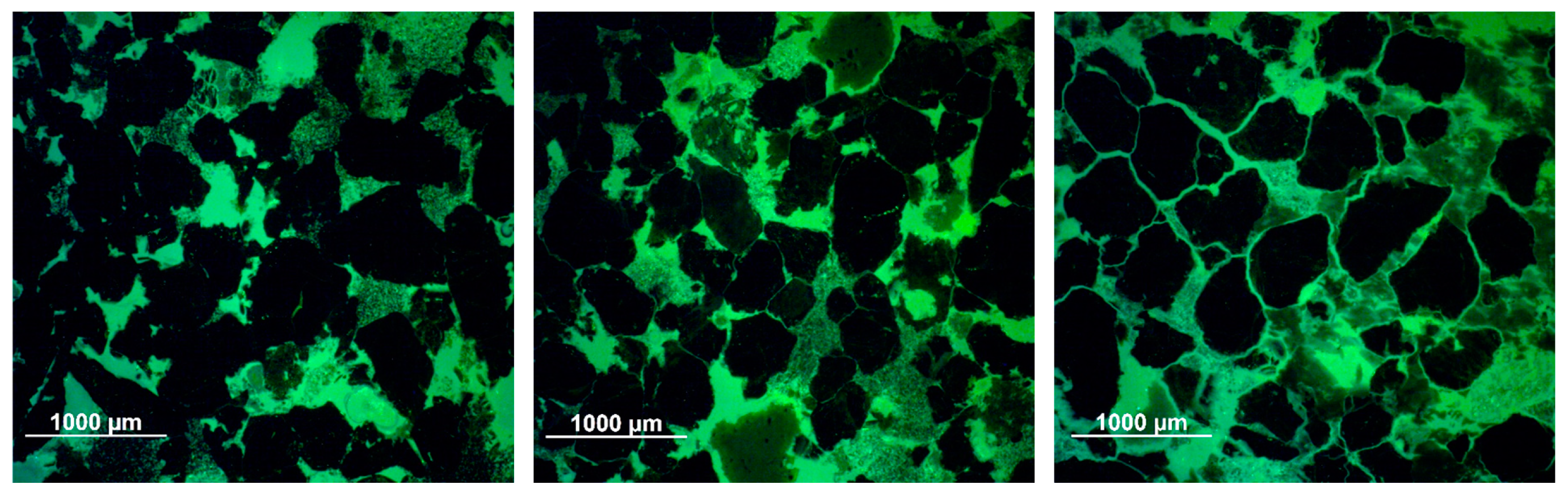

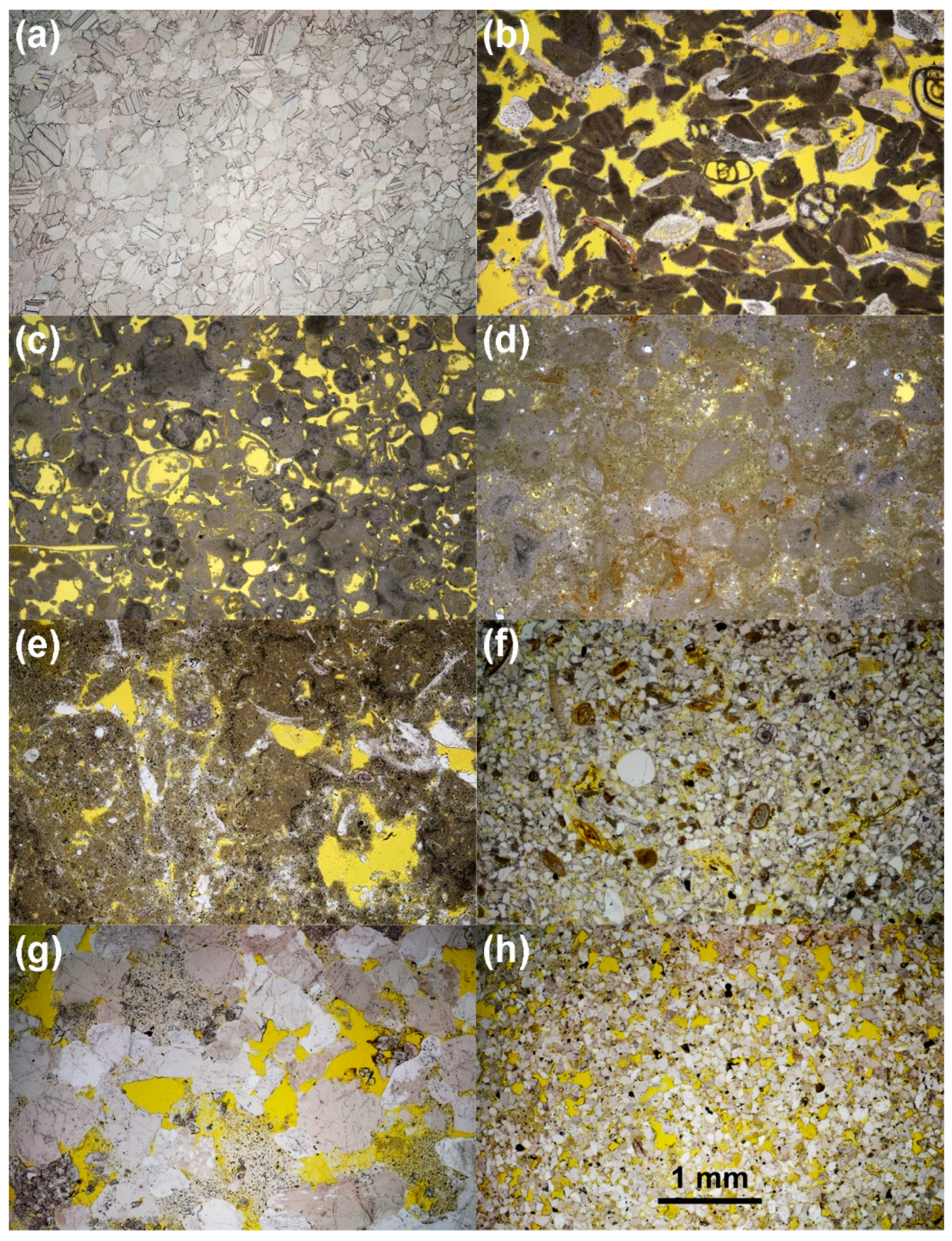

2.1. Petrographic Characterisation of the Lithotypes

2.2. Calcination

2.3. Analytical Techniques

3. Results and Discussion

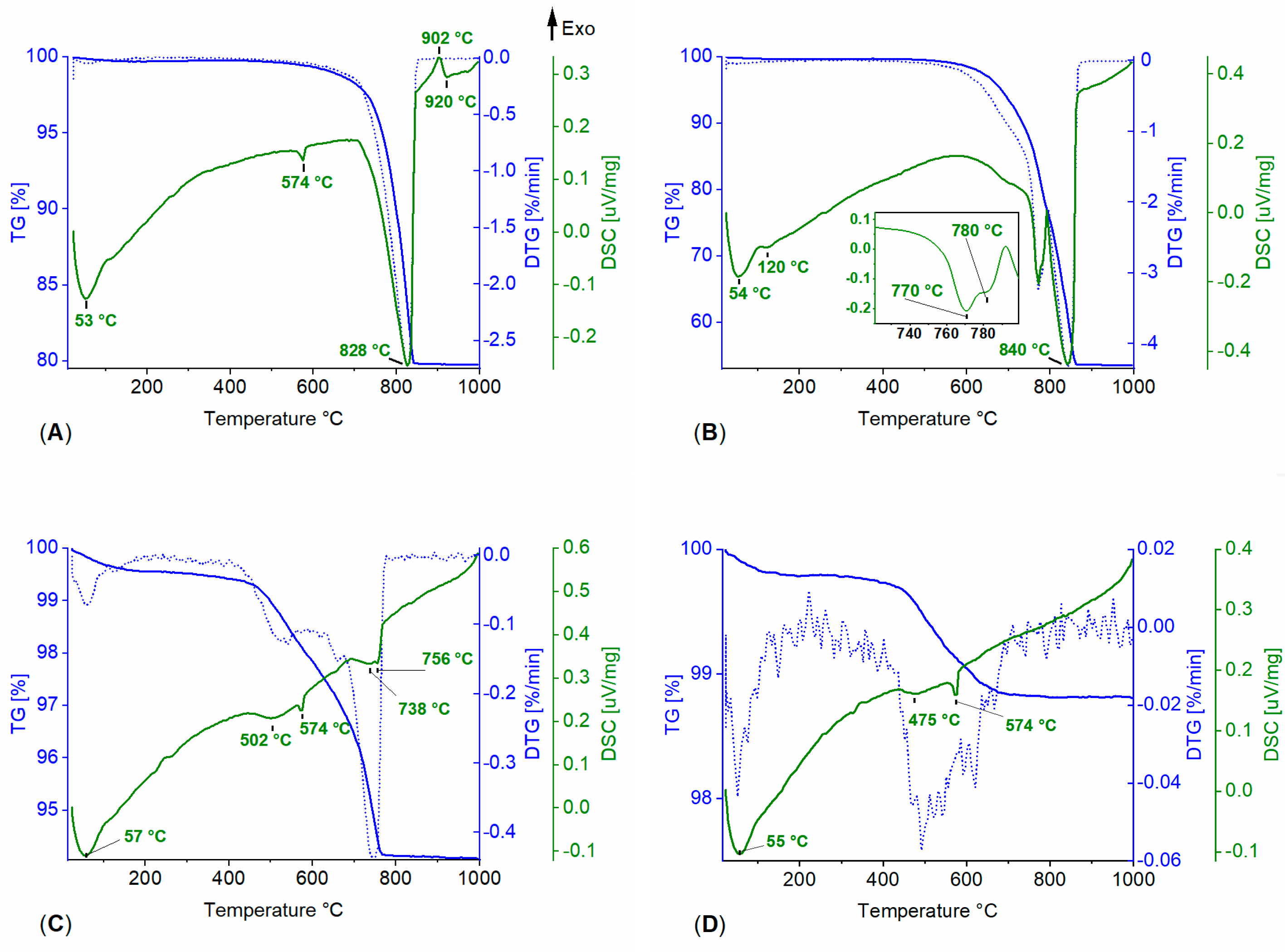

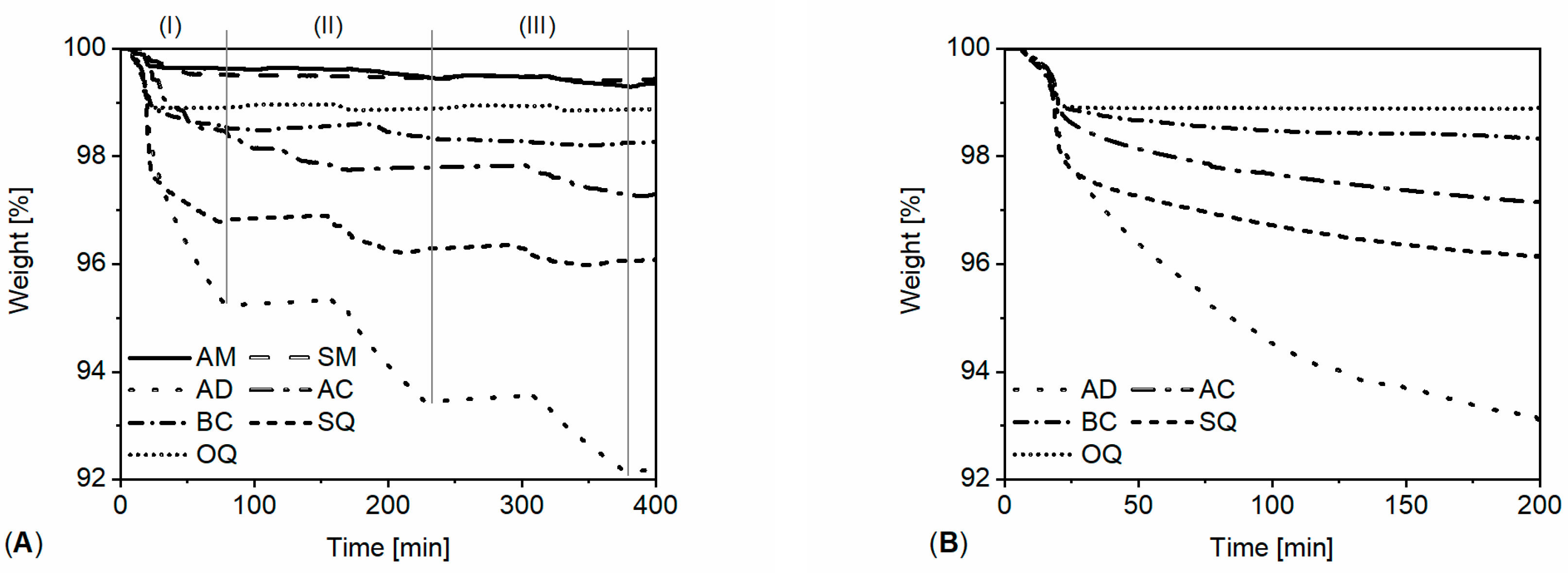

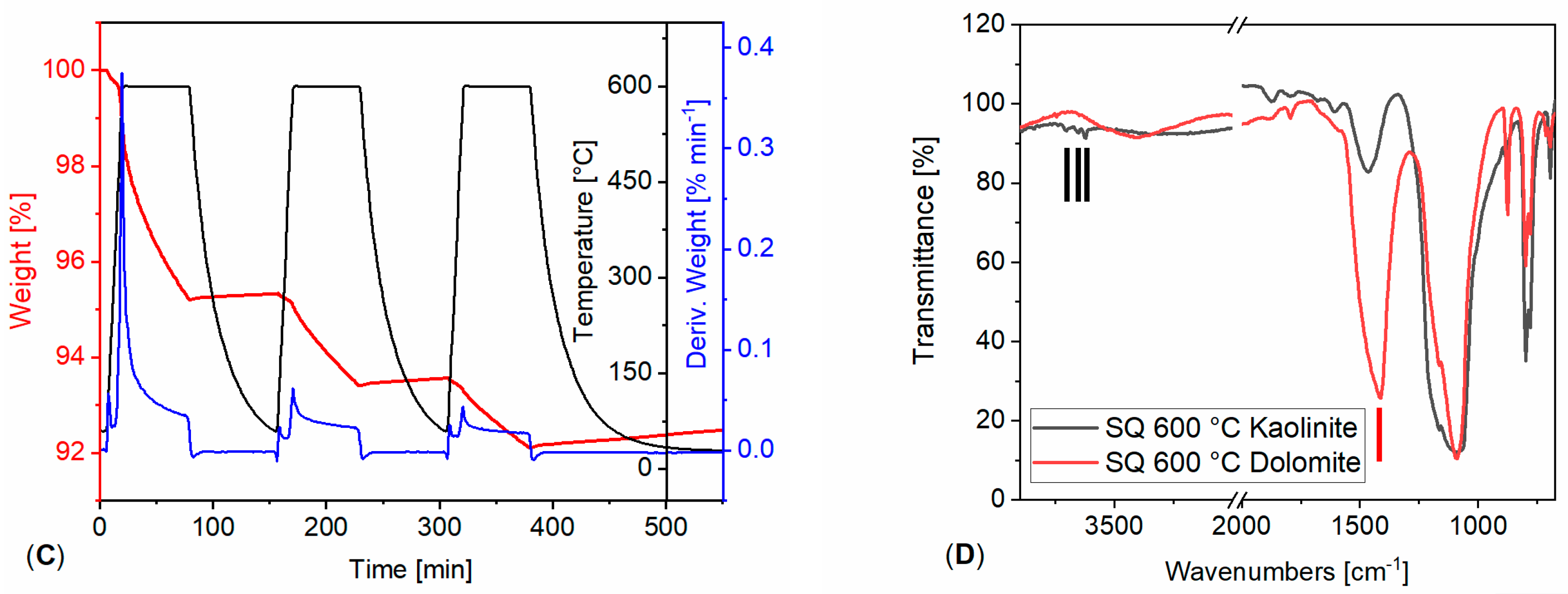

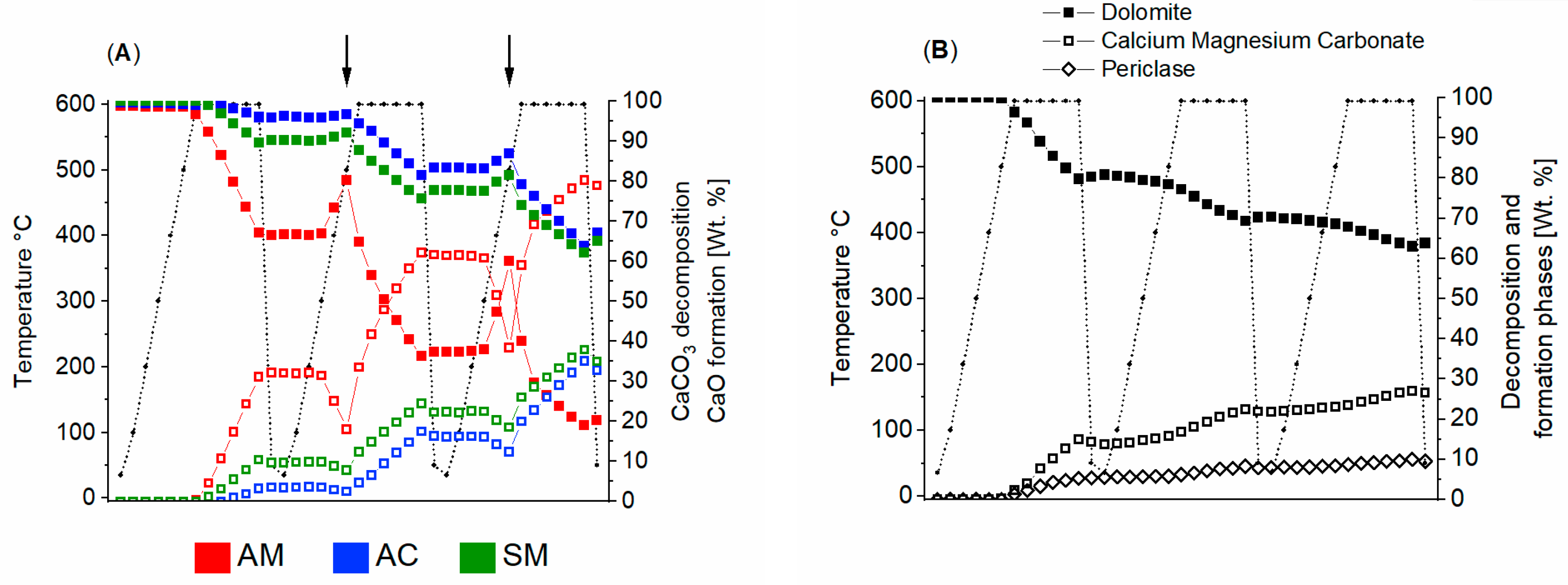

3.1. Powdered Sample Analysis: Simultaneous Thermal Analysis, Cyclic Thermal Gravimetric Analysis and Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

3.2.. Solid Sample Analysis: In-Situ X-Ray Diffraction, Colour Measurements and Microscopy

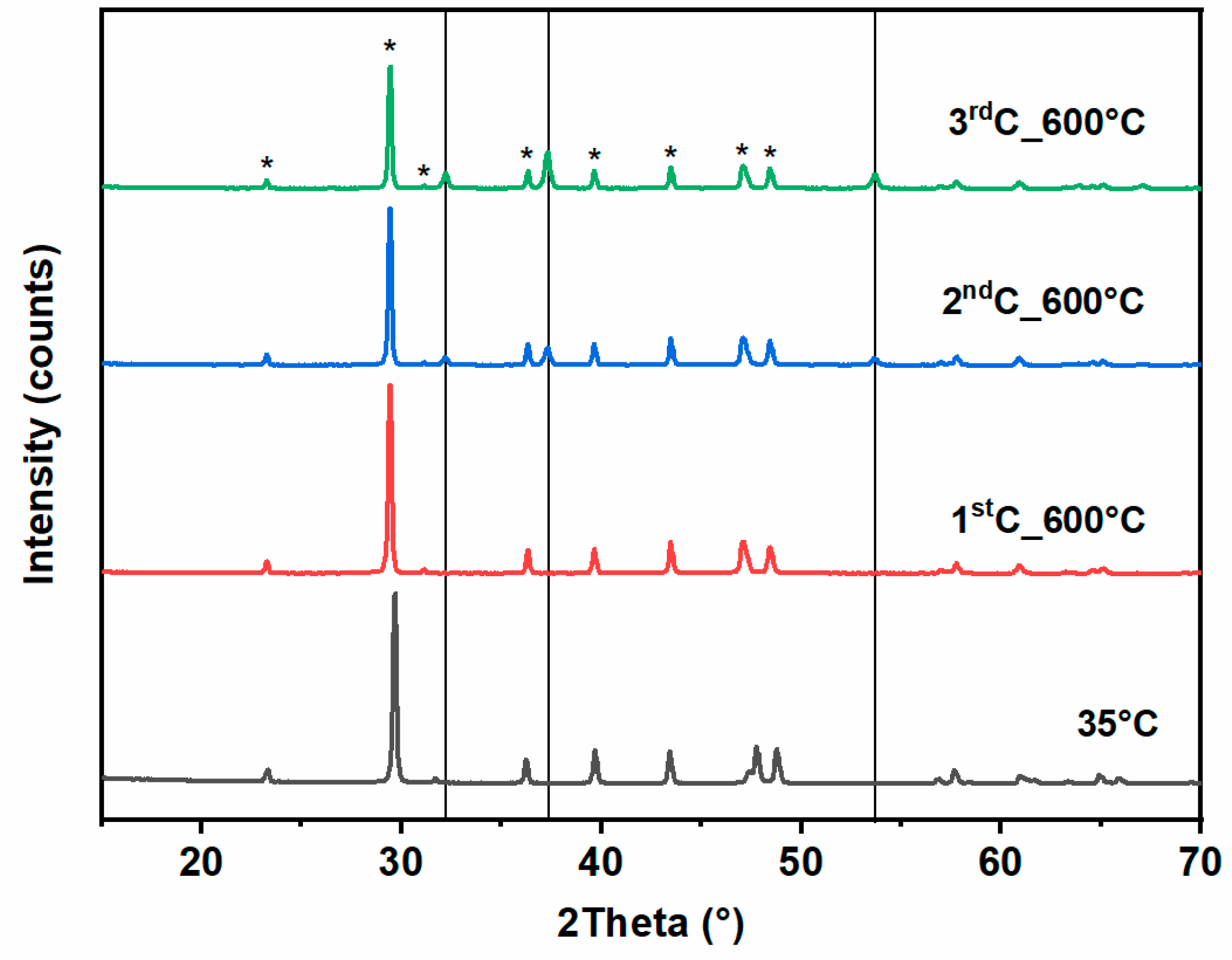

3.2.1. X-Ray Diffraction

3.2.2. Colour Measurements

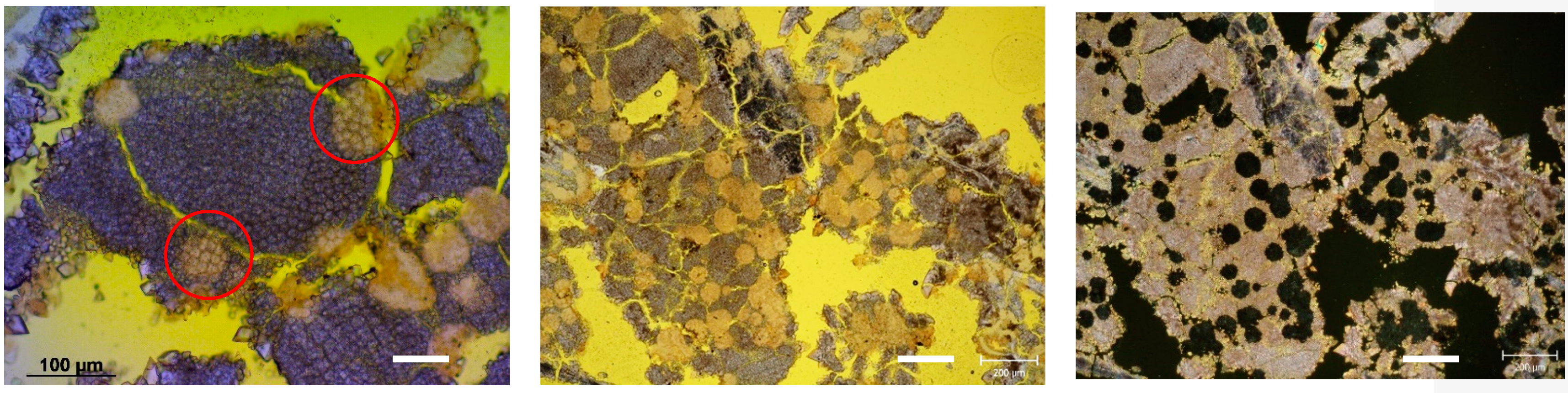

3.2.3. Optical Microscopy

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Gomez-Heras M, McCabe S, Smith BJ, Fort R. Impacts of Fire on Stone-Built Heritage. Journal of Architectural Conservation 2009, 15, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlock M, Paya-Zaforteza I, Kodur V, Gu L. Fire hazard in bridges: Review, assessment and repair strategies. Engineering Structures 2012, 35, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazzoler JdS, Vieira GL, Teles CR, Degen MK, Teixeira RA. Investigation of the potential use of waste from ornamental stone processing after heat treatment for the production of cement-based paste. Constr Build Mater 2018, 177, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang C-S, Cui Y-J, Tang A-M, Shi B. Experiment evidence on the temperature dependence of desiccation cracking behavior of clayey soils. Eng Geol 2010, 114, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritan L, Nodari L, Mazzoli C, Milano A, Russo U. Influence of firing conditions on ceramic products: Experimental study on clay rich in organic matter. Applied Clay Science 2006, 31, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerantola V, Bykova E, Kupenko I, Merlini M, Ismailova L, McCammon C, Bykov M, Chumakov AI, Petitgirard S, Kantor I, Svitlyk V, Jacobs J, Hanfland M, Mezouar M, Prescher C, Ruffer R, Prakapenka VB, Dubrovinsky L. Stability of iron-bearing carbonates in the deep Earth's interior. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 15960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjurjo-Sánchez J, Gomez-Heras M, Fort R, Alvarez de Buergo M, Izquierdo Benito R, Bru MA. Dating fires and estimating the temperature attained on stone surfaces. The case of Ciudad de Vascos (Spain). Microchemical Journal 2016, 127, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatta T, Gregori E, Marini F, Tomassetti M, Visco G, Campanella L. New approach to the differentiation of marble samples using thermal analysis and chemometrics in order to identify provenance. Chemistry Central Journal 2014, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao C, Zhang Y, Wang C-C, Hou M, Li A (2019) Recent progress in instrumental techniques for architectural heritage materials. Herit Sci 7 (1). [CrossRef]

- Tretiach M, Bertuzzi S, Candotto Carniel F. Heat shock treatments: a new safe approach against lichen growth on outdoor stone surfaces. Environ Sci Technol 2012, 46, 6851–6859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoni E, Sassoni E, Scherer GW, Naidu S. Artificial weathering of stone by heating. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2013, 14, E85–E93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban M, De Kock T, Ott F, Barone G, Rohatsch A, Raneri S. Neutron Radiography Study of Laboratory Ageing and Treatment Applications with Stone Consolidants. Neutron Radiography Study of Laboratory Ageing and Treatment Applications with Stone Consolidants. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho E, Mendes M, Dionisio A. 3D imaging of P-waves velocity as a tool for evaluation of heat induced limestone decay. Constr Build Mater 2017, 135, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozguven A, Ozcelik Y. Effects of high temperature on physico-mechanical properties of Turkish natural building stones. Eng Geol 2014, 183, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian H, Kempka T, Xu N-X, Ziegler M. Physical Properties of Sandstones After High Temperature Treatment. Rock Mech Rock Eng 2012, 45, 1113–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Frühwirt T, Konietzky H (2020) Influence of repeated heating on physical-mechanical properties and damage evolution of granite. Int J Rock Mech Min. [CrossRef]

- Vagnon F, Colombero C, Colombo F, Comina C, Ferrero AM, Mandrone G, Vinciguerra SC. Effects of thermal treatment on physical and mechanical properties of Valdieri Marble - NW Italy. Int J Rock Mech Min 2019, 116, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe S, Smith BJ, Warke PA. Exploitation of inherited weakness in fire-damaged building sandstone: the ‘fatiguing’ of ‘shocked’ stone. Eng Geol 2010, 115, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delegou ET, Apostolopoulou M, Ntoutsi I, Thoma M, Keramidas V, Papatrechas C, Economou G, Moropoulou A. The Effect of Fire on Building Materials: The Case-Study of the Varnakova Monastery Cells in Central Greece. Heritage 2019, 2, 1233–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenholtz JL, Smith DT. Linear thermal expansion of calcite, var. Iceland spar, and Yule Marble. American Mineralogist: Journal of Earth and Planetary Materials 1949, 34, 846–854. [Google Scholar]

- Martinho E, Dionísio A. Assessment Techniques for Studying the Effects of Fire on Stone Materials: A Literature Review. International Journal of Architectural Heritage 2018, 14, 275–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajpál M, Török A. Mineralogical and colour changes of quartz sandstones by heat. Environ Geol 2004, 46, 311–322. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Ibáñez V, Benavente D, Hidalgo Signes C, Tomás R, Garrido ME (2020) Temperature-Induced Explosive Behaviour and Thermo-Chemical Damage on Pyrite-Bearing Limestones: Causes and Mechanisms. Rock Mech Rock Eng. [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, E. The influence of thermal treatment on properties of kaolin. Hemijska industrija 2016, 70, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Liu X, Hu Y. Investigation of the thermal behaviour and decomposition kinetics of kaolinite. Clay Minerals 2018, 50, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartlieb P, Toifl M, Kuchar F, Meisels R, Antretter T. Thermo-physical properties of selected hard rocks and their relation to microwave-assisted comminution. Minerals Engineering 2016, 91, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney PJ (1994) Structure and chemistry of the low-pressure silica polymorphs. In: Silica: physical behavior, geochemistry, and materials applications.

- Chakrabarti B, Yates T, Lewry A. Effect of fire damage on natural stonework in buildings. Constr Build Mater 1996, 10, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristóf-Makó É, Juhász A. The effect of mechanical treatment on the crystal structure and thermal decomposition of dolomite. Thermochimica Acta 1999, 342, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Aza AH, Rodríguez MA, Rodríguez JL, De Aza S, Pena P, Convert P, Hansen T, Turrillas X. Decomposition of dolomite monitored by neutron thermodiffractometry. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2002, 85, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Navarro C, Ruiz-Agudo E, Luque A, Rodriguez-Navarro AB, Ortega-Huertas M. Thermal decomposition of calcite: Mechanisms of formation and textural evolution of CaO nanocrystals. American Mineralogist 2009, 94, 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahraki B, Mehrabi B, Gholizadeh K, Mohammadinasab M. Thermal behavior of calcite as an expansive agent. Journal of Mining and Metallurgy B: Metallurgy 2011, 47, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Navarro C, Kudlacz K, Ruiz-Agudo E. The mechanism of thermal decomposition of dolomite: New insights from 2D-XRD and TEM analyses. American Mineralogist 2012, 97, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde JM, Perejon A, Medina S, Perez-Maqueda LA. Thermal decomposition of dolomite under CO2: insights from TGA and in-situ XRD analysis. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2015, 17, 30162–30176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh R, Sharp J, Wilburn F. The thermal decomposition of dolomite. Thermochimica Acta 1990, 165, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieslinger A (1932) Zerstörungen an Steinbauten: ihre Ursachen und ihre Abwehr. F.

- Biró A, Hlavička V, Lublóy É. Effect of fire-related temperatures on natural stones. Constr Build Mater 2019, 212, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praticò Y, Ochsendorf J, Holzer S, Flatt RJ. Post-fire restoration of historic buildings and implications for Notre-Dame de Paris. Nature Materials 2020, 19, 817–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegesmund S, Snethlage R (2011) Stone in architecture: properties, durability.

- Ban M, Baragona A, Ghaffari E, Weber J, Rohatsch A (2016) Artificial aging techniques on various lithotypes for testing of stone consolidants. Paper presented at the Science and Art: A Future for Stone: Proceedings of the 13th International Congress on the Deterioration and Conservation of Stone, Volume 1. Paisley: University of the West of Scotland; Hughes, J., & Howind, T. (Eds. 2016.

- CEN (2010) Standard EN 15886, Conservation of cultural property. Colour measurement of surfaces.

- Degen T, Sadki M, Bron E, König U, Nénert G. The HighScore suite. Powder Diffraction 2014, 29, S13–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber J, Fawcett T. The powder diffraction file: present and future. Acta Crystallographica Section B: Structural Science 2002, 58, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabekkodu SN, Faber J, Fawcett T. New Powder Diffraction File (PDF-4) in relational database format: advantages and data-mining capabilities. Acta Crystallographica Section B: Structural Science 2002, 58, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kock T, Turmel A, Fronteau G, Cnudde V. Rock fabric heterogeneity and its influence on the petrophysical properties of a building limestone: Lede stone (Belgium) as an example. Eng Geol 2017, 216, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graue BJ (2013) Stone deterioration and replacement of natural building stones at the Cologne cathedral-A contribution to the preservation of cultural heritage. Doctoral Degree.

- Rohatsch A (2005) Neogene Bau-und Dekorgesteine Niederösterreichs und des Burgenlandes. In: Schwaighofer, B. Rohatsch A (2005) Neogene Bau-und Dekorgesteine Niederösterreichs und des Burgenlandes. In: Schwaighofer, B., Eppensteiner,W. (Eds.), “Junge” Kalke, Sandsteine und Konglomerate — Neogen. Mitteilungen IAG BOKU, pp. 27–31.

- De Kock T, Boone M, Dewanckele J, De Ceukelaire M, Cnudde V. Lede Stone: A Potential" global Heritage Stone Resource" from Belgium. Episodes 2015, 38, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graue B, Siegesmund S, Middendorf B. Quality assessment of replacement stones for the Cologne Cathedral: mineralogical and petrophysical requirements. Environ Earth Sci 2011, 63, 1799–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendlandt WW (1974) Thermal methods of analysis.

- Haines PJ (2012) Thermal methods of analysis: principles, applications and problems.

- Haaland MM, Friesem DE, Miller CE, Henshilwood CS. Heat-induced alteration of glauconitic minerals in the Middle Stone Age levels of Blombos Cave, South Africa: Implications for evaluating site structure and burning events. Journal of Archaeological Science 2017, 86, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashlan M, Martinec P, Kašlík J, Kovářová E, Scucka J Mössbauer study of transformation of Fe cations during thermal treatment of glauconite in air. In: AIP Conference Proceedings, 2012. vol 1.

- Fanning DS, Keramidas VZ, El-Desoky MA (1989) Micas. In: Minerals in soil environments, vol 1.

- Stoch, L. Significance of structural factors in dehydroxylation of kaolinite polytypes. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 1984, 29, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heide K, Földvari M. High temperature mass spectrometric gas-release studies of kaolinite Al2[Si2O5(OH)4] decomposition. Thermochimica Acta 2006, 446, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungár T (2000) Industrial Applications of X-ray Diffraction, edited by FH Chung & DK Smith. M: New York.

- Rietveld, HM. A profile refinement method for nuclear and magnetic structures. Journal of applied Crystallography 1969, 2, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sippel J, Siegesmund S, Weiss T, Nitsch KH, Korzen M. Decay of natural stones caused by fire damage. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 2007, 271, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, M. , Luxbacher T., Lützenkirchen J., Viani A., Bianchi S., Hradil K., Rohatsch A. & Castelvetro V. Evolution of calcite surfaces upon thermal decomposition, characterized by electrokinetics, in-situ XRD, and SEM. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2021, 624, 126761. [Google Scholar]

- Stanmore BR, Gilot P. Review—calcination and carbonation of limestone during thermal cycling for CO2 sequestration. Fuel Processing Technology 2005, 86, 1707–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, M. , Mascha E., Weber J., Rohatsch A., & Delgado Rodrigues J. Efficiency and compatibility of selected alkoxysilanes on porous carbonate and silicate stones. Materials 2019, 12, 156. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, M. (2021). Chemo-mineralogical and petrophysical alterations on lithotypes due to thermal treatment before stone consolidation [Dissertation, Technische Universität Wien]. reposiTUm. [CrossRef]

| Stone | Cal | Dol | Qtz | Kao | Phy | Goeth | KFSP | Pl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apuan Marble (AM) | *** | tr | tr | tr | ||||

| St. Margarethen (SM) | *** | tr | ||||||

| Ajarte Dolostone (AD) | *** | tr | ||||||

| Ajarte Calcite (AC) | *** | tr | tr | |||||

| Balegem (BL) | *** | *** | * | * | ||||

| Schlaitdorf (SQ) | * | *** | ** | tr | tr | tr | ||

| Obernkirchen (OQ) | *** | * | tr | tr | * |

| Stone | 600°C isothermal (TGA) |

600°C non-isothermal (STA) | Residual Mass (STA) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 °C min-1 3 cycles at 60 min |

40 °C min-1 1 cycle at 180 min |

10 °C min-1 22 to 600 °C |

10 °C min-1 at 1000 °C |

|

| Apuan Marble | 0.705 | N/A | 0.13 | 55.92 |

| St. Margarethen | 0.627 | N/A | 0.40 | 55.93 |

| Ajarte Dolostone | 7.891 | 7.301 | 1.38 | 53.51 |

| Ajarte Calcite | 3.033 | 2.840 | 0.84 | 58.19 |

| Balegem | 1.971 | 1.815 | 0.65 | 79.76 |

| Schlaitdorf | 4.013 | 3.845 | 2.16 | 94.09 |

| Obernkirchen | 1.122 | 1.117 | 0.96 | 98.81 |

| Stone | ΔL* | Δa* | Δb* | ΔE* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM | 9.17 ± 0.02 | 0.91 ± 0.01 | 2.31 ± 0.02 | 9.50 |

| SM | -15.62 ± 0.16 | -2.60 ± 0.1 | -14.38 ± 0.23 | 21.38 |

| AD | -12.13 ± 0.03 | 1.91 ± 0.16 | -3.02 ± 0.15 | 12.65 |

| AC | -11.4 ± 0.04 | 0.58 ± 0.01 | -2.53 ± 0.03 | 11.69 |

| BL | -6.85 ± 0.08 | 3.90 ± 0.08 | 3.10 ± 0.11 | 8.47 |

| SQ | -3.35 ± 0.76 | 5.92 ± 0.65 | 3.68 ± 0.08 | 7.73 |

| OQ | -3.24 ± 0.93 | 5.68 ± 0.16 | 5.60 ± 0.01 | 8.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).