1. Introduction

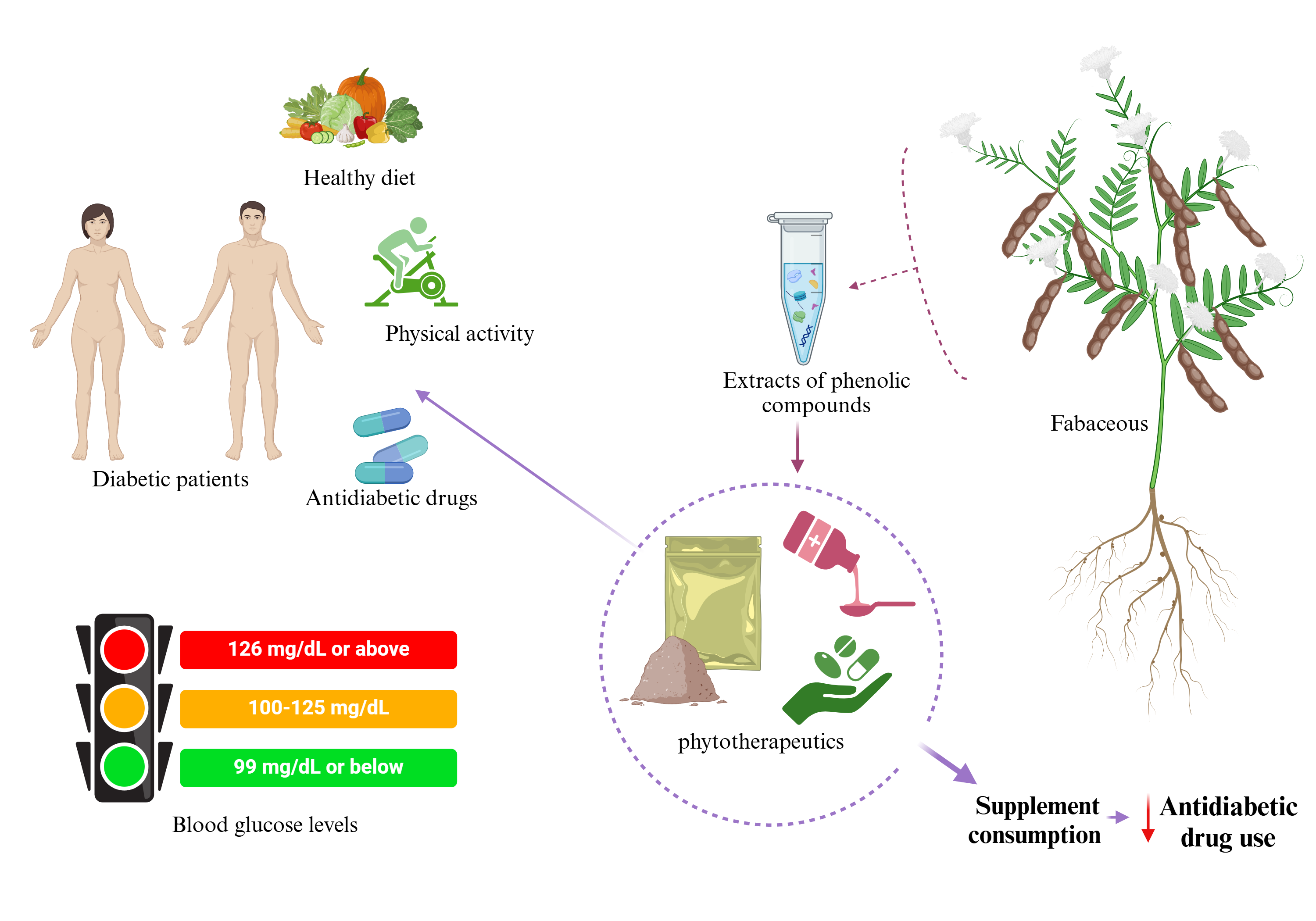

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a non-communicable disease characterized by high blood glucose levels (hyperglycemia), with disturbances in carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism. These metabolic disorders are caused by defects in insulin secretion and/or a lack of response to the action of this hormone in target organs. When DM is not controlled correctly, it can result in severe complications, including cardiovascular disease, renal failure, nerve damage, and blindness, even early death [

1,

2,

3]. In treating DM, several therapeutic measures are fundamental for adequate metabolic control. These include some non-pharmacological measures, such as regular physical activity and a healthy diet, and other pharmacological measures, including oral antidiabetic drugs [

4]. Besides, therapeutic alternatives of natural origin have been sought, such as plants, due to containing bioactive compounds with pharmacological properties, which intervene in the antioxidant action, or those that have as mechanisms of action the regulation of glucose, among others [

5,

6]. Plants are considered important in traditional medicine and human nutrition, among which edible fabaceous (legumes) stand out, such as soybeans, beans, peas, broad beans, lentils, peanuts, and chickpeas. It has been suggested that these fabaceous can help prevent or reduce complications of diabetes treatment and may even have a similar effect the insulin [

7]. Compounds such as alkaloids, phenolics, carotenoids, flavonoids, lectins, tannins, trypsin, glycosides, coumarins, and saponins have been identified in the fabaceous as those responsible for some biological activities [

8,

9].

Phenolic compounds are secondary metabolites that give plants essential functions such as color, flavor, and resistance to stress. Beyond their organoleptic properties, these compounds are engaging in the human diet because they contain flavonoids that are highlighted for their antioxidant properties to attack cell damage [

10,

11], meaning they can help confront damage caused by free radicals in the body [

12]. The comprehensive view on the benefit of polyphenols with antidiabetic effects, present in commonly fabaceous, can motivate clinical trials, attracting multiple disciplines for their investigation. Given the growing concern among individuals with DM about the potential side effects of synthetic pharmaceutical agents, the research community is increasingly looking for natural products as a safer alternative. This review, therefore, holds significant importance as it aims to explore the antidiabetic proprieties of phenolic compounds extracted from the most well-known and commonly consumed fabaceous, offering potential solutions to these pressing health concerns.

2. Methodology

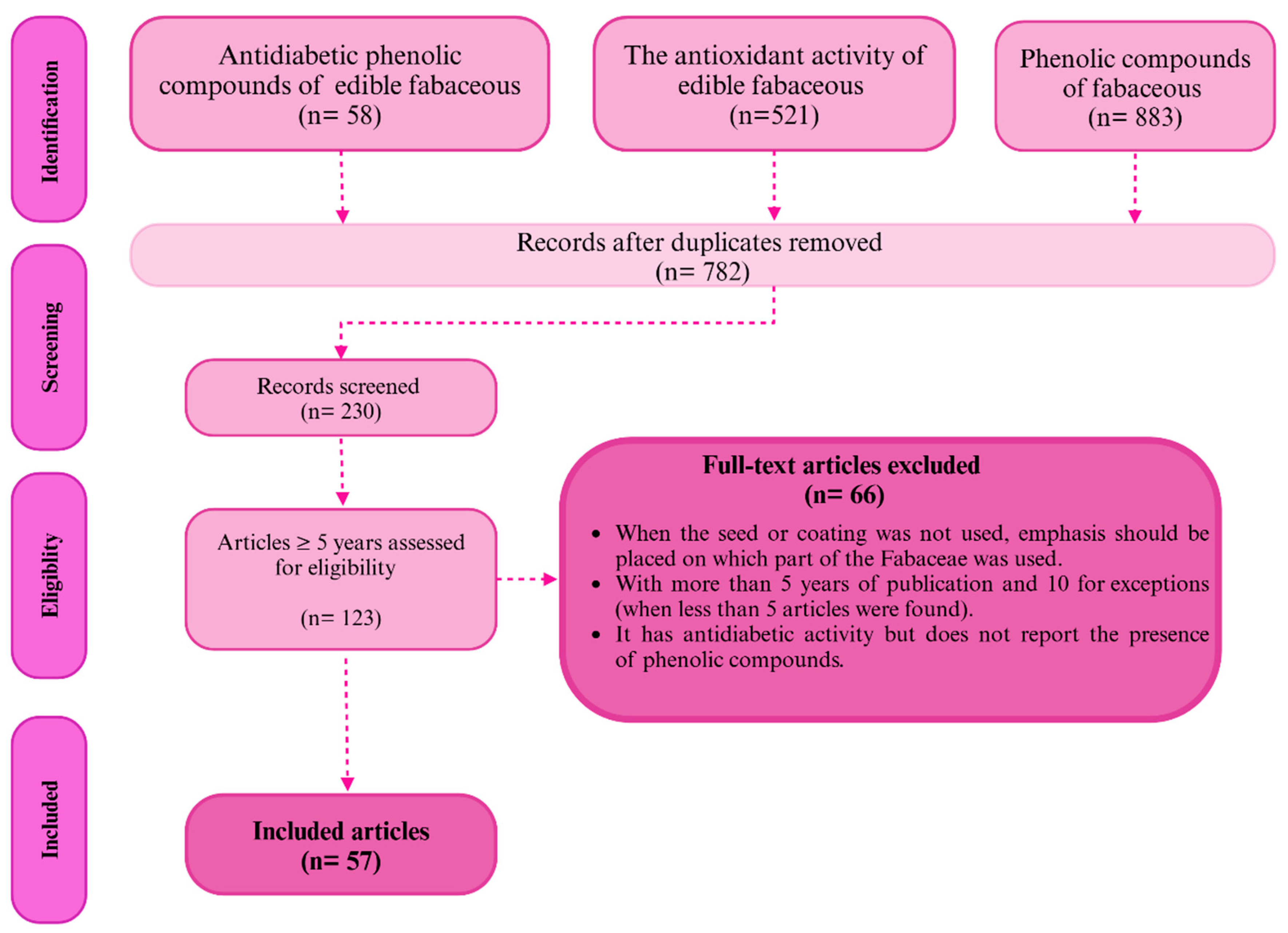

The search for information was done following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis) on Google Scholar, PubMed, Science Direct, and Scopus. Of all the articles found, those published within the previous 5 years were considered, with a maximum limit of 10 years for the plants with scarce information (less than five articles). The keywords used for the search of articles were fabaceous (in general and for each of the species presented, it was also sought as legumes), “phenolic compounds,” “antidiabetic phenolic compounds fabaceous,” “extracts antidiabetic fabaceous,” “antioxidant activity fabaceous,” and each of the species. From the selected articles, the general characteristics of fabaceous compounds, the phenolic compounds content, and the most outstanding ones were considered, in addition to the results showing the hypoglycemic effect.

Figure 1 shows the process of searching for information. First, we explored Google Scholar to determine whether the required information was available. Then, we used the most well-known databases and journals with a publication trend, precise information, and inclusion and exclusion criteria.

3. Diabetes Mellitus Generalities

According to the International Diabetes Federation, in 2021, the number of people living with diabetes worldwide was 537 million, of whom more than 95% had type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [

1,

13]. DM is diagnosed in patients who meet one of the following criteria: glycohemoglobin A1C (≥48 mmol/mol), fasting plasma glucose (FPG) value (≥126 mg/dL), 2-hour glucose value (≥200 mg/dL) during a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), or random glucose value (≥200 mg/dL) [

14].

Beta cells, one of the cells of the pancreatic islet, synthesize and secret insulin, regulating blood glucose levels [

15]. After meal, glucose is transported in the blood and enters the beta cell through the glucose transporter Glut2, glucose is metabolized through glycolysis, increasing the intracellular ATP/ADP ratio, which in turn leads to the closure of the ATP-dependent potassium (KATP) channels in the plasma membrane. This causes membrane depolarization and opening of voltage-gated calcium channels, allowing Ca2+ to enter the cell, triggering insulin exocytosis, leading to the release of insulin into the bloodstream [

16]. Impaired pancreatic beta cell function has been identified as a major factor contributing to the onset of T2DM. The possible mechanisms leading to beta cell failure can be classified into three categories: a) reduced beta-cell number, b) beta-cell exhaustion, and c) loss of beta cell identity [

17,

18]. The evidence indicates that hyperglycemia is the triggering factor regardless of the mechanism leading to impaired beta-cell function. Hyperglycemia elicits oxidative stress [

19], inflammation, cytokine secretion, beta cell exhaustion, and apoptosis, resulting in the complications of diabetes [

20].

Based on the above information, antidiabetic agents are targeted at different steps in the signaling and function of insulin such as activation of insulin receptors (insulin analogs) and downstream signaling in multiple sensitive tissues [

4], insulin sensitizer (sulfonylureas, biguadines) increasing glucose uptake in tissues of the whole body [

21,

22], opening voltage-dependent calcium channels (meglitinides) [

23], inhibitors of SGLT-2 [

24].

The treatment of diabetes mellitus is based on the diagnosis of the type of diabetes mellitus, the available treatment regimens, lifestyle changes (diet and exercise), oral hypoglycemic drugs, such as biguanides, sulfonylureas, meglitinides, thiazolidinediones, gliptins, α-glucosidase and sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors and finally insulin. An alternative antidiabetic medication should, as far as possible, be capable of preventing the onset and progression of T2DM and should stop the loss of beta cells and/or promote the restoration of beta cell mass independently of reducing hyperglycemia and ameliorating glucotoxicity and oxidative stress in pancreatic islets. Plants and their fruit could be a good alternative with few or no adverse effects in the treatment of diabetes [

25].

For centuries, plants have been used to treat diseases, being the precursors of modern medicine. The use of plants was intended to reduce the discomfort caused by diseases, ensuring that the plant worked through trial and error. Based on cultural beliefs and experiences transmitted from generation to generation, different parts of plants, such as seeds, flowers, leaves, roots, bark, fruits, and stems, were used without knowing the active ingredient or mechanism [

26,

27]. Plant extracts are used as supplements for treating diseases, becoming a natural therapeutic alternative with almost no side effects because they come from commonly consumed plants such as fabaceous [

28,

29].

4. Importance of Secondary Metabolites in Fabaceous

Fabaceae are part of a family of nitrogen-fixing plants comprising 770 genera and approximately 19,500 species, which helps to grow other plants in infertile or nutrient-poor soils. The plants of these species are climbers (annuals), herbs, aquatic plants, woody lianas, trees, shrubs, and subshrubs [

8]. This family includes the fabaceous, commonly known as legumes. They are characterized by producing pods containing seeds (one to twelve) that vary in color, size, and shape depending on the type of plant. Many of the fabaceous are used for human consumption and/or oil extraction, as well as for animal feed, being the most common soybeans, beans, peas, broad bean, lentils, peanuts, and chickpeas due to the quality of their nutrients (complex carbohydrates, unsaturated fats, proteins, amino acids, vitamins, and minerals) and to their low cost [

30,

31]. The fabaceous also contain secondary metabolites (SM) that act in the plants as a chemical defense against insects or predators and attract pollinators; on the other hand, when they are consumed, they present biological activities with benefits to the health [

27,

32,

33,

34]

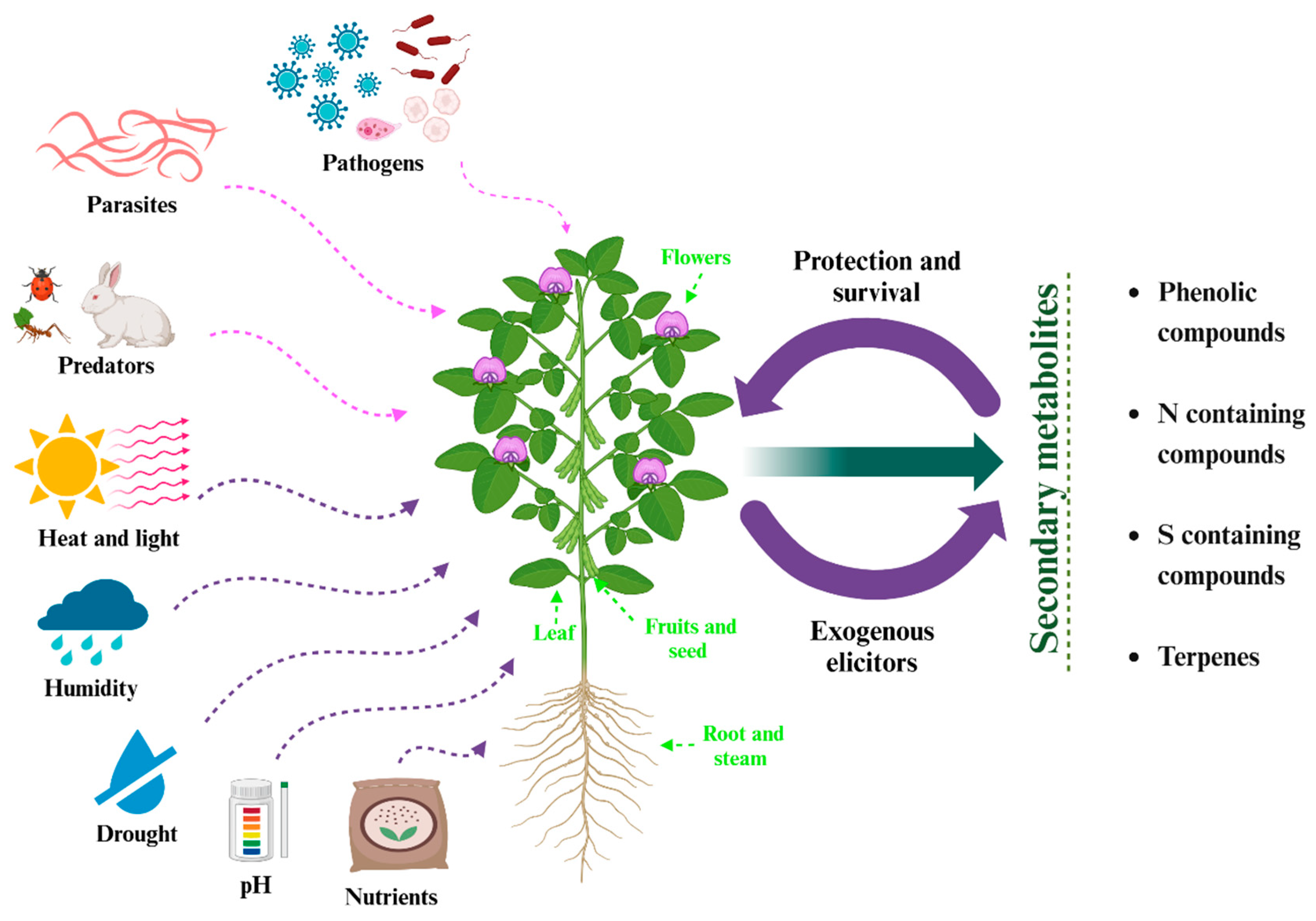

Secondary metabolites are chemical compounds produced by plants, fungi, and some microorganisms essential for interacting with the environment; the SM has a molecular mass of <3000 kDa, and they are distributed throughout the plant [

33,

35]. The stress (biotic or abiotic) to which a plant is subjected influences the production of SM; this can be caused by herbivores, pathogens, salinity, solar radiation, extreme temperatures, drought, and lack of nutrients (

Figure 2). The SM, being a response to stress, turns them into defenders of the plant, thus achieving its adaptation to the environment and its survival [

33,

36]. Plants, through their SM, can attract pollinating insects, as well as nitrogen-fixing bacteria, forming nodules of different sizes and characteristics in their roots [

37]. SM can be classified into four main groups: phenolic compounds, nitrogen compounds, sulfur compounds, and terpenes. Phenolic compounds are distinguished for their defense of plants, functioning as antimicrobials and herbivore repellents. They also contribute to protection against oxidative damage [

35].

5. Antioxidant Activity of Total Phenolic Compounds from Fabaceous

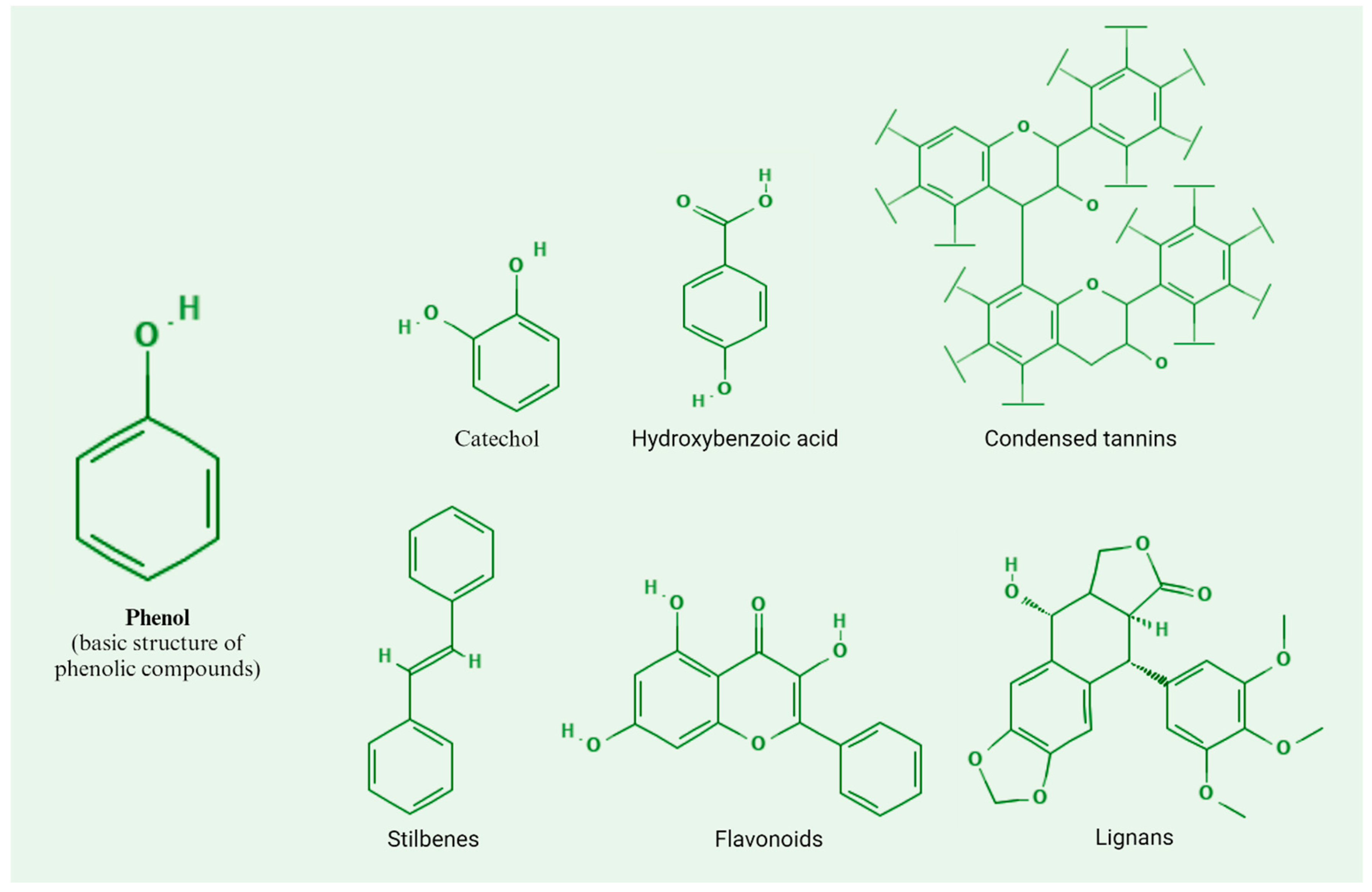

The main characteristic of phenolic compounds is an aromatic ring and a hydroxyl group; within these, we can find catechol, derivatives of hydroxybenzoic acid, condensed tannins, flavonoids, stilbenes, and lignans (

Figure 3). Phenolic compounds, being plant protectors, can function as toxins for herbivores or alter the growth or physiological processes of insects due to oxidation to toxic metabolites [

33].

On the other hand, phenolic compounds also give color to the products extracted from red fruits (i.e., juices and wines), contributing to the aroma and enzymatic browning of the fruits [

38]. Furthermore, phenolic compounds from vegetables and fruits, legumes, and grains included in the diet are associated with health benefits [

11,

38].

Table 1 shows the variability of phenolic compound concentration depending on cultivation, type, region, and conditions in which they are grown. For example, the highest concentration of these compounds in soybeans is reported in wild soybeans, 41.53 ± 1.25 mg GAE/g, compared to cultivated soybeans, whose concentration is lower (approximately 12.5 mg GAE/g). On the other hand, the color of the different varieties of bean seeds is also reflected in the values of phenolic compounds, such as in black, velvet, red, and white, where there is a range of 197-1328 mg GAE/g [44-46]. Something similar happens with pea varieties, although the concentration is lower than in beans, ranging from 0.12 to 2.66 mg GAE/g, which possess a considerably wide range. The phenolic compound profile in the fabaceous of

Table 1 is unique and presents an extensive range due to variety (genetic diversity), environment, stage of maturity, growing conditions, and cultivation methods [

33].

Moreover, the amount of phenolic compounds in fabaceous has been shown to correlate with antioxidant capacity and health benefits (

Table 2). For example, in the case of soybeans, the flavonoids predominate, which have an associated relationship with this biological activity, having a high antioxidant capacity around 80% of inhibition of free radicals through ABTS and DPPH reported [

40]. In the case of beans, the presence of anthocyanins, which are responsible for giving red, blue, and purple colors, also influences the inhibitory activity of free radicals [

46]. Although flavonoids are also reported in peas, they contain free phenolics that are more available to exert antioxidant activity. Fabaceous foods like beans and lentils have more phenolic compounds, influencing their antioxidant activity. However, this activity does not reflect as much variation depending on the color of the seed but rather on the profile of the compounds (

Table 2).

Phenolic compounds extraction and processing as phytotherapeutics have the potential to be effective therapeutic or preventative agents against different diseases [

11,

38], neutralizing free radicals and protecting cells from oxidative damage. This is known as antioxidant capacity, one of the most studied biological activities, due to its relationship with chronic diseases. For example, in DM, an increase in free radicals affects the mechanism of insulin action, causing damage to pancreatic beta cells.

Phenolic compounds, as part of bioactive compounds, have been shown to significantly inhibit enzymes such as lipases, α-amylase, α-glucosidase, and β-glucosidase

in vitro. By inhibiting α-glucosidase, these compounds reduce glucose digestion and absorption in the intestine, which is crucial for managing type 2 diabetes, as they help regulate blood sugar levels after meals. The activity of phenolic compounds underlines the importance of bioactive compounds in the diet, highlighting their potential to contribute to the prevention and control of metabolic diseases [

69,

70]. The bioactive compounds contained in fabaceous reduce the risk of suffering from T2DM [

32,

33].

In vitro antidiabetic studies of fabaceous have been evaluated through various methods, including glucose uptake assay and the inhibition of α-glucosidase, α-amylase, and DPP-IV (Dipeptidyl peptidase IV) [

31].

6. In vitro and in vivo Antidiabetic Studies of Edible Fabaceous

6.1. Soybean

Soybean (

Glycine max) is one of the most edible fabaceous with the highest protein (40%), besides the wild soybean tends to have 10% more protein and 10 % less oil than black soybean [

71]. In addition to its nutritional composition, carbohydrates (33%), unsaturated fatty acids (20%), fiber, vitamins, minerals, and other bioactive compounds as polyphenols, flavonoids, isoflavone, and glycosides [

42,

72,

73]. The combination of phenolic compounds such as anthocyanins, proanthocyanidins, chlorophyll, and other pigments defines the characteristic color of their seed coat [

39,

74].

Identifying and analyzing the α-glucosidase enzyme inhibitors derived from black soybeans results in the bioactive compounds present in this fabaceous achieving inhibition of the enzyme; this leads to the regulation of glucose levels because the digestion of carbohydrates is reduced, which suggests a potential use for the management of T2DM. Soy isoflavones (daidzin, glycitin, genistin, malonyldaidzin, malonylgenistin, genistein, and daidzein) inhibitors of α-glucosidase were identified, resulting in daidzein (IC

50 15.7 ± 0.3 μmol/L) and genistein (IC

50 3.2 ± 1.2 μmol/L) showing an inhibitory activity superior to that of acarbose (IC

50 632.5 ± 70.0 μmol/L). The structure-activity relationship indicated that isoflavone aglycones without glucosylation have higher inhibitory activity. Hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds were the main forces involved in the interaction between isoflavones and α-glucosidase, suggesting that black soybean, through its isoflavones, has significant antidiabetic potential [

72]. In another investigation conducted with the same animal model of T2DM,

Glycine max fermented flour was used in a dose of 18.050 mg/kgBW, reducing blood glucose as the positive control group (administration of treatment). One of the hypoglycemic mechanisms is that isoflavone compounds can be transformed into aglycones (genistein, glycitein, and daidzein), which help reduce blood glucose. In addition, the fermentation process can transform the aglycone to produce compounds with greater biological activity, such as 6,7,4' trihydroxy isoflavone, which has better antioxidant activity than daidzein and genistein. It also acts on free radicals caused by hyperglycemia. Isoflavones lower blood glucose by activating the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor and protecting cells from cytokine pre-inflammation, fat-induced damage, and apoptosis [

75].

Son

et al. investigated the antidiabetic effects of

Glycine soja extract in type 2 diabetic mice and insulin-resistant human hepatocytes for 6 weeks. Different concentrations were evaluated, with the group receiving the highest dose (300 mg/kg/day) achieving the lowest blood glucose levels (331.3 ± 78.6 mg/dL). Significant effects showed properties that improve insulin sensitivity by increasing adiponectin, and blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin levels were reduced, especially at doses higher than 150 mg/kg/day [

71]. The hypoglycemic effect of fermented mulberry with soy has also been evaluated. This mixture for diabetic mice (type 2) reduced blood glucose levels, and improvements were observed in pancreatic function and insulin sensitivity. This indicates that the combination of mulberry and soy (1:5) enhances the beneficial effects at a concentration of 2.26 g/kg/day since the diabetic group reduced food consumption, improved glucose tolerance, and optimized the blood lipid profile, thanks to its antioxidant capacity [

76].

6.2. Beans

Beans are oneBeans (

Phaseolus vulgaris) are one of the most widely consumed fabaceous, with black beans being one of the main ones included in the diets of Latin America and Africa. This fabaceous stands out due to its rich nutritional composition of protein (17.9–31.1%), carbohydrates (25–60%), lipids (0.55–2.1%), fiber (4–20%), vitamins, and minerals. Despite being rich in carbohydrates, they have a low glycemic index, so they release their energy slowly, helping to keep blood sugar levels stable [

77]. This fabaceous is rich in nutrients such as carbohydrates, proteins, fiber, and bioactive compounds (phenols, alkaloids, phytosterols, coumarins, and saponins). It has been reported that polysaccharides, peptides, and polyphenols. Bean seeds (

Phaseolus vulgaris) are used as traditional medicine in some parts of China [

78]. Polyphenol extracts in mung beans (common compounds in plants) have a hypoglycemic effect. By consuming foods with a low glycemic index and high dietary fiber content, the blood glucose is reduced, facilitating the elimination of glucose through the glucose transporter (GLUT4) [

79,

80].

A study evaluating the inhibitory effects of polyphenol-rich extracts (from 6 bean varieties) on α-amylase and α-glucosidase enzymes found that the Sanghellato variety had the highest amount of phenolic compounds. In carbohydrate digestion, polyphenolic extracts showed an inhibition of the α-amylase enzyme as well as inhibiting the α-glucosidase enzyme. The Screziato Impalato variety presented the best inhibition of α-amylase with an IC

50 value of 69.02 µg/mL. For α-glucosidase, there was a more significant inhibition presenting an IC

50 of 90.40 µg/mL for variety Cannellino Rosso. It is reported that tannins and proanthocyanidins (phenolic compounds) are related to the inhibition of both enzymes, suggesting a synergistic interaction between phenolic compounds and the inhibitory effect. [

81].

In a mouse model with T2DM, the hypoglycemic effect of beans was evaluated, where a significant reduction in blood glucose, cholesterol, and lipid levels was observed due to the influence on metabolic pathways related to insulin sensitivity and the regulation of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism. The identified metabolites have significant potential for managing T2DM; this is also associated with the enrichment of bean sprouts with γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). A decrease in urea and creatine was also recorded, indicating that various metabolic parameters are improved in diabetic mice [

82]. On the other hand, the effect of polyphenol extracts from germinated mung beans was evaluated in T2DM mice, obtaining significant improvements in blood glucose levels and the reduction of systemic inflammation associated with T2DM. Polyphenolic extracts reduce fasting glucose levels, improve glucose tolerance, and decrease insulin resistance, giving a better effect with the high concentration group (150 mg/kg) of the extract and improving lipid levels and liver enzymes. Along with these results, a balance was observed in the mice's intestinal microflora related to insulin sensitivity [

83]. In another study, they evaluated the effect of bean-rice and rice-without-bean intake in adults with T2DM, with consumption at different times; a significant difference was obtained in the groups that consumed bean-rice compared to those that did not. Three varieties of beans were evaluated; the groups that ingested pinto and black beans showed lower glycemic values than the red beans and the control (rice only). This study suggests that including beans in meals can reduce the glycemic response in patients with T2DM, offering a non-pharmacological dietary management alternative. In addition, promoting these traditional foods can improve dietary adherence and quality of life in minority and immigrant populations with diabetes [

84]. Knowing the effect of the compounds present in beans is important, as few studies focus on the substances. Although the main phytonutrients studied as phytotherapeutics are secondary metabolites, the study of the various components of foods should be expanded.

6.3. Pea

The pea (

Pisum sativum) is a bean of European origin [

65], which is very adaptable to cultivation. Peas have a high nutritional value due to their composition of dietary fiber (11.34 – 16.13%), lipids (0.57 – 3.52%), and protein (19.75 – 26.48%), in addition to trace elements, phenolic compounds, and their glycemic index is less than 60 (considered medium or low). Flavonoids are the main polyphenols in peas, so their content of bioactive compounds can be used for functional foods or some other products [

49,

85].

Di Stefano et al. investigated how bioprocessing (germination and fermentation) of fabaceous influences the inhibitory activities of DPP-IV and α-glucosidase. The findings indicated that bioprocessing facilitates the digestion and absorption of bioactive compounds, and that yellow pea extract can inhibit two critical enzymes in blood glucose regulation: DPP-IV and α-glucosidase. The inhibition of DPP-IV was approximately 55.1 ± 1.5 milliequivalents of Diprotin A, while the inhibition of α-glucosidase was 56.5 ± 5.2 milliequivalents of acarbose, suggesting that processed fabaceous could function as health supplements [

85]. In another research, the inhibitory activity of the enzyme α-glucosidase from pea (

Cajanus cajan) extract was tested. This extract containing saponins, flavonoids, phenolics, and tannins, among other compounds, caused a delay in the breakdown of carbohydrates, leading to a decrease in glucose absorption into the bloodstream and thus lowering postprandial hyperglycemia. The enzyme α-glucosidase results in an IC

50 value of 69.67 ppm, which indicates a high level with potential for antidiabetic drug [

86]. The consumption of peas has presented advantages for potentially improving diseases associated with insulin resistance. Peas with a low glycemic index (22) can help maintain blood sugar levels, which can trigger an improvement in insulin sensitivity [

50].

6.4. Broad Beans

Vicia faba, known as the broad beans, is a fabaceous rich in nutrients such as protein (present in high amounts; 29%), carbohydrates (56 – 68%), lipids (2.30 – 3.91%), fiber, vitamins, and phenolic compounds in the seed. Due to the root nodules, the bean plant has a greater capacity to fix nitrogen than other bean plants. The consumption of broad bean flowers benefits health due to their polyphenol content, which reduces the risk of cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes due to their ability to counteract free radicals [

87,

88]. The broad bean has a low glycemic index and little fat; this seed is a health promoter because it has anti-cancer, anti-diabetic, anti-obesity, and cardioprotective effects. The primary polyphenols in broad beans are tannins; broad bean seeds usually have many phenolic compounds, almost twice as many as other fabaceous [

89]. Mejri

et al. report different percentages in extracting broad bean yield of phenolic compounds because different solvents were used to obtain them. Methanol presented the highest extraction with 25.8%, ethanol with 17.5%, butanol and ethyl acetate presented the lowest extraction percentage, 11.3% and 0.81%, respectively. The methanolic extract also exhibited the highest total phenolic, flavonoid, and tannin content and showed antidiabetic effects in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. It was found that blood glucose concentration and deterioration of pancreatic β-cells produced by alloxan were reverted after the administration of BBP extract, apparently through its antioxidant properties [

52]. Sharma and Giri reported an α-amylase inhibitory concentration IC

50 of 264.69 μg/mL, thus providing data on the properties of natural antidiabetic agents of the broad; this result was better than the standard (acarbose IC

50 of 52.76 μg/mL) [

52]. When extracts are obtained with different solvents, there may be differences in the potential for inhibition of α-amylase, as shown in the study of broad bean where the best concentration was 3-5 mg/mL with the acetone and methanol extracts having an IC

50 value of 2.94 mg/mL, which could lead to a lower postprandial glucose level [

90]. Broad beans are a rich source of polyphenolic compounds acting as antioxidants scavenging free radicals helping in treating diabetes and with the rejuvenation of β cells of the pancreas; broad beans would be ideal for consumption by diabetics by inhibiting α-glucosidase, thus delaying the absorption of carbohydrates [

88].

6.5. Lentils

The lentil (

Lens culinaris) contains many macro and micronutrients: carbohydrates (40 – 50%), protein (20 – 30%), fiber, vitamins, and minerals, highlighting that the green and gray seeds are preventative and, in many cases, have a health benefit [

56,

57,

66]. Among the benefits of consuming lentils is their insoluble fiber content, as a source of prebiotics and prebiotic carbohydrates, stimulating the microbial flora, benefiting health, and preventing intestinal diseases. Lentils (sprouted) have been reported to improve blood glucose metabolism as well as decrease in lipoproteins and lipids in diabetic patients. Compared to other fabaceous, lentils contain a high content of phenolic compounds, with a high concentration of phenolic acids, flavonoids, and condensed tannins. The polyphenols in lentils reduce the glycemic index, making them suitable for a healthy diet [

56]. The consumption of lentils is recommended to prevent or control diabetes since it has been shown to improve the metabolism of lipids and lipoproteins, as well as help with blood glucose; the above is possible due to the fiber content, in addition to the flavonoids contained in them [

57].

Magro

et al. found phenolic compounds such as ferulic acid and quercetin in fermented lentils; vanillic acid and 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid were also detected (in fermented and non-fermented lentils). Lentils fermented with

Aspergillus niger showed greater inhibition (91%; 48 h of fermentation) of α-glucosidase than those fermented with

Aspergillus oryzae and non-fermented ones. For the inhibition of α-amylase, lentils fermented with

A. oryzae at different fermentation times (75%; 24h, 73%; 48h and 71%; 0h), α-Amylase is an enzyme that breaks down starches into simple sugars, and its activity may influence blood glucose control [

66].

In an experimental study with diabetic mice male and female, methanolic extracts of fermented lentil seeds were administered for 6–8 weeks. Aqueous methanolic extracts of fermented lentils reduced blood glucose in diabetic mice; the reduction was significantly greater with the 400 mg/kg extract (169.92 ± 1.62 mg/dL) than with the 200 mg/kg extract (180.83 ± 2.858 mg/dL) and 100 mg/kg (190.83 ± 1.80 mg/dL). All three doses showed a statistically significant difference from the diabetic control group with blood glucose concentration (252.17 ± 3.84 mg/dL). The group treated with glibenclamide showed a hypoglycemic effect due to its direct impact on the mechanics of insulin release from β cells and increasing glucose tolerance [

91].

6.6. Chickpea

The chickpea is fabaceous with a rich nutritional composition containing 17 to 22% of proteins, 18 to 22% of dietary fiber, and a higher lipid content of up to 7% [

60]. Chickpea bioactive compounds, such as phenolics, help inhibit the hydrolysis of carbohydrates and some lipids, decreasing the risk of developing T2DM. Polyphenols also have a mechanism of action to inactivate the DPP-IV enzyme by 70-90% [

92]. Seed chickpeas are other well-known and consumed fabaceous, but little research has been done on their phenolic compounds with antidiabetic potential. Chickpea (

Cicer arietinum) is characterized by its high protein content but also by the phenolic compounds it has, highlighting isoflavones (153 to 340 mg/100 g) [

41].

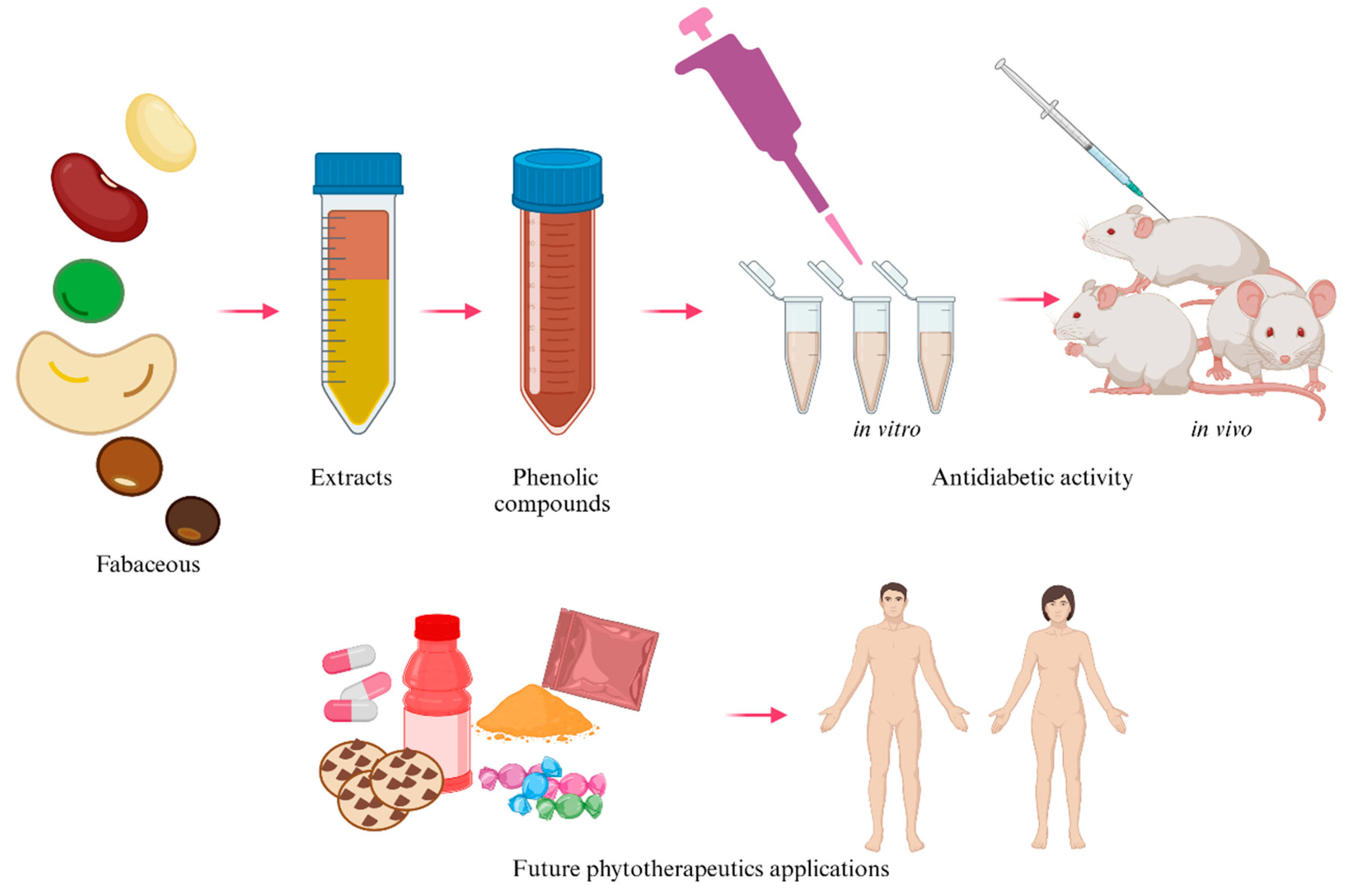

7. Perspectives

Natural products have been used as medicine throughout history and are still the basis for the development of drugs. Research not only seeks new molecules but also focuses on the development of phytotherapeutics to prevent or treat diseases or find evidence to support the biological activity of plants. The design and development of phytotherapeutics must be standardized, and the chemical compounds associated with the medicinal properties present in plants must be identified. Phytotherapeutics or nutraceuticals can be formulated from bioactive compounds such as phenolics (

Figure 4). Identifying phenolic compounds with antidiabetic potential can produce natural products in combination with pharmacological products that help prevent and/or treat diabetes mellitus, assisting patients with diabetes in the future. The analysis of bioactive molecules in plants drives the development of natural products, providing a new option for treating different diseases.

8. Conclusions

Fabaceous are accessible to virtually everyone and are essential for a healthy diet due to their nutritional profile. For some people, fabaceous are their primary source of protein as they avoid animal protein. The importance of fabaceous is highlighted by their bioactive compounds, such as phenols, which function as antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents and play an essential role in health, stabilizing free radicals and preventing cell damage. Oxidative stress caused by free radicals in cells is associated with Diabetes mellitus (DM), which contributes to complications in different organs. The action of phenolic compounds helps mitigate damage and reduce risks due to their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, benefiting patients with different pathologies.

Phenolic compounds have been evaluated in vitro and in vivo, where favorable results have been observed not only for their antioxidant capacity but also for their hypoglycemic effect, positively impacting the health of patients with diabetes mellitus; these characteristics make fabaceous of great interest with the potential to be used in future nutraceutical applications due to their efficacy.

The results of different studies summarized here support the role of fabaceous as adjuvants in the control of diabetes and show the importance of integrating the knowledge of traditional medicine with pharmacological medicine to improve the care of patients suffering from this condition. To integrate these herbal remedies into modern medicine, further research on phenolic compound type, doses, efficacy, and safety in humans.

Author Contributions

conceptualization L.G.-B.; Original draft preparation L.G.-B.; investigation L.G.-B., E.A.-O., S.M., and C.L.S.; writing L.G.-B., E.A.-O., S.M., A.M.-M., and C.S.-L.; supervision L.G.-B., S.M., A.M.-M. and C.L.S.; editor L.G.-B. S.M., C.L.S.; R.G.G.-G., and A.A.F.-P. all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by CONAHCyT grant G-1176.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing does not apply to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank CONAHCyT for the scholarship for PhD to the student L.G.-B.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- OMS. Diabetes. Available online: https://www.who.int/es (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Hu, K.; Huang, H.; Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Yao, C. Legume-Derived Bioactive Peptides in Type 2 Diabetes: Opportunities and Challenges. Nutr 2023, 15, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yedjou, C. G.; Grigsby, J.; Mbemi, A.; Nelson, D.; Mildort, B.; Latinwo, L.; Tchounwou, P. B. The Management of Diabetes Mellitus Using Medicinal Plants and Vitamins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M. S.; Hossain, K. S.; Das, S.; Kundu, S.; Adegoke, E. O.; Rahman, M. A.; Hannan, M. A.; Uddin, M. J.; Pang, M. G. Role of Insulin in Health and Disease: An Update. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Shahrajabian, M. H. Therapeutic Potential of Phenolic Compounds in Medicinal Plants—Natural Health Products for Human Health. Molecules 2023, 28, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B. B.; Chiang, B. H. A Novel Phenolic Formulation for Treating Hepatic and Peripheral Insulin Resistance by Regulating GLUT4-Mediated Glucose Uptake. J Tradit Complement Med 2022, 12, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przeor, M. Some Common Medicinal Plants with Antidiabetic Activity, Known and Available in Europe (A Mini-Review). Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroyi, A. Medicinal Uses of the Fabaceae Family in Zimbabwe: A Review. Plants 2023, 12, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K. R.; Giri, G. Quantification of Phenolic and Flavonoid Content, Antioxidant Activity, and Proximate Composition of Some Legume Seeds Grown in Nepal. Int J Food Sci 2022, 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alara, O. R.; Abdurahman, N. H.; Ukaegbu, C. I. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds: A Review. Curr Res Food Sci 2021, 4, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, P.; Cheng, G.; Zhang, Y. A Brief Review of Phenolic Compounds Identified from Plants: Their Extraction, Analysis, and Biological Activity. Nat Prod Commun 2022, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albergaria, E. T.; Oliveira, A. F. M.; Albuquerque, U. P. The Effect of Water Deficit Stress on the Composition of Phenolic Compounds in Medicinal Plants. S Afr J Bot 2020, 131, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Atlas. Available online: https://www.diabetesatlas.org (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepa-Maheshvare, M.; Raha, S.; König, M.; Pal, D. A Pathway Model of Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion in the Pancreatic β-Cell. Front Endocrinol 2023, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galicia-Garcia, U.; Benito-Vicente, A.; Jebari, S.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Siddiqi, H.; Uribe, K. B.; Ostolaza, H.; Martín, C. Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wysham, C.; Shubrook, J. Beta-Cell Failure in Type 2 Diabetes: Mechanisms, Markers, and Clinical Implications. Postgrad Med 2020, 132, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swisa, A.; Glaser, B.; Dor, Y. Metabolic Stress and Compromised Identity of Pancreatic Beta Cells. Front Genet 2017, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, P.; Lozano, P.; Ros, G.; Solano, F. Hyperglycemia and Oxidative Stress: An Integral, Updated and Critical Overview of Their Metabolic Interconnections. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 9352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, C. M. O.; Villar-Delfino, P. H.; dos Anjos, P. M. F.; Nogueira-Machado, J. A. Cellular Death, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Diabetic Complications. Cell Death Dis 2018, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Nayak, P.; Sharma, M.; Albutti, A.; Alwashmi, A. S. S.; Aljasir, M. A.; Alsowayeh, N.; Tambuwala, M. M. Emerging Treatment Strategies for Diabetes Mellitus and Associated Complications: An Update. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoia, T. E.; Shulman, G. I. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Metformin Action. Endocr Rev 2021, 42, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakkir Maideen, N. M.; Manavalan, G.; Balasubramanian, K. Drug Interactions of Meglitinide Antidiabetics Involving CYP Enzymes and OATP1B1 Transporter. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 2018, 9, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, C. K.; Zinman, B. Sodium–Glucose Cotransporter–2 (SGLT-2) Inhibitors and the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. Annu Rev Med 2019, 70, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhury, A.; Duvoor, C.; Reddy Dendi, V. S.; Kraleti, S.; Chada, A.; Ravilla, R.; Marco, A.; Shekhawat, N. S.; Montales, M. T.; Kuriakose, K.; et al. Clinical Review of Antidiabetic Drugs: Implications for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Management. Front Endocrinol 2017, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmerón-Manzano, E.; Garrido-Cardenas, J. A.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Worldwide Research Trends on Medicinal Plants. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqethami, A.; Aldhebiani, A. Y. Medicinal Plants Used in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: Phytochemical Screening. Saudi J Biol Sci 2021, 28, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Yan, H. L.; Wang, L. X.; Xu, J. F.; Peng, C.; Ao, H.; Tan, Y. Z. Review of Natural Resources With Vasodilation: Traditional Medicinal Plants, Natural Products, and Their Mechanism and Clinical Efficacy. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Alqahtani, A. S.; Noman, O. M. A.; Alqahtani, A. M.; Ibenmoussa, S.; Bourhia, M. A Review on Ethno-Medicinal Plants Used in Traditional Medicine in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. S J Biol Sci 2020, 2706–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Valdespino, C. A.; Luna-Vital, D.; Camacho-Ruiz, R. M.; Mojica, L. Bioactive Proteins and Phytochemicals from Legumes: Mechanisms of Action Preventing Obesity and Type-2 Diabetes. Food Research International 2020, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looi, E. P.; Mohd, M. N. The Bioactivities of Legumes: A Review. Food Res 2023, 7, 339–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, A. R.; El-Nashar, H. A. S.; Younis, T.; Mangat, M. A.; Shahzadi, M.; Ul Haq, A. S.; El-Shazly, M. Genus Lupinus (Fabaceae): A Review of Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical and Biological Studies. J Pharm Pharmacol 2022, 1700–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divekar, P. A.; Narayana, S.; Divekar, B. A.; Kumar, R.; Gadratagi, B. G.; Ray, A.; Singh, A. K.; Rani, V.; Singh, V.; Singh, A. K.; Kumar, A.; Singh, R. P.; Meena, R. S.; Behera, T. K. Plant Secondary Metabolites as Defense Tools against Herbivores for Sustainable Crop Protection. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, J.; Pearson, E.; Grafenauer, S. Legumes—A Comprehensive Exploration of Global Food-Based Dietary Guidelines and Consumption. Nutr 2022, 14, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twaij, B. M.; Hasan, M. N. Bioactive Secondary Metabolites from Plant Sources: Types, Synthesis, and Their Therapeutic Uses. Int J Plant Biol 2022, 13, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kong, D.; Fu, Y.; Sussman, M. R.; Wu, H. The Effect of Developmental and Environmental Factors on Secondary Metabolites in Medicinal Plants. Plant Physiol Biochem 2020, 148, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, Y. S.; Contador, C. A.; Ng, M. S.; Yu, J.; Chung, G.; Lam, H. M. The Effects of Domestication on Secondary Metabolite Composition in Legumes. Front Genet 2020, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheynier, V. Phenolic Compounds: From Plants to Foods. Phytochem Rev 2012, 11, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, V.; Žilić, S.; Simić, M.; Perić, V. Black Soya Bean and Black Chia Seeds as a Source of Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds with Health Benefits. Food Feed Res 2020, 47, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, X.; Yuan, X.; Shi, J.; Zhang, C.; Yan, N.; Jing, C. Comparison of Phenolic and Flavonoid Compound Profiles and Antioxidant and α-Glucosidase Inhibition Properties of Cultivated Soybean (Glycine Max) and Wild Soybean (Glycine Soja). Plants 2021, 10, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Camargo, A. C.; Favero, B. T.; Morzelle, M. C.; Franchin, M.; Alvarez-Parrilla, E.; De La Rosa, L. A.; Geraldi, M. V.; Maróstica, M. R.; Shahidi, F.; Schwember, A. R. Is Chickpea a Potential Substitute for Soybean? Phenolic Bioactives and Potential Health Benefits. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xia, N.; Teng, J.; Wei, B.; Huang, L. Effect of Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentation on Extractable and Non-Extractable Polyphenols of Soybean Milk: Influence of β-Glucosidase and Okara. Food Biosci 2023, 56, 2212–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadkaria, A.; Srivastava, N.; Bhagyawant, S. S. A Prospective of Underutilized Legume Moth Bean (Vigna Aconitifolia (Jacq.) Marechàl): Phytochemical Profiling, Bioactive Compounds and in Vitro Pharmacological Studies. Food Biosci 2021, 42, 2212–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, P. S.; Kumar, P. Optimization of Microwave Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Black Bean Waste and Evaluation of Its Antioxidant and Antidiabetic Potential in Vitro. Food Chem Adv 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowdhanya, D.; Singh, J.; Rasane, P.; Kaur, S.; Kaur, J.; Ercisli, S.; Verma, H. Nutritional Significance of Velvet Bean (Mucuna Pruriens) and Opportunities for Its Processing into Value-Added Products. J Agric Food Res 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thummajitsakul, S.; Piyaphan, P.; Khamthong, S.; Unkam, M.; Silprasit, K. Comparison of FTIR Fingerprint, Phenolic Content, Antioxidant and Anti-Glucosidase Activities among Phaseolus Vulgaris L., Arachis Hypogaea L. and Plukenetia Volubilis L. Electron J Biotechnol 2023, 61, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungmunnithum, D.; Drouet, S.; Lorenzo, J. M.; Hano, C. Effect of Traditional Cooking and in Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion of the Ten Most Consumed Beans from the Fabaceae Family in Thailand on Their Phytochemicals, Antioxidant and Anti-Diabetic Potentials. Plants 2022, 11, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding Tao, W.; Wen Xing, L.; Jia Jia, W.; Yi Chen, H.; Ren You, G.; Liang, Z. A Comprehensive Review of Pea (Pisum Sativum L.): Chemical Composition, Processing, Health Benefits, and Food Applications. Foods 2023, 12, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi Kang, C.; Hai Feng, L.; Xin, W.; Yi, Y.; Jun Yi, Y.; Xiao Xiao, S. Comprehensive Analysis in the Nutritional Composition, Phenolic Species and in Vitro Antioxidant Activities of Different Pea Cultivars. Food Chem X 2023, 17, 100599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, T.; Deka, S. C. Potential Health Benefits of Garden Pea Seeds and Pods: A Review. Legume Science 2021, 3, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejri, F.; Selmi, S.; Martins, A.; Benkhoud, H.; Baati, T.; Chaabane, H.; Njim, L.; Serralheiro, M. L. M.; Rauter, A. P.; Hosni, K. Broad Bean (Vicia Faba L.) Pods: A Rich Source of Bioactive Ingredients with Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, Enzyme Inhibitory, Anti-Diabetic and Health-Promoting Properties. Food Funct 2018, 9, 2051–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizzo, M. R.; Bonesi, M.; Leporini, M.; Falco, T.; Sicari, V.; Tundis, R. Chemical Profile and In Vitro Bioactivity of Vicia Faba Beans and Pods. Proc 2020, 70, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. B.; Skylas, D. J.; Mani, J. S.; Xiang, J.; Walsh, K. B.; Naiker, M. Phenolic Profiles of Ten Australian Faba Bean Varieties. Molecules 2021, 26, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, S. C.; Kwon, S. J.; Eom, S. H. Effect of Thermal Processing on Color, Phenolic Compounds, and Antioxidant Activity of Faba Bean (Vicia Faba l.) Leaves and Seeds. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajhi, I.; Boulaaba, M.; Baccouri, B.; Rajhi, F.; Hammami, J.; Barhoumi, F.; Flamini, G.; Mhadhbi, H. Assessment of Dehulling Effect on Volatiles, Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activities of Faba Bean Seeds and Flours. South African Journal of Botany 2022, 147, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Xu, B. Polyphenol-Rich Lentils and Their Health Promoting Effects. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18, 2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A. M.; Abouelenein, D.; Acquaticci, L.; Alessandroni, L.; Angeloni, S.; Borsetta, G.; Caprioli, G.; Nzekoue, F. K.; Sagratini, G.; Vittori, S. Polyphenols, Saponins and Phytosterols in Lentils and Their Health Benefits: An Overview. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attou, A.; Bouderoua, K.; Cheriguene, A. Effects of Roasting Process on Nutritional and Antinutritional Factors of Two Lentils Varieties (Lens Culinaris. Medik) Cultivated in Algeria. S A J E B 2020, 10, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Li, M.; de Souza, T. S. P.; Barrow, C.; Dunshea, F. R.; Suleria, H. A. R. LC-ESI-QTOF-MS2 Characterization of Phenolic Compounds in Different Lentil (Lens Culinaris M.) Samples and Their Antioxidant Capacity. Fron Biosci 2023, 28, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, N.; Khan, Q. U.; Liu, L. G.; Li, W.; Liu, D.; Haq, I. U. Nutritional Composition, Health Benefits and Bio-Active Compounds of Chickpea (Cicer Arietinum L.). Front Nutr 2023, 10, 1218468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K. R.; Giri, G. Quantification of Phenolic and Flavonoid Content, Antioxidant Activity, and Proximate Composition of Some Legume Seeds Grown in Nepal. Int J Food Sci 2022, 2022, 4629290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wu, S. Vegetable Soybean (Glycine Max (L.) Merr.) Leaf Extracts: Functional Components and Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. J Food Sci 2021, 86, 2468–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensiddhi, S.; Chanput, W. P.; Sae-Tan, S. Gut Microbiota Modulation, Anti-Diabetic and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Polyphenol Extract from Mung Bean Seed Coat (Vigna Radiata L.). Nutr 2022, 14, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ragaee, S.; Marcone, M. F.; Abdel-Aal, E. S. M. Composition of Phenolic Acids and Antioxidant Properties of Selected Pulses Cooked with Different Heating Conditions. Foods 2020, 9, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaldo, L.; Izzo, L.; Gaspari, A.; Lombardi, S.; Rodríguez-Carrasco, Y.; Narváez, A.; Grosso, M.; Ritieni, A. Chemical Composition of Green Pea (Pisum Sativum l.) Pods Extracts and Their Potential Exploitation as Ingredients in Nutraceutical Formulations. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magro, A. E. A.; Silva, L. C.; Rasera, G. B.; de Castro, R. J. S. Solid-State Fermentation as an Efficient Strategy for the Biotransformation of Lentils: Enhancing Their Antioxidant and Antidiabetic Potentials. Bioresour Bioprocess 2019, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochenek, H.; Francis, N.; Santhakumar, A.B.; Blanchard, C.L.; Chinkwo, K.A. The antioxidant and anticancer properties of chickpea water and chickpea polyphenol extracts in vitro. Cereal Chem 2023, 100, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekky, R.H.; Contreras, M.D.M.; El-Gindi, M.R.; Abdel-Monem, A.R.; Abdel-Sattar, E.; Segura-Carretero, A. Profiling of phenolic and other compounds from Egyptian cultivars of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) and antioxidant activity: A comparative study. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 17751–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Chang, S. K. C.; Zhang, Y. Comparison of α-Amylase, α-Glucosidase and Lipase Inhibitory Activity of the Phenolic Substances in Two Black Legumes of Different Genera. Food Chem 2017, 214, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A. Concept, Mechanism, and Applications of Phenolic Antioxidants in Foods. J Food Biochem 2020, 44, 13394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, E.; Jin Choi, H.; Kim, S.-H.; Jang, D.-G.; Cha, J.; June, J.; Ree Kim, M.; Kim, D.-S. Anti-Diabetic Effects of Wild Soybean Glycine Soja Seed 2 Extract on Type 2 Diabetic Mice and Human Hepatocytes Induced Insulin Resistance. Preprints 2020, 2020080572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Huang, F.; Cheng, L. H.; Xu, L.; Jia, X. α-Glucosidase Inhibitors Derived from Black Soybean and Their Inhibitory Mechanisms. LWT 2023, 189, 115502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król-Grzymała, A.; Amarowicz, R. Phenolic Compounds of Soybean Seeds from Two European Countries and Their Antioxidant Properties. Molecules 2020, 25, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosravi, A.; Razavi, S. H. Therapeutic Effects of Polyphenols in Fermented Soybean and Black Soybean Products. J Funct Foods 2021, 81, 104467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laenggeng, A. H.; Hasanuddin, A.; Nuryanti, S. The Effect of Fermented Soybean Flour towards Blood Glucose Level of Mice (Mus Musculus). World J Adv Res Rev 2024, 21, 2356–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X. S.; Liao, S. T.; Li, E. N.; Pang, D. R.; Li, Q.; Liu, S. C.; Hu, T. G.; Zou, Y. X. The Hypoglycemic Effect of Freeze-Dried Fermented Mulberry Mixed with Soybean on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Food Sci Nutr 2021, 9, 3641–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenu, M.; Chen, P.; Mradula, M.; Chang, S. K. C.; Xu, B. New Insights into Chemical Compositions and Health-Promoting Effects of Black Beans (Phaseolus Vulgaris L.). Food Front 2023, 4, 1019–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabré Wendmintiri Jeanne, d’Arc; Dah-Nouvlessounon, D.; Fatoumata, H. B.; Agonkoun, A.; Guinin, F.; Sina, H.; Kohonou N., A.; Tchogou, P.; Senou, M.; Savadogo, A.; Baba-Moussa, L. Mung Bean (Vigna Radiata (L.) R. Wilczek) from Burkina Faso Used as Antidiabetic, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Agent. Plants 2022, 11, 3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloto, M. R.; Phan, A. D. T.; Shai, J. L.; Sultanbawa, Y.; Sivakumar, D. Comparison of Phenolic Compounds, Carotenoids, Amino Acid Composition, in Vitro Antioxidant and Anti-Diabetic Activities in the Leaves of Seven Cowpea (Vigna Unguiculata) Cultivars. Foods 2020, 9, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Shen, X.; Shen, H.; Zhou, Y.; Yao, X. Effect of Optimized Germination Technology on Polyphenol Content and Hypoglycemic Activity of Mung Bean. Front Nutr 2023, 10, 1138739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ombra, M. N.; d’Acierno, A.; Nazzaro, F.; Spigno, P.; Riccardi, R.; Zaccardelli, M.; Pane, C.; Coppola, R.; Fratianni, F. Alpha-Amylase, α-Glucosidase and Lipase Inhibiting Activities of Polyphenol-Rich Extracts from Six Common Bean Cultivars of Southern Italy, before and after Cooking. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2018, 69, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, A.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Tang, H.; Cao, D.; Zhang, D. Revealing the Hypoglycemic Effects and Mechanism of GABA-Rich Germinated Adzuki Beans on T2DM Mice by Untargeted Serum Metabolomics. Front Nutr 2021, 8, 791191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Jiang, X.; Qian, L.; Zhang, A.; Zuo, F.; Zhang, D. Polyphenol Extracts From Germinated Mung Beans Can Improve Type 2 Diabetes in Mice by Regulating Intestinal Microflora and Inhibiting Inflammation. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 846409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, S. V.; Winham, D. M.; Hutchins, A. M. Bean and Rice Meals Reduce Postprandial Glycemic Response in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Cross-over Study. Nutr J 2012, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stefano, E.; Tsopmo, A.; Oliviero, T.; Fogliano, V.; Udenigwe, C. C. Bioprocessing of Common Pulses Changed Seed Microstructures, and Improved Dipeptidyl Peptidase-IV and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activities. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginaris, R. P.; Fauzah, N. R. The Effectiveness of Flavonoids in Pigeon Pea (Cajanus Cajan) as Inhibitors of α-Glucosidase Enzyme in Anti-Diabetes. J Ilmiah Farmasi 2023, 13, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elessawy, F. M.; Hughes, J.; Khazaei, H.; Vandenberg, A.; El-Aneed, A.; Purves, R. W. A Comparative Metabolomics Investigation of Flavonoid Variation in Faba Bean Flowers. Metabolomics 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Duhan, A.; Sangwan, S.; Yadav, N. A Brief Overview of the Biological Activities of Faba Bean (Vicia Faba). ResearchGate 2022, 48. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364814865.

- Rahate, K. A.; Madhumita, M.; Prabhakar, P. K. Nutritional Composition, Anti-Nutritional Factors, Pretreatments-Cum-Processing Impact and Food Formulation Potential of Faba Bean (Vicia Faba L.): A Comprehensive Review. LWT 2021, 138, 110796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, D. K.; Mishra, A. In Vitro and in Silico Interaction of Porcine α-Amylase with Vicia Faba Crude Seed Extract and Evaluation of Antidiabetic Activity. Bioengineered 2017, 8, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefera, M. M.; Masresha Altaye, B.; Yimer, E. M.; Berhe, D. F.; Bekele, S. T. Antidiabetic Effect of Germinated Lens Culinaris Medik Seed Extract in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Mice. J Exp Pharmacol 2020, 12, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo Martinez, K. A.; Yang, M. M.; Gonzalez de Mejia, E. Technological Properties of Chickpea (Cicer Arietinum): Production of Snacks and Health Benefits Related to Type-2 Diabetes. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2021, 20, 3762–3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Becerra, L. Figures created in BioRender. 2024. Available online: https://BioRender.com/o67k275.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).