Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

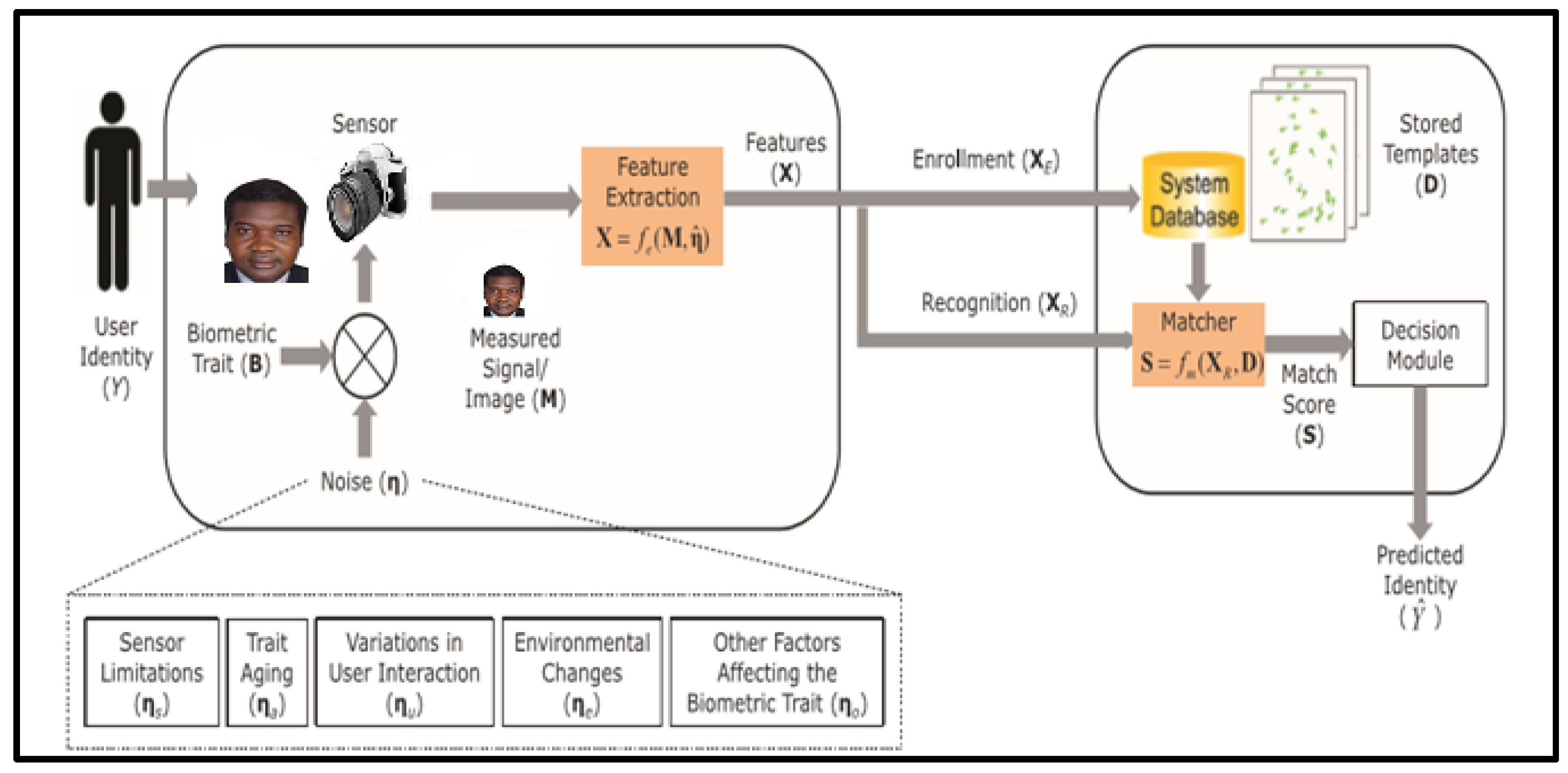

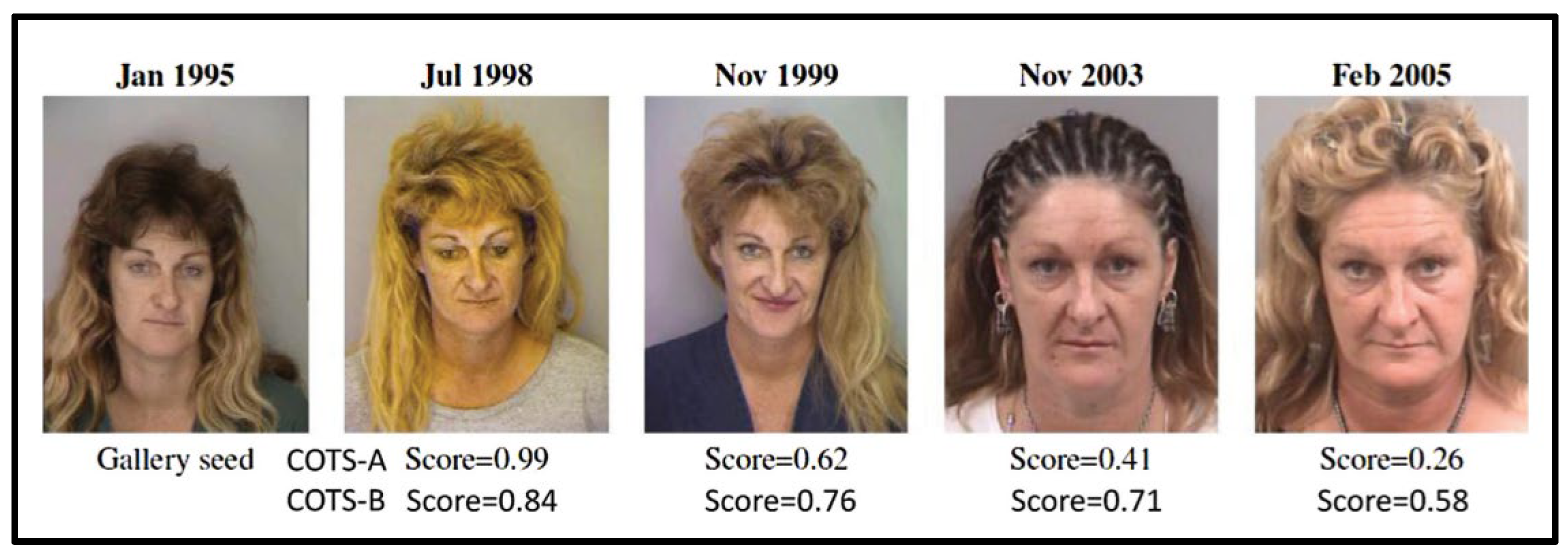

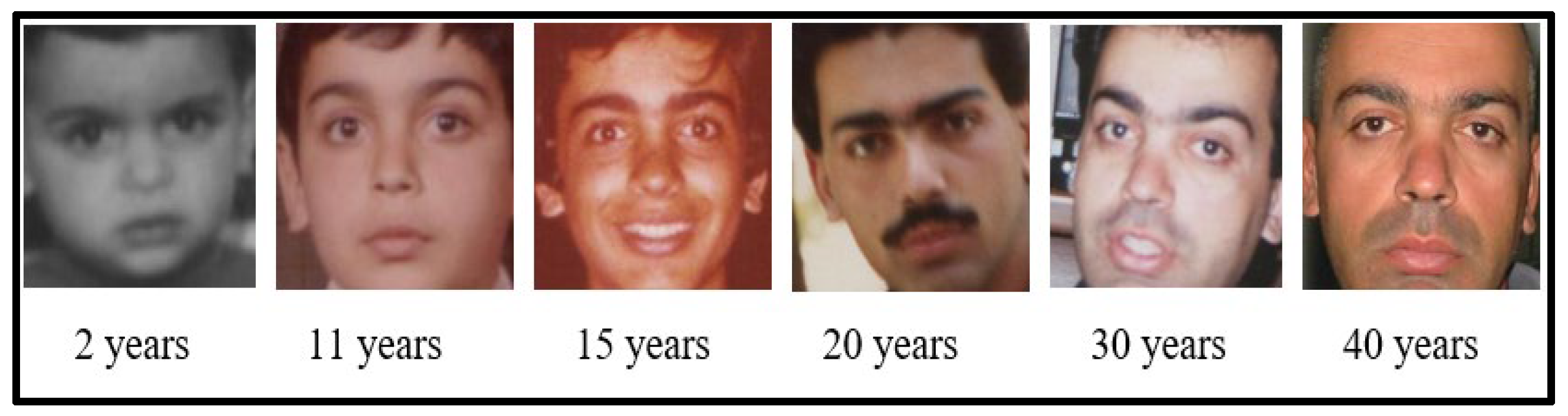

1. Introduction

- The FG-NET dataset is a mono-race age variant face recognition dataset that does not cover the black race subjects, and Africans cannot use such models.

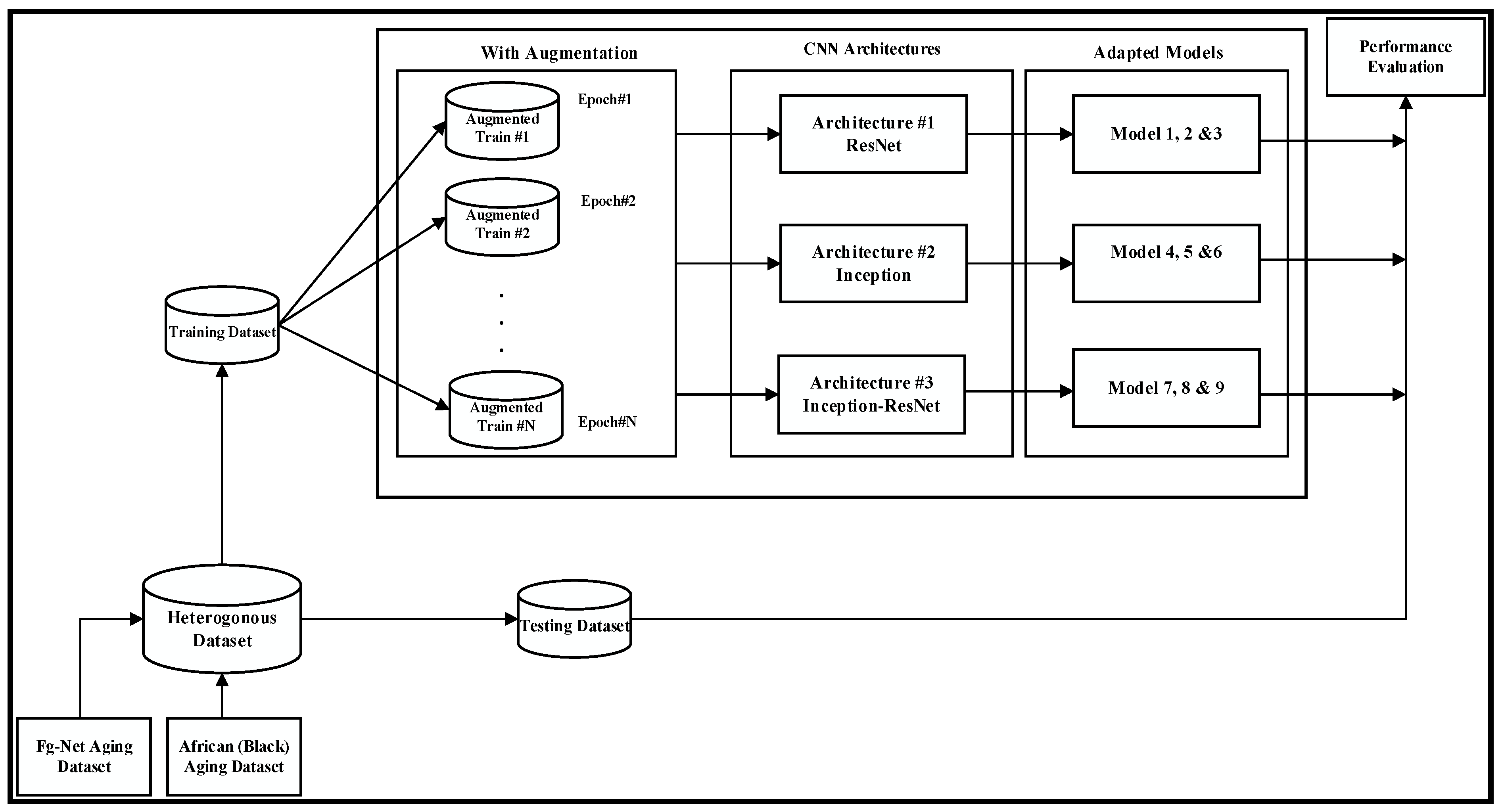

- Using the developed heterogeneous dataset and the modified Face and Gesture Recognition Network Ageing Database (FG-NET AD), a pre-trained convolutional neural network designed for the generic image recognition problem was adapted to create robust novel models capable of handling age-invariant face recognition.

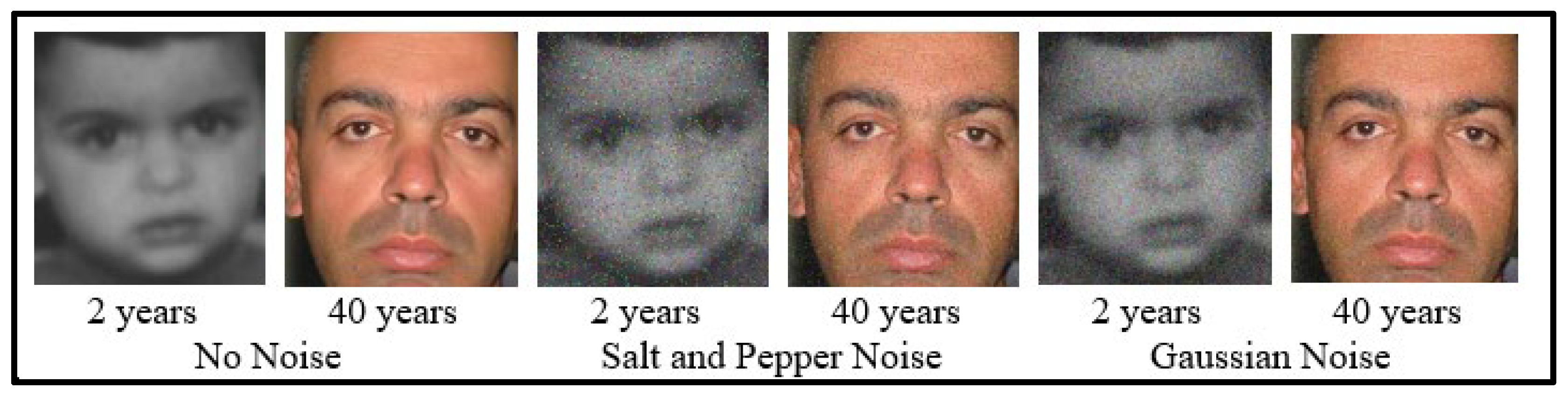

- The capacity to employ various forms of noise augmentation to raise the precision of the AIFR system, as opposed to the custom of removing noise during the pre-processing stage to raise the output accuracy, is another innovative aspect of this research. This research also breaks from the conventional approach of eliminating noise during the pre-processing stage to increase output accuracy by utilizing various forms of noise augmentation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1.1. Development of a Heterogeneous Age Invariant Face Recognition Dataset

- To ensure that every image in the dataset has the same amount of channels, transform it to RGB if the image is grayscale.

- Use the Sliding Windows Face Detector to find and clip the subject's face to eliminate background distractions and enable the deep learning model to extract more detailed and pertinent characteristics.

- Ensure that every image in the dataset has the same number of channels by converting any grayscale images to RGB images.

- Locate and crop the subject's face using the sliding windows face detector to reduce background noise and make it easier for the deep learning algorithm to acquire relevant and in-depth information.

- Create three distinct iterations of the cropped image by including the various noise types mentioned below:

- ■

- No noise (original cropped image with the only face)

- ■

- Gaussian Noise

- ■

- Salt and Pepper Noise

- To ensure that every image in the dataset has the same amount of channels, if the image is grayscale, convert it to RGB.

- To enable the deep learning algorithm to acquire richer and pertinent characteristics, recognize and crop the subject's face using the sliding Windows Face Detector to eliminate background noise.

- Create three distinct iterations of the cropped image by including the various noise types mentioned below:

- ■

- No noise (original cropped image with the only face)

- ■

- Gaussian Noise

- ■

- Salt and Pepper Noise

- d.

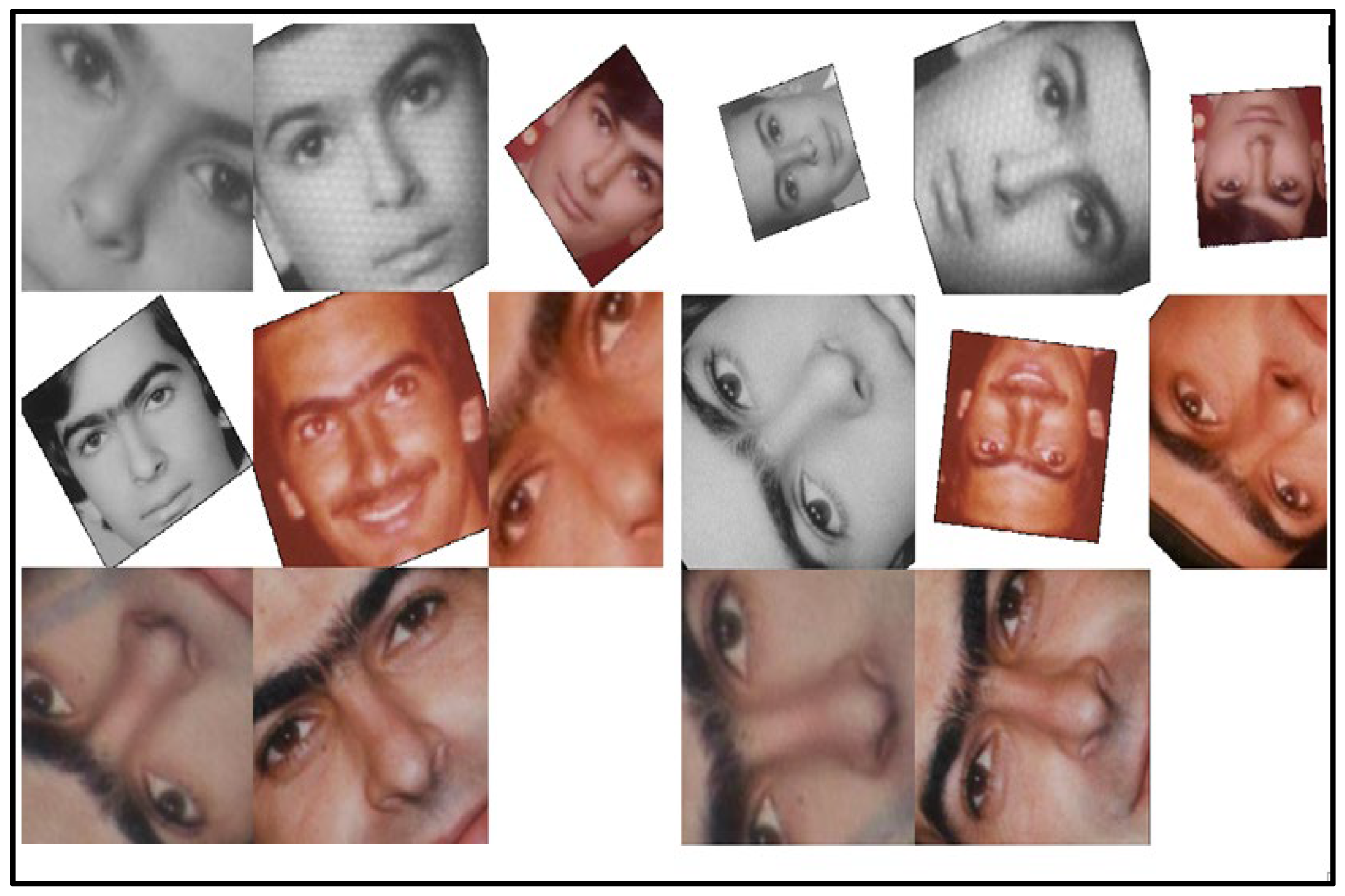

- Further, augment the images using random geometric transformations using an image augmenter with the outlined properties:

- ■

- A leftward and rightward reflection

- ■

- A leftward and rightward reflection

- ■

- Reflection in the direction of top to bottom

- ■

- An angle of rotation between 0 and 360°

- ■

- Scaling using a factor between 0.5 and 2

- ■

- Translation horizontally between -10 and 10 pixels

- ■

- Translation from -10 to 10 pixels vertically

3.1.1. Training and Testing the Adapted CNN Models

- Split the dataset into a training set (70% images) and a validation set (30% images).

- All train and test sets photos should be resized to fit the CNN model's input size.

- As indicated in Table 3, provide training preferences and hyper-parameters for transfer learning.

- On the train set, train the previously trained network.

- Utilizing the validation set, assess the trained network.

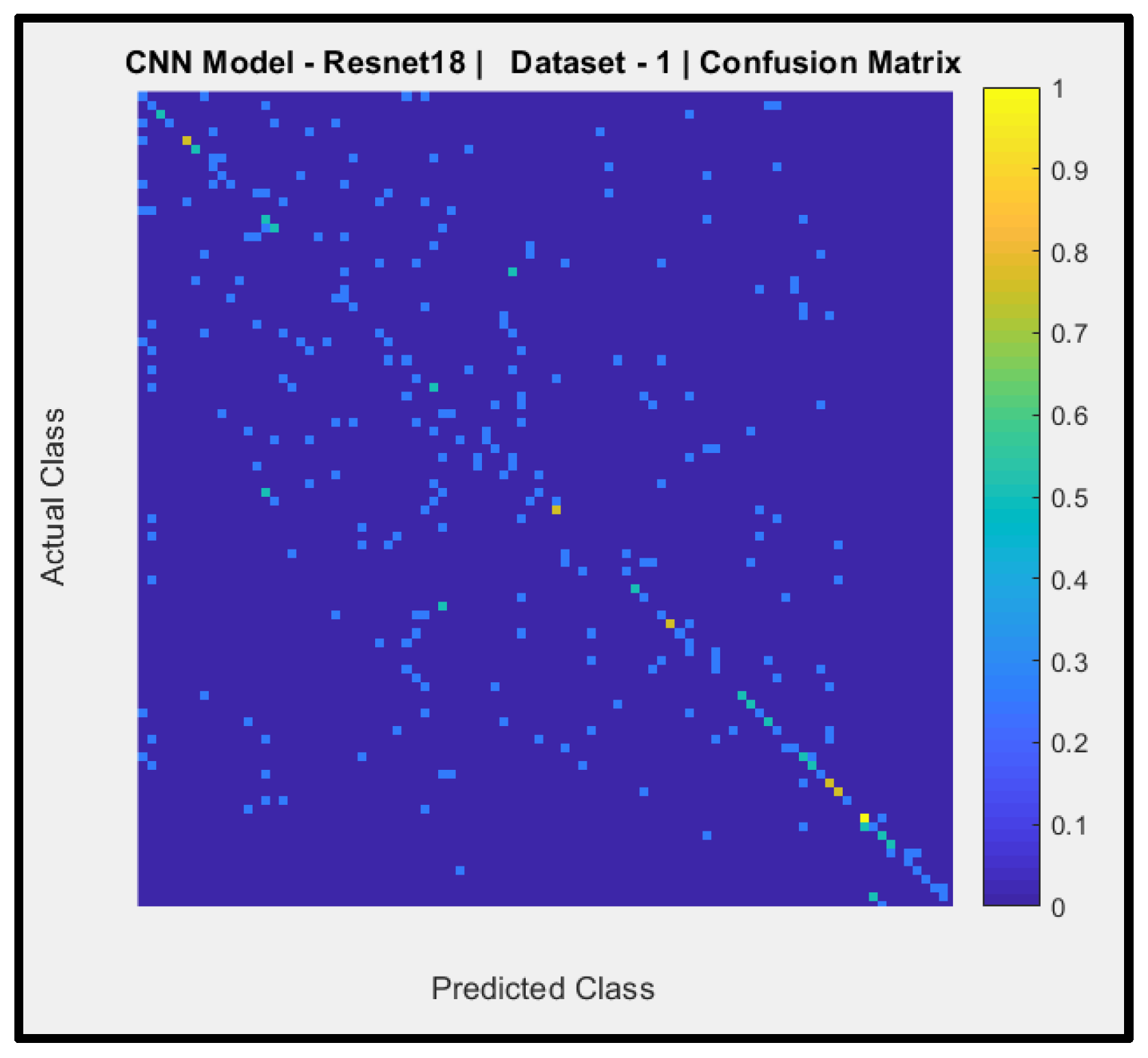

- The network's performance should be assessed based on the accuracy and confusion matrix.

2.1.1. Platform Specifications

2.1.1. Methods Used for Models Evaluation and Validation

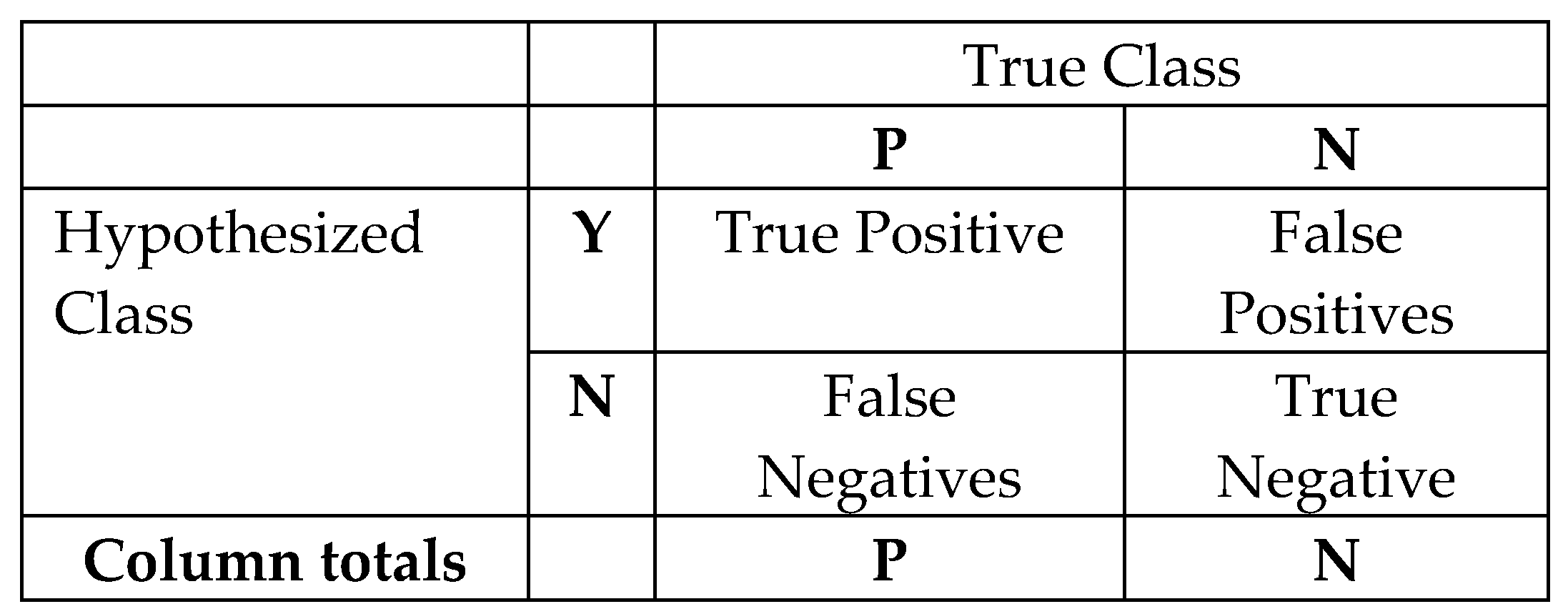

2.1. Terminology and Derivation from a Confusion Matrix

- Sensitivity, recall, hit rate, or True Positive Rate (TPR)

- b.

- Specificity, selectivity or True Negative Rate (TNR)

- c.

- Precision or Positive Predictive Value (PPV)

- d.

- Negative Predictive Value (NPV)

- e.

- Miss rate or False Negative Rate (FNR)

- f.

- Accuracy (ACC)

- g.

- F-Measure (F1 score) is the harmonic mean of precision and sensitivity

2.1.1. Evaluating Multi-Class Classification Performance from Confusion Matrix

2.1.1. Micro-Average Method of a Multi-class Classification Problem

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Results

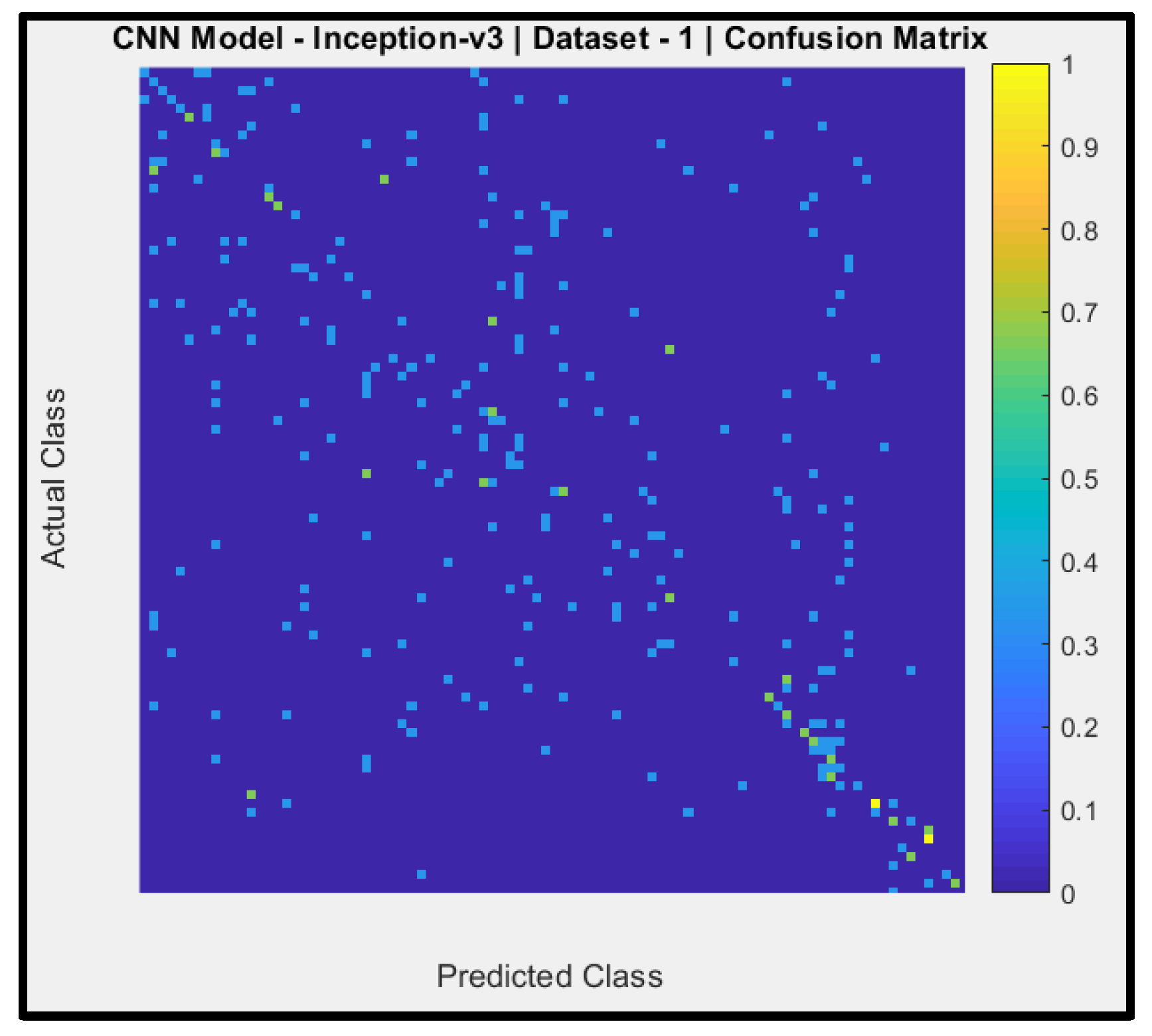

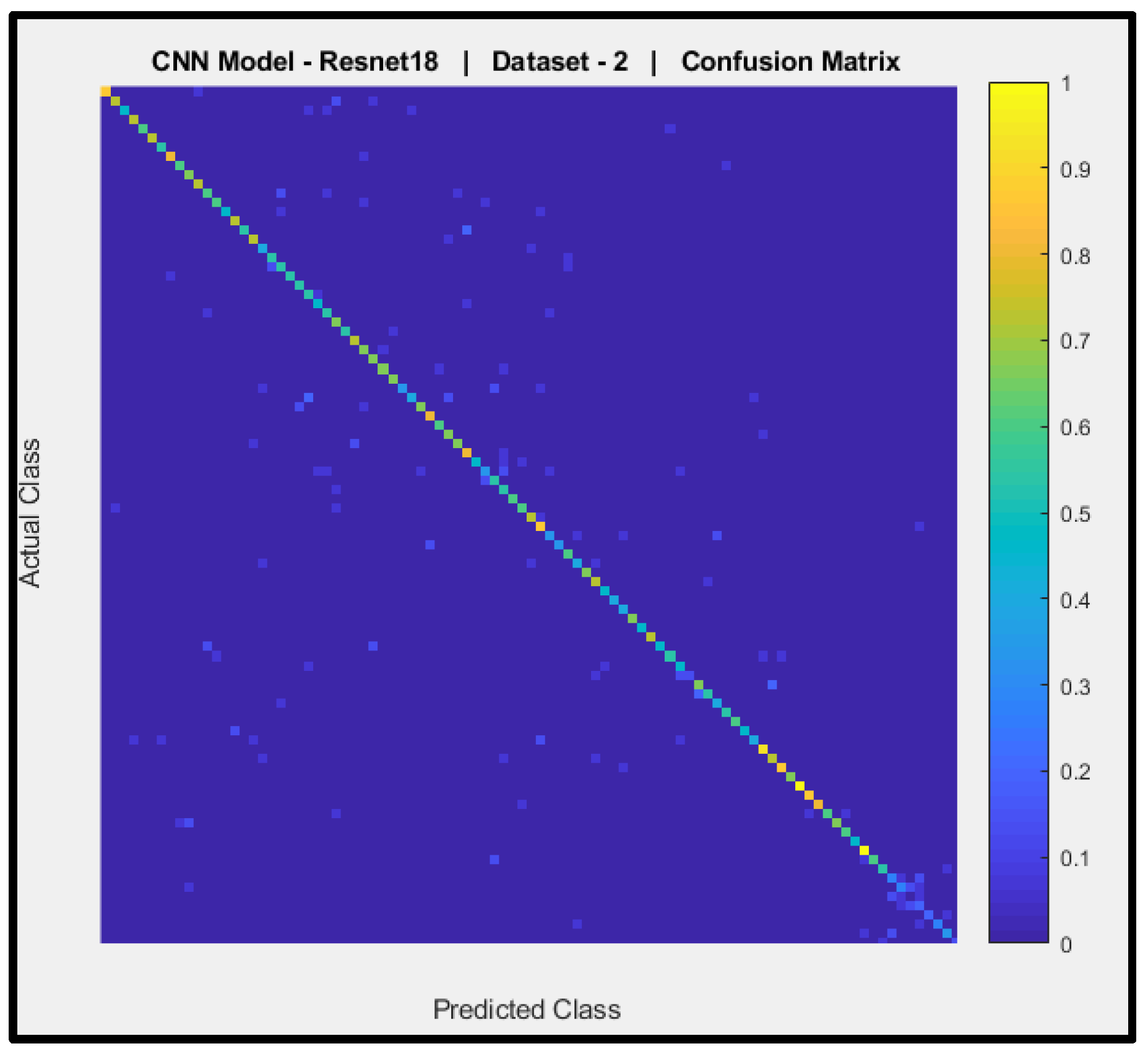

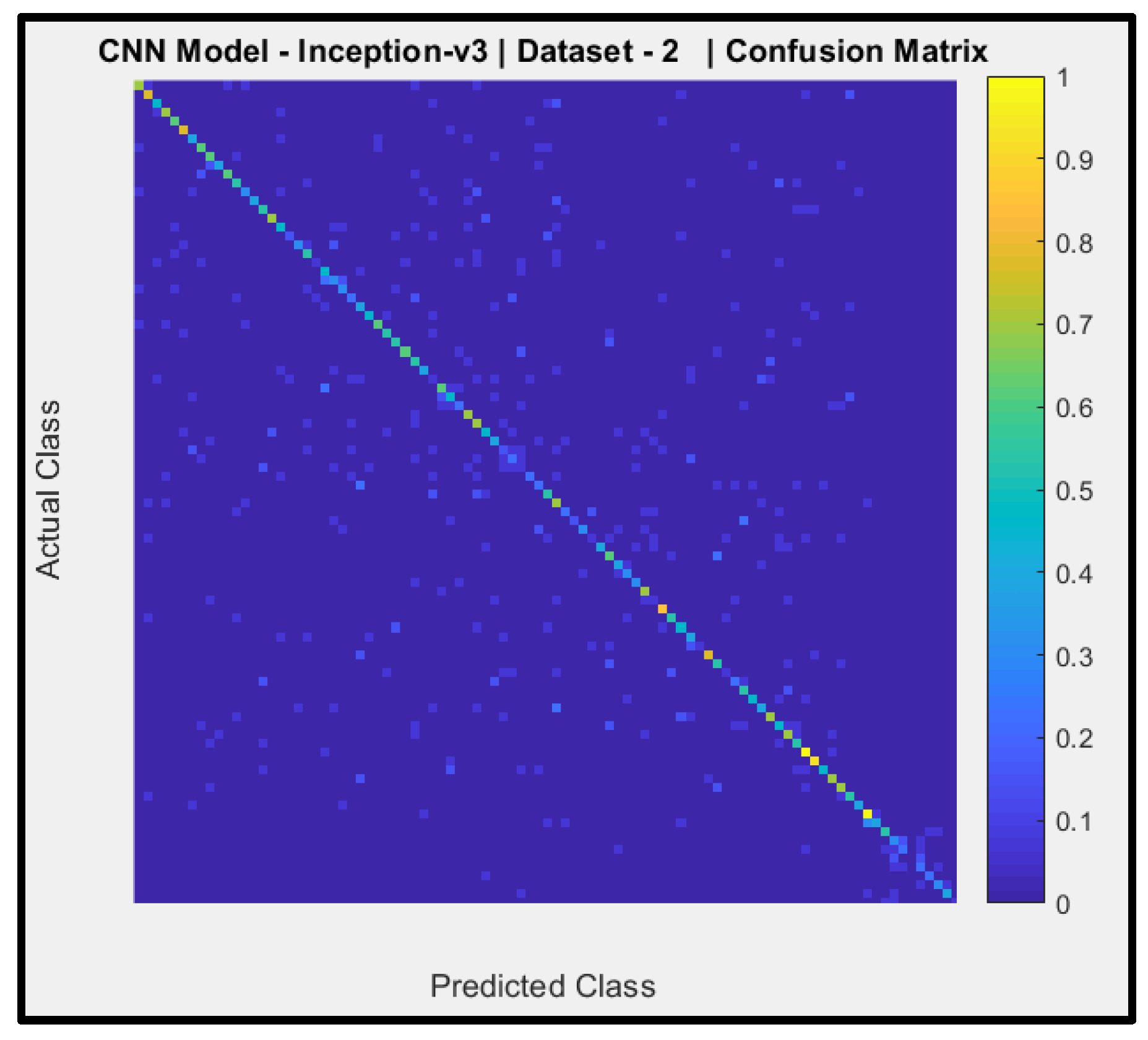

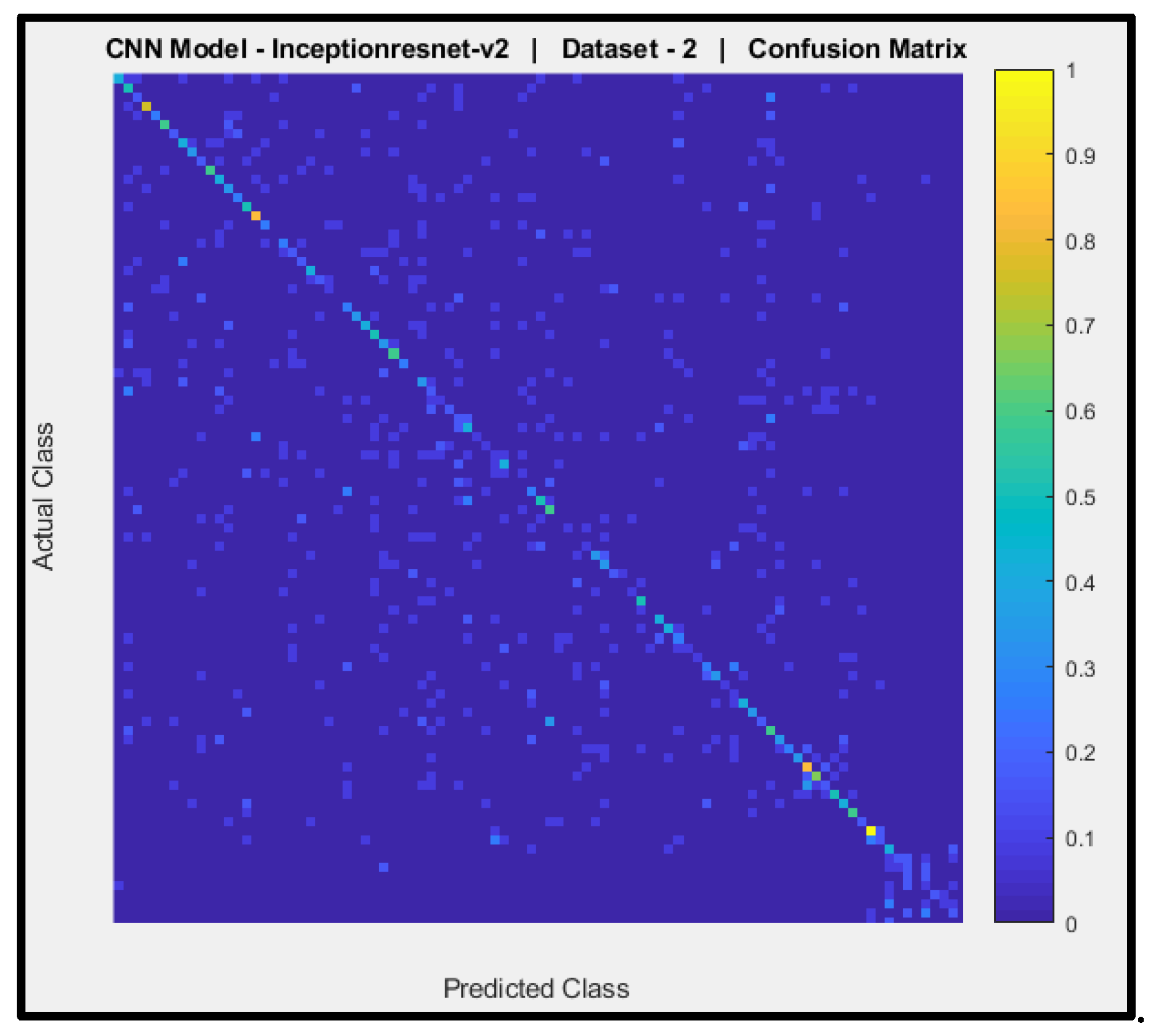

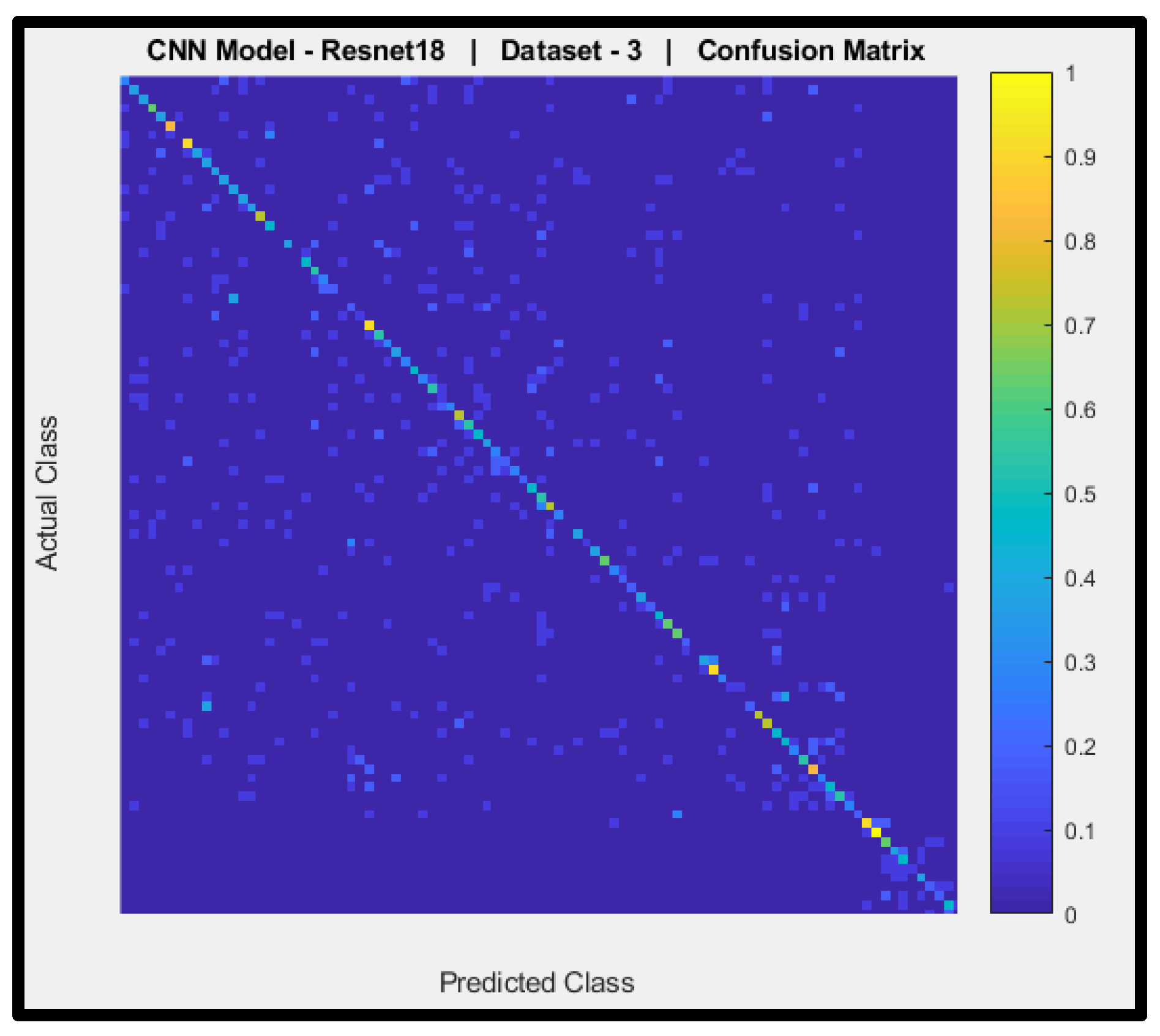

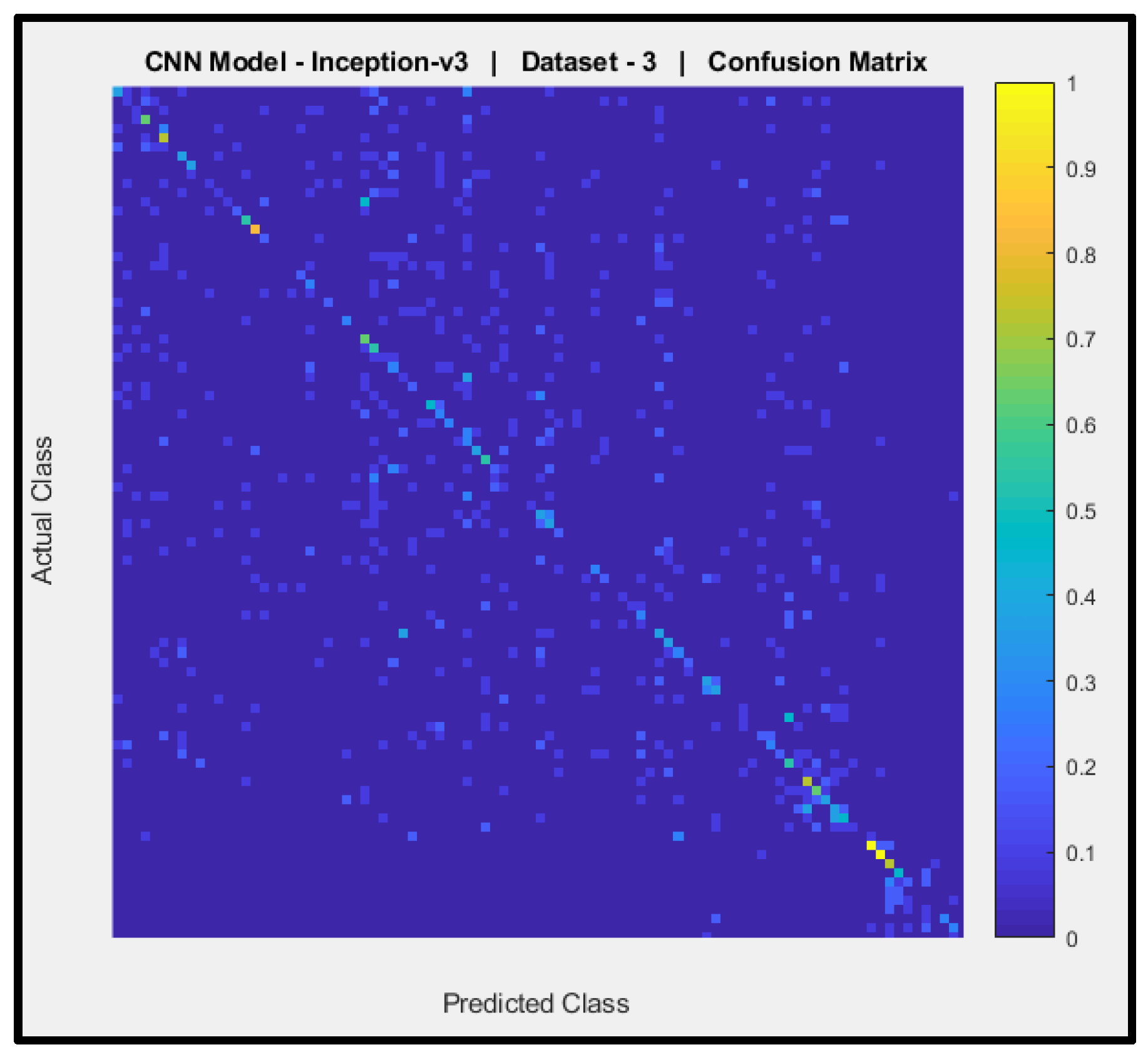

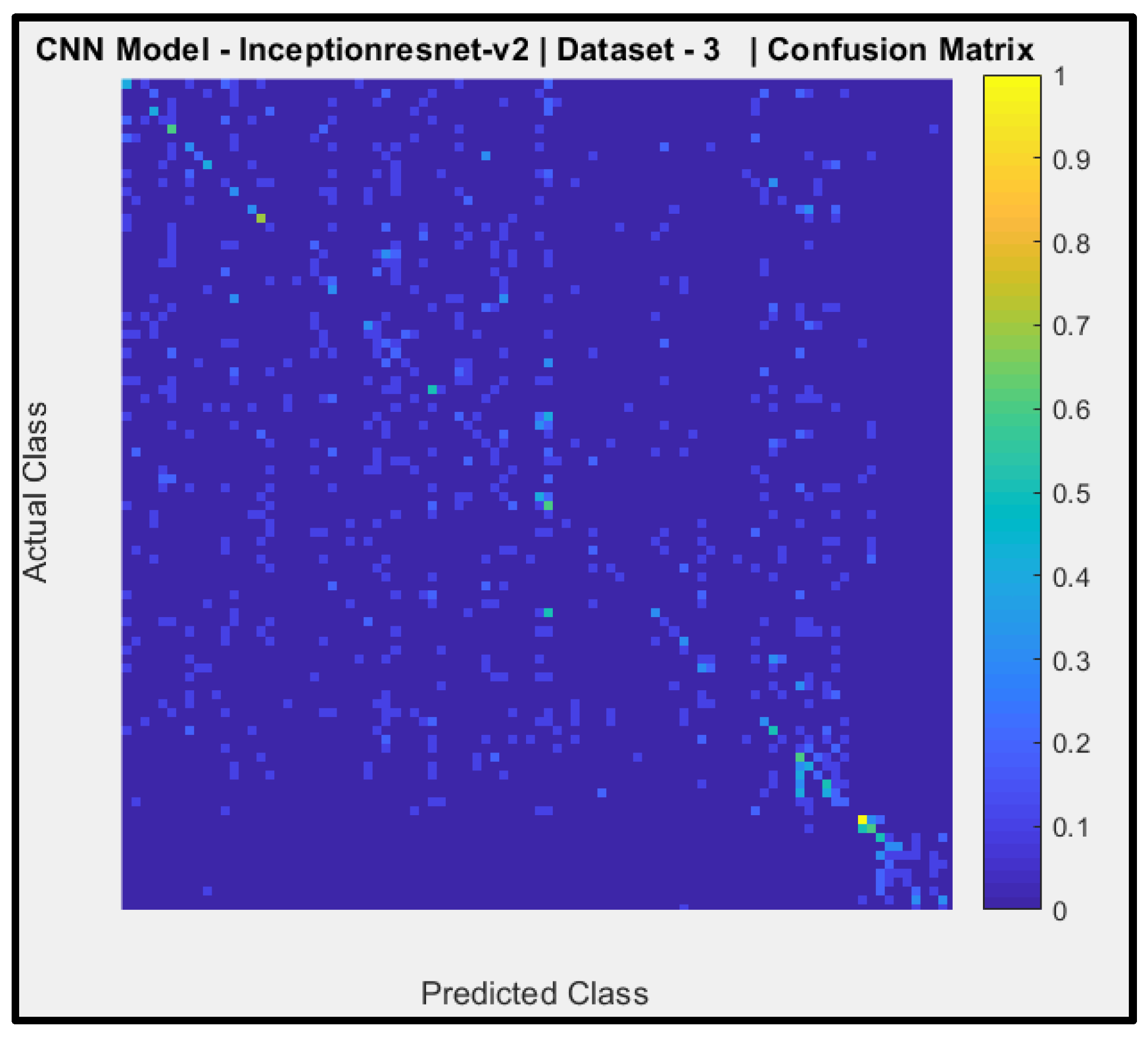

3.1.1. Confusion Matrices of the Various CNNs Models

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- K. Okokpujie, E. Noma-osaghae, S. John, K. Grace, and I. Okokpujie, “A Face Recognition Attendance System with GSM Notification,” in 2017 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Electro-Technology for National Development (NIGERCON) A, 2017, pp. 239–244. [CrossRef]

- H. El Khiyari and H. Wechsler, “Face Verification Subject to Varying ( Age, Ethnicity, and Gender ) Demographics Using Deep Learning,” J. Biom. Biostat., vol. 7, no. 4, 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. El Khiyari and H. Wechsler, “Age Invariant Face Recognition Using Convolutional Neural Networks and Set Distances,” J. Inf. Secur., vol. 8, pp. 174–185, 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Okokpujie, S. John, C. Ndujiuba, J. Badejo, and E. Noma-Osaghae, “An improved age invariant face recognition using data augmentation,” Bull. Electr. Eng. Informatics, 10(1)., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1–15, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Jain, K. Nandakumar, and A. Ross, “50 years of biometric research: Accomplishments, challenges, and opportunities,” Pattern Recognit. Lett., vol. 79, no. January, pp. 80–105, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Dang, L. Minh, Kyungbok Min, Hanxiang Wang, Md Jalil Piran, Cheol Hee Lee, and Hyeonjoon Moon. "Sensor-based and vision-based human activity recognition: A comprehensive survey." Pattern Recognition 108 (2020): 107561. [CrossRef]

- R. Narayanan and C. Rama, “Modeling Age Progression in Young Faces Modeling Age Progression in Young Faces,” no. February, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Taherkhani, A., Cosma, G. and McGinnity, T.M., 2020. AdaBoost-CNN: An adaptive boosting algorithm for convolutional neural networks to classify multi-class imbalanced datasets using transfer learning. Neurocomputing, 404, pp.351-366. [CrossRef]

- Taye, Mohammad Mustafa. "Understanding of machine learning with deep learning: architectures, workflow, applications and future directions." Computers 12, no. 5 (2023): 91. [CrossRef]

- Okokpujie, K., Okokpujie, I.P., Abioye, F.A., Subair, R.E. and Vincent, A.A., 2024. Facial Anthropometry-Based Masked Face Recognition System. Ingenierie des Systemes d'Information, 29(3), p.809. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lecun, Y. Bengio, and G. Hinton, “Deep learning,” Nature, vol. 521, no. 7553, pp. 436–444, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Krizhevsky, I., Sutskever, and G. Hinton, “ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks,” Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., pp. 1097–1105, 2012.

- C. Szegedy, V., Vanhoucke, J. Shlens, and Z. Wojna, “Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision,” arXiv1512.00567v3 [cs.CV] 11 Dec 2015, pp. 1–10, 2015.

- S. Karen and Z. Andrew, “Very Deep Convolutional Networks For Large-Scale Image Recognition,” Publ. as a Conf. Pap. ICLR, vol. arXiv:1409, pp. 1–14, 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Kaiming, X. Zhang, R. Shaoqing, and S. Jian, “Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition,” in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, 2016, pp. 770–778.

- C. Szegedy, S. Reed, P. Sermanet, V. Vanhoucke, and A. Rabinovich, “Going deeper with convolutions,” arXiv1409.4842v1 17 Sep 2014, pp. 1–12, 2014.

- C. Szegedy, S. Ioffe, V. Vanhoucke, and A. Alemi, “The Impact of Residual Connections on Learning,” arXiv:1602.07261v2 [cs.CV] eprint, no. 8, pp. 1–12, 2016.

- C. Shorten and T. M. Khoshgoftaar, “A survey on Image Data Augmentation for Deep Learning,” J. Big Data, vol. 6, no. 60, pp. 1–48, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Okokpujie, K., Okokpujie, I.P., Subair, R.E., Simonyan, E.O. and Adenugba, V.A., 2023. Designing an adaptive Age-Invariant Face recognition system for enhanced security in smart urban environments. Ingenierie des Systemes d'Information, 28(4), p.815. [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, A., Ahmad, K., Ahsan, M.A., Al-Fuqaha, A. and Qadir, J., 2022. Collaborative federated learning for healthcare: Multi-modal covid-19 diagnosis at the edge. IEEE Open Journal of the Computer Society, 3, pp.172-184. [CrossRef]

- M. Johnson and T. M. Khoshgoftaar, “Survey on deep learning with class imbalance,” J. Big Data, vol. 6, no. 27, pp. 1–54, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Luque, A. Carrasco, A. Martín, and A. de las Heras, “The impact of class imbalance in classification performance metrics based on the binary confusion matrix,” Pattern Recognit., vol. 91, pp. 216–231, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Alejo, J. A. Antonio, R. M. Valdovinos, and J. H. Pacheco-Sánchez, “Assessments metrics for multi-class imbalance learning: A preliminary study,” Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics), vol. 7914 LNCS, pp. 335–343, 2013, doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-38989-4_34.Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Title of the chapter. In Book Title, 2nd ed.; Editor 1, A., Editor 2, B., Eds.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 154–196. [CrossRef]

| CNN Models | Dataset-1 | Dataset-2 | Dataset-3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resnet-18 | Model-1 | Model-2 | Model-3 |

| Inception-v3 | Model-4 | Model-5 | Model-6 |

| Inception-Resnet-v2 | Model-7 | Model-8 | Model-9 |

| CNN Model | Network Depth |

Network Size (MB) |

Input Size |

Training Parameters (Millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resnet-18 | 18 | 43 | 224 x 224 x 3 | 11.7 |

| Inception-v3 | 48 | 87 | 299 x 299 x 3 | 23.9 |

| Inception-Resnet-v2 | 164 | 204 | 299 x 299 x 3 | 44.6 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Optimizer | SGDM |

| Learn Rate | 0.001 |

| Momentum | 0.9 |

| Mini batch Size | 20 |

| Epochs | 30 |

| Validation Frequency | 50iterations |

| TRUE CLASS | |||||

| A | B | C | D | ||

| PREDICTED CLASS | A | ||||

| B | |||||

| C | |||||

| D | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).